Abstract

This research investigates the different strategies and the dynamic connectedness among AI, ESG, and brown assets from 19 March 2017 to 19 March 2025. Differentiating between contemporaneous and lagged spillover influences provides a detailed view of how the technology-driven and traditional energy sectors interact under shifting geopolitical and environmental conditions. The results indicate that the AI and ESG markets serve as the primary transmitters of information to traditional energy, particularly under extreme market conditions, including the second Trump administration and the Red Sea tensions. Despite rising geopolitical tensions, the findings document that such developments are catalyzing significant shifts toward AI and ESG markets. The findings demonstrate that integrating AI and sustainability principles enhances energy market stability, reduces systemic risk, and accelerates the transition toward low-carbon, climate-resilient energy futures.

1. Introduction

In recent years, the global financial landscape has been revolutionized by new technologies, the surge in environmental awareness, and evolving investor preferences. Inquiries into what defines green investments, combined with the recent increase in climate media attention and a rise in amplified climate uncertainty, including former President Trump’s retraction from recent climate commitments, have added further complications to green investment. Furthermore, central banks worldwide have gradually incorporated climate targets into their policy frameworks, treating climate change as a systemic risk to the financial system [1]. In this context, Quantum, AI, and the brown markets garner the most attention from manager funds, investors, and policymakers to optimize portfolio diversification and risk management, and to reduce climate policy uncertainty.

Accordingly, a rapidly growing number of studies consider AI markets to be attractive investment directions. At the same time, ESG markets have become essential players in sustainable finance [2,3]. In contrast, brown markets such as oil and gas remain vital for heavy industry and the carbon-intensive economy [4]. The integration of AI, ESG, and brown markets into the spillover framework is driven by the evolving nature of the global financial ecosystem. AI is a transformative technological force that revolutionizes industries, reengineers investment strategies, and advances innovation in energy systems. The market reaction to ESG, like that of growth-driven indices, reflects the growing investor shift towards sustainability. This paradigm is supported and bolstered by AI-powered tools such as predictive analytics, sentiment analysis, and risk assessment, among others. Brown markets, the traditional, carbon-heavy sectors, are still large because they are systemically important and vulnerable to environmental and regulatory pressures.

A well-structured theoretical foundation is crucial for understanding the interactions among AI, ESG, and brown markets. Conceptually, these markets are connected through three complementary theoretical channels. First, innovation-driven financial theory states that AI-intensive assets respond quickly to technological cycles, algorithmic trading signals, and information flows, making them early transmitters of market shocks. Second, sustainability-adjusted asset pricing theory indicates that ESG assets react to policy changes, regulatory tightening, and long-term climate risks, transmitting shocks more gradually over time. Third, commodity-finance and resource-dependence theory characterize brown markets as inherently slower-moving but highly sensitive to geopolitical tensions, fossil-fuel shocks, and energy-transition dynamics. Together, these theories suggest a logical interaction where AI shocks propagate immediately, ESG shocks follow with some delay, and brown markets primarily act as volatility absorbers. Despite this theoretical connection, the existing literature has yet to develop an integrated framework that simultaneously examines these three markets or decomposes their spillovers into immediate and delayed effects, leaving a significant empirical gap that this study aims to fill.

From an investor’s perspective, there are different approaches to deciding whether a class is appropriate for investment [5,6,7]. From a risk-reduction standpoint, including an asset in a portfolio can enhance its diversification if it shows negative correlation with another asset in the portfolio; such actions will reduce risk [8,9]. Significant distinctions can be observed between a hedge, a diversifier, and safe haven, as discussed [10,11]. Diversification benefits can be attributed to an asset exhibiting a positive (weak) average correlation with another asset. Hedging benefits are attributed to an asset when it demonstrates, on average, a lack of correlation or negative correlation with other assets. Safe-haven assets exhibit similar characteristics, albeit exclusively in times of market turmoil. Therefore, using a diversifier and hedger can effectively augment the advantages of diversification. Conversely, implementing safe haven instruments mitigates risks in situations requiring such measures [12]. Against the backdrop of portfolio adjustments, the current study has two facets and thus relates to two aspects of the literature: AI stocks, brown markets, and eco-friendly markets such as ESG. In this context, Ref. [13] explored the dependence on AI and energy markets, including renewable energy. Using both linear and non-linear techniques, such as quantile regression and quantile spectral coherency models, the study found that the operation of the energy sector, particularly renewables, is strongly dependent on the functioning of the AI sector. The study suggested important implications for portfolio managers interested in investing in AI and clean energy stocks. Ref. [14] explored the interconnectedness of AI stocks, robotic stocks, and green bonds for portfolio diversification. Empirical observations from copulas and the GFEVD (Generalized Forecast Error Variance Decomposition) indicate significant short-term volatility transmission. However, over time, volatility transmission declines. The study concludes that the AI and general equity indices are not proper instruments for hedging. Ref. [15] documented the reliance on AI stocks and carbon prices. The empirical findings show a negative correlation between the returns of AI stocks and carbon prices. The research findings indicate that AI represents a promising strategy for mitigating the impact of carbon prices. The research results underscored the advantages of incorporating AI stocks into a diversified investment portfolio. The authors [16] investigated the interrelationship between green finance and carbon markets. The findings from vector autoregressive and time-varying parameter models revealed substantial spillover effects among green bonds, renewable energy stocks, and carbon markets. The results offer valuable insights into the interconnectedness between green financial instruments and carbon markets. A substantial body of scholarly literature has previously examined the correlation between AI-related stocks and a diverse range of other stocks and assets. For illustration, Ref. [17] assessed the interconnections between AI stocks and agricultural commodity stocks during COVID-19 and the Russian–Ukrainian War. Some studies have investigated co-movements of AI stocks with the composite stock indices, commodities, green funds, and corporate bonds [18,19]. The authors [20] examined dynamic connectivity among investor attention, Fin Tech, robotics, and AI. The results demonstrate that investor attention is the net recipient of spillovers. Moreover, the effectiveness of hedge funds and the diversification benefits they offer in the face of volatility and brown-market risks have long been challenging for tech, eco-friendly, non-green, and brown asset models of investor behavior.

Based on the above discussion, this study contributes to the existing literature in four ways. First, we fill a significant gap by investigating how the systemic dependencies between AI, green assets, and brown markets, which co-determine climate- and technology-induced transitions, can provide novel insights into how these instruments co-move and interact. Unlike prior studies [9] that examine AI, ESG, and carbon markets in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and the Russia-Ukraine conflict, we expand this study by incorporating and comparing innovative markets with brown markets, including natural gas, aluminum, and rare earths. We further extend the data to March 2025, thereby accounting for recent shocks such as US-China tensions, the Trump-era tariffs, and the Red Sea conflict. Secondly, this research is the first to conduct spillover analysis using AI, ESG, and brown markets, and to implement hedging effectiveness and portfolio strategies based on high- and low-climate media attention events and varying market conditions. Thirdly, we decompose our spillovers into lagged and contemporaneous spillovers and propose the Minimum Connectedness Portfolio (MCoP), which provides unique benefits over existing alternatives within risk management, employing the R2 connectedness approach [11,21,22,23] and portfolio strategies [24,25], representing a significant methodological innovation. Fourthly, the study employs R2-connectedness, including contemporaneous and lagged measures, to assess the magnitude of spillover effects among AI, ESG, and brown markets. Conventional connectedness is based on a unique summary measure, which prevents differentiation of spillover timing. On the other hand, the R2-decomposed approach allows decomposing connectedness into contemporaneous (current) and lagged (delayed) components. This decomposition is essential for understanding the dynamical aspects of market interactions, as it shows not only immediate but also delayed responses of shocks across markets and how these responses evolve over time. Adopting this approach, the research can explore the time-dependent transmission between AI, ESG, and brown markets. It reveals the subtle spillover channels that are generally ignored by mainstream models, e.g., the driving forces of AI and ESG markets as prime information spreaders in turbulent times and their hedging capacities over time. This broader perspective supports a deeper understanding of portfolio diversification strategies and the systemic risk drivers in the green and digital financial ecosystems. This study is structured as follows: Section 2 describes the methods used for the data collection. Section 3 describes the empirical results. Lastly, Section 4 presents conclusions and policy implications.

2. Data and Methodology

2.1. Data

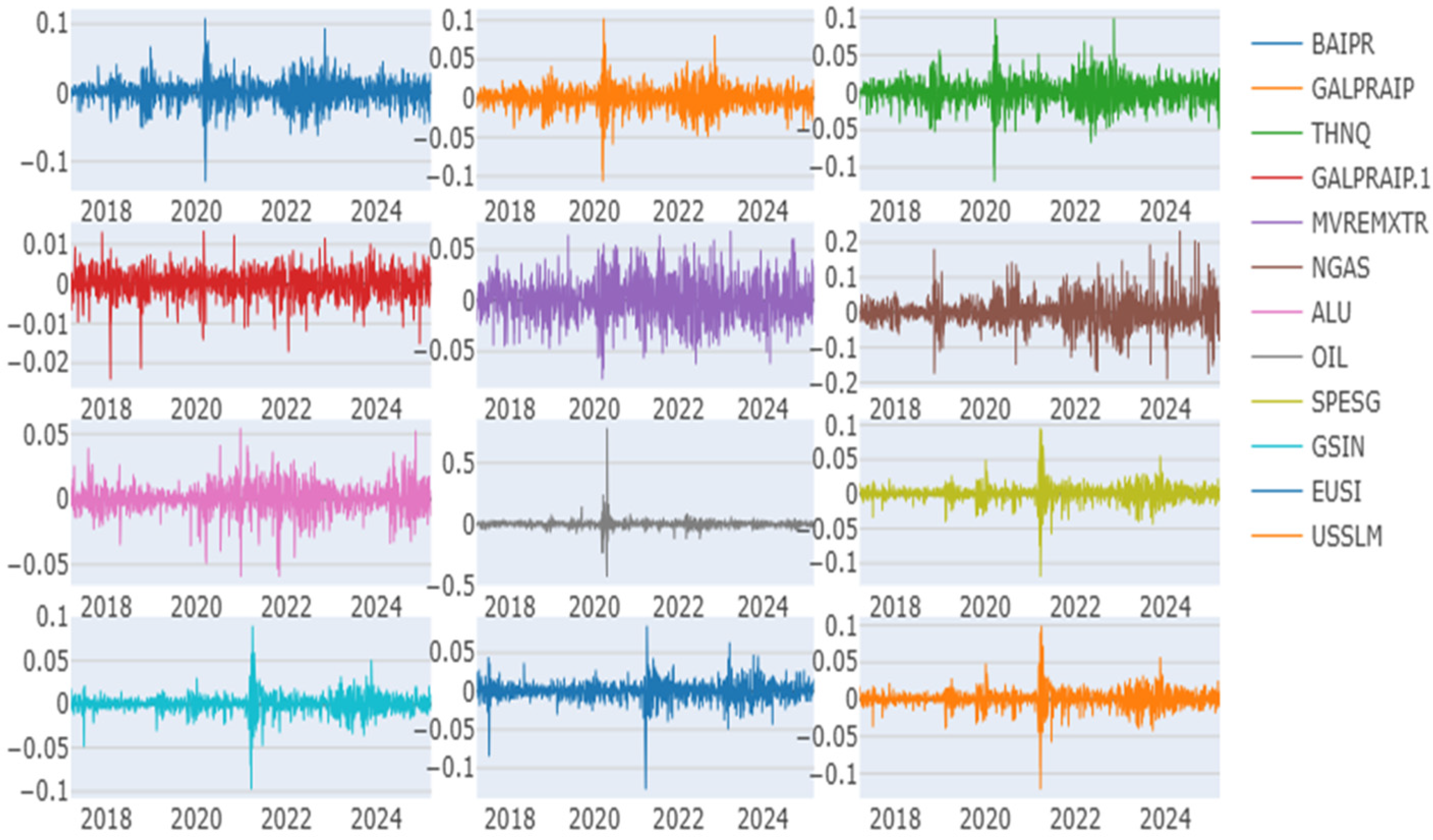

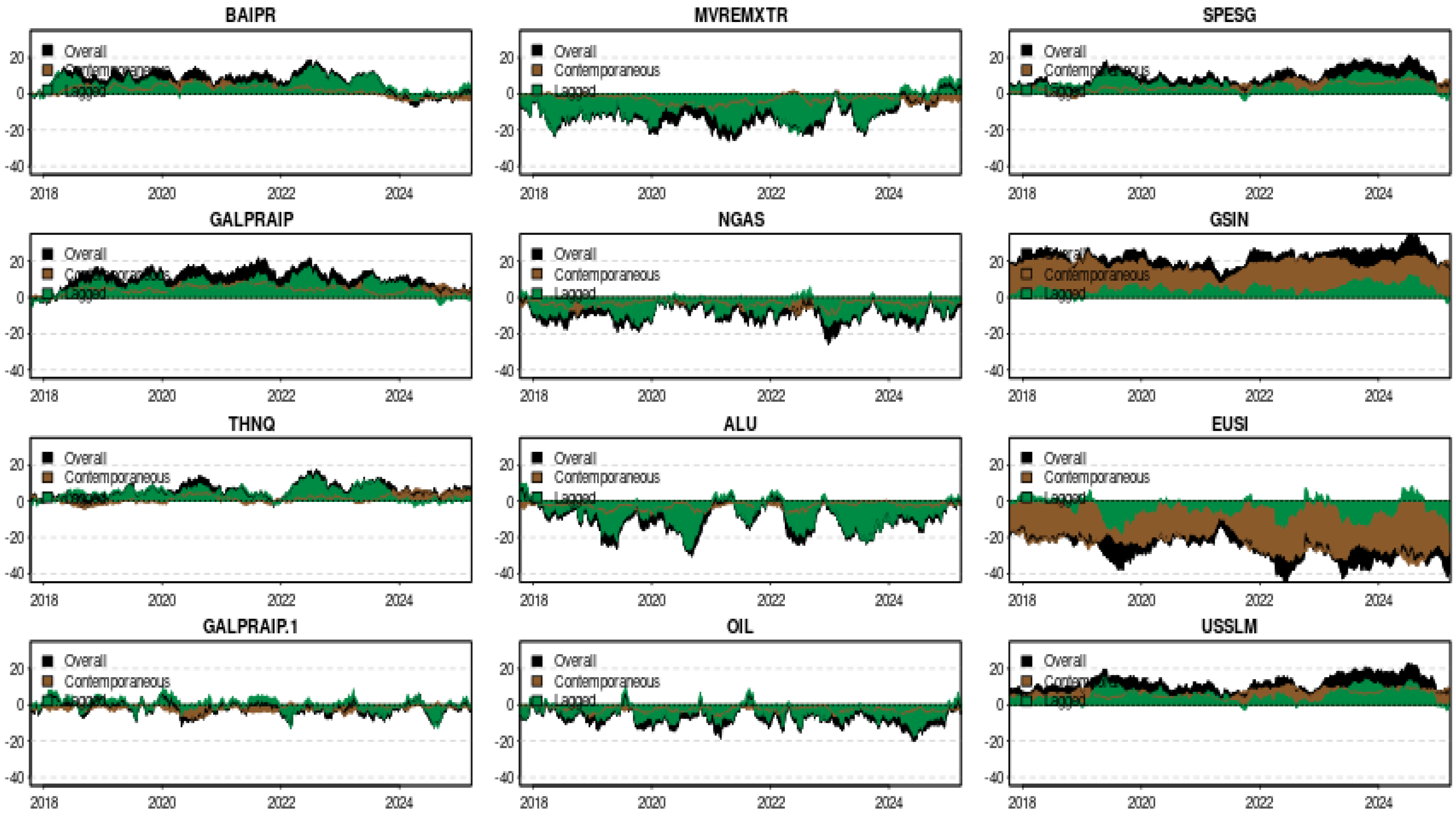

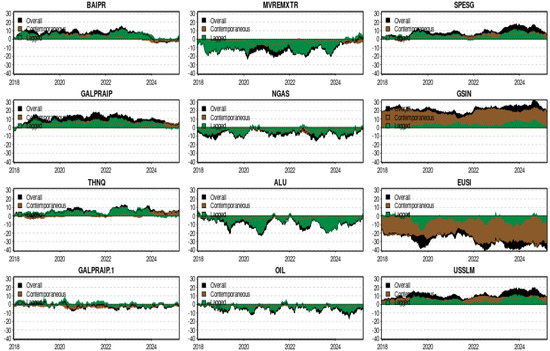

In this study, we articulate the contents of the AI, ESG, and brown market using daily data from 19 March 2017 to 19 March 2025. The top AI markets include Bloomberg US Listed Artificial Intelligence (BAIPR), ECPI Robotics and Artificial Intelligence Index (GALPRAIP), ROBO Global Artificial Intelligence Index (THNQ), and Credit Suisse RavenPack Artificial Intelligence Sentiment Index (GALPRAIP1). The S&P 500 ESG (SPESG), Goldman Sachs Global Environmental Impact Equity Index (GSIN), EU Sustainable Investment Index (EUSI), and US Sustainability Leaders Index (USSLM) represent the top ESG markets. Regardless of the brown market, we consider aluminum, crude oil, Natural Gas, and rare Earths. The time series is extracted from the Bloomberg terminal. Figure 1 depicts the price returns for each data point. To quantify the changes exhibited, we employed the following return formula:

where represents return; is the close price at time

and

, respectively.

Figure 1.

Data trend.

2.2. Approach Estimation

The authors [26] introduced a comprehensive framework for analyzing multiple variables’ dynamics. This allows for connectedness values to extend beyond the traditional [0, 1] range, signaling an unrestricted degree of network interconnectedness. Ref. [27] aimed to overcome the constraint of limited time series in network analysis by introducing unconditional connectedness measures. Their research shows that GFEVD corresponds to the R2 statistic from bivariate regression when VAR coefficients are not statistically significant. Building on earlier research, Ref. [28] incorporated [29] R2 decomposition method and [30] partial correlation network framework into the M-F R2 connectedness approach [27], providing a contemporary R2-decomposed total connectedness. Ref. [31] adopted [28] framework to assess the immediate effects of dynamic total connectedness in distinguishing between these spillovers. The VAR-VAR can be formulated as follows:

In Equation (2), , , and 1 represents the vectors for both the endogenous parameters and the intercept, respectively. are k-dimensional variance covariance. is the state-covariance matrix governing the evolution of coefficients. time-varying intercept. T, and t − 1 is the error term. The GFEVD- can be reformulated as follows:

We proceed by employing the findings from the GFEVD to develop the structure for total connectedness. The net TCI is derived by subtracting the total directional spillovers “FROM” other series from the TCI spillovers “TO” other variables. In the following step, we estimate these two components to calculate TCI.

In Equation (5), we can write as , and in Equation (6), we can reformulate as . The net (NCI) at quantile can be written as follows:

denoted as , is bounded between 0 and 1.

- Hedging Analysis

In this study, we perform a hedging analysis, which is crucial for making investment decisions. Hedge Ratios (HR) methodology proposed by Kroner and Sultan [32], which is as follows:

where is represented by asset A index at time t. denotes the variance of market returns. Hedge effectiveness is calculated following the methodology outlined, as follows:

where is the variance of the hedged portfolio resulting from the , and is the variance of the unhedged investment position. i.e., hedge effectiveness, is the unhedged position’s variance.

To enhance transparency and comparability, we calculated the MCO, MCP, and MVP frameworks. Portfolios are rebalanced monthly, consistent with the frequency in [33]. Transaction costs are assumed to be zero in the baseline, with sensitivity checks using proportional costs of 5–10 bps per rebalancing. For validation, we compute out-of-sample rolling performance using expanding-window forecasts and compare MCoP results against two standard benchmarks under identical constraints: (i) the Minimum Variance Portfolio and (ii) the Minimum Correlation Portfolio. This ensures that performance differences stem from the connectedness-based objective and not from differing optimization assumptions.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation

This section outlines the initial results from the summary statistics analysis presented in Table 1. The analysis includes 2087 observations per data series. The mean values of all series are approximately zero, with negative skew, except for oil prices, natural gas, and rare earth, which have positive skew. Median values are closely aligned with their respective means and have moderately low standard deviations. The time-series data reveals negative returns at their lowest levels, illustrating the impact of financial volatility across different periods. The kurtosis coefficients indicate excess kurtosis, with values exceeding 3, suggesting a deviation from normality. Moreover, all series satisfy the JB test criteria but do not conform to normal distributions, as indicated by significant p-values at the 99% confidence level, confirming the non-normality of the distributions across the series. The Elliott–Rothenberg–Stock (ERS) unit-root test [34] rejects the null of a unit root for every index at the 1% level, indicating that all return series are stationary, as expected for daily financial returns. Third, the Q(10) Ljung–Box test shows significant autocorrelation in several series.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistic.

The correlation analysis presented in Table 2 reveals several significant relationships among AI, ESG, and brown market indices. Strong positive correlations are observed within the AI cluster, particularly between BAIPR and GALPRAIP (0.889) and between BAIPR and THNQ (0.910), indicating a high degree of co-movement among AI-driven assets. Similarly, ESG indices show strong internal coherence: SPESG is highly correlated with USSLM (0.992) and GSIN (0.953), and GSIN and USSLM are also nearly perfectly correlated (0.962). The very high correlations observed among several AI and ESG indices (e.g., SPESG–USSLM: 0.992; GSIN–USSLM: 0.962) reflect the fact that these indices are constructed from overlapping components, share similar screening methodologies, and exhibit synchronized market reactions. Many ESG benchmarks share common constituents and factor exposures (large-cap US equities, sustainability ratings, low-carbon criteria), which naturally leads to strong co-movement. Similarly, AI indices share many technology-intensive firms, leading to common factor structures and high correlations. These high correlations do not imply redundancy but rather reflect the inherent components of thematic index design. In contrast, brown assets such as natural gas, aluminum, and oil exhibit weak and negligible correlations with both AI and ESG indices, typically below 0.10. Moderate correlations are observed between the rare earth index (MVREMXTR) and specific AI indices, such as GALPRAIP (0.458) and THNQ (0.402), suggesting that AI technologies depend on rare earth elements.

Table 2.

Correlation results.

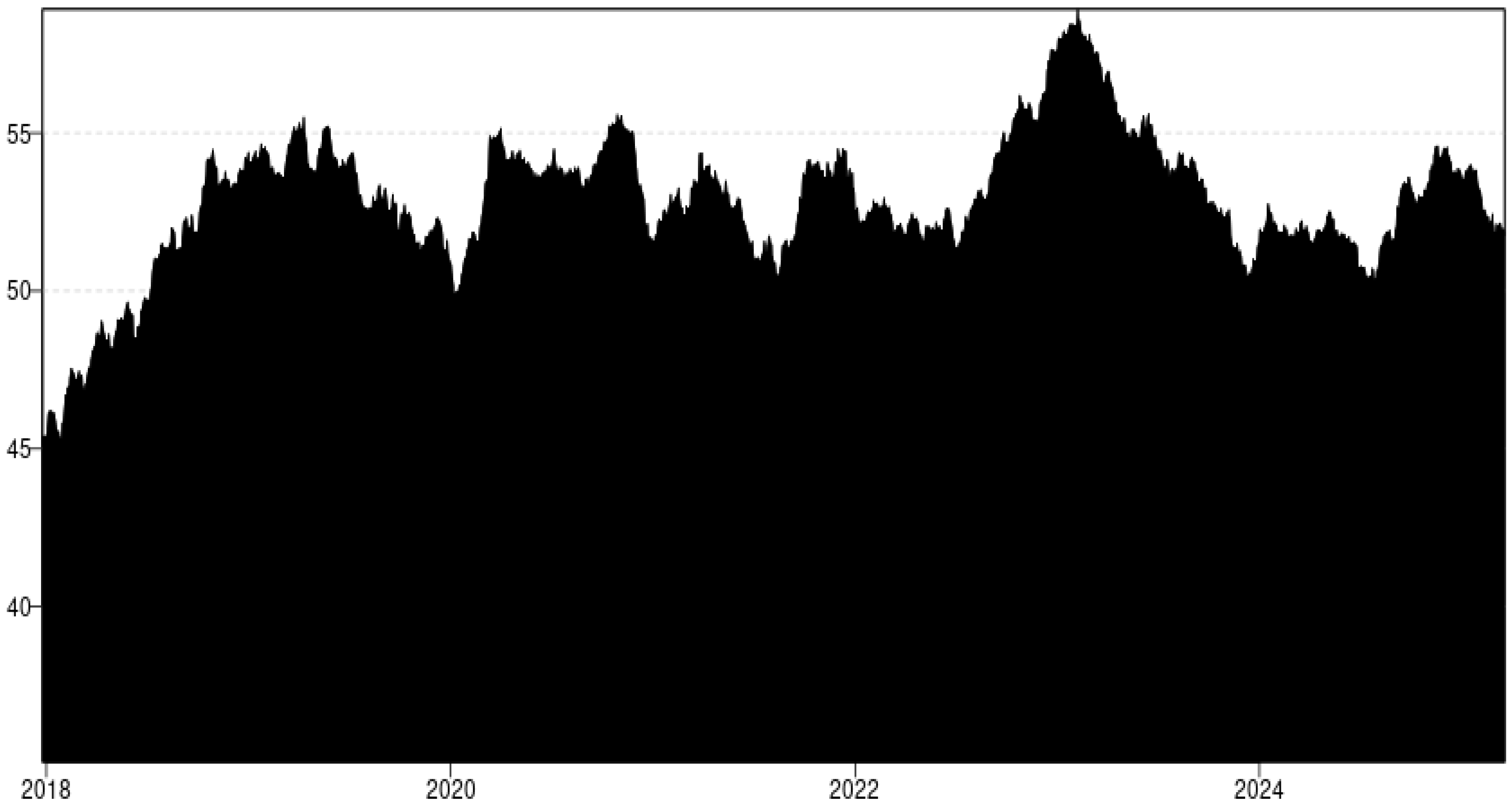

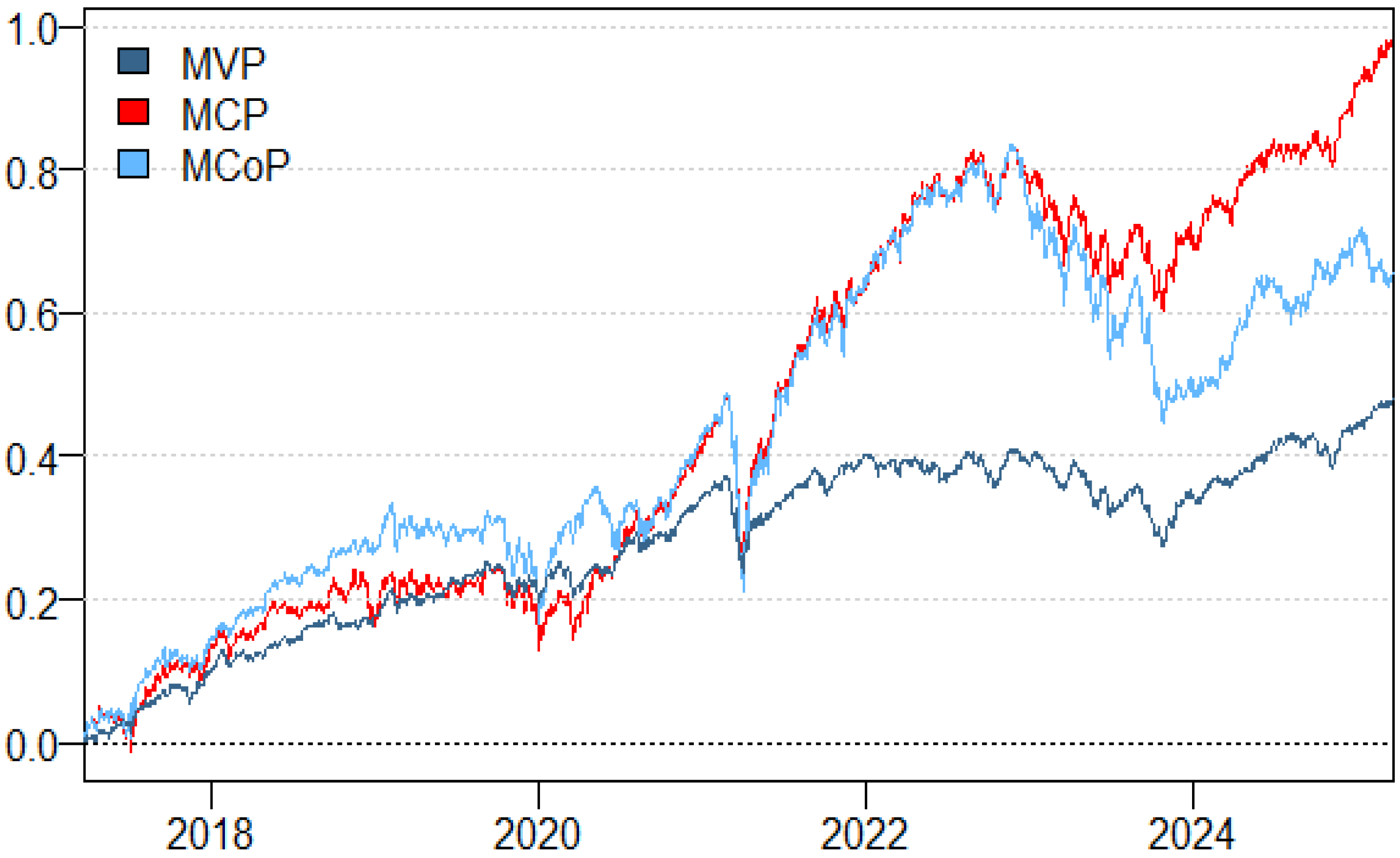

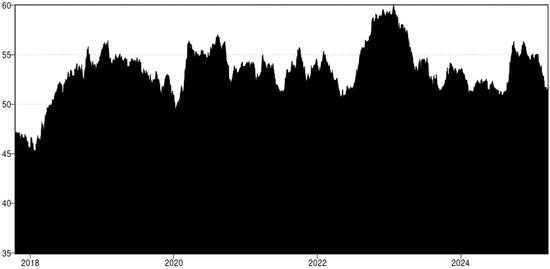

3.2. Findings of the TCI and R2 Decomposed

While the dynamic connectedness patterns often coincide with major geopolitical and market events, the empirical design of the R2 connectedness framework remains associational rather than causal. To strengthen identification, we incorporated additional empirical checks, including structural break tests, event-window indicators for key episodes (COVID-19, Russia–Ukraine conflict, Red Sea tensions, U.S.–China trade shocks), and dummy-variable specifications to confirm whether connectedness shifts coincide with these episodes. We also report confidence intervals for the TCI and the decomposed measures, and re-estimate the model under alternative rolling windows and Kendall-based connectedness as robustness checks. Figure 2 presents the outcomes of the R2 model-free connectedness. From 2018 to early 2020, integration steadily increased from approximately 44% to roughly 55%, signaling growing integration, potentially driven by increased investments and a focus on AI and ESG relative to traditional sectors. In mid-2020, a sharp spike coinciding with the COVID-19 crisis exhibited heightened interrelation as markets collectively reacted to economic uncertainties. Subsequently, integration moderately declined until early 2022, when it peaked again amid the Russia-Ukraine conflict, reaching its highest level (around 58%). However, towards late 2023 and throughout 2024 and early 2025, integration gradually rose to 55%, reflecting intensified interactions amongst markets, driven by heightened focus on climate-centered monetary policies implemented by major central banks and the Second Trump administration, and accentuated by a de-escalation of US climate commitments. This funding corroborates the prior study [19,35], which found that AI Market was the transmitter of the shock.

Figure 2.

The TCI results using the Pearson connectedness.

The observed time evolution of the R2-based total connectedness index demonstrates the evolving nature of systemic integration between AI, ESG, and brown markets. Instead of showing a stationary behavior, the connectedness varies according to changes in economic regimes, policy shocks, and investor sentiment. These fluctuations highlight the fragility of modern financial markets to macro-financial disturbances and technological shocks. Most interestingly, we found stronger connections towards the end of the sample, which indicates a structural change in the organization of these markets. The increasing level of integration is a sign that AI and ESG are moving away from being discrete thematic investments and are becoming part of the mainstream financial landscape. Their involvement in information dissemination, particularly in crisis situations, makes them an early indicator of systemic risk. These results confirm the new role of emerging and sustainable markets in the volatile time [36,37,38]. The dissection of connectedness also reinvigorates the asymmetry in shock transmission. AI-hubs, in any case, operate as early conductors of volatility, as they respond relatively sensitively to innovation cycles/risk appetite. Brown markets, particularly in fossil fuels, serve as volatility receivers, reabsorbing shocks triggered by tech-driven and regulatory disruptions. This asymmetry has significant implications for portfolio allocation: on the one hand, AI and ESG may offer hedging potential at different phases; on the other hand, as net spillover sources, they may also exacerbate systemic risks when uncertainty increases. We also observe a resurgence of climate policy uncertainty under Donald Trump’s return to mainstream politics and deregulation language since late 2023, in turn driving a fresh wave of cross-market integration waves [39]. These findings align with [40,41], who emphasize that Trump’s deregulatory stance increases climate policy uncertainty, disproportionately affecting green firms while temporarily favoring polluting sectors. Our results extend this by showing that political shifts, such as Trump’s resurgence, intensify systemic volatility and integration across AI, ESG, and brown markets. From a broader perspective, the findings suggest that diversification across AI, ESG, and brown assets is increasingly limited, especially following global crises that necessitate more dynamic, regime-conscious investment strategies. We also find that the secular shift in integration points to an increasingly tight coupling between climate-based and technological narratives in financial markets, consistent with recent policy changes and the changing composition of investor demand [42].

Before estimating the dynamic connectedness, we determined the optimal lag structure of the R2-connectedness model. Following [28,31], we selected the lag order by minimizing a combination of AIC, BIC, and HQ criteria in the underlying TVP-VAR structure. All criteria converged to a single optimal lag of one (lag = 1), indicating that additional lags do not improve explanatory power and may introduce unnecessary parameterization, especially under time-varying estimation. The dynamic connectedness measures are computed using a 200-observation rolling window in the baseline specification, and robustness checks are performed with a 150-day rolling window. The forecast horizon is consistently defined as a 10-step-ahead horizon, and references to “40-variate ahead” in early drafts are corrected to reflect 40-step-ahead robustness checks rather than the VAR’s dimensionality. Step-ahead refers to the forecast horizon, and “rolling window length” refers to the number of daily observations used in each estimation window. Therefore, the R2 model is estimated with one lag, consistent with the literature and with the dynamic structure of daily financial returns. Alongside the time-varying R2-connectedness, we computed the full-sample connectedness matrix to provide a benchmark. The results confirm that AI assets are the strongest transmitters of shocks, ESG indices act as moderate net transmitters, and brown commodities (oil, natural gas, aluminum, and rare earth) function as net receivers. These spillover patterns are consistent with the dynamic results, validating the robustness of the findings and confirming that the inclusion of time variation does not distort the underlying structure of cross-market dependencies.

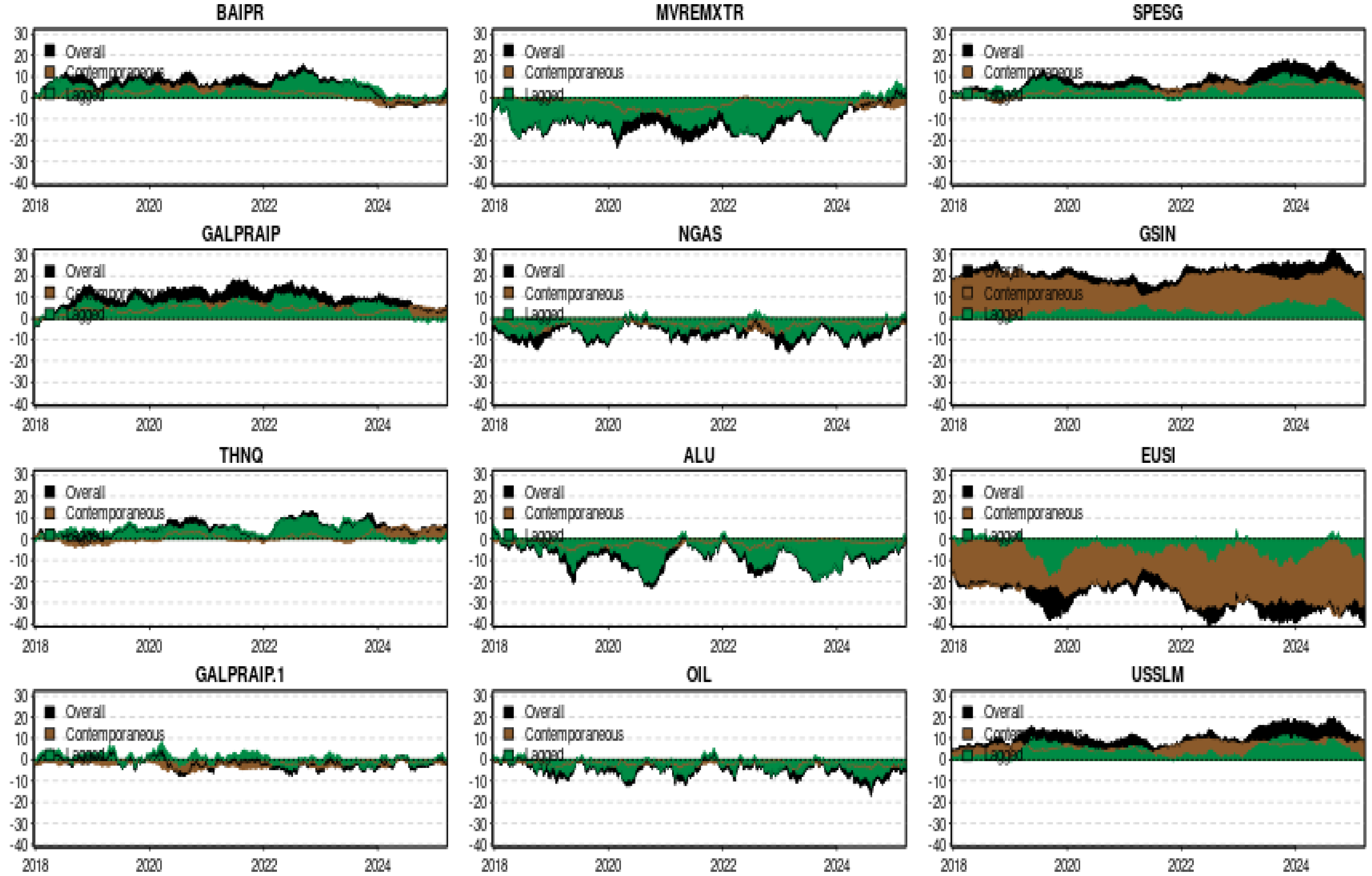

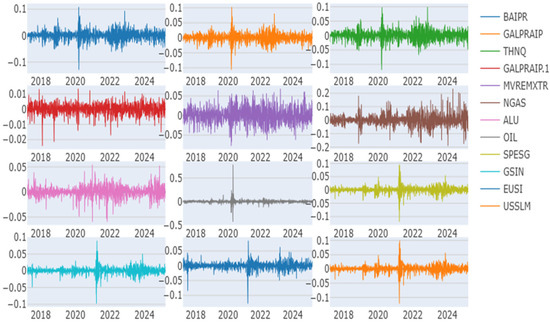

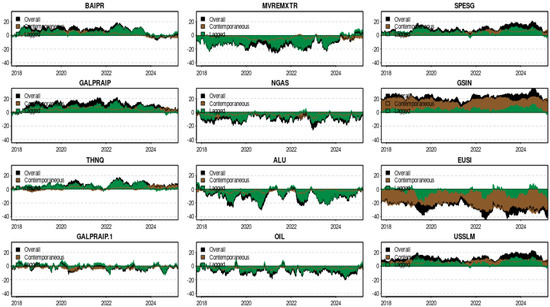

Figure 3 presents the decomposition connectedness, which quantifies the degree of association among the series. The black color represents the overall interconnectedness of various time-varying variables, while the brown and green colors represent contemporaneous and lagged relationships, respectively.

Figure 3.

TCI, contemporaneous, and lagged measures.

Specifically, the overall AI market is the primary transmitter of shocks, followed by the ESG market. Conversely, the brown market appears to be the primary recipient of information. Further analysis, breaking down this metric into its contemporaneous and lagged components, reveals induced spillover effects originating predominantly from the AI sector over the ESG market. For instance, the overall measure of BIAPR transmits approximately 11.6% to 20% of the information to the system during extreme market conditions. Similarly, GALPRAIP and EUSI transmit about 16% and 8%, respectively. Between 6% and 10% of the remaining variation in oil and aluminum can be attributed to the system’s reception. Rare earths are the largest commodity traded on the brown market, with a decline of about −18% over time. Notably, the connectedness indices for ESG markets serve as the primary transmitters of information for most of the period.

AI and the traditional market are predominantly connected by contemporaneous connectedness, as evidenced by the green color. At the same time, ESG shows the highest lagged connectedness, as indicated by the brown color. The prevalence of contemporaneous spillovers from AI markets indicates that they are relatively rapid in their responsiveness to innovation and investor sentiment and, therefore, shortsighted, to the point of being sensitive to short-term shocks. In contrast, ESG markets exhibit stronger lagged connectedness, capturing their sensitivity to slower-moving forces such as regulatory changes, sustainability reporting, and reputational change. The temporal asymmetry suggests that AI can be taken as a leading indicator, whereas ESG remains a lagging yet stubborn driver, providing investors with different tools to collate their short- and medium-term portfolio strategies, especially for carbon-sensitive assets. Markets such as AI are characterized by fast-paced technological progress, real-time investors’ sentiment, and algorithmic trading. These traits prompt AI-themed assets to instantly react to advances in economic news, policy measures, and innovation. Moreover, AI shares can be driven by speculative money, driven by hype cycles, positive media coverage, and earnings beats. That drives instant repricing, which spills over into other markets, such as ESG or brown assets. The brown market remains the lagging recipient of volatility, due to its reliance on structural mechanisms, slower policy dynamics, and less speculative investor base.

3.3. Robustness Check

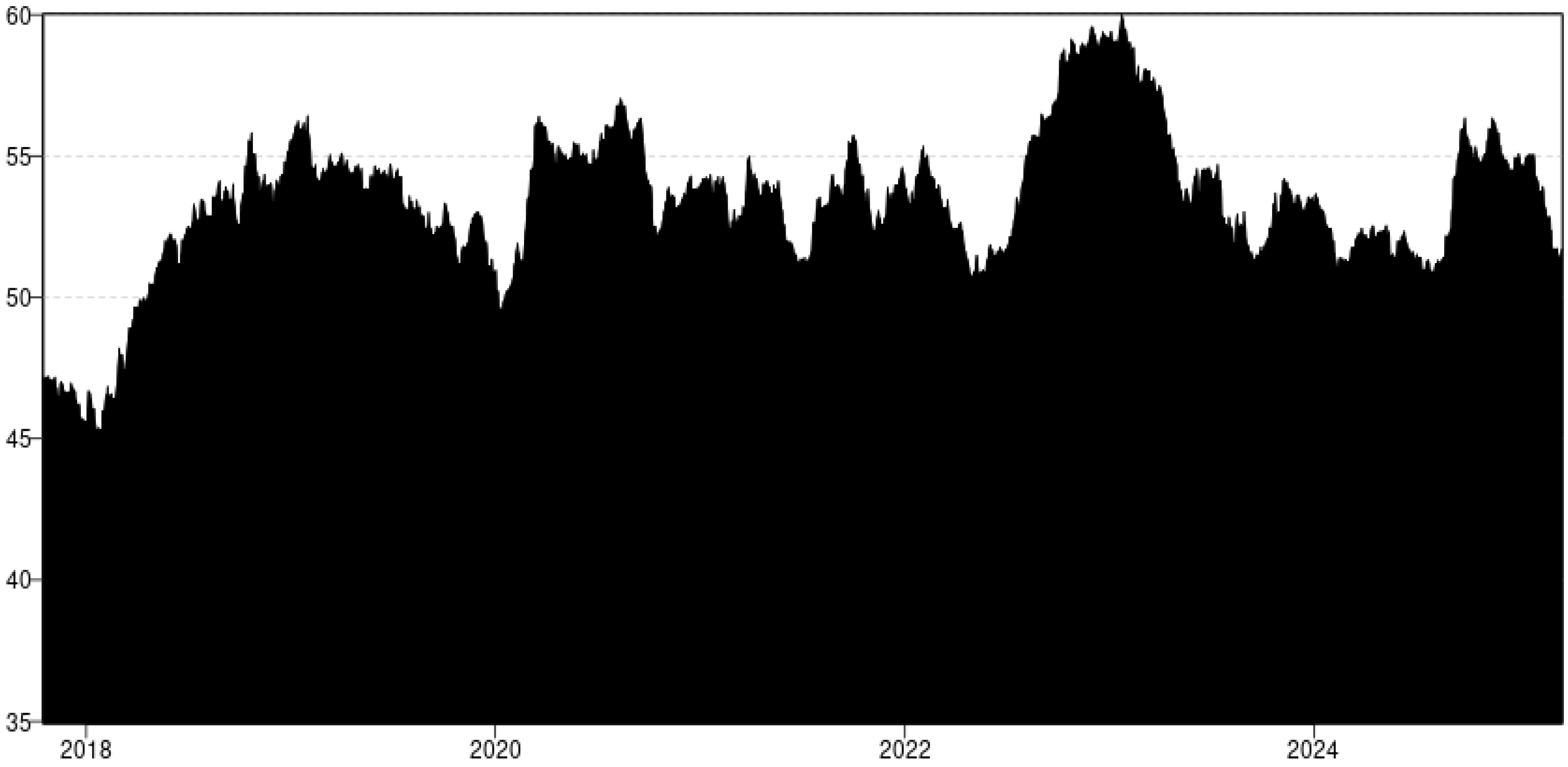

Figure 4 and Figure 5 present an in-depth evaluation of the robustness of the findings using TCI and its decomposition. The Kendall rank connectedness coefficients are employed instead of the Pearson connectedness coefficients to further the rolling windows of 150 and 40-variate ahead forecast, rather than 200 rolling windows and 10-variate ahead forecast. The quantitative similarities in the results suggest that the empirical evidence is robust. The analysis further confirms that the series under examination reaches its peak TCI and the contemporaneous and lagged R2 decomposed connectedness, corroborating earlier findings.

Figure 4.

The TCI uses the Kendall rank connectedness.

Figure 5.

Net TCI, contemporaneous, and lagged measures using the Kendall rank.

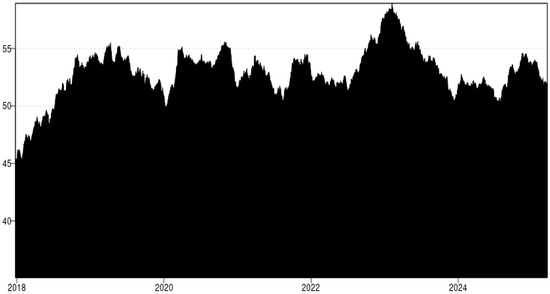

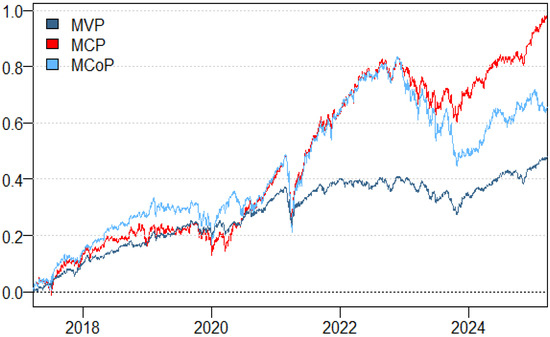

3.4. HE and Portfolio Strategies

Figure 6 and Table 2 demonstrate that we implement dynamic optimal portfolio strategies and hedge ratios. We first delve into an alternative criterion, specifically cumulative returns, to evaluate the performance of various portfolio strategies (See Figure 4). According to a recent study, the time evolution of cumulative returns for the Minimum Variance Portfolio (MVP), Minimum Correlation Portfolio (MCP), and Minimum Connectedness Portfolio (MCoP) shows that the MCoP consistently achieves higher cumulative returns during the period 2017–2021. Then, the MCoP achieves a high value during 2022–2025, demonstrating that MCoP provides an effective portfolio allocation strategy.

Figure 6.

The optimal portfolio strategy results.

Table 3 presents portfolio management using asset HE. The AI and ESG markets can effectively hedge against brown markets, especially under high-volatility market conditions. For instance, natural gas indexed against BAIPR, GALPRAIP, and THNQ exhibited statistically significant hedging effectiveness of approximately 22%, 21%, and 22%, respectively, with p-values of 0. For all three, the hedging effectiveness was approximately 22%. Similarly, crude oil achieved a 28–29% risk reduction when paired with BAIPR, GALPRAIP, and THNQ, a highly significant effect. Especially for rare earths, pairing with AI and ESG indexes such as BAIPR, GALPRAIP, THNQ, and SPESG delivered substantial, statistically robust risk mitigation. ESG benchmarks such as SPESG, GSIN, and EUSI saw negligible volatility reductions from hedging with brown commodities. On the contrary, when examining whether AI indices like BAIPR, GALPRAIP, and THNQ could hedge brown commodities such as oil, natural gas, aluminum, and rare earth, the efficacy was consistently low and statistically insignificant. These results indicate that investors focused on traditional markets could meaningfully diversify their portfolios by incorporating AI and ESG assets to mitigate volatility. In contrast, those focused solely on AI or ESG gain limited practical benefits from integrating traditional commodities, underscoring the independence of emerging technologies and the importance of responsible governance in markets.

Table 3.

HE results.

4. Conclusions

This study concluded that AI and ESG markets convey information on risk and volatility to brown markets, particularly during extreme market conditions. Using AI and ESG assets as hedges could yield a substantial decrease in volatility for brown-market assets, thereby demonstrating their hedging capacity. These results have significant implications for the performance of fund managers, institutional investors, and financial regulators. Firstly, for fund managers, the evidence indicates that incorporating AI/ESG assets into portfolio construction can provide a substantial hedge against conventional brown market volatility, especially during times of high market stress. Better performance of the MCoP indicates that minimizing cross-asset contagion tends to yield a strategic gain for an investor in terms of portfolio optimization and risk-adjusted returns. The second is that investors can do well, financially, by doing good, since the findings show the financial value of investing in AI and ESG markets, not just for ethical and sustainability reasons. Investing in clean, carbon-aware assets is also an effective way to hedge against systemic shocks from carbon-intensive sectors. Third, decision-makers are recommended to create an environment conducive to promoting the evolution and implementation of AI technologies and ESG practices. Regulation that encourages data transparency, carbon disclosure, and the standardization of ESG metrics can accentuate the stabilizing effect these markets can have. Supporting the adoption of AI-empowered analytics tools in the investment process could also enhance market efficiency and strengthen its resilience. In general, a combination of innovation, sustainable finance, and regulation works together to stabilize finance as we transition globally to a lower-carbon economy. Although this study offers fresh insights into dynamically linked relationships and portfolio tactics among AI, ESG, and brown markets, limitations remain. First, the study is based on daily price data, capturing short-term market trends but perhaps missing intraday and semivariance analysis. Second, the analysis focuses on a particular range of indices, which, although fairly representative, is unlikely to capture all the heterogeneity across AI, ESG, and brown asset classes across regions and sectors. Finally, the analysis includes financial climate risks through market indices, but does not consider explicit climate scenarios and future regulation that could drive investor expectations. Future research could expand the data set with sector- and region-specific ESG and AI indices, enabling a more nuanced discussion of cross-market spillovers and hedging behavior across different economic environments. Moreover, prospective studies could include forward-looking climate risk metrics, such as scenario-based projections developed by the Network for Greening the Financial System, as well as transition risk measures from climate stress-testing exercises. Furthermore, future research could explore the influence of emerging technologies (e.g., blockchain, quantum computing, and green fintech) on the connectedness and the transfer of risk between the sustainable and conventional markets. Finally, qualitative studies focusing on investor sentiment, policy responses, and the parallel identification of institutional barriers and reasons for adopting policy to support the alignment of financial markets with climate/innovation objectives could provide a sense of the nuances behind the quantitative findings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.S.M.; Software, K.S.M.; Writing—original draft, S.B.A.; Writing—review & editing, K.S.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Khalid University for funding this work through large group Research Project under grant number RGP2/570/46.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings will be available in Bloomberg terminal at https://www.bloomberg.com/professional/products/bloomberg-terminal/ (accessed on 31 August 2025) following an embargo from the date of publication to allow for commercialization of research findings.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Khalid University for funding this work through large group Research Project under grant number RGP2/570/46.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Economides, G.; Xepapadeas, A. Monetary policy stabilization in a new Keynesian model under climate change. Rev. Econ. Dyn. 2023, 56, 101260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Z.; Yu, B.; Lam, K.S.K.; Yu, B.; Lam, K.S.K. Does ESG explain stock returns? Evidence from Chinese stock markets. Financ. Res. Lett. 2025, 79, 107214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacherjee, P.; Mishra, S.; Bouri, E. Does asset-based uncertainty drive asymmetric return connectedness across regional ESG markets? Glob. Financ. J. 2024, 61, 100972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dongo, D.F.; Relvas, S. Evaluating the role of the oil and gas industry in energy transition in oil-producing countries: A systematic literature review. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2025, 120, 103905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Hamori, S. Portfolio implications based on quantile connectedness among cryptocurrency, stock, energy, and safe-haven assets. J. Commod. Mark. 2025, 39, 100494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Olmo, J.; Atwi, M. High-dimensional multi-period portfolio allocation using deep reinforcement learning. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2025, 98, 103996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Dai, X.; Wang, Q. Do green assets enhance portfolio optimization? A multi-horizon investing perspective. Br. Account. Rev. 2025, 57, 101612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, M.B.; Galariotis, E.; Guesmi, K.; Hamdi, H.; Naoui, K. Diversification in financial and crypto markets. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2023, 89, 102785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshammari, S.; Serret, V.; Tiwari, S.; Si Mohammed, K. Industry 4.0 and AI amid economic uncertainty: Implications for sustainable markets. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2025, 75, 102773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eleuch, M.; Souissi, N.; Mroua, M. Does the crisis period affect the properties of various financial assets: Evidence from G7, BRIC, GCC countries. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2025, 12, 2451132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubbaniy, G.; Maghyereh, A.; Cheffi, W.; Khalid, A.A. Dynamic connectedness, portfolio performance, and hedging effectiveness of the hydrogen economy, renewable energy, equity, and commodity markets: Insights from the COVID-19 pandemic and the Russia-Ukraine war. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 452, 142217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baur, D.G.; Lucey, B.M. Is gold a hedge or a safe haven? An analysis of stocks, bonds and gold. Financ. Rev. 2010, 45, 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urom, C.; Ndubuisi, G.; Guesmi, K.; Benkraien, R. Quantile co-movement and dependence between energy-focused sectors and artificial intelligence. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 183, 121842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, T.L.D.; Hille, E.; Nasir, M.A. Diversification in the age of the 4th industrial revolution: The role of artificial intelligence, green bonds and cryptocurrencies. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2020, 159, 120188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.L.; Abakah, E.J.A.; Tiwari, A.K. Time and frequency domain connectedness and spill-over among fintech, green bonds and cryptocurrencies in the age of the fourth industrial revolution. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 162, 120382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, S.; Pang, L.; Li, X.; Huang, L. The dynamic connectedness in the “carbon-energy-green finance” system: The role of climate policy uncertainty and artificial intelligence. Energy Econ. 2025, 143, 108241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, M.P.; Abedin, M.Z.; Sinha, N.; Arya, V. Uncovering dynamic connectedness of Artificial intelligence stocks with agri-commodity market in wake of COVID-19 and Russia-Ukraine Invasion. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2024, 67, 102146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chishti, M.Z.; Dogan, E.; Binsaeed, R.H. Can artificial intelligence and green finance affect economic cycles? Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 209, 123740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abakah, E.J.A.; Tiwari, A.K.; Ghosh, S.; Doğan, B. Dynamic effect of Bitcoin, fintech and artificial intelligence stocks on eco-friendly assets, Islamic stocks and conventional financial markets: Another look using quantile-based approaches. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2023, 192, 122566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adekoya, O.B.; Oliyide, J.A.; Saleem, O.; Adeoye, H.A. Asymmetric connectedness between Google-based investor attention and the fourth industrial revolution assets: The case of FinTech and Robotics & Artificial intelligence stocks. Technol. Soc. 2022, 68, 101925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arfaoui, N.; Benammar, R.; Obeid, H.; SI Mohammed, K. Exploring the interconnections between oil price uncertainty and the European renewable energy sector in wartime. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2026, 81, 103184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.H.; Shao, Y.H.; Zhou, W.X. Contemporaneous and lagged spillovers between agriculture, crude oil, carbon emission allowance, and climate change. Financ. Res. Lett. 2025, 71, 106374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, L.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Lucey, B.M. Diversification effects of China’s carbon neutral bond on renewable energy stock markets: A minimum connectedness portfolio approach. Energy Econ. 2023, 123, 106727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, T.; Bouri, E.; Vo, X.V. Hedging strategies of green assets against dirty energy assets. Energies 2020, 13, 3141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, L.; Chen, M.; Luo, W.; Yang, W. Do climate policy uncertainty, green finance, and the energy market matter for carbon price? Evidence from China. Energy Rep. 2025, 14, 1814–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diebold, F.X.; Yilmaz, K. On the network topology of variance decompositions: Measuring the connectedness of financial firms. J. Econom. 2014, 182, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabauer, D.; Chatziantoniou, I.; Stenfors, A. Model-free connectedness measures. Financ. Res. Lett. 2023, 54, 103804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, M.A.; Chatziantoniou, I.; Gabauer, D.; Karim, S. Measuring the G20 stock market return transmission mechanism: Evidence from the R2 connectedness approach. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2024, 91, 102986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genizi, A. Decomposition of R2 in multiple regression with correlated regressors. Stat. Sin. 1993, 3, 407–420. [Google Scholar]

- Kenett, D.Y.; Huang, X.; Vodenska, I.; Havlin, S.; Stanley, H.E. Partial correlation analysis: Applications for financial markets. Quant. Financ. 2015, 15, 569–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balli, F.; Balli, H.O.; Dang, T.H.N.; Gabauer, D. Contemporaneous and lagged R2 decomposed connectedness approach: New evidence from the energy futures market. Financ. Res. Lett. 2023, 57, 104168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroner, K.F.; Jahangir, S. Time-Varying Distributions and Dynamic Hedging with Foreign Currency Futures. J. Financ. Quant. Anal. 1993, 28, 535–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broadstock, D.C.; Chatziantoniou, I.; Gabauer, D. Minimum Connectedness Portfolios and the Market for Green Bonds: Advocating Socially Responsible Investment (SRI) Activity. In Applications in Energy Finance: The Energy Sector, Economic Activity, Financial Markets and the Environment; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 217–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, G.; Rothenberg, T.J.; Stock, J.H. Efficient Tests for an Autoregressive Unit Root; NBER Technical Working Paper No. 130; NBER: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Ben Jabeur, S.; Gozgor, G.; Rezgui, H.; Mohammed, K.S. Dynamic dependence between quantum computing stocks and Bitcoin: Portfolio strategies for a new era of asset classes. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2024, 95, 103478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantero-Saiz, M.; Polizzi, S.; Scannella, E. ESG and asset quality in the banking industry: The moderating role of financial performance. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2024, 69, 102221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marszk, A.; Lechman, E. What drives sustainable investing? Adoption determinants of sustainable investing exchange-traded funds in Europe. Struct. Change Econ. Dyn. 2024, 69, 63–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseer, M.M.; Guo, Y.; Bagh, T.; Zhu, X. Sustainable investments in volatile times: Nexus of climate change risk, ESG practices, and market volatility. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2024, 95, 103492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elder, M.; Zusman, E.; Hengesbaugh, M. Why the Second Trump Administration Could Struggle to Undermine Domestic Climate Policies: Obstacles to Backsliding; Institute for Global Environmental Strategies: Kanagawa, Japan, 2025; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, S.; Wang, A.; Cui, T.; Du, A.M. Renaissance of climate policy uncertainty: The effects of U.S. presidential election on energy markets volatility. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2025, 98, 103866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belhouichet, F.; Caporale, G.M.; Gil-alana, L.A. Energy Transition and Climate Policy Uncertainty in the US: Green Versus Polluting Firms; CESifo: Munich, Germany, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Hossain, M.R.; Ben Jabeur, S.; Si Mohammed, K.; Shahzad, U. Time-varying relatedness and structural changes among green growth, clean energy innovation, and carbon market amid exogenous shocks: A quantile VAR approach. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 208, 123705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).