Enterprise Openness and Open Innovation Performance: The Dual Mediation of Knowledge Management Capability and Organizational Learning

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Hypothesis Development

2.1. Openness and Open Innovation Performance

2.2. The Mediating Effect of Knowledge Management Capability

2.3. The Mediating Effect of Organizational Learning

- (1)

- The mediating effect of explorative learning

- (2)

- The mediating effect of exploitative learning

2.4. The Serial Mediation of Knowledge Management Capability and Organizational Learning

3. Methods

3.1. Data and Sampling

3.2. Measurement

4. Empirical Analysis

4.1. Correlation Analysis

4.2. Reliability and Validity Test

4.3. Hypothesis Test

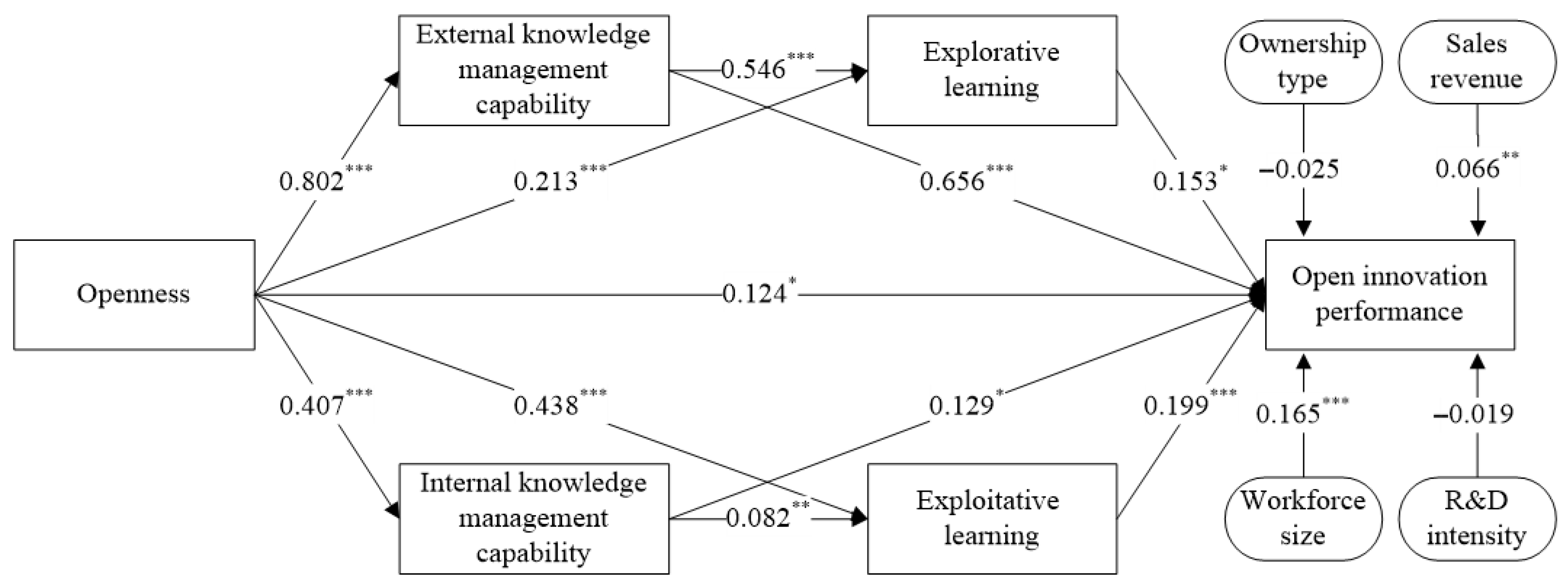

4.3.1. Structural Equation Modeling Analysis

4.3.2. Mediating Effect Test

4.4. Robustness Test

5. Discussion

5.1. Main Findings and Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Research Limitations and Prospects

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Items (Strongly Disagree/1-Strongly Agree/7) |

|---|

| Openness |

| The firm fosters an organizational culture conducive to partnering with external entities. |

| The company is willing to share experiences via collaborative efforts. |

| Senior managers at the company take an initiative-oriented approach to cooperation with external entities. |

| By and large, the company places trust in external collaborators. |

| External knowledge management capability |

| We are capable of identifying and leveraging relevant knowledge from outside networks. |

| We often analyze external knowledge. |

| We are able to integrate internal knowledge with external knowledge. |

| We are able to apply new knowledge to a specific application quickly. |

| The number of affiliates in our partnership network is considerable. |

| We have a close relationship with the affiliates in our partnership network. |

| We are able to identify knowledge that is transferred from us to external network. |

| The process of knowledge transfer from our company to external network is well organized. |

| We provide adequate support for the process of knowledge transfer to external network. |

| Internal knowledge management capability |

| Among all knowledge sources, our internal knowledge makes a major contribution. |

| Our internal team provides major knowledge. |

| Our new employees provide major knowledge. |

| We are capable of preserving the knowledge gained from external channels. |

| We are able to integrate existing knowledge with new knowledge. |

| We exhibit the capability to maintain the technology acquired from external origins. |

| We have the ability to expand our product range. |

| The percentage of our new product sales revenue is growing fast. |

| We have valuable knowledge in innovative manufacturing and technology processes. |

| Explorative learning |

| Project team members systematically sought out new possibilities in the course of the work. |

| Members of the team presented innovative ideas and problem-solving approaches for intricate issues. |

| Members of the team tested innovative and original methods for carrying out work tasks. |

| The team assessed multiple options pertaining to the project’s development path. |

| Our team members cultivated numerous new competencies in the project. |

| Exploitative learning |

| The team combined existing knowledge resources to execute work processes. |

| Routine activities constituted the primary work of our team. |

| The team applied standardized approaches as the project progressed. |

| During the project lifecycle, team members polished the specialized skills. |

| In executing their tasks, the team primarily employed their existing professional competencies. |

| Open innovation performance |

| We have rolled out some new products over the last three years. |

| We have accelerated the development of new products over the preceding three years. |

| We have a high success rate of innovation projects in the last three years. |

| We apply for some patents in the last three years. |

| The proportion of new product sales revenue in our total sales has been high in the last three years. |

References

- Zhang, X.; Chu, Z.; Ren, L.; Xing, J. Open Innovation and Sustainable Competitive Advantage: The Role of Organizational Learning. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2023, 186, 122114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigliardi, B.; Ferraro, G.; Filippelli, S.; Galati, F. The Past, Present and Future of Open Innovation. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2021, 24, 1130–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madrid-Guijarro, A.; Martin, D.P.; García-Pérez-De-Lema, D. Capacity of Open Innovation Activities in Fostering Product and Process Innovation in Manufacturing SMEs. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2021, 15, 2137–2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhao, S.; Fan, X.; Zhang, B.; Shao, D. The Impact of Open Innovation on Innovation Performance: The Chain Mediating Effect of Knowledge Field Activity and Knowledge Transfer. Inf. Technol. Manag. 2025, 26, 139–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laursen, K.; Salter, A. Open for Innovation: The Role of Openness in Explaining Innovation Performance among Uk Manufacturing Firms. Strateg. Manag. J. 2006, 27, 131–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.T.; Bagherzadeh, M.; Markovic, S.; Damnjanovic, V. Open Innovation Where It Really Matters: The U-Shaped Relationship between Relative Open Innovation and Innovation Performance in Developing Countries. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2024, 71, 15540–15554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Ma, Z.; Liang, X.; Garrett, T.C. Antecedents and Outcomes of Open Innovation over the Past 20 Years: A Framework and Meta-Analysis. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2024, 41, 793–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capone, F.; Innocenti, N.; Baldetti, F.; Zampi, V. Firm’s Openness and Innovation in Industry 4.0. Compet. Rev. 2023, 34, 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumanti, A.A.; Rizana, A.F.; Ramadhan, F.; Reynaldo, R. The Impact of Open Innovation Preparation on Or-ganizational Performance: A Systematic Literature Review. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 126952–126966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.W.; Zhou, Y. Innovation Network, Knowledge Absorption Ability, and Technology Innovation Performance—An Empirical Analysis of China’s Intelligent Manufacturing Industry. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, 0293429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, S.C.; Zo, H. Do R&D Resources Affect Open Innovation Strategies in SMEs: The Mediating Effect of R&D Openness on the Relationship between R&D Resources and Firm Performance in South Korea’s Innovation Clusters. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2023, 35, 1385–1397. [Google Scholar]

- Tikas, G. Toward Measuring R&D Knowledge Management Capability: Scale Development and Empirical Validation. Vine. J. Inf. Knowl. Manag. Syst. 2024, ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal, S.; Rasheed, M.; Khan, H.; Siddiqi, A. Human Resource Practices and Organizational Innovation Capability: Role of Knowledge Management. Vine J. Inf. Knowl. Manag. Syst. 2021, 51, 732–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, P.B.; Le, H.M. Stimulating Exploitative and Exploratory Innovation through Transformational Leadership and Knowledge Management Capability: The Moderating Role of Competitive Intensity. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2023, 44, 1037–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelaty, H.; Weiss, D. Coping with the Heterogeneity of External Knowledge Sources: Corresponding Openness Strategies and Innovation Performance. J. Innov. Knowl. 2023, 8, 100423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harsono, T.W.; Hidayat, K.; Iqbal, M.; Abdillah, Y. Exploring the Effect of Transformational Leadership and Knowledge Management in Enhancing Innovative Performance: A Mediating Role of Innovation Capability. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2025, 36, 227–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhang, K. The Impact of Knowledge Management Capabilities on Innovation Performance from Dynamic Capabilities Perspective: Moderating the Role of Environmental Dynamism. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Yu, H.; Zhang, L.; Wu, Z.; Ju, X. How Does Enterprise Social Network Affects Open Innovation Performance? From the Dual Perspective of Inter- and Intra-Organisation. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2023, 35, 1191–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migdadi, M.M. Organizational Learning Capability, Innovation and Organizational Performance. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2021, 24, 151–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.F.; Li, P.S.; Li, Y. The Relationship between Slack Resources and Organizational Resilience: The Moderating Role of Dual Learning. Heliyon 2023, 9, e14044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mai, N.K.; Do, T.T.; Ho Nguyen, D.T. The Impact of Leadership Competences, Organizational Learning and Organizational Innovation on Business Performance. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2022, 28, 1391–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, F.; Lim, H.; Song, J. The Influence of Leadership Style in China SMES on Enterprise Innovation Performance: The Mediating Roles of Organizational Learning. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Dogbe, C.S.K.; Pomegbe, W.W.K.; Sarsah, S.A.; Otoo, C.O.A. Organizational Learning Ambidexterity and Openness, as Determinants of SMEs’ Innovation Performance. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2021, 24, 414–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauter, R.; Globocnik, D.; Perl-Vorbach, E.; Baumgartner, R.J. Open Innovation and Its Effects on Economic and Sustainability Innovation Performance. J. Innov. Knowl. 2019, 4, 226–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Chen, R.; Yang, X.; Hou, J. How Does the Innovation Openness of China’s Sci-Tech Innovation Enterprises Support Innovation Quality: The Mediation Role of Structural Embeddedness. Mathematics 2024, 12, 3034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Han, Z.a.; Zhou, Y. Optimal Degree of Openness in Open Innovation: A Perspective from Knowledge Acquisition & Knowledge Leakage. Technol. Soc. 2021, 67, 101756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.H.; Chin, T.; Lin, J.H. Openness and Firm Innovation Performance: The Moderating Effect of Ambidextrous Knowledge Search Strategy. J. Knowl. Manag. 2020, 24, 301–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Yu, B.; Zhang, J.; Xu, D. Effects of Open Innovation Strategies on Innovation Performance of SMEs: Evidence from China. Chinese Manag. Stud. 2021, 15, 24–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tippakoon, P.; Sang-Arun, N.; Vishuphong, P. External Knowledge Sourcing, Knowledge Management Capacity and Firms’ Innovation Performance: Evidence from Manufacturing Firms in Thailand. J. Asia Bus. Stud. 2021, 17, 149–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, J.; Qi, Y. Fostering Knowledge Creation through Network Capability Ambidexterity with the Moderation of an Innovation Climate. J. Knowl. Manag. 2023, 27, 613–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.M.; Mortara, L.; Minshall, T. Dynamic Capabilities and Economic Crises: Has Openness Enhanced a Firm’s Performance in an Economic Downturn? Ind. Corp. Chang. 2018, 27, 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J. Unleashing the Dynamics of Triple-a Capabilities: A Dynamic Ambidexterity View. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2021, 121, 2595–2613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Guo, J.e.; Chen, T.; Murong, R. Configuration Research on Innovation Performance of Digital Enterprises: Based on an Open Innovation and Knowledge Perspective. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 10, 953902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongmahesak, K.; Wongsuwan, N.; Akkaya, B.; Palazzo, M. Impact of Knowledge Management Process on Organizational Performance: The Mediating Role of Technological Innovation. Knowl. Process Manag. 2025, 32, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.T.; Yu, D.K. Exploring the Impact of Knowledge Management Capability on Firm Performance: The Mediating Role of Business Model Innovation. Kybernetes 2024, 53, 3591–3620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenthaler, U.; Lichtenthaler, E. A Capability-Based Framework for Open Innovation: Complementing Absorptive Capacity. J. Manag. Stud. 2009, 46, 1315–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X. Moderating Effect of Structural Holes on Absorptive Capacity and Knowledge-Innovation Performance: Empirical Evidence from Chinese Firms. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, R.; Krenz, A.; Moffat, J. The Effects of Absorptive Capacity on Innovation Performance: A Cross-Country Perspective*. JCMS-J. Common. Mark. Stud. 2021, 59, 589–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, T.; Geng, Q.; Zhao, Q. Understanding the Efforts of Cross-Border Search and Knowledge Co-Creation on Manufacturing Enterprises’ Service Innovation Performance. Systems 2023, 11, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.-C.; Lin, B.-W.; Chen, C.-J. How Do Internal Openness and External Openness Affect Innovation Capabilities and Firm Performance? IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2013, 60, 704–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, N. Knowledge Management Capability and Outbound Open Innovation: Unpacking the Role of Desorptive Capacity. Knowl. Process Manag. 2023, 30, 317–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braojos, J.; Benitez, J.; Llorens, J.; Ruiz, L. Impact of It Integration on the Firm’s Knowledge Absorption and Desorption. Inf. Manag. 2020, 57, 103290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashosi, G.D.; Wu, Y.; Getele, G.K.; Bianca, E.M.; Irakoze, E. The Role of Absorptive Capacity and Firm Openness Strategies on Innovation Performance. Inf. Resour. Manag. J. 2020, 33, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medase, S.K.; Abdul-Basit, S. External Knowledge Modes and Firm-Level Innovation Performance: Empirical Evidence from Sub-Saharan Africa. J. Innov. Knowl. 2020, 5, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGahan, A.M.; Bogers, M.L.A.M.; Chesbrough, H.; Holgersson, M. Tackling Societal Challenges with Open Innovation. California Manag. Rev. 2021, 63, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J. Knowledge Management Capability and Technology Uncertainty: Driving Factors of Dual Innovation. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2021, 33, 783–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Sarfraz, M.; Khawaja, K.F.; Shaheen, H.; Mariam, S. The Influence of Knowledge Management Capacities on Pharmaceutical Firms Competitive Advantage: The Mediating Role of Supply Chain Agility and Moderating Role of Inter Functional Integration. Front. Public. Health 2022, 10, 953478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, K.; Kim, E.; Jeong, E. Structural Relationship and Influence between Open Innovation Capacities and Performances. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Gao, H. How Internal It Capability Affects Open Innovation Performance: From Dynamic Capability Perspective. Sage Open 2022, 12, 21582440211069389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khraishi, A.; Paulraj, A.; Huq, F.; Seepana, C. Knowledge Management in Offshoring Innovation by SMEs: Role of Internal Knowledge Creation Capability, Absorptive Capacity and Formal Knowledge-Sharing Routines. Supply Chain. Manag. Int. J. 2023, 28, 405–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Nuaimi, F.M.S.; Singh, S.K.; Ahmad, S.Z. Open Innovation in SMEs: A Dynamic Capabilities Perspective. J. Knowl. Manag. 2024, 28, 484–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patwary, A.K.; Alwi, M.K.; Rchman, S.U.; Rabiul, M.K.; Babatunde, A.Y.; Alam, M.M.D. Knowledge Management Practices on Innovation Performance in the Hotel Industry: Mediated by Organizational Learning and Organizational Crea-tivity. Global Knowl. Mem. Commun. 2024, 73, 662–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceptureanu, S.I.; Ceptureanu, E.G. Learning Ambidexterity and Innovation in Creative Industries. The Role of Enabling Formalisation. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2024, 36, 3385–3399. [Google Scholar]

- March, J.G. Exploration and Exploitation in Organizational Learning. Organ. Sci. 1991, 2, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.Q.; Qiang, Q.; Huang, L.; Huang, C.Q. How Knowledge Sharing Affects Business Model Innovation: An Empirical Study from the Perspective of Ambidextrous Organizational Learning. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.Y.; Shen, Y.L. Learning Ambidexterity and Technology Innovation: The Moderating Effect of Knowledge Network Modularity. J. Eng. Technol. Manag. 2024, 72, 101812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öberg, C.; Alexander, A.T. The Openness of Open Innovation in Ecosystems–Integrating Innovation and Management Literature on Knowledge Linkages. J. Innov. Knowl. 2019, 4, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Seo, E.-H.; Kim, C.Y. The Relationships between Environmental Dynamism, Absorptive Capacity, Organizational Ambidexterity, and Innovation Performance from the Dynamic Capabilities Perspective. Sustainability 2025, 17, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Xiong, H.; Wang, Q.; Gu, Y. The Impact of Enterprise Niche on Dual Innovation Performance: Moderating Role of Innovation Openness. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2023, 26, 1547–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Xu, M. Examining the Linkage among Open Innovation, Customer Knowledge Management and Radical Innovation: The Multiple Mediating Effects of Organizational Learning Ability. Balt. J. Manag. 2018, 29, 417–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirza, S.; Mahmood, A.; Waqar, H. The Interplay of Open Innovation and Strategic Innovation: Unpacking the Role of Organizational Learning Ability and Absorptive Capacity. Int. J. Eng. Bus. Manag. 2022, 14, 18479790211069745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginja Antunes, H.d.J.; Pinheiro, P.G. Linking Knowledge Management, Organizational Learning and Memory. J. Innov. Knowl. 2020, 5, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sancho-Zamora, R.; Hernandez-Perlines, F.; Pena-Garcia, I.; Gutierrez-Broncano, S. The Impact of Absorptive Capacity on Innovation: The Mediating Role of Organizational Learning. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19, 842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, M.K.; Fatima, T.; Sarwar, A.; Amin, S. Knowledge Management Capabilities and Organizational Outcomes: Contemporary Literature and Future Directions. Kybernetes 2022, 51, 2814–2832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; Mackenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, J.M.; Ju, Y.; Moon, T.H.; Minshall, T.; Probert, D.; Sohn, S.Y.; Mortara, L. Beyond Absorptive Capacity in Open Innovation Process: The Relationships between Openness, Capacities and Firm Performance. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2016, 28, 1009–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forés, B.; Camisón, C. Does Incremental and Radical Innovation Performance Depend on Different Types of Knowledge Accumulation Capabilities and Organizational Size? J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 831–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudambi, S.M.; Tallman, S. Make, Buy or Ally? Theoretical Perspectives on Knowledge Process Outsourcing through Alliances. J. Manag. Stud. 2010, 47, 1434–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.-C.; Lai, M.-C.; Huang, W.-W. Resource Complementarity, Transformative Capacity, and Inbound Open Innovation. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2015, 30, 842–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Zong, B.; Zhang, L. Explorative and Exploitative Learning in Teams: Unpacking the Antecedents and Consequences. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Chen, J.; Liang, L. How Open Innovation Performance Responds to Partner Heterogeneity in China. Manag. Decis. 2018, 56, 26–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davino, C.; Romano, R.; Vistocco, D. Handling multicollinearity in quantile regression through the use of principal component regression. Metron 2022, 80, 153–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golafshani, N. Understanding Reliability and Validity in Qualitative Research. Qual. Rep. 2003, 8, 597–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis. A Global Perspective, 7th ed.; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B.; Rau, P.L.P.; Yuan, T. Measuring user competence in using artificial intelligence: Validity and reliability of artificial intelligence literacy scale. Behav. Inform. Technol. 2023, 42, 1324–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B.; Little, T.D. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Srouji, A.F.; Hamdallah, M.E.; Al-Hamadeen, R.; Al-Okaily, M.; Elamer, A.A. The impact of green innovation on sustainability and financial performance: Evidence from the Jordanian financial sector. Bus. Strategy Dev. 2023, 6, 1037–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, D.W.M.; Sarvari, H.; Golestanizadeh, M.; Saka, A. Evaluating the Impact of Organizational Learning on Organizational Performance through Organizational Innovation as a Mediating Variable: Evidence from Iranian Construction Companies. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2024, 24, 921–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuks, O. It Capability, Organisational Learning and Innovation Performance of Firms in Kenya. J. Knowl. Econ. 2023, 14, 3489–3517. [Google Scholar]

- Rawashdeh, A.M.; Almasarweh, M.S.; Alhyasat, E.B.; Rawashdeh, O.M. The Relationsip between the Quality Knowledge Management and Organizational Performance Via the Mediating Role of Organizational Learning. Int. J. Qual. Res. 2021, 15, 373–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Number | Percent (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ownership type | State-owned | 316 | 42.5 |

| Private-owned | 247 | 33.2 | |

| Joint Ventures | 128 | 17.2 | |

| Foreign-owned | 53 | 7.1 | |

| Sales revenue (CNY) | <5,000,000 | 48 | 6.5 |

| 5,000,000–50,000,000 | 229 | 30.8 | |

| 50,000,000–300,000,000 | 373 | 50.1 | |

| >300,000,000 | 94 | 12.6 | |

| Workforce size | <50 | 78 | 10.5 |

| 50–300(including) | 192 | 25.8 | |

| 300–1000(including) | 318 | 42.7 | |

| >1000 | 156 | 21.0 | |

| R&D intensity | <1% | 139 | 18.7 |

| 1–2%(including) | 217 | 29.2 | |

| 2–5%(including) | 296 | 39.8 | |

| >5% | 92 | 12.4 |

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Openness | 0.854 | |||||

| 2. EKMC | 0.602 *** | 0.849 | ||||

| 3. IKMC | 0.340 ** | 0.370 ** | 0.805 | |||

| 4. Explorative learning | 0.576 ** | 0.557 ** | 0.282 * | 0.865 | ||

| 5. Exploitative learning | 0.466 ** | 0.531 ** | 0.206 * | 0.546 ** | 0.884 | |

| 6. OIP | 0.590 *** | 0.615 *** | 0.334 ** | 0.571 ** | 0.507 ** | 0.867 |

| Mean | 4.550 | 4.694 | 5.158 | 4.762 | 4.152 | 4.997 |

| Standard deviation | 1.300 | 1.592 | 1.312 | 1.469 | 1.609 | 1.630 |

| Variable | CR | AVE | Cronbach’s α | Factor Loading |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Openness | 0.915 | 0.730 | 0.880 | 0.761 |

| 0.827 | ||||

| 0.911 | ||||

| 0.910 | ||||

| EKMC | 0.958 | 0.720 | 0.913 | 0.852 |

| 0.826 | ||||

| 0.899 | ||||

| 0.784 | ||||

| 0.899 | ||||

| 0.761 | ||||

| 0.913 | ||||

| 0.835 | ||||

| 0.852 | ||||

| IKMC | 0.943 | 0.648 | 0.830 | 0.793 |

| 0.724 | ||||

| 0.770 | ||||

| 0.829 | ||||

| 0.834 | ||||

| 0.862 | ||||

| 0.837 | ||||

| 0.781 | ||||

| 0.806 | ||||

| Explorative learning | 0.937 | 0.749 | 0.896 | 0.865 |

| 0.879 | ||||

| 0.909 | ||||

| 0.845 | ||||

| 0.827 | ||||

| Exploitative learning | 0.947 | 0.781 | 0.879 | 0.875 |

| 0.886 | ||||

| 0.912 | ||||

| 0.905 | ||||

| 0.839 | ||||

| OIP | 0.938 | 0.751 | 0.939 | 0.866 |

| 0.908 | ||||

| 0.862 | ||||

| 0.824 | ||||

| 0.870 |

| Path | Estimate | p-Value | 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| Direct effect | Openness→OIP | 0.124 | 0.058 | 0.049 | 0.162 |

| Indirect effect | Openness→EKMC→OIP | 0.526 | 0.000 | 0.443 | 0.609 |

| Openness→IKMC→OIP | 0.053 | 0.079 | 0.026 | 0.061 | |

| Openness→Explorative learning→OIP | 0.033 | 0.086 | 0.012 | 0.067 | |

| Openness→Exploitative learning→OIP | 0.087 | 0.000 | 0.047 | 0.127 | |

| Openness→EKMC→Explorative learning→OIP | 0.067 | 0.077 | 0.005 | 0.096 | |

| Openness→IKMC→Exploitative learning→OIP | 0.007 | 0.028 | 0.001 | 0.012 | |

| Total indirect effect | - | 0.773 | 0.000 | 0.65 | 0.794 |

| Total effect | - | 0.897 | 0.000 | 0.738 | 0.915 |

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ownership type | −0.195 *** | −0.059 *** | −0.073 *** | −0.158 *** | −0.060 ** | −0.071 *** |

| Sales revenue | 0.035 | 0.103 | 0.065 *** | 0.014 | 0.022 | 0.024 |

| Workforce size | 0.265 *** | 0.191 | 0.171 *** | 0.231 *** | 0.142 *** | 0.217 *** |

| R&D intensity | 0.127 *** | 0.033 | 0.015 | 0.082 *** | 0.013 | 0.036 |

| Openness | 0.663 *** | |||||

| EKMC | 0.762 *** | |||||

| IKMC | 0.290 *** | |||||

| Explorative learning | 0.637 *** | |||||

| Exploitative learning | 0.578 *** | |||||

| R2 | 0.104 | 0.503 | 0.649 | 0.184 | 0.469 | 0.413 |

| F | 30.024 *** | 209.973 *** | 382.378 *** | 46.725 *** | 182.691 *** | 145.994 *** |

| Variables | Model 7 | Model 8 | Model 9 | Model 10 | Model 11 | Model 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ownership type | −0.058 *** | −0.053 ** | −0.022 | −0.013 | −0.037 * | −0.008 |

| Sales revenue | 0.077 *** | 0.093 *** | 0.073 *** | 0.080 *** | 0.064 *** | 0.071 *** |

| Workforce size | 0.168 *** | 0.184 *** | 0.142 *** | 0.179 *** | 0.142 *** | 0.172 *** |

| R&D intensity | 0.010 | 0.022 | −0.005 | −0.002 | −0.009 | −0.011 |

| Openness | 0.168 *** | 0.632 *** | 0.447 *** | 0.505 *** | 0.121 *** | 0.479 *** |

| EKMC | 0.635 *** | 0.532 *** | ||||

| IKMC | 0.097 *** | 0.087 *** | ||||

| Explorative learning | 0.381 *** | 0.225 *** | ||||

| Exploitative learning | 0.363 *** | 0.360 *** | ||||

| R2 | 0.659 | 0.511 | 0.591 | 0.603 | 0.686 | 0.609 |

| F | 333.610 *** | 180.612 *** | 249.581 *** | 261.593 *** | 322.299 *** | 230.153 *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yu, Z.; Zhao, K.; Yu, H. Enterprise Openness and Open Innovation Performance: The Dual Mediation of Knowledge Management Capability and Organizational Learning. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9993. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17229993

Yu Z, Zhao K, Yu H. Enterprise Openness and Open Innovation Performance: The Dual Mediation of Knowledge Management Capability and Organizational Learning. Sustainability. 2025; 17(22):9993. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17229993

Chicago/Turabian StyleYu, Zhaoyuan, Kaixin Zhao, and Haiqing Yu. 2025. "Enterprise Openness and Open Innovation Performance: The Dual Mediation of Knowledge Management Capability and Organizational Learning" Sustainability 17, no. 22: 9993. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17229993

APA StyleYu, Z., Zhao, K., & Yu, H. (2025). Enterprise Openness and Open Innovation Performance: The Dual Mediation of Knowledge Management Capability and Organizational Learning. Sustainability, 17(22), 9993. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17229993