Abstract

Noise exposure in urbanized environments poses a growing challenge to human health and well-being. Consequently, there is an urgent need to identify and preserve areas with high acoustic quality to support restorative experiences in urban environments. This study examined the soundscape of the Two Ponds Golf Course in Trzciana, Poland, and evaluated its potential as a setting for acoustic and psychological regeneration. A mixed-method design was adopted, integrating a questionnaire survey of 36 players (n = 36), binaural sound recordings, and landscape analysis. The results indicated that 63% of respondents evaluated the sound environment positively, highlighting the dominance of natural sounds (birds, wind, and amphibians), complemented by golf-related and rural background sounds. Only 13% of respondents perceived the sounds as disruptive. Occasional negative acoustic events, such as aircraft overflights or lawnmower activity, occurred infrequently and had a limited influence on the overall positive perception of the site. These findings suggest that suburban golf courses may function as “soundscape refugia,” providing restorative auditory experiences while supporting biodiversity conservation.

1. Introduction

Although golf courses are widely recognized for their recreational and ecological functions, their contribution to high-quality soundscapes in urban and suburban environments remains largely unexplored. Originating in the coastal landscapes of Scotland more than 700 years ago, golf has evolved from courses shaped by natural terrain to carefully designed facilities that are distributed worldwide. While early golf courses were often linked to intensive land transformation, contemporary design approaches prioritize sustainability. Recent trends highlight water conservation, biodiversity protection, and the incorporation of natural elements such as woodlands, wetlands, and meadows [1]. Consequently, golf courses are now perceived not only as sporting arenas but also as multifunctional elements of green infrastructure that deliver ecosystem services, including urban cooling, stormwater retention, and pollinator support [2]. However, concerns remain regarding their environmental impact, such as habitat fragmentation and high resource consumption [3,4]. In response, initiatives such as the GEO Foundation for Sustainable Golf have promoted certification schemes that prioritize nature conservation, resource efficiency, and climate action. This perspective posits that golf courses are potential contributors to sustainable development, particularly in urban and suburban areas.

One dimension that has received comparatively little attention is the acoustic environment of golf courses. In urbanized societies, people are increasingly exposed to anthropogenic noise, which adversely affects their health and well-being [5,6]. In contrast, natural soundscapes, such as those in parks and forests, are known to support psychological restoration and stress reduction [7,8]. Given their ecological and recreational value, golf courses have the potential to serve as tranquil acoustic refugia within noisy suburban environments, yet their contribution to human well-being remains underexplored.

Although primarily designed for recreation, golf courses have increasingly been recognized as multifunctional landscapes within urban and suburban contexts. Research has demonstrated that these spaces contribute to ecological sustainability by preserving vegetation cover, maintaining habitat connectivity, and providing ecosystem services, such as stormwater retention and urban cooling [2,9]. Out-of-play areas can be transformed into habitats that enhance biodiversity, support pollinators, and promote natural pest control [10]. Studies suggest that golf courses may offer higher ecological value than other forms of urban green space, particularly in densely built environments, as they support species of conservation concern and contribute to the joint goals of conservation, restoration, and recreation [11].

Despite this growing body of ecological research, the acoustic dimensions of golf courses have largely been overlooked. Existing studies have highlighted the ecological benefits of golf courses [1,2]; however, their role in shaping soundscapes has not been examined systematically. This omission is significant, given that soundscapes, defined as the totality of acoustic features within an environment, encompassing biological (biophony), geophysical (geophony), and anthropogenic (anthropophony) components, are increasingly recognized as indicators of ecosystem health and human well-being [12,13].

Studies on urban green spaces have suggested that natural soundscapes can mitigate the perception of anthropogenic noise, mask traffic disturbances, and enhance overall acoustic comfort [10,14]. Birdsong, insect buzzing, and other biophonic elements are often perceived as more pleasant and restorative than urban noise, thereby contributing to improved subjective well-being. Because golf courses maintain extensive vegetated areas, they have the potential to act as soundscape refugia pockets of relative acoustic quality within otherwise noisy suburban environments.

The emerging field of ecoacoustics has provided conceptual and methodological tools for evaluating these dimensions. By integrating acoustic monitoring into ecological assessments, researchers can gain insights into the patterns of biodiversity, habitat quality, and long-term environmental changes [12]. When applied to golf courses, ecoacoustic approaches can reveal how these landscapes support natural soundscapes, offer refuge from urban noise, and contribute to human well-being.

In summary, although golf courses are well established as providers of ecological services and biodiversity benefits, their potential contribution to soundscape quality remains underexplored. This gap represents a missed opportunity to leverage golf courses as multifunctional green infrastructure that enhances both ecological resilience and quality of life in urban and suburban areas. Targeted research on golf course soundscapes is urgently needed to bridge this knowledge gap and to inform integrative management strategies.

Although the ecological value of golf courses is increasingly recognized, overlooking their potential as acoustic refugia represents a missed opportunity to harness these landscapes as tools for improving quality of life in urban and suburban contexts. Natural soundscapes can play a crucial role in mitigating the negative impacts of noise pollution; however, the acoustic dimensions of golf courses have not been studied systematically. Addressing this research gap is essential to advancing soundscape ecology and sustainable urban landscape planning. This study addresses this gap by investigating the acoustic environment of the Two Ponds Golf Course in Trzciana, near Rzeszów, Poland.

Recent methodological advances in soundscape research, formalized in the ISO 12913 [15,16,17] series of standards published by the International Organization for Standardization, provide an internationally recognized framework for defining, measuring, and analyzing soundscapes based on human perception. The three parts of this standard—ISO 12913-1:2014 (Acoustics—Soundscape—Part 1: Definition and conceptual framework), ISO 12913-2:2018 (Acoustics—Soundscape—Part 2: Data collection and reporting requirements), and ISO 12913-3:2019 (Acoustics — Soundscape—Part 3: Data analysis)—promote a comprehensive approach integrating acoustic, contextual, and social dimensions [15,16,17].

This study follows these methodological principles by combining perceptual data from questionnaire surveys with objective acoustic recordings and landscape analyses. The applied Soundscape Indices (SSID) protocol [18] operationalizes the ISO framework by linking subjective evaluations with quantitative acoustic and environmental indicators.

The main objectives of this study are as follows:

- Identify and characterize the types of sounds present in different course zones;

- Assess how these sounds are perceived by golfers;

- Analyze how landscape composition influences the acoustic environment.

To achieve these objectives, we employed a mixed-method approach that integrated binaural sound recordings, questionnaire surveys, and landscape analyses. This combination provides both quantitative and qualitative insights into how golf courses function as potential soundscape refugees in suburban settings. The findings aim to inform sustainable management practices that conserve biodiversity, enhance the soundscape quality of urban and suburban green infrastructure, and promote human well-being. Ultimately, the study contributes to the conceptualization of golf courses as therapeutic landscapes and potential “soundscape reserves” that strengthen ecological resilience and improve quality of life.

2. Materials and Methods

Understanding the soundscape of a location requires the consideration of multiple dimensions. Among these, the social and subjective perception of sounds is particularly important, as individual characteristics strongly influence the perception of acoustic environments [19]. A questionnaire survey was administered to assess these dimensions. The subjective information was then compared with objective measurements obtained through binaural recordings [18]. In addition, an analysis of the visual and functional landscape features was conducted at two spatial scales to explain the occurrence and distribution of the identified sounds [20]. The integration of these three approaches (social, acoustic, and landscape) enables a comprehensive assessment of the soundscape (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Overview of the methodological framework applied in this study.

2.1. Study Area

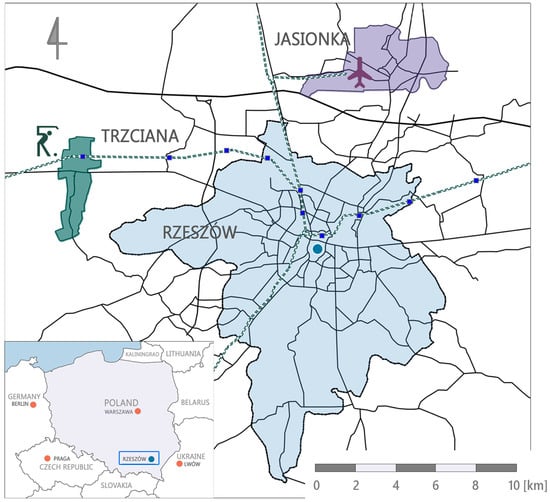

The research was conducted at the “Two Ponds” Golf Course, located in Trzciana, southeastern Poland, approximately 13 km west of Rzeszów (Figure 2). The facility covers 56 ha, comprises nine holes (PAR 3, 4, and 5), and serves approximately 100 players, one-third of whom are women with an average age of approximately 50 years. The Two Ponds Golf Course attracts a diverse yet relatively homogeneous group of players in socioeconomic terms. According to information provided by the golf course administration, most players are local residents of the Rzeszów metropolitan area, employed in professional or managerial occupations and representing a middle-income profile. The course operates as a semi-public suburban facility, offering both membership and open access for training sessions, tournaments, and educational events, which partially reduces its exclusivity compared to private clubs.

Figure 2.

Location and transport links of the Two Ponds Golf Course in relation to the regional capital, Rzeszów.

Its suburban location, proximity to an international airport, and lack of comparable facilities in the region make it the most significant golf course in southeastern Poland. Two retention ponds, created in 2002, represent the most distinctive landscape elements that shape both ecological conditions and the acoustic environment.

2.2. Data Collection

A mixed-method approach was adopted, combining questionnaire surveys, binaural recordings, and landscape analysis:

- Questionnaire survey: A face-to-face survey was conducted between April and July 2023, immediately after the play. The survey was conducted using a sample of 36 respondents. The sample comprised 17 women (47%) and 19 men (53%). Most of the players, that is, 13, were in the age group 41–55. Table 1 shows the distribution of respondents according to sex and age group.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of respondents (n = 36).The respondents were asked to recall and evaluate the sounds they noticed during the game. The reported sounds were classified as relaxing, restorative, pleasant, neutral, bothersome, and annoying. Each participant was also provided with a course map to indicate the locations where the sounds were perceived to be the most influential. The survey followed the perceptual evaluation principles outlined in ISO 12913-2:2018 and the affective dimensions proposed by Axelsson et al. [21], using categories such as relaxing, pleasant, neutral, bothersome, and annoying to describe respondents’ soundscape experiences. A non-probability convenience sampling strategy was applied, as access to the population of active golf players was limited to members and guests of the Two Ponds Golf Course. This approach is consistent with exploratory soundscape studies that emphasize perceptual diversity over statistical representativeness [18,19].

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of respondents (n = 36).The respondents were asked to recall and evaluate the sounds they noticed during the game. The reported sounds were classified as relaxing, restorative, pleasant, neutral, bothersome, and annoying. Each participant was also provided with a course map to indicate the locations where the sounds were perceived to be the most influential. The survey followed the perceptual evaluation principles outlined in ISO 12913-2:2018 and the affective dimensions proposed by Axelsson et al. [21], using categories such as relaxing, pleasant, neutral, bothersome, and annoying to describe respondents’ soundscape experiences. A non-probability convenience sampling strategy was applied, as access to the population of active golf players was limited to members and guests of the Two Ponds Golf Course. This approach is consistent with exploratory soundscape studies that emphasize perceptual diversity over statistical representativeness [18,19]. - Binaural recording: Objective acoustic data were collected using Roland CS-10EM in-ear binaural microphones (Roland Corporation, Hamamatsu, Japan) connected to an Olympus LS-P4 digital recorder (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). Recording parameters followed standard settings recommended for environmental soundscape surveys [17]: a sampling rate of 48 kHz and a bit depth of 24 bits. Prior to recording, the system was calibrated using a 1 kHz reference tone, and basic wind protection was applied. The recording was performed on 22 June 2023 at 16:00, corresponding to the peak playing hours identified in the questionnaire survey. Weather conditions were stable, with no precipitation, a temperature of approximately 24 °C, and light wind below 3 m/s. These conditions ensured minimal external interference and represent typical acoustic circumstances of the golf course during recreational use. The researcher followed the standard playing path from the clubhouse through all nine holes and back, producing an 87 min continuous binaural recording that captured both natural and anthropogenic sounds present during typical course activity. Although a single traverse was recorded, the chosen timing reflected the typical acoustic conditions of the site during peak activity hours. The purpose of this measurement was exploratory, to document the representative structure and diversity of sounds experienced during regular course use.

- Landscape analysis: Land cover and vegetation structure were analyzed using orthophotography maps from the National Geoportal [22] and field surveys, which made it possible to verify the digital data in the field. Figures for this analysis were drawn in AutoCAD 2024 (Autodesk Inc., San Rafael, CA, USA). The landscape analysis was conducted at two spatial scales:

- Course scale: types and distribution of greenery (roughs, fairways, ponds, and trees).

- Contextual scale: land cover within 1 km (N, E, W) and 2 km (S) of the clubhouse, including meadows, agricultural land, forest patches, and transport infrastructure (local roads, a railway line, and national road 94).

To visualize the integration of research methods, including the spatial distribution of sound perceptions within the study area, an orthophotomap obtained from the National Geoportal [22] was used as the cartographic base. Locations identified by respondents during the survey as positive, negative, or neutral in terms of acoustic experience were plotted on the map using QGIS 3.22 ‘Białowieża’ (QGIS Development Team, Open Source Geospatial Foundation, Beaverton, OR, USA), Open Source Geospatial Foundation Project). Each category was represented by a distinct color to illustrate differences in auditory perception across the golf course. The map was further supplemented with the paths of binaural recordings conducted along the main circulation routes of the course.

2.3. Data Analysis

Survey responses were coded into three categories of sounds (natural, golf-related, and surrounding) and statistically analyzed. The normality of the distribution was verified using the Shapiro–Francia test [23]. Where assumptions were not met, non-parametric alternatives were applied, including permutation tests for mean comparisons [24] and Pearson’s chi-squared test [25]. Clustering was performed using the k-means algorithm to explore the perceptual patterns among respondents [26].

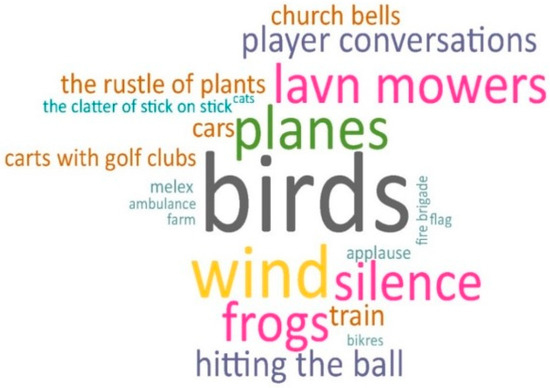

In order to summarise raw texts from open questions, a word cloud can be used. A word cloud is created by first collecting a set of raw texts and cleaning them—this usually means removing punctuation, numbers, and common stop words like “the” or “and.” Then, the text is split into individual words, and the frequency of each word is counted. Words that appear more often are displayed larger, while rare words appear smaller. Finally, the words are arranged visually, often in random or artistic patterns, to show at a glance which terms are most common in the text. Word cloud was used to summarize all raw texts from our questionnaire from the question “Name the sounds you heard on the golf course today that you can remember.”

Finally, triangulation was achieved through the integration of three methods: the survey captured subjective perceptions, binaural recordings documented the objective acoustic environment, and landscape analysis explained the spatial drivers of sound occurrence.

3. Results

3.1. Social Perception of Sounds

Respondents most often mentioned sounds associated with nature (e.g., birds, wind, frogs) when asked to name and list the sounds they heard on the golf course. Some players attempted to identify the birds they heard (e.g., ducks, corn crakes, cuckoos, and pheasants), highlighting the variety of bird sounds that were heard. The sounds of lawnmowers, airplanes, and trains are also important. The composition of sounds was completed by sounds associated with the game of golf, such as players’ conversations, the clatter of clubs against clubs, and applause (Figure 3). Perceived sound impressions were mostly positive (63% of all responses).

Figure 3.

Word cloud of the sounds perceived by the players during the golf game.

Only 13% of those interviewed said that the sounds they heard were disruptive. Some respondents (39%) expressed concern about the aircraft noise they heard, which was largely associated with the Russian–Ukrainian war and proximity to the Polish–Ukrainian border. This noise was associated with military aircraft, which disturbed people’s sense of security. The noise from cars also raised similar concerns for a small number of people in this study (14%). However, the vast majority of the respondents (63%) praised the space they had just left. Common expressions used by golfers after their games were ‘the croaking of frogs’, ‘the concert of birds’, and ‘the soothing silence.’

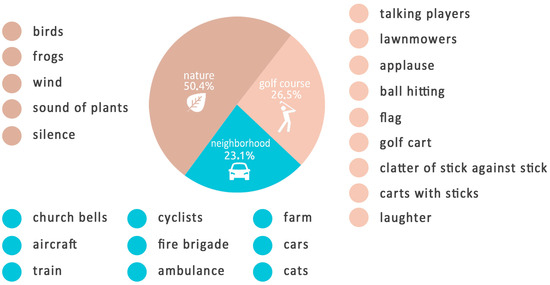

The sounds mentioned by the players were grouped into three main categories: sounds of nature, of golf (golf course), and the golf course surroundings (neighborhood). Sounds belonging to the category of nature sounds represented over 50% of all sounds heard, followed by the second category (golf course), which represented over 26%, and the neighborhood category, which represented over 23% (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Audibility of the three sound categories.

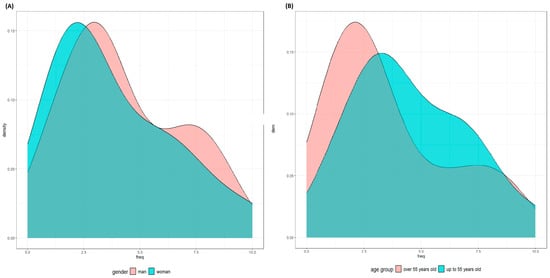

The distribution of the number of sounds heard by sex is shown in Figure 5A, and by age group in Figure 5B. The test for normality of the distribution did not yield a clear result, because the p-value was approximately 0.05. Density plots did not support the normality of the distribution; therefore, a robust version of the two-sample t-test for means was applied. On average, males heard 4.26 different sounds with CI = [3.21, 5.42], which is more than females with an average of 3.88 with CI = [2.71, 5.18], but this was not a statistically significant difference (p = 0.521). It was tested whether the total number of sounds heard by the two age groups of players (‘under 55’ and ‘over 55’) differed significantly. On average, the younger group heard 4.56 different sounds with CI = [3.50, 5.67], which is more than the older group, with an average of 3.61 with CI = [2.50, 4.83], but this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.1837).

Figure 5.

Sounds heard by sex (A) and age group (B).

Groups of sounds were also compared, that is, nature, golf courses, and neighborhood sounds. Men recognized more natural sounds (2.26 on average with CI = [1.68, 2.95]) than women (1.82 on average with CI = [1.41, 2.24]). On average, young players recognized more natural sounds (2.22 (CI = [1.67, 2.83]) compared to 1.88 (CI = [1.44, 2.44])) and neighborhood sounds (1.55 (CI = [1.11, 2.06]) compared to 1 (CI = [0.56, 1.50])).

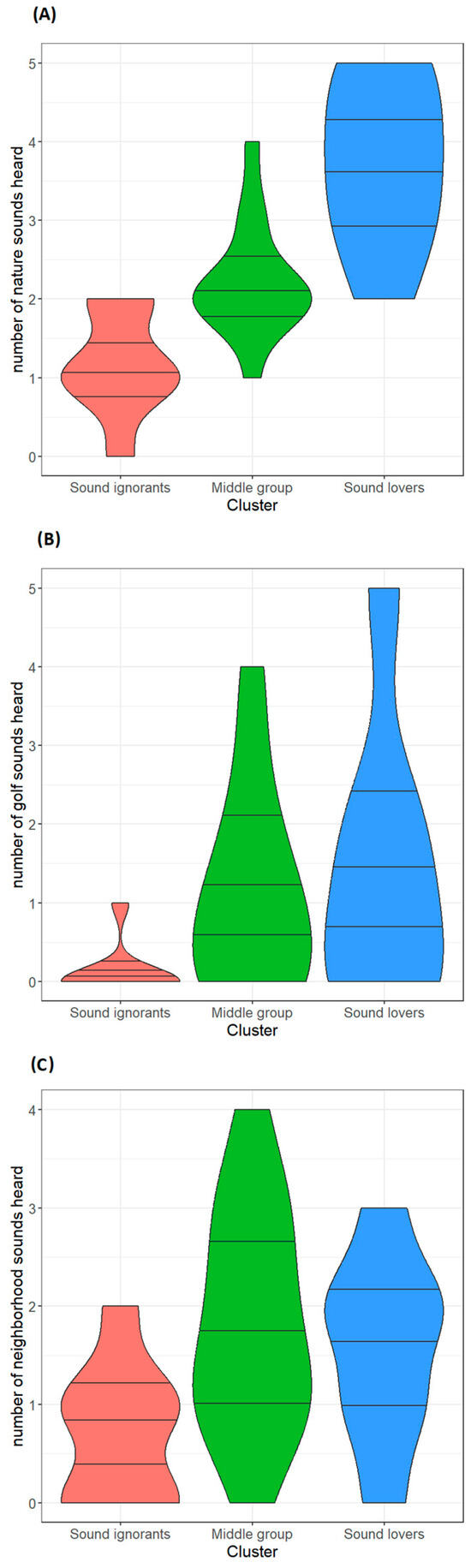

Finally, each sound was examined in terms of its sex and age group. Men were more likely to indicate ‘silence’ (n = 9, 47.4%) than women (n = 2, 11.1%). Younger players were more likely to identify the sound of an airplane (n = 9, 50%) and frogs (n = 8, 44.4%) than were older players (n = 5, 27.8% in both cases). The observed differences led us to investigate whether there are global patterns that capture variations in many aspects of sound perception on a golf course. To this end, the k-means technique was applied to reveal clusters of golfers, that is, groupings of players with similar sound perceptions of sounds. Three player clusters are identified. The first cluster (sound ignorants) included players who generally heard a few sounds, regardless of the type of sound. They rarely found sounds that are relaxing, soothing, or pleasant. They found them neutral most often. In the second cluster (middle group), players were most likely to notice the environmental sounds. Almost all the participants found the sounds relaxing or pleasant, and only a few found them annoying. The third group (sound lovers) perceived the greatest variety of sounds. There have been several assessments of the sound values. The majority found them relaxing and pleasant, while simultaneously finding many other sounds annoying. The violin plots below show the distribution of the number of sounds heard by the participants in the identified clusters (Figure 6). The three horizontal lines indicate the first, second, and third quartiles, respectively. The effectiveness of clustering was evident between clusters, particularly for natural and golf sounds (Figure 6A,B). Typical group representatives are represented by cluster centers, which are calculated as the arithmetic mean of the variables used for clustering.

Figure 6.

Violin plots showing the distribution of the number of sounds reported by individuals from the identified clusters: (A) nature sounds, (B) golf-related sounds, and (C) neighbourhood sounds..

Pearson’s chi-squared test showed a significant relationship between cluster and sex and between cluster and age group. The p-values are 0.012 and 0.045, respectively. The third cluster was dominated by males, and the second by females. Older golfers comprised the majority of the first cluster, in contrast to the second cluster, which contained mostly young golfers.

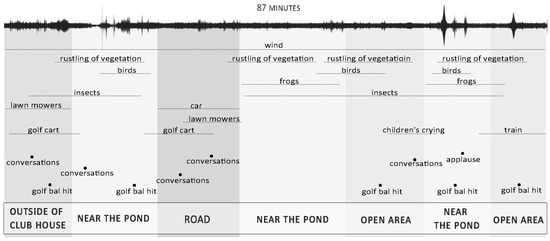

3.2. Objective Sound Recording

The results of the binaural recordings showed the actual soundscape of the golf course. The entire recording lasted for 87 min, during which several types of sounds were identified (Figure 7). The players on the course are accompanied by the sound of the wind, complemented by numerous natural sounds, including those of birds, frogs, and insects (dragonflies, crickets, etc.). These sounds were continuous and lasted up to several minutes each, and wind noise was present throughout the recording. The croaking of amphibians was particularly audible near the two retention ponds and was continuous in several course segments, contributing to the perception of a dynamic and natural acoustic environment.

Figure 7.

Diagram showing the path of the binaural recording made across the golf course, with descriptions of the recorded sounds. Dominant natural sounds included birds, wind, and frog calls, complemented by players’ voices, rustling of vegetation, and occasional anthropogenic noises such as golf cart movement or lawn mower operations.

Noises associated with the golf game, such as clubs hitting the ball, players talking, and applause, were also recorded. These provide accents for the composition of the soundscape.

The recordings also showed the presence of sounds generated by the surroundings of the golf course. In fact, the subdued composition of natural sounds is complemented by sounds generated in the immediate vicinity of the course, that is, the sounds of animals and farm work, church bells, and children playing. The nature of these sounds is characteristic of rural landscapes, whose auditory and visual qualities are often described as idyllic [27,28].

The harmonious picture of sounds is sometimes interrupted by contrasting atmospheres, such as the sounds of cars or the clattering of trains. A distinct ‘clash’ in the soundscape of the field is the sound of lawnmowers.

3.3. Identification of the Landscape of the Golf Course and Its Surroundings

3.3.1. Scale of the Golf Course

The Two Ponds Golf Course is situated in the northern part of Trzciana in the commune of Świlcza. It is one of the largest communes in the Rzeszów district, and Trzciana is the third largest commune seat in this commune. It is located on the border between the Carpathian Foothills and the Sandomierz Basin. The location of the commune and its geological structure influence the landscape value. The area is dominated by loess highlands, crossed by fairly deep stream valleys with occasional loess ravines [29].

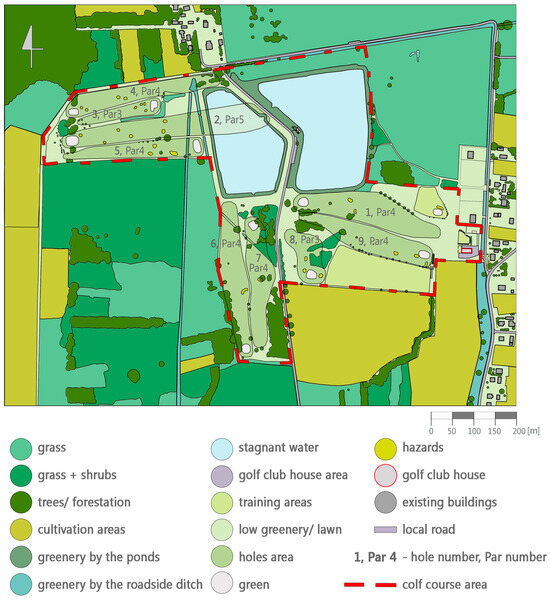

Within and adjacent to the golf course area, peaty soils are present, and the slope of the area is negligible. The golf course area is bordered to the north mainly by undeveloped land, including meadows, shrubs, cultivated land, and wooded areas adjacent to low-rise residential buildings. To the northwest, the golf course area is bordered by the Dąbry forest, which covers an area of over 1300 ha [22]. To the west, in the immediate vicinity of the golf course, there are no built-up areas, but mainly grass and bushes, with a smaller proportion of tall green and cultivated land. To the south, there are cultivated areas, meadows, bushes, and tall trees in the immediate vicinity of the golf course. To the east, the study area is bordered by meadows, shrubs, and low buildings along a local road. It extends along the eastern and northern sides of the golf course and runs through the center of the golf course between the fishponds (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Analysis of greenery in the immediate vicinity of the golf course.

Ponds are the most characteristic features of the course, created in 2002 as retention basins with a total area of approximately 8 ha. Today, they also serve recreational purposes, including active fishing organized by a local angling association. In ponds, there is water vegetation in the form of grass and rush plants, which, together with the ponds, form a characteristic fragment of the landscape. The forms of greenery on the golf courses consist of roughs with grass of different heights and special turf on fairways, tees, and greens. Taller grass, shrubs, and trees of varying heights were also present in nine holes.

The highest density of different types of greenery in the course was in the central part of the course, near the 1st green, the 8th and 9th tees, the 7th green, and the 8th tee. This area is adjacent to ponds in the north. A local road passes between the two ponds, then runs between the areas of golf holes 7 and 8, and continues further south toward the railway station. Therefore, this is potentially the location where greenery, ponds, and roads running through them have the greatest impact on the variation in auditory stimuli for players walking the following holes.

An analysis of the greenery forms of the Two Ponds Golf Course (Figure 8) showed that trees and shrubs occupied approximately 11.3% of the course area and approximately 22.5% of the pond area. This indicates that grassed areas of the Trzciana golf course occupy just over 66% of the course area.

In summary, the immediate surroundings of the golf course comprise various forms of greenery, ranging from the dominantly low, medium–high, and tall. There is a variety of grass, shrubs, trees, and cultivated areas. Situated on flat terrain, the course is characterized by extensive views in all directions. A small number of tall trees/woodlands means that players are more exposed to wind and long-distance sounds. This is particularly noticeable on the south side, where the railway line and main road No. 94 run a little farther away.

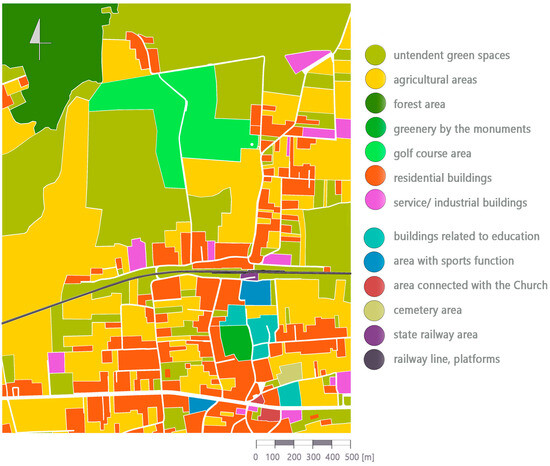

3.3.2. Scale of the Spatial Context

Two analyses were conducted for this spatial extent: transportation and land cover functions. First, we can see the distribution of local roads, railway lines with stops, main road No. 94, and public car parks. The railway line and main road run in an east–west direction. The distance of the golf clubhouse from the railway line in a straight line was approximately 800 m, and that of the main road No. 94 was approximately 1600 m. It can be seen that the local road network is mainly developed on both sides of the main road and around the railway stop in Trzciana. In the vicinity of the golf course, there are only two roads that mainly serve local residents in the immediate area and do not generate much noise (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Analysis of the transportation network.

The analysis of land cover functions shows the extent to which the land is developed for different functions. Along roads, there is mainly low-rise residential development, sometimes with a service or industrial function. It was more dispersed to the north of the railway line and denser to the south. There are also other functions and more diverse buildings between the railway line and the main road No. 94. Land is also associated with educational, sports, and religious functions. In contrast, the proportion of biologically active areas was much higher than that of built areas (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Land cover analysis in the vicinity of the Two Ponds Golf Course in Trzciana.

The location of the Two Ponds Golf Course in a rural area, where ‘green’ terrain and low-rise buildings predominate, allows for a better separation from many ‘urban’ auditory stimuli. This creates space for the sounds of nature, conditioned by the presence of various forms of greenery or waterfront areas.

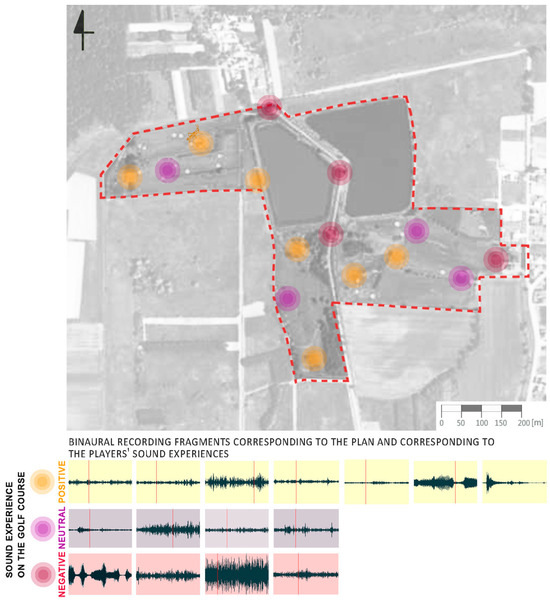

3.4. Integration of Research Methods

The integration of research methods, including the questionnaire survey, analysis of the binaural recording, and analysis of land cover and greenery forms, made it possible to fully identify the soundscape of the Two Ponds Golf Course and to show the strong relationship between the sounds identified, their evaluation, and the composition of the course (Figure 11). The overwhelmingly positive evaluations of the sounds experienced on the golf course were related to the sounds of nature and resulted from the composition of the course. These sounds, particularly wind noise, were continuous and were present throughout the binaural recording. The addition of sounds from surrounding farms to this composition was also evaluated. Some sound incidents that disrupted the harmonious, subtle soundscape of the field in a contrasting and harsh way, that is, the sounds of lawnmowers, cars, or aeroplanes, were found to be undesirable.

Figure 11.

Comparison of the golf course plan with fragments of the binaural recording and with positively, neutrally, and negatively rated fragments of the course.

4. Discussion

4.1. Golf Course—A Nature Sound Refugia

Sound is a carrier of ecological information, and soundscape ecology researchers often draw on sonic diversity as an indicative, although not fully reliable, measure of biodiversity in natural environments, given its sensitivity to environmental and methodological factors [30]. The surveyed golf course had high natural qualities, confirmed by the dominant sounds of nature on the course, among which bird sounds, wind noise, and rustling of plants were the most frequently mentioned by the interviewees (and confirmed by binaural recording). The variety and multiplicity of bird sounds recorded and recognized in the field may suggest relatively high biodiversity; however, this assumption requires verification through dedicated ecological or bioacoustic monitoring. In addition, the sounds of greenery moving in the wind, such as birdsong, are an important reflection of biodiversity [31,32], which further suggests that golf courses may possess a relatively high natural value; however, this assumption should be verified through direct biodiversity assessments. Sounds associated with natural richness (birds, wind, and plants) also characterize landscapes with high tourist value, as indicated by Lewandowski et al. [27], who analyzed sound sensations in open landscapes with high natural and tourist value. Interestingly, our findings are consistent with those of Lewandowski et al. [27] in terms of the sounds of farm work, which occurred both on our golf course and in a popular riverside tourist landscape.

The coexistence of geophonic and biophonic sounds observed on the golf course suggests that such spaces may function as potential acoustic refugia within urbanized environments, offering partial shelter from anthropogenic noise [33]. This finding is particularly relevant in the context of concerns about the loss of natural sounds, especially in urban environments, as Carson [34] wrote as early as the 1960s. His concerns described half a century ago have not become obsolete; rather, we are seeing increased threats to harmonious soundscapes today [33]. Concern for the protection of natural soundscapes is ultimately a concern for the human psychological state, as scientific research confirms that it is the sound sources characteristic of quiet natural landscapes that have the greatest impact on stress reduction and psychological regeneration [35].

4.2. Golf Course—Therapeutic Landscape

Golfers positively evaluated their auditory experience after completing the game. The duration of the game (at least several tens of minutes) makes the experience of harmonious sounds sufficiently long to experience immersion in the landscape in terms of sound. Landscape immersion, that is, being surrounded by natural sounds, combined with experiencing different textures and other tactile stimuli, including gusts of wind, seems to be an experience similar to landscape therapies, whose positive effects on health have been scientifically proven [36,37].

The concept of therapeutic landscapes, introduced by Gesler in 1992, has initiated multifaceted research on the impact of the environment on human health and well-being [38]. In terms of acoustic impact, it has been noted that wind noise (present throughout our recording), characteristic of open, expansive spaces, is experienced as a non-threatening ‘white noise’ bringing respite. The sounds of animal life, especially birdsong, are often identified in research as joy-inducing sounds [39,40,41,42,43,44]. Other animal sounds, including frogs and cows, which were also present in our golf course, were also soothing [44]. At the same time, some sounds of nature, such as the sound of frogs, are sometimes valued negatively by people [45], which was also repeated in our study, where respondents grouped in cluster 3—sound lovers (Figure 6) evaluated the same sounds heard very differently.

The perception of the golf course as a restorative environment may also reflect the socioeconomic status of its users. Prior research indicates that social class, education, and lifestyle shape environmental attitudes and the valuation of natural spaces—for example, through differences in sense of place, aesthetic preferences, and perceived naturalness of the environment [32,46,47]. In this study, the respondents—mostly middle-income professionals—represent a group with regular access to recreational landscapes, which may underpin heightened sensitivity to auditory quality and tranquility. While this does not diminish the ecological or acoustic value of the site, it underscores the need to broaden future research toward more socially diverse groups to examine whether similar restorative and acoustic benefits are perceived across different socioeconomic contexts.

4.3. Positive and Negative Sound Experiences of Golf Course Users

Sensitivity to auditory stimuli is determined by individual characteristics; however, our study found that people over the age of 55 identified the fewest number of sounds. On the other hand, women (Figure 6, cluster 2—middle group) positively accentuated the sounds generated by the golf course surroundings, such as church bells or sounds from the surrounding farms, but also the clatter of a train, the hum of an aircraft, or the sound of an ambulance. The subtle sounds of nature present on the golf course itself became the backdrop for sound incidents with distinctive sounds and meanings. This is illustrated in the figure showing the results of the binaural recording (Figure 7), where the moments of sound incidents arising largely from the specifics of the immediate vicinity of the course (Figure 11) are clearly marked on the path.

Negative perceptions of the golf course soundscape are primarily associated with aircraft noise. The site in Trzciana is situated within the control zone of Rzeszów–Jasionka Airport, directly under one of its inbound and outbound flight routes (Figure 2). As a result, low-altitude overflights contribute to periodic disturbances in the otherwise natural acoustic environment. This generated specific noise, which was also noted in the surveys of golfers who participated in a study conducted at the Two Ponds Golf Course. However, the respondents admitted that their negative association with these sounds was triggered by their awareness of the difficult war situation in Ukraine. A low-flying aircraft evokes a sense of danger and uncertainty.

The sound of the lawnmowers, which drastically pierced the harmonious composition of the natural sounds of the golf course, was also irritating to the participants. Grass cutting is established on the course at times that do not interfere with the golfers’ play. Lawnmower operators observe the situation on the course and head to remote locations to avoid disturbing the silence or distracting players as much as possible. Despite these efforts, golfers pay attention to the contrasting, harsh sounds of lawnmowers, which stand out strongly from the soothing soundscape of the course.

4.4. Sounds and Composition

The soundscapes of most golf courses share many characteristics with those of the countryside. This is largely owing to the large surface area of the course, which provides an effective buffer to ensure harmonious soundscapes. In addition, the typical design of the golf course landscape is usually related to the natural landscape through a free layout based on rounded shapes and slight undulations of the holes, which, together with the sand bunkers, are reminiscent of the original golf course layout. A typical golf course comprises natural areas that have not been altered by earthworks, as well as several hectares of transformed terrain. Each of the nine (or 18) holes consists of tees, greens, fairways, roughs, and hazards, all of which must be of a certain size to maintain the standards. In a typical golf course, approximately 90% of the area is covered by grass. Of these, greens and tees accounted for approximately 7%, fairways for approximately 22%, roughs of various types for approximately 57%, and the rest (such as green surroundings, tees, bunkers, and others) for approximately 14% [48]. Greens, tees, fairways, and the ‘other’ category (approximately 43% of the total grassland area) require special grass mixtures with appropriate functional and biological properties. These cultivated varieties are often alien to the habitat and require frequent mowing at a height of 3–12 mm. In this way, they are cut off from the landscape context, the link to which may be the rough zone, where different species, including local ones, may be present, and where mowing is infrequent and at a high height or not at all. Trees and shrubs are important elements in the composition of the landscape of a golf course and provide a variety of views from each hole of the course. In this case, species adapted to the habitat conditions should be used. Their spacing and maintenance must ensure adequate development of the turf, including the removal of tree branches up to a height of approximately 3 m to allow the passage of equipment necessary for turf maintenance on the golf course [48]. An additional element could be the use of flowering plants in the form of flower meadows or larger planting beds.

An analysis of the greenery forms of the Two Ponds Golf Course (Figure 8), which shows the percentage of the individual grass surface of the course, shows that it is not a typical course, as the grass surface covers only slightly more than 66% of the total area. Instead, almost a quarter of the course is made up of the two ponds; this has a clear impact on the soundscape, which is enhanced by the flora and fauna of the riparian areas. This is a distinctive feature of the landscape that shapes the course’s unique soundscape.

Currently, golf course design considers the possibility of preserving ecological continuity, existing habitats of fauna and flora, and protecting the environment from the negative effects of earthworks and changes in the water conditions of the development area and surrounding areas [48]. The area of the Two Ponds Golf Course is also similar to the natural landscape owing to the rounded shapes of its composition, natural undulations, presence of late successional vegetation, and presence of water bodies and wildlife. These landscape elements [46,47] had the strongest impact on human health [49].

The research conducted shows that the soundscape of the Two Ponds Golf Course near Rzeszów is an effect of how it is developed: first, the golf course itself; second, its immediate surroundings; and third, its location in the country and in Europe. Natural sounds are strongly correlated with the development of an area. The presence of ponds ensures the presence of frogs, dragonflies, and waterfowl [50]. Native tall trees offer shelter for many wildlife and bird species [51]. Infrequently mown meadows act as insect refugia [52] that fill the landscape with a variety of sounds, evoking associations with idyllic rural landscapes [28]. However, the local road that runs through the field and the anglers’ car parks generate car and motorbike noises, which negatively affect the soundscape of the field. The suburban surroundings of the field, where many social activities characteristic of rural areas are still present (small farms and backyard gardens), complement the soundscape of the field with sounds specific to non-urbanized areas and provide pleasant auditory stimuli. However, not only does the composition and shape of the Trzciana golf course itself and its immediate surroundings determine the range of sounds perceived on the course, but also its location on the map of Europe, in close proximity to Ukraine, triggers various, often negative, interpretations of the sounds occurring on the course.

While the results indicate that the Two Ponds Golf Course supports a predominantly natural soundscape, the absence of calibrated sound level data, spectral analyses, and independent biodiversity assessments limits the ability to establish a direct causal relationship between acoustic diversity and ecological richness. Therefore, the interpretation of the site as a potential “soundscape refugium” should be regarded as indicative rather than conclusive.

4.5. Limitations and Future Research

This study combined subjective surveys with binaural recordings but did not include direct measurements of the sound pressure level. Future studies should integrate acoustic indices, decibel-level mapping, and systematic biodiversity assessments to strengthen the relationship between ecological richness and soundscape quality. The modest sample size (n = 36) of this study, which restricts its statistical generalizability, is a limitation. However, this finding is consistent with exploratory research on soundscape perception [18,19]. The consistency between the subjective and objective evaluations strengthens the reliability of our findings. Future research should extend to larger samples, comparative analyses of different golf course types (e.g., urban, parkland, and links), and standardized acoustic measurements.

The study was based on one binaural traverse, which provided a representative yet time-specific snapshot of the acoustic environment. While this approach is sufficient for an exploratory soundscape characterization, future research should include multiple recordings across different times of day and seasons to capture temporal variability in soundscape composition.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that suburban golf courses can serve not only as recreational facilities but also as acoustic environments of high ecological and perceptual quality. The Two Ponds Golf Course in Trzciana provided predominantly positive auditory experiences, dominated by natural sounds such as birdsong, wind, and amphibians, complemented by subtle anthropogenic sounds related to gameplay and rural surroundings.

The following research objectives were achieved:

- (1)

- The main sound categories were identified through binaural recordings and field observations;

- (2)

- Golfers’ perceptions of the acoustic environment were analyzed in relation to their sex and age;

- (3)

- Links between soundscape characteristics and landscape composition were established.

The findings indicate that golf courses—when designed and managed with ecological sensitivity—can enhance acoustic diversity and support positive sensory experiences within suburban green infrastructure. Although respondents frequently described their experiences as calm or pleasant, the study did not empirically evaluate restorative or stress-reducing effects. These reactions are discussed as interpretative insights within the conceptual framework of therapeutic landscapes.

These findings highlight the multifunctional role of golf courses as components of green infrastructure. Beyond sports and leisure, they support biodiversity conservation and provide cultural ecosystem services through restorative soundscapes. From a design and planning perspective, integrating water bodies, diverse vegetation structures, and ecological corridors enhances both ecological richness and acoustic quality. This underscores the need for landscape architects, planners, and policymakers to consider golf courses in broader strategies for sustainable suburban development, with explicit recognition of their acoustic dimensions.

Future research should build on these findings by incorporating standardized sound measurements, advanced acoustic indices, and biodiversity assessments. Comparative analyses across different golf courses and settings could clarify how landscape composition and location shape soundscapes. Expanding the focus to include interactions with other sensory experiences would provide a more holistic understanding of their restorative potential and support the integration of soundscape quality into sustainable landscape management and design.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.G. and A.S.; methodology, A.G., A.S. and S.W.; validation, A.G., S.W. and A.M.; investigation, A.G. and A.S.; writing—original draft preparation, A.G.; writing—review and editing, A.S. and A.M.; visualization, A.G., A.S., S.W.; supervision, A.G., A.S., A.M.; project administration, A.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (1975, amended in 2013), and approved by the Dean of the Faculty of Civil and Environmental Engineering and Architecture, Rzeszów University of Technology, Poland (statement issued on behalf of the Department of Architecture and Cultural Heritage, April 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available at the following link: https://rdb.ur.edu.pl/handle/item/81 (accessed on 20 October 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Albort-Morant, G.; Leal-Rodriguez, A.L. Pro-environmental culture and behavior to promote sustainable golf courses: The case study of “La Galiana”. In Tourism Innovation: Technology, Sustainability and Creativity; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonsdorf, E.V.; Nootenboom, C.; Janke, B.; Horgan, B.P. Assessing urban ecosystem services provided by green infrastructure: Golf courses in the Minneapolis-St. Paul metro area. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 208, 104022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekken, M.A.H.; Soldat, D.J.; Koch, P.L.; Schimenti, C.S.; Rossi, F.S.; Aamlid, T.S.; Hesselsøe, K.J.; Petersen, T.K.; Straw, C.M.; Unruh, J.B.; et al. Analyzing golf course pesticide risk across the US and Europe—The importance of regulatory environment. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 874, 162498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan-Perkins, E.; Manter, D.K.; Wick, R.; Jung, G. Network analysis of nematodes with soil microbes on cool-season golf courses. Rhizosphere 2023, 28, 100798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raimbault, M.; Dubois, D. Urban soundscapes: Experiences and knowledge. Cities 2005, 22, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, A.; Kowkabi, L. Measuring the Soundscape Quality in Urban Spaces: A Case Study of Historic Urban Area. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, S.; Ma, H. Restorative effects of urban park soundscapes on children’s psychophysiological stress. Appl. Acoust. 2020, 164, 107293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitra, B.; Jain, M.; Chundelli, F.A. Understanding the soundscape environment of an urban park through landscape elements. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2020, 19, 100998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.; Barber, P.; Harper, R.; Linh, T.V.K.; Dell, B. Vegetation trends associated with urban development: The role of golf courses. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0228090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dale, A.G.; Perry, R.L.; Cope, G.C.; Benda, N. Floral abundance and richness drive beneficial arthropod conservation and biological control on golf courses. Urban Ecosyst. 2020, 23, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colding, J.; Folke, C. The role of golf courses in biodiversity conservation and ecosystem management. Ecosystems 2009, 12, 191–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farina, A. Ecoacoustics: A quantitative approach to investigate the ecological role of environmental sounds. Mathematics 2018, 7, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoeman, R.P.; Erbe, C.; Pavan, G.; Righini, R.; Thomas, J.A. Analysis of soundscapes as an ecological tool. In Exploring Animal Behavior Through Sound: Volume 1: Methods; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dein, J.; Rüdisser, J. Landscape influence on biophony in an urban environment in the European Alps. Landsc. Ecol. 2020, 35, 1875–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 12913-3:2019; Acoustics—Soundscape—Part 3: Data Analysis. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/69864.html (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- ISO 12913-2:2018; Acoustics—Soundscape—Part 2: Data Collection and Reporting Requirements. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/75267.html (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- ISO 12913-1:2014; Acoustics—Soundscape—Part 1: Definition and Conceptual Framework. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/52161.html (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Mitchell, A.; Oberman, T.; Aletta, F.; Erfanian, M.; Kachlicka, M.; Lionello, M.; Kang, J. The soundscape indices (SSID) protocol: A method for urban soundscape surveys- Questionnaires with acoustical and contextual information. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aletta, F.; Kang, J.; Axelsson, Ö. Soundscape descriptors and a conceptual framework for developing predictive soundscape models. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2016, 149, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Ye, X.; Chen, J.; Fan, X.; Kang, J. Effect of visual landscape factors on soundscape evaluation in old residential areas. Appl. Acoust. 2023, 215, 109708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axelsson, Ö.; Nilsson, M.E.; Berglund, B. A principal components model of soundscape perception. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2010, 128, 2836–2846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geoportal Spatial Information Infrastructure. Available online: https://www.geoportal.gov.pl (accessed on 14 January 2025).

- Shapiro, S.S.; Francia, R.S. An approximate analysis of variance test for normality. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1972, 67, 215–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Good, P. Permutation, Parametric, and Bootstrap Tests of Hypotheses, 3rd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson, K. On the criterion that a given system of deviations from the probable in the case of a correlated system of variables is such that it can be reasonably supposed to have arisen from random sampling. Philos. Mag. 1905, 30, 157–175. [Google Scholar]

- MacQueen, J. Some methods for classification and analysis of multivariate observations. In Proceedings of the Fifth Berkeley Symposium on Mathematical Statistics and Probability, Berkeley, CA, USA, 21 June–18 July 1965; University of California Press: Oakland, CA, USA; Volume 1, pp. 281–297. [Google Scholar]

- Lewandowski, W.; Szumacher, I. Sound as a landscape value. In Sound in the Landscape as a Subject of Interdisciplinary Research; Works of the Cultural Landscape Committee: Lublin, Poland, 2008; Volume XI, pp. 54–62. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalczykowa, A. Pejzaż Romantyczny; Wydawnictwo Literackie: Kraków, Poland, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Urząd Gminy Świlcza. Strategia Rozwoju Gminy Świlcza na lata 2015-2023-Program Rozwoju-Aktualizacja-Czerwiec 2019; Urząd Gminy Świlcza: Świlcza, Poland, 2018; Available online: https://bip.swilcza.com.pl/index.php/prawo-lokalne/strategia-rozwoju-gminy/3601-strategia-rozwoju-gminy-swilcza-na-lata-2015-2023 (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Alcocer, I.; Lima, H.; Sugai, L.S.M.; Llusia, D. Acoustic indices as proxies for biodiversity: A meta-analysis. Biol. Rev. 2022, 97, 2209–2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairbrass, A.J.; Rennett, P.; Williams, C.; Titheridge, H.; Jones, K.E. Biases of acoustic indices measuring biodiversity in urban areas. Ecol. Indic. 2017, 83, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, J.C.; Irvine, K.N.; Bicknell, J.E.; Hayes, W.M.; Fernandes, D.; Mistry, J.; Davies, Z.G. Perceived biodiversity, sound, naturalness and safety enhance the restorative quality and wellbeing benefits of green and blue space in a neotropical city. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 755, 143095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, J.R.; Burdett, C.L.; Reed, S.E.; Warner, K.A.; Formichella, C.; Crooks, K.R.; Theobald, D.M.; Fristrup, K.M. Anthropogenic noise exposure in protected natural areas: Estimating the scale of ecological consequences. Landsc. Ecol. 2011, 26, 1281–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, R. Silent Spring; Houghton Mifflin Company: Boston, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliffe, E.; Gatersleben, B.; Sowden, P.T. Bird sounds and their contributions to perceived attention restoration and stress recovery. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 36, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, B.; McIntosh, J.; Webber, H. Therapeutic Landscapes: A Natural Weaving of Culture, Health and Land. In Landscape Architecture Framed from an Environmental and Ecological Perspective; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, S.L.; Hickman, C.; Houghton, F. From therapeutic landscape to therapeutic ‘sensescape’ experiences with nature? A scoping review. Wellbeing Space Soc. 2023, 4, 100126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, S.L.; Foley, R.; Houghton, F.; Maddrell, A.; Williams, A.M. From therapeutic landscapes to healthy spaces, places and practices: A scoping review. Soc. Sci. Med. 2018, 196, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duff, C. Exploring the role of ‘enabling places’ in promoting recovery from mental illness: A qualitative test of a relational model. Health Place 2012, 18, 1388–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Völker, S.; Kistemann, T. “I’m always entirely happy when I’m here!” Urban blue enhancing human health and well-being in Cologne and Düsseldorf, Germany. Soc. Sci. Med. 2013, 78, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butterfield, A.; Martin, D. Affective sanctuaries: Understanding Maggie’s as therapeutic landscapes. Landsc. Res. 2016, 41, 695–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jellard, S.; Bell, S.L. A fragmented sense of home: Reconfiguring therapeutic coastal encounters in COVID-19 times. Emot. Space Soc. 2021, 40, 100818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wang, B. Mobilising therapeutic landscapes: Lifestyle migration of the Houniao and the spatio-temporal encounters with nature. Geoforum 2022, 131, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doughty, K.; Hu, H.; Smit, J. Therapeutic landscapes during the COVID-19 pandemic: Increased and intensified interactions with nature. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 2023, 24, 661–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.K.; Park, W.B.; Do, Y. Identifying Popular Frogs and Attractive Frog Calls from YouTube Data. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausmann, A.; Slotow, R.; Burns, J.K.; Di Minin, E. The ecosystem service of sense of place: Benefits for human well-being and biodiversity conservation. Environ. Conserv. 2016, 43, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ode, Å.; Fry, G.; Tveit, M.S.; Messager, P.; Miller, D. Indicators of perceived naturalness as drivers of landscape preference. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 90, 375–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orzechowska, I. Krajobraz w architekturze pól golfowych. Archit. Kraj. 2006, 3–4, 74–79. [Google Scholar]

- Opdam, P. Implementing human health as a landscape service in collaborative landscape approaches. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2020, 199, 103819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowakowski, J.J.; Górski, A.; Lewandowski, K. Amphibian communities in small water bodies in the city of Olsztyn. Fragm. Faun. 2010, 53, 213–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Dudkiewicz, M.; Kopacki, M.; Iwanek, M.; Hortyńska, P. Problems with the experience of biodiversity on the example of selected Polish cities. Agron. Sci. 2021, 76, 67–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wintergerst, J.; Kästner, T.; Bartel, M.; Schmidt, C.; Nuss, M. Partial mowing of urban lawns supports higher abundances and diversities of insects. J. Insect Conserv. 2021, 25, 797–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).