Abstract

This study compares how academics and company managers prioritize environmental sustainability criteria using the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP). Three main criteria were evaluated: resource and waste management, energy management, and product sustainability. The study examines these priorities by identifying key sustainability criteria, comparing stakeholder assessments, and interpreting their implications for SDG-focused decision-making processes. The findings, based on the hypothesis that managers prefer market-sensitive strategies while academics prioritize ecological management, show that these different perspectives are complementary and can contribute to more inclusive sustainability policies together. The results show that company managers place greater importance on product-related practices such as the use of recycled materials, supply chain control, and product certification, reflecting market-oriented sustainability expectations. On the other hand, academics place greater emphasis on resource and waste management, including water resource protection (SDG 6), solid waste management (SDG 15), and the use of recycled materials (SDG 12). Both groups emphasize renewable energy (SDG 7) and greenhouse gas reduction (SDG 13) in the energy dimension.

1. Introduction

Global environmental degradation, depletion of natural resources, and the extraordinary increase in the effects of climate change have made sustainable development not just an option but a necessity. International strategies targeting 2050 (the Paris Agreement, the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, etc.) require both public and private sector actors to develop environmental sustainability practices. In this context, understanding the priorities of businesses and academics regarding environmental sustainability is critical for both theoretical contributions and practical applications. Current statistics in the field of environmental efficiency also support this necessity. For example, approximately 350 million tons of plastic waste are produced worldwide each year, and only a small portion of it can be recycled [1]. Although the production of recyclable plastic has increased significantly since 2020, only about 9.5% of the plastic produced in 2022 was made from recycled material [2]. This situation demonstrates how urgent it is to transition to recyclable materials in the management of packaging waste. In Turkey specifically, regulations under the European Green Deal have imposed new obligations on the country regarding the use of sustainable energy sources, greenhouse gas prevention costs, and energy efficiency.

According to the Climate Change Performance Index (CCPI) 2022 report, Turkey ranks at an intermediate level globally in terms of indicators such as greenhouse gas emissions, renewable energy use, and energy consumption; however, it has been criticized for its current practices not being aligned with the 1.5 °C target [3]. In this context, the country faces the need to improve its sustainability practices in terms of both regulatory pressures and global market dynamics.

Businesses should be aware of the social, economic, and ecological environment, particularly the constraints encountered within this environment, at least for strategic reasons [4]. Hart’s (1995) “natural resource-based approach” argues that environmental sustainability may generate economic and competitive benefits for companies, beyond being merely a social or ethical obligation [5]. This approach is shaped around pollution prevention, product stewardship, and sustainable development strategies. Studies such as Hart & Dowell (2011) detail these strategies in the context of various sectors, different environmental pressures, and factors that provide competitive advantage, revealing how environmental sustainability may be linked to corporate performance [6].

Organizations that integrate ISO 14001 [7] requirements into their daily practices and have employees who are sensible in this regard perform better in solving environmental problems, but they are unable to reflect this in their business performance and financial metrics [8]. Despite the importance given to the environmental dimension of sustainability, operational practices in the field are shaped primarily within the framework of the sub-criteria of the social and economic dimension, such as business development and the support of talented individuals [9]. Studies in the field indicate that Scandinavian countries are ranked ahead of Europe and the Middle East in terms of sustainability due to their high levels of financial and social support [10].

The purpose of this study is to determine which criteria company managers and academics prioritize among environmental sustainability criteria using the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) method; specifically, to compare perception differences in the dimensions of product sustainability, energy management, and resource–waste management. Academics particularly focusing on issues such as water resource conservation and solid waste management, while companies concentrate on practices like product certification, supply chain auditing, and the use of recyclable materials, demonstrates how sustainability policies can be integrated with individual and corporate strategies in terms of both environmental and economic performance. This study is based on the environmental dimensions of the 17 sustainable development goals set by the United Nations in 2015 in line with its objectives. The results of the research, which show the level of importance attributed to the implementation of these goals by academics and company managers, aim to benefit both the literature and practitioners in companies. Focusing on the “17 Sustainable Development Goals of the United Nations” increases the importance of the contributions currently provided to various parties.

This study provides an important reference point for policies aimed at strengthening environmental sustainability [11]. It also raises awareness of how environmental practices can shape firms’ competitive advantage and affect compliance costs [12]. Furthermore, the study contributes to the resource-based view by emphasizing how environmental competencies form a foundation for long-term competitive advantage [5]. Making the differences in priorities between companies and academics visible provides concrete guidance to managers and policymakers on aligning sustainability strategies with stakeholder expectations. Empirical evidence shows that ecological packaging, particularly the use of recyclable and environmentally friendly materials, positively affects consumers’ perceptions of brand image and perceived product quality, even when a potential price difference is expected [13]. Quantifying the relationship between Hart’s natural resource-based approach and sustainability criteria using the AHP method provides new data to the literature on how these strategies are prioritized by different stakeholder groups. Given the pressure of current climate and environmental regulations, changing consumer expectations, and international pressures such as the EU Green Deal, the prioritization of environmental criteria by companies and academics indicates that we are at a critical juncture in terms of corporate sustainability governance. Therefore, this research contributes to understanding environmental sustainability priorities both in the Turkish context; it also sheds light on the orientations of sustainability practices in terms of both theory and practice. Recent developments in recycling and packaging waste in Turkey clearly demonstrate the challenges and opportunities the country faces in terms of environmental sustainability. Under the Zero Waste Project, the recycling rate of municipal waste rose to 34.92% in 2023, and the target is to increase this rate to 60% by 2035 [14]. At the same time, the overall waste recovery rate has reached approximately 35% [15].

Understanding how academic and firm executives differ in their sustainability priorities is crucial for bridging the well-documented ‘science-practice gap’ in environmental governance. Research shows that the misalignment between scientific recommendations and managerial decision-making processes often leads to inconsistent certification decisions, fragmented implementation, and insufficient environmental investment [16]. Also, some studies in the literature highlight that firms generally prioritize criteria driven by operational limitations and market pressures, while the research community focuses on long-term ecological risk and systemic sustainability outcomes [17,18]. These structurally different incentive frameworks can lead to differences in procurement practices, reporting standards, and policy adoption. Therefore, comparing these two stakeholder groups provides a meaningful analytical basis for identifying potential implementation gaps and strengthening the design of sustainability policies focused on the Sustainable Development Goals.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows: Section 2 reviews the literature on environmental sustainability, stakeholder-specific priorities, and multi-criteria decision-making. This is followed by Section 3 explaining the AHP model and expert sampling. Section 4 presents the results, followed by Section 5 that includes limitations and implications. Section 6 summarizes the findings based on the research results.

2. Theoretical Background

Hart (1995) expanded the resource-based approach, emphasizing the role of environmental factors in creating competitive advantage and arguing that companies may gain strategic superiority through their relationships with the natural environment [5]. This theory, referred to as the “natural resource-based approach,” is built on three fundamental strategic axes: pollution prevention, product stewardship, and sustainable development [5]. Subsequent studies have examined these three strategies in greater detail based on Hart’s model and enriched them with different dimensions. For example, Hart and Dowell (2011) developed a natural resource-based approach and discussed how these strategies are shaped in the context of different resource types, environmental pressures, and elements that provide competitive advantage [6]. In this context:

The pollution prevention strategy focuses on preventing waste and emissions from being generated during the production process rather than disposing of them after they have been created. This approach provides both cost savings and operational efficiency by simplifying production processes, reducing input usage, and lowering legal compliance costs.

Product stewardship aims to integrate environmental responsibility into product design, development, and marketing processes, covering the entire product life cycle and value chain. This strategy increases the participation of external stakeholders and provides companies with a competitive advantage through access to specific resources and compliance with international standards.

Sustainable development aims not only to minimize damage to the environment but also to develop production models that are sustainable in the long term. This strategy, which encompasses not only environmental aspects but also economic and social dimensions, requires the adoption of clean technologies, the creation of new markets targeting low-income segments, and the utilization of dynamic talents.

2.1. The Importance of Environmental Sustainability

Before the concept of ecology emerged in 1866, the idea of the economy of nature began to take shape in the 1700s. However, the concept of sustainability emerged in the late 1970s, and various publications in the 1980s addressed this concept and its dimensions in detail. Despite some opposing views, it gained importance in the policy arena in the 1990s [19]. Sustainability is defined as “meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” [20]. In this context, sustainability is described as consisting of the interrelated economic, environmental, and social dimensions [21,22,23,24,25,26]. The environmental dimension of sustainability came to the fore particularly with Rachel Carson’s 1962 work Silent Spring, which is considered one of the turning points in environmentalism [27]. In addition, the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) held in 1992 gave sustainability a global dimension, and the 27-article Rio Declaration published as a result of the conference laid the foundations for environmental sustainability, particularly at the international level [28]. In 2015, the United Nations’ 17 Sustainable Development Goals aim to establish concrete targets under current conditions, bringing together governments, the private sector, and academia on common ground [29]. When evaluating the impact of these goals on the national economy, it was found that low-cost clean energy (SDG7) and climate action (SDG13) have a negative relationship with economic growth, while protecting terrestrial ecosystems, sustainable cities, and responsible production and consumption (SDG11, 12, 15) support economic growth [30].

Organizations’ approach to sustainability can be evaluated gradually; as understanding of the relationship between the company and its stakeholders deepens, it becomes possible to transition from practices aimed at legal compliance to practices that target value maximization in all three contexts: economic, social, and environmental [4]. In addition to documenting their performance in this area by publishing sustainability reports, organizations gain the trust of their stakeholders through the principle of accountability [4,31]. Similarly, organizations that incorporate eco-friendly innovations into their products can gain a competitive advantage through differentiation strategies [32]. Most organizations manage environmental risks by integrating environmental thinking into their strategies, gaining an advantage in terms of public relations and market protection, thereby gaining a competitive advantage [33]. However, the concept of sustainability, which involves ethical responsibility, ensures the security of future life by redesigning production and consumption within the framework of environmentalism [34].

Recent studies in the field of sustainability show that AHP, TOPSIS, and hybrid approaches are becoming increasingly critical in the evaluation of multi-dimensional decisions. For example, ref. [35] uses the AHP–TOPSIS method together to analyze the factors hindering the adoption of sustainable energy technologies in the construction sector and to list the strategies that eliminate these obstacles. Similarly, ref. [36], in their study on converting construction waste into concrete blocks, used the AHP and TOPSIS methods to rank the barriers and strategies facing the circular economy in developing countries, thus presenting that appropriate strategies can create both environmental and economic value. This finding explains why product-focused sustainability practices are becoming increasingly important for firms.

At the corporate level, sustainability is closely linked not only to technical or environmental processes but also to managerial qualities and financial tools. Ref. [37] examines the impact of senior managers’ legal expertise on corporate innovation, revealing how decisive managers’ knowledge profiles can be in shaping sustainability strategies. Ref. [38] proposes an SDG-aligned decision support framework for prioritizing renewable energy, demonstrating why multi-criteria approaches are indispensable in energy planning. From a financial perspective, ref. [39] reveals that green credit practices can support the real economy in terms of both economic scale and efficiency, demonstrating how green finance integrates with sustainable growth policies.

Within an expand stakeholder framework, ref. [40] demonstrates how external stakeholder pressure shapes firms’ environmental applications, showing that institutional investors’ ESG activism can enhance green supply chain performance, particularly in sectors with high digital competence levels. Finally, ref. [41] shows that human resource management practices are based not on a single ideal model but on context-sensitive combinations, reminding us that sustainability policies can be implemented in different ways depending on the sector, organizational culture, and managerial capacity. When considered collectively, these studies clearly demonstrate the necessity of understanding the priorities of different stakeholder groups and employing multi-criteria decision-making approaches when evaluating environmental sustainability criteria.

This study focuses on the environmental sustainability dimension within the broader scope of sustainability. In this context, the main criteria were determined by classifying environmental sustainability practices in line with the relevant literature. Environmental sustainability practices were classified using three main criteria: resource and waste management, energy management, and product sustainability [42].

2.1.1. Resource and Waste Management

Resource and waste management, which holds an important place in terms of environmental sustainability policies, is not only an environmental necessity but also stands out as one of the social responsibilities of organizations [42,43]. In the literature, the protection of water resources, the control of noise pollution, the development of waste management practices, and the acquisition of national and international certifications related to resource use are among the important sub-criteria for sustainable resource management [7,44]. When evaluated using surveys and expert opinions from the perspective of healthcare facility management, factors such as medical waste management, operational management issues, and training are seen as priorities [45]. To protect the water resources, IMO suggests advanced infrastructures, renewable energies and low carbon-emissions fuels [46]. As an important water resource, the protection of marine ecosystems from pollution, illegal fishing, and smuggling is a critical policy priority with significant implications for both the economy and the environmental sustainability [47]. By considering both technical and economic as well as social and environmental dimensions, the evaluation of macro issues arising from the use of electronic devices using AHP reveals that recycling is one of the most suitable alternatives [48].

In this study, four sub-criteria were determined under the main criterion of resource and waste management. These include solid waste management, obtaining certification and standards for resource use, reducing noise pollution, and protecting water resources. The aforementioned sub-criteria have been prioritized as key assessment areas to both enhance businesses’ environmental performance and contribute to sustainable development goals such as clean water and sanitation (SDG 6), responsible production and consumption (SDG 12), and life on land (SDG 15) [29].

2.1.2. Energy Management

Given the increasing demand for energy and the environmental impacts of fossil fuels, it can be said that reducing energy consumption, shifting towards renewable energy sources, and lowering the carbon footprint are fundamental components of sustainable development [49,50]. These fundamental components are of great importance not only for environmental protection but also for the efficient use of resources and economic sustainability [43]. In this context, energy management systems such as ISO 50001 [51], which promote the continuous improvement of energy efficiency, are gaining importance [50]. In the context of creating ecological value, companies such as Shell, BP, and Suncor, whose core activities are based on fossil fuels, require new technologies and organizational capabilities despite incorporating renewable energy sources into their discourse and business portfolios [4]. Within the framework of energy management, there are many applications with different levels of importance. The results of a study conducted in Malaysia using the AHP method show that solar and biomass energy are particularly prominent compared to hydroelectric and wind energy, especially from an economic and social perspective [52]. To transition away from high carbon-emission fuels, the policies should include the use of natural gas resources, natural gas-powered vehicles, taxes for carbon-emissions and incentives for clean energy resources [53]. The solar energy sector in seven different European countries was examined using the AHP method, and the results were found to be consistent with the development levels of these countries during the 2000–2017 period [54].

In this study, the following sub-criteria of energy management were evaluated: energy conservation and control, use of renewable energy, reduction of greenhouse gas emissions, making the workplace energy efficient, obtaining certification and standards related to energy management, and use of environmentally friendly fuels. These sub-criteria are directly related to the United Nations 17 Sustainable Development Goals of affordable and clean energy (SDG 7) and climate action (SDG 13) and are considered priority factors in improving environmental performance in institutions [29].

2.1.3. Product Sustainability

Strategic practices that aim to minimize the environmental impact of a product throughout its entire life cycle and maximize the efficiency of natural resource use form the basis of product sustainability. This type of understanding necessitates the adoption of environmentalism in production technologies, increased resource efficiency, and sustainable waste management at every stage [43,55]. Product sustainability is directly related to responsible production and consumption (SDG 12) within the United Nations’ 17 Sustainable Development Goals. In addition, incorporating sustainable practices for the products in question encourages the reduction of environmental impacts during production, consumption, and reverse logistics stages [29].

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA), eco-labeling, sustainable supply chain practices, and product recovery are among the many components that constitute sustainable product management in an organizational context [56]. These practices positively influence not only environmental performance but also corporate reputation, customer loyalty, and legal compliance [42]. Firms that reduce waste, are careful about the materials used in their production processes, and develop environmentally friendly innovations and products tend to receive customer support and gain a competitive advantage [57]. Environmentally friendly product innovations contribute to firm competitiveness through differentiation strategies [32]. Based on the reports of large companies such as Huawei and Shell between 2010 and 2019, an analysis of the UN sustainable development goals they prioritized reveals that factors such as inclusive, equitable, and quality education, along with the use of low-cost clean energy and responsible behavior in both production and consumption, come to the fore [58].

Although consumers need to be informed and guided about eco-friendly packaging, studies in the field show that a significant proportion of consumers prefer eco-friendly packaging over standard packaging when purchasing products [59].

This study addresses the use of recyclable materials in production and packaging, the sustainability auditability of the supply chain, sustainable practices in product management and the product life cycle, the acquisition of product-related certifications and standards, the recycling of products after sale, and the eco-friendly product transportation program, all within the scope of product sustainability.

2.2. Research Objectives/Questions and Hypothesis

Based on the gaps identified in the literature and the practical significance of stakeholder differences, this study is guided by three main objectives:

- RQ1. How do academic and firm executives prioritize environmental sustainability criteria within the SDG framework, and what differences emerge between these priorities?

- RQ2. When synthesized using the AHP method, what hierarchical pattern do the prioritization structures of these two stakeholder groups form?

- RQ3. What practical applications do these differences between stakeholders offer for corporate sustainability strategies and SDG-aligned policy design?

Recent studies show that sustainability priorities differ according to the roles, incentives, and decision-making logic of corporate actors. While universities and knowledge-based organizations are expected to emphasize long-term ecological transitions and systemic environmental goals [9], firms tend to adopt sustainability practices that respond to market pressures, customer expectations, and short-term competitive gains [25]. Based on these differing orientations, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1.

Firm managers prioritize product-focused sustainability criteria, while academics prioritize resource and waste management criteria.

This Hypothesis reflects the well-documented differences between market-oriented decision environments and science-oriented ecological perspectives, offering an analytical basis for interpreting the AHP results presented in this study. The sustainability criteria used in Table 1 have been selected and structured in accordance with established frameworks in the literature, forming the basis of the AHP model.

Table 1.

Environmental Sustainability Criteria and References Addressing the Criteria.

3. Materials and Methods

The analytical hierarchy process (AHP) method, one of the multi-criteria decision-making methods, was used to analyze the data collected in this study. This method determines the optimal option by weighting the relative importance of various criteria evaluated by decision-makers [72]. The AHP method is based on decomposing a complex problem into clusters and subclusters to express it simply within a hierarchical structure, and then examining the contribution of the criteria at each level of the hierarchy to the next higher level through pairwise comparisons [73,74]. Furthermore, one of the most common methods used in evaluating applications and dimensions considered in terms of sustainable development is AHP [75].

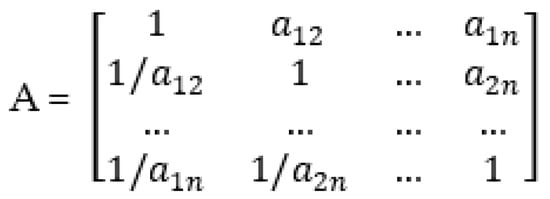

The pairwise comparison matrix used in the first level of the AHP model is shown in Figure 1. Each element aᵢⱼ represents the relative importance of criterion i over criterion j using Saaty’s 1–9 scale. After the matrix was constructed, priority vectors were calculated using the eigenvalue method.

Figure 1.

Binary comparison matrix used in the AHP model.

This study aims to identify the priorities of academics and company managers regarding environmental sustainability and compare them. To this end, the literature was first reviewed to identify the key factors addressed within the scope of environmental sustainability and the applications related to these factors. The three key factors within the scope of environmental sustainability and the applications they encompass were expressed through pairwise comparisons in accordance with the AHP method. Therefore, data was collected using a questionnaire that compared each factor and practice on a nine-point scale, as suggested in previous studies [73,74]. The questionnaire was developed using environmental sustainability factors and practices found in important studies in the field. These factors and practices, which are aligned with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals 6, 7, 12, 13, and 15, have been submitted for evaluation by academics and company executives. The scales used in the study and their references are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Scales of the survey.

In line with previous AHP applications in sustainability assessments [35,38], experts were selected based on their proven academic or managerial experience in the fields of environmental sustainability, renewable energy planning, circular economy initiatives, or corporate sustainability strategy. In line with the study’s analytical management and exploratory structure, purposive sampling was used from non-random sampling methods. As this sampling approach aimed to capture depth of expertise rather than breadth, the results should be interpreted as exploratory and indicative, providing insight into the patterns that emerged rather than trends at a generalizable population level [76]. Accordingly, surveys were distributed to two different groups, academics and company managers in the Zonguldak province of Turkey, between May 2025 and July 2025. The Zonguldak province was chosen because it represents the renewal of old production methods, particularly in the context of developing countries, taking environmental sustainability into account.

Academics were selected from individuals working in the environmental engineering department who had received seminars, training, or certification in the field of sustainability from private and/or public institutions and had published on sustainability. Company managers were selected from individuals working in management positions in companies operating in the energy, textile, iron and steel, ceramics, and rubber manufacturing sectors, particularly those working on sustainability-related investments within their organizations. All experts were contacted individually via email, given detailed instructions, and independently completed the matching comparison matrices. This procedure is consistent with recommended practices in AHP studies that prioritize expert knowledge over representativeness [38]. Ethical approval for this survey-based research was obtained from the Zonguldak Bülent Ecevit University Human Research Ethics Committee (Approval Date: 10.03.2025; Protocol No: 114), and informed consent was obtained from all participants. A total of seven surveys were completed by academics and five by company managers. Following data collection, each survey was analyzed using the AHP method with the SuperDecision (3.2.0) software, and consistency ratios were examined. To ensure validity, each calculated consistency ratio was required to be less than 0.10 [77,78]. To enhance methodological transparency, all materials used in the AHP analysis are provided in the appendices. Appendix A contains the complete questionnaire, including all criteria and sub-criteria used in the pairwise comparisons. Appendix B presents the raw pairwise comparison matrices along with the pooled matrices obtained using the geometric mean method, which is a standard approach in multi-expert AHP applications [35]. Respondents whose results did not meet this criterion or whose data were incomplete were contacted again, missing information was completed, and they were asked whether they wished to revise their responses to resolve inconsistencies. To obtain the acceptable consistency ratios, respondents were asked whether they wanted to revise their answers. At that point, in order not to influence their judgements, certain inconsistencies between their answers have been revealed and indicated with an appropriate explanation. Respondents were merely demanded to re-evaluate these specific answers. Throughout this process, their decisions were not intervened, influenced or directed by researchers in any way. This process was repeated until all consistency ratios met the reference values. Then, matrices were created and the relevant weights were calculated.

Equations (1)–(3) show the variables (λmax, CI, CR, and wi) related to the calculation of consistency and weights. Here, λmax indicates the maximum eigenvalue of the comparison matrix and is used to evaluate overall judgment consistency; CI (Consistency Index) reflects the degree of deviation from perfect consistency; CR (Consistency Ratio) determines whether the level of inconsistency is acceptable by comparing CI with the Random Index; and wᵢ represents the normalized priority weight of each criterion. To ensure transparency, each variable and calculation step is directly explained in the text, and the consistency ratios are provided in tables in the results section, while the complete set of matrices is given in Appendix B.

Matrices were then created, and the relevant weights were calculated. In addition, the environmental factors and applications prioritized by each participant were determined using a program called SuperDecision (3.2.0). Additionally, matrices prepared for participants in each group were combined using the geometric mean method to compare the priorities of academics and company managers regarding environmental practices [79]. The consistency ratios of the combined matrices were checked and analyzed using the same method.

4. Results

4.1. Demographic Findings

In this study, participants were asked to indicate the duration of operations, legal status, number of employees, annual net sales revenue, and annual balance sheet total of the company or institution they work for, along with their position within that company or institution. However, no answers could be obtained to these questions because academics were not aware of the data in question. In this regard, only demographic information belonging to company managers involved in the study has been reported. Furthermore, considering the sensitivity of the requested data for businesses, answering these questions is not mandatory. The resulting data is presented in Table 3. Table 3 summarizes the profiles of the expert participants. This information provides contextual background for interpreting the subsequent AHP results and clarifies the professional experience behind the judgments used to address the research objectives. As can be seen from the table, 60% of the companies are corporations and 40% are limited liability companies. 80% of the companies have been operating for more than fourteen years and employ more than two hundred and fifty people. In contrast, 20% of the participating companies chose not to disclose information about their annual net sales revenue and total financial balance sheet. All companies in the top 80% responding to questions about these two demographic variables reported having annual net sales revenue and total financial balance sheet assets exceeding 500,000,000 TL. Based on data regarding the number of employees, annual net sales revenue, and total financial balance sheet, it was determined that 60% of participating businesses were large-scale [80,81].

Table 3.

Demographic characteristics of the participants and the companies.

4.2. Findings from the AHP Analysis

In this study, environmental practices were examined in three groups: “resource and waste management,” “energy management,” and “product sustainability.” The consistency ratios for the comparison matrices of these three criteria and their sub-criteria have been calculated and presented in the relevant tables. As shown in Table 4 and Table 5, the ranking of the main criteria differs between academics and company managers. While academics place the highest weight on resource and waste management, company managers place greater importance on product sustainability. This trend directly reflects the hypothesis that managers prioritize market-sensitive, product-focused applications, while academics focus more on ecological management and resource-related issues.

Table 4.

Each Company’s Priorities Regarding Environmental Sustainability Factors.

Table 5.

Each Academic’s Priorities Regarding Environmental Sustainability Factors.

As can be seen in Table 4, consistency has been ensured for the responses of each company manager. However, according to the analysis results, three of companies prioritize product sustainability, one prioritize resource and waste management, and the remaining one prioritize energy management. The vast majority of companies (four to five) prioritize solid waste management and water resource conservation within the framework of resource and waste management. In terms of energy management applications, companies view the acquisition of relevant certifications and standards as equally important to each other, but as a priority compared to other aspects of energy conservation and control. In addition, various companies are prioritizing the use of renewable energy and the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions. Companies offer different views on practices related to product sustainability. In addition to those who prioritize the use of recyclable materials in production and packaging, there are also companies that emphasize obtaining relevant certifications, ensuring the sustainability of the supply chain, and recycling end-of-life products.

Table 5 shows each academic’s assessments of the criteria within the scope of environmental practices and their sub-criteria, along with the consistency rates for each of these assessments. As can be seen from Table 4, the vast majority of academics (six to seven) prioritize resource and waste management over both energy management and product sustainability. Within the framework of resource and waste management, approximately three of academics consider solid waste management to be a priority over other application areas, while three of them consider the protection of water resources to be a priority. In contrast, approximately one academic consider noise pollution to be important. Among energy management practices, approximately three academics prioritize energy conservation, while another three prioritize obtaining relevant certifications and standards. As another finding, only one academic prioritize the use of renewable energy. When the academics’ responses were evaluated in terms of product sustainability, it was found that five academics prioritized the use of recyclable materials in production or packaging.

Table 6 and Table 7 provide a more detailed view of how each stakeholder group evaluated the sub-criteria within the three main dimensions. For managers, product-related factors such as the use of recycled materials, supply chain control, and product certification generally receive the highest weightings, supporting the market-oriented perspective identified in the research objectives. Academics, on the other hand, systematically place greater importance on criteria linked to long-term environmental protection, such as water resource conservation, solid waste management, and greenhouse gas emission reduction. These results demonstrate how the same set of sustainability criteria can be interpreted differently depending on the stakeholder’s role, thereby enabling the study to achieve its goal of comparing stakeholder priorities within an SDG-focused framework.

Table 6.

Combining the Weights Obtained for Companies Using the Geometric Mean Method.

Table 7.

Combining the weights obtained for academics using the geometric mean method.

The matrices created from the responses of company managers were combined using the geometric mean method. As can be seen in Table 6, the consistency ratios meet the reference value. In this context, company managers consider product sustainability to be more important than both energy management and the management of resources and waste. Furthermore, the results show that companies consider energy management and resource and waste management to be of equal importance. When company managers evaluate practices related to product sustainability, the use of recyclable materials in production, the auditability of the supply chain in terms of sustainability, and product certification stand out compared to other factors. Company executives state that the priority practices in terms of resource and waste management are solid waste management, water resource conservation, and meeting the necessary standards and obtaining certifications. Reducing greenhouse gas emissions related to energy management, obtaining relevant certifications, and conserving and monitoring energy have been prioritized as key practices.

Similarly, the matrices constructed based on the opinions of academics were aggregated using the geometric mean method, and the resulting matrix was subsequently analyzed. As presented in Table 7, the consistency ratios fall within the acceptable reference value. According to the results, unlike company managers, academics place greater importance on resource and waste management than on product sustainability and energy management. Academics state that product sustainability and energy management are of similar importance. In terms of practices within the scope of resource and waste management, it can be seen that academics emphasize the protection of water resources, followed by solid waste management and the acquisition of relevant certifications. When evaluating product sustainability, it is understood that academics prioritize the use of recyclable materials in packaging and the management applied in this process throughout the product life cycle. Within the scope of energy management, the applications that academics consider important are primarily the conservation and control of energy, followed by the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions and the acquisition of necessary standards and certifications.

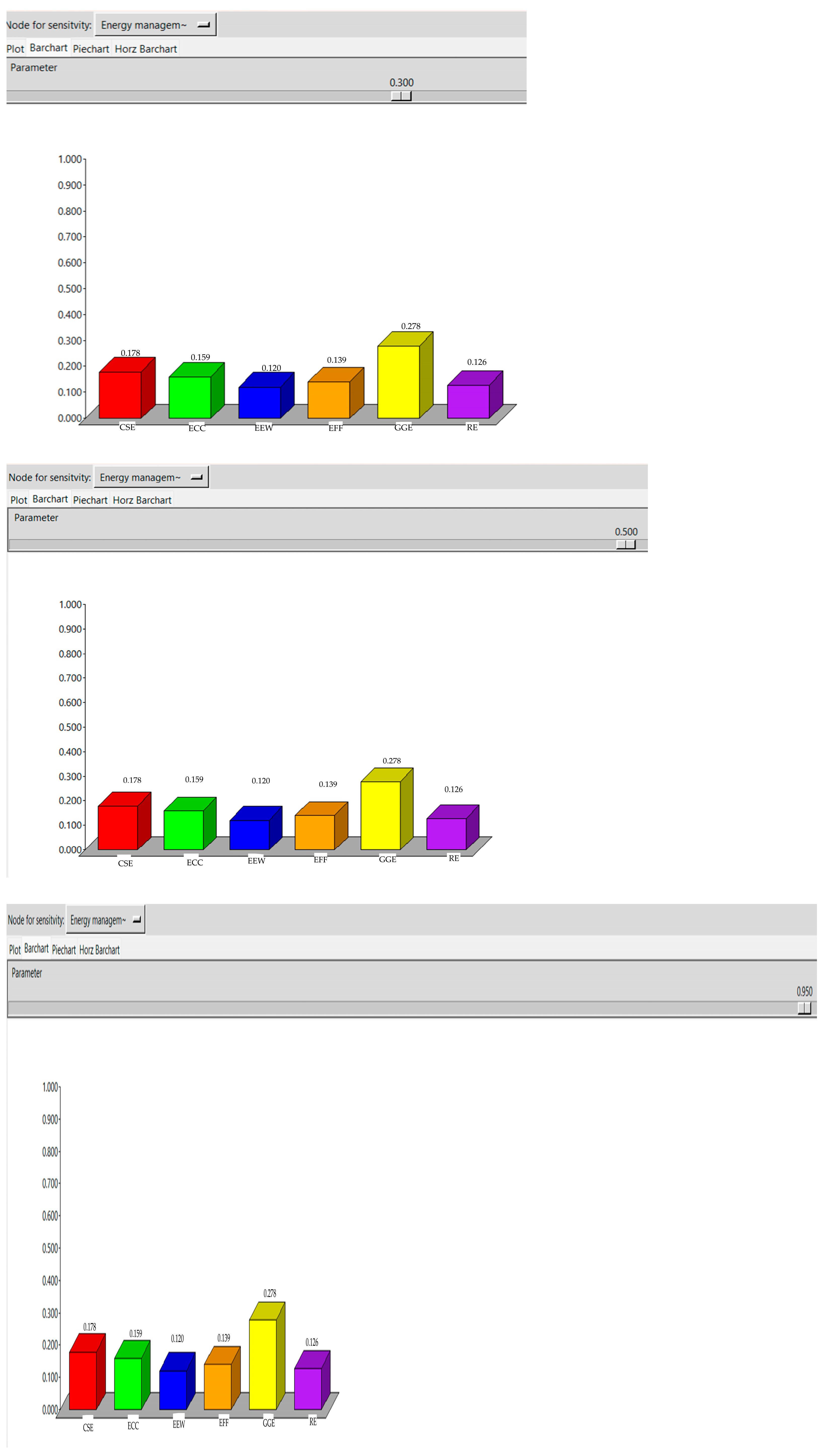

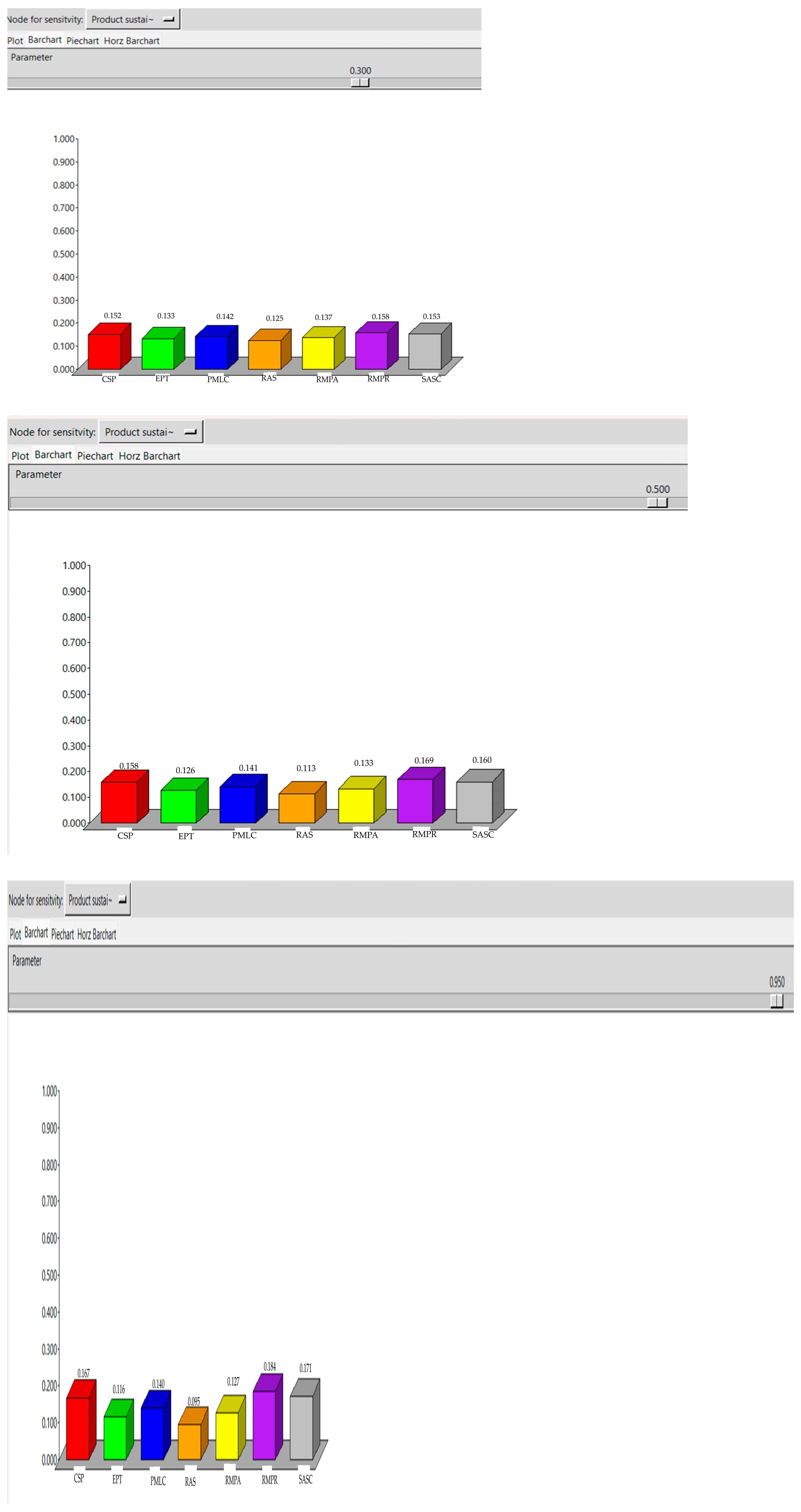

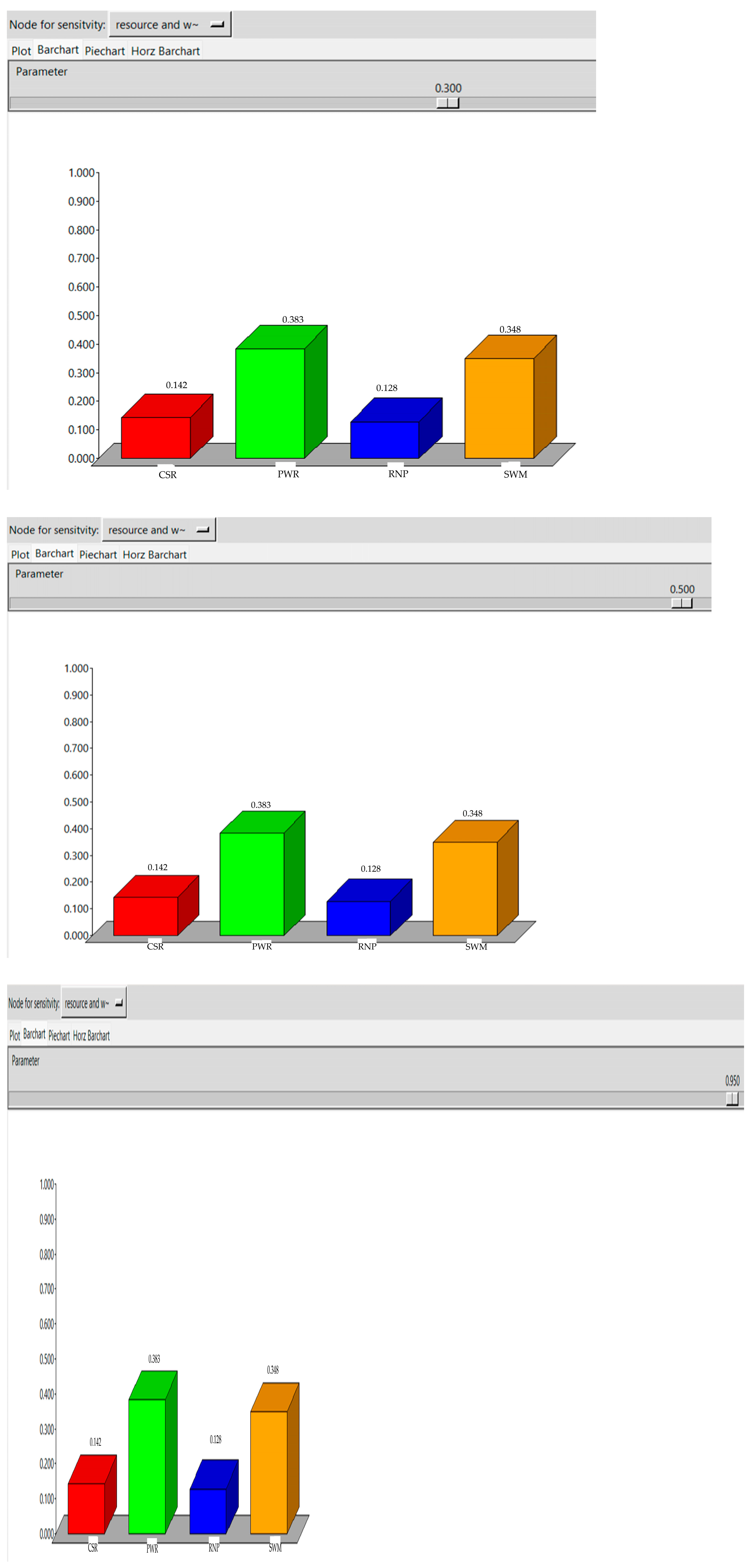

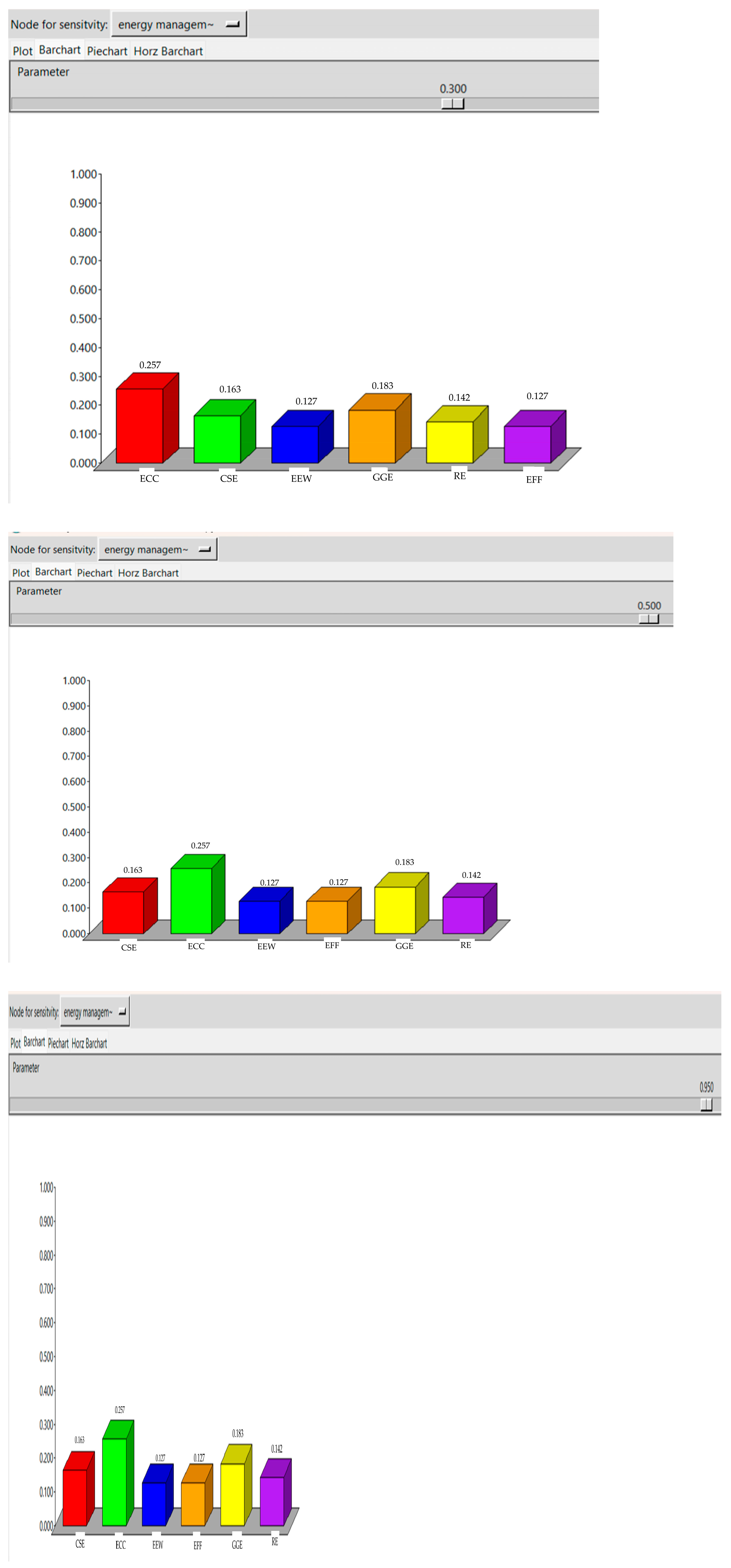

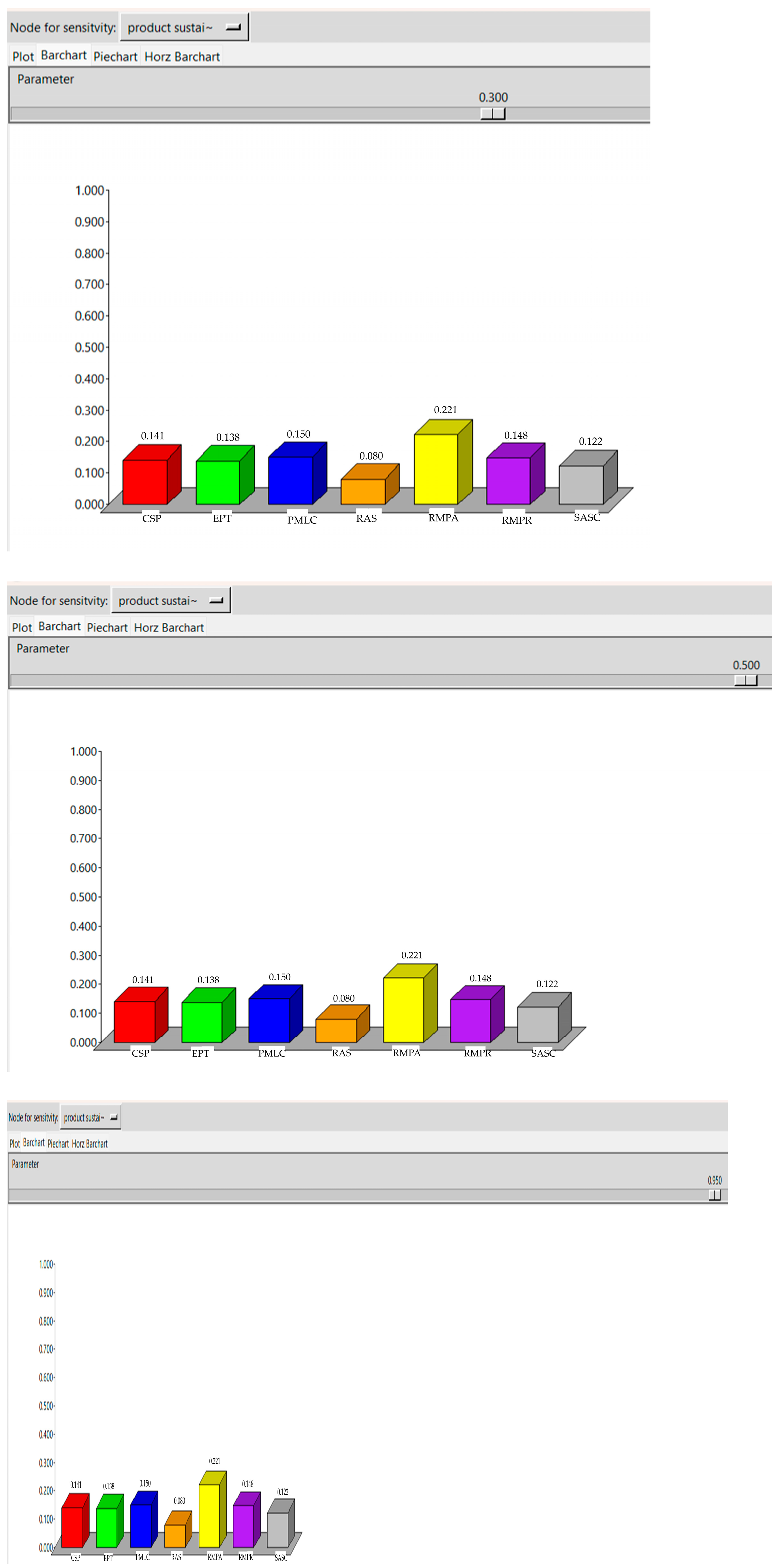

4.3. Sensitivity Analysis Procedure

In this study, a sensitivity analysis was conducted to approve the consistency, stability and robustness of the outcomes of the AHP test. A dynamic sensitivity analysis method has been conducted through the SuperDecisions module. Three different levels of (0.30; 0.50; 0.95) were applied to the AHP model developed in this research. The findings and phases of this test are presented in Appendix C. As weight distribution changed, the ranking of criteria did not change dramatically for both samples (academicians and firm executives). These results have proved that the outcomes of this study are stable and robust. This finding is consistent with the expectations of robustness described in recent sustainability-focused Multi-Criteria Decision-Making (MCDM) studies [35,38].

5. Discussions

This study provide a structured comparison of how academics and company managers prioritize environmental sustainability criteria. Consistent with the hypothesis presented in the study, company managers place greater importance on product-related practices, particularly the use of recycled materials, supply chain control, and product certification. This reflects a market-sensitive approach to sustainability. In contrast, academics place greater emphasis on resource and waste management, highlighting the conservation of water resources, solid waste management, and the broader ecological impacts of material use. However, both groups agree on the importance of renewable energy and greenhouse gas reduction in the energy dimension. These findings confirm that stakeholder groups approach sustainability from different but complementary perspectives, and this has direct implications for SDG-focused decision-making and policy design.

The distinct priorities of academics and firm managers can be understood through the combined lenses of the Resource-Based View and stakeholder theory. Managers tend to focus on product-level sustainability criteria such as recyclable materials or eco-label compliance in sectors with higher degrees of technological integration; because these dimensions offer visible competitive advantages and are aligned with market incentives and regulatory expectations [37,40]. In contrast, academics emphasize resource conservation and long-term ecological resilience, reflecting the future-oriented and normative concerns highlighted in stakeholder theory [82]. Recent research on renewable energy decision support tools [38] and green credit policies [39] shows that sustainability initiatives generally prioritize system-level environmental outcomes over firm-specific operational measures. These findings have examined the roles of different actors and incentive structures in the selection and implementation of sustainability criteria for a single stakeholder group, but there are very few studies that directly compare how different actors prioritize the same environmental criteria. By filling this gap, the study offers a comparative and multi-stakeholder perspective that is largely lacking in the existing literature. They also provide a theoretical framework explaining why AHP results of this study reveal a more product-focused approach among managers and a stronger ecological emphasis among academics.

The differences in priorities between firm managers and academics stem from the structural divergence between market incentives and systemic ecological concerns. Firm managers focus on product-level sustainability criteria that offer short-term competitive advantages such as brand reputation, customer demand, and certification; visible practices such as recycled materials or eco-label compliance can be rapidly adopted across industries [37,83]. In contrast, academics emphasize assessments that prioritize long-term environmental risks, resource conservation, and system-level ecological resilience [40,82]. Compared to these studies in the literature, analysis of this study offers a methodological innovation by integrating AHP with dual stakeholder assessment. This dual assessment provides deeper insight into how institutional logic shapes sustainability decisions, which has not been captured simultaneously by existing studies. Furthermore, this study expands the literature by demonstrating how these stakeholder differences translate into concrete priority structures within an SDG-focused framework—a topic rarely addressed in contemporary sustainability research. This provides an exploratory contribution by revealing not only which stakeholders prioritize what, but also why these differences arise and how they can contribute to developing more inclusive policies and strategies.

Limitations and Implications

The study aims to identify differences in the views of academics and companies and to combine their priorities regarding environmental sustainability within a common framework; however, it has certain limitations by its very nature. The first limitation is that the study was conducted on a sample limited to the Zonguldak province of Turkey. Therefore, the generalizability of the findings is limited, and different results may be obtained in different regions with larger and more diverse samples. The use of a purposive expert sample is consistent with recent AHP applications in sustainability decision-making [35,84], but this approach prioritizes depth of expertise over representativeness of the population. From a methodological perspective, the fact that the AHP method used relies on the subjective judgments of decision-makers is the second major limitation of the study. This means that the results may vary depending on the individual experiences and perceptions of the participants. Furthermore, the perspectives reported here are shaped by the specific institutional and market context in which the experts operate, and these conditions may differ from those in other countries, sectors, or organizational environments. Company managers and academics have different levels of knowledge about sustainability. This situation may lead to subjective assessments regarding the importance of certain criteria. Finally, the AHP method reduces complex sustainability judgments to structured pairwise comparisons [74]. While this structure enhances clarity and internal consistency, it cannot fully capture the broader social, organizational, and institutional dynamics that influence sustainability preferences. For these reasons, the results should be interpreted with caution and viewed as an indicative contribution that provides a basis for more comprehensive, multi-stakeholder research.

This study is the first to compare sustainability priorities among academics and company executives, while also offering various opportunities for future research. The next step is to conduct a more comprehensive AHP study across various provinces and sectors in Turkey, thereby incorporating a wider range of corporate and regional perspectives.

Although this study does not perform a full AHP-TOPSIS triangulation or Delphi consensus round, both methods are discussed as important extensions for future research. In particular, the proposed AHP-TOPSIS framework offers a promising way to validate the comparative rankings identified in this exploratory expert-based study. Future studies could collect data from two different sample groups and determine comparative priorities by using methods such as AHP, TOPSIS, and DELPHI together for each sample. Expanding the participant base and incorporating complementary decision-making methods will not only strengthen generalizability but also support the development of practical sustainability roadmaps aligned with national and regional objectives.

To ensure that the insights gained from our AHP analysis can guide real-world decision-making processes, it is crucial to define a practical and measurable set of sustainability KPIs (Key Performance İndicator). Useful indicators for companies include metrics commonly used in circular packaging and sustainable supply chain assessments, such as the recycled content ratio in packaging, waste diversion rate, and water intensity per unit of output [85,86]. At the municipal level, measures such as the local recycling rate, waste generation per capita, and industrial energy efficiency indicators provide realistic criteria for monitoring environmental performance [87].

Furthermore, sustainability outcomes can be improved through structured collaboration platforms where academics and company executives work together to design sector roadmaps, develop certification programs, or launch recycling-based pilot initiatives. Evidence shows that such multi-stakeholder platforms significantly strengthen regional sustainability and support the implementation of SDGs [88]. By combining measurable KPIs with structured stakeholder collaboration, organizations can act more systematically, taking into account the different priorities identified in this study.

6. Conclusions

This study comparatively examines how academics and company executives prioritize environmental sustainability criteria within an SDG-focused framework by using AHP method. The findings confirm that the two groups approach sustainability with different but complementary perspectives. Managers emphasize product-related, market-sensitive practices, while academics prioritize ecological and resource-based issues. These insights help us better understand the differences among stakeholders in sustainability decisions and offer practical implications for designing inclusive, evidence-based sustainability strategies.

This study offer practical insights for companies seeking to strengthen their sustainability strategies, particularly in aligning market-driven initiatives such as product sustainability and certification practices with broader environmental goals.

For policymakers and practitioners, the results highlight the need to promote integrated approaches that balance product-level sustainability with effective resource management. Academics, meanwhile, can use these insights to develop frameworks that reflect the multidimensional nature of sustainability decision-making.

While the study provides a valuable foundation, future research could examine whether these prioritization models are valid across different sectors, corporate sizes, and national contexts. Further research could also explore collaboration mechanisms that enable industry and academia to advance sustainability goals together.

Although the small sample size limits the generalizability of the study findings, it offers an exploratory perspective on identifying the priorities of academics and company managers in terms of environmental sustainability as the concept of production is being renewed in developing economies.

In conclusion, the findings of the study emphasize that it is appropriate to bring together the differences between companies and academics within a common framework. In this regard, lawmakers must develop mechanisms focused on environmental protection while also adopting a market-oriented approach.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization. F.S. and A.U. methodology. F.S. and A.U.; software. F.S. and A.U.; validation. F.S. and A.U.; formal analysis. F.S. and A.U.; investigation. F.S.; resources. F.S.; data curation. A.U.; writing—original draft preparation. F.S. and A.U.; writing—review and editing. A.U.; visualization. A.U.; supervision. F.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Zonguldak Bülent Ecevit University Human Research Ethics Committee (No: 114; 10 March 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed at the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Questionaire

This questionnaire was prepared as part of the research named “Environmental Sustainability Priorities within the Framework of UN Sustainable Development Goals: An AHP Analysis of Academicians and Firm Managers”, conducted by academicians at Zonguldak Bülent Ecevit University. The information you provide will be used only for academic aims and the results will be shared with respondents. We thank you for your valuable contribution.

- 1.

- Please, assess and compare the environmental sustainability factors based on your firm’s perspective.

| Intensity of Importance | Explanation | |

| 1 |  | Two activities/items contribute equally to the objective |

| 3 |  | Experience and judgement slightly favor one activity over another |

| 5 |  | Experience and judgement strongly favor one activity over another |

| 7 |  | An activity is strongly favored, and its dominance is demonstrated in practice |

| 9 |  | The evidence favoring one activity over another is of the highest possible order of affirmation |

| 2, 4, 6, 8 | When compromise is needed |

| Resource and waste management | 9☐ | 8☐ | 7☐ | 6☐ | 5☐ | 4☐ | 3☐ | 2☐ | 1☐ | 2☐ | 3☐ | 4☐ | 5☐ | 6☐ | 7☐ | 8☐ | 9☐ | Energy management |

| Resource and waste management | 9☐ | 8☐ | 7☐ | 6☐ | 5☐ | 4☐ | 3☐ | 2☐ | 1☐ | 2☐ | 3☐ | 4☐ | 5☐ | 6☐ | 7☐ | 8☐ | 9☐ | Product sustainability |

| Energy management | 9☐ | 8☐ | 7☐ | 6☐ | 5☐ | 4☐ | 3☐ | 2☐ | 1☐ | 2☐ | 3☐ | 4☐ | 5☐ | 6☐ | 7☐ | 8☐ | 9☐ | Product sustainability |

- 2.

- Please, assess and compare practices of resource and waste management based on your firm’s perspective.

| Solid waste management | 9☐ | 8☐ | 7☐ | 6☐ | 5☐ | 4☐ | 3☐ | 2☐ | 1☐ | 2☐ | 3☐ | 4☐ | 5☐ | 6☐ | 7☐ | 8☐ | 9☐ | Protecting water resources |

| Solid waste management | 9☐ | 8☐ | 7☐ | 6☐ | 5☐ | 4☐ | 3☐ | 2☐ | 1☐ | 2☐ | 3☐ | 4☐ | 5☐ | 6☐ | 7☐ | 8☐ | 9☐ | Certification and standards for resource use |

| Solid waste management | 9☐ | 8☐ | 7☐ | 6☐ | 5☐ | 4☐ | 3☐ | 2☐ | 1☐ | 2☐ | 3☐ | 4☐ | 5☐ | 6☐ | 7☐ | 8☐ | 9☐ | Reducing noise pollution |

| Protecting water resources | 9☐ | 8☐ | 7☐ | 6☐ | 5☐ | 4☐ | 3☐ | 2☐ | 1☐ | 2☐ | 3☐ | 4☐ | 5☐ | 6☐ | 7☐ | 8☐ | 9☐ | Reducing noise pollution |

| Protecting water resources | 9☐ | 8☐ | 7☐ | 6☐ | 5☐ | 4☐ | 3☐ | 2☐ | 1☐ | 2☐ | 3☐ | 4☐ | 5☐ | 6☐ | 7☐ | 8☐ | 9☐ | Reducing noise pollution |

| Certification and standards for resource use | 9☐ | 8☐ | 7☐ | 6☐ | 5☐ | 4☐ | 3☐ | 2☐ | 1☐ | 2☐ | 3☐ | 4☐ | 5☐ | 6☐ | 7☐ | 8☐ | 9☐ | Reducing noise pollution |

- 3.

- Please, assess and compare practices of energy management based on your firm’s perspective.

| Energy conservation and control | 9☐ | 8☐ | 7☐ | 6☐ | 5☐ | 4☐ | 3☐ | 2☐ | 1☐ | 2☐ | 3☐ | 4☐ | 5☐ | 6☐ | 7☐ | 8☐ | 9☐ | Use of renewable energy |

| Energy conservation and control | 9☐ | 8☐ | 7☐ | 6☐ | 5☐ | 4☐ | 3☐ | 2☐ | 1☐ | 2☐ | 3☐ | 4☐ | 5☐ | 6☐ | 7☐ | 8☐ | 9☐ | Reduction of greenhouse gas emissions |

| Energy conservation and control | 9☐ | 8☐ | 7☐ | 6☐ | 5☐ | 4☐ | 3☐ | 2☐ | 1☐ | 2☐ | 3☐ | 4☐ | 5☐ | 6☐ | 7☐ | 8☐ | 9☐ | Energy efficient workplace |

| Energy conservation and control | 9☐ | 8☐ | 7☐ | 6☐ | 5☐ | 4☐ | 3☐ | 2☐ | 1☐ | 2☐ | 3☐ | 4☐ | 5☐ | 6☐ | 7☐ | 8☐ | 9☐ | Obtaining certification and standards related to energy management |

| Energy conservation and control | 9☐ | 8☐ | 7☐ | 6☐ | 5☐ | 4☐ | 3☐ | 2☐ | 1☐ | 2☐ | 3☐ | 4☐ | 5☐ | 6☐ | 7☐ | 8☐ | 9☐ | Use of environmentally friendly fuels |

| Use of renewable energy | 9☐ | 8☐ | 7☐ | 6☐ | 5☐ | 4☐ | 3☐ | 2☐ | 1☐ | 2☐ | 3☐ | 4☐ | 5☐ | 6☐ | 7☐ | 8☐ | 9☐ | Reduction of greenhouse gas emissions |

| Use of renewable energy | 9☐ | 8☐ | 7☐ | 6☐ | 5☐ | 4☐ | 3☐ | 2☐ | 1☐ | 2☐ | 3☐ | 4☐ | 5☐ | 6☐ | 7☐ | 8☐ | 9☐ | Energy efficient workplace |

| Use of renewable energy | 9☐ | 8☐ | 7☐ | 6☐ | 5☐ | 4☐ | 3☐ | 2☐ | 1☐ | 2☐ | 3☐ | 4☐ | 5☐ | 6☐ | 7☐ | 8☐ | 9☐ | Obtaining certification and standards related to energy management |

| Use of renewable energy | 9☐ | 8☐ | 7☐ | 6☐ | 5☐ | 4☐ | 3☐ | 2☐ | 1☐ | 2☐ | 3☐ | 4☐ | 5☐ | 6☐ | 7☐ | 8☐ | 9☐ | Use of environmentally friendly fuels |

| Reduction of greenhouse gas emissions | 9☐ | 8☐ | 7☐ | 6☐ | 5☐ | 4☐ | 3☐ | 2☐ | 1☐ | 2☐ | 3☐ | 4☐ | 5☐ | 6☐ | 7☐ | 8☐ | 9☐ | Energy efficient workplace |

| Reduction of greenhouse gas emissions | 9☐ | 8☐ | 7☐ | 6☐ | 5☐ | 4☐ | 3☐ | 2☐ | 1☐ | 2☐ | 3☐ | 4☐ | 5☐ | 6☐ | 7☐ | 8☐ | 9☐ | Obtaining certification and standards related to energy management |

| Reduction of greenhouse gas emissions | 9☐ | 8☐ | 7☐ | 6☐ | 5☐ | 4☐ | 3☐ | 2☐ | 1☐ | 2☐ | 3☐ | 4☐ | 5☐ | 6☐ | 7☐ | 8☐ | 9☐ | Use of environmentally friendly fuels |

| Energy efficient workplace | 9☐ | 8☐ | 7☐ | 6☐ | 5☐ | 4☐ | 3☐ | 2☐ | 1☐ | 2☐ | 3☐ | 4☐ | 5☐ | 6☐ | 7☐ | 8☐ | 9☐ | Obtaining certification and standards related to energy management |

| Energy efficient workplace | 9☐ | 8☐ | 7☐ | 6☐ | 5☐ | 4☐ | 3☐ | 2☐ | 1☐ | 2☐ | 3☐ | 4☐ | 5☐ | 6☐ | 7☐ | 8☐ | 9☐ | Use of environmentally friendly fuels |

| Use of environmentally friendly fuels | 9☐ | 8☐ | 7☐ | 6☐ | 5☐ | 4☐ | 3☐ | 2☐ | 1☐ | 2☐ | 3☐ | 4☐ | 5☐ | 6☐ | 7☐ | 8☐ | 9☐ | Obtaining certification and standards related to energy management |

- 4.

- Please, assess and compare practices about product sustainability based on your firm’s perspective.

| Use of recyclable materials in production | 9☐ | 8☐ | 7☐ | 6☐ | 5☐ | 4☐ | 3☐ | 2☐ | 1☐ | 2☐ | 3☐ | 4☐ | 5☐ | 6☐ | 7☐ | 8☐ | 9☐ | Use of recyclable materials in packaging |

| Use of recyclable materials in production | 9☐ | 8☐ | 7☐ | 6☐ | 5☐ | 4☐ | 3☐ | 2☐ | 1☐ | 2☐ | 3☐ | 4☐ | 5☐ | 6☐ | 7☐ | 8☐ | 9☐ | The eco-friendly product transportation program |

| Use of recyclable materials in production | 9☐ | 8☐ | 7☐ | 6☐ | 5☐ | 4☐ | 3☐ | 2☐ | 1☐ | 2☐ | 3☐ | 4☐ | 5☐ | 6☐ | 7☐ | 8☐ | 9☐ | The sustainability auditability of the supply chain |

| Use of recyclable materials in production | 9☐ | 8☐ | 7☐ | 6☐ | 5☐ | 4☐ | 3☐ | 2☐ | 1☐ | 2☐ | 3☐ | 4☐ | 5☐ | 6☐ | 7☐ | 8☐ | 9☐ | Sustainable practices in product management and the product life cycle |

| Use of recyclable materials in production | 9☐ | 8☐ | 7☐ | 6☐ | 5☐ | 4☐ | 3☐ | 2☐ | 1☐ | 2☐ | 3☐ | 4☐ | 5☐ | 6☐ | 7☐ | 8☐ | 9☐ | Product-related certifications and standards |

| Use of recyclable materials in production | 9☐ | 8☐ | 7☐ | 6☐ | 5☐ | 4☐ | 3☐ | 2☐ | 1☐ | 2☐ | 3☐ | 4☐ | 5☐ | 6☐ | 7☐ | 8☐ | 9☐ | The recycling of products after sale |

| Use of recyclable materials in packaging | 9☐ | 8☐ | 7☐ | 6☐ | 5☐ | 4☐ | 3☐ | 2☐ | 1☐ | 2☐ | 3☐ | 4☐ | 5☐ | 6☐ | 7☐ | 8☐ | 9☐ | The eco-friendly product transportation program |

| Use of recyclable materials in packaging | 9☐ | 8☐ | 7☐ | 6☐ | 5☐ | 4☐ | 3☐ | 2☐ | 1☐ | 2☐ | 3☐ | 4☐ | 5☐ | 6☐ | 7☐ | 8☐ | 9☐ | The sustainability auditability of the supply chain |

| Use of recyclable materials in packaging | 9☐ | 8☐ | 7☐ | 6☐ | 5☐ | 4☐ | 3☐ | 2☐ | 1☐ | 2☐ | 3☐ | 4☐ | 5☐ | 6☐ | 7☐ | 8☐ | 9☐ | Sustainable practices in product management and the product life cycle |

| Use of recyclable materials in packaging | 9☐ | 8☐ | 7☐ | 6☐ | 5☐ | 4☐ | 3☐ | 2☐ | 1☐ | 2☐ | 3☐ | 4☐ | 5☐ | 6☐ | 7☐ | 8☐ | 9☐ | Product-related certifications and standards |

| Use of recyclable materials in packaging | 9☐ | 8☐ | 7☐ | 6☐ | 5☐ | 4☐ | 3☐ | 2☐ | 1☐ | 2☐ | 3☐ | 4☐ | 5☐ | 6☐ | 7☐ | 8☐ | 9☐ | The recycling of products after sale |

| The eco-friendly product transportation program | 9☐ | 8☐ | 7☐ | 6☐ | 5☐ | 4☐ | 3☐ | 2☐ | 1☐ | 2☐ | 3☐ | 4☐ | 5☐ | 6☐ | 7☐ | 8☐ | 9☐ | The sustainability auditability of the supply chain |

| The eco-friendly product transportation program | 9☐ | 8☐ | 7☐ | 6☐ | 5☐ | 4☐ | 3☐ | 2☐ | 1☐ | 2☐ | 3☐ | 4☐ | 5☐ | 6☐ | 7☐ | 8☐ | 9☐ | Sustainable practices in product management and the product life cycle |

| The eco-friendly product transportation program | 9☐ | 8☐ | 7☐ | 6☐ | 5☐ | 4☐ | 3☐ | 2☐ | 1☐ | 2☐ | 3☐ | 4☐ | 5☐ | 6☐ | 7☐ | 8☐ | 9☐ | Product-related certifications and standards |

| The eco-friendly product transportation program | 9☐ | 8☐ | 7☐ | 6☐ | 5☐ | 4☐ | 3☐ | 2☐ | 1☐ | 2☐ | 3☐ | 4☐ | 5☐ | 6☐ | 7☐ | 8☐ | 9☐ | The recycling of products after sale |

| The sustainability auditability of the supply chain | 9☐ | 8☐ | 7☐ | 6☐ | 5☐ | 4☐ | 3☐ | 2☐ | 1☐ | 2☐ | 3☐ | 4☐ | 5☐ | 6☐ | 7☐ | 8☐ | 9☐ | Sustainable practices in product management and the product life cycle |

| The sustainability auditability of the supply chain | 9☐ | 8☐ | 7☐ | 6☐ | 5☐ | 4☐ | 3☐ | 2☐ | 1☐ | 2☐ | 3☐ | 4☐ | 5☐ | 6☐ | 7☐ | 8☐ | 9☐ | Product-related certifications and standards |

| The sustainability auditability of the supply chain | 9☐ | 8☐ | 7☐ | 6☐ | 5☐ | 4☐ | 3☐ | 2☐ | 1☐ | 2☐ | 3☐ | 4☐ | 5☐ | 6☐ | 7☐ | 8☐ | 9☐ | The recycling of products after sale |

| Sustainable practices in product management and the product life cycle | 9☐ | 8☐ | 7☐ | 6☐ | 5☐ | 4☐ | 3☐ | 2☐ | 1☐ | 2☐ | 3☐ | 4☐ | 5☐ | 6☐ | 7☐ | 8☐ | 9☐ | Product-related certifications and standards |

| Sustainable practices in product management and the product life cycle | 9☐ | 8☐ | 7☐ | 6☐ | 5☐ | 4☐ | 3☐ | 2☐ | 1☐ | 2☐ | 3☐ | 4☐ | 5☐ | 6☐ | 7☐ | 8☐ | 9☐ | The recycling of products after sale |

| Product-related certifications and standards | 9☐ | 8☐ | 7☐ | 6☐ | 5☐ | 4☐ | 3☐ | 2☐ | 1☐ | 2☐ | 3☐ | 4☐ | 5☐ | 6☐ | 7☐ | 8☐ | 9☐ | The recycling of products after sale |

Appendix B

S1. Comparing the three funda8mental components of environmental sustainability (RWM = Resource and waste management; EM = Energy management; PS = Product sustainability; a, b, c = the comparison values from respondents):

S2. Comparison of applications within the framework of resource and waste management (SWM = Solid waste management; PWR = Protecting water resources; CSR = certification and standards for resource use; RNP = Reducing noise pollution)

S3. Comparison of applications within the framework of energy management (GGE = Reduction of greenhouse gas emissions; CSE = certification and standards related to energy management; ECC = Energy conservation and control; EFF = Environmentally friendly fuels; RE = renewable energy; EEW = Energy efficient workplace)

S4. Comparing practices related to product sustainability (RMPR = Recyclable materials in production; SASC = the sustainability auditability of the supply chain; CSP = Product-related certifications and standards; PMLC = Sustainable practices in product management and the product life cycle; RMPA = Recyclable materials in packaging; EPT = Eco-friendly product transportation program; RAS = Recycling of products after sale)

The geometric mean used in combining the respondents and its representation in the sample matrix (n = number of respondents; = each respondent’s evaluation for the relevant comparison):

Combining the matrices as an example for data collected from five different companies (a, b, c = comparison values from respondents; other matrices have been combined in the same way):

Appendix C

The sensitivity analyses of resource and waste management practices for firms’ answers (0.30; 0.50; 0.95).

The sensitivity analyses of energy management practices for firms’ answers (0.30; 0.50; 0.95).

The sensitivity analyses of product sustainability practices for firms’ answers (0.30; 0.50; 0.95).

The sensitivity analyses of resource and waste management practices for academics’ answers (0.30; 0.50; 0.95).

The sensitivity analyses of energy management practices for academics’ answers (0.30; 0.50; 0.95).

The sensitivity analyses of product sustainability practices for academics’ answers (0.30; 0.50; 0.95).

References

- Ritchie, H.; Samborska, V.; Roser, M. Plastic Pollution. Our World in Data 2024. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/plastic-pollution (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- The Guardian. Just 9.5% of Plastic Made in 2022 Used Recycled Material, Study Shows. 4 October 2025. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2025/apr/10/just-95-of-plastic-made-in-2022-used-recycled-material-study-shows (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Guler, Y.; Kumar, P. Climate change policy and performance of Turkiye in the EU harmonization process. Front. Sustain. Cities 2022, 4, 1070154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, D.; Colbert, B.; Freeman, R.E. Focusing on value: Reconciling corporate social responsibility, sustainability and a stakeholder approach in a network world. J. Gen. Manag. 2003, 28, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, S.L. A natural-resource-based view of the firm. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 986–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, S.; Dowell, G. A Natural-Resource-Based View of the Firm: Fifteen Years After. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 1464–1479. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 14001; Environmental Management Systems—Requirements with Guidance for Use. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2004. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/31807.html (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Link, S.; Naveh, E. Standardization and discretion: Does the environmental standard ISO 14001 lead to performance benefits? IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2006, 53, 508–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Adamo, I. The analytic hierarchy process as an innovative way to enable stakeholder engagement for sustainability reporting in the food industry. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 25, 15025–15042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wątróbski, J.; Bączkiewicz, A.; Rudawska, I. A Strong Sustainability Paradigm based Analytical Hierarchy Process (SSP-AHP) method to evaluate sustainable healthcare systems. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 154, 110493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; van der Linde, C. Toward a New Conception of the Environment-Competitiveness Relationship. J. Econ. Perspect. 1995, 9, 97–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambec, S.; Lanoie, P. Does It Pay to be Green? A Systematic Overview. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2008, 22, 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siuda, D.; Grębosz-Krawczyk, M. The Role of Pro-Ecological Packaging in Shaping Purchase Intentions and Brand Image in the Food Sector: An Experimental Study. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EY Türkiye. Atık Yönetimi ve Geri Dönüşüm Sektör Analizi; EY Türkiye: İstanbul, Türkiye, 2024; Available online: https://www.ey.com/tr_tr/technical/ey-turkiye-yayinlar-raporlar/atik-yonetimi-geri-donusum-sektor-analizi (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Çevre ve Şehircilik ve İklim Değişikliği Bakanlığı. Sıfır Atık Hareketi ile Geri Kazanım Oranı %35’e Ulaştı. 2024. Available online: https://cygm.csb.gov.tr/sifir-atik-ile-geri-kazanim-orani-35e-ullasti.-haber-286897 (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Delmas, M.A.; Toffel, M.W. Organizational responses to environmental demands: Opening the black box. Strateg. Manag. J. 2008, 29, 1027–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cash, D.W.; Clark, W.C.; Alcock, F.; Dickson, N.M.; Eckley, N.; Guston, D.H.; Jäger, J.; Mitchell, R.B. Knowledge systems for sustainable development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 8086–8091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Hel, S. New science for global sustainability? The institutionalisation of knowledge co-production in Future Earth. Environ. Sci. Policy 2016, 61, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caradonna, J.L. Sustainability: A History; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Brundtland, G.H. Our Common Future: World Commission on Environment and Development; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987; Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/5987our-common-future.pdf (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Elkington, J.; Rowlands, I.H. Cannibals with forks: The triple bottom line of 21st century business. Altern J. 1999, 25, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldelli, A.; Parmigiani, M.L. Management Information System—A Tool for Corporate Sustainability. J. Bus. Ethics. 2004, 55, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tantayanubutr, M.; Panjakajornsak, V. Impact of green innovation on the sustainable performance of food industrial firms applying green industry initiatives under the Green Industry Project of the Ministry of Industry of Thailand. Bus. Econ. Horiz 2017, 13, 192–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afum, E.; Osei-Ahenkan, V.; Agyabeng-Mensah, Y.; Amponsah Owusu, J.; Kusi, L.; Ankomah, J. Green manufacturing practices and sustainable performance among Ghanaian manufacturing SMEs: The explanatory link of green supply chain integration. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2020; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, P.L.; Nguyen, D.T. Investigating the effects of green operations management on sustainability performance of manufacturing and service firms: The mediating role of green customer integration in Vietnam. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 466, 142894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kholaif, M.; Xiao, M.; Tang, X. Opportunities Presented by COVID-19 for Healthcare Green Supply Chain Management and Sustainability Performance: The Moderating Effect of Social Media Usage. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2023, 71, 4441–4454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, R. Silent spring. In Thinking About the Environment; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; pp. 150–155. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 3–14 June 1992. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/conferences/environment/rio1992 (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Sayed, Z. Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development. Ethics Crit. Think. J. 2015, 3, 112. [Google Scholar]

- Shakoor, A.; Ahmed, R. The environmental sustainable development goals and economic growth: An empirical investigation of selected SAARC countries. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 116018–116038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, M.J.; Roy, M.-J. Sustainability in action: Identifying and measuring the key performance drivers. Long. Range. Plann. 2001, 34, 585–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersén, J. A relational natural-resource-based view on product innovation: The influence of green product innovation and green suppliers on differentiation advantage in small manufacturing firms. Technovation 2021, 104, 102254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esty, D.C.; Winston, A. Green to Gold: How Smart Companies Use Environmental Strategy to Innovate, Create Value, and Build Competitive Advantage; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Rockström, J.; Steffen, W.; Noone, K.; Persson, Å.; Chapin, F.S., III; Lambin, E.F.; Lenton, T.M.; Scheffer, M.; Folke, C.; Schellnhuber, H.J. A safe operating space for humanity. Nature 2009, 461, 472–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, M.; Ma, J.; Ahmad, N.; Ullah, Z.; Ahmed, R. Uptake and Adoption of Sustainable Energy Technologies: Prioritizing Strategies to Overcome Barriers in the Construction Industry by Using an Integrated AHP-TOPSIS Approach. Adv. Sustain. Syst. 2021, 5, 2100026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, M.; Wang, Z.; Ahmed, N.; Ahmad, M. From waste to treasure: Transforming construction waste into concrete masonry blocks: Challenges and solutions for environmental sustainability in emerging economies. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2025, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Tong, X.; Jia, X. Executives’ Legal Expertise and Corporate Innovation. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 2024, 32, 954–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seran, K.; Rotimi, J.; Le, A. Decision making support tool for renewable energy prioritization to achieve sustainable development goals (SDGs): Conceptual framework. Energy Environ. Sustain. 2025, 1, 100044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Yuan, X. Does green credit promote real economic development? Dual empirical evidence of scale and efficiency. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0326961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Ren, K.; Fu, Y.; He, D.; Pan, M. Institutional investor ESG activism and green supply chain management performance: Exploring contingent roles of technological interdependences in different digital intelligence contexts. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 209, 123789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, M.; Chen, Y.; Jiang, K. All Roads Lead to Rome? A Contingent Configurational Perspective of HRM Systems and Organizational Effectiveness. Pers. Psychol. 2025, 78, 491–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowan, D.M.; Dopart, P.; Ferracini, T.; Sahmel, J.; Merryman, K.; Gaffney, S.; Paustenbach, D.J. A cross-sectional analysis of reported corporate environmental sustainability practices. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2010, 58, 524–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). Towards a Green Economy: Pathways to Sustainable Development and Poverty Eradication; United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2011; Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/126GER_synthesis_en.pdf (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Environmental Noise Guidelines for the European Region; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2018; Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/publications/i/item/9789289053563 (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Lee, S.M.; Lee, D. Effective Medical Waste Management for Sustainable Green Healthcare. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halpe, P.; Adams, M.; Walker, T.R. Challenges and opportunities for ports in achieving net-zero emissions in maritime transport. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2025, 30, 101379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germond, B. The geopolitical dimension of maritime security. Mar. Policy 2015, 54, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alblooshi, B.G.K.M.; Ahmad, S.Z.; Hussain, M.; Singh, S.K. Sustainable management of electronic waste: Empirical evidences from a stakeholders’ perspective. Bus. Strategy. Environ. 2022, 31, 1856–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masson-Delmotte, V.; Zhai, P.; Pirani, A.; Connors, S.L.; Péan, C.; Berger, S.; Caud, N.; Chen, Y.; Goldfarb, L.; Gomis, M.I. Climate change 2021: The physical science basis. Contrib. Work. Group I Sixth Assess. Rep. Intergov. Panel Clim. Change 2021, 2, 2391. [Google Scholar]

- International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA). Renewable Capacity Statistics 2020; International Renewable Energy Agency: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2020; Available online: https://www.irena.org/publications/2020/Mar/Renewable-Capacity-Statistics-2020 (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- ISO 50001; Energy Management Systems—Requirements with Guidance for Use. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- Ahmad, S.; Tahar, R.M. Selection of renewable energy sources for sustainable development of electricity generation system using analytic hierarchy process: A case of Malaysia. Renew. Energy 2014, 63, 458–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera, R.F. The role of natural gas in a low carbon Asia Pacific. Appl. Energy 2014, 113, 1795–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastrocinque, E.; Ramírez, F.J.; Honrubia-Escribano, A.; Pham, D.T. An AHP-based multi-criteria model for sustainable supply chain development in the renewable energy sector. Expert. Syst. Appl. 2020, 150, 113321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 14040; Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment—Principles and Framework. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/37456.html (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Extended Producer Responsibility: Updated Guidance for Efficient Waste Management; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2016; Available online: https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264256385-en (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Fontoura, P.; Coelho, A. How to boost green innovation and performance through collaboration in the supply chain: Insights into a more sustainable economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 359, 132005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wonglimpiyarat, J. Achieving the United Nations sustainable development goals—Innovation diffusion and business model innovations. Foresight 2024, 27, 101–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketelsen, M.; Janssen, M.; Hamm, U. Consumers’ response to environmentally-friendly food packaging—A systematic review. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 254, 120123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensson, N.; Roth, L.; Eklund, M.; Mårtensson, A. Environmental relevance and use of energy indicators in environmental management and research. J. Clean. Prod. 2006, 14, 134–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensson, G. Aspects of sustainable supply chain management (SSCM): Conceptual framework and empirical example. Supply Chain. Manag. Int. J. 2007, 12, 262–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altuntaş, N.; Başaran, İ. İşletmelerin Sürdürülebilir Lojistik Öncelikleri ve Servis Sağlayıcıların Bu Önceliklere Dayalı Performansları: Zonguldak Ticaret ve Sanayi Odasına Bağlı İşletmelerde AHP ve TOPSIS Modellerine Dayalı Bir Araştırma. In Proceedings of the International Social Sciences Conference, Çanakkale Onsekiz Mart University, Çanakkale, Türkiye, 5–6 July 2021; Available online: https://tez.yok.gov.tr/UlusalTezMerkezi/ (accessed on 27 October 2025).