Abstract

This study focuses on the search for the optimal value of the cost per liter of raw milk. The sample included 59 farms with different types of labor, containing 422 elements maintained in different accommodation conditions. The farms are located in an urban area in the country’s capital. This study was essentially based on mathematical methodology close to a variant of the Cobb–Douglas function used by many economists. This made it possible to find expressions of the relationships linking different parameters involved in the evaluation of the optimal value of the cost per raw liter, as well as certain critical values of the number of elements to be determined. The results show that the variation in the cost per liter follows two levels; the first relates to a number of elements between one and ten, where the increase occurs in a linear and progressive manner. The second level concerns the range between 10 and 30 elements. It is characterized by a linear increase and is more accentuated than in the previous case. The results also suggest that a critical number indicates the separation between the two levels. Application of these wastes as fertilizers aligns with the EU Action Plan on the Circular Economy and can contribute to achieving SDGs 2 and 12.

1. Introduction

The combination of progressive economic development and population growth is intensifying the demand for essential resources like water, food, and energy. As societies aspire to improve living standards, markets respond by expanding the variety and volume of products they produce. This trend underscores the need for sustainable resource management and innovative solutions for profitability, creating more jobs so as to meet the growing needs while minimizing the environmental impact. In Africa, the livestock sector is one of the most dynamic components of the agricultural economy [1]. It represents a significant share of the economies of many countries, averaging 15% of the gross domestic product (GDP), with figures exceeding 40% in some regions [2]. In developing countries, this sector contributes to household income, food security, and nutrition [3]. In Algeria, livestock accounts for over 30% of the agricultural GDP across all types of farming [4], underscoring its vital role within the country’s agricultural sector. The essential contribution of dairy cattle farming is recognized for facilitating the establishment of more intensive and sustainable agricultural practices [5,6,7,8]. As of 2024, Algeria’s dairy herd was estimated at 908.412 head, with nearly 12% comprising modern imported dairy cattle (MDC), which account for 70% of the total cow milk production—approximately 2.5 billion liters annually, translating to a per capita availability of 150 L/year, with 49% sourced locally and the remainder met through powdered milk imports. This consumption level is the highest in the Maghreb region [3]. Additionally, the local dairy sector has generated over 300.000 jobs nationwide, with significant state budget allocations dedicated to livestock development through various agricultural programs, including the rehabilitation program for the dairy sector launched in 1995, the National Agricultural and Rural Development Plan (NARDP) in 2001, NARDP in 2002, and Agricultural Renewal initiatives beginning in 2009. Since then, the local dairy sector has experienced real growth across all its components [9,10,11].

This development is currently falling short of the established objectives, despite a steady increase in consumption fueled by population growth and state support for consumer prices [12]. According to [13], imports of pregnant heifers have significantly risen from an average of 1.671 heads annually between 1964 and 1968 to 29.222 heads during the period from 2005 to 2009. This number surged further to 93.500 heads from 2009 to 2012 and ultimately reached 109.462 heads from 2012 to 2022. In total, over half a million cows were imported from 1964 to 2022; however, this influx has not produced the expected increase in local production.

It is now clear that, despite considerable efforts, dairy farming in Algeria is struggling to progress. This sector contends with numerous constraints related to livestock management, particularly concerning animal feed [5,14,15,16], as well as challenges in reproduction control [17,18] and various external constraints influenced by territorial factors, including climate, agronomic potential, hydraulic infrastructure, and demographic aspects such as urbanization [10,19]. These cows indicate significant dysfunctions within Algeria’s dairy cattle farming and are critical determinants of the cost of producing one liter of milk, which appears inconsistent with prices in other countries [10,20]. To address these production deficiencies, it is essential to identify the multiple factors limiting the efficiency of dairy operations through a purely mathematical study. In this context, Algiers was selected as the study area due to its reputation for intensive dairy farms located on its outskirts, which play a vital role in the production systems of the Mitidja region. However, like many cities worldwide, Algiers has faced significant pressures from urban growth, leading to both a loss of agricultural space and a decline in agricultural coherence. Agriculture is now primarily practiced on the periphery and is increasingly shifting towards peri-urban practices, especially regarding livestock farming [21]. However, efficiency is defined as the result achieved in relation to the resources used to attain it [22]. Moreover, peri-urban agriculture, in its strict etymological sense, refers to agricultural activities situated on the outskirts of a city, irrespective of the type of production system used [23].

This article focuses primarily on examining the situation of dairy cattle farming. For this purpose, a representative sample of 59 diverse farms was taken from the peri-urban area of Algiers, creating opportunities for sustainability, profitability, and new jobs. These farms underwent technical and economic surveys, resulting in a substantial database for analysis through mathematical modeling based on statistical results. The sector is experiencing tangible changes that could force it to contract or even vanish within a shorter time frame if available space continues to diminish [24,25,26,27,28].

This study was essentially supported by the mathematical methodology, which has not been well discussed for the treatment of such an agricultural problem by specialists in this area of our country.

2. Methodological Option and Statistical Modeling Study

2.1. Study Area

We propose some forms of production functions, widely used by specialists, which are proposed to express the quantitative relationship between the volume of production and the factors of production, such as the Cobb–Douglas Production Function (CD), which is one of the most widely used functions in practice. The American economist P.H. Douglas and the American mathematician Charles Cobb developed it in 1928. It expresses the relationship between labor and capital. The production function (CES) is a non-linear homogeneous function. In 1961, the economists Chemery, Solow, Minha, and Arrow proposed this function by improving the CD function. The other functions include the Revankar function, proposed in 1971, the Transcendental function, proposed by Hater in 1957, and the Translog function. The function used in agricultural production is of the type:

The function f expresses the relationship between the proportionality between the quantity of production and the quantity of the production parameters. It can take forms or exponential functions, such as the Cobb–Douglas function CD. Despite the very wide use of the DC production function, it is not the only one used by economists in the analysis and measurement of agricultural production. The other functions include the Wicksell function, which was proposed in 1961. In this study, we opted for a mathematical approach equivalent to that used to express agricultural production, which is an improved variant of the Cobb–Douglas function.

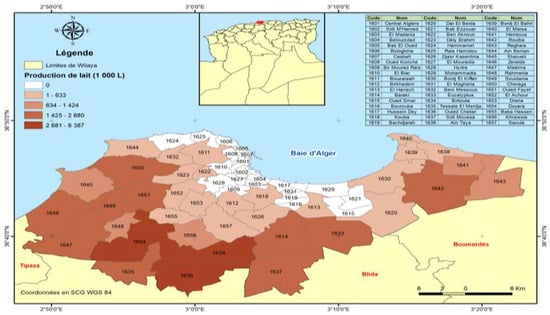

The objective of this study was to develop a mathematical model that can link the various parameters involved in the mathematical laws derived, which technical managers in this field may find beneficial for creating new jobs and supporting sustainability and opportunities for the circular economy. This research was conducted among 59 dairy cattle farmers situated around the city of Algiers, specifically in five municipalities, including Ouled Chebel, Birtouta, Tassala El Merdja, and Douira, from 2023 to 2024, as part of doctoral research (Figure 1). This region has been the focus of an extensive development program aimed at increasing raw milk production since the early 2000s, specifically from 2001 to the present. The farms included in this study were selected using a non-probability sampling method, specifically through convenience sampling. This approach involved choosing the most accessible and available participants. The majority of these farms specialize in dairy cattle farming, which significantly contributes to overall income through the revenue generated from milk production. These farms primarily raise cows, particularly specialized imported dairy breeds, such as Holstein and Montbéliarde, as well as locally crossbred cows. Local breed cows are nearly nonexistent.

Figure 1.

(Map 1) Distribution of dairy production potential in Algiers Province. Source: Agricultural Services Directorate (DSA) of Algiers, 2024.

A preliminary survey phase was conducted to assess the clarity and relevance of the questions prior to the actual survey phase. This initial assessment facilitated the design of the final questionnaire (Supplementary Materials) utilized during fieldwork, which addressed both the technical and socio-economic characteristics of the farms and their environments. Each farm underwent at least three evaluations: the first in the autumn, another at the beginning of spring when feed is abundant, and a third in mid-summer, which is considered the lean season.

Once the database was established for the data analysis, the data were classified to facilitate economic calculations, which enabled the determination of production costs for each farmer and an assessment of their profitability. This information enhanced our database for subsequent mathematical and statistical analyses.

The procedure began with assigning a registration number to each farm. In this initial phase, the farm’s registration number was defined as follows:

MAT: 21316P001

Where

- 213 is the international code assigned to Algeria;

- 016 is the code for Algiers Province, where the farms are located;

- P indicates the type of operator, with ‘P’ denoting personal, ‘F’ denoting family-owned, and ‘E’ denoting external;

- 001 indicates the rank of the operator within the specified type.

The table references the existence of 18P, 32F, and 09E.

The data collected in the field, as indicated in Table 1, cannot be directly utilized due to significant discrepancies in values for the same parameter; thus, we opted to work with averaged values for the cases studied.

Table 1.

Statistical data of farms.

The key variables were identified based on their influence on the parameters involved in the production chains, established from the samples taken during this study.

The mathematical modeling method unfolded as follows:

- The data are treated as mathematical functions of a single variable.

- A smoothing process is applied to the function to determine its shape across each interval of the chosen variable.

- Subsequently, a mathematical function that closely resembles the smoothed version is proposed.

- Using the smoothed curve data, certain data points deemed less realistic are corrected, allowing us to derive mathematical expressions that reflect the variations in the evolution curve of the studied parameters. In Table 2, in order to enhance the readability of the collected data, the following nomenclature is presented.

Table 2. Nomenclature used to examine the case study.

Table 2. Nomenclature used to examine the case study. - The environmental management of farms considered in this study has not been the subject of mathematical modeling due to the current lack of certain data on the environmental aspect. It should be noted that the operations studied are managed by modest means and equipment. Regarding the supply of water and energy, the public authorities contribute financial aid to encourage operators to switch to green energy. In a future study, we will aim to present the environmental aspect of the exploitation of dairy cattle farms in Algeria.

- We are concerned with the efficiency of dairy cattle breeding activity. It should be noted that multiple factors determine this efficiency, in particular, the use of technology in dairy cattle breeding activity. On these farms, we recorded an average yield of 17 L/VL/Day (liters per dairy cow per day), close to that of the Maghreb countries, which is 20 L/VL/Day, but far from the milk yields recorded on European farms, which exceed 40 L/VL/Day [25]. On the other hand, the economic results observed show economic performance that can hardly be said to be weak. The production cost shows an archaic level of technical mastery; it depends on explanatory variables, such as food, which remains the most important item, with 56.89% of the total cost and 18.49%% of the labor costs. All these results explain the inefficiency of these dairy farms.

2.2. Statistical and Modeling Approach

This study applied the neoclassical production theory to assess the relationships between inputs, production costs, and milk output in peri-urban dairy farms. Total production costs were calculated following FAO (2017) standards, including fixed costs (infrastructure, depreciation, taxes) and variable costs (feed, labor, veterinary care, utilities). The costs were standardized per liter of milk.

2.2.1. Production Function Modeling

To analyze the determinants of milk output and identify scale effects, we employed a modified Cobb–Douglas production function. The explicit form used was:

where

Q = AKαLβFγ

- Q = milk production;

- K = capital (equipment and infrastructure);

- L = labor input;

- F = feed input;

- A, α, β, and γ = parameters;

The model was estimated using the log-linear transformation:

ln(Q) = ln(A) + αln(K) + βln(L) + γln(F) + ε

Parameter estimation was performed using ordinary least squares (OLS). Coefficient significance was evaluated through t-tests, and model fit was assessed using R2, standard errors, and residual diagnostics. The Cobb–Douglas form was selected due to its widespread use in agricultural production modeling and its ability to capture scale elasticity efficiently.

2.2.2. Cost Curve Modeling

Empirical cost functions were derived by fitting polynomial models to observed production costs across different herd sizes. This curve-fitting approach allowed the identification of the following:

- A critical herd size Nc;

- Cost asymptotes, such as the optimal cost level Cop;

- Profitability thresholds across size categories.

Model selection was based on least-square error minimization and graphical inspection of fit quality.

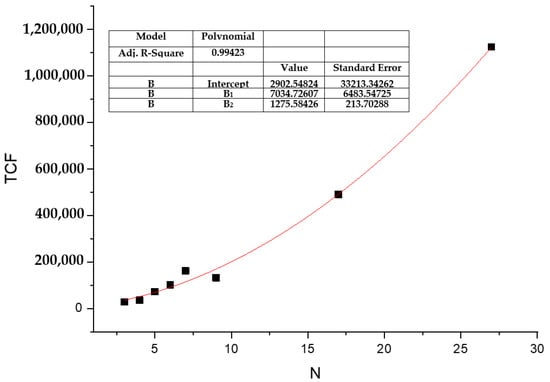

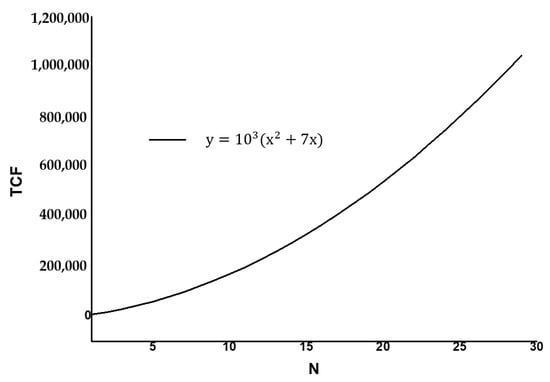

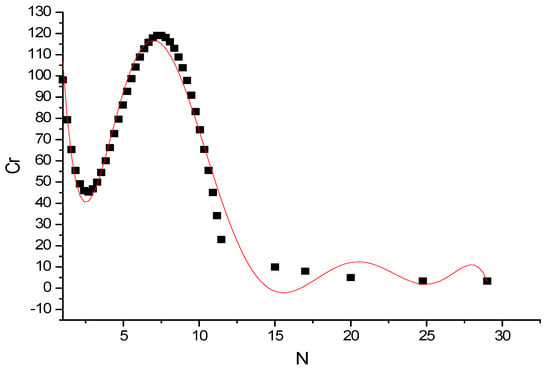

The mathematical treatment of the different parameters characterizing the production of raw milk by dairy cows was performed using a mathematical modeling method according to the following steps: First step: The real values of the data were entered. Second step: The mathematical curve was traced, indicating the variation in the parameter studied represented in type graphs. Third step: A mathematical correction was applied in order to find a mathematical expression in polynomial form, represented in type graphs. Figure 2 shows the curve indicating the variation in the cost price per liter of raw milk, including all charges, depending on the number of elements processed. We see that the shape of this curve can be divided into two zones; the first zone concerns a group bringing together between one and ten cows. This set is characterized by a cost price, which increases almost linearly and progressively, depending on the number of elements processed. The second zone, concerning the second set, brings together between ten and thirty cows. We see that the variation in the cost price also increases linearly, but in a more pronounced manner than in the previous case. The mathematical modeling of the variation in the cost price per liter of raw milk, including all charges, as a function of the number of elements processed, is presented in Figure 3. We notice the existence of a critical number that indicates the separation between the two zones. The intersection of the two curves is then made at this point, for a critical value corresponding to . Figure 4 indicates a proposal for a law of variation in the TCF function as a function of the number of cows, according to the following expression:

Figure 2.

Variation in total production costs as a function of the number of cows (N).

Figure 3.

Model depicting the variation in total production costs based on the number of cows (N).

Figure 4.

Variation in the total cost function (TCF) in relation to the number of cows (N).

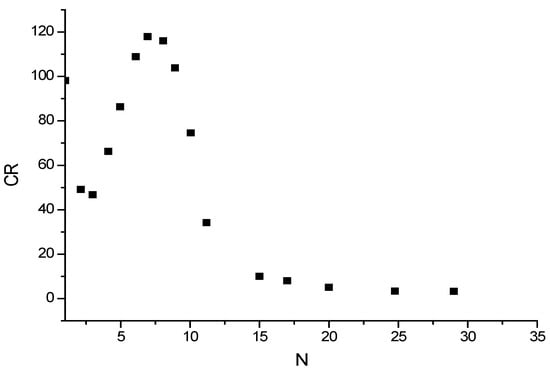

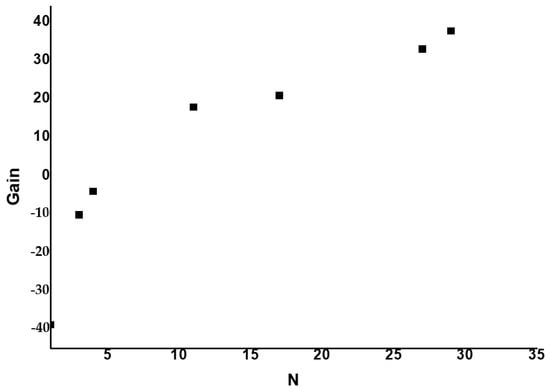

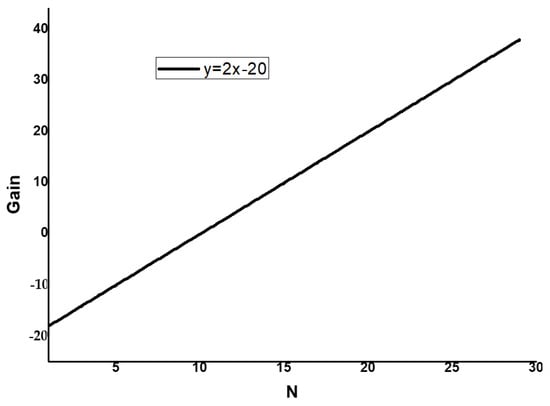

Figure 5 shows the variation in the cost of raw milk production depending on the number of cows treated. We see that its appearance can be divided into three zones; the first zone concerns a group of one to four cows. For this set, we notice that the cost price is very high for a single element processed; it then falls following an inverse law, that is to say that the cost price is inversely proportional to the number of cows. The second zone relates to a group of four to eight cows. In this area, the cost price follows an almost linear increase to reach approximately the same values as in the previous case. The third zone concerns a set that brings together between eight and thirty elements. In this zone, the cost price decreases following a law inverse to the number of cows. The decrease in the curve reaches an asymptotic limit value; this is the optimal value , see Figure 6. Figure 7 shows a curve indicating the variation in the profitability of the cost price of raw milk production as a function of the number of cows treated. We see that it can be divided into three zones; the first zone concerns a group of one to six cows. For this set, we notice that the profitability has negative values , for . The second zone concerns a set that brings together six to twelve elements. In this zone, the profitability is positive; it follows an almost linear increase to reach values that tend to keep constant values , for a level of values of the number of elements satisfying the following inequality: . The third zone concerns a group of twenty to thirty cows. In this zone, the cost price relative to the gain increases following a linear law for . See Figure 8. Figure 9 indicates the profitability corrected for the cost price of raw milk production represented by the variable y as a function of the number of cows treated, represented by the variable x according to the following expression:

Figure 5.

Variation in production costs as a function of the number of cows (N).

Figure 6.

Curve modeling the variation in production costs as a function of the number of cows (N).

Figure 7.

Variation in profit as a function of the number of cows (N).

Figure 8.

Curve representing the variation in profit as a function of the number of cows (N).

Figure 9.

Adjusted curve modeling profit variation as a function of the number of cows (N).

3. Results

Farms and Production Cost

The results in Table 3 and Table 4 show how production costs vary both by farming type and by herd size. Differences between farming systems suggest that management practices and resource use strongly influence overall expenses, while the cost patterns linked to herd size indicate where economies of scale may occur or where additional cows begin to generate higher marginal costs. Together, these findings highlight the importance of choosing an appropriate production system and herd level to maintain cost efficiency.

Table 3.

Data on production costs by type of farming.

Table 4.

Data on production costs by the number of cows.

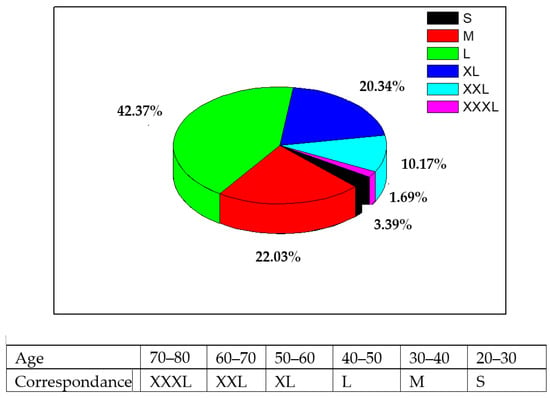

Figure 10 depicts the distribution according to the type of farming. It is noteworthy that family-operated farms are the most prevalent, followed closely by individual farms. Despite this significant representation, it is important to emphasize that their profitability remains low. This observation should motivate stakeholders to explore more profitable management strategies. We believe that this management style should evolve towards some form of consolidation among farms situated in close proximity, which would facilitate shared management of forage cultivation and agricultural equipment. Additionally, experiences from France have illustrated that the yields achieved through modernization efforts have led to reduced production costs, making dairy farming more profitable. The modernization process has been a crucial factor behind the increased profitability of French dairy farms [25].

Figure 10.

Distribution by type of farming.

Figure 11 presents the distribution based on the age of the farmer. It is evident that the predominant age group includes those aged 20–40, closely followed by those aged 40–60, who comprise nearly half of the younger group. These data indicate that the aging workforce in dairy farming is becoming increasingly apparent. To tackle this challenge, public authorities must explore ways to enhance the attractiveness of this profession through vocational training and improved access to technical equipment.

Figure 11.

Distribution by age of the farmer.

Although this study is mainly devoted to milk production in Algeria, we thought that providing information related to milk production in the countries of the Maghreb and the sub-Saharan zone would provide the elements necessary to conduct a comparative study. The various statistics come from local official sources and international organizations. Sixteen African countries located in West Africa were considered as a group in this analysis. Figure 12 shows a graph of current milk consumption for the three countries of the Maghreb and sub-Saharan Africa. We note that Algeria consumes almost the same quantity as that of Morocco and sub-Saharan Africa combined. Tunisia has a lower consumption than Algeria and a higher consumption than the other countries cited.

Figure 12.

Actual consumption in Maghreb and sub-Saharan Africa.

Figure 13 shows the current milk consumption in percentage for the three countries of the Maghreb and sub-Saharan Africa. We note that Algeria consumes almost 37% of the global consumption. Tunisia has a consumption of 29%, Morocco has 22%, and sub-Saharan Africa has 11%.

Figure 13.

Actual consumption in percentage in Maghreb and sub-Saharan Africa.

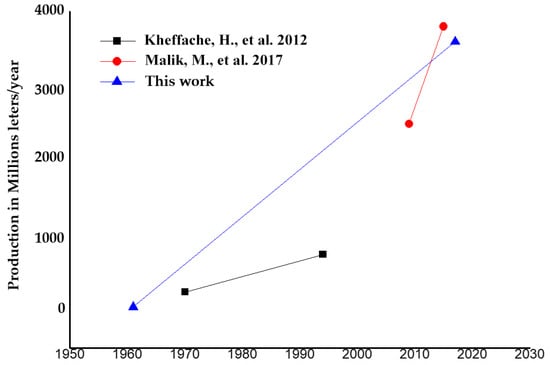

Figure 14 shows milk production per liter and per capita from the year 1960 to the year 2025, as obtained from three authors. Ref. [13] covers the period 1970–1995, and [29] covers the period 2010–2024. This study covers the period 1960–2025. We note that the linear curves proposed by the mathematical approach used in this study present a certain similarity, despite the existence of differences in the growth rate between the three curves.

Figure 14.

Comparative linear curves produced by different authors [13,29].

4. Summary and Conclusions

This study set out to construct a mathematical model that links the main factors influencing dairy farm management in the peri-urban zone of Algiers. The analysis revealed that production costs evolve in well-defined stages. Two major cost zones were identified, separated by a critical herd size of Nc = 12 cows. Costs are especially high at very small scales and then decline sharply as herd size increases, following an inverse relationship. This reduction gradually approaches an optimal cost level, Cop. A third zone, corresponding to herds of 8 to 30 cows, showed a similar inverse pattern, with costs stabilizing around Cop before rising slightly at the upper end of this range.

Profitability followed a comparable structure. Farms with fewer than six cows showed negative returns. Profitability became positive from about six to twelve cows and increased until it reached a relatively stable range between ten and twenty cows. Beyond twenty cows, profitability showed another upward tendency. Taken together, these results highlight the strong influence of herd size on both economic efficiency and the capacity of farms to remain viable.

The diversity of the farms studied—reflected in their herd sizes, housing conditions, investment levels, labor availability, and land resources—explains the notable variation in performance within the sample. Despite this heterogeneity, the overall trend is clear: farms operating with too few cows face structural difficulties, whereas those approaching medium scale achieve more stable costs and better margins. Modernizing production methods, improving infrastructure, and adopting digital monitoring tools would help producers benefit more fully from these scale effects.

From an environmental standpoint, the results underline the importance of supporting farmers in adopting more efficient and cleaner technologies. Existing public incentives promoting renewable energy and environmentally responsible practices represent an essential step in this direction. Beyond the empirical findings, this study also demonstrates the usefulness of mathematical and statistical modeling—here based on an enhanced form of the Cobb–Douglas framework—in analyzing dairy production systems. This type of approach remains uncommon in national agricultural research, yet it provides valuable insights for identifying cost thresholds, optimal herd sizes, and key relationships between production variables.

Finally, although this work focuses on small and medium farms typical of the peri-urban context, the methodology can be extended to larger industrial farms, which are becoming more prominent in the region and internationally. Future research will broaden the comparison to national and regional dairy systems in order to better situate the challenges and opportunities facing the Algerian milk sector.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su172410912/s1, File S1: For Participants—Farmer Questionnaire.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.G., B.B.H. and K.K.; data curation, M.G. and B.B.H.; formal analysis, M.G., B.B.H. and K.K.; funding acquisition, M.G.; investigation, M.G., B.B.H. and K.K.; methodology, M.G.; resources, M.G.; supervision, M.G., B.B.H., K.K., T.K. and F.M.-O.; validation, M.G., B.B.H. and K.K.; visualization, M.G., B.B.H., K.K., P.S., T.K. and F.M.-O.; writing—original draft, M.G., B.B.H., K.K., P.S., T.K. and F.M.-O.; writing—review and editing, M.G., B.B.H., K.K., P.S., T.K. and F.M.-O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The resources for this research were funded by the Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research of Algeria.

Institutional Review Board Statement

We obtained approval from the Ethics and Deontology Committee of the National Superior School of Agronomy (ENSA).

Informed Consent Statement

We provided a separate blank version of the informed consent form to ensure full compliance with ethical standards.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in this article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of this study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Richard, D.; Alary, V.; Corniaux, C.; Duteurtre, G.; Lhoste, P. Dynamics of Pastoral and Agro-Pastoral Livestock in Intertropical Africa; Quæ, CTA, Presses Agron: Gembloux, Belgium, 2019; Presses agronomiques de Gembloux, Passage des Déportés, 2, B-5030 Gembloux, Belgique; Available online: https://directory.doabooks.org/handle/20.500.12854/81377?locale-attribute=en (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Vall, E.; Salgado, P.; Corniaux, C.; Blanchard, M.; Dutilly, C.; Alary, V. Changes and Innovations in Livestock Systems in Africa. In Quelles Innovations pour Quels Systèmes d’Élevage? Ingrand, S., Baumont, R., Eds.; INRAE Productions Animales: Paris, France, 2014; Volume 27, pp. 161–174. Available online: https://productions-animales.org/issue/view/356 (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Sraïri, M.T.; Chatellier, V.; Corniaux, C.; Faye, B.; Aubron, C.; Hostiou, N.; Safa, A.; Bouhallab, S.; Lortal, S. Dairy Sector Development and Sustainability Worldwide. INRA Prod. Anim. 2019, 32, 339–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MADR. Dairy Sector Note; Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development: Algiers, Algeria, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrah, A. Dairy Cattle Farming in Algeria: Issues, Questions, and Research Hypotheses. In Proceedings of the 3rd JRPA Conduite et Performances d’Élevage, Tizi-Ouzou, Algeria, 25–27 April 2000; pp. 40–47. [Google Scholar]

- Kaouche, S. Dairy Sector in Algeria: Current Status and Key Development Constraints. Ciheam Watch Lett. 2015, 35, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Kerbache, I.; Tennah, S.; Kafidi, N. Socio-Economic Study of Cattle Farming in Eastern Algeria. Rev. Econ. Pap. 2019, 3, 208–234. [Google Scholar]

- Mamine, F.; Fares, M.; Duteurtre, G.; Madani, T. Regulation of the Dairy Sector in Algeria Between Food Security and Local Production Development. Rev. Elev. Med. Vet. Pays Trop. 2021, 74, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bencharif, A. Strategies of Dairy Sector Actors in Algeria. Options Méditerranéennes Ser. B 2001, 32, 25–45. [Google Scholar]

- Djermoun, A.; Ramdane, S.; Mahmoud, B. Dairy Farms in Cheliff, Algeria, in the Era of Economic Liberalization. Rev. Agrobiol. 2017, 7, 658–668. [Google Scholar]

- Kacimi, S. Food Dependence in Algeria: Milk Powder Imports vs. Local Production. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2013, 4, 152–158. [Google Scholar]

- Abdelli, R.; Sadia, Y.; Kaouche, S.; Benhacine, R. Current Status of the Dairy Sector in Algeria and Development Perspectives. Algerian J. Arid Environ. 2021, 11, 4–14. [Google Scholar]

- Kheffache, H.; Bedrani, S. Subsidized Heifer Imports with High Dairy Potential: Failure Due to Lack of Comprehensive Dairy Policy. Les Cah. Du CREAD 2012, 28, 101. Available online: https://asjp.cerist.dz/en/article/2048 (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Hoummani, M. Food Situation of Livestock in Algeria. Rech. Agron. 1999, 4, 35–45. [Google Scholar]

- Issolah, R. Forages in Algeria: Situation and Development Perspectives. Agron. Res. 2008, 12, 34–47. [Google Scholar]

- Yozmane, R.; Mebirouk-Boudechiche, L.; Chaker-Houd, K.; Abdelmadjid, S. Typology of Dairy Cattle Farms in Souk-Ahras, Algeria. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 2019, 99, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Belhadia, M.A.; Yakhlef, H. Dairy Production and Reproduction Performance of Cattle Farms in the Semi-Arid Zone: Haut Cheliff Plains, Northern Algeria. Livest. Res. Rural Dev. 2013, 25, 41–50. [Google Scholar]

- Ghozlane, F.; Yakhlef, H.; Yaici, S. Reproduction and Dairy Production Performance of Cattle in Algeria. Ann. Inst. Natl. Agron. 2003, 24, 55–68. [Google Scholar]

- Tayeb, H.S.; Mouhous, A.; Cherfaoui, L.M. Characterization of Dairy Cattle Farming in Algeria: Case of Fréha, Tizi-Ouzou. Livest. Res. Rural Dev. 2015, 27, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Bellil, K.; Boukrif, M. Comparative Analysis of Economic Profitability of Different Dairy Farming Systems in Bejaia. Revue Agric. 2015, 10, 59–66. [Google Scholar]

- Ikhlef, S.; Ikhlef, L.; Brabez, F.; Far, Z. Short-Term Sustainability Evolution of Dairy Cattle Farms in the Peri-Urban Zone of Algiers. Livest. Res. Rural Dev. 2017, 29, 61. Available online: http://www.lrrd.org/lrrd29/4/farz29061.html (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Zambrowski, J.-J. In Search of Efficiency. Actual. Pharm. 2021, 60, 27–28. [Google Scholar]

- Fleury, A.; Donadieu, P. From Peri-Urban Agriculture to Urban Agriculture. Courr. Environ. INRA 1997, 31, 45–61. [Google Scholar]

- Boudjenouia, A.; Fleury, A.; Tacherift, A. Peri-Urban Agriculture in Sétif (Algeria): Future Challenges Facing Urban Growth. Biotechnol. Agron. Soc. Environ. 2008, 12, 23–30. [Google Scholar]

- Chatellier, V.; Dupraz, P. Economic Performance of European Livestock: From “Cost Competitiveness” to “Non-Cost Competitiveness. INRA Prod. Anim. 2019, 32, 171–188. [Google Scholar]

- Djermoun, A.; Chehat, F. The Development of the Dairy Industry in Algeria: From Self-Sufficiency to Dependence. Livest. Res. Rural Dev. 2012, 24, 1. Available online: https://www.lrrd.cipav.org.co/lrrd24/1/cont2401.htm (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Djermoun, A.; Benziouche, S. Exogenous and Endogenous Constraints of Dairy Production in Algeria: A Case Study from Cheliff. Rev. Des Bio Ressour. 2017, 16, 12–27. [Google Scholar]

- Ouedraogo, S.; Sodré, E.; Savadogo, K.I.; Sanou, L.; Bougouma, V.M.C. Dairy Production Performance of Peri-Urban and Urban Farms in Fada N’Gourma, Burkina Faso. Rev. Mar. Sci. Agron. Vét. 2023, 11, 351–359. [Google Scholar]

- Malik, M.; Montaigne, E. Impact of New Algerian Dairy Policy on Farm Viability. New Medit. 2017, 16, 2–10. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).