Abstract

In transforming emerging economies, the historical origins of family firms can be traced either to the restructuring of SOEs or to direct establishment. Drawing on imprinting theory and intergenerational family governance, this study investigates how restructuring imprints shape green innovation in family firms and under what conditions these effects vary. Based on data from Chinese A-share listed family firms (2007–2022), we find that restructuring imprints—manifested in risk aversion and path dependence—persist long after privatization. Consequently, restructured family firms demonstrate significantly weaker green innovation performance than entrepreneurial family firms. This negative effect is reinforced by founder control but mitigated by second-generation involvement. Overall, this study identifies a critical source of heterogeneity among family firms and contributes to the literature on green innovation within family business research.

1. Introduction

Green innovation is widely viewed as a strategic choice that enables firms to pursue economic, environmental, and social benefits simultaneously [1]. As green innovation is essential for family firms aiming to build sustainable competitive advantages and ensure intergenerational succession [2], academic interest in this topic has steadily increased. However, existing research remains divided on whether family involvement promotes or inhibits green innovation. One line of research argues that green innovation requires external capital and specialized talent. Consequently, to protect socioemotional wealth derived from family control, family involvement may impede firms’ pursuit of green innovation [2,3,4]. Another line of research suggests that green innovation helps preserve family reputation, strengthen stakeholder relationships, and support intergenerational continuity. Therefore, family involvement can foster corporate green innovation [5,6,7].

Such contradictory views stem from overlooking the internal heterogeneity within the family firms. Prior studies have examined green innovation across several dimensions of family firm heterogeneity, including family ownership involvement [4,8,9], generational involvement [10,11], and ownership structure [12,13]. However, these factors capture only current firm characteristics, with little attention to historically rooted differences. A review of historical-influence research shows that scholars have examined how factors such as CEOs’ experiences of sent-down movement [14], childhood family decline [15], or childhood famine experience [16] shape CSR-related decisions. Yet few studies explore historical imprinting at the organizational level, such as a firm’s historical origin.

Imprinting theory [17] provides a valuable framework for explaining how a firm’s historical origin shapes its green innovation behavior. It also offers a basis for reconciling the above debates. The theory posits that imprints formed during sensitive periods persist through routines, structures, and beliefs. These imprints exert long-term and enduring effects on firms’ strategic choices [18,19]. A firm’s historical origin reflects its broader historical context and has recently gained growing scholarly attention [4,20,21]. However, the relationship between historical origin and family firms’ green innovation behavior remains theoretically underdeveloped. Moreover, most studies of green innovation in family firms rely on socioemotional wealth theory [3,5,6,10], institutional theory [9], or the resource-based view [22]. Only a few have applied imprinting theory [23]. This gap limits the theoretical explanatory power of current research on family-firm green innovation.

Chinese family firms emerged during a unique institutional transition from a planned to a market economy. In the 1990s, China implemented the Zhuada Fangxiao policy (Grasp the Big, Let Go of the Small) to improve economic efficiency by privatizing underperforming SOEs [24,25]. This policy triggered the restructuring of approximately 60,000 SOEs, many of which became family-controlled firms [25,26]. The privatization process also spurred the relaxation of regulatory constraints, fostering an institutional environment conducive to private sector growth. Consequently, a key form of heterogeneity has emerged in transitional economies such as China. Some family firms carry a restructuring imprint from the planned-economy era (restructured family firms), whereas others were founded in the new market environment (entrepreneurial family firms) [27].

The contrasting origins of these firms provide a compelling context for investigating how imprinting shapes corporate sustainability and strategic orientation. SOE privatization constituted a critical sensitive period for the formation of organizational imprints [27]. However, few studies have explored how restructuring imprints influence green innovation in family firms. Green innovation represents a key manifestation of long-term responsibility and sustainability orientation. The limited integration of imprinting theory with family firm sustainability research leaves this question largely unaddressed. To address this gap, this study investigates two questions: How does the restructuring imprinting influence green innovation in family firms? What factors moderate this imprinting effect?

We argue that restructuring experiences shape strategic decisions through imprinting effects. These effects lead to divergent green innovation outcomes between the two types of family firms. Drawing on imprinting theory [17], we propose that pre-restructuring organizational imprints—characterized by risk aversion, procedural rigidity, and path dependence—persist in restructured family firms. These imprints lead to significantly weaker motivation and capability for green innovation compared with entrepreneurial family firms. Given that imprints are malleable and shaped by executive experiences [19], we examine key moderating conditions affecting these relationships. From an intergenerational governance perspective, we focus specifically on founder control and second-generation involvement as key moderators [28]. We predict that founder control exacerbates, while second-generation involvement attenuates, the negative effect of restructuring on green innovation.

We tested our theoretical predictions using regression analyses on 4403 observations of Chinese A-share non-financial family firms from 2007 to 2022. This study makes several contributions to the literature. First, it advances the understanding of factors that shape green innovation in family firms. While prior research emphasizes present-oriented factors like family ownership [8], performance [29], and external pressures [30,31], it largely overlooks historical rooted influences. By examining corporate restructuring as a historical rooted factor, we address this gap and provide empirical evidence that restructuring imprinting inhibits family firms’ green innovation. The findings offer deeper theoretical insights into the sources of family firm heterogeneity [32] and help reconcile existing research contradictions.

Second, this study extends imprinting theory by examining restructuring imprints in family firms. Existing imprinting research has primarily focused on individual-level imprints and their organizational consequences [14,15,33]. In contrast, we examine firm-level imprinting, focusing on how pre-restructuring imprints continue to shape strategic decisions in family firms after privatization. Our work complements research on the enduring effects of institutional origins [27] and broadens the application of imprinting theory to corporate sustainability behavior.

Third, this study examines how organizational imprints are maintained and mitigated from a novel perspective. Prior research has given limited attention to the contextual conditions that shape imprinting mechanisms [17]. By identifying and testing factors that amplify or weaken restructuring imprinting effects, this study provides a broader framework for understanding organizational adaptation. Drawing on intergenerational governance theory [28], we demonstrate that the effects of restructuring imprints in family firms depend on founder control and second-generation involvement. These findings provide a more comprehensive explanation of decision-making in restructured family firms and offer insights into mitigating restructuring imprinting effects. They also respond to calls for examining the contextual contingencies of imprinting [19].

2. Theory and Hypotheses

2.1. Background and Imprinting Perspective

Since the 1990s, a global wave of ownership reforms has shifted many enterprises from state to private ownership [34]. The rise of Chinese family firms took place within this broader institutional transformation. Some of these firms emerged from state-owned enterprise (SOE) restructuring rather than entrepreneurial founding [26]. Market-oriented reforms stimulated individual entrepreneurship, resulting in the creation of numerous entrepreneurial family firms. Meanwhile, many state-owned enterprises were transferred to private individuals—often former SOE executives—and subsequently evolved into restructured family firms. Privatization—by divesting responsibilities associated with state ownership—has become a critical yet underexplored factor for understanding the divergent strategic decisions of family firms [35]. Although some studies have examined the effects of restructuring experiences on family firms’ strategic decision-making [20,27,36], the impact of restructuring imprints on their green innovation remains insufficiently investigated. This gap presents a valuable opportunity to extend the application of imprinting theory to research on the sustainable development of family firms.

Imprinting theory provides a robust framework for explaining how organizational imprints formed during sensitive periods shape strategic decision-making in family firms. The theory comprises three core elements: (1) an organization experiences a brief sensitive period; (2) during this period, it develops characteristics aligned with the prevailing environment; and (3) these characteristics persist even after the environment changes [17]. Organizational imprints stem from the cumulative influence of multiple sensitive periods. New imprints are continuously superimposed on existing ones, creating a dynamic and evolving imprinting process [19]. Imprints formed during sensitive periods endure through mechanisms such as routinization, institutionalization, and structural inertia. These mechanisms ultimately shape the organization’s strategic actions [18].

In restructured family firms, the enduring influence of these imprints can be attributed to the persistence of restructuring imprints [17]. Even after ownership transfers to the family, these imprints continue to shape organizational behavior. We propose that although restructured SOEs acquire the characteristics of family firms, historical imprints from the pre-restructuring period continue to inhibit green innovation.

2.2. Hypotheses Development

2.2.1. Restructuring Imprinting and Green Innovation

Restructured family firms retain several SOE-like characteristics. These include reliance on formal bureaucratic procedures and limited family involvement and intergenerational succession [27]. Drawing on imprinting theory [17], we argue that the historical privatization of SOEs has left a distinct restructuring imprint on these firms. As a result, they differ markedly from entrepreneurial family firms in their green innovation activities. This imprint shapes their green innovation strategies through several key mechanisms.

First, restructuring does not fully eliminate the risk-averse and conservative operational orientations inherited from the SOE era. According to the theory, organizational imprints stem from multiple sensitive periods, where new imprints layer upon existing ones, creating a dynamic, evolving state [19]. These firms experience two critical sensitive periods: the original founding of the SOE and its later privatization. Since their inception, SOEs have operated in a stable policy environment [37], focusing on fulfilling political, social, and administrative mandates [24]. These included meeting production quotas and providing employee welfare, which consumed substantial resources. These obligations also reinforced procedural rigidity designed to protect vested interests [38]. Such historical rigidity creates an organizational burden that impedes the adoption of green innovation. During privatization, the primary objective was managing relationships with key stakeholders to ensure successful restructuring. Together, these sensitive periods generate a risk-averse cognitive imprint that exerts long-term influence on strategic decision-making in restructured family firms. This cognitive imprint weakens the effective mobilization of human resources—shaped by earlier imprints—for achieving technological breakthroughs and knowledge innovation [27]. Since green innovation is inherently high-risk and uncertain [39], this risk-averse cognitive imprint reduces the firms’ willingness to engage in it.

Second, restructured family firms often inherit multi-layered structures and redundant personnel from their SOE predecessors. These features create a structural imprint that undermines their capacity for green innovation. They maintain SOE-like features, including multi-tiered approvals and collective decision-making, resulting in complex procedures [36]. This structural imprint fosters institutional inertia [21], complicating the adoption of modern governance practices. The resulting rigidity hinders swift organizational responses to green innovation opportunities. Moreover, traditional SOE resource allocation prioritized production tasks, often resulting in insufficient investment in innovation [40]. This imprint also complicates resource reconfiguration because entrenched allocation patterns and strong internal stakeholder resistance limit flexibility. Green innovation relies on rapid market responsiveness and flexible resource deployment [39]. Yet institutional inertia and path dependence associated with this structural imprint constrain firms’ capacity to innovate.

In contrast, the entrepreneurial origins of entrepreneurial family firms imprint them with a stronger propensity for risk-taking and resource bricolage. These traits enhance their willingness and capacity to pursue green innovation relative to restructured family firms. Consequently, these firms are more likely to view green innovation as a strategic tool for gaining competitive differentiation and enhancing their corporate reputation [8]. They pursue green innovation primarily in response to market demands aimed at value creation, rather than regulatory pressures [41]. Their organizational structures are typically flatter and more flexible [42]. As these firms often operate with limited resources, frequently drawn from family members’ personal assets, they develop strong resource bricolage capabilities [43]. This flexibility in resource mobilization enables them to rapidly allocate resources to emerging initiatives, including green innovation.

In summary, cognitive and structural imprints lead restructured family firms to display lower willingness and weaker capacity for green innovation than their entrepreneurial counterparts. Therefore, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 1.

Restructured family firms exhibit lower levels of green innovation than entrepreneurial family firms.

2.2.2. The Moderating Role of Founder Control

Founder control refers to situations in which the founder serves as the firm’s CEO or board chair. In restructured family firms, founders are often former senior SOE executives who serve as direct carriers of restructuring imprinting. Their managerial philosophies and behavioral patterns are shaped by their experience in state-owned enterprises during the planned-economy era. Accordingly, we propose that founder control amplifies the imprinting effect in restructured family firms. As a result, it strengthens the negative influence of restructuring experience on green innovation strategies.

First, founder control reinforces cognitive imprinting within restructured family firms. Unlike “opportunity creators,” founders of restructured family firms act as “opportunity inheritors”. As former SOE executives, founder-CEOs (or chairs) are deeply involved in strategic decisions and therefore tend to preserve existing systems and organizational cultures [44]. They also exhibit strong emotional attachment to, and identification with, the firm [45]. Moreover, restructured family firms often retain responsibility for accommodating former SOE employees, who are accustomed to routines characterized by rule compliance and risk aversion. Having long worked with such groups, founder-CEOs often struggle to promote high-risk strategic initiatives. As a result, restructured family firms under founder control are more likely to retain the risk-averse and path-dependent tendencies of their SOE predecessors [17]. This reinforces cognitive imprinting and further suppresses their willingness to pursue green innovation.

Second, founder control reinforces structural imprinting in restructured family firms. Many founders of these firms were chosen to take over restructured enterprises because of their strong political capital. As participants and decision-makers in SOE privatization, they tend to preserve existing governance structures and institutional norms [46]. Unlike founders of entrepreneurial family firms, founders of restructured family firms excel at fulfilling assigned production tasks but lack experience in competitive markets. Additionally, as former SOE executives, they often possess substantial authority. Their centralized decision-making style may suppress voices advocating for deviation from established paths [47]. These factors increase the complexity and length of decision-making processes, which makes it difficult for firms to respond quickly to the demands of green innovation. Consequently, structural imprinting is further reinforced, thereby weakening restructured family firms’ green innovation capabilities. Therefore, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 2.

Founder control strengthens the negative relationship between restructured family firms and green innovation.

2.2.3. The Moderating Role of Second-Generation Involvement

Second-generation involvement refers to the participation of next-generation family members as top managers who engage in routine decision-making. It is also considered essential for ensuring the long-term continuity of family firms [48]. Such involvement often reflects a family’s succession intentions and long-term orientation, which can reshape the firm’s decision-making logic and governance structure [49]. Accordingly, we propose that second-generation involvement weakens imprinting in restructured family firms and mitigates its negative effects on green innovation strategies.

First, second-generation involvement helps reduce cognitive imprinting in restructured family firms. Next-generation members neither participated in the privatization of former SOEs nor share work experience with former SOE employees. Consequently, they pay limited attention to implicit contracts with employees—such as expectations of long-term job security or seniority-based promotion. Moreover, second-generation involvement signals a long-term orientation [50], which enhances the firm’s tolerance for risk [51]. Although green innovation is inherently risky and uncertain, its successful implementation can enhance firm sustainability and support intergenerational succession [29]. Most next-generation family members have received higher education, often with international exposure, which increases their openness to risk-taking [52,53]. As a result, they are more likely to view green innovation as both a business opportunity and a means of building future competitive advantage [7]. Thus, second-generation involvement partially attenuates cognitive imprinting and enhances the green innovation intentions of restructured family firms.

Second, second-generation involvement helps reduce structural imprinting in restructured family firms. Unlike founder-CEOs, highly educated next-generation members often introduce new managerial knowledge and promote organizational restructuring. Lacking work experience in former SOEs, they are more likely to deviate from the hierarchical decision-making processes inherited from the SOE system [49]. A more flexible organizational structure enables faster responses to the demands of green-innovation strategies. Moreover, updating organizational routines and structures involve reallocating resources [54], thereby creating a more supportive environment for green innovation [55]. In other words, second-generation involvement may challenge entrenched resource allocation patterns [56]. This weakens structural imprinting and enhances the firm’s capability to pursue green innovation. With structural imprinting reduced, family firms can reallocate resources once committed to maintaining traditional relationships or redundant assets to green innovation initiatives. Therefore, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 3.

Second-generation involvement weakens the negative relationship between restructured family firms and green innovation.

3. Methods

3.1. Data and Sample

This study examines Chinese A-share listed family firms from 2007 to 2022. We applied the following screening criteria to the initial sample: (1) excluding financial firms to avoid sample bias and heteroscedasticity; (2) excluding firms designated as ST, PT, delisted, or undergoing IPO; and (3) excluding firms with missing data on core variables. The final sample consists of 4403 firm-year observations. Data for this study were obtained from the following sources: green-innovation data from the CNRDS database, and executive information, financial data, and firm characteristics from the CSMAR and WIND databases. CNRDS, CSMAR, and WIND are authoritative and widely used data platforms for Chinese listed firms, particularly in strategic management research. Definitions of variables and corresponding measurement criteria are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Variable Definitions.

3.2. Measurements

3.2.1. Dependent Variable

Green innovation (GI) is measured by the natural logarithm of the count of green invention patent applications. This metric captures a firm’s commitment to substantive, environmentally focused technological development.

3.2.2. Independent Variable

Restructured family firms (RST) is identified using a dummy variable that takes the value of 1 if the family firm originated from the restructuring of a state-owned enterprise, and 0 otherwise.

3.2.3. Moderating Variables

Founder control (FC) is a dummy variable coded 1 if the founder of the family firm holds the position of board chair or chief executive officer (CEO), and 0 otherwise.

Second-generation involvement (SGEN) is a dummy variable coded 1 if a family successor holds an executive position, and 0 otherwise.

3.2.4. Control Variables

Control variables include firm size (SIZE), firm age (AGE), leverage (LEV), current ratio (CR), institutional investor ownership (INST), R&D intensity (RD), ownership concentration (TOP1), Tobin’s q (TQ), market concentration (HHI), and marketization index (MI).

3.3. Modeling

To select an appropriate econometric model to analyze the panel data, we conducted the Hausman test. The result (p < 0.05) implies that it is appropriate to use the fixed-effect model instead of the random-effect model [58]. All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata 15 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA). Hence, the following 3 fixed-effect panel regression models are applied to test the hypotheses.

Model 1 serves as the baseline model to estimate the relationship between restructured family firms and green innovation.

Model 2 evaluates how founder control moderates the relationship between restructured family firms and green innovation.

Model 3 evaluates how second-generation involvement moderates the relationship between restructured family firms and green innovation.

4. Empirical Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

As presented in Table 2, descriptive statistics reveal that restructured family firms (RST) comprise a substantial portion (25%) of the sample. This significant representation allows for a meaningful comparison with entrepreneurial family firms. The mean of GI is 0.48 and the median is 0, indicating a highly skewed distribution, with most firms not engaging in green innovation activities. Significant differences are observed in firm size, age, leverage, and ownership concentration, suggesting that the dataset encompasses family firms at various stages of development. In addition, the dispersion in R&D intensity and institutional ownership highlights the heterogeneity in innovation investment and external monitoring. Overall, the descriptive statistics confirm that the sample is sufficiently diverse, providing a solid foundation for testing the hypothesized relationships.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations.

Table 3 shows the Pearson correlations of the main variables. Since all coefficients are below 0.6, multicollinearity does not pose a concern for the subsequent analyses.

Table 3.

Correlation matrix of main variables.

4.2. Baseline Regressions

We examine how the origin of family firms affects green innovation. The baseline regression results are presented in Table 4. In Model 1, the coefficient of RST is significantly negative (coef = −0.203, p < 0.01), indicating that restructured family firms exhibit lower levels of green innovation compared with founder-established firms. As shown in Model 2, the relationship remains negative and significant (coef. = −0.134, p < 0.05) after incorporating environmental and firm-level controls. These findings provide support for Hypothesis 1.

Table 4.

Baseline regression results.

4.3. Endogeneity Control and Robustness Tests

First, to address potential endogeneity concerns and ensure the robustness of our findings, we employ a two-stage least squares (2SLS) estimation with an instrumental variable. We instrument for the restructuring imprint using the provincial population flow index from the 1990s (Popu), coded 1 for net inflow and 0 otherwise [23]. This instrument is theoretically justified, as regions with greater population inflows historically fostered more open and inclusive entrepreneurial environments [59], which influenced the foundation of entrepreneurial firms but is unlikely to directly affect contemporary green innovation. The results of this endogeneity test are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

IV-2SLS regression test.

Second, firms are not randomly classified as restructured or entrepreneurial family businesses. As a result, the two types may systematically differ in size, age, and asset structure, factors that can also affect green innovation. Consequently, observed differences in green innovation may partly reflect these underlying characteristics rather than the causal effect of firm type.

To address potential sample selection bias, we employ propensity score matching (PSM) using firm size, age, and leverage ratio to create comparable groups. In this procedure, restructured family firms serve as the treatment group, and entrepreneurial family firms serve as the control group. This setup allows a more credible estimation of the net effect of firm type on green innovation. We apply one-to-one nearest-neighbor matching with a caliper of 0.05 to identify comparable matches. To maximize the retained sample while maintaining sufficient matching quality, we retain all matched observations with weights ≥ 1, resulting in a sample with improved covariate balance [60]. The matched sample consists of 687 restructured family firms and 732 entrepreneurial counterparts. Covariate balance tests before and after matching show that standardized mean differences for all matching variables are substantially reduced. Most differences fall below the conventional 10% threshold, indicating that the matching procedure is effective [61]. Regression results based on the matched sample are consistent with previous estimates (Table 6), indicating that our findings are robust to potential sample selection bias.

Table 6.

PSM-matched sample regression results.

Third, to ensure our results are robust to the choice of innovation metric, we replace our measure of green innovation with the natural logarithm of the total number of granted green invention and utility model patents (GPG). Fourth, we use green invention patent applications in year t + 1 as the dependent variable. Additionally, we exclude observations from 2020 to 2022 to mitigate potential confounding effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. As shown in Table 7, our core findings withstand a thorough set of robustness checks.

Table 7.

Other robustness tests.

4.4. The Moderating Effect of Founder Control and Second-Generation Involvement

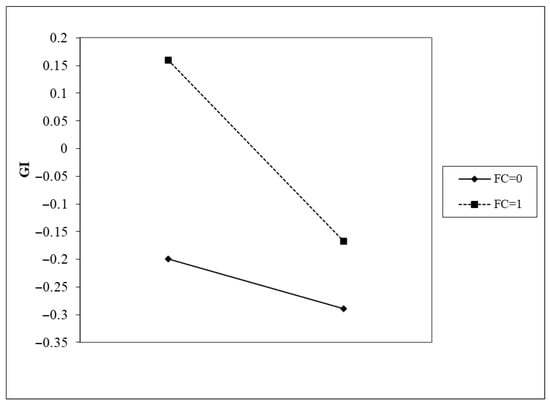

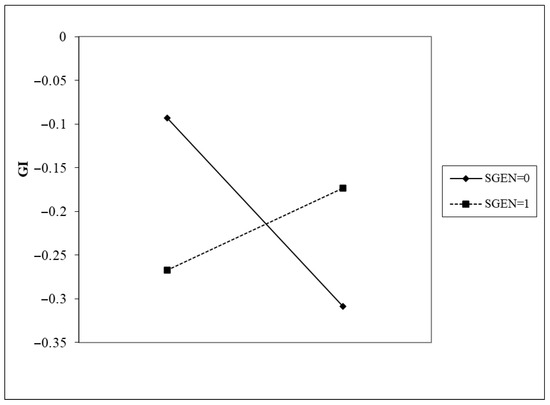

Table 8 reports the moderating effects of founder control and second-generation involvement on the relationship between family firm origin and green innovation. Model 1 shows that the interaction term between founder control and restructured family businesses (FC × RST) is significantly negative (coef = −0.341, p < 0.01), indicating that founder control strengthens the negative association between restructured family firms and green innovation, consistent with Hypothesis 2. Model 2 reveals that the interaction term between second-generation involvement and restructured family businesses (SGEN × RST) is significantly positive (coef = 0.378, p < 0.05). These results provide support for Hypothesis 3, indicating that second-generation involvement mitigates the negative effect of restructuring on green innovation. Model 3 incorporates both moderating effects simultaneously, and the results remain consistent with those in Models 1 and 2, confirming the robustness of the moderating effects.

Table 8.

Moderating role of founder control and second-generation involvement.

Figure 1 and Figure 2 illustrate the moderating effects of founder control (FC) and second-generation involvement (SGEN), respectively. As shown in Figure 1, restructured family firms are generally less engaged in green innovation (GI) than founder-established firms, regardless of founder control. However, this negative tendency is more pronounced when the founder is in control (FC = 1), as indicated by a steeper slope. Figure 2 demonstrates that when a second-generation family member participates in management (SGEN = 1), restructured family firms exhibit a higher propensity for green innovation compared with founder-established counterparts.

Figure 1.

The Moderating Effect of Founder Control on the RST-GI Relationship.

Figure 2.

The Moderating Effect of Second-Generation Involvement on the RST-GI Relationship.

4.5. Mechanism Test

As discussed above, restructured family firms exhibit lower green innovation due to their cognitive and structural imprints. The cognitive imprint is characterized by managers’ limited tolerance for risk, whereas the structural imprint reflects a higher degree of bureaucratic intensity. To verify that these mechanisms account for the observed differences in green innovation, we use risk-taking capacity (SOL) as a proxy for cognitive imprinting and employee scale (ES) as a proxy for structural imprinting.

SOL is measured as the ratio of operating earnings before interest and taxes to the average balance of total liabilities, which captures the firm’s financial buffer for absorbing potential risks [62]. ES is measured as the natural logarithm of the number of employees plus one, reflecting the organizational inertia typically associated with a more bureaucratic structure [63].

As reported in columns (1)–(2) of Table 9, restructured family firms demonstrate significantly higher SOL and larger ES compared with entrepreneurial family firms. These findings provide evidence that the cognitive and structural imprints embedded in restructured family firms constrain their green innovation.

Table 9.

Mechanism test: cognitive and structural imprints.

5. Discussion

5.1. Main Findings

Drawing on imprinting theory, this study investigates how restructuring imprinting affects the green innovation strategies of family firms and under what conditions this effect is amplified or attenuated. Family firms can be classified as entrepreneurial or restructured, depending on whether they were directly founded by the family. Formal analyses within the imprinting-theory framework indicate that restructured family firms exhibit lower levels of green innovation compared to entrepreneurial family firms. This finding remains robust across multiple robustness tests. Mechanism analyses further support this argument. Restructuring often leaves risk-averse cognitive imprints and path-dependent structural imprints, which reduce both the willingness and capacity of restructured family firms to pursue green innovation.

We also find that founder control amplifies the effect of restructuring imprinting. Founders tend to perpetuate the risk aversion and path dependence tendencies inherited from the restructured enterprise. Consequently, restructured family firms under founder control exhibit lower levels of green innovation than those without founder control. Finally, second-generation involvement attenuates the imprinting effect by reshaping the firm’s decision-making logic. Accordingly, restructured family firms with second-generation involvement exhibit higher levels of green innovation than those without it. For example, Wahaha Group Co., Ltd.—a representative restructured family firm—experienced a shift in strategic logic after second-generation leader Fuli Zong assumed an executive role. She disrupted the firm’s path dependence and reframed green innovation from a “compliance cost” to an “innovation engine”, thereby accelerating Wahaha’s transition toward sustainability.

5.2. Theoretical Implications

First, this study contributes to the literature on determinants of green innovation in family firms by offering a novel perspective on the sources of firm heterogeneity. Although prior studies recognize present drivers of green innovation, including family ownership [4,8], they mainly draw on socioemotional wealth [6,10,11] or institutional theory [9], with little focus on historical factors through imprinting theory [23]. Focusing on historical origins, this study addresses scholars’ calls to explore green innovation drivers in family firms [7] through the lens of the restructuring context. Furthermore, previous research has identified sources of heterogeneity, such as family capital [64] and intergenerational succession [65]. Our investigation of restructuring imprinting further deepens the understanding of heterogeneity in family firms [32] and helps reconcile existing research contradictions.

Second, this study extends imprinting theory by investigating restructuring imprinting at the firm level in family firms. While prior research has focused on individual-level imprinting effects [14,15,19], this study emphasizes firm-level imprints and their organizational consequences. The results demonstrate that restructured family firms exhibit lower green innovation levels than entrepreneurial counterparts. This supports our core thesis that restructuring imprints persistently influence strategic decisions after privatization. These findings complement studies on the long-term effects of institutional origins [20,21,27] and extend imprinting theory to research on corporate sustainable behavior [23].

Finally, this study investigates the maintenance and mitigation of organizational imprints from a novel perspective. It provides theoretical insights into how firms overcome influences from early institutional environments. The interaction between imprints and contextual conditions offers a better explanation of imprinting mechanisms [17]. This highlights the importance of examining situational contingencies. Within Chinese family firms, we show that the manifestations of restructuring imprinting depend on intergenerational governance structures [28]. Confirming the malleability of imprinting effects, we find that both founder control and second-generation involvement significantly influence imprint expression. These findings offer a more comprehensive explanation of decision-making in restructured family firms. They also address calls to identify and test the contextual conditions that affect imprinting effects [19].

5.3. Practical Implications

This study offers practical implications for both family firm owners and policymakers. First, since imprints from different periods may interact complexly, firms should intentionally recruit managers with diverse backgrounds to introduce new imprints that counterbalance negative legacy effects. The findings show that while restructured family firms demonstrate lower green innovation, second-generation involvement can mitigate this disadvantage. Therefore, restructured family firms should consider integrating the next generation into management and strategic decision-making to mitigate such risks.

Second, managers in family firms should recognize their own limitations and actively mitigate the constraints imposed by cognitive imprinting. For example, boards may appoint independent directors for green innovation—professionals with expertise in green technologies who hold decisive authority in evaluating green projects. Firms may also establish a Green Innovation Committee under the board. Beyond formulating and overseeing the firm’s green innovation strategy, this committee should facilitate regular exchanges between management teams and benchmark green-innovation firms. In addition, the board should dynamically adjust green-innovation decisions based on policy interpretations, projected returns, and industry conditions.

Third, the government should align with the “dual-carbon goals” and develop differentiated policy support systems [66]. For restructured family firms, the government may create “green transition seed funds” or provide guarantees for their applications for green-transition loans. At the same time, government agencies may organize experts to offer free training on green innovation, helping these firms overcome constraints in both financing and technology. For entrepreneurial family firms, the government may introduce “green market expansion subsidies” to encourage them to develop markets through green products or services. Moreover, the government could provide “green talent recruitment subsidies” to support firms in attracting skilled personnel who can contribute to their green-development capabilities.

5.4. Limitations and Future Research Directions

One limitation concerns the research sample. This study focuses on listed firms. Although the large-sample analysis confirms the presence of restructuring imprinting, it cannot precisely capture the rich heterogeneity embedded within the variables. We suspect that the imprinting effect may operate through different mechanisms in smaller private family firms. Future research could collect primary data through surveys to examine this possibility. In addition, the sample period spans 2007–2022, which is later than most state-owned enterprise restructurings. While imprinting theory emphasizes persistence, we are unable to directly observe the imprint formation process during the sensitive restructuring period. Future studies may conduct retrospective research—drawing on in-depth interviews, archival materials, and oral histories—to more thoroughly analyze the imprinting effect in restructured family firms.

Another limitation concerns measurement. Although we replaced the measures of green innovation in the robustness checks, we did not separately examine differences between the two categories of green innovation within restructured family firms. Future research could investigate both substantive and strategic green innovation to explore how restructuring imprinting differentially shapes these activities. This study identifies a threshold effect of second-generation involvement on the imprinting of restructured family firms. Building on this, future research could incorporate more fine-grained measures of second-generation involvement (e.g., shareholding percentage, years in management, or positional power) to test how varying levels of involvement influence the imprinting effect.

6. Conclusions

Several scholars have examined green innovation in family firms, reporting divergent findings. Building on this literature, we employ imprinting theory to investigate how restructuring experience shapes family firms’ green-innovation strategies. The results indicate that restructuring imprinting causes restructured family firms to exhibit lower levels of green innovation than their entrepreneurial counterparts. We further find that founder control amplifies this imprinting effect, while second-generation involvement attenuates it. This study demonstrates that restructuring experience represents a significant source of heterogeneity among family firms. It suggests that future research could explore additional consequences of this historical origin. Our findings highlight the impact of restructuring experience on family firms’ green transitions and guide mitigation of its negative imprinting effects.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Z. and W.L.; methodology, W.L.; software, W.L.; validation, W.L.; formal analysis, Y.Z.; investigation, Y.Z. and W.L.; resources, Y.Z.; data curation, Y.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.Z.; writing—review and editing, Y.Z., W.L. and F.Z.; visualization, Y.Z.; supervision, Y.Z. and W.L.; project administration, Y.Z.; funding acquisition, Y.Z. and W.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Social Science Foundation of Guangdong Province, grant number GD25YSG34; the Education Science Planning Project of Guangdong Province, grant number 2024GXJK157; the Program for Scientific Research Start-up Funds of Guangdong Ocean University, grant number 060302092309; the Zhanjiang Social Science Federation, grant number ZJ24QN15; and the Zhanjiang Social Science Federation: ZJ24QY21.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data and models used during this study are available from the corresponding author by request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the editors and anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Karimi Takalo, S.; Sayyadi Tooranloo, H.; Shahabaldini Parizi, Z. Green innovation: A systematic literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 279, 122474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miroshnychenko, I.; Miller, D.; De Massis, A.; Le Breton-Miller, I. Are family firms green? Small Bus. Econ. 2025, 64, 279–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.L.; Lin, W.T.; Shih, Y.N. When do family firms plant different new trees? The role of family firms and CSR committees in green innovation. Manag. Organ. Rev. 2025, 21, 250–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Shen, Z.; An, P.; Ali, F.; Ali, I. Family embeddedness is detrimental to going green: Family involvement and green strategies. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2025, 34, 4095–4110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Lee, J.; Kim, S.J. How does family involvement affect environmental innovation? A socioemotional wealth perspective. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauweraerts, J.; Arzubiaga, U.; Diaz-Moriana, V. Connecting socioemotional wealth to green product innovation: The role of absorptive capacity. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2025, 42, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bammens, Y.; Hünermund, P. Nonfinancial considerations in eco-innovation decisions: The role of family ownership and reputation concerns. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2020, 37, 431–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.L.; Shang, H.B.; Li, W.N.; Lan, H.L. How does family ownership and management influence green innovation of family firms: Evidence from China. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2024, 27, 170–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, A.; Riaz, H.; Liedong, T.A.; Rajwani, T. Does family matter? Ownership, motives and firms’ environmental strategy. Long Range Plan. 2023, 56, 102216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Li, J.Z.; Su, E.M. The effect of second-generation involvement on environmental performance in family firms: A SEW resources perspective. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2025, 38, 239–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, P.J.; Wang, J.; Tang, S.Y.; Shahzadi, I.; Bilan, Y. How does intergenerational transmission affect green innovation? Evidence from Chinese family businesses. Struct. Change Econ. Dyn. 2025, 73, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Yang, T.; Chen, J.; Li, Z. State ownership and green innovation in family firms. Int. Rev. Financ. 2025, 25, e70039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.J.; Wang, X.Z.; Li, B.Y.; Liu, Y.S. Ownership structure and eco-innovation: Evidence from Chinese family firms. Pac.-Basin Financ. J. 2023, 82, 102158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Jiang, J.; Zhang, L.; Huang, C.; Wang, D. Do CEOs with sent-down movement experience foster corporate environmental responsibility? J. Bus. Ethics 2023, 185, 147–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M.; Zhou, N. A CEO’s childhood family decline and corporate social responsibility: The mediating role of long-term orientation. J. Bus. Ethics 2024, 200, 623–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Chi, W.; Zhou, J. Prosocial imprint: CEO childhood famine experience and corporate philanthropic donation. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 139, 1604–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquis, C.; Tilcsik, A. Imprinting: Toward a multilevel theory. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2013, 7, 195–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannan, M.T.; Freeman, J. Structural inertia and organizational change. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1984, 49, 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simsek, Z.; Fox, B.C.; Heavey, C. “What’s past is prologue”: A framework, review, and future directions for organizational research on imprinting. J. Manag. 2015, 41, 288–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Li, W.; Cheng, C.; Huang, H.; Liu, G. Historical ownership of family firms and corporate fraud. J. Bus. Ethics 2025, 198, 293–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, S.; Zhu, F.; Zhou, H.; Zhu, Z. Family firm heterogeneity and innovation: The role of firm origin and family involvement. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2025, 63, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veiga, P.M. Key drivers of green innovation in family firms: A machine learning approach. J. Fam. Bus. Manag. 2025, 15, 346–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Li, S.; Liu, S.; Zhang, S. Origin matters: The institution imprint effect and green innovation in family businesses. Financ. Res. Lett. 2022, 50, 103324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megginson, W.L.; Netter, J.M. From state to market: A survey of empirical studies on privatization. J. Econ. Lit. 2001, 39, 321–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Li, W.; Lin, C.; Wei, L. What causes privatization? Evidence from import competition in China. Manag. Sci. 2024, 70, 3080–3101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Fu, X.; Fu, X. Varieties in state capitalism and corporate innovation: Evidence from an emerging economy. J. Corp. Financ. 2021, 67, 101919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.T.; Wu, Q.; Sarwar, Z.; Yang, Z.; Ghafoor, S. Liability of origin imprints: How do the origin imprints influence corporate innovation? Evidence from China. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2025, 12, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daspit, J.J.; Holt, D.T.; Chrisman, J.J.; Long, R.G. Examining family firm succession from a social exchange perspective: A multiphase, multistakeholder review. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2016, 29, 44–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, P.A.N.; Voordeckers, W.; Huybrechts, J.; Lambrechts, F.; Van Gils, A. Eco-innovations in family SMEs: Understanding the role of financial performance satisfaction. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2025, 63, 1721–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, C.G.; Canale, F.; Cruz, A.D. Green innovation in the Latin American agri-food industry: Understanding the influence of family involvement and business practices. Br. Food J. 2022, 124, 2209–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, R.S.; Li, H.; Feng, S.X.; Zhou, Y.C. Clan culture and green innovation of family firms: The mediating role of socioemotional wealth. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2025, 37, 4270–4282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daspit, J.J.; Chrisman, J.J.; Ashton, T.; Evangelopoulos, N. Family firm heterogeneity: A definition, common themes, scholarly progress, and directions forward. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2021, 34, 296–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Yang, Z. Is the past really gone? How CEOs’ socialist imprinting affects corporate green innovation in China. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2025, 37, 1852–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Souza, J.; Megginson, W.L.; Ullah, B.; Wei, Z. Growth and growth obstacles in transition economies: Privatized versus de novo private firms. J. Corp. Financ. 2017, 42, 422–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mou, S.; Wang, X.; Hu, F. Does privatization hurt ESG? The role of state-owned imprinting. Energy Econ. 2025, 151, 108946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Li, W.; Liu, G.; Liu, Y. Origin matters: Institutional imprinting and family firm innovation in China. Emerg. Mark. Rev. 2023, 55, 100990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, M.; Ruan, R. State-owned enterprises in China as macroeconomic stabilizers: Their special function in times of eco-nomic policy uncertainty. China World Econ. 2023, 31, 87–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Justin, T.J.; Litsschert, R. Environment-strategy relationship and its performance implications: An empirical study of the Chinese electronics industry. Strateg. Manag. J. 1994, 15, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Dong, R.K.; Feng, T. Technological innovations in carbon emission reduction: A comparative analysis of R&D and carbon offsetting strategies. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2025, 206, 111153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, N.; Huang, K.G.; Man Zhang, C. Public governance, corporate governance, and firm innovation: An examination of state-owned enterprises. Acad. Manag. J. 2019, 62, 220–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangelico, R.M.; Nastasi, A.; Pisa, S. A comparison of family and nonfamily small firms in their approach to green innovation: A study of Italian companies in the agri-food industry. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2019, 28, 1434–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S.A.; Hayton, J.C.; Neubaum, D.O.; Dibrell, C.; Craig, J. Culture of family commitment and strategic flexibility: The moderating effect of stewardship. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2008, 32, 1035–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, A.R.; Jack, S.L.; Dodd, S.D. The role of family members in entrepreneurial networks: Beyond the boundaries of the family firm. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2005, 18, 135–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, X.; Ren, L.; Ren, G. Founder CEOs, personal incentives, and corporate social irresponsibility. Bus. Ethics Environ. Responsib. 2022, 31, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chittoor, R.; Aulakh, P.S.; Ray, S. Microfoundations of firm internationalization: The owner CEO effect. Glob. Strateg. J. 2019, 9, 42–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radić, M.; Ravasi, D.; Munir, K. Privatization: Implications of a shift from state to private ownership. J. Manag. 2021, 47, 1596–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souder, D.; Simsek, Z.; Johnson, S.G. The differing effects of agent and founder CEOs on the firm’s market expansion. Strateg. Manag. J. 2012, 33, 23–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, P.R.J.M.; Sharma, P.; De Massis, A.; Wright, M.; Scholes, L. Perceived parental behaviors and next-generation engagement in family firms: A social cognitive perspective. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2019, 43, 224–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldkirch, M.; Belschner, R.; Kammerlander, N. Taking charge: A configurational perspective on post-succession change in family firms. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2025, 49, 992–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrone, P.; Cruz, C.; Gomez-Mejia, L.R. Socioemotional wealth in family firms: Theoretical dimensions, assessment ap-proaches, and agenda for future research. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2012, 25, 258–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Bruton, G.D.; Li, X.; Wang, S. Transgenerational succession and R & D investment: A myopic loss aversion perspective. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2021, 46, 193–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodfield, P.; Husted, K. Intergenerational knowledge sharing in family firms: Case-based evidence from the New Zealand wine industry. J. Fam. Bus. Strateg. 2017, 8, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraiczy, N.D.; Hack, A.; Kellermanns, F.W. What makes a family firm innovative? CEO risk-taking propensity and the organizational context of family firms. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2015, 32, 334–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minichilli, A.; Nordqvist, M.; Corbetta, G.; Amore, M.D. CEO succession mechanisms, organizational context, and performance: A socio-emotional wealth perspective on family-controlled firms. J. Manag. Stud. 2014, 51, 1153–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Feng, T.; Lu, Y.; Jiang, W. Using blockchain or not? A focal firm’s blockchain strategy in the context of carbon emission reduction technology innovation. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2024, 33, 3505–3531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Gao, C.; Feng, M. Owner offspring gender and long-term resource allocation in Chinese family firms. Int. J. Financ. Econ. 2023, 28, 2549–2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, G.; Ma, G.; Wang, X. Institutional reform and economic growth of China: 40-year progress toward marketization. Acta Oeconomica 2019, 69, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, G.A.; Leech, N.L.; Gloeckner, G.W.; Barrett, K.C. SPSS for Introductory Statistics: Use and Interpretation; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grebski, M. Mobility of the workforce and its influence on innovativeness (comparative analysis of the United States and Poland). Prod. Eng. Arch. 2021, 27, 272–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Fraser, M.W. Propensity Score Analysis: Statistical Methods and Applications; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum, P.R.; Rubin, D.B. Constructing a control group using multivariate matched sampling methods that incorporate the propensity score. Am. Stat. 1985, 39, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, Y.; Yang, Y. The innovation plight and operational efficiency of Chinese manufacturing enterprises: From the perspective of risk tolerance, expectation, and profitability. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omidvar, O.; Safavi, M.; Glaser, V.L. Algorithmic routines and dynamic inertia: How organizations avoid adapting to changes in the environment. J. Manag. Stud. 2023, 60, 313–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero, I. How familial is family social capital? Analyzing bonding social capital in family and nonfamily firms. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2018, 31, 441–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, J.H.; Chrisman, J.J.; Steier, L.P. Sources of heterogeneity in family firms: An introduction. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2012, 36, 1103–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Feng, T.; Lu, Y.; Xue, R. Optimal government policies for carbon-neutral power battery recycling in electric vehicle industry. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2024, 189, 109952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).