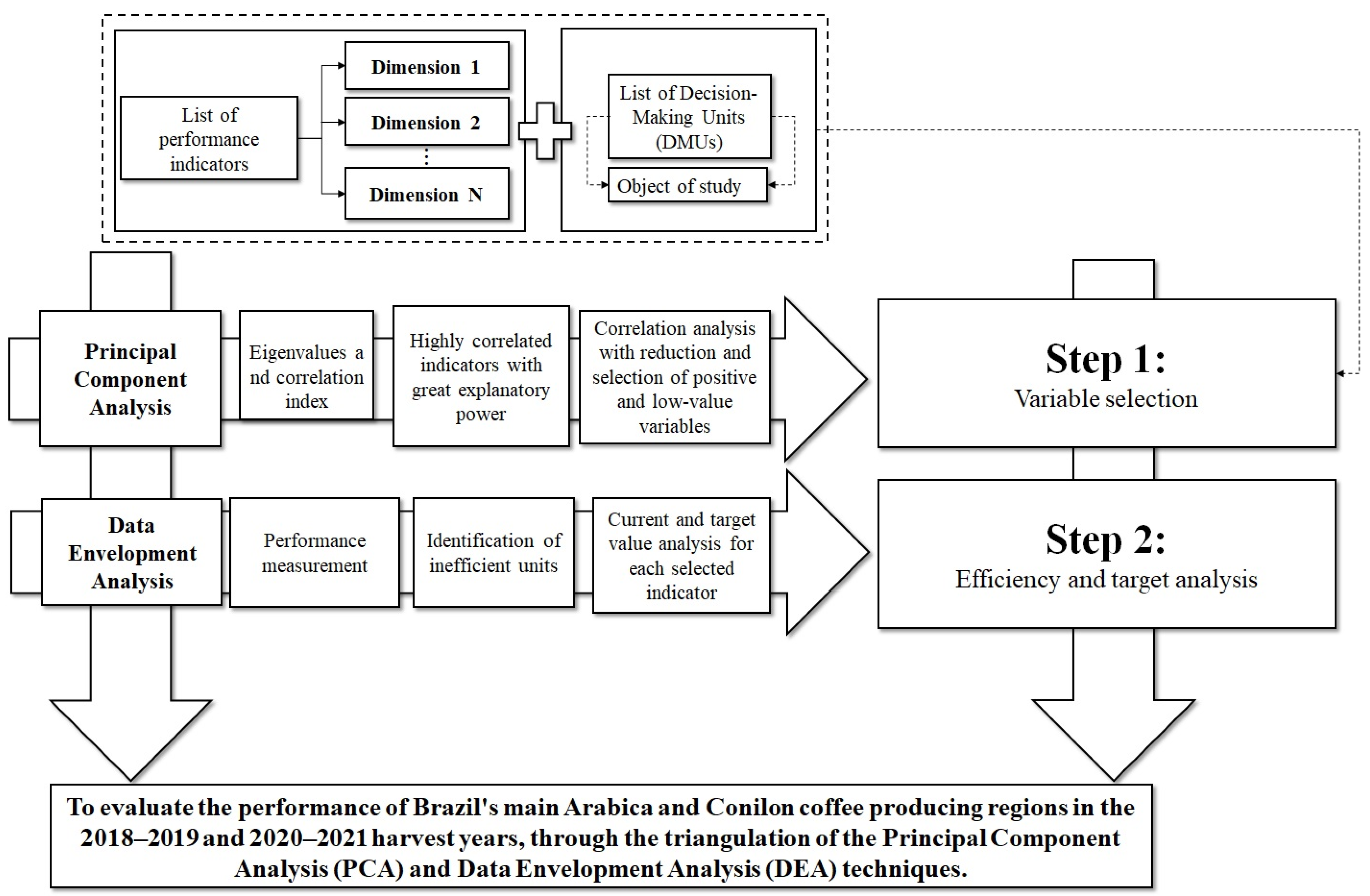

4.1. Selection and Classification of Variables into Inputs and Outputs to Evaluate the Performance of the Main Coffee-Producing Regions in Brazil Based on Principal Component Analysis

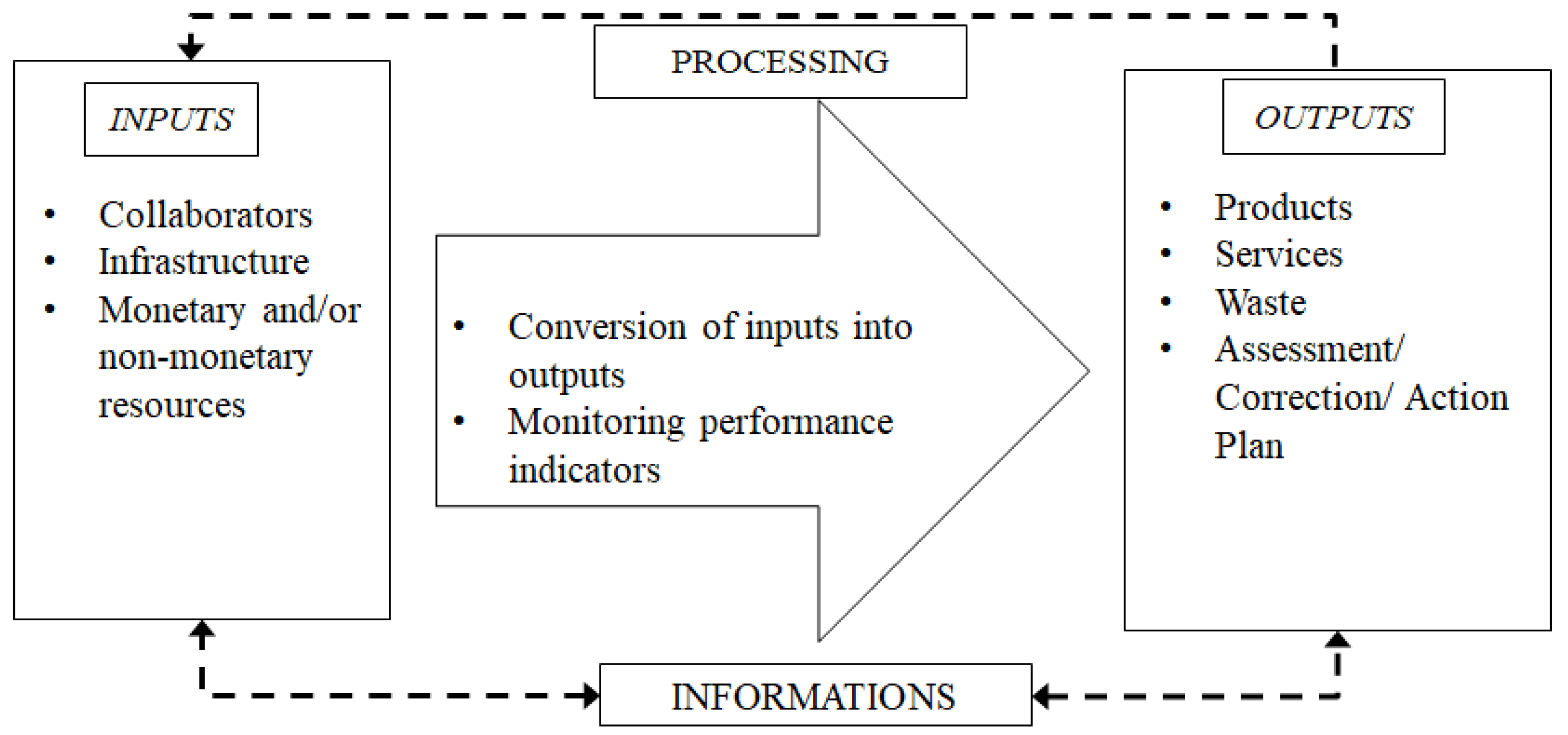

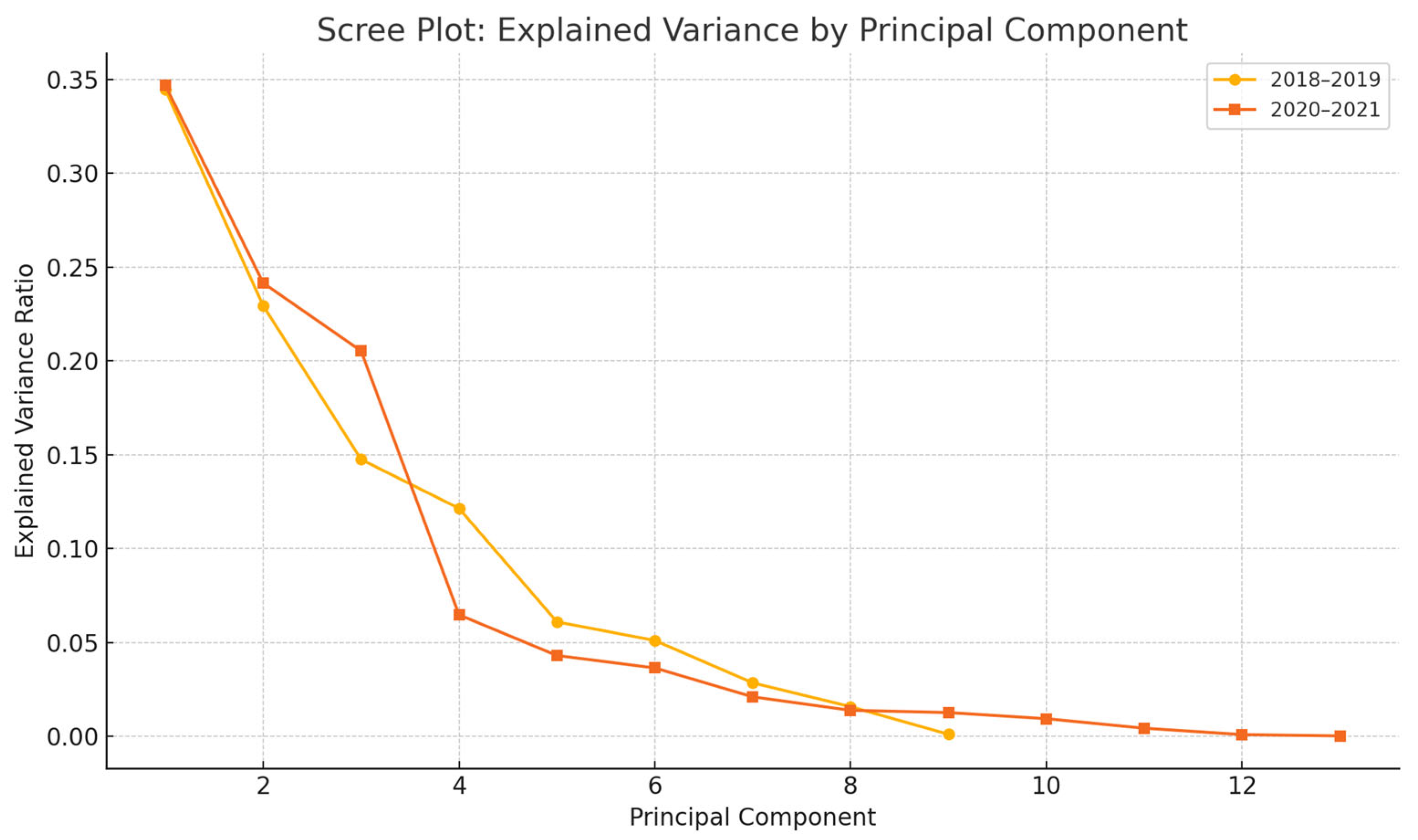

The selection of variables was performed for the 2018–2019 and 2020–2021 harvest seasons using principal component analysis. This technique allowed for the identification of the most representative variables with strong correlations to the principal components (PC1, PC2, and PC3), facilitating the construction of global performance indices for each dimension analyzed (Demographic, Socioeconomic, Agricultural, Certification, and Circular Economy). The selected variables were then classified as either inputs or outputs, respecting the methodological requirements for the subsequent application of data envelopment analysis.

Based on principal component analysis, the variables were selected for the harvest seasons 2018–2019 and 2020–2021. Five original variables were selected for the 2018–2019 harvest season. Tam_prop and Area_cafe showed correlation coefficients of 0.81 and 0.60, respectively, which were the inputs selected for the agricultural dimension. The variables Agua_cons (“Circular Economy” dimension), Rend_prop (“Socioeconomic” dimension), and Qty_M (“Demographic” dimension) had correlation coefficients of 0.88, 0.81, and 0.94, respectively. The absence of the “Certification” dimension is observed, due to the low score achieved by the only variable belonging to this dimension.

A correlation analysis between the variables selected for the 2018–2019 harvest season was carried out according to

Table 4. Low correlation values between the variables were prioritized, with the five original variables being maintained, as they presented correlations lower than 0.76.

The highest correlation occurred between the input Area_cafe and the output Rend_prop, in the order of 75.7%, a fact that favors the application of data envelopment analysis. The original variables Qtd_M, Tam_prop, Agua_cons, Area_cafe, and Rend_prop were selected for the next stage of the data envelopment analysis application. The original variables Qtd_M, Tam_prop, Agua_cons, and Area_cafe were classified as inputs, while the variable Rend_prop included the only output of this analysis. In addition, among the inputs with the highest and lowest correlation coefficients, Qtd_M and Area_cafe, respectively, deserve to be highlighted. For PC1, the original variable Agua_cons showed the highest numerical value for the correlation.

Similarly, for the analysis of the 2020–2021 harvest season, six original variables were obtained, with the variables Rend_tec, Cred_financ, and Area_cafe belonging to the “Agricultural” dimension with correlation coefficients of 0.73, 0.62, and 0.89, respectively. For the “Socioeconomic” dimension, the variable Rend_prop was considered with a correlation of 0.94. For the “Circular Economy” dimension, the variables QtdInsum_prod and AdOrgan_prod were considered, with correlations of −0.61 and 0.81. In this case, the “Demographic” and “Certification” dimensions were absent, since their variables did not present sufficiently high correlations for the three principal components addressed. Consequently, three dimensions were considered for the analysis of the 2020–2021 harvest season from the perspective of data envelopment analysis.

Subsequently, an analysis of the correlations between the variables themselves was developed for the 2020–2021 harvest season to reduce the volume of inputs and outputs covered, as shown in

Table 5. In this context, six variables with correlations lower than 83% were selected.

The input Area_cafe showed a strong correlation with the output Rend_prop again, in the order of 82%. Therefore, the original variables Area_cafe, Cred_financ, AdOrgan_prod, QtdInsum_prod, Rend_prop, and Rend_tec were selected. In this context, global performance indices were defined based on the analysis of correlations and eigenvectors of the selected original variables and their respective components (PC1, PC2, and PC3).

Table 6 represents the global performance indices generated from the variables highly correlated with PC1, PC2, and PC3, considering the 2018–2019 harvest season.

According to

Table 6, based on the values recorded by the eigenvectors and correlations of the original selected variables, it was possible to create four performance indices for the analysis of the 2018–2019 harvest season. An index was then developed for the Qtd_M, which was highly correlated to PC2, one for the inputs selected for PC1 (Water_cons and Tam_prop), one for the input Area_cafe, which was most correlated to PC3, and one for the only output considered in this analysis (Rend_prop), belonging to PC1.

For 2020–2021, the analyses were replicated so that six global performance indices were obtained from variables highly correlated with PC1, PC2, and PC3, as represented in

Table 7.

As shown in

Table 5, a performance index was created for each variable addressed. This is justified, as an input and output were included in each performance dimension, which made it unfeasible to combine these original variables to generate the indices to respect the requirements for applying data envelopment analysis, that is, the output-oriented BCC model.

4.2. Application of Data Envelopment Analysis for Efficiency Assessment

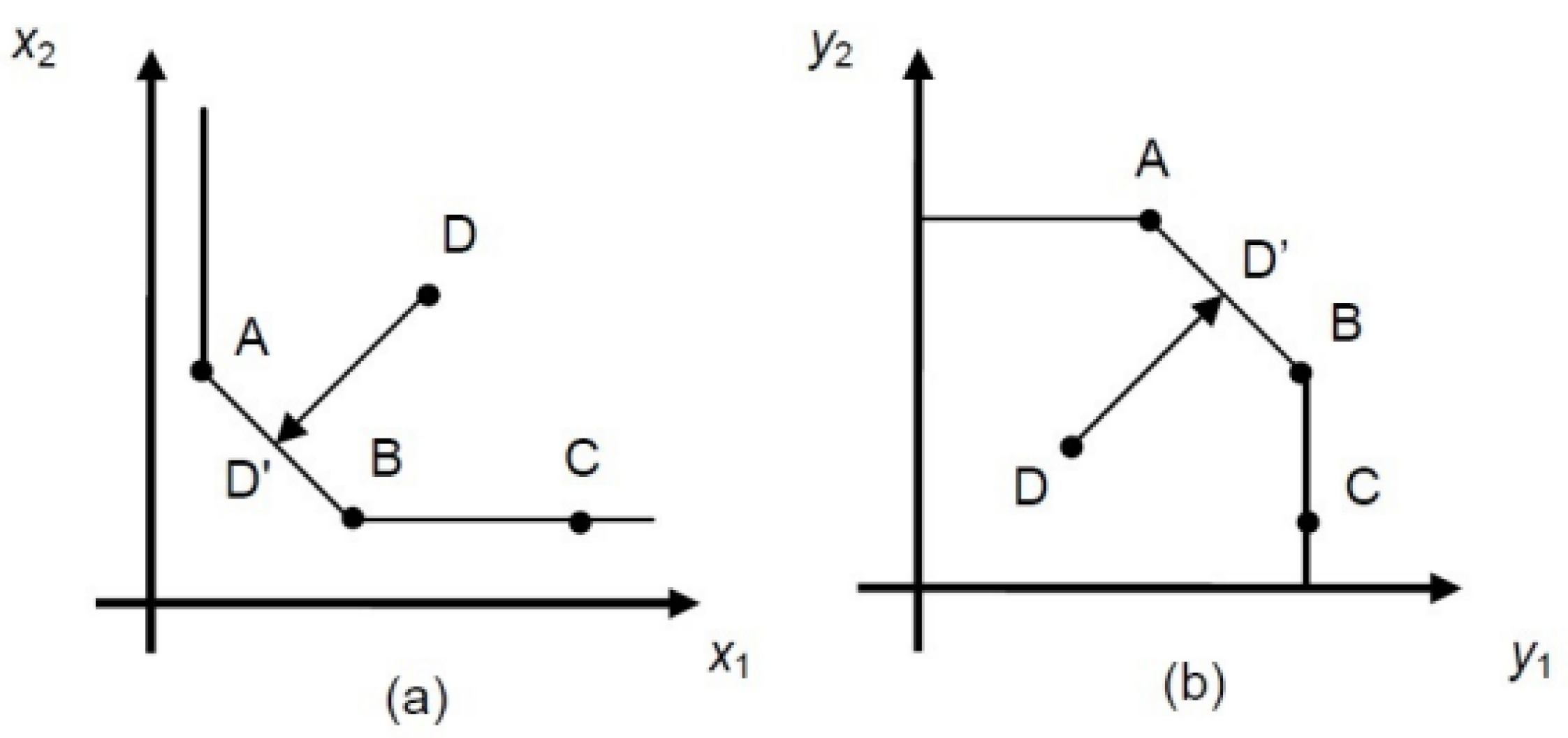

Data envelopment analysis is a widely used non-parametric method for evaluating the relative efficiency of decision making units (DMUs) when multiple inputs and outputs are involved. In this study, an output-oriented BCC model was applied to measure pure technical efficiency among coffee producers. The model’s flexibility enabled the separation of scale efficiency from technical efficiency, which is particularly relevant in heterogeneous production systems such as those found in Brazil’s coffee-producing regions.

Efficiency analysis from the perspective of Banker and Chang’s super-efficiency model (Banker, Chang, and Zheng, 2017) allowed for the identification of sampling units with false efficiencies (outliers), that is, those that exceeded the limit stipulated for the 120% efficiency frontier. Therefore, only producers 1, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 12, 13, 14, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 23, 26, 27, 28, 29, 32, and 33 were considered for the efficiency analysis of the 2018-2019 harvest season, and producers 2, 3, 4, 10, 11, 15, 21, 22, 24, 25, 30, and 31 were eliminated; together, they represent 12 of the 33 sampling units initially considered, or 36.3%.

This analysis allowed for the identification of inefficient sampling units, specifically, six producers in the 2018–2019 harvest season and nine producers in the 2020–2021 harvest season. Although the original variables analyzed in these two years do not coincide, it is worth highlighting the drop in general efficiency when moving from one harvest season to the next, as a function of climatic, economic, and public health aspects. At this stage of the study, the synthesis of targets for inputs and outputs in these units is emphasized as a way of guiding these units towards reestablishing their efficiencies.

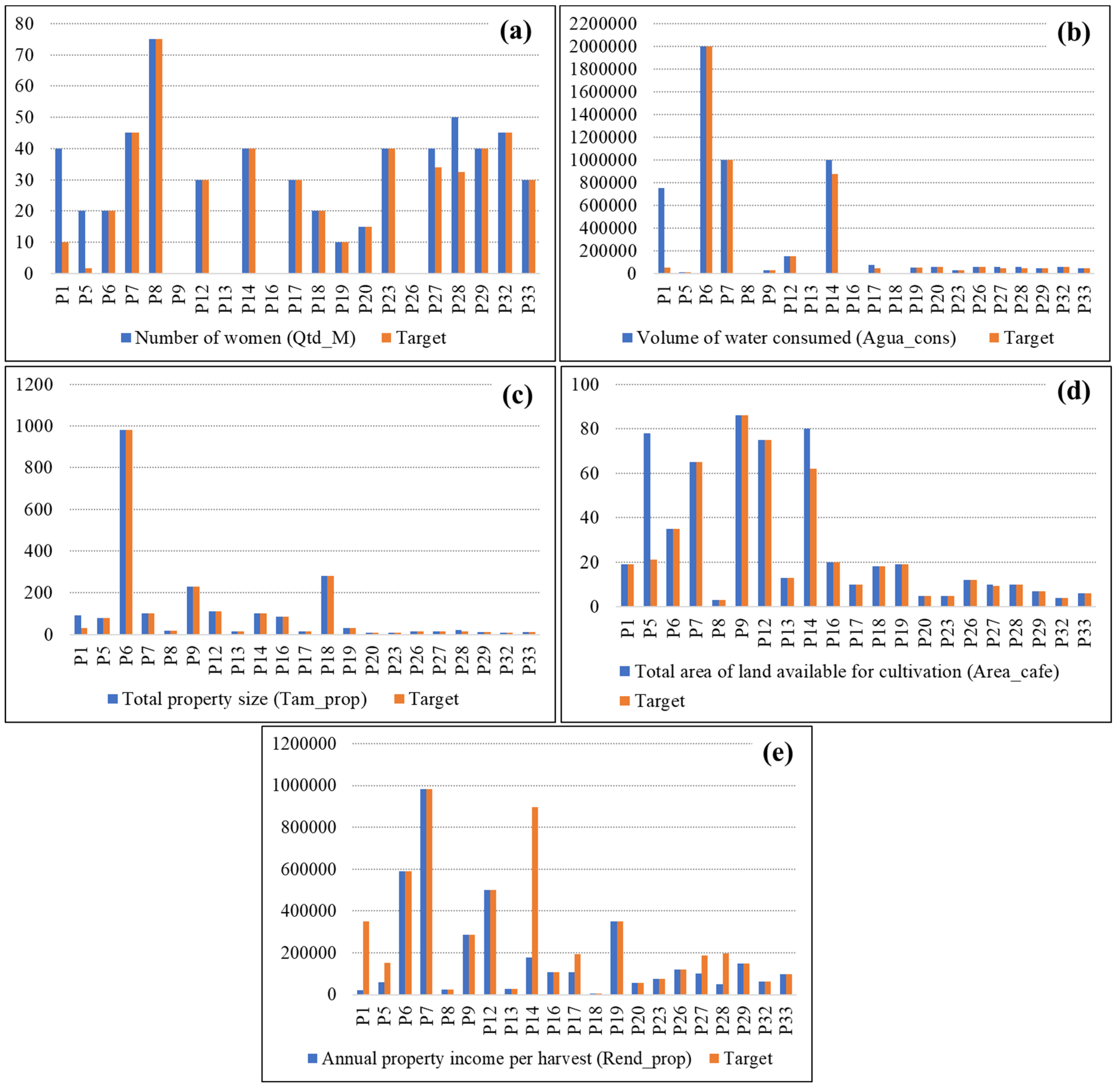

Figure 5a–e presents in detail the targets for each sampling unit for the variables covered in the 2018–2019 harvest season.

Figure 5a corresponds to the variable number of women (Qtd_M) of the “Demographic” dimension, which was highly correlated with PC2. Thus, it was possible to develop the

Labor Performance Index. Hiring labor is an important step in ensuring property efficiency, since the incorporation of the manual cultivation system favors the achievement of a higher level of product quality and, above all, an increase in annual revenue, as quality is directly associated with better product prices.

Only 4 of the 21 inliers did not present values coinciding with the targets presented for the variable Qtd_M. It is recommended that around 81% of these inliers keep their values constant in this variable (Qtd_M) to maintain efficiency in this input. In the case of inefficient producers, they corresponded to inliers 1, 5, 27, and 28. In these cases, it is suggested that there are reductions in the number of women in the order of 75%, 91.4%, 15%, and 35%, respectively. This fact contradicts the principles of gender equality for production activities in coffee production, since there was a predominance of men in various activities in these sampling units. However, from the perspective of reducing labor costs, these measures become relevant to achieving better efficiency scores.

The global performance index formed by the inputs total property size and volume of consumed water corresponded to the

Performance Index in the preservation of water resources, as shown in

Figure 4b,c. These inputs were more correlated to PC1 and belong to the “Agricultural” and “Circular Economy” dimensions, respectively. Property size is a variable that, in isolation, does not reflect the situation of a producer in terms of the overall efficiency achieved, making it necessary to monitor other indicators, such as production capacity, area destined for coffee cultivation, property income, effective operating costs, among others.

Productors 1 and 28 did not achieve the efficiency required for the Tam_prop input, and it was recommended to reduce this number by 67.4% and 25% of their territorial volumes, respectively. This measure makes it possible to increase environmental preservation areas, reestablish virgin forests in degraded areas, as well as conserve water resources in these areas and existing fauna. Moreover, it leads to the reduction in productive land maintenance costs and benefits the creation of a more efficient organizational culture focused on increasing yield, since this aspect is not directly linked to the size of each property.

The variable volume of consumed water contributes to the results of this study by addressing one important dimension for the field of sustainable development from the perspective of the “Circular Economy” dimension. The conscious consumption of water resources through the reduction in waste, treatment, and reuse by producers guarantees better operating conditions for the property during drought periods.

According to

Figure 5b, producers 1, 14, 17, 27, and 28 were inefficient regarding the performance of this input (Agua_cons). Therefore, it is recommended to reduce this consumption by 93.3%, 12.4%, 36.6%, 23.3%, and 22.9%, respectively, as a strategy for reaching the efficiency frontier in these sampling units. It is interesting to highlight producer 1, who achieved the highest percentage of the suggested reduction in this input and, above all, was the most inefficient sampling unit of the 21 units considered. This indicates the possible relationship and contribution of this input (Agua_cons) with the continuous improvement of the pure technical efficiency of these producers. It is emphasized that the satisfactory performance of this index supports the consideration of measures to preserve and reduce the consumption of water resources in these units.

However, reducing these numbers is a difficult measure to implement by some of these producers due to their dependence on irrigation systems. At this moment, the occurrence of a migration of producers to automated irrigation models at the end of this harvest season is accentuated, even though the longest drought observed was recorded in the next harvest season (2020–2021). This reveals the concern of these inliers regarding the guarantee of their plantations to minimize the expected impacts related to climate change. Finally, water reuse and treatment practices are still almost non-existent among the majority of sampling units, indicating a gap to be explored.

The index related to the input “Total land area available for cultivation” made it possible to create the

Performance Index in the geographical distribution of production, as represented in

Figure 4d. It is expected that this index will favor the discussion on leveraging the performance of inefficient producers regarding the areas used on their properties for planting coffee. This is the only variable that was highly correlated with PC3, belonging to the “Agricultural” dimension.

Initially, this index also favored secondary analyses relating to the productive capacity of the sampling unit compared with the values achieved in the variable Tam_prop. It can be observed that there were only four inefficient producers in this input, namely, producers 5, 14, 17, and 27, so that they must reduce these areas by 73.1%, 22.4%, 0.2%, and 6%, respectively, to achieve efficiency. These inefficient producers for the variable Area_cafe presented values coinciding with the targets for the variable Tam_prop. This reveals a reduced current production capacity for these sampling units, which results in a greater volume of production costs. Therefore, a reduction in the number of Area_cafe would mean an increase in this productive capacity, since the level of resources applied to production would be maintained.

Regarding the only output considered in this analysis, the variable Rend_prop, made it possible to generate the

Economic Performance Index based on property gross income, as shown in

Figure 5e. In addition, it was a variable belonging to the “Socioeconomic” dimension, which was highly correlated with PC1. Consequently, the consideration of a strictly economic variable strongly contributes to understanding the production reality of each sampling unit.

Based on the values presented in

Figure 5e, the inefficient producers in terms of performance in the output Rend_prop were inliers 1, 5, 14, 17, 27, and 28. It is suggested that they create internal conditions on the property to increase their income in the order of 1490.9%, 150.3%, 407.2%, 82.1%, 85.1%, and 296%, to reach the efficiency frontier. In the case of sampling units 1, 14, and 28, they obtained the largest gaps between the actual and target values, indicating greater inefficiency in this output. However, it must be considered that a producer’s gross income is linked to the productive capacity of their property, which depends on the variable Area_cafe, for example, among other resources, and the price paid to the producer, which is influenced by factors external to production, such as economic and environmental variables and crisis scenarios, among others.

Therefore, the ideal configuration for efficiency in this index corresponds to maximizing the income of each sampling unit, so that the generation of greater income brings conditions for the structural and productive improvement of these inliers. Furthermore, the relationship between this output and its targets is inverse to the inputs, given the methodology of the output-oriented BCC model. In other words, at this moment, we seek to maximize output where the targets present a higher value.

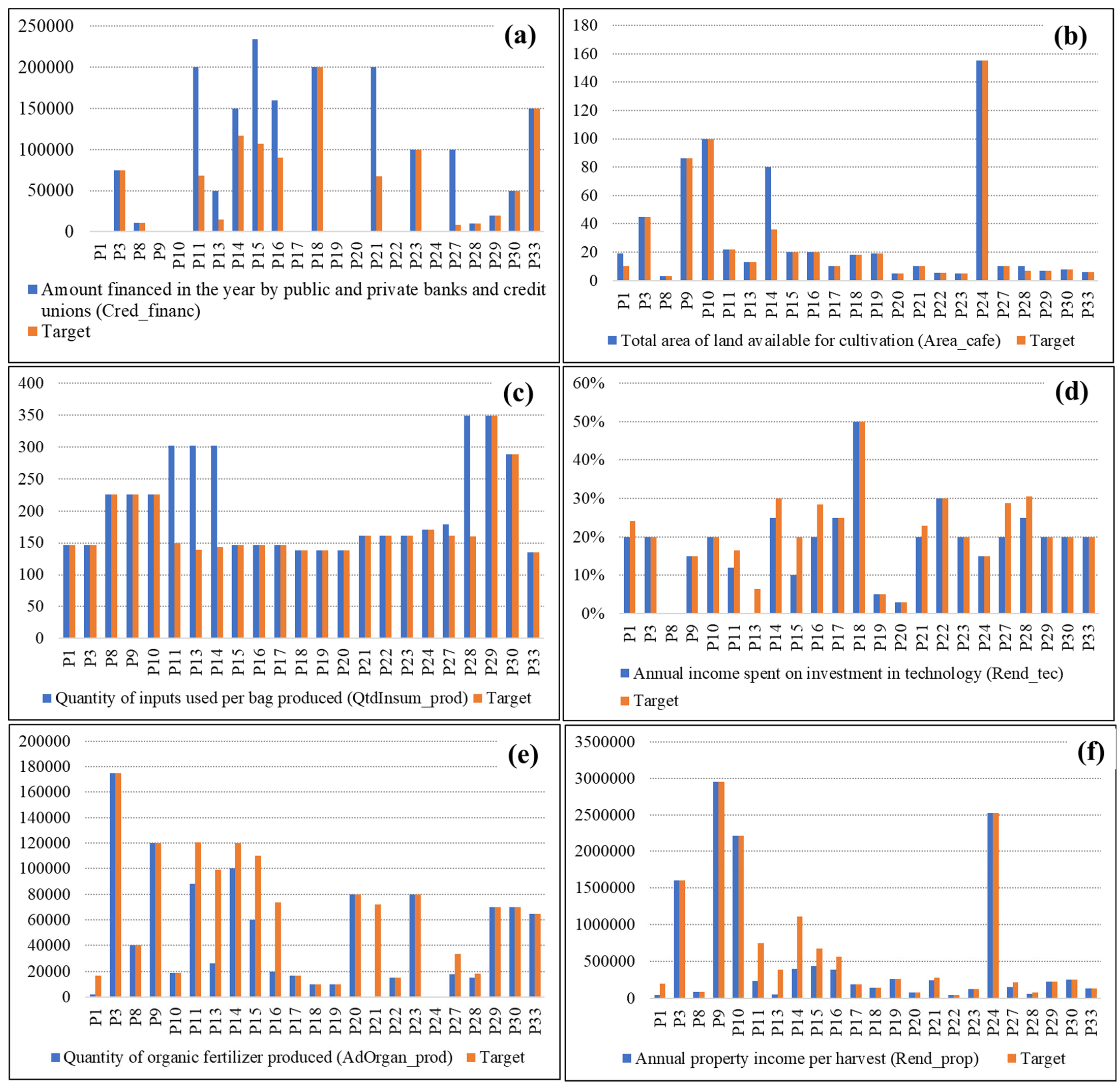

Similarly,

Figure 6a–f presents in detail the targets for each sampling unit for the variables covered in the 2020–2021 harvest season. The performance index resulting from the input “Amount financed in a year by public, private banks and credit cooperatives” made it possible to create the

Performance Index regarding dependence on financial agents, as shown in

Figure 6a. This index aids in understanding the economic crisis scenario experienced by producers this harvest season, where credit support was essential for some producers to maintain activities on their properties. In addition, this input represents a variable highly correlated to PC3 and belongs to the “Agricultural” dimension.

Therefore, producers 11, 13, 14, 15, 16, 21, and 27 did not reach the values stipulated by the targets for the input Cred_financ, being considered inefficient in this aspect. It is recommended that a reduction in the volume of financed credit be carried out by 65.9%, 70%, 22.2%, 54.1%, 43.8%, 66.4%, and 91.3%, respectively, in these inliers, to reach the efficiency frontier. Furthermore, among the inefficient sampling units, producers 13, 21, and 27 stand out, with the largest reductions to be made for this input. However, even with the large contributions made by these sampling units, they still maintained low production capacities and reduced economic returns.

On the other hand, 70% of these inliers were efficient in terms of the value obtained in input Cred_financ, with emphasis on sampling unit 18, which presented the highest value, and units 1, 9, 10, 17, 19, 20, 22, and 24, which did not use credit during the analysis period. The acquisition of credit can mean an increase in costs and indebtedness for producers, especially in times of climate and economic crises, as seen in this harvest season. The acquisition of this credit has been practiced as an investment strategy in technologies and production systems by some producers. However, they still represent shallow and inefficient initiatives, as observed in inliers 13, 15, and 21.

From the variable “Total area of land available for cultivation”, which showed a high correlation with PC1 and represents an input in the “Agricultural” dimension, the

Performance Index in the geographical distribution of production was developed, as shown in

Figure 6b. This variable and the output Rend_prop were the only variables addressed in both the 2018–2019 and 2020–2021 harvest seasons.

According to the data discussed in

Figure 6b, only producers 1, 14, and 28 showed inefficiency related to the variable Area_cafe. Therefore, to become efficient, it is suggested to reduce this number in each unit in the order of 45.4%, 55%, and 31%, respectively. Producer 14 stood out for presenting the greatest need for reduction, a fact that can be justified by their low production capacity and high input costs. On the other hand, 87% of these inliers were successful in this input, reaching the stipulated targets. It is considered that the best configuration of this index refers to properties with high production capacity scores and low costs involved in production.

It is noteworthy that the majority of efficient sampling units (69.5%) in this input present reduced values, below 40 hectares. However, there were still efficient producers, such as inliers 9, 10, and 24, with higher levels for the same number, which were above 80 hectares cultivated. In these cases, these are sampling units focused on the continuous improvement of their production through investments in sustainable technology and cultivation systems and the use of an appropriate proportion of organic and chemical fertilizers.

In this opportunity, the alignment of resource consumption and the area used for cultivation is extremely important for maintaining good levels of production capacity and reducing costs on the property. In the case of inefficient inliers, they presented high values for variables related to the volume of water and fossil fuels consumed. However, the fact that they also had reduced production capacities does not justify the high consumption of other resources, representing a production bottleneck to be corrected mainly in sampling units 1, 14, and 28.

Based on the variable “Quantity of inputs used per bag produced”, it was possible to create the

Performance Index in reducing chemical inputs, according to

Figure 6c. This index collaborates to mitigate the impacts of cultivation methodologies based on the use of agrochemicals, encouraging their minimization and replacement with sustainable forms of management. The variable QtdInsum_prod included the “Agricultural” performance dimension and showed a high correlation with PC2.

The analysis of

Figure 6c indicates that only inliers 11, 13, 14, 27, and 28 were inefficient regarding the values obtained for the variable QtdInsum_prod. It is then suggested that reductions be made in these sampling units for this number in the order of 50.3%, 53.7%, 52.4%, 9.9%, and 54.2%, respectively. The excessive use of chemical inputs represents a significant portion of the costs involved in production, especially for this harvest season (2020–2021), in which consecutive increases in fertilizer prices were recorded. A favorable scenario for this index is the achievement of minimum levels for QtdInsum_prod to strengthen the sustainable dynamics of coffee production in Brazil, encouraging the search for new agroecological alternatives to supplement the terrestrial substrate.

Approximately 78.3% of these inliers were efficient for the variable considered (QtdInsum_prod). Around 72% of these producers spent less than BRL 170.00/bag produced on inputs. Considering the dynamics of prices paid to producers, these units presented higher net margins than the others. An increase in the proportion of organic fertilizer/chemical fertilizer used on the property was observed between 2018–2019 and 2020–2021 for most of the inliers considered.

The output “Annual income spent on investment in technology” served as the basis for the development of the

Innovation Performance Index for the insertion of sustainable production models, as shown in

Figure 6d. It is considered that this is a variable belonging to the “Agricultural” dimension, which was highly correlated to PC2, but the objective now is to maximize it according to the output-oriented BCC model. Thus, as shown in

Figure 6d, producers 1, 11, 14, 15, 16, 21, 27, and 28 were inefficient regarding the output Rend_tec, and in these cases, it is recommended to increase investments in this segment in the order of 20.8%, 36.8%, 20%, 100%, 42.2%, 14.6%, 43.9%, and 22.4%, respectively. It is understood that the ideal scenario for this index is reflected by high percentages of gross income invested exclusively in technologies within the scope of sustainable production.

Furthermore, there was a predominance of these inliers in the establishment of technologies related to the production of clean energy. This fact is related to the variables linked to the consumption of fossil fuels and the electricity consumption of properties. This is justified, as the production of clean energy means an alternative to reducing costs for producers, basically requiring an initial investment for its setting, with the possibility of storing energy for future use. In regard to efficient producers, in this aspect, they represented 65.2% of the sample units considered. Moreover, considering the target values for inefficient units, it can be inferred that producers have constantly made efforts to incorporate good production practices, especially those aimed at the circular economy and sustainability.

The study of the output “Quantity of organic fertilizer produced” showed that it was highly correlated to PC3 and belonged to the “Circular Economy” dimension, which made it possible to create the

Performance Index in the reinsertion of waste generated in production, as shown in

Figure 4e. This index is of great importance in analyzing units regarding their commitment to sustainable production standards.

Based on

Figure 6e, inliers 1, 11, 13, 14, 15, 16, 21, 27, and 28 were inefficient for AdOrgan_prod. Therefore, it is suggested that these inliers increase the value of this variable in the order of 14,704.77, 32,375, 73,000, 20,000, 49,872.21, 53,690.79, 72,309.94, 15,617.64, and 3365.48 kg, respectively, to achieve the efficiency related to this output. This period highlights an opportunity for these producers to be able to establish efficiency in their properties. In some cases, it was observed that producers ended up resorting to purchasing organic material from third parties to fulfill their commitments with their plantings this harvest season. This is because there were production losses in some regions affected by undesirable weather events. However, it was still a high cost–benefit measure.

Regarding efficient producers, namely, inliers 3, 8, 9, 10, 17, 18, 19, 20, 22, 23, 24, 29, 30, and 33, representing around 61% of the sampling units, have an organic fertilizer consumption of up to 175,000 kg on their properties. On the other hand, producer 24 was efficient, even though they did not use organic fertilizers in their production. This is because it is a sampling unit with a planted area greater than the average of the inliers considered, besides the use of chemical inputs in the appropriate amount and time, yielding high revenue for the producer. Furthermore, this unit considers the use of renewable energy and the treatment of waste generated throughout production, which characterizes the sustainable initiatives in this inlier.

Finally, the output “Annual property income per harvest”, which was highly correlated to PC1 and belonged to the “Socioeconomic” dimension, allowed for the development of the

Economic Performance Index based on the property gross income, as shown in

Figure 6f. Thus, the aim is to generate economic information about the performance of the sampling units analyzed.

Given what is shown in

Figure 6f, the inefficient sampling units included producers 1, 11, 13, 14, 15, 16, 21, 27, and 28, and activities are recommended to increase their income on these properties in the order of 332.7%, 211.7%, 591.9%; 180.6%, 53.3%, 42.2%, 14.6%, 43.9%, and 25.6%. Furthermore, around 61% of these producers were efficient in terms of performance in the variable Rend_prop, showing the effort made by the majority of these producers to achieve satisfactory prices and high production capacity.

For this index, the scenario of maximizing the revenue and production capacity of each sampling unit stands out as the best existing configuration. Sampling units 9 and 24 had the highest values for this output. However, they were inliers with a larger planted area, were equipped with irrigation systems, and were characterized by the incorporation of a reduced proportion of organic/chemical fertilizers. In the case of producer 9, the fact that the coffee produced has certification stands out, which raises the commercialization standard of the product on the national and international markets.

In this context, increases in coffee prices were recorded for the previous harvest season for the 12 producing regions in the order of 56% for Cacoal-RO, 58% in Itabela-BA, 81% in Capelinha-MG, 80% in Franca-SP, 106% in Guaxupé-MG, 76% in Manhumirim-MG, 87% in Caconde-SP, 88% in Santa Rita do Sapucaí-MG, 63% in Londrina-PR, 66% in Poço Fundo-MG, and 63% in Brejetuba-ES. Given this, the highest percentage increases occurred in municipalities in the Southeast region, specifically in the states of São Paulo and Minas Gerais, which hold the majority of the country’s coffee production volume. Coincidentally, these two states were the most affected by climate-related issues, with production losses, producer debt, and workforce reduction.

Although the efficiency results derived from the data envelopment analysis model included recommendations, such as reducing the number of female workers in certain production units, it is essential to interpret these outputs within a broader ethical and developmental context. Such numerical targets should not be viewed as prescriptive actions but rather as indicators of structural inefficiencies that may reflect disparities in labor organization or resource allocation. This study does not support any reduction in women’s participation in agricultural activities. Instead, it recognizes the importance of fostering inclusive and equitable labor strategies aligned with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, particularly SDG 5 (Gender Equality). Therefore, the interpretation of efficiency results must be guided by ethical principles, reinforcing the role of women in sustainable agribusiness and promoting strategies that improve performance while upholding social responsibility and equity.

The performance indices developed in this study serve both operational and strategic purposes. At the farm level, these indices help producers identify specific areas for improvement—such as optimizing water use, enhancing income generation, or increasing the use of organic fertilizers—enabling more informed resource allocation. Because the indices are based on objective variables and normalized data, they can be easily integrated into farm management practices and training programs. At the policy level, the indices allow for regional benchmarking and the identification of systemic inefficiencies, supporting targeted public interventions and incentive programs. Therefore, the indices are not merely analytical tools but are practical instruments for continuous performance improvement across scales. This study is relevant to major players in the global coffee industry. Price fluctuations or changes in international demand can impact both Brazil and other coffee-producing countries. Additionally, droughts and pests are global challenges faced by the sector. Finally, pressure for sustainable practices affects all producers.