Abstract

This paper investigates the integration of proximity theory (PT) into the management of public transport service disruptions within sustainable Mobility-as-a-Service (MaaS) systems, an area that is largely underexplored. PT provides a multidimensional framework for analyzing relationships and interactions within complex systems, encompassing five dimensions: geographical, cognitive, institutional, organizational, and social, each influencing coordination, learning, and adaptability. Building on this framework, the study introduces temporal proximity as an original sub-dimension of geographical proximity, forming a spatial–temporal proximity theory (PTST), which highlights the critical role of timing, synchronization, and coordinated responses in transport disruption management. To operationalize these principles, a mixed-integer programming (MIP) model was developed to optimize traveler assignments across 50 routes for 10 travelers, minimizing delays, transfers, walking distance, crowding, and CO2 emissions. Two scenarios were analyzed: one without environmental considerations and another with CO2 penalties. Results show that emissions were reduced by up to 50% for certain routes, while maintaining feasible travel times and route choices. The case study demonstrates that PTST can be operationalized as a practical tool, bridging mobility resilience and environmental responsibility, and providing actionable insights for sustainable and intelligent MaaS platforms.

1. Introduction

Urban mobility is becoming increasingly complex as cities grow larger, denser, and more interconnected. Rapid urbanization, population growth, and economic development have increased the demand for efficient transportation systems, resulting in a multifaceted mobility landscape that includes public transit, private vehicles, ride-sharing, cycling, and pedestrian movement. While these options improve accessibility and reduce congestion, they also introduce logistical, infrastructural, and environmental challenges [] making coordination, equitable access, and sustainability major concerns for urban planners and policymakers []. Moreover, sustainable transport planning may be a crucial role in sustainable city branding, as the quality, efficiency, and innovation of a city’s transportation system can influence its identity, attractiveness to tourists and investors, and overall reputation on a global scale [].

Urban transport systems are highly interdependent, so failures in one area, such as a subway breakdown, road accident, or extreme weather event, can affect the entire network. Aging infrastructure, limited redundancy, cyber threats, and climate change exacerbate fragility, causing significant social and economic consequences, particularly for communities reliant on public transport. Ensuring the resilience and adaptability of urban mobility is therefore essential. Public transport, including buses, trains, metros, trams, light rail, and ferries, plays a central role in urban functioning, supporting economic activity, social inclusion, and environmental sustainability [] whose impacts are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Public transport positive impacts [].

Despite these benefits, public transport frequently experiences service disruptions, such as delays, cancelations, overcrowding, and lack of real-time information, that negatively affect users. For instance, the October 2024 floods in Valencia, Spain, shut down the Metrovalencia system, while an energy infrastructure failure in April 2025 disrupted rail and metro services across Portugal and Spain. These events highlight the operational vulnerabilities of urban mobility systems and the need for resilient, user-centered disruption management approaches. Traditional disruption management tools, such as standard operating procedures, redundancy systems, emergency response plans, and manual schedule adjustments, are effective to some extent [,,] but are often insufficient in increasingly complex and dynamic environments.

Advanced technological solutions, including real-time monitoring, predictive analytics, and AI-based tools, are increasingly adopted to improve adaptability and response efficiency. MaaS platforms integrate multiple transport modes through digital interfaces, offering seamless, flexible, and personalized travel experiences []. Real-time information allows travelers to adjust routes during delays or congestion, while predictive analytics and AI extend this capability by analyzing patterns in traffic, weather, events, and transport services to anticipate potential disruptions []. Integrated payment solutions encourage public and shared transport usage, reducing reliance on private vehicles []. Building on this, integrated infrastructure management complements MaaS by leveraging digital platforms connected to smart traffic lights, sensors, and IoT systems to automatically adjust traffic flow and reroute vehicles during incidents, minimizing delays []. However, while these advanced technological solutions offer powerful tools to reduce travel disruptions, they also face several challenges. One major concern is data privacy, as the collection of detailed travel patterns and personal preferences raises questions about security and how this information is used []. While MaaS provides operational flexibility, understanding the coordination and timing challenges inherent in complex transport networks, requires a theoretical background, such as Proximity Theory (PT). PT provides a multidimensional framework for analyzing relationships and interactions within complex systems. Reference [] identifies five dimensions—geographical, temporal, cognitive, organizational, and social—each influencing coordination, learning, and adaptability. In the context of transport disruptions, the geographical and temporal dimensions are particularly critical, as they affect both spatial accessibility and time-sensitive flows. By focusing on these two dimensions, a spatial–temporal proximity theory (PTST) can guide travel decisions and operational responses, considering both physical distance and timing, and enhancing coordination among passengers, operators, and planners.

Existing research has examined Mobility as a Service (MaaS) for improving travel efficiency. However, few studies have investigated how integrating Proximity Theory (PT) into MaaS can enhance the management of public transport service disruptions, a critical gap that this paper aims to address. Moreover, the concept of sustainable MaaS is emerging, and there is a pressing need for tools that operationalize its principles. This paper addresses these gaps by developing a mixed-integer programming model that operationalizes PTST principles within MaaS, incorporating an environmental perspective to support low-carbon transport during disruption services. This model optimizes traveler assignment to feasible routes while accounting for spatial–temporal proximities and delay penalties, representing the paper’s key novelty in operationalizing theory into a validated decision-making tool.

This study is guided by the following research questions:

RQ1.

How can the dimensions of Proximity Theory be integrated into sustainable MaaS to strengthen resilience during public transport disruptions?

RQ2.

To what extent does this integration enhance user satisfaction, trust, and system adaptability in response to service disruptions?

RQ3.

How can PTST be operationalized within sustainable MaaS through a mathematical model to optimize traveler assignment and decision-making during public transport service disruptions?

This paper is structured as follows. Section 2 describes the methodology adopted for the research. Section 3 presents the literature review, beginning with an overview of proximity theory, followed by its connections to Mobility-as-a-Service (MaaS), the impacts and management of public transport disruptions, and a review of mathematical models for transport network optimization. With this background, Section 4 develops an integrated approach by applying proximity theory to sustainable MaaS for managing service disruptions, which provides the basis for Section 5. This section introduces the mixed-integer programming model as a practical implementation of PTST, a model that assigns travelers to feasible routes while accounting for delay penalties. Subsequently, Section 6 illustrates the applicability of the model through a case-study followed by Section 7, which discusses research gaps and outlines future directions. Finally, Section 8 concludes the paper by summarizing the key findings and contributions.

2. Research Methodology

This research employs a theory-building and model-development methodology to explore the integration of PTST into the management of public transport service disruptions within sustainable MaaS. Given the exploratory and interdisciplinary nature of the research problem, an initial conceptual and synthesis-oriented approach was used to construct a framework capturing the multidimensionality of PT and its relevance for disruption management, resilience, and environmental sustainability. The methodology unfolds in several stages, as described.

Step 1—Literature review: A systematic review of peer-reviewed journals and reports was conducted to identify key concepts related to PT, MaaS, urban mobility disruptions, and sustainable transport planning. Scopus and Web of Science databases were searched using keywords including: (“proximity theory”) AND (“Mobility-as-a-Service” OR “MaaS”) AND (“transport disruptions”) AND (“resilience”) AND (“sustainability” OR “CO2 emissions”). The inclusion criteria prioritized publications from the last 10 years (54 documents, approximately of 60%), with an emphasis on interdisciplinary studies bridging transport planning, systems theory, and sustainability.

Step 2—Thematic analysis: Extracted sources were analyzed through thematic coding to identify recurring concepts across the five PT dimensions: geographical, cognitive, institutional, organizational, and social. Particular attention was given to temporal coordination, which was operationalized as a sub-dimension of geographical proximity. These thematic clusters informed the design of the conceptual framework and the modeling approach, highlighting how proximity dimensions influence collaboration, learning, and adaptability in MaaS disruption management.

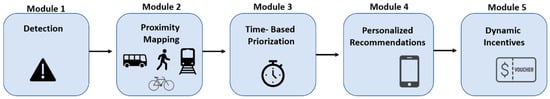

Step 3—Framework development: The insights from the literature and thematic analysis were translated into a conceptual framework for managing urban mobility disruptions within MaaS systems. The framework integrates spatial–temporal proximities to guide real-time decision-making, route prioritization, and stakeholder coordination. Its five key modules: detection, proximity mapping, time-based prioritization, personalized recommendations, and dynamic incentives, provide a systematic approach to balancing efficiency, user convenience, and sustainability during service disruptions.

Step 4—Model operationalization: To operationalize the framework, a mixed-integer programming (MIP) model was developed to optimize traveler assignments across feasible routes while simultaneously minimizing delays, transfers, walking distance, crowding, and environmental impacts such as CO2 emissions. A case study was used to test two scenarios: one considering operational efficiency only, and another including an additional penalty term for CO2 emissions.

Step 5—Validation and application: While the model has been validated through simulation scenarios, future research should extend its application to larger-scale networks and real-world MaaS deployments. This will allow empirical testing of how spatial–temporal proximities influence traveler behavior, stakeholder coordination, and system-level resilience under diverse disruption scenarios.

By following this methodology, this research provides a stepwise, integrative approach that combines conceptual insights from PT with quantitative optimization, offering actionable guidance for the design of sustainable, intelligent MaaS platforms.

3. Literature Review

3.1. Mobility-as-a-Service (MaaS)

The concept of Mobility as a Service (MaaS) was first proposed by Heikkilä [] as “a system in which a comprehensive range of mobility services are provided to customers by mobility operators”. Initially, MaaS was conceived as a user-centric paradigm [], aiming to integrate heterogeneous transport services into a single digital interface. This early vision prioritized convenience by enabling users to plan, book, and pay for multimodal journeys, combining public transit, ride-hailing, bike-sharing, car rentals, and other options, within one seamless platform [].

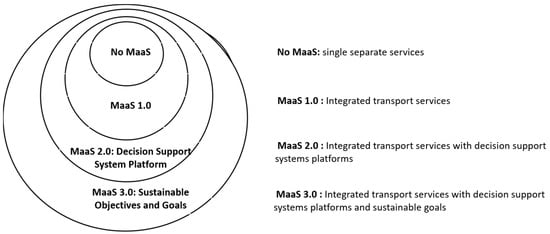

Over time, MaaS has evolved beyond this functional integration. More recent iterations incorporate decision support systems (DSS) to improve travel optimization and personalization, while also aligning with broader urban sustainability goals []. The trajectory of MaaS development is commonly described in three stages (Figure 1): MaaS 1.0, focused on information aggregation and multimodal journey planning; MaaS 2.0, emphasizing enhanced decision-making through DSS integration; and MaaS 3.0, embedding sustainability as a core principle of mobility integration.

Figure 1.

Stages of MaaS development, adapted from [].

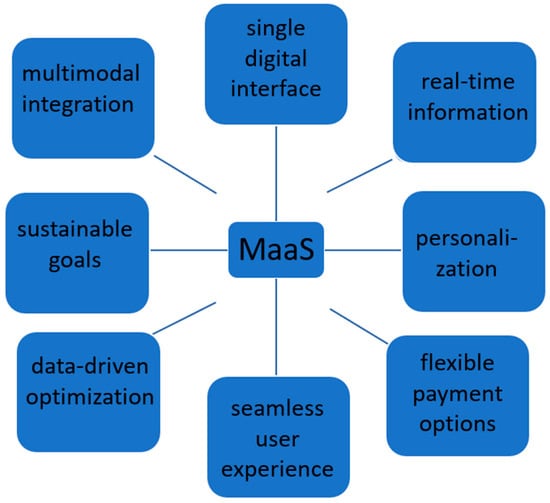

The MaaS ecosystem comprises a diverse range of stakeholders, each playing a critical role in its implementation and operation. These include customers, transport authorities, transport operators, data providers, technology and platform developers, ICT infrastructure providers, insurance companies, regulatory bodies, universities and research institutions, as well as media, marketing, and advertising agencies [,,]. Figure 2 summarizes the core functions managed by these stakeholders, highlighting the collaborative and interdisciplinary nature of the MaaS framework. A strong collaborative relationship among all stakeholders is essential to mitigate potential challenges. One of that challenge is conflicting interests can arise between public and private actors, as private mobility providers often prioritize profit, whereas public authorities focus on accessibility, sustainability, and social welfare, leading to misaligned incentives in service provision []. Second, power asymmetries in data ownership can develop because platform operators typically control large volumes of user and mobility data, granting them significant influence over pricing, routing, and service design, while public authorities and end-users have limited access, raising concerns regarding transparency, accountability, and equitable decision-making [].

Figure 2.

Core features of MaaS.

Globally, MaaS is being implemented or piloted in diverse formats personalized to local contexts. Some of the most widely recognized MaaS platforms include:

- Whim (Helsinki, Finland): Whim integrates public transport, taxis, car rentals, and shared mobility services into a single app. Users can plan, book, and pay for trips across multiple modes with subscription-based or pay-as-you-go options []. By offering a fully digital and flexible alternative to private car ownership, Whim has contributed to reducing congestion in the Helsinki metropolitan area and encouraging modal shift toward sustainable options [].

- Vienna MaaS, developed by WienMobil (Vienna, Austria): This app facilitates the discovery of various mobility options, such as accessible taxis, scooters, self-serve bicycles, vehicle sharing, public transportation, and parking lots. In 2025, approximately one-third of Vienna’s population utilized this application [].

- The Mobilatsshop (Hanover, Germany): MaaS application launched in 2016 by the GVH transport authority in collaboration with the public transport operator Ustra. The app integrates multiple urban transport options, including taxis, ride-sharing (e.g., Uber), car-sharing, buses, scooters, cycling, and vehicle rentals, allowing users to plan the most efficient routes across the city. Mobilatsshop supports in-app payments and prioritizes fair compensation for service providers. Access to the platform is limited to users holding a valid public transport annual pass [].

While MaaS platforms aim to provide seamless multimodal transportation options, the previous examples suggest that MaaS remains context-specific rather than universally transferable. For example, the development of Whim in Helsinki benefited from strong public–private collaboration, high public transit coverage, and institutional trust, conditions that are not easily replicated in other regions []. Also Mulley [] further highlights that MaaS success requires careful coordination across multiple actors and is constrained by local institutional and socio-technical conditions, emphasizing that MaaS is not universally transferable but must be adapted to specific regional contexts. Moreover, several critiques emerge when confronting the conceptual vision of MaaS with its real-world applications. In particular, the ability of MaaS to adapt to unexpected events and dynamic disruptions is often constrained by institutional, technical, and behavioral factors. Both the advantages and the potential risks associated with MaaS have been widely discussed in the literature [,,,,] and the most critical limitations are summarized below.

- Insufficient Real-Time Data Integration. MaaS platforms often struggle with integrating real-time data from diverse transportation providers. This lack of integration can lead to delays in updating travel information, causing users to make decisions based on out-of-date or inaccurate data during disruptions.

- Limited Flexibility in Dynamic Routing. Many MaaS applications are designed with fixed routing algorithms that may not accommodate sudden changes in traffic conditions or service availability. This rigidity can result in suboptimal routing during disruptions [].

- Equity and Accessibility Concerns. The benefits of MaaS during disruptions are not uniformly distributed across different socio-economic groups. Reference [] found that psychological motives and barriers influence the adoption of MaaS, with accessibility being a significant concern, emphasizing the need for inclusive design to ensure that MaaS services are accessible to all users, particularly during disruptions.

- Data Privacy and Security Issues. The extensive data collection required by MaaS platforms raises significant privacy concerns [].

- Lack of Robust Communication Channels. Inadequate user communication strategies limit the ability to carry out updates effectively during unexpected events [].

3.2. Proximity Theory

Proximity Theory (PT) provides a multidimensional context for analyzing relationships and interactions within complex systems. The origins and “grammar” of proximity, that emerged by the group Dynamiques de Proximité, commonly referred to as the French School of Proximity, are detailed in [,,]. According to [], PT encompasses five different dimensions: geographical, cognitive, institutional, organizational, and social, each of which influences coordination, learning, and adaptability.

Geographical proximity refers to the spatial closeness or physical distance between actors involved in a system []. Studies demonstrate its central role in shaping transport accessibility and urban development. For example, [] examined how urban design affects public transport network coverage and potential demand by comparing the Madrid Metro layout in 2018 with four hypothetical street network scenarios: high-density irregular, low-density irregular, orthogonal, and station-oriented. Their analysis shows that a station-oriented street system leads to significant population and employment growth, which contributes to a high increase in the potential demand for public transport. Later, Kasraian et al. [] investigated how transport accessibility, proximity to existing urban areas, and spatial policies influence urbanization dynamics in the Randstad area over five decades (1960–2010) using generalized estimating equations (GEE). The authors found that urbanization is primarily driven by transport accessibility, with road accessibility more influential than rail and that urban proximity is an even stronger determinant of urbanization patterns than accessibility or spatial policies. These findings highlight a circular and dynamic relationship between transport accessibility and urbanization, where each factor reinforces the other over time, suggesting a dynamic interaction where each reinforces the other over time. Although Boschma [], does not explicitly mention temporal proximity, Polyviou [], in a context outside transport, discusses it as a sub-dimension of geographical proximity. Building on this perspective, the present research formally advances the proposal of temporal proximity as a sub-dimension of geographical proximity, highlighting its particular relevance for transport planning and management, where synchronization, timing of operations, and coordinated responses to disruptions are critical.

Cognitive proximity relates to the extent of shared knowledge, understanding, and interpretive frameworks among interacting parties. It is related to how user’s/consumers’ perceive, interpret process, and communicate information according to mental models and categories []. In public transport, cognitive proximity is achieved when service providers and users share a common understanding of system functionality, service expectations, and procedures during disruptions. Such alignment reduces misperceptions, increases user confidence, and enables smoother service recovery interactions.

Institutional proximity refers to the existence of shared formal and informal rules, processes, values and its key dimension is trust based on common institutions [], promoting collaboration between different actors []. High institutional proximity fosters collaboration among regulators, operators, and other stakeholders by providing common norms and processes for decision-making and compliance.

Organizational proximity refers to the degree of alignment, coordination, and compatibility between institutions or stakeholders operating within a system []. In public transport, strong organizational proximity allows transit agencies, digital platforms, and private mobility operators to collaborate efficiently, share critical operational data, and jointly respond to disruptions, enabling seamless user experiences.

Social proximity, builds trust relationships, familiarity, and emotional connection, enhancing collaboration []. Within transport systems, high social proximity enhances user loyalty, patience during service disruptions, and emotional engagement with providers. This emotional closeness is especially valuable during crises, as it helps preserve user satisfaction even when performance falters.

According to the literature [,,] proximity theory is guided by seven main principles which help explain how the five dimensions (geographical, cognitive, institutional, organizational and social) interact to shape collaboration, coordination, and user experience in public transport networks:

- Proximity is not exclusively spatial. While geographical proximity is important for accessibility and physical connectivity, non-spatial dimensions (cognitive, institutional, organizational, social) also influence system performance. In public transport, this principle emphasizes that service efficiency and resilience depend not only on station placement or network design but also on shared knowledge, aligned organizational processes, trust, and social engagement.

- Non-spatial proximities are based on shared similarity and the logic of belonging: Cognitive, institutional, and social proximities rely on common understanding, norms, and relationships. For public transport, shared procedures among operators (institutional), aligned mental models between staff and users (cognitive), and trust between agencies and communities (social) improve responsiveness during disruptions.

- Non-spatial proximities are constructed. Unlike physical distance, proximities such as organizational alignment or cognitive understanding must be actively built through coordination, training, communication, and engagement. In the context of transport disruptions, this principle highlights that resilience does not emerge automatically but is the product of deliberate investments in preparedness.

- Proximities represent potentialities that require interaction to become effective. For instance, stations may be physically close, but if transfer schedules are poorly coordinated during disruptions, the advantages of proximity are lost, resulting in delays and reduced system resilience.

- Perceived geographical proximity is influenced by other proximities. Users’ perception of service accessibility can be affected by cognitive or social proximity. Even if stations are physically distant, clear communication, real-time updates, and trust in the operator can make the system feel more accessible and responsive during disruptions.

- Proximity dimensions can substitute, overlap, or reinforce each other. If one dimension is weak, others can compensate. For instance, in areas where geographical proximity is limited, high cognitive and organizational proximity can ensure efficient coordination and minimize disruption impacts []. Similarly, in some contexts, strong social proximity can buffer the effects of institutional gaps by maintaining user confidence and loyalty [,] put forward that cognitive and institutional proximities can both facilitate knowledge exchange between stakeholders when combined with geographical proximity.

- Proximity is dynamic and evolving. According to Balland et al. [], proximity can increase over time through various processes, such as agglomeration (geographical proximity), learning (cognitive proximity), institutionalization (institutional proximity), integration (organizational proximity) and decoupling (social proximity). In the context of transport disruptions, geographical proximity can be temporarily reconfigured when passengers shift to nearby stations, stops, or substitute modes during a disruption, while temporal proximity evolves as delays accumulate, recovery times shorten, or service rescheduling restores alignment. Within public transport networks, these dimensions offer valuable insights into how spatial, cognitive, institutional, organizational, and social distances affect collaboration among stakeholders, user experience, and system resilience, particularly during service disruptions [,]. However, while proximity often enhances coordination and user experience, it can also produce negative effects when imbalanced or misaligned. Excessive geographical proximity, such as oversaturation of transport services in central areas, may lead to congestion, inefficiency, and neglect of peripheral regions, thereby exacerbating spatial inequality. Cognitive proximity, if too high among planners or between institutions, can lead to groupthink, limiting innovation and excluding diverse user perspectives. Similarly, overly strong institutional proximity between regulators and operators may reinforce rigid structures that resist necessary reform, particularly in the face of emerging mobility models like MaaS. Organizational proximity, when over-concentrated, can result in dependency on a small set of actors, reducing system resilience and responsiveness. Finally, social proximity, while promoting trust, may also induce exclusivity or favoritism, where the needs of specific user groups are prioritized at the expense of broader accessibility and equity. Recognizing these potential drawbacks is essential for designing balanced and inclusive public transport systems.

When applied to MaaS, the PT dimensions provide a comprehensive framework for enhancing the management of service disruptions, with the geographical and temporal dimensions being particularly relevant. Proximity Theory can guide operators in reducing negative user perceptions through immediate communication, local responsiveness, and trust-building during operational disruptions. By emphasizing human-centered interactions rather than purely functional responses, PT reframes disruptions as opportunities for meaningful engagement and continuous user loyalty, rather than mere service failures.

3.3. Public Transport Disruption

3.3.1. Impact

Although public transport systems are essential for urban mobility, these systems may fail, and the corresponding consequences can be significant and far-reaching. A transport service disruption refers to any planned or unplanned event or condition that affects the normal operation of public transport services []. They can be minor or major, and short-lived or long-lasting, affecting both service reliability and customer satisfaction. Planned disruptions are scheduled interruptions that occur intentionally, often for maintenance, infrastructure upgrades, or special events. Examples include track maintenance on a metro line, road closures for construction or scheduled vehicle inspections. Although planned, these disruptions can still impact passengers, requiring advance notice, alternative routes, and adjustments in service schedules to minimize inconvenience. Effective communication and coordination are essential to help passengers adapt smoothly. Unplanned disruptions, on the other hand, occur unexpectedly and are often caused by accidents, technical failures, extreme weather conditions, or sudden traffic congestion. These disruptions are more challenging to manage because they require real-time responses and rapid decision-making. Public transport operators must rely on dynamic scheduling, rerouting, and real-time information systems to mitigate the impact on passengers. Unplanned disruptions not only affect service reliability but can also reduce user trust and satisfaction if not managed efficiently. Building on this, Müller et al. [] employ agent-based simulation to examine unexpected disruptions of an underground line in Berlin, focusing on how both the disruption itself and the timing of information provision affect passengers. Their findings highlight that transport operators can significantly reduce the negative consequences of unplanned disruptions by communicating promptly with passengers, as delayed information leads to substantial increases in travel times. Subsequently, Siegrist et al. [] propose a multi-level disruption management framework for road interruptions within a multimodal network, assessing their cascading impacts across different transport modes. Together, these studies illustrate how both timely communication and systemic management strategies are critical for mitigating the effects of transport disruptions. Complementing these insights, Eltved et al. [] propose a methodology based on smart card data to analyze the impacts of long-term planned disruptions on passenger travel behavior. The approach applies k-means clustering to group passengers according to their travel patterns before and after a line closure, allowing for the observation of how different passenger segments adapted to the disruption. To account for general travel trends, these behavioral changes are compared with a reference group of unaffected lines. In addition, hierarchical clustering of daily travel patterns enables a more detailed examination of the responses of specific passenger groups. The methodology is applied to a three-month closure of a rail line in the Greater Copenhagen area. Results indicate that passengers with regular commuting behavior were particularly affected, with their travel activity decreasing after the disruption. Overall, the study demonstrates how the proposed methodology can provide valuable insights into the heterogeneous impacts of long-term disruptions, offering practical implications for public transport agencies when planning and managing maintenance projects.

Building on these contributions, Table 2 presents the most common service disruptions and their impact on proximity. These service disruptions are usually due to technical disruptions, such as vehicle breakdowns, signaling issues; traffic incidents; extreme weather events that damage infrastructure; strikes or labor disputes; infrastructure repairs, disruptions and construction; security events that require evacuation.

Table 2.

Common services disruptions and their impact on proximity.

3.3.2. Management

When disruptions occur, such as delays or service interruptions, users’ tolerance thresholds are tested. Passengers typically have a certain level of patience and willingness to accept minor delays, especially if they are well-informed and provided with alternatives. However, prolonged or frequent disruptions can quickly erode trust and lead to dissatisfaction. By addressing service disruptions promptly, service recovery aligned with the principles of Service Management 5.0 can reduce negative customer reactions and support long-term loyalty []. Potoglou and Spinney et al. [] explore various theoretical tools for analyzing passenger behavior during transport disruptions, drawing on economic and social psychology theories as well as mobilities approaches. To mitigate negative reactions and maintain loyalty, transport operators employ structured service recovery strategies, including the Triple R Model (Respond, Rectify, Reassure), the Service Recovery Paradox, SERVQUAL-based Recovery (GAP Model), Incident Response Plans, Passenger Charter-Based Recovery, and the Lean Recovery Model [,,]. Each model has limitations when applied individually; therefore, in the context of MaaS, hybrid approaches are recommended. Combining real-time reactive measures (e.g., Triple R for immediate passenger communication) with strategic, diagnostic tools (e.g., GAP model for long-term service improvements) can provide the most resilient response to both planned and unplanned disruptions.

Service recovery in MaaS focuses on promptly addressing disruptions by delivering timely communication, offering alternative travel options, and providing compensation when appropriate, thereby maintaining user satisfaction and loyalty even during unexpected challenges. In line with this, Krusche et al. [] developed a public transport crowding messaging system for travelers, designed to reduce passenger anxiety through behavior change techniques. Similarly, Drabicki et al. [] investigated the impact of providing real-time crowding information (RTCI) at stops for the next two vehicle departures, finding that such information can encourage passengers to wait for less-crowded vehicles, helping to mitigate the bunching effect.

Traffic disruptions can significantly weak MaaS reliability. Effective management of such disruptions is essential, and this can be approached either reactively or proactively. Proactive management focuses on anticipation and prevention, aiming to avoid service breakdowns or reduce their severity, while reactive management involves responding swiftly to disruptions as they occur, restoring service as quickly as possible. The distinction between these two approaches is crucial in designing resilient MaaS systems, as outlined in the framework for proactive versus reactive management of disruptions in MaaS, presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Proactive vs. Reactive Management of Disruptions in MaaS [,,,,].

MaaS systems rely heavily on user trust and seamless intermodal journeys. Proactive management aligns better with the user-centric and data-driven nature of MaaS, though reactive strategies remain important for unforeseen events. Thus, transport operators are moving from a reactive to a proactive management approach, recognizing the need for anticipation and prevention of disruptions, rather than merely responding to them. This transition is supported by ongoing research within the framework of Service Management 5.0, where studies are focused on leveraging advanced technologies, predictive analytics, and real-time data to enhance operational efficiency and customer experience. For example, [] introduce a multimodal transport model that simulates travelers’ behavior after a large-scale infrastructure failure at a critical node in the European TEN-T network, allowing the modeling of impacts of disruptions in high detail. Similarly, Jin et al. [] propose a mathematical model, a bi-level mixed-integer nonlinear problem (MINLP), to identify the critical combination of roads in urban road networks for multiple disruption scenario. The model was tested under multiple scenario, with different levels of disruption rate and travel demand. Despite some limitations identified by the authors, the model provides valuable insights into the potential impacts of road combinations during disruptions. In a related approach, Iliopoulou et al. [] introduce a multi-objective algorithm, the Adaptive Variable Neighborhood Search (MO-AVNS), aimed at identifying critical disruption scenarios affecting transport network serviceability. This algorithm uses a transit assignment model to analyze passenger responses to disruptions, further expanding our understanding of network resilience in the face of disturbances. Building on this focus, Zhang et al. [] propose a resilience assessment framework that uses performance-based metrics to evaluate system performance under stress. Their dynamic simulation procedure accounts for disruptions’ effects on passenger path selection and departure times, allowing for the modeling of flow variations. Applied to Beijing’s multimodal public transportation system, the study reveals strong resistance and recovery capacities, but still a lack of robustness. Complementing this perspective, Nalin et al. [] explore the multifaceted nature of accessibility, highlighting the critical role of delays in identifying accessibility gaps. By analyzing the prolonged closure of a major urban road in Bologna, Italy, their study assesses how such a disruption can alter accessibility patterns within the network. Together, these studies contribute to a proactive framework, providing tools to predict and manage disruptions more effectively, strengthening the resilience of transport networks. By integrating advanced modeling techniques, simulation tools, and user-centered approaches, they collectively contribute to a deeper understanding of how transport systems can anticipate, absorb, and adapt to disruptions. The most resilient MaaS systems are likely to adopt hybrid approaches that combine proactive planning with agile reactive responses. While reactive strategies remain essential, the future of MaaS will increasingly depend on proactive disruption management enabled by real-time data, predictive analytics, and user-centric design. By integrating both approaches, MaaS providers can build transport systems that are not only more resilient and adaptable, but also more reliable and user-friendly. These hybrid approach significantly enhances user satisfaction, trust, and resilience in MaaS.

However, other authors [,] highlight that transport disruptions can create opportunities to promote sustainable behavior. Building on the framework proposed by Potoglou and Spinney [], which classifies disruptions by their plannedness, scale, frequency, and duration, McGuicken et al. [] recommend comprehensive strategies that manage disruptions through robust political leadership, aiming to reduce entrenched car dependency for environmental purposes. A stronger integration of sustainability objectives into the proactive/reactive disruption framework would significantly enhance its relevance for long-term urban mobility planning. For example, proactive strategies could prioritize alternative modes that reduce carbon emissions, such as promoting shared mobility, cycling, or public transport during disruptions, rather than defaulting to private car alternatives. Similarly, reactive measures could include targeted communication encouraging low-impact travel choices, or dynamic rerouting that minimizes congestion and pollution hotspots. By embedding sustainability into both anticipatory and responsive disruption strategies, MaaS providers and transport operators can not only maintain service reliability but also support environmental objectives, social equity, and resilient urban mobility ecosystems over the long term. Studies [,,] have increasingly emphasized that sustainable disruption management is key to achieving integrated urban mobility systems that balance operational efficiency with environmental and social goals.

3.4. Review of Mathematical Models for Transport Network Optimization

Recent advancements in mathematical modeling have significantly enhanced transport network optimization, particularly in addressing challenges posed by disruptions and evolving urban dynamics. In this context, Gao et al. [] develop a mixed-integer linear programming model for rescheduling metro lines under overcrowded conditions following disruptions. Tested on the Beijing Metro, the model demonstrates both effectiveness and efficiency in restoring operations and alleviating passenger congestion during service interruptions. In the same year, Vale and Ribeiro [] present a linear mixed binary program for optimizing intermodal roundtrips for passenger and freight transport. Their computational experiments highlight the model’s efficacy in minimizing total travel costs associated with roundtrip movements. Building on this foundation, Vale and Ribeiro [] extend their work by proposing a multi-objective routing model for optimizing intermodal one-way trips. The model simultaneously minimizes travel time and CO2 emissions, considering the availability of multiple transport modes between any pair of nodes, and is validated as an efficient solution for sustainable intermodal routing. More recently, Ulvi et al. [] introduce an urban traffic mobility optimization model that integrates data mining with mathematical modeling to analyze daily traffic dynamics. While the model primarily focuses on reducing discrepancies and understanding variations in traffic intensity during peak hours, it also holds potential for managing transport disruptions, as it can identify abnormal traffic variations, congestion points, and bottlenecks that often intensify during such events. Similarly, Leffler et al. [] propose a model that aims to improve route selection by accounting for dynamic changes in traffic conditions and service availability. Extending this focus more directly toward disruption and emergency management, Jiang and Song [] propose a robust emergency location model that accounts for uncertainties in transport capacity caused by emergencies. Their model introduces concepts such as flow distribution betweenness centrality, measuring how often a node acts as a bridge on the shortest paths between all other node pairs, and the transport capacity effect coefficient, to optimize the location and allocation of emergency facilities in emergency scenarios. Building on the need to ensure network resilience, Lu et al. [] focus on simulation-based recovery measure optimization to enhance traffic resilience in large-scale transportation networks under supply side disruptions, presenting a model optimizing lane reversal strategies to improve traffic flow during post-disruption scenario. Complementing this, Jaber et al. [] explore the management of public transport disruptions through Resilience as a service (RaaS) strategies, developing an optimization model to efficiently allocate resources and minimize costs for both operators and passengers. The model considers multiple transportation modes, such as buses, taxis, and other alternatives, as substitute services to bridge disrupted rail lines. By dynamically selecting and deploying the most suitable vehicles, the approach ensures continuity of transport services, which is critical in both routine disruptions and emergency scenarios, where rapid mobilization and resource allocation can mitigate the impact on mobility and public safety. The effectiveness of the model is demonstrated through a case study in the Île-de-France region. Together, these studies highlight a comprehensive approach to disruption management, where traffic flow optimization at the network level can be integrated with dynamic public transport resource allocation, providing resilience in both routine and emergency disruption scenarios.

Focusing at the urban network level, Ren et al. [] propose a multidimensional urban transportation network optimization framework to address structural failure risks from aging infrastructure and regional connectivity bottlenecks. The model includes a dynamic simulation-based traffic network model for bridge collapses, with an algorithm that iteratively updates paths and flows using Dijkstra’s method. Similarly addressing emergency events, Cui et al. [] develop an optimization framework formulated as a mixed-integer nonlinear programming model to guide the sequencing of restoration actions across multiple stages following a transportation network disruption. This model aims to maximize system resilience and is validated through its application to the Tongzhou transportation network. Together, these studies illustrate how emergency preparedness, resilience-oriented traffic optimization, and network-level restoration planning can be integrated to enhance urban transportation systems under both routine disruptions and critical emergency scenarios.

4. Integrated Approach by Applying the Proximity Theory into Sustainable MaaS for Managing Service Disruptions

The integration of the proximity theory into the management of service disruptions within sustainable MaaS platforms offers a novel lens for understanding and improving customer experience during disruptions. In the context of MaaS, where various transport modes and providers are coordinated through a single digital interface, disruptions can have complex and far-reaching impacts. By applying the dimensions of proximity, transport operators and platform providers can identify more targeted strategies to reduce perceived distance between users and services, foster trust, enhance coordination, and support timely, and context-sensitive communication during service disruptions.

To operationalize this concept, Table 4 outlines the role of MaaS for enhancing customer experience during disruptions, in the five different dimensions of Proximity Theory (geographical, cognitive, institutional, organizational, and social), which directly addresses one of the key research questions of this study.

Table 4.

Role of MaaS for enhancing customer experience during disruptions, within the PT framework.

Along with the strategies presented in Table 4 for enhancing customer experience during disruptions, it is important to highlight that community engagement plays a crucial role in both the geographic and social dimensions of proximity theory. The geographic dimension highlights the importance of location and accessibility in shaping users’ experiences, making the involvement of local communities in planning and feedback processes essential for ensuring public transport systems meet the needs of the people they serve. By engaging passengers in decision-making processes, directly tied to the social dimension, such as through surveys or public consultations, transport authorities can fit disruption management strategies to better address the challenges and demands of different regions or communities. Furthermore, from the perspective of the geographic dimension, the physical layout and accessibility of transport facilities play a key role in ensuring the efficiency and resilience of public transportation. Designing stations and terminals to facilitate alternative routing and backup services is important to maintaining service continuity during disruptions. The strategic location of these facilities should allow passengers to rapidly access alternative transport options, minimizing the inconvenience caused by delays or service interruptions, ensuring that transport networks. This approach ensures that transport networks remain flexible and responsive to changing demand, enabling users to navigate the system with ease, even in times of disruption.

Responding to RG2 (To what extent does the integration of proximity-based strategies influence user satisfaction, trust, and resilience in response to service disruptions in MaaS ecosystems?), proximity-based strategies, especially those involving geographical and cognitive proximity, directly impact user satisfaction during traffic disruptions. When passengers are geographically close to alternative services or routes and receive timely, clear information about their options, they experience less inconvenience. Cognitive proximity, through intuitive and accessible user interfaces, ensures passengers can easily navigate these alternatives, leading to higher levels of satisfaction. In contrast, the lack of these strategies often leads to confusion and frustration. Trust is deeply influenced by social and institutional proximity. Social proximity, such as transparent communication and user engagement during disruptions, fosters a sense of community between passengers and service providers. If users perceive the system as responsive, empathetic, and actively working to mitigate disruption impacts, they are more likely to trust it. Institutional proximity ensures that there are reliable frameworks and policies in place to handle disruptions, further enhancing trust in the system’s ability to manage future challenges. The resilience of a MaaS platform is enhanced through a combination of organizational and geographical proximity. Organizational proximity refers to the integration and coordination between transport service providers, ensuring a swift response to disruptions and minimizing operational downtime. Geographical proximity allows passengers to access alternative modes of transport easily, reducing their dependency on one service. By leveraging these proximities, MaaS ecosystems can adapt quickly to disruptions, offering users more options and support, which enhances the system’s overall resilience.

The spatial–temporal dimensions of passenger travel are especially relevant for managing transport disruptions. Based on this premise, it is proposed that MaaS platform integrates a spatial–temporal PT framework, comprising five key modules: detection, proximity mapping, time-based prioritization, personalized recommendations, and dynamic incentives, as illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Modules of the proposed spatial–temporal PT framework.

The proposed framework for managing urban mobility disruptions within a MaaS platform is composed of five interconnected modules that leverage collaboration among transport stakeholders to provide efficient and balanced travel alternatives. The first module—detection—gathers live disruption data from various transport stakeholders, including metro services, bus operators, bike-sharing providers, ensuring the system has real-time awareness of service interruptions and availability across modes. The proximity mapping module addresses the spatial dimension by identifying alternative transport options within a predefined walking distance for the affected travelers. This includes buses, bike-sharing stations, and other possibilities, allowing travelers to quickly access feasible alternatives nearby. The time-based prioritization module evaluates these alternatives according to the temporal dimension, ranking options based on shortest wait times and fastest overall travel times. This ensures travelers are guided toward the most efficient routes available at any given moment. Through the personalized recommendations module, travelers receive real-time, tailored guidance that combines walking with alternative transport modes. Notifications provide optimized rerouting options based on individual preferences, location, and disruption impact. Finally, the dynamic incentives module encourages balanced demand across modes. By offering discounted vouchers or other incentives for transport options with lower current usage, such as shared bikes, the platform prevents overcrowding and promotes optimal system utilization. Together, these five modules form a collaborative, stakeholder-driven MaaS framework that enhances traveler experience, reduces congestion, and ensures more resilient, flexible urban mobility during disruptions.

5. Model Formulation

In this section, a mixed-integer programming (MIP) model is proposed to support the implementation of Modules 2 and 3, as illustrated in Figure 3. The model assigns travelers to feasible routes while considering multiple performance dimensions: delay penalties, walking and transfer limits, arc capacity and crowding effects, and environmental costs in terms of CO2 emissions on arcs traveled by motorized vehicles. The objective function (Equation (1)) minimizes the weighted sum of these components.

where , represent the travelers; , the feasible routes for traveler i; , the arcs in the transport network; respectively the delay, waiting time, transfer, walking distance and crowding penalties; , travel time for traveler i in route r; , latest acceptable arrival time for traveler i; , walking time for traveler i in route r; , number of transfers in route r, , walking distance for traveler i in route r, , CO2 contribution for each traveler–route pair, being the decision variables and .

Variable takes value 1 if traveler i is assigned to route r or 0, otherwise. The integer variable represents the crowding excess in arc e that exceed its nominal capacity, .

The objective function (Equation (1)) sums, over all travelers and routes, the weighted contributions of:

- Delay: penalizes late arrivals beyond the acceptable time ;

- Waiting time: time spent waiting at stations or stops;

- Transfers: number of modal changes along the route;

- Walking distance: pedestrian segments of the trip;

- CO2 emissions: only for arcs traveled by motorized vehicles, proportional to the distance traveled and number of passengers;

- Arc crowding: penalizing flows exceeding nominal capacities.

Mathematically, the CO2 contribution for each traveler–route pair, , is expressed as Equation (2):

The variable serves as a binary indicator that identifies whether a given segment/arc within route r is a walking segment or a motorized segment. If , segment is a walking segment that do not produce CO2 ( while , is a motorized segment where CO2 emission term becomes arc length x emission of CO2/m/traveler.

The constraints of the model (Equations (3)–(8)), ensures:

- Traveler assignment: each traveler i is assigned to a unique route r

- Arc capacity/crowding: crowding on arc e occurs if total assigned travelers exceed nominal capacitywhere represents whether traveler i assigned to route r uses arc e.

- Feasible routes consider maximum limits for walking distance and transfer numbers

- Definition of variables: is binary; is integer non-binary

6. Case-Study

In this section, two scenarios are analyzed to capture both operational efficiency and environmental performance.

- Scenario 1: the objective function minimizes generalized travel costs without environmental considerations, i.e.,

- Scenario 2: the objective function includes CO2 emissions on arcs traversed by motorized vehicles, with emissions per arc computed as arc length x emission of CO2/m/traveler; an emission factor of 0.06 kg/m/traveler was used, representative of a typical motorized vehicles.

By comparing Scenarios 1 and 2, the model allows the evaluation of how route choices and network performance evolve when environmental impacts are explicitly considered, thereby addressing both spatial–temporal proximity and environmental performance dimensions.

6.1. Data

The case study considers a transportation network with 10 travelers, each having 5 candidate routes, for a total of 50 potential routes. Each route can include up to 8 arcs supporting a maximum of 3 travelers. Routes are characterized by travel time, walking distance, number of transfers, and waiting time, reflecting both user convenience and network performance (Table 5). To ensure feasible travel, the maximum walking distance is 1200 m and the maximum number of transfers per traveler is 2. Table 6 summarizes, for each candidate route, the arcs that comprise the route and the total number of arcs while Table 7 presents the nominal capacity of each arc. These parameters define the scope of the route-choice problem and provide the input for the scalable MaaS optimization model.

Table 5.

Route definition per traveler.

Table 6.

Composition of each candidate routes.

Table 7.

Arc nominal capacity.

The objective function of the MaaS optimization model (Equation (1)) is designed to account for various disruptions that travelers may encounter in the network. The delay penalty (α = 2) captures the impact of late arrivals due to disruptions such as congestion or service delays. The waiting time (β = 1) and transfer penalties (γ = 1) reflect the inconvenience caused by unscheduled waits or additional transfers when primary routes are disrupted. The walking distance penalty (μ = 0.5) addresses situations where travelers may need to walk longer distances to reach alternative connections. Additionally, the crowding penalty (δ = 2) penalizes the use of network arcs that exceed their nominal capacity, which can occur during disruptions that force travelers onto fewer available routes. The penalty parameter values (α = 2, β = 1, γ = 1, μ = 0.5, δ = 2) were selected based on illustrative assumptions commonly used in similar multimodal transport and MaaS optimization studies to demonstrate the model’s behavior under different disruption scenarios. These values were chosen to represent the relative importance of each factor, assigning higher weights to delay and crowding penalties (α and δ) to emphasize their stronger impact on traveler satisfaction, while assigning lower weights to walking and transfer penalties (μ and γ) to reflect moderate inconvenience. All these weighted components enable the objective function to systematically evaluate the effect of transport disruptions on both traveler experience and network performance. These weights are illustrative and may be adjusted to reflect different priorities or policy objectives. For example, in contexts where minimizing traveler delays is more critical than reducing walking distances, α could be increased relative to μ. Conversely, in networks where accessibility and comfort are prioritized, walking and transfer penalties (μ and γ) might be assigned higher values. The appropriate values for these penalties can be defined based on historical data, user surveys, expert judgment, or sensitivity analysis to ensure the objective function accurately captures the relative importance of each disruption type in the specific study context.

6.2. Results and Discussion

The mixed-integer programming model was implemented in MATLAB (https://matlab.mathworks.com/, accessed on 15 July 2025) and solved using the branch-and-bound algorithm. The branch-and-bound method was chosen because it is a widely validated exact optimization technique for MIP. This approach ensures that globally optimal solutions are found within reasonable computational time for medium-scale problem instances, such as the illustrative case presented in this study. However, for larger transport networks with more travelers and additional constraints, more powerful optimization algorithms and software may be required to ensure computational efficiency and scalability.

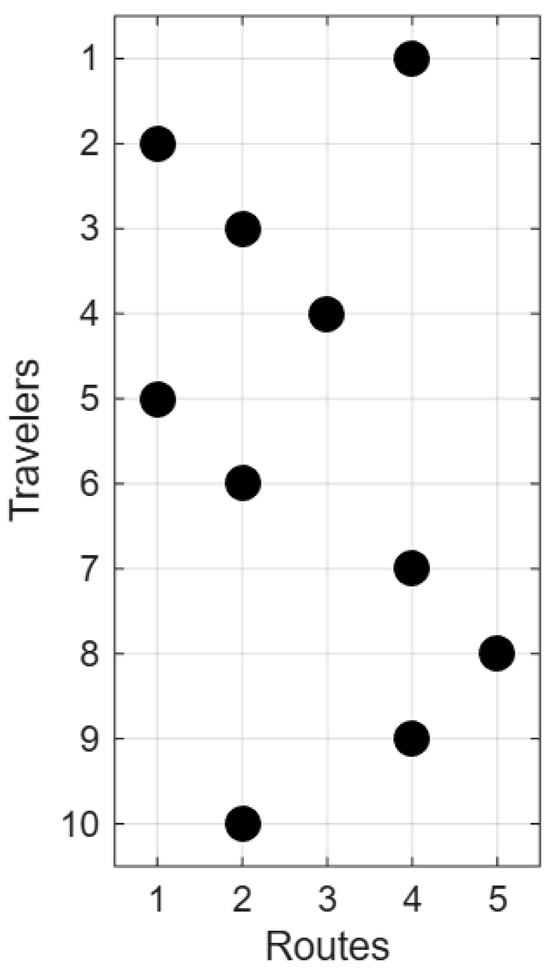

- Scenario 1: No environmental consideration

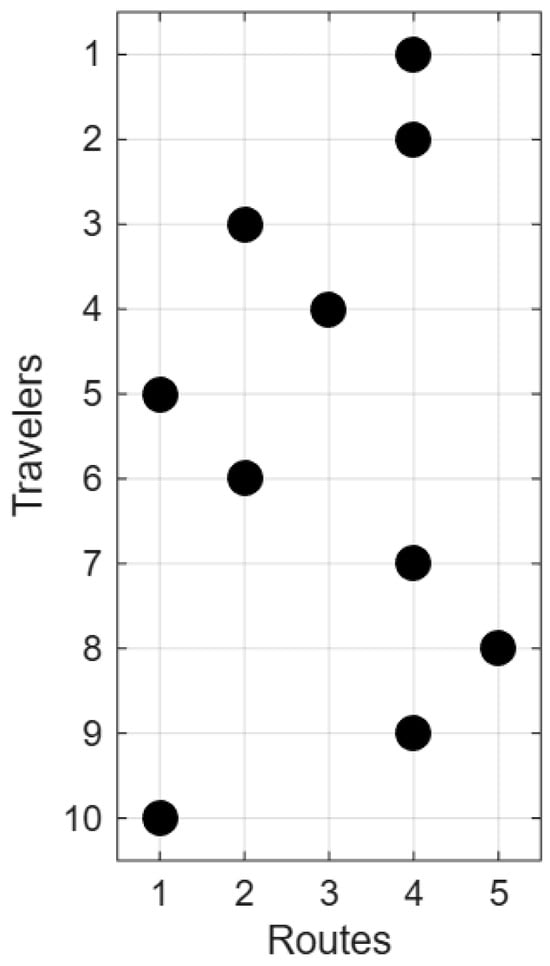

Figure 4 presents, for Scenario 1, the outcome of the optimization model, showing the assignment of travelers to the available routes. The solution indicates that Route 1 is allocated to travelers 2 and 5, while Route 2 is chosen for travelers 3, 6, and 10. Route 3 is assigned exclusively to traveler 4, and Route 4 is selected for travelers 1, 7, and 9. Lastly, Route 5 is allocated solely to traveler 8. The results highlight that Routes 2 and 4 are the most utilized, each accommodating three travelers, followed by Route 1 with two travelers. By contrast, Routes 3 and 5 are the least utilized, with only one traveler assigned to each.

Figure 4.

Scenario 1: assignment of travelers to the available routes.

Table 8 presents the detailed solution generated by the optimization model, showing the specific route allocation and corresponding travel metrics for each traveler. For every individual, the table reports the selected route along with total travel time, waiting time, walking distance, and the number of transfers required. For instance, traveler 1 is assigned to Route 4 with a travel time of 27 min, a 4 min wait, 1112 m of walking, and one transfer.

Table 8.

Scenario 1: detailed solution per traveler.

The results of the route assignment model for 10 travelers indicate that the algorithm successfully allocated feasible routes while balancing travel time, waiting time, walking distance, and number of transfers. Travel times for the selected routes range from 25 to 43 min, showing variability depending on the chosen route and individual traveler characteristics. Waiting times vary between 3 and 12 min, reflecting the differing schedules of the selected transit options. Walking distances show significant variation, from 37 m to over 1100 m, highlighting the impact of route selection on traveler effort. The number of transfers per traveler ranges from 0 to 2, demonstrating that the algorithm minimizes transfers where possible while still respecting network constraints. Overall, these results indicate that the model effectively identifies route assignments that balance travel efficiency, convenience, and physical effort, providing practical insights for managing traveler experiences in a MaaS framework.

The attained objective value of this problem is 128.99 and it represents the total “cost” of the solution as defined by the model’s weighted criteria. It aggregates penalties related to traveler inconvenience, including delays, waiting times, transfers, and walking distances, together with network inefficiencies such as arc overcrowding. Each component is weighted to balance multiple aspects of service quality. For comparison, a scenario in which no optimization is applied would result in a substantially higher objective value, indicating greater delays, longer waiting times, and more transfers. Thus, the achieved value of 128.99 demonstrates that the proposed route assignments provide a significantly improved balance between traveler convenience and network efficiency.

- Scenario 2: CO2 emissions on arcs traveled by motorized vehicles

Figure 5 presents the traveler–route assignment for Scenario 2 demonstrating how the optimization model distributes travelers across the available routes while incorporating CO2 emission considerations. The results show a balanced allocation of travelers, with no single route becoming overly congested, reflecting the model’s ability to diversify assignments while minimizing travel disutility and environmental penalties.

Figure 5.

Scenario 2: assignment of travelers to the available routes.

The detailed solution per traveler is presented in Table 9. From the results, most travelers were allocated to routes with moderate emissions ranging between 36 and 72 kg of CO2. Travelers 1, 2, 7, and 9 were assigned to Route 4, with relatively low waiting times but moderate walking distances and consistent CO2 emissions of 60 kg. In contrast, Travelers 3, 6, and 8 experienced greater emission levels of 72 kg, partly due to the higher number of arcs with motorized transport and transfers on Routes 2 and 5. Travelers assigned to Route 1 (Travelers 5 and 10) exhibited the lowest emissions (36 kg), but their travel times were comparable to the other routes, showing that environmentally favorable options do not always imply significant time savings.

Table 9.

Scenario 2: detailed solution per traveler.

A comparison between Scenario 1 (without CO2 consideration) and Scenario 2 (with CO2 penalties) reveals notable differences in traveler assignments and performance metrics. In Scenario 1, Traveler 2 was assigned to Route 1, with a longer travel time (43 min) and one transfer, whereas in Scenario 2, the traveler switched to Route 4, achieving a shorter travel time (35 min), eliminating transfers, but incurring higher CO2 emissions (60 kg). Traveler 10 also shifted routes, moving from Route 2 (30 min, 10 min waiting, 558 m walking, 1 transfer) in Scenario 1 to Route 1 (39 min, 8 min waiting, 249 m walking, 2 transfers) in Scenario 2, showing that the model sometimes sacrifices travel time efficiency to reduce emissions. For most other travelers, assignments remained stable across scenarios (e.g., Travelers 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9), with similar travel times and route choices. However, in Scenario 2, these routes were explicitly penalized for their environmental impact, resulting in calculated emissions ranging from 36 to 72 kg.

Overall, introducing CO2 costs led some travelers to shift to routes with fewer or shorter motorized arcs, thereby reducing emissions at the expense of slightly longer travel times or additional transfers in certain cases. This demonstrates the model’s ability to balance user convenience with environmental sustainability.

7. Research Gaps and Future Directions

The integration of proximity theory into the management of public transport service disruptions within sustainable MaaS represents an emerging research area with the potential to enhance both customer experience and operational resilience. Despite this promise, several research gaps remain, offering opportunities for future studies to refine and expand this integrated approach.

7.1. Lack of Research on Proximity Dimensions in Sustainable MaaS

Although proximity theory has been extensively studied in other contexts [,], its application to sustainable MaaS, particularly regarding how the different dimensions of proximity (geographical, cognitive, organizational, institutional, and social) affect user experience during service disruptions, remains underexplored []. Understanding these dynamics is crucial for designing interventions that improve service reliability and passenger satisfaction while keeping environmental goals.

7.2. Long-Term Resilience and Adaptation to Disruptions

While existing studies often focus on short-term responses to service disruptions [,], there is limited research on how MaaS systems can build long-term resilience. Future studies could investigate how proximity-based strategies enable platforms to adapt over time, enhancing their capacity to respond effectively to both anticipated and unforeseen disruptions [,].

7.3. Potential for AI and Predictive Analytics in Functional Proximity

Artificial intelligence (AI) and predictive analytics can enhance sustainable MaaS responsiveness by anticipating disruptions, forecasting user needs, and offering real-time solutions [,]. Research should examine how these technologies can operationalize proximity-based strategies while maintaining user trust and data privacy [].

7.4. Impact of User Engagement on Proximity

User engagement, including crowdsourced data, feedback, and other participatory mechanisms, represents a key aspect of social proximity []. Investigating how such engagement can improve disruption management will provide insights into co-creation strategies that enhance service adaptability and responsiveness.

7.5. Ethical Challenges

Applying proximity theory in MaaS raises ethical considerations related to data privacy, equity, and transparency. Proximity-based strategies often rely on sensitive user information, such as travel history and real-time location, which must be collected and used in compliance with privacy laws [,]. Furthermore, these strategies should ensure equitable access for all users and foster trust by demonstrating transparency and fairness, particularly during service disruptions [].

8. Conclusions

The novelty of applying Proximity Theory to sustainable MaaS lies in its ability to enhance decision-making by jointly considering both spatial and temporal dimensions within a unified framework. Whereas traditional MaaS platforms optimize journeys primarily on available modes and user preferences, the integration of PT enables dynamic adaptation to transport disruption enhancing resilience. This approach allows platforms to assess not only the geographical closeness of alternative modes but also their temporal availability. Such dual consideration fosters more agile, personalized, and sustainable decision-making, ultimately improving user experience through reduced delays, enhanced coordination, and more effective disruption management.

From the literature review and analysis, this study offers several fundamental insights. First, balanced proximity dimensions enhance collaboration among transport stakeholders, strengthening resilience, adaptability, and user-friendliness during transport disruptions. Second, high cognitive and social proximity between users and providers builds trust, improves communication, and maintains satisfaction even under challenging conditions. Third, proximity dimensions are interdependent and evolve dynamically, meaning they can be deliberately cultivated to reinforce system resilience. Fourth, the evolution of MaaS, from MaaS 1.0 (journey planning), to MaaS 2.0 (decision support), and MaaS 3.0 (integration of sustainability), demonstrates its growing alignment with user expectations and public policy goals. Fifth, the success of MaaS depends not only on technological integration but also on effective stakeholder coordination, for which proximity theory offers a valuable perspective. Sixth, the most resilient MaaS systems should combine proactive and reactive disruption management strategies, with predictive analytics and user-centric design increasingly shaping future developments. Finally, while the application of PT in MaaS remains emergent, it presents significant opportunities for further research, particularly in the integration of AI, long-term resilience, and addressing ethical issues surrounding privacy, transparency, and equity.

Building on these insights, this paper has introduced and operationalized a novel framework for disruption management within sustainable MaaS, extending PT through the novel concept of temporal proximity as a sub-dimension of geographical proximity. The mixed-integer programming model developed here operationalizes these theoretical constructs, providing a practical decision-support tool that optimizes traveler assignments across feasible routes while accounting for delay penalties, transfer and walking limits, arc capacity, crowding effects, and CO2 emissions. Despite the research contributions, the MIP model application has some limitations, as validation has been limited to simulated scenarios, However, by embedding both resilience and sustainability into disruption response, the model demonstrates how theoretical principles can be translated into actionable solutions for MaaS 3.0 platforms. Looking ahead, several research gaps remain. Future work should investigate how proximity dimensions influence long-term system adaptation, how AI and predictive analytics can be harnessed to operationalize functional proximity while safeguarding privacy, and how user engagement can be leveraged to strengthen social proximity through participatory approaches. Addressing ethical challenges, particularly those related to data use, transparency, and equitable access, will be crucial as MaaS continues to evolve into a more data-driven ecosystem.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates the potential of combining proximity-based theoretical insights with advanced optimization modeling to strengthen MaaS disruption management. By embedding multidimensional proximities into both the conceptual framework and the mathematical model, it contributes to building transport systems that are more resilient, sustainable, and user-centered. This work lays the foundation for a new generation of MaaS platforms capable of adapting to disruption with intelligence, fairness, and environmental responsibility, ultimately shaping the future of urban mobility.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.V. and L.V.; Methodology, C.V. and L.V.; Formal analysis, C.V. and L.V.; Investigation, C.V. and L.V.; Writing—original draft, C.V. and L.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by: UID/04708/2025 and https://doi.org/10.54499/UID/04708/2025, of the CONSTRUCT—Instituto de I&D em Estruturas e Construções—funded by Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I.P./MECI, through the national funds.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Lyu, S.; Huang, Y.; Sun, T. Urban sprawl, public transportation efficiency and carbon emissions. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 489, 144652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupprecht Consult. Guidelines for Developing and Implementing a Sustainable Urban Mobility Plan, 2nd ed.; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2019.

- Vale, C.; Vale, L. Integrating Sustainable City Branding and Transport Planning: From Framework to Roadmap for Urban Sustainability. Future Transp. 2025, 5, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, P.; de Barros, A.G.; Kattan, L.; Wirasinghe, S.C. Public transportation and sustainability: A review. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2016, 20, 1076–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachmann, F.R.; Tsakarestos, A.; Busch, F.; Bogenberger, K. State of the art of passenger redirection during incidents in public transport systems, considering capacity constraints. Public Transp. 2024, 16, 419–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.H. A literature review and analysis of the incident command system. Int. J. Emerg. Manag. 2017, 13, 50–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edrissi, A.; Nourinejad, M.; Roorda, M.J. Transportation network reliability in emergency response. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2015, 80, 56–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kriswardhana, W.; Esztergár-Kiss, D. A systematic literature review of Mobility as a Service: Examining the socio-technical factors in MaaS adoption and bundling packages. Travel Behav. Soc. 2023, 31, 232–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheorghe, C.; Soica, A. Revolutionizing Urban Mobility: A Systematic Review of AI, IoT, and Predictive Analytics in Adaptive Traffic Control Systems for Road Networks. Electronics 2025, 14, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wani, S.A.; Pani, A.; Mohan, R.; Bhowmik, B. Digital payment adoption in public transportation: Mediating role of mode choice segments in developing cities. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2025, 191, 104319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutambik, I. IoT-Enabled Adaptive Traffic Management: A Multiagent Framework for Urban Mobility Optimisation. Sensors 2025, 25, 4126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belen-Saglam, R.; Yuan, H.; Heering, M.S.; Ashraf, R.; Li, S. A Systematic Literature Review on Cyber Security and Privacy Risks in MaaS (Mobility-as-a-Service) Systems. Information 2025, 16, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boschma, R. Proximity and Innovation: A Critical Assessment. Reg. Stud. 2005, 39, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heikkilä, S. Mobility as a Service-a Proposal for Action for the Public Administration Case Helsinki; Aalto University: Espoo, Finland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Arias-Molinares, D.; García-Palomares, J.C. The Ws of MaaS: Understanding mobility as a service from a literature review. IATSS Res. 2020, 44, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Association of Public Transport. Mobility as a Service; UITP: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Vitetta, A. Sustainable Mobility as a Service: Framework and Transport System Models. Information 2022, 13, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulley, C.; Nelson, J. How Mobility as a Service Impacts Public Transport Business Models. International Transport Forum Discussion Papers; No 2020/17; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Alam, T. Breaking the Traffic Code: How MaaS Is Shaping Sustainable Mobility Ecosystems. Future Transp. 2025, 5, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audouin, M.; Finger, M. Empower or Thwart? Insights from Vienna and Helsinki regarding the role of public authorities in the development of MaaS schemes. Transp. Res. Procedia 2019, 41, 6–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audouin, M.; Finger, M. The development of Mobility-as-a-Service in the Helsinki metropolitan area: A multi-level governance analysis. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2018, 27, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulley, C. Mobility as a Services (MaaS)–does it have critical mass? Transp. Rev. 2017, 37, 247–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, L.; Yigitcanlar, T.; Paz, A. Barriers and risks of Mobility-as-a-Service (MaaS) adoption in cities: A systematic review of the literature. Cities 2021, 109, 103036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaere, H.; Basu, S.; Macharis, C.; Keseru, I. Barriers and opportunities for developing, implementing and operating inclusive digital mobility services. Eur. Transp. Res. Rev. 2024, 16, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Vaddadi, B.; Sjöman, M.; Hesselgren, M.; Pernestål, A. Key barriers in MaaS development and implementation: Lessons learned from testing Corporate MaaS (CMaaS). Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2020, 8, 100227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leffler, D.; Burghout, W.; Cats, O.; Jenelius, E. An adaptive route choice model for integrated fixed and flexible transit systems. Transp. B Transp. Dyn. 2024, 12, 2303047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauslbauer, A.L.; Verse, B.; Guenther, E.; Petzoldt, T. Access over ownership: Barriers and psychological motives for adopting mobility as a service (MaaS) from the perspective of users and non-users. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2024, 23, 101005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gault, P.; Cottrill, C.D.; Corsar, D.; Edwards, P.; Nelson, J.D.; Markovic, M.; Mehdi, M.; Sripada, S. TravelBot: Utilising social media dialogue to provide journey disruption alerts. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2019, 3, 100062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]