Abstract

The consumer social network plays an important role in the formation of price premiums for agricultural foods. This study focuses on organic milk products and addresses the following questions: First, how does the consumer social network influence the formation of the price premium for organic milk? Second, what is the underlying mechanism of the consumer social network’s effect on this price premium? Despite existing research on social networks and consumer behavior, there is a limited understanding of the specific mechanisms by which social networks impact price premiums for organic goods. To investigate these issues, we utilized a consumption dataset of organic milk provided by CTR Market Research Co., Ltd. (2015–2021) and employed a two-way fixed effects econometric model that incorporates consumer social network density. The findings revealed that the consumer social network has a significant positive impact on the price premium of organic milk products, potentially accelerating the dissemination of knowledge about these products among consumer groups. Furthermore, feedback from friends has a greater influence on the formation of this price premium compared to input from family and relatives. Notably, the price premium exhibits a “U-shaped” relationship with an increase in the distance within the consumer social network. Overall, this paper is likely to contribute to the existing literature and provide marketers with valuable practical insights.

1. Introduction

The organic dairy industry has experienced remarkable growth in recent years, emerging as a significant sector in global agriculture. This growth is particularly notable in China, where consumer demand for organic milk products is rising sharply due to increasing health consciousness and environmental awareness. As reported by the Global Organic Grass-Fed Milk Market Report (2025~2035) issued by WiseGuy Research Consultants, organic milk’s market share is anticipated to grow from less than 1% to over 10% by 2035, emphasizing the economic potential and social relevance of this sector (Data source: https://www.wiseguyreports.com/cn/reports/organic-grassfed-milk-sales-market, accessed on 23 October 2025). Understanding the factors that contribute to this growth, particularly the role of social networks in shaping consumer behavior, is essential for the effective implementation of enterprises’ social network marketing strategies.

Consumer social networks, as platforms for information sharing, have gained significant attention from researchers, particularly concerning their impact on the price premium of organic milk (OM) products. A substantial body of literature emphasizes that these networks increase consumer awareness of the market reputation of OM products. As a result, consumers are more likely to accept the price premium when they encounter positive reviews from peers within their social networks [1]. Zaglia [2] attributes this phenomenon to the informational role of consumer social networks, which enhances consumers’ emotional perceptions of products. Psychological states, such as benign envy, can also influence consumers’ acceptance of the price premium for OM products. According to Van de Ven et al. [3], benign envy encourages consumers to accept higher price premiums for OM offerings, and this psychological effect is amplified within consumer social networks, ultimately driving the price premium [4]. Battle and Diab [5] highlighted that the psychological effect of benign envy contributes to a favorable purchasing experience, paving the way for long-term attachment to products. Chetioui et al. [6] explained how this purchasing experience significantly impacts trust in OM products, which in turn supports their market share and fosters consumer loyalty. Over time, this loyalty plays a crucial role in establishing the price premium of OM products [7]. Our analysis of OM products’ price premium is contextualized within consumer social networks in China.

The competitive landscape of OM retailing in China intensified after October 2007. Gao et al. [8] noted that while OM held a mere 1% share of the Chinese milk powder market in 2007, projections indicate it could exceed 10% by 2035. This increase corresponds with consumers’ trust in product information from organic food certification, which helps mitigate information asymmetry between parties [9]. In this context, a multi-communication channel strategy has emerged as a primary means for retailers to boost OM’s market share. In particular, A multi-communication channel mainly includes the following channel: face-to-face communication (direct conversations and market discussions), digital communication (Email, social media platform), consumer social network and written communication (letters, reports, memos, and newsletters) Mahdi and Afshar [10] define this strategy as a comprehensive plan that businesses implement through various channels, including email, consumer social networks, and phone communications. In the context of multi-communication channel strategy, consumer social network and social media play an important role in the spread of product information in the long term [9]. The execution of this marketing strategy has indeed strengthened sellers’ positions across multiple markets [9,11]. According to Narwal and Nayak [12], the multi-communication channel strategy is pivotal for leveraging price premiums in marketing. Specifically, it allows for the dissemination of extensive information within consumer social networks. This product information encourages consumers who purchase OM products to be willing to pay a higher premium for and trust the organic characteristics of these products [13]. Tariq et al. [14] further explained that this shapes consumers’ perceptions of OM’s brand quality. De Rosa et al. [15] highlighted that multiple communications can expedite the spread of brand information among consumer groups within these communities. Consequently, the price premium of OM products is intricately linked to the social interactions between buyers and sellers, characterized by the social dissemination of information through member interactions, as defined by Yadav et al. [16]. These interactions have led consumers to be willing to pay a premium for OM products [17]. Thus, understanding the dynamics of OM products’ price premiums can illuminate the relationship between consumer social networks and price premiums, offering valuable insights for implementing social network marketing (SNM) strategies. Zaglia [2] defined an SNM strategy as the comprehensive marketing plan aimed at attracting user engagement and enhancing brand awareness. Based on the management targets, the SNM strategy can be divided into social relationship marketing (SRM) and the social guidance of brand (SGB). SRM is designed for maintaining long-term relationships between enterprises and consumers. Meanwhile, SGB is designed for guiding consumers and the general public to form behaviors and attitudes that are consistent with the brand’s values, thereby contributing to the formation of an excellent brand image in the long term [2].

From an implementation perspective, SNM strategies encompass the following steps: (i) defining marketing objectives and target audiences; (ii) designing product information; (iii) selecting information-sharing channels; (iv) allocating marketing budgets and social resources; and (v) managing the marketing process along with market data analysis and evaluation following marketing activities [18]. According to Nobre and Silva [18], the first two steps lay the groundwork for marketing efforts of enterprises. The third step is closely linked to the multi-communication channel strategy, establishing the pathway for the marketing approach. Since consumers often gather brand information via social networks and social media [13], these platforms become critical arenas for the execution of SNM strategies. The final two steps involve the practical implementation and assessment of an enterprise’s SNM strategies over the long term, guiding necessary adjustments to marketing approaches.

As essential channels for information dissemination within a multi-communication strategy [9], social media and consumer social networks have become primary means for sharing product information and expressing consumer sentiments. Therefore, these elements represent significant components of the multi-communication channel strategy [13]. According to Tezer et al. [13], social technology and social relationship are important in social media and social network, respectively, for the user’s information-obtaining behavior. In particular, the analysis of social networks is confined to consumer social networks Social media is defined as the digital technology facilitating user interaction, including three main components: (i) the information infrastructure and tools received by users; (ii) contents of information received by users; and (iii) the main body of information interaction, such as consumers and organizations [19]. A consumer social network refers to the social connections among users who share or receive product information within their social circles [16]. Thus, a consumer social network can be regarded as the social network pattern in which individual consumers are embedded [20]. Here, consumers’ purchasing behavior is mainly affected by information exchange and the imitative behavior of peers in the same social network. Entwisle et al. [21] regarded this as the neighborhood and community impact of social communications between individuals and groups of individuals. Zaglia [2] further noted that the existence of social ties may contribute to the implementation of brand communities by enhancing the information association between consumers and enterprises. Overall, both social media and consumer social networks contribute to sending the product information to consumers participating in the social communication. Together, social media and consumer social networks can potentially enhance the impact of brand information and brand image on users’ purchase decision, including encouraging them to pay a premium for the branded products [22,23,24].

In the OM industry, most studies examining price premiums focus on the effect of social media on this premium [25,26,27]. Dangi et al. [26] analyzed a sample of 91 research studies conducted between 2001 and 2020, encompassing over 15,000 consumers, and discovered a positive correlation between social media use and the price premium of OM products. Trivedi et al. [27] noted that social media enhances consumers’ understanding of the perceived value of OM products, leading them to view the price premium as an indicator of high quality. Chiu et al. [25] found that engagement with social media significantly and positively affects consumers’ personal relevance, which may increase their likelihood of purchasing OM products and their willingness to pay a premium for these items. Clearly, numerous studies have explored the impact of social media on price premiums.

However, while marketing research on the impact of consumer social networks on price premiums, particularly for OM products, is emerging [28]. It remains limited within the business and economics literature. Specifically, there are a few studies examining different modes of consumer social networks in the OM industry [29,30]. Theoretically, although existing research on the social media effect on product price premiums lays a foundation for the effective implementation of social media strategies by enterprises [31], the influence of consumer social networks on product price premiums has not received significant attention from scholars. This gap is likely linked to the way consumers seek product information. Many consumers rely on their social networks to find information and choose the best product combinations, which can affect the product price premium and, consequently, should inform the development of enterprises’ social network marketing (SNM) strategies. This study aims to clarify the relationship between consumer social networks and pricing premium behavior. The findings could provide businesses with valuable insights to effectively market OM products within the context of their SNM strategies, aiding them in leveraging consumer social networks for long-term success.

In this study, we mainly discuss the impact of consumer social networks on the price premium. The consumer social network refers to the social relational network formed through the long-run connections between consumers and other members in the same consumer social network system [20]. The social participation level of consumers can be measured by the consumer social network density [2]. According to Consiglio et al. [32], it is the ratio of the actual number of product purchases to the maximum number of information sources from other directed consumer social network nodes related to some specific consumers. This density can measure the density of the connections among individuals in consumer social networks, thus serving as a proxy for the dissemination efficiency of product information within these networks.

Moreover, with the rising health consciousness among consumers and an increasing demand for high-quality milk, more households are investing in OM products. According to Ho et al. [33], since 2017, the consumption of OM products has constituted approximately 70% of total dietary expenditure on infants in China. Additionally, China’s OM industry represents the third-largest market for milk products, growing at an annual rate of 20%. In 2021, the market value of OM products reached approximately 25 billion USD, compared to 300 billion USD in Russia and over 100 billion USD in the United States [34]. Clearly, the potential size of the OM market is substantial. Therefore, exploring the impact of consumer social networks on OM can enhance our understanding of the pricing strategies of dairy enterprises [35,36,37,38]. Following the approach of Schweimer et al. [39], we constructed the index for consumer social network density and incorporated it into the hedonic analysis of the price premium for the OM products, alongside consumers’ socioeconomic features. Moreover, in line with Ahmad et al. [40], we categorized the consumer social network into three modes: introductions from family (Family_intro), friends (Friend_intro), and relatives (Rel_intro). This classification allows us to decompose the effects based on these various social network modes. Additionally, knowledge diffusion plays a crucial role in enterprises’ marketing strategies [6]. Therefore, we introduce the index of knowledge diffusion (KD) into our mechanism analysis. The KD data is sourced from China’s Statistical Information Service Center (CSISC), which defines it as the consumer score of brand knowledge and brand reputation obtained from household brand knowledge surveys.

Our research is innovative in several respects from an academic perspective: First, by exploring the relationship between consumer social networks and price premiums for OM products, we aimed to connect consumer social interactions with the premium pricing behavior of the enterprises in the OM market, thus revealing an informal institutional mechanism of enterprises’ premium pricing behavior. While most studies focus on the impact of consumers’ socioeconomic status and social media on the formation of price premiums for OM products [25], our research broadens the analytical perspective While most studies focus on the impact of consumers’ socioeconomic status and social media on the formation of price premiums for OM products [25], our research broadens the analytical perspective by examining enterprises’ premium pricing behavior in relation to consumers’ social ties. Additionally, the heterogeneity analysis suggests that the social networks chosen by consumers play varying roles in shaping price premiums. As a result, OM enterprises should implement the SNM strategy tailored to the different information-sharing channels present in consumer social networks. Furthermore, this research highlights the premium-information diffusion effect of these networks, providing a theoretical foundation for the long-term implementation of enterprises’ SNM strategies. Our contributions to practice are significant: the influence of consumer social networks on the price premium of OM products underscores their importance in premium marketing for OM enterprises. Additionally, the varied effects of these networks emphasize their role in executing precise marketing strategies. These insights offer OM enterprises a scientific reference for developing premium pricing policies for their products. Importantly, the information-sharing dynamics within social networks remind enterprises of the need to carefully formulate premium pricing policies influenced by consumer interactions within these networks.

In summary, this study aims to explore the intricate relationship between consumer social networks and the price premium of organic milk products. By filling a notable research gap, we seek to enhance theoretical understanding while providing practical insights for marketers aiming to leverage social networks effectively.

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Theoretical Background

The theoretical framework guiding this research is grounded in Social Network Theory, which emphasizes the structure and dynamics of relationships within a network. This theory, rooted in the work of scholars such as Granovetter and Burt, highlights key principles including the importance of social ties, the flow of information, and the impact of network structure on individuals’ behaviors. By elucidating how social networks operate in practice, we can better understand their role in the consumer decision-making process.

Based on the social network theory, we incorporate the expansion of consumer social networks-alternative food networks as one of its theoretical backgrounds, which demonstrates that connections and interactions between individuals play a crucial role in the dissemination of information, the acquisition of resources, and decision-making behaviors [2]. In the organic milk market, the rise of alternative food networks has provided consumers with a broader range of information sources and platforms for communication, enabling them to gain a deeper understanding of the advantages and characteristics of organic milk. This enhanced understanding increases consumers’ preferences and demand for organic milk, which is one of the key factors driving the price increase in organic milk [29,30]. Thus, as an extension of consumer social networks, alternative food networks offer consumers more choices. The discussions and comparisons of these alternatives within social networks influence consumers’ evaluations of organic milk, thereby affecting the pricing strategies of premium products in the market. Meanwhile, from the perspective of production costs, the stricter production process and higher costs associated with organic milk necessitate higher prices to cover these costs and provide a certain degree of rationality for the price premium [26]. On this basis, enterprises enhance consumers’ awareness and trust in their organic milk products through advertising and brand building, thereby achieving higher price premiums [28]. Correspondingly, we choose alternative food networks and the price premium of organic products as the theoretical foundations of this paper, which helps to reveal the social network mechanisms underlying the formation of price premiums.

2.1.1. The Extension of Consumer Social Network: Alternative Food Networks

From the perspective of social network structure, consumer social network is defined as the collection of social relationships among social agents, representing both the set of social members and their social association [41,42,43], which consist of social ties that influence information dissemination and decision-making behaviors in the marketplace [6]. Recommendations from peers are critical, particularly in navigating price premiums for organic milk, as consumers often rely on peers for trustworthy information [7,8]. From a graph theory perspective, consumer social networks can be regarded as a graph containing social nodes and the social connections linking these nodes [44]. In this graph of the consumer social network, social nodes and social connections are endowed with certain sociological implications. Specifically, social nodes are regarded as an individuals or organizations that can acquire certain social information or resources in a complex business environment. Meanwhile, social connections are the spatial collection of countless pieces of social information [43]. From the perspectives of Burt [45,46], the existence of social connections can promote the flow of social information, thereby establishing the information competitive advantage among individuals. Based on the above ideas, in the field of consumer economics, Granovetter [47] proposed three dimensions when exploring the impact of consumer social network on consumers’ behavior: consumer social network structure, consumer social network relationship, and network location. Consumer social network structure is defined as the stable relational system formed by a group of consumers via specific social relationships (friendships and kinship ties, etc.). This structure has characteristics such as the consumer social network size (the number of social modes), density (degree of concentration of the network), and scale (degree of network coverage). A consumer social network relationship is the relational bonds of consumer individuals via various social interactions (friendship, kinship and work relationship, etc.), encompassing aspects like network intensity (strong and weak ties) and network persistence (degree of persistence of the network). Network location refers to the specific position that consumers occupy within a particular consumer social network structure. This is denoted by network centrality (the influence of social modes in consumer social networks) and structural holes (the ability of heterogeneous information acquisition in consumers’ groups) [47]. Inspired by these thoughts, the concept of consumer social network has been widely introduced into the analysis framework of consumers’ purchasing behavior towards OM, resulting in the theoretical concept of alternative food networks (AFNs) [48].

From the perspective of social capital, it is by Robison et al. [49] and Adler and Kwon [50] defined as the resources and potential advantages that an individual possesses through consumer social network, which includes important elements such as trust, norms, consumer social network relationship, etc. In consumer social networks, the elements of social capital is reflected in the following aspects: Regarding the element of trust, trust generating in consumer social network can be regarded as an essential component of social capital [51]. Consumers establish trust relationships based on historical interactions, shared purchasing experiences or mutual understanding, which contributes to reducing the costs of information-collecting and uncertainty risk during the purchases of products [51]. Concerning the social norms, a norm of mutual assistance might emerge among members living in the same consumer social networks [52]. That is, other members will actively assistance to others in need of advice on product information, which potentially promotes the development of the norm of consumers’ purchasing behavior via information communication among consumers [52]. Regarding the consumer social relationship, the structure of consumer social network determines the distribution and flow of social capital [53]. A highly connected structure of consumer social network potentially means that consumers have increasing opportunities for social interaction, thereby facilitating the effective acquisition and dissemination of product information in the long term [54]. In this process, their purchasing behavior is mainly affected by the consumption behaviors and attitudes of peer members, thereby relying more on product information from consumer social network [55]. This is by Hung and Li [54] attributed to purchasers’ sense of identification with consumer social network system. All in all, consumer social network a complicated system filled with trust, norms, and product information resources, which plays an important role in market consumption behavior in the long term.

As the extension of the concept of consumer social network in the OM industry, AFNs first emerged in the Global North, Feenstra [56] defined AFNs as the enterprises’ production and distribution system of OM products aimed at strengthening social welfare and democracy for all members in the consumer social network. Si et al. [57] termed AFNs as consumers’ selection space of food products in the consumer social network. Within this space, the trust between sellers and buyers can be formed through the organizational mechanism of members’ communication in the specified consumer social network mode [1]. As an important informal social organization for consumers, AFNs can enhance the social ties between buyers and sellers under information asymmetry, thus fostering system transformation and addressing structural holes [58]. This system allows consumers to easily obtain information about the product, thereby resulting in more socially and ecologically sustainable production of OM products. Martindale [59] explained this as the supervisory influence of consumer social networks on enterprises’ production behavior. In this sense, the supervisory influence of AFNs engenders consumers’ product learning skills and trust in food quality by introducing the “consumer-producer” co-governance system, which increases consumers’ social participation in the production process of high-quality products [60]. Specifically, consumers can directly obtain the knowledge about the sources, production methods, and quality of OM products, thus fostering consumers’ trust in the products [14].

From a brand knowledge diffusion perspective, the existence of consumer social network not only makes it easier for consumers to access brand knowledge but also helps them become new “opinion leaders” [1]. In this network, consumers are able to have the novel experience of the brand after using it and share this “personal knowledge” with other members in the same consumer social network. In this sense, consumers are not only the receiver of existing brand knowledge but also the creator and sharer of new brand information in consumer social networks. Here, the latter can be regarded as the knowledge diffusion of brand information, which Maghssudipour et al. [61] defined as the dissemination process of brand information among purchasers in the same consumer social network Concepts related to knowledge diffusion include brand awareness and peer influence. Brand awareness refers to the degree to which consumers remember and recognize a brand and its related elements, such as its name, logo, and slogan [17]. Peer influence is the informational influence or social pressure that an individual experiences from other members of their social network, such as friends, family, and colleagues [10]. Knowledge diffusion and brand awareness or peer influence differ in the following ways: (i) Brand awareness primarily focuses on consumers’ skills to remember and recognize a brand, which means that brand awareness only emphasizes the repetitive reinforcement process of historical brand knowledge in consumers’ mind. (ii) Peer influence focuses on the interaction of individuals within social networks and the changes in their behavior. (iii) Knowledge diffusion is regarded as the combined product of the above-mentioned processes. It not only includes the process of inheriting past brand knowledge but also the production process of new product knowledge based on the consumer social network.

2.1.2. The Price Premium of OM Products

In the business literature, Rao and Bergen [62] narrated the story of a tire and brake retailer from Massachusetts who obtains a higher profit margin, which can be regarded as the extra benefits for a particular transaction. This excess higher price is defined as the price premium in the economics literature [63]. For enterprises who sell branded products, a higher premium demonstrates that they enjoy a higher brand value during the transaction [64]. Because consumers cannot completely understand the quality of branded products, which can be termed as an information asymmetry during the product search [65,66], the price premium emerges as one of the important clues for evaluating brand values (or brand equity) and brand quality in consumers’ memory [67]. This is called as consumers’ price-perception, representing their long-term emotional attitude towards the brand [68]. Therefore, an increasing number of scholars are exploring the price premium mechanisms of branded products, especially for China’s OM products.

Price premiums serve as indicators of perceived quality and brand value in the context of information asymmetry, where consumers rely on pricing as a heuristic for quality judgment [9,10]. Scholars such as Civero et al. [11] as well as Narwal and Nayak [12] reveal that higher price premiums can improve consumers’ perceptions and willingness to pay for organic milk, demonstrating the need for further exploration of the mechanisms through which consumer social networks exert their influence.

Using a social experiment in 32 provinces in China, Gil-Cordero et al. [28] noted that a higher price premium improves consumers’ perceptions of brand quality. Yin et al. [69] explained this as the positive effect of the price premium on consumers’ evaluation of OM products. Xu et al. [70] further pointed out that young consumers with a stronger educational background tend to accept the high price premium of OM products. This finding is consistent with Gao et al. [8], who noted that young consumers focus more on the experience of product purchases led by high price premium. From the view of Gao et al. [8], a high price premium often means that the product has high-quality characteristics. This signal of high quality tends to increase consumer trust in the product, thereby raising the frequency of their purchases. Once product stickiness is established, consumers will obtain a positive psychological purchasing experience from the product’s value and the associated services. For instance, using organic certification labels, OM products with higher price premium can potentially improve their market positioning in consumers’ mind, thereby creating a continuous market demand for OM products via repurchases [71]. Indeed, Xie et al. [72] demonstrated that a higher price premium can help in overcoming the quality information barriers between consumers and OM products by fostering their long-term repurchasing behaviors. El Benni et al. [73] also explored the underlying mechanism of the formation of price premium in the market of OM products and found that this premium can be serve as an indicator of food quality under information asymmetry between sellers and buyers. Thus, the price premium provides an important information sources for consumers when judging the product quality in the purchase process. Akdeniz et al. [74] termed this as the quality signaling mechanism of the product price premium.

From the perspective of social media, The expansion of social networks enable consumers to quickly obtain and share information about the quality of agricultural products, thereby increasing consumers’ awareness and trust in these products [7]. This increase in market trust further amplifies the brand influence of OM products, which potentially boosts the market value of OM products [28,73]. The enhancement of market value gradually accumulates the product’s market reputation, which in turn makes consumers more convinced that the product possesses high-quality attributes [29], which can be explained as the psychological mechanism of risk compensation for consumers when they are uncertain about product quality information [65,66,68].

All in all, by reviewing the literature of price premium, we found that considering price premiums as the dependent variable is particularly pertinent. Price premiums not only capture the economic aspects of consumer decisions but also reflect perceived value, quality, and trust in product claims. This focus provides a clearer understanding of how social networks influence such economic behaviors in the organic dairy market. Although significant progress has been made in various aspects by existing studies, such as the impacts of purchasers’ experience and brand quality on price premium, etc., there are still some obvious shortcomings in the current literature despite significant progress made in various aspects by existing studies. Previous studies mainly focus on the social media effect of OM’s price premium, the impact of consumer social networks on price premium has not been sufficiently explored, especially in the context of the Chinese market of OM products. As the extension of social media, consumer social network are playing an increasingly important role in consumers’ product purchase decisions [18]. Clarifying this issue helps to understand how social networks are integrated into the consumer decision-making process and also aids in the rational formulation of corporates’ SNM strategies. This strategy plays a key role in promoting the sustainable market development of OM enterprises in the long term [13].

2.2. Hypotheses Development

2.2.1. The Impact of Consumer Social Networks on the Price Premium

Based on the above analyses, AFNs refer to a comprehensive system that aim to create more sustainable, local, and equitable food systems by reducing the market distance between producers and consumers, which contributes to promoting diverse and environmentally friendly food production and distribution methods in the long term [56]. In this system, the most effective way to shorten the market distance between consumers and producers is the formation of consumer social networks [59], which affects the brand price premium for OM products through the following pathways:

From an information dissemination perspective, the existence of consumer social networks driven by AFNs can accelerate the spread of OM products’ information among consumer groups, especially the information related to the quality, nutritional composition, and safety of OM products [1]. Facing information asymmetry, consumers often depend on recommendations or market comments from other members in the same consumer social network to make the optimal purchasing decision on OM products; Carfora et al. [75] called this the word-of-mouth (WOM) effect in consumers’ purchasing behavior. For instance, given the importance of infants’ health, consumers may focus more on the high quality and market reputation of OM products [69,76]. Once they receive signals about the high quality of the product from other members within the AFN community, they may be willing to pay the premium for these products [77]. Dwivedi et al. [78] explained this as consumers’ willingness to pay a premium for their trust in brand quality. This trust-based information dissemination can significantly aid OM products, promoting their price premium.

From a brand loyalty perspective, peer recommendations from the consumer social network significantly affect the formation of the price premium of OM products [79,80]. When consumers are satisfied with OM products’ quality, they are not only willing to give high satisfaction ratings but also to make WOM recommendations to other members in the consumer social network. This potentially accelerates the formation of products’ market reputation, thereby enhancing the market loyalty among consumer groups in the long term [48]. The formation of market loyalty towards OM products potentially makes consumers realize the importance of product value and increases their willingness to pay the premium for high-quality OM products to ensure that these products actually have high product quality. Nuttavuthisit and Thøgersen [81] attributed this to consumers’ trust in the market value of OM products behind the high premium. Accordingly, we propose our first hypothesis:

Hypothesis H1.

Consumer social network positively affects OM products’ price premium.

2.2.2. The Knowledge Diffusion Mechanism of the Consumer Social Network Effect of Premium

In the system of AFNs, due to the existence of consumer social network, the spread of brand information tend to be fast among consumer groups, which plays an essential role in the formation of the price premium of OM products [56,82], This is by Maghssudipour et al. [61] explained as the long-term accumulation of trust in consumer social networks by purchasers. The building of market trust makes buyers and sellers place greater trust in the informational value that higher product premiums carry [75]. On the one hand, from the perspective of consumers, the existence of OM’s reference premium information implies some form of price knowledge regarding the perceived pricing process [83,84]. In the consumer social network, the speed of transmission of the reference premium information can be accelerated via the information-sharing by consumers living in the network. Chakraborty and Bhat [85] explained this as the credibility evaluation effect of the consumer social network on the price premium. Dewick and Foster [86] further pointed out that the existence of consumer social network has reshaped the co-evolution of the OM industry and changed the information-procurement channel for OM products. Therefore, the various information-procurement channels can further expand consumers’ information communication and help them make an optimal decision on OM products according to the brand information acquired via the specific consumer social network mode; this is closely associated with pricing-premium policy of OM enterprises [87].

On the other hand, AFNs can contribute to the transformation and upgrading of the common knowledge, the brand information, which is closely associated with the knowledge diffusion [88]. Influenced by this, consumers will renew their understanding of OM products, and dynamically evaluate the products’ brand value based on their usage experiences and the instant information on the brand [89]. Pang et al. [90] called this as the process of self-calibration based on the historical brand information, which helps in building consumers’ brand loyalty [91]. Based on these arguments, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis H2.

The consumer social network effect on price premiums accelerates the dissemination of knowledge about organic milk among consumer groups.

In the above section, we have explored the formation of price premiums from the perspective of the consumer social network, offering a fresh insight into the understanding of organic milk’s (OM) price premium, and have proposed three hypotheses regarding the formation of OM’s price premium. The next section discusses the empirical strategy adopted in this study using the OM consumption dataset provided by CTR Market Research Co., Ltd. We conducted a hedonic analysis of price premium from the lens of consumer social network. The next section outlines the data and methodology. Finally, we have discussed the economic implications of the hedonic regression coefficients results section, which validates our proposed hypotheses, followed by a concluding section. The overall framework of the paper is shown in Figure 1. Based on the AFNs theoretical framework, this paper introduces the variable of consumer social network. This variable is further linked to the price premium of agricultural products, and through the knowledge diffusion mechanism, further reveals the information diffusion mechanism of product premium.

Figure 1.

The conceptual framework of consumer social network effect of premium.

3. Empirical Strategy

We employed a hedonic model to estimate price premiums, utilizing panel data from over 8250 consumers with 27,309 observed purchases from 2015 to 2021. The econometric model accounts for consumer socioeconomic characteristics and the density of consumer social networks.

Next, we have outlined the proposed hedonic empirical method. The study of specific product attributes and their contributions to price premiums has a long-standing tradition, beginning with the work of Rosen [92]. The hedonic regression method has been widely employed in agricultural economics to demonstrate that product attributes significantly influence the price premium of agricultural foods [64,67]. These studies primarily estimate the impact of product attributes and consumers’ socioeconomic characteristics on the price premium of agricultural products.

Following Rosen [92], our hedonic model for the price premium can be specified as follows:

where pct represents the price premium of OM products purchased by consumer c during the purchasing date t; and Z = (z1ct, z2ct, …, zkct) is a vector of hedonic attributes affecting the price premium of OM products purchased by consumer c during the purchasing date t. The subscript k represents the number of influencing attributes determining the price premium of OM products.

Further extending the log-linear hedonic function proposed by Asche and Bronnmann [64], Equation (1) can be elaborated as follows. (The price premium is potentially affected by brand, purchasing date, purchasing place, and product attributes [73]. Here, we mainly explore the relationship between consumer social network and price premium of OM products from the perspective of purchaser individual; hence, we control the variables of these attributes):

In this equation, the pct variable represents the price premium of OM products purchased by consumer c during the purchasing date t, while LAkc encompasses the socioeconomic features about consumer c during the purchasing date t, as displayed in Table 1. The term εct represents the error term. To mitigate potential regression biases stemming from variances in consumers’ purchasing dates and regions, we control for fixed effects related to these factors, as proposed by Asche and Bronnmann [64], corresponding to θt and θregion, respectively.

Table 1.

Description of regression variables.

Next, M(socialct) denotes consumer social network density, which measures influence of the consumer social network on the purchasing behavior of brand products on date t. This density is built through a series of steps: First, we take the logarithm of the quantities of products purchased by consumers and aggregate the purchased quantities of branded products based on the brand variable standards. Second, we quantify the channels of social network information that impact consumer behavior related to OM products (introductions from friends, family, and relatives) and aggregate them according to brand standards. Finally, following Schweimer et al. [39], we derive the formula to compute consumer social network density:

In this formula, the numerator and denominator represent the total number of brand products purchased by consumers and the extent of brand information dissemination in a directed social network, respectively. qict is the quantity of OM products of brand i purchased by consumer c during date t, while Nct represents the number of social network information sources available to consumer c on date t, expressed as follows:

Here, Nict refers to the number of products of brand i purchased by consumer c during on date t; and I denotes the set of brands i in the OM consumption dataset.

We outline the proposed hedonic empirical method. The study of specific product attributes and their contributions to price premiums has a long-standing tradition, beginning with the work of Rosen [92]. The hedonic regression method has been widely employed in agricultural economics to demonstrate that product attributes significantly influence the price premiums of agricultural foods [64,67]. These studies primarily estimate the impact of product attributes as well as consumers’ socioeconomic characteristics on the price premiums of agricultural products.

Furthermore, some consumers acquire OM products through overseas shopping. In such cases, the consumer social network density is zero, as these consumers rely solely on their individual purchasing experiences for product information [93]. Consequently, the issue of left-side truncation in the consumer social network variable persists, potentially leading to inconsistencies in baseline regression results. To address this, we employ maximum likelihood estimation in the Pool-Tobit econometric model while integrating Equation (2). For convenience, we treat the left-side minimal value as the default.

Additionally, from the consumers’ perspective, the channels through which they seek information can significantly influence the price premium of OM products [94]. Over the long term, effective information-seeking channels reduce the difficulty consumers face in obtaining product information, increasing their likelihood of securing high-quality products [95]. Yang et al. [96] further observed that diversifying information-seeking channels fosters consumer loyalty to products through repeated purchasing behavior. Thus, we perform heterogeneity analyses from the viewpoint of information-seeking channels using the following hedonic regression:

where the subscript s can be regarded as the dummy variable of consumer social network modes, corresponds to introduction from friends (Friend_intro, v = 1), family (Family_intro, v = 2), and relatives (Rela_intro, v = 3), respectively.

From the perspective of consumer social networks, the regression coefficients for price premiums may vary with network expansion [97]. Following the approach of Amédée-Manesme et al. [98], we apply the quantile method to the hedonic regression model of OM product price premiums to analyze the dynamic effects of consumer social networks on price premiums. Consequently, the coefficients derived from the estimated hedonic equation can be interpreted as semi-elasticities, with all other features held constant. Thus, we can derive the percentage variation in the price premium attributable to changes in consumer social network variables through the following equation [99]:

Using Equation (5), we implemented the quantile regression method to explore how the price premium of OM products fluctuates with consumer social networks. To mitigate temporal variability in the regression results, we aggregated the quantile regression model based on the purchase date variable, as suggested by Xu et al. [100].

We turn our attention to the endogeneity of the baseline model. First, social ties formed through communication within a stable social environment contribute to the structural stability of the consumer social network among specific consumer groups [101]. To address potential bidirectional causality between the consumer social network and price premiums, we introduce the Economic Policy Uncertainty (EPU) index issued by the South China Morning Post, as proposed by Baker et al. [102], as an instrumental variable, utilizing a two-stage least squares (2SLS) hedonic regression analysis. On one hand, price premiums are subject to shifts in investment conditions, influenced by consumer market expectations [103]. Channa et al. [104] referred to this as the product uncertainty risk premium—consumers’ willingness to pay higher prices for agricultural products during uncertain economic times. As economic uncertainty increases, consumers tend to become more risk-averse, requiring higher premiums to offset potential risks that impact their market expectations. Concurrently, from a business standpoint, economic uncertainty complicates demand-supply relationships, leading to higher premiums due to increased production costs in the long term [105]. Qi et al. [106] have explained the significant role of economic uncertainty in driving up production factors (such as labor and raw materials) and product circulation costs. Thus, our instrumental variable proves to be relevant. On the other hand, the EPU index influences consumer purchasing behavior by shaping their market expectations and is unlikely to correlate with the random disturbance term, thereby satisfying the requirement for exclusivity. Second, the traditional hedonic analysis of price premiums overlooks the sustainability of consumer social networks [107]. To address this, we incorporated the first-order lag term of the consumer social network variable into our 2SLS hedonic regression.

From the perspective of product knowledge dissemination, consumer social networks can facilitate the formation of product knowledge among loyal consumer groups through information-sharing behaviors in alternative food networks (AFNs) [82]. Mastronardi et al. [77] further emphasized that such information-sharing behavior hinges on the smoothness of the communication channels, which aids in acquiring product information related to perceived quality. The revelation of product quality can foster loyalty among consumers, who may then perceive their purchased OM products as possessing assured quality [69]. In this respect, consumers are willing to accept a higher price premium for OM products, which reflects the quality endorsement associated with that premium [91]. Therefore, to maintain the competitive advantage of high premiums for OM products, companies should focus on building a robust product and service system while enhancing product positioning and communication over the long term [91]. Consequently, an increasing number of consumers can drive up the price premium for OM products, particularly through repeat purchasing behaviors [108]. Consequently, an increasing number of consumers can drive up the price premium for OM products, particularly through repeat purchasing behaviors [108]. Hence, we introduced the KD variable into our analysis as follows:

Here, KDct denotes the knowledge diffusion index of consumer c on the purchasing date t, which is derived from the CSISC. KDct measures consumers’ familiarity with brand knowledge, corresponding to the coefficient βD, which measures how the social network affects the degree of brand knowledge diffusion via the price premium.

The dissemination rate of brand knowledge varies significantly across different information-sharing channels within consumer social networks, influenced by the characteristics of the information dissemination channels, user behavior, and content formats [109]. Therefore, we conduct a heterogeneity mechanism analysis based on the different modes of consumer social networks, represented by the dummy variable v. Here, v = 1 corresponds to introductions from friends (Friend_intro), v = 2 to family (Family_intro), and v = 3 to relatives (Rela_intro).

The regression model for the mechanism analysis is specified as follows:

In this equation, the coefficients of and measure the direct impact of the consumer social network and the indirect information diffusion effect of brand knowledge through different network modes. To assess whether the existence of consumer social networks accelerate the spread of brand price premium information among consumer groups, we further constructed a sub-consumer social network index M(netctv) using the following equation proposed by Matsubara et al. [110], Snijders [111] and:

In this context, M(netctv) represents the information diffusion rate within the consumer social network mode for consumer c during the purchasing date t. The terms and represent the average duration of consumer searches for OM brand information and consumer social network mode (v) density for consumer c during the purchasing date t. In particular, Dct variable comes from Tianchi dataset affiliated with Alibaba Research Institute and is captured by Python software (https://www.python.org/). The first term on the right-hand side reflects the proportion of product knowledge obtained by consumers through the specified consumer social network mode. In particular, as in Ma and Zhang [112], the information diffusion rate is defined as the speed at which information spreads through the consumer social network. In particular, based on the assumption of MMa and Zhang [112], we assume that consumers can equally choose any consumer social network (introduction from family, friends, and relatives) to obtain the brand information. Thus, the proportion of product knowledge obtained by consumers via the different networks can be set as 1/3.) The variable can be defined as:

Here, represents the quantity of OM products of brand i purchased by consumer c in the consumer social network mode v (v = 1,2,3); and denotes the total number of brands i products purchased by consumer c during the purchasing date t. The corresponding brand information sources are Friend_intro (v = 1), Family_intro (v = 2), and Rela_intro (v = 3).

4. Data and Methodology

This study utilized a panel dataset comprising more than 8250 consumers, observed monthly from January 2015 to December 2021, resulting in a total of 27,309 observations of consumer purchasing behavior. The dataset included various information such as consumers’ socioeconomic features, purchase location and timing, purchasing methods, product names, brand and sub-brand designations, unit prices (defined as the ratio of amount paid to quantity purchased), product specifications, and product attributes. The socioeconomic characteristics of consumers encompass family size (fs), wages (w), gender, age, and educational level (Edu). Among these, family size, wages, and age are numerical variables, while education and gender are categorical variables. The variables related to purchase location and timing are classified as character variables, and the purchasing method is also a categorical variable. The OM products encompass character variables such as product name, brand, and sub-brand. Data were sourced from China’s Kantar Worldpanel (CKWP), provided by CTR Market Research Co., Ltd., one of the first accredited foreign survey agencies authorized by China’s National Bureau of Statistics. The company has nearly 30 years of experience offering insights into the Chinese market through the use of the Internet and big data technologies, which supports the reliability and validity of the transaction data.

Product attribute variables include product packaging, versioning, category, function, and nutritional composition, among other factors. Product packaging refers to whether the OM products are packaged in cans, boxes, barrels, or pop-top cans. The product version is defined as whether the OM product is produced domestically or imported into specific regions, thus falling into either the general version (Chinese-foreign joint brand) or a special version named after the sales regions (e.g., personalized versions for China, Germany, the U.S., Australia, the U.K., France, and the Netherlands). The nutritional composition and milk quality standards may vary slightly across different versions of the same brand. The product function assesses whether the OM product has been processed with advanced technology (e.g., ordinary, immune, modest hydrolysis, or anti-allergic milk), based on the product’s chemical properties. While product packaging serves as an external characteristic of the OM product, the remaining attributes represent the intrinsic properties of the milk products. These attributes were utilized to construct a comprehensive evaluation system to assess the market competitiveness of milk products.

Specifically, the consumer social network variables and , were derived from the place of purchase and were constructed as follows: First, a text analysis of the purchase locations was conducted. Then, each purchase location (character variable) was assigned specific numerical values, followed by a frequency distribution analysis of these purchase locations. Introduction by friends (v = 1), family (v = 2), and relatives (v = 3) accounts for 94.6% of the entire sample. For ease of constructing the consumer social network index, dimensions were removed according to Snijders’ methodology, leading to the development of M(social_ct) and M(net_ctv).

The hedonic model was estimated for the consumption of OM products in China. Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics for the variables used in the hedonic analysis of the price premium associated with OM products. On average, the per capita annual price premium for households in the sample stands at approximately 229.918 USD per 400 g. Correspondingly, the average consumer income is 2768 USD per person. When analyzing gender, it was observed that OM purchasers predominantly consisted of young females, aligning with findings from Ma and Zhang, which indicate that female consumers exhibit a stronger risk perception compared to their male counterparts. The mean value of the education variable (Edu) is 0.653, suggesting that consumers with a master’s degree show a stronger preference for OM products. The mean values for the social network variables M(social) and M(aggregation) are 17.260 and 0.278, respectively. Notably, the mean value of M(social2) (7.836) surpasses those of M(social1) and M(social3), indicating that consumers tend to base their purchasing decisions for OM products primarily on recommendations from friends. Additionally, M(net1) has a high mean value among the three consumer social network modes (7.836, 2.841, and 1.453), demonstrating highly efficient product information transmission within the sample. The mean value of the knowledge diffusion variable (KD) is 1.661, indicating that the dissemination of brand information drives the price premium of OM products. Finally, the mean values of the economic policy uncertainty (EPU) and lag(social) variables are 1.453 and 0.546, respectively.

Table 2.

Summary of statistics for regression variables.

5. Empirical Results

A summary table outlining key variables, expected directions of effect, and their relation to hypotheses H1 and H2 are shown in Table S1. The hedonic model for the price premium of OM products was estimated using Stata 17, with the results presented in Table 3. To enhance the robustness of the results, a bootstrap process was conducted 600 times within this basic model. The explanatory power of the hedonic model is quite strong, with an R2 of 67.5%. This value rises to 83.1% after incorporating consumers’ socioeconomic status and product attribute variables.

Table 3.

The regression results of baseline model.

In the hedonic model for the price premium of OM products, the estimated coefficients for the M(social) variable are positive at the 5% significance level, supporting hypothesis H1. This indicates that the consumer social network plays a significant role in determining OM’s price premium. Jiumpanyarach [113] demonstrated that consumer social networks enhance understanding of OM product quality and improve consumer trust in these products. Furthermore, Follett [114] emphasized that alternative food networks foster a positive social atmosphere by strengthening ties between buyers and sellers, which encourages businesses to enhance the management practices of “consumer-to-consumer product” processes in the OM industry. Therefore, as influential producers, OM enterprises should focus on developing consumer social networks to foster market connections between buyers and sellers.

The coefficients for consumers’ socioeconomic characteristics are also positive at the 5% significance level, suggesting that socioeconomic status positively influences the price premium for OM products. This aligns with the findings of Huang and Lee [115], who highlighted that consumers with higher social status are willing to pay a premium for OM products. Consequently, businesses should tailor their pricing strategies for OM products based on consumer socioeconomic characteristics. Specifically, factors such as household size (fs) and consumers’ Edu positively impact the price premium for OM, indicating that families with more children and higher educational attainment are more likely to value product price premiums [116]. Additionally, the coefficient for age is lower than that for gender, supporting Sethuraman and Cole’s [117] observation that female consumers are generally more inclined to pay a larger premium than male consumers.

The Pool-Tobit regression results are illustrated in Table 4. As anticipated, the coefficients of M(social) variable indicate that the influence of the consumer social network is positive at the 10% significance level, thus verifying hypothesis H1. Moreover, a comparison of the coefficients for hedonic factors between Table 3 and Table 4 shows that the regression results for the Pool-Tobit and hedonic models are quite similar. This suggests that the issue of left-side truncation is not significant, confirming the consistency and effectiveness of the hedonic estimates for the price premium of OM products.

Table 4.

Robustness results of the baseline model using Pool-Tobit.

Table 5 presents the regression results for Equation (5). As expected, the positive estimated coefficients for the consumer social network provide robust evidence of its effect on the price premium. Notably, the coefficient for the consumer social network within the friend circle (0.590) is greater than those for family and relative circles (0.274 and 0.131, respectively). This suggests that recommendations from friends play a more crucial role in establishing the price premium for OM products, likely due to the stronger influence of friendships within the consumer social network structure [118]. Given the power of word-of-mouth from friends, businesses should strategically market their products or brand within friends’ circles in the consumer social network community.

Table 5.

Heterogeneous analyses of the price premium of OM products.

Notably, the coefficients for consumers’ socioeconomic features related to the friend circle are higher than those for the family and relative circles. Similarly, Zhou et al. [118] found that consumers are likely to make purchasing decisions for OM products based on information from alternative food networks in online settings and friend circles. Follett [114] further noted that alternative food networks can effectively communicate the environmental benefits of OM products, thereby raising consumers’ premium expectations for these products.

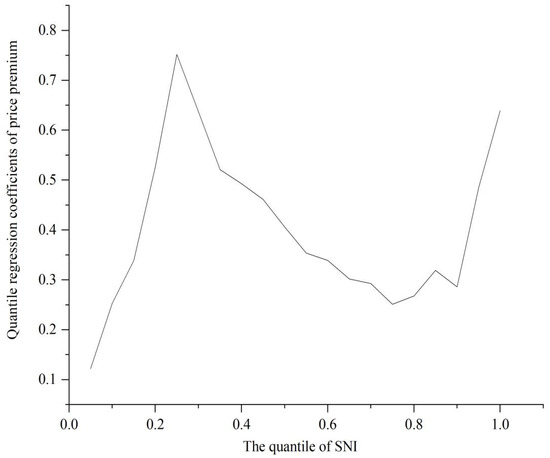

Figure 2 illustrates the regression results for Equation (6) as the proportion of consumer social network increases from 0% to 100%. The quantile regression results are shown in Tables S2 and S3. In particular, the quantile ratio of consumer social network circles is regarded as an indicator of the influence of consumer social network modes among consumers. The change in the price premium can be divided into three stages as the consumer social network influence (SNI) increases. In the first stage, the price premium shows a positive correlation with the consumer social network when SNI is between 0% and 25%. At this point, the price premium reaches its maximum level (0.752) at 25% SNI. Gracia et al. [119] attribute this to the social influence that enhances consumers’ perceptions of agricultural foods. These findings are consistent with Zhang et al. [120], who demonstrated that expanding the consumer social network can lead to increased consumer trust in labels over time, thus boosting the price premium for agricultural products. However, when the SNI proportion ranges from 26% to 75%, the price premium is negatively correlated with the consumer social network, dropping quickly to around 0.250 at the 75% mark. This decline could be attributed to the overwhelming effects of consumer social networks, which may dilute the perceived value of products, resulting in less effective social network marketing over time [121]. During this phase, the consumer social network may paradoxically inhibit product value, prompting brand revitalization through the generation of new product insights. In the third stage (when SNI is between 76% and 100%), the price premium gradually increases from 0.251 to 0.639, suggesting a reinvention of product value within the consumer social network framework [122].

Figure 2.

The changing trend of price premium. Note: SNI is the abbreviation for social network influence. Source: Authors’ calculations.

Goszczyński and Wróblewski [123] argued that this phenomenon occurs due to the evolving structure of the consumer social network, which fosters individual awareness and reduces the psychological distance between branded products and consumers. Therefore, because of the U-shaped nature of the consumer social network’s effects on price premiums, OM enterprises should strategically manage social network marketing to sustain higher price premiums.

Table 6 presents the results of the endogeneity analysis. The coefficients for the M(social) variable indicate a positive association with the price premium at the 10% significance level. Additionally, comparing the consumer social network coefficients in Table 3 and Table 6 reveals that the coefficients in Table 3 are greater than those in Table 6, suggesting that the robustness of the baseline regression is improved by employing the two-step Heckman hedonic regression method. This aligns with the observation that consumers willing to seek product information through consumer social networks are more likely to purchase OM products in uncertain economic conditions [124,125]. Zhou et al. [118] explained this occurrence as the diffusion effect of consumer social networks on consumer trust in agricultural products. Therefore, businesses should develop consumer social network channels to foster product loyalty. Meanwhile, the positive coefficients for economic policy uncertainty (EPU) and Lag(social) variables are insignificant at the 5% level, indicating the exogeneity condition of these variables.

Table 6.

Endogeneity analysis of price premium.

The results of the mechanism analysis are presented in Table 7. The coefficients for the M(social) variable indicate that knowledge diffusion (KD) significantly positively affects the consumer social network’s influence on the price premium, thus supporting Hypothesis H2. Notably, the coefficient for the M(net1) M(social) variable is the highest at 0.349, suggesting that the strength of the friend circle substantially enhances the efficiency of product information transmission, ultimately contributing to the price premium. This finding aligns with Zhou et al. [118], who demonstrated that consumers tend to trust recommendations from friends when making purchasing decisions regarding branded products. Accordingly, OM enterprises should capitalize on the role of social circles to strengthen brand associations between consumers and companies.

Table 7.

Mechanism analysis of price premium.

6. Conclusions

Studies have explored the effect of consumers’ socioeconomic features on the price premium of OM products [79,115,126]. Examining the market of OM products in Taiwan, Huang and Lee [115] found that consumers with higher socioeconomic status have a willingness to pay a premium for OM products. Akaichi et al. [79] explained this as these consumers’ pursuit of health consciousness. Sánchez-Bravo et al. [126] noted that consumers with higher socioeconomic features tend to associate the sustainability of milk product with the price premium, considering it as a symbol of the higher quality of OM products. Still, while marketing studies on the impact of consumer social networks on price premiums are emerging [28], they remain quite limited in the business and economics literature. Although Jiumpanyarach [113] explored how social media affects consumers’ attitude towards the price premium of OM products, social media differs from consumer social networks on technical grounds [13]. This study, taking China’s market of OM products as an example, sets out to explore how consumer social networks influence the formation of price premiums of agricultural foods by employing the hedonic model of price premiums, providing valuable insights for formulating SNM strategies.

This study explored the influence of consumer social networks on the price premium of organic milk (OM) products in China, employing a hedonic model to analyze the relationship between social interactions and pricing behavior. Our findings indicate that consumer social networks significantly enhance the formation of price premiums, emphasizing the importance of peer recommendations, particularly from friends, in driving consumer willingness to pay more for OM products.

6.1. The Theoretical Implications

Overall, the results demonstrate that consumer social networks positively influence the formation of OM’s price premium. Moreover, this effect varies in the different information-seeking channels. Specifically, comments from friends determine the premium of OM products, which was termed by Zhou et al. [118] as the power of friend circles. Next, the results demonstrate that the impact of social networks varies across different channels of information dissemination. Moreover, knowledge diffusion plays a crucial role in reinforcing the price premium effect, particularly within friend-based networks. Notably, as the density of consumer social networks increases, we observe a U-shaped relationship with the price premium, indicating that while social influences initially boost perceived product value, excessive reliance on social networks may dilute the perceived premium.

The objectives of this research were successfully achieved, providing insights that can inform effective social network marketing (SNM) strategies for OM enterprises. Understanding the dynamics of social networks can empower businesses to engage effectively with consumers, enhancing brand associations and loyalty while optimizing pricing strategies.

6.2. The Practical Implications

This study has significant implications for both theory and practice. It contributes to the literature by bridging the gap between consumer behavior and pricing strategies in the context of social networks. For practitioners, it underscores the necessity of integrating consumer social interactions into pricing policies, advocating for tailored marketing strategies that utilize the strengths of various social networks. The following aspects of consumer social network (CSN) structure that would be fruitful for further exploration are:

Investigating how different forms of centrality (e.g., degree, betweenness, closeness) within the CSN influence consumer behaviors and decision-making processes. Understanding the role of central individuals or organizations in disseminating information could elucidate mechanisms that drive price premiums for organic milk.

Exploring various network typologies—such as cohesive subgroups or decentralized networks—can shed light on how the structure of the CSN affects information flow and trust-building among consumers. This analysis could help differentiate the effectiveness of social networks based on their configurations. Analyzing temporal changes in network structures and how they correlate with shifts in consumer perceptions, preferences, and pricing strategies over time could provide deeper insights into the evolving nature of consumer behavior.

6.3. The Agribusiness Implications

Next, we propose agribusiness implications based on our findings. First, given the power from consumer social networks, enterprises should focus on the construction of consumer social network communities to augment the market association between buyers and sellers and enhance consumers’ market participation in the overall enterprise management process. Second, because the consumer social network’s effect on the price premium varies according to the information-procurement channels, enterprises should employ heterogeneous consumer SNM tools aimed at differentiating the specific consumers’ group while implementing the price premium policy. Third, to expand the social influence of branded OM products, enterprises should use the multiple tools in the toolbox of SNM strategies, such as SRM and SGB, depending on the multi-consumer social network mode. Importantly, enterprises should focus on consumers’ market response to price premiums in the context of consumer social networks to avoid diminishing these networks’ influence on the price premium. Specifically, enterprises should use the SNM strategy within the reasonable limits of the consumer social network’s effects.

Crucially, our approach can be applied to research retailers’ premium marketing strategy. First, consumer social network data can be expensive and hard to collect, especially for other food industries. Meanwhile, direct marketing surveys from these industries may help reveal the mutual relationships between the consumer social network and price premium. Second, due to the heterogeneity of the main effect, enterprises should focus on the efficiency of their SNM strategy during the formation of the price premium, which is necessary to maintain the market competitiveness of the branded products [28].

6.4. Limitations and Future Research Directions

This research is not without limitations. First, the findings may not be generalizable for enhancing OM retailing revenues in other countries. Scholars can perform a case study analysis of the effectiveness of OM’s price premium in other contexts and geographies. Second, the price premium is closely associated with the corporate social responsibility (CSR) of enterprises [127], which is not discussed here. Future studies can explore how CSR affects the formation of the price premium of OM products by incorporating the ESG index of the OM enterprise. In addition, the price premium is closely linked to consumers’ purchasing attitudes towards OM on third-party platforms [128,129,130,131]. Future research can combine datasets from online marketing surveys. More importantly, a complex consumer social network structure, differing from the one considered here, can potentially affect consumers’ purchasing behavior [32,124,132]. A mathematical, theoretical analytical framework of consumer social networks can be used to explore such complex structures. This can provide new insights and advance our understanding of the market interaction between consumers and producers. This study presents important implications for marketing strategies in the organic dairy sector, revealing how consumer social networks can drive price premiums. Future research should explore additional variables and contexts to enhance our understanding of consumer behavior in this dynamic market.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su172310847/s1.

Author Contributions

J.H.: Conceptualization, data collection, formal analysis, and writing—original draft; Y.Z.: Literature review, writing—original draft, review and editing; Q.Z.: Conceptualization, formal analysis, supervision, review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by various funding sources including the “Scientific Research Start-up Project for Introduced Talents” of Shanxi Agricultural University [No.2025ZBQ07], Philosophy and Social Science Research Project of Higher Education Institutions in Shanxi [No.2025W013], and Beijing Commercial Development Research Center [No. JD-YB-2022-055] and the Key Program of National Social Science Foundation of China [No. 21ATJ007].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from CTR Market Research Co., Ltd. However, access to these data is restricted, as they were used under license for the current study and are not publicly available. Nonetheless, data can be obtained from the authors upon reasonable request, with the permission of CTR Market Research Co., Ltd.

Acknowledgments

We thank CTR Marketing Research for collaborating with us on this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this paper:

| SNM | Social Network Marketing |

| OM | Organic Milk |

| KD | Knowledge Diffusion |

| AFNs | Alternative food networks |

| CSISC | China’s Statistical Information Service Center |

| SRM | Social relationship marketing |

| SGB | Social guidance of the brand |

References

- Qi, M. Beyond social embeddedness: Probing the power relations of alternative food networks in China. Agric. Hum. Values 2024, 41, 701–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaglia, M.E. Brand communities embedded in social networks. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 216–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Ven, N.; Zeelenberg, M.; Pieters, R. The envy premium in product evaluation. J. Consum. Res. 2011, 37, 984–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, A.; Wang, C.; Akram, U.; Tanveer, Y.; Sohaib, M. Online impulse buying of organic food: Moderating role of social appeal and media richness. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Management Science and Engineering Management, Cham, Switzerland, 5–8 August 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Battle, L.; Diab, D.L. Is envy always bad? An examination of benign and malicious envy in the workplace. Psychol. Rep. 2024, 127, 2812–2832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chetioui, Y.; Lebdaoui, H.; Chetioui, H. Factors influencing consumer attitudes toward online shopping: The mediating effect of trust. EuroMed J. Bus. 2021, 16, 544–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leckie, C.; Dwivedi, A.; Johnson, L.W. Credibility and price premium-based competitiveness for industrial brands. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 74, 103418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Li, C.; Bai, J.; Fu, J. Chinese consumer quality perception and preference of sustainable milk. China Econ. Rev. 2020, 59, 100939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.P.T.; Dang, H.D. Organic food purchase decisions from a context-based behavioral reasoning approach. Appetite 2022, 173, 105975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahdi, H.S.; Afshar, E. Performance of electronic devices for bridging existing information gaps at construction sites: The case of a developing country. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2024, 24, 1510–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Civero, G.; Rusciano, V.; Scarpato, D.; Simeone, M. Food: Not only safety, but also sustainability. the emerging trend of new social consumers. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]