Abstract

Soil organic carbon (SOC) is a key indicator used to evaluate cropping systems, as it reflects long-term productivity, sustainability, and environmental impacts like carbon sequestration. Diversifying crops within intensive farming systems is a possible strategy for enhancing the environmental sustainability of agriculture, resulting in higher rates of SOC accumulation compared to monocultures. This study seeks to evaluate the influence of diversified cropping systems on SOC content at both the field and territorial levels. In Northern Italy, two crop management approaches—one incorporating diversification and one without—were analyzed. The ECOSSE model was employed to simulate changes in SOC content over a 30-year period of diversification, compared with monocropping. The results of the model, first run in available sampling sites, were upscaled to the field to which they belong. Then, using a machine learning approach—namely Random Forest—they were interpolated at the landscape scale, extending the information to an area with similar soil, climate, and management conditions. The maps obtained with this procedure represent valuable tools to assess the long-term effects of crop diversification with legumes on soil C at different scales and can support agricultural policymakers and planners.

1. Introduction

Agricultural systems, along with the challenges they pose for sustainable development, are generally complex. Among soil properties, soil organic carbon (SOC) is a key indicator of soil quality under different cropping systems and is considered a general indicator for assessing soil quality [1]. Soils act as the main terrestrial carbon (C) reservoir, holding a significant amount of the C actively cycled worldwide [2,3,4,5]. While C stored in living biomass contributes only to short-term sequestration, SOC represents a more stable, long-term C storage pathway [6]. As climate change and land use transformations intensify worldwide [7,8], understanding how SOC will respond to shifting environmental conditions has become increasingly important. Reliable information on SOC supports sustainable soil management practices that can reduce production costs, enhance crop yields, and protect the environment [9]. Such information is also especially significant in the context of Sustainable Development Goal target 15.3, which aims to achieve Land Degradation Neutrality (LDN), as established by the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD; http://www.unccd.int).

Agricultural soils experience temporal variations in SOC, influenced also by management strategies, including cropping systems, fertilization, residue handling, and tillage regimes [10,11,12]. Among these, cultivation methods and crop rotations play a central role, as they strongly influence SOC levels and thus the long-term sustainability of farming systems [13,14]. In Italy, agricultural landscapes are largely characterized by cropping systems centered on winter and summer cereals, grown either in monoculture or in short rotations with other rainfed or summer-irrigated crops, such as processing tomatoes, forage crops, or various mixed sequences, which may also include periods of bare fallow [15].

Crop diversification—adding new species or varieties, or adjusting existing rotations—expands the range of crops grown in a given area and often involves integrating additional crops or reducing reliance on external inputs. Cover crops, in particular, are widely recognized as a sustainable practice that limits soil and water losses, increases organic matter, and enhances biodiversity and fertility in degraded agricultural soils [16] while also mitigating the impact of agriculture on climate change [17]. In intensive agricultural systems, crop diversification contributes to environmental sustainability and has been linked to multiple co-benefits, including higher and more stable yields, improved crop quality, and increased system resilience [18,19,20]. It can also boost farm income and contribute to poverty reduction [21]. Overall, diversified farming approaches have demonstrated positive outcomes for food production [22,23], groundwater conservation [24,25], C sequestration [26], and biodiversity protection [22,23,26,27,28]. Kamau et al. [29] found that nearly 47% of the world’s land can support profitable crop diversification strategies.

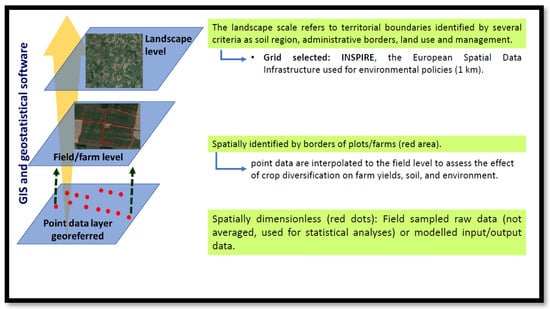

Evaluating the influence of crop diversification on soil–water–atmosphere systems begins at the field scale, where both measured and modeled point data must be scaled up to represent the entire field to understand its effects on farm yields, soil, and the environment. A broader landscape-scale perspective is also needed to support regional planning and to help with a detailed evaluation of agricultural economic and environmental aspects. Extrapolating local observations to wider areas is essential, and mapping tools are useful for identifying zones with similar characteristics. Maps can help policymakers recognize agroenvironmental, social, and economic impacts across territories. To effectively support sustainable regional development, assessments must account for both the geographic context and the diversity of cropping systems [30]. In particular, the effect of diversification in the soil–plant system can be assessed at different scales. SOC variation over time is the crucial aspect for understanding the effect of diversification, much more than single values. Upscaling consists of an increase in scale extent and commonly involves an expansion in spatial coverage accompanied by a lower resolution. Cross-scaling is suitable when the dynamics of processes at a given scale are indirectly influenced by processes occurring at other scales [31].

The use of machine learning (ML) techniques—renowned for their ability to automatically detect complex regression patterns and effectively manage outliers and missing data—has grown significantly in recent years in a variety of scientific domains. In soil science research, nonlinear models can be more effective at capturing the complexity of soil–environment interactions [32]. Thus, pedometrics employs statistical models designed to infer the spatial and temporal distribution of soil from data [33].

The H2020 Diverfarming project (http://www.diverfarming.eu/index.php/en/, accessed on 25 November 2025) intended to promote sustainable, diversified cropping systems with low-input innovative farming practices, adopting a multidisciplinary approach across Europe. In this framework, the aim of this work was to assess how diversified cropping systems can influence SOC content at the territorial level to better understand their potential to support more sustainable outcomes. A case study from Northern Italy is presented, selected to represent the most widespread irrigated and rainfed cereal-based cropping systems in these areas. Here, experimental data were upscaled from field to landscape by an ML (Random Forest) algorithm.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

The research was conducted on a farm situated in the Po Valley, Cremona province, Lombardy region, Northern Italy, an intensive arable land located in the Mediterranean North agroclimatic zone (farm center: 45°04′58″ N 10°26′01″ E), at about 30 m a.s.l. In this area, the mean annual temperature is 13.2 °C, and the mean annual precipitation is 760 mm, mainly occurring in the fall–winter period. Here, highly specialized professional farms for cereals, horticulture, and livestock production are present; current agricultural management practices are characterized by intensive production systems. The area is representative of a cereal-based cropping system, where tomato–durum wheat rotation is the most common farm management. Durum wheat is rainfed, while tomato is irrigated.

The soil in the experimental area has a silty loam texture. The conventional management consists of a 3-year tomato–durum wheat rotation (tomato–tomato–durum wheat), with uncovered soil periods between crop cycles. Current management practices include intense tillage, mineral fertilization, and integrated pest management. Fertilization for durum wheat consists of 40 tons per hectare of digestate, applied in October, plus a total of 100 kg N ha−1 in pre-seeding and top dressing. Tomato is irrigated with 1230 mm ha−1 year−1, distributed from June to August every 3 days, and fertilized with 165 kg N ha−1 at the transplant and as fertigation.

In 2017–2018, a leguminous crop (pea for food) was introduced in the rotation as a diversification strategy, followed by the introduction of tomato after the pea harvest as a multiple-cropping strategy. The diversified crop rotation, therefore, consisted of durum wheat–industrial tomato–pea for food/industrial tomato.

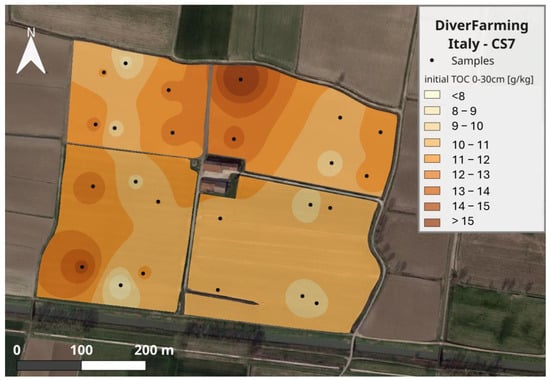

2.2. Field Data Collection and Mapping

The dataset consisted of 24 soil point samples, collected from the experimental field—which had a total area of about 0.2 km2—from the 0–30 cm layer (tilled layer). Samples were collected in October 2017 before the start of the experiment, with the process repeated at the end, in October 2019. The location of sampling points is reported in Figures 2 and 3. All the samples were analyzed for total organic carbon (TOC) by an elemental analyzer (LECO TOC Analyzer, mod. RC-612, St Joseph, MI, USA).

Field maps can support farmers and consultants in understanding the response of crop management at the field level. Usually, a probabilistic (geostatistical) approach is preferable to a deterministic estimator because it treats uncertainty explicitly. In our case, it has been verified that, given the small number of measured points and the limited spatial variability of TOC, a deterministic interpolator provides good spatial estimates with an acceptable global map error. Among deterministic interpolation methods, Inverse Distance Weighting (IDW) is the most commonly applied due to its simplicity and accessibility. It relies on the principle that unsampled point values can be approximated through a weighted average of nearby sampled points, either within a threshold distance or from a set number of closest observations, usually between 10 and 30. Weights are conventionally assigned as an inverse power of distance [34,35]. The estimated map of measured point data at the field scale was drawn by applying the IDW interpolation method to the measured data at time zero. For validating the spatial estimation, the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) was calculated using the following formula:

where (xi) are estimated values, Z(xi) are actual observations, and N is the number of observations. If the interpolator accurately describes the data, the RMSE should be lower or approximately equal to the standard deviation [36].

2.3. Simulation at Field Scale

Originally developed for the simulation of highly organic soils, the ECOSSE model uses a pool-type approach, describing soil organic matter as pools of inert organic matter, humus, biomass, resistant plant material, and decomposable plant material. The model accounts for all principal processes of soil C turnover, simulated by simplified equations requiring only commonly available input data [37]. This facilitates the model’s adaptation from field-scale applications to use as a national-level tool with minimal loss of accuracy. ECOSSE is able to simulate how land use, management, and climate change impact C dynamics. For a complete and more detailed description of the structure and formulation of C dynamics in the model, please refer to Smith et al. [37].

ECOSSE was then modified by adding new subroutines to account for dry soils and to consider multiple cropping, irrigation, and applications of types of manure that were not included in the original version [38]. The model was calibrated according to Smith et al. [37] in a long-term experiment in Southern Italy, observing a good agreement between observed and predicted values (RMSE < 10%) [38]. In this work, the modified version was run to predict the SOC (expressed as TOC) change in soils after a long period of diversification, compared with the same period of conventional farming. Model predictions were performed by running the model with point data corresponding to available soil profiles for a comprehensive view of the effect of crop diversification. For the simulation, we chose a projected climate scenario obtained by the Agri4Cast platform (ETHZ, Intermediate realization of climate change with markedly different precipitation patterns) [39].

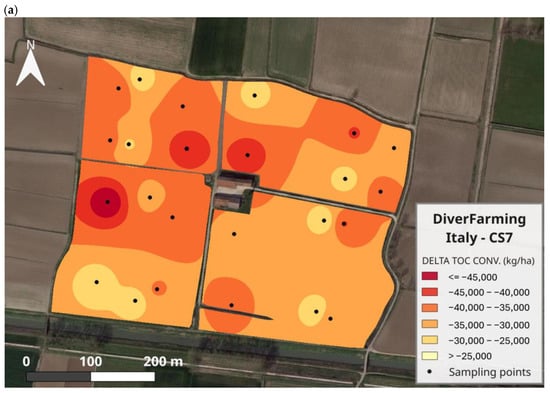

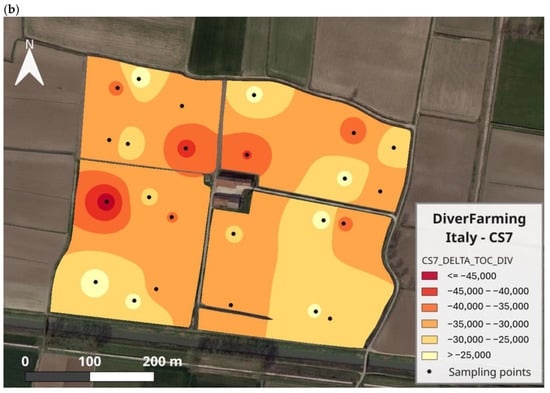

In the experimental field, ECOSSE was run comparing 30 years (from 2018 to 2047) of the conventional farming system and 30 years of diversification, with a monthly time step. Initial TOC values from field measurements taken before the implementation of the diversification treatments were used, ensuring site-specific initialization. Model validation was conducted using the TOC measurements performed after three years of experiment. These simulations gave us the foreseen variations in TOC in each measured point, and these point datasets were then spatialized to the field extent with IDW for a better visual comparison.

2.4. Upscaling at Landscape Scale

Assessing the effects of crop diversification at the landscape scale is essential for informing agricultural planning. Generalization, the standard technique for translating higher-resolution maps to coarser scales, consists of aggregating areas with shared characteristics, largely guided by formal understanding and intuitive reasoning [40]. For upscaling, the support (landscape area of interest) was defined as a continuous area surrounding the experimental site with similar pedological and climatic features. The landscape extent was defined mainly based on the soil region—an area across which soils are relatively uniform—to which the experimental field belongs and on the municipalities (NUTS3) interested in the studied diversification. In our case, the landscape area comprised three provinces—Mantua, Cremona, and Brescia—in the Lombardy Region. The climate was assumed to be the same as the experimental field. In Figure 1, the graphic representation of the adopted procedure is reported.

Figure 1.

Scheme of the multi-scale spatial analysis.

The ECOSSE model was previously conveniently modified to run simultaneously at several spatially distributed points. A tool called MultiECOSSE was developed to run the model efficiently in a batch mode. The simulation was then extended to a set of soil profiles with the same land use (intensive agriculture) in a relatively homogeneous landscape surrounding the experimental area. The information from all the complete soil profiles available for the study area was retrieved from the European Soil Database v. 2.0 (https://esdac.jrc.ec.europa.eu/content/european-soil-database-v20-vector-and-attribute-data, accessed on 25 November 2025). The simulation was performed under two different scenarios: “present”, using the information about the current climate, and “30 years”, considering the modeled results in the next 30 years, again using the ETHZ climate scenario. Point model results for TOC variation were then interpolated at the landscape scale using an ML approach—the “ranger” function in R (version 4.3.3), a fast implementation of Random Forests particularly suitable for high-dimensional data [41]. Then, a set of 15 covariates (standard DEM derivatives of interest to soil mapping), listed in Table 1, was used as auxiliary information in the ML algorithm application. The covariates were selected based on their “importance” in predicting TOC and then converted to principal components to reduce covariance and dimensionality, as well as to fill in all missing pixels [42]. The resulting principal components were related to the target variable by means of the “ranger” function. The output was a prediction map with an associated standard error map that represents the validation step.

Table 1.

Covariates used for the Machine Learning application.

3. Results

In Table 2, descriptive statistics of the measured initial TOC in g kg−1 are reported.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of the initial TOC (g kg−1) dataset in the experimental field.

The map of the measured TOC content in sampling points in the 0–30 cm layer at the beginning of the experiment, spatialized by means of IDW, is reported in Figure 2. Sampling locations are also indicated. The calculated RMSE of this map is 1.64, lower than the standard deviation of the measured TOC data. This supports the choice of IDW as the interpolation method.

Figure 2.

Map of the measured Total Organic Carbon content in the 0–30 cm layer at the beginning of the experiment, spatialized by Inverse Distance Weighting.

Figure 3 presents the maps of the modeled TOC variation after 30 years in the 0–30 cm layer for the two considered scenarios—conventional and diversified management—demonstrating how diversification can mitigate C loss from the soils of the area. Such maps, based on spatial interpolation, can be readily updated as new data become available and can serve as effective tools for monitoring soil–plant system dynamics in relation to the crop management adopted by the farmer.

Figure 3.

Maps of the modeled total organic carbon variation in the 0–30 cm layer after 30 years of (a) conventional management and (b) crop diversification. Spatialization is performed by inverse distance weighting.

Upscaling involves extrapolating values over a larger space; thus, scaling efforts necessarily involve managing the transfer of information among different levels. Switching from the field scale to the landscape scale means lowering the geometric precision to achieve a broader view of the territory. A basic upscaling method consists of extending measurements obtained at a single location to a broader area, but this method does not consider spatial variability. If multiple point locations representing spatial variability are available, they may be aggregated into homogeneous spatial zones based on the type of crops and rotations, soils, and management [52]. A more accurate approach should consider the spatial variability of soil and management.

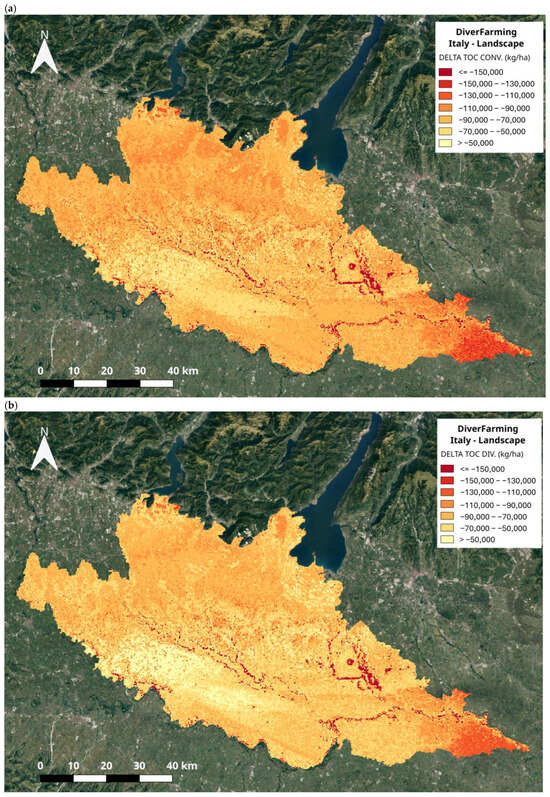

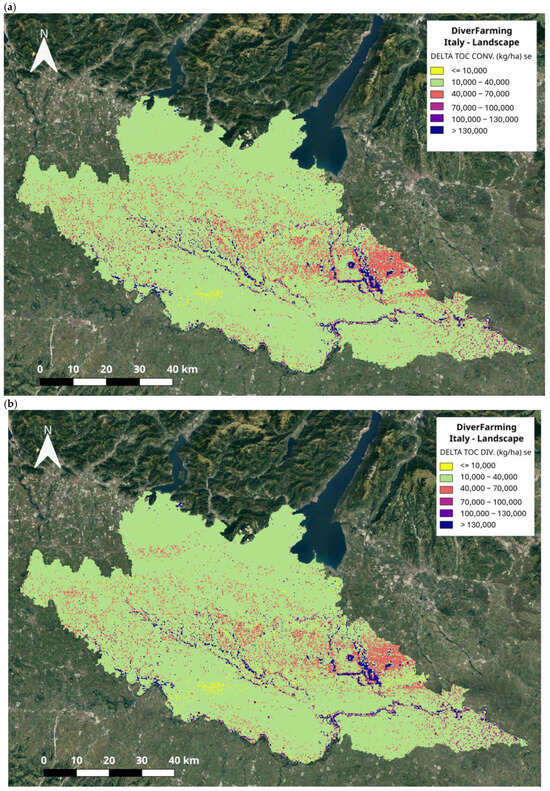

According to Hengl et al. [53], using ML instead of linear regression can considerably improve output data quality. Uncertainties are linked mainly to the quantity and quality of the input data. In Figure 4, the maps of modeled TOC variation in the 0–30 cm layer at landscape scale—both for conventional and diversified management—are shown, and in Figure 5, the maps of the corresponding standard estimation error are reported to corroborate the accuracy of the spatial estimation. Looking at these maps, it is clear how diversification can mitigate C loss from the soils of the area. The differences in soil C loss are likely not substantial, since probably just introducing a cover crop in the rotation is not sufficient to obtain a considerable reduction in such loss. Coupling crop diversification with legumes with other conservative practices (cf. https://www.fao.org/conservation-agriculture/en/, accessed 17 November 2025) can be effective not only in mitigating soil C loss but also in enhancing soil C sequestration.

Figure 4.

Maps of the simulated total organic carbon content variation in the 0–30 cm layer at the landscape scale after 30 years of (a) conventional management and (b) crop diversification.

Figure 5.

Maps of the standard estimation error of modeled total organic carbon content variation in the 0–30 cm layer at landscape scale after 30 years of (a) conventional management and (b) crop diversification.

4. Discussion

Field maps can be considered as a tool to determine the positive or negative impact of a specific crop diversification strategy on soil TOC at the field level. If the effect of the soil–plant system in a portion of the field does not meet the farmer’s expectations, one or more agronomic practices can be adjusted only in that sector, thereby applying a precision agriculture method (for application examples, see [54,55,56]). This can enhance the sustainability of farming, e.g., reducing inputs where they are not necessary.

At the landscape scale, approaches simply based on land use maps can be considered an efficient first-order approximation, but quantitative approaches for preserving the quality of the original information are recommended whenever feasible. Errors might be avoided if upscaling is based on a representative set of known points instead of aggregated data; thus, the availability of reliable soil data in the target area is very important for the success of the upscaling procedure. Nevertheless, there are good reasons to perform upscaling with block support (areal representation of data) because some information, like management data from regional statistics or agronomic models (scenarios), is often available only with block support [52].

Several researchers have demonstrated that the adoption of crop diversification in intensive agricultural systems can represent an important step towards sustainability. In their work, Nicholls et al. [57] found that crop diversification practices such as rotation, intercropping, and multiple cropping favor ecological interactions that help sustain soil fertility, nutrient cycling and retention, water storage, pest and disease control, and pollination, thereby reducing reliance on external inputs and mitigating the effects of—and promoting the adaptation to—climate change. Poeplau and Don [58] considered the use of cover crops as a promising and sustainable method for climate change mitigation, given their relatively high rates of carbon sequestration and the large spatial extent of areas suitable for cultivation. Laamrani et al. [14] concluded that conservation tillage combined with the inclusion of cover crops within crop rotations produced positive effects on topsoil C and may represent appropriate management strategies for enhancing soil fertility and sustainability in agricultural lands. Novara et al. [16] concluded that cover crops represent a positive contribution to the sustainability of agriculture. Locatelli et al. [59] simulated the impact of crop diversification and tillage on SOC dynamics in Brazil up to the year 2070, suggesting that diversified cropping systems may constitute a promising strategy for enhancing SOC sequestration. They also provide important insights for the improvement of current management practices.

Research by Yan et al. [60] contributed to gaining insight into the long-term performance of diversified cropping systems under real-world conditions and climate change, providing actionable information for optimizing crop productivity alongside soil quality in sustainable agriculture. Other researchers have explored the usefulness of maps in evaluating agricultural systems. For example, Heiß et al. [61] generated opportunity maps for highlighting potential improvements in ecosystem services through agricultural management changes at the field level. Oubdil et al. [62] highlighted the value of combining field observations, laboratory analyses, and spatial interpolation techniques to better capture soil variability at the regional scale. Their results confirm the relevance and applicability of mapping for supporting sustainable land management.

In our research, the maps elaborated at the landscape scale represent an additional tool for stakeholders to understand if the crop management diversification has a positive impact on soil, land, biodiversity, and economic aspects in a territory. Moreover, they can help determine if changes in techniques or different types of crops should be applied. In particular, they can show how the application of different crop diversification management can influence a large region.

A limitation of the present study could be that a fixed sampling scheme may not fully capture fine-scale spatial heterogeneity. Although the chosen sampling density is appropriate for the scale and objectives of the model validation, residual small-scale variability may still influence the extrapolation of long-term model results. Another limitation could be the relatively short period of simulation (30 years), which may not fully highlight the long-term trend of soil C variation. Thus, a longer period of observation might be necessary to better define the effect of diversification on soil properties when evaluating the maps. It should be noted that our results refer to the specific context of the Po Valley, and the findings may not be directly extended to other environments with different climatic and/or pedological conditions.

5. Conclusions

The primary objective of this study was to assess the influence of a diversified cropping system on SOC content at a territorial scale, thereby enhancing the understanding of its potential to support more sustainable agricultural outcomes. An integrated procedure was tested in a Northern Italian case study, where a legume was introduced into a cereal-based system. This procedure integrates a model for simulating C dynamics, an interpolation method to extend the results to the field scale, and an ML approach to upscale the model result to a broader landscape.

The maps obtained in this work show the effect of the studied diversification strategy, considering two periods: the present and 30 years onward, predicted by the ECOSSE model. In particular, landscape maps identify areas with similar climatic, soil, and land use characteristics. The results confirm that a spatial assessment with maps at both field and landscape scales seems to be effective in assessing the long-term effect of crop diversification with legumes on soil C at different scales. This can help stakeholders obtain a quick overview of the impact of crop diversification management on farms and on the territory. This assessment can also help to identify issues and opportunities for crop diversification to improve sustainable management towards a more resilient agriculture. Adopting crop diversification together with other conservation practices can be effective not only in mitigating soil C loss but also in enhancing soil C sequestration.

In conclusion, this work supports the role of diversified cropping systems in improving soil health and contributing to regional climate change mitigation. Since a longer period of observation may be necessary to better define the effect of diversification on soil properties, further investigation is desirable. However, the applicability of our findings to other regions should be considered with caution, and future research could be conducted applying the procedure in different pedoclimatic zones.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.F., C.P., S.V., and C.D.B.; methodology, A.M., C.D.B., and C.P.; data curation, R.F. and C.D.B.; mapping, A.M. and C.P.; writing—original draft preparation, C.P.; writing—review and editing, C.D.B.; supervision, R.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme, Diverfarming project, grant agreement No. 728003.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data available in a publicly accessible repository. The original data presented in the study are openly available in Zenodo at https://zenodo.org/records/3685753 (accessed 17 November 2025).

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Marianna Cerasuolo and Khadiza Begum for performing the simulations with ECOSSE.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SOC | Soil Organic Carbon |

| TOC | Total Organic Carbon |

| IDW | Inverse Distance Weighting |

| ML | Machine Learning |

References

- Stolbovoy, V.; Montanarella, L.; Filippi, N.; Jones, A.; Gallego, J.; Grassi, G. Soil Sampling Protocol to Certify the Changes of Organic Carbon Stock in Mineral Soil of the European Union, 2nd ed.; EUR 21576 EN/2; Office for Official Publications of the European Communities: Luxembourg, 2007; p. 56. Available online: https://esdac.jrc.ec.europa.eu/ESDB_Archive/eusoils_docs/other/EUR21576_2.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2025)ISBN 978-92-79-05379-5.

- Janzen, H.H. Carbon cycling in earth systems—A soil science perspective. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2004, 104, 399–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, R. Soil carbon sequestration impacts on global climate change and food security. Science 2004, 304, 1623–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scharlemann, J.P.; Tanner, E.V.; Hiederer, R.; Kapos, V. Global soil carbon: Understanding and managing the largest terrestrial carbon pool. Carbon Manag. 2014, 5, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva Neto, E.C.; Coelho-Junior, M.G.; Horák-Terra, I.; Gonçalves, T.S.; Anjos, L.H.C.; Pereira, M.G. Organic soils: Formation, classification and environmental changes records in the highlands of southeastern Brazil. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddique, K.H.M.; Bolan, N.; Rehman, A.; Farooq, M. Enhancing crop productivity for recarbonizing soil. Soil Tillage Res. 2024, 235, 105863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biskaborn, B.K.; Smith, S.L.; Noetzli, J.; Matthes, H.; Vieira, G.; Streletskiy, D.A.; Schoeneich, P.; Romanovsky, V.E.; Lewkowicz, A.G.; Abramov, A.; et al. Permafrost is warming at a global scale. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, K.; Fuchs, R.; Rounsevell, M.; Herold, M. Global land use changes are four times greater than previously estimated. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 2501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouasria, A.; Namr, K.I.; Rahimi, A.; Ettachfini, E.M. Geospatial Assessment of Soil Organic Matter Variability at Sidi Bennour District in Doukkala Plain in Morocco. J. Ecol. Eng. 2021, 22, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolan, S.; Clapp, C.; Allmaras, R.; Baker, J.; Molina, J. Soil organic carbon and nitrogen in a Minnesota soil as related to tillage, residue and nitrogen management. Soil. Tillage Res. 2006, 89, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wesemael, B.; Paustian, K.; Meersmans, J.; Goidts, E.; Barancikova, G.; Easter, M. Agricultural management explains historic changes in regional soil carbon stocks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 14926–14930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knotters, M.; Teuling, K.; Reijneveld, A.; Lesschen, J.P.; Kuikman, P. Changes in organic matter contents and carbon stocks in Dutch soils, 1998–2018. Geoderma 2022, 414, 115751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.-H.; Wade, T.; Brym, Z.; Ogisma, L.; Bhattarai, R.; Bai, X.; Bhadha, J.; Her, Y. Assessing the agricultural, environmental, and economic effects of crop diversity management: A comprehensive review on crop rotation and cover crop practices. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 387, 125833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laamrani, A.; Voroney, P.R.; Berg, A.A.; Gillespie, A.W.; March, M.; Deen, B.; Martin, R.C. Temporal Change of Soil Carbon on a Long-Term Experimental Site with Variable Crop Rotations and Tillage Systems. Agronomy 2020, 10, 840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Bene, C.; Marchetti, A.; Francaviglia, R.; Farina, R. Soil Organic Carbon Dynamics in Typical Durum Wheat-Based Crop Rotation of Southern Italy. Ital. J. Agron. 2016, 11, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novara, A.; Cerda, A.; Barone, E.; Gristina, L. Cover crop management and water conservation in vineyard and olive orchards. Soil Tillage Res. 2021, 208, 104896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keesstra, S.; Nunes, J.; Novara, A.; Finger, D.; Avelar, D.; Kalantari, Z.; Cerdà, A. The superior effect of nature based solutions in land management for enhancing ecosystem services. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 610–611, 997–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilman, D.; Balzer, C.; Hill, J.; Befort, B.L. Global food demand and the sustainable intensification of agriculture. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 20260–20264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isbell, F.; Adler, P.R.; Eisenhauer, N.; Fornara, D.; Kimmel, K.; Kremen, C.; Letourneau, D.K.; Liebman, M.; Polley, H.W.; Quijas, S.; et al. Benefits of increasing plant diversity in sustainable agroecosystems. J. Ecol. 2017, 105, 871–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, J.A.; Suter, M.; Haughey, E.; Hofer, D.; Lüscher, A. Greater gains in annual yields from increased plant diversity than losses from experimental drought in two temperate grasslands. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2018, 258, 149–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danso-Abbeam, G. Crop diversification and multidimensional poverty in rural Ghana: The empirical linkages. Sustain. Fut. 2025, 10, 101122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beillouin, D.; Ben-Ari, T.; Malézieux, E.; Seufert, V.; Makowski, D. Positive but variable effects of crop diversification on biodiversity and ecosystem services. Glob. Change Biol. 2021, 27, 4697–4710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Chen, J.; Beillouin, D.; Lambers, H.; Yang, Y.; Smith, P.; Zeng, Z.; Olesen, J.E.; Zang, H. Global systematic review with meta-analysis reveals yield advantage of legume-based rotations and its drivers. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Steenhuis, T.S.; Davis, K.F.; van der Werf, W.; Ritsema, C.J.; Pacenka, S.; Zhang, F.; Siddique, K.H.M.; Du, T. Diversified crop rotations enhance groundwater and economic sustainability of food production. Food Energy Secur. 2021, 10, e311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Xiong, J.; Yang, B.; Yang, X.; Du, T.; Steenhuis, T.S.; Siddique, K.H.M.; Kang, S. Diversified crop rotations reduce groundwater use and enhance system resilience. Agric. Water Manag. 2023, 276, 108067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamburini, G.; Bommarco, R.; Wanger, T.C.; Kremen, C.; van der Heijden, M.G.A.; Liebman, M.; Hallin, S. Agricultural diversification promotes multiple ecosystem services without compromising yield. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaba1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Himmelstein, J.; Ares, A.; Gallagher, D.; Myers, J. A meta-analysis of intercropping in Africa: Impacts on crop yield, farmer income, and integrated pest management effects. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2016, 15, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.K.; Sánchez, A.C.; Juventia, S.D.; Estrada-Carmona, N. A global database of diversified farming effects on biodiversity and yield. Sci. Data 2021, 8, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamau, H.; Roman, S.; Biber-Freudenberger, L. Nearly half of the world is suitable for diversified farming for sustainable intensification. Commun. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopin, P.; Blazy, J.C.; Guindé, L.; Tournebize, R.; Doré, T. A novel approach for assessing the contribution of agricultural systems to the sustainable development of regions with multi-scale indicators: Application to Guadeloupe. Land Use Policy 2017, 62, 132–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, W.W.L.; Rondinini, C.; Avtar, R.; van den Belt, M.; Hickler, T.; Metzger, J.P.; Scharlemann, J.P.W.; Velez-Liendo, X.; Yue, T.X. Linking and harmonizing scenarios and models across scales and domains. In IPBES: The Methodological Assessment Report on Scenarios and Models of Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services; Ferrier, S., Ninan, K.N., Leadley, P., Alkemade, R., Acosta, L.A., Akçakaya, H.R., Brotons, L., Cheung, W.W.L., Christensen, V., Harhash, K.A., et al., Eds.; Secretariat of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform for Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services: Bonn, Germany, 2016; Available online: https://files.ipbes.net/ipbes-web-prod-public-files/downloads/pdf/2016.methodological_assessment_report_scenarios_models.pdf (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Huang, H.; Yang, L.; Zhang, L.; Pu, Y.; Yang, C.; Wu, Q.; Cai, Y.; Shen, F.; Zhou, C. A review on digital mapping of soil carbon in cropland: Progress, challenge, and prospect. Environ. Res. Lett. 2022, 17, 123004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBratney, A.; de Gruijter, J.; Bryce, A. Pedometrics timeline. Geoderma 2019, 338, 568–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrough, P.A. Principles of Geographical Information Systems for Land Resources Assessment; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, D.F. Contouring: A Guide to the Analysis and Display of Spatial Data; Pergamon Press: Oxford, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Shmueli, G.; Bruce, P.C.; Stephens, M.; Patel, N.R. Data Mining for Business Analytics: Concepts, Techniques, and Applications with JMP Pro, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J.; Gottschalk, P.; Bellarby, J.; Richards, M.; Nayak, D.; Coleman, K.; Hillier, J.; Flynn, H.; Wattenbach, M.; Aitkenhead, M.; et al. Model to Estimate Carbon in Organic Soils—Sequestration and Emissions (ECOSSE). User-Manual. 2010. Available online: https://www.abdn.ac.uk/staffpages/uploads/soi450/ECOSSE%20User%20manual%20310810.pdf (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Begum, K.; Zornoza, R.; Farina, R.; Lemola, R.; Alvaro-Fuentes, J.; Cerasuolo, M. Modeling soil carbon under diverse cropping systems and farming management in contrasting climatic regions in Europe. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 819162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duveiller, G.; Donatelli, M.; Fumagalli, D.; Zucchini, A.; Nelson, R.; Baruth, B. A dataset of future daily weather data for crop modelling over Europe derived from climate change scenarios. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2017, 127, 573–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heuvelink, G.B.M.; Webster, R. Modelling soil variation: Past, present and future. Geoderma 2001, 100, 269–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hengl, T.; MacMillan, R.A. Predictive Soil Mapping with R; OpenGeoHub Foundation: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2019; Available online: https://soilmapper.org/statistical-theory.html (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Olaya, V. Basic Land-Surface Parameters. In Geomorphometry: Concepts, Software, Applications; Hengl, T., Reuter, H.I., Eds.; Developments in Soil Science; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2006; Volume 33, pp. 141–169. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, J.P.; Gallant, J.C. (Eds.) Terrain Analysis—Principles and Applications; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Anders, N.S.; Seijmonsbergen, A.C.; Bouten, W. Multi-Scale and Object-Oriented Image Analysis of High-Res LiDAR Data for Geomorphological Mapping in Alpine Mountains. In Proceedings of the Geomorphometry, Zurich, Switzerland, 31 August–2 September 2009; pp. 61–65. [Google Scholar]

- Prima, O.D.A.; Echigo, A.; Yokoyama, R.; Yoshida, T. Supervised landform classification of Northeast Honshu from DEM-derived thematic maps. Geomorphology 2006, 78, 373–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoyama, R.; Shirasawa, M.; Pike, R.J. Visualizing topography by openness: A new application of image processing to digital elevation models. Photogramm. Eng. Remote Sens. 2002, 68, 257–265. [Google Scholar]

- Boehner, J.; Koethe, R.; Conrad, O.; Gross, J.; Ringeler, A.; Selige, T. Soil Regionalisation by Means of Terrain Analysis and Process Parameterisation. In Soil Classification 2001; Micheli, E., Nachtergaele, F., Montanarella, L., Eds.; Research Report No. 7, EUR 20398 EN; European Soil Bureau: Luxembourg, 2002; pp. 213–222. [Google Scholar]

- Boehner, J.; Selige, T. Spatial prediction of soil attributes using terrain analysis and climate regionalisation. In SAGA—Analysis and Modelling Applications; Boehner, J., McCloy, K.R., Strobl, J., Eds.; Goettinger Geographische Abhandlungen: Goettingen, Germany, 2006; Volume 115, pp. 13–28. [Google Scholar]

- Gallant, J.C.; Dowling, T.I. A multiresolution index of valley bottom flatness for mapping depositional areas. Water Resour. Res. 2003, 39, 1347–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, M.C.; Potapov, P.V.; Moore, R.; Hancher, M.; Turubanova, S.A.; Tyukavina, A.; Thau, D.; Stehman, S.V.; Goetz, S.J.; Loveland, T.R.; et al. High-Resolution Global Maps of 21st-Century Forest Cover Change. Science 2013, 342, 850–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewert, F.; van Ittersum, M.K.; Heckelei, T.; Therond, O.; Bezlepkina, I.; Andersen, E. Scale changes and model linking methods for integrated assessment of agri-environmental systems. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2011, 142, 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hengl, T.; Mendes de Jesus, J.; Heuvelink, G.B.M.; Ruiperez Gonzalez, M.; Kilibarda, M.; Blagotić, A.; Shangguan, W.; Wright, M.N.; Geng, X.; Bauer-Marschallinger, B.; et al. SoilGrids250m: Global gridded soil information based on machine learning. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0169748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suleymanov, A.; Abakumov, E.; Suleymanov, R.; Gabbasova, I.; Komissarov, M. The Soil Nutrient Digital Mapping for Precision Agriculture Cases in the Trans-Ural Steppe Zone of Russia Using Topographic Attributes. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2021, 10, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roma, E.; Laudicina, V.A.; Vallone, M.; Catania, P. Application of Precision Agriculture for the Sustainable Management of Fertilization in Olive Groves. Agronomy 2023, 13, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qaswar, M.; Mouazen, A.M. Precision application of combined manure, compost and nitrogen fertilizer in potato cultivation using online vis-NIR and remote sensing data fusion. Smart Agric. Technol. 2025, 12, 101328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, C.I.; Altieri, M.A.; Vazquez, L. Agroecology: Principles for the Conversion and Redesign of Farming Systems. J. Ecosys. Ecograph. 2016, 1, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poeplau, C.; Don, A. Carbon sequestration in agricultural soils via cultivation of cover crops—A meta-analysis. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2015, 200, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locatelli, J.L.; Del Grosso, S.; Silva Santos, R.; Hong, M.; Gurung, R.; Stewart, C.E.; Cherubin, M.R.; Bayer, C.; Cerri, C.E.P. Modeling soil organic matter changes under crop diversification strategies and climate change scenarios in the Brazilian Cerrado. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2025, 379, 109334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Xu, Y.; Chu, J.; Guillaume, T.; Bragazza, L.; Li, H.; Shen, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zeng, Z.; Zang, H. Long-term diversified cropping promotes wheat yield and sustainability across contrasting climates: Evidence from China and Switzerland. Field Crops Res. 2025, 322, 109764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiß, I.; Stegmann, F.; Wolf, M.; Volk, M.; Kaim, A. Supporting the spatial allocation of management practices to improve ecosystem services—An opportunity map approach for agricultural landscapes. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 172, 113212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oubdil, S.; Souiri, S.; Ajmani, S.; Nazih, A.; Mentag, R.; Benradi, F.; El Jalil, M.H. Characterization and GIS Mapping of the Physicochemical Quality of Soils in the Irrigated Area of Tafrata (Eastern Morocco): Implications for Sustainable Agricultural Management. Geographies 2025, 5, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).