Multisource Remote Sensing and Machine Learning for Spatio-Temporal Drought Assessment in Northeast Syria

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

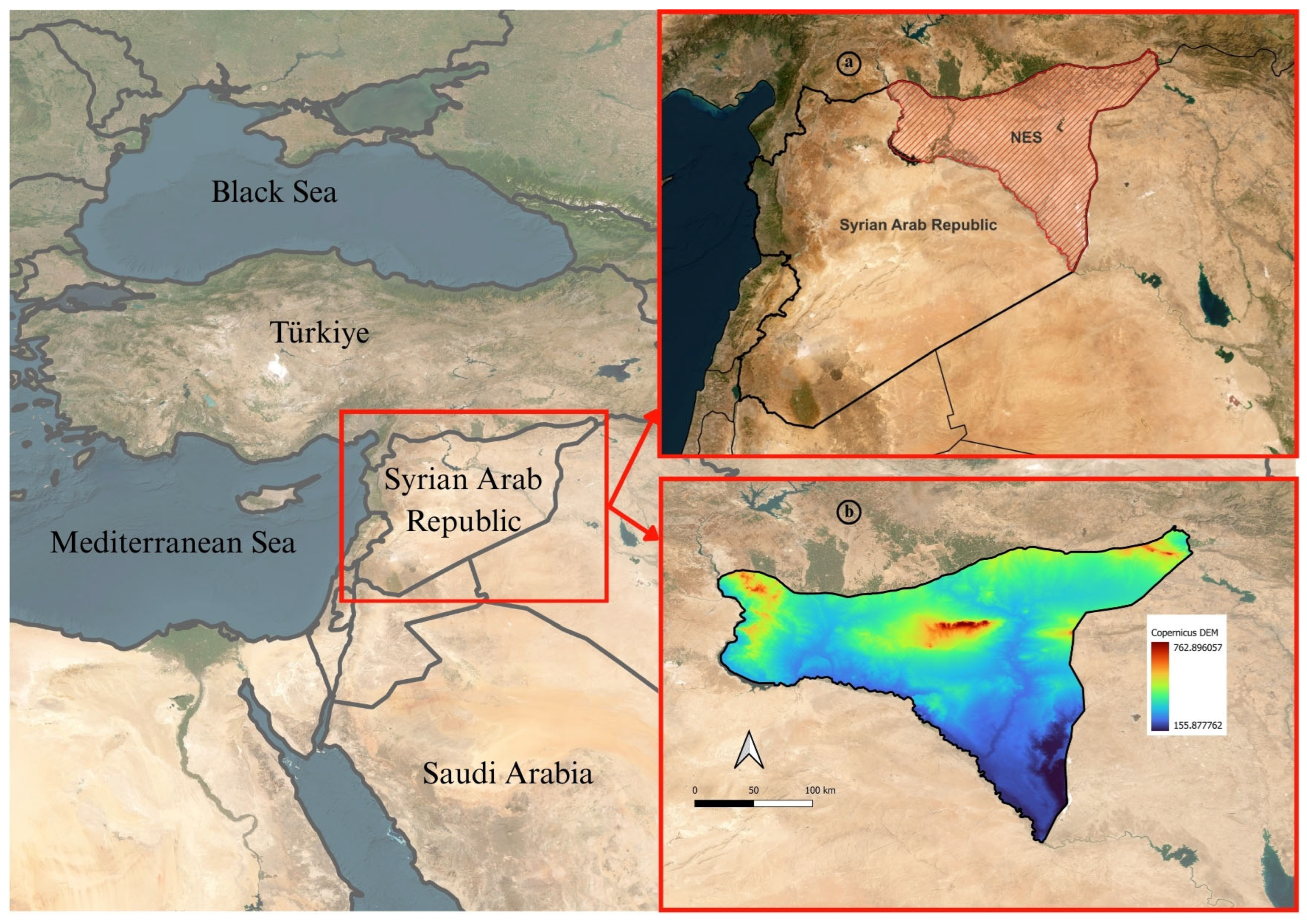

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Dataset

2.2.1. Meteorological Data

2.2.2. Land Surface Temperature

2.2.3. Vegetation Indices

2.2.4. Soil Moisture

2.2.5. Soil Salinity

2.2.6. Soil Properties

2.2.7. Data Aggregation

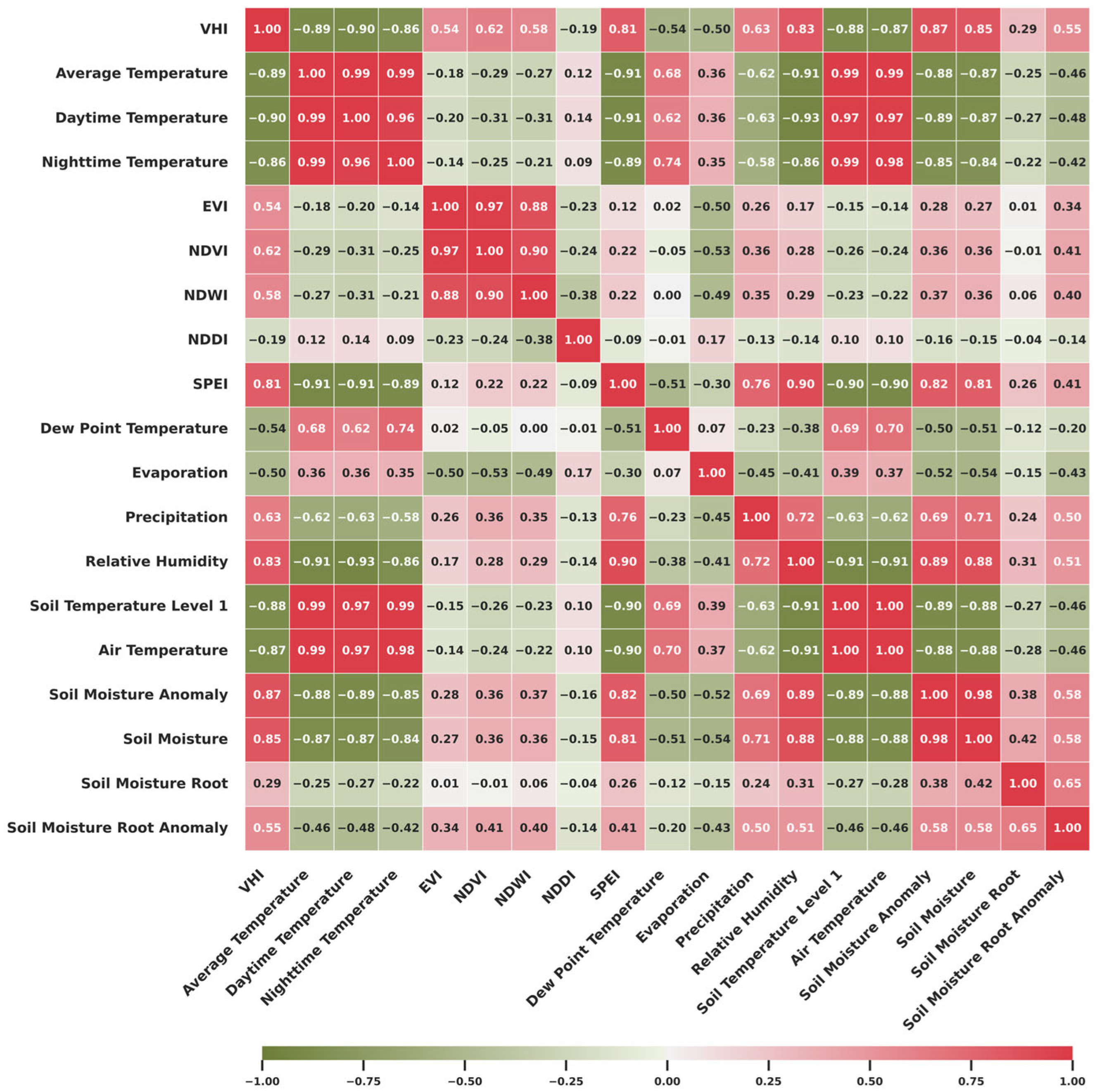

2.2.8. Exploratory Data

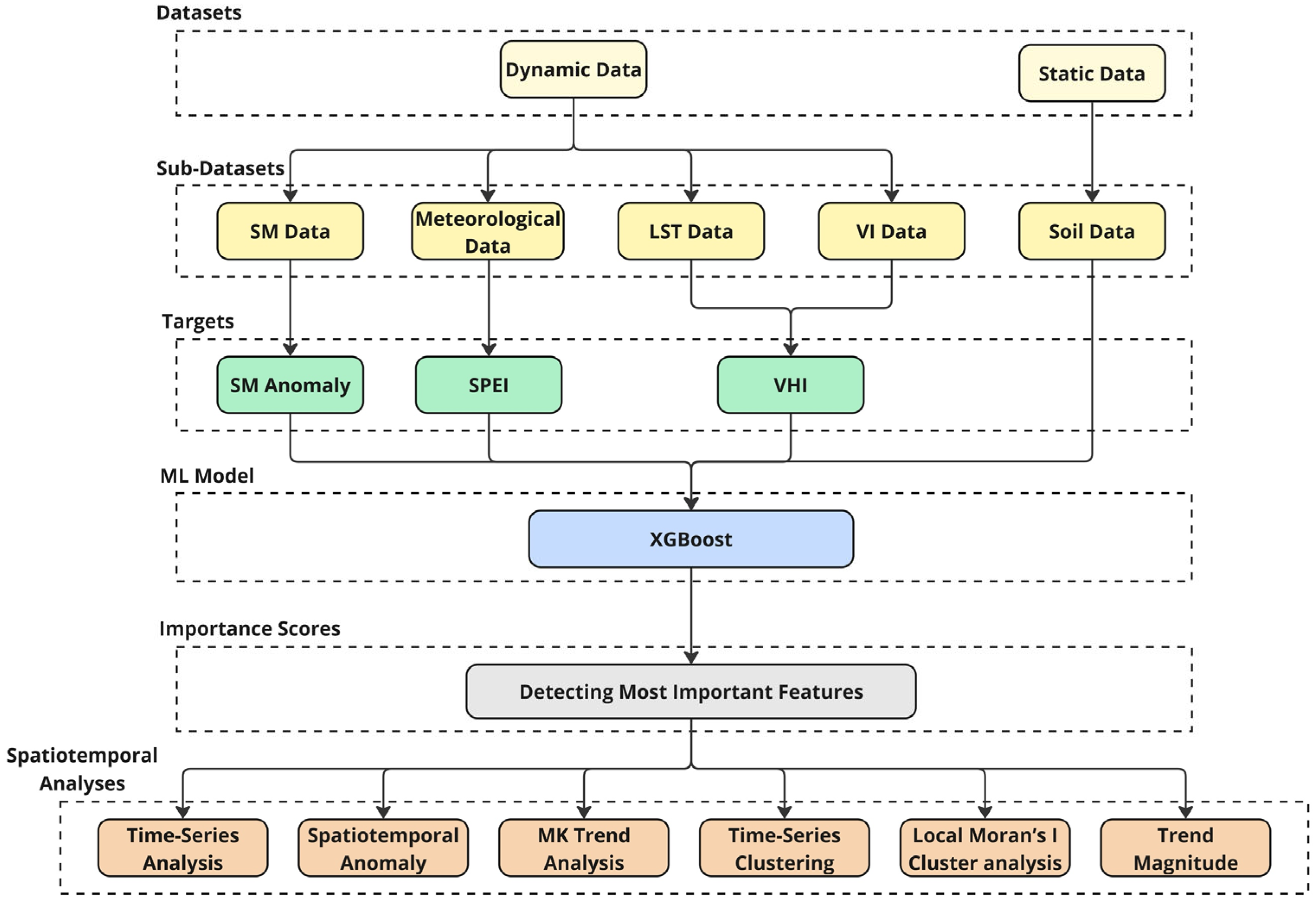

2.3. Methodology

2.3.1. Target Preparation and ML Model Parameters

2.3.2. XGBoost (eXtreme Gradient Boosting) and Bayesian Optimization

2.3.3. Evaluation Metrics

2.3.4. SHAP (SHapley Additive Explanation)

2.3.5. Feature Importance Assessment and Spatiotemporal Analyses

3. Results

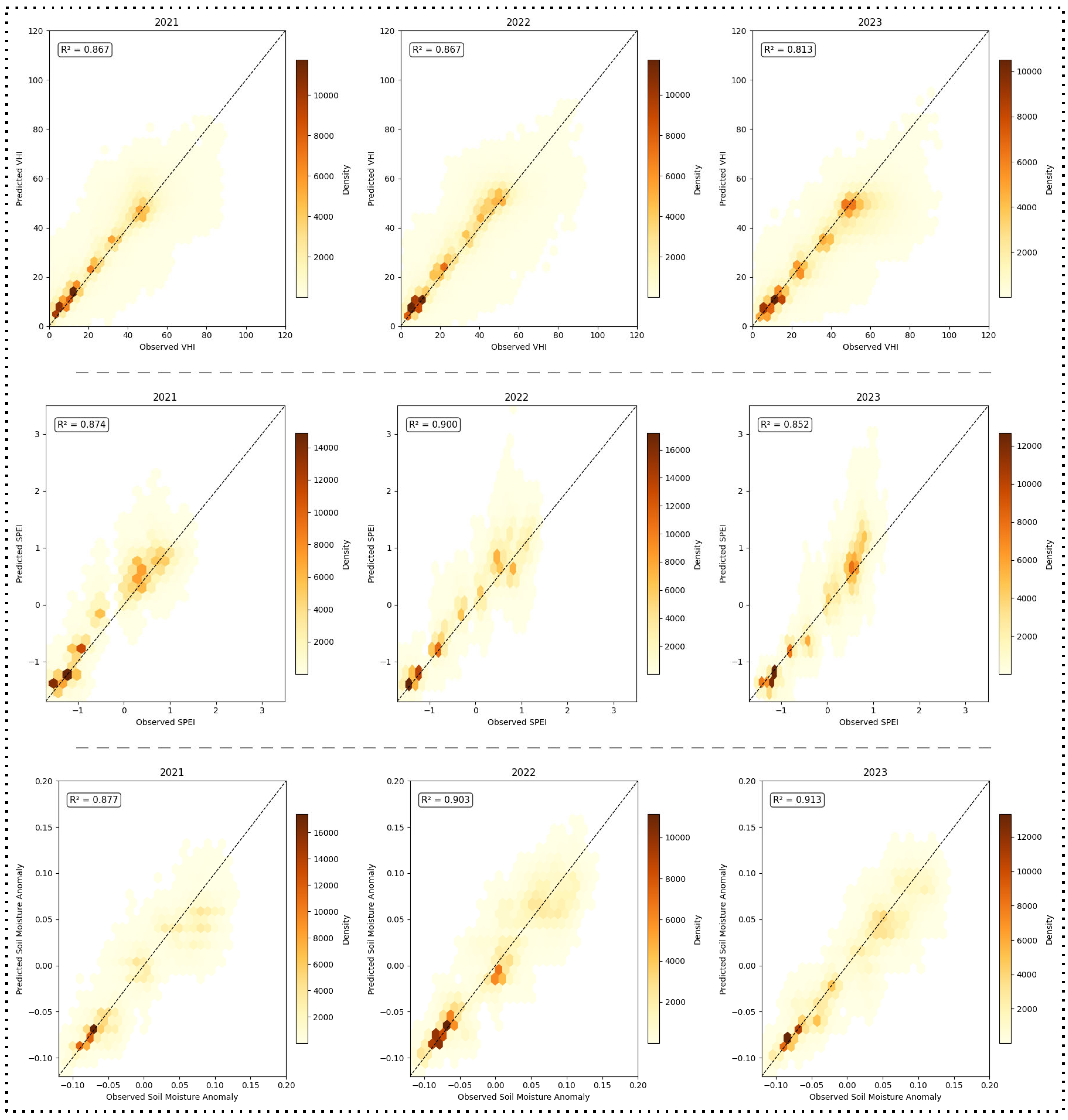

3.1. Regression Model Performance

3.2. Identification of Significant Features

3.3. Temporal Trends and Spatial Patterns of the Most Important Features

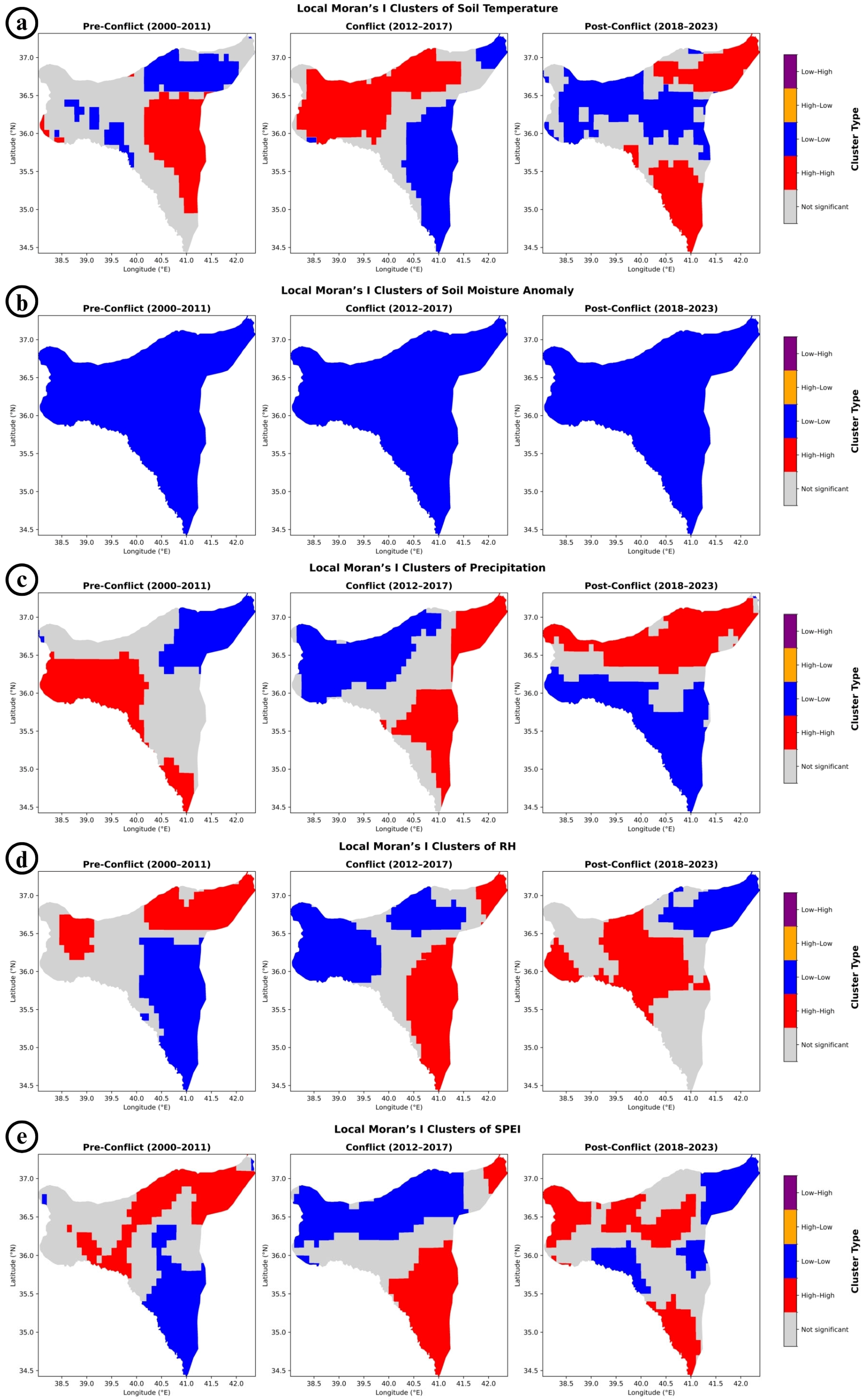

3.4. Local Moran’s I Spatial Cluster Analysis

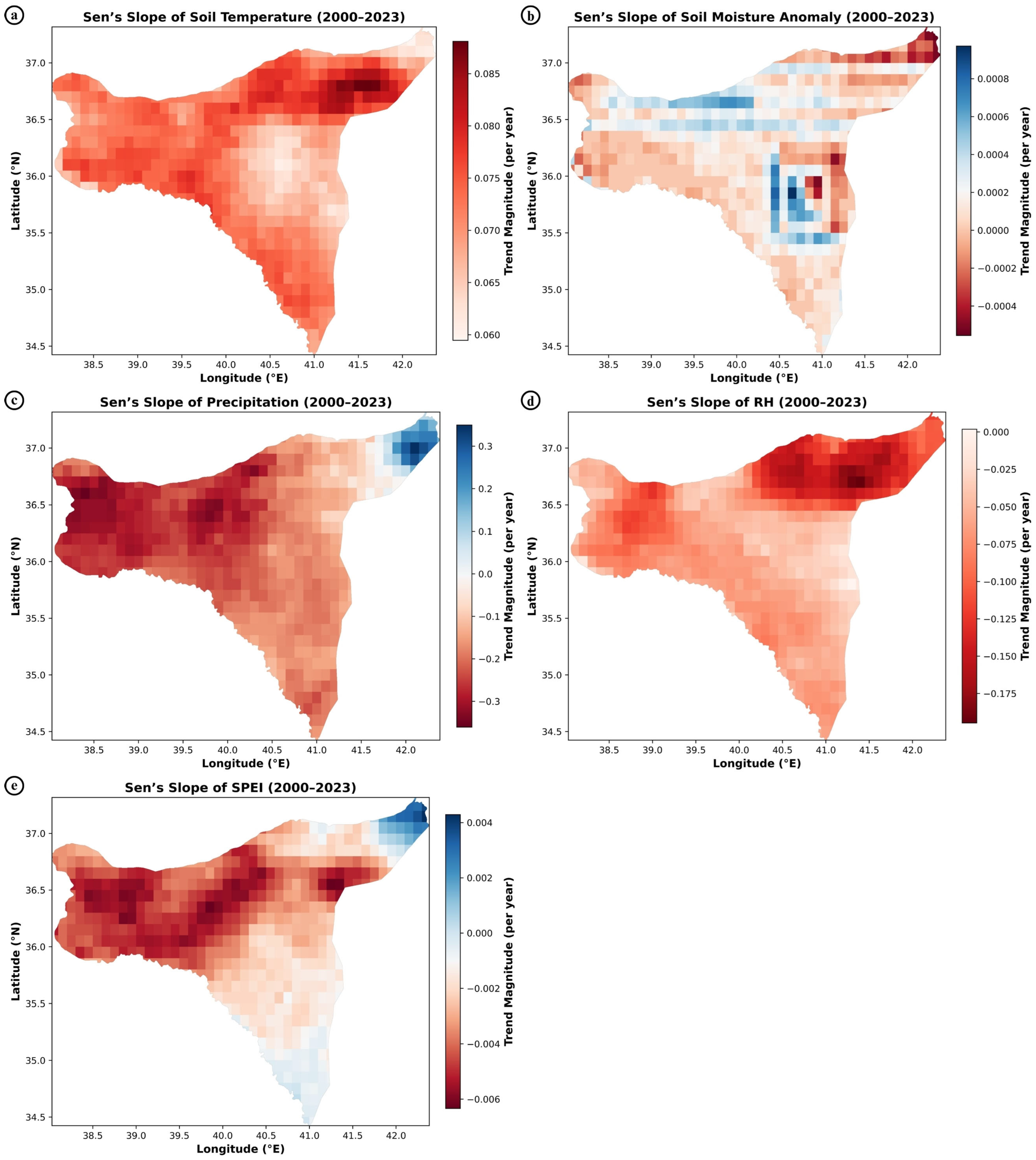

3.5. Spatial Intensification of Warming and Drying Trends in NES

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NES | Northeast Syria |

| ERA5-Land | ECMWF ReAnalysis version 5—Land component |

| MODIS | Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer |

| FLDAS | Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET) Land Data Assimilation System |

| ISRIC | International Soil Reference and Information Centre |

| SAR | Synthetic Aperture Radar |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| XGBoost | eXtreme Gradient Boosting |

| SHAP | SHapley Additive exPlanations |

| VHI | Vegetation Health Index |

| SPEI | Standardized Precipitation-Evapotranspiration Index |

| RH | Relative Humidity |

| NDVI | Normalized Difference Vegetation Index |

| VCI | Vegetation Condition Index |

| NDWI | Normalized Difference Water Index |

| ECMWF | European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts |

| LST | Land Surface Temperature |

| EVI | Enhanced Vegetation Index |

| NDDI | Normalized Difference Drought Index |

| VI | Vegetation Indices |

| PET | Evapotranspiration |

| SPI | Standardized Precipitation Index |

| FAO | Food and Agriculture Organization |

| TCI | Temperature Condition Index |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| R2 | Coefficient of Determination |

| MK | Mann–Kendall Test |

| MENA | Middle East and North Africa |

References

- Kenawy, A.E.; Al-Awadhi, T.; Abdullah, M.; Ostermann, F.O.; Abulibdeh, A. A Multidecadal Assessment of Drought Intensification in the Middle East and North Africa: The Role of Global Warming and Rainfall Deficit. Earth Syst. Environ. 2025, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebrechorkos, S.H.; Sheffield, J.; Vicente-Serrano, S.M.; Funk, C.; Miralles, D.G.; Peng, J.; Dyer, E.; Talib, J.; Beck, H.E.; Singer, M.B.; et al. Warming Accelerates Global Drought Severity. Nature 2025, 642, 628–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, D.; Fowler, H.J.; Kilsby, C.G.; Neal, R. A New Precipitation and Drought Climatology Based on Weather Patterns. Int. J. Climatol. 2018, 38, 630–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinoni, J.; Barbosa, P.; De Jager, A.; McCormick, N.; Naumann, G.; Vogt, J.V.; Magni, D.; Masante, D.; Mazzeschi, M. A New Global Database of Meteorological Drought Events from 1951 to 2016. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2019, 22, 100593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maity, S.S.; Maity, R. Changing Pattern of Intensity–Duration–Frequency Relationship of Precipitation Due to Climate Change. Water Resour. Manag. 2022, 36, 5371–5399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, A. Hydroclimatic Trends during 1950–2018 over Global Land. Clim. Dyn. 2021, 56, 4027–4049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakke, S.J.; Ionita, M.; Tallaksen, L.M. Recent European Drying and Its Link to Prevailing Large-Scale Atmospheric Patterns. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 21921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thom, D.; Jentsch, A.; Seidl, R. Disturbances and Ecosystem Services. In Disturbance Ecology; Wohlgemuth, T., Jentsch, A., Seidl, R., Eds.; Landscape Series; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 32, pp. 413–434. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Z.; Wu, W.; Li, Y.; Huang, C.; Zhang, X.; Peñuelas, J.; Zhang, Y.; Gentine, P.; Li, Z.; Wang, X.; et al. Increasing Meteorological Drought under Climate Change Reduces Terrestrial Ecosystem Productivity and Carbon Storage. One Earth 2023, 6, 1326–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seleiman, M.F.; Al-Suhaibani, N.; Ali, N.; Akmal, M.; Alotaibi, M.; Refay, Y.; Dindaroglu, T.; Abdul-Wajid, H.H.; Battaglia, M.L. Drought Stress Impacts on Plants and Different Approaches to Alleviate Its Adverse Effects. Plants 2021, 10, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orimoloye, I.R.; Belle, J.A.; Orimoloye, Y.M.; Olusola, A.O.; Ololade, O.O. Drought: A Common Environmental Disaster. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karume, K.; Mondo, J.M.; Kiyala, J.C.K. Drought, the War in Europe and Its Impacts on Food Insecurity in Sub-Saharan Africa, East Africa. In Climate Change and Socio-Political Violence in Sub-Saharan Africa in the Anthropocene; Kiyala, J.C.K., Chivasa, N., Eds.; The Anthropocene: Politik—Economics—Society—Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 37, pp. 91–111. [Google Scholar]

- Abdullah, M.; Abulibdeh, A.; Ghanimeh, S.; Hamdi, H.; Al-Awah, H.; Al-Awadhi, T.; Mohan, M.; Al-Ali, Z.; Sukkar, A.; El Kenawy, A.M. Characterizing the Dynamics of Climate and Native Desert Plants in Qatar. J. Arid. Environ. 2024, 225, 105274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente-Serrano, S.M.; Beguería, S.; López-Moreno, J.I. A Multiscalar Drought Index Sensitive to Global Warming: The Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index. J. Clim. 2010, 23, 1696–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Moriasi, D.N.; Danandeh Mehr, A.; Mirchi, A. Sensitivity of Standardized Precipitation and Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI) to the Choice of SPEI Probability Distribution and Evapotranspiration Method. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2024, 53, 101761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.; Li, J.; Zhang, T.; Kang, A. The Use of Combined Soil Moisture Data to Characterize Agricultural Drought Conditions and the Relationship among Different Drought Types in China. Agric. Water Manag. 2021, 243, 106479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Fernández, J.; González-Zamora, A.; Sánchez, N.; Gumuzzio, A.; Herrero-Jiménez, C.M. Satellite Soil Moisture for Agricultural Drought Monitoring: Assessment of the SMOS Derived Soil Water Deficit Index. Remote Sens. Environ. 2016, 177, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannico, V.; Garofalo, S.P.; Brillante, L.; Sciusco, P.; Elia, M.; Lopriore, G.; Camposeo, S.; Lafortezza, R.; Sanesi, G.; Vivaldi, G.A. Temporal Vine Water Status Modeling Through Machine Learning Ensemble Technique and Sentinel-2 Multispectral Images Under Semi-Arid Conditions. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 4784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, H.; Quinn, N.; Horswell, M. Remote Sensing for Drought Monitoring & Impact Assessment: Progress, Past Challenges and Future Opportunities. Remote Sens. Environ. 2019, 232, 111291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abulibdeh, A.; Pirasteh, S.; Mafi-Gholami, D.; Kucukvar, M.; Onat, N.C.; Zaidan, E. Unveiling the Nexus Between Land Use, Land Surface Temperature, and Carbon Footprint: A Multi-Scale Analysis of Building Energy Consumption in Arid Urban Areas. Earth Syst. Environ. 2025, 9, 2563–2601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Jia, H.; Wang, L. Remote Sensing Monitoring of Drought in Southwest China Using Random Forest and EXtreme Gradient Boosting Methods. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 4840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemzadeh Ghalhari, M.; Vafakhah, M.; Damavandi, A.A. Agricultural Drought Assessment Using Vegetation Indices Derived from MODIS Time Series in Tehran Province. Arab. J. Geosci. 2022, 15, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cammalleri, C.; Vogt, J. On the Role of Land Surface Temperature as Proxy of Soil Moisture Status for Drought Monitoring in Europe. Remote Sens. 2015, 7, 16849–16864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Q.; Xu, J.; Liao, L.; Yu, Y.; Liu, W.; Zhou, J.; Ding, Y. Indicators for Evaluating Trends of Air Humidification in Arid Regions under Circumstance of Climate Change: Relative Humidity (RH) vs. Actual Water Vapour Pressure (Ea). Ecol. Indic. 2021, 121, 107043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, K.; Gao, J.; Liu, Z. Precipitation Drives the NDVI Distribution on the Tibetan Plateau While High Warming Rates May Intensify Its Ecological Droughts. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente-Serrano, S.M.; Tramblay, Y.; Reig, F.; González-Hidalgo, J.C.; Beguería, S.; Brunetti, M.; Kalin, K.C.; Patalen, L.; Kržič, A.; Lionello, P.; et al. High Temporal Variability Not Trend Dominates Mediterranean Precipitation. Nature 2025, 639, 658–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandgude, N.; Singh, T.P.; Nandgude, S.; Tiwari, M. Drought Prediction: A Comprehensive Review of Different Drought Prediction Models and Adopted Technologies. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyarzabal, R.S.; Santos, L.B.L.; Cunningham, C.; Broedel, E.; de Lima, G.R.T.; Cunha-Zeri, G.; Peixoto, J.S.; Anochi, J.A.; Garcia, K.; Costa, L.C.O.; et al. Forecasting Drought Using Machine Learning: A Systematic Literature Review. Nat. Hazards 2025, 121, 9823–9851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isik, M.S.; Ozturk, O.; Celik, M.F. Kolmogorov–Arnold Networks for Interpretable Crop Yield Prediction Across the U.S. Corn Belt. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 2500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Başakın, E.E.; Stoy, P.C.; Demirel, M.C.; Ozdogan, M.; Otkin, J.A. Combined Drought Index Using High-Resolution Hydrological Models and Explainable Artificial Intelligence Techniques in Türkiye. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iban, M.C.; Aksu, O. SHAP-Driven Explainable Artificial Intelligence Framework for Wildfire Susceptibility Mapping Using MODIS Active Fire Pixels: An In-Depth Interpretation of Contributing Factors in Izmir, Türkiye. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 2842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, S.; Zhang, X.; Saraswat, D.; Sahany, S.; Mishra, S.K.; Niyogi, D. Flash Drought: Review of Concept, Prediction and the Potential for Machine Learning, Deep Learning Methods. Earths Future 2022, 10, e2022EF002723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abulibdeh, A. Analysis of Mode Choice Affects from the Introduction of Doha Metro Using Machine Learning and Statistical Analysis. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2023, 20, 100852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.N.; Shao, Z.; Javed, A.; Ahmad, I.; Islam, F.; Skilodimou, H.D.; Bathrellos, G.D. Optical–SAR Data Fusion Based on Simple Layer Stacking and the XGBoost Algorithm to Extract Urban Impervious Surfaces in Global Alpha Cities. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Bai, Y.; Zhang, S.; Yang, S.; Henchiri, M.; Seka, A.M.; Nanzad, L. Drought Monitoring and Performance Evaluation Based on Machine Learning Fusion of Multi-Source Remote Sensing Drought Factors. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 6398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dikshit, A.; Pradhan, B.; Huete, A. An Improved SPEI Drought Forecasting Approach Using the Long Short-Term Memory Neural Network. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 283, 111979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, R.; Huang, A.; Li, B.; Guo, J. Construction of a Drought Monitoring Model Using Deep Learning Based on Multi-Source Remote Sensing Data. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2019, 79, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hole, F. Drivers of Unsustainable Land Use in the Semi-Arid Khabur River Basin, Syria. Geogr. Res. 2009, 47, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homsi, R.; Shahid, S.; Iqbal, Z.; Ali, A.M.; Ziarh, G.F. Historical Trends in Crop Water Demand over Semiarid Region of Syria. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2021, 146, 555–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Special Report: 2021 FAO Crop and Food Supply Assessment Mission to the Syrian Arab Republic—December 2021; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2021; ISBN 978-92-5-135514-5. [Google Scholar]

- Humanitarian Data Exchange (HDX). Northern Syria Population Tracking. Available online: https://data.humdata.org/dataset/population-displacement-and-return-movements-in-northern-syria (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Sukkar, A.; Abulibdeh, A.; Essoussi, S.; Seker, D.Z. Investigating the Impacts of Climate Variations and Armed Conflict on Drought and Vegetation Cover in Northeast Syria (2000–2023). J. Arid. Environ. 2024, 225, 105278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre, B.A.; Hsieh, B.; Watson, S.J.; Wright, A.J. The Experimental Manipulation of Atmospheric Drought: Teasing out the Role of Microclimate in Biodiversity Experiments. J. Ecol. 2021, 109, 1986–1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alduchov, O.A.; Eskridge, R.E. Improved Magnus Form Approximation of Saturation Vapor Pressure. J. Appl. Meteorol. 1996, 35, 601–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Z.; Hook, S.; Hulley, G. MODIS/Terra Land Surface Temperature/Emissivity Daily L3 Global 1km SIN Grid V061 2021; NASA: Washington, DC, USA, 2021.

- Didan, K. MODIS/Terra Vegetation Indices 16-Day L3 Global 250 m SIN Grid V061 2021; NASA Land Processes Distributed Active Archive Center: Sioux Falls, SD, USA, 2021.

- McNally, A. FLDAS Noah Land Surface Model L4 Global Monthly 0.1 × 0.1 Degree (MERRA-2 and CHIRPS) 2018; Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET) Land Data Assimilation System (FLDAS): Greenbelt, MD, USA, 2018.

- Ivushkin, K.; Bartholomeus, H.; Bregt, A.K.; Pulatov, A.; Kempen, B.; de Sousa, L. Global Mapping of Soil Salinity Change. Remote Sens. Environ. 2019, 231, 111260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poggio, L.; de Sousa, L.M.; Batjes, N.H.; Heuvelink, G.B.M.; Kempen, B.; Ribeiro, E.; Rossiter, D. SoilGrids 2.0: Producing Soil Information for the Globe with Quantified Spatial Uncertainty. SOIL 2021, 7, 217–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Meteorological Organization (WMO); Global Water Partnership (GWP). Handbook of Drought Indicators and Indices; Svoboda, M., Fuchs, B.A., Eds.; Integrated Drought Management Tools and Guidelines Series 2; WMO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016; ISBN 978-92-63-11173-9. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, H.; Hu, H.; Wang, Z.; Lai, C. Temporal Variability of Drought in Nine Agricultural Regions of China and the Influence of Atmospheric Circulation. Atmosphere 2020, 11, 990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente-Serrano, S.M.; Gouveia, C.; Camarero, J.J.; Beguería, S.; Trigo, R.; López-Moreno, J.I.; Azorín-Molina, C.; Pasho, E.; Lorenzo-Lacruz, J.; Revuelto, J.; et al. Response of Vegetation to Drought Time-Scales across Global Land Biomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, D.; Zheng, J.; Shi, J.; Liao, F.; Ma, X.; Wang, W.; Chen, X.; Zhang, M. A Comparative Study of Potential Evapotranspiration Estimation by Eight Methods with FAO Penman–Monteith Method in Southwestern China. Water 2017, 9, 734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, B.Y.; Cannon, A.J.; Bonsal, B.R. Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI) for Canada: Assessment of Probability Distributions. Can. Water Resour. J. Rev. Can. Des. Ressour. Hydr. 2023, 48, 283–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Zhang, R.; Qu, Y.; Bento, V.A.; Zhou, T.; Lin, Y.; Wu, X.; Qi, J.; Shui, W.; Wang, Q. Improving the Drought Monitoring Capability of VHI at the Global Scale via Ensemble Indices for Various Vegetation Types from 2001 to 2018. Weather Clim. Extrem. 2022, 35, 100412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hang, Q.; Guo, H.; Meng, X.; Wang, W.; Cao, Y.; Liu, R.; De Maeyer, P.; Wang, Y. Optimizing the Vegetation Health Index for Agricultural Drought Monitoring: Evaluation and Application in the Yellow River Basin. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 4507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Feng, H.; He, H.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, Y. Evaluation of Soil Moisture Climatology and Anomaly Components Derived From ERA5-Land and GLDAS-2.1 in China. Water Resour. Manag. 2021, 35, 629–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; ACM: New York, NY, USA; pp. 785–794.

- Akiba, T.; Sano, S.; Yanase, T.; Ohta, T.; Koyama, M. Optuna: A Next-Generation Hyperparameter Optimization Framework. In Proceedings of the 25th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, Anchorage, AK, USA, 4–8 August 2019; ACM: New York, NY, USA; pp. 2623–2631.

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.-I. A Unified Approach to Interpreting Model Predictions. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1705.07874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, S.; Pilon, P. A Comparison of the Power of the t Test, Mann-Kendall and Bootstrap Tests for Trend Detection/Une Comparaison de La Puissance Des Tests t de Student, de Mann-Kendall et Du Bootstrap Pour La Détection de Tendance. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2004, 49, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamed, K.H. Trend Detection in Hydrologic Data: The Mann–Kendall Trend Test under the Scaling Hypothesis. J. Hydrol. 2008, 349, 350–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anselin, L.; Syabri, I.; Kho, Y. GeoDa: An Introduction to Spatial Data Analysis. Geogr. Anal. 2006, 38, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbelaitz, O.; Gurrutxaga, I.; Muguerza, J.; Pérez, J.M.; Perona, I. An Extensive Comparative Study of Cluster Validity Indices. Pattern Recognit. 2013, 46, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halder, K.; Srivastava, A.K.; Ghosh, A.; Nabik, R.; Pan, S.; Chatterjee, U.; Bisai, D.; Pal, S.C.; Zeng, W.; Ewert, F.; et al. Application of Bagging and Boosting Ensemble Machine Learning Techniques for Groundwater Potential Mapping in a Drought-Prone Agriculture Region of Eastern India. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2024, 36, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xie, D.; Tian, W.; Zhao, H.; Geng, S.; Lu, H.; Ma, G.; Huang, J.; Choy Lim Kam Sian, K.T. Construction of an Integrated Drought Monitoring Model Based on Deep Learning Algorithms. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ontel, I.; Irimescu, A.; Boldeanu, G.; Mihailescu, D.; Angearu, C.-V.; Nertan, A.; Craciunescu, V.; Negreanu, S. Assessment of Soil Moisture Anomaly Sensitivity to Detect Drought Spatio-Temporal Variability in Romania. Sensors 2021, 21, 8371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luong, V.V.; Bui, D.H. Evaluation of Models and Drought-Wetness Factors Contributing to Predicting the Vegetation Health Index in Dak Nong Province, Vietnam. Environ. Res. Commun. 2024, 6, 045005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathbout, S.; Lopez-Bustins, J.A.; Martin-Vide, J.; Bech, J.; Rodrigo, F.S. Spatial and Temporal Analysis of Drought Variability at Several Time Scales in Syria during 1961–2012. Atmos. Res. 2018, 200, 153–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, C.P.; Mohtadi, S.; Cane, M.A.; Seager, R.; Kushnir, Y. Climate Change in the Fertile Crescent and Implications of the Recent Syrian Drought. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 3241–3246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, S.; Alsafadi, K.; Al-Awadhi, T.; Sherief, Y.; Harsanyie, E.; El Kenawy, A.M. Space and Time Variability of Meteorological Drought in Syria. Acta Geophys. 2020, 68, 1877–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydın-Kandemir, F.; Yıldız, D. Water Conflicts and the Spatiotemporal Changes in Land Use, Irrigation, and Drought in Northeast Syria with Future Estimations. Int. J. Water Manag. Dipl. 2022, 1, 5–36. [Google Scholar]

- Selby, J.; Dahi, O.S.; Fröhlich, C.; Hulme, M. Climate Change and the Syrian Civil War Revisited. Polit. Geogr. 2017, 60, 232–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Guo, R.; Yan, Q.; Chen, X.; Zhou, S.; Liang, C.; Wei, X.; Dolman, H. Land Management Contributes Significantly to Observed Vegetation Browning in Syria during 2001–2018. Biogeosciences 2022, 19, 1515–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eklund, L.; Theisen, O.M.; Baumann, M.; Forø Tollefsen, A.; Kuemmerle, T.; Østergaard Nielsen, J. Societal Drought Vulnerability and the Syrian Climate-Conflict Nexus Are Better Explained by Agriculture than Meteorology. Commun. Earth Environ. 2022, 3, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Châtel, F. The Role of Drought and Climate Change in the Syrian Uprising: Untangling the Triggers of the Revolution. Middle East. Stud. 2014, 50, 521–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ülker, D.; Ergüven, O.; Gazioğlu, C. Socio-Economic Impacts in a Changing Climate: Case Study Syria. Int. J. Environ. Geoinformatics 2018, 5, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathbout, S.; Martin-Vide, J.; Bustins, J.A.L. Drought Characteristics Projections Based on CMIP6 Climate Change Scenarios in Syria. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2023, 50, 101581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathbout, S.; Boustras, G.; Papazoglou, P.; Martin Vide, J.; Raai, F. Integrating Climate Indices and Land Use Practices for Comprehensive Drought Monitoring in Syria: Impacts and Implications. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2025, 26, 100631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Feature | Unit | Min | Max | Mean | Std |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VHI | - | 0.00 | 95.83 | 32.66 | 20.01 |

| Average Temperature | °C | −0.27 | 45.50 | 23.40 | 11.47 |

| Daytime Temperature | °C | −0.25 | 60.12 | 33.48 | 13.78 |

| Nighttime Temperature | °C | −7.45 | 32.33 | 13.32 | 9.40 |

| EVI | - | −0.08 | 0.80 | 0.13 | 0.09 |

| NDVI | - | −0.16 | 0.90 | 0.19 | 0.13 |

| NDWI | - | −0.39 | 0.92 | 0.08 | 0.13 |

| NDDI | - | −33.00 | 33.00 | 0.92 | 1.66 |

| SPEI | - | −3.50 | 3.83 | −0.06 | 0.98 |

| Dew Point Temperature | °C | −6.73 | 18.39 | 5.73 | 3.58 |

| Evaporation | mm | −7.64 | -0.02 | −0.76 | 0.69 |

| Precipitation | mm | 0.00 | 10.62 | 0.73 | 0.97 |

| Relative Humidity | % | 13.19 | 86.51 | 44.03 | 19.19 |

| Soil Temperature Level 1 | °C | 1.16 | 40.20 | 21.64 | 10.49 |

| Air Temperature | °C | 0.84 | 37.16 | 20.07 | 9.58 |

| Soil Moisture Anomaly | - | −0.12 | 0.17 | 0.00 | 0.07 |

| Soil Moisture Root Anomaly | - | −0.13 | 0.16 | 0.00 | 0.03 |

| Soil Moisture | m3 m−3 | 0.14 | 0.42 | 0.22 | 0.07 |

| Soil Moisture Root | m3 m−3 | 0.14 | 0.42 | 0.30 | 0.05 |

| Bulk Density | cg cm−3 | 119.00 | 154.00 | 145.08 | 3.45 |

| Cation Exchange Capacity (at pH 7) | Mmol (c)/kg | 98.00 | 413.00 | 254.83 | 63.64 |

| Clay Content | g kg−1 | 165.00 | 576.00 | 346.90 | 75.58 |

| Coarse Fragments (Volumetric) | cm3 dm−3 | 8.00 | 265.00 | 86.11 | 35.60 |

| Nitrogen Content | cg kg−1 | 61.00 | 494.00 | 175.55 | 54.51 |

| Organic Carbon Density | hg m−3 | 111.00 | 411.00 | 201.29 | 50.75 |

| Sand Content | g kg−1 | 35.00 | 478.00 | 207.88 | 49.71 |

| Silt Content | g kg−1 | 309.00 | 645.00 | 445.22 | 42.20 |

| Soil Organic Carbon Content | dg kg−1 | 47.00 | 1111.00 | 128.34 | 57.50 |

| Soil Organic Carbon Stock | t ha−1 | 14.00 | 51.00 | 27.39 | 6.40 |

| Soil pH in H2O | pH | 6.80 | 8.40 | 7.70 | 2.01 |

| Soil Salinity | dS m−1 | 0.00 | 4.00 | 0.45 | 0.57 |

| Target | Year | R2 | RMSE | MAE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VHI | 2021 | 0.87 | 6.42 | 4.34 |

| 2022 | 0.88 | 5.49 | 3.69 | |

| 2023 | 0.86 | 6.03 | 4.10 | |

| SPEI | 2021 | 0.87 | 0.31 | 0.23 |

| 2022 | 0.90 | 0.29 | 0.21 | |

| 2023 | 0.88 | 0.31 | 0.23 | |

| Soil Moisture Anomaly | 2021 | 0.87 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| 2022 | 0.90 | 0.02 | 0.01 | |

| 2023 | 0.88 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sukkar, A.; Ozturk, O.; Abulibdeh, A.; Seker, D.Z. Multisource Remote Sensing and Machine Learning for Spatio-Temporal Drought Assessment in Northeast Syria. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10933. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410933

Sukkar A, Ozturk O, Abulibdeh A, Seker DZ. Multisource Remote Sensing and Machine Learning for Spatio-Temporal Drought Assessment in Northeast Syria. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):10933. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410933

Chicago/Turabian StyleSukkar, Abdullah, Ozan Ozturk, Ammar Abulibdeh, and Dursun Zafer Seker. 2025. "Multisource Remote Sensing and Machine Learning for Spatio-Temporal Drought Assessment in Northeast Syria" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 10933. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410933

APA StyleSukkar, A., Ozturk, O., Abulibdeh, A., & Seker, D. Z. (2025). Multisource Remote Sensing and Machine Learning for Spatio-Temporal Drought Assessment in Northeast Syria. Sustainability, 17(24), 10933. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410933