1. Introduction

The rapid growth of global energy demand has raised widespread concerns regarding the security of energy supply, environmental degradation, and the urgency of a low-carbon transition [

1]. According to statistics, civil engineering and construction activities alone account for approximately 30–40% of total global energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions [

2]. In the renewable energy sector, the development of hydropower and nuclear energy has approached saturation, while solar and wind energy are constrained by climatic conditions and intermittent output. In contrast, geothermal energy has significant advantages, including high stability, renewability, and a high utilization rate, positioning it as a key driver in the ongoing energy transition [

3].

As an innovative approach to geothermal energy utilization, energy pile technology allows for the simultaneous support of structural loads and the exploitation of shallow geothermal energy through embedded heat exchange pipes [

4]. Compared with conventional ground source heat pump systems, energy piles offer several advantages, such as shorter construction periods, lower installation costs, and more efficient land use [

5]. These benefits significantly improve geothermal energy utilization while reducing reliance on traditional energy sources and associated carbon emissions. Currently, the main types of energy pile foundations include steel pipe piles, bored piles, precast piles, and static drill-rooted piles. Although steel pipe piles can be used for energy pile construction, their structural limitations often prevent them from meeting high load-bearing requirements. Conventional precast piles, limited by construction techniques, also tend to fall short of achieving the ideal depths required for energy pile applications. In contrast, bored piles and static drill-rooted piles demonstrate clear advantages in load-bearing capacity and geological adaptability, offering broader application prospects. Notably, static drill-rooted piles combine the advantages of both bored and precast piles, providing high pile quality alongside significant environmental benefits, and are increasingly adopted in coastal areas.

Recently, the application of energy pile technology has expanded across diverse fields. Kong et al. [

6] developed a bridge deck geothermal snow-melting system that uses pile-based heat exchangers and investigated its performance under snowfall conditions. Ren et al. [

7] conducted a thermal response field test on a group of energy piles under embankment loads during winter as part of the China Sanmenxia National Highway 310 project. They analyzed temperature profiles, stress variations, and thermal properties while also assessing the feasibility of a new pipe installation technique. Wang et al. [

8] applied energy pile technology by integrating heat exchange pipes to harness shallow geothermal energy, effectively reducing the maximum temperature differential by 53.4% in large-volume concrete structures of high-altitude bridge piers. This approach also minimized expansion strain, had minimal impact on the pile foundation, achieved high heat exchange efficiency, and demonstrated a coefficient of performance (COP) of 4.0, highlighting its potential to enhance infrastructure resilience and service life. Cerra et al. [

9] assessed the feasibility of an energy pile-based collective heating and cooling network in the new district of Vejle, Denmark, and developed a temperature model based on hydrogeological and building energy consumption data to estimate the long-term performance and maximum serviceable building area of the system. The results indicated that energy piles could support heating and cooling for three- to four-story buildings, depending on the design and usage. Pagola et al. [

10] studied a ground-source heat pump system based on energy piles at the Vejle Rosborg High School in Denmark, which has been providing heating and cooling for a 4000 m

2 building since 2011. Operational data indicated that, although asymmetric soil usage could cause temperature drops, the winter heating supply temperature remained above 4.2 °C, and summer soil recovery occurred. The system achieved seasonal performance factors of 2.7 for heating and 4.2 for cooling, demonstrating its feasibility for buildings with high heating demands while suggesting room for optimization in energy management. Loveridge et al. [

11] discussed the thermal performance measurement of energy pile systems under different environmental conditions based on the case of the Zurich Airport dock section. Hassam et al. [

12] conducted a 30-year numerical simulation calibrated with field data and found that, in a residential building project in Melbourne, Australia, the use of an energy pile system reduced energy consumption by 75% and energy costs by 5% compared to a natural gas boiler. Furthermore, compared to air-source heat pumps, the heating and cooling mode with energy piles resulted in a 39% reduction in energy consumption, carbon emissions, and costs. Optimizing pile spacing, pile length, and the number of piles could enhance energy pile benefits by 76–119%, emphasizing the critical role of building thermal loads and pile configuration in early-stage design.

As energy pile technology has evolved and its application in building heating and cooling has expanded, scholars have increasingly studied its environmental impacts. A major focus has been the effects of energy piles on the thermodynamic behavior of surrounding soils, particularly concerning soil temperature, pore water pressure, and consolidation settlement. Cherati et al. [

13] investigated the effects of various parameters on transient heat transfer in the unsaturated soils surrounding energy piles, with particular emphasis on soil moisture, temperature changes, and the potential environmental impacts of the heat transfer process. The environmental impact of energy piles extends beyond soil behavior but also involves comprehensive life cycle assessments (LCA). Zhang et al. [

14] systematically evaluated low-carbon optimization measures across the design, construction, and operation stages of energy piles from a life cycle perspective and proposed systematic theories and methods for optimal decarbonization. In addition, Sutman et al. [

15] analyzed the long-term performance of energy piles under three different climate conditions using finite element simulations and LCA. Their results indicated that energy pile systems performed excellently in both heating and cooling. Although geothermal operation caused soil temperature fluctuations, the overall environmental impact was significantly reduced. Kong et al. [

16] performed experimental analysis on a ground source heat pump system used for a 25 m

2 building in Yichang, Hubei Province. They explored the thermal response and performance of the energy pile system, finding that it achieved a 12.2% to 21.2% higher COP and faster start-up speed compared to air-source heat pump systems under both continuous and intermittent operation. Shen et al. [

17] introduced an innovative approach by using alkali-activated concrete (AAC) in energy piles. A systematic comparison between AAC and Portland cement concrete energy piles revealed that AAC piles offered approximately 17% higher thermal energy extraction and 32% lower carbon dioxide emissions. Han et al. [

18] conducted an in-depth sustainability analysis of energy pile systems by establishing an integrated evaluation framework. They comprehensively assessed the energy-saving, economic, and environmental benefits using OpenStudio and GLHEPro software. You et al. [

19] investigated the thermal imbalance in helical coil energy pile groups under seepage conditions and found that groundwater flow effectively mitigated soil temperature declines around piles, thus improving heating efficiency and reducing energy consumption. Moel et al. [

20] emphasized that the main environmental benefit of geothermal systems is their ability to reduce fossil energy consumption by harnessing clean, renewable energy. Compared to air-source heat pumps, geothermal systems inherently operate more efficiently due to the relatively stable ground temperature. This stability, with less fluctuation as a heat source or sink, allows the system to function near its optimal design conditions throughout the year, achieving a higher COP. Regarding system design, energy pile technology demonstrates wide adaptability and can be applied under various ground conditions, not just in urban areas. Rawlings and Sykulski [

21] highlighted several additional technical advantages of energy pile heat pump systems, including low operational noise (due to the absence of external fans), no need for roof penetrations, higher safety (due to the absence of external equipment), and enhanced overall building safety, since no explosive gases are involved.

Recently, as a novel energy pile technology that combines the advantages of precast piles and bored piles, static drill-rooted energy piles have been increasingly applied in foundation engineering projects in coastal areas. The construction process of this technology primarily includes key steps, such as borehole grouting, reinforcement and heat exchanger pipe installation at the pile head, pile pressing with simultaneous heat exchanger embedding, pile connection, and heat exchanger integration and protection. During the drilling process, the technique mixes cement slurry with in situ soil to form a continuous cement-soil medium. The pile and heat exchanger pipes are simultaneously installed using a static pressing method, which not only facilitates easy installation with low resistance but also improves heat exchange efficiency due to direct contact between the exchanger and the surrounding soil and a shortened heat transfer path. Current research mainly focuses on the heat transfer performance, mechanical properties, and environmental impacts of static drill-rooted energy piles. Fang et al. [

22] conducted thermal-mechanical tests under both short-term and long-term conditions to systematically analyze changes in pile temperature, performance coefficient, axial additional stress, and shaft friction. They revealed how pile head and toe constraints influence the mechanical behavior of the pile and provided theoretical support for the application of energy pile technology. Chang et al. [

23] conducted indoor model tests to compare the thermo-mechanical responses of static drill-rooted energy piles (SEP) and ordinary energy piles under 20 cycles of monotonic cooling. Their results revealed that SEP exhibited smaller displacements and minimal bearing capacity degradation under thermal loading, highlighting the significant impact of pile structure and soil constraint differences on thermo-mechanical coupling behavior. Chen et al. [

24] studied the effect of SEP operation on the consolidation of surrounding soil using ABAQUS simulations to assess changes in temperature, pore water pressure, and settlement of the soil around the pile, providing a theoretical basis for understanding SEP behavior in soil environments. With the growing application of SEP, its environmental impact has drawn growing attention. In particular, there is a need to investigate the energy-saving and emission-reduction potential of this technology. On the other hand, further research is needed to evaluate its suitability for deployment near sensitive structures, such as in densely built urban areas and adjacent to subways.

In summary, the application of energy pile technology continues to expand across fields such as building construction and transportation. As an emerging construction method, the static drill-rooted energy pile offers distinct technical advantages and environmental sustainability. Consequently, it is crucial to conduct in-depth research into its environmental characteristics, particularly to assess its applicability in sensitive areas such as dense urban environments and near metro infrastructures. Currently, there is a lack of a systematic environmental impact assessment framework, and project-specific environmental impact studies are also limited. In particular, research on the environmental impacts of static drill-rooted energy piles remains notably insufficient. This study aimed to investigate the environmental impacts of static drill-rooted energy piles, establish a comprehensive environmental impact assessment system, and apply it to a real-world project, thereby providing theoretical support for the broader adoption of this technology.

Unlike conventional LCA-based research that mainly focuses on carbon emissions and resource consumption during material production, construction, and operation, this study extends the assessment scope by incorporating direct environmental disturbance factors, such as muck and slurry discharge, vibration, and noise. Building upon the LCA framework and guided by the Chinese national standard GB/T 50378 Assessment Standard for Green Buildings [

25], a multi-dimensional indicator system is established to integrate construction-phase environmental impacts with life-cycle carbon reduction effects. This enables a more comprehensive and quantifiable evaluation of the environmental performance of static drill-rooted energy piles, particularly in coastal soft-soil areas and metro-adjacent environments.

3. Case Study for Static Drill-Rooted Energy Piles

3.1. Project Overview

The project is located in Longshan Town, Cixi City, Ningbo, Zhejiang Province, China. It utilizes a ground-source heat pump system that combines energy piles with vertical borehole heat exchangers. The system primarily serves a comprehensive building, a cafeteria, and a dormitory, providing domestic hot water. The dormitory building uses PHC600(110)AB+PHDC650-500(100)AB-500/600 piles, each 60 m long. The comprehensive building uses PHC800(110)AB+PHDC800-600(110)AB-600/800 piles with lengths of 58 and 63 m. The static drill-rooted energy piles are constructed without base expansion. Basic project information is presented in

Table 8, and the site soil conditions are detailed in

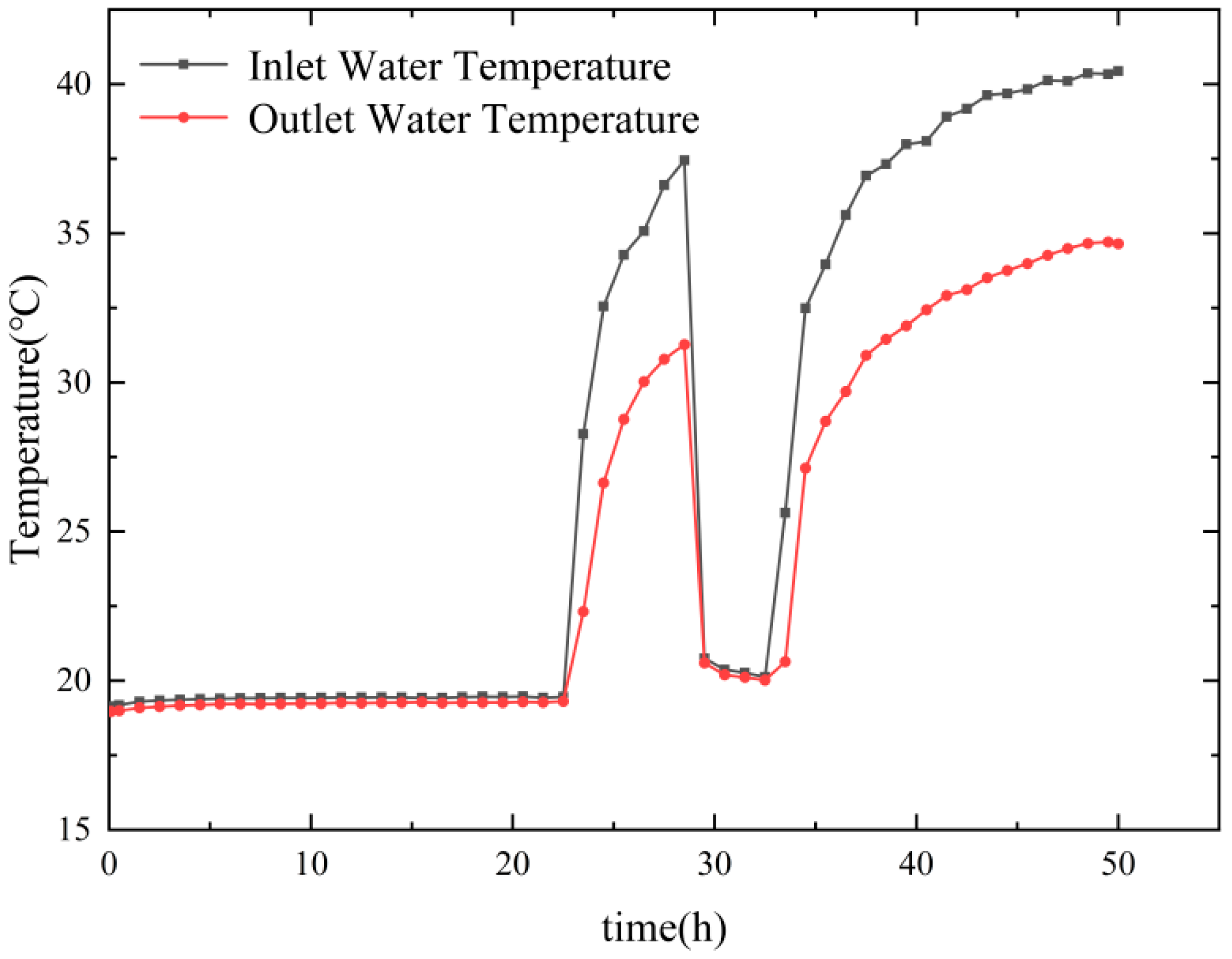

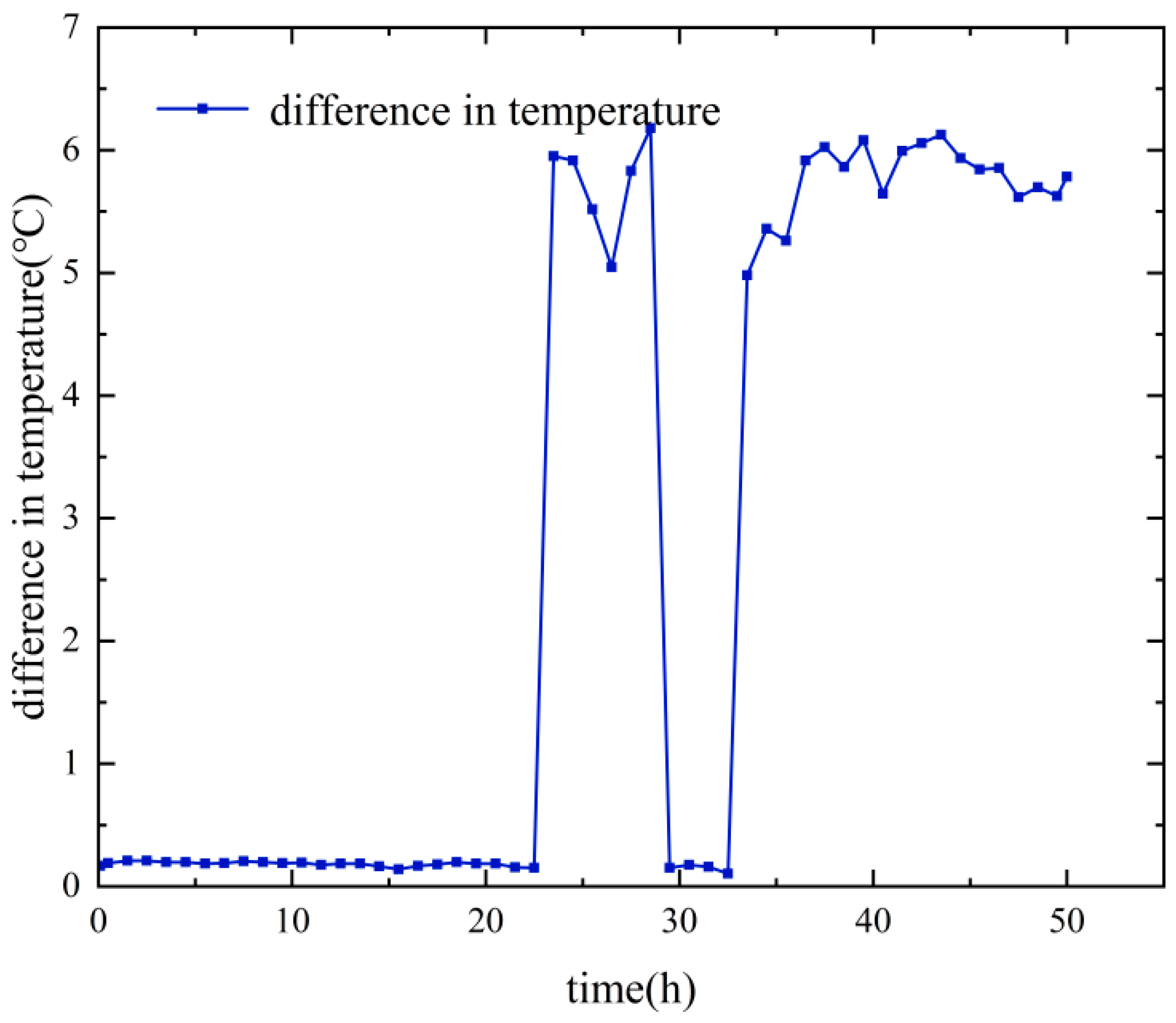

Table 9. The inlet and outlet water temperatures for the static drill-rooted energy pile system are illustrated in

Figure 1, and the temperature difference between the inlet and outlet water is demonstrated in

Figure 2. The construction of the static drill-rooted energy piles is exhibited in

Figure 3.

3.2. Muck Discharge

To analyze the muck discharge during construction at different pile hole sizes, the site’s muck layer parameters were used in the calculation. These parameters, including key indicators such as thickness, density, and cohesion, are presented in

Table 2. Based on engineering experience and on-site testing, the following values were adopted: r

2 = 1150 kg·m

−3, r

2′ = 1300·kg·m

−3, r

3 = 1200 kg·m

−3, r

4 = 1150 kg·m

−3, r

4′ = 1450 kg·m

−3, and

a = 1.1. The calculation results are presented in

Table 10.

The data in

Table 10 indicates a clear positive correlation between drilling diameter and discharged soil volume—the larger the diameter, the greater the volume of discharged soil. For static drill-rooted energy piles, increasing the drilling diameter from 700 to 1000 mm results in an increase in soil discharge from 12.37 to 26.41 m

3. In contrast, for bored energy piles, the same increase in diameter leads to a rise in soil discharge from 39.46 to 80.53 m

3. The soil discharge for static drill-rooted energy piles is significantly lower than that of bored energy piles for the same drilling diameter. For example, based on the data from the Ningbo Longshan Base project, when the drilling diameter is 800 mm, the soil discharge for static drill-rooted energy piles is 16.16 m

3, compared to 51.54 m

3 for bored energy piles. This represents a 68.65% reduction in soil discharge when using static drill-rooted energy piles. When the drilling diameter is 1000 mm, the soil discharge for static drill-rooted energy piles is 26.41 m

3, whereas, for bored energy piles, it reaches 80.53 m

3, resulting in a 67.2% reduction in soil discharge when using static drill-rooted energy piles.

- 2.

Slurry Discharge

For bored piles, concrete is injected from the bottom of the pile hole upwards, gradually displacing the slurry. The main purpose of the slurry is to stabilize the hole walls and prevent collapse. After drilling, the slurry within the hole is discharged, typically in relatively large volumes. Bored piles generally require a substantial amount of slurry to maintain wall stability, and their design often features larger diameters to accommodate this process.

Although static drill-rooted energy piles do not require large-scale concrete injection, cement slurry is still sprayed into the pile hole to mix with the surrounding soil, forming a cement-soil composite that enhances the pile’s stability and load-bearing capacity. Compared to bored piles, static drill-rooted energy piles have smaller diameters and require relatively less cement slurry, resulting in a smaller overall volume. For the same load-bearing capacity, the volume of bored piles is generally 1.5–2 times larger than that of static drill-rooted energy piles. Thus, slurry discharge for static drill-rooted energy piles is typically reduced by 40–60%.

During the construction of static drill-rooted energy piles, the pile body exerts pressure on the surrounding soil as it advances after the cement slurry is injected. This pressure not only facilitates the integration of the pile with the soil but also forces a portion of the cement-soil mixture into the surrounding ground, thereby reducing slurry discharge. Additionally, due to the pressure exerted by the pile body on the surrounding soil, the cement-soil mixture blends with the original soil, which not only enhances the stability of the pile but also reduces the slurry discharge. Considering the effects of this pressure, the slurry discharge for static drill-rooted energy piles is reduced by 60–70% compared to bored piles. Based on field surveys, the Longshan base has a slurry pit, and each static drill-rooted energy pile position discharges approximately 15–20 tons of slurry. Compared to bored piles, the entire project saves 2530 tons of slurry discharge.

- 3.

Evaluation of Muck and Slurry Discharge

The static drill-rooted energy piles exhibit significant emission reduction advantages during the construction phase. Compared to traditional bored piles, they eliminate the need for large amounts of drilled soil and circulating slurry, resulting in a 67.2–68.65% reduction in soil discharge and an approximately 60–70% reduction in slurry discharge. According to field surveys and data, the construction company has established a closed slurry pit on-site to temporarily store and centrally process the small amount of slurry generated during pile construction. The construction area is kept clean, with no spillage observed, and the discharge practices adhere to regulations. Based on the evaluation criteria, the soil and slurry discharge performance of this static drill-rooted energy pile project is rated as ‘‘Good’’.

3.3. Vibration Response

During construction, traditional diesel-driven pile-driving technologies generate intense vibrations, with the large impact force often posing a health risk to humans. These vibrations can also cause cracks or even damage to nearby buildings and pipelines. Consequently, in sensitive areas—such as densely populated districts, areas around existing subway lines, and historic building protection zones—it is necessary to select pile foundation types that minimize environmental impact.

A custom wireless vibration accelerometer, with a range of 8 g and a minimum scale of 1 g, was selected to continuously measure vibration acceleration. The initial recording frequency was set to 60 times/min. The vibration acceleration in the x, y, and z directions of the accelerometer is considered positive in the direction indicated by the arrows, as illustrated in

Figure 4.

The arrangement of measurement points is designed to record the distance and illustrate the attenuation curve of vibration acceleration with distance.

Table 11 presents the detailed locations of the vibration accelerometer, which are sequentially arranged on the construction machine and at distances of 30 m and 40 m from the vibration source.

The installation of the vibration accelerometer directly impacts the measurement results, and the material properties and transmissibility of the surface where it is installed are highly correlated. To maintain a strong adhesive bond while reducing vibration damping from rubber, Kraft 704 silicone rubber electronic adhesive is used. It is important to ensure that the adhesive layer thickness does not exceed 2 mm during bonding. The installation of the vibration accelerometer is illustrated in

Figure 5.

- 2.

Vibration Data Processing

The vibration accelerometer uploads data to the ‘‘Grafana’’ website via a gateway for data aggregation. The effective vibration acceleration values are used for sorting, with each measurement point including vibration values in the x, y, and z directions. During on-site measurements, the vibration accelerometer is installed with the same orientation. When there is no vibration, the acceleration in the z-axis direction (the direction of free fall motion) is 1 g, while the accelerations in the x and y axes (perpendicular to the direction of free fall motion) are 0.

- 3.

Vibration Evaluation and Analysis

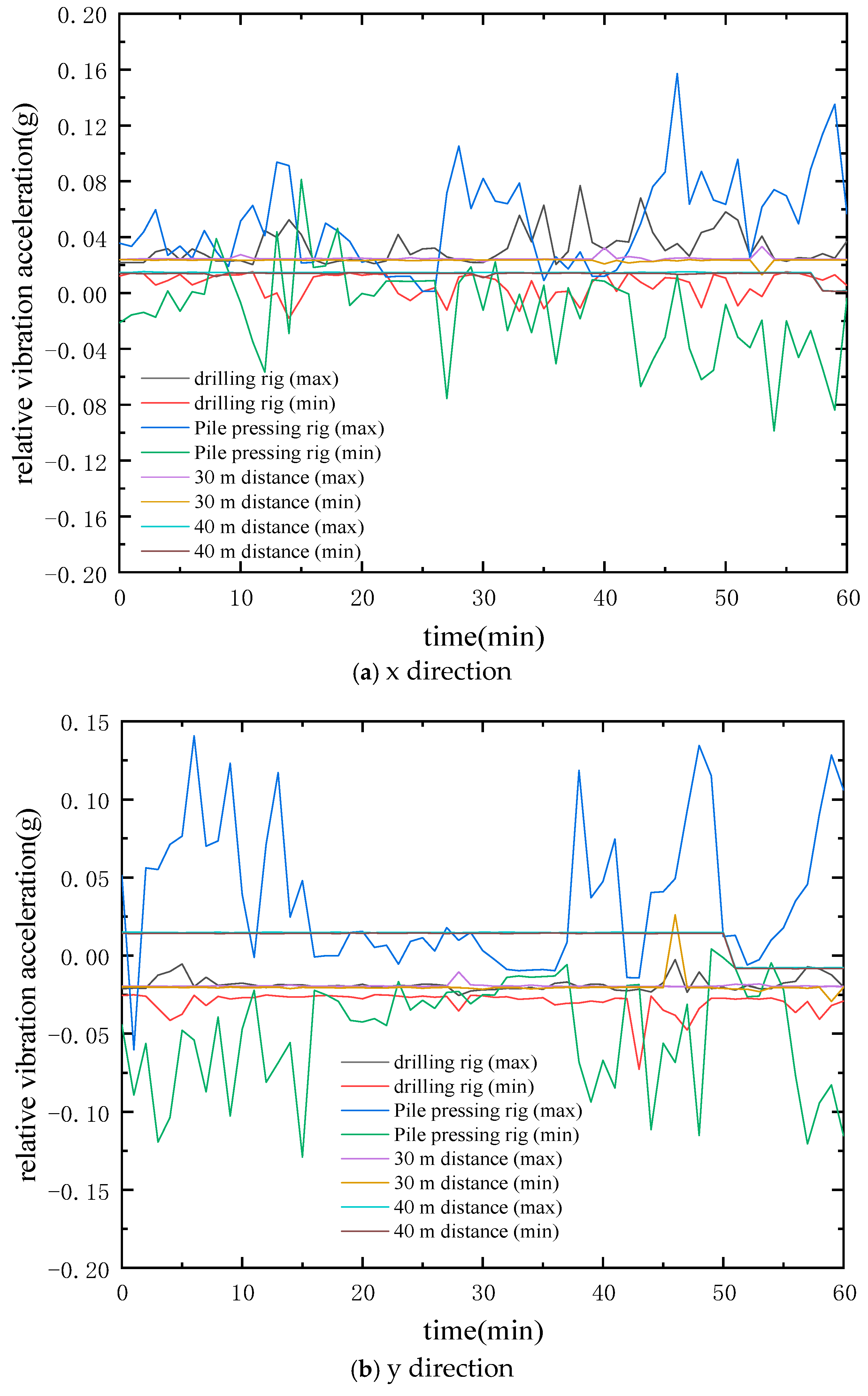

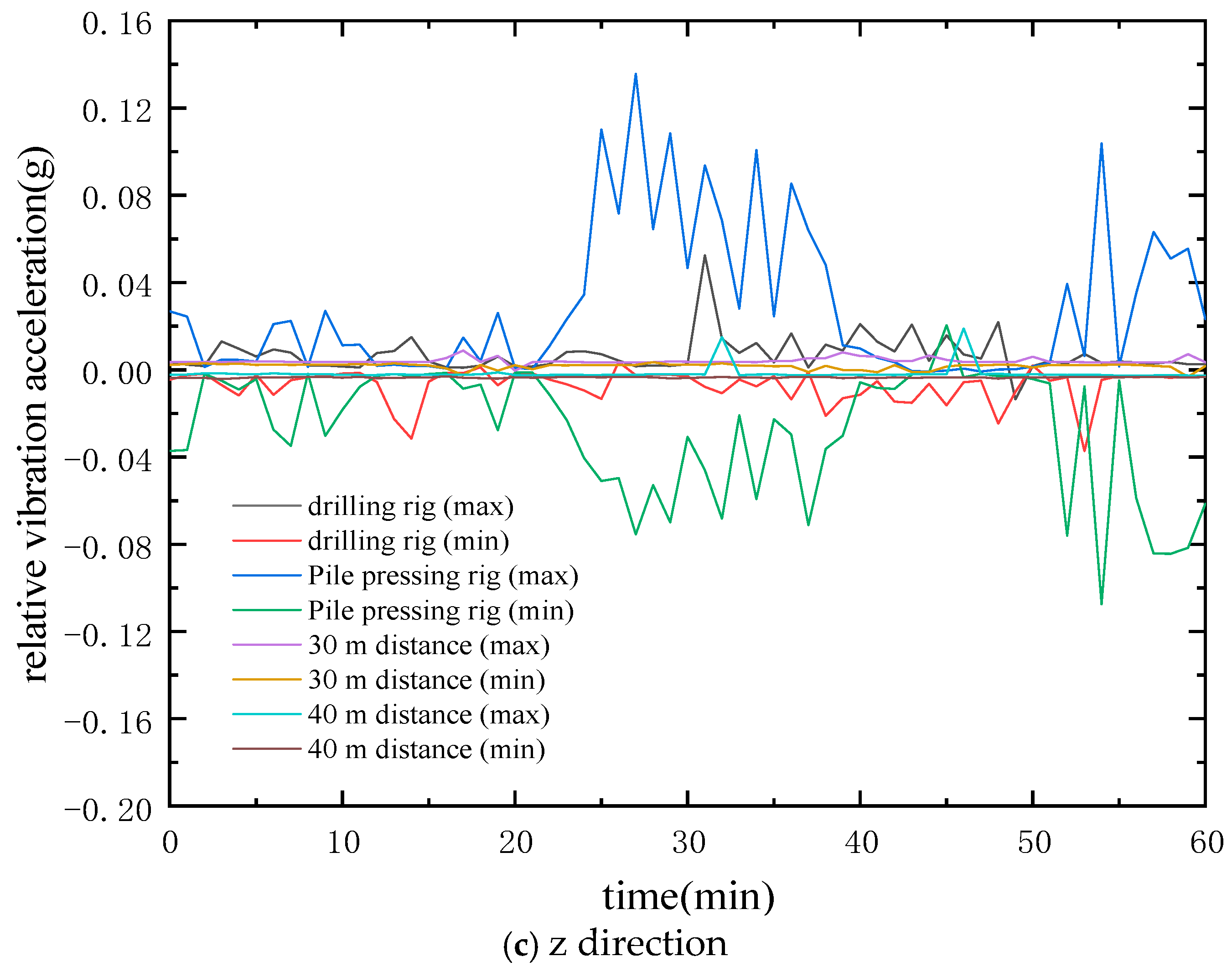

Under normal circumstances, on-site measurements are often affected by various interference factors, making it impractical to isolate vibrations from a specific construction stage. Therefore, the records also capture other vibrations occurring on the site. The relative vibration acceleration in all directions during the static drill-rooted energy pile construction phase is illustrated in

Figure 6.

During the pile-driving process, vibration acceleration typically ranges from 0.1 to 1.5 g. In contrast, the vibration generated by the static drilled pile energy system is significantly milder. The vibration intensity during the construction of the static drill-rooted pile energy system decreases with increasing distance from the construction equipment. As revealed in

Figure 6, the relative vibration acceleration in different directions during construction varies significantly with distance. At 30 and 40 m from the construction equipment, the vibration acceleration amplitude typically remains within 0.015 g, well below the discomfort threshold of 0.05 g, resulting in weak vibration perception and no discomfort. However, in areas closer to the construction equipment, especially during pile driving operations, the vibration acceleration exceeds 0.05 g at several intervals, which may cause mild discomfort, particularly if the vibration persists over time. The vibration acceleration generated by the drilling rig itself is relatively mild. Although it exceeds 0.05 g during a few periods, it does not cause significant discomfort. Overall, a greater distance from the vibration source significantly reduces its impact. However, at a closer distance, vibration reduction measures or shift work methods may be needed to reduce discomfort for the workers.

Based on the measured results, the vibration acceleration at a distance of 30 m during the static drill-rooted pile energy system construction is consistently maintained within 0.015 g. According to the vibration rating standard established in this study, this level of impact is rated as ‘‘Good’’. In response to the relatively low vibration impact score in this study, a series of technical and management mitigation measures can be considered to further improve its adaptability in densely populated areas. In terms of source control, the drill bit design and drive system can be optimized, and hydraulic static pressure is used instead of vibration impact; on the transmission path, vibration damping trenches or sheet pile barriers are set up between the vibration source and sensitive points, which can effectively reduce vibration wave energy; in terms of construction management, time avoidance and personnel shift systems for high-vibration processes are implemented. Engineering practice shows that these measures can significantly reduce the vibration acceleration at 30 m to less than 0.01 g, thereby raising the vibration score to the “excellent” level and further strengthening the comprehensive environmental friendliness of statically drilled energy piles.

3.4. Noise

During the installation and construction of static drill-rooted energy piles, some noise is generated; however, it is usually temporary and can be reduced through proper construction management and technical measures. When energy piles replace traditional air conditioning and heating systems in buildings, operational noise has minimal impact on residents, as the piles are typically installed underground or at a distance from residential areas.

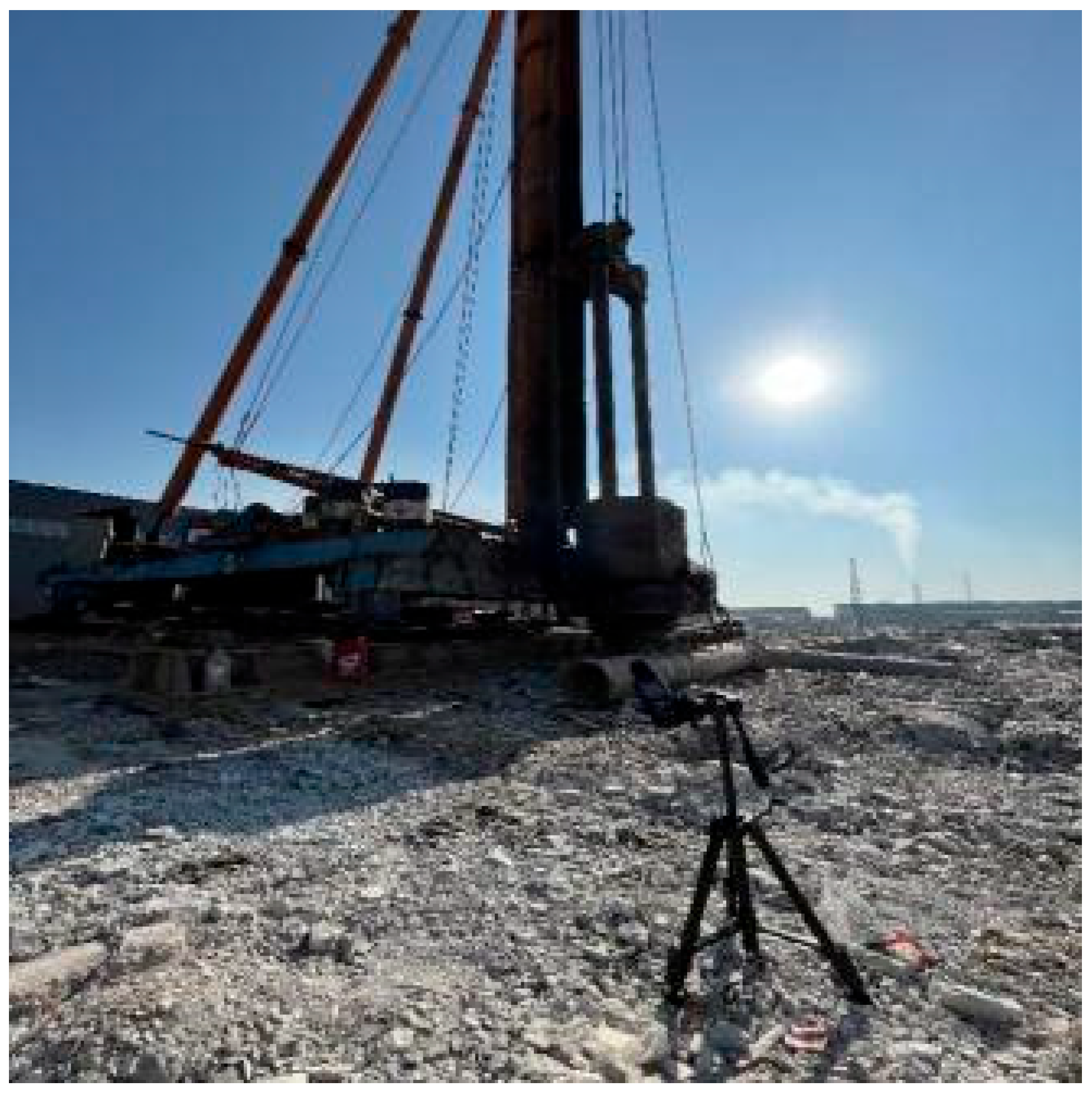

A Yuwen YW-532 decibel meter, with a measurement resolution of 0.1 dB and an accuracy of ±1.5 dB, was used for the noise measurements. The instrument supports both A- and C-weighted frequency and meets or exceeds the performance requirements for a Class 1 or Class 2 sound level meter, following GB/T 15173. The microphone was equipped with a windshield, and the instrument’s time-weighting setting was configured to the Fast (F) mode. Noise measurements were conducted at various distances from the pile machine—1, 5, 10 (near temporary structures), and 20 m (outside the site), with the measurement equipment set at a height of 1.2 m. Measurements were recorded using both tripod-mounted and handheld methods, as demonstrated in

Figure 7 and

Figure 8.

- 2.

Noise Evaluation

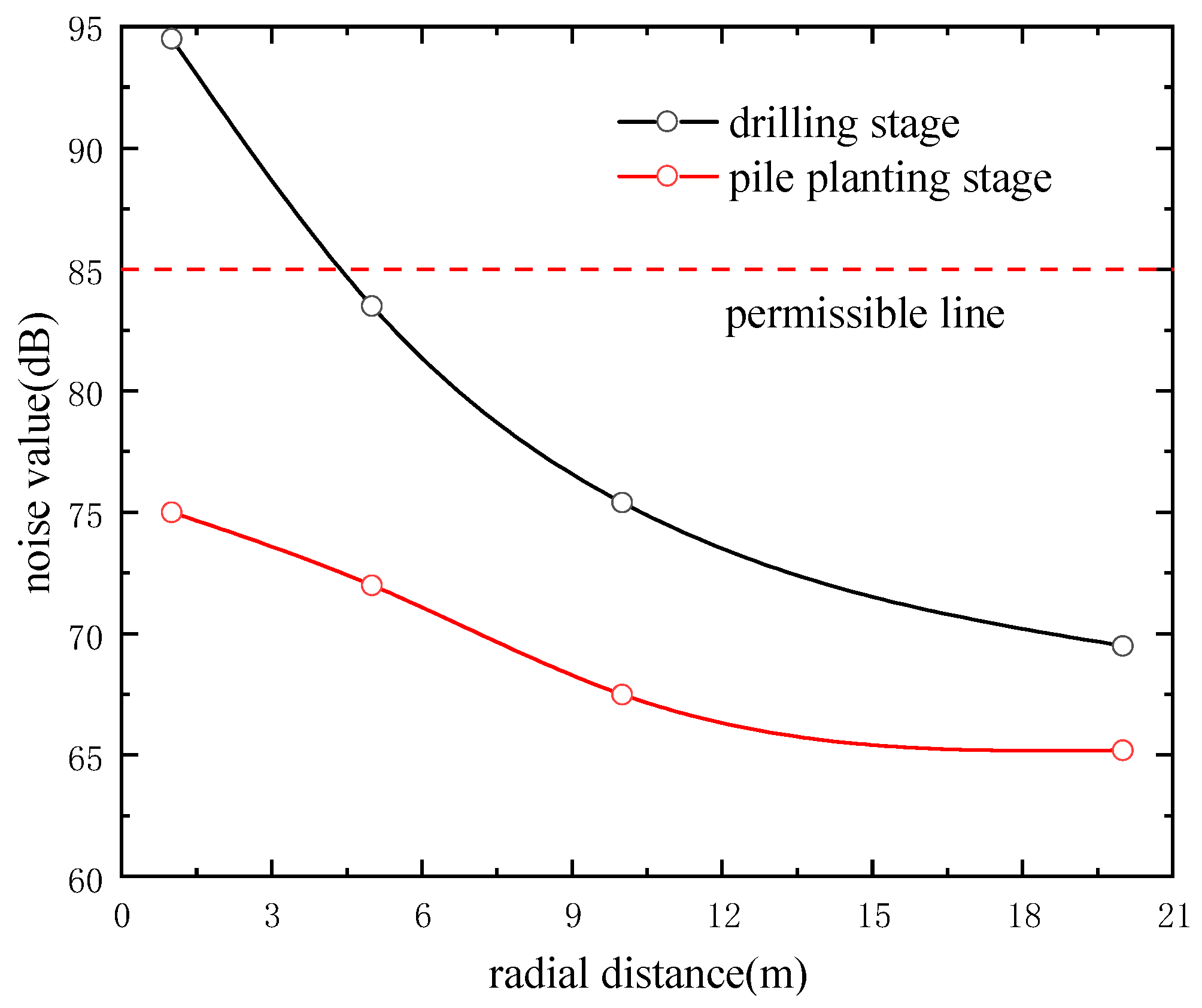

In general, on-site noise measurements are subject to various interfering factors, with ambient noise levels reaching up to 60 dB. Due to these conditions, it was impossible to isolate noise generated solely by the piling activity; therefore, the recorded data also included other site-related noise. The noise levels during the static drill-rooted energy pile construction phase are indicated in

Figure 9.

Pile hammering usually generates significant noise, with sound pressure levels reaching up to 100 dB, mainly due to the strong impact forces involved. In contrast, static drill-rooted energy piles adopt a gentler construction method, resulting in significantly lower levels of noise and vibration. This method involves drilling a borehole, placing the prefabricated pile into the hole using its weight, and then grouting to enhance the bond between the pile and the soil. This method causes minimal disturbance to the soil, effectively reducing vibration and noise during construction, and has a smaller impact on the surrounding environment. During construction, the noise from static drill-rooted energy piles mainly comes from the machine’s engine. While the noise during the drilling stage is relatively high, reaching 95 dB at 1 m, it drops below the emission limit at a distance of 5 m from the construction site.

According to the noise evaluation results, the noise level has attenuated to below 85 dB within 5 m of the construction point, and the noise control effect is rated as ‘‘Excellent’’.

3.5. Evaluation of Energy Conservation and Emission Reduction

3.5.1. Production Stage

According to the mechanical principles, there is an inverse relationship between pressure and the required bearing area. At a constant load, higher material strength allows for a reduced bearing area (i.e., cross-sectional area of the pile). In other words, high-strength concrete can support the same load with a smaller cross-section. Compared to normal concrete, high-strength concrete exhibits superior compressive strength, allowing for reduced material volume to support identical loads. Bored energy piles typically employ solid C30 or C40 grade concrete, resulting in greater material consumption and higher carbon emissions during production. In contrast, static drill-rooted energy piles utilize C80 or C100 high-strength concrete in tubular form. Although this type of concrete requires more cement, the overall concrete volume per pile is reduced due to smaller cross-sectional areas and thinner walls, ultimately lowering total carbon emissions.

The carbon emission factor of C30 is 262.39 kg CO

2/kg, [

28] and the carbon emission factor of C80 is 470 kg CO

2/kg. [

29] The corresponding carbon emission coefficients for various grades of concrete are detailed in

Table 12.

Assuming the same outer diameter pipe piles are used for both static drill-rooted energy piles and bored energy piles,

Table 13 presents the carbon emissions generated during their production stage.

The static drill-rooted energy pile significantly reduces carbon emissions due to its smaller volume and tubular design. Even with high-strength C80 concrete, its carbon emissions remain significantly lower than those of the traditional bored pile energy piles. With the same outer diameter, the static drill-rooted design requires less material and produces fewer emissions. Calculations reveal that static drill-rooted energy piles reduce carbon emissions by 22–45% compared to bored pile energy piles, making them a more environmentally friendly option.

3.5.2. Construction Stage

This study adopted the 2010 China Regional and Provincial Power Grid Average Carbon Emission Factor, which indicates that the carbon emission factor for electricity in Zhejiang Province is 0.6822 kg CO

2/kWh. The diesel carbon emission factor of 0.491 kg CO

2/L. [

29]

Table 14 lists the energy consumption per machinery shift during the construction of static drilling rooted energy piles and bored cast-in-place energy piles. The static drilling rooted energy piles are constructed using two types of equipment: the JB178B fully hydraulic crawler static composite pile machine and the intelligent pile planting machine ZM60, which are provided by Fujian Xiaming Heavy Industry Co., Ltd. in Quanzhou, Fujian, China, and Zhejiang Zhongrui Heavy Industry Technology Co., Ltd. in Ningbo, Zhejiang, China, respectively. The construction of bored cast-in-place energy piles, on the other hand, uses the XR220D rotary drilling rig, which is manufactured by XCMG Group in Xuzhou, China.

According to

Table 14, when the number of piles and pile depth are the same, the carbon emissions from static drill-rooted energy piles—constructed using electric-powered intelligent equipment and high-efficiency diesel pile drivers—are 12% lower compared to the bored energy piles.

3.5.3. Operation Stage

Table 15 presents the operational performance data of the static drill-rooted energy pile system, including the system’s average input power, inlet and outlet temperature difference, heat transfer fluid flow, heat transfer power, and energy efficiency ratio.

According to the ‘‘Performance Standards for Room Air Conditioners: GB/T 7725—2004,’’ [

30] the specified energy efficiency ratio (COP) for air-source heat pumps ranges from 2.50 to 2.70. The actual measured results in this study indicate that the COP of the static drill-rooted energy pile system during winter operation reaches 4.367, representing an improvement of 61.74–74.68% over the specified value. Assuming that both systems provide the same effective heat exchange—specifically 4.887 kW per hour—the power consumption of the static drill-rooted energy pile system is 1.119 kW, whereas the power consumption of the air-source heat pump ranges from 1.81 to 1.9548 kW. Using the static drill-rooted energy pile system saves 0.691–0.8358 kWh of energy per hour compared to the air-source heat pump, reducing CO

2 emissions by 0.471–0.57 kg per hour.

3.5.4. Evaluation of Energy Saving and Emission Reduction

The static drill-rooted energy pile demonstrates significant advantages in energy saving and emission reduction performance. Compared to traditional bored pile energy piles, this process has optimized material design and construction equipment energy consumption control. In the building material production stage; the use of high-strength hollow pipe pile design significantly reduces the concrete usage and carbon emissions per unit pile; achieving an overall emission reduction of 22–45%, earning a rate of ‘‘Good.’’ In the construction stage; the introduction of electric-driven intelligent equipment combined with high-efficiency diesel pile machines; effectively reduces mechanical energy consumption; achieving an energy consumption reduction of approximately 12%, also rated as ‘‘Good.’’ During the operation stage; the COP reaches 4.367; earning ‘‘Good’’ as rating. This COP is much higher than the average level of air-source heat pumps, demonstrating significant potential for long-term electricity savings and carbon emission reduction benefits

3.6. Comprehensive Environmental Impact Assessment and Score Summary

Based on the constructed environmental impact assessment system, this study systematically analyzed and comprehensively evaluated the environmental impact of the static drill-rooted energy pile throughout its entire lifecycle. The evaluation dimensions include excavated soil and slurry discharge, construction vibration, noise impact, and carbon emission reduction benefits (covering material production, construction, and operation stages). Actual engineering case data was used to quantify the environmental indicators, and weighted scores were assigned according to the dimension weight distribution table.

In terms of excavated soil and slurry discharge, the static drill-rooted energy pile reduces emissions by approximately 68% compared to the bored pile, with slurry discharge reduced by 60–70%, earning a rating of ‘‘Good’’ (4 points).

For construction vibration, the vibration acceleration is significantly below the threshold of discomfort, and only auxiliary vibration reduction measures are needed during close-distance operations, earning a rating of ‘‘Good’’ (3 points).

Regarding noise, although the noise peak is high, it attenuates quickly, and at a distance of 5 m, it can be controlled within the 85 dB limit, demonstrating a significant improvement compared to impact piling, earning a rating of ‘‘Excellent’’ (5 points).

For carbon emission reduction benefits, carbon emissions are reduced by 22–45% during the material production stage, by 12% during construction, and the COP during operation is 4.367, continuously reducing energy consumption and carbon emissions, demonstrating green advantages throughout the entire lifecycle, earning a ‘‘Good’’ (4 points) rating.

In summary, of the individual evaluation indicators, 1 received an ‘‘Excellent’’ score, and 3 received a ‘‘Good’’ score. The highest score was for noise control because the technology employs a ‘‘drill first, pile later’’ technique, significantly reducing construction noise. The lowest score was for vibration because the machinery uses large construction equipment, causing noticeable site vibration. Future reductions in vibration can be achieved through equipment development, further enhancing the environmental advantages of static drill-rooted energy piles.

Based on the weight distribution of each evaluation dimension in

Table 1 and using the weighted average method for comprehensive scoring, the overall environmental impact evaluation score for the static drill-rooted energy pile project is 4.0, earning a comprehensive rating of ‘‘Excellent.’’ This result indicates that the static drill-rooted energy pile has notable advantages in environmental friendliness and is suitable for environmentally sensitive areas such as coastal soft soil regions and urban geothermal development scenarios, with broad engineering adaptability and promotional value.