Abstract

Virtual museums are increasingly adopted to sustain public engagement with cultural heritage, yet the mechanisms through which virtual exhibition experiences motivate on-site visitation remain underexplored. Drawing on the Stimulus–Organism–Response (SOR) framework and extending the Information Systems Success Model (IS Success Model), this study proposes and tests a psychological pathway linking virtual museum experience quality to offline visiting intention. Using the official website of the Sanxingdui Museum as the empirical context, we surveyed 467 users in China who explored the virtual exhibition but had never visited the museum in person. Virtual exhibition experience quality was operationalised through five dimensions: information quality, system quality, perceived interactivity, perceived authenticity and perceived enjoyment. Perceived cultural value and cultural identity were specified as mediators. Structural equation modelling revealed that higher levels of virtual exhibition experience quality significantly enhanced perceived cultural value and cultural identity. Perceived cultural value, in turn, positively predicted cultural identity, and both constructs were positively associated with intention to visit the physical museum, with a significant sequential mediation from experience quality to offline visiting intention via perceived cultural value and cultural identity. These findings clarify how virtual heritage platforms can foster cognitive appreciation and emotional identification that translate into real-world visitation, offering guidance for designing sustainable digital pathways to long-term engagement with cultural institutions.

1. Introduction

The rapid advancement of digital technologies has enabled virtual museums to become vital platforms for cultural dissemination and public education [1,2]. By deploying virtual reality (VR), augmented reality (AR) and 3D modelling, they transcend spatial and temporal constraints and broaden inclusive access to heritage content [3,4]. This transformation not only improves accessibility and efficiency in the transmission of cultural content but also allows users to engage in more personalised and diverse ways [5]. From a sustainability perspective, these affordances align with goals of equitable cultural participation, long-term heritage stewardship and resilient audience development [6,7,8].

Previous studies have widely recognised the positive role of virtual museums in cultural communication, cognitive support and user engagement [9,10,11]. Many have adopted theoretical models such as the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) and the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) to examine factors such as system usability, adoption intention and user satisfaction [12,13,14]. While this work has advanced system design and functional evaluation, it largely foregrounds utilitarian beliefs and technology use. Consequently, it offers limited insight into how virtual experiences support meaning making and identity formation, and how these psychological processes translate into sustained cultural participation, particularly the intention to visit physical heritage sites.

Despite substantial progress, several gaps remain salient from a sustainability perspective. First, the mechanism by which specific experiential affordances (e.g., interactivity, authenticity, and enjoyment) cultivate perceived cultural value and cultural identity is underspecified; most studies infer these constructs but do not model them as central outcomes. Second, the transformation from online experience to offline visiting intention is rarely treated as a primary behavioural endpoint, with research more commonly focusing on the continued use of digital platforms. Third, empirical work that jointly examines perceived cultural value and cultural identity as sequential mediators within a museum-specific framework remains scarce. Although some studies have highlighted the role of immersive storytelling in enhancing exhibition appeal [15], many continue to prioritise user satisfaction, overlooking the synergistic interplay among cognition, emotion, and behaviour. This issue is particularly salient in digital heritage museums, where exhibits are embedded with rich symbolic and historical meanings and effective communication depends on multi-sensory engagement and spatial narrative design [16,17].

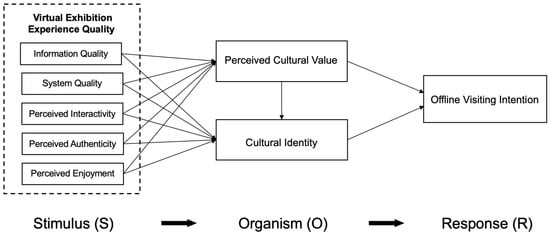

To address these gaps, this study integrates the SOR framework with the IS Success Model to explicate the mechanism linking online experience to offline visiting intention [18,19]. Unlike much of the previous research focusing on technology acceptance, we centre on meaning-making and cultural identity. We conceptualise experience quality as the external stimulus (comprising information quality, system quality, perceived interactivity, perceived authenticity, and perceived enjoyment); perceived cultural value and cultural identity as organismic states reflecting users’ cognitive appraisal and affective identification; and offline visiting intention as the behavioural response. This conceptualisation specifies a value-and identity-centred pathway through which virtual heritage experiences cultivate enduring participation.

Beyond advancing theoretical understanding, this study speaks directly to the sustainability of cultural-heritage engagement. Cultural institutions increasingly rely on digital channels to reach distant audiences and maintain interest when physical access is constrained. Understanding how virtual exhibition experiences can foster perceived cultural value, reinforce cultural identity and motivate offline visitation provides practical guidance for designing museum platforms that do more than inform: they build durable relationships with audiences. In this sense, the present work identifies how virtual museums can serve as scalable entry points into continuing cultural participation, supporting the ongoing social relevance of heritage institutions.

Specifically, it pursues four objectives:

- To define and model virtual exhibition experience quality as a multidimensional stimulus.

- To examine how these dimensions shape perceived cultural value and cultural identity.

- To assess how perceived cultural value and cultural identity influence offline visiting intention.

- To test whether perceived cultural value and cultural identity sequentially mediate the relationship between experience quality and offline visiting intention.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Museum, Virtual Museum, and Visitor Experience

Museums have traditionally been key sites for preserving and sharing cultural legacies, including material artefacts and intangible practices. They have long functioned as custodians of cultural memory, providing spaces for education, knowledge dissemination, and aesthetic appreciation. In its 2022 definition, the International Council of Museums (ICOM) described museums as permanent, non-profit institutions that operate for the benefit of society by engaging in the research, collection, conservation, interpretation, and exhibition of heritage in its material and immaterial forms [20]. These institutions are characterised as public, inclusive, and accessible, promoting diversity and sustainability while offering opportunities for education, enjoyment, critical reflection, and the sharing of knowledge. This updated perspective gives greater prominence to values such as inclusivity, accessibility, sustainability, and active community involvement, indicating a conceptual shift from conventional, object-centred displays to interactive and participatory spaces [21]. As technological, social, and cultural landscapes evolve, museums are increasingly adopting flexible and interactive strategies for cultural engagement [21,22].

The virtual museum, also referred to as the online museum, has become a key manifestation of digital transformation within the museum sector [23]. Rather than serving merely as a spatial extension of physical museums, it represents a fundamentally new paradigm for disseminating cultural resources through digital technologies [24]. Leveraging official websites, mobile applications, and immersive environments, virtual museums transcend spatial and temporal constraints, enhancing the accessibility of cultural services [25]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, they emerged as critical channels for sustaining public engagement [26,27]. According to data from the National Cultural Heritage Administration of China, over 1300 museums launched more than two thousand virtual exhibitions during the 2020 Spring Festival, drawing in excess of five billion views, thereby underscoring the pivotal role of digital exhibitions in the cultural dissemination ecosystem [11].

Compared with traditional on-site visits, virtual museums place greater emphasis on immersion, interactivity, accessibility, and personalisation [27,28,29]. Empirical studies have demonstrated that non-linear, user-driven modes of engagement not only broaden visitors’ cognitive horizons but also foster emotional attachment and self-reflective cultural interpretation [30,31]. Consequently, visitor engagement has shifted from passive information reception towards an active process integrating cognitive processing, emotional resonance, and behavioural response [13,32,33]. While scholars like Wu et al. have made strides by applying models such as ECM and TAM to explain user satisfaction and knowledge acquisition [34], research on the deeper cultural-psychological mechanisms remains relatively limited. This limitation is particularly evident in digital heritage exhibitions, where complex layers of cultural symbolism and historical context present heightened challenges to users’ cognitive processing and emotional engagement [35]. Consequently, there is a pressing need to move beyond utilitarian evaluations to explore how virtual experiences facilitate the transformation from online interaction to offline action through perceived cultural value and identity.

2.2. Perceived Cultural Value and Cultural Identity

Perceived Cultural Value, a key dimension of perceived value, refers to individuals’ subjective assessments of the cultural significance, symbolic meaning, and social function embedded in cultural products, services, or narrative experiences [36,37]. Unlike functional or economic value, Perceived Cultural Value emphasises emotional resonance with cultural content and the affirmation of identity [38,39]. In virtual museum settings, the value is primarily generated through curatorial storytelling, symbolic artefacts, and digitally reconstructed historical scenes [40,41]. Studies have highlighted that immersive storytelling, perceived authenticity, and interactive design are critical factors shaping users’ cultural value perceptions, which in turn enhance emotional engagement and motivation for cultural participation [42].

Cultural Identity is commonly understood as an individual’s internalised affiliation and shared value orientation with a specific cultural community or symbolic structure [43]. It shapes how individuals situate themselves within cultural contexts and plays a crucial role in motivating participation in cultural tourism and museum visitation [44,45,46]. The formation of cultural identity is driven by cognitive and affective processes, including the revisitation of personal and collective histories, the exploration of cultural origins, and the strengthening of identity affiliation [47]. These processes ultimately foster a heightened sense of social connectedness, collective pride, and a disposition toward cultural heritage preservation.

Notably, a growing body of research recognises perceived cultural value as a key psychological antecedent of cultural identity. When users perceive high levels of symbolic meaning in virtual museums, they are more likely to develop emotional connections, which fosters cultural identity and strengthens the motivation to participate in cultural activities [39,48]. Cultural identity in turn predicts a range of behaviours, including tourism preferences, cultural consumption, purchase of cultural and creative products and engagement in heritage dissemination [49,50,51]. For example, He and Wang showed that cultural identity enhances users’ emotional affinity and behavioural intentions toward local culture and its derivatives through familiarity and a sense of belonging [52].

In summary, this study identifies Perceived Cultural Value and Cultural Identity as central mediators that link virtual exhibition experiences to offline visiting intentions. By elucidating the cognitive-affective-behavioural pathways underlying this relationship, the study advances theoretical insight into digital cultural engagement and supports the development of hybrid cultural service models that integrate virtual and physical experiences.

2.3. From Online Experience to Offline Visiting Intention

Virtual museums provide users with distinctive cultural experiences through high-resolution imagery, 3D modelling, and VR/AR technologies, stimulating curiosity and emotional engagement [15,53]. Empirical studies have shown that multisensory stimulation and interactive design in virtual environments can enhance users’ exploratory motivation, aesthetic appreciation and cultural resonance, which in turn foster greater interest in and identification with offline cultural spaces [54,55]. Compared with traditional static promotional methods, virtual museums communicate cultural narratives more effectively through audiovisual integration and contextual immersion, increasing users’ cognitive anticipation and their intention to visit museums in person [56].

Within digital cultural communication, the shift from online engagement to offline participation is a central topic. Virtual cultural experiences function not only as cognitive–emotional bridges connecting users with heritage, but also as potential catalysts for site visits, cultural dissemination and heritage-related consumption [15,57]. Existing studies frequently adopt acceptance-type models such as TAM, UTAUT and the ECM to analyse users’ intentions, focusing on factors such as system usability, perceived ease of use and satisfaction [11,13,58]. Because these frameworks prioritise adoption-related outcomes (e.g., intention to use or continuance), they offer limited leverage for explaining how specific experiential affordances translate into cultural-value construction, identity formation and offline engagement. To make this acceptance-based literature more accessible at a glance, Table 1 summarises representative empirical studies in virtual museum and VR settings.

Table 1.

Previous empirical research on virtual museum.

Building on this literature, and to explicate the internal mechanism linking online experience to offline visiting intention, the present study adopts the SOR framework, focusing on how virtual-exhibition experience quality is translated into perceived cultural value and cultural identity. On this basis, we develop a behavioural pathway model grounded in cultural-psychological perspectives, which posits that virtual-exhibition experience quality influences offline visiting intention indirectly through perceived cultural value and cultural identity. The next section formalises this framework and presents the hypotheses.

3. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

3.1. Theoretical Background

3.1.1. Stimulus–Organism–Response Framework

The Stimulus–Organism–Response (SOR) framework was initially proposed by psychologists Mehrabian and Russell to elucidate how external environmental stimuli ‘S’ affect individual behavioural responses ‘R’ through internal psychological states ‘O’ [19]. The model underscores that behavioural responses do not result directly from external stimuli; rather, they are mediated by internal emotional, cognitive, and attitudinal processes, which together form a sequential causal chain termed ‘stimulus–organism–response’. As a theoretically robust and versatile framework for behavioural prediction, the SOR framework provides a strong foundation for exploring the psychological mechanisms that underlie complex human behaviour [59].

In recent years, the SOR framework has been extensively applied across fields such as tourism experience, immersive media, and consumer behaviour. It has demonstrated particular efficacy in contexts involving virtual reality, digital heritage, and cultural communication, as it helps explain users’ emotional resonance, cognitive processing, and behavioural intentions within immersive technological environments [60,61]. A study by Jiang et al., on digital heritage exhibitions, found that immersive scenes and interactive design function as external stimuli that significantly influence users’ perceptions of cultural value and foster emotional identification with cultural identity [62]. These empirical insights further attest to the theoretical utility of the SOR approach in explaining user engagement within digital cultural communication contexts.

In the context of virtual museums, elements such as exhibition content, system interactivity, and modes of information presentation serve as external stimuli. These stimuli stimulate users’ cognitive engagement with cultural material, as evidenced by their perceived cultural value. Concurrently, they evoke emotional connections to culture, which are reflected in the development of cultural identity. Together, these cognitive and emotional responses constitute the organismic layer of the behavioural process. Consequently, they influence users’ behavioural responses, particularly their intention to engage in offline museum visits.

3.1.2. Information Systems Success Model

The Information Systems Success Model (IS Success Model), developed by DeLone and McLean, serves as a foundational theoretical framework for assessing the effectiveness of information systems and their impact on user behaviour [18]. It has been widely applied across diverse domains such as educational technology, mobile learning, digital tourism, and virtual museums, particularly in explaining how users form experiences within digital environments. For instance, Wu et al. empirically validated the role of information quality in enhancing perceived ease of use and perceived convenience within a digital museum context [11]. Similarly, Wang et al. confirmed that system quality and information quality significantly influence users’ immersive experience and reinforce their sustained engagement with digital cultural heritage platforms [63].

The IS Success Model identifies information quality and system quality as essential determinants of users’ cognitive assessments and behavioural choices. Information quality refers to users’ subjective assessment of the exhibition content in terms of richness, timeliness, and completeness. In contrast, system quality reflects users’ overall appraisal of the platform’s functional clarity, structural organisation, and operational responsiveness. In the context of this study, the virtual museum operates primarily as a self-guided browsing environment, lacking real-time human interaction or curatorial narration. Consequently, the user experience is heavily dependent on the effectiveness of content delivery and the quality of the technological interface. Therefore, this study incorporates information quality and system quality as core stimulus variables in the SOR framework, serving to evaluate the initial impact of virtual exhibition experiences on users’ subsequent responses.

3.2. Hypothesis Development

3.2.1. Quality of Virtual Exhibition Experience and Its Impact on Perceived Cultural Value and Cultural Identity

Within the SOR theoretical framework, the stimulus component denotes external conditions that trigger users’ cognitive and emotional responses. In the context of virtual museums, this study conceptualises the quality of virtual exhibition experience as the primary stimulus, operationalised through five key dimensions: information quality, system quality, perceived interactivity, perceived authenticity, and perceived enjoyment. The first two dimensions, rooted in information systems research, reflect users’ cognitive evaluations of content richness and technological performance. In contrast, the latter three capture users’ subjective perceptions and affective responses elicited in immersive digital heritage settings.

Information quality refers to users’ subjective evaluation of the accuracy, richness, and structural coherence of exhibition content. High-quality information facilitates a more profound understanding of cultural exhibits and supports the construction of cultural meaning [11]. Existing research has shown that well-organised and comprehensive content enhances users’ engagement with cultural knowledge and stimulates curiosity, thereby elevating their perceived cultural value [64]. Moreover, culturally rich and contextually grounded information has been found to strengthen users’ emotional identification with the culture being represented [40].

System quality concerns the technical functioning of the virtual exhibition platform, including interface usability, loading speed, operational stability, and navigational ease [18]. A reliable and user-oriented system reduces users’ cognitive effort, thereby promoting immersive experiences and efficient information processing [65]. In the context of cultural dissemination, seamless system performance ensures sustained engagement with digital heritage content, which in turn enhances users’ cultural understanding and fosters emotional resonance with the exhibited materials [62].

Perceived interactivity denotes the degree to which users actively engage with the system, encompassing interaction frequency, feedback responsiveness, and the level of user control [66]. Studies in tourism have similarly demonstrated a positive correlation between perceived interactivity and users’ perceived value when using tourism-related applications or interactive digital maps [54]. In museum environments, interactive mechanisms such as manipulating three-dimensional virtual artefacts allow for closer engagement with exhibits, ultimately reinforcing perceived cultural value [62].

Perceived authenticity refers to users’ subjective evaluation of how accurately virtual exhibition content reflects real historical and cultural contexts [67]. It encompasses the degree of trust and realism users attribute to the exhibition environment, including the fidelity of artefact reconstructions, the design of exhibition settings, and the overall cultural atmosphere [68]. In tourism studies, authenticity is widely recognised as a key component of technology-mediated cultural experiences. For instance, Khan et al. found that high-quality multimedia content delivered via handheld AR devices in museum settings effectively fulfilled visitors’ needs for contextual understanding and detailed information, thereby encouraging reflection on the meaning and significance of exhibits [69]. Within cultural heritage communication, realistic representations of historical environments and immersive exhibition scenes evoke cultural memory and emotional resonance, which in turn enhance users’ perceived cultural value and reinforce their cultural identity [12].

Perceived enjoyment encompasses the extent of positive affective experiences that arise during users’ interaction with the virtual museum, encompassing feelings such as enjoyment, pleasure, excitement, and novelty [70]. As an immediate form of emotional gratification generated while browsing or exploring the virtual environment, perceived enjoyment has been shown to significantly influence users’ continued engagement with digital platforms [71,72]. Previous research has demonstrated its critical role in multiple contexts, including e-commerce, interactive gaming, and tourism-related mobile applications [13,73,74,75]. Although scholarly investigation in the field of digital museums is still emerging, users often perceive virtual exhibitions as more personalised, visually appealing, and engaging than traditional interfaces [76]. Positive emotional responses experienced in situ are recognised as key facilitators of cognitive processing and memory consolidation [41]. Such emotions not only promote greater acceptance and appreciation of cultural content but also strengthen users’ emotional attachment to the cultural meanings embedded within the virtual experience [15].

Taken together, these five dimensions constitute the core stimulus that defines the quality of virtual exhibition experiences. They reflect an integration of technological functionality and psychological perception, encompassing both the technical performance of the system and the immersive experiences of the users. Collectively, these dimensions activate users’ cognitive and emotional processes, shaping their evaluations of cultural content, conceptualised as perceived cultural value, and fostering emotional affiliation with cultural heritage, conceptualised as cultural identity.

Based on the above discussion, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H1.

The quality of virtual exhibition experience has a positive effect on users’ perceived cultural value.

H1a.

Information quality positively influences perceived cultural value.

H1b.

System quality positively influences perceived cultural value.

H1c.

Perceived interactivity positively influences perceived cultural value.

H1d.

Perceived authenticity positively influences perceived cultural value.

H1e.

Perceived enjoyment positively influences perceived cultural value.

H2.

The quality of virtual exhibition experience has a positive effect on users’ cultural identity.

H2a.

Information quality positively influences cultural identity.

H2b.

System quality positively influences cultural identity.

H2c.

Perceived interactivity positively influences cultural identity.

H2d.

Perceived authenticity positively influences cultural identity.

H2e.

Perceived enjoyment positively influences cultural identity.

3.2.2. Perceived Cultural Value, Cultural Identity, and Offline Visiting Intention

In this study, the internal psychological processes are represented by two core outcomes arising from users’ virtual museum experiences: perceived cultural value and cultural identity. The behavioural response is conceptualised as users’ subjective evaluation and inclination to engage in an offline museum visit.

Perceived cultural value, as a cognitive appraisal of virtual exhibition content, exerts a direct influence on users’ behavioural motivation [38,39]. In the fields of cultural tourism and heritage studies, the cognitive pathway is frequently employed to elucidate how individuals form behavioural intentions through the comprehension and evaluation of cultural relevance and significance. Within digital cultural environments, virtual heritage exhibitions offer distinctive forms of engagement and knowledge delivery compared to traditional on-site experiences. When users perceive such exhibitions as culturally valuable in terms of educational significance, historical depth, or representational richness, they are more likely to develop a desire for further exploration through in-person visits, thereby reinforcing their intention to engage with the physical site [77,78]. Ultimately, users’ rational judgments of whether an offline visit is worthwhile is shaped by their perceived cultural value.

Cultural identity, by contrast, functions as an emotional affiliation and a potent catalyst for behavioural transformation. Yang et al. highlight that psychological experience and involvement in heritage tourism play a pivotal role in shaping individuals’ cultural identity [79]. Drawing on affective pathway theory, emotional identification fosters a sense of belonging and cultural pride, which in turn enhances behavioural engagement [44,80]. Within the context of virtual exhibitions, users who develop strong emotional ties to a particular culture in digital environments are more likely to pursue offline experiences that reinforce those connections, thereby bridging the divide between virtual and physical cultural settings. Prior studies further indicate that individuals with a heightened sense of cultural identity are more inclined to participate in heritage tourism, engage in cultural activities, and contribute to the preservation of cultural traditions [42].

Building on the preceding analysis, this study contends that perceived cultural value and cultural identity are not only significant psychological outcomes of virtual exhibition experiences but also serve as crucial mediating mechanisms shaping users’ intention to visit museums offline. In line with this theoretical proposition, the following hypotheses are formulated:

H3.

Users’ perceived cultural value positively influences their intention to visit the museum offline.

H4.

Users’ cultural identity positively influences their intention to visit the museum offline.

3.2.3. Dual Mediating Role of Perceived Cultural Value and Cultural Identity

In examining the behavioural transformation of virtual museum users, it is essential to consider the full trajectory of the SOR framework. This includes not only how external stimuli ‘S’ elicit internal cognitive and emotional responses ‘O’, which in turn lead to behavioural outcomes ‘R’, but also how cognitive and affective mechanisms interact within the organismic stage. Specifically, this study proposes a chain mediation pathway in which perceived cultural value enhances cultural identity, thereby strengthening users’ offline visiting intention. This mechanism underscores the layered psychological process through which virtual exhibition experiences translate into real-world behavioural motivation.

Firstly, perceived cultural value, as a cognitive-evaluative construct, fosters users’ deeper comprehension of cultural meanings and historical contexts. When individuals recognise the historical significance, societal relevance, or educational value of cultural content presented in virtual exhibitions, they are more likely to develop positive attitudes that lay the groundwork for emotional affiliation [77]. Prior research in digital heritage tourism and cultural communication further underscores that cognitive appreciation of cultural value serves as a critical precursor to the emergence of cultural belonging and identity [36].

Secondly, cultural identity, as a deeper affective response, plays a crucial role in translating cognitive evaluations into behavioural intentions. When users establish a strong sense of identification with the cultural narratives conveyed through virtual exhibitions, this emotional bond often motivates them to engage more actively with the culture in physical contexts. Previous studies have shown that cultural identity functions as a key mediating mechanism in both tourism and cultural communication domains, with stronger identity consistently associated with higher levels of engagement in cultural heritage preservation, dissemination, and consumption [42,81].

Therefore, this study posits that perceived cultural value influences offline visiting intention by reinforcing cultural identity, thereby establishing a sequential mediation pathway from cognition to emotion to behaviour.

Based on the foregoing theoretical reasoning, the following research hypotheses are proposed:

H5.

Perceived cultural value positively influences users’ cultural identity.

H6.

Perceived cultural value and cultural identity sequentially mediate the relationship between virtual exhibition experience quality and offline visiting intention.

H6a.

Perceived cultural value and cultural identity sequentially mediate the relationship between information quality and offline visiting intention.

H6b.

Perceived cultural value and cultural identity sequentially mediate the relationship between system quality and offline visiting intention.

H6c.

Perceived cultural value and cultural identity sequentially mediate the relationship between perceived interactivity and offline visiting intention.

H6d.

Perceived cultural value and cultural identity sequentially mediate the relationship between perceived authenticity and offline visiting intention.

H6e.

Perceived cultural value and cultural identity sequentially mediate the relationship between perceived enjoyment and offline visiting intention.

The conceptual model of this study is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The research model and hypotheses.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Research Context and Case Selection

This study adopts the official website of the Sanxingdui Museum (https://www.sxd.cn, accessed on 17 May 2025) as the research application platform and empirical context. As one of China’s most representative archaeological site museums, the Sanxingdui Museum preserves the heritage of the Sanxingdui site, which dates back approximately 3200 to 3000 years. The site has yielded a vast collection of bronze, gold, and jade artefacts that vividly demonstrate the advanced development of the ancient Shu civilisation. In July 2023, the site was officially included in the updated Tentative List of China’s World Cultural Heritage, underscoring its outstanding historical and academic value.

In response to the accelerating digitalisation of the heritage sector, the museum has actively expanded its online presence. Its official website includes several sections, including “Digital Exhibition”, “Knowledge Graph”, “Digital Collections”, and “Academic Research,” establishing an interactive and immersive virtual cultural platform (Figure 2). This platform integrates 3D modelling, VR-based panoramic browsing, and automated roaming with interactive features like multi-angle manipulation and semantic tours [82]. These elements allow users to engage with vivid representations of ancient Shu culture—its social landscape, cultural symbolism, and belief systems. Accordingly, the Sanxingdui digital platform was selected as the research case due to its strong cultural relevance and technical feasibility for supporting empirical analysis.

Figure 2.

Sanxingdui virtual exhibition platform. (a) Panoramic roaming interface with artefact introduction; (b) Immersive projection reconstructing the archaeological site scene.

4.2. Measurement Scales

The questionnaire comprised two structured sections. The first section collected demographic data, including gender, age, education, profession, income, virtual visit duration, and frequency of use, to construct a sample profile and control for demographic influences.

The second section comprised 26 measurement items corresponding to the eight latent constructs in the research model, all assessed on a seven-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). Information Quality (IQ) and System Quality (SQ) were adapted from Roca et al. [83], measuring users’ perceptions of content richness, timeliness, completeness, and the clarity and responsiveness of the system interface. Perceived Interactivity (PI) was based on McMillan et al. [84], assessing the extent to which users experienced control, freedom of exploration, and customisation during the virtual interaction. Perceived Authenticity (PA) was adapted from Hede et al. [68], capturing users’ subjective sense of cultural immersion and perceived relevance of the exhibits. Perceived Enjoyment (PE), derived from Wu and Lai [85], reflected the affective pleasure users experienced during the virtual visit. Perceived Cultural Value (PCV), informed by Chen et al. [86], focused on users’ cognitive understanding of cultural meaning and their perception of the exhibition’s role in cultural transmission. Cultural Identity (CI), based on Fu et al. [87], was measured through users’ acquisition of cultural knowledge, emotional attachment, and willingness to engage with cultural heritage. Offline Visiting Intention (OVI) was adapted from Huang et al. [88], assessing users’ intentions to visit the physical museum following their virtual experience. Details of the measurement items and their corresponding sources are provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Measurement Scale and Sources.

To ensure content validity, six academic experts in the fields of digital heritage, cultural communication and user experience were invited to review the preliminary questionnaire. Items identified with ambiguous wording, conceptual overlap, or weak construct relevance were revised and refined accordingly to enhance precision. A bilingual research assistant conducted the initial translation, followed by a back-translation by an independent researcher [89]. The content validity details are provided in Supplementary Table S1.

Before commencing the main data collection, a pilot test was carried out with 70 respondents who satisfied the predefined screening requirements. Results indicated that all constructs recorded Cronbach’s alpha coefficients greater than 0.70 and standardised factor loadings above 0.50, demonstrating adequate internal consistency and construct validity. These outcomes affirmed the questionnaire’s reliability and appropriateness for full-scale deployment.

4.3. Data Collection

To ensure the validity and relevance of the data, participants were required to meet two criteria. First, they had not previously visited the physical Sanxingdui Museum. Second, before answering the questionnaire, they completed a designated browsing task on the museum’s official website. We did not require prior virtual museum experience; the standardised browsing task provided a common experiential baseline. The survey was administered on Questionnaire Star (https://www.wjx.cn, accessed on 1 June 2025). Recruitment links and QR codes were shared across Chinese social media, including researcher-moderated groups and public feeds on QQ, WeChat groups and WeChat Moments, Xiaohongshu (rednote), and Weibo. Group administrators helped repost to communities differing in age range, geographic location and interests. Invitations used a single standard text that included a direct hyperlink to the museum website and asked invitees to explore the modules Digital Exhibition, Knowledge Graph and Digital Collections before starting the survey. All participants read the study instructions and provided informed consent. Respondents confirmed task completion in a required item before proceeding to the questionnaire. A prize draw was offered to encourage participation. Data were collected from 1 June to 15 July 2025.

In total, 553 responses were received. After excluding cases with completion times under one-minute, logical inconsistencies or identical and patterned answers, 467 valid responses remained. This sample size is approximately eighteen times the number of measurement items and exceeds common thresholds for structural equation modelling. Task compliance was encouraged through clear instructions and a required confirmation item. It was further approximated ex post using the same screening rules. This study utilised a non-probability, voluntary sampling method, and the protocol was approved by the institutional Human Research Ethics Committee.

5. Results

Data were analysed using SPSS 26.0 and AMOS 24.0. A two-step approach was adopted to validate the proposed research model [90]. First, Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was used to assess model fit, construct validity, and reliability. Second, Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) was employed to test the conceptual framework and examine the proposed hypotheses.

5.1. Descriptive Statistics

Table 3 summarises respondent demographics. Females comprised 55.89% of the sample, males 44.11%. Most were aged 18–25 (55.67%), followed by 26–35 (30.62%), indicating a predominantly young cohort. Additionally, 73.66% held at least a bachelor’s degree, suggesting an overall advanced education level.

Table 3.

Demographic profile of the sample (N = 467).

In terms of occupation, students comprised the largest group (47.11%), followed by employed individuals (39.19%), suggesting that the sample primarily consisted of individuals engaged in academic or professional pursuits. Monthly income was concentrated in the “below 3000 RMB” (41.33%) and “5000–10,000 RMB” (26.34%) ranges, which aligns with the income levels typically associated with younger age groups.

Regarding virtual museum usage, most respondents reported average visit durations of “10–30 min” (37.47%) or “30 min to 1 h” (30.41%), indicating a relatively immersive level of engagement. In terms of frequency, 49.68% had participated in virtual exhibitions 2–3 times, while 28.91% had experienced them only once. Overall, the sample shows adequate demographic diversity and basic familiarity with virtual museum experiences, providing a solid basis for subsequent model testing.

5.2. Reliability and Validity Analysis

A confirmatory factor analysis was conducted in AMOS 24.0 to examine the measurement model’s reliability and validity. Reliability assessment covered indicator reliability, reflected in the standardised factor loadings of each item, and internal consistency, measured via Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability (CR). Validity evaluation included construct validity, comprising convergent validity (based on Average Variance Extracted, AVE) and discriminant validity. This methodological approach is widely recognised in academic research for evaluating measurement models [91,92]. The results are presented in Table 4 and Table 5.

Table 4.

Results of Reliability and Validity Analysis (N = 467).

Table 5.

Results of Discriminant Validity (N = 467).

For indicator reliability, all factor loadings exceeded the 0.70 benchmark, indicating that each item effectively represented its respective construct. These findings confirm strong indicator reliability and support the measurement model’s precision and consistency [92]. Internal consistency tests showed Cronbach’s alpha values between 0.785 and 0.845, and CR values between 0.786 and 0.846, all above the 0.70 threshold, confirming satisfactory reliability.

Regarding convergent validity, all AVE values surpassed the recommended 0.50 minimum, demonstrating adequate convergence of items within constructs. Discriminant validity tested using the Fornell–Larcker criterion, showed that the square root of each construct’s AVE exceeded its correlations with other constructs, verifying that all constructs were empirically distinct [93].

5.3. Structural Model

5.3.1. Model Fit Assessment

Prior to path and mediation analyses, the structural model was evaluated in AMOS 24.0. The Research Model demonstrated good fit, with indices as follows: χ2/df = 1.452, GFI = 0.940, TLI = 0.971, CFI = 0.975, IFI = 0.976, NFI = 0.926, SRMR = 0.044, and RMSEA = 0.031. All indices met the recommended criteria, indicating an acceptable model fit. As shown in Table 6, both the measurement and research models satisfied the commonly accepted criteria, supporting the model’s suitability for hypothesis testing.

Table 6.

Fit indices of the measurement and research models (N = 467).

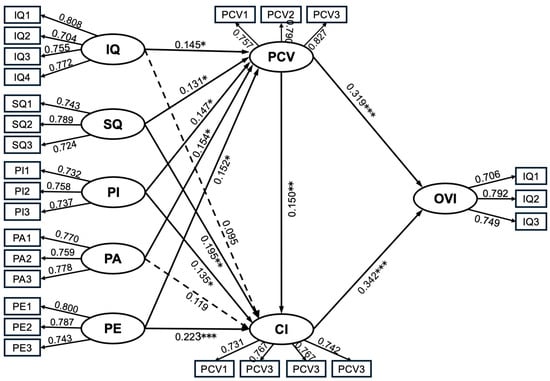

5.3.2. Direct Path Analysis

As shown in Table 7 and Figure 3, all five dimensions of virtual exhibition experience quality had significant positive effects on perceived cultural value. Specifically, perceived authenticity showed a comparable influence (β = 0.154, CR = 2.260, p = 0.024), followed closely by perceived enjoyment (β = 0.152, CR = 2.467, p = 0.014) and perceived interactivity (β = 0.147, CR = 2.289, p = 0.022). Information quality (β = 0.145, CR = 2.293, p = 0.022) and system quality (β = 0.131, CR = 2.065, p = 0.039) also showed significant positive effects. These results support H1a–H1e and confirm the central role of content quality, interactivity and engagement in shaping perceived cultural value. For cultural identity, the effect of information quality was not significant (β = 0.095, CR = 1.606, p = 0.108), and perceived authenticity was marginal and non-significant at the 0.05 level (β = 0.119, CR = 1.873, p = 0.061). By contrast, system quality (β = 0.195, CR = 3.257, p = 0.001), perceived interactivity (β = 0.135, CR = 2.240, p = 0.025) and perceived enjoyment (β = 0.223, CR = 3.805, p < 0.001) all had significant positive effects. These findings support H2b, H2c and H2e, but not H2a or H2d, underscoring the salience of technical reliability, interactive affordances and enjoyment in fostering identity formation.

Table 7.

Path coefficients and direct effects hypothesis testing.

Figure 3.

Structural equation model results. Dashed lines indicated no significant effects. *** p < 0.001. ** p < 0.01. * p < 0.05.

Both perceived cultural value (β = 0.319, C.R. = 5.18, p < 0.001) and cultural identity (β = 0.342, C.R. = 5.529, p < 0.001) demonstrated significant positive effects on offline visiting intention, supporting H3 and H4. The slightly larger coefficient for cultural identity suggests that visitors’ intention to visit the museum offline is more strongly driven by emotional identification than by cognitive evaluations of cultural value alone. Additionally, perceived cultural value significantly influenced cultural identity (β = 0.150, C.R. = 2.662, p = 0.008), supporting H5 and establishing the cognitive to affective transmission pathway that underpins the subsequent mediation analysis. Overall, the results support H1a to H1e, H2b, H2c, H2e, H3, H4 and H5, confirm a dual stage pathway in which experience quality enhances perceived cultural value and cultural identity, which in turn promote offline visiting intention.

5.3.3. Mediating Effect Analysis

To further examine how virtual exhibition experience quality influences users’ offline visiting intention via perceived cultural value and cultural identity, this study employed the bootstrapping method to assess the significance of the mediating paths. A total of 5000 bootstrap samples were generated at a 95% confidence level. As shown in Table 8, all tested mediation paths yielded statistically significant results.

Table 8.

Path coefficients and mediating effect hypothesis testing.

The analysis provides consistent support for the hypothesised chain mediation effects. Each of the five dimensions of virtual exhibition experience quality exhibited significant indirect effects on offline visiting intention through the sequential mediation of perceived cultural value and cultural identity. Specifically, the results were as follows: Information Quality (β = 0.007, 95% CI [0.002, 0.020], p = 0.006), System Quality (β = 0.007, 95% CI [0.001, 0.019], p = 0.014), Perceived Interactivity (β = 0.008, 95% CI [0.002, 0.020], p = 0.002), Perceived Authenticity (β = 0.008, 95% CI [0.002, 0.023], p = 0.004), and Perceived Enjoyment (β = 0.008, 95% CI [0.002, 0.022], p = 0.002). These results support H6a to H6e.

Taken together, the findings provide clear evidence for a sequential transmission from cognitive appraisal to emotional identification and then to behavioural intention. In other words, higher experience quality first strengthens perceived cultural value, which in turn enhances cultural identity, ultimately increasing users’ intention to visit the physical museum. This pattern underscores the pivotal role of value and identity processes formed in virtual settings in linking experience quality to real-world engagement.

6. Discussion

6.1. Discussion of Study Findings

Virtual Exhibition Experience Quality, Perceived Cultural Value, and Cultural Identity. The results confirmed that all five dimensions of virtual exhibition experience quality had significant positive effects on perceived cultural value. These dimensions include information quality, system quality, perceived interactivity, perceived authenticity, and perceived enjoyment. Together, they form the cognitive foundation upon which users construct cultural meaning. This finding aligns with Wu et al., who found similar positive effects of content quality and system performance on cultural value perception in digital heritage contexts [94]. Lin and Liu similarly emphasised the importance of accurate content and immersive environments, but our study extends their findings by demonstrating that perceived enjoyment plays an equally important role alongside traditional information quality factors [95].

With regard to cultural identity, the findings revealed that system quality, perceived interactivity, and enjoyment significantly influenced users’ cultural identity. This suggests that the smooth functioning of the system, active user engagement, and emotional pleasure all contribute meaningfully to a sense of cultural belonging. The significance of system quality indicates that reliable technical performance not only supports continued usage but also strengthens users’ trust in the platform. This enhanced trust facilitates recognition of the cultural content delivered, thereby contributing to cultural identity development. This finding is consistent with Wang et al., who reported similar system quality effects in digital intangible cultural heritage games, though our effect size appears somewhat stronger, suggesting that tangible archaeological artefacts may foster deeper identity connections than intangible cultural elements [63].

By contrast, information quality and perceived authenticity did not directly influence cultural identity. While these factors enhance cognitive value appraisal, richness and realism alone are insufficient to cultivate affective identification. This accords with Shehade and Stylianou-Lambert [96] and Wang et al. [63], who argue that identity in museum settings relies on symbolic and affective engagement. Authenticity becomes identity-relevant when it is embedded within narrative, participatory and enjoyable interactions. Without such scaffolds, even high-quality information and realistic rendering may raise cognition but will not reliably translate into emotional identification.

Perceived Cultural Value, Cultural Identity, and Offline Visiting Intention. The study further confirmed that perceived cultural value significantly predicts cultural identity, reinforcing the view that value acts as a cognitive precursor to affective affiliation [36]. At the same time, both perceived cultural value and cultural identity significantly predict offline visiting intention. This indicates that online experiences translate into behavioural intention when users both recognise the cultural value conveyed by the exhibition and, at an affective level, form a sense of identification with it. This pattern aligns with the value–intention and identity–behaviour relationships documented by Zeithaml and by Farivar and Wang, highlighting the joint operation of cognitive appraisal and affective identification in driving digital-to-offline conversion in heritage contexts [37,57].

Chain Mediation of Perceived Cultural Value and Cultural Identity. The analysis reveals a sequential mediation in which perceived cultural value and cultural identity transmit the influence of virtual exhibition experience quality to offline visiting intention. Both the more cognitive facets of experience quality (information quality, system quality) and the more experiential facets (interactivity, authenticity, enjoyment) act through a dual route: cultural value is appraised first, and this cognitive state subsequently fosters cultural identity as an affective attachment. This pattern is consistent with SOR based heritage research showing that cognitive appreciation of heritage values and affective responses jointly channel the effects of interpretive messages on behaviour, rather than exerting large direct impacts on behaviour itself. This finding supports Carmi et al. and Wang et al., who demonstrate that both cognitive and emotional processes drive altruistic or heritage supporting behaviours in heritage and environmental contexts [97,98].

In the specific context of a virtual archaeological site museum, the chain effects are numerically small but conceptually meaningful. This pattern is consistent with recent heritage interpretation research. For example, Wang et al. found that perceived heritage values and environmental sensitivity play a significant but relatively small chain-mediating role between interpretation messages and tourists’ pro-environmental behaviours [99]. In a similar way, users in the present study must first recognise why the heritage is valuable and then come to care about it before incurring the additional time, travel and cost required for an on-site visit. The relatively small yet robust indirect effects across all five dimensions of experience quality therefore reflect a realistic decision process rather than a trivial mechanism: when virtual exhibitions deepen users’ sense of cultural value and identity, they make an incremental but consistent contribution to converting online engagement into offline participation.

6.2. Theoretical Implications

This study offers four main theoretical contributions:

First, it extends the SOR framework to a virtual heritage context. We modelled experience quality as the external stimulus, perceived cultural value and cultural identity as the organismic states, and offline visiting intention as the behavioural response. The empirical support for a value to identity sequence within the organism stage clarifies how cognitive evaluation of cultural meaning precedes affective attachment, which in turn drives intentions to engage with heritage on site [98]. In addition, this configuration provides a transferable template for examining how diverse cultural settings (e.g., national or community museums) translate digitally mediated stimuli into culturally grounded responses.

Second, it strengthens the adaptability of the IS Success Model for cultural experience. We integrated interactivity, authenticity, and enjoyment to reflect the experiential features of virtual exhibitions. The findings show that technical reliability and interactive enjoyment are central for identity formation, whereas information richness and authenticity mainly contribute to value construction, thereby bridging technical logic with cultural and affective engagement [83]. This extension suggests that IS-based constructs can be fruitfully combined with culturally specific narrative and symbolic elements when analysing virtual heritage systems in diverse national and regional contexts.

Third, the study identifies perceived cultural value and cultural identity as the core psychological pathway linking digital experience to offline intention. Rather than treating value and identity as independent correlates, the results demonstrate a coherent chain in which perceived cultural value predicts cultural identity and both constructs predict visiting intention. This model captures the realistic psychological bridge between low-cost online engagement and high-effort offline participation, explaining how subtle shifts in cognition and affect cumulatively support sustainable heritage engagement [57].

Fourth, the study moves the virtual museum literature beyond technology acceptance towards sustainable cultural engagement, offering a framework with significant cross-cultural transferability. While acceptance-based accounts (e.g., TAM, UTAUT) focus primarily on system continuance, this study centres on meaning-making and identity formation as key drivers of physical visitation [6,34]. Although the empirical data derive from a Chinese archaeological site, the conceptual pathway, from digital stimuli, through cultural value and identity to offline engagement, is adaptable to other contexts. Crucially, while the specific content of “cultural value” or “identity” may differ across traditions, nations, and communities, the underlying mechanism linking interpretation, cognition, and affect to participation is likely operationalised [100]. This provides a robust foundation for future comparative research across diverse museum types, heritage regimes, and sociocultural environments.

6.3. Practical Implications

From a practical perspective, the findings offer actionable guidance for museums and cultural heritage institutions.

First, enhancing experience quality remains fundamental. The results show that information quality, system quality, perceived interactivity, perceived authenticity and perceived enjoyment are all important drivers of perceived cultural value. Museums should therefore continue to refine both content and technology. On the content side, knowledge graph-based presentations, expert led thematic narratives and context rich explanations can deepen users’ understanding of heritage [62]. On the technical side, stable performance, clear navigation and responsive interaction reduce friction and make it easier for users to focus on cultural meaning [101]. Immersive storytelling carefully designed visual interfaces and appropriate soundscapes can further enhance enjoyment and resonance [102,103]. Crucially, design should be tailored to context: indigenous museums might prioritise vernacular narration, while international institutions should emphasise comparative framing to connect global audiences with local heritage.

Second, virtual exhibitions should be designed to foster cultural identity, not just deliver information. The study indicates that offline visiting intention is most likely to emerge when perceived cultural value is transformed into a sense of identification. This has two practical implications. For local or domestic audiences, curators can emphasise themes of continuity, place-based memory and everyday cultural practices, so that users recognise their own backgrounds and experiences in the virtual narratives [62]. For non-local or international audiences, design teams can focus on points of connection, such as shared human concerns, universal themes or cross-cultural comparisons, helping visitors to situate unfamiliar heritage within their own frames of reference [81]. In both cases, personalised navigation, interactive storytelling and emotionally engaging audiovisual design can support users in moving from “understanding the culture” to “feeling connected to it”.

Third, institutions should use virtual platforms as bridges between online engagement and offline visitation within integrated, hybrid service models. The confirmed chain mediation of perceived cultural value and cultural identity suggests that virtual experiences can prepare users psycholo1gically for on-site visits, even if the effect is incremental rather than dramatic. In practice, this means that virtual exhibitions can be linked to concrete offline pathways: pre-visit information, ticket booking, tailored recommendations, and route planning that build on what users have already seen online [104]. Social media integration, user-generated content and post-visit sharing can further extend the influence of both the virtual and the physical museum [105]. Additionally, digitising local cultural resources can plant a “seed of curiosity” within users during virtual encounters, which can then grow into deeper cultural engagement via offline visits, thus completing the virtual-to-physical loop of cultural transmission.

6.4. Limitations and Further Research

While this study provides meaningful theoretical and practical contributions, several limitations should be acknowledged.

First, the empirical investigation focused on the Sanxingdui Virtual Museum, a highly representative cultural heritage institution with a distinctive thematic orientation and specific user base. Hence, the generalisability of the findings to other types of virtual museums (e.g., natural history, anthropology, science and technology) requires further validation. Future work could conduct comparisons across multiple sites with diverse thematic content and technological configurations, as well as replications across cultures, to assess the model’s applicability and robustness.

Second, although the study employed a structured questionnaire to test relationships among key variables with strong statistical validity, self-reports may not fully capture the dynamic, real-time processes through which users interact with virtual exhibitions (e.g., micro-level emotional fluctuations and moment-by-moment decision cues). Future research could adopt multimodal designs, including controlled experiments, behavioural log and clickstream data, eye tracking or emotion recognition, to reflect the immersive and temporal nature of engagement more accurately.

Third, the sampling frame comprised exclusively China-based respondents who participated voluntarily in an online survey distributed via social media channels, with a small prize draw as an incentive. This non-probability sampling approach is likely to over-represent younger, university-educated and digitally active users, so the findings may not be fully generalisable to older, less digitally connected or differently educated populations. Future studies could adopt probability-based or stratified sampling strategies, pay particular attention to underrepresented groups, and conduct cross-cultural or multigroup comparisons to further test the robustness and generalisability of the model.

7. Conclusions

This study examined how the quality of virtual museum exhibition experiences influences users’ intention to visit the corresponding physical museum, using the Sanxingdui Virtual Museum as an empirical case. Drawing on the SOR framework and key constructs from the Information Systems Success Model, we modelled five dimensions of experience quality—information quality, system quality, perceived interactivity, perceived authenticity and perceived enjoyment—as external stimuli; perceived cultural value and cultural identity as organismic states; and offline visiting intention as the behavioural response. The results show that virtual exhibition experience quality consistently enhances perceived cultural value and that system quality, interactivity and enjoyment also foster cultural identity. Perceived cultural value functions as a cognitive precursor to cultural identity, and both constructs, individually and sequentially, promote the intention to visit the physical museum. The consistent indirect effects observed across all five experience dimensions indicate a realistic cognitive–affective bridge between low-cost online engagement and higher-cost offline participation.

These findings contribute to sustainable heritage engagement research by clarifying a value- and identity-based pathway that links virtual experiences to offline cultural participation. Rather than focusing solely on technology acceptance, the study highlights how virtual heritage environments can be designed to cultivate cultural meaning and identification, thereby supporting longer-term relationships between audiences and heritage institutions. Future research can build on this framework by testing it in different types of museums and cultural settings, incorporating richer behavioural and physiological measures, and comparing visitor segments to explore how cultural value and identity operate across diverse sociocultural contexts.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su172310664/s1, Table S1: Content Validity Table. References [68,83,84,85,86,87,88] are cited in Supplementary Materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.M.; methodology, W.M.; investigation, W.M.; data curation, W.M.; formal analysis, W.M.; writing—original draft preparation, W.M.; writing—review and editing, W.M. and J.D.; visualization, W.M.; supervision, J.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee (JEPeM) of Universiti Sains Malaysia (approval code USM/JEPeM/PP/24080692; approval date: 17 January 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The data are not publicly available because they contain information that could compromise participant privacy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Schweibenz, W. The Virtual Museum: An Overview of Its Origins, Concepts, and Terminology. Mus. Rev. 2019, 4, 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Meng, J. Dialogues with Cultural Heritage via Museum Digitalisation: Developing a Model of Visitors’ Cognitive Identity, Technological Agent, Cultural Symbolism, and Public Engagement. Mus. Manag. Curatorship 2024, 39, 810–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, F.; Li, K.; Huang, X.; Zhang, X.; Wang, N.; Song, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Li, Y. An Empirical Study of Virtual Museum Based on Dual-Mode Mixed Visualization: The Sanxingdui Bronzes. Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Xu, J.; Li, C.; Yang, X. Gamification of Virtual Museum Curation: A Case Study of Chinese Bronze Wares. Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, Y.; Xie, J. The Evolution of Digital Cultural Heritage Research: Identifying Key Trends, Hotspots, and Challenges through Bibliometric Analysis. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Guo, Y. A New Destination on the Palm? The Moderating Effect of Travel Anxiety on Digital Tourism Behavior in Extended UTAUT2 and TTF Models. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 965655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zou, Y.; Li, Y.; Peng, C.; Jin, D. Embodied Power: How Do Museum Tourists’ Sensory Experiences Affect Place Identity? J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2024, 60, 334–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, B.; Qin, J. From Digital Museuming to On-Site Visiting: The Mediation of Cultural Identity and Perceived Value. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1111917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manghisi, V.M.; Uva, A.E.; Fiorentino, M.; Gattullo, M.; Boccaccio, A.; Monno, G. Enhancing User Engagement through the User Centric Design of a Mid-Air Gesture-Based Interface for the Navigation of Virtual-Tours in Cultural Heritage Expositions. J. Cult. Herit. 2018, 32, 186–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Chen, X.; Zhao, J.; Xie, Y. Influences of Design and Knowledge Type of Interactive Virtual Museums on Learning Outcomes: An Eye-Tracking Evidence-Based Study. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2024, 29, 7223–7258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Jiang, Q.; Liang, H.; Ni, S. What Drives Users to Adopt a Digital Museum? A Case of Virtual Exhibition Hall of National Costume Museum. SAGE Open 2022, 12, 21582440221082105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dağ, K.; Çavuşoğlu, S.; Durmaz, Y. The Effect of Immersive Experience, User Engagement and Perceived Authenticity on Place Satisfaction in the Context of Augmented Reality. Libr. Hi Tech 2024, 42, 1331–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, F.; Wu, S.; Liu, R.; Bai, Y. What Influences User Continuous Intention of Digital Museum: Integrating Task-Technology Fit (TTF) and Unified Theory of Acceptance and Usage of Technology (UTAUT) Models. Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Yan, S.; Wang, J.; Xue, Y. Flow Experiences and Virtual Tourism: The Role of Technological Acceptance and Technological Readiness. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.-K.; Huang, H.-L. Virtual Tourism Atmospheres: The Effects of Pleasure, Arousal, and Dominance on the Acceptance of Virtual Tourism. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2022, 53, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Chen, Y.; Sun, Y. Influences of VR Technology on the Effect of Museum Narrative Based on Embodied Cognitive Theory: A Case Study of the Opium War Museum. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2024, 16, 269–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, K.; Fan, A.; Lehto, X.; Day, J. Immersive Digital Tourism: The Role of Multisensory Cues in Digital Museum Experiences. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2023, 47, 1017–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLone, W.H.; McLean, E.R. Information Systems Success: The Quest for the Dependent Variable. Inf. Syst. Res. 1992, 3, 60–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabian, A.; Russell, J.A. An Approach to Environmental Psychology; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974; ISBN 978-0-262-13090-5. [Google Scholar]

- International Council of Museums (ICOM). Museum Definition; ICOM: Paris, France, 2022; Available online: https://icom.museum/en/resources/standards-guidelines/museum-definition/ (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- Hein, H.S. The Museum in Transition: A Philosophical Perspective; Smithsonian Institution: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Y.; Teng, W. Contemplating Museums’ Service Failure: Extracting the Service Quality Dimensions of Museums from Negative On-Line Reviews. Tour. Manag. 2018, 69, 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Nie, J.-W.; Ye, J. Evaluation of Virtual Tour in an Online Museum: Exhibition of Architecture of the Forbidden City. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0261607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunliffe, D.; Kritou, E.; Tudhope, D. Usability Evaluation for Museum Web Sites. Mus. Manag. Curatorship 2001, 19, 229–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skov, M.; Ingwersen, P. Museum Web Search Behavior of Special Interest Visitors. Libr. Inf. Sci. Res. 2014, 36, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostino, D.; Arnaboldi, M.; Lampis, A. Italian State Museums during the COVID-19 Crisis: From Onsite Closure to Online Openness. Mus. Manag. Curatorship 2020, 35, 362–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komarac, T.; Ozretić Došen, Đ. Understanding Virtual Museum Visits: Generation Z Experiences. Mus. Manag. Curatorship 2024, 39, 357–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yang, R.; Zou, J.; Xu, H.; Tian, F. Human-Centric Virtual Museum: Redefining the Museum Experience Through Immersive and Interactive Environments. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2025, 41, 8426–8437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbanzadeh, D.; Nair, K.; Chandra, T.; Bakhtiyorovich Ergashev, J.; Prasad, K.D.V. Virtual Reality and Tourism Destinations Marketing: Can It Transform Travel? Evaluating the Impact of Immersive Experiences on Travel Intentions. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2024, 37, 1526–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banfi, F.; Pontisso, M.; Paolillo, F.R.; Roascio, S.; Spallino, C.; Stanga, C. Interactive and Immersive Digital Representation for Virtual Museum: VR and AR for Semantic Enrichment of Museo Nazionale Romano, Antiquarium Di Lucrezia Romana and Antiquarium Di Villa Dei Quintili. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2023, 12, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, C.; Mao, R.; Wang, C. Digitally Enriched Exhibitions: Perspectives from Museum Professionals. Tour. Manag. 2024, 105, 104970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassenzahl, M.; Tractinsky, N. User Experience—A Research Agenda. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2006, 25, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thüring, M.; Mahlke, S. Usability, Aesthetics and Emotions in Human–Technology Interaction. Int. J. Psychol. 2007, 42, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Jiang, Q.; Ni, S.; Liang, H. Critical Factors for Predicting Users’ Acceptance of Digital Museums for Experience-Influenced Environments. Information 2021, 12, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Tuo, Y.; Bai, C.; Lin, Z. Curating Wellness: Exploring Healing Experiences in Digitally Transformed Museums. Tour. Manag. 2025, 111, 105207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallarza, M.G.; Gil Saura, I. Value Dimensions, Perceived Value, Satisfaction and Loyalty: An Investigation of University Students’ Travel Behaviour. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 437–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V.A. Consumer Perceptions of Price, Quality, and Value: A Means-End Model and Synthesis of Evidence. J. Mark. 1988, 52, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Dahalan, N.; Jaafar, M. Tourists’ Perceived Value and Satisfaction in a Community-Based Homestay in the Lenggong Valley World Heritage Site. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2016, 26, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, J.C.; Soutar, G.N. Consumer Perceived Value: The Development of a Multiple Item Scale. J. Retail. 2001, 77, 203–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Ma, Z.; Wang, S. Understanding Users’ Recommendation Intention of Online Museums: A Perspective of the Cognition-Emotion-Behavior Theory and the Expectation Confirmation Model. npj Herit. Sci. 2025, 13, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besoain, F.; González-Ortega, J.; Gallardo, I. An Evaluation of the Effects of a Virtual Museum on Users’ Attitudes towards Cultural Heritage. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo-García, C.; Coll-Serrano, V.; Rausell-Köster, P.; Pérez Bustamante-Yábar, D. Cultural Attitudes and Tourist Destination Prescription. Ann. Tour. Res. 2018, 71, 59–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, S. Cultural Identity and Diaspora. In Colonial Discourse and Post-Colonial Theory; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2015; pp. 392–403. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, J.-S.; Lin, C.-H.; Morais, D.B. Antecedents of Attachment to a Cultural Tourism Destination: The Case of Hakka and Non-Hakka Taiwanese Visitors to Pei-Pu, Taiwan. J. Travel Res. 2005, 44, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esman, M.R. Tourism as Ethnic Preservation: The Cajuns of Louisiana. Ann. Tour. Res. 1984, 11, 451–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besculides, A.; Lee, M.E.; McCormick, P.J. Residents’ Perceptions of the Cultural Benefits of Tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2002, 29, 303–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.-N.; Ruan, W.-Q.; Yang, T.-T. National Identity Construction in Cultural and Creative Tourism: The Double Mediators of Implicit Cultural Memory and Explicit Cultural Learning. Sage Open 2021, 11, 21582440211040789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, E.; Kim, H.; Uysal, M. Life Satisfaction and Support for Tourism Development. Ann. Tour. Res. 2015, 50, 84–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, M.; Cànoves, G.; Chu, Y.; Font-Garolera, J.; Prat Forga, J.M. Influence of Cultural Background on Visitor Segments’ Tourist Destination Image: A Case Study of Barcelona and Chinese Tourists. Land 2021, 10, 626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleveland, M.; Bartikowski, B. Cultural and Identity Antecedents of Market Mavenism: Comparing Chinese at Home and Abroad. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 82, 354–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Guo, X.; Guo, X.; Jolibert, A. Consumer Purchase Intention of Intangible Cultural Heritage Products (ICHP): Effects of Cultural Identity, Consumer Knowledge and Manufacture Type. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2023, 35, 726–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Wang, C.L. Cultural Identity and Consumer Ethnocentrism Impacts on Preference and Purchase of Domestic versus Import Brands: An Empirical Study in China. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 1225–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trunfio, M.; Campana, S. A Visitors’ Experience Model for Mixed Reality in the Museum. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 1053–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Lai, I.K.W. Identifying the Response Factors in the Formation of a Sense of Presence and a Destination Image from a 360-Degree Virtual Tour. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 21, 100640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun, M.Y.; O’Keefe, R.M. Virtual Destination Image: Testing a Telepresence Model. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFee, A.; Mayrhofer, T.; Baràtovà, A.; Neuhofer, B.; Rainoldi, M.; Egger, R. The Effects of Virtual Reality on Destination Image Formation. In The Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2019; Pesonen, J., Neidhardt, J., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 107–119. [Google Scholar]

- Farivar, S.; Wang, F. Effective Influencer Marketing: A Social Identity Perspective. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 67, 103026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, N.; Lee, H.; Kim, J.-Y.; Koo, C. The Role of Augmented Reality for Experience-Influenced Environments: The Case of Cultural Heritage Tourism in Korea. J. Travel Res. 2018, 57, 627–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, E.; Mathur, A.; Smith, R.B. Store Environment and Consumer Purchase Behavior: Mediating Role of Consumer Emotions. Psychol. Mark. 1997, 14, 361–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Tian, Y.; Pei, S. Technological Use from the Perspective of Cultural Heritage Environment: Augmented Rea1lity Technology and Formation Mechanism of Heritage-Responsibility Behaviors of Tourists. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatautis, R.; Vitkauskaite, E.; Gadeikiene, A.; Piligrimiene, Z. Gamification as a Mean of Driving Online Consumer Behaviour: SOR Model Perspective. Eng. Econ. 2016, 27, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, H.; Pan, Y. What Influences Users’ Continuous Behavioral Intention in Cultural Heritage Virtual Tourism: Integrating Experience Economy Theory and Stimulus–Organism–Response (SOR) Model. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Men, D. Understanding Continued Use Intention of Digital Intangible Cultural Heritage Games through the SOR Model. npj Herit. Sci. 2025, 13, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Tsiga, Z.; Li, B.; Zheng, S.; Jiang, S. What Influence Users’ e-Finance Continuance Intention? The Moderating Role of Trust. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2018, 118, 1647–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aladwani, A.M.; Palvia, P.C. Developing and Validating an Instrument for Measuring User-Perceived Web Quality. Inf. Manag. 2002, 39, 467–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, A.; Ma, D.; Pan, Y.; Qian, H. Enhancing Museum Visiting Experience: Investigating the Relationships Between Augmented Reality Quality, Immersion, and TAM Using PLS-SEM. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2024, 40, 4521–4532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Jung, T.H.; tom Dieck, M.C.; Chung, N. Experiencing Immersive Virtual Reality in Museums. Inf. Manag. 2020, 57, 103229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]