Abstract

Against the backdrop of the global manufacturing green transition, this study investigates the pathway through which green supply chain integration (GSCI) influences corporate green innovation performance. Grounded in the triple bottom line (TBL) theory, the empirical analysis is conducted using sample data from 364 manufacturing enterprises across 10 countries. It is important to note that a significant portion (56%) of the responses originated from China, providing a valuable but contextually specific perspective that should be considered when interpreting the results. Grounded in the TBL theory, our empirical analysis covers three key industries: electronics, machinery, and transportation components. The research examines two key relationships: first, the mediating role of new product launch speed (NPLS) in the links between GSCI (including green supplier integration, green customer integration, and green internal integration) and corporate environmental, financial, and social performance; second, the moderating effect of enterprise intelligence level (EIL) on the GSCI-NPLS relationship. This research validates the performance enhancement pathway of a market-responsive green product development model, whereby GSCI drives green innovation performance through accelerating NPLS, with EIL strengthening this acceleration effect, providing empirical support for manufacturing enterprises to optimize green supply chain management and improve green innovation efficiency.

1. Introduction

Against the backdrop of deepening global climate governance, exemplified by landmark policies like the European Green Deal which aims to make Europe the first climate-neutral continent by 2050 [1], and demands for high-quality development, green innovation is increasingly recognized as a core engine for transforming economic and social development models, as it integrates ecological priorities, resource efficiency, and low-carbon circularity [2,3]. As the backbone of socioeconomic development, manufacturing enterprises bear significant responsibility for facilitating a green transition [4,5]. Superior green innovation performance enables firms to reduce their environmental footprint, comply with regulations, tap into new markets, and build a green brand image, thereby achieving substantial economic and environmental benefits [6,7]. Investigating how to enhance this performance is thus critically important.

Green supply chain integration (GSCI) is a critical mechanism for improving green innovation performance by coordinating environmental responsibilities and resource utilization with upstream and downstream partners [8,9]. Through GSCI, firms can more effectively acquire green knowledge and technologies, address environmental challenges, and reduce innovation risks, thereby laying the foundation for market-attractive green products [10,11]. However, despite its acknowledged importance, the specific pathways through which GSCI translates into final innovation outcomes remain inconsistent and insufficiently clear [12]. Existing research predominantly focuses on static perspectives like resource acquisition, leaving a gap in understanding the dynamic process and temporal dimension of moving innovation from conception to commercialization [13,14]. In an era of rapid technological iteration and changing consumer preferences, the speed and efficiency of innovation have become more critical than mere resource investment [15].

This study argues that the speed of bringing innovative outcomes to market is a vital bridging mechanism. New product launch speed (NPLS) constitutes a core link connecting upstream GSCI efforts with final performance [16,17,18]. While GSCI provides the necessary nutrients for innovation, the ability to rapidly transform these into market-accepted commodities determines whether integration benefits are fully realized [19,20]. Rapid product launch helps capture market opportunities, establish first-mover advantages, and gather feedback for iterative optimization, thereby amplifying the value of green innovation. Therefore, we position NPLS as a key mediating variable to reveal the dynamic mechanism through which integration enhances performance.

Nevertheless, not all firms implementing GSCI can accelerate new product launch with equal efficiency. The enterprise intelligence level (EIL) is proposed as a crucial moderating factor that explains these differences [21,22]. In the current landscape, intelligence has become a key factor enhancing operational capabilities [23,24]. Highly intelligent enterprises can efficiently process information flows from integration, achieve real-time visibility and coordination across the supply chain, and accelerate R&D and production processes [25]. In contrast, firms with lower intelligence levels may struggle with information processing delays and inefficient decision-making, preventing them from fully realizing the speed advantages of GSCI [26,27]. Hence, introducing EIL as a moderating variable helps explain the varying abilities of firms to accelerate innovation and uncovers how intelligent technologies optimize the effectiveness of GSCI (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Roadmap.

2. Hypothesis Development

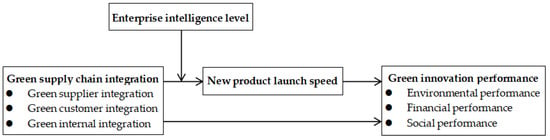

This study constructs a conceptual model exploring the pathway “green supply chain integration—new product launch speed—corporate green innovation performance”, with enterprise intelligence level as a moderating variable, to investigate the mechanisms influencing firms’ green innovation performance (see Figure 2). This research model, as illustrated in Figure 2, posits that green supply chain integration (GSCI), conceptualized as a second-order construct reflected by its three first-order dimensions (green supplier, customer, and internal integration), enhances corporate green innovation performance indirectly through the mediating mechanism of new product launch speed. This core pathway—depicting a full mediation process—is central to our hypothesis (H3). Furthermore, the enterprise intelligence level is theorized to act as a significant moderating context that strengthens the entire value-creation pathway. It is hypothesized to not only potentiate the effect of GSCI on enhancing launch speed but also to facilitate the translation of such speed into superior multidimensional performance outcomes (encompassing environmental, financial, and social performance). The model is designed to test a comprehensive set of hypotheses concerning these direct, mediating, and moderating relationships, providing a nuanced understanding of the dynamics between strategic integration and innovation success.

Figure 2.

Conceptual Framework.

As summarized in Table 1, while previous research has established the fundamental relationship between GSCI and firm performance, our study makes several distinct contributions. First, this study extends the theoretical grounding by incorporating dynamic capability theory, which allows us to examine not just whether GSCI improves performance, but how it does so through the dynamic mechanism of accelerated new product launch. Second, we clarify that GSCI influences innovation performance through multiple pathways: both directly through resource and knowledge integration, and indirectly by enhancing operational agility through NPLS. This dual-pathway perspective addresses a significant gap in the literature regarding the process mechanisms through which GSCI creates value.

Table 1.

Comparative analysis of green supply chain integration studies and current research contribution.

2.1. Green Supply Chain Integration and New Product Launch Speed

Green supplier integration (GSI) and green customer integration (GCI) are two forms of external integration. Li & Thurasamy (2025) examined how integration effectiveness between suppliers and manufacturers varies with the strength of mutual integration willingness, also analyzing the impact of government subsidies on such integration outcomes [28]. When an enterprise collaborates with suppliers, early supplier involvement in ideation, technology incubation, and product development—by providing parameters related to eco-materials and technologies—can significantly shorten the enterprise’s material testing cycle, thereby enhancing new product launch speed. GCI primarily focuses on addressing customers’ green demands [29]. According to Chavez et al. (2016), customer feedback provides new ideas and technologies that effectively reduce trial-and-error costs during innovation and upgrading, enabling enterprises to position products more accurately and avoid ineffective production [30]. Thus, GCI positively influences NPLS. Feng & Wang (2013) found that customer participation positively promotes new product development speed [31]. Enterprises can also gather effective feedback and identify potential issues related to green services or products through customer communities or social media [32]. Green internal integration (GII) embeds environmental objectives into relevant internal departments such as R&D, procurement, and production. Our finding that green internal integration (GII) significantly enhances environmental performance by optimizing production processes and reducing waste aligns with the growing body of research on operational decision-making under carbon constraints. The study demonstrates that carbon reduction policies directly influence green production scheduling, highlighting the critical role of internal operational adjustments in achieving compliance and cost-effectiveness [33]. Our results on GII provide empirical evidence from a supply chain integration perspective, reinforcing the view that internal efficiency is a cornerstone for manufacturers to navigate a policy environment increasingly shaped by carbon pricing mechanisms. Cross-functional collaboration improves fault tolerance in production processes, reduces the need for rework due to non-conformities, and shortens time-to-market [34,35]. Giovanni (2012) found that strengthened internal cross-department cooperation significantly promotes NPLS in technology-based enterprises [36]. The study examines a conceptual pathway wherein green supply chain integration (comprising supplier, customer, and internal integration) influences corporate green innovation performance through the mediating mechanism of new product launch speed, with enterprise intelligence level moderating the relationship between integration and launch speed. Therefore, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

H1a.

Green supplier integration positively influences new product launch speed.

H1b.

Green customer integration positively influences new product launch speed.

H1c.

Green internal integration positively influences new product launch speed.

2.2. Green Supply Chain Integration and Green Innovation Performance

Based on the triple bottom line theory, corporate green innovation performance should be evaluated from three dimensions: environmental performance (EP), financial performance (FP), and social performance (SP) [37,38,39]. Sun & Sun (2021) suggest that the adoption of GSI, GCI, and GII each promotes corporate innovation performance, with GSI having a more direct and significant effect [40]. Liu et al. (2025) found that both internal and external green management have significant positive effects on corporate innovation performance [41]. Zhu et al. (2013), in analyzing the relationship between GII and environmental performance, found that environmental process integration positively affects environmental performance [42]. Accordingly, this research proposes the following hypotheses:

H2a.

Green supplier integration positively influences corporate environmental performance.

H2b.

Green supplier integration positively influences corporate financial performance.

H2c.

Green supplier integration positively influences corporate social performance.

H3a.

Green customer integration positively influences corporate environmental performance.

H3b.

Green customer integration positively influences corporate financial performance.

H3c.

Green customer integration positively influences corporate social performance.

H4a.

Green internal integration positively influences corporate environmental performance.

H4b.

Green internal integration positively influences corporate financial performance.

H4c.

Green internal integration positively influences corporate social performance.

2.3. New Product Launch Speed and Green Innovation Performance

New product launch speed (NPLS) reflects a firm’s foresight and market agility, directly affecting the efficiency of commercializing green technologies and its market competitiveness [43]. By accelerating the promotion of environmentally friendly products, quickly capturing market share, and enhancing comprehensive performance across environmental, financial, and social dimensions, enterprises can establish a virtuous cycle that strengthens their market position, enhances brand influence, and ultimately achieves sustainable development goals [44,45]. Fisher et al. (2024) argue that rapid new product launch significantly enhances operational performance, indicating a direct positive correlation between accelerating time-to-market and improved firm performance [17]. Enterprises implementing efficient new product development strategies can launch products swiftly, thereby improving overall operational effectiveness. Hence, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

H5a.

New product launch speed positively influences corporate environmental performance.

H5b.

New product launch speed positively influences corporate financial performance.

H5c.

New product launch speed positively influences corporate social performance.

2.4. The Mediating Role of New Product Launch Speed

Current research has not reached a consensus on the mechanism through which GSCI affects green innovation performance. Further investigation is needed to determine whether this influence is direct or indirect. Zhou et al. (2018) found that supply chain agility partially mediates the relationship between green external integration and environmental performance [46]. Fisher et al. (2024) demonstrated that new product launch speed fully mediates the relationships between customer participation, customer communication, and firm performance, and partially mediates the relationship between customer focus and firm performance [17]. Building on prior research, this study treats new product launch speed as a mediating variable. It is proposed that GSCI enhances green innovation performance through two pathways: directly, and indirectly by facilitating new product launch speed. Therefore, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H6a.

New product launch speed mediates the relationship between green supplier integration and corporate environmental performance.

H6b.

New product launch speed mediates the relationship between green customer integration and corporate environmental performance.

H6c.

New product launch speed mediates the relationship between green internal integration and corporate environmental performance.

H7a.

New product launch speed mediates the relationship between green supplier integration and corporate financial performance.

H7b.

New product launch speed mediates the relationship between green customer integration and corporate financial performance.

H7c.

New product launch speed mediates the relationship between green internal integration and corporate financial performance.

H8a.

New product launch speed mediates the relationship between green supplier integration and corporate social performance.

H8b.

New product launch speed mediates the relationship between green customer integration and corporate social performance.

H8c.

New product launch speed mediates the relationship between green internal integration and corporate social performance.

2.5. The Moderating Role of Enterprise Intelligence Level

Enterprise intelligence level plays a crucial role in the new product development process. The core of information flow between an enterprise and its external partners lies in its information processing, storage, and dissemination systems, which include hardware, software, IT services, and databases, typically coordinated by the IT department. The manifestation of this system varies between internal and external contexts and should be adapted to practical circumstances [47]. Zhong et al. (2015) found that big data analytics capability positively influences new product development performance [48]. Tian et al. (2022) categorized enterprise intelligent capability into three dimensions: integrated resource capability, in-depth data analysis capability, and practical application capability [49]. Empirical findings indicate that all three capabilities enhance overall supply chain effectiveness. Advanced intelligent management platforms, supported by big data analytics, facilitate real-time communication among supply chain segments, ensure high-quality information flows across the network, enable intelligent supply chain operations, and improve efficiency and performance [50]. Thus, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

H9a.

Enterprise intelligence level positively moderates the relationship between green supplier integration and new product launch speed.

H9b.

Enterprise intelligence level positively moderates the relationship between green customer integration and new product launch speed.

H9c.

Enterprise intelligence level positively moderates the relationship between green internal integration and new product launch speed.

3. Methodology

3.1. Questionnaire Design and Data Collection

The sample data for this study were collected from manufacturing enterprises across three key industries: electronics, machinery, and transportation components, spanning ten countries including Brazil, Germany, China, Spain, Israel, Sweden, Italy, Japan, South Korea, and Finland. The questionnaire underwent rigorous translation/back-translation procedures with three independent bilingual experts achieving 95% conceptual equivalence. Regarding country selection, we prioritized nations representing diverse manufacturing capabilities and environmental policy regimes, though the final sample shows concentrated representation from China (56%) reflecting its dominant position in global manufacturing. This contextual focus requires consideration when generalizing findings.

The selection of these specific industries was based on the following rationales to ensure the relevance and comparability of the sample. Firstly, the electronics, machinery, and transportation components industries are all characterized as technology-intensive sectors facing significant pressures and drivers for green transition. They share common imperatives in terms of stringent environmental regulations, complex global supply chains, and a critical need for green product innovation to maintain competitiveness. This common context enhances the comparability of green supply chain integration practices and their outcomes across these industries. Secondly, despite their distinct end products, these industries exhibit comparable supply chain structures and innovation processes. They all involve multi-stage production, rely heavily on supplier collaboration for components and materials, and require close customer integration for product development and customization. This structural similarity allows for a consistent examination of the core constructs under investigation—GSCI, NPLS, and green innovation performance—across the sample. Furthermore, focusing on these three industries within the manufacturing sector enables a targeted exploration of green innovation pathways while controlling for excessive heterogeneity that might arise from including vastly different sectors. This approach strengthens the internal validity of the findings regarding the proposed relationships in the conceptual model.

To address potential cultural and institutional biases in data collection across the ten countries, we implemented several measures to enhance the cross-cultural validity and reliability of the study. First, all measurement items were adapted from well-established scales in international literature, which have been validated in diverse contexts, reducing the risk of conceptual misinterpretation. Second, we included country as a control variable in the statistical analysis to account for variations in regulatory frameworks and institutional environments that might influence the perception and implementation of GSCI. Additionally, the questionnaire was administered in the local language of each country after rigorous translation and back-translation procedures to ensure linguistic accuracy. We acknowledge that differences in cultural norms and regulatory pressures could affect responses. Thus, the findings should be interpreted with caution regarding generalizability. This approach aligns with best practices in multinational supply chain research and helps mitigate biases by explicitly recognizing contextual factors.

A final measurement scale is developed after appropriate modifications and adjustments, thus encompassing constructs such as green supply chain integration, new product launch speed, enterprise intelligence level, environmental performance, financial performance, and social performance. All items are measured using a five-point Likert scale, as detailed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Measurement items.

The construct of New Product Launch Speed (NPLS) was operationalized to capture the temporal efficiency across critical stages of the green innovation process, encompassing design, testing, and commercialization. As detailed in Table 1, the measurement items were designed to reflect this comprehensive scope:

NPLS1 (The time interval from product concept formation to the initiation of formal development) primarily captures the efficiency of the early design and conceptualization phase.

NPLS2 (The coordination efficiency between various stages of the product development process) and NPLS3 (The pre-launch processes are advanced efficiently without significant delays) together assess the speed and fluidity of the testing, coordination, and final preparation phases.

NPLS4 (The entire cycle time from concept design to the formal market launch of a new product is significantly shorter than the industry average) provides an overarching measure of the total speed to market, directly encompassing the journey from initial design to final commercialization.

This multi-item scale, adapted from Chen et al. (2023) and Zhang & Yang (2016), ensures that our operationalization of NPLS reflects a holistic view of launch speed, accounting for efficiency in transitioning a product idea from its inception through to its successful market introduction [3,16].

This study employs country, industry category, and firm age as control variables to mitigate the potential confounding effects of extraneous variables on the study results. The sample data is collected from three industries—namely electronics, machinery, and transportation components—covering ten countries, including Brazil, Germany, China, Spain, Israel, Sweden, Italy, Japan, Republic of Korea, and Finland, which yields a total of 364 valid questionnaires (see Table 3 and Table 4).

Table 3.

Sample distribution by country and industry.

Table 4.

Sample distribution by firm age.

To address common method bias, the majority of the questionnaire’s measurement items are distributed to employees from multiple departments within each participating enterprise [57]. Each enterprise provides participants from 23 distinct positions and departments, thus ensuring a diverse range of perspectives. The breakdown of respondents across the sample enterprises is provided in Table 5.

Table 5.

Distribution of questionnaire respondents.

3.2. Reliability and Validity Tests

As shown in Table 6, all Cronbach’s α coefficients are greater than 0.7, and all corrected item-total correlation (CITC) values exceed 0.5, indicating high internal consistency among the measurement items. Furthermore, the Cronbach’s α of item-deleted values are lower than the overall Cronbach’s α of the corresponding constructs, suggesting that the measurement items designed earlier significantly enhance the reliability of the target variables and that the item settings are appropriate.

Table 6.

Reliability test results.

As presented in Table 7, the KMO value is 0.838, which exceeds the standard threshold of 0.7, indicating that the data exhibit good structural validity. Bartlett’s sphericity test yields a p-value of zero, which is below the conventional significance level (typically 0.05), suggesting significant correlations among the variables.

Table 7.

KMO and Bartlett test results.

Convergent validity is typically assessed by examining the extent to which measurement items correlate with their intended latent constructs. This research quantifies convergent validity through factor loadings, composite reliability (CR), and average variance extracted (AVE). The study includes 29 measurement items with a valid sample size of 364, representing approximately 12.5 times the number of items, which satisfies the sample size requirement for such analyses. As summarized in Table 8, the majority of item factor loadings exceed 0.7, with only three items falling slightly below this threshold (0.606, 0.699, and 0.692—the latter two being very close to 0.7). The CR values for all constructs are above 0.8, with one exception at 0.780, which is still very close to the threshold, indicating strong internal consistency among items within each construct. The AVE values for each variable all meet or exceed the recommended minimum of 0.5, further supporting adequate convergent validity.

Table 8.

Convergent validity test results.

3.3. Hypothesis Testing

3.3.1. Direct Effect Testing

The hypothesized relationships were tested using structural equation modeling (SEM). Prior to assessing the path coefficients, the overall model fit was rigorously evaluated to ensure the proposed theoretical model adequately represents the sample data. The analysis yielded the following fit indices: χ2/df = 2.15, Comparative Fit Index (CFI) = 0.94, Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI) = 0.93, and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) = 0.06. These indices collectively indicate a good model fit, as the CFI and TLI values exceed the recommended threshold of 0.90, and the RMSEA value is below the conservative cutoff of 0.08. This robust model fit provides a solid foundation for the subsequent interpretation of the path coefficients.

The unstandardized path coefficients, standard errors (S.E.), critical ratios (C.R.), p-values, and standardized path coefficients derived from the model are presented in Table 8. As all hypotheses in this study are posited to have positive effects, a hypothesis is considered supported only if the standardized path coefficient is positive and the significance level meets p < 0.05 [58,59].

As summarized in Table 9, the standardized path coefficient for H1a is 0.224 with a p-value of 0.003. Thus, H1a is supported. Hypothesis H1b is also supported (β = 0.194, p = 0.008). However, H1c is not supported (β = 0.104, p = 0.123). For the effects of green supplier integration on green innovation performance, H2a (β = 0.079, p = 0.081) and H2b (β = 0.011, p = 0.925) are not supported, whereas H2c is supported (β = 0.127, p = 0.010). Concerning green customer integration: H3a (β = 0.118, p = 0.010), H3b (β = 0.667, p < 0.001), and H3c (β = 0.145, p = 0.004) are all supported. Similarly, all hypotheses regarding green internal integration are supported: H4a (β = 0.679, p < 0.001), H4b (β = 0.475, p < 0.001), and H4c (β = 0.664, p < 0.001). Finally, the positive influences of new product launch speed on environmental (H5a: β = 0.303, p < 0.001), financial (H5b: β = 0.276, p < 0.001), and social performance (H5c: β = 0.318, p < 0.001) are all statistically significant.

Table 9.

Direct effect test results.

The structural equation model demonstrated good fit with the data, χ2/df = 2.15, CFI = 0.94, TLI = 0.93, RMSEA = 0.06, and SRMR = 0.05, all meeting recommended thresholds for acceptable fit. The mediation effects were tested using bootstrapping with 5000 resamples and 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals. Multicollinearity was assessed via VIF, with all values below 3, indicating no concerning collinearity.

3.3.2. Mediating Effect of New Product Launch Speed

To verify whether new product launch speed plays a mediating role between green supply chain integration (including green supplier integration, green customer integration, and green internal integration) and green innovation performance (environmental, financial, and social performance), this study employs the percentile bootstrap method for analysis. The results are shown in Table 10 and Table 11.

Table 10.

Mediation effect test of new product launch speed (bootstrap results).

Table 11.

Model fit indices for the hierarchical regression analysis of mediation effects.

A mediating effect is considered statistically significant if the 95% bootstrap confidence interval (95% Boot CI) does not include zero. Therefore, H6c and H8c are not supported, indicating that the mediating effect of new product launch speed between green internal integration and environmental performance, as well as between green internal integration and social performance, is not significant. In contrast, the 95% Boot CIs for the remaining hypotheses (H6a, H6b, H7a, H7b, H7c, H8a, H8b) do not include zero, confirming that the mediating effects are significant.

Further analysis is conducted to distinguish between different types of mediating mechanisms. As illustrated in Table 9, new product launch speed exhibits a partial mediating effect in the relationships between green supplier integration and social performance, green customer integration and financial performance, and green customer integration and social performance. Conversely, new product launch speed demonstrates a full mediating effect in the relationships between green supplier integration and financial performance, green supplier integration and environmental performance, green customer integration and environmental performance, and green internal integration and financial performance.

3.3.3. Moderating Effect of Enterprise Intelligence Level

This study employs SPSS 28.0 to analyze the moderating effect of enterprise intelligence level (EIL) on the relationships between green supply chain integration (GSCI) and new product launch speed (NPLS). The results are summarized in Table 12.

Table 12.

Moderating effect test of enterprise intelligence level.

As shown in Table 12, in Model 1 testing the moderating effect of EIL on the relationship between green supplier integration and NPLS, the t-value is 3.368, which is significant at the p < 0.001 level. In Model 3, the interaction term yields a t-value of 2.927, also significant at p < 0.01, indicating that the interaction between green supplier integration and enterprise intelligence level is statistically significant. Thus, H9a is supported. In the test of the moderating effect of EIL on green customer integration and NPLS (Model 4), the t-value is 3.560 (p < 0.001). The interaction term in Model 6 shows a t-value of 4.344, significant at p < 0.001, confirming that the interaction between green customer integration and enterprise intelligence level is significant. Therefore, H9b is supported. For the moderating effect of EIL on green internal integration and NPLS, Model 7 returns a t-value of 1.959, which does not reach significance at the p < 0.05 level. However, in Model 9, the interaction term is significant with a t-value of 3.192 (p < 0.01), supporting a significant moderating role of enterprise intelligence level. Hence, H9c is supported. In conclusion, the results demonstrate that enterprise intelligence level positively moderates the relationships between all three dimensions of green supply chain integration and new product launch speed, thereby validating H9a, H9b, and H9c.

4. Discussion

This study constructs a theoretical model of “green supply chain integration–new product launch speed–green innovation performance”, while also examining the moderating effect of enterprise intelligence level. The findings indicate that both green supplier integration and green customer integration enhance corporate green innovation performance by accelerating new product launch speed. Although green internal integration does not directly accelerate time-to-market, it improves financial performance by facilitating faster product launches. Furthermore, enterprise intelligence level positively moderates the impact of green supplier integration, green customer integration, and green internal integration on new product launch speed.

4.1. The Impact of Green Supply Chain Integration on New Product Launch Speed

Hypotheses H1a and H1b are supported, whereas H1c is not. This indicates that both green supplier integration and green customer integration positively promote new product launch speed, whereas the effect of green internal integration is not significant. The non-support of H1c, suggesting that green internal integration (GII) does not directly accelerate new product launch speed (NPLS), can be interpreted through the lens of Organizational Inertia Theory. It is plausible that in well-established firms, the very processes implemented for cohesive environmental management—while beneficial for compliance—create structural rigidities that inhibit the cross-functional agility and rapid experimentation essential for compressing development cycles. Effective green supplier and customer integration provide firms with rich material resources and practical feedback for green innovation, which is conducive to accelerating product launch. Particularly in technology-intensive industries, early supplier involvement helps R&D departments identify technical bottlenecks in components in advance, reducing the number of technical iterations in later stages. By gathering user feedback through customer communities or inviting customers to participate in prototype testing, firms can accurately capture user needs and incorporate market feedback early, thereby reducing development risks, minimizing rework, shortening commercialization time, and significantly increasing launch speed.

The non-significant effect of green internal integration may be attributed to the following reasons. First, sample firms vary by industry and region. Global and local requirements may conflict, and firms may face geopolitical risks or local production mandates that force frequent supply chain adjustments, offsetting the efficiency gains from internal integration. Second, products in the electronics industry evolve rapidly with highly modular technologies. Excessive internal integration may lead to decision-making rigidity. In the machinery and transportation parts industries, where technologies are relatively standardized, integration may offer low marginal returns for technological breakthroughs and may even slow down development due to process redundancies. Technology-intensive firms rely heavily on tacit knowledge within R&D departments, such as patented technologies and process experience. If integration only streamlines superficial processes without enabling deep knowledge sharing, it may instead increase communication costs. Third, the sample includes firms with establishment years ranging from 13 to 162 years. Older firms may suffer from bureaucratic hierarchies or entrenched technical pathways, making it difficult for green internal integration to break existing processes; it may even reduce efficiency due to conflicts between old and new systems. Newer firms may lack sufficient funding or talent, resulting in integration that is merely nominal, such as establishing cross-departmental meeting mechanisms without supporting software or training, thus failing to substantively accelerate development.

To effectively leverage green supply chain integration (GSCI) for accelerating innovation, managers must adopt a strategic and technology-enabled approach that moves beyond basic collaboration. This involves implementing targeted strategies for each integration dimension. For green supplier integration (GSI), this means deploying supplier relationship management systems to foster early and continuous supplier involvement in product design and establishing joint technology roadmaps to pre-emptively address material challenges. For green customer integration (GCI), the focus should be on creating structured feedback loops through online panels and co-creation workshops to integrate customer insights directly into R&D, complemented by social listening tools to track evolving green preferences in real-time. Furthermore, to overcome the hurdles associated with green internal integration (GII), a differentiated approach is essential—larger, established firms should prioritize breaking down departmental silos by instituting dedicated cross-functional teams for green innovation, while younger, resource-constrained firms must first invest in foundational project management tools and training to build the necessary capability for deeper integration. This comprehensive and nuanced approach ensures that external partnerships and internal alignment are synergistically leveraged to maximize the speed and impact of green innovation.

4.2. The Impact of New Product Launch Speed on Green Innovation Performance

Hypotheses H5a, H5b, and H5c are all supported, indicating that new product launch speed positively influences environmental, financial, and social performance. Rapid product launch allows firms to capture market niches first and obtain technology premiums. Moreover, locking in customer groups early creates ecosystem dependencies. When consumers adopt multiple products from the same brand, device interconnectivity through proprietary protocols may create switching costs, such as loss of exclusive services or incurring data migration expenses, thereby enhancing financial performance. Faster launch also accelerates the application of environmental technologies, and the use of virtual technologies reduces physical waste, lowering the environmental burden of technological and product innovation. The ability to quickly develop products that address public issues demonstrates a firm’s responsiveness to social needs. Moreover, cross-functional teamwork promotes multi-skilling among employees, and rapidly launching products tailored to local demands creates regional employment, fulfilling corporate social responsibilities and thereby improving social performance.

Managers should recognize new product launch speed (NPLS) not merely as an operational metric but as a pivotal strategic lever for achieving overarching sustainability goals. To fully capitalize on this, a multi-faceted approach is essential: First, by strategically framing speed-to-market initiatives around the core objectives of capturing emerging market share, establishing technological leadership, and building a robust reputation for sustainability. Second, by accelerating the development of a proprietary ecosystem around green products—through complementary services and software—to enhance customer loyalty and create sustainable, long-term revenue streams. And finally, by systematically integrating NPLS and its outcomes into formal sustainability reporting and executive dashboards, thereby directly linking accelerated innovation to tangible environmental impact reduction, such as the faster adoption of energy-saving technologies, and measurable social value creation, such as job growth generated from new product lines.

4.3. The Impact of Green Supply Chain Integration on Green Innovation Performance

This study empirically examines the impact of green supply chain integration (GSCI) on green innovation performance. Except for H2a and H2b, which were not supported, all other hypotheses were validated. Specifically, green supplier integration significantly enhances financial performance, while green customer integration and green internal integration jointly promote comprehensive performance improvements across environmental, financial, and social dimensions. However, green supplier integration does not exhibit a significant direct impact on either environmental or social performance.

The mechanisms through which GSCI enhances performance are as follows. Firstly, customer preference for eco-friendly products drives firms to adopt green technologies, thereby reducing pollution in production processes. Internal cross-departmental data sharing helps avoid resource waste, collectively enhancing environmental performance. Secondly, green supplier integration strengthens a firm’s bargaining power and reduces transaction costs by consolidating procurement to lower unit prices, obtain volume discounts, and optimize payment terms. Meanwhile, gathering customers’ environmental needs can expand the market for products and reduce the risk of unsold inventory. Furthermore, using energy-saving equipment or optimizing production processes not only meets environmental standards but also cuts costs by reducing energy and material consumption. Green internal integration, through environmental management systems such as setting sustainability goals and implementing green performance metrics, drives departments to improve resource efficiency and reduce waste. Thus, green supplier, customer, and internal integration all positively impact financial performance. Additionally, collaborating with customers on public welfare projects enhances social impact, and providing green workspaces improves employee satisfaction, thereby elevating social performance.

The non-significant effects of green supplier integration on environmental and financial performance may stem from contextual factors. In technology-intensive sectors (e.g., electronics), core innovations often rely heavily on in-house R&D, limiting the contribution from suppliers. In mature firms, stable supplier networks may yield diminishing returns, while newer firms face resource constraints. Geopolitical disruptions, such as trade barriers, can also undermine the effectiveness of long-term integration efforts.

In managerial practice, firms need to design differentiated integration strategies. For green customer integration and green internal integration, the focus should be on directly improving environmental and financial performance through joint innovation and internal process optimization. For green supplier integration, the priority should shift towards building partnerships that enhance social performance, such as collaborating with suppliers who uphold high labor standards or source from disadvantaged communities. In high-tech industries, managers should recalibrate their expectations, viewing suppliers primarily as partners in achieving incremental process improvements, ensuring supply stability, and guaranteeing compliance, rather than as the main drivers of breakthrough product innovation.

4.4. The Mediating Role of New Product Launch Speed

Hypotheses H6c and H8c are not supported, indicating that new product launch speed does not mediate the relationships between green internal integration and environmental or social performance. The non-significant mediation effect for H6c indicates that the presence of GII, even with accelerated NPLS, does not automatically translate into superior environmental performance (EP). Absorptive Capacity Theory provides a critical insight: the internal mechanisms for transforming integrated green knowledge into truly innovative, market-ready eco-designs may be deficient. The link between speed and substantive environmental gains might be weak if the accelerated products are merely incremental improvements rather than outcomes of exploratory green learning. The lack of support for H8c highlights the distinct nature of social performance (SP) compared to financial or environmental metrics. According to Stakeholder Theory, SP is derived from deep, legitimate engagement with communities and employees. The pressure for rapid commercialization may conflict with the time-intensive processes of meaningful stakeholder consultation and ethical capacity building, thereby decoupling internal green integration efforts from perceived social value, even when launch speed is increased. In contrast, H6a, H6b, H7a, H7b, H7c, H8a, and H8b are supported, confirming significant mediation. New product launch speed fully mediates the effects of green supplier integration on financial and environmental performance, green customer integration on environmental performance, and green internal integration on financial performance. This implies that improving performance in these dimensions can only be achieved by enhancing launch speed through integration strategies. In comparison, new product launch speed partially mediates the effects of green supplier integration on social performance and green customer integration on financial and social performance, suggesting that green customer and supplier integration can create value both directly and indirectly through enhanced agility. Customer data not only generate direct benefits but also enable rapid decision-making. Rapid product iteration increases customer reliance, generating more data assets that further enhance agility and value, forming a virtuous cycle of “data—agility—value”. Since green internal integration does not significantly promote new product launch speed, mediation is not observed for environmental or social performance.

Building on these mediation findings, we provide a practical interpretation to guide managerial strategies tailored to different enterprise intelligence levels (EIL). The identified mediating effect underscores the critical importance of building organizational agility, which necessitates that managers make targeted investments in capabilities such as rapid prototyping, flexible manufacturing, and agile project management to fully translate the benefits of supply chain integration into market-ready products. Specifically, enterprises should adopt a differentiated approach based on their EIL. For high-EIL firms, the strong mediation effects suggest prioritizing predictive launch optimization by leveraging intelligent platforms to dynamically adjust development timelines using real-time data from integrated supply chains. For medium-EIL firms, the partial mediations indicate a focus on establishing cross-functional digital workflows that connect R&D, production, and sustainability functions to build foundational acceleration capabilities. For low-EIL firms, the weaker mediation pathways highlight the need to first implement targeted digitalization of critical innovation stages, particularly in areas where supplier and customer integration occur, to establish basic acceleration capabilities before pursuing comprehensive integration. Concurrently, it is vital to recognize that green customer integration (GCI) creates value through a dual-path mechanism—yielding both direct relationship benefits and indirect speed advantages—an insight that justifies concurrent investments in deep customer collaboration and the internal systems that enable a fast response to the insights gained.

4.5. The Moderating Role of Enterprise Intelligence Level

Hypotheses H9a, H9b, and H9c are all supported, indicating that higher levels of enterprise intelligence strengthen the positive effects of green supplier integration, green customer integration, and green internal integration on new product launch speed. Enterprises can develop a range of intelligent platforms tailored to different stakeholders, including suppliers, customers, and internal staff. First, they can leverage blockchain traceability technology to achieve intelligent matching with suitable green suppliers, which helps reduce material waiting time in the supply chain. Second, enterprises can apply social listening tools and AI-based customer profiling techniques to accurately define the parameters of green products, thereby compressing the market testing cycles of new green offerings. Third, they can establish cross-departmental data platforms to integrate and transparently share real-time operational data. Such platforms also support the automation of internal processes, further reducing redundancies in both decision-making procedures and information reception across departments. These facilitate predictive analysis and dynamic adjustment in product development planning, accelerating time-to-market. Therefore, enterprise intelligence systemically amplifies the promoting effect of all three integration practices on new product launch speed.

The significant moderating role of Enterprise Intelligence Level (EIL) provides a clear mandate for managers to proactively digitalize their innovation processes, with strategic actions varying by EIL baseline. High-EIL firms should focus on deepening customer and supplier integration through AI-powered platforms, as the moderation effect is strongest here. For instance, deploying intelligent customer insight tools can compress the design-to-testing cycles by leveraging real-time feedback. Medium-EIL firms are advised to balance investments between basic integration efforts and intelligent system implementation. A phased approach—starting with digitizing internal workflows before expanding to external partners—ensures that EIL enhancements amplify, rather than hinder, integration gains. Low-EIL firms should initially focus on basic digitalization of core processes (e.g., using cloud-based collaboration tools) to elevate EIL to a threshold level. This prevents the “integration without acceleration” pitfall and ensures that GSCI efforts translate into faster time-to-market.

This requires a holistic strategy encompassing three critical areas: First, making strategic investments in foundational technologies like data analytics, AI, and integrated information platforms, which act as critical enablers that multiply the returns on green supply chain integration (GSCI) investments. Second, systematically upskilling the workforce, particularly in supply chain, R&D, and marketing functions, through targeted training programs to equip employees with the necessary competencies to leverage intelligent systems for data-driven decision-making and collaboration. And ultimately, fostering an overarching data-driven culture that shifts organizational decision-making away from siloed information and intuition, ensuring that choices are consistently based on insights derived from the intelligent analysis of integrated data streams—a cultural transformation that is essential for EIL to deliver its full potential in accelerating green innovation.

4.6. Managerial Challenges and Implementation Risks

While our findings demonstrate the significant benefits of green supply chain integration (GSCI) and enterprise intelligence level (EIL), it is crucial to address the managerial challenges and implementation risks associated with these initiatives. First, the substantial upfront investments required for intelligent technologies (e.g., IoT sensors, AI analytics platforms) may pose financial constraints, particularly for small- and medium-sized enterprises. Second, technological interoperability remains a critical hurdle, as legacy systems often lack compatibility with new smart platforms, leading to data silos and integration failures. For instance, inconsistencies in data protocols between suppliers and manufacturers can undermine the real-time visibility achieved through GSCI. Third, organizational resistance—driven by employee technological anxiety, skill gaps, or workflow disruptions—may impede adoption. To mitigate these risks, we recommend conducting phased implementations to distribute costs and technical challenges; adopting modular architectures to ensure backward compatibility; and developing change management programs that include training, incentives, and transparent communication. These insights balance the optimistic outcomes with pragmatic considerations, empowering managers to anticipate and navigate implementation barriers.

4.7. The Role of Organizational Change Management and Innovation Culture

While our empirical findings demonstrate significant relationships between green supply chain integration (GSCI), enterprise intelligence level (EIL), and green innovation performance, it is crucial to address the underlying organizational mechanisms that translate these technological and integrative capabilities into tangible outcomes. Organizational change management serves as a critical catalyst in this process, particularly during the implementation of intelligent technologies and green practices. Enterprises that proactively manage resistance to change through structured communication, training programs, and incentive alignment are better positioned to leverage GSCI and EIL advantages. For instance, cross-functional training initiatives can mitigate employee anxiety about new technologies while fostering the skills needed to operate intelligent systems effectively.

Similarly, innovation culture acts as an organizational enabler that amplifies the impact of GSCI and EIL on performance outcomes. A culture that encourages experimentation, tolerates calculated risks, and rewards collaborative problem-solving creates an environment where green innovations can flourish. Such cultures facilitate the integration of sustainability principles into daily operations while accelerating the adoption of intelligent technologies through enhanced organizational agility. The interplay between EIL and innovation culture is particularly noteworthy—while intelligent technologies provide the tools for innovation, it is the cultural foundation that determines how effectively these tools are utilized to achieve sustainability goals.

This expanded perspective aligns with strategic human resource management literature, which emphasizes that technological investments yield optimal returns only when supported by complementary organizational practices. Our findings suggest that the performance gains from GSCI and EIL are not automatic but are mediated by the organization’s capacity to manage change and cultivate an innovation-oriented mindset. This explains why firms with similar levels of technological integration may achieve divergent innovation outcomes based on their attention to these soft organizational factors.

5. Conclusions and Implications

5.1. Integrated Conclusions and Implications

This study validates a market-responsive green product development model wherein green supply chain integration (GSCI) drives corporate green innovation performance through accelerating new product launch speed (NPLS), with enterprise intelligence level (EIL) strengthening this acceleration effect. The findings demonstrate that EIL positively moderates the influence of GSCI on NPLS, revealing that intelligent enterprises can better leverage integration advantages to achieve rapid innovation commercialization. Specifically, enterprises should enhance intelligent infrastructure completeness and employ data analytics to process multi-source information from suppliers, internal departments, and customers, while providing professional training for employees to ensure effective implementation. Although green internal integration does not directly accelerate NPLS, it significantly enhances comprehensive performance, necessitating strengthened internal collaboration and cross-departmental coordination mechanisms.

Theoretical implications are threefold. First, this research expands GSCI studies by constructing an “integration-speed-performance” framework that addresses the literature’s predominant focus on static perspectives by highlighting dynamic commercialization processes. Second, it deepens the mediation mechanism of NPLS, theoretically explaining how GSCI indirectly enhances performance. Third, it introduces EIL as a key moderating variable, enriching understanding of digitalization’s enabling role in green innovation.

Practically, this study offers actionable strategies. Enterprises should adopt digital platforms (e.g., blockchain traceability systems) to enhance supply chain transparency, establish customer feedback mechanisms for iterative product optimization, and develop intelligent systems for real-time monitoring and decision-making. Policymakers can introduce tax incentives for intelligent technology adoption and establish industry standards to promote cross-organizational collaboration. These findings provide valuable insights for manufacturing enterprises seeking to optimize green supply chain management and accelerate sustainable transformation amid global green transition trends.

For manufacturing firms, especially those in the electronics, machinery, and transportation sectors with significant exposure to the European market, our findings offer a strategic roadmap. To navigate the regulatory landscape shaped by the “Fit for 55” [60] package, managers should prioritize utilizing GSCI with European partners to gain early insights into evolving regulatory requirements and to co-develop compliant materials and technologies, accelerating NPLS through EIL to quickly adapt product portfolios in response to specific regulations like CBAM, thereby reducing transition risks and seizing first-mover advantages in the green market.

For policymakers, our findings underscore the need for a synergistic policy mix to accelerate industrial decarbonization. For jurisdictions outside the EU, developing mirroring support systems, such as green technology subsidies and certification programs, is urgently needed to help local firms build resilience against the extraterritorial effects of the “Fit for 55” package (particularly CBAM) and reduce the carbon footprint of their products. Furthermore, this targeted support for green supply chain integration and intelligent technologies, which enhances endogenous innovation capabilities, should be complemented by well-designed market-based instruments. As research on carbon tax efficacy suggests, effectively pricing carbon creates a universal economic signal that incentivizes green innovation across all sectors [61]. Ultimately, a comprehensive strategy combining targeted firm-level support with a broader carbon pricing mechanism can create a powerful push-pull effect, effectively preparing industries for new international standards and accelerating the green transition of the manufacturing sector.

5.2. Limitations and Future Research Directions

This study, while offering empirical evidence on the pathways through which GSCI and EIL enhance green innovation performance, has several limitations that point toward valuable future research opportunities. A primary limitation stems from the cross-sectional nature of our survey data, which, despite validating correlations, constrains our ability to make definitive causal claims or capture the dynamic evolution of the constructs over time. Furthermore, the focus on internal and supply chain factors means the broader institutional context, particularly the impact of public policy, remains underexplored. Finally, the quantitative methodology, though powerful for identifying patterns, limits the depth of understanding regarding the underlying managerial processes and contextual challenges firms face during implementation.

To address these limitations, future research can be advanced in several promising directions. First, to unravel the complex causal mechanisms and temporal dynamics, longitudinal studies are highly recommended. Tracking the evolution of GSCI, EIL, NPLS, and performance over multiple years would allow researchers to establish stronger causal inferences and understand how these capabilities develop and interact over time. Second, to gain a deeper, contextualized understanding of the “how” and “why” behind our statistical findings, such as the non-significant direct effect of GII on NPLS, qualitative approaches like in-depth case studies or multi-round interviews are essential. Selecting polar cases (e.g., firms with high versus low integration efficiency) could reveal the organizational dynamics, managerial cognitive processes, and implementation barriers that quantitative data alone cannot capture. Third, to incorporate the critical external environment, analyses of public policy impacts represent a crucial extension. Future work could integrate policy variables (e.g., environmental regulation stringency, green technology subsidies) as moderating conditions or conduct comparative case studies across different policy regimes. This would elucidate how public policy interacts with firm-level strategies to shape the economic and environmental outcomes of green innovation. By embracing these mixed-methods, longitudinal, and policy-sensitive research designs, scholars can build a more comprehensive, dynamic, and contextually rich understanding of green supply chain innovation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.Y.; methodology, F.Y.; software, J.C.; validation, J.C.; formal analysis, J.C.; resources, F.Y.; data curation, H.Z. and J.H.; writing—original draft, J.C.; writing—review and editing, Y.S. (Yuting Song); visualization, H.Z. and J.H.; supervision, Y.S. (Yiting Shao); project administration, F.Y.; funding acquisition, F.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by China National Funds for Distinguished Young Scientists [grant number 71425001], the National Natural Science Foundation of China [grant number 52103113], Jiangsu Provincial Government Scholarship for Overseas Studies, and the Support Program for Young Scholars of Nanjing University of Finance and Economics.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of School of Management Science and Engineering, Nanjing University of Finance and Economics (protocol code [2024]-82 and 1 November 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Jinyi Hu was employed by China Overseas (Hong Kong) Limited. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- European Commission. The European Green Deal. COM(2019) 640 Final. Brussels. 2019. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=COM%3A2019%3A640%3AFIN (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Junaid, M.; Zhang, Q.; Syed, M.W. Effects of sustainable supply chain integration on green innovation and firm performance. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 30, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yuan, M.; Lin, H.; Han, Y.; Yu, Y.; Sun, C. Organizational improvisation and green innovation: A dynamic capability perspective. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2023, 32, 5686–5701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguinis, H.; Glavas, A. What we know and don’t know about corporate social responsibility: A review and research agenda. J. Manag. 2012, 38, 932–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkis, J.; Zhu, Q.; Lai, K.H. An organizational theoretic review of green supply chain management literature. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2011, 130, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Sarkis, J.; Lai, K. Initiatives and outcomes of green supply chain management implementation by Chinese manufacturers. J. Environ. Manag. 2007, 85, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Sarkis, J.; Lai, K. Green supply chain management: Pressures, practices and performance within the Chinese automobile industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2007, 15, 1041–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Cai, J.; Feng, T. The influence of green supply chain integration on firm performance: A contingency and configuration perspective. Sustainability 2017, 9, 763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handoyo, S. Green supply chain management: A bibliometric analysis of global research trends and future directions. Prod. Manuf. Res. 2024, 12, 2422614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyapong, A.; Aidoo, S.O.; Acquaah, M.; Akomea, S. Environmental orientation and sustainability performance: The mediated moderation effects of green supply chain management practices and institutional pressure. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 430, 139592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hejazi, T.M.; Habani, A.M. Impact of green supply chain integration management on business performance: A mediating role of supply chain resilience and innovation the case of Saudi Arabian manufacturing sector. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2024, 11, 2392256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, T.; Sheng, H.; Li, M. The bright and dark sides of green customer integration (GCI): Evidence from Chinese manufacturers. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2021, 27, 1610–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahi, P.; Searcy, C. A comparative literature analysis of definitions for green and sustainable supply chain management. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 52, 329–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandenburg, M.; Govindan, K.; Sarkis, J.; Seuring, S. Quantitative models for sustainable supply chain management: Developments and directions. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2014, 233, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Zhang, H.Y.; Xiao, T.; Liu, J.; Chai, C.; Zhou, P. Impacts of external involvement on new product development performance: Moderating role of organisational culture. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2021, 33, 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.Y.; Yang, F. The impact of external involvement on new product market performance: An analysis of mediation and moderation. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2016, 116, 1520–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, G.J.; John-Mariadoss, B.; Kuzmich, D.; Qualls, W.J. The timing of diverse external stakeholder involvement during interfirm open innovation: The effects on new product speed to market and product lifespan. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2024, 117, 386–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, T.; Feng, T. Enhancing supply chain resilience: The role of big data analytics capability and organizational ambidexterity. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2025, 125, 2348–2370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parente, R.C.; Baack, D.W.; Hahn, E.D. The effect of supply chain integration, modular production, and cultural distance on new product development: A dynamic capabilities approach. J. Int. Manag. 2011, 17, 278–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Huo, B. The impact of green supply chain integration on sustainable performance. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2020, 120, 657–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, L.K.; Wong, Y.S.; Alzoubi, M.H.; Al Kurdi, B.; Alshurideh, M.T.; El Khatib, M. Adopting smart supply chain and smart technologies to improve operational performance in manufacturing industry. Int. J. Eng. Bus. Manag. 2023, 39, 95–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Ying, L.; Gao, M. The influence of intelligent manufacturing on financial performance and innovation performance: The case of China. Enterp. Inf. Syst. 2020, 14, 812–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goncalves, L.; Patricio, L. From smart technologies to value cocreation and customer engagement with smart energy services. Energy Policy 2022, 170, 113249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, K.; Jin, Z.; Wu, G. Unveiling the role of artificial intelligence in influencing enterprise environmental performance: Evidence from China. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 440, 140934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cockburn, L.M.; Henderson, R.; Stern, S. The impact of artificial intelligence on exploratory analysis. In The Economics of Artificial Intelligence; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2018; pp. 115–146. [Google Scholar]

- Haug, A.; Wickstrom, K.A.; Stentoft, J.; Philipsen, K. The impact of information technology on product innovation in SMEs: The role of technological orientation. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2020, 7, 384–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, M.J.; Liu, Y.; Fang, W.; Feng, T. Intelligent manufacturing for strengthening operational resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic: A dynamic capability theory perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 267, 109078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Thurasamy, R. Green supply chain integration and sustainable performance in pharmaceutical industry of China: A moderated mediation model. System 2025, 13, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Zhang, H.Y. The impact of customer orientation on new product development performance: The role of top management support. Int. J. Prod. Perform. Manag. 2018, 67, 590–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavez, R.; Yu, W.; Feng, M.; Wiengarten, F. The effect of customer-centric green supply chain management on operational performance and customer satisfaction. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2016, 25, 205–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, T.; Wang, D. Supply chain involvement for better product development performance. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2013, 113, 190–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Huo, B.; Flynn, B.B.; Yeung, J.H.Y. The impact of power and relationship commitment on the integration between manufacturers and customers in a supply chain. J. Oper. Manag. 2008, 26, 368–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foumani, M.; Smith-Miles, K. The impact of various carbon reduction policies on green flowshop scheduling. Appl. Energy 2019, 249, 300–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, K.J.; Handfield, R.B.; Ragatz, G.L. Supplier integration into new product development: Coordinating product, process and supply chain design. J. Oper. Manag. 2005, 23, 371–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajaguru, R.; Matanda, M.J. Effects of inter-organizational compatibility on supply chain capabilities: Exploring the mediating role of inter organizational information systems (IOIS) integration. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2013, 42, 620–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovanni, P.D. Do internal and external environmental management contribute to the triple bottom line? Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2012, 32, 265–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. Accounting for the triple bottom line. Meas. Bus. Excell. 1998, 2, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. Partnerships from cannibals with forks: The triple bottom line of 21st-century business. Environ. Qual. Manag. 1998, 8, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensson, G.; Hogevold, N.; Ferro, C.; Varela, J.C.S.; Padin, C. A triple bottom line dominant logic for business sustainability: Framework and empirical findings. J. Bus. Bus. Mark. 2016, 23, 153–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Sun, H. Green innovation strategy and ambidextrous green innovation: The mediating effects of green supply chain integration. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Tse, Y.; Yu, Y.; Huang, H.; Zhao, X. Managing quality risk in supply chain to drive firm’s quality performance: The mediating role of supply chain quality integration. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2025, 125, 797–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Sarkis, J.; Lai, K. Institutional-based antecedents and performance outcomes of internal and external green supply chain management practices. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2013, 19, 106–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, T.; Sun, L.; Sohal, A.S.; Wang, D. External involvement and firm performance: Is time-to-market of new products a missing link? Int. J. Prod. Res. 2014, 52, 727–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asamoah, D.; Acquah, I.N.; Nuertey, D.; Agyei-Owusu, B.; Kumi, C.A. Unpacking the role of green absorptive capacity in the relationship between green supply chain management practices and firm performance. Benchmarking Int. J. 2024, 31, 2793–2818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visamitanan, K.; Assarut, N. Impact of Green Supply Chain Management Practices on Employee Engagement and Organizational Commitment: Mediating Role of Firm Performance. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2024, 25, 1336–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Li, P.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, B.; Zang, J.; Meng, L. Toward new-generation intelligent manufacturing. Engineering 2018, 4, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.Q.; Xu, X.; Wang, L.H. Smart manufacturing process and system automation-A critical review of the standard sand envisioned scenarios. J. Manuf. Syst. 2020, 56, 312–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, R.Y.; Xu, C.; Chen, C.; Huang, G.Q. Big data analytics for physical Internet-based Intelligent manufacturing shop floors. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2015, 55, 2610–2621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y. Digital and intelligent empowerment: Can big data capability drive green process innovation of manufacturing enterprises? J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 377, 134261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Huo, B.; Selen, W.; Yeung, J.H.Y. The impact of internal integration and relationship commitment on external integration. J. Oper. Manag. 2011, 29, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Sarkis, J.; Geng, Y. Green supply chain management in China: Pressures, practices and performance. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2005, 25, 449–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vachon, S.; Klassen, R.D. Extending green practices across the supply chain: The impact of upstream and downstream integration. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2006, 26, 795–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, I.J.; Paulraj, A. Towards a theory of supply chain management: The constructs and measurements. J. Oper. Manag. 2004, 22, 119–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, B.B.; Huo, B.; Zhao, X. The impact of supply chain integration on performance: A contingency and configuration approach. J. Oper. Manag. 2010, 28, 58–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darnell, N.; Corley, C.A.; Handfield, R. Environmental management systems and green supply chain management: Complementary or redundant? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2010, 17, 30–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.C. The influence of green supply chain integration and environmental uncertainty on green innovation in Taiwan’s IT industry. Supply Chain Manag. 2013, 18, 539–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyer, K.K.; Verma, R. Multiple raters in survey-based operations management research: A review and tutorial. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2010, 9, 128–140. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. Commentary: Issues and opinion on structural equation modeling. MIS Q. 1998, 22, 7–16. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. ‘Fit for 55’: Delivering the EU’s 2030 Climate Target on the way to climate neutrality. COM(2021) 550 final. Brussels. 2021. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:52021DC0550 (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Appelbaum, E. Improving the efficacy of carbon tax policies. J. Gov. Econ. 2021, 4, 100027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).