Abstract

As the fashion industry accelerates its digital and sustainable transformation, the European Union’s policy development on Digital Product Passports (DPPs) has attracted growing attention. However, there is still a lack of systematic research into whether consumers, particularly those outside Europe, are willing to adopt this emerging technology for greater transparency. To address this, this study develops an extended Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) by integrating three individual-level consumer variables, Ethical–Sustainability Orientation (ESO), Circular Value Orientation (CVO), and Technological Awareness (TA), to examine how these factors work in concert to shape consumers’ intentions to accept Digital Product Passports (DPPs). Data were collected from US consumers through an online survey, yielding 425 valid responses. Participants were recruited from a professional consumer panel managed by a market research firm. Structural equation modeling was conducted to test the proposed research model and hypotheses. The results reveal that Perceived Usefulness (PU) emerges as the most influential determinant of consumers’ acceptance of Digital Product Passports. Both Ethical–Sustainability Orientation (ESO) and Circular Value Orientation (CVO) demonstrate significant direct effects on adoption intention and indirect impacts through PU. Technological Awareness (TA) exhibits only a modest direct effect, suggesting that its role in shaping adoption behavior is comparatively limited. This study broadens the geographic and cultural scope of existing research on Digital Product Passports (DPPs) by providing empirical evidence on consumer acceptance in a non-European context. The findings advance the theoretical understanding of DPP adoption while offering practical implications for fashion brands and policymakers seeking to facilitate the global implementation of DPP systems within the fashion industry.

1. Introduction

The fashion industry, which relies heavily on natural resources and a global supply chain, faces significant environmental and social challenges. It remains one of the most polluting industries globally, accounting for 8 to 10 percent of annual carbon emissions and generating millions of tons of waste. Labor concerns, including child labor, persist as well [1]. However, fashion supply chains are long and complex [2], making it difficult for consumers to access information about raw material sourcing, production processes, or transportation routes [3]. Limited access to such data restricts green purchasing behavior [4]. Improving supply chain transparency has become crucial for achieving sustainable transformation in the fashion industry.

In response, the European Union (EU) introduced the Digital Product Passport (DPP) system in 2020. As part of the Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation (ESPR), products sold in the EU, including textiles and apparel, are required to comply with the ESPR framework by 2030 [5]. DPPs are created to establish digital records for each product, including material origins, environmental impacts, repair options, and recycling routes. All stakeholders in the supply chain, including material suppliers, producers, and consumers, can access these records [6]. The system aims to enhance transparency, minimize environmental harm, and promote sustainable consumer choices that align with the objectives of a circular economy. Although the EU primarily drives the DPP initiative, sustainability practices vary considerably across global regions. In parallel, Germany’s Supply Chain Due Diligence Act requires large companies to ensure that their global supply chains comply with human rights and environmental standards [7]. France has also enacted legislation targeting ultra-fast fashion, which includes ecological labeling and advertising restrictions [8]. These regulatory measures reflect a broader trend toward mandatory transparency and accountability in product and supply chain governance. While these regulatory advancements illustrate Europe’s commitment to sustainable governance, global sustainability efforts also hinge on consumer participation, especially in the United States, one of the largest consumer markets. Despite being a mature market with high levels of digital adoption, the US consumer behavior toward DPPs and the sustainable consumption they facilitate remains largely unexplored. Therefore, situating consumer acceptance within a broader global perspective enhances the research’s international relevance and provides a more comprehensive understanding of DPP implementation.

While DPP policies are gaining momentum, academic research remains primarily focused on technology, compliance, and industrial implementation. Studies on consumer acceptance of DPPs remain limited [9]. Although the primary purpose of DPPs is to enhance industry transparency and strengthen producer responsibility, their overall effectiveness ultimately depends on whether consumers can meaningfully engage with and use the information they provide [10]. By disclosing raw material origins, production processes, and environmental impacts, DPPs extend transparency mechanisms to the consumer domain, thereby shaping consumers’ perceptions, evaluations, and purchase decisions. Consumers’ willingness to access, trust, and adapt to DPP information directly influences whether transparency leads to sustainable consumption behaviors; therefore, consumers are essential in verifying the effectiveness of the DPP ecosystem in advocating sustainable production and consumption in the fashion industry globally [11]. Few empirical studies have examined how consumers accept and use DPPs, and most are based on European populations, raising questions about the geographic generalizability of these findings [12]. Existing studies have shown that consumers often express positive attitudes toward DPPs, demonstrating trust in transparent companies and a willingness to pay a premium for DPP-enabled products [11]. However, actual usage depends on multiple factors, such as familiarity with relevant technologies, the interface’s accessibility, and the perceived usefulness of the information provided [13]. Additionally, consumers’ value orientation, primarily Ethical–Sustainability Orientation (ESO) and Circular Value Orientation (CVO), may influence how they perceive the DPP and the benefits it provides, and thus their acceptance of the DPP [14]. Given that DPPs ultimately target end consumers, consumer acceptance is crucial for translating transparency into tangible behavioral outcomes that support the goals of the circular economy and sustainability. Identifying what drives consumer acceptance is critical. To this end, this study seeks to answer the following research questions (RQ): RQ1 How do consumers perceive DPP embedded in fashion clothing products? RQ2 How do consumers’ fashion clothing shopping orientation, specifically ESO and CVO, affect their acceptance of DPP? The rest of the paper proceeds with a review of relevant literature to propose a research model and hypotheses, followed by the empirical study. Results are reported, and implications are provided.

2. Literature Review, Research Model, and Hypotheses

2.1. Digital Product Passports in the Fashion Industry

The fashion industry is facing profound ecological, economic, and social challenges driven by overproduction, resource depletion, and opaque supply chains. To address these challenges, the EU has introduced the DPP, which aims to enhance traceability, transparency, and circularity throughout the entire lifecycle of fashion production and consumption [15]. DPP is an electronic record system [5]. It connects products to their origins, materials, manufacturing practices, and lifecycle information, such as maintenance, repair, and ownership history. Users can obtain information via scannable codes or embedded digital tags [6].

DPP transforms product lifecycle data into transparent, accessible information throughout production and consumption, benefiting entities along the supply chain and consumers in the fashion and retail industries. Manufacturers can use DPP to trace the origins of components and improve warranty and recall processes. Retailers can use DPPs to provide transparent product information, including materials, care instructions, and details on chemical treatments, which supports safer handling and enhances repair, resale, and recycling. Business entities along the supply chain, including manufacturers, retail buyers, and consumers, can also rely on DPP data to make more informed, responsible decisions aligned with sustainability and transparency expectations [10].

At the technological level, to support these multi-stakeholder interactions and ensure the reliability of product data, DPP is built upon a robust technological infrastructure that enables real-time tracking, verification, and secure information sharing. For instance, within a Digital Product Passport, a product’s Digital Twin (DT) acts as a virtual replica that continuously collects and updates data throughout its lifecycle [16]. The Internet of Things (IoT) further enables the DPP by linking sensors and smart tags across the supply chain, allowing real-time data capture and exchange that keeps the passport accurate and up to date for manufacturers, retailers, and consumers [17]. Meanwhile, blockchain records data in a peer-to-peer and decentralized manner, ensuring that all information is immutable and tamper-proof, enhancing traceability and preventing counterfeiting [18]. DPPs use data interoperability and information-sharing mechanisms to facilitate multi-stakeholder collaboration [19]. Encryption and selective data disclosure techniques are employed to protect consumers’ and brands’ privacy and security [20]. These technologies enable DPPs to serve as digital bridges across the entire supply and value chain, empowering informed decision-making and supporting the transition to a circular economy. Overall, the technological infrastructure needed to implement the DPP is already in place.

Moreover, at the regulatory level, the EU’s ESPR has incorporated the DPPs into its legal system and will implement them in phases for products entering the EU market through enabling legislation. In the future, foreign companies that cannot provide compliant DPP data will face obstacles in market access and transactions [5].

As the world’s second-largest emitter of carbon, the United States has a significant strategic role to play in encouraging green consumption behaviors and developing circular recycling systems. The DPP provides consumers with transparent, credible information on product traceability and circularity, enhancing product environmental visibility and effectively guiding the public towards more sustainable consumption and recycling decisions. However, current academic research on consumer acceptance of the DPP has primarily focused on European countries, such as Italy [11], Austria [21], and Poland [22], with few empirical studies on US consumers. Notably, interest among US consumers in sustainability and the circular economy has been steadily rising over the past few years. According to Deloitte surveys [23], a growing number of American consumers now view environmental impact as a key factor in their purchasing decisions. Features such as green labels, recyclability of materials, and carbon footprint have become central considerations, and circularity is increasingly embedded in mainstream consumer values. If consumers understand and actively engage with the information provided through DPPs, such as material composition, repair options, recycling pathways, and resale potential, and apply it to their purchasing and product-use behaviors, this could meaningfully enhance both US market competitiveness and environmental performance. Furthermore, broad adoption of DPPs not only supports sustainable development and circular economy principles but also helps US companies better meet the EU’s increasingly stringent environmental compliance requirements in future cross-border trade [24]. Given these strategic implications, understanding the factors that influence US consumers’ willingness to adopt and engage with DPPs has become an urgent priority.

2.2. Theoretical Background

2.2.1. The Technology Acceptance Model (TAM)

The Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), developed by Davis [25], is based on the Theory of Reasoned Action. It highlights the importance of perceived usefulness (PU) and perceived ease of use (PEOU) in determining technology adoption [25]. PEOU is the degree to which a person believes that using the technology will require minimal effort. At the same time, PU is the degree to which the person thinks the technology will enhance their performance or provide value to their task.

TAM has been widely used in empirical studies to predict and explain technology adoption across various settings [26]. At the individual level, examples include applying sustainability labels to apparel products [26], utilizing innovative in-store technologies in retail settings [27], and examining consumers’ acceptance of artificial intelligence–based fashion services [28]. At the organizational level, studies have explored how fashion companies adopt advanced digital systems, such as implementing 3D virtual reality technologies in luxury brand online stores [29]. These studies demonstrate the broad applicability of TAM across organizational and individual contexts, consistently confirming the positive relationships between PU, PEOU, and technology adoption.

However, TAM has limits in different contexts of consumer acceptance [30]. In consumer shopping for fashion clothing, consumers’ perceptions of new technologies or products equipped with technologies, such as functional clothing, depend on their value orientation [31].

2.2.2. Consumer Shopping Orientation: Expanded Dimensions

Consumer orientation reflects individuals’ underlying cognitive and motivational tendencies that guide their purchasing behavior and responses to the market [32]. Consumer orientation is not only behavioral but also psychological, as it is closely associated with an individual’s self-concept, a relatively stable trait that shapes cognition and drives behavior [33]. Consumers with different orientations exhibit distinct behavioral patterns. Traditionally, shopping orientation has been divided into two dimensions [33]: the utilitarian dimension, which emphasizes task efficiency and functionality; and the hedonic dimension, which focuses on experiential satisfaction and emotional pleasure.

However, with growing global awareness of sustainability and the rise in circular economy models, it has become essential to expand these dimensions. Scholars argue that consumer orientation should also integrate environmental, ethical, and social dimensions [34]. Recent studies have extended consumer orientation to include environmentally related and circular-value orientations [35,36]. Empirical evidence demonstrates that these dimensions, including Ethical and Sustainability Orientations, positively impact consumer intentions to engage in ethical behavior, such as supporting green products, fair trade, and socially responsible brands [34].

Consumers who emphasize ethical and sustainable values tend to incorporate moral considerations into their purchasing decisions [37]. As Freestone and McGoldrick [38] noted, green consumers are driven not only by environmental and ecological motives but also by strong self-interests. Moral emotions such as guilt, shame, and empathy are considered key psychological drivers of ethical consumption [39]. Therefore, individuals with strong ethical and sustainability orientations are more likely to engage in sustainable consumption behaviors. Thus, when consumers believe that a product or technology can generate a positive social and ecological impact, their willingness to adopt it increases significantly. Moreover, Colasante, D’Adamo, Desideri, Iannilli and Mangani [11] also emphasize that sustainability information, as a key functional dimension of DPPs, is a crucial factor influencing consumer adoption intentions. When consumers perceive that the sustainability information provided by DPPs aligns with their personal shopping orientations and helps them make more environmentally responsible choices [40], the alignment between values and technological functions can significantly enhance their acceptance, thereby strengthening their overall acceptance of the technology.

Additionally, consumers play a key role in advancing the circular economy by translating its principles into responsible actions throughout a product’s entire lifecycle, from purchase to use and post-use disposal [41]. Consumers with a CVO tend to incorporate product circularity into their decision-making processes across these stages. They focus not only on a product’s appearance, functionality, or price, but also on its resale potential and sustainability throughout its lifecycle. Therefore, resale value has become a key factor in the purchase decisions of consumers with strong circular value orientation.

2.3. Research Model and Hypotheses

While businesses are required to implement DPPs under the EU’s regulatory mandates taking effect in 2024, the broader success of this system ultimately depends on whether consumers perceive the DPP as offering tangible and practical benefits. When consumers recognize its value, they are more likely to accept, use, and engage with the information it provides. Thus, DPP adoption is not solely a matter of understanding the technology or of finding it easy or convenient to use [42]. It is also shaped by consumers’ value orientations, such as ethical beliefs, sustainability awareness, and expectations for corporate transparency and accountability [11,43].

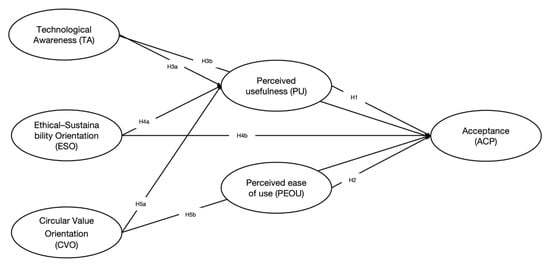

Based on the above literature review, we proposed a research model of consumer acceptance of DPP for fashion clothing consumption, grounded in the integration of the TAM and the extended consumer shopping orientation (see Figure 1). This research conceptualizes consumer acceptance of DPP as the intention to purchase fashion clothing embedded with DPP. Specifically, we propose that consumers’ intentions to adopt DPPs are shaped by two core psychological factors within the TAM framework: PU and PEOU. At the same time, consumers’ shopping orientations, particularly ESO and CVO, along with their familiarity with related technologies, influence how they evaluate the usefulness of DPPs. These factors, in turn, shape their overall acceptance of the DPP.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Framework of DPP Acceptance Model.

2.3.1. Perceived Usefulness and Ease of Use of DPP

When consumers perceive that the product information provided, such as material composition, product origin, recyclability, or carbon footprint, is concise, clear, and actionable, and helps them make more informed and environmentally responsible purchasing decisions, they are more likely to regard the DPP as a useful tool. When the perceived value of a technology is strongly associated with its practical functions, PU has been shown to significantly enhance users’ intention to adopt the technology [25]. Therefore, when consumers perceive that DPPs offer decision-making convenience and environmental value, they are more likely to adopt them.

DPPs play a crucial role in enhancing this value by offering detailed product data, including ownership history and repair records [44]. This level of transparency helps address concerns about counterfeiting and material safety [43], thereby increasing consumer trust and strengthening retailers’ confidence in operating authenticated resale programs by reducing the risks associated with counterfeit or misrepresented goods. Research further shows that the authenticity-verification features within DPPs can significantly enhance consumers’ perceived value and overall interest in secondhand products [25]. Especially with the support of verification technologies such as blockchain, DPPs can offer enhanced data verifiability and transaction transparency for high-value goods, such as luxury products, making their application particularly promising in the secondhand luxury market [30]. Blockchain technology enhances transaction and ownership traceability by adding digital certificates to products, recording their journey from manufacturing to resale, and ensuring product authenticity and transparency [45]. Therefore, if consumers perceive DPP as effective at verifying product authenticity, they will perceive it as highly useful.

PEOU reflects the extent to which consumers believe that using a particular technology is straightforward, easy to understand, and requires minimal effort [25]. If the DPP’s information is well organized and its user interface is intuitive, consumers can access the necessary product data simply by scanning a code or tapping a link. Therefore, their perceived cognitive and time burden will be reduced. The comprehensibility and accessibility of information are recognized as key drivers of the adoption of new technology [46]. When consumers perceive that DPPs offer a smooth user experience and present information intuitively, they are more likely to develop a positive attitude towards using the system, thereby increasing their willingness to adopt it. Based on the above discussion, we propose the following set of Hypotheses (H).

H1.

Perceived usefulness (PU) is positively associated with consumers’ intention to adopt DPPs.

H2.

Perceived ease of use (PEOU) is positively associated with consumers’ intention to adopt DPPs.

2.3.2. Familiarity with Technologies Relevant to DPP

Because DPPs rely on emerging digital infrastructures such as blockchain, IoT, and Digital Twins, consumers’ familiarity with these technologies can shape their perceptions of DPP usefulness. As digital technologies become more common in the fashion industry, technological awareness (TA) has increasingly been recognized as a key factor influencing consumers’ willingness to adopt new systems [47]. In this study, TA refers to an individual’s knowledge and understanding of a technology’s functions, usage, and core features [48,49]. It also includes consumers’ perceptions of a technology’s applicability, its fit with their needs, and their awareness of how it is used in organizational or societal contexts [47]. Thus, TA reflects both familiarity with the technology and the basic ability to understand and navigate it. Prior research has shown that TA directly influences technology adoption [50]. And while strong links between technological awareness and adoption have been established [50], the specific impact of technological awareness on DPP adoption has yet to be thoroughly examined.

Additionally, although technological awareness (TA) can increase consumers’ openness to adopting innovations, this awareness must translate into perceived value to meaningfully affect actual adoption behavior. Cognitive awareness alone does not guarantee acceptance [51,52]. For instance, without a basic understanding of underlying technologies such as blockchain, consumers may not fully recognize the benefits that DPPs offer and may fail to connect these technical capabilities with the practical advantages of using DPPs. Thus, consumers with higher technological awareness are more likely to appreciate the functions and value of DPPs, which in turn increases their likelihood of accepting and adopting them. Based on this reasoning, we propose the following Hypotheses (H):

H3a.

Technological awareness positively influences consumers’ perceived usefulness of DPPs.

H3b.

Technological awareness positively influences consumers’ acceptance of DPP.

2.3.3. Consumer Ethical-Sustainability, and Circular Value Orientations

Consumers’ ethical-sustainability orientation (ESO) and circular value orientation (CVO) align strongly with the DPP’s sustainable value and resale functionality. These two value orientations shape how consumers perceive the DPP in the circular economy and reflect their underlying consumption philosophies [53]. Therefore, when consumers recognize a strong alignment between their personal value orientations and the core functionalities of DPPs, they are more motivated to engage with and learn about the system. As a result, those with stronger ESO and CVO tend to exhibit higher adoption intention.

Specifically, consumers with a strong ESO are more likely to pay attention to a product’s environmental and social impacts. When the DPP’s information aligns with their ethical values, consumers perceive the DPP as more committed to achieving responsible consumption goals. Therefore, they find the DPP more useful and are more willing to adopt it.

Similarly, consumers with a high CVO often prioritize repairable, durable, recyclable products with resale potential. Furthermore, such consumers have first-hand experience of the frustrations caused by information asymmetry in secondhand transactions, such as difficulty verifying authenticity or unclear origins. However, the product lifecycle information, repair history, and resale value included in DPP address their concerns, increasing their intention to adopt it.

In secondhand transactions, consumers often need to repeatedly verify product information to mitigate risks, for example, by checking labels, comparing specifications, or requesting proof of purchase and quality inspection reports from sellers. Such verification typically consumes substantial time and effort. Since the DPP already contains comprehensive, authentic product details, consumers can easily access all the necessary information. The decision-making process becomes more straightforward, with significantly reduced time and effort required, thereby enhancing their PU. Based on the above discussion, we propose the following Hypotheses (H):

H4a.

Ethical–Sustainability Orientation positively influences consumers’ perceived usefulness of DPPs.

H4b.

Ethical–Sustainability Orientation positively influences consumers’ perceived acceptance of DPP.

H5a.

Circular Value Orientation positively influences consumers’ perceived usefulness of DPPs.

H5b.

Circular Value Orientation positively influences consumers’ perceived acceptance of DPP.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Research Instrument

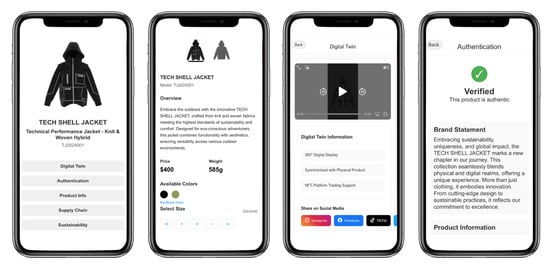

An online survey was developed using https://www.qualtrics.com/. The survey encompassed five sections. The first section assessed individuals’ awareness of DPP-relevant technologies and their purchasing behavior for activewear. The second section of the survey was designed to gather information about consumers’ perceptions of DPP. To enhance the study’s validity and ensure participants clearly understood the core functions of DPPs, a simulated DPP for an activewear product was developed and included in the online survey. The simulated DPP replicated the key interfaces and functionalities of a genuine DPP, including material traceability, repair and maintenance records, authenticity verification, and digital twin integration (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Simulated Activewear DPP Prototype.

Before answering questions about DPP, participants were instructed to review the simulated DPP to familiarize themselves with its purpose and functions, ensuring a clear and consistent understanding of the concept. The simulated DPP was accessible via a QR code or a web link, enabling participants to interact with the product information directly and provide more accurate responses to questions about their perceptions and acceptance of DPP. Questionnaire’s section 3 includes questions about consumers’ value orientations. The last section contains questions about demographic information. Two attention-check questions were added to the Questionnaire’s sections 2 and 3 to improve the quality and accuracy of the collected data.

All measurement items used in this study were adopted or adapted from validated scales in prior research. Specifically, the items for PU and PEOU were adapted from research on the TAM [25]. In the context of DPPs, PU reflects consumers’ perceptions of how DPPs enhance information transparency and support value-driven decision-making. At the same time, PEOU captures the perceived ease with which consumers can access and understand DPP-related information. Items measuring acceptance, operationalized as consumers’ willingness to pay for DPP-enabled products, were adapted from established scales in prior research on behavioral intention and ethical consumption. The first few items were adapted from research focusing on individual behavioral intention to adopt a given technology [25,46,54]. One item was adapted from research in sustainability and fair-trade consumption, focusing on consumers’ willingness to pay a price premium for ethical or environmentally responsible products [55,56]. An additional item that incorporated trust in digital information was adapted from relevant research to assess consumers’ confidence in DPP data [57]. Together, these items capture both the behavioral and economic dimensions of consumer acceptance of transparency technologies in the fashion industry.

The items for assessing ESO were adapted from established scales in ethical and sustainable fashion consumption, emphasizing concerns for responsible production, fair labor practices, and environmental impact [58,59,60]. The CVO items were drawn from research on circular fashion and secondhand consumption, reflecting how consumers evaluate a product’s resale potential and its ability to retain market value over time [61,62,63]. These two constructs together capture both the moral–environmental values and the economic–circular values that influence sustainable fashion consumption.

The TA items were adapted from constructs such as technology readiness, digital literacy, and awareness of emerging technologies, which are widely used in consumer technology and digital transformation research. Each item reflects familiarity with a specific enabling technology relevant to DPPs, including privacy protection, interoperability standards, artificial intelligence (AI), the IoT, QR/NFC access methods, and blockchain. Conceptually, these items align with the Technology Readiness Index (TRI 2.0) proposed by Parasuraman and Colby [64] and are supported by empirical studies examining consumer familiarity with AI and blockchain technologies in fashion and retail contexts [61,65]. The scale is designed to assess the breadth of consumer knowledge required to engage with emerging DPP-related technologies. All constructs were measured using a seven-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree (1)” to “strongly agree (7),” capturing the degree of agreement with each statement.

3.2. Sampling and Sample

The online survey was administered via Prolific, a technology company that creates the largest pool of high-quality, human-derived data for research. We focused on consumers in the United States. A total of 511 responses were collected. After removing incomplete responses, 427 valid cases remained for analysis.

Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the final sample, including gender, age, race, education level, monthly personal income, and monthly fashion spending. The demographic composition of the sample (N = 427) was compared with US Census benchmarks to assess its representativeness. Gender distribution was well-balanced (51.5% male, 47.8% female), closely mirroring national proportions [66]. Racial and ethnic composition was generally consistent with the US population, with 57.0% identifying as White or Caucasian, 9.4% as Black or African American, and 9.4% as Asian; however, the absence of a separate Hispanic/Latino category and the slightly lower proportion of Black respondents suggest partial underrepresentation of these groups [66]. The sample skewed toward middle-aged adults, with the largest cohorts aged 26–45 years (56.9%), while younger (18–25) and older (65+) adults were underrepresented. Educational attainment was notably higher than the national average, with 58.6% holding a bachelor’s or graduate degree compared to roughly 30% nationally, indicating an overrepresentation of more educated individuals. The annual household income distribution was broadly aligned with US norms, with 30.1% earning below $50,000 and 30.5% earning $100,000 or more, reflecting a balanced spread across income levels. Overall, the sample is moderately representative of the US adult population [66], with credible generalizability for gender and income variables but a slight bias in age, education, and ethnicity.

Table 1.

Demographics of participants.

3.3. Data Analysis

Data analysis was conducted using a series of exploratory factor analyses (EFA), confirmatory factor analyses (CFA), and structural equation modeling (SEM). First, EFA was employed to examine the underlying structure of the measurement items. Principal axis factoring with varimax rotation was used to identify the factor structure of all indicators. Next, a maximum likelihood CFA was conducted on the indicators of the six latent variables to further assess the measurement model’s reliability and validity. After confirming satisfactory levels of reliability and validity, the structural model was estimated to evaluate the model fit and test the proposed hypotheses.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics and Results

The survey results indicate that consumer awareness of DPPs remains relatively low. Specifically, 81% of respondents reported never having heard of DPPs before participating in the study, suggesting that DPPs are still in the early stages of promotion and that a significant knowledge gap exists among consumers.

Consumer attitude surveys indicate that 59.0% of respondents were willing to purchase fashion products with DPPs, 58% indicated they would prioritize such products with DPPs in the future, and 61% stated they were likely to continue purchasing them with DPPs. Meanwhile, approximately 24%, 22%, and 24% of respondents remained neutral on the three questions, and 17%, 22%, and 15% expressed disagreement. These results suggest that although some consumers are not yet thoroughly familiar with DPPs, most hold a generally positive, open attitude toward adoption, providing a foundation for broader implementation in the fashion industry.

Furthermore, when considering price factors, consumers tend to be cautious about adopting DPPs. Regarding purchasing DPP-enabled products at a higher price, 38.6% of respondents agreed or somewhat agreed, 16.4% remained neutral, and 45.0% disagreed. When it comes to paying more for trusted DPP products, 38.6% agreed or somewhat agreed, 14.1% stayed neutral, and 47.3% disagreed. Although some consumers see the added value of DPPs, their overall willingness to pay a premium is low, suggesting that price is a significant barrier to adoption.

4.2. Measurement Reliability and Validity

First, the Harman single-factor test was conducted to assess the potential influence of common method variance (CMV) arising from the single data source [67]. The test showed that the first factor explains 38.07% of the variance (below 50%), indicating that there is no threat of common method bias. Also, The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy was 0.90, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (p < 0.001), confirming the data’s suitability for factor analysis. The EFA results supported a five-factor solution. Although six constructs were initially expected based on the theoretical framework, the rotated component matrix showed that all PEOU items exhibited substantial cross-loadings on multiple factors, indicating weak discriminant validity and a lack of clear empirical distinction from other constructs. The overlap produced high inter-factor correlations, resulting in multicollinearity and suggesting that PEOU did not function as an independent latent dimension within the measurement model. From a practical standpoint, ease of use is unlikely to be a major barrier in this context, as scanning a DPP’s QR code is a familiar digital action that has consistently been shown to involve minimal usability challenges [68]. After their removal, the final five-factor structure demonstrated strong explanatory power, accounting for approximately 79.25% of the total variance. Communalities ranged between 0.57 and 0.90, and factor loadings ranged from 0.71 to 0.88, demonstrating strong relationships between items and their respective constructs. All factor EFA and CFA loadings, Cronbach’s alpha, and construct reliability are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Research Constructs and Statistics.

The results of CFA showed that the proposed measurement model achieved a strong model fit, with χ2(177) = 427.339, χ2/df = 2.41, NFI = 0.95, IFI = 0.968, GFI = 0.908, TLI = 0.962, CFI = 0.968, and RMSEA = 0.06. These values fall within the generally accepted cutoff criteria, indicating that the model fits the data well [69]. A summary of the measurement properties is presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Construct Correlations.

The reliability of all constructs was well established, as Cronbach’s alpha values ranged from 0.87 to 0.95, well above the recommended 0.70 threshold [70]. Even with multiple latent factors and a relatively large sample size, the model fit remained strong, further supporting the validity of the measurement structure.

Additionally, both convergent and discriminant validity were confirmed. All CFA loadings ranged from 0.60 to 0.98, exceeding the 0.70 threshold. The average variance extracted (AVE) values ranged from 0.64 to 0.74, surpassing the minimum requirement of 0.50 [70]. These findings demonstrate that each construct is effectively represented by its respective items, offering strong evidence of convergent validity. Discriminant validity between constructs was subsequently assessed using a matrix comparing each construct’s AVE and its squared correlations with other constructs (c.f., Fornell and Larcker [70]). As shown in Table 4, all AVEs exceeded squared correlations ranging from 0.00 to 0.43, indicating that all seven constructs are distinctive.

Table 4.

Summary of Empirical Testing of Hypotheses.

4.3. Hypothesis Testing

Structural equation modeling was conducted to test the proposed model, and the result indicated a good fit (χ2/df = 2.385; GFI = 0.909; CFI = 0.969; RMSEA = 0.057).

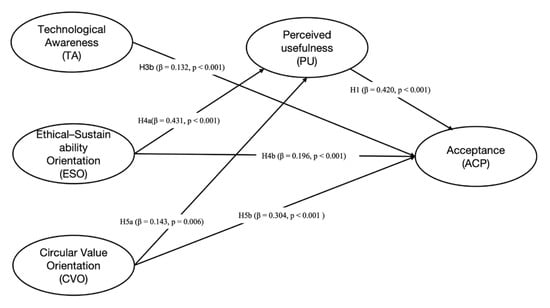

All major fit indices exceeded commonly accepted thresholds, indicating that the hypothesized model appropriately represents the observed data. No critical modification indices were found, confirming the stability and adequacy of the structural model. The statistical results showed that PU had a positive effect on ACP (β = 0.420, p < 0.001), supporting H1. The positive effects of TA on ACP (β = 0.132, p < 0.001) supported H3a. However, the non-significant standard coefficient between TA and PU indicated that H3b was not supported. Also, the positive effects of ESO on PU (β = 0.431, p < 0.001) and ACP (β = 0.196, p < 0.001) supported H4a and H4b. In addition, the positive effects of CVO on PU (β = 0.143, p = 0.006) and ACP (β = 0.304, p < 0.001) supported H5a and H5b (see Table 4). The construct of PEOU was removed from the final measurement model due to substantial cross-loadings across multiple factors; consequently, H2 was removed from the hypothesis testing.

Overall, PU exerted the most substantial total effect on ACP (Standardized Total Effect [STE] = 0.420), followed by ESO (STE = 0.374) and CVO (STE = 0.363), while TA demonstrated the weakest influence (STE = 0.147). In terms of direct effects, PU showed the most significant standardized direct effect (SDE = 0.419), with CVO also exhibiting a meaningful direct influence on ACP (SDE = 0.304). In addition, CVO demonstrated an indirect effect on ACP through PU (Standardized Indirect Effect [SIE] = 0.079). The influence of ESO on ACP was predominantly indirect, with an SIE of 0.202 mediated through PU (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Structural Equation Model Testing Results.

5. Discussion, Implications, and Limitations

5.1. Discussion

DPPs originate in the EU and depend on the EU policy framework. However, their global diffusion is shaped by differences in consumer awareness and willingness to adopt across countries and regions. This study focuses on the US market and the key drivers that influence American consumers’ acceptance of DPPs. The findings suggest that most US consumers are unfamiliar with DPPs. Consequently, they do not understand its practical benefits, leading to a low willingness to pay a premium or adopt it. Therefore, this finding directly addresses RQ1. The low levels of technology awareness and acceptance intention indicate that US consumers may not understand the functional value or economic benefits of DPPs, tend to view adding DPPs to a fashion product as an additional cost, and are hence less willing to accept or pay a premium. Our findings contrast with those of a study by Colasante and D’Adamo in Italy [11], which found that consumers are more willing to pay a premium for products equipped with DPPs. Therefore, consumers’ familiarity and understanding play a decisive role in whether they perceive the DPPs as valuable.

Additionally, because DPP use is mandated by law in the EU but not in the United States, US consumers face less regulatory pressure. Therefore, they may be less motivated to learn about or accept DPPs. At the same time, the results support recent European research on DPPs, which shows that consumers respond more favorably when DPPs provide clear information about product life cycles and environmental impacts [11,21]. These findings further highlight the importance of PU provided by DPPs.

Our findings align closely with the TAM and confirm that PU remains the most critical predictor of adoption [25]. Specifically, our empirical testing results show that consumers focus on whether DPPs deliver clear, tangible benefits. When they perceive greater usefulness of DPPs, they are more likely to accept them. Furthermore, our study also finds that consumer value orientations, such as ethical sustainability orientation and circular value orientation, exert a more substantial influence on acceptance of DPP than TA does. The rationale is that consumer value orientations reflect what consumers genuinely care about and activate motives that feel personally relevant [37]. In contrast, TA only indicates that consumers know what the technology is and does not naturally lead to a willingness to use it. Consumer value orientations shape their perceptions of DPPs. Specifically, when a consumer highly values ethical and sustainable consumption, they value DPP functions, including enhanced traceability, accessible product life extension, repair records, and resale verification. Consequently, consumer ethical and sustainable orientations make PU more salient and increase the likelihood of DPP acceptance. The findings address RQ2 by illustrating the different pathways through which TA and consumers’ value orientation influence their acceptance of DPPs.

Our study findings also highlight two key barriers to DPP adoption among US consumers. First, most consumers are unfamiliar with the concept and purpose of DPPs, making it difficult for them to recognize the benefits DPPs offer. Therefore, increasing public awareness and education about DPPs is essential for promoting adoption. Second, the information presented through DPPs must align with consumers’ value orientations. When the content provided by a DPP does not correspond to consumers’ core concerns or fails to deliver the expected functional value, adoption is less likely.

Overall, the study underscores the pivotal roles of PU and value orientations in influencing US consumers’ willingness to adopt DPPs. These insights deepen our understanding of consumer acceptance mechanisms and provide meaningful theoretical and practical guidance for effectively promoting DPPs in global markets.

5.2. Implications and Limitations

The study makes several significant theoretical contributions. First, the current research shifts the focus from technological and regulatory frameworks to consumer adoption perspectives. Second, while previous investigations have primarily focused on the European context, the present study provides empirical evidence from US consumers, expanding DPP research’s geographical and cultural scope; consequently, it offers a more comprehensive understanding of global adoption dynamics. Furthermore, this study, grounded in the classical TAM framework, extends the model by incorporating consumer value orientation and technology awareness. Our study is the first attempt to apply the TAM to examine DPP consumer adoption. By confirming the core TAM assumption in the DPP context, we demonstrate the decisive role of PU in driving adoption intention. By integrating consumer value orientations as antecedents of TAM factors, our study enhances understanding of how individual value orientations influence technology adoption in the DPP context.

From a practical perspective, this study provides strategic insights for promoting DPPs and identifies key challenges facing their implementation. First, when consumers do not understand the fundamental mechanisms and functions of DPPs, they are unable to accurately evaluate their potential benefits, which, in turn, reduces both adoption intentions and willingness to pay a premium. Therefore, firms, brands, and policymakers should adopt experiential communication and educational strategies to help consumers clearly perceive the concrete advantages that DPPs can provide and to accelerate their understanding of the system’s potential value. At the policy level, establishing unified standards and interoperability frameworks is essential for reducing implementation costs and adoption barriers, as well as for strengthening collaboration among brands, consumers, and regulatory bodies to build a healthy and sustainable technological ecosystem.

The second challenge concerns the alignment between the information presented through DPPs and consumers’ value orientations. DPP information must not only correspond to consumers’ underlying value expectations but also be presented in a concise, clear, and accessible manner. The use of icons, labels, summaries, and other visual tools can help reduce cognitive load and prevent information overload. When DPP information resonates with consumers’ motivations and is delivered in an easily understandable format, abstract sustainability concepts can be translated into concrete, perceivable value, thereby effectively increasing consumers’ willingness to adopt DPPs.

Overall, this study provides theoretical evidence on consumer acceptance of DPPs and practical insights for their implementation. However, this study is subject to several limitations. First, the sample primarily consists of participants from the United States. While this offers insights into non-EU markets, the generalizability of the findings to other countries or cultural contexts remains uncertain and warrants further investigation. Future research could adopt a cross-national comparative design, particularly including consumers from developing regions such as China, India, and Southeast Asia, to explore how regional differences influence the adoption of DPPs.

Furthermore, the study sample is predominantly educated, and their consumption patterns, digital knowledge, and attitudes toward sustainability may not reflect those of the broader population, limiting the generalizability of the findings. Future research should include more demographically diverse samples. Second, the study employs a cross-sectional survey design, which allows for identifying associations between variables but does not support causal inferences. Future research may consider longitudinal or experimental designs to strengthen causal interpretations of the proposed model. Additionally, this study focuses solely on the activewear category. Future research should consider a broader range of product types, such as luxury goods and accessories.

Although this study examined consumers’ behavioral intentions, it did not evaluate their actual adoption behavior. Widespread discrepancies between intentions and actual behavior may threaten the external validity of research findings. Future research should collect behavioral data, such as actual scanning frequency or purchase decisions related to DPPs, to evaluate the predictive power of the TAM. Additionally, this study did not incorporate potential moderating variables, such as consumer knowledge, trust, and hedonic motivations. Including these variables in future studies could enhance TAM’s explanatory and predictive power in the context of DPPs and offer more targeted theoretical guidance for the promotion and marketing strategies of DPP initiatives. Together, these limitations provide valuable directions for future research to explore consumer acceptance of DPP more thoroughly.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.Z. and C.L.; methodology, R.Z.; validation, R.Z. and C.L.; formal analysis, R.Z. and C.L.; data curation, R.Z. and C.L.; writing—original draft preparation, R.Z. and C.L.; writing—review and editing, R.Z. and C.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Louisiana State University Institutional Review Board (protocol code IRBAG-25-0058 and 28 March 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study, in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Niinimäki, K.; Peters, G.; Dahlbo, H.; Perry, P.; Rissanen, T.; Gwilt, A. The environmental price of fast fashion. Nat. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2020, 1, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, K.; Dey, P.K.; Kumar, V. A comprehensive review of circular economy research in the textile and clothing industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 444, 141252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomasset, A.; Benayoun, S. Review: Leather sustainability, an industrial ecology in process. J. Ind. Ecol. 2024, 28, 1842–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Adamo, I.; Gagliarducci, M.; Iannilli, M.; Mangani, V. Fashion Wears Sustainable Leather: A Social and Strategic Analysis Toward Sustainable Production and Consumption Goals. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/energy-climate-change-environment/standards-tools-and-labels/products-labelling-rules-and-requirements/ecodesign-sustainable-products-regulation_en (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Jensen, S.F.; Kristensen, J.H.; Adamsen, S.; Christensen, A.; Waehrens, B.V. Digital product passports for a circular economy: Data needs for product life cycle decision-making. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2023, 37, 242–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weihrauch, D.; Carodenuto, S.; Leipold, S. From voluntary to mandatory corporate accountability: The politics of the German Supply Chain Due Diligence Act. Regul. Gov. 2023, 17, 909–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ESG News. France Targets Ultra-Fast Fashion with Eco-Tax, Ad Ban, and Transparency Rules. ESG News, 17 June 2025. Available online: https://esgnews.com/france-targets-ultra-fast-fashion-with-eco-tax-ad-ban-and-transparency-rules/ (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Zhang, A.; Seuring, S. Digital product passport for sustainable and circular supply chain management: A structured review of use cases. Int. J. Logist. Res. Appl. 2024, 27, 2513–2540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adisorn, T.; Tholen, L.; Götz, T. Towards a Digital Product Passport Fit for Contributing to a Circular Economy. Energies 2021, 14, 2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colasante, A.; D’Adamo, I.; Desideri, S.; Iannilli, M.; Mangani, V. Environmental Concerns in the Fashion Industry: A Twin Transition with the Digital Product Passport. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2025, 34, 9242–9256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voulgaridis, K.; Lagkas, T.; Angelopoulos, C.M.; Boulogeorgos, A.-A.A.; Argyriou, V.; Sarigiannidis, P. Digital product passports as enablers of digital circular economy: A framework based on technological perspective. Telecommun. Syst. 2024, 85, 699–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oesterreich, T.D.; Anton, E.; Hettler, F.M.; Teuteberg, F. What drives individuals’ trusting intention in digital platforms? An exploratory meta-analysis. Manag. Rev. Q. 2024, 75, 3615–3667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elzinga, R.; Reike, D.; Negro, S.O.; Boon, W.P.C. Consumer acceptance of circular business models. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 254, 119988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parliamentary Research Services (EPRS) of the Secretariat of the European Parliament. Digital Product Passport for the Textile Sector; Publications Office of the European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro, J.; Barata, J.; Gentilini, S. A Digital Twin-Based Digital Product Passport. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2024, 246, 4123–4132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowacki, S.; Sisik, G.M.; Angelopoulos, C.M. Digital Product Passports: Use Cases Framework and Technical Architecture Using DLT and Smart Contracts. In Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Distributed Computing in Smart Systems and the Internet of Things (DCOSS-IoT), Corfu, Greece, 19–21 June 2023; pp. 373–380. [Google Scholar]

- Canciani, A.; Felicioli, C.; Severino, F.; Tortola, D. Enhancing Supply Chain Transparency through Blockchain Product Passports. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Pervasive Computing and Communications Workshops and Other Affiliated Events (PerCom Workshops), Biarritz, France, 11–15 March 2024; pp. 751–756. [Google Scholar]

- Thunyaluck, M.; Valilai, O.F. Integrating Digital Product Passports in Multi-Level Supply Chain for enabling Horizontal and Vertical Integration in the Circular Economy. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management (IEEM), Bangkok, Thailand, 15–18 December 2024; pp. 36–42. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.J.; Han, C.H.; Park, K.J.; Moon, J.S.; Um, J. A Blockchain-Based Digital Product Passport System Providing a Federated Learning Environment for Collaboration Between Recycling Centers and Manufacturers to Enable Recycling Automation. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popowicz, M.; Pohlmann, A.; Schöggl, J.-P.; Baumgartner, R.J. Digital Product Passports as Information Providers for Consumers—The Case of Digital Battery Passports. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2025, 34, 7700–7722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeganathan, K.; Szymkowiak, A. Bridging Digital Product Passports and in-store experiences: How augmented reality enhances decision comfort and reuse intentions. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2025, 84, 104242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deloitte. Sustainability Has Staying Power. Available online: https://www.deloitte.com/us/en/insights/topics/environmental-social-governance/sustainable-consumption-trends.html?utm_source.com (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Haase, L.M.; Lythje, L.S.; Skouboe, E.B.; Petersen, M.L. More Than Legislation: The Strategic Benefits and Incentives for Companies to Implement the Digital Product Passport. J. Circ. Econ. 2025, 2, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use, and User Acceptance of Information Technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.J.; Gam, H.J.; Banning, J. Perceived ease of use and usefulness of sustainability labels on apparel products: Application of the technology acceptance model. Fash. Text. 2017, 4, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-Y.; Lee, J.Y.; Mun, J.M.; Johnson, K.K.P. Consumer adoption of smart in-store technology: Assessing the predictive value of attitude versus beliefs in the technology acceptance model. Int. J. Fash. Des. Technol. Educ. 2017, 10, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, G.L.; Zheng, H.; Guo, Y.L. Impact of consumer information capability on green consumption intention: The role of green trust and media publicity. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1247479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altarteer, S.; Charissis, V. Technology Acceptance Model for 3D Virtual Reality System in Luxury Brands Online Stores. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 64053–64062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Lee, M.-Y.; Shen, H. What drives consumers in China to buy clothing online? Application of the technology acceptance model. J. Text. Fibrous Mater. 2018, 1, 2515221118756791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şener, T.; Bişkin, F.; Kılınç, N. Sustainable dressing: Consumers’ value perceptions towards slow fashion. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 28, 1548–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Workman, J.E.; Cho, S. Gender, Fashion Consumer Groups, and Shopping Orientation. Fam. Consum. Sci. Res. J. 2012, 40, 267–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michon, R.; Chebat, J.-C.; Yu, H.; Lemarié, L. Fashion orientation, shopping mall environment, and patronage intentions: A study of female fashion shoppers. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2015, 19, 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Tomșa, M.-M.; Romonți-Maniu, A.-I.; Scridon, M.-A. Is Sustainable Consumption Translated into Ethical Consumer Behavior? Sustainability 2021, 13, 3466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, E.; Gupta, S.; Kim, Y.-K. Style consumption: Its drivers and role in sustainable apparel consumption. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2015, 39, 661–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Gwozdz, W.; Gentry, J. The Role of Style Versus Fashion Orientation on Sustainable Apparel Consumption. J. Macromarketing 2019, 39, 188–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niinimäki, K. Ethical foundations in sustainable fashion. Text. Cloth. Sustain. 2015, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freestone, O.M.; McGoldrick, P.J. Motivations of the Ethical Consumer. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 79, 445–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, K.; Kim, H. Are Ethical Consumers Happy? Effects of Ethical Consumers’ Motivations Based on Empathy Versus Self-orientation on Their Happiness. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 151, 579–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thøgersen, J. Psychological Determinants of Paying Attention to Eco-Labels in Purchase Decisions: Model Development and Multinational Validation. J. Consum. Policy 2000, 23, 285–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, F.; Marullo, C.; Gusmerotti, N.M.; di Iorio, V. Exploring circular consumption: Circular attitudes and their influence on consumer behavior across the product lifecycle. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2024, 33, 6961–6983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slaton, K.; Pookulangara, S. Exploring Consumer Use of Digital Product Passports for Secondary Luxury Consumption: A Conceptual Study. Adv. Consum. Res. 2025, 2, 279–292. [Google Scholar]

- Psarommatis, F.; May, G. Digital Product Passport: A Pathway to Circularity and Sustainability in Modern Manufacturing. Sustainability 2024, 16, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajdinović, S.; Strljic, M.; Lechler, A.; Riedel, O. Interoperable Digital Product Passports: An Event-Based Approach to Aggregate Production Data to Improve Sustainability and Transparency in the Manufacturing Industry. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/SICE International Symposium on System Integration (SII), Ha Long, Vietnam, 8–11 January 2024; pp. 729–734. [Google Scholar]

- Badhwar, A.; Islam, S.; Tan, C.S.L. Exploring the potential of blockchain technology within the fashion and textile supply chain with a focus on traceability, transparency, and product authenticity: A systematic review. Front. Blockchain 2023, 6, 1044723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davis, G.B.; Davis, F.D. User Acceptance of Information Technology: Toward a Unified View. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claudy, M.C.; Michelsen, C.; O’Driscoll, A.; Mullen, M.R. Consumer awareness in the adoption of microgeneration technologies: An empirical investigation in the Republic of Ireland. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2010, 14, 2154–2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mofleh, S.; Wanous, M.; Strachan, P. The gap between citizens and e-government projects: The case for Jordan. Electron. Gov. Int. J. 2008, 5, 275–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingmont, D.N.J.; Alexiou, A. The contingent effect of job automating technology awareness on perceived job insecurity: Exploring the moderating role of organizational culture. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2020, 161, 120302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaksjarvi, M. Consumer Adoption of Technological Innovations. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2003, 6, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, E.; Kim, E.Y.; Lee, E.K. Modeling consumer adoption of mobile shopping for fashion products in Korea. Psychol. Mark. 2009, 26, 669–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watchravesringkan, K.; Nelson Hodges, N.; Kim, Y.H. Exploring consumers’ adoption of highly technological fashion products: The role of extrinsic and intrinsic motivational factors. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2010, 14, 263–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chartrand, T.L. The Role of Conscious Awareness in Consumer Behavior. J. Consum. Psychol. 2005, 15, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodds, W.B.; Monroe, K.B.; Grewal, D. Effects of Price, Brand, and Store Information on Buyers’ Product Evaluations. J. Mark. Res. 1991, 28, 307–319. [Google Scholar]

- Laroche, M.; Bergeron, J.; Barbaro-Forleo, G. Targeting consumers who are willing to pay more for environmentally friendly products. J. Consum. Mark. 2001, 18, 503–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pelsmacker, P. Driesen, Liesbeth, Rayp, Glenn, Do Consumers Care about Ethics? Willingness to Pay for Fair-Trade Coffee. J. Consum. Aff. 2005, 39, 363–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Forsythe, S. Adoption of Virtual Try-on technology for online apparel shopping. J. Interact. Mark. 2008, 22, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joergens, C. Ethical fashion: Myth or future trend? J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2006, 10, 360–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson, M.A. Personal Values, Beliefs, Knowledge, and Attitudes Relating to Intentions to Purchase Apparel from Socially Responsible Businesses. Cloth. Text. Res. J. 2000, 18, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, K.Y.H. Internal and external barriers to eco-conscious apparel acquisition. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2010, 34, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiot, D.; Roux, D. A Secondhand Shoppers’ Motivation Scale: Antecedents, Consequences, and Implications for Retailers. J. Retail. 2010, 86, 355–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turunen, L.L.M.; Leipämaa-Leskinen, H. Pre-loved luxury: Identifying the meanings of secondhand luxury possessions. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2015, 24, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.J.; Lin, L.M. Exploring attitude–behavior gap in sustainable consumption: Comparison of recycled and upcycled fashion products. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 623–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, A.; Colby, C.L. An Updated and Streamlined Technology Readiness Index:TRI 2.0. J. Serv. Res. 2015, 18, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queiroz, M.M.; Fosso Wamba, S. Blockchain adoption challenges in supply chain: An empirical investigation of the main drivers in India and the USA. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 46, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Census Bureau. QuickFacts: United States. Available online: https://data.census.gov/profile/United_States?g=010XX00US (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Tang, D.; Wen, Z. Statistical approaches for testing common method bias: Problems and suggestions. J. Psychol. Sci. 2020, 43, 215–223. [Google Scholar]

- Corsini, F.; Gusmerotti, N.M.; Testa, F.; Frey, M. Exploring the drivers of the intention to scan QR codes for environmentally related information when purchasing clothes. J. Glob. Fash. Mark. 2025, 16, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F. Multivariate Data Analysis; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).