Contracted Land Assets and Rural Labor Transfer: Unlocking the Potential for Sustainable Urbanization Through Total Income of Agricultural Products

Abstract

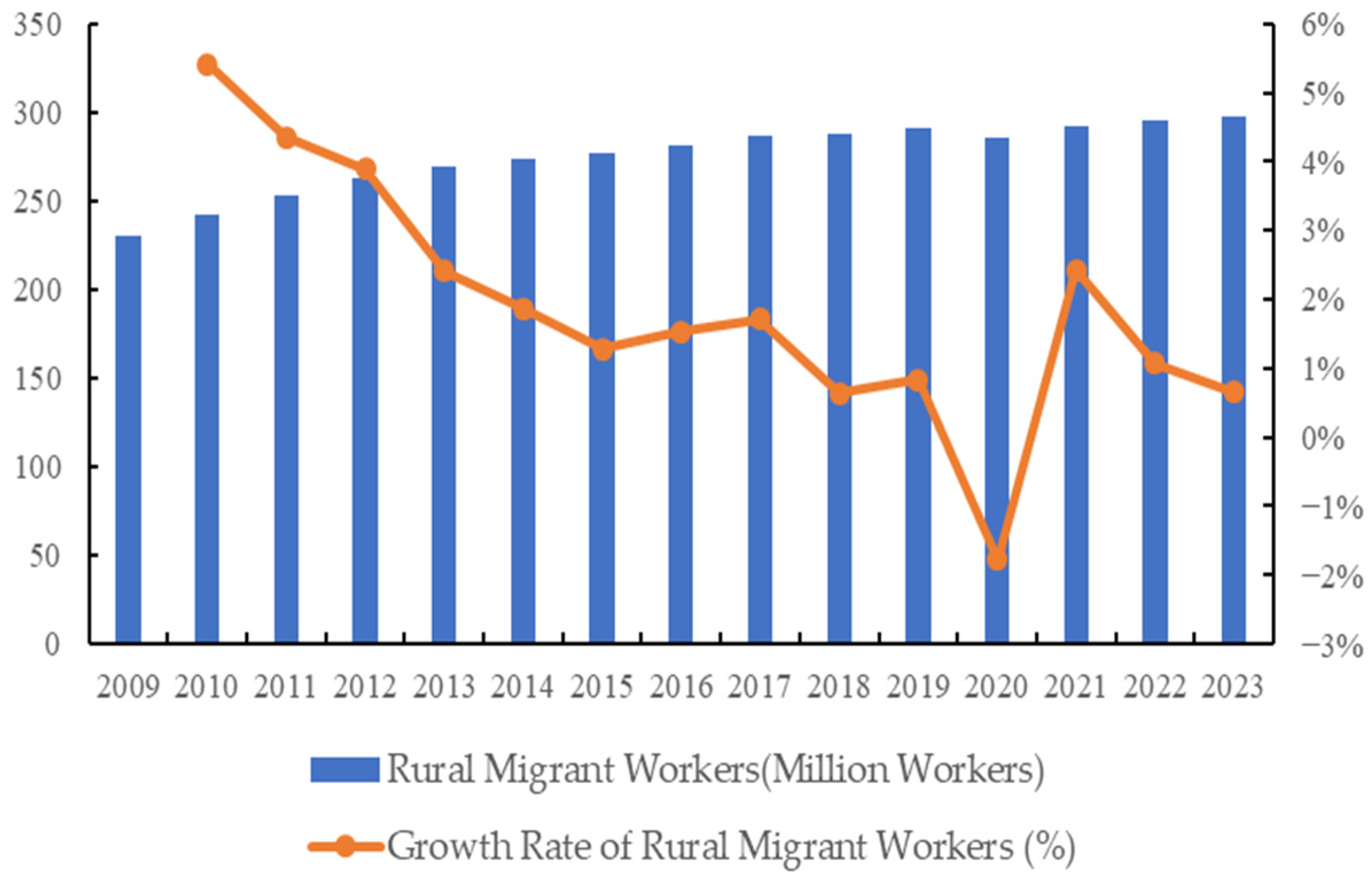

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Conceptual Definition of Rural Contracted Land Assets and Rural Labor Transfer

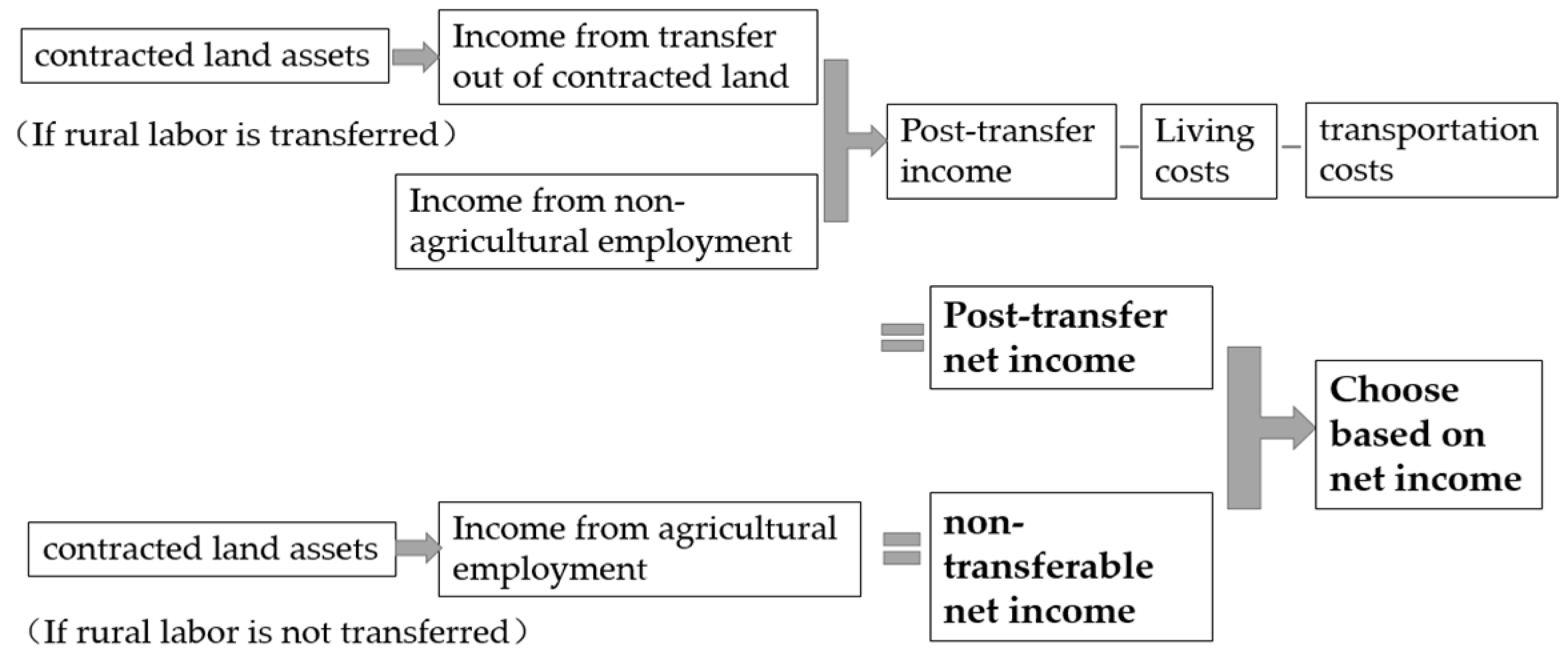

2.2. Theoretical Framework for the Impact of Rural Contracted Land Assets on Rural Labor Transfer and Its Mechanism

3. Research Design

3.1. Data Sources

3.2. Variable Description

3.2.1. Selection and Measurement of Dependent Variables

3.2.2. Selection of Independent Variables

3.2.3. Selection of Control Variables

3.2.4. Explanation of Mediating Variables and Moderating Variables

3.3. Model Setting

4. Empirical Analysis

4.1. Descriptive Statistical Results

4.2. Basic Analysis of the Impact of Contracted Land Assets on the Rural Labor Transfer

4.3. Robustness Test of the Impact of Contracted Land Assets on Rural Labor Transfer

4.3.1. Robustness Test at the Individual Level

4.3.2. Robustness Test Using Data from 2020 to 2022

4.4. Heterogeneous Analysis of the Impact of Contracted Land Assets on the Transfer of Rural Labor

4.4.1. Analysis of Regional Heterogeneity

4.4.2. Heterogeneity Analysis Based on Distance from Cities

4.5. Addressing the Endogeneity Issue of the Impact of Contracted Land Assets on Rural Labor Transfer

5. Further Analysis

5.1. Mediating Effect Analysis

5.1.1. Analysis of the Mediating Effect of the Transfer in of Contracted Land Area

5.1.2. Analysis of the Mediating Effect of Total Income of Agricultural Products

5.1.3. Analysis of the Mediating Effect of Income from Transfer out of Contracted Land

5.1.4. Analysis of the Mediating Effect of Income from Non-Agricultural Employment

5.2. Moderating Effect Analysis

5.2.1. Moderating Effects of Whether Contracted Land Is Transferred out

5.2.2. The Moderating Effect of Whether the Contracted Land Is Close to the City

5.3. Moderated Mediation Analysis

5.3.1. Suitability for Mechanical Farming

5.3.2. Whether the Farmland Is Fragmented

5.3.3. Quality of Arable Land

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Freeman, R.B. People flows in globalization. J. Econ. Perspect. 2006, 20, 145–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Deng, X.; Guo, S.; Liu, S. Labor migration and farmland abandonment in rural China: Empirical results and policy implications. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 232, 738–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Li, H.; Wang, W.; Zhou, C. Scenario forecast model of long term trends in rural labor transfer based on evolutionary games. J. Evol. Econ. 2015, 25, 649–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Huang, J.; Zhang, L.; Rozelle, S. The rise of migration and the fall of self employment in rural China’s labor market. China Econ. Rev. 2011, 22, 573–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunam, R. In search of pathways out of poverty: Mapping the role of international labour migration, agriculture and rural labour. J. Agrar. Change 2017, 17, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, P.; Du, Y.; Wang, M. Rural labor migration and poverty reduction in China. China World Econ. 2017, 25, 45–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Guo, S.; Xie, F.; Liu, S.; Cao, S. The impact of rural laborer migration and household structure on household land use arrangements in mountainous areas of Sichuan province, China. Habitat Int. 2017, 70, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Chen, C.; Xie, J. Off-farm employment, farmland transfer and agricultural investment behavior: A study of joint decision-making among north China plain farmers. J. Asian Econ. 2024, 95, 101839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Lu, Z. Rural credit input, labor transfer and urban–rural income gap: Evidence from China. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2021, 13, 872–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niebuhr, A.; Granato, N.; Haas, A.; Hamann, S. Does labour mobility reduce disparities between regional labour markets in Germany? Reg. Stud. 2012, 46, 841–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.X.; Benjamin, F.Y. Labor mobility barriers and rural-urban migration in transitional China. China Econ. Rev. 2019, 53, 211–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heberle, R. The causes of rural-urban migration a survey of German theories. Am. J. Sociol. 1938, 43, 932–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauser, P.M.; Duncan, O.D. The Study of Population: An Inventory and Appraisal; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Xingang, W. How can rural digital development activate agricultural land mobility?—Based on the dual perspectives of resource mismatch and labor mobility. Front. Environ. Sci. 2025, 13, 1645180. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y.; Zhuang, J.; Chen, J.; Yang, C.; Kong, M. The impact of farmland transfer on urban–rural integration: Causal inference based on double machine learning. Land 2025, 14, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Cao, S.; Qing, C.; Xu, D.; Liu, S. Does labour migration necessarily promote farmers’ land transfer-in?—Empirical evidence from China’s rural panel data. J. Rural. Stud. 2023, 97, 534–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Rodríguez, S.E. Research on the interaction mechanism between land system reform and rural population flow: Europe (taking Spain as an example) and China. Land 2024, 13, 1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.; Qian, Z.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, T. Rural labor migration and households’ land rental behavior: Evidence from China. China World Econ. 2018, 26, 66–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Yong, Z.; Deng, X.; Zhuang, L.; Qing, C. Rural-urban migration and its effect on land transfer in rural China. Land 2020, 9, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.-D.; Cao, S.; Wang, X.-X.; Liu, S.-Q. Influences of labor migration on rural household land transfer: A case study of Sichuan province, China. J. Mt. Sci. 2018, 15, 2055–2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Song, G.; Sun, X. Does labor migration affect rural land transfer? Evidence from China. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 105096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giles, J.; Mu, R. Village political economy, land tenure insecurity, and the rural to urban migration decision: Evidence from China. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2018, 100, 521–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, D.; Bai, C.; Yan, H.; Song, W. Legal land transfer rights, labor migration and urban–rural income disparity: Evidence from the implementation of China’s rural land contracting law in 2003. Growth Change 2022, 53, 1457–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huangfu, B.; Gao, X.; Shi, X.; Jin, S. Move out of the land: Certification and migration in China. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2024, 51, 927–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, C.; Mi, Y. Land titling and internal migration: Evidence from China. Land Use Policy 2021, 111, 105763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Heerink, N.; Shi, X. Land tenure insecurity and rural-urban migration in rural China. Pap. Reg. Sci. 2016, 95, 383–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, T.; Zhang, X.; Huang, X. Impact of labor transfer on agricultural land use conversion at rural household level based on logit model. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2008, 18, 300–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Zhang, Z.; Lu, X.; Zhang, L. Topographic heterogeneity, rural labour transfer and cultivated land use: An empirical study of plain and low-hill areas in China. Pap. Reg. Sci. 2019, 98, 2157–2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Jiang, Q. Land arrangements for rural–urban migrant workers in China: Findings from Jiangsu province. Land Use Policy 2016, 50, 262–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, P. Relative deprivation and migration in an agricultural setting of Nepal. Popul. Environ. 2004, 25, 475–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, W.; Zhao, G. Agricultural land and rural-urban migration in China: A new pattern. Land Use Policy 2018, 74, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, J.; Larsen, A.; Noack, F. The land use consequences of rural to urban migration. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2024, 106, 177–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanwey, L.K. Land ownership as a determinant of temporary migration in Nang Rong, Thailand. Eur. J. Popul./Rev. Eur. Démographie 2003, 19, 121–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Florkowski, W.J.; Liu, Z. Rural migrant workers in urban China: Does rural land still matter? Land 2025, 14, 901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.; Rahman, M. Impact of land fragmentation and resource ownership on productivity and efficiency: The case of rice producers in Bangladesh. Land Use Policy 2009, 26, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Xu, D.; Liu, Y.; Liu, S. The impact of rural labor migration on elderly health from the perspective of gender structure: A case study in western China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Guan, Y. Does rural labor transfer contribute to the reduction in chemical fertilizer use? evidence from China’s household finance survey data in China. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; He, W.; Liu, Z.J.; Zhang, H. How do property rights affect credit restrictions? evidence from China’s forest right mortgages. Small-Scale For. 2021, 20, 235–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Peng, J.; Zhao, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, C. Reform of agricultural land property rights system and grain production resilience: Empirical evidence based on China’s “three rights separation” reform. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0319387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Rommel, J.; Feng, S.; Hanisch, M. Can land transfer through land cooperatives foster off-farm employment in China? China Econ. Rev. 2017, 45, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, N.; Li, C. Migration and rural sustainability: Relative poverty alleviation by geographical mobility in China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, N.; Luo, X. The impact of migration on rural poverty and inequality: A case study in China. Agric. Econ. 2010, 41, 191–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, Q.; Ni, J.; Ni, D.; Wu, Y. Land acquisition, labor allocation, and income growth of farm households. Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 2016, 52, 1744–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Ma, W.; Guo, Y.; Zhou, X. Interactive relationship between non-farm employment and mechanization service expenditure in rural China. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2022, 14, 84–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, M.; Zhang, W.; Zhu, X.; Shi, Q. Agricultural mechanization and rural worker mobility: Evidence from the agricultural machinery purchase subsidies programme in China. Econ. Model. 2024, 139, 106784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Xie, H.; Yao, G. Impact of land fragmentation on marginal productivity of agricultural labor and non-agricultural labor supply: A case study of Jiangsu, China. Habitat Int. 2019, 83, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.Q.; Van Vu, H. Land fragmentation and household income: First evidence from rural Vietnam. Land Use Policy 2019, 89, 104247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Lu, H. Impact of land fragmentation and non-agricultural labor supply on circulation of agricultural land management rights. Land Use Policy 2017, 68, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, Y. Rural land engineering and poverty alleviation: Lessons from typical regions in China. J. Geogr. Sci. 2019, 29, 643–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witcover, J.; Vosti, S.A.; Carpentier, C.L.; De Araújo Gomes, T.C. Impacts of soil quality differences on deforestation, use of cleared land, and farm income. Environ. Dev. Econ. 2006, 11, 343–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Wang, W.; Gao, L.; Yang, J.; Wang, X.; Wang, P.; Wen, Z. Childhood maltreatment and adolescent cyberbullying perpetration: A moderated mediation model of callous—Unemotional traits and perceived social support. J. Interpers. Violence 2022, 37, NP5026–NP5049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stock, J.H.; Yogo, M. Testing for Weak Instruments in Linear IV Regression; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Tan, S.; Liu, C.; Wang, S. Influence of labor transfer on farmland sustainable development: A regional comparison of plain and hilly areas. Qual. Quant. 2018, 52, 431–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Observation | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | |||||

| Rural Nonfarm Employment | 9918 | 0.425 | 0.406 | 0 | 1 |

| Independent variable | |||||

| Contracted Land | 9918 | 11.408 | 66.191 | 0 | 3750 |

| Control variables | |||||

| Gender (Male = 1) | 9918 | 0.902 | 0.298 | 0 | 1 |

| Age | 9918 | 54.172 | 11.555 | 17 | 96 |

| Education | 9918 | 7.127 | 3.309 | 0 | 16 |

| Political status (party member = 1) | 9918 | 0.106 | 0.307 | 0 | 1 |

| Marital status (have spouse = 1) | 9918 | 0.915 | 0.279 | 0 | 1 |

| Dependency ratio | 9918 | 0.273 | 0.266 | 0 | 1 |

| Healthy population ratio | 9918 | 0.640 | 0.286 | 0 | 1 |

| Pension Ratio | 9918 | 0.673 | 0.394 | 0 | 1 |

| Household Income | 9918 | 8.418 | 2.073 | 0 | 14.039 |

| Eastern Region | 9918 | 0.360 | 0.480 | 0 | 1 |

| Central Region | 9918 | 0.346 | 0.476 | 0 | 1 |

| GDP PC | 9918 | 10.707 | 0.325 | 10.182 | 11.564 |

| Secondary Industry | 9918 | 0.477 | 0.056 | 0.213 | 0.541 |

| Tertiary Industry | 9918 | 0.421 | 0.052 | 0.354 | 0.780 |

| Private Wage | 9918 | 10.405 | 0.149 | 10.171 | 10.876 |

| Private Employment | 9918 | 6.638 | 0.727 | 4.278 | 7.869 |

| Observation | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mediating Variables: | |||||

| Area of land transferred in | 9918 | 2.256 | 13.318 | 0 | 400 |

| Total income from | |||||

| agricultural products | 9918 | 8980.204 | 53,986.220 | 0 | 3,000,000 |

| Moderating Variables (for | |||||

| independent variable): | |||||

| Land Transfer (transferred out = 1) | 9918 | 0.100 | 0.301 | 0 | 1 |

| Moderating Variables (for mediating variable): | |||||

| mechanization (arable land is suitable for mechanization = 1) | 8726 | 1.471 | 0.499 | 1 | 2 |

| Number of cultivated plots | 1207 | 5.314 | 5.360 | 1 | 80 |

| quality of arable land (1 = very good) | 8724 | 2.710 | 0.992 | 1 | 5 |

| Rural Labor Transfer | Rural Labor Transfer | Rural Labor Transfer | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model (1) | Model (2) | Model (3) | |

| Contracted land assets (ln) | −0.128 *** | −0.125 *** | −0.110 *** |

| (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.004) | |

| gender | −0.047 *** | −0.049 *** | −0.045 *** |

| (0.014) | (0.013) | (0.013) | |

| age | −0.005 ** | −0.015 *** | −0.015 *** |

| (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | |

| age_squ | 0 | 0.000 *** | 0.000 *** |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| edu | 0.009 *** | 0.006 *** | 0.006 *** |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| Political status | 0.049 *** | 0.047 *** | 0.044 *** |

| (0.013) | (0.013) | (0.012) | |

| Marital status | −0.007 | 0.002 | 0.003 |

| (0.015) | (0.015) | (0.015) | |

| Dependency ratio | −0.138 *** | −0.135 *** | |

| (0.017) | (0.017) | ||

| Healthy ratio | 0.086 *** | 0.080 *** | |

| (0.013) | (0.014) | ||

| Insurance ratio | −0.088 *** | −0.092 *** | |

| (0.009) | (0.010) | ||

| Income Per capita (ln) | 0.045 *** | 0.045 *** | |

| (0.002) | (0.002) | ||

| east | 0.008 | ||

| (0.013) | |||

| middle | 0.028 *** | ||

| (0.011) | |||

| GDP per capita (ln) | −0.093 *** | ||

| (0.021) | |||

| Second industry ratio | 0.920 *** | ||

| (0.134) | |||

| Third Industry ratio | 1.176 *** | ||

| (0.156) | |||

| Wage (ln) | 0.281 *** | ||

| (0.044) | |||

| Employ (ln) | −0.019 *** | ||

| (0.007) | |||

| N | 9918 | 9918 | 9918 |

| R2 | 0.136 | 0.214 | 0.228 |

| Rural Labor Transfer | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Probit | Logit | LPM | |

| Contracted Land Assets | −0.087 *** | −0.090 *** | −0.093 *** |

| (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | |

| Demographic factors | YES | YES | YES |

| Household factors | YES | YES | YES |

| Regional factors | YES | YES | YES |

| Observation | 23,487 | 23,487 | 23,487 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.337 | 0.341 | 0.390 |

| Rural Labor Transfer | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| CFPS 2020 | CFPS 2022 | CFPS 2020–2022 | |

| Contracted land assets | −0.052 *** | −0.054 *** | −0.053 *** |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| Constant | 0.419 *** | 0.459 *** | 0.440 *** |

| (0.047) | (0.049) | (0.034) | |

| Control Variable | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 4919 | 4503 | 9422 |

| R2 | 0.486 | 0.514 | 0.500 |

| Rural Labor Transfer | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Household-Level | Individual-Level | |||||

| East | Center | West | East | Center | West | |

| Contracted Land Assets | −0.122 *** | −0.086 *** | −0.095 *** | −0.098 *** | −0.065 *** | −0.074 *** |

| (0.007) | (0.007) | (0.007) | (0.006) | (0.006) | (0.006) | |

| Demographic factors | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Household factors | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Observation | 3568 | 3434 | 2916 | 8217 | 8242 | 7031 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.276 | 0.190 | 0.209 | 0.346 | 0.343 | 0.344 |

| Rural Labor Transfer | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Household-Level | Individual-Level | |||

| Near the City | Far from the City | Near the City | Far from the City | |

| Contracted Land Assets | −0.086 *** | −0.060 *** | −0.070 *** | −0.050 *** |

| (0.007) | (0.006) | (0.006) | (0.005) | |

| Demographic factors | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Household factors | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Regional factors | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Observation | 4569 | 4569 | 10,993 | 10,993 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.181 | 0.159 | 0.326 | 0.339 |

| Contracted Land Assets | Rural Labor Transfer | |

|---|---|---|

| First Stage | Second Stage | |

| average value of contracted land assets of community excluding one’s own | 0.890 *** | |

| (0.014) | ||

| contracted land assets | −0.198 *** | |

| (0.007) | ||

| Demographic factors | YES | YES |

| Household factors | YES | YES |

| Regional factors | YES | YES |

| Intercept term | 0.807 | −0.299 |

| (0.871) | (0.445) | |

| Observation | 9918 | 9918 |

| R2 | 0.439 | |

| F value on the first stage | 391.89 | |

| Wald Test | 3033.64 *** |

| Rural Labor Transfer | Area of Contracted Land Transferred in | Rural Labor Transfer | |

|---|---|---|---|

| contracted land assets | −0.110 *** | 1.832 *** | −0.108 *** |

| (0.004) | (0.142) | (0.004) | |

| area of contracted land transferred in | −0.001 ** | ||

| (0.000) | |||

| Demographic factors | YES | YES | YES |

| Household factors | YES | YES | YES |

| Regional factors | YES | YES | YES |

| Observation | 9918 | 9918 | 9918 |

| R2 | 0.226 | 0.045 | 0.228 |

| Rural Labor Transfer | Total Income of Agricultural Products | Rural Labor Transfer | |

|---|---|---|---|

| contracted land assets | −0.110 *** | 1.250 *** | −0.091 *** |

| (0.004) | (0.046) | (0.004) | |

| total income of agricultural products | −0.015 *** | ||

| (0.001) | |||

| Demographic factors | YES | YES | YES |

| Household factors | YES | YES | YES |

| Regional factors | YES | YES | YES |

| Observation | 9918 | 9918 | 9918 |

| R2 | 0.226 | 0.124 | 0.251 |

| Rural Labor Transfer | Income from Transfer out of Contracted Land | Rural Labor Transfer | |

|---|---|---|---|

| contracted land assets | −0.110 *** | 0.131 *** | −0.114 *** |

| (0.004) | (0.018) | (0.004) | |

| income from transfer out of contracted land | 0.029 *** | ||

| (0.002) | |||

| Demographic factors | YES | YES | YES |

| Household factors | YES | YES | YES |

| Regional factors | YES | YES | YES |

| Observation | 9918 | 9918 | 9918 |

| R2 | 0.226 | 0.016 | 0.245 |

| Rural Labor Transfer | Income from Non- Agricultural Employment | Rural Labor Transfer | |

|---|---|---|---|

| contracted land assets | −0.110 *** | 0.153 *** | −0.111 *** |

| (0.004) | (0.048) | (0.004) | |

| income from non- agricultural employment | 0.005 *** | ||

| (0.001) | |||

| Demographic factors | YES | YES | YES |

| Household factors | YES | YES | YES |

| Regional factors | YES | YES | YES |

| Observation | 9918 | 9822 | 9822 |

| R2 | 0.226 | 0.091 | 0.231 |

| Rural Labor Transfer | ||

|---|---|---|

| Model (1) | Model (2) | |

| contracted land assets | −0.114 *** | −0.116 *** |

| (0.004) | (0.004) | |

| transfer out of contracted land | 0.228 *** | 0.182 *** |

| (0.012) | (0.028) | |

| Interaction between contracted land assets and transfer out of contracted land | 0.024 * | |

| (0.013) | ||

| Demographic factors | YES | YES |

| Household factors | YES | YES |

| Regional factors | YES | YES |

| Observation | 9918 | 9918 |

| R2 | 0.254 | 0.254 |

| Rural Labor Transfer | ||

|---|---|---|

| Model (1) | Model (2) | |

| contracted land assets | −0.073 *** | −0.064 *** |

| (0.005) | (0.006) | |

| contract land close to the cities | 0.020 *** | 0.058 *** |

| (0.008) | (0.018) | |

| interaction between contracted land assets and contracted land close to cities | −0.020 ** | |

| (0.008) | ||

| Demographic factors | YES | YES |

| Household factors | YES | YES |

| Regional factors | YES | YES |

| Observation | 9138 | 9138 |

| R2 | 0.175 | 0.176 |

| Rural Labor Transfer | Total Income of Agricultural Products | Rural Labor Transfer | Rural Labor Transfer | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model (1) | Model (2) | Model (3) | Model (4) | |

| contracted land assets | −0.075 *** | 1.039 *** | −0.061 *** | −0.061 *** |

| (0.005) | (0.058) | (0.005) | (0.005) | |

| suitability for mechanical farming | −0.011 | 0.757 *** | −0.001 | −0.014 |

| (0.008) | (0.096) | (0.008) | (0.010) | |

| total income of agricultural products | −0.014 *** | −0.016 *** | ||

| (0.001) | (0.001) | |||

| Interaction bewteen suitable for mechanical farming and total income of agricultural products | 0.004 ** | |||

| (0.002) | ||||

| Demographic factors | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Household factors | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Regional factors | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Observation | 8726 | 8726 | 8726 | 8726 |

| R2 | 0.173 | 0.101 | 0.196 | 0.196 |

| Rural Labor Transfer | Total Income of Agricultural Products | Rural Labor Transfer | Rural Labor Transfer | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model (1) | Model (2) | Model (3) | Model (4) | |

| contracted land assets | −0.054 *** | 0.942 *** | −0.040 *** | −0.037 *** |

| (0.013) | (0.147) | (0.013) | (0.013) | |

| whether farmland is fragmented | 0.001 | −0.302 | −0.003 | 0.027 |

| (0.023) | (0.257) | (0.023) | (0.027) | |

| Total income of agricultural products | −0.015 *** | −0.010 *** | ||

| (0.003) | (0.003) | |||

| The interaction between fragmentation of arable land and total income of agricultural products | −0.011 ** | |||

| (0.005) | ||||

| Demographic factors | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Household factors | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Regional factors | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Observation | 1207 | 1207 | 1207 | 1207 |

| R2 | 0.223 | 0.087 | 0.242 | 0.245 |

| Rural Labor Transfer | Total Income of Agricultural Products | Rural Labor Transfer | Rural Labor Transfer | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model (1) | Model (2) | Model (3) | Model (4) | |

| contracted land assets | −0.076 *** | 1.095 *** | −0.061 *** | −0.061 *** |

| (0.005) | (0.058) | (0.005) | (0.005) | |

| quality of arable land | 0.007 | 0.142 | 0.010 | 0.022 ** |

| (0.008) | (0.097) | (0.008) | (0.010) | |

| total income of agricultural products | −0.014 *** | −0.012 *** | ||

| (0.001) | (0.001) | |||

| Interaction between quality of arable land and total income of agricultural products | −0.003 ** | |||

| (0.002) | ||||

| Demographic factors | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Household factors | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Regional factors | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Observation | 8724 | 8724 | 8724 | 8724 |

| R2 | 0.173 | 0.094 | 0.196 | 0.196 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhuo, C.; Deng, Y. Contracted Land Assets and Rural Labor Transfer: Unlocking the Potential for Sustainable Urbanization Through Total Income of Agricultural Products. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10884. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310884

Zhuo C, Deng Y. Contracted Land Assets and Rural Labor Transfer: Unlocking the Potential for Sustainable Urbanization Through Total Income of Agricultural Products. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10884. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310884

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhuo, Chong, and Yuyang Deng. 2025. "Contracted Land Assets and Rural Labor Transfer: Unlocking the Potential for Sustainable Urbanization Through Total Income of Agricultural Products" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10884. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310884

APA StyleZhuo, C., & Deng, Y. (2025). Contracted Land Assets and Rural Labor Transfer: Unlocking the Potential for Sustainable Urbanization Through Total Income of Agricultural Products. Sustainability, 17(23), 10884. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310884