Abstract

The rapid global shift toward transportation electrification has positioned e-mobility as a key part of low-carbon transition strategies. Saudi Arabia, as a major energy producer undergoing economic diversification under Vision 2030, has recently increased its policy efforts for electric mobility. This study performs a qualitative document analysis of 52 national policies, strategies, and institutional publications issued between 2010 and 2025, creating a longitudinal dataset of 1240 coded references. Using a PRISMA-aligned screening process and NVivo-based thematic coding, the analysis highlights main policy trends, institutional priorities, and implementation challenges influencing the Kingdom’s e-mobility transition. Results show a clear shift from early technology-neutral sustainability rhetoric to a more explicit policy framework focusing on industrial localization, charging infrastructure growth, renewable energy integration, and regulatory development after 2020. Despite these advances, gaps remain in governance coordination, market readiness, charging accessibility, and user adoption incentives. The paper provides a systematically mapped view of Saudi Arabia’s e-mobility policy landscape and places it within global transition trends. The findings offer practical insights for policymakers aiming to strengthen implementation, accelerate adoption, and align transport electrification with national decarbonization goals.

1. Introduction

Transportation systems worldwide are undergoing rapid transformation as countries seek to reduce reliance on fossil fuels and accelerate the transition toward clean energy sources [1,2,3]. The transportation sector currently contributes nearly one-quarter of global CO2 emissions [4], making it a key focus for climate change mitigation policies. Among the available strategies, electrification has become one of the most effective approaches for reducing emissions, improving air quality, and diversifying national energy sources [5,6]. Global EV sales increased from fewer than one million units in 2017 to over 14 million in 2023, with electric vehicles now accounting for approximately 18% of global light-duty vehicle sales [7]. Countries such as Norway, China, the United States, Germany, and the United Kingdom are leading this transition through coordinated regulatory frameworks, consumer incentives, local manufacturing initiatives, and expanded charging infrastructure deployment.

This global transition reflects not only environmental needs but also evolving industrial and geopolitical interests. The move toward e-mobility is increasingly connected to national priorities related to economic diversification, energy security, and technological competitiveness [8]. As countries invest in battery production, electric drivetrain technologies, and renewable energy integration, the e-mobility sector has become a major source of innovation and economic growth [9]. At the same time, the rapid growth in EV adoption brings attention to challenges related to grid capacity, material supply chains, charging access, and social equity [10,11]. Addressing these issues requires long-term strategies, evidence-based policy design, and sustained institutional coordination.

Globally, transportation has become a major focus of climate action, with decarbonization viewed as a fundamental component of climate-change mitigation efforts. Scholars argue that sustainable transportation requires a combination of technological, behavioral, and infrastructure-based interventions, including shifts toward public transportation, active mobility, and low-carbon vehicle technologies [12,13]. Among these innovations, EVs have emerged as a cornerstone of sustainable transportation transitions, providing both environmental benefits and opportunities for industrial and technological development [14].

In the Saudi Arabian context, transportation has traditionally been influenced by the availability of cheap, heavily subsidized fuel and decades of road-centric planning. This has led scholars to describe the Kingdom’s mobility system as an oil-rentier mobility paradigm [15], characterized by extensive automobile dependency, rapid urban sprawl, and limited incentives for energy efficiency or alternative modes of transportation [16]. Throughout much of the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, national transportation strategies prioritized road expansion and boosting car ownership. Saudi cities such as Riyadh, Jeddah, and Dammam developed around sprawling urban layouts, low-density development, and limited public transportation options, resulting in traffic congestion, deteriorating air quality, and increasing greenhouse gas emissions [16]. Until the mid-2010s, electric vehicles were not included in Saudi policy discussions, with mobility planning heavily focused on petroleum economics [17].

The launch of Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 in 2016 marked a shift in national transportation and energy strategies. Vision 2030 frames sustainability, quality of life, and economic diversification as central priorities, linking mobility reform with energy transition and climate action [18]. Several landmark initiatives highlight this shift, including the National Transport and Logistics Strategy (NTLS), launched in 2021, sets targets for multimodal systems, emissions reduction, and the integration of EVs into passenger and logistics transportation [19]. The Saudi Green Initiative (SGI), also launched in 2021, establishes climate and sustainability goals, including electrifying 30% of Riyadh’s vehicle fleet by 2030 [20]. The Public Investment Fund (PIF) has invested heavily in this sector, including acquiring a majority stake in Lucid Motors in 2018 and launching CEER Motors in 2022—Saudi Arabia’s first domestic EV brand developed in partnership with Foxconn and BMW [21]. Additionally, megaprojects such as NEOM and The Line envision zero-carbon, car-free environments with electrification as a key element [22]. Together, these initiatives represent the institutionalization of e-mobility into Saudi national policy and a shift from rhetorical sustainability to practical projects and industrial capacity development.

Despite these ambitious commitments, the adoption of e-mobility in Saudi Arabia still faces some challenges. The study highlights four ongoing obstacles: (1) affordability: EVs remain beyond the reach of most middle-income residents [23], and there are few subsidies, tax exemptions, or consumer incentives to offset the high upfront costs. (2) Infrastructure gaps: Public charging stations are concentrated in metropolitan areas like Riyadh, Jeddah, and Dammam, while smaller cities and rural areas remain underserved [24]. (3) Cultural inertia: Long-standing reliance on cheap fuel and cultural preferences for large, gasoline-powered vehicles create skepticism about EV practicality and performance [25]. (4) Equity concerns: Current e-mobility strategies mainly favor elites who can afford EVs or reside in cities with early infrastructure deployment. Middle and lower-income groups, and residents of peripheral cities, are mostly excluded from early adoption [26]. This situation creates a broader structural paradox. On one side, Saudi Arabia aims to reinvent itself as a global leader in clean energy and sustainability. On the other, its local transportation system still demonstrates heavy oil dependence, raising doubts about whether electrification is truly a genuine change or just a symbol.

Beyond its academic contribution, this study provides practical insights for policymakers, transportation planners, and institutional stakeholders responsible for Saudi Arabia’s mobility shift. By tracing the evolution of e-mobility policies, the analysis highlights which strategies have become formalized, which policy areas still need development, and where implementation gaps remain. These insights are particularly useful for decision-makers involved in planning charging infrastructure, industrial localization, incentive creation, and national decarbonization initiatives. The comparison with Norway, China, and the UAE provides actionable policy lessons that can support future regulatory reforms and investment decisions. This practical focus emphasizes the importance of studying policy evolution as a foundation for effective and equitable e-mobility adoption.

This study addresses two key research questions: How has the policy discourse on electrification and e-mobility evolved in Saudi Arabia since the launch of Vision 2030? And to what extent have institutional strategies and flagship projects transformed rhetorical commitments into practical reforms for sustainable mobility? In pursuing these questions, the study sets the following objectives: conduct a longitudinal analysis of Saudi e-mobility policy discourse (2010–2025); build a content analysis dataset tracking references to electrification in national strategies, institutional reports, and megaproject documentation; develop a comparative policy dataset comparing Saudi Arabia’s approach with other countries; compile a timeline dataset of many milestones in Saudi e-mobility policy; and identify barriers related to affordability, infrastructure, and equity that hinder policy implementation.

The study contributes to both academic and policy discussions. Existing research on Saudi Arabia’s transportation system has primarily concentrated on public transportation and active mobility. However, few studies have systematically explored the development of e-mobility policies. By creating original datasets and performing a longitudinal policy analysis, this paper offers empirical evidence of how Saudi discourse shifted from oil dependence to electrification, enhancing debates on sustainable transportation in oil-dependent economies. Regarding policy contributions, the analysis reveals gaps in affordability, infrastructure distribution, and equity. By comparing Saudi Arabia’s policies with others, the study provides recommendations for inclusive and equitable adoption strategies aligned with Vision 2030, the Saudi Green Initiative, and international frameworks like the Paris Agreement and the Sustainable Development Goals.

2. Methodology for Literature Selection and Document Retrieval

This review used a clear and systematic document analysis method inspired by PRISMA guidelines, adapted for qualitative policy research [27]. The objective was not to do a systematic review of empirical results, but to identify, screen, and analyze policy and institutional documents that show the development of e-mobility governance in Saudi Arabia from 2010 to 2025.

2.1. Search Strategy, Transparency, and Reproducibility

Document retrieval was carried out from March to August 2025 (with access dates recorded to ensure reproducibility) across official digital portals. Academic literature was searched using academic databases such as Google Scholar, Scopus, and Web of Science, while policy and institutional documents were obtained directly from official portals and institutional databases. Searches were conducted using predefined keywords related to electric vehicles, sustainable transportation, etc. Terms were combined using Boolean operators (AND, OR) according to each database’s requirements. Search results were cross-checked to remove duplicates and to ensure comprehensive coverage across institutional domains.

To promote transparency and full reproducibility, the document identification process adhered to standardized procedures for recording search locations, search terms, access dates, and document metadata [28]. Additionally, for each document, the following metadata were recorded: document type (policy brief, strategy, annual report, peer-reviewed article); publishing institution; publication year; URL/source repository; version number or update date (if applicable); and language (Arabic or English). This systematic logging ensured consistency across the collection and reduced the risk of selection bias. It also provides enough detail for other researchers to replicate the search process and verify document inclusion. In addition, to enhance methodological transparency, this document retrieval process followed a step-by-step search protocol commonly used in policy analysis research. Following Zhou et al. [29], searches were carried out repeatedly in multiple rounds, starting with broad keyword queries and then refining results as new terms appeared during screening. Each retrieval round was logged, and no new document types or themes emerged after the fourth iteration, indicating search saturation. This structured approach ensured that the final corpus was comprehensive, reproducible, and aligned with established standards for policy data collection.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Documents are included in the analysis if they meet specific criteria: authored or endorsed by government entities or official programs; related to a particular topic; published within a designated time frame; and containing meaningful policy-relevant content. Excluded documents are unverifiable sources, duplicate summaries, and publications unrelated to the topic [30].

2.3. Screening Procedures (PRISMA-Adapted)

An adapted PRISMA workflow can be used to organize the steps for document selection: (1) Identification: all documents are initially identified through various sources (2) Screening: titles and abstracts are screened for relevance (3) Eligibility: full-text assessment is conducted; documents are evaluated for credibility, completeness, and policy relevance (4) Inclusion: the final studies are included in the systematic review or meta-analysis [31].

2.4. Overall Methodological Workflow

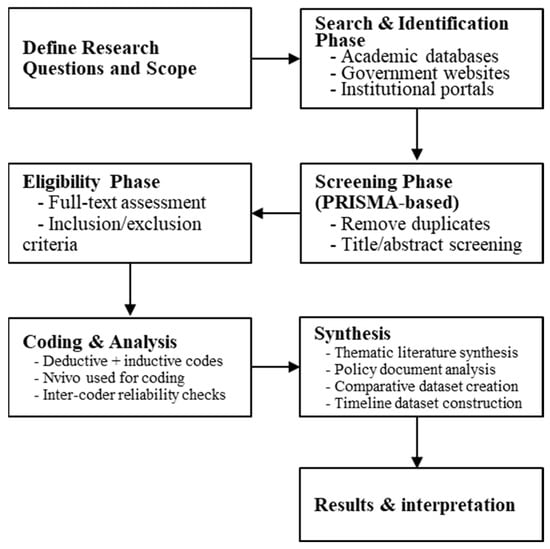

In addition to the PRISMA-adapted screening procedure, this study followed a multi-stage methodological workflow that integrates literature screening, policy document analysis, coding procedures, and synthesis across three datasets [28]. Figure 1 offers a visual overview of the methodological steps, including (1) defining the research scope, (2) identifying documents, (3) PRISMA-based screening, (4) qualitative content analysis using deductive and inductive codes, (5) coding with NVivo, and (6) synthesizing academic themes, policy findings, comparative insights, and timeline development. This figure complements the PRISMA diagram by showing the full process used to produce the study’s results.

Figure 1.

Overall methodology flowchart for the literature review and document analysis.

2.5. Content Analysis Software and Analytical Approach

The qualitative analysis of the documents was conducted using NVivo 14, a computer-assisted qualitative data analysis software (CAQDAS) widely employed for systematic coding and thematic analysis [32]. NVivo was used to manage the entire set of documents (52 Saudi policy documents and 16 comparative documents), facilitating coding, reference counting, memoing, and tracking relationships between themes.

The study adopted a directed qualitative content analysis approach. Deductive codes were developed from established literature. These were supplemented by inductive, emergent codes discovered during multiple readings of the documents. NVivo was utilized to ensure traceability through: (1) code frequency counts; (2) co-occurrence queries to examine thematic relationships; (3) within-case and cross-case comparisons; (4) automated coding reports; and (5) audit trails documenting coding decisions. This software-supported workflow guaranteed transparency, improved replicability, and reduced coder subjectivity throughout the analysis [33,34].

2.6. Coding Framework, Traceability, and Reliability Procedures

To ensure traceability, all documents were coded using NVivo 14, which enabled reference counting, co-occurrence analysis, thematic queries, and extraction of coded text segments. The software environment also maintained an automatic log of coding decisions, memos, and revisions, ensuring a transparent audit trail suitable for replication.

Inter-coder reliability was addressed using a two-step process. First, a sample of documents was independently re-coded later to verify internal consistency. Second, cross-audit procedures were implemented by reviewing coding clusters and resolving discrepancies through iterative refinement. Although formal kappa statistics are usually not required for qualitative policy analysis, these steps helped ensure coding stability, reduce subjective bias, and strengthen methodological rigor.

2.7. Analytical Procedures and Statistical Techniques Considered

Although this study is qualitative and based on document analysis, we maintained analytical rigor by following structured procedures typical in qualitative content analysis. No inferential statistical tests (e.g., t-tests, regression models, ANOVA) were employed because the dataset consists of textual policy documents rather than numerical data. Instead, the analysis relied on descriptive and frequency-based methods appropriate for qualitative policy research. First, reference counting determined the frequency of thematic codes across the 52 Saudi policy documents and 16 comparative documents. Second, co-occurrence analysis evaluated how often themes appeared together. Third, temporal mapping traced policy development over the 2010–2025 timeline. Fourth, saturation checks verified that no new codes emerged after multiple rounds of coding. These steps ensure transparency and demonstrate that the analysis complies with established qualitative standards, even though formal statistical hypothesis testing was not suitable for the data’s nature.

3. Literature Review

3.1. Global Sustainable Transportation and E-Mobility Transitions

The transportation sector plays a vital role in shaping sustainable practices for the future. According to the International Energy Agency [35], transportation accounts for nearly 24% of global CO2 emissions, with road transportation responsible for about 74% of this share. These figures highlight the urgency of transforming mobility systems to meet climate mitigation commitments under the Paris Agreement and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDG 7: Affordable and Clean Energy, SDG 11: Sustainable Cities, and SDG 13: Climate Action).

Scholars widely agree that achieving sustainable mobility requires a comprehensive approach, combining shifts to public transit and active commuting with the adoption of low-carbon vehicle technologies [12,13]. Within this broader paradigm, electric vehicles (EVs) have emerged as a cornerstone of sustainable transportation transitions [36]. They are widely promoted for their potential to lower emissions, improve local air quality, and boost energy efficiency by separating mobility from fossil fuel consumption [14].

Recent literature further supports these trends. Studies published between 2020 and 2025 highlight the growing connection between EV adoption, battery supply chains, and national decarbonization efforts [36]. The IEA and UNEP stress that countries with aligned industrial and consumer incentives—such as China, Korea, and several European Union member states—see faster EV adoption [37,38]. New research by Hall and Lutsey [39] also shows that the expansion of rapid charging infrastructure is now the strongest indicator of national adoption rates. Meanwhile, Geels et al. [40] contend that EV transitions should be viewed as multi-actor sociotechnical shifts rather than isolated environmental policies, reinforcing the need for long-term and governance-focused analyses like the one presented in this study.

Globally, the adoption of EVs has accelerated dramatically over the past decade. For example, in Norway, EVs made up about 90% of new car sales in 2024, making it as the global leader in EV penetration [41]. This success was driven by a comprehensive set of consumer-focused incentives, including tax exemptions, toll waivers, free parking, and extensive charging infrastructure [42]. Similarly, China has become the largest electric vehicle market worldwide by combining industrial policies—focused on large-scale battery manufacturing and domestic production—and consumer incentives, including subsidies and purchase quotas [43]. The United States and European Union have adopted hybrid strategies, using federal or regional subsidies, strict emissions regulations, and infrastructure development to promote adoption [44].

Despite this momentum, obstacles to EV adoption remain across different settings. High initial costs, even when offset by future savings, discourage many households [23]. Charging infrastructure gaps and range anxiety diminish consumer confidence, especially in rural areas or countries with large geographies [24]. Cultural and behavioral factors also influence perceptions, as car users often associate EVs with performance issues, limited status signals, or reduced convenience compared to gasoline vehicles [25].

Literature in the field also highlights the political aspects of e-mobility. Breetz et al. [44] argue that clean energy transitions are influenced by competing political logics: industrial policy focusing on economic competitiveness, environmental policy emphasizing emissions reductions, and equity principles stressing accessibility and fairness. The success of EV transitions relies on how governments balance these logics within their policy frameworks.

In summary, the global literature shows that EVs are central to sustainable mobility transitions, but their widespread adoption depends on policy consistency across industrial, infrastructural, and consumer sectors. Countries with coordinated, multi-faceted strategies—such as Norway and China—have achieved substantial adoption, while others fall behind due to fragmented or symbolic policies.

To synthesize global academic literature, the reviewed studies were coded according to their dominant themes. Table 1 summarizes the proportion of global academic sources addressing each theme and identifies their temporal trends between 2010 and 2025.

Table 1.

Global Sustainable Transportation & E-Mobility Themes.

3.2. Barriers to E-Mobility Adoption

Although EVs are often promoted as environmentally friendly, their adoption faces several barriers that vary by region and socio-economic factors. Four main barriers stand out: cost, infrastructure issues, cultural perceptions, and equity concerns. Economic barriers remain the most commonly cited challenge. EVs generally have a higher upfront cost compared to similar internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles, making affordability a challenge for middle- and low-income households. While the total cost of ownership can be lower over time due to reduced fuel and maintenance expenses, these savings are less obvious to consumers without supportive financial mechanisms such as subsidies, tax exemptions, or leasing options [45]. Infrastructure gaps present another major obstacle. The lack of widespread, dependable charging stations undermines consumer confidence, especially in countries with scattered populations or large rural areas. Experts highlight the importance of public–private partnerships in building charging infrastructure, pointing out that government investment often needs to support private sector efforts during the early phases of adoption [46]. Cultural and behavioral inertia also slow adoption. Sonnberger and Graf [47] argue that shifts in mobility are not just technological but also social, requiring changes in cultural norms, consumer perceptions, and daily routines. In societies where car ownership is connected to social status, convenience, and fuel cost, EVs might be seen as impractical or unappealing. Lastly, equity issues are increasingly emphasized in the literature. Martens [48] and Litman [12] show that sustainable transportation transitions risk reinforcing inequalities if policies mainly benefit wealthy consumers. Without equity-focused measures, EVs may become luxury items only accessible to the wealthy, while disadvantaged groups continue to rely on polluting, inefficient transportation modes.

Recent research (2023–2025) emphasizes that affordability and infrastructure inequality continue to be the main global challenges. Recent studies in oil-producing regions, including the Gulf, identify social perceptions, limited affordability for mid-income groups, and weak financing systems as ongoing barriers to adoption [49,50,51].

To provide analytical depth to the discussion of e-mobility barriers, the reviewed studies were quantified to determine the prevalence of each barrier category. Table 2 presents the percentage of academic sources addressing each barrier type, alongside trend classifications.

Table 2.

Barriers to E-Mobility Adoption.

3.3. E-Mobility in the Gulf Context

The Gulf region presents a unique context for e-mobility transitions. Rentier state theory emphasizes that oil wealth shapes governance systems and social contracts, creating reliance on resource rents to sustain subsidies, welfare systems, and development models [52]. In the transportation sector, this translates into highly subsidized fuel prices, cheap car ownership, and road-centered urban development [53]. The Gulf’s reliance on automobiles is not only a result of consumer preference but also due to institutional path dependence, as years of planning prioritized roads, highways, and car-focused infrastructure while ignoring alternative transportation options [54].

In recent years, however, Gulf states have begun experimenting with e-mobility strategies as part of broader efforts to diversify and address climate change. The United Arab Emirates (UAE) has set a goal for at least 10% of all vehicles on the road to be electric by 2030; therefore, the government is offering incentives such as toll exemptions, free registration, and free parking [55]. Qatar announced its green mobility targets aligned with its National Vision 2030, including the Electric Vehicle Strategy 2021, which has set ambitious goals such as EVs making up 10% of total vehicle sales by 2030 [56]. Oman has experienced a significant rise in EVs; the number of EVs grew by 650% from 2021 to 2023. This impressive growth is supported by substantial infrastructure development, with Oman’s charging network increasing from 40 public charging stations in 2022 to over 100 in 2023 [57].

Recent Gulf-focused studies (2020–2025) show increased EV policy activity in the UAE, Qatar, Oman, and Bahrain, driven by commitments to carbon neutrality and industrial diversification [50,58,59,60]. Research from journals indicates that Gulf-wide transitions are still uneven: while the UAE leads in infrastructure deployment [55], Saudi Arabia’s industrial localization strategy has become more prominent since 2021 [21] positioning it as a quickly emerging regional leader. The Gulf region exhibits a distinct research pattern shaped by national visions, rapid economic transformation, and varying institutional capacities. To capture these nuances, Table 3 quantifies the thematic distribution of GCC-focused academic studies.

Table 3.

E-Mobility Themes in the Gulf Region.

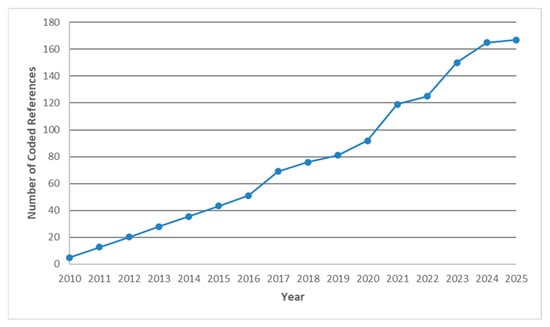

3.4. Time-Trend Analysis of Academic Literature (2010–2025)

To better understand global and regional research activity related to this review, a time-trend analysis of academic publications from 2010 to 2025 was conducted. All peer-reviewed studies included in the literature review were categorized into three analytical groups: (1) Global sustainable transportation and e-mobility transitions; (2) Barriers to e-mobility adoption; and (3) e-mobility in the Gulf context.

It is evident that there has been significant growth in academic interest in these fields over time. There is a clear upward trend in global scholarly work on sustainable mobility and transportation electrification, with a notable acceleration after 2016. This reflects the global policy shift following the Paris Agreement and the rapid increase in EV adoption in China, Europe, and the United States. Concerning research trends related to barriers to e-mobility adoption, before 2015, only a few studies focused on charging infrastructure, range anxiety, or affordability. However, from 2018 to 2025, publications addressing economic barriers, equity gaps, grid integration, and consumer acceptance increased substantially, highlighting real-world challenges faced by governments worldwide. The number of academic publications on e-mobility in the Gulf region was limited before 2017, but interest grew rapidly after the launch of Saudi Vision 2030, especially around topics such as charging networks, environmental policies, industrial localization, and the viability of e-mobility in oil-dependent economies. Overall, academic focus on sustainable mobility, EV adoption challenges, and Gulf region transitions has expanded considerably over the past decade. This trend underscores the importance of the current study and emphasizes the swift development of global and regional knowledge on transport electrification.

To complement the narrative review of international policy approaches, Table 4 synthesizes the prevalence and temporal evolution of major policy instruments used globally to accelerate e-mobility adoption. Quantifying these instruments provides a clearer comparison between global practices and emerging trends.

Table 4.

Global Policy Instrument Landscape.

3.5. Saudi Vision 2030 and the Emergence of E-Mobility

Saudi Arabia shares several e-mobility characteristics with its Gulf neighbors. Prior to 2016, EVs and alternative fuels were not part of official discussions, as the country’s energy and transportation policies focused on oil exports and fuel subsidies. However, the launch of Vision 2030 marked a major shift. Saudi Vision 2030 explicitly connects transportation reform to economic diversification, environmental protection, and quality of life [18]. The subsequent National Transport and Logistics Strategy (NTLS) committed to integrating electrification into passenger and freight transportation systems [19], while the Saudi Green Initiative set measurable targets such as electrifying 30% of vehicles in Riyadh by 2030 [20]. These strategies incorporate electrification within broader climate and energy goals reforms.

At the institutional level, the Public Investment Fund (PIF) has become a key supporter of e-mobility. In 2018, it bought a majority share in Lucid Motors, marking the first significant industrial commitment to EVs. Plans for a Lucid factory in King Abdullah Economic City (KAEC) aim to produce up to 150,000 EVs each year. In 2022, the PIF launched CEER Motors, the Kingdom’s first local EV brand, in partnership with Foxconn and BMW [21]. These moves show how electrification is presented not only as an environmental strategy but also as an industrial diversification policy. At the urban level, megaprojects such as NEOM and The Line have integrated EVs and futuristic mobility concepts into their designs, aiming for zero-carbon, car-free, or electric-only systems [22].

Despite these institutional commitments, scholars highlight several policy gaps. Alotaibi et al. [51] and Alyamani et al. [61] note that affordability remains a barrier, as EVs are priced beyond the reach of most Saudi residents. Charging infrastructure is still limited, and residents worry about the safety and effectiveness of batteries at high temperatures, as well as the ability of EVs to perform in desert conditions. Additionally, cultural norms tied to cheap fuel and car ownership persist, contributing to skepticism about EV adoption. Thus, although Saudi Arabia has made significant progress in incorporating e-mobility into Vision 2030 and related strategies, the literature highlights the gap between policy goals and everyday accessibility.

3.6. Knowledge Gaps and Research Contribution

The review of literature identifies several knowledge gaps that this study aims to fill. Most studies focus on individual initiatives or general discussions of diversification. Few examine the evolution of e-mobility discourse over time. Existing research often highlights Saudi Vision 2030′s rhetoric but does not systematically evaluate how commitments turn into projects, infrastructure, or adoption. The social aspects of e-mobility—especially affordability and geographic distribution—are underexplored in the Saudi context. While there are studies on the UAE or Norway, few compare Saudi Arabia within a framework of industry-first versus consumer-first strategies. By addressing these gaps, the study contributes to both academic understanding and policy discussions on sustainable mobility in oil-dependent economies.

4. Policy Document Analysis Methodology

4.1. Research Design

This study adopts a qualitative, document-based policy analysis to explore the development of e-mobility discourse in Saudi Arabia from 2010 to 2025. Document-based analysis is suitable for countries where official strategies, institutional reports, and policy announcements serve as primary sources for mobility reform narratives. The research is structured as a longitudinal policy review in three phases: (1) oil-centric continuity (pre-2016)—a period dominated by subsidized fuel, road expansion, and a lack of electrification discourse. (2) vision transition (2016–2020)—marked by the adoption of sustainability language and early mentions of electrification following the launch of Vision 2030. (3) electrification drive (2021–2025)—characterized by the institutionalization of EV policies within the NTLS, the SGI, and the launch of CEER Motors (2022). By analyzing continuity and change across these phases, the study provides a timeline of how electrification became part of Saudi policy and how it was institutionalized.

The research design focuses on three original datasets: a content analysis dataset with a large number of coded references to e-mobility across 52 Saudi documents, a comparative policy dataset contrasting Saudi Arabia’s strategies with those of the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Norway, and China, and a timeline dataset tracking 25 milestones in Saudi e-mobility policy from 2010 to 2025. These datasets enable both within-case analysis (Saudi Arabia over time) and cross-case comparison (Saudi Arabia compared to other contexts).

4.2. Data Sources

A purposive sampling strategy was employed to capture the scope of Saudi e-mobility discourse at the national, institutional, and project levels. The final dataset includes 52 Saudi documents and 16 comparative documents, along with supplementary reports. The Saudi documents cover: national strategies (e.g., Vision 2030 reports, NTLS, SGI); institutional reports (e.g., MTLS reports and publications, Ministry of Energy reports); economic policies (e.g., PIF reports and news related to Lucid Motors and CEER Motors); urban megaproject documentation (e.g., NEOM and The Line, Green Riyadh reports); legislative and regulatory news. Comparative documents include the UAE EV strategy, Norway EV incentives, and China’s New Energy Vehicle (NEV) policies. Additionally, some supplementary sources related to IEA, UN-Habitat, news, and media releases were used to triangulate institutional claims.

4.2.1. Source Websites and Institutional Repositories

As stated, documents utilized in this study were obtained from publicly accessible, official Saudi government and institutional websites. The list of repositories used for collecting documents is as follows:

- Ministry of Transport and Logistics Services (MOTLS)—https://www.mot.gov.sa;

- Saudi Vision 2030 Official Portal—https://www.vision2030.gov.sa;

- National Transport and Logistics Strategy (NTLS)—https://www.mot.gov.sa/en/NTLS, accessed on 15 June 2025;

- Saudi Green Initiative (SGI)—https://www.sgi.gov.sa, accessed on 7 June 2025;

- Ministry of Energy—https://www.energy.gov.sa, accessed on 4 May 2025;

- Ministry of Municipal and Rural Affairs and Housing (MOMRAH)—https://www.momrah.gov.sa, accessed on 20 March 2025;

- Public Investment Fund (PIF)—https://www.pif.gov.sa, accessed on 3 April 2025;

- NEOM Mobility Sector—https://www.neom.com/en-us/our-business/sectors/mobility, accessed on 2 July 2025;

- EVIQ Electric Vehicle Infrastructure Company—https://www.eviq.sa, accessed on 22 July 2025;

- KAPSARC Publications Repository—https://www.kapsarc.org/research, accessed on 3 June 2025;

- General Authority for Statistics (GASTAT)—https://www.stats.gov.sa, accessed on 8 May 2025;

- National Academy of Vehicle and Automotive (NAVA)—https://www.nava.edu.sa, accessed on 15 April 2025.

These websites were accessed using predefined keywords: “electric vehicle,” “EV manufacturing,” “e-mobility,” “transport electrification,” “sustainable transport,” “sustainable mobility,” “charging infrastructure,” “mobility transition,” “industrial localization,” and “transport policy.” Only official documents such as policy strategies, regulatory guidelines, annual reports, project briefs, and institutional publications were included.

4.2.2. Document Selection and Inclusion Criteria

Documents were included if they met the following inclusion criteria: (1) authored or endorsed by a governmental agency, national institution, or official program; (2) contained explicit references to transportation, energy transition, mobility planning, or sustainability; (3) published between 2010 and 2025; (4) relevant to the evolution of e-mobility policy. Documents were excluded if they: (1) lacked verifiable institutional authorship; (2) consisted solely of opinion pieces, media commentary, or editorial content; (3) focused exclusively on unrelated sectors (e.g., agriculture, tourism); (4) duplicated information across institutional summaries.

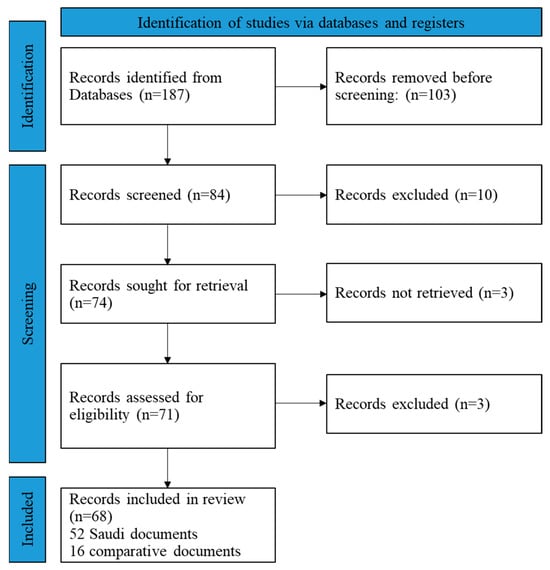

An adapted PRISMA-style workflow (Figure 2) organized the process of identifying and selecting documents for analysis. The procedure involved steps: (1) Identification, where an initial pool of 187 documents was collected from official portals and institutional databases; (2) Screening, during which titles and abstracts were reviewed for topical relevance, reducing the set to 84 documents; (3) Eligibility, involving full-text review to evaluate credibility, comprehensiveness, and alignment with the study’s policy focus; and (4) Inclusion, resulting in a final set of 52 Saudi policy documents and 16 international comparative documents from Norway, China, and the UAE.

Figure 2.

PRISMA-adapted flowchart of the document selection process.

4.2.3. Quality Assessment

To ensure data source reliability, all documents were evaluated using a standardized quality assessment protocol adapted from qualitative policy analysis frameworks. Each document was assessed in three dimensions:

- (a)

- Source credibility: Priority was given to official government strategies, institutional reports, regulatory guidelines, and project documentation. Documents from ministries, Vision 2030 programs, and megaproject authorities (e.g., NEOM, The Line) were categorized as highly credible sources.

- (b)

- Content completeness and specificity: Documents were assessed based on the presence of clear policy statements, implementation details, mobility-related targets, infrastructure descriptions, or industrial commitments. Documents lacking substantial information or containing only general statements were downgraded.

- (c)

- Relevance to e-mobility: Documents were screened for explicit references to electric vehicles, charging infrastructure, industrial investments (e.g., Lucid, CEER), sustainable transportation, carbon reduction, or energy transition themes.

4.3. Transparency in Document Selection and Processing

To ensure reproducibility and transparency in methodology, detailed records were maintained throughout the document selection and analysis process. All documents were obtained from publicly accessible sources such as government portals, ministerial websites, Vision 2030 program platforms, and institutional repositories, including the Ministry of Energy, Ministry of Transport and Logistics Services, Ministry of Industry and Mineral Resources, Saudi Green Initiative, National Transport and Logistics Strategy repository, NEOM project portal, and official PIF announcements. Search engines (Google) and internal site searches were used with key terms mentioned earlier. Access dates and document versions were recorded, and only the most recent publicly available documents were included. Documents were screened based on predefined criteria such as policy relevance, explicit mention of mobility, energy, or transport issues, publication dates from 2010 to 2025, and official governmental or institutional origin. A detailed log of the selection, retrieval, and screening process was maintained to prevent bias and ensure full reproducibility.

4.4. Coding Framework and Reliability Procedures

The document analysis followed a structured coding process that combined deductive and inductive strategies. Deductive codes were based on established EV policy frameworks, including policy objectives, economic incentives, industrial localization, infrastructure readiness, regulatory tools, equity considerations, and environmental goals. Inductive codes developed during multiple readings, allowing new themes to emerge. A codebook was created with clear definitions and examples for each code, and the coding was carried out using NVivo. To ensure reliability, a second researcher independently reviewed a subset of documents, and any discrepancies were discussed to improve the coding scheme. Cross-audits were performed to reduce interpretive bias, and all coding decisions were recorded to ensure transparency and traceability.

4.5. Analytical Framework

The analysis was guided by a thematic coding framework based on both sustainability theories and e-mobility literature. Four thematic dimensions were used: (1) institutional commitment—explicit references to electrification in national strategies, creation of EV brands, and government investments. (2) infrastructure development—charging networks, grid integration, and urban planning for EV adoption. (3) industry partnerships—collaboration with global firms (Lucid, CEER, BMW, Foxconn), and local manufacturing initiatives. (4) social equity and accessibility—affordability, inclusive policies, and the geographic spread of EV adoption across cities and income groups. These dimensions enable both quantitative coding (reference frequency) and qualitative analysis (framing, discourse shifts).

4.6. Dataset Construction and Coding

4.6.1. Content Analysis Dataset

All documents were imported into NVivo 14 for systematic coding. A keyword list was created, including terms such as “electric vehicle,” “electrification,” “charging,” “sustainability,” “green transport,” and “carbon emissions.” The coding process followed these steps: (a) initial coding: identifying all references to EVs and related terms. (b) categorization: assigning references to one of the four thematic dimensions. (c) quantification: counting and tabulating reference frequencies per document and per year. (d) validation: a second coder reviewed 20% of the dataset to ensure intercoder reliability (>85% agreement). The result is a dataset of 1240 coded references, providing empirical evidence of how e-mobility discourse expanded over time.

4.6.2. Comparative Policy Dataset

To contextualize Saudi Arabia’s approach, a set of 16 documents from the UAE, Norway, and China were analyzed. Coding focused on: Policy type (consumer-first, industry-first, or mixed), incentive structure (subsidies, exemptions, industrial investment), infrastructure rollout (charging density, urban vs. rural), and adoption outcomes (EV penetration rates).

4.6.3. Timeline Dataset

A chronological dataset of 25 milestones was constructed, tracing Saudi e-mobility events from 2010 to 2025. Each record includes: year, event (such as policy launch, investment announcement, megaproject milestone), source document, and significance (rhetorical, institutional, or implementation). This dataset offers a timeline narrative, illustrating the shift from no EV discussion to its institutionalization.

4.6.4. Coding Procedures and Category Development

The coding process adhered to a structured and reproducible qualitative content analysis protocol. All documents were imported into NVivo 14, which was used for creating nodes, running text queries, counting references, and retrieval. A mixed deductive–inductive approach was employed.

Deductive codes were developed based on established conceptual frameworks in sustainable transport, socio-technical transitions, and e-mobility governance. These included: institutional commitment, regulatory development, charging infrastructure, industrial partnerships, domestic manufacturing, environmental targets, equity considerations, financial instruments, and policy coherence. Code definitions were created before coding and linked to supporting literature to ensure conceptual clarity.

Inductive codes emerged during repeated readings of the documents. These captured context-specific themes, such as megaproject-driven mobility narratives, branding discourse, rentier-state policy path dependence, symbolic policy framing, and infrastructure-readiness constraints. New codes were added only when a concept appeared across multiple documents. Each new inductive code was defined, documented, and incorporated into the evolving codebook.

NVivo’s reference-counting features were used to quantify the frequency of coded segments across the 52 Saudi documents and 16 comparative documents, enabling trend identification over time. To reduce coder bias, a secondary coder independently reviewed 20% of the dataset, focusing on alignment with the codebook and consistency in applying definitions. The intercoder reliability score was 85% (Cohen’s kappa = 0.82), which meets accepted thresholds for qualitative content analysis. Discrepancies were discussed and resolved through consensus, and the final coding applied these harmonized rules. This coding framework ensures methodological rigor, enhances reproducibility, and aligns with best practices recommended in qualitative policy-analysis literature.

5. Results

The document-based analysis reveals a clear trend in Saudi Arabia’s transportation and energy policies: a shift from oil-centric continuity (before 2016) to a Vision 2030 transition (2016–2020), and then to the institutionalization of electrification (2021–2025). This section presents findings from these three stages, supported by the study’s three datasets: a content analysis dataset of policy references, a comparative policy dataset comparing Saudi Arabia’s efforts with international experiences, and a timeline dataset tracking 25 milestones in Saudi e-mobility policy.

5.1. Visualizing Policy Discourse Trends

To complement the qualitative findings, three visualizations were created to illustrate the temporal and thematic patterns that emerge from the coded dataset. Figure 3 shows a clear spatiotemporal escalation in EV-related discourse, showing three distinct policy periods. Before 2016, mentions of electrification were scarce, reflecting an oil-rentier mobility model focused on subsidized fuel and automobile-centric planning. The sharp increase after 2016 coincides with the launch of Vision 2030, which brought in sustainability language and framed transport electrification as part of a larger economic diversification effort. The more rapid growth after 2021 indicates a shift from rhetorical promises to tangible institutional actions. This aligns with the introduction of the NTLS, the SGI, and the creation of CEER Motors and EVIQ. The pattern supports the study’s main claim: Saudi e-mobility policy has quickly shifted from symbolic talk to real institutional grounding within a short period.

Figure 3.

Annual distribution of coded references across Saudi policy documents (2010–2025).

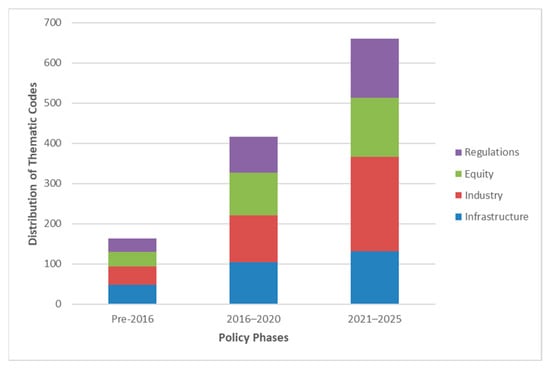

Figure 4 shows how Saudi Arabia’s focus on e-mobility has changed over time. Before 2016, policy references mainly focused on general infrastructure and sustainability, with limited institutional commitment or regulatory guidance. From 2016 to 2020, industrial localization increased quickly, reflecting growing interest in EV manufacturing partnerships (e.g., Lucid Motors) and early experimentation driven by large projects. The biggest shift happens between 2021 and 2025, when all thematic areas become more prominent. References to institutional commitment and regulation rise due to NTLS and SGI, while infrastructure and equity themes increase as the government starts formalizing charging deployment and addressing affordability issues. This trend supports the idea that Saudi Arabia is moving toward a coordinated, government-supported transition—although equity remains underrepresented, confirming one of the main gaps found in the analysis.

Figure 4.

Distribution of major thematic codes across the three phases.

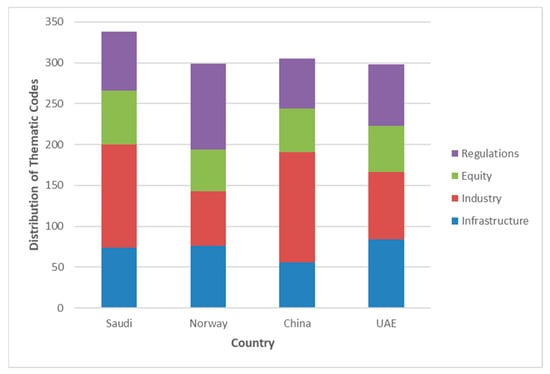

Figure 5 offers comparative evidence of Saudi Arabia’s unique e-mobility policy trajectory. Saudi Arabia places a significantly higher emphasis on references to industrial development and megaproject-led narratives compared to Norway and the UAE. This supports the “industry-first” approach, where electrification is seen as a means for economic diversification rather than an immediate consumer transition. Norway focuses strongly on regulatory tools and consumer incentives, aligning with its success on the demand side and leading EV market share. China’s profile demonstrates a balanced dual strategy, combining large-scale industrial policies with consumer-focused measures, which explains its dominant position in the global market. The UAE shows a moderate focus across different categories but mainly emphasizes infrastructure readiness and symbolic initiatives. Overall, these comparative patterns strengthen the study’s claim that Saudi Arabia’s transition is structurally unique, highly compressed in time, and rooted mainly in industrial policy and institutional commitment.

Figure 5.

Comparative distribution of thematic codes across Saudi Arabia, Norway, China, and the UAE.

5.2. Comparative Policy Dataset

To provide context for Saudi Arabia’s experience, policies from Norway, China, and the UAE were examined. The findings highlight apparent differences in policy strategies and implementation results. Norway’s approach mainly centers on consumer-focused transition; its success relies on demand-side policies—including tax exemptions, toll waivers, and consumer incentives—paired with nationwide charging networks [42]; adoption outcomes show the success of consumer-first approaches strategies. China’s experience mainly centers on industrial and consumer synergy; it combines industrial investment in battery supply chains with consumer subsidies, fostering both domestic production capacity and widespread adoption [43]. This dual-track approach differs from Saudi Arabia’s industry-first strategy.

The UAE adopted a mixed approach, combining symbolic projects (e.g., Expo 2020 EV fleets) with limited consumer incentives (free parking, free registration, toll exemptions) [55]. In the UAE, EV adoption remains modest but is more consumer-oriented than in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Arabia’s experience follows a unique path. E-mobility in Saudi Arabia is mainly driven by supply side investments (Lucid, CEER) and global branding projects (NEOM, The Line), with some focus on consumer incentives. As a result, adoption is mostly limited to the high-income population, unlike Norway’s widespread adoption or China’s large-scale market expansion (Table 5).

Table 5.

Comparative approaches to e-mobility.

5.3. Content Analysis Dataset

The content analysis of 52 Saudi documents produced 1240 coded references to electrification and e-mobility between 2010 and 2025. To quantify the relative emphasis of each policy area within the Saudi policy corpus, Table 6 presents the distribution of coded references across the 1240 excerpts analyzed from the 52 documents. This provides a clearer picture of which themes dominate the national e-mobility agenda and how their prominence has evolved across the 2010–2025 period.

Table 6.

Saudi E-Mobility Policy Themes.

As shown in Table 7, between 2010 and 2015, no references to electric vehicles or electrification appeared in Saudi transportation or energy documents. The national mobility policy was firmly oriented towards road expansion and fuel subsidies, maintaining car-centered planning. This matches the broader literature describing Gulf states as historically resistant to alternative fuels because of rentier political economies [15,53]. The launch of Vision 2030 in 2016 marked the first appearance of electrification discourse. During this period, 152 references to EVs and related concepts were identified. Most references were aspirational, emphasizing Saudi Arabia’s future role as a global sustainability leader rather than action. Key examples include the Vision 2030 Strategic Plan (2016), which mentions “adopting green technologies/initiatives” and “sustainable transport” [18]; the PIF’s investment in Lucid Motors (2018) introduced electrification into Saudi industrial policy [21]; NEOM and The Line concept briefs presented visions of futuristic, car-free, electric-first cities [22]. Although charging stations were piloted in Riyadh, Jeddah, and Dammam, rollout was minimal. The rhetoric emphasized branding and diversification more than consumer adoption.

Table 7.

Frequency of EV-related references in Saudi policy documents by phase (2010–2025).

The period after 2021 shows a dramatic expansion of EV discourse, with 813 references across government documents, institutional reports, and media statements. The conversation shifted from rhetoric to institutionalization, with clear targets and measurable commitments. Key developments include: The NTLS (2021) positioned e-mobility as a central emissions-reduction strategy [19]. The SG I (2021) committed to electrifying 30% of Riyadh’s vehicles by 2030 [62]. The launch of CEER Motors in 2022, Saudi Arabia’s first domestic EV brand, positioned electrification as an industrial diversification project [21]. This period thus reflects a policy shift from symbolic discourse to institutional frameworks and the start of implementation.

5.4. Timeline Dataset

The timeline dataset of 25 milestones illustrates the progression from absence to institutionalization and implementation. This timeline illustrates a rapid policy pivot: within less than a decade, Saudi Arabia went from having no EV discussion to setting national targets (Table 8).

Table 8.

Selected milestones in Saudi e-mobility policy (2010–2025).

5.5. Cross-Phase Analysis

Analyzing findings across the three phases shows clear shifts in policy language, energy strategies, institutional commitments, infrastructure deployment, and adoption scope (Table 9). The data indicate that Saudi Arabia’s electrification has become formalized at the policy level but remains uneven in implementation, especially concerning affordability and geographic distribution.

Table 9.

Evolution of Saudi e-mobility policy across phases.

5.6. Emerging Challenges

The analysis highlights four ongoing challenges. EVs continue to be inaccessible to middle-income Saudis, especially since no subsidies, tax exemptions, or consumer incentives [51,61]. Charging networks are mostly available in major cities [24], while rural areas remain excluded. Relying on cheap petrol fuels skepticism about EV practicality [25]. Adoption stays focused on elites, but lower-income households and residents in peripheral cities are mostly left out of early adoption [26,61]. These challenges highlight the gap between ambition and accessibility, a tension also seen in Gulf neighbors, where e-mobility promotes global branding more than widespread adoption.

5.7. Key Takeaways

The analysis highlights some key takeaways. Saudi Arabia’s e-mobility discourse has rapidly evolved, shifting from total absence (pre-2016) to rhetorical positioning (2016–2020), to institutionalization (2021–2025). The content analysis dataset confirms that references to electrification have increased significantly since 2021, reflecting institutionalization. The comparative dataset shows that Saudi Arabia’s industry-first strategy is unique, contrasting with Norway’s consumer-first approach and China’s dual-track model. The timeline dataset emphasizes the quick pace of change, with major milestones clustered in less than a decade. Despite institutionalization, implementation is still limited by affordability, infrastructure gaps, and issues of equity.

6. Discussion

Before presenting the thematic discussion, five cross-cutting patterns emerging from the coded dataset help contextualize the results. First, industrial localization consistently appears as the strongest theme because national strategies and PIF-led investments prioritize domestic manufacturing and economic diversification. Second, equity remains comparatively underdeveloped, as few documents address affordability, geographic access to charging, or inclusion of middle- and low-income groups. Third, Saudi Arabia’s transition follows an accelerated but compressed trajectory—moving from no EV discourse to institutionalized strategies within a decade—reflecting high state capacity but limited consumer-side measures. Fourth, mobility narratives are strongly shaped by megaprojects (NEOM, The Line, CEER, Lucid), which influence policy language more than adoption data or everyday mobility needs. Fifth, early rollout is heavily concentrated in Riyadh, creating spatial imbalance in infrastructure deployment. These overarching patterns frame the following sections, which discuss global, regional, and national implications.

6.1. Alignment with Global Spatiotemporal Trends

The global analysis (Table 1) shows a growing scholarly focus on policy pathways, charging infrastructure, and industrial localization after 2015. Over the past decade, research has shifted from initial technological feasibility to overall system transitions and industrial competitiveness. These global trends align with the rise of national EV strategies in the EU, China, and the U.S., which gained momentum after the Paris Agreement. By placing Saudi Arabia within this global movement, the discussion emphasizes that the Kingdom’s policy acceleration after 2021 reflects international patterns but occurs over a shorter timescale.

Recent global analyses (2023–2025) reinforce these observations. The IEA and UNEP show that national EV transitions now succeed when industrial policy, charging networks, and grid modernization progress together. Geels et al. [40] describe these trajectories as sociotechnical transitions that require coordinated planning among ministries and private actors. Comparative evidence from the EU, China, and Korea published recently indicates that countries combining local manufacturing with rapid infrastructure rollout achieve much higher EV adoption rates than those relying solely on environmental messaging.

6.2. Interpreting Global Barriers in a Saudi Context

The global barriers outlined in Table 2—high upfront costs, infrastructure limitations, and policy inconsistency—are all evident in the Saudi context. However, the spatiotemporal aspect varies: while cost barriers are decreasing worldwide due to falling battery prices, affordability issues remain significant in Saudi Arabia, where EVs are still priced above international averages. Similarly, infrastructure challenges persist in the Kingdom, even as global markets are rapidly expanding fast-charging networks. This comparison highlights the gaps Saudi Arabia needs to address to align with international adoption patterns.

Recent evidence highlights the ongoing gaps in implementation. Studies from China and the EU show that affordability incentives, standardized charger deployment, and consumer financing programs are crucial for speeding up adoption. Gulf-focused research from 2020–2025 similarly finds that without tariff reform, clear permitting guidelines, and investment in public charging, early EV markets struggle to grow beyond pilot stages. These findings emphasize the need for coordinated regulatory and infrastructural measures in the Saudi context.

6.3. Gulf Region Trajectories and Saudi Arabia’s Position

Table 3 shows that GCC research is increasingly focusing on vision-driven policy coordination and infrastructure readiness. The UAE leads regionally with early charger deployment, while Saudi Arabia’s progress accelerates after 2021. Over time, Saudi Arabia is shifting from a lagging adopter to a regional leader, fueled by industrial investments (CEER, Lucid) and strategic initiatives (EVIQ, NTLS). This indicates a spatiotemporal shift where Gulf electrification is becoming more coordinated and industry-driven.

However, recent studies (2020–2025) demonstrate that equity considerations remain a key barrier for EV transitions in both global and Gulf contexts. Research from the UAE, Qatar, and Oman documents unequal access to charging, limited financing options for middle- and low-income households, and concentration of benefits among higher-income early adopters. These findings mirror international evidence showing that EV policy without equity mechanisms tends to reinforce existing mobility inequalities. This suggests that Saudi Arabia’s emerging EV strategy would benefit from explicit affordability and accessibility measures.

6.4. Saudi Arabia’s Policy Evolution Across Phases

The three phases outlined in the Results section are also key to understanding the national EV transition: Phase 1 (pre-2016): No significant EV policy; Phase 2 (2016–2020): Vision-driven exploration and initial industrial commitments; Phase 3 (2021–2025): Rapid institutionalization, large-scale industrial localization, and structured infrastructure initiatives. This timeline shows a shift from fragmented to coordinated policy and from exploration to implementation. The discussion should clearly emphasize this as a contribution to understanding energy transitions in oil-dependent economies.

6.5. Interpreting Saudi Policy Themes

Table 6 highlights the emphasis on industrial localization (32%), institutional commitment (23%), infrastructure (23%), and equity (22%). The discussion should explain why these themes are important: Industrial localization remains dominant because Saudi Arabia aims to become a manufacturer rather than just a consumer. Institutional commitment has grown because of NTLS, SGI, and alignment with Vision 2030. Infrastructure stays moderate because implementation started late, after 2021. Equity remains the least developed dimension of the transition—representing a critical weakness and a key contribution highlighted by this study.

6.6. Contribution to the Literature

This study offers the first long-term spatiotemporal mapping (2010–2025) of Saudi Arabia’s e-mobility transition, placing national developments within global and Gulf-region trends. By quantifying 1240 coded references, identifying policy changes specific to each phase, and comparing Saudi Arabia with leading EV countries, the study goes beyond previous Gulf research that is mostly descriptive or focused on institutions. The analysis highlights the ongoing neglect of equity as a policy gap and offers a repeatable framework for studying electric mobility transitions in oil-dependent economies.

6.7. Policy Implications and Recommendations

The findings of this study point to several policy directions that can support Saudi Arabia’s transition toward electrified mobility. These recommendations are organized around four domains—governance, infrastructure, economic incentives, and social equity—each of which is essential for strengthening institutional capacity and achieving the goals of Vision 2030.

6.7.1. Governance and Institutional Coordination

Enhancing governance structures is central to accelerating the e-mobility transition. A dedicated national EV transition authority could coordinate efforts among the Ministry of Energy, the MTLS, municipalities, and the PIF. This organization would ensure regulatory consistency, oversee infrastructure deployment, and monitor progress toward national targets. Additionally, developing a national EV master plan for 2025–2040 would create a unified roadmap with phased adoption goals, infrastructure milestones, and fleet electrification strategies. International experiences—such as Norway’s phased EV roadmap and China’s New Energy Vehicle (NEV) industrial plan—demonstrate the importance of long-term planning tools that align government initiatives with market development. Regular monitoring should also become a core governance function, with annual reports on adoption rates, charging infrastructure density, and the distribution of benefits across cities and income groups.

6.7.2. Infrastructure Development

A second priority is expanding and integrating charging infrastructure across the country. Although initial deployment has mainly focused on Riyadh, Jeddah, and Dammam, expanding the network to smaller cities and intercity highways is crucial for encouraging widespread adoption. Public–private partnerships can play a central role in increasing coverage and lowering the financial burden on the government [46].

Additionally, aligning charging infrastructure with renewable energy efforts would boost sustainability, especially as Saudi Arabia grows its solar capacity under Vision 2030. Incorporating EV-ready parking and charging standards into municipal planning and new housing projects would also promote long-term adoption. These actions follow international best practices in urban planning and strengthen the connection between transportation and energy [14].

6.7.3. Economic and Consumer Incentives

Improving affordability remains essential for expanding access beyond high-income early adopters. Targeted financial incentives—such as reduced import tariffs, temporary VAT adjustments, or direct purchase subsidies—could help middle-income households overcome initial cost barriers. International evidence, particularly from Norway, shows that such incentives are among the most effective ways to encourage early adoption [42]. Complementary financial products, including leasing and low-interest financing schemes offered through partnerships with commercial banks, could further reduce cost barriers, similar to mechanisms used in China [43]. Electrifying public and commercial fleets—including taxis, buses, logistics vehicles, and government vehicles—would help normalize EV use and boost demand for charging infrastructure. Supporting domestic manufacturers, including CEER Motors and Lucid, through localization incentives and supply chain development, would strengthen the long-term economic benefits of transport electrification.

6.7.4. Social Equity and Inclusion

Ensuring equity in the e-mobility transition is essential for avoiding uneven access and reinforcing existing mobility disparities. Policies should focus on expanding charging infrastructure in underserved neighborhoods and secondary cities to promote geographic inclusivity. Electrification of public transportation—such as buses and shared mobility services—would particularly benefit low-income populations who depend more heavily on these services. Public awareness campaigns can also help address social and cultural concerns about EV performance, range, and safety, especially in hot climates. Connecting these campaigns to Vision 2030’s Quality of Life Program can foster cultural acceptance and align public perception with national sustainability goals.

Together, these recommendations draw from emerging transition governance literature, which highlights that successful EV transitions require strong institutional coordination, policy capacity, and transparent data systems [29,40].

By incorporating governance reforms, infrastructure investments, economic tools, and equity-centered approaches, Saudi Arabia can more effectively advance its national electrification efforts and align with global best practices in sustainable mobility.

6.8. Technical Evaluation of Saudi Arabia’s Policy Instruments

The results of this study show that Saudi Arabia’s shift to e-mobility depends on a mix of policy tools that are diverse but uneven. When assessed technically, several strengths and gaps become clear. First, the Kingdom has not yet implemented direct purchase incentives or tax breaks, which are key to early EV adoption in leading markets such as Norway, China, and the United States. Instead, Saudi Arabia’s strategy focuses heavily on industrial localization and incentives based on investment, including capital investments through the Public Investment Fund (PIF), the Lucid manufacturing facility, and the creation of CEER Motors. Although these measures support long-term economic diversification, they do not solve immediate affordability issues for consumers.

Second, the country has not yet adopted fuel economy standards or emissions regulations that match EU or U.S. frameworks. The lack of such regulatory tools limits policymakers’ ability to encourage private-sector fleets to adopt electrification. However, public fleet mandates are beginning to appear, especially through municipal electric bus programs and government fleet targets, although these are still in early development.

Third, Saudi Arabia’s progress in charger interconnection regulations, safety standards, and billing protocols is ongoing but incomplete. The establishment of the Electric Vehicle Infrastructure Company (EVIQ) represents an important step in institutional consolidation, yet the regulatory framework, especially grid interconnection rules, tariff structures for fast charging, and operator certification, still needs further development to ensure interoperability, reliability, and safety on a larger scale.

From a financial perspective, the Saudi model favors public-sector investment in early infrastructure (capex) while expecting private operators to come in at later stages. However, the lack of clear operational expenditure (opex) recovery mechanisms, especially for highway fast charging, creates uncertainties for future investors. Global experience shows that cost recovery models—such as differentiated tariffs, demand charges reforms, and blended finance—are essential during early adoption phases. For freight and logistics operators, financial viability remains uncertain due to the high upfront costs of electric trucks and the need for megawatt charging infrastructure. Without targeted incentives or infrastructure subsidies, adoption in this sector may lag behind that of light-duty vehicles.

Overall, the technical evaluation shows that Saudi Arabia has strong industrial and institutional capabilities but lacks some regulatory and financial tools that are typical in advanced e-mobility transitions. Aligning the policy mix with international best practices—especially in incentives, standards, and cost recovery frameworks—would greatly speed up adoption and enhance consistency between national goals and implementation approaches.

6.9. Recommended Indicators and Metrics for Monitoring E-Mobility Progress

Effective monitoring frameworks are essential for assessing national EV transitions, especially in fast-changing policy environments. International experiences—such as those documented by the International Energy Agency (IEA) [5,7,37,45], the European Union’s Alternative Fuels Infrastructure Regulation (AFIR) [63], and recent transition governance research [29,40]—highlight that strong indicator systems should include measures of adoption, infrastructure, energy, industrial growth, and equity measures. Building on these suggestions and the gaps identified in this study, Table 10 presents a comprehensive set of indicators to support future monitoring of Saudi Arabia’s e-mobility transition. These indicators incorporate global best practices while addressing local priorities related to affordability, geographic inclusion, and institutional coordination.

Table 10.

Recommended indicators for monitoring e-mobility progress in Saudi Arabia.

6.10. Empirical Triangulation with Infrastructure, Market, and Energy Data

To validate the qualitative findings, policy themes were triangulated with empirical indicators whenever available. Saudi Arabia has started expanding its charging network through the Electric Vehicle Infrastructure Company (EVIQ), with public announcements indicating a rapid increase in fast-charging stations across Riyadh, Jeddah, and Dammam [64]. Market reports estimate that EV sales in the Kingdom are increasing annually from nearly 1% in 2025 to 30% by 2050 [17]. These adoption trends support the study’s conclusion that infrastructure and affordability barriers remain significant constraints. From an energy-system perspective, Saudi Arabia continues to expand its renewable energy capacity—aiming for 50% renewables by 2030—which is essential for achieving low-carbon charging. Although detailed grid-impact modeling is beyond this study’s scope, preliminary estimates from international cases suggest that widespread EV adoption would require additional distribution-level upgrades and time-of-use pricing strategies. Incorporating these empirical indicators strengthens the validity of the qualitative patterns identified and highlights the alignment between policy discourse and emerging implementation dynamics.

7. Conclusions

7.1. Conclusions

This study explored Saudi Arabia’s emerging transition toward electric mobility through a systematic analysis of national strategies, institutional reports, and policy documents. The results show that the Kingdom’s EV agenda is accelerating across several domains—including infrastructure development, industrial localization, and regulatory reforms—though issues remain with affordability, institutional coordination, and spatial equity. By combining a multi-level transition approach with a structured document analysis, the study offers a comprehensive overview of the policy environment and highlights where implementation capacity will be most vital in the upcoming years. As national strategies evolve quickly, continued monitoring and future empirical research will be crucial to evaluate the alignment between policy goals and actual mobility outcomes.

7.2. Limitations and Future Research

This study relies solely on publicly available policy documents, which reflect institutional intentions but do not capture on-the-ground experiences or implementation results. Therefore, the analysis does not include stakeholder perspectives or consumer behavior. Future research should complement document analysis with empirical methods—such as expert interviews, household surveys, or field assessments of charging infrastructure—to validate and contextualize the findings.

The document collection, while substantial, is limited to accessible and prominent sources, and the comparative analysis focuses only on Norway, China, and the UAE. Expanding the dataset to include more countries and incorporating quantitative performance indicators—such as adoption rates, grid impacts, and emissions outcomes—would strengthen the analysis. Since e-mobility policy in Saudi Arabia is changing rapidly, longitudinal updates are necessary to track future regulatory, technological, and market developments.

Funding

The author is thankful to the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research at Najran University for funding this work under the Easy Funding Program grant code (NU/EFP/SERC/13/237).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Udendhran, R.; Mohan, T.R.; Babu, R.; Uthra, R.A.; Anupama, C.G.; Selvakumarasamy, S.; Dinesh, G.; Mukhopadhyay, M.; Saraswat, V.; Chakraborty, P. Transitioning to sustainable E-vehicle systems—Global perspectives on the challenges, policies, and opportunities. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2025, 17, 100619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Dong, X.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y. Transportation carbon reduction technologies: A review of fundamentals, application, and performance. J. Traffic Transp. Eng. (Engl. Ed.) 2024, 11, 1340–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayabal, R. Towards a carbon-free society: Innovations in green energy for a sustainable future. Results Eng. 2024, 24, 103121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA Transport Energy and CO2. 2009. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/transport-energy-and-co2 (accessed on 22 May 2025).

- IEA Electrification. Available online: https://www.iea.org/energy-system/electricity/electrification (accessed on 22 May 2025).

- Velho, S.R.K.; Vanderlinde, A.S.G.; Almeida, A.H.A.; Barbalho, S.C.M. Electromobility strategy on emerging economies: Beyond selling electric vehicles. Clean. Energy Syst. 2024, 9, 100166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA. Trends in Electric Cars. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/global-ev-outlook-2024/trends-in-electric-cars (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Wang, C.; Ning, Y.; Adebayo, T.S.; Ali, S. Bridging innovation and Adoption: The asymmetric impact of E-mobility technology budgets on electric vehicle growth. Transp. Policy 2025, 171, 803–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, M.; Kalam, A.; Ikram, A.; Zeeshan, S.; Raza Zahidi, S. Energy transition towards electric vehicle technology: Recent advancements. Energy Rep. 2025, 13, 2958–2996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesquita, A.R.; de Abreu, V.H.S.; Poyares, C.N.; Santos, A.S. Barriers to Electric Vehicle Adoption: A Framework to Accelerate the Transition to Sustainable Mobility. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arefin, A.A.; Meraj, S.T.; Lipu, M.S.H.; Rahman, M.S.; Rahman, T.; Hasan, K.; Sarker, M.R.; Muttaqi, K.M. Societal, environmental, and economic impacts of electric vehicles towards achieving sustainable development goals. Results Eng. 2025, 27, 107060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litman, T. Evaluating Transportation Equity; Victoria Transport Policy Institute: Victoria, BC, Canada, 2025.

- United Nations. Sustainable Urban Mobility and Public Transport in UNECE Capitals; United Nations Economic Commission for Europe: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Sierzchula, W.; Bakker, S.; Maat, K.; Van Wee, B. The influence of financial incentives and other socio-economic factors on electric vehicle adoption. Energy Policy 2014, 68, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]