Abstract

Persistent regional inequalities in economic resource distribution pose a major obstacle to inclusive and sustainable development. In peripheral economies, structural vulnerabilities have been reinforced by long-standing reliance on extractive industries. This study examines the economic structure of Chile’s Atacama Region over a twenty-year period (2003–2023), focusing on sectoral specialization, structural concentration, and their implications for sustainability, territorial resilience, and long-term development. Expanding on prior empirical work (2011–2021), the research adopts a strategic diagnostic approach informed by endogenous growth theory and territorial knowledge management. Three structural indicators—the Theil, Entropy, and Herfindahl–Hirschman indexes—are applied to assess sectoral inequality, productive diversity, and value-added distribution. The results reveal a persistently concentrated and mining-dependent economy, with limited diversification, undermining sustainability and resilience. These findings highlight structural weaknesses that hinder progress toward a knowledge-based and sustainable economy, emphasizing the urgency of diversification strategies that reduce mining dependence and foster inclusive growth. By explicitly linking structural diagnostics to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs 8, 9, and 10), this study contributes empirical evidence for designing sustainability-oriented policies and advancing knowledge-driven development pathways in resource-dependent regions.

1. Introduction

Inequality in the distribution of economic resources across countries and regions remains a persistent and widely explored topic in economic research [1,2,3]. Although part of these disparities originates from deep-rooted historical and structural conditions, their interpretation is often shaped by simplified narratives that portray peripheral or smaller regions as inevitably trapped in dependency and underdevelopment [4,5,6]. More recent contributions have moved beyond this deterministic outlook, highlighting the potential of regional economic growth to reduce spatial inequalities and enhance overall social welfare [7,8,9]. Sustained regional growth not only drives higher per capita income and job creation but also plays a key role in fostering national cohesion and promoting more equitable development trajectories [10,11]. A deeper understanding of how territorial growth unfolds is therefore essential for the design of effective public policy, particularly in contexts marked by persistent disparities in productivity and living standards.

As suggested by New Economic Geography, the concentration of increasing returns in specific areas can lead to self-reinforcing cycles of economic agglomeration that are difficult to reverse without deliberate and well-crafted policy interventions [12]. A classical explanation of regional development, rooted in the theory of comparative advantage, emphasized productive specialization and trade efficiency based on relative cost structures [13,14]. While these ideas established a lasting foundation for analyzing regional production systems, they have been critically reassessed in light of endogenous growth theory and evolving conceptions of regional economic complexity. Contemporary scholarship increasingly challenges the notion that comparative advantages are static, emphasizing instead their capacity to be reshaped through learning, innovation, and proactive industrial policy [15,16]. In resource-dependent economies such as Chile, these debates are particularly salient: mining regions illustrate both the benefits of specialization and the structural risks of dependence, making them strategic cases for applying multi-indicator approaches that capture long-term dynamics of concentration and diversification.

Endogenous growth theories contend that regional development depends less on natural resource endowments and more on the cumulative impact of knowledge, human capital, technological progress, and robust institutional frameworks [17,18]. Achieving sustainable development therefore hinges on the ability to generate, absorb, and disseminate knowledge. This requires the strengthening of regional innovation ecosystems, greater investment in education and specialized training, and the promotion of collaborative networks involving universities, research institutions, firms, and governments [7,19,20]. Within this framework, knowledge management emerges as a critical lever for fostering collective learning and enabling endogenous innovation. The integration of structural indicators such as the Theil, Entropy, and Herfindahl–Hirschman indexes provides a rigorous methodological basis to analyze these dynamics, offering both theoretical insights and practical evidence for policy design [21].

Against this backdrop, it becomes particularly relevant to examine territorial cases where productive specialization has decisively shaped development trajectories. The Atacama Region in northern Chile provides a distinctive example. Historically regarded as the gateway to Chilean mining, its productive base is dominated by medium- and small-scale mining enterprises. In contrast, Antofagasta hosts the country’s largest copper corporations, whose overwhelming weight explains its extreme concentration. This structural divergence helps account for the differences in concentration and diversification indices observed between the two regions, illustrating how productive configurations translate into distinct development outcomes. This study builds on earlier work that offered a descriptive analysis of economic specialization in Atacama for the period 2011–2021 [22]. Expanding both the temporal scope and the analytical framework, it analyzes two decades of structural dynamics (2003–2023) through the combined lenses of endogenous growth theory and territorial knowledge management.

The central question guiding this study is: To what extent has Atacama’s pattern of economic specialization supported sustainable regional growth, or does the region require a new strategy—rooted in knowledge and innovation—to transition toward a more resilient and equitable development model? The primary objective is to empirically analyze the relationship between productive specialization and regional economic performance in Atacama, with particular attention to the potential of knowledge-based strategies. The main contribution is threefold. First, it connects sectoral economic analysis with regional innovation perspectives to address structural dependency. Second, it introduces, for the first time, a longitudinal multi-indicator approach (Theil, Entropy, and HHI) applied to Atacama’s economy, thereby strengthening the robustness of the results. Third, it establishes a benchmarking framework that situates Atacama within both its neighboring mining regions and the national economy. In doing so, the study not only contributes to the Chilean and Latin American literature on extractive dependence but also aligns with international debates on resource-dependent economies such as Peru, Australia, and South Africa. In summary, the evidence confirms that Atacama’s economy remains structurally concentrated around the mining sector, with persistently high levels of inequality and recurrent reversions from diversification back to mining dependence. Although phases of diversification emerged between 2012 and 2016, they were insufficient to alter the extractive model. The findings highlight the structural vulnerability of the region and underscore the urgency of knowledge-based development strategies that strengthen non-extractive sectors, foster intersectoral linkages, and promote sustainable endogenous growth aligned with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 8, 9, and 10 [23].

Research question and objectives. The central question guiding this study is whether Atacama’s pattern of economic specialization has supported sustainable regional growth or, alternatively, whether a knowledge-based strategy is required to foster resilience and reduce structural vulnerability. Our objectives are threefold: (i) to measure inequality, diversity, and concentration using Theil, E, and HHI; (ii) to identify temporal patterns of reconcentration and partial diversification over 2003–2023; and (iii) to interpret these dynamics through the lenses of endogenous development and regional knowledge systems to derive actionable policy insights.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

This study applies a quantitative structural analysis to evaluate the sectoral composition and degree of economic concentration in Chile’s Atacama Region over the 2003–2023 period. The methodological design draws on well-established indicators of inequality, diversity, and specialization, in line with recent developments in regional economic research [24,25,26,27].

The unit of analysis is the regionalized subtotal of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) at annual frequency, consistent with the classification of the Central Bank of Chile and the criteria established by the System of National Accounts 2008 (SNA 2008). The empirical scope adopts a longitudinal comparative perspective (2003–2023), enabling the identification of cyclical episodes of reconcentration and partial diversification. This design supports a policy-relevant interpretation anchored in endogenous development theory and regional innovation systems.

The reliability of this assessment is reinforced by the administrative continuity of the Atacama Region, which—unlike other Chilean territories such as Los Ríos [28], Arica and Parinacota [29], or Ñuble [30]—has maintained consistent territorial boundaries over the past two decades. This stability ensures coherent spatial comparisons across time in the analysis of its productive structure.

2.2. Structural Indicators

To capture the key structural features of the regional economy, this study employs three widely established indicators: the Theil Index (T), the Normalized Entropy Index (E*), and the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (HHI). Collectively, these metrics provide complementary insights into inequality, productive diversity, and sectoral concentration within the regional Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

- Theil Index (T): Originally developed within information theory, it measures weighted inequality in the distribution of value added across economic sectors [31]. Higher values indicate a greater degree of concentration.

- Normalized Entropy Index (E*): Derived from Shannon entropy, it normalizes entropy values to a 0–1 scale by dividing by the logarithm of the number of sectors. This enables consistent comparisons across time and regions, and is widely used to assess structural diversity in regional economies [32].

- Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (HHI): Calculated as the sum of squared sectoral shares, it provides a robust measure of concentration and is extensively applied in studies of market structure and competition policy [33].

The theoretical underpinnings and interpretive scope of these indicators are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Structural Indicators for Analyzing Inequality, Diversity, and Sectoral Concentration.

The theoretical foundations of these structural indicators are consistent with previous applications in regional inequality and concentration analysis [37,38,39].

The GDP data were obtained from the Central Bank of Chile, expressed in current prices and harmonized to the 2018 accounting base using sequential splicing techniques, in accordance with internationally recommended practices for constructing consistent historical time series [40,41]. The statistical analysis focused exclusively on the regionalized subtotal of GDP, deliberately excluding extra-regional components and indirect taxes, in line with the territorial comparability criteria established by the System of National Accounts 2008 [42]. In addition, the methodological framework adopted is consistent with approaches to measuring concentration and inequality in evolving economic systems [33]. To maintain temporal consistency in sectoral classification, the item “Less: Imputed bank services” was reallocated to the Financial and Business Services sector for the 2003–2009 period. From 2018 onward, the data were fully comparable. Splicing was applied using conversion factors in crossover years (2003, 2008, 2013, and 2018), preserving the relative sectoral structure.

Robustness checks were conducted to ensure that the results are not dependent on a specific methodological choice. In addition to the Theil Index [31], the Normalized Entropy Index [32], and the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index [33], complementary calculations were performed using the Florence specialization index [34]. The patterns obtained with this alternative measure were consistent with those derived from the integrated framework, confirming the persistence of structural concentration in the Atacama Region [35]. Furthermore, the series was divided into two subperiods (2003–2010 and 2011–2023) to test stability across different phases of the copper price cycle, with results showing robust concentration patterns in both periods [36].

In sum, the combined use of these indicators, complemented by robustness checks, ensures analytical consistency and strengthens the reliability of the findings.

2.3. Data Sources

The GDP data were obtained from the Central Bank of Chile, expressed in current prices and harmonized to the 2018 accounting base using sequential splicing techniques, in accordance with internationally recommended practices for constructing consistent historical time series [43]. The analysis considered only the regionalized subtotal of GDP, deliberately excluding extra-regional components and indirect taxes, in line with the comparability criteria established by the 2008 System of National Accounts [42].

To ensure temporal consistency in sectoral classification, the item “Less: Imputed bank services” was reallocated to the Financial and Business Services sector for the 2003–2009 period. From 2018 onward, the data were fully comparable. Splicing was applied using conversion factors in crossover years (2003, 2008, 2013, and 2018), preserving the relative sectoral structure. Robustness checks were conducted by dividing the series into two subperiods (2003–2010 and 2011–2023), which confirmed the persistence of concentration patterns across different phases of the copper price cycle.

2.4. Analytical Framework

All calculations were performed in Python 3.10, using sectoral shares of regional GDP as the base variable. For each year, a relative share vector was constructed as:

where represents the value added of sector and denotes total regional GDP. The analysis consistently considered twelve economic sectors, based on the official classification scheme of the Central Bank of Chile [44], which remained unchanged during the study period.

This study applies a structural analytical framework built on three well-established indicators: the Theil Index (T), the Normalized Entropy Index (E*), and the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (HHI). These indicators capture inequality, productive diversity, and sectoral concentration, offering a comprehensive perspective on the regional economy. Unlike traditional approaches such as shift–share analysis, which decompose regional growth into national, sectoral, and local components but often overlook intra-regional inequality and productive diversity [45,46,47], this framework explicitly incorporates dimensions of structural resilience that are essential for assessing sustainability in resource-dependent regions.

In line with endogenous development theory and international debates on regional sustainability [48,49,50,51], this approach provides robust and comparable assessments of structural change. It allows for a more accurate evaluation of resilience, vulnerability, and long-term sustainability in peripheral economies such as Atacama, while also delivering actionable insights for policy design. Finally, although this study does not compute the Balassa Index, previous empirical research highlights the role of revealed comparative advantage in shaping specialization dynamics [36], helping to contextualize Atacama’s productive concentration within broader regional and international patterns.

3. Results

Following the methodological framework outlined in Section 2.4, the results are presented through the evolution of three complementary indicators—the Theil Index (T), the Normalized Entropy Index (E*), and the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (HHI)—for the Atacama Region during 2003–2023. All calculations are based on a consistent breakdown of twelve economic sectors, according to the official classification scheme of the Central Bank of Chile [44]. This integrated approach enables a systematic assessment of inequality, productive diversification, and sectoral concentration across time, ensuring comparability and analytical robustness.

3.1. Theil Index: Structural Inequality in Regional GDP

The Theil Index was applied to measure structural inequality in the distribution of regional Gross Domestic Product (GDP), both in its aggregate and sectoral forms. This metric captures overall output concentration while also identifying which sectors contribute most to inequality—or conversely, which act as stabilizers by offsetting structural imbalances. Sectoral decomposition of the Theil Index is a well-established approach in the study of productive structures and regional disparities [24,31,52], and has also been discussed in broader methodological contributions to concentration analysis [36].

3.1.1. Global Theil Index (2003–2023)

Following the analytical framework described in Section 2.4, the Global Theil Index was computed annually for the 2003–2023 period as (Equation (1)):

where

- T: Theil Index;

- n = 12, total number of economic sectors, constant throughout the analysis period;

- : relative share of sector i in total regional GDP;

- : Expected share under perfect equality (1/n if all units have the same weight);

- : natural logarithm.

This methodological consistency ensures that changes in the index reflect genuine structural transformations rather than variations in classification.

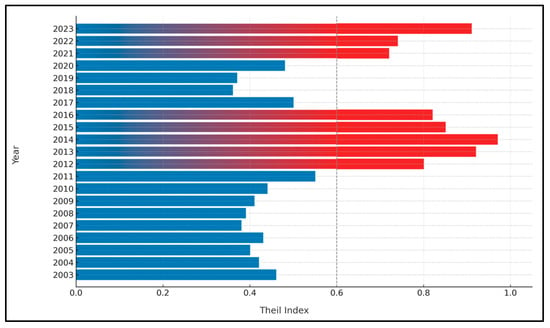

Figure 1 summarizes the evolution of the Global Theil Index for the Atacama Region. Results show persistently high values, averaging above 0.6 across the two-decade period. Such levels reveal a strong dependence on a narrow set of sectors, underscoring the structural vulnerability of the regional economy to external shocks affecting its leading industries. Moreover, the non-linear trajectory of the index suggests the absence of a sustained path toward diversification, reinforcing concerns about the resilience and long-term sustainability of Atacama’s productive structure.

Figure 1.

Global Theil Index in Atacama (2003–2023): Evidence of Critical Structural Concentration. Persistent Theil values above 0.6 confirm Atacama’s structural vulnerability and highlight the urgency of diversification policies. Source: Authors’ elaboration based on data from the Central Bank of Chile. Calculations performed in Python using harmonized GDP series (2018 base).

3.1.2. Sectoral Decomposition of the Theil Index

Building on the formulation presented in Section 2.4, the contribution of each sector to the overall Theil Index was calculated as (Equation (2)):

where

- : contribution of sector to the Theil Index;

- : total number of economic sectors (constant throughout the analysis period);

- : relative share of sector in total regional GDP;

- : expected share under perfect equality;

- : natural logarithm.

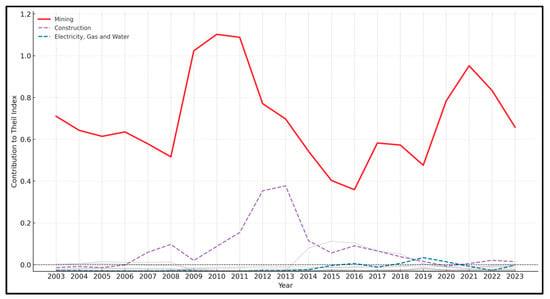

Figure 2 presents the sectoral decomposition of the Theil Index for the Atacama Region. Results show that the mining sector dominates the distribution, with contributions persistently above 0.4 and even exceeding 1.0 during the 2009–2011 period, as well as in 2021–2022. This persistent dominance reflects the extractive enclave character of Atacama’s economy. Other sectors, such as construction and electricity, gas, and water, occasionally record positive contributions, usually linked to infrastructure investments and the expansion of renewable energy. By contrast, activities including fishing, agriculture and forestry, manufacturing, and public administration exhibit negative or marginal contributions, effectively acting as stabilizers within the regional structure.

Figure 2.

Sectoral Dynamics of Structural Concentration in Atacama (2003–2023): Mining as the Critical Driver of the Theil Index. Mining’s disproportionate contribution (above 1.0 during copper booms) underscores the enclave nature of Atacama’s economy, while the stabilizing role of non-extractive sectors reveals untapped potential for diversification. Source: Authors’ elaboration based on data from the Central Bank of Chile. Calculations performed in Python using harmonized GDP series (2018 base).

The evidence confirms the structural dependence of Atacama’s GDP on mining. The sharp decline in mining’s contribution between 2014 and 2020, followed by a strong rebound in 2021–2022, highlights the region’s acute sensitivity to fluctuations in international copper prices. These dynamics reinforce the notion that Atacama’s development trajectory remains locked into an extractive enclave model. At the same time, the consistent equalizing role of non-extractive sectors underscores their untapped potential to support diversification and resilience. Strengthening these activities could contribute to a more balanced and sustainable productive base in the long run.

3.2. Normalized Entropy Index: Productive Diversification

The Normalized Entropy Index (E*) is widely recognized as a robust tool for assessing the degree of diversification within a region’s productive structure. By quantifying the relative distribution of value added across economic sectors, it captures the extent of sectoral balance and highlights structural asymmetries. This capacity makes it a valuable indicator for analyzing territorial resilience to external shocks and for identifying sustainable development trajectories.

A substantial body of literature identifies sectoral diversification as a key driver of regional economic stability, emphasizing that regions with broader productive bases tend to be more resilient to economic downturns and better positioned to sustain balanced growth trajectories [26,53].

Methodological refinements have further advanced the application of E*, particularly through entropy-based weighting techniques applied in sustainability assessments. Unlike traditional composite indicators, E* offers a more nuanced measure of vulnerability to exogenous shocks by revealing levels of concentration and structural dependency that may limit adaptive responses [27].

As previously noted, the relevance of E* is also grounded in strong theoretical traditions, particularly evolutionary economics and economic geography. Within these perspectives, concepts such as related variety and smart specialization emphasize that productive diversity is not random but emerges from shared technological capabilities and common knowledge bases, which enhance regional resilience and adaptability [32]. From this standpoint, the application of E* provides an empirical bridge between productive structures and endogenous development trajectories, integrating measures of concentration, diversity, and inequality into a coherent framework for territorial analysis.

3.2.1. Calculation and Trends of the Entropy Index

As defined in Section 2.4, the Normalized Entropy Index was calculated annually for 2003–2023 using the following expression (Equation (3)):

where

- : Normalized Entropy Index;

- : total number of economic sectors (constant throughout the analysis period);

- : relative share of sector in total regional GDP;

- : natural logarithm.

The E* index ranges from 0 to 1. Values approaching 1 indicate greater diversification—i.e., a more balanced distribution of value added across sectors—while values near 0 reveal a high degree of concentration in a limited number of industries. This bounded structure allows for meaningful comparisons of economic configurations across regions and time periods. Moreover, because the index is normalized by the number of sectors, it remains comparable across different territorial units regardless of their economic composition [53].

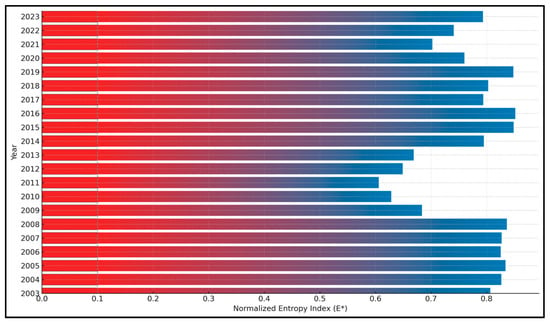

Figure 3 illustrates the evolution of the Normalized Entropy Index for the Atacama Region between 2003 and 2023. The results reveal that diversification levels have remained relatively moderate, with only slight increases during periods of infrastructure expansion and renewable energy development. However, the index has not shown a sustained upward trajectory, suggesting that the regional economy continues to exhibit significant structural dependence on a limited set of sectors. This pattern underscores the vulnerability of Atacama’s productive base to external shocks and highlights the need for policies aimed at strengthening diversification as a pathway toward resilience and sustainable development.

Figure 3.

Evolution of the Normalized Entropy Index in the Atacama Region (2003–2023): Implications for Economic Diversification and Policy. The results reveal Atacama’s moderate diversification trajectory, with only temporary increases during infrastructure and renewable energy expansions. The absence of a sustained upward trend underscores the region’s dependence on a narrow set of sectors and the urgency of policies that foster resilience through broader productive structures. Source: Authors’ elaboration based on data from the Central Bank of Chile. Calculations performed in Python using harmonized GDP series (2018 base). Higher values of the Normalized Entropy Index (E*) indicate greater economic diversification, while lower values reflect concentration in a few sectors.

3.2.2. Interpretation: Cyclical Dynamics and Structural Adjustment

Between 2003 and 2008, the entropy index remained at relatively high levels, suggesting a moderately diversified sectoral structure despite the historical dominance of mining. This pattern indicates that other sectors—such as industry, commerce, and services—continued to hold a meaningful share of regional GDP.

From 2009 to 2012, however, the index declined sharply, signaling a process of productive reconcentration. This shift coincided with the global copper price boom, which disproportionately increased the mining sector’s contribution. Starting in 2013, the index shows a gradual recovery, peaking in 2016 at 0.85—possibly reflecting productive promotion policies or structural adjustments following the mining cycle.

During the 2020–2021 biennium, the index dropped again, reaching 0.70—likely influenced by the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on sectors such as commerce and tourism. In 2023, the index rose to 0.79, indicating a partial recovery in regional sectoral diversity.

3.3. Herfindahl–Hirschman Index: Sectoral Concentration

The Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (HHI) is one of the most widely recognized metrics for quantifying economic concentration, extensively applied in studies of industrial organization and regional economics. The indicator was first applied empirically by Herfindahl in his doctoral dissertation on the U.S. steel industry [54], although its conceptual foundations were introduced earlier by Hirschman [38], who linked economic concentration to trade asymmetries. Building on these early contributions, the HHI has evolved into a standard measure of market and sectoral concentration.

Methodologically, the index is calculated as the sum of squared sectoral shares, which allows it to capture both the number of active sectors and the inequality in their relative sizes. This dual sensitivity makes the HHI particularly suitable for assessing productive structures where a small number of sectors dominate the economy. Its application is especially relevant in contexts where high concentration reflects structural dependence on natural resources or limited economic diversification—as is often the case in regions characterized by mono-dependent productive structures [55].

3.3.1. Calculation of the HHI and Temporal Trends

According to the methodological framework outlined in Section 2.4, the HHI was estimated annually for 2003–2023 as (Equation (4)):

where

- : Herfindahl–Hirschman Index;

- : value added of sector ;

- : total regional GDP;

- : total number of economic sectors (constant throughout the analysis period).

This formulation assigns greater weight to larger sectors, capturing both the number of active sectors and the inequality in their relative sizes. The index ranges from 1/n (in this case, 1/12 ≈ 0.083, reflecting maximum diversification) to 1 (absolute concentration in a single sector).

Owing to these properties, the HHI provides a concise summary of the degree of structural specialization or diversification within a regional economy. Its application is well established in the literature on territorial development and industrial organization, serving as a key tool for analyzing structural change—particularly in resource-dependent regions where one sector tends to dominate economic activity.

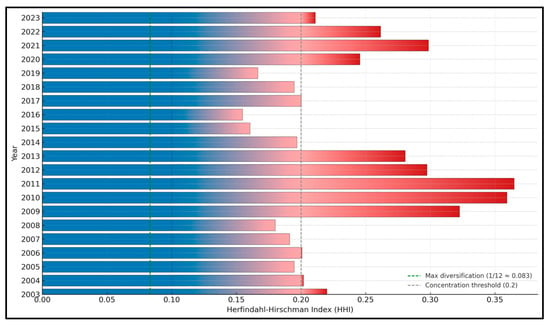

Applied to the Atacama Region over the 2003–2023 period, the HHI allows for an assessment of whether the regional economy has advanced toward greater diversification or reinforced its dependence on mining. As shown in Figure 4, the index remains consistently high, indicating persistent sectoral concentration with only limited fluctuations over time. These results highlight the structural dominance of mining and raise concerns about the region’s vulnerability to external shocks.

Figure 4.

Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (HHI) in Atacama (2003–2023): Persistent Sectoral Concentration Beyond the Diversification Threshold. Results show that Atacama’s HHI has remained consistently high over two decades, confirming the structural dominance of mining and the region’s vulnerability to external shocks. This pattern underscores the need for policies that foster diversification and strengthen economic resilience. Source: Authors’ elaboration based on data from the Central Bank of Chile. Calculations performed in Python using harmonized GDP series (2018 base). Values above 0.2 denote significant structural concentration.

3.3.2. Recent Patterns and Structural Reconcentration

Between 2003 and 2008, the HHI fluctuated between 0.18 and 0.22, a range typically associated with moderate concentration, suggesting that the Atacama Region maintained a relatively diversified productive structure despite the historical dominance of mining. Starting in 2009, however, the index rose sharply, reaching its historical peak of 0.365 in 2011—a level consistent with high concentration—reflecting the growing dominance of the mining sector during the global copper price boom.

Following this peak, the index gradually declined between 2012 and 2016, indicating a partial diversification process that may have been supported by productive promotion policies or structural adjustments in response to the mining cycle. Nonetheless, between 2020 and 2022 the HHI increased again, stabilizing in the range of 0.26 to 0.29, signaling a renewed phase of structural reconcentration likely driven by a resurgence in mining activity and the limited integration of non-extractive sectors.

By 2023, the HHI decreased to 0.211, placing it once more in the moderate concentration range. Although this represents a significant improvement compared to the 2011 peak, it also confirms the region’s persistent dependence on mining. This trajectory underscores the urgency of implementing public policies aimed at strengthening productive diversification, with the objective of reducing structural vulnerability and enhancing long-term regional resilience.

4. Discussion

4.1. Synthesis of Structural Indicators

The empirical results confirm the persistence of a highly concentrated productive structure in the Atacama Region, largely driven by mining. The three indicators applied—the Theil Index, the Normalized Entropy Index (E*), and the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (HHI)—offer a consistent and multidimensional perspective of this imbalance.

Theil values consistently above 0.6 confirm a high degree of inequality in the distribution of regional GDP across sectors [24,31,52]. The Entropy Index reveals cyclical patterns of reconcentration during mining booms [26]. Likewise, the HHI, with peaks exceeding 0.36, reflects periods of strong sectoral dominance and structural concentration [53,54].

According to international benchmarks, Theil values above 0.6 are considered evidence of entrenched structural inequality [56,57,58], while HHI values exceeding 0.36 are generally classified as thresholds of high concentration [35,57]. The fact that Atacama persistently surpasses both thresholds underscores the fragility of its productive structure and reinforces the diagnosis of structural dependence.

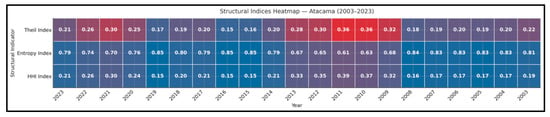

4.2. Integrated Visualization Through the Heatmap

Beyond the individual indicators, the heatmap (Figure 5) reinforces the consistency of these findings. By integrating the three indices into a single visualization, it clearly highlights the synchronicity between mining cycles, declining productive diversity, and rising sectoral inequality.

Figure 5.

Structural Concentration and Diversification in Atacama (2003–2023): Evidence from Theil, Entropy, and HHI Indices. The integrated heatmap reveals persistent structural stress in Atacama’s economy, with Theil values consistently high, entropy declining during copper booms, and HHI peaking in periods of reconcentration. These dynamics confirm the fragility of the regional model and reinforce the urgency of diversification and knowledge-based strategies aligned with the SDGs. Source: Authors’ elaboration based on data from the Central Bank of Chile (Regional Accounts, 2003–2023), harmonized at current prices using the 2018 accounting base. Calculations and visualization performed in Microsoft Excel.

This dynamic representation enables a comparative reading of structural trends over two decades, making explicit the vulnerabilities of an economy whose trajectory remains closely tied to fluctuations in mining activity [47,48].

4.3. Comparative Perspective: National and International

These findings align with analyses of other Chilean regions—particularly Antofagasta and Coquimbo—where extractive specialization has similarly constrained productive linkages, technological spillovers, and local innovation capacity [22,49,57].

From an international perspective, comparable dynamics have been observed in Peru [50], Sub-Saharan Africa [7], and several resource-dependent economies in Asia [46]. In Latin America, contemporary scholars emphasize that extractive enclaves perpetuate dependency and structural vulnerability [59]. For example, Gudynas [60] argues that “neo-extractivism” reinforces external dependence, weakens institutional capacity, and limits opportunities for endogenous development.

Peru provides additional evidence on the management of extractive rents: its Fiscal Stabilization Fund has been used to mitigate volatility in public revenues derived from mining and hydrocarbons [61]. In Colombia, historical analyses of mining and productive linkages underscore both the opportunities and the limits of sector-based diversification [62].

By contrast, the experiences of Australia and Canada stand out as more consolidated examples of resource-dependent economies that have partially reduced extractive dependence. In these countries, sovereign wealth funds have been established [63], and mining-related service clusters have been developed [64]. These experiences illustrate that diversification pathways are feasible when supported by deliberate and sustained policy interventions.

The broader literature on enclave economies consistently shows that resource-driven growth reproduces structural inequality, undermines innovation systems, and constrains development opportunities [27,50]. In this sense, Atacama’s trajectory is not exceptional but rather illustrative of the wider challenges faced by peripheral, resource-dependent regions.

Beyond these national and international comparisons, it is also important to verify whether the results presented here are robust to alternative methodological approaches and temporal segments. To address this, additional robustness checks were conducted, as detailed below.

The robustness of the findings is further confirmed by the consistency of results across alternative indicators and temporal segments. The Florence specialization index produced patterns that were aligned with those derived from the Theil, Entropy, and HHI framework, reinforcing the evidence of persistent concentration. In addition, sensitivity tests comparing pre-boom (2003–2010) and post-boom (2011–2023) periods demonstrated that the observed structural vulnerabilities are not limited to a specific copper cycle. These results are also consistent with external evidence reported by ECLAC (2018) and the Central Bank of Chile, which highlight the enduring fragility of mining-dependent regional economies. Taken together, these validations strengthen the reliability of the empirical conclusions presented in this study.

Taken together, the comparative evidence confirms that Atacama’s structural vulnerabilities are neither isolated nor accidental but rather consistent with the dynamics of resource-dependent regions worldwide. Latin American cases such as Peru and Colombia highlight the risks of fiscal and productive dependence, while the contrasting experiences of Australia and Canada demonstrate that diversification is possible when backed by strong institutions, sovereign wealth mechanisms, and innovation-driven clusters. Within Chile, Antofagasta illustrates the extreme costs of enclave dependence, whereas Coquimbo offers a closer example of how non-extractive sectors can stabilize regional economies. These contrasts reinforce the conclusion that Atacama occupies an intermediate but fragile position: too dependent on mining to achieve resilience, yet with untapped opportunities in renewable energy, agriculture, and knowledge-based services. The lesson is clear—without deliberate and sustained policy interventions, the region risks perpetuating enclave dynamics, but with strategic governance and diversification efforts, it could reposition itself as a more resilient and sustainable economy.

5. Conclusions

The analysis of Atacama’s economic structure during 2003–2023 confirms the persistence of a development model dominated by extractive specialization. The application of the Theil Index, the Normalized Entropy Index (E*), and the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (HHI) reveals consistently high levels of structural inequality, limited diversification, and recurrent reconcentration cycles.

The integrated heatmap visualization reinforces these findings by capturing the synchronicity between copper cycles, declining productive diversity, and rising concentration. This dynamic view highlights the fragility of Atacama’s productive base and its vulnerability to external shocks.

Two main conclusions follow. First, Atacama’s economy remains structurally dependent on mining, with entrenched imbalances that undermine resilience and inclusive growth. Second, overcoming these vulnerabilities requires deliberate diversification strategies aligned with knowledge-based development and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs 8, 9, and 10). Strengthening non-extractive sectors, fostering intersectoral linkages, and consolidating institutional capacity are essential steps to reposition the region on a more resilient and sustainable trajectory.

5.1. Integrated Analysis: Heatmap of Structural Indicators

The heatmap (Figure 5) integrates the trajectories of the three indicators, providing a comprehensive view of structural dynamics in Atacama. Theil values remain consistently high, particularly during the 2009–2012 copper boom. In the same period, the Entropy Index declined sharply, reflecting reduced productive diversity, while the HHI peaked, confirming the dominance of mining activities.

Between 2012 and 2016, the indicators reveal a modest rebalancing, with diversification improving slightly but insufficient to alter the extractive trajectory. More recently, between 2020 and 2022, entropy declined again while the HHI increased, signaling renewed structural reconcentration. By 2023, entropy rebounded marginally and the HHI moderated, but persistently high Theil values confirm that structural inequality remains entrenched.

Taken together, the integrated evidence underscores the fragility of Atacama’s economic model. Short-term fluctuations in mining output continue to translate directly into structural imbalances, undermining resilience and constraining sustainability. From a broader perspective, the results highlight the urgency of implementing deliberate diversification and knowledge-based strategies explicitly aligned with the Sustainable Development Goals—SDG 8 (decent work and sustained growth), SDG 9 (innovation and sustainable industrialization), and SDG 10 (reduction of inequalities). Without such measures, the region risks perpetuating enclave dynamics and persistent vulnerabilities; with them, Atacama could strengthen resilience, foster inclusive growth, and transition toward a more sustainable and knowledge-driven development pathway.

5.2. Comparison with Regional and International Evidence

The results align with empirical evidence from Chile’s mining regions—particularly Atacama—which exhibit weak intersectoral spillovers, shallow integration into regional value chains, and high vulnerability to fluctuations in international commodity prices [22]. International evidence further confirms that resource-dependent and enclave economies often share these dynamics, characterized by persistent structural inequality, low innovation capacity, and limited opportunities for endogenous growth [7,50]. Viewed through a sustainability lens, these comparative cases highlight not only the risks of models centered on resource dependence but also the urgency of advancing diversification policies, resilience-oriented strategies, and knowledge-based development pathways aligned with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [57].

Moreover, each structural indicator can be directly linked to specific Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): Theil values reflect persistent inequalities (SDG 10) [57,65]. Entropy captures dynamics of productive diversity and innovation (SDG 9) [66], and HHI highlights the risks to sustained and inclusive growth (SDG 8) [67]. This mapping reinforces the policy relevance of the findings by connecting empirical indicators with global policy agendas.

To reinforce this comparative perspective, Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4 summarize structural concentration and diversification indicators for the Atacama Region, its contiguous regions (Coquimbo to the south and Antofagasta to the north), and Chile at the national level. This benchmarking exercise underscores Atacama’s persistent concentration relative to both its neighboring regions and the national average, providing empirical support for the broader structural challenges identified in this study.

Table 2.

Theil Index (2003–2023): Comparative Evidence for Atacama, Neighboring Regions, and Chile. Atacama shows persistently higher structural concentration than Coquimbo and Chile as a whole, though lower than Antofagasta, underscoring its intermediate yet vulnerable position.

Table 3.

Normalized Entropy Index (2003–2023): Comparative Evidence for Atacama, Neighboring Regions, and Chile. Entropy results confirm Chile and Coquimbo as the most diversified, while Atacama remains moderately diversified, surpassing only Antofagasta.

Table 4.

Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (HHI), 2003–2023: Comparative Evidence for Atacama, Neighboring Regions, and Chile. HHI values highlight Antofagasta as the most concentrated economy, with Atacama also above the diversification threshold, reinforcing its structural vulnerability compared to Coquimbo and Chile.

Across all three indicators, Chile consistently emerges as the most diversified economy, followed by the Coquimbo Region. In contrast, Atacama displays higher levels of structural concentration, surpassed only by Antofagasta, which appears as the most concentrated economy. This divergence reflects their distinct productive bases: Atacama, historically regarded as the gateway to Chilean mining, is dominated by medium- and small-scale enterprises, while Antofagasta hosts the country’s largest copper companies, whose overwhelming weight explains its extreme concentration.

These structural differences are clearly reflected in the three indices—Theil, Entropy, and HHI—placing Atacama in an intermediate but still vulnerable position. This comparative evidence highlights the urgency of advancing policies that not only promote productive diversification but also strengthen intersectoral linkages and enhance territorial resilience. Beyond its diagnostic value, the benchmarking exercise provides a practical tool for policymakers, enabling Atacama’s performance to be systematically evaluated against neighboring mining regions and the national economy. Such evidence-based comparisons are critical for designing targeted diversification strategies that move the region away from enclave dependence and toward a more balanced, resilient, and knowledge-based development pathway.

5.3. Policy Implications

The structural risks identified in Atacama demand an urgent rethinking of regional development strategies. Persistent reliance on mining undermines resilience, restricts employment creation, and perpetuates inequality. Addressing these challenges requires not only economic restructuring but also the design of a sustainability-oriented agenda explicitly aligned with inclusive growth and environmental stewardship.

Policy responses should prioritize three complementary dimensions:

- Diversification of the productive base. Promoting sectors with potential in sustainable agriculture, renewable energy, advanced manufacturing, and knowledge-based services can reduce extractive dependence and support low-carbon, resilient development pathways.

- Strengthening intersectoral linkages. Expanding local value chains, intermediate technologies, and regional innovation networks is essential to foster synergies across sectors and enhance sustainability. This recommendation is consistent with the literature on regional innovation systems [68] and cluster-based development [69], which emphasize the role of institutional collaboration and innovation-driven linkages in building resilience. Comparative studies in Latin America further confirm that policies based on local clusters and innovation networks can mitigate extractive dependence and enhance productive diversification [57].

- Institutional capacity building. Establishing governance structures that integrate universities, firms, governments, and civil society is critical to co-design territorial development strategies explicitly aligned with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Evidence shows that institutional strength and coordination capacity are decisive factors for achieving resilience in resource-dependent regions [58].

Together, these measures are necessary to reduce structural vulnerability, consolidate resilience, and guide Atacama toward a sustainable, diversified, and knowledge-based development trajectory. In the short term, diversification policies should prioritize sectors with immediate potential to generate employment, while in the long term they must consolidate knowledge-based capacities and institutional resilience. This dual perspective ensures coherence between urgent needs and sustainable strategies, while embedding regional development within the broader international agenda for inclusive and sustainable growth.

5.4. Final Reflections

Advancing toward a sustainable, resilient, and equitable development model in Atacama requires policies grounded in endogenous growth theory and knowledge-based strategies. The literature on innovation systems emphasizes the role of regional learning processes and the accumulation of knowledge as key drivers of structural transformation [70]. Moreover, recent contributions on the rebirth of industrial policy underscore the importance of proactive state interventions to overcome enclave dynamics, foster productive diversification, and align industrial transformation with broader societal goals such as sustainability and resilience [71].

The methodological contribution lies in the integration of structural indicators into a synthetic framework, particularly through the use of the heatmap. This approach enhances the robustness of the empirical findings and provides policymakers with a clear and dynamic tool for diagnosing structural vulnerabilities. By making explicit the risks of extractive dependence, the study supports the design of sustainability-oriented strategies aimed at building resilience, promoting diversification, and consolidating development pathways aligned with both national priorities and global sustainability agendas [72].

5.5. Originality and Value of the Study

This article introduces, for the first time, the application of an integrated Theil–Entropy–HHI framework to the Atacama Region over a two-decade horizon, complemented by a synthetic heatmap that provides a dynamic visualization tool for policy design.

The originality of this study lies in the application of three structural indicators (Theil, E*, and HHI) within an integrated and longitudinal framework. Unlike static approaches, it provides a dynamic and multidimensional perspective of specialization and concentration, capturing structural trajectories over time [73]. Moreover, there is a notable scarcity of empirical research focusing specifically on Chilean regions; most existing studies address national aggregates or isolated case studies. By applying a comprehensive indicator-based framework at the regional scale, this study fills a significant gap in the literature, making a distinctive contribution to the analysis of structural concentration and diversification in Chile.

The results carry direct policy relevance for regional planning in Chile and other resource-dependent economies, offering an evidence-based foundation to design sustainability-oriented policies, foster knowledge-based strategies, and guide diversification efforts. By explicitly linking its findings to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the study contributes to academic debates on structural concentration and economic specialization while also delivering practical insights for building resilient, inclusive, and sustainable development pathways in extractive-based regions worldwide [74].

Finally, it is important to underline the originality of this contribution. Empirical studies that apply structural indicators at the regional level in Chile are extremely scarce, as most analyses focus on national aggregates or single-case approaches. By implementing an integrated Theil–Entropy–HHI framework for the Atacama Region over two decades, this study fills a critical gap in the literature and provides one of the few systematic assessments of regional structural concentration in Chile. This reinforces its distinct value for both academic debates and policy design.

In sum, the study not only makes an original contribution by applying a rarely used set of structural indicators to a Chilean region, but also provides practical insights for policy transfer. The evidence shows that Atacama can adapt lessons from both more concentrated economies, such as Antofagasta, and more diversified ones, such as Coquimbo, to strengthen intersectoral linkages and reduce vulnerability to external shocks. By bridging methodological innovation with actionable policy recommendations, this work delivers a unique contribution to both the academic debate on regional specialization and the practical design of diversification and resilience strategies in resource-dependent economies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.F. and M.D.; methodology, H.F. and G.M. software, H.F.; validation, H.F., M.D. and G.M. formal analysis, H.F.; investigation, H.F. and M.D.; resources, H.F.; data curation, H.F.; writing—original draft preparation, H.F.; writing—review and editing, H.F., M.D. and G.M. visualization, H.F. and G.M. supervision, H.F.; project administration, H.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are publicly available from the Central Bank of Chile (Banco Central de Chile) at: https://si3.bcentral.cl/estadisticas (accessed on 5 October 2025). Processed data and Python scripts used for calculations are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support of the Department of Industry and Business, Faculty of Engineering, University of Atacama, for providing administrative and academic resources that facilitated this research. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT (OpenAI, GPT-5, 2025) exclusively for purposes of improving English readability and translating from Spanish to English. The authors have carefully reviewed and edited the outputs and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Vezzoli, M.; Valtorta, R.R.; Gáspár, A.; Cervone, C.; Durante, F.; Maass, A.; Suitner, C. Why are some countries rich and others poor? Development and validation of the attributions for Cross-Country Inequality Scale (ACIS). PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0298222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lessmann, C.; Steinkraus, A. The Geography of Natural Resources, Ethnic Inequality and Development. SSRN Electron. J. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, S.; Segal, P. Chapter 11 The Global Distribution of Income. In Handbook of Income Disribution; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; Volume 2, pp. 937–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perroux, F. Economic Space: Theory and Applications. Q. J. Econ. 1950, 64, 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, H.; Read, R. Geographical ‘handicaps’ and small states: Some implications for the Pacific from a global perspective. Asia Pac. Viewp. 2006, 47, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svampa, M. Neo-Extractivism in Latin America: Socio-Environmental Conflicts, the Territorial Turn, and New Political Narratives; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Pose, A. The revenge of the places that don’t matter (and what to do about it). Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 2018, 11, 189–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capello, R. Regional Economics, 2nd ed.; Taylor & Francis Group: Abingdon, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crescenzi, R.; Rodríguez-Pose, A. Innovation and Regional Growth in the European Union; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez, J.F.C. Higher education, regional growth and cohesion: Insights from the Spanish case. Reg. Stud. 2021, 55, 1403–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiglitz, J.E.; Sen, A.; Fitoussi, J.-P. Report by the Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress; Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress: Paris, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Krugman, P. Increasing Returns and Economic Geography. J. Political Econ. 1991, 99, 483–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A. An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, 5th ed.; Strahan & Cadell: London, UK, 1776; reprint 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ricardo, D. On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation; John Murray: London, UK, 1817; reprint Econlib, 3rd ed., 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hausmann, R.; Hwang, J.; Rodrik, D. What You Export Matters Ricardo. J. Econ. Growth 2007, 12, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PBalland, P.-A.; Boschma, R.; Crespo, J.; Rigby, D.L. Smart specialization policy in the European Union: Relatedness, knowledge complexity and regional diversification. Reg. Stud. 2019, 53, 1252–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghion, P.; Howitt, P. A Model of Growth Through Creative Destruction. Econometrica 1992, 60, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, R.E. On the mechanics of economic development. J. Monet. Econ. 1988, 22, 3–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foray, D. The Economic of Knowledge; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lundvall, B.Å. National Systems of Innovation; Anthem Press: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asheim, B.T.; Gertler, M.S. The Geography of Innovation: Regional Innovation Systems. In The Oxford Handbook of Innovation; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2009; pp. 290–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, H.F.; Campillay, M.D. Analysis Of Economic Specialization in the Atacama Region, Chile. Migr. Lett. 2024, 21, 1039–1048. Available online: https://migrationletters.com/index.php/ml/article/view/7811 (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- Nations United. Transforming our world: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. In Sustainable Development Goals; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Torres, R.M. Desigualdad del ingreso en Colombia: Un estudio por departamentos. Cuad. Econ. 2017, 36, 139–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crescenzi, R.; Luca, D.; Milio, S. The geography of the economic crisis in Europe: National macroeconomic conditions, regional structural factors and short-term economic performance. Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 2016, 9, 13–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roszkowska, E.; Wachowicz, T. Impact of Normalization on Entropy-Based Weights in Hellwig’s Method: A Case Study on Evaluating Sustainable Development in the Education Area. Entropy 2024, 26, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R.; Sunley, P. On the notion of regional economic resilience: Conceptualization and explanation. J. Econ. Geogr. 2015, 15, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chile. Ley N.º 20.174, Crea la XIV Región de Los Ríos y la Provincia de Ranco en su Territorio, Diario Oficial de la República de Chile, Santiago, 5-Apr-2007. Available online: https://bcn.cl/25g4x (accessed on 13 April 2025).

- Chile. Ley N.º 20.175, Crea la XV Región de Arica y Parinacota y la Provincia del Tamarugal en la Región de Tarapacá, Diario Oficial de la República de Chile, Santiago, 11-Apr-2007. Available online: https://www.bcn.cl/leychile/navegar?idNorma=259864 (accessed on 13 April 2025).

- Chile. Ley N.º 21.033, Crea la XVI Región de Ñuble y las Provincias de Diguillín, Punilla e Itata, Diario Oficial de la República de Chile, Santiago, 5-Sep-2017. Available online: https://www.bcn.cl/leychile/navegar?idNorma=1107597 (accessed on 13 April 2025).

- Conceição, P.; Ferreira, P. The Young Person’s Guide to the Theil Index: Suggesting Intuitive Interpretations and Exploring Analytical Applications; UTIP Working Paper No. 14; University of Texas Inequality Project: Austin, TX, USA, 2000. Available online: https://utip.gov.utexas.edu/papers/utip_14.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2025). [CrossRef]

- Frenken, K.; Van Oort, F.; Verburg, T. Related Variety, Unrelated Variety and Regional Economic Growth. Reg. Stud. 2007, 41, 685–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Biase, G.; D’Amico, G. Generalized Concentration/Inequality Indices of Economic Systems Evolving in Time. WSEAS Trans. Math. 2010, 9, 140–149. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/232041446 (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- Shannon, C.E. A Mathematical Theory of Communication. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 1948, 27, 623–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhoades, S. The Herfindahl-Hirschman Index. Fed. Reserve Bull. 1993, 79, 188–189. [Google Scholar]

- Hinloopen, J.; Van Marrewijk, C. On the Empirical Distribution of the Balassa Index. Weltwirtsch. Arch. 2001, 137, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lessmann, C. Spatial inequality and development–Is there an inverted-U relationship? J. Dev. Econ. 2014, 106, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, H. National Power and the Structure of Foreign Trade; University of California Press: Oakland, CA, USA, 2018; reprint. [Google Scholar]

- Theil, H. Economics and Information Theory; North-Holland Publishing Company: Amsterdam, The Netherland, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- De la Fuente, Á. Series Enlazadas de Empleo y VAB para España, 1955–2014. Estad. Española 2016, 58, 5–41. [Google Scholar]

- Márquez, M.A. Diversificación de la estructura exportadora de la Comunidad Andina: Análisis a través del índice Herfindahl-Hirschmann. Economía 2016, 41–42, 77–104. Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/a/ula/econom/v41y2016i42p77-104.html (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- System of National Accounts 2008; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2009.

- OECD. OECD Regional Outlook 2021; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banco Central de Chile. Cuentas Nacionales de Chile Producto Interno Bruto Regional: Métodos y Fuentes de Información; Banco Central de Chile: Santiago, Chile, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, B.H.; Moore, C.L. A Critical Review of the Literature on Shift-Share as A Forecasting Technique. J. Reg. Sci. 1980, 20, 419–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun-Yun, S.; Yang, Y. A Review of Shift-Share Analysis and Its Application in Tourism. Int. J. Manag. 2008, 1, 21–30. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Wei, Y.D.; Li, Q.; Yuan, F. Economic Transition and Changing Location of Manufacturing Industry in China: A Study of the Yangtze River Delta. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, R.; Rhee, Z.; Bae, S.-J.; Lee, S.-H. Analysis of Industrial Diversification Level of Economic Development in Rural Areas Using Herfindahl Index and Two-Step Clustering. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šťastná, S.; Ženka, J.; Krtička, L. Regional economic resilience: Insights from five crises. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2024, 32, 506–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. OECD Regions and Cities at a Glance 2024; OECD Regions and Cities at a Glance; OECD: Paris, France, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bebbington, A.; Hinojosa, L.; Bebbington, D.H.; Burneo, M.L.; Warnaars, X. Contention and Ambiguity: Mining and the Possibilities of Development. Dev. Chang. 2008, 39, 887–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezcurra, R.; Gil, C.; Pascual, P.; Rapún, M. Regional inequality in the European Union: Does industry mix matter? Reg. Stud. 2010, 39, 679–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, F.; Hon, C.T.; Mao, Y.H.; Lai, I.K.W. Sustainable Development for Small Economy and Diversification from a Dominant Industry: Evidence from Macao. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herfindahl, O. Concentration in the U.S. Steel Industry. Ph.D. Dissertation, Columbia University, New York, NY, USA, 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Brülhart, M.; Traeger, R. An account of geographic concentration patterns in Europe. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 2005, 35, 597–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowell, F.A. Measuring Inequality, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011; ISBN 9780199594039. [Google Scholar]

- CEPAL. Horizontes 2030: La Igualdad en el Centro del Desarrollo Sostenible; Naciones Unidas, Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe (CEPAL): Santiago, Chile, 2016; Available online: https://repositorio.cepal.org/handle/11362/40117 (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Atkinson, A.B. Inequality: What Can Be Done? Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-0-674-50476-9. [Google Scholar]

- Auty, R.M. The Political Economy of Resource-Driven Growth. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2001, 45, 839–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudynas, E. Extractivisms: Tendencies and Consequences; Centro Latino Americano de Ecología Social (CLAES): Montevideo, Uruguay, 2018; Available online: https://gudynas.com/wp-content/uploads/GudynasExtractivismsTendenciesConsquences18.pdf (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- MEF–Ministerio de Economía y Finanzas. Informe Anual 2020 del Fondo de Estabilización Fiscal. Lima, Perú. 2020. Available online: https://www.mef.gob.pe/contenidos/tesoro_pub/fef/informe_anual2020_FEF.pdf (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- Kalmanovitz, S.; López, E. Análisis histórico de la minería y encadenamientos productivos en Colombia. In Salomón Kalmanovitz: Semblanza de un Pensador Caribe; Perdomo, J.A., Florián, D.D., Corrales, J.P., Eds.; Editorial Universidad del Norte: Barranquilla, Colombia, 2019; pp. 135–186. Available online: https://manglar.uninorte.edu.co/handle/10584/8390 (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- Auty, R.M. Resource Abundance and Economic Development; UNU/WIDER: Helsinki, Finland, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- John, T.; Hans, L. Innovation, Productivity Growth, and the Survival of the U.S. Copper Industry; RFF Working Paper Series dp-97-41, Re-sources for the Future. 1997. Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/p/rff/dpaper/dp-97-41.html (accessed on 17 May 2025).

- Barbier, E.B.; Burgess, J.C. Sustainable development goal indicators: Analyzing trade-offs and complementarities. World Dev. 2019, 122, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNCTAD. Productive Capacities Index: Methodological Guide; United Nations Conference on Trade and Development: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; Available online: https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/aldc2020d3_en.pdf (accessed on 9 May 2025).

- Independent Group of Scientists. Global Sustainable Development Report 2019: The Future is Now–Science for Achieving Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2019; Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/sites/default/files/2020-07/24797GSDR_report_2019.pdf (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Cooke, P. Regional Innovation Systems, Clusters, and the Knowledge Economy. Ind. Corp. Change 2001, 10, 945–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E. The Competitive Advantage of Nations; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990; Available online: https://economie.ens.psl.eu/IMG/pdf/porter_1990_-_the_competitive_advantage_of_nations.pdf (accessed on 17 May 2025).

- Lundvall, B.-Å. The Learning Economy and the Economics of Hope; Anthem Press: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Aiginger, K.; Rodrik, D. Rebirth of Industrial Policy; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Duran, H.; Fratesi, U. Economic Resilience and Regionally Differentiated Cycles: Evidence from a Turning Point Approach in Italy. Pap. Reg. Sci. 2023, 102, 219–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boschma, R. Relatedness as driver behind regional diversification: A research agenda. In Papers in Evolutionary Economic Geography (PEEG); no. 17.02; Utrecht University: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Barca, F.; McCann, P.; Rodríguez, A. The Case for Regional Development Intervention: Place-Based Versus Place-Neutral Approaches. J. Reg. Sci. 2012, 52, 134–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).