Abstract

Ethno-tourism is increasingly recognized as a driver of rural development and cultural preservation, particularly in the Balkans, where ethno-villages represent important centers of heritage, identity, and community revitalization. Despite its significance, the systematic assessment of sustainability in ethno-tourism remains underexplored. This study addresses this gap by applying the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) to evaluate the sustainability performance of thirteen ethno-villages across Serbia, Montenegro, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Croatia. Data were collected through interviews with owners and managers, complemented by benchmarking and SWOT analyses, to develop a multi-criteria model incorporating five dimensions: economic performance, environmental sustainability, infrastructure and management, tourism attractiveness, and socio-cultural aspects. The results highlight economic performance as the most influential factor, followed by environmental sustainability and infrastructure, while tourism attractiveness and socio-cultural aspects had relatively lower importance. The ranking of villages revealed Drvengrad Mećavnik (Serbia) as the most sustainable destination, with robustness confirmed through sensitivity analyses. This study represents one of the first comprehensive, multi-criteria evaluations of ethno-village sustainability in the Balkans. The results demonstrate that long-term success depends on balancing financial viability with ecological practices, infrastructural investment, and cultural preservation. This research provides evidence-based recommendations for policymakers and stakeholders, and highlights the value of multi-criteria approaches for sustainable tourism planning.

1. Introduction

Tourism is a key driver of economic development, particularly in rural areas where alternative livelihood opportunities are often limited [,,]. Ethno-tourism, a form of cultural tourism, emphasizes authenticity and enables visitors to learn about and directly experience traditional ways of life, local customs, cuisine, and craftsmanship. It contributes to the preservation of cultural heritage, strengthens local identity, and supports the sustainable development of rural areas while simultaneously promoting economic growth [,,,,,]. Closely related is indigenous tourism, which allows visitors to experience indigenous settlements and observe daily life. Beyond its economic benefits, indigenous tourism also helps to retain younger generations within their communities, thereby reducing rural outmigration [,,]. Both ethno-tourism and indigenous tourism share core principles, including the promotion of cultural authenticity, heritage preservation, and long-term community sustainability.

Ethno-villages, as a central component of this tourism offer, provide visitors with opportunities to engage in traditional practices such as preparing local food, attending craft workshops, and participating in cultural events, including festivals and rituals. By encouraging local community involvement in tourism development, ethno-tourism contributes to economic diversification and the revitalization of rural areas []. Although ethno-tourism is practiced globally—from Maasai settlements in East Africa to Andean communities in South America and indigenous programs in North America [,,,]—its systematic sustainability assessment remains underexplored. This study, therefore, focuses on evaluating the sustainable development of ethno-villages in the Balkans.

Despite the growing significance of ethno-tourism, comprehensive and systematic assessments of its sustainability remain scarce. Previous studies have often examined only individual dimensions—such as economic, environmental, or socio-cultural impacts—without integrating them into a holistic analytical framework [,,]. Butler and Hinch [] highlighted clear gaps within the field of indigenous tourism and stressed the need for stronger theoretical and methodological foundations. Few mechanisms have been developed to quantify sustainability in this context; for example, Kunasekaran [] proposed 61 indicators for the Mah Meri ethnic group in Malaysia, yet such approaches remain exceptional. Overall, there has been no consistent attempt to develop a comprehensive model for sustainable indigenous or ethno-tourism, particularly within the Balkans.

The study aims to address the following key points: evaluating the sustainability of ethno-villages through a structured multi-criteria decision-making approach that incorporates economic, environmental, infrastructural, social, and touristic factors; assessing the relative importance of these sustainability criteria in determining the long-term viability of ethno-villages and identifying which factors exert the greatest influence on their success; and providing insights into sustainable rural tourism development by offering evidence-based recommendations for improving the balance between economic performance and sustainability in ethno-tourism. By applying the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) as a decision-making tool, this research contributes to a deeper understanding of sustainability challenges in ethno-villages. The findings aim to support policymakers and stakeholders in developing targeted strategies that enhance the resilience and sustainability of rural tourism destinations, ensuring long-term socio-economic and environmental benefits.

2. Literature Review

The sustainability of ethno-tourism refers to the long-term ability of ethno-villages to preserve natural resources, cultural heritage, and social structures while promoting economic development that benefits the local community []. While commodification can stimulate local economic development, strengthen traditions, and alleviate poverty [], scholars such as Cohen [] and Williams and Gonzalez [] caution that reducing culture to a standardized tourism product may undermine authenticity. This tension between commercialization and authenticity has become a recurring concern in the literature, with communities facing the risk of “selling out” their cultural identity [].

The key objective of sustainable ethno-tourism is to balance economic benefits with the responsible management of natural and cultural resources by involving local populations in tourism activities. It is essential to ensure that these activities do not threaten cultural authenticity or natural heritage but rather contribute to their preservation and further development [,].

The sustainability of ethno-tourism requires a long-term balance among the economic, environmental, and socio-cultural dimensions of tourism, with particular emphasis on preserving local identity and natural resources. Achieving sustainable tourism is a continuous process that requires regular monitoring and the implementation of preventive and corrective measures where necessary []. This form of tourism emphasizes the promotion and protection of unique cultural heritage, traditional customs, and the sustainable use of natural resources within local communities [,].

Measuring sustainability in ethno-tourism involves several criteria. The economic dimension includes increasing local community income, creating new jobs, and strengthening local entrepreneurship. The environmental dimension focuses on the responsible use of natural resources, reducing environmental footprints, and ensuring efficient waste management and the use of renewable energy sources []. The socio-cultural dimension involves the preservation of cultural heritage, promotion of local customs, and enhancement of the quality of life for local residents [,]. The importance of sustainability in ethno-tourism stems from its potential to promote local development and preserve cultural identity while reducing negative environmental impacts and strengthening social cohesion. Moreover, sustainable approaches in ethno-tourism enhance the visitor experience by offering authentic, culturally rich, and environmentally friendly encounters [].

Among multi-criteria decision-making methods, the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) is one of the most widely used tools for evaluating sustainability in tourism. It is particularly effective in contexts where decision-making involves multiple and often conflicting criteria, as it allows for structured comparisons and prioritization of relevant indicators [,,]. Previous studies have shown that AHP can integrate both qualitative and quantitative data, making it highly suitable for assessing the multidimensional nature of sustainability in tourism development.

Sustainable tourism rests on the balanced development of three key pillars: economic, environmental, and socio-cultural sustainability. Economic sustainability encompasses financial stability, profitability, and employment in tourism, while environmental sustainability refers to the preservation of natural resources, waste management, and mitigation of ecological impacts. Socio-cultural sustainability involves the preservation of cultural heritage, community well-being, and overall quality of life. Several studies have highlighted that an imbalance between these pillars can jeopardize the long-term stability of destinations, reinforcing the need for comprehensive approaches to sustainability assessment [,,,]. Among multi-criteria approaches, the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) remains one of the most widely applied tools, as it enables structured comparisons across multiple criteria that shape tourism development [].

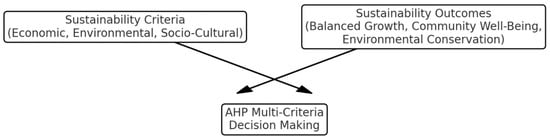

Analytical Framework

Building on the existing literature, this study develops an analytical framework that integrates five dimensions crucial to the sustainability of ethno-villages: (1) economic performance (income generation, profitability, employment opportunities); (2) environmental sustainability (resource preservation, waste management, ecological practices); (3) infrastructure and management (accessibility, accommodation capacity, service quality); (4) tourist attractiveness (uniqueness, attractions, visitor programs); and (5) socio-cultural aspects (heritage preservation, community involvement). These categories are combined within a conceptual model (Figure 1), which links the multidimensional nature of sustainability to the AHP methodology. The framework provides the foundation for assessing the relative importance of each dimension and for generating recommendations to enhance the long-term sustainability of ethno-villages.

Figure 1.

Scheme for sustainability assessment of ethno-villages using the AHP method.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Area

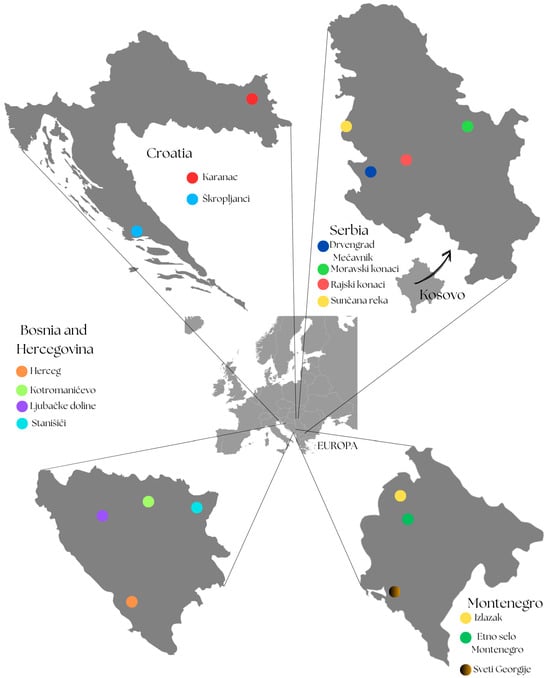

This study analyzes ethno-villages located in four countries of the former Yugoslavia—Serbia, Montenegro, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Croatia—each representing distinct geographical, cultural, and socio-economic contexts (Figure 2). These countries possess specific natural, cultural, and social characteristics that influence the development and sustainability performance of ethno-villages.

Figure 2.

Study area and spatial distribution of the analyzed ethno-villages across Croatia, Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Montenegro. Note: The boundaries and names shown on this map are for illustrative purposes only and do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the authors. This clarification specifically refers to the issue of the unilaterally declared independence of Kosovo. For internationally recognized borders, please refer to the United Nations Cartographic Section []. This representation is intended solely for academic and analytical purposes and should not be interpreted as a political statement.

In Croatia, the focus of ethno-villages lies on preserving local traditions, crafts, and gastronomy. These destinations are closely associated with traditional craftsmanship, regional cuisine, and wine culture, with strong engagement from local communities playing a vital role in maintaining authenticity and ensuring sustainable tourism development.

In Serbia, ethno-villages are typically situated in regions rich in cultural heritage and diverse landscapes, such as Mokra Gora, Šumadija, and areas along the Drina River. These sites are known for their traditional architecture and representations of historical rural life, offering activities such as culinary workshops, visits to heritage landmarks, and participation in cultural events.

In Bosnia and Herzegovina, ethno-villages have evolved into complex tourist destinations that highlight cultural and architectural heritage through religious sites, museums, and restaurants serving traditional cuisine. These villages are often located within ecologically sensitive areas containing valuable natural landmarks that require sustainable management practices.

In Montenegro, ethno-villages are located near national parks and natural landmarks, adding significant value in terms of eco-tourism potential. These areas place particular emphasis on the preservation of natural resources while also serving as venues for cultural events and traditional gatherings that promote local identity.

Although climatic conditions vary across these regions, they share common features—most notably, sensitive ecosystems that demand the sustainable management of tourism activities. All analyzed destinations face similar challenges, including the preservation of cultural heritage, the pursuit of economic development, and the protection of the environment—factors that jointly define their sustainability performance. Therefore, a multi-criteria Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) approach was applied to evaluate the sustainability of ethno-villages, allowing for a systematic assessment of the influence of individual factors. This methodology is particularly relevant in the context of the diverse regional settings examined, where local characteristics, natural resources, and cultural practices intersect, as illustrated in Figure 1.

3.2. Data Acquisition

The data collection process for developing the AHP model for assessing the sustainability of ethno-villages in Serbia, Montenegro, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Croatia was based on a multi-stage methodological approach. This approach included a preparatory study, qualitative interviews, benchmarking, SWOT analysis, and finally, the formulation of AHP criteria and their corresponding values.

The preparatory phase involved a comprehensive review of the official websites of ethno-villages and the analysis of available information regarding their tourism offerings, infrastructural characteristics, promotional practices, and service accessibility. The purpose of this phase was to formulate relevant interview questions and define key research directions to effectively address the sustainability challenges of individual ethno-villages.

The sampling of ethno-villages was designed using a combination of purposive and random sampling. In the first phase, purposive sampling was applied to ensure the inclusion of ethno-villages that met specific criteria: geographical distribution across the four Balkan countries, active engagement in tourism activities, preservation of cultural characteristics and traditions, and the availability of sufficient information for research purposes. In the second phase, simple random sampling was used to select 13 ethno-villages (Table 1), ensuring sample representativeness and enabling a comprehensive insight into various sustainability practices in the region. Although the sample size may appear modest relative to the total number of ethno-villages in the Balkans, the selected cases represent some of the most recognized and active sites in terms of tourism development and cultural preservation. The sample was purposefully chosen to ensure regional coverage and to include destinations with adequate data availability and stakeholder participation. This approach allowed for meaningful comparative analysis across diverse contexts while ensuring the methodological robustness of the AHP application.

Table 1.

Case studies of selected ethno-villages from the former Yugoslav countries.

The interviews were conducted between March and September 2024 with owners or managers of the selected ethno-villages. The organization of the interviews was adapted to the availability of the participants. Approximately half of the interviews were conducted in person on-site, while the remainder took place via online platforms (e.g., Zoom, Microsoft Teams). This flexible approach facilitated the collection of a broader range of insights and experiences while accommodating logistical constraints. The interviews lasted between 30 and 60 min, depending on the complexity of responses, participant availability, and familiarity with the topic. Before each interview, participants were informed about the purpose of the research, assured of the confidentiality of their responses, and provided their informed consent to participate.

The interview questions were developed based on the preparatory analyses and covered five key thematic areas: (1) organizational aspects and business models [,,,], focusing on the management of ethno-villages, community involvement, accessibility, and organization of the tourism offer; (2) economic aspects [,,], gathering information about income, sources of financing, profitability, and business challenges; (3) environmental aspects [,,], addressing sustainable management of natural resources, environmental protection practices, waste management, and the impact of tourism on the local environment; (4) socio-cultural aspects [,,], examining how ethno-villages contribute to cultural heritage preservation, local community involvement, and promotion of traditional practices; and (5) development challenges and opportunities [,,,], focusing on how owners and managers identify future opportunities, key barriers, and their perceptions of competitive advantage.

The questions were open-ended, enabling in-depth and diverse responses and allowing for a better understanding of the specific challenges faced by each ethno-village. In total, 19 experts participated in the evaluation process. They included ethno-village managers, local tourism officials, and academic researchers specializing in sustainable tourism and rural development. The selection of experts followed two criteria: (1) direct involvement in the management or development of ethno-villages, ensuring practical knowledge, and (2) academic or professional experience in sustainability assessment and tourism planning. This combination ensured that both practical and theoretical perspectives were represented in the decision-making process. The diversity of evaluators also reduced the risk of individual bias and enhanced the validity of the aggregated judgments used in the AHP model.

The second phase of the research involved a benchmarking analysis, in which key characteristics of individual ethno-villages were compared. The third phase included conducting a SWOT analysis for each ethno-village, identifying internal strengths and weaknesses as well as external opportunities and threats affecting their long-term sustainability. Both the SWOT and benchmarking analyses played a crucial role in shaping the final set of criteria for the AHP model. The model incorporated economic, environmental, infrastructural, tourism, and socio-cultural criteria, allowing for a comprehensive and systematic assessment of each village’s sustainability. Through this multi-stage data collection approach, a high level of result validity was achieved, enabling the formulation of well-founded recommendations for improving the sustainable development of ethno-villages in the analyzed countries.

3.3. Variable Selection and Application of AHP Methodology

The Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) is a structured decision-making approach that enables the systematic and objective evaluation of multi-criteria problems. This method allows for the integration of both quantitative and qualitative data and facilitates the determination of the relative importance of criteria for sustainability assessment. The AHP method has been successfully applied to identify and prioritize various criteria and sub-criteria contributing to sustainable tourism development in diverse contexts, such as in Wakatobi [] and Taiwan [].

Szabo [] also employed the AHP method to calculate the weights of importance in a proposed methodology with the potential to produce a new composite index for measuring, comparing, and ranking countries and regions in terms of sustainable development or its sub-criteria, as well as for tracking annual improvements and evaluating the impact of implemented policies.

Structure of the AHP Model

The Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) decomposes a decision problem into a hierarchy consisting of a goal, criteria, and alternatives, which are systematically compared in pairs using a standardized 1–9 scale to express their relative importance. By aggregating these pairwise comparisons, AHP calculates the weights of each criterion and produces a final ranking of alternatives. One of the main strengths of AHP lies in its ability to combine both qualitative judgments (expert opinions) and quantitative data, making it particularly suitable for assessing sustainability in tourism, where economic, environmental, infrastructural, and socio-cultural factors interact. The method also includes a consistency check, which ensures that expert judgments are logically coherent and reliable.

According to Stofková et al. (2022) [], the most accurate approach for calculating and establishing the appropriate order of criteria in the decision-making process is the Saaty method.

The AHP method is frequently applied in combination with SWOT analysis. Following the methodological approach proposed by Saaty and Vargas (1994) [], a three-level hierarchy was developed, comprising the following levels: (1) goal: the assessment of the sustainability of ethno-villages; (2) criteria: five key sustainability criteria identified through interviews, benchmarking, and SWOT analyses; and (3) alternatives: thirteen selected ethno-villages from four Balkan countries.

In developing the AHP model, the Super Decisions V3.2 software was used, which—along with Expert Choice—is among the most widely recognized tools for performing analyses within the AHP framework.

This approach allows a complex decision to be decomposed into simpler elements.

- Pairwise comparisons of criteria and alternatives

Saaty’s scale (from 1 to 9) was used to perform pairwise comparisons between criteria and alternatives. The evaluations were based on expert opinions obtained through interviews, complemented by the results of benchmarking and SWOT analyses.

- Calculation of weights and evaluation of alternatives

The value function for each alternative (V(x)) was calculated using the following formula:

where Wi represents the weight of each criterion, and Xi represents the evaluation of each alternative according to the i-th criterion (Table 2). Alternative x was evaluated as more desirable than alternative y when the following condition was met:

V(x) = W1X1 + W2X2 + … + WnXn

V(x) > V(y)

Table 2.

Calculation of weights.

The determination of weights for each criterion followed the standard AHP procedure of pairwise comparisons using Saaty’s 1–9 scale. Expert judgments were obtained from interviews with ethno-village managers and cross-validated with the findings of the benchmarking and SWOT analyses to minimize individual bias. The aggregated weights, therefore, represent a synthesis of multiple expert perspectives rather than a single subjective opinion.

Nevertheless, it must be acknowledged that the assignment of weights in AHP inherently carries a degree of subjectivity, as it depends on expert assessments and the availability of reliable information. To address this limitation, consistency checks were performed, and the consistency ratio (CR) remained below the accepted threshold (CR < 0.1), confirming the logical coherence of the judgments. Additionally, the integration of multiple data sources increased methodological robustness, ensuring that the weight distribution reflects both practical expertise and empirical evidence.

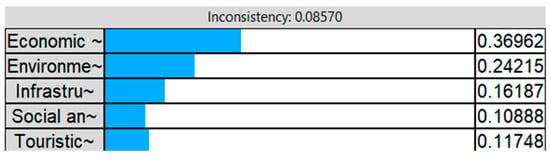

- Consistency validation

In the AHP method, validating the consistency of pairwise comparisons is essential. The consistency index (CI) was monitored throughout the process, with an acceptable value defined as CI < 0.1. In this study, the obtained value (CI = 0.08570) confirmed the consistency and reliability of the results (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Consistency of weights.

Consistency validation during the AHP analysis revealed that economic performance is by far the most important criterion for assessing the sustainability of ethno-villages, accounting for approximately 37% of the total weight. This finding indicates that an ethno-village cannot achieve long-term sustainability without a stable and resilient financial model. Environmental sustainability ranks second (24%), highlighting that the sustainable and responsible management of natural resources is essential for the continued viability of ethno-villages. Infrastructure, representing 16% of the total weight, plays an important role in ensuring accessibility and the quality of tourism services, but does not reach the same level of influence as the economic or environmental dimensions. Touristic attractiveness (12%) and socio-cultural aspects (11%) carry slightly less weight, suggesting that cultural value or destination attractiveness alone is insufficient to achieve high sustainability performance.

Overall, these results demonstrate that ethno-villages with strong business models that integrate sustainable practices are more likely to achieve long-term success. Mere touristic appeal or cultural significance is not enough to ensure sustainability. Achieving a balance between economic performance and the sustainable management of natural and cultural resources represents the core principle of sustainable tourism development.

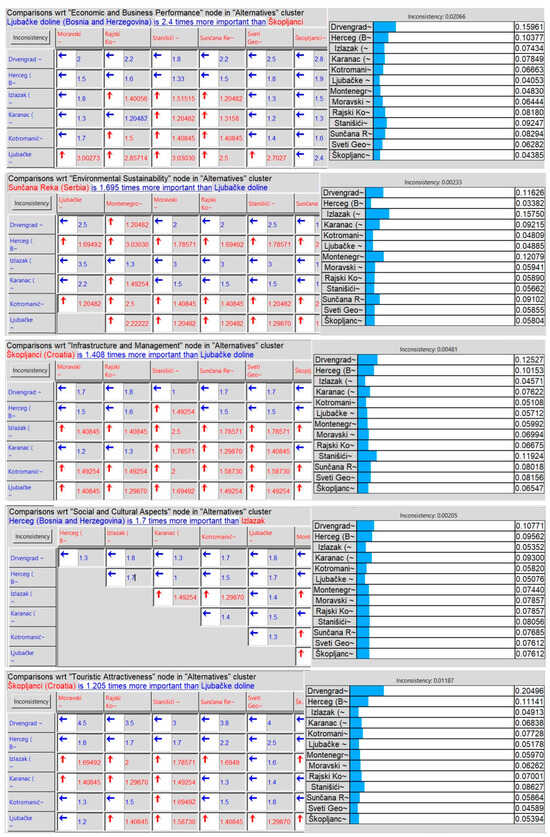

4. Results

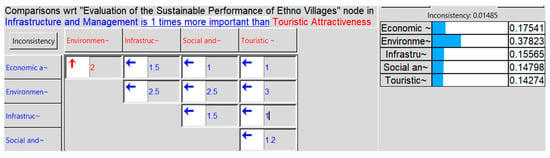

The results of the AHP analysis indicate that economic performance received the highest weight among all sustainability criteria (consistency: 0.087), underscoring that the long-term viability of ethno-villages is most strongly linked to their ability to generate income and maintain financial stability (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Consistency of individual weights. A red arrow (↑) indicates that the row item dominates the column item, while a blue arrow (←) indicates that the column item dominates the row item.

In contrast, touristic attractiveness was assigned a relatively lower weight (consistency: 0.086), suggesting that while the uniqueness and marketing of destinations are valued, they are not perceived as central to sustainability when compared with economic viability. Environmental sustainability (0.081), infrastructure and management (0.084), and socio-cultural aspects (0.085) occupied intermediate positions, showing stable consistency values across expert judgments.

Overall, these findings demonstrate that experts view economic resilience as the cornerstone of sustainable development in ethno-villages, while socio-cultural and environmental dimensions—though important—are regarded as supporting rather than primary drivers of long-term sustainability.

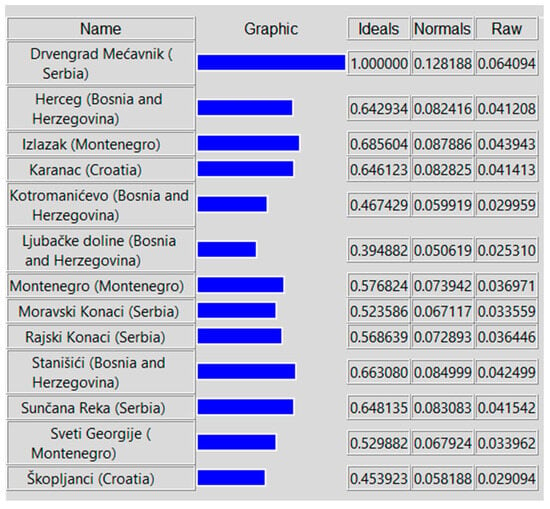

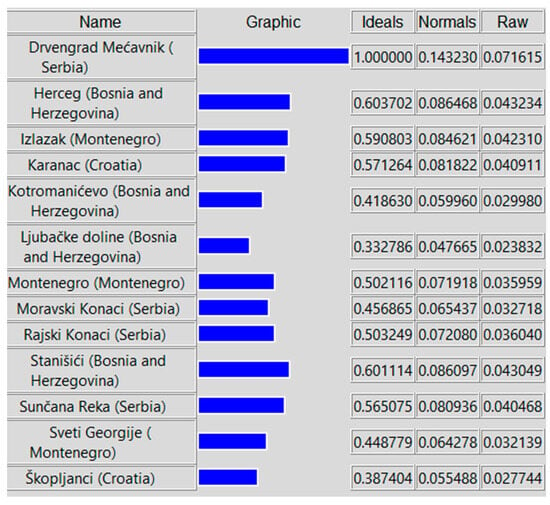

4.1. Final Priority Display

The ranking of ethno-villages based on the AHP synthesis highlights notable differences in their sustainability performance (Figure 5). Drvengrad Mećavnik (Serbia) emerged as the leading destination, significantly outperforming all others across the evaluated criteria. A group of villages, including Herceg (Bosnia and Herzegovina), Izlazak (Montenegro), Karanac (Croatia), and Stanišići (Bosnia and Herzegovina), also achieved relatively strong scores, although their performance remained consistently below Drvengrad’s benchmark.

Figure 5.

Results of relative importance and final priority ranking of ethno-villages based on sustainability performance derived from the AHP synthesis.

The remaining ethno-villages—Kotromanićevo, Ljubačke doline, Montenegro, Moravski Konaci, Rajski Konaci, Sunčana Reka, Sveti Georgije, and Škopljanci—clustered in the lower tier, indicating more limited sustainability capacity. Overall, the results suggest that while several destinations demonstrate strong potential for sustainable development, the majority of ethno-villages still face significant challenges that constrain their ability to achieve comparable levels of performance.

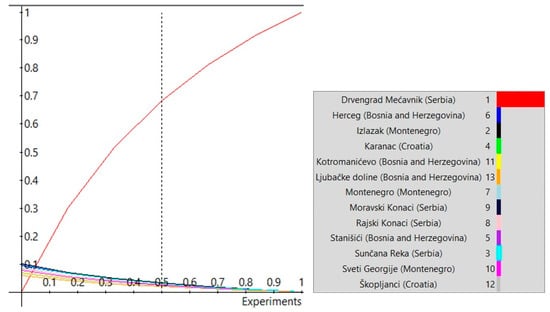

4.2. Sensitivity Analysis

The sensitivity analysis confirmed the robustness of the results across varying criterion weights. As shown in Figure 6, Drvengrad Mećavnik (Serbia)—represented by the red line—consistently remained the highest-ranked destination regardless of changes in weight distribution, demonstrating that its strong performance is not dependent on any single dimension but rather reflects a balanced sustainability profile. Other villages, such as Herceg (blue), Izlazak (black), Karanac (green), Kotromanićevo (yellow), Ljubačke doline (orange), and Montenegro (gray) exhibited only minor shifts in their relative rankings but never surpassed Drvengrad, underscoring the overall stability and reliability of the results.

Figure 6.

Sensitivity analysis of ranking stability across varying criterion weights.

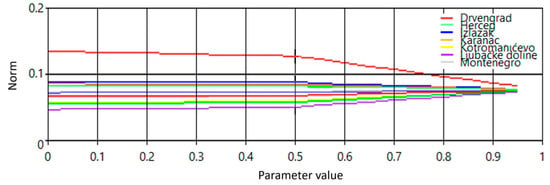

For the environmental sustainability criterion (Figure 7), the results show that changes in the parameter weight had only marginal effects on the ranking outcomes. The lines remain nearly parallel for most of the parameter range, indicating high model stability. The leading destination, Drvengrad Mećavnik (Serbia) (red line), maintained its top position across all weight variations, while other ethno-villages—such as Herceg, Karanac, and Montenegro—displayed only minor fluctuations. However, these fluctuations were modest and did not alter the overall hierarchy. Interestingly, the lines begin to converge at higher parameter values (above approximately 0.8), suggesting that when environmental sustainability becomes dominant in the weighting scheme, the performance differences between ethno-villages diminish. This convergence indicates that under a scenario where environmental criteria overwhelmingly drive evaluation, most destinations reach similar relative importance levels, reducing differentiation based on other factors such as economic performance or infrastructure. In other words, the model becomes less sensitive to inter-village variability when the environmental dimension is overemphasized, reflecting the homogenizing effect of this criterion on final rankings.

Figure 7.

Sensitivity analysis plot for the criterion of touristic attractiveness.

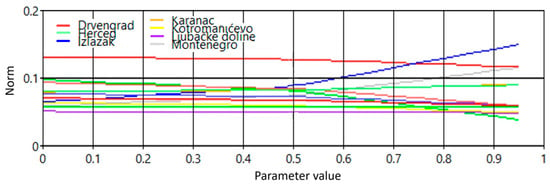

In contrast, the sensitivity analysis for the touristic attractiveness criterion (Figure 8) revealed slightly greater variability among the mid-ranked ethno-villages. As the weight of this criterion increased, Izlazak (Montenegro) (blue line) showed a noticeable upward trend, indicating that its competitiveness is more responsive to tourism-related factors. However, these changes did not substantially alter the overall ranking structure—Drvengrad Mećavnik continued to occupy the top position, confirming the robustness of the AHP model even under extreme parameter adjustments.

Figure 8.

Sensitivity analysis for the criterion of environmental sustainability.

Overall, the results confirm the central importance of economic performance, reveal substantial differences between leading and lower-ranked ethno-villages, and demonstrate the robustness and internal consistency of the model outcomes. The findings clearly show that destinations combining strong business models with investments in infrastructure and responsible environmental management are best positioned to achieve long-term sustainability. In contrast, villages that rely primarily on cultural or aesthetic appeal tend to exhibit weaker performance, indicating that touristic attractiveness alone is not sufficient to ensure competitiveness or resilience.

The sensitivity tests further reinforce the reliability of the AHP model by showing that moderate adjustments in criterion weights do not significantly affect the final rankings. This stability underscores that the model’s results are not overly sensitive to subjective expert judgments but instead reflect consistent patterns across diverse sustainability dimensions. Taken together, these findings provide a solid analytical foundation for the subsequent discussion, where we interpret their broader implications for sustainable ethno-tourism development and policy formulation in the Balkans.

5. Discussion

5.1. Interpretation of Key Findings and Implications for Sustainable Ethno Tourism

The results of the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) model clearly indicate that economic performance is the most significant criterion in evaluating the sustainability of ethno-villages, contributing 36.96% to the overall weighting. This finding emphasizes that without a solid financial foundation, ethno-villages face substantial challenges in achieving long-term sustainability. It aligns with the insights of Stanić Jovanović [], who emphasized the pivotal role of economic stability and business models in ensuring the resilience of rural tourism destinations in Western Serbia. Similarly, Kunakesaran [], in his study of the Mah Meri ethnic group, highlighted that strong economic performance fosters long-term engagement in tourism activities, generates employment opportunities, and supports broader sustainability goals such as cultural preservation. Taken together, these findings underscore that economic viability is not only a precondition for maintaining operations but also a catalyst for preserving cultural identity and strengthening the socio-economic fabric of local communities. Ethno-villages such as Drvengrad [] in Serbia exemplify successful economic sustainability through diversified tourism offerings, local product sales, and partnerships with cultural institutions. Their model demonstrates how economic viability can be maintained through active business strategies that integrate local culture with modern tourist demands.

The second most important criterion is environmental sustainability, accounting for 24.21% of the overall weight. This result underscores the importance of responsible management of natural resources and ecological practices for the long-term viability of ethno-villages. Environmental conservation not only aligns with sustainable tourism principles but also enhances destination attractiveness, as demonstrated in Etno Selo Herceg [], where careful ecological management has been integrated into business operations, enriching visitors’ nature-based experiences. Prevolšek et al. [] further argue that safeguarding environmental assets is essential for sustaining tourism activities and maintaining cultural authenticity within such villages.

Infrastructure and management were ranked third, contributing 16.18% to sustainability. Although not as influential as the economic or environmental criteria, infrastructure remains critical for ensuring accessibility and the quality of the tourist experience. Villages such as Etno Selo Izlazak [] have demonstrated how strategic infrastructural investments—including accessible transportation routes and high-quality accommodations—can significantly improve visitor satisfaction and enhance the economic viability of the destination.

In contrast, touristic attractiveness (11.75%) and socio-cultural aspects (10.88%) received lower weightings. Although these criteria were less influential in the AHP model, they remain essential for shaping the visitor experience and preserving cultural heritage. According to Kljuno and Halilović [], the authenticity of cultural presentations and engagement with local communities are key elements of sustainable tourism. Ethno-villages such as Baranjska Kuća in Karanac have successfully integrated local traditions and gastronomy into their tourism offerings, enriching the cultural experience while supporting local artisans and producers.

These findings reveal that while economic success forms the foundation of sustainability, it must be complemented by responsible environmental practices and strategic infrastructure development. Moreover, the inclusion of cultural authenticity and community engagement, as discussed by Puška et al. [], is critical for enhancing the overall attractiveness and long-term viability of ethno-tourism destinations. The integration of these multidimensional factors aligns with the conceptual model proposed by Nedeljković et al. [], who advocate for a holistic approach to sustainability in rural tourism development.

The implications of these findings are twofold. First, ethno-villages should prioritize building robust economic models while embedding sustainability practices that enhance environmental and infrastructural resilience. Second, continuous investment in social and cultural programs is needed to foster community engagement and preserve local traditions, as exemplified by several successful models observed across the region. These insights not only enrich the existing body of research but also offer practical guidance for stakeholders seeking to promote sustainable ethno-tourism development in the Balkans.

The results of this study align with global trends in the sustainable development of tourism destinations, emphasizing the need to integrate economic, environmental, and social dimensions into the business models of tourism enterprises. The World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) and other international bodies highlight the importance of sustainable management based on local inclusion, responsible resource use, and long-term strategic planning. In this context, the findings correspond with the global imperative to promote tourism development that does not compromise natural and cultural resources but instead contributes to their preservation and enhancement.

Based on these results, it is recommended that the owners of ethno-villages strengthen economic stability through diversification of their offers, enhanced cooperation with local suppliers, and the establishment of long-term business partnerships. It is also essential to develop and implement environmental strategies focused on efficient resource management, reducing environmental footprints, and raising visitor awareness of sustainable behavior. Policymakers should create incentive mechanisms to encourage investments in sustainable practices and infrastructure, while also promoting best practices in sustainable tourism at both national and regional levels.

The lower ranking of several ethno-villages—such as Kotromanićevo, Ljubačke doline, and Rajski Konaci—can be attributed to structural and organizational challenges. These destinations typically face limited financial resources and weaker business models, constraining their ability to ensure long-term economic viability. Infrastructural shortcomings—such as poor accessibility, limited accommodation capacity, and insufficient digital infrastructure—further reduce their competitiveness. Moreover, a lower degree of community involvement and fewer cultural or educational programs weaken their socio-cultural dimension. Similar findings have been reported in previous studies, which emphasize that without strong community engagement and adequate investment in infrastructure, ethno-tourism initiatives often struggle to achieve sustainability [,]. These results suggest that policy interventions and targeted support should focus on addressing the fundamental economic and infrastructural constraints that limit the performance of lower-ranked ethno-villages.

The research results can significantly support strategic orientations aimed at improving the business models of ethno-villages. It will be crucial to develop models that include systematic infrastructure development planning, sustainable natural resource management, and the effective inclusion of local communities. Only in this way can long-term sustainability be achieved, based on a balanced integration of economic, environmental, and socio-cultural factors.

5.2. Scenario Analysis and Methodological Considerations

For a deeper understanding of the impact of individual criteria on the sustainability performance of ethno-villages, two additional scenario analyses were conducted. The purpose of these analyses was to examine how changes in the prioritization of specific criteria influence the final results and alter the ranking of ethno-villages.

- Scenario 1: Emphasis on sustainable tourism

In the first scenario (Figure 9), the weight of the environmental sustainability criterion was increased to examine how a stronger emphasis on sustainable practices would influence the ranking of ethno-villages.

Figure 9.

Change in the weight of the environmental sustainability criterion.

The results (Figure 10) show that Drvengrad Mećavnik (Serbia) maintained its leading position, with its ideal value remaining stable at 1.000 and its normalized value increasing slightly (from 0.128 to 0.143). Ethno-villages such as Montenegro, Stanišići, and Sunčana Reka improved their rankings, indicating that they have more developed environmental sustainability practices, which were favored under this scenario. Conversely, Karanac and Kotromanićevo experienced minor declines in their rankings, suggesting that sustainable tourism is not their primary competitive advantage. Škopljanci and Ljubačke doline remained among the lower-ranked destinations, confirming that their contribution to sustainable tourism remains limited.

Figure 10.

Results after the change—an increase in the weight of the environmental sustainability criterion.

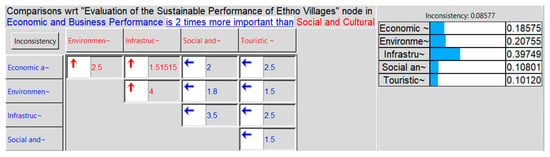

- Scenario 2: Emphasis on Infrastructure

In the second scenario (Figure 11), the weight of the infrastructure and management criterion was increased to analyze whether prioritizing infrastructural development would alter the final ranking of ethno-villages. The weight of this criterion rose to 0.39749, while economic and business performance (0.18575) and environmental sustainability (0.20755) remained important but assumed slightly lower relative weights. This adjustment aimed to evaluate how improvements in accessibility, accommodation quality, and service infrastructure might influence overall sustainability performance across the evaluated destinations.

Figure 11.

Change in the weight of the infrastructure and management criterion.

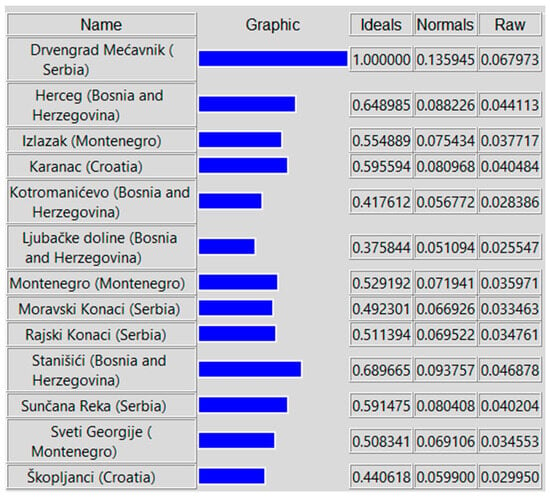

The results (Figure 12) show that the top three destinations remained unchanged, although minor variations occurred in their percentage values. Drvengrad Mećavnik (Serbia) continued to hold the leading position, confirming its consistently strong overall performance. Herceg (Bosnia and Herzegovina) showed a slight improvement (from 0.642934 to 0.648985), suggesting that infrastructure and management play a meaningful role in enhancing its sustainability. In contrast, Izlazak (Montenegro) experienced a moderate decline (from 0.685604 to 0.554889), indicating that its competitiveness is more strongly influenced by other dimensions, such as environmental sustainability or touristic attractiveness, rather than infrastructure alone.

Figure 12.

Results after the change—an increase in the weight of the infrastructure and management criterion.

The largest declines in this scenario were recorded for Kotromanićevo and Ljubačke doline, indicating that their infrastructural capacities are limited and do not constitute a key element of their competitive advantage.

5.3. Contributions, Practical Implications, and Methodological Limitations

Despite the significant findings, this research faces several limitations. The first limitation concerns the sample size, as 13 ethno-villages from four Balkan countries were analyzed. These cases were purposefully selected because they represent some of the most active and recognized ethno-villages in the region, with sufficient data availability and stakeholder engagement. While the number is relatively small, it provides a meaningful and regionally diverse foundation for comparison and for applying the AHP methodology. Although the sample was geographically diverse, a broader study including a larger number of destinations and an extended geographical scope would enable more comprehensive conclusions. The second limitation relates to the availability and depth of data, as some information was collected primarily through interviews and online sources, which may affect the completeness of the analysis. For future research, it is recommended to apply additional multi-criteria decision-making methods—such as the Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS) or the Preference Ranking Organization Method for Enrichment Evaluation (PROMETHEE)—to allow for cross-validation and comparison of results. Moreover, conducting longitudinal studies would provide valuable insights into the long-term sustainability trajectories of ethno-villages. Expanding the research to other Balkan regions or incorporating comparative analyses with other European destinations would further enhance understanding of sustainable development in the context of ethno-tourism. Such approaches would strengthen the scientific foundation of the field and support the formulation of more targeted strategies for improving sustainability outcomes.

The findings of this study carry several practical implications for policymakers, destination managers, and local communities. First, the results underline that strengthening the economic dimension of ethno-villages is essential for ensuring long-term sustainability, emphasizing the need for targeted financial support, entrepreneurial training, and incentives for local product development. Second, the weaker performance of several villages points to infrastructural and managerial challenges, suggesting that investments in accessibility, digital infrastructure, and service quality are equally important for enhancing competitiveness. Third, fostering greater community involvement in tourism activities can improve socio-cultural outcomes and ensure that development remains inclusive and locally rooted.

From an academic perspective, this study contributes to the existing literature on sustainable and indigenous tourism by addressing a key research gap—the lack of systematic sustainability assessments of ethno-villages in the Balkans. While previous studies (e.g., Kunasekaran []; Butler and Hinch []) have examined sustainability indicators in other contexts, this research provides one of the first comprehensive multi-criteria evaluations of ethno-tourism in the region. By applying the AHP method and performing detailed sensitivity analyses, the study demonstrates the robustness of its results and introduces a methodological approach that can be replicated in other rural tourism contexts. The novelty of this research lies in its integration of diverse sustainability criteria into a single analytical framework, enabling the identification of key drivers and barriers to sustainable development, and offering both theoretical and practical contributions to the field.

6. Conclusions

This study applied the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) to evaluate the sustainability of ethno-villages in the Balkans, integrating economic, environmental, infrastructural, social, and cultural dimensions. The findings confirm that economic performance is the strongest determinant of long-term sustainability, while cultural and environmental factors remain essential for maintaining authenticity and resilience. The results also reveal notable disparities between leading and lower-ranked villages, emphasizing the importance of targeted investments, capacity building, and stronger community engagement.

By combining multi-criteria analysis with sensitivity testing, this study introduces a systematic, transparent, and replicable framework for assessing sustainability in rural tourism. The insights provide practical guidance for policymakers, destination managers, and local communities seeking to enhance the resilience, competitiveness, and sustainability of ethno-villages across the Balkan region.

In conclusion, the future of sustainable ethno-tourism in the Balkans depends on achieving a balanced integration of economic viability, cultural preservation, and environmental protection. When supported by coordinated policy frameworks, strategic infrastructure development, and inclusive community participation, ethno-villages can serve as engines of rural development and model examples of sustainable cultural tourism.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.B.G., B.P. and A.Š.; methodology, A.Š., M.B.G. and Č.R.; software, A.C.-M. and A.P.-V.; validation, A.Š.; formal analysis, M.B.G. and Č.R.; investigation, M.B.G., B.P. and Č.R.; resources, A.Š.; data curation, A.P.-V. and A.C.-M.; writing—original draft preparation, M.B.G.; writing—review and editing, A.C.-M.; visualization, M.B.G.; supervision, Č.R. and A.Š.; project administration, M.B.G.; funding acquisition, Č.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors acknowledge the financial support from the Slovenian Research and Innovation Agency (research core funding No. P5-0018 and No. P4-0022) and the Ministry of Higher Education, Science, and Innovation of the Republic of Slovenia as part of the Recovery and Resilience Plan – Next Generation EU (Grant No. 3330-22-3515; NOO No: C3330-22-953012).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was waived for ethical review as, according to Recital 26 of the GDPR and national law, anonymized data are not considered personal data, and therefore no prior ethical approval was legally required by an institution committee.

Informed Consent Statement

Verbal informed consent was obtained from the participants. Verbal consent was obtained rather than written because of the institutional and ethical guidelines.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are not publicly available due to privacy and confidentiality agreements with participants.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the owners and managers of the ethno-villages who generously shared their time and knowledge during the interviews. Their insights were crucial in shaping the findings of this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AHP | Analytic Hierarchy Process |

| SWOT | Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats |

| CI | Consistency Index |

| CR | Consistency Ratio |

| UNWTO | United Nations World Tourism Organization |

| TOPSIS | Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution |

| PROMETHEE | Preference Ranking Organization Method for Enrichment Evaluation |

References

- Wu, J.; Hu, M.; Fu, X.; Deng, H.; Wu, G. Income impacts of rural household livelihood strategies: Insights from Chongqing, Southwest China. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2025, 32, 341–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Yang, L.; Tuyến, N.T.; Colmekcioglu, N.; Liu, J. Factors influencing the livelihood strategy choices of rural households in tourist destinations. J. Sustain. Tour. 2022, 30, 875–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prevolšek, B.; Maksimović, A.; Puška, A.; Pažek, K.; Žibert, M.; Rozman, Č. Sustainable development of ethno-villages in Bosnia and Herzegovina—A multi criteria assessment. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panić, A.; Vujko, A.; Knežević, M. Economic indicators of rural destination development oriented to tourism management: The case of ethno villages in Western Serbia. Hotel. Tour. Manag. 2025, 13, 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kljuno, A.H.; Halilovic, M. The phenomenon of ethno villages in Bosnian rural tourism. Herit. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 4, 122–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedeljković, M.; Puška, A.; Krstić, S. Multicriteria approach to rural tourism development in Republic of Srpska. Eкoнoмuкa noљonpuвpeдe 2022, 69, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raspor, A.; Peršič, K.T.; Kleindienst, P.; Mastilo, Z.; Borojević, D.; Miletić, V. A case study of ethno village in Slovenia and Bosnia and Herzegovina. Econ. Innov. Econ. Res. J. 2020, 8, 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puška, A.; Šadić, S.; Maksimović, A.; Stojanović, I. Decision support model in the determination of rural touristic destination attractiveness in the Brčko District of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2020, 20, 387–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaburaeva, K.S. Ethnocultural heritage of the North-Eastern Caucasus as a factor of eco-tourism development. J. Mt. Sci. 2024, 21, 2810–2824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunasekaran, P.; Gill, S.S.; Ramachandran, S.; Shuib, A.; Baum, T.; Herman Mohammad Afandi, S. Measuring sustainable indigenous tourism indicators: A case of Mah Meri ethnic group in Carey Island, Malaysia. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dernoi, L.A. Farm tourism in Europe. Tour. Manag. 1983, 4, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, J.H.; Zhang, Y.; McDonald, T.; Qi, X. Entrepreneurship in an indigenous community: Sustainable tourism and economic development in a newly inscribed UNESCO world heritage site. In Indigenous People and Economic Development; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2016; pp. 189–204. [Google Scholar]

- Žibert, M.; Prevolšek, B.; Pažek, K.; Rozman, Č.; Škraba, A. Developing a diversification strategy of non-agricultural activities on farms using system dynamics modelling: A case study of Slovenia. Kybernetes 2022, 51, 33–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungaya, G.C. East Africa Community Regional Tourism Policy: The Nexus between Cultural Heritage and Socio-economic Development of the Maasai Community in Serengeti-Mara Ecosystem. J. Kenya Natl. Comm. UNESCO 2024, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, K.T.; Murphy, L.; Chen, T. Segmentation of ethnic tourists and their interaction outcomes with hosts in the Central Highlands, Vietnam. Adv. Southeast Asian Stud. 2024, 17, 105–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamani-Flores, A.; Apaza-Ticona, J.; Calatayud-Mendoza, A.P.; Calderón-Torres, A.; Maquera-Maquera, Y.; Velasquez-Sagua, H.L.; Flores-Chambilla, S.G. The Exercise of Experiential Rural Tourism in the Population Nucleus of an Andean Community in Peru. J. Ecohumanism 2024, 3, 5203–5217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, D.; Zoh, K. Analysis of spatial distribution characteristics and driving factors of ethnic-minority villages in China using geospatial technology and statistical models. J. Mt. Sci. 2024, 21, 2770–2789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, R.; Hinch, T. (Eds.) Tourism and Indigenous Peoples: Issues and Implications; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, P.; Kong, X. Tourism-led commodification of place and rural transformation development: A case study of Xixinan village, Huangshan, China. Land 2021, 10, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E. Authenticity and commoditization in tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1988, 15, 371–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L.K.; Gonzalez, V.V. Indigeneity, sovereignty, sustainability and cultural tourism: Hosts and hostages at ʻIolani Palace, Hawai’i. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 25, 668–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acuña Medina, D.I.; Gañán Rojo, P.F.; Arango Alzate, S.B. Etnoturismo: Una aproximación a las oportunidades y amenazas que implica para las culturas indígenas. Cuad. De Tur. 2019, 43, 17–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. Statistical Framework for Measuring the Sustainability of Tourism (SF-MST): Final Draft. 2024. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/UNSDWebsite/statcom/session_55/documents/BG-4a-SF-MST-E.pdf (accessed on 13 March 2025).

- Recchini, E. Official Statistics for Measuring the Sustainability of Tourism: The UNWTO Initiative; Proceedings e Report; Firenze University Press: Firenze, Italy; Genova University Press: Genova, Italy, 2023; pp. 47–52. [Google Scholar]

- Demonja, D.; Gredičak, T. Contribution to the research on rural resorts in the function of tourism products and services distribution: The Example of the Republic of Croatia. East. Eur. Countrys. 2015, 21, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medojevic, J.; Milosavljevic, S.; Punisic, M. Paradigms of rural tourism in Serbia in the function of village revitalisation. Hum. Geogr. 2011, 5, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluczek, A. Application of multi-criteria approach for sustainability assessment of manufacturing processes. Manag. Prod. Eng. Rev. 2016, 7, 62–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, C. Sustainable tourism as an adaptive paradigm. Ann. Tour. Res. 1997, 24, 850–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, J.; Annandale, D.; Morrison-Saunders, A. Conceptualising sustainability assessment. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2004, 24, 595–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schianetz, K.; Kavanagh, L.; Lockington, D. Concepts and tools for comprehensive sustainability assessments for tourism destinations: A comparative review. J. Sustain. Tour. 2007, 15, 369–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T.L. How to make a decision: The analytic hierarchy process. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1990, 48, 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T.L. The analytic hierarchy process (AHP). J. Oper. Res. Soc. 1980, 41, 1073–1076. [Google Scholar]

- Prevolšek, B.; Gačnik, M.B.; Rozman, Č. Applying integrated data envelopment analysis and analytic hierarchy process to measuring the efficiency of tourist farms: The case of Slovenia. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, P.; Al Aziz, R.; Karmaker, C.L.; Bari, A.M. A fuzzy synthetic evaluation approach to assess the risks associated with municipal waste management: Implications for sustainability. Green Technol. Sustain. 2024, 2, 100087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roussel, Y.; Audi, M. Exploring the Nexus of Economic Expansion, Tourist Inflows, and Environmental Sustainability in Europe. J. Energy Environ. Policy Options. 2024, 7, 28–36. [Google Scholar]

- Ivars-Baidal, J.A.; Vera-Rebollo, J.F.; Perles-Ribes, J.; Femenia-Serra, F.; Celdrán-Bernabeu, M.A. Sustainable tourism indicators: What’s new within the smart city/destination approach? J. Sustain. Tour. 2023, 31, 1556–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasanchay, K.; Schott, C. Community-based tourism homestays’ capacity to advance the Sustainable Development Goals: A holistic sustainable livelihood perspective. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 37, 100784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T.L.; Zoffer, H.J.; Vargas, L.G.; Guiora, A. The Analytic Hierarchy Process: Beyond “Getting to Yes” in Conflict Resolution. In Overcoming the Retributive Nature of the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Geospatial Information Section. Map of the World. United Nations. Available online: https://www.un.org/geospatial/content/map-world-0 (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Lane, B. What is rural tourism? J. Sustain. Tour. 1994, 2, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramwell, B.; Lane, B. Critical research on the governance of tourism and sustainability. J. Sustain. Tour. 2011, 19, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivars-Baidal, J.A.; Celdrán-Bernabeu, M.A.; Mazón, J.N.; Perles-Ivars, Á.F. Smart destinations and the evolution of ICTs: A new scenario for destination management? Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 22, 1581–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, K.; Mátyás, S.; Hegedűs, M.; Kaszás, N.; Rahmat, A.F.; Dávid, L.D. Updating the tourism organizational assessment scale. J. Infrastruct. Policy Dev. 2024, 8, 3811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, L.; Sharpley, R. Rural Tourism–10 Years On. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2004, 6, 119–124. [Google Scholar]

- Crouch, G.I.; Ritchie, J.B. Tourism, competitiveness, and societal prosperity. J. Bus. Res. 1999, 44, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Y.; Zhao, S.; Zhang, X.; Li, J.; Yan, Y.; Gao, J. Bibliometric analysis of sustainable rural tourism. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2025, 12, 788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Hall, C.M.; Scott, D. Tourism and Water. Available online: https://www.degruyterbrill.com/document/doi/10.21832/9781845415006/html (accessed on 13 May 2025). [CrossRef]

- Buckley, R. Sustainable tourism: Research and reality. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 528–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serio, R.G.; Giuliani, D.; Dickson, M.M.; Espa, G. Going green across boundaries: Spatial effects of environmental policies on tourism flows. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.03608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, G. Cultural tourism: A review of recent research and trends. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2018, 36, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timothy, D.J. Cultural Heritage and Tourism: An Introduction; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2011; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Turčinović, M.; Vujko, A.; Stanišić, N. Community-led sustainable tourism in rural areas: Enhancing wine tourism destination competitiveness and local empowerment. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, R. Tourism destination development: The tourism area life cycle model. Tour. Geogr. 2025, 27, 599–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpley, R. Tourism Development and the Environment: Beyond Sustainability? Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Pato, M.L.; Duque, A.S. Mapping Innovation and Sustainability in Rural Tourism: A Bibliometric Approach. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saputra, P.E.D.; Srinadi, I.G.A.M.; Susilawati, M.; Kencana, I.P.E.N.; Octavanny, M.A.D.; Gandhiadi, G.K. Wakatobi Development Priorities as A Sustainable Tourism Destination Using the Analytical Hierarchy Process Method. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2024, 1, 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsaur, S.H.; Wang, C.H. The evaluation of sustainable tourism development by analytic hierarchy process and fuzzy set theory: An empirical study on the Green Island in Taiwan. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2007, 12, 127–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabo, Z.K.; Szádoczki, Z.; Bozóki, S.; Stănciulescu, G.C.; Szabo, D. An Analytic Hierarchy Process Approach for Prioritisation of Strategic Objectives of Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stofkova, J.; Krejnus, M.; Stofkova, K.R.; Malega, P.; Binasova, V. Use of the analytic hierarchy process and selected methods in the managerial decision-making process in the context of sustainable development. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T.L.; Vargas, L.G. Decision Making in Economic, Political, Social, and Technological Environments with the Analytic Hierarchy Process; RWS Publications: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 1994; Volume 7. [Google Scholar]

- Stanić Jovanović, S.; Ilić, B.; Miletović, N. Is Rural Tourism a Chance for Development and Revitalisation of Aranđelovac Municipality? In Sustainable Agriculture and Rural Development V: Book of Abstracts; Institute of Agricultural Economics: Belgrade, Serbia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Drvengrad. 2025. Available online: https://mecavnik.info/ (accessed on 13 March 2025).

- Etno Selo Herceg. 2025. Available online: https://etno-herceg.com/en/home/ (accessed on 13 May 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).