Abstract

This research examines the drivers of lean implementation in sustainable energy enterprises (SEEs) to balance efficiency, sustainability, and competitiveness. This research investigates the interdependence among lean drivers and classifies them by driving power and dependence. This study followed a novel mixed-method approach combining a systematic literature review for driver identification, interviews with entrepreneurs for expert consensus, and analysis using total interpretive structural modelling (TISM), cross-impact matrix multiplication applied to classification (MICMAC), and a graph-theoretic approach (GTA). The result indicated that leadership commitment, teamwork and collaboration, and time management are high drivers; cost reduction, resource optimization, and continuous improvement are linkage drivers; and customer focus and flexibility are found as dependent drivers, revealing the sustainable outcome. This provides a structured pathway for the SEEs for the lean implementation drivers, where prioritization is required. The exploration adds to the Resource-Based View, dynamic capability theory, system theory, etc. The study calls for policymakers’ interventions in designing capacity-building programmes, leadership training, and collaborations. This research incorporated the antecedents–decisions–outcomes (ADO) framework for highlighting the antecedents, leading to decisions, and the outcomes of the choices, with future research questions connecting with multiple sustainable development goals (SDGs), such as SDG7, SDG9, SDG12, and SDG13.

1. Introduction

The change towards urgency for renewable energy is based on the desire to ensure energy security, reduce climate risks, and mitigate degradation [1,2]. Even though they have significant relevance and demand, sustainable energy entrepreneurs are facing challenges in terms of less availability of resources, operational inefficiencies, and financial risks [3,4]. Lean management, focusing on waste reduction and value generation, has an impact on various sectors. The sustainable energy sector is one of the leading forces of the ever-growing nations aiming for sustainable development. Lean implementation in the energy sector is limited to small and micro enterprises (SMEs) [5,6].

Green and lean sustainability in SMEs requires leadership, employee participation, strategies, and the measurement of performance factors [5]. This conceptual study does not analyze the interdependence of the factors impacting lean implementation in the energy sector. Moghadam et al. [4] highlighted the importance of a closed-loop supply chain in solar photovoltaic and wind energy in a multi-objective optimization model comprising lean and circular economy principles. This only focuses on the supply chain aspect. The application of Industry 4.0 technologies for energy efficiency results in 25% gain with quality management systems [7]. This major emphasis on the improvements in energy efficiency was not able to cover the lean factors influencing the SEEs.

Atuahene and Sheng [2] examined power sector dynamics, highlighting that renewables are not widely used due to inefficiencies in economic policy support, emphasizing the macro-level barriers and not covering the operational aspects. Sadik-Zada and Gatto [8] emphasized the importance of policy for learner models at a strategic level, but this does not cover an enterprise-level lean integration. Duch-Brown and Rossetti [6] focused on digital tools for improving the efficiency of the micro-enterprise in energy motoring, which lacks the lean principle of continuous improvement. Böhmecke-Schwafert and Moreno [9] also assess the role of blockchain in prediction in the solar renewable sector, not addressing the factors of lean implementation in resource-limited energy enterprises.

Lean principles are important in entrepreneurship operations, especially the minimization of wastage, and in enhancing efficiency, also contributing to innovation and competitiveness. However, the application of lean implementation in SEEs is examined less specifically in terms of how the interaction of lean drivers leads to operational efficiency. Lean entrepreneurship is not a new field. The existing works, like Sudhir et al. [10], examine the Lean Startup Method (LSM) and highlight that funding inefficiency affects experimentation and leads to less learning than finance. Tucci et al. [11] emphasize that “Lean Startup” is not a “giant leap” and needs contextual clarity. This highlights the limited research examining how lean drivers contribute to improving operational efficiency in sustainability-driven enterprises. Green and lean integration helps reduce emissions [12], and Lean Six Sigma in green production with a circular economy [13] enhances the SMEs’ performances.

While these studies reveal important synergies between lean implementation and sustainability, they are more focused on industrial and SME contexts; renewable or sustainable energy entrepreneurship is unexamined. This study aims to address the challenge by examining the interdependence and identifying the driving power and dependence among the drivers of lean implementation. The interconnection of lean implementation and sustainability is examined in SMEs, but existing research do not explore the interactions between drivers of lean implementation in the SEE context. This is essential due to the functioning of SEEs in more competitive and resource-constrained environments. This is also significant due to their contribution to SDGs and sustainability targets. The focus of the above studies on lean, green technologies for improving operational efficiencies and integrating sustainability does not address how lean practices help in the operational efficiency of SEEs and the interdependence of drivers. Hence, the study opted to follow the following research questions:

- What is the interdependence level of the drivers of lean implementation in enhancing the operational efficiency of SEEs?

- How do we classify the drivers of lean implementation in SEEs based on the driving power and dependence?

This research follows a novel and structured approach consisting of TISM and MICMAC analysis for examining research questions integrated with the antecedents–decisions–outcomes (ADO) framework for proposing future research directions. The study is also novel due to filling the methodology gap. Multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) tools, such as TISM, are significant in studying hierarchical relationships, and MICMAC analysis is good for classifying the factors based on the driving power and dependence [14,15]. Lean assessment of SEEs through the GTA is another approach, which can provide practitioners with insight into the lean index and on where prioritization is required, as well as how to improve current lean practice, other than conventional isolated rating by traditional methods, replaced with the performance rating through a graph-theoretic approach (GTA), along with proposing suggestions for improvements. ADO is also effective for establishing logical stances into three components [16], which is helpful here for identifying drivers, decisions, and consequences guiding both theory and practice for entrepreneurs, policymakers, and investors aligned with the SDGs for developing effective business models, support, and formulation of polices in sustainable energy. This study helps in contributing to existing literature on entrepreneurship and energy research regarding the drivers of lean practices in SEEs’ operational efficiency and calls for policymakers’ intervention, leading to sustainable development.

The paper is organized into eight sections, starting with Section 1 as an introduction describing the context, significance, research questions, background, and a brief overview of the methods adopted and implications of this research. Section 2, as a literature review, mainly synthesizes the existing literature and a discussion on the identified factors. The methodology is discussed in detail, along with the framework, in Section 3. Section 4 discusses the results of the TISM, MICMAC, and graph-theoretic approach analysis, followed by Section 5 as a Discussion Section explaining the comparison of the study findings with previous research works. The implications for theory, practice, and policy are outlined in Section 6, followed by the future research direction with ADO included in Section 7. Finally, the conclusion, Section 8, presents the overall findings, novelty, and implications of this research in a nutshell.

2. Literature Review

The significance of lean implementation and lean practices that are adopted in SEEs is discussed in this section.

2.1. Importance of Lean Implementation

Lean implementation focuses on cost reduction and value creation through continuous improvement, in which demand is predictable [17]. The core of the lean philosophy focuses on time and effort in the inclusion and elimination of unnecessary operations that create value and reduce waste or unnecessary phases in the process that generate value [18]. It is relevant in both the manufacturing and service sectors due to its effect in enhancing operations, including workspace, resource allocation, customer-oriented focus, cost-effective and less resource-consuming processes, etc. [19]. The maximization of performance and the minimization of costs are the core aspects [20]. Lean implementation excludes the non-value-added activities in the process [21]. Lean implementation increases efficiency, quality, and the ability to offer good, responsive services to customers [19]. The adoption of lean principles changes organizations to be reliant on value creation and configuration, which is people-oriented [22]. The lean principles are based on the optimization of operations, which are focused on the reduction of waste in processes and ensuring synergy. Lean implementation and environmental sustainability are related, and lean methodologies contribute to a greener industrial climate [21].

The five major lean principles that ensure proper and prompt customer value and the elimination of waste in operations are value, focusing on the perspective of the end customer; ensuring that the process is oriented toward meeting the customer demands; value stream, which is identifying the wastages and the inefficiencies in the process by tracking the flow of raw materials, information, and value from the customer point of view; the impact of flow on the development of processes in the value system by eliminating the hurdles and reducing the batch sizes, and also ensuring continuous and smooth operations; pull, the principle that deals with system setup based on the request of the customer, rather than push; and perfection, focusing on continuous improvement by reducing the waste and enhancing the process to satisfy the customers [19,23]. The deviation can be solved through continuous practice and the elimination of waste [19].

Value-added activities mainly increase the quality of products and services, satisfying the customers [24]. Non-value-added activities do not have a direct impact on quality, functionality, etc., but create waste and do not generate any customer value. The non-value-added activities should be identified and reduced to ensure the proper optimization of resources. This will enhance the efficiency, optimization, and proper allocation of resources relating to lean thinking [19]. The main objective of lean implementation is continuous improvement, which helps firms to reduce costs and increase efficiency, enhance the process, and reduce overall waste, which leads to satisfying customers. Lean thinking is oriented with contemporary goals, including quality, productivity, responsiveness, etc., along with conventional goals like profitability and efficiency [21]. There are eight major types of waste. They are transportation, inventory, motion, waiting, overproduction, overprocessing, defect, and ineffectively used people [19].

2.2. Lean Practices in SEEs

Lean principles and sustainability are the essential pillars of entrepreneurial success [5]. Solar and wind energy enterprises are facing high competition in the current world, and they are also facing challenges in terms of the costs, waste, and resource limitations [25]. The lean principles help in the balancing of sustainability and efficiency in operations [21]. Lean practices will improve manufacturing efficiency, and they are integrated into the SEEs for increasing long-term viability and performance enhancement [21,26]. For this, Value Stream Mapping (VSM) and other tools are used for determining the impact and reducing the waste [21]. Lean implementation is not only about reducing the costs, but also helps in achieving sustainability targets and goals, helps the enterprises to satisfy their customers efficiently, and aids in providing innovative green or clean energy solutions [27].

Environmental management systems (EMS) help in process innovation and increase resilience [28]. Just-In-Time (JIT), Total Quality Management (TQM), and 5S methodology (Sort, Set in Order, Shine, Standardize, Sustain) techniques increase efficiency, reduce energy loss, and produce defectless solutions [29]. Artificial Intelligence (AI), Internet of Things (IoT), Big Data, and Robotics are the Industry 4.0 technologies that help energy-reliant sustainable enterprises to increase energy efficiency from the 15–25% average, along with quality management and the optimization of processes [7].

The implementation of lean and green practices or strategies in SMEs is at risk due to resource constraints and reluctance. The green and lean sustainability framework is the guiding light for the integration of sustainability elements in the process [5]. The mix of lean implementation and green principles will improve sustainability and operational efficiency [28]. Solar and wind energy solutions, having long-term life and reliability, are leading SEEs to adopt models of closed-loop supply chains and the integration of reverse logistics for circular economy practices like reuse and recycling to increase environmental and social value [4]. This helps in addressing resource constraints regarding solar radiation and the speed of wind.

Developing countries like Ghana are dependent on fossil fuels, and less focus is placed on integrating renewable energy proportions into their total energy mix [2]. Whilst most countries are focused on energy transition, this is not immediate, and still, carbon-based energy sources are prevailing in energy security, highlighting the importance of a balanced approach in integrating lean principles [8]. High competition is one of the challenges for solar energy enterprises. In addition to this, cost and wastage are other issues. The lean principles, like pull and the flow, will mitigate and manage the balancing of sustainability and economic efficiency barriers [25].

3. Research Methodology

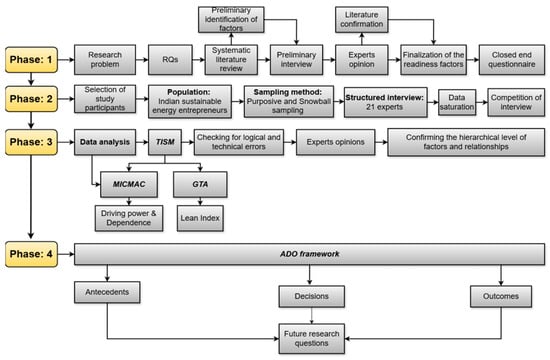

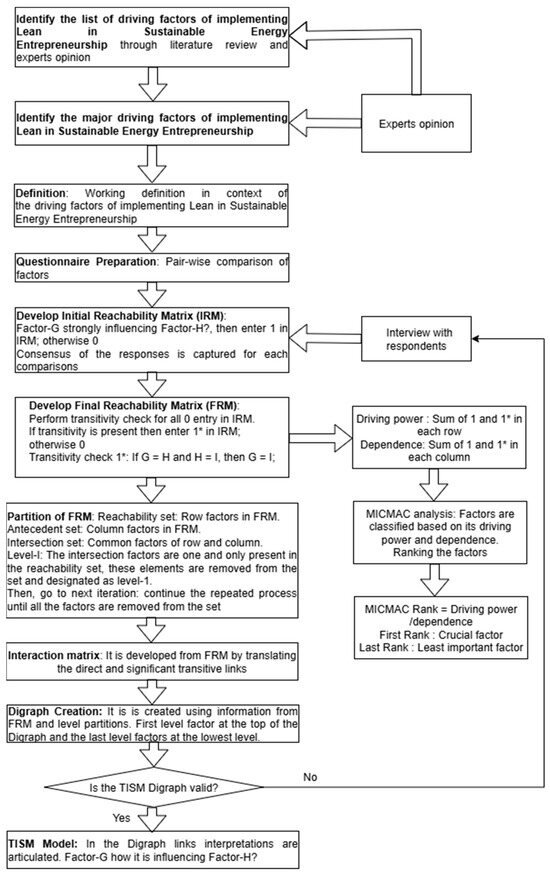

Refer to Figure 1 below for the adopted research framework in four phases. This section presents the identification of literature documents, their screening, and their eligibility assessment, followed by the criteria for expert selection and the methodology employed for preliminary and subsequently structured interviews with experts. In addition, it presents the important drivers that have been identified for the deployment of lean implementation in SEEs. The TISM methodology is used to identify the interdependence of the identified lean implementation driving factors. TISM not only captures relationships but also the interpretive logic among the hierarchical levels of influence, providing a structure of influence in the system [3]. Similarly, MICMAC analysis is used to understand the lean implementation driving factors that fall into four quadrants: driving, dependence, linkage, and autonomous zone. Finally, the graph-theoretic approach (GTA) is presented to assess the impact of the drivers of lean implementation as a case study through a quantitative index considering both direct and indirect influences in a single composite measure. Sensitivity analysis is utilized to figure out the underlying driving factors.

Figure 1.

Research framework.

Other MCDM techniques like Decision-Making Trial and Evaluation Laboratory (DEMATEL), Analytic Network Process (ANP), and Fuzzy-Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP) were used in the research while examining the interrelationship, hierarchical prioritization, etc. DEMATEL is used for assessing causal relationships by revealing cause and effect among factors [30], but it does not provide interpretive depth with adequate reasoning or justification provided in TISM. Likewise, DEMATEL does not provide any link to the system-level index, as the lean index was developed through GTA. ANP is suitable for examining interdependence when there are large, steady, and highly consistent pairwise observations [31]. This may not be suitable for the small, heterogeneous SEEs operating in an emerging sustainability environment. Likewise, Fuzzy-AHP is used for weighting independent criteria or parameters when expert opinions are uncertain or imprecise [31,32]. This lacks contextual interactions. Hence, the focus of the study is not covered or satisfied here. Therefore, the combined novel approach of TISM-MICMAC-GTA will help in the examination of (i) interpretive modelling, (ii) structural hierarchy mapping by classifying based on driving power and dependence, and (iii) quantitative index computation suitable for the comprehensive relational, expert-driven study in SEEs. These details are presented here in the following subsections.

3.1. Literature Identification, Screening, and Eligibility Assessment

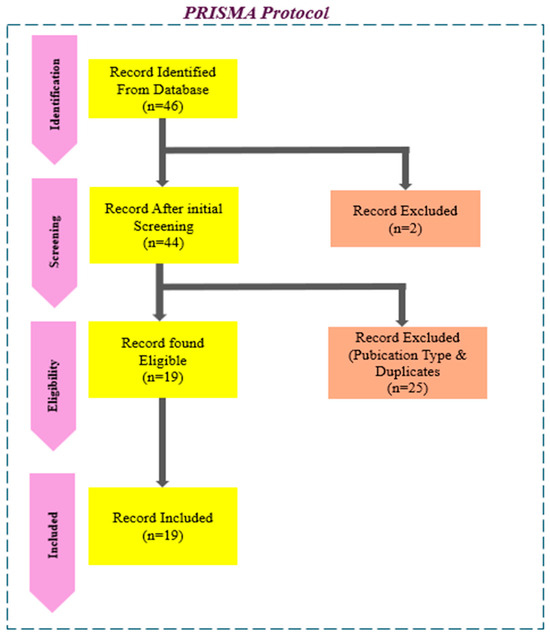

The systematic literature review is conducted to identify the drivers of lean practices in SEEs based on the PRISMA protocol. The process is carried out in four phases. PRISMA helps in ensuring replicability and enables transparent search and selection [33,34]. The PRISMA diagram presented in Figure 2 shows the complete phases. Identification of factors is the first step that involves a preliminary search of the literature in the selected databases during a time frame based on search keywords.

Figure 2.

PRISMA model.

Scopus, Web of Science (WoS), and Dimension are prominent databases selected to ensure high-quality publications, covering interdisciplinary studies, and the possibility of an exact and comprehensive search through Boolean operators. No limit is placed on search period, and the following search strings were adopted: (“Lean” OR “Lean Implementation” OR “Lean Management” OR “Green Lean” OR “Sustainable Lean”) AND (“enterprises” OR “startups”) AND (“sustainable energy” OR “clean energy” OR “renewable energy” OR “green energy”). A total of 46 documents were identified.

To perform factor screening, filtration is applied to the database, and only the English language is followed. The two non-English-language published papers have been removed. Among 44 documents, 4 Scopus articles, 8 conference papers, 4 conference reviews, 7 Web of Science articles, 3 proceeding papers, 2 published news items, 2 review articles, and 1 editorial are featured. In Dimensions, seven articles, four proceedings, and three chapters were found. Among these, the article and review articles are considered high-quality documents, and we exclude other lower-quality publications for review. Hence, only 20 were selected. One paper found to be a duplicate was not selected. The selected number of documents is 19 published papers that meet the eligibility based on criteria for inclusion and are finally selected for review.

3.2. Experts’ Selection and Their Interview Methodology

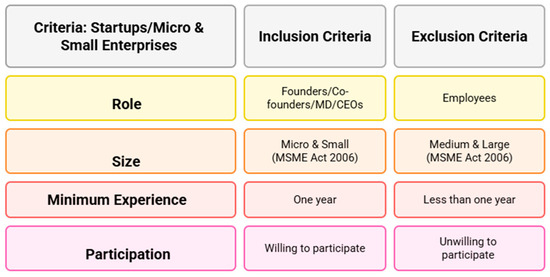

To identify lean implementation driving factors through the literature review in the above phase, we interviewed experts in the sustainable energy field. These interviews were conducted to check the identified factors with the experts’ consensus, preparing for the move to the actual interview and further analysis. In this qualitative approach, the objective is to confirm the most influential lean drivers in SEEs based on the consensus of the experts in this field. This method will ensure the validity of the factors. This was applied by existing studies (Sushil [35] and Agarwal et al. [36]). This study is undertaken in the context of a developing or emerging economy, like India. India’s focus on clean and sustainable energy with institutional support and the emerging entrepreneurial ecosystem, as well as the drive for achieving sustainable development by 2030 and Vision Viksit Bharat by 2047, are making the study area more relevant and essential [3]. The Likert scale-rated questionnaire is followed by expert consensus. The 21 SEEs involved in the study were selected based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria presented in Figure 3. TISM, MICMAC, and GTA rely on expert opinion rather than statistical sampling. Therefore, expert selection is based on knowledge and experience in the domain. For this, explicit, pre-defined inclusion and exclusion criteria (Figure 3) are followed. This is to enhance informative power and interpretative validity, rather than random representativeness, and ensure consistency with the logic of qualitative structural modelling [35,36]. The founders/co-founders, MDs/CEOs, accredited energy auditors, and senior consultants running enterprises with direct engagement in the sustainable energy sector and lean/energy-efficiency practices, with 1 year to 36 years of experience, were considered. They represent sustainable energy startups, energy consultancies, and energy auditing firms. This avoids bias from participants lacking domain knowledge, excludes employees without decision-making authority, and prevents contextual bias and structural bias by focusing only on micro and small SEEs rather than medium/large firms (as per the MSME Act 2006), and also ensures contextual equivalence. The exclusion of employees helps to avoid role bias and mixing of tactical-level and strategic-level interpretations, and the study incorporates only entrepreneurs’ perceptions. These criteria ensure high relevance, comparable experience, and reliable interpretations, which are essential for expert-based modelling. This is for the study focusing on startups, micro and small SEEs that are struggling with financial, infrastructure, and technology hurdles compared to the large and medium-sized enterprises. This focus on early-stage to more successful experienced ventures captures the need for diverse but experienced experts who understand lean implementation and operational realities in SEEs.

Figure 3.

Selection criteria of experts.

The participants are selected through purposive sampling and snowball sampling to ensure that the respondents involved in this research have adequate knowledge of the subject. This form of integrative sampling was proven to be better in studies (Alka et al. [3], Alka et al. [37]) on the successful development of technological innovation in SEE contexts, as well as regarding the socioeconomic factors influencing SEEs (Zhao et al. [38], Sreenivasan and Suresh [39]). The interview is conducted within a duration of 45 min to 1 h in person or through video conferencing. The interview is conducted among the SEEs in various parts of India to identify the relationship between the drivers. The population of the study is Indian sustainable energy entrepreneurs.

TISM, MICMAC, and GTA focus on expert knowledge quality for identifying validated relationships among drivers, not statistical generalization. In this expert-based modelling, it mostly needs 10–30 experts for a consensus in pairwise opinions [35]. The selection of respondents through strict inclusion criteria (Figure 3) from sustainable energy enterprises with direct experience in lean or energy-efficiency practices, along with domain knowledge or understanding, ensures relevant and high-value or rich interpretations or judgments.

Twenty-one is the sample size of the study. This is a low sample size for conducting a first-hand information-based exploration. This value is not initially fixed, and the TISM and MICMAC require a lower sample size. There are examples of this: Kaur et al. [40] conducted a study on emotional intelligence with 7 interviews, Dalvi-Esfahani et al. [30] explored green computing with a sample size of 15, and Kharb et al. [41] investigated green financing with 8 study participants’ observations. Hence, this sample size in this qualitative interpretive structural modelling lies within the recommended range for interpretive modelling of 10–30 experts. TISM and MICMAC are useful for theory-building and decision-making [3]. Hence, theoretical saturation is most important while adopting these methods. Therefore, while fixing the sample size, the next reason—data saturation—also needs to be considered. Theoretical saturation is one of the major criteria for fixing the sample. In the interview with the respondents, after the 21st one, we noticed no new of factor relationships compared to those earlier. Repeating the same set of relationships is not good for the analysis, and they have no utility for identifying meaningful connections [3]. This theoretical saturation highlights that there is no further inter-relationship and no chance for unique interpretations, and does not improve model validity [3,37]. This logic follows the saturation guidelines in interpretive research [42]. The process is highlighted below to highlight that n = 21 is an adequate, justified, and methodologically defensible sample size. The data saturation is determined through a step-by-step process, not anecdotal observation. A structural saturation check (TISM/MICMAC requirement) is carried out. After each interview, the newly emerged driver relationships were compared against the accumulated interaction set. Saturation was considered and achieved when no new directional relationships, no new links, and no changes in factor hierarchy emerged in the last three consecutive interviews. After the 19th, 20th, and 21st interviews, the relationship set was identical, indicating clear structural saturation.

Along with this, a thematic saturation check with the interview code-sheet was conducted based on deductive reasoning using the pre-identified lean drivers. No new relationships or causal logic was at found after the 21st interview. Following this, a validation saturation check is conducted with each study participant expert to validate and confirm relationships. From the 19th interview onwards, expert clarifications fully aligned with previous responses, indicating interpretive saturation. Hence, this saturation is fixed based on the stable patterns of relationships that emerged with influencing relations among drivers, logic links, and hierarchical structures in the data set, confirmed from the experts’ opinion, not the researchers’ decisions. This is not the first study that has completed interviews based on data saturation. The study follows the same procedure as mentioned above in research such as Sushil [35], Alka et al. [3], Alka et al. [37], etc.

The identified factor relationships in this study are free from tautology and not based on self-assumptions. The study follows different procedures for this. The direct pairwise relationship in the final reachability matrix was included only when experts’ ratings were high or very high, and the experts had to provide a specific justification on what, why, and how. If a relationship is not directly linked or there is the presence of an indirect relationship among drivers, these are selected to check the transitivity. The transitivity check did not automatically assume indirect links. There should be transitive connections that were added only after experts re-validated the indirect relationship within their experience and explained how. If experts are not identified in an indirect relationship, the link is not considered. The GTA validation step with five senior practitioners ensured that every relationship matched the actual current practice level in SEE operations. The expert helps to avoid theoretically common but practically weak relationships at this stage.

Through these validations, including consensus, logic confirmation, the capture of all the relationships, the inclusion of transitivity checks, and practitioner verification, the TISM-MICMAC modelling process aims for theory-building and decision-making, ensuring that the final TISM-MICMAC-GTA analysis provides novel structural insights SEE lean practice.

3.3. Key Driving Factors for Lean Implementation

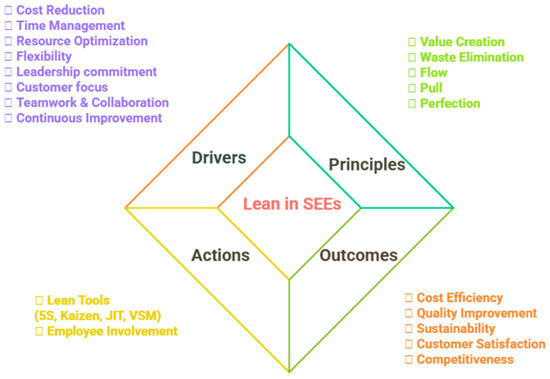

Eight key driving factors (DF1 to DF8) for lean implementation are identified from the literature review and confirmed through experts’ opinions as discussed below. The lean philosophy and its drivers, principles, actions, and outcomes are represented graphically (refer to Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Model of lean philosophy: drivers, principles, actions, and outcomes.

Cost Reduction (DF1): Cost reduction is the lean practice that includes waste reduction, improving efficiency, and ensuring resource optimization for reducing inefficiencies, resulting in minimizing expenditure [43]. Lean techniques that help in reducing inventory costs, reducing downtime, and eliminating non-value-added activities lead to improving quality and sustainability. These principles are applied to reduce inventory costs and improve operational flow in solar and wind production, without compromising the quality. Circular economy (CE) adoption also reduces the costs of materials, like the recycling of lithium-ion batteries, further reducing material expenses and developing a less costly enterprise structure [44,45]. Hence, this is one of the drivers for the adoption of lean implementation. Lean experimentation reduces the misallocation of resources in the early stages and develops a cost discipline in sustainable operations [10]. Here, it is related to economic efficiency outcomes along with technical and material efficiency.

Time Management (DF2): Time management refers to the planning, sequencing, and controlling operations with the aim of reducing lead time and unwanted delays [46]. Lean time management techniques like Value Stream Mapping promote the identification of the hurdles in the supply chain and resource optimization, which helps to reduce delays and ensure proper delivery of services. The JIT also reduces the high amount of inventory costs by ensuring the availability of the material at the right time. This will also reduce storage costs [46]. Proper time planning, organizing, and control help in managing tasks and ensuring the delivery of outputs within prefixed deadlines [47].

Time management through reducing lead times and avoiding inefficiency through delays is significant for SEEs. Lean tools like Value Stream Mapping can find out problems and inefficiencies and help in precise scheduling [7]. Modern tools in quality management are promoting enterprises to focus on more sustainability-oriented performance [48]. Here, this driver is focusing on the temporal efficiency, and proper management of time is essential for lean implementation.

Resource Optimization (DF3): The optimization of resources is mainly defined as the maximum usage of material, technological, and labour resources to maximize output and reduce waste, increasing efficiency and environmental responsibility through the reduction of waste generation [49,50]. The optimization of wind turbines, solar cells, metals, energy storage systems, etc., is included in SEEs. Lean Six Sigma helps with production inefficiencies and also focuses on the effectiveness of the usage of raw materials, which include silicon and solar panels. The circular economy-driven practice also reduces energy consumption and costs by ensuring sustainability [51,52]. The application of a circular economy and lean adoption will enhance the efficiency of the materials essential for SEEs to survive in a competitive world, along with maintaining the focus on mitigating negative environmental impact through reducing carbon footprints [53]. Resource optimization focuses on optimum utilization of materials and process efficiency, whereas cost reduction (DF1) concentrates on financial advantage.

Flexibility (DF4): Flexibility refers to the ability to adapt to changing scenarios like fluctuation in demands, availability of resources, and technological change by eliminating inefficiency [54]. This is essential for managing energy output based on weather changes, integrating new clean technologies, and developing customized energy solutions. For this, the lean practices need to be integrated. Lean adoption is applied in the solar and wind industries through flexible manufacturing systems to ensure continuous production and customization [55]. Lean flexibility is also becoming important in energy storage and distribution networks. The grid and the demand-based response systems are developed based on the customer requirements, regulations, and technology developments in real time [52]. Information systems also aid lean implementation-driven outcomes through operations and sourcing through flexibility [56]. This driver is simply focusing on the adaptability to change.

Leadership Commitment (DF5): Leadership commitment is another driver of lean implementation in SEEs [3]. It is the continuous support and commitment of the leaders through providing resources, setting targets, creating a good environment, training, and involving employees in problem-solving through developing their skills in the optimization process, especially at the execution level. Hence, strong support and coordination at the enterprise level are some of the drivers for adopting lean implementation, which further influences the strategic level, also being a critical factor for implementation. The sustainable lean production system requires front-line lean leadership through training on a set of lean tools for activities and creating leadership capacities [57]. In the SEEs, leadership commitment is most important because client project competition with a lean focus requires adequate support from leaders such as entrepreneurs through training, budgets, monitoring, evaluation system tools, and investment in the technology. This is also important for lean implementation. Lean-mature entrepreneurs can increase the innovation behaviours among their employees [58]. This is significant for SEEs who are focusing on cleaner technologies.

Customer Focus (DF6): Customer focus is mainly related to the customer demand. The lean methods always prioritize customer value [59]. Quality Function Deployment (QFD) focuses on increasing customer satisfaction [60]. The energy consulting entrepreneurs are giving clarification and suggestions on where organizations need to reduce costs without reducing profitability [61]. The desire for customer satisfaction and their retention is one of the drivers for adopting lean practices. A clear understanding of the customer needs will help enterprises to create customer-desired products that offer maximum value while ensuring optimization at the operational level [62,63]. Customer demand aligns with products that meet standards and leads to an environmentally negative impact. The customers are also considered as key stakeholders in the sustainability goals, like sourcing more eco-friendly products, reducing the carbon footprint, and ensuring transparency without reducing accountability. In the context of SEEs, customer-focused energy system solutions will have reliability, feature lower costs, and avoid non-value-added activities, which will result in lean SEEs. Customer focus is a driver focusing on customer feedback, leading to continuous improvement, innovative efficiency, and clean solutions, as well as developing competitiveness and trust. This is an external condition-aligned driver compared with internally operational drivers, like resource optimization (DF3), etc.

Teamwork and Collaboration (DF7): Teamwork and collaboration are part of lean implementation [46]. Partnerships and collaboration are most important in the SEEs [3,37]. Lean methodology application is also related to employee support and the desire for improvement requirements [64]. Expertise sharing at the cross-department or functional level will help in the effective adoption [65]. Sharing knowledge and expertise to solve challenges through proper action towards goals by ensuring cross-functional coordination is also a driver for reducing waste and increasing operational efficiency [66]. Teamwork is more focused on collaborative operational behaviour compared to leadership commitment (DF5), coming under the strategic dimension.

Continuous Improvement (DF8): Continuous improvement is also one of the significant parts of lean implementation. The Kaizen method, focusing on small changes, is good and will enhance efficiency, reduce wastage, and increase sustainability [67]. The Plan–Do–Check–Act (PDCA) cycle helps in the optimization, identification, and implementation of corrective action. Lean Six Sigma methodologies promote the identification of defects and increase the quality of solar panels and wind turbines. Biomass and hydroelectric energy also increase the capacity and output through lean implementation [68,69]. All these highlight the importance of continuous improvements. This involves creating a learning and adaptation culture rather than mitigation and adaptation for identifying and solving inefficiencies through regular evaluation, applying lean solutions [68,69,70]. Continuous improvement can be enhanced through learning exposure and alignment, encouraging entrepreneurial behaviour among stakeholders to ensure the intention to partake in and achievement of the energy transition [71] in the long term.

Figure 4 shows a synthesis of lean implementation in the SEEs.

3.4. Identifying the Interdependence of Shortlisted Driving Factors for Lean Implementation

TISM is the best tool to identify the interdependence of factors. This is applied in the existing studies in energy research [72]. TISM is one of the MCDM techniques, which allows for answering the questions of what, why, and how the relationship evolved, whereas interpretive structural modelling (ISM) answers only the question of what. ISM is a garbage-in garbage-out process that does not consider indirect or transitivity relationships or path analysis [35,41]. The major steps (refer to Figure 5) for performing TISM analysis are explained below.

Figure 5.

TISM steps.

Step 1: Factor identification.

Step 2: Factor interdependencies: The factors identified are assessed pairwise to arrive the initial reachability matrix (IRM). Table 1 presents the IRM, which is valued as “1” for all influencing relationship pairs and “0” for not influencing based on consensus. IRM considers only initial influencing connections among the factors. This provides a clear picture of what factors are influencing and what are the non-influencing relationships with binary values [3]; “1” is given if the influencing relation has more than 75%. In simple terms, if the Likert scale rating is “high” or “very high”, then we can say that there is an influencing relationship.

Table 1.

IRM for lean implementation drivers of sustainable energy entrepreneurship.

Step 3: Interpretation of factor influence: The interpretation of why the factors’ relationship exists and how they influence one another is performed from the experts’ consensus [41].

Step 4: Transitivity check: All the entries of ‘0’ in the IRM are checked for a transitive relationship [73]. It means if factor K influences factor L, factor L influences factor M, so factor K also influences factor M. This is denoted as first-level transitivity (1*).

Step 5: Final reachability matrix (FRM): FRM is derived from the IRM. The IRM is a matrix that contains direct as well as indirect influencing relationships, which contains transitive relationship, ensuring to account for of all kinds of influences, after confirming with the experts. Hence, in FRM (Table 2), we can see the entries which are 1, 1*, and 0, where Where one represents direct influence, 1* means transitive, and 0 means no influence.

Table 2.

FRM for lean implementation drivers of sustainable energy entrepreneurship.

Step 6: Partition reachability matrix (PRM): PRM is derived from FRM [73,74]. The FRM helps to determine the reachability set (influencing factors) and the antecedent set. Then, the intersection of these two sets is identified. The top-level factors in the hierarchical model are the factors that belong to both the reachability set and the antecedent set. After this identification, these factors are then explored and considered in the next order through the iteration process up to the completion of the hierarchical model of all factors. The direct and significant transitive links are based on the interaction matrix (Table 3).

Table 3.

Interaction matrix.

Step 7: Creating the TISM digraph: This is the preparation of the hierarchical model after considering all the relationships and the iterative process. This diagram features, which is in different levels, starting from the top-level or first-level factors to the last-level factors. Arrows are used to highlight the direction of the relationship. Direct arrows are used to represent a direct relationship, and arrows with dots denote a transitive relationship.

Subsequently, MICMAC analysis is carried out after TISM to understand the factors that fall into the four quadrants: driving, dependence, linkage, and autonomous zone.

3.5. MICMAC

Integrated application of MICMAC and TISM guides accurate decision-making [58]. MICMAC and TISM are theory-building approaches that help in the direction of further research. The phases of adopting MICMAC start from the identification of factors, followed by the process of ranking the interdependence, and then dividing the factors into four zones based on the driving power and dependence. Kharb et al. [41] highlighted that the MICMAC diagram presents the factors falling into four zones. The x-axis in the diagram represents dependence, and the y-axis shows driving power. MICMAC has the feature of a lower chance of errors compared to the rest of the methods and shows very simple classification of the factors guiding decision-making [3,37]. The four zones are denoted the follows:

Autonomous factor: Factors with less driving power and dependence fall into this zone [3,74].

Dependent factors: These factors have low driving power and high dependence, indicating they are dependent on other factors. These factors do not have the ability to change the other factors, which means they are dependent and not driving factors.

Linkage factors: This zone shows the factors that have high driving power and dependence. The factors in this cluster have an interlinking power of connecting independent and dependent factors [71].

Driving factors: In this quadrant, the factors that have low dependence and high driving power are presented. This is the zone opposite to the dependent factors (Zone II) [75].

Lastly, the graph-theoretic approach (GTA) is adopted to assess the impact of the drivers of lean implementation as a case study. A sensitivity analysis is also performed to figure out the influencing lean implementation driving factors. The details are presented here in the following subsections.

3.6. Graph-Theoretic Approach (GTA)

The case organization in this research is XYZ, a small enterprise that has been working for over a decade, serving more than 1000 clients in industrial, commercial, and institutional sectors across multiple states in India. This venture operates as a sustainable energy consultancy, one of the important areas of the sustainable energy sector. The firm has 27 professionals, including 3 full-time certified energy auditors, 9 associated energy auditors, 8 renewable energy engineers, 4 safety experts, and 3 data analysts, providing advisory services in designing, energy auditing, energy performance indicator assessment, guiding energy-saving avenues, feasibility analysis, performance benchmarking, process optimization assistance, and suggestions relying on technologies for energy efficiency to clients. The clients are from chemical industries, educational institutions, hospitals, and distribution companies. Approximately 100–140 projects are completed per year, including walk-through audits, detailed energy audits, thermal imaging surveys, solar feasibility assessments, and sustainability compliance services, such as Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) commissioning, Energy Conservation Building Code (ECBC) compliance, and safety audits (industrial and building safety).

To understand the drivers of lean implementation assessment, the-graph theoretic approach (GTA) was used. This was applied in the existing studies on lean assessment, such as Vadivel et al. [76], Gurumurthy et al. [77], Santos et al. [78], Lande et al. [79], and Suresh et al. [80], for understanding the current practice level. GTA combines the interrelationships among the lean driving factors and the ratings on the current practice level, indicating performance, to develop a lean index showing the lean implementation level in an enterprise [81,82]. Hence, the direction and interrelationships are considered here for providing a more concrete and precise assessment compared to less precise conventional assessment methods. The TISM is initially taken for the hierarchical interrelationships among the drivers identified from the 21 SEEs collected through a five-point scale, and then the experts’ opinions are taken as the input from the five experienced practitioners from the case enterprise, collected through a nine-point scale [83], as a validation for the assessment on lean implementation through GTA for the calculation of the permanent value to arrive at the lean index. Therefore, TISM and GTA were applied to understand the current lean practice level. The driving factors are determined through adopting a sensitivity analysis of the GTA.

The diagonal elements of the input matrix in GTA are the firm-specific performance level of each driver, while the off-diagonal elements are the strength and direction of influence among drivers. The TISM results from 21 domain experts are therefore used to provide a consistent and industry-level analysis. Using a GINA helps to map the current practice level in the organization [77,78,84]. This approach follows the GTA applied in previous particular case-based studies. For example, Ali et al. [83] used GTA to assess ISO 14000 soft-dimension performance in a single case organization; Gurumurthy et al. [77] applied GTA to evaluate organizational readiness for lean adoption in a one specific enterprise; Josyula et al. [84] assessed intelligent automation readiness in one multinational IT organization; and Lande et al. [79] evaluated Lean Six Sigma critical success factors within Indian SMEs. Josyula et al. [84] also follow the same structure: industry-level or expert-based structural interactions and firm-level performance ratings from the one core case organization. The logic is that structural dependencies are relatively stable in organizations, whereas performance levels may change contextually. Therefore, the methodological approach used here is completely aligned and followed by established GTA practice. TISM provides information on what, why, and how regarding influences to aid the structural system knowledge from a domain-expert group. The nine-point enterprise ratings provide how strongly the factor is currently practiced, revealing the contextual performance specific to the case organization. Both are required to compute the permanent value, which considers the holistic, system-level influence of lean drivers for the development of a lean index.

We integrate TISM interactions with the nine-point ratings because GTA requires expert-based structural relationships (off-diagonal values) and firm-specific performance levels (diagonal values) to compute a valid system lean index. Using industry-level interdependencies from the consensus of 21 experts, together with practice ratings from the focal enterprise, ensures that the model considers both general structural logic and context-specific actual practice level performance.

The four major steps involved in the GTA process are explained below [84]:

Step 1: Input decision matrix: In this stage, the rating on the current practice level in the case enterprise in the factors is represented by diagonal elements. The mode values of driving factors are presented in the diagonal values in input matrix A based on observations of practitioners. The values other than diagonal ones, such as off-diagonal values, are taken from the TISM interaction matrix, a five-point scale [84], along with the direct and significant transformative links from the 21 experts, also presented in input matrix A.

Step 2: Permanent value computation: The computation of the permanent matrix formula for 8 × 8 matrices [84] is given in Appendix A. The performance rating of each driver and their interrelationship strength with each other is considered in the permanent value, which is the single aggregated index. The integrated approach features every directional influence in the input matrix for the computation of the leanness score, rather than an independent approach to each factor taken separately. The permanent value is derived from the input matrix by multiplying the diagonal factor ratings by the corresponding interaction in all possible relations. This will ensure that both the standalone factor direct influences and interdependent effects are considered for the lean index. A simplified description is given here, and the complete mathematical equation in each step derivation is provided in Appendix A for better mathematical clarity.

The rationale for the permanent value is that it takes the holistic effect of all lean drivers within the system completely. The conventional way of taking each factor-level score in the aggregation methods is not able to capture the overall effect that is overcome through the permanent value computed based on both the direct ratings and the inter-factor influences. This will be helpful for the system-level analysis on how the lean drivers reinforce one another. This is essential in the content of the SEEs who are driving lean performance from process integration, cross-functional collaboration, and audit in multiple stages.

Step 3: Lean index computation: The permanent value is easily represented in a logarithmic term as Log10 (Per. A). Logarithmic permanent values are computed in different contexts and can be graded to obtain a 0–1 continuum [85]. Practical worst-case and best-case values are moved to the lean index with 0 and 1, in the rating continuum. Hence, the calculation of the lean index is given below:

The best case in practice is computed by changing the signal of the input matrix. This is performed through replacing the digital elements with the highest values if the rating here is nine, as highlighted in the second step. Likewise, the worst case involves replacing diagonal elements in the input matrix with the least or minimum rating value. Here, it is 1.

Step 4: Sensitivity analysis: The sensitivity analysis is adopted for understanding the triggering driving factors (the highest-ranking factor in the lean index) in the study context through the ranking based on the practice by the case SEEs. In simple terms, this involves taking an example of the sensitivity analysis of DF1 calculation by changing the rating of the DF1, with replacement of the maximum value of nine, to determine the permanent value (refer to step 2). Likewise, for all driving factors, the sensitivity analysis was conducted through the replacement of the corresponding value of the factor in the input matrix with a value of nine. The lean index in each case is computed, and the ranking is based on the highest value in the index. The important focus of the case study is on the triggering driving factor(s) for case energy enterprises, focusing on their lean index better.

The results of TISM, MICMAC, and the graph-theoretic approach analysis are discussed in the following section.

4. Results

The results of TISM, MICMAC, and the graph-theoretic approach analysis are discussed in this section.

4.1. TISM: Identify the Interdependence of Lean Implementation Driving Factors

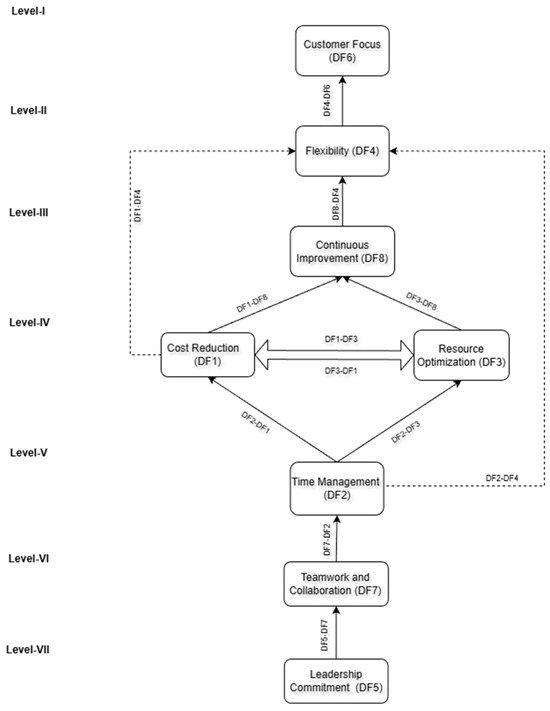

Level-by-level TISM graph interpretations of influential relations among the driving factors (refer to Figure 6) for lean implementation in SEEs are presented below.

Figure 6.

Influential relations among the driving factors for lean implementation in SEEs.

Level VII

DF5 influences DF7 (Leadership Commitment → Teamwork and Collaboration)

High leadership commitment helps in building teamwork and fostering collaboration. Leaders who have commitment will clearly state their vision, ensure resource allocation, and motivate employees. Clear commitment and strong leadership will also lead to collaborations in an efficient way. In the SEEs, leadership is the key player for developing cross-functional collaboration, which is essential for lean implementation. For example, in solar panel manufacturing, leaders are committed to ISO 14001 (environmental management) by clearly defining goals and ensuring quality, and collaboration and teamwork to reduce wastage. The energy consultancy firms, especially working as the SEEs, also integrate carbon neutrality with the collaboration of energy entrepreneurs working as sustainable energy consultants and their clients for developing an integrated sustainable energy solution to reduce unfavourable impacts. Hence, we can say that starting leadership commitment is an essential foundation factor and the key driver for operational efficiency through lean implementation in the SEEs.

Level VI

DF5 influences DF7 (Leadership Commitment → Teamwork and Collaboration)

Efficient teamwork will lead to efficient time management in the SEEs. Collaborative teams will help to avoid redundant work with proper planning, and also faster dissemination of the information or flow of decisions, and the process ensures accurate and timely completion of tasks in SEEs like installation, energy auditing, proper reporting, etc. In the case of the sustainable energy startups that are working at the enterprise level, the delays between manufacturing and logistics can be reduced through the minimization of unwanted delays regarding materials. The availability of wind turbine blades just in time on-site can reduce non-value-added activities. Similar to sustainable consultancy firms, collaborative planning and partnerships with data analytics will reduce delay, mitigate rework, and ensure the execution of projects on time, meeting the deadlines. Hence, we can say that teamwork and collaboration are helpful for reducing unwanted delays and time, and lead to time management.

Level V

DF2 influences DF1 (Time Management → Cost Reduction)

Time management helps to reduce costs in SEEs. Overtime, extra rework, wastage of resources, etc., can be minimized through proper, effective time management. The adherence to clear time schedules will reduce unwanted expenses, which increases cost creation. Solar rooftop installation projects being completed on time can reduce penalty costs from customers or clients, which also reduces the overtime labour charges. Hence, time management leads to reducing the unnecessary costs that may arise due to delay in the on-time completion of tasks.

DF2 influencing DF3 (Time Management → Resource Optimization)

Effective time management helps in efficient resource utilization. The proper completion as per the schedules will lead to reducing the idle time by optimum utilization of sources like manpower, machines, materials, capital, etc. Resource allocation also helps in ensuring the smooth flow of production and the proper energy audits. A major example for this is the project executed by the sustainable energy entrepreneurs in the biomass plant consultancy, in which the proper scheduling of the auditors, technicians, report preparation, etc., will reduce the idle gaps, and this will encourage efficiency.

DF2 → DF4 (Time Management → Flexibility)

Time management increases organizational flexibility. Proper competition can be achieved as per the deadlines, alongside faster adaptation to customer demands by changing the existing planning if needed. This enables agility. If time is predictable, then agility can be adopted, and proper management can be ensured. If the consultancy firms in the energy sector are completing their audit as per the schedule without taking more time than necessary, then they can also meet any other additional requests, revealing their flexibility.

Level IV

DF1 influencing DF3 (Cost Reduction → Resource Optimization)

Cost reduction helps in optimizing resources. Lowered costs will only necessitate lesser technology, fewer labourers, and capital efficiency. This is another driver for lean implementation in the SEEs. A solar production firm can minimize its electricity bills by developing in-house solar panels; at the same time, optimizing their resources will also reduce the costs. The SEEs optimize their resources when facing shortages in manpower, or any other shortage, and minimize expenses on energy losses and inefficiencies, leading to technological workflows. Avoiding defective manufacturing improves the optimization of resources.

DF3 → DF1 (Resource Optimization → Cost Reduction)

Resource optimization in an efficient way also contributes to waste reduction. The SEEs integrate circular economy practices like reusing, recycling, reducing, etc., leading to maximum utilization of the inputs. The energy consultancy firms are performing the optimization of labour to reduce labour and travel expenses in their different audits.

DF1 → DF8 (Cost Reduction → Continuous Improvement)

The Cost reduction promotes continuous improvement. Research and development innovation can be accelerated by reducing operational costs. The SEEs’ reinvestment in the new advanced cutting-edge tools, proper training, and integration of sustainable technologies will be helpful for continuous improvements. If there are high costs incurred from the operation, then the change is difficult to implement. The entrepreneurs who are managing the costs and encouraging cost-cutting startups can look for continuous improvement with small changes, and their aim is towards incremental adaptation and scalability. Cost reduction can develop continuous improvement as per these changes, and finance will not become a burden for adopting this lean practice, and it will drive successful lean integration in the SEEs. The solar energy startups are focusing their reinvesting profits or savings from their operations into research for more practical panel coatings that are more durable.

DF3 influencing DF8 (Resource Optimization → Continuous Improvement)

Resource optimization leads to continuous improvement. Efficiency of sources in terms of financial, human, and material resources will reduce waste. Efficiency can constitute continuous improvement because the elimination of waste promotes value-adding activities and also promotes small-level refinements. Innovation and training can be invested into resources like time, money, and energy from the freed-up resources. Efficient practices, including standardization, will encourage the teams to incorporate these improvements. Therefore, resource optimization leads to an increase in capacity, encouragement, and continuous improvement-driven systems, which also improve the sustainability and efficiency of the SEEs in a continuous and perpetual cycle.

DF1 influencing DF4 (Cost Reduction → Flexibility)

Reducing costs enhances organizational flexibility. The reallocation of resources is possible through cost reduction when new opportunities or contingencies for flexibility in terms of changes to customer demands, as well as modifying operations to comply with polices, which can be achieved through reducing costs, and this will also promote management to address disruptions.

Level III

DF8 influencing DF4 (Continuous Improvement → Flexibility)

Continuous improvement enhances adaptability. Continuous changes in process improvement make a firm agile and adaptable. The SEEs follow this culture, including techniques like the Kaizen method, which can integrate incremental adaptation. AI-based data analysis is an example of this. These ongoing refinements increase the flexibility of the SEEs and adaptation to external and internal environmental changes. Continuous improvement leads to developing a system based on lean, efficient, agile, and responsive principles. Research and development also help with flexibility. Continuous improvement also creates modular workflows, which increases problem-solving skills. The example in this case is the continuous improvement of the monitoring system in wind energy production, having the opportunity for operation reconfiguration and increasing the flexibility. Hence, continuous improvement leads to improvements in change readiness, creating high SEE flexibility.

Level II

DF4 → DF6 (Flexibility → Customer Focus)

Flexibility increases customer satisfaction. Adaptation to customer needs will increase the customer value creation, trust, and loyalty. SEEs’ solutions may be in designs, products, and audits that meet the customer demands through continuous adaptation, and encouraging a culture of flexibility will create a competitive advantage. Flexibility, operational adaptability, and customer focus will lead to developing a solution that aligns with the client’s demands. Flexibility is the key to customer focus. If SEEs lack flexibility and adaptability, this will lead to limited customer focus. Flexibility encourages customization, and flexible supply chains also ensure the on-time delivery of solutions and increase responsiveness; likewise, a flexible workforce and workflow also promote agile problem-solving. As an example, solar energy entrepreneurs may adjust their installation packages in terms of size, options of finance, etc., which highlights the important role of flexibility in SEEs in terms of increasing the customer focus.

Level I

DF6 (Customer Focus)

The major dependent factor identified in this research through TISM analysis is DF6 (Customer Focus). Lean implementation will help to ensure value delivery to the customers. The ultimate aim of the SEEs, like any other enterprise, is customer value and satisfaction. All improvements in terms of cost reduction, time management, flexibility, developing teamwork and collaboration, resources, continuous improvement, etc., will help in the delivery of customer values. Customer-centric operations are the key to long-term sustainability and increasing competitiveness in the SEEs. The achievement of operational efficiency by adopting lean practices in SEEs helps in satisfying the customer needs effectively by improving the quality, speed of delivery, and innovations and reducing costs. The lean implementation-based operational-level advantages will help the customers obtain less costly, efficient, durable, and affordable solutions. Likewise, sustainable energy consultants, such as entrepreneurs running energy advisory and consultancy firms, also develop strategies for their customers that lead to net-zero goals.

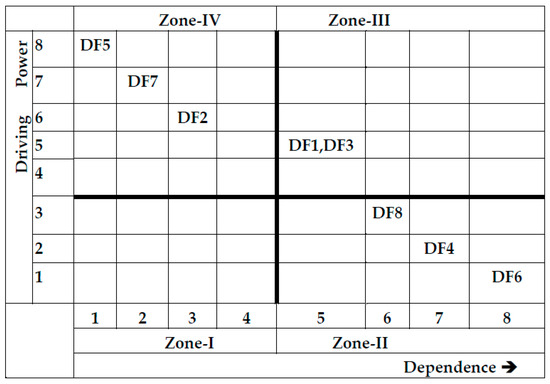

4.2. MICMAC: Categorization of Drivers of Lean Implementation in SEEs

MICMAC analysis helps in identifying the factors that belong to four zones, which show which factors are drivers and which are dependent or outcome factors. In this research, the eight factors are divided into four quadrants of lean implementation as a key driver for operational excellence in the SEEs (Table 4 and Figure 7).

Table 4.

MICMAC ranking of drivers of lean implementation in SEEs.

Figure 7.

MICMAC zone-wise categorization of drivers of lean implementation in SEEs. Note: Numbers 1–8 indicate the driving power (vertical) and dependence (horizontal) scores used to assign the drivers in the four MICMAC zones.

Zone I: Autonomous Factors (low driving power and dependence): There are no isolated factors in the drivers of lean implementation in SEEs identified in the study.

Zone II: Dependent Factors (less driving power, high dependence): This includes DF4 (Flexibility) and DF6 (Customer Focus). They are identified as the outcome or dependent factors highly influenced by other lean drivers like leadership commitment (DF5), teamwork, and collaboration (DF6), and resource optimization (DF3). This highlights that the flexibility in SEEs’ operations is influenced when there is strong leadership commitment, good collaboration and teamwork, and maximum utilization or optimization of resources.

Zone III: Linkage Factors (high driving power and dependence): DF1 (Cost Reduction), DF3 (Resource Optimization), and DF8 (Continuous Improvement) are mediating as well as important factors. They are influenced by drivers, but they also influence dependent factors identified in the system. For example, considering the case of resource optimization, they have both driving power on the cost reduction and are driven by the same factor, highlighting a two-way loop of intermediate-level factors.

Zone IV: Driving Factors (high driving power, less dependence): The most important factors in the system are evolved in this quadrant. They are the foundational/critical/independent/driving factors that influence the other factors and evolve at the base level. This includes DF5 (Leadership Commitment), DF7 (Teamwork and Collaboration), and DF2 (Time Management). These have emerged as key driving factors for lean implementation. They are less dependent on others but have a strong influence and a base for operational efficiency in SEEs. High leadership commitment facilitates teamwork and encourages collaboration, cost reduction, resource optimization, and improvement implementation in the system.

4.3. Lean Assessment—GTA

The results of the GTA, along with sensitivity analysis and the improvement suggestions, are presented in Table 5 and Table 6.

Table 5.

Lean index in different scenarios of case project organization.

Table 6.

Improvement proposals for the focus factors in the case of SEEs.

The current lean level is 0.934 (93.4%), highlighting that there is an improvement required and focus is needed for triggering driving factors such as DF4, DF6, DF8, and DF7 in the case of SEEs for improving lean performance, which is helpful for the efficiency in the process, better resource coordination, and client-satisfied delivery, providing a new face for the case of SEEs in the competitive sustainable energy sector, including both energy production-focused and energy auditing enterprises. The suggestion for improvement in these driving factors is proposed in Table 6.

5. Discussion

The study identified of interdependence between drivers of lean implementation for operational efficiency in SEEs. Leadership commitment, teamwork and collaboration, and time management are the major critical drivers, whereas customer focus is the most dependent enabler (RQ1). The classification of the drivers into four zones developed a structured hierarchy in which leadership commitment falls under the independent or driving zone, and resource optimization, cost reduction, and continuous improvement are the linkage factors that enable the dependent factors like customer focus and flexibility (RQ2). This reveals that lean implementation in SEEs requires focus on drivers that lead to the dependent drivers for achieving operational efficiency.

Sudhir et al. [10] highlighted that funding inefficiencies affect the startup to adopt lean. We have extended this funding by highlighting that leadership commitment, teamwork, and proper time management are the major foundational driving capabilities for lean adoption in SEEs. This refines the Resource-Based View (RBV) and Transformational Leadership Theory (TLT) by showing that intangible human capabilities, including leadership, are more important and essential compared with financial resources in creating operational outcomes in SEEs through lean implementation.

Tucci et al. [11] discussed that lean startups are not a “giant leap” universally, but they are operated in particular circumstances. Here, in the SEEs, the drivers’ sequence shows that there is a need for greater focus on the drivers, and then linkage drivers will lead to dependent drivers. The hierarchical influencing relations from TISM and MICMAC further extend Lean Startup Theory by Tucci et al. [11]. Lean effectiveness in SEEs follows a series, and it depends on the flow that driving factors need to prioritize, which enables linkage drivers, leading to dependent outcomes. This contextualized mechanism describes how lean implementation can be developed in sustainability enterprises with adequate prioritization in each linkage and dependent driver.

The integration of the green–lean framework in the petroleum sector by adopting sustainable value stream mapping is examined by Dibia et al. [12]. In this research, we are extending this through the identification of resource optimization as a major linkage factor linking leadership to continuous improvement, operational efficiency, and sustainability outcomes in SEEs, highlighting a clear route for lean efficiency. This further contributes to the green–lean sustainability (GLS) literature for sustainability transitions. The integration of lean implementation and sustainability is highlighted in the existing research on the framework of the GLS in the SMEs [5]. This study also found that the motivation of employees and measurement are the major challenges, and vision and support from management are success factors. The present research further builds on this by revealing that leadership commitment and teamwork are core antecedents rather than mere success factors for lean implementation in SEEs. The adoption of Lean Six Sigma in the performance of the SMEs, driven by the circular economy and green practices, can increase efficiency. Here, linkage drivers in SEEs contribute to the goals of sustainability through leadership and collaboration.

The study adds to the existing body of knowledge. The Industry 4.0 technologies, including AI, IoT, and Big Data, enhance energy efficiency at a rate of 15–25%, moderated by quality management [7]. This study focuses on the technological accelerators. Here, in this study, we have found that non-technological drivers like leadership and teamwork enhance operational efficiency and need to co-exist with technology drivers. This further adds to the digital lean assumptions by revealing that technology is a non-primary or secondary driver, which is also reliant on the capabilities of SEEs.

Other than the conceptual examination, this research provides empirical evidence on the hierarchical level of the influential relations. Resource optimization is identified by Moghadam et al. [4] in the configuration of the closed-loop supply chains for renewable energy systems, like solar and wind, which is extended by our study findings. This research focuses on the important need for integrating the circular economy practices and reverse flows because the renewable energy system has a finite lifespan. In addition to this, we have identified how resource optimization functions as a linkage enabler that connects leadership commitment and continuous improvement in the SEEs who are incorporating sustainability practices. Hence, lean drivers not only reduce waste but also make circular economy models feasible in practice.

The adaptability-increasing linkages, such as resource optimization and continuous improvement, are in accordance with dynamic capability theory (DCT) because it indicates that SEEs’ capabilities are developed from lean-focused internal drivers, along with digital technology and innovation, which will help to make them agile and responsive to changes in policy, customers’ preferences, and market uncertainties. This is through more proper management of time and coordinated entrepreneurial processes. Systems Theory is covered here through the feedback loops that emerged from the TISM results on cost reduction, enlarging resource optimization, revealing that lean outcomes result from internal processes that are linked and require structured joint interventions. The high dependence of Customer Focus (DF6) supports stakeholder theory through revealing that there is a need to satisfy the key stakeholders, like customers, by developing alignment of internal capabilities, which will promote the achievement of customer values.

Ghana’s context is highlighted by Atuahene and Sheng [2], stating that overdependence on fossil fuels and the limited integration of renewables call for fiscal incentives and more diversification. Sadik-Zada and Gatto [8] also pointed out that the energy transition includes transitions from reliance on carbon-driven roots. Here, in this study on lean implementation, we have built or refined the notion that cost reduction and flexibility are influenced by the driver antecedents and increase the competitiveness in transition-based sustainable energy markets with the operational efficiency of SEEs.

Microenterprise efficiency can be enhanced by adopting digital innovation and the integration of lean management [6,86]. This is further contributed to by extending the alignment with our finding that flexibility is a dependent factor. Blockchain can contribute to the SDGs in the Global South, emphasizing that the digital lean concept can have more sustainable outcomes [9]. Here, along with technological drivers, there should be enterprise drivers, and the internal capabilities are also most important, revealing that these can be integrated for lean implementation, and executing the lean practices can effectively integrate digital tools.

The lean assessment of the case SEEs calls for opportunities for improvement. The sensitivity analysis results of Flexibility (DF4), Customer Focus (DF6), Teamwork and Collaboration (DF7), and Continuous Improvement (DF8) identify them as the driving lean factors that require improvements through modular audit framework development, lean–sustainability review cycles, client feedback, learning loops, decentralized decision-making, collaborative cells, etc. These targeted suggestions for improvements are helpful for the SEEs to enhance operational competitiveness. This is also an additional contribution to the existing research. Flexibility (DF4), customer focus (DF6), teamwork (DF7), and continuous improvement (DF8) lead to lean-driven, sustainability-oriented energy ventures operations. These show how the interaction of capabilities for generating sustainable ventures through lean implementation in SEEs supports RBV, DCT, and Systems Theory. Hence, the study refines existing theories by explaining how lean implementation drivers require an integrated capability-building prioritization mechanism in SEEs.

Hence, this study provides a systematic, structured hierarchy as well as frameworks for decision-making and theory-building on the drivers of lean implementation in the SEEs, helpful for policymakers, practitioners, like entrepreneurs, and scholars for future research.

Apart from the contributions, the study has several limitations. The first limitation is the smaller sample size. In addition to this, the TISM-MICMAC-GTA integrated methodology may not completely consider the nonlinear relationships. And they are expert interpretation methods for theory building and decision-making. The expert-based interpretation may have subjectivity, variability, or even a chance of individual biases. Likewise, the perceptions or consensus are mainly captured in this research, which may have changed over a period of time [3,37]. A longitudinal study in the future may rectify this issue. The methodological limitations are opening the future research avenue, better integrating other methods with a larger sample size, like structural equation modelling (SEM) or regression through a quantitative survey, and validation of the model with testing hypotheses. Respondents’ perceptions may change over time, suggesting the need for longitudinal studies.

The research has contextual limitations. The geographical focus is only on the Indian context and considers the SEEs’ function in India, limiting the generalizability of the findings to other countries or entrepreneurial ecosystems. Hence, these context-bound findings also open avenues for further comparative research across different countries, including other developing economies, for exploring cross-cultural and policy dimensions for researchers to validate, contradict, or extend the identified findings in diverse cultural, regulatory, and market environments toward sustainable energy.

6. Implications of the Study

Based on the analysis, the study identifies the interrelationships as well as the driving power and dependence among drivers driving the operational efficiency through lean implementation. The study contributes to the theory, practice, and policy, and the outcome of the study is presented below.

6.1. Implications for Theory

The analysis reveals that leadership commitment (DF5), teamwork and collaboration (DF7), and time management (DF2) are the major driving factors. The intangible capabilities inside the SEEs are the key to lean implementation. These factors lead to cost reduction and customer focus. Optimization of resources highlights that the Resource-Based View in SEEs emphasizes that technology, with human and enterprise resources, is also important for the SEEs. Likewise, the linkage drivers of lean implementation with the aim of operational excellence, the factors DF1, DF3, and DF8 in MICMAC, and the feedback loops emerged in TISM (e.g., cost reduction influencing resource optimization, resource optimization influencing continuous improvement, etc.), showing the importance of adaptability. The SEEs’ resource optimization and cost reduction promote the development of dynamic capabilities, which help the SEEs to respond and adapt to the changes in policy, customer preferences, etc. The dynamic capability theory (DCT) is coming into the picture here.