Abstract

This study explores the intricate relationship between trade openness, energy intensity, technological innovation, and carbon emissions across emerging and advanced economies, emphasizing their implications for sustainable development. Using balanced panel data, the analysis employs the Method of Moments Quantile Regression (MMQR) and Dumitrescu–Hurlin panel causality approaches to capture heterogeneous effects across varying emission levels. The results reveal that trade openness plays a pivotal role in mitigating carbon emissions by facilitating access to cleaner technologies and promoting energy-efficient production processes. Conversely, energy intensity demonstrates a positive and significant association with carbon emissions, confirming the persistence of fossil fuel dependence in energy structures. Technological innovation exhibits asymmetric effects—reducing emissions in emerging economies while marginally increasing them in advanced economies due to rebound effects associated with industrial expansion. The causality analysis highlights bidirectional linkages among trade openness, energy intensity, and emissions, suggesting that economic and environmental dynamics are mutually reinforcing. These findings imply that both emerging and advanced economies must design integrated policies that align trade liberalization with energy transition strategies and innovation-driven decarbonization. The study contributes novel insights into the energy–carbon nexus by distinguishing the heterogeneous impacts of trade and innovation across different development stages, thereby offering actionable recommendations for achieving global low-carbon growth.

1. Introduction

Over the last few decades, trade openness has been a powerful engine of globalization, economic growth, and technological diffusion, yet its environmental implications remain contentious. Expanding trade enables countries to specialize and benefit from comparative advantage, but it also increases energy demand and accelerates carbon emissions when production is based on fossil fuel-intensive sectors. This tension between economic liberalization and environmental protection defines one of the major challenges for sustainable development in the twenty-first century. As nations have pursued the dual goals of growth and decarbonization under the Paris Agreement and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs 7 and 13), understanding the interplay among trade openness, energy intensity, technological innovation, and carbon emissions has become essential for formulating coherent policy frameworks.

The relationship between trade and the environment has long been theorized through the scale, composition, and technique effects [1]. The scale effect suggests that trade-induced economic expansion increases output and thus emissions. The composition effect reflects structural change: if openness shifts resources toward cleaner industries, emissions may fall; if there is a shift toward energy-intensive production, they may rise. The technique effect captures efficiency gains from technology transfer and stricter environmental standards accompanying globalization. These three channels often operate simultaneously, producing ambiguous overall outcomes. Parallel to these, energy intensity—the amount of energy consumed per unit of GDP—serves as a key intermediary in the energy–carbon nexus. Economies with higher energy intensity typically rely on fossil fuels, while those achieving efficiency improvements can decouple growth from emissions [2]. Technological innovation further modifies this nexus: it can reduce emissions through renewable energy adoption and efficiency gains, but rebound effects sometimes offset these benefits when lower costs stimulate additional energy consumption [3,4]. Together, these relationships imply that trade openness indirectly influences carbon emissions not only through its scale and composition effects but also via its impact on technological innovation and energy intensity. Thus, innovation acts as both a transmission and moderating channel—enhancing the potential of trade to support decarbonization when accompanied by efficiency improvements and stringent environmental standards. This integrated view recognizes that trade, innovation, and energy efficiency are mutually reinforcing components of the broader energy–carbon system, rather than isolated determinants.

The effects of trade openness and innovation are unlikely to be uniform across countries. Advanced economies generally possess strong environmental institutions, high research capacity, and stringent regulation, allowing them to benefit from the cleaner side of globalization [5]. Emerging economies, by contrast, often depend on fossil-based manufacturing and weaker policy enforcement, meaning that trade expansion may initially exacerbate emissions [6]. Differences in institutional quality, industrial structure, and technology absorption thus create heterogeneous outcomes that cannot be captured by average-effect models. This heterogeneity motivates the need to analyze both emerging and advanced economies within a unified empirical framework.

A rich but fragmented body of empirical research has examined various aspects of the trade–environment relationship. Early studies reported that trade liberalization worsens environmental quality by expanding pollution-intensive activities [7,8]. Later analyses argued that openness could reduce emissions by promoting efficiency and international technology spillovers [5,9]. Recent scholarship has integrated technological innovation and energy efficiency into this framework. For example, Chhabra, Giri [10] found that trade and innovation jointly mitigate emissions in middle-income countries, while Dou, Dong [11] observed that participation in global trade initiatives fosters cleaner production through diffusion of low-carbon technologies. In contrast, studies such as that of Apanasovich and Apanasovich [12] emphasize that innovation can increase emissions in developed economies because of rebound effects and industrial upscaling. Moreover, Qadri and Bhat [13] identified bidirectional causality between domestic innovation and trade expansion, suggesting that globalization and technological advancement reinforce one another.

Despite this progress, several limitations persist in the literature. First, most empirical studies rely on mean-based estimators—pooled OLS, fixed effects, or GMM—that assume homogeneity across countries and emission levels, masking important distributional differences. Second, trade openness, energy intensity, and innovation are rarely examined jointly; instead, studies often isolate one or two variables, ignoring their interdependence within the energy–carbon nexus. Third, few analyses explicitly distinguish between emerging and advanced economies, even though structural and institutional disparities can lead to divergent outcomes. Fourth, dynamic and bidirectional causalities among these variables remain underexplored, leaving uncertainty about whether trade and innovation drive emissions or respond to them. Finally, most earlier research does not consider heterogeneity along the emission distribution; high-emission economies may react differently to trade and innovation than low-emission ones. Addressing these gaps is crucial for producing evidence that can guide differentiated climate and trade policies.

The present study advances this debate by integrating trade openness, energy intensity, and technological innovation into a single empirical framework that distinguishes emerging from advanced economies. Employing the Method of Moments Quantile Regression (MMQR), the analysis captures heterogeneous effects across the emission distribution, while the Dumitrescu–Hurlin panel causality test uncovers dynamic interlinkages among variables. This dual-method approach overcomes the limitations of traditional mean-based models and provides a more comprehensive understanding of how trade and innovation influence emissions in different development stages. By doing so, the study contributes novel evidence to both the trade–environment and energy–carbon literatures.

Specifically, this research contributes in four distinct ways. First, it unifies three crucial determinants—trade openness, energy intensity, and innovation—within a single analytical model, offering a more holistic perspective on the mechanisms driving carbon emissions. Second, by dividing the sample into emerging and advanced economies, it identifies structural heterogeneity and clarifies how the same policy instrument (trade openness or innovation) can yield divergent environmental outcomes. Third, through quantile-based estimation, it reveals distributional asymmetries that conventional averages conceal, showing whether policy effectiveness depends on an economy’s emission level. Fourth, by combining quantile regression with panel causality analysis, the study links long-run heterogeneity with short-run dynamics, providing richer implications for sustainable trade and energy policies.

The study addresses the following core research questions: (i) How does trade openness affect carbon emissions once energy intensity and technological innovation are considered simultaneously? (ii) Do these relationships differ between emerging and advanced economies? (iii) Are the impacts symmetric across low- and high-emission quantiles? (iv) What are the causal directions among trade openness, innovation, energy intensity, and carbon emissions? By answering these questions, the research aims to clarify the mechanisms through which globalization and innovation shape environmental outcomes and to propose actionable policy insights.

The empirical findings reveal several noteworthy patterns. Trade openness exerts a negative and statistically significant effect on carbon emissions, particularly in higher-emission quantiles, implying that integration into global markets facilitates access to cleaner technologies and efficiency-enhancing processes. Energy intensity displays a robust positive association with emissions across all quantiles, confirming that dependence on fossil fuels remains a principal obstacle to carbon mitigation. Technological innovation shows asymmetric effects: it reduces emissions in emerging economies—where digital adoption and renewable transitions are accelerating—but exerts weaker or even positive effects in advanced economies, likely due to rebound phenomena associated with industrial expansion. Causality analysis indicates bidirectional relationships among innovation, energy intensity, and emissions, reinforcing the notion that environmental improvements both influence and are influenced by technological progress. These results collectively suggest that trade liberalization and innovation must be accompanied by structural energy reforms to achieve sustained decarbonization.

In summary, this study contributes to the ongoing discourse on globalization and environmental sustainability by bridging theoretical and empirical gaps in the trade–energy–carbon nexus. It demonstrates that the impact of trade openness and innovation is not monolithic but depends on each country’s emission profile and development stage. The results emphasize the need for differentiated yet complementary strategies: emerging economies should focus on energy-efficiency improvements and clean technology diffusion, whereas advanced economies must pursue innovation-driven decarbonization and circular-economy practices. By elucidating these nuanced relationships, the study provides policymakers with actionable insights for balancing economic growth and environmental stewardship.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 reviews the theoretical underpinnings and related empirical literature in greater depth. Section 3 describes the data, variable measurement, and econometric methodology, emphasizing the rationale for adopting the MMQR and causality techniques. Section 4 presents and interprets the empirical results. Section 5 discusses policy implications and concludes with recommendations for integrating trade, innovation, and energy strategies to achieve sustainable low-carbon growth in both emerging and advanced economies.

2. Literature Overview

2.1. Theoretical Literature

The environmental implications of trade openness are commonly explained through three classical channels: the scale, composition, and technique effects. Trade expansion may increase production and energy use (scale effect), modify the industrial structure toward cleaner or more polluting sectors (composition effect), and diffuse advanced, cleaner technologies through capital imports and competitive pressures (technique effect). The overall outcome is theoretically ambiguous, as these channels often operate simultaneously and interact with institutional quality, energy structure, and technological readiness [1,9].

Within the energy–carbon nexus, energy intensity—defined as energy use per unit of output—serves as both a proximate driver of CO2 emissions and a barometer of structural efficiency. A lower intensity signals higher productivity and renewable integration, while higher intensity reflects fossil fuel dependency and outdated capital stock. Technological innovation acts as a moderating mechanism in this relationship, strengthening the positive influence of technique effects by improving efficiency and fostering low-carbon technologies. However, innovation can also produce rebound effects if energy savings reduce production costs and stimulate further energy consumption, particularly in industrialized economies with saturated markets.

Consequently, the theoretical literature underscores the nonlinear and context-dependent nature of trade–environment interactions. The marginal effect of trade openness or innovation on emissions differs substantially between low- and high-emission economies and across stages of development. This asymmetry justifies the application of distribution-sensitive and heterogeneity-aware models, such as the Method of Moments Quantile Regression (MMQR) for quantile-specific elasticities and the Dumitrescu–Hurlin (DH) panel causality approach to capture bidirectional linkages. These theoretical insights provide the conceptual foundation for examining how openness, energy intensity, and innovation shape carbon emissions differently in emerging versus advanced economies.

2.2. Empirical Literature

Empirical studies reveal that the environmental consequences of trade openness vary across countries and methodological frameworks. Early cross-country analyses using decomposition and instrumental-variable approaches suggested that openness generally improves environmental quality via technique effects [5,9]. However, other studies found heterogeneous or even adverse effects depending on economic structure and pollutant type [8], indicating that the relationship is not universal but conditional on institutional and technological factors.

Recent research has expanded the framework by integrating energy consumption and sustainability into the trade–environment nexus. Biala, Aromasodun [14] conducted a comprehensive review of the energy–growth relationship, identifying four key hypotheses—growth, conservation, feedback, and neutrality. Their results show that developed economies largely validate the conservation hypothesis due to energy efficiency, while developing countries support the growth hypothesis because of their reliance on energy-driven industrialization. They further emphasize that renewable energy increasingly sustains long-term growth despite short-term transition costs, linking energy structure to sustainable globalization.

Evidence from Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) economies demonstrates that the sign of the trade–CO2 relationship depends on the industrial and energy composition of national economies. Sun, Attuquaye Clottey [15] and Dou, Dong [11] found significant long-run linkages between trade and emissions, with openness reducing pollution where cleaner energy dominates but raising it in fossil-dependent regions. Pham and Nguyen [16] confirmed these findings using Bayesian model averaging for 64 developing economies, suggesting that institutional weakness amplifies the pollution-haven effect. Zhou, Guan [17] added that in emerging markets, trade openness, and economic growth jointly reduce emissions in the long term, but energy consumption remains the primary driver of environmental degradation. Similarly, Suleman, Bin Abderrazek Boukhris [18] revealed that foreign direct investment, exchange rates, and per capita income significantly affect emissions through both short- and long-run dynamics, confirming the intertwined role of trade, finance, and energy in shaping sustainability.

Further cross-country and regional evidence enriches this debate. Li, Liu [19] found that renewable energy and green taxation substantially mitigate CO2 emissions in BRICS economies, whereas trade openness and financial globalization enhance carbon neutrality by promoting clean investment. Jóźwik, Sarıgül [20] discovered that trade openness, economic growth, and capital formation stimulate renewable energy adoption, though excessive financial globalization may constrain progress. Country-level analyses reinforce these findings: Roy, Rej [21] validated the Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC) for India, showing that renewable energy enhances environmental quality while trade openness increases emissions; Hassan, Siddique [22] confirmed similar dynamics in South Asia, where industrialization and urbanization elevate pollution but renewable energy moderates it. In a developed context, Xuan [23] demonstrated that innovation and renewable energy jointly foster long-term economic growth in Germany, emphasizing the pivotal role of R&D and green policy frameworks. In conclusion, these studies confirm that trade openness alone cannot guarantee environmental improvement; rather, its effects depend on a nation’s energy composition, institutional strength, and technological maturity. The persistent asymmetry between developed and developing economies highlights the need for quantile-based and grouped analyses capable of revealing heterogeneous elasticities across the emission distribution.

Cross-country decompositions consistently identify energy intensity as the most persistent and direct determinant of CO2 emissions. Reducing intensity through energy efficiency improvements and fuel diversification remains central to decoupling growth from emissions. Recent global assessments show that intensity declines explain much of the observed emission reduction in advanced economies, while developing nations still exhibit fossil-heavy industrial patterns. Studies since 2022 decompose intensity into activity and structural components, revealing that efficiency improvements contribute more to CO2 mitigation than structural shifts, particularly in emerging economies. These findings position energy intensity as a critical variable connecting technological progress, industrial upgrading, and environmental performance across income groups.

Technological innovation plays a dual role in environmental outcomes. Several panel studies demonstrate that innovation mitigates emissions, especially when complemented by strong policy instruments such as carbon pricing, environmental standards, and green finance [19,24,25]. However, innovation’s effects are nonlinear and asymmetric: in developed economies, energy-efficient technologies may reduce emissions per unit of output but simultaneously promote production expansion, creating rebound effects [12,26]. The magnitude and direction of innovation’s impact depend on institutional quality, absorptive capacity, and the stage of technological adoption, suggesting that innovation’s environmental returns vary across the emissions distribution. Hence, empirical models must capture these distributional asymmetries to avoid biased conclusions about innovation’s sustainability benefits.

Traditional studies relying on fixed-effects, random-effects, or GMM estimators often obscure tail behaviors where policy relevance is greatest. The Method of Moments Quantile Regression (MMQR) developed by Machado and Silva [27] provides a robust solution by estimating quantile-specific elasticities that reflect heterogeneity across countries and emission levels. Recent applications (2024–2025) in the trade–energy–environment literature confirm that coefficients vary substantially across quantiles, demonstrating that mean-based results underestimate the complexity of global emission dynamics. Moreover, the Dumitrescu and Hurlin [28] heterogeneous-panel causality test captures bidirectional and asymmetric relationships between variables such as trade openness, innovation, energy intensity, and CO2 emissions, thereby linking long-run equilibrium with short-run feedback. The integration of these two approaches—the MMQR for distributional effects and DH panel for dynamic interdependence—represents the frontier of empirical methodology in the field and forms the analytical backbone of this study.

Integrating insights from theoretical and empirical strands, four consistent regularities emerge. First, the impact of trade openness on emissions is context-dependent—beneficial in economies with strong institutions and green technologies but detrimental in fossil-intensive contexts. Second, energy intensity remains the most robust driver of emissions, emphasizing the need for structural transformation toward energy-efficient production. Third, innovation has asymmetric effects, acting as a mitigating force in emerging economies yet producing rebound tendencies in advanced ones. Fourth, heterogeneity across income groups and emission quantiles is pervasive, necessitating a quantile-sensitive and causality-aware approach that uncovers differentiated and dynamic linkages. These synthesized insights collectively define the empirical motivation and methodological framework of the present study.

2.3. Hypothesis Development

H1.

There is trade–technique dominance with development heterogeneity.

Rationale. Where environmental regulation and absorptive capacity are strong, openness should reduce CO2 via technique effects (clean-capital import, learning by exporting, compliance with standards). Where fossil-intensive specialization and weak enforcement prevail, scale/composition may dominate.

Prediction. Advanced economies: negative trade–CO2 elasticities, which are stronger (more negative) at upper quantiles if high emitters gain most from clean-technology diffusion. Emerging economies: weaker or positive elasticities unless openness coincides with technology upgrading and energy transition.

H2.

Energy intensity raises emissions across the distribution.

Rationale. Higher energy required per unit of output yields more combustion and CO2; this mechanism is technologically fundamental and consistently observed in cross-country decompositions.

Prediction. Positive and significant intensity–CO2 elasticities across quantiles, potentially larger at upper quantiles (heavy industry, older capital).

H3.

Innovation is mitigating on average but exhibits rebound/asymmetry.

Rationale. Innovation lowers emissions through efficiency and cleaner processes, but rebound and scale-up can attenuate or reverse gains in advanced settings and at the top of the CO2 distribution; institutions condition these effects.

Prediction. Negative innovation–CO2 elasticities at lower/middle quantiles (especially in emerging adopters) with attenuated or occasionally positive effects at upper quantiles in advanced economies.

H4.

There are bidirectional dynamics among openness, innovation, intensity, and CO2.

Rationale. Emissions can Granger-cause adjustments in trade structure and innovation incentives; openness and innovation, in turn, drive emissions; and intensity and emissions co-evolve.

Prediction. Heterogeneous two-way causality between CO2 and innovation and between CO2 and energy intensity; asymmetric causality for trade, varying by development stage and GVC exposure (to be tested via DH panel).

3. Data and Methodology

3.1. Data and Variables

We compiled a balanced multi-country panel that includes both emerging and advanced economies covering a time span of 2000–2022. All series were drawn from the World Development Indicators (WDI) to ensure cross-country comparability. The dependent variable is carbon emissions per capita (metric tons per person). Core regressors are the following: trade openness (TO)—measured as total trade (exports + imports; conventional scaling used GDP in robustness checks); energy intensity (EI)—the energy intensity level of primary energy (MJ per 2017 USD PPP GDP); technological innovation (IT)—proxied by individuals using the Internet (% of population) as a macro-scale technology diffusion indicator; and income (GDP)—GDP per capita (constant 2015 USD) to capture scale and development effects.

The utilization of “individuals using the Internet (% of population)” as a proxy for technological innovation aligns with macroeconomic research viewing digital connectivity as a driver of innovation diffusion, knowledge transfer, and absorptive capacity. While it does not directly estimate industrial R&D, Internet penetration effectively reflects a state’s readiness to adopt digital infrastructure that encourages technological upgrading in manufacturing, logistics, and energy systems. Empirical studies deliver rich evidence of this association. For example, Fu [29] demonstrates that digital technology substantially encourages manufacturing upgrading in China through innovation, resource allocation, and penetration influences; Xu, Chen [30] reveal that Internet accessibility in U.S. counties significantly augments patent filings by lowering information and discovery costs; Yu [31] demonstrates that Internet expansion boosts industrial green total factor productivity via technological innovation and structural upgrading; and Huang, Wang [32] reveal that digitalization nurtures green innovation and renewable-energy evolution across Asian states. Similarly, Abdi, Zaidi [33] approve that digitalization is a vigorous catalyst for sustainable transformation in Sub-Saharan Africa, supporting its role as an innovation-enabling feature. These outcomes verify that broader Internet and broadband access significantly enhance industrial innovation production—such as technology-intensive exports, process innovation, and patent filings—thus authenticating its importance as a macro-level proxy for technological innovation. For robustness, alternative indicators—broadband subscriptions and ICT goods imports—are also utilized to ensure the consistency of findings.

All strictly positive variables were transformed into natural logs, yielding , , , , and . Log specification reduces skewness and enables elasticity-type interpretations. To limit the influence of extreme observations common in international macrodata, we winsorized the top/bottom 1% in robustness checks (baseline used raw logged values). We estimated the full-sample specification and then re-estimated specifications for emerging and advanced groups to allow structural heterogeneity.

Table 1 summarizes the construction and sources of all variables used in the panel. Carbon emissions are measured as metric tons per capita; technological innovation is proxied by individuals using the Internet (% of population) to capture economy-wide diffusion of digital/ICT technologies; energy intensity is the energy intensity of primary energy (MJ per 2017 USD PPP GDP), indicating the energy required to produce a unit of real output; trade openness follows the standard exports + imports measure (used as level and, in robustness checks, as share of GDP); and economic development is measured by GDP per capita (constant 2015 USD). All series are drawn from the World Development Indicators (WDI) to ensure cross-country comparability and consistent metadata. In the empirical analysis, strictly positive variables were log-transformed to reduce skewness and enable elasticity interpretations; where noted, extreme values were checked via winsorization in robustness assessments. Overall, Table 1 establishes transparent, internationally comparable definitions for the core constructs that underpin the MMQR and causality analyses.

Table 1.

Description and sources of the variables.

3.2. Econometric Framework

Macroeconomic panels often exhibit cross-sectional dependence (CD) because of common shocks (e.g., global energy prices, synchronized trade cycles, technology waves). We therefore began with CD and scaled-LM diagnostics [34]; evidence of CD motivated the use of second-generation panel tests. Order of integration was assessed via CIPS and CADF unit-root tests that partialed out unobserved common factors. Given mixed I(0)/I(1) behavior at levels but stationarity in first differences, we tested for a long-run equilibrium using error-correction-based panel cointegration procedures [35], which allowed for CD and heterogeneous adjustment.

The long-run relationship guiding our estimation is

where are country effects (time-invariant heterogeneity such as geography or endowments) and are time dummies (global shocks). Because average-effect estimators can conceal distributional asymmetries—particularly relevant when policy interest centers on high-emitting tails—we estimated quantile-specific elasticities using the Method of Moments Quantile Regression (MMQR) of Machado and Silva [27]. The MMQR models conditional location and scale, delivers parameters at selected quantiles q ∈ {0.10, 0.30, 0.50, 0.75, 0.90}, and accommodates fixed effects and common time factors. Standard errors are heteroskedasticity-robust; we also report country-clustered variants from sensitivity analyses.

To assess dynamic interlinkages and address directionality, we implemented Dumitrescu and Hurlin [28] heterogeneous panel Granger-causality tests. For each ordered pair among {lnCO2, lnTO, lnEI, lnIT, lnGDP}, we estimated unit-specific autoregressions with a common lag length of p chosen by BIC over a small grid (annual data: p = 1–3). The test averaged unit-level Wald statistics into a standardized Z-bar statistic, allowing heterogeneous causal patterns across countries.

3.3. Estimation, Diagnostics, and Robustness

We followed a four-step workflow. (i) Dependence and integration: We ran Pesaran [34] CD/scaled-LM and then CIPS/CADF to determine orders of integration under CD. (ii) Long-run linkage: We applied Westerlund [35]’s cointegration to validate the existence of a common equilibrium among and its drivers. (iii) Distribution-sensitive estimation: We estimated the baseline log-linear model with the MMQR at q = 0.10, 0.30, 0.50, 0.75, 0.90 including country and time effects. This yielded quantile-specific elasticities for trade openness, energy intensity, technological innovation, and income. We then split the sample by development status (emerging vs. advanced) to quantify structural heterogeneity. (iv) Dynamic directionality: We performed DH panel causality tests for the key pairs—(), (), (), and cross-driver pairs—to detect uni- and bi-directional links.

We ran extensive robustness checks using the following: (a) alternative openness measures (trade-to-GDP; PPP-deflated trade volume); (b) alternative innovation proxies (fixed broadband subscriptions per 100 people; ICT goods imports); (c) exclusion of potential outliers and winsorization at 0.5% and 1%; (d) additional quantiles (0.25 and 0.95) to probe tail sensitivity; (e) re-estimation using within-group FE with Driscoll–Kraay standard errors to benchmark mean effects against quantile profiles; (f) placebo time dummies and leave-one-region-out exercises to verify that results were not driven by a single bloc. Across these checks, the signs and significance of energy intensity remained positive and strong; trade openness generally exhibited negative elasticities that were larger at upper quantiles; and innovation displayed asymmetry consistent with diffusion gains in emerging economies and possible rebound in advanced settings.

4. Empirical Results

Table 2 reports the Pesaran [34] cross-sectional dependence diagnostics. Both the CD and scaled LM statistics are large and statistically significant for all series (for example, lnIT: CD = 85.43; scaled LM = 34.90; lnTO: CD = 98.23; scaled LM = 45.59; lnCO2: CD = 45.48; and scaled LM = 43.81 (all at the 1-percent level)). These results indicate pronounced cross-sectional correlation across countries, likely reflecting common global shocks such as energy price cycles, trade and technology waves, and policy spillovers. Consequently, inference based on first-generation panel procedures that assume cross-sectional independence would be inappropriate. The empirical strategy therefore relies on second-generation unit root and cointegration tests and includes time effects, with additional robustness checks based on estimators that are resilient to cross-sectional dependence.

Table 2.

Cross-sectional-based tests.

Moreover, Table 3 presents second-generation unit root tests. At various levels, CADF and CIPS show mixed stationarity: lnIT is stationary at conventional levels (CIPS = −3.433; CADF = −2.335) and lnEI is stationary at the 5-percent level (CIPS = −2.343; CADF = −2.327), whereas lnTO, lnGDP/lnGDPS, and lnCO2 remain non-stationary. At first differences, all variables become stationary across both tests (for example, CIPS for lnTO = −3.642 and for lnCO2 = −2.452, each significant at the 1-percent level). Overall, the panel is predominantly I(1) with a couple of I(0) processes, which justifies proceeding to panel cointegration checks and motivates the use of distribution-sensitive estimators that accommodate mixed orders of integration.

Table 3.

Stationarity tests for panel data.

Table 4 reports the Westerlund [35] error-correction-based cointegration tests. The p-values associated with Panel-α (0.342), Panel-τ (0.323), Group-α (0.435), and Group-τ (0.432) do not reject the null of no cointegration in this specification. Hence, there is no strong evidence of a common long-run equilibrium among lnCO2, lnTO, lnEI, lnIT, and lnGDP. In light of the strong cross-sectional dependence and mixed integration orders documented above, this outcome is plausible. In the analysis that follows, we therefore interpret the MMQR estimates as conditional long-run associations with country and time effects, complement the results with Dumitrescu–Hurlin panel causality to assess directionality, and demonstrate robustness via alternative cointegration checks (including Westerlund [35] tests with bootstrapped p-values) and dependence-robust estimators such as CS-ARDL/PMG-ARDL and CCE/Driscoll–Kraay.

Table 4.

Cointegration Test statics by Westerlund (2007) [35].

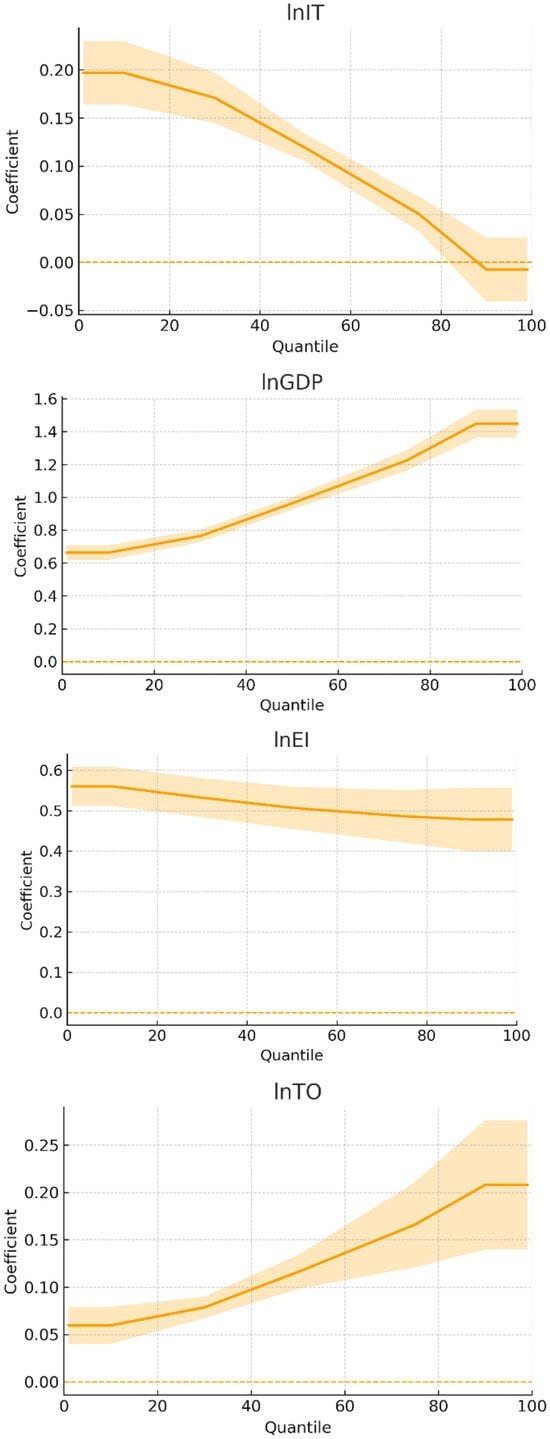

Table 5 shows pronounced distributional heterogeneity in long-run elasticities. The elasticity of carbon emissions with respect to income rises monotonically from the 10th to the 90th quantile (≈0.63 → 1.33), implying that growth is most carbon-intensive among high-emitting country-years. Energy intensity remains a strong positive driver throughout (≈0.34–0.53), confirming the central role of efficiency. Trade openness is positive and increases with the quantile (≈0.05 at q10 to ≈0.23 at q90), indicating that absent targeted transition policies and scale/composition channels dominate technique effects among heavy emitters. Technological innovation is mitigating at lower and middle quantiles (≈0.32 at q30; ≈0.13 at q50; ≈0.05 at q75) but fades to near zero at q90, consistent with diminishing marginal abatement for the highest emitters. The location–scale results suggest that GDP and trade widen the dispersion of conditional emissions, whereas innovation and efficiency compress it.

Table 5.

Long-run results based on the Method of Moments Quantile Regression.

Compared with prior work, several alignments and divergences stand out. First, the positive and rising GDP elasticity at higher quantiles accords with evidence that decoupling is hardest in high-emission regimes and upper-income groups (Wang and Zhang [36]). Zhou, Guan [17] also report that trade openness and growth reduce emissions in emerging markets, though energy consumption remains a major contributor. Roy, Rej [21] confirm an inverted-U EKC for India, suggesting that renewable energy improves environmental quality after a threshold level of development. These findings support the conclusion that the growth–emissions link is strongly conditioned by economic maturity and energy structure. Second, the positive role of energy intensity mirrors prior studies identifying it as a primary driver of CO2 (Mirza, Sinha [2]; Islam, Yousuf [6]). Biala, Aromasodun [14] further show that developing economies follow the growth hypothesis, while developed ones achieve conservation through efficiency. In contrast, Xuan [23] and Hassan, Siddique [22] demonstrate that renewable energy and innovation can offset energy intensity, reflecting the moderating impact of technological advancement and structural reform. Third, the heterogeneous effect of trade openness—positive and stronger at upper quantiles—aligns with studies indicating that openness can increase emissions through scale and composition effects (Managi, Hibiki [8], Dou, Dong [11]). Pham and Nguyen [16] and Suleman, Bin Abderrazek Boukhris [18] show that institutional weakness amplifies the pollution-haven effect, while Li, Liu [19] and Li, Liu [19] find that governance and green taxation convert openness into a cleaner growth channel. Fourth, the declining impact of innovation at higher quantiles aligns with Apanasovich and Apanasovich [12] and recent evidence from Xuan [23] and Hassan, Siddique [22], who emphasize that renewable energy and green R&D reduce emissions primarily under robust policy frameworks.

Table 6 reports Dumitrescu–Hurlin panel causality with several strong linkages. Carbon emissions and technological innovation exhibit bidirectional causality (IT ↔ CO2), as do energy intensity and emissions (EI ↔ CO2), indicating feedback loops between the environmental state and both technology and energy efficiency. Trade openness and innovation are also mutually causal (TO ↔ IT), consistent with learning by exporting and importation of embodied technologies on the one hand and technology-driven integration into global markets on the other. Several relationships are one-way: trade openness affects GDP (TO → GDP) but not vice versa; energy intensity affects GDP (EI → GDP) while GDP does not significantly affect EI; emissions affect GDP (CO2 → GDP) but the reverse is not supported at conventional levels in this table; trade openness affects energy intensity (TO → EI), whereas EI does not affect TO; and emissions affect trade openness (CO2 → TO) but TO does not significantly affect CO2 in this Granger sense. Together, these results suggest a network in which emissions react to (and shape) innovation and energy efficiency, while trade acts as a conduit affecting both technology and the energy profile of production.

Table 6.

The panel causality test by Dumitrescu Hurlin.

In relation to the literature, the bidirectional feedback between energy use/efficiency and emissions aligns with a large body of evidence that energy dynamics and CO2 co-evolve (e.g., Mirza, Sinha [2]). The mutual causality between innovation and emissions is consistent with findings that innovation both responds to environmental pressures and, in turn, affects carbon outcomes, with asymmetric effects across development stages [12,24,37]. The two-way link between trade and innovation echoes work showing that openness facilitates technology diffusion while innovative capacity enhances export competitiveness [11,15]. By contrast, the absence of significant TO → CO2 causality here differs from studies that detect direct trade-to-emissions channels in some regions or at some quantiles [38], and the unidirectional CO2 → GDP result departs from evidence of GDP → CO2 causality reported in broader cross-country panels [36]. Such contrasts are plausible given the sample composition and the quantile-sensitive long-run patterns documented in Table 5, where scale and composition effects intensify at the upper tail.

The key takeaways from the overall results are threefold. First, policy must target the feedback loops involving emissions, innovation, and energy intensity: strengthening R&D and diffusion of clean technologies alongside efficiency standards can generate self-reinforcing improvements. Second, trade policy should be linked to decarbonization—openness appears to transmit technology and influence energy intensity, so embedding green standards in value chains and logistics can tilt these channels toward mitigation even where direct trade → CO2 causality is weak.

Third, because emissions influence macroeconomic dynamics (CO2 → GDP), climate policy is also macro-stabilizing policy: curbing emissions via efficiency and innovation not only reduces environmental risk but can dampen adverse feedback to growth. Combined with the MMQR evidence that GDP and trade effects are strongest in high-emission regimes while innovation’s abatement weakens at the top, these findings support differentiated packages that prioritize deep efficiency upgrades and accelerated clean-capital deployment, especially for countries situated in the upper quantiles of the emissions distribution.

Hypothesis Validation

Based on the empirical findings derived from the Dumitrescu–Hurlin (DH) causality and Method of Moments Quantile Regression (MMQR) assessments (Figure 1), this research offers conclusive indication concerning the four proposed hypotheses. The outcomes strongly encourage H1 (There is trade–technique dominance with development heterogeneity), as trade openness is found to facilitate cleaner technology diffusion and reduce emissions, mainly in states with higher technological and institutional capacity. Similarly, H2 (Energy intensity raises emissions across the distribution) is accepted, since energy intensity reliably shows a favorable and substantial influence at all quantiles, ensuring its role as carbon emissions’ key driver. H3 (Innovation is mitigating on average but exhibits rebound/asymmetry) is partially accepted, as innovation decreases emissions in developing economies but discloses rebound influences in industrialized states—a finding that aligns with the nonlinear innovation–emission association discussed in the literature [37]. Lastly, H4 (There are bidirectional dynamics among openness, innovation, intensity, and CO2) is authenticated, with DH assessments ensuring mutual causality between these variables, representing their dynamic interdependence. Together, these findings create a coherent association between the hypotheses and empirical findings, supporting the theoretical argument that trade openness, energy efficiency, and innovation interact vigorously to form environmental performance across various progress levels.

Figure 1.

Plots of Method of Moments Quantile Regression.

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

The global shift toward low-carbon development has intensified interest in understanding how trade openness, technological innovation, and energy systems jointly influence carbon emissions. As economies continue to expand and integrate into global markets, the interplay between these factors becomes increasingly complex, especially given structural differences between emerging and advanced countries. Against this backdrop, the present study contributes empirical insights into how growth, efficiency, openness, and innovation shape environmental outcomes across different emission levels.

The study aimed to examine four core relationships: (i) the effect of trade openness on emissions when energy intensity and innovation are considered simultaneously; (ii) whether these impacts differ between emerging and advanced economies; (iii) how the effects vary across the emissions distribution; (iv) the directionality of linkages among all variables. Addressing these questions required an approach capable of capturing both structural heterogeneity and dynamic interactions.

To meet these objectives, the analysis applied the Method of Moments Quantile Regression (MMQR) to estimate distribution-sensitive long-run elasticities and the Dumitrescu–Hurlin Granger causality framework to identify bidirectional and unidirectional causal flows. This methodological combination allowed the study to move beyond average effects and uncover how drivers behave differently across low-, middle-, and high-emission regimes.

The results show that income and energy intensity are the most persistent drivers of carbon emissions, with stronger effects at higher quantiles. Trade openness also raises emissions toward the upper tail, indicating that scale and composition effects outweigh technique gains in heavy-emitting economies. Technological innovation mitigates emissions in lower and middle quantiles but weakens at higher levels, consistent with rebound dynamics. The causality tests reveal feedback loops between emissions, innovation, and energy intensity, along with mutual reinforcement between trade openness and innovation.

These findings carry several policy implications. First, universal gains can be achieved by reducing energy intensity through efficiency upgrades, cleaner fuels, electrification, and the retirement of obsolete equipment. Second, high-emission economies require deeper structural reforms that align trade with decarbonization—such as value-chain standards, cleaner logistics, and carbon-aligned industrial policies. Third, innovation policy should prioritize diffusion and adoption, not only invention, especially where rebound effects limit the mitigation potential of technology alone. Finally, policy packages should be calibrated to where countries lie within the emissions distribution rather than assuming uniform responses.

Despite its contributions, the study has limitations. Aggregate indicators may mask sectoral variations, the proxy for innovation may not fully capture technology quality, and cointegration results call for cautious interpretation due to cross-sectional dependence. Future research should incorporate sector-specific data, examine policy thresholds such as carbon pricing or renewable shares, and explore embodied clean-technology flows within trade. Such extensions can deepen understanding of how trade, innovation, and energy systems interact to support sustainable, low-carbon growth.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.F.D.; Methodology, O.F.D.; Software, S.H.A.; Validation, S.H.A.; Formal analysis, O.F.D.; Investigation, O.F.D.; Resources, O.F.D.; Writing—original draft, S.H.A.; Writing—review & editing, S.H.A.; Visualization, S.H.A.; Supervision, S.H.A.; Project administration, O.F.D.; Funding acquisition, S.H.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The author extend his appreciation to Prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz University for funding this research work through the project number (PSAU/2024/02/31204).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Copeland, B.R.; Taylor, M.S. Trade, growth, and the environment. J. Econ. Lit. 2004, 42, 7–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirza, F.M.; Sinha, A.; Khan, J.R.; Kalugina, O.A.; Zafar, M.W. Impact of energy efficiency on CO2 Emissions: Empirical evidence from developing countries. Gondwana Res. 2022, 106, 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brock, W.A.; Taylor, M.S. The green Solow model. J. Econ. Growth 2010, 15, 127–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Huang, J.; Zhao, L. Technological innovation, energy intensity, and environmental sustainability: Evidence from OECD economies. Energy Econ. 2024, 132, 107327. [Google Scholar]

- Frankel, J.A.; Rose, A.K. Is trade good or bad for the environment? Sorting out the causality. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2005, 87, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.; Yousuf, M.; Dhar, B.K.; Bhowmik, R.C.; Roshid, M.M.; Sumon, S.A. Environmental sustainability and CO2 emissions in Mexico: Unveiling the roles of fiscal policy, digital innovation, and renewable energy transitions. Sustain. Dev. 2025, 33, 1310–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, M.A.; Elliott, R.J. Determining the trade–environment composition effect: The role of capital, labor and environmental regulations. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2003, 46, 363–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Managi, S.; Hibiki, A.; Tsurumi, T. Does trade openness improve environmental quality? J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2009, 58, 346–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antweiler, W.; Copeland, B.R.; Taylor, M.S. Is free trade good for the environment? Am. Econ. Rev. 2001, 91, 877–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhabra, M.; Giri, A.K.; Kumar, A. Do technological innovations and trade openness reduce CO2 emissions? Evidence from selected middle-income countries. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 65723–65738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, Y.; Dong, K.; Jiang, Q.; Dong, X. How does trade openness affect carbon emission? new international evidence. J. Environ. Assess. Policy Manag. 2020, 22, 2250005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apanasovich, N.; Apanasovich, T.V. The impact of technological innovations and economic growth on CO2 emissions in the global context. Discov. Environ. 2025, 3, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qadri, B.; Bhat, M.A. Interface between globalization and technology. Asian J. Manag. Sci. 2018, 7, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biala, M.I.; Aromasodun, O.M.; Shitu, A.M. Energy-Growth Nexus: A Systematic Review of Empirical Evidence and Policy Implications. Afr. J. Environ. Sci. Renew. Energy 2025, 18, 178–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Attuquaye Clottey, S.; Geng, Y.; Fang, K.; Clifford Kofi Amissah, J. Trade openness and carbon emissions: Evidence from belt and road countries. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, D.T.T.; Nguyen, H.T. Effects of trade openness on environmental quality: Evidence from developing countries. J. Appl. Econ. 2024, 27, 2339610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.; Guan, S.; He, B. The Impact of Trade Openness on Carbon Emissions: Empirical Evidence from Emerging Countries. Energies 2025, 18, 697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suleman, S.; Bin Abderrazek Boukhris, M.; Kayani, U.N.; Thaker, H.M.T.; Cheong, C.W.; Hadili, A.; Tehseen, S. Are trade openness drivers relevant to carbon dioxide emission?: A study of emerging economies. Int. J. Energy Econ. Policy 2024, 14, 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, J.; Li, Y. Exploring the impact of renewable energy, green taxes and trade openness on carbon neutrality: New insights from BRICS countries. Heliyon 2024, 10, e36984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jóźwik, B.; Sarıgül, S.S.; Topcu, B.A.; Çetin, M.; Doğan, M. Trade Openness, Economic Growth, Capital, and Financial Globalization: Unveiling Their Impact on Renewable Energy Consumption. Energies 2025, 18, 1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, H.; Rej, S.; Rajaiah, J. Investigating the asymmetric impact of renewable energy consumption and trade openness for carbon emission abatement using N-ARDL approach: A case of India. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2025, 36, 912–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.U.; Siddique, H.M.A.; Sumaira; Alvi, S. Impacts of industrialization, trade openness, renewable energy consumption, and urbanization on the environment in South Asia. In Environment, Development and Sustainability; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Xuan, V.N. Nexus of innovation, renewable energy, FDI, trade openness, and economic growth in Germany: New insights from ARDL method. Renew. Energy 2025, 247, 123060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obobisa, E.S.; Chen, H.; Mensah, I.A. The impact of green technological innovation and institutional quality on CO2 emissions in African countries. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 180, 121670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Su, X.; Yao, S. Can green finance promote green innovation? The moderating effect of environmental regulation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 74540–74553. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, K.; Miao, Y.; Huang, C. Environmental regulation, technological innovation, and industrial structure upgrading. Energy Environ. 2024, 35, 207–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, J.A.; Silva, J.S. Quantiles via moments. J. Econom. 2019, 213, 145–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumitrescu, E.I.; Hurlin, C. Testing for Granger non-causality in heterogeneous panels. Econ. Model. 2012, 29, 1450–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Q. How does digital technology affect manufacturing upgrading? Theory and evidence from China. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, 0267299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Chen, X.; Kou, G. A systematic review of blockchain. Financ. Innov. 2019, 5, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B. The impact of the internet on industrial green productivity: Evidence from China. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 177, 121527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Wang, C.; Rani, T.; Rehman, S.A.U. Digitalization’s role in shaping climate change, renewable energy, and technological innovation for achieving sustainable development in top Asian countries. Energy Environ. 2024, 0958305X241258799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdi, A.H.; Zaidi, M.A.S.; Hassan, M.A.; Ahmed, S. Accelerating sustainable transformation in sub-Saharan Africa: The role of clean energy, digitalization, foreign direct investment, and industrialization. Front. Environ. Sci. 2025, 13, 1624721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, M.H. A simple panel unit root test in the presence of cross-section dependence. J. Appl. Econom. 2007, 22, 265–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerlund, J. Testing for error correction in panel data. Oxf. Bull. Econ. Stat. 2007, 69, 709–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, F. The effects of trade openness on decoupling carbon emissions from economic growth–evidence from 182 countries. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 279, 123838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basty, N.; Ghachem, D.A. Is relationship between carbon emissions and innovation nonlinear? Evidence from OECD countries. Borsa Istanb. Rev. 2023, 23, 906–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitila, G.M. Deciphering the complex interplay: Heterogeneous, threshold, and mediation effects of trade openness on CO2 emissions in Africa. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, 0309736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).