Abstract

This study aims to examine the antecedents influencing corporate social responsibility (CSR) practices in Malaysian oil and gas companies, addressing the limited empirical research in this sector. Data were collected through a survey of 65 managerial-level representatives, including CEOs and senior management, from Malaysian oil and gas companies. IBM SPSS (Version 28) and SmartPLS (Version 3.3) were used to analyse the data and test the proposed relationships using PLS-SEM. The results reveal that stakeholder pressure has a positive and significant relationship with CSR practices in the oil and gas industry. This indicates that legitimacy-driven motivations play a key role in CSR adoption. Furthermore, CSR practices are found to enhance corporate reputation and competitive advantage. The findings highlight the importance for managers to recognize stakeholder expectations as a major driver of CSR adoption and to leverage CSR initiatives to strengthen organizational reputation and competitiveness. This study contributes to the limited body of knowledge on CSR practices within Malaysia’s oil and gas industry by providing empirical evidence of the factors influencing CSR implementation and its organizational outcomes.

1. Introduction

The oil and gas industry operates under constant scrutiny due to its significant social and environmental impacts, which directly influence a company’s reputation and competitive standing [1,2]. Firms in this sector face mounting pressures from stakeholders and institutional actors to demonstrate accountability, often through Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) initiatives [3,4]. Given its high visibility and exposure to criticism, the oil and gas sector is more vulnerable to reputational risks than many other industries [5]. As a result, CSR has become an integral component of the business agenda rather than a peripheral activity [1]. Recent research confirms that CSR practices in the oil and gas sector not only address societal expectations but also influence corporate performance and competitiveness [6].

In Malaysia, however, CSR practices remain less developed compared to those in Europe and North America [7]. Evidence suggests that Malaysian firms continue to adopt CSR on a project-specific basis, often emphasizing philanthropy, religious initiatives, and community events instead of embedding CSR into long-term strategic operations [7,8]. Although CSR reporting has improved, studies reveal that some initiatives function more as publicity stunts than as genuine commitments to sustainability [9]. Furthermore, environmental disclosures by upstream oil and gas companies remain relatively weak despite governance mechanisms [10]. In other resource-intensive industries such as palm oil, employee engagement has been found to significantly influence sustainability performance [11], yet comparable empirical insights for the oil and gas sector are still lacking. Importantly, limited empirical research has examined how CSR practices contribute to outcomes such as corporate reputation, competitive advantage, and financial performance within the Malaysian oil and gas sector [12,13]. Addressing these gaps is crucial to advancing CSR scholarship and to providing practical insights for firms operating in one of Malaysia’s most critical and scrutinized industries.

This study examines how stakeholder and institutional pressures shape CSR practices and how these practices influence financial performance, corporate reputation, and competitive advantage in Malaysian oil and gas companies. It also assesses the mediating roles of reputation and competitive advantage in these relationships. By addressing these objectives, the study offers theoretical insights and practical guidance for managers and policymakers in the Malaysian oil and gas sector.

In summary, examining both the antecedents and outcomes of CSR provides valuable insights into how these practices are shaped and the benefits they generate. This study goes beyond the traditional perception of CSR as mere philanthropic or community-based activities, positioning it instead as a strategic approach that can enhance legitimacy, strengthen corporate reputation, and improve competitiveness. By addressing the limited empirical evidence on CSR within Malaysia’s oil and gas sector, this research contributes to narrowing the gap between CSR practices in developing and developed economies. Furthermore, given the oil and gas industry’s vital role in Malaysia’s economic growth and national revenue [14], a deeper understanding of CSR implementation in this sector offers both theoretical advancement and practical implications for businesses and policymakers.

2. Literature Review

As more companies invest in CSR initiatives, there is a growing interest in the field [15]. Originating from Bowen’s seminal work in the early 1950s [16], the concept of CSR has expanded beyond social responsibility to encompass ethical and legal obligations, economic responsibilities, and environmental stewardship [17]. Various CSR theories, such as Carroll’s CSR pyramid, stakeholder theory, institutional theory, and the Triple Bottom Line (TBL) theory, are extensively employed in CSR literature to explain the adoption and implementation of CSR [5,18,19].

When examined from a stakeholder perspective, Carroll’s CSR pyramid addresses the unique requirements of various stakeholders within its four components [20]. Its simplicity and comprehensive coverage of CSR aspects make it robust, ensuring the sustainability of these frameworks for forthcoming stakeholder generations [20]. However, a notable drawback is the need to balance different stakeholder needs and the overly descriptive nature of each CSR aspect. Stakeholder theory highlights the diversity of the business environment, where stakeholders with different interests influence company operations and legitimacy [21]. As a result, management decisions are influenced by the demands of these diverse stakeholders, with the theory’s practical applicability being its advantage.

Institutional theory focuses on how firms adapt to the institutions within their industry or country, offering strength in navigating uncertain business environments [22]. However, companies may encounter constraints imposed by the institutional environment in which they operate. The Triple Bottom Line (TBL) theory, similar to stakeholder theory, underscores the interconnectedness of the economy, society, and environment, yet it has the potential drawback of possibly favoring corporate interests [23,24]. Rasche et al. [25] argue that institutional theory grants legitimacy to the organization, while legitimacy theory legitimizes its relationship with stakeholders. Saenz [5] supports this by confirming that companies in controversial sectors adopt CSR practices to engage stakeholders for organizational legitimacy.

As a result, stakeholder theory and institutional theory are intricately connected with legitimacy theory, forming a unified theoretical framework that underpins this study.

3. Hypotheses Development

3.1. Stakeholder Pressure and CSR

Companies often respond to stakeholder pressure because it is closely linked to their success, social acceptance, and competitive positioning [26]. Additionally, recent empirical evidence from Malaysian SMEs confirms that external stakeholder pressure, from customers, regulators, and community groups, significantly influences firms’ intentions to adopt environmental and CSR practices, especially when moderated by firm characteristics [27]. A more recent study by [28] finds that stakeholder pressure plays a crucial role in the adoption of sustainable supply chain practices in manufacturing firms, indicating that firms under higher stakeholder scrutiny are more likely to implement CSR-oriented policies. Building on this foundation, this study also aligns with earlier observations by [29], which suggested that oil and gas companies utilize CSR to manage both stakeholder and non-stakeholder relationships. Accordingly, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1.

The relationship between stakeholder pressure and CSR is positively related.

3.2. Institutional Isomorphism Pressure and CSR

Joo et al. [30] have highlighted the significance of institutional isomorphism pressures as a crucial factor influencing CSR adoption. These pressures consist of coercive, mimetic, and normative forces acting as antecedents to CSR practices [31]. Coercive isomorphic pressure primarily pertains to CSR initiatives driven by regulatory requirements and competitive market conditions [32]. Recent empirical evidence also reinforces this relationship; for instance, Ding and Wang [33] found that coercive and mimetic institutional pressures significantly enhance ESG responsibility fulfillment among Chinese listed firms, demonstrating how regulatory and competitive forces stimulate responsible organizational practices. This leads to the formulation of the following hypothesis.

H2a.

The relationship between institutional coercive isomorphism pressure and CSR is positively related.

The mimetic isomorphic pressure within the environment or industry in which a business operates influences the business to emulate established standards and practices. According to [34], adopting best practices from industry leaders, such as CSR, is considered a sound business strategy. This elucidates why businesses opt for certification as a means to access new markets and adopt industry practices [35]. Empirical evidence from developing economies supports this behavior; for example, Wiredu et al. [36] found that firms’ sustainability reporting and green accounting practices are significantly shaped by mimetic pressures, highlighting how peer influence drives the adoption of socially responsible practices. Hence, the following hypothesis is proposed.

H2b.

The relationship between institutional mimetic isomorphism pressure and CSR is positively related.

Institutional normative isomorphic pressure emanates from professional standards explicitly formalized by professional associations and educational institutions as norms of behavior and practice, or societal expectations [37]. Particularly within the energy sector, and notably in the oil and gas industry, companies collaborate with numerous social organizations and government agencies to comply with the standards and expectations inherent in their business operations [38,39]. Empirical evidence from Lebanon confirms that such normative pressures significantly drive both explicit and implicit CSR practices: local and international societal norms and institutional expectations encourage firms to adopt socially responsible initiatives [40]. Consequently, the following hypothesis is posited.

H2c.

The relationship between institutional normative isomorphism pressure and CSR is positively related.

3.3. Consequences of CSR on Firm Financial Performance

In industries where firms face substantial reputational risks, such as in the chemical and oil & gas sectors, CSR becomes an essential component of a company’s overarching strategy [39]. Empirical research has long shown that socially responsible companies exert a significant influence on firm financial performance [41]. More recent evidence reinforces this relationship, as Ref. [42] found that firms recognized as strong corporate citizens outperform their peers in terms of operating performance. Meanwhile, Li et al. [43] confirmed through a cross-country meta-analysis that CSR positively impacts corporate financial performance across diverse contexts. Similarly, Ref. [44] demonstrated that CSR enhances firm performance both directly and indirectly, with innovation and reputation serving as key mediating mechanisms. Taken together, these findings underscore the financial relevance of CSR, particularly in high-risk industries. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed.

H3.

CSR is positively related to firm financial performance.

3.4. Corporate Reputation and Competitive Advantage on CSR

Recent studies have found varying results regarding the correlation between CSR and firm financial performance [45]. Some researchers have contended that the connection with corporate reputation serves as a crucial mediator between CSR and firm financial performance [46]. More recent evidence supports this perspective. For instance, Ennenbach and Barkela [47] demonstrated that CSR-related media coverage significantly influences corporate reputation, with the effect fully mediated by CSR skepticism, underscoring the reputational risks and opportunities of CSR communication. Similarly, Riahi et al. [48] emphasized that sustained CSR commitment plays a pivotal role in building long-term corporate reputation through stakeholder trust and communication. In the Malaysian context, Ismail and Mohamed [49] found that economic and philanthropic CSR dimensions directly enhance organizational reputation, which in turn mediates the effect of CSR on consumers’ purchase intentions. Collectively, these studies strengthen the argument that CSR enhances corporate reputation, which subsequently contributes to improved firm outcomes.

H4.

CSR is positively related to corporate reputation.

H5.

The relationship between CSR and firm financial performance is positively mediated by corporate reputation.

CSR has also been utilized as a distinguishing factor in positioning a company as socially responsible amidst competitive pressures [50]. Additionally, research suggests that competitive advantage serves as a significant mediator for CSR outcomes and firm financial performance [51]. Empirical work further supports this view. Bhatti et al. [52] demonstrated that enhanced knowledge-worker performance, driven by career satisfaction and organizational support, can strengthen a firm’s productivity and, in turn, contribute to sustained competitive advantage. Similarly, Ghimire et al. [53] highlighted how the strategic adoption of cloud computing enables SMEs to achieve cost-effectiveness and operational efficiency, both of which are central to building and maintaining competitive advantage. These insights reinforce the argument that CSR and related strategic initiatives can translate into firm competitiveness through multiple pathways.

H6.

The relationship between CSR and firm financial performance is sequentially mediated positively by company’s corporate reputation and corporate competitive advantage.

H7.

CSR is positively related to corporate competitive advantage.

H8.

The relationship between CSR and firm financial performance is positively mediated by company’s corporate competitive advantage.

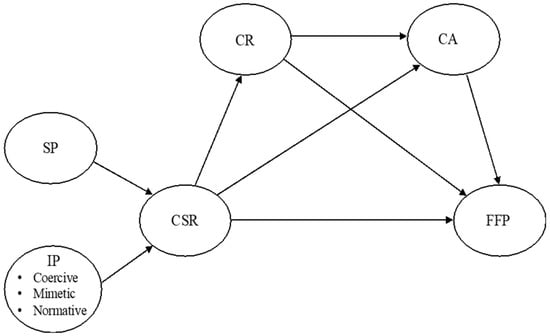

The theoretical framework from the above discussion is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Theoretical Framework. Note: SP = Stakeholder Pressure; IP = Institutional Isomorphism Pressure; CSR = Corporate Social Responsibility; CR = Corporate Reputation; CA = Corporate Competitive Advantage; FFP = Firm Financial Performance.

4. Methodology

4.1. Sampling Design and Data Collection Method

The researcher utilized a simple random sampling method to attain a more favorable sampling rate. The study’s sample population comprises oil and gas companies operating in Malaysia, with each Malaysian oil & gas service provider’s company serving as the unit of analysis. The selection process involved companies listed under the Malaysian Oil & Gas Service Council (MOGSC), a non-governmental and non-profit organization representing active oil and gas companies in Malaysia. These companies are licensed to operate in the Malaysian oil & gas industry and actively participate in Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) activities.

To gather data, emails were sent to the selected companies, with only one respondent, either the CEO or a senior management representative, completing the questionnaire on behalf of the organization. These individuals were selected based on their comprehensive understanding of their company’s operational activities. This method aligns with previous studies on business organizations [54] and facilitates data collection from respondents who possess the most pertinent information. The chosen approach not only ensures convenience, efficiency, and feasibility for the researcher [55] but also conforms to the standards outlined by [56,57].

A total of 180 questionnaires were distributed, of which 44% (79 questionnaires) were returned. After screening for completeness and validity, 65 usable responses were retained for analysis, representing a usable response rate of 36.1%. This sample size is justified based on the total population of oil and gas companies in Malaysia, and it meets the minimum requirements for PLS-SEM according to [56,58], ensuring sufficient statistical power for hypothesis testing. PLS-SEM was selected over CB-SEM due to its suitability for complex models, small-to-moderate sample sizes, and the exploratory nature of this research [56]. Returned questionnaires were screened for completeness and consistency, and anonymity was ensured to encourage honest responses.

4.2. Measurement Instruments

The measurement instruments were chosen due to their high validity and reliability, as established by [59]. The composite reliability for these instruments exceeded 0.80.

Stakeholder Pressure: The measurement scale items, comprising four items, were adapted from [60] study to assess participating firms’ perception of stakeholder pressure.

Institutional Isomorphism Pressure: Institutional isomorphism pressure encompasses coercive, mimetic, and normative forces [61]. The measurement scale developed by [62] was adopted, as it has been effectively utilized and comprehended by respondents, considering the context of the Malaysian environment.

Corporate Social Responsibility: The CSR constructs were measured using the scale developed by [63].

Corporate Reputation: The researcher adopted the measurement developed by [64], with one item being excluded based on expert review. This exclusion was made to prevent cross-loading between the CSR measurement and the corporate reputation scale.

Corporate Competitive Advantage: The researcher adopted three measurement items from [32], reflecting the rationale for CSR adoption based on stakeholder pressure and institutional isomorphic pressure.

Firm Financial Performance: Due to the unavailability and difficulty in accessing firm financial data, the researcher adopted subjective measures to assess firm financial performance [65]. Measurement items from the [66] study were utilized to construct the firm financial performance measurement.

The researcher employed a five-point Likert scale for the measurement scale, comprising five categories: (1) Strongly disagree, (2) Disagree, (3) Neither agree nor disagree, (4) Agree, and (5) Strongly agree, to assess the constructs for stakeholder pressure, institutional isomorphism pressure, CSR, corporate reputation, and corporate competitive advantage variables. For the firm financial performance construct, a five-point Likert scale was used with the following categories: (1) More than 10% decline, (2) Less than 10% decline, (3) No change, (4) Less than 10% increase, and (5) More than 10% increase [66].

A pilot study was conducted before the actual study to assess the measurement instruments for readability, coherence, clarity, and consistency. Feedback received from the pilot study was incorporated, including additional information on company profiles. Additionally, the results of the scale reliability test indicated no issues with the measurement instruments selected for use in the actual survey.

4.3. Data Analysis

Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) has been adopted due to its widespread acceptance in various business disciplines, its ability to handle small sample sizes, and its capability to manage non-normal data effectively [56]. This technique has been successfully applied in recent studies related to CSR research [62]. PLS-SEM analysis involves a two-step approach: measurement modeling and structural modeling.

5. Results

The results of the data examination indicate that there are no issues with the data, such as missing values, suspicious response patterns, normality, or bias. Table 1 provides a summary of the respondent profiles.

Table 1.

Respondent Profile.

5.1. Reliability and Validity

Table 2 presents a summary of the evaluation results of the reflective measurement models. Based on the observed results, all evaluation criteria of the measurement models have been met, confirming the quality of the measures’ reliability and validity [56], the constructs can be included in the path model.

Table 2.

Results Summary for Reflective Measurement Models.

5.2. Structural Model Assessment

Following the establishment of a reliable and valid measurement model, the structural model underwent evaluation. This process involved testing for collinearity, assessing the significance of path coefficients, evaluating coefficients of determination (R2), examining predictive relevance (Q2), and exploring the effect size of constructs on endogenous variables (f2). Results from the collinearity test, indicated by variance inflation factor (VIF) values, demonstrated that they all remained below the threshold of 5, indicating that collinearity among predictor constructs did not pose an issue.

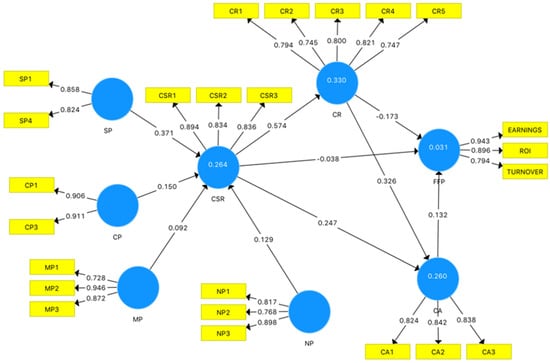

Figure 2 shows the results of structural model analysis by PLS-SEM.

Figure 2.

PLS-SEM Results. Note: SP = Stakeholder Pressure; CP = Coercive Isomorphism Pressure; MP = Mimetic Isomorphism Pressure; NP = Normative Isomorphism Pressure; CSR = Corporate Social Responsibility; CR = Corporate Reputation; CA = Corporate Competitive Advantage; FFP = Firm Financial Performance.

Table 3 provides a summary of the results from significance tests conducted for the path coefficients within the structural model. The significance testing indicates that the relationships between SP → CSR (p = 0.002), CSR → CR (p = 0.000), CSR → CA (p = 0.023), and CR → CA (p = 0.009) are all statistically significant. However, the relationships between CP → CSR (p = 0.238), MP → CSR (p = 0.540), NP → CSR (p = 0.358), and CSR → FFP (p = 0.842) are not statistically significant.

Table 3.

Structural model path coefficient significance test results.

Table 4 presents the results of the R2 and Q2 values for the endogenous variables CSR, CR, CA, and FFP. The R2 values for the endogenous latent variables CSR (0.264), CR (0.260), CA (0.330), and FFP (0.031) can be considered weak, following the suggestion of [56]. The CSR, CR, and CA Q2 values are greater than zero, confirming the predictive relevance of the model. However, the Q2 value for FFP is negative, indicating that the exogenous constructs CSR, CR, and CA had no predictive relevance for FFP as an endogenous construct. Effect sizes (f2) are shown in Table 5.

Table 4.

R2 and Q2 Values.

Table 5.

f2 Effect Size.

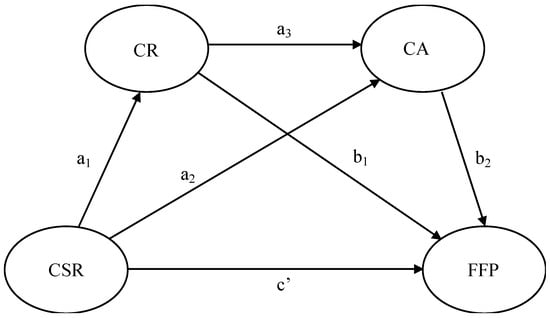

5.3. Mediation Analysis

The structural model subsection includes three mediation hypotheses, with one proposing a three-path mediation effect. Figure 3 illustrates the multiple mediations of the structural model. The analysis was conducted using the procedure outlined by [67]. This procedure involves two steps. The first step assesses the significance and magnitude of the indirect effect, while the second step identifies the type of effect or mediator [67]. Table 6 provides a summary of the results of the significance analysis of the mediation test.

Figure 3.

Three-path Mediating Model. Note. .

Table 6.

Significance Analysis of the Mediating Construct’s CR and CA.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

Hypothesis 1 (H1) posits that the relationship between stakeholder pressure (SP) and CSR is positive. PLS-SEM results confirm a positive relationship between stakeholder pressure and CSR (t = 3.070; p = 0.002), thus H1 is accepted. Additionally, SP demonstrates high relevance in its significant relationship, as evidenced by its path coefficient from SP to CSR being 0.371 compared to the exogenous (predictor) constructs CP, MP, and NP to CSR. These findings align with earlier and recent studies on how firms respond to stakeholder pressure [68]. This positive effect suggests that firms adopt CSR in response to stakeholder expectations and legitimacy pressures. Managers can leverage this by proactively engaging stakeholders and integrating their feedback into CSR strategies.

Hypothesis 2a (H2a) proposed a positive relationship between institutional coercive isomorphism pressure (CP) and CSR. However, PLS-SEM results indicate no support for this association (t = 1.180; p = 0.238), leading to the rejection of H2a. Thus, the direct relationship between CP and CSR is not significant. Similarly, Hypothesis 2b (H2b) suggested a positive relationship between institutional mimetic isomorphism pressure (MP) and CSR, which was also rejected as PLS-SEM results did not support this relationship (t = 0.613; p = 0.540). Consequently, the direct link between MP and CSR is not significant. Furthermore, Hypothesis 2c (H2c) proposed a positive relationship between institutional normative isomorphism pressure (NP) and CSR, but PLS-SEM results did not support this relationship (t = 0.920; p = 0.358). Hence, the direct relationship between NP and CSR is not significant. In conclusion, the findings suggest that the relationship between institutional isomorphism pressure (coercive, mimetic, and normative) and CSR practices in oil and gas companies is negative. These results provide insights into Malaysian oil and gas companies, indicating that institutional isomorphic pressures do not serve as antecedents in promoting CSR adoption [69]. A possible explanation is that regulatory enforcement and industry norms in this sector are relatively weak, and companies may prioritize voluntary CSR initiatives over compliance-driven pressures. Managers should therefore focus on proactive CSR programs aligned with stakeholder expectations rather than relying solely on institutional mandates.

Hypothesis H3 posited a positive relationship between CSR and a company’s financial performance (FFP). However, PLS-SEM results do not support this assumption (t = 0.199; p = 0.842), leading to the rejection of H3. Additionally, the negative predictive relevance Q2 further underscores the lack of predictive association between the CSR construct as an endogenous variable and FFP. Similar findings were observed in [70] study. Karyawati et al. [71] acknowledged that this discrepancy may stem from various factors such as legitimacy motives, economic development considerations, and the partial efficacy of CSR in addressing social problems. This suggests that CSR may not directly improve financial performance immediately, but its benefits can be realized indirectly through reputation or competitive advantage. Firms should adopt CSR strategically, focusing on long-term value creation rather than expecting immediate financial gains.

Hypothesis H4 proposed a positive relationship between CSR and corporate reputation (CR). The PLS-SEM results validate this relationship, showing a positive and significant association between CSR and CR (t = 2.274; p = 0.023), thus confirming the acceptance of Hypothesis H4. The effect size (f2) of 0.49 indicates a large effect, highlighting the relative importance of CSR in shaping a company’s CR. This finding is consistent with existing studies that have identified a positive correlation between CSR and CR, particularly in construction companies [72].

Hypothesis H5 posited that the relationship between CSR and a company’s financial performance is positively mediated by corporate reputation (CR), thus testing the mediation effect of CR between CSR and FFP. However, the PLS-SEM results indicate that there is no significant indirect effect on CR (t = 0.768; p = 0.442). Consequently, Hypothesis H5 is rejected, as the mediation effect of CR between CSR and FFP is not supported. This finding aligns with previous research conducted by [71], which also did not find support for the mediation effect of corporate reputation between CSR and financial performance.

Hypothesis H6 proposed that the relationship between CSR and a company’s financial performance is sequentially mediated by corporate reputation (CR) and competitive advantage (CA). However, the PLS-SEM results indicate that the indirect effect of sequential mediation through CR and CA was not significant (t = 0.518; p = 0.605). Therefore, Hypothesis H6 is rejected, as there is no support for sequential mediation through CR and CA between CSR and FFP. This finding is in line with the results reported by [71], which also did not find support for sequential mediation through CR and CA between CSR and financial performance.

Hypothesis H7 proposed that CSR is positively associated with a company’s competitive advantage (CA). The PLS-SEM results confirm a positive and significant association between CSR and CA (t = 4.866; p = 0.000), thereby supporting the acceptance of Hypothesis H7. This finding is consistent with existing studies that have identified a positive correlation between CSR and a company’s achievement of competitive advantage [68]. These results indicate that CSR initiatives not only improve organizational outcomes but also provide actionable avenues for managers to enhance corporate reputation and competitive advantage through targeted CSR programs.

Hypothesis H8 proposed that the relationship between CSR and a company’s financial performance is actively mediated by the company’s competitive advantage (CA). However, the PLS-SEM results indicate no significant indirect effect (t = 0.612; p = 0.541). This suggests that Hypothesis H8 is rejected due to the absence of mediation. This finding aligns with the results reported by [71], which also did not find support for mediation through competitive advantage between CSR and financial performance.

The study further explored the influence of corporate reputation (CR) as a mediator between CSR and competitive advantage (CA). PLS-SEM results indicate a significant indirect effect (t = 2.040; p = 0.041), suggesting the presence of mediation. Specifically, the analysis suggests a type of partial mediation, with the variance accounted for (VAF) reaching 43% [67]. These findings are consistent with earlier research indicating that firms adopting CSR exhibit positive correlations with both corporate reputation and competitive advantage, as well as a positive correlation with the mediating role of CR between CSR and CA [68]. The overall results of the hypotheses testing are summarised in Table 7.

Table 7.

Summary of Overall Hypotheses Testing Results.

7. Managerial Implications

This study demonstrates a highly positive direct relationship between stakeholder pressure and the adoption of CSR practices among Malaysian oil and gas companies. This finding aligns with previous research indicating a positive association between CSR and stakeholder pressure [18]. Furthermore, the study reveals that oil and gas companies utilize CSR as a means to manage their stakeholders and enhance legitimacy. As a result, management should prioritize understanding the influence of stakeholder pressure on corporate CSR practices and integrate it into their business strategy to attain corporate legitimacy [41].

Additionally, the study highlights a significantly positive direct relationship between CSR initiatives and corporate reputation. This suggests that CSR can serve as a compelling impetus for management to establish a reputable business framework conducive to sustainability [73]. Recent research corroborates these findings, indicating that CSR is strategically employed as a tool to mitigate reputational risks [74]. Moreover, King and McDonnell [75] uncovered that companies perceive CSR as instrumental in enhancing corporate reputation, thereby garnering approval from stakeholders and safeguarding their reputation over time.

Furthermore, this study reveals a positive correlation between CSR’s corporate reputation and corporate competitive advantage. This prompts firm management to consider social initiatives as integral components of their business strategy alongside traditional strategic options to gain a competitive edge. Strategies focused on enhancing CSR investments significantly expand to encompass various stakeholders who prioritize a company’s demonstrated social responsibility [76]. Kuncoro and Suriani [77] research supports this notion, suggesting that firms adopting strategies that offer social products can add value to their corporate competitive advantage. Moreover, literature reviews and studies indicate that CSR strategies can serve as distinctive and differentiating intangible assets for attaining competitive advantage [78]. Despite the tension created by CSR implementation due to its competing decision-making characteristics, firms that embrace CSR are perceived positively, attracting additional stakeholders and investors [79].

In conclusion, this study did not identify a statistically significant causal relationship between CSR activities and the financial performance of Malaysian oil and gas companies. This finding aligns with previous research that initially explored the relationship between CSR and corporate financial performance [71].

8. Limitations of the Study

This study is constrained to examining CSR practices within Malaysian oil and gas companies and primarily focuses on two key antecedents: stakeholder pressures and institutional isomorphism, which are significant influences on CSR adoption. The study relies solely on managerial-level responses, which may introduce bias and limit the generalizability of the findings. Additionally, factors such as the business case for CSR and firm value were not addressed, and the cross-sectional design restricts the ability to draw causal inferences.

9. Future Research

This study marks the inaugural exploration of CSR activities and their implementation within Malaysian oil and gas companies. Significant knowledge and research gaps persist in this domain. The findings indicate a robust influence of stakeholder pressure on the adoption of CSR practices by Malaysian oil companies, affirming theories related to legitimacy. However, the study reveals that institutional isomorphic pressure does not exert a significant influence as an antecedent on CSR adoption practices. This suggests potential differences in CSR adoption among oil and gas companies in Malaysia. The researchers advocate for further investigation in this area for future research endeavors.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.K.P., M.F.I. and R.S.; Methodology, S.K.P., M.F.I., S.Q. and A.R.b.S.S.; Software, A.R.b.S.S. and R.S.; Validation, M.F.I., S.Q., A.R.b.S.S. and R.S.; Formal analysis, S.K.P. and N.A.Z.; Investigation, S.K.P., M.F.I. and R.H.; Resources, M.F.I., N.A.Z., S.Q., R.S. and R.H.; Data curation, S.K.P. and N.A.Z.; Writing—original draft, S.K.P. and M.F.I.; Writing—review & editing, N.A.Z., S.Q., A.R.b.S.S., R.S. and R.H.; Visualization, N.A.Z. and A.R.b.S.S.; Supervision, A.R.b.S.S. and R.H.; Project administration, N.A.Z. and R.S.; Funding acquisition, S.Q. and R.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of INTI International University (protocol code INTI/REC/2024/0625 and date 17 April 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Browne, J. Beyond Business: An Inspirational Memoir from a Remarkable Leader; Orion Books Ltd.: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson, K. Oil and Gas Companies and the Management of Social and Environmental Impacts and Issues: The Evolution of the Industry’s Approach; WIDER Working Paper 2017/22; UNU-WIDER: Helsinki, Finland, 2017; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdiaw-Kwasie, M.O. Does pressure-induced partnership really matter? Empirical modelling of stakeholder pressure and firms’ CSR attitude. Soc. Responsib. J. 2018, 14, 685–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beddewela, E.; Fairbrass, J. Seeking legitimacy through CSR: Institutional pressures and corporate responses of multinationals in Sri Lanka. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 136, 503–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saenz, C. The context in mining projects influences the corporate social responsibility strategy to earn a social license to operate: A case study in Peru. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 554–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aseh, K.; Kenny, K. Corporate Social Responsibility and Business Performance: Evidence from Malaysia Oil and Gas Companies. Arch. Bus. Res. 2020, 8, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamun, M.A.; Shaikh, J.M.; Easmin, R. Corporate social responsibility disclosure in Malaysian business. Acad. Strateg. Manag. J. 2017, 16, 29–47. [Google Scholar]

- Zainoddin, A.I.; Amran, A.; Shaharudin, M.R. The effect of social capital on the effectiveness of community development programmes in Malaysia. Int. J. Inf. Decis. Sci. 2020, 12, 227–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baharudin, D.M.; Nik Azman, N.H. Corporate social responsibility reporting within the Malaysian oil and gas industry: A questionable publicity stunt. Econ. Manag. Sustain. 2019, 4, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghani, S.A.; Rosdi, D. The relationship between environmental performance and corporate governance towards environmental disclosure of oil and gas companies operating in Malaysia upstream projects. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2019, 9, 460–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.S.C.; Piaralal, S.K.; Zulkefli, N.A.; Raghavan, S. Driving sustainability performance in Malaysia’s palm oil industry: How employee engagement makes the difference. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2025, 15, 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, Z.; Abdul Aziz, Y. Institutionalizing corporate social responsibility: Effects on corporate reputation, culture, and legitimacy in Malaysia. Soc. Responsib. J. 2013, 9, 334–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, H.B.; Ning, Y.; Piew, L.K. From corporate social responsibility to customer satisfaction: A study of repurchase intention in Malaysian petroleum industry. J. Infrastruct. Policy Dev. 2025, 9, 10443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DOSM. Annual Economic Statistics 2018: Mining of Petroleum and Natural Gas; Department of Statistics Malaysia: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2019. Available online: http://www.statistics.gov.my/site/downloadrelease?id=annual-economic-statistics-2018-mining-of-petroleum-and-natural-gas&lang=English&admin_view= (accessed on 14 April 2020).

- Zahidy, A.A.; Sorooshian, S.; Abd Hamid, Z. Critical success factors for corporate social responsibility adoption in the construction industry in Malaysia. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, H.R. Social Responsibilities of the Businessman; University of Iowa Press: Iowa City, IA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, E.; Reed, L. Stockholders and Stakeholders: A New Perspective on Corporate Governance. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1983, 15, 88–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, W.; Frynas, J.G.; Mahmood, Z. Determinants of corporate social responsibility (CSR) disclosure in developed and developing countries: A literature review. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2017, 24, 273–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, A.H.; Abdullah, N.; Sulaiman, M. Environmental disclosure quality: Examining the impact of the stock exchange of Malaysia’s listing requirements. Soc. Responsib. J. 2015, 11, 904–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. Carroll’s pyramid of CSR: Taking another look. Int. J. Corp. Soc. Responsib. 2016, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E.; Harrison, J.S.; Wicks, A.C.; Parmar, B.L.; De Colle, S. Stakeholder Theory: The State of the Art; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Clegg, S.R.; Kornberger, M.; Pitsis, T. Managing and Organizations: An Introduction to Theory and Practice, 4th ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Benn, S.; Bolton, D. Key Concepts in Corporate Social Responsibility; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Moon, J. Corporate Social Responsibility: A Very Short Introduction; University Oxford Press: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Rasche, A.; Morsing, M.; Moon, J. Corporate Social Responsibility; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Boutilier, R.G.; Thomson, I. Modelling and Measuring the Social License to Operate: Fruits of a Dialogue Between Theory and Practice; Social Licence: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2011; pp. 1–10. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/391982329_Modelling_and_Measuring_the_SLO_1_MODELLING_AND_MEASURING_THE_SOCIAL_LICENSE_TO_OPERATE_FRUITS_OF_A_DIALOGUE_BETWEEN_THEORY_AND_PRACTICE (accessed on 14 April 2020).

- Latip, M.; Sharkawi, I.; Mohamed, Z.; Kasron, N. The impact of external stakeholders’ pressures on the intention to adopt environmental management practices and the moderating effects of firm size. J. Small Bus. Strategy 2022, 32, 45–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azam, T.; Wang, S.; Mohsin, M.; Nazam, M.; Hashim, M.; Baig, S.A.; Zia-ur-Rehman, M. Does stakeholder pressure matter in adopting sustainable supply chain initiatives? Insights from agro-based processing industry. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbelwa, L. Investigation of stakeholder management in the oil and gas industry in Tanzania. Bus. Manag. Rev. 2018, 21, 34–59. [Google Scholar]

- Joo, S.; Larkin, B.; Walker, N. Institutional isomorphism and social responsibility in professional sports. Sport Bus. Manag. Int. J. 2017, 7, 38–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, V.S.; Jha, A. Pressures of CSR in India: An institutional perspective. J. Strategy Manag. 2019, 12, 227–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jean, R.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, X.; Sinkovics, R. Drivers and customer satisfaction outcomes of CSR in supply chains in different institutional contexts: A comparison between China and Taiwan. Int. Mark. Rev. 2016, 33, 514–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Wang, Z. The influence of institutional pressures on Environmental, Social, and Governance responsibility fulfillment: Insights from Chinese listed firms. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.H.; Amaeshi, K.; Harris, S.; Suh, C.J. CSR and the national institutional context: The case of South Korea. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 2581–2591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liston-Heyes, C.; Heyes, A. Is there evidence for export-led adoption of ISO 14001? A review of the literature using meta-regression. Bus. Soc. 2019, 60, 764–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiredu, I.; Agyemang, A.O.; Agbadzidah, S.Y. Does green accounting influence ecological sustainability? Evidence from a developing economy. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2023, 10, 2240559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, M.; Beddewela, E. Does context matter for sustainability disclosure? Institutional factors in Southeast Asia. Bus. Ethics Eur. Rev. 2020, 29, 282–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Vieira, E.T. Striving for legitimacy through corporate social responsibility: Insights from oil companies. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 110, 413–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, D.B. Corporate social responsibility in the oil and gas industry: The importance of reputational risk. Chi.-Kent L. Rev. 2011, 86, 59. [Google Scholar]

- Kobrossy, S.; Karaszewski, R.; AlChami, R. The institutionalization of implicit and explicit CSR in a developing country context: The case of Lebanon. Adm. Sci. 2022, 12, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Shen, H.; Zhou, K.Z.; Li, J.J. How does environmental corporate social responsibility matter in a dysfunctional institutional environment? Evidence from China. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 140, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Li, Y.; Oyewale, K.; Tworoger, E. Corporate social responsibility and firm financial performance: Evidence from America’s Best Corporate Citizens. Int. J. Financ. Stud. 2025, 13, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Yan, T.; Li, Y. Corporate social responsibility and financial performance in a cross-country context: A meta-analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2025, 190, 115218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Lan, R.; Liu, Y.; Cao, Y.; Cheng, Y. Meta-analysis on relationship between corporate social responsibility and firm performance: Mediating mechanisms of innovation and reputation. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul Wahab, N.B.; Ahmad, N.B.; Yusoff, H.B. CSR inflections: An overview of CSR practices on financial performance by public listed companies in Malaysia. SHS Web Conf. 2017, 36, 00003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sindhu, M.I.; Arif, M. The inter linkage of corporate reputation between corporate social responsibility and financial performance. Pak. J. Commer. Soc. Sci. 2017, 11, 898–910. [Google Scholar]

- Ennenbach, S.; Barkela, B. Effects of CSR-related media coverage on corporate reputation. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riahi, R.; Chibani, F.; Omri, A. How important is CSR commitment in shaping corporate reputation? Int. J. Prof. Bus. Rev. 2024, 9, e04672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, Z.; Mohamed, W.N.W. Accelerating brand value: The role of CSR in shaping automotive brand reputation and consumer preferences. J. Manag. Mark. Rev. 2024, 9, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupire, M.; M’Zali, B. CSR strategies in response to competitive pressures. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 148, 603–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arend, R.J. Social and environmental performance at SMEs: Considering motivations, capabilities, and instrumentalism. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 125, 541–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatti, M.A.; Juhari, A.S.; Piaralal, S.K.; Piaralal, N.K. Knowledge workers’ job performance: An examination of career values, perceived organizational support and career satisfaction. Bus. Manag. Horiz. 2017, 5, 13–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghimire, P.; Piaralal, S.K.; Raghavan, S.; Rethina, V.S. Exploring sustainability in cloud computing adoption among SMEs in Nepal: A conceptual model. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2024, 14, 1143–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajasom, A.; Hung, D.K.M.; Nikbin, D.; Hyun, S.S. The role of transformational leadership in innovation performance of Malaysian SMEs. Asian J. Technol. Innov. 2015, 23, 172–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, R.W. Convenience sampling, random sampling, and snowball sampling: How does sampling affect the validity of research? J. Vis. Impair. Blind. 2015, 109, 164–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM), 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sekaran, U.; Bougie, R. Research Methods for Business: A Skill Building Approach; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. A power primer. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 112, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lisi, I.E. Determinants and performance effects of social performance measurement systems. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 152, 225–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, P.J.; Powell, W.W. The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1983, 48, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul Aziz, N.A.; Senik, R.; Yau, F.S.; San, O.T.; Attan, H. Influence of institutional pressures on the adoption of green initiatives. Int. J. Econ. Manag. 2017, 11, 939–967. [Google Scholar]

- Hur, W.-M.; Kim, H.; Woo, J. How CSR leads to corporate brand equity: Mediating mechanisms of corporate brand credibility and reputation. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 125, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghian, M.; D’Souza, C.; Polonsky, M. A stakeholder approach to corporate social responsibility, reputation and business performance. Soc. Responsib. J. 2015, 11, 340–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Darwish, T.K.; Potočnik, K. Measuring organizational performance: A case for subjective measures. Br. J. Manag. 2016, 27, 214–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyder, M.; Theuvsen, L. Determinants and effects of corporate social responsibility in German agribusiness: A PLS model. Agribusiness 2012, 28, 400–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitzl, C.; Roldan, J.L.; Cepeda, G. Mediation analysis in partial least squares path modeling. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2016, 116, 1849–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waheed, A.; Zhang, Q. Effect of CSR and ethical practices on sustainable competitive performance: A case of emerging markets from stakeholder theory perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 175, 837–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, D.H.B.; Tran, V.T.; Tee, C.M.; Nguyen, D.T. Oil price uncertainty, CSR and institutional quality: A cross-country evidence. Energy Econ. 2021, 100, 105339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, M.L.; Henriques, I.; Husted, B.W. Beyond good intentions: Designing CSR initiatives for greater social impact. J. Manag. 2020, 46, 937–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karyawati, G.; Subroto, B.; Sutrisno, T.; Saraswati, E. The complexity of relationship between corporate social responsibility (CSR) and financial performance. Emerg. Mark. J. 2018, 8, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, S.R.; Eden, L.; Li, D. CSR reputation and firm performance: A dynamic approach. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 163, 619–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaltegger, S.; Burritt, R. Business cases and corporate engagement with sustainability: Differentiating ethical motivations. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 147, 241–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karwowski, M.; Raulinajtys-Grzybek, M. The application of corporate social responsibility (CSR) actions for mitigation of environmental, social, corporate governance (ESG) and reputational risk in integrated reports. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2021, 28, 1270–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, B.; McDonnell, M.H. Good firms, good targets: The relationship between corporate social responsibility, reputation, and activist targeting. In Corporate Social Responsibility in a Globalizing World: Toward Effective Global CSR Frameworks; Tsutsui, K., Lim, A., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Fragouli, E.; Joseph, E. Reputation risks: What enhances the effectiveness of reputation risk management in oil & gas companies? J. Econ. Bus. 2016, 19, 33–55. [Google Scholar]

- Kuncoro, W.; Suriani, W.O. Achieving sustainable competitive advantage through product innovation and market driving. Asia Pac. Manag. Rev. 2018, 23, 186–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.C.; Jalaludin, D.; Phua, L.K. Mandatory sustainability reporting in Malaysia: Impact and internal factors. In Business Sustainability and Innovation, Proceedings of ICBSI 2018; European Proceedings of Social & Behavioural Sciences; EpSBS: London, UK, 2019; Volume 65, pp. 469–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siltaloppi, J.; Rajala, R.; Hietala, H. Integrating CSR with business strategy: A tension management perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 174, 507–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).