Abstract

Urban trees are vital for air pollution mitigation, but their function is often compromised by exposure to particulate matter (PM), which impairs physiological processes and reduces growth. Enhancing tree resilience is therefore essential for maintaining their ecosystem services in polluted urban environments. This study examined the early growth and biochemical responses of Norway spruce (Picea abies) and Norway maple (Acer platanoides) seedlings to foliar PM exposure and assessed whether biochar (BC) soil amendment can alleviate PM-induced stress. Seedlings were cultivated outdoors under three treatments: Control (no treatment), PM (foliar exposure to particulate matter), and PM + BC (PM exposure with 10% biochar added to the substrate). Results revealed that Norway maple showed significant biochemical sensitivity to PM, including substantial reductions in chlorophyll and increases in antioxidant activity. However, Norway spruce showed more moderate pigment changes but reduced height growth. BC modulated oxidative and phenolic responses (TPC, TFC, MDA) and partially mitigated PM-induced stress, although its effectiveness varied by species. For Norway spruce, BC significantly enhanced resilience by restoring height growth, stabilizing pigments, and reducing oxidative stress compared with treatment using PM alone. In contrast, for Norway maple, BC failed to restore chlorophyll levels and increased oxidative and phenolic activity, yielding mixed outcomes. Despite physiological differences between the two species, multivariate PCA consistently showed that PM-treated seedlings diverged from the control cluster, whereas PM + BC-treated seedlings were closer to the controls, with mitigation substantially stronger in Norway spruce. These findings demonstrate that biochar can reduce PM-induced stress, but its successful implementation depends fundamentally on selecting appropriate species traits and understanding their specific metabolic response strategies.

1. Introduction

Air pollution is among the most serious environmental threats to human health and a major contributor to climate change, significantly disrupting global ecosystems. Particulate matter (PM) is one of the most critical air pollutants, posing significant health risks to humans and stressing vegetation, particularly in urban and industrial areas []. Anthropogenic PM in the air originates from various sources, including industrial emissions, vehicle exhaust, and biomass burning.

In urban environments, vegetation—particularly trees—provides essential ecosystem services, including the deposition, accumulation and filtration of airborne PM, and the sequestration of atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) through biomass accumulation [,]. However, trees are adversely affected by pollutants they help mitigate, as exposure to PM can lead to reduced photosynthetic efficiency, altered stomatal conductance, impaired physiological processes, and reduced growth due to both surface deposition and internal stress mechanisms [,,]. To address this paradox, it is essential to develop strategies that both preserve the environmental benefits of urban greenery and enhance plant health, thereby sustaining or extending their functional effectiveness over time.

One promising approach is to examine the combined effects of atmospheric pollution and soil or substrate amendments, such as biochar (BC), to evaluate their potential to enhance tree resilience while preserving ecological functions []. The BC is a carbon-rich byproduct composed of the fine-granular material remaining after pyrolysis, which is the process of rapidly combusting a biomass feedstock in the absence of oxygen []. Previous studies have shown that BC amendment can significantly improve soil quality by increasing phosphorus (P) and potassium (K) levels and enhancing water-holding capacity [,,,]. These improvements have been linked to greater tolerance of trees to water stress, enhanced carbon sequestration due to improved growth conditions, and increased total biomass production in trees grown in BC-amended soils [,,,]. Bong et al. [] demonstrated that incorporating BC into compost can reduce nutrient losses, promote humification, and improve N retention in the soil. The application of BC in urban tree planting can enhance soil aeration, increase moisture retention, and supply superior nutrients, thereby promoting healthier tree growth and improving their resilience against adverse environmental effects [,,]. More specifically, BC could serve as an alternative to organic and inorganic components in container-grown media. Its properties support plant growth and show potential to replace peat and inorganic materials in the production of container crops, including forest and urban trees [,]. The early establishment stages represent the most critical period for urban trees, during which limited root development, poor soil conditions, and inadequate water availability result in reduced growth and vitality [,]. In addition to its function as a suitable component of growing media, BC can also provide additional advantages by enhancing numerous biogeochemical processes [].

This study aimed to evaluate the early growth and biochemical responses of young Norway spruce (Picea abies (L.) H. Karst.) and Norway maple (Acer platanoides L.) seedlings to particulate matter (PM) exposure, and to assess whether biochar (BC), when applied as a soil amendment, can mitigate the impact of PM. Our hypothesis was that PM exposure negatively affects the physiological performance of Norway maple and Norway spruce seedlings, while BC amendment mitigates PM-induced stress by enhancing antioxidant activity and maintaining pigment stability, with responses differing between species. The two tree species were selected to represent contrasting physiological strategies and ecological adaptations. Previous studies have shown that Norway maple demonstrates relatively high tolerance and adaptability to PM exposure and is therefore frequently prioritized for urban planting [,]. In contrast, although conifers are generally effective in removing fine particulate matter (PM2.5) from the atmosphere [], Norway spruce tends to display greater physiological sensitivity to PM pollution [].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Layout and Treatments

The experiment was conducted in the experimental nursery at the Lithuanian Research Centre for Agriculture and Forestry during the vegetation seasons in 2023 and 2024. For the experiment, two-year-old seedlings of Norway spruce and Norway maple were selected from Dubrava Forest nursery (State Forest Enterprise, Vilnius, Lithuania) and Kołaki–Wietrzychowo nursery (Białystok, Poland), respectively. In April 2023, the seedlings were planted individually in 5 L plastic pots with perforated bases. A neutralized peat substrate (SuliFlor SF2, Sulinkiai, Lithuania) was used, featuring a pH of 5.5–6.5 and optimal nutrient concentrations: total soluble nitrogen (210 mg L−1), phosphorus pentoxide (P2O5, 240 mg L−1), and potassium oxide (K2O, 270 mg L−1), plus minor elements. Throughout the experiment, seedlings were watered regularly.

The study was conducted in a randomized block design with three replications, each consisting of 21 seedlings. The experiment included two treatment groups, such as application of a single particulate matter (PM) on Norway spruce and Norway maple seedlings foliage (treatment 1: PM); application of PM on seedlings foliage in a combination with biochar (BC), added into soil substrate (treatment 2: PM + BC), and a control group with untreated seedlings (no treatment: control). For both treatments, the PM particles were ≤10 µm in size [] with the dominant PM fraction ranging from 2 to 5 µm. The PM was obtained from forest biomass taken from a heating boiler multicyclone in Girionys (Kaunas district, Lithuania). Each seedling was exposed to 0.4 g of PM every 8 ± 2 days from May to August 2024. Unsuitable or extreme weather conditions were avoided.

For the PM + BC treatment, BC derived from forest residues (particle size ≤15 mm; pH 7.1; nutrient content: 5 mg L−1 N, 19.6 mg L−1 P, 183 mg L−1 K) was incorporated into the substrate at an application rate of approximately 10%. The BC application rate was determined based on prior studies showing BC efficacy, such as Aung et al. [] and Köster et al. [], which suggest using a growing medium with no more than 10% BC to enhance the quality and growth of nursery seedlings. The BC was mixed into the substrate before the experiment, specifically, before the growing season in March 2024.

2.2. Measurements and Analysis

For all seedlings, total height (H, cm) and diameter at stem base (D, mm) were measured at the beginning of the experiment, before active vegetation (March 2023), and at the end of the vegetation season (September 2024). The seedling growth increment was analysed as the annual increment in stem H and D by calculating the difference between the March and September values.

For biochemical analysis, current-year foliage (Norway spruce needles and Norway maple leaves) was sampled at the end of the 2024 vegetation season from the control, PM, and PM + BC treatment groups. Nine seedlings per species and treatment were randomly selected, and samples were pooled from 15 to 20 needles for Norway spruce and 5–10 leaves for Norway maple. Foliage samples were homogenized, extracted and centrifuged, then the supernatant was used to measure photosynthetic pigments (Chlorophylls a and b), total polyphenols (TPC), flavonoids (TFC), soluble sugars (TSS), and malondialdehyde (MDA). Full protocols for the analysis were described in detail by Beniušytė et al. [], Černiauskas et al. [] and Sirgedaitė-Šėžienė et al. [], with key procedures summarized as follows: pigment concentrations were determined spectrophotometrically at 470, 648, and 664 nm; TPC was measured using the Folin–Ciocalteu method at 725 nm with gallic acid as the calibration standard; TFC was assessed via Al(III) complexation at 415 nm using quercetin as a standard; TSS was determined with anthrone reagent at 620 nm and expressed as glucose equivalents; and MDA content was analyzed using thiobarbituric acid in trichloroacetic acid, with absorbance measured at 440, 532, and 600 nm.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed in RStudio (version 4.1.2). The Kruskal–Wallis H test for independent samples was applied when data did not meet the assumptions of normality or homogeneity of variance, followed by pairwise rank comparisons using Dunn’s test (p < 0.05).

Principal component analysis (PCA) was applied to standardized (z-score) pigment and antioxidant variables (Chl a, Chl b, Car, TPC, TFC, TSS, MDA) to assess multivariate responses to PM and biochar treatments. For each species, and for the combined dataset, three two-dimensional projections (PC1–PC2, PC1–PC3, PC2–PC3) were generated to visualize treatment-related separation. For each species and treatment group, 95% confidence ellipses were calculated to visualize within-group variability. Plotting was performed using the ggplot2 package in R.

3. Results

3.1. Stem Growth Responses

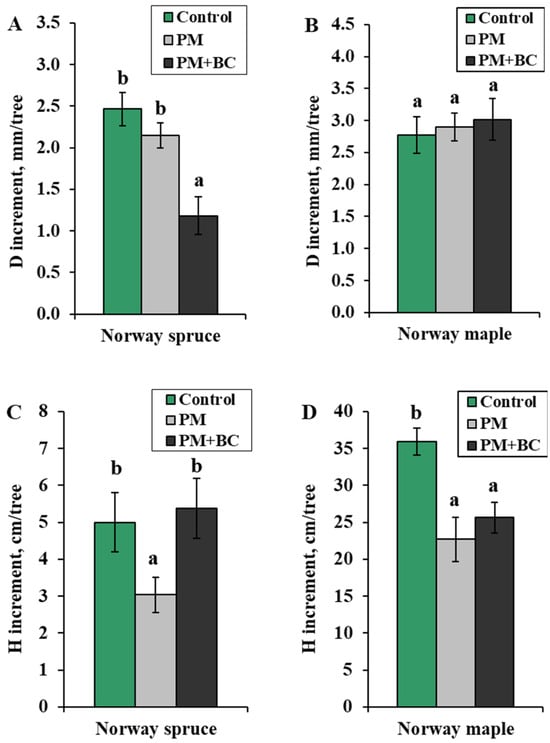

Our results showed that Norway spruce and Norway maple differed in seedling growth responses to PM and BC treatments. The single PM treatment did not significantly impact the diameter of Norway spruce seedling stems but decreased their height (Figure 1A,C). The Norway spruce seedlings exposed to a PM treatment and cultivated in a substrate enriched with BC (PM + BC treatment) showed a reduced stem diameter. The control group has the highest stem diameter increment (2.5 ± 0.2 mm). The PM group showed a slightly lower stem diameter increment (2.1 ± 0.2 mm), but this difference was not statistically significant compared to the control group. The PM + BC group had the smallest stem diameter increment (1.2 ± 0.2 mm), which was significantly lower than that of both the control and PM groups. The data suggest that the combination of PM and BC has a negative effect on stem diameter growth in Norway spruce compared with single PM or the control. In Norway spruce, a single PM treatment significantly reduced stem height growth compared to the control. Adding BC with PM appeared to counteract the negative effects of PM, resulting in growth levels comparable to those of the control group. Single PM inhibited growth, while PM + BC restored growth to the control levels. These findings indicated that PM negatively affected stem elongation; however, its adverse impact could be reduced by adding BC. However, the combined PM + BC treatment may still limit stem diameter increment.

Figure 1.

Mean (±SE) stem diameter increment (D increment, mm) of Norway spruce (A) and Norway maple (B) seedlings, and stem height increment (H increment, cm) of Norway spruce (C) and Norway maple (D) seedlings under different treatments (Control—no treatment, PM—exposure to particulate matter on foliage, and PM + BC—exposure to particulate matter on foliage and biochar to substrate). Statistically significant differences among the groups were determined by the Kruskal–Wallis H test and are shown by different letters a and b at p < 0.05.

The diameter of Norway maple seedlings did not respond to any of the treatments, while both PM and PM + BC significantly reduced stem height compared to the control group (Figure 1B,D). The stem diameter increment for the control, PM, and PM + BC treatments ranged from 2.8 to 3.0 mm per tree, with no significant differences among treatments. All treatments resulted in a similar range of seedling growth, and neither PM nor PM + BC had a significant impact on stem diameter increment compared to the control under the experimental conditions. The Norway maple control group had the highest stem height increment, at 35.9 ± 1.9 mm. This indicated that under unaffected conditions (without PM and BC), the seedlings showed the greatest height growth. The stem height increment was reduced under both PM and PM + BC treatments compared to the control. In this case, the combination of PM and BC did not mitigate the growth reduction caused by PM exposure.

3.2. Biochemical Responses

The concentrations of Chl a and Chl b in Norway spruce foliage did not change after the PM and PM + BC treatments over one vegetation season (Table 1). However, PM + BC slightly increased the Chl a/b ratio. Norway maple was more negatively affected by PM treatments compared to Norway spruce. In Norway maple foliage, PM treatment drastically reduced both Chl a and Chl b. The concentrations of Chl a and Chl b were 1.8–2.0 times lower after both treatments compared to the control group. BC partially mitigated the negative effect of PM on the Chl a/b ratio but did not restore pigment levels to those of the control.

Table 1.

Mean (±SE) concentration of chlorophyll a (Chl a), chlorophyll b (Chl b) and ratio Chl a/b in Norway spruce and Norway maple seedlings under different treatments. Statistically significant differences among the groups were determined by the Kruskal–Wallis H test and are shown by different letters a and b at p < 0.05.

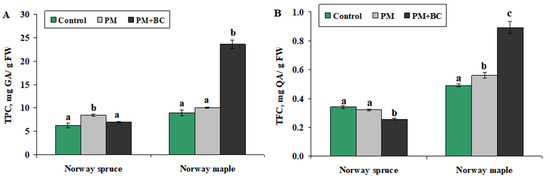

The PM treatment resulted in a 1.4-fold increase in TPC concentration in Norway spruce seedlings (Figure 2A). An increase to 9 mg GA/g FW was significant compared to the control. Still, no effect was found after the PM + BC treatment, i.e., the TPC decreased to approximately the control level (7 mg GA/g FW), with no significant difference from the control. The addition of BC counteracted the effect of PM, returning TPC to baseline levels. In the case of Norway maple, single PM treatment has no effect on TPC. The PM + BC treatment more than doubled the TPC compared to both control and PM treatments (Figure 2A). An increase of up to 24–25 mg GA/g FW was significantly higher than in the control and PM treatment.

Figure 2.

Mean (±SE) concentration of total polyphenol (TPC, (A)) and total flavonoid (TFC, (B)) in Norway spruce and Norway maple seedlings under different treatments (Control—no treatment, PM—exposure to particulate matter on foliage, and PM + BC—exposure to particulate matter on foliage and biochar to substrate). Statistically significant differences among the groups were determined by the Kruskal–Wallis H test and are shown by different letters a, b and c at p < 0.05.

The TFC patterns further confirmed species-specific stress responses (Figure 2B). In Norway spruce, a single PM treatment showed a TFC value (0.32 mg QA/g FW) similar to that of the control (0.33 mg QA/g FW); no significant difference was observed compared to the control. The TFC level was reduced by 1.3 times to 0.25 mg QA/g FW in the PM + BC treatment compared to the PM and control treatments. Meanwhile, in Norway maple, TFC increased slightly in the PM treatment to 0.55 mg QA/g FW, which was significantly higher than in the control (15%), and 1.8 times higher in the PM + BC treatment. In the PM + BC treatment, the value of 0.9 mg QA/g FW was significantly higher than that observed in the control and PM treatment. Our findings demonstrate that single PM moderately increased TFC levels. The combination of PM and BC significantly increased TFC, resulting in the highest value among all treatments. Norway maple responded positively to PM + BC, whereas Norway spruce remained unaffected or was negatively influenced by BC treatment.

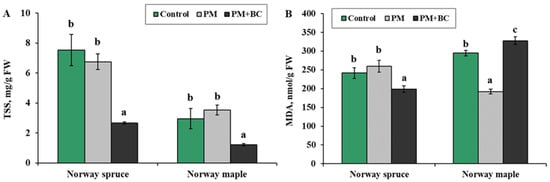

The TSS concentrations after the PM and PM + BC treatments responded similarly for both species, with a significant decrease in TSS after the PM + BC treatment (Figure 3A). In Norway spruce, the highest TSS value (8 mg/g FW) was observed in the control group. PM treatment showed a slightly lower value than the control (7 mg/g FW), but the difference was not significant. PM + BC treatment significantly reduced the TSS value (2 mg/g FW), showing a significant decrease compared to the other treatments. In Norway maple, control and PM had similar TSS levels (3–4 mg/g FW). PM + BC decreased significantly to around 1 mg/g FW, mirroring the trend in Norway spruce. Across both species, PM + BC reduced TSS concentration more than other treatments. Statistical analysis indicated a significant difference in the PM + BC treatment, whereas no significant difference was observed between the control and PM groups.

Figure 3.

Mean (±SE) concentration of total soluble sugars (TSS, (A)) and malondialdehyde (MDA, (B)) in Norway spruce and Norway maple seedlings under different treatments (Control—no treatment, PM—exposure to particulate matter on foliage, and PM + BC—exposure to particulate matter on foliage and biochar to substrate). Statistically significant differences among the groups were determined by the Kruskal–Wallis H test and are shown by different letters a, b and c at p ≤ 0.05.

As measured by MDA, lipid peroxidation patterns revealed contrasting oxidative stress responses (Figure 3B). In Norway spruce, both the control and PM treatments have relatively similar MDA levels (250–270 nmol/g FW). The PM + BC treatment showed a significant reduction in MDA levels (200 nmol/g FW), indicating a statistically significant decrease compared to the other two groups (a difference of 1.2 times from the control group). In Norway maple, control and PM + BC treatments showed trends opposite those in Norway spruce, resulting in the highest MDA content (350 nmol/g FW). Conversely, in Norway maple, single PM treatment reduced MDA levels by 1.5 times, while PM + BC led to an increase.

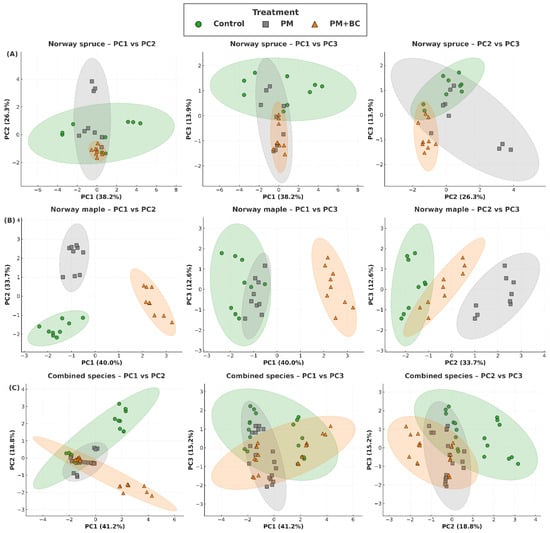

3.3. Multivariate Biochemical Responses to Treatments

PCA was performed to assess how different treatments influence pigment composition and antioxidant activity in Norway maple and Norway spruce, and to visualize overall physiological differentiation between the two species. Figure 4 presents PCA biplots with 95% confidence ellipses comparing the two species across the three treatments (Control, PM, and PM + BC). Across all projections (PC1–PC2, PC1–PC3, and PC2–PC3), distinct clustering patterns were evident, indicating that both PM exposure and BC amendment produced measurable and consistent shifts in multivariate biochemical profiles. In Norway spruce (Figure 4A), PM-treated seedlings were separated from the Control group along PC1 in all projections, reflecting coordinated declines in chlorophyll pigments (Chl a, Chl b, and Car) and increases in oxidative stress indicators, particularly MDA (Supplementary Table S1). The displacement of PM seedlings along PC3 further indicated adjustments in secondary metabolites, including TPC and TFC. In contrast, seedlings grown in the PM + BC treatment occupied an intermediate position between the Control and PM clusters. This demonstrates that BC mitigated the adverse biochemical effects of PM, partially restoring pigment levels and moderating oxidative and phenolic responses. The tighter ellipses for PM + BC, relative to PM alone, also indicated greater biochemical stability when BC was present.

Figure 4.

Two-dimensional PCA projections of biochemical responses of Norway spruce (A), Norway maple (B), and combined species (C) seedlings under different treatments (Control—no treatment, PM—exposure to particulate matter on foliage, and PM + BC—exposure to particulate matter on foliage and biochar to substrate). Each panel shows three biplot projections (PC1–PC2, PC1–PC3, PC2–PC3) based on the first three principal components. Control, PM, and PM + BC treatments form distinct clusters, as indicated by 95% confidence ellipses. Axes indicate the percentage of variance explained.

A similar but more pronounced pattern was observed for Norway maple (Figure 4B). Norway maple seedlings exposed to PM showed substantial separation from the Control group along both PC1 and PC2, driven by strong increases in MDA and marked pigment degradation (Supplementary Table S1). Norway maple also showed a more pronounced shift along PC3 than Norway spruce, indicating elevated production of TPC and TFC compounds. As in Norway spruce, the PM + BC treatment moderated PM-induced shifts, with samples clustering closer to the Control across all PCA planes. The overlap of confidence ellipses between PM + BC and Control groups demonstrated that BC effectively reduced oxidative stress and stabilized pigment composition in Norway maple seedlings.

The combined species PCA (Figure 4C) further clarified interspecific differences and treatment effects. Norway spruce and Norway maple formed two well-separated clusters across PC1–PC2 and PC1–PC3, confirming inherent species-level variability in pigment composition, antioxidant capacity, and secondary metabolite profiles. Despite these baseline differences, the direction of treatment-related shifts was highly consistent between species: PM exposure displaced samples away from Controls, while PM + BC reduced this displacement. The consistent geometry of the ellipses across species and PCA projections highlights that the biochemical response to PM and the mitigating influence of BC operated along similar multivariate axes in both tree species.

4. Discussion

When assessing the stem responses of two species, we found that Norway spruce and Norway maple showed distinct growth reactions to PM and BC treatments, highlighting species-specific sensitivity to these amendments. In Norway spruce, PM alone reduced stem height but not diameter, whereas the combined PM + BC treatment significantly decreased stem diameter while mitigating the negative effect of PM on height growth. This could be explained by the fact that height restoration suggests BC alleviated nutrient/water stress, which is critical for stem elongation, but the substrate mix with 10% BC might have caused short-term structural/aeration issues or a nutrient imbalance that limited diameter growth. For Norway maple, stem diameter remained unaffected by any treatment; however, both PM and PM + BC significantly reduced stem height, with BC failing to counteract the adverse effect of PM. The final aspect could be related to chlorophyll reduction, as the lack of photosynthetic recovery limited seedling growth, overriding any BC soil benefit. The obtained results suggest a partial mitigation effect of BC on height growth, though stem diameter may remain sensitive to soil-based factors. Comparable reductions in growth under PM exposure were observed in conifers, due to reduced photosynthetic efficiency and altered resource allocation []. In contrast, Norway maple seedlings showed no early changes in stem diameter across treatments. The significant reduction in tree seedling height observed under both PM and PM + BC treatments may be attributed to PM sensitivity, which induces changes in seedling morphology through multiple functional pathways [,]. In general, He et al. [] stated that the influence of BC on plant growth can vary, as many factors influence their response. Although we did not have the opportunity to observe it, for instance, the application of BC alone to soil has been shown to increase the height of Malus hupehensis Rehd. seedlings [].

To assess the biochemical response of the seedlings, we analyzed Chl a, Chl b and Car as indicators of photosynthetic performance, together with TFC, TPC, MDA, and TSS as markers of stress tolerance and metabolic activity. Despite photosynthetic pigments being recognized as sensitive indicators of environmental stress [], in our study, chlorophyll content in Norway spruce remained relatively unaffected by the treatments. This species, with narrow, waxy needles, maintained stable chlorophyll levels under PM exposure. The specific structure of spruce foliage could have prevented PM from penetrating and, therefore, minimised internal damage, acting as a tolerance mechanism. However, a decline in chlorophyll content in treated Norway maple seedlings indicated potentially impaired photosynthesis and pigment degradation, as observed in the previous studies under oxidative stress [,,,]. Its broad, relatively soft leaves offer a larger area for PM deposition, and particles can more easily block stomata. As PM builds up, stomatal closure and stress on internal tissues lead to chlorophyll breakdown and reduced photosynthesis. Importantly, the decrease in Chl is linked to changes in plant growth. Although Antonangelo et al. [] demonstrated chlorophyll enhancement in tree tissues from a single BC treatment, our study focused on the combined effects of PM and BC, making direct comparison impossible. The Chl a/b, which reflects the balance between photosynthetic pigments and serves as an indicator of leaf shading and plant stress tolerance across species [,], decreased in Norway maple following exposure to PM. The Chl a/b ratio was also observed to decline in the study by Javanmard et al. [], with higher soil dust levels. In our study, both species showed a higher Chl a/b ratio in the BC + PM treatment, which was significantly higher in Norway spruce seedlings compared to the control group.

Our study found that the PM treatment significantly increased TPC in Norway spruce seedlings compared with the control, an effect that was counteracted by the addition of BC. However, in Norway maple, TPC remained unchanged under PM but more than doubled under the PM + BC treatment relative to both the control and PM groups. These results demonstrated that antioxidant responses varied across the species studied and the treatments applied. The increased TPC in Norway spruce following PM exposure potentially indicated the activation of antioxidant defence mechanisms []. However, the addition of BC to the substrate mitigated this effect. PM + BC significantly increased the TPC level in Norway maple, whereas PM alone had no effect. A synergistic induction of phenolic biosynthesis may explain the significantly increased TPC levels in Norway maple seedlings following the combination of PM treatment and BC addition. Therefore, this may be related to BC’s ability to alter microbial communities or soil chemistry, indirectly triggering plant defence pathways [,]. The TFC patterns further confirmed species-specific stress responses. Overall, the PM + BC treatment significantly enhanced TFC in Norway maple but reduced it in Norway spruce. We found that BC may enhance secondary metabolism in deciduous species more effectively than conifers, potentially by modulating nutrient availability or signalling compounds []. In both species, TSS concentrations responded similarly, with a significant reduction following the PM + BC treatment. The treatment effect obtained may reflect increased energy demands or altered carbon allocation under combined stress conditions. Previous studies have linked TSS depletion to oxidative stress and impaired carbohydrate metabolism in BC-amended, polluted soils []. Furthermore, under stress conditions, TSS can serve as precursors in phenolic metabolism, whereby seedlings may increasingly allocate TSS to defense processes, leading to a decline in TSS content.

Our findings showed that the effect of PM + BC on MDA levels was species-specific: in Norway spruce, the BC amendment mitigated oxidative stress, as evidenced by reduced MDA levels, whereas in Norway maple, the BC increased oxidative stress, resulting in elevated MDA levels. When examining TPC, TFC, and MDA together, we found that BC enhanced the defensive metabolism of Norway maple (higher TPC and TFC), but this was still insufficient to prevent oxidative damage (higher MDA). This indicates that the combined PM and BC treatment likely exceeded the seedlings’ metabolic capacity. A more complex or delayed oxidative response could be potentially driven by shifts in metabolic balance or interactions with BC-derived compounds []. Other studies have demonstrated that BC can reduce phenolic acid concentrations in the rhizosphere via sorption mechanisms, thereby lowering oxidative stress indicators such as MDA and enhancing plant metabolic stability. For instance, Wang et al. [] demonstrated that applying BC to Malus hupehensis seedlings significantly reduced lipid peroxidation levels, thereby improving photosynthetic performance. Additionally, the study demonstrated that BC enhanced antioxidant defences and mitigated oxidative stress by reducing phenolic acid concentrations. Similarly, Speratti et al. [] reported an increase in chlorophyll content under BC treatment. The findings are consistent with the observed patterns in our study, in which chlorophyll and phenolic content increased in Norway maple seedlings treated with the combined PM + BC compared with the single PM treatment. The enhancement of secondary metabolites, such as TPC and TFC, may be attributed to BC-induced changes in soil microbial communities or nutrient dynamics []. In contrast, Norway spruce showed a more limited physiological response, suggesting that BC effectiveness is species-specific.

The PCA revealed that PM exposure caused significant physiological disruptions in both Norway spruce and Norway maple seedlings, including strong pigment depletion, elevated oxidative stress, and increased production of TPC and TFC compounds. These responses align with well-established effects of PM deposition on foliage, in which PM commonly reduces chlorophyll content and increases lipid peroxidation and antioxidant activity [,]. Our study showed that BC amendment consistently moderated these effects, reducing the magnitude of PM-induced biochemical shifts and shifting the multivariate profiles of PM + BC seedlings closer to those of the Control group. According to the current results, earlier studies have shown that BC application can reduce oxidative stress and stabilize pigment systems in plants facing abiotic stress. This effect is achieved through BC ability to improve soil quality, nutrient availability, and overall plant health [,,,,,].

Although both species benefited from the BC amendment, they differed in the intensity and structure of their responses. Norway maple showed greater biochemical plasticity and stronger oxidative and secondary metabolite responses, whereas Norway spruce displayed a more conservative adjustment characterized by pigment loss and moderate antioxidant activation. Such species-specific differences in physiological sensitivity to air pollution are widely reported, reflecting distinct leaf morphologies, cuticular properties, and inherent antioxidant capacities []. The uncertainties identified indicate that the positive effects observed in this study, such as reduced oxidative stress, altered TPC and TFC, and species-specific physiological changes, should be interpreted with caution.

Moreover, Kozioł et al. [] highlighted that the beneficial effects of BC vary depending on the tree species, type of BC, and soil characteristics. The functional BC capacity in soil depends on the type of feedstock (agricultural residues, energy crops, etc.) used and the conditions under which it was produced [,]. Furthermore, BC is a long-lasting soil amendment that can persist for decades [,], thereby improving aeration, moisture retention, and nutrient availability in urban tree pits, which enhances tree growth and stress tolerance []. Its stability also supports long-term carbon sequestration by reducing CO2 emissions and enhancing key soil properties, such as water retention and cation exchange capacity []. While our study demonstrated that BC could influence the early physiological responses of Norway spruce and Norway maple seedlings under PM exposure, it is essential to recognize that the properties and effectiveness of BC are highly variable. Abiotic processes, such as oxidation and hydrolysis, may further reduce its long-term impact.

These species-specific patterns have important implications for maintaining urban ecosystem services. In Norway spruce, BC appears to enhance tolerance to PM pollution, whereas in Norway maple, BC should be applied cautiously, as it may intensify physiological stress in this widely used urban tree. Future experiments should focus on optimising BC type and application rate, as the 10% used here may have contributed to the lack of positive responses in Norway maple, possibly due to pH change or nutrient immobilisation. Furthermore, using young seedlings may not fully reflect the long-term resilience of mature trees to foliar PM exposure or to soil reclamation, and the relatively short assessment period limits understanding of the cumulative effects of pollution.

5. Conclusions

The growth and physiological responses of Norway spruce and Norway maple to different PM and BC treatments were different. PM impaired seedling growth via species-specific pathways. PM reduced height growth in both species, while Norway spruce also showed reduced diameter growth when treated with PM + BC, while diameter growth in Norway maple remained unchanged. Norway maple showed reduced chlorophyll and strongly oxidative and phenolic responses when treated with PM. However, Norway spruce showed milder pigment changes but significant changes in secondary metabolites. Biochar reduced PM-induced stress in Norway spruce by restoring height growth, normalizing phenolic content, stabilizing pigments, and reducing oxidative stress. However, the effects of BC on Norway maple were rather mixed, as it failed to restore chlorophyll while increasing oxidative stress and enhancing the production of phenolic and flavonoid compounds. PCA provided a holistic, multivariate validation of the findings, moving beyond single-parameter interpretations. It clearly showed that PM exposure shifts the plant’s physiological state away from homeostasis, while BC acts as a moderating influence on this shift. Consequently, the multivariate pattern supports the hypothesis that BC enhances physiological stability under stress, even when individual parameters, such as increased MDA in Norway maple, appear negative.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su172310697/s1, Table S1: Principal component loadings (PC1–PC3) for biochemical variables in Norway spruce (Picea abies), Norway maple (Acer platanoides), and the combined species dataset. Loadings are given separately for the PCA models corresponding to Figure 4A (Norway spruce), Figure 4B (Norway maple), and Figure 4C (combined). Positive and negative values indicate the direction and magnitude of each variable’s contribution to the respective principal component. These loadings were used to interpret treatment-related biochemical patterns across Control, PM, and PM + BC groups.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.V.-K., M.M. and V.Č.; Formal analysis, I.V.-K., M.M., V.Č., V.S., M.V., G.Č.-M. and A.O.; Investigation, I.V.-K., M.M. and V.Č.; Methodology, I.V.-K., M.M. and V.Č.; Software, I.V.-K. and V.Č.; Validation, I.V.-K.; Writing—original draft, I.V.-K., M.M. and V.Č.; Writing—review & editing, V.S., M.V., G.Č.-M. and A.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This study was carried out under the Long-Term Research Programme ‘Sustainable Forestry and Global Changes’ at the Lithuanian Research Centre for Agriculture and Forestry (LAMMC). This study partly includes experimental data generated under the PhD project of Valentinas Černiauskas. We thank Ieva Čėsnienė (LAMMC) for assistance with analyses, and Audrius Kabašinskas (KTU, Lithuania) for statistical consultations.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- World Health Organization. WHO Global Air Quality Guidelines: Particulate Matter (PM2.5 and PM10), Ozone, Nitrogen Dioxide, Sulfur Dioxide and Carbon Monoxide; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; p. 273. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240034228 (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Nowak, J.M.; Cantrell, K.B.; Watts, D.W.; Busscher, W.J.; Johnson, M.G. Designing relevant biochars as soil amendments using lignocellulosic-based and manure-based feedstocks. J. Soils Sediments 2014, 14, 330–343. [Google Scholar]

- Paull, N.J.; Krix, D.; Irga, P.J.; Torpy, F.R. Green wall plant tolerance to ambient urban air pollution. Urban For. Urban Green 2021, 63, 127201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popek, R.; Gawrońska, H.; Wrochna, M.; Gawroński, S.W.; Sæbø, A. Particulate matter on foliage of 13 woody species: Deposition on surfaces and phytostabilisation in waxes—A 3-year study. Int. J. Phytoremediat. 2013, 15, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Przybysz, A.; Sæbø, A.; Hanslin, H.M.; Gawroński, S.W. Accumulation of particulate matter and trace elements on vegetation as affected by pollution level, rainfall and the passage of time. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 481, 360–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, P.K. Impacts of particulate matter pollution on plants: Implications for environmental biomonitoring. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2016, 129, 120–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccolo, E.L.; Becagli, M.; Lauria, G.; Cantini, V.; Ceccanti, C.; Cardelli, R.; Massai, R.; Remorini, D.; Guidi, L.; Landi, M. Biochar as a soil amendment in the tree establishment phase: What are the consequences for tree physiology, soil quality and carbon sequestration? Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 844, 157175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, G.W.; Iborra, S.; Corma, A. Synthesis of transportation fuels from biomass: Chemistry, catalysts, and engineering. Chem. Rev. 2006, 106, 4044–4098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biederman, L.A.; Harpole, W.S. Biochar and its effects on plant productivity and nutrient cycling: A meta-analysis. GCB Bioenergy 2013, 5, 202–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.P.S.; Bhandari, S.; Bhatta, D.; Poudel, A.; Bhattarai, S.; Yadav, P.; Ghimire, N.; Paudel, P.; Paudel, P.; Shrestha, J.; et al. Biochar application: A sustainable approach to improve soil health. J. Agric. Food Res. 2023, 11, 100498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozioł, A.; Paliwoda, D.; Mikiciuk, G.; Benhadji, N. Biochar as a multi-action substance used to improve soil properties in horticultural and agricultural crops—A review. Agriculture 2024, 14, 2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Canqui, H. Biochar and soil physical properties. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2017, 81, 687–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharenbroch, B.C.; Meza, E.N.; Catania, M.; Fite, K. Biochar and biosolids increase tree growth and improve soil quality for urban landscapes. J. Environ. Qual. 2013, 42, 1372–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bong, C.P.C.; Lim, L.Y.; Lee, C.T.; Ong, P.Y.; VanFan, Y.; Klemeš, J.J. Integrating compost and biochar towards sustainable soil management. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2021, 86, 1345–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaffert, E.; Lukac, M.; Percival, G.; Rose, G. The influence of biochar soil amendment on tree growth and soil quality: A review for the arboricultural industry. Arboric. Urban For. 2022, 48, 176–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somerville, P.D.; Farrell, C.; May, P.B.; Livesley, S.J. Biochar and compost equally improve urban soil physical and biological properties and tree growth, with no added benefit in combination. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 706, 135736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumroese, R.K.; Heiskanen, J.; Englund, K.; Tervahauta, A. Pelleted biochar: Chemical and physical properties show potential use as a substrate in container nurseries. Biomass Bioenergy 2011, 35, 2018–2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemati, M.R.; Simard, F.; Fortin, J.P.; Beaudoin, J. Potential use of biochar in growing media. Vadose Zone J. 2015, 14, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.J.; Hyun, J.; Yoo, S.Y.; Yoo, G. The role of biochar in alleviating soil drought stress in urban roadside greenery. Geoderma 2021, 404, 115223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, I.A.; Dearborn, V.K.; Hutyra, L.R. Live fast, die young: Accelerated growth, mortality, and turnover in street trees. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0215846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ennis, C.J.; Evans, A.G.; Islam, M.; Ralebitso-Senior, T.K.; Senior, E. Biochar: Carbon sequestration, land remediation, and impacts on soil microbiology. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 42, 2311–2364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzyżaniak, M.; Świerk, D.; Walerzak, M.; Urbański, P. The impact of urban conditions on different tree species in public green areas in the city of Poznan. Folia Hortic. 2015, 27, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzyżaniak, M.; Świerk, D.; Szczepańska, M.; Urbański, P. Changes in the area of urban green space in cities of western Poland. Bulletin of Geography. Socio-Econ. Ser. 2018, 39, 65–77. [Google Scholar]

- Sæbø, A.; Popek, R.; Nawrot, B.; Hanslin, H.M.; Gawronska, H.; Gawronski, S.W. Plant species differences in particulate matter accumulation on leaf surfaces. Sci. Total Environ. 2012, 427, 347–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fedorchak, E.R.; Savosko, V.M.; Krasova, O.O.; Komarova, I.O.; Yevtushenko, E.O. Ecological adaptations among spruce species along an environmental gradient in urban areas. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2023, 1254, 012114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 13322-1; The Standard for Particle Size Analysis. Image Analysis Methods—Static Image Analysis Methods. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014; p. 24.

- Aung, A.; Han, S.H.; Youn, W.B.; Meng, L.; Cho, M.S.; Park, B.B. Biochar effects on the seedling quality of Quercus serrata and Prunus sargentii in a containerized production system. For. Sci. Technol. 2018, 14, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köster, E.; Pumpanen, J.; Palviainen, M.; Zhou, X.; Köster, K. Effect of biochar amendment on the properties of growing media and growth of containerized Norway spruce, Scots pine, and silver birch seedlings. Can. J. For. Res. 2021, 51, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beniušytė, E.; Čėsnienė, I.; Sirgedaitė-Šėžienė, V.; Vaitiekūnaitė, D. Genotype-dependent jasmonic acid effect on Pinus sylvestris L. growth and induced systemic resistance indicators. Plants 2023, 12, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Černiauskas, V.; Varnagirytė-Kabašinskienė, I.; Čėsnienė, I.; Armoška, E.; Araminienė, V. Response of tree seedlings to a combined treatment of particulate matter, ground-level ozone, and carbon dioxide: Primary effects. Plants 2025, 14, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirgedaitė-Šėžienė, V.; Vaitiekūnaitė, D.; Šilanskienė, M.; Čėsnienė, I.; Striganavičiūtė, G.; Jaeger, A. Assessing the phytotoxic effects of class A foam application on northern Europe tree species: A short-term study on implications for wildfire management and ecosystem health. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 166, 112393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grantz, D.A.; Garner, J.H.B.; Johnson, D.W. Ecological effects of particulate matter. Environ. Int. 2003, 29, 213–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Yao, Y.; Ji, Y.; Deng, J.; Zhou, G.; Liu, R.; Shao, J.; Zhou, L.; Li, N.; Zhou, X.; et al. Biochar amendment boosts photosynthesis and biomass in C3 but not C4 plants: A global synthesis. GCB Bioenergy 2020, 12, 605–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Pana, F.; Wang, G.; Zhang, G.; Wang, Y.; Chena, X.; Mao, Z. Effects of biochar on photosynthesis and antioxidative system of Malus hupehensis Rehd. seedlings under replant conditions. Sci. Hortic. 2014, 175, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kováts, N.; Hubai, K.; Diósi, D.; Sainnokhoi, T.A.; Hoffer, A.; Tóth, Á.; Teke, G. Sensitivity of typical European roadside plants to atmospheric particulate matter. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 124, 107428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speratti, A.B.; Johnson, M.S.; Sousa, H.M.; Dalmagro, H.J.; Couto, E.G. Biochars from local agricultural waste residues contribute to soil quality and plant growth in a Cerrado region (Brazil) Arenosol. Glob. Change Biol. Bioenergy 2018, 10, 272–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javanmard, Z.; Tabari Kouchaksaraei, M.; Bahrami, H.A.; Hosseini, S.M.; Modarres Sanavi, S.A.M.; Struve, D.; Ammere, C. Soil dust effects on morphological, physiological and biochemical responses of four tree species of semiarid regions. Eur. J. For. Res. 2020, 139, 333–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaturvedi, R.K.; Prasad, S.; Rana, S.; Obaidullah, S.M.; Pandey, V.; Singh, H. Effect of dust load on the leaf attributes of the tree species growing along the roadside. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2013, 185, 383–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonangelo, J.A.; Sun, X.; Eufrade-Junior, H.D.J. Biochar impact on soil health and tree-based crops: A review. Biochar 2025, 7, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hariram, M.; Sahu, R.; Elumalai, S.P. Impact assessment of atmospheric dust on foliage pigments and pollution resistances of plants grown nearby coal based thermal power plants. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2018, 74, 56–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maletsika, P.A.; Nanos, G.D.; Stavroulakis, G.G. Peach leaf responses to soil and cement dust pollution. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22, 15952–15960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Li, T.; Yang, M.; Zhou, X.; Peng, C. The effects of environmental factors and plant diversity on forest carbon sequestration vary between eastern and western regions of China. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 437, 140371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayaz, M.; Feizienė, D.; Tilvikienė, V.; Akhtar, K.; Stulpinaitė, U.; Iqbal, R. Biochar role in the sustainability of agriculture and environment. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somerville, P.D.; Farrell, C.; May, P.B.; Livesley, S.J. Tree water use strategies and soil type determine growth responses to biochar and compost organic amendments. Soil Tillage Res. 2019, 192, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blok, C.; Regelink, I.C.; Hofland-Zijlstra, J.D.; Streminska, M.A.; Eveleens-Clark, B.A.; Bolhuis, P.R. Perspectives for the Use of Biochar in Horticulture; Wageningen UR Greenhouse Horticulture: Bleiswijk, The Netherlands, 2016; Report GTB-1388; Available online: https://edepot.wur.nl/370956 (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Singh, H.; Singh, P.; Agrawal, S.B.; Agrawal, M. Implications of foliar particulate matter deposition on the physiology and nutrient allocation of dominant perennial species of the Indo-Gangetic Plains. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 939950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, H.P.; Kammann, C.; Hagemann, N.; Leifeld, J.; Bucheli, T.D.; Sánchez Monedero, M.A.; Cayuela, M.L. Biochar in agriculture—A systematic review of 26 global meta-analyses. GCB Bioenergy 2021, 13, 1708–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Wu, K.C.; Deng, Z.N.; Huang, C.M.; Verma, K.K.; Pang, T.; Huang, H.R. Biochar and its impact on soil profile and plant development. J. Plant Interact. 2024, 19, 2401356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sgrigna, G.; Baldacchini, C.; Dreveck, S.; Cheng, Z.; Calfapietra, C. Relationships between air particulate matter capture efficiency and leaf traits in twelve tree species from an Italian urban-industrial environment. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 718, 137310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Tang, M.; Huang, X.; Wang, L.; Liu, Q.; Lu, S. An efficient biochar adsorbent for CO2 capture: Combined experimental and theoretical study on the promotion mechanism of N-doping. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 466, 143095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.K.; Sachan, K.; Ranjitha, G.; Chandana, S.; Manoj, B.P.; Panotra, N.; Katiyar, D. Building soil health and fertility through organic amendments and practices: A review. Asian J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2024, 10, 175–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laird, D.A.; Fleming, P.; Davis, D.D.; Horton, R.; Wang, B.; Karlen, D.L. Impact of biochar amendments on the quality of a typical Midwestern agricultural soil. Geoderma 2010, 158, 443–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, J.; Joseph, S. Biochar for environmental management: An introduction. In Biochar for Environmental Management; Lehmann, J., Joseph, S., Eds.; Earthscan: London, UK, 2015; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Keiluweit, M.; Nico, P.S.; Johnson, M.G.; Kleber, M. Dynamic molecular structure of plant biomass-derived black carbon (biochar). Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 1247–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).