Abstract

The present paper discusses differences in the theoretical behavior of nonconventional biomasses during combustion according to their combustion parameters, focusing on their potential for sustainable energy valorization and their contribution to sustainable development. Data were obtained through thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) of biomasses from the local Galicia–North Portugal Euroregion. The samples tested were raw, nonwoody biomasses, specifically kiwi waste and gorse, and animal-derived biomasses, poultry and turkey manure. A wood pellet was also included as a reference conventional biofuel. Nonwoody biomass samples containing kaolin and calcium carbonate were also tested. Thermogravimetric analyses were performed on each biofuel under an oxidative atmosphere at different heating rates. With these data, different combustion parameters were calculated. The TGA results showed that the mean ignition temperature observed for animal-derived fuels was about 15 °C lower than for nonwoody biomasses at every heating rate, which indicates that they start to burn at lower temperatures. These animal-derived fuels generally presented better combustion parameters, suggesting that their combustion behavior is better; however, their high ash and moisture contents are problematic. These issues would be aggravated in real facilities, making them more difficult to use as fuel. The proportion of additives used had no effect on the parameters at lower heating rates, although they started to modify their tendency at 30 °C/min. For instance, the ignition index for non-additivated kiwi waste was 174.32 (wt. %/min3) × 10−3 compared to 143.78 (wt. %/min3) × 10−3 for kiwi with CaCO3.

1. Introduction

Human progress has long been driven by the pursuit of improved efficiency through technological innovation. However, these advancements have been accompanied by a substantial increase in global energy demand. Since the onset of the Industrial Revolution, energy consumption has risen exponentially, a trend that is expected to persist [1,2]. Historically and presently, this growing demand has been met predominantly through the use of fossil fuels [3].

Fossil fuels are well known for releasing different substances into the atmosphere, which dramatically increases the speed of global warming. The excessive use of these types of energy can cause catastrophic events in the Earth’s future [4,5]. Against this backdrop, the transition towards clean and renewable energy sources is extremely important to ensure long-term sustainable development. Therefore, different governmental groups have committed to taking action to change this scenario, as is the case for Europe and, consequently, Spain.

The actions taken have focused mostly on the use of renewable energy. Biomass plays an interesting role in this area [1], especially in heat production. Biomass can have different origins, such as tree shafts, bark and other woody products, agriculture and livestock wastes, or energy crops [6].

Biomass is considered to be a net zero-carbon energy source because it produces CO2 emissions during its energy utilization that are equal to those captured during the development of the vegetal matter during biomass growth [7]; as it is considered renewable energy, its use has been increasing over the past few years.

The European Union has been actively setting new standards to accelerate a sustainable energy transition. Fit For 55, set on 2021, is one such standard, and its objective is reduce CO2 emissions by 55% by 2030 [8]. Renewable energy is key to reaching this goal and bioenergy plays an important role. However, woody biomass is no longer supported as fuel for its primary use. Its use for energy production is the last option after other industrial purposes [9]; this encourages the search for other materials that have little industrial value. In addition, to avoid harming biodiversity or the environment, organic waste from various industries is considered an appropriate and sustainable fuel option.

Organic waste does not have to be produced and, ideally, should be used in the same area in which it is generated due to the lack of established supply chains, requiring specialized research to determine their energy viability. This is meant to avoid the expenditure of energy and money, and the generation of pollution that would be involved in the transportation of waste to distant places [10,11]. The challenges associated with utilizing these nonconventional biomasses often stem from their variable chemical composition, including high moisture content, which reduces heating value and facility efficiency, and, in the case of animal waste like poultry feedstock, high nitrogen content, leading to elevated nitrogen oxides emissions during combustion. Generally with all animal biomass, and especially with poultry, moisture is also one of the main issue to solve, as has been discussed in previous works, and drying becomes a fundamental part of the pretreatment of samples, ideally reducing their moisture content below 15% [12,13]. These are the reasons why this research focuses on nonconventional local biomasses. Other researchers have also focused on the study of waste as biomass, and they have mainly analyzed the proximate and ultimate analysis of fuels and other characteristics, such as higher heating values [1,14].

Notably, nonconventional biomasses can have very different compositions depending on their nature; this leads to a wide variety of ash compositions that can cause issues in boilers [15]. Ash-related problems, including alkali-induced slagging, ash fusion, agglomeration, and corrosion, are the main issues associated with different compositions of biomass [16,17,18,19]. The presence of compounds such as alkali metals results in the accumulation of deposits on the surfaces where combustion takes place. These deposits inhibit heat transfer and reduce facility efficiency [20].

These problems can be solved through different strategies including leaching, co-firing, and the addition of additives to fuels.

Leaching can remove ions that enhance the volatilization of problematic species, reducing the formation of their corresponding salts, and removes other inorganic species, such as sulfur and chlorine [21].

Co-firing consists of blending coal and biomass for combustion [6]. This can reduce emissions of NOx, SO2, and CO2. The alkali metals in biomass ash react with sulfur, reducing SO2 emissions [22], and the volatile matter composition of biomass can react with nitrogen oxides which reduces emissions [23]. CO2 is considered reduced as the next generation of biomass will absorb the gas as it grows.

Additives can fight ash-related issues via chemical reactions or physical adsorption. In the first case, additives react with low-melting-temperature ash components to increase their melting point [24], and in the second case, condensable vapor and ash fine particles are captured by porous additive particles [16]. Other means to fight ash problems with additives include enhancing ash melting temperatures by introducing more inert materials and elements, or diluting the ash and restraining ash melt formation and accumulation [25].

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) measures the mass loss rate of a sample when subjected to a controlled heating cycle in a specific atmosphere. With the same apparatus the heat flow produced by a chemical reaction can be measured by means of differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) and determine whether the reaction is endothermic or exothermic [26]. For combustion, there is a release of energy, but in other reactions, such as pyrolysis, energy must be apported because of their endothermic nature [27]. By means of these methods, many parameters, such as kinetic or combustion parameters, can be determined. For example, kinetic parameters include the activation energy or the preexponential factor of the reaction [28,29]. These data were already determined for some of the biomass used in this study using FWO, KAS, and Friedman methods. The conclusions of such study exposed the viability of the use of waste biomass and addressed the influence of additives in kinetic parameters, suggesting an a decrease in the activation energy and an easier combustion process [30]. This work aims to continue the investigation line through theoretical combustion parameters. The combustion parameters include the ignition and burnout temperatures, among others [26,31]. The determination of both types of parameters is crucial for designing biomass combustion facilities correctly.

This study focuses on determining the aforementioned ignition and burnout temperatures (Ti, Tb) and indices (Di, Db), the comprehensive combustibility index (S), the combustion index (Hf), and the flame stability index (Fi) for different biomasses. These data reveal the behavior of a fuel during combustion, indicating which type reacts first or which type burns faster. Thus, a database with information on different biofuels is a promising way to assess combustion performance and identify suitable energy sources

Other studies have analyzed the aforementioned parameters with other solid fuels, mainly with woody biomass, coal and blends of coal, and biomass, instead of fully waste biomass [32,33,34,35,36]. Unlike previous works focused predominantly on lignocellulosic materials, this research provides comparative insights into underutilized feedstocks with distinct biochemical compositions, thereby contributing to sustainable energy valorization pathways through waste-derived resources originating from the forestry, agricultural, and poultry industries. The inclusion of locally available waste materials highlights the feasibility of decentralized energy recovery systems that valorize regional biomass resources, reduce environmental burdens from waste disposal, and strengthen local circular economy initiatives. Overall, the findings contribute to identifying alternative biomass resources capable of supporting renewable energy generation in areas with limited access to conventional woody materials.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Sample Preparation

Biomass waste obtained from the local (Galicia-North Portugal Euroregion) forestry, agricultural, and poultry industries were used. Attending to their ubiquitous presence in this area, samples of kiwi pruning and gorse have been utilized to exemplify typical agricultural and forestry residues. These feedstocks were also blended with 2 wt. % kaolinite (kiwi N2 and gorse N2) and 2 wt. % CaCO3 (kiwi N3 and gorse N3).

The feedstocks were obtained in the form of pellets, which were subsequently ground and sieved in an IKA MF 10 mill (IKA, Barcelona, Spain) fitted with impact heads until the appropriate homogeneity for TGA was reached. The sieving process was performed using a 3 mm mesh sieve.

Ash and slagging problems are one of the main issues that have to be addressed when utilizing biomass as a thermal energy source. Potassium salts, usually in the form of chloride, sulfate, or carbonate, are among the most problematic ash-related substances. They have a low melting point even reaching volatilization temperatures during combustion. This causes condensation downstream over the surfaces of the boiler [37]. To avoid these problems, increasing the melting and volatilization points of these compounds is needed. Additives are used primarily to avoid or minimize particle emissions and can modify the melting temperature of the biomass ashes [38]. The existent literature shows that 2 wt. % of additives have the best results in alleviating such problems [39,40].

Kaolin, one such additive, is known for binding potassium in the form of potassium aluminum silicates [41]. Kaolinite is present in high amounts on kaolin, which is why it has been consistently used as an additive [42].

Calcium carbonate is another typical example of additive utilized in biomass combustion. Past research has shown that it causes a decrease in sulfur dioxide emissions, due to it biding sulfur from the gas phase at the typical temperatures at which the combustion reaction progresses (600–900 °C) [43]. In addition, it can increase the melting temperature of fuels with high content in phosphate. Phosphate salts encountered in biomass ash usually have melting temperatures below 700 °C [21,44].

As ash-related problems are mitigated with additives, it is important to understand whether these additives have further influence on the combustion reaction or if they solve only ash issues; this is why the blended samples were analyzed.

The animal biomasses used were poultry and turkey litter. These samples were blended with sawdust and straw, respectively. Unlike the plant biomass samples, the animal samples were not ground since their high humidity would not allow them to become fine dust suitable for thermogravimetric analysis. Nevertheless, the feedstock was composed of flakes small enough to fit inside the thermogravimetric scale crucible.

Commercial pine wood pellets were also evaluated to compare the results of the nonconventional biomass to those of traditional biomass.

Table 1 shows information about the ultimate analysis of the tested biomass and their calorific values [45]. The ultimate analysis was performed in a Fisions Carlo Erba EA1108 microanalyzer (Carlo Erba, Barcelona, Spain) from CACTI (Centre for Scientific and Technological Support to Research, University of Vigo) following the procedures dictated by ISO 16948 [46] and ISO 16994 [47]. Nonanimal biomasses (kiwi, gorse and their additivated samples) have similar contents of C, H, and O. Nitrogen is almost nonexistent in pine wood biomass and is more present in the other samples, especially in animal biomasses. Nitrogen can produce harmful compounds that should be avoided or reduced, such as NOx. The nitrogen contained in the fuel is a relevant source of NO emissions due to its release during combustion. Some authors have related the processes of NOx formation in biomass combustion to the NOx formation in coal combustion, concluding that, in cases of fuel with a very low percentage of nitrogen, approximately 70–100% of fuel nitrogen is converted to NO [48].

Table 1.

Fuel characteristics: ultimate analysis, heating values, and proximate analysis.

Proximate analysis was also carried out to determine the fractions of moisture, volatiles, fixed carbon, and ash in the samples. The moisture present in biomass determines the most adequate conversion technology. The high moisture content of fuels indicates that biological conversion methods are more suitable [49]. The amount of energy used to dry the biomass should not exceed the energy content of the fuel for combustion to be feasible. The volatile and fixed carbon contents determine when the fuel starts to burn, the duration of the reaction and the energy content of the biomass. Ash is the fraction that does not react. However, they can limit heat transfer due to resistance to oxygen diffusion, which causes an increase in the gradient between the interior and exterior of the fuel particles; this is due to the formation of fused ash remaining inside the fuel pores, limiting oxygen diffusion into the particles [50]. Oxygen diffusion plays an important role in the combustion process since it is responsible for the transport of oxygen to fuel particles, allowing the combustion reaction to occur [51].

The proximate analysis (Table 1) was performed in a SETARAM Labsys TGA/DTA-DSC apparatus (Setaram, Madrid, Spain), which has a measurement error of 0.5 mg. The samples were subjected to a thermal program where the biomass was first heated in a nonoxidative atmosphere and then completely oxidized. The method followed the procedures of ISO 18134-1:2015 [52], ISO 18123:2015 [53], and ISO 18122:2015 [54], where the moisture, volatile matter and ash contents were determined. Fixed carbon is calculated via Equation (1).

% Fixed carbon = 100 − (% Moisture + % Volatiles + % Ash),

Compared with the other samples, the animal biomass samples presented higher moisture and ash contents. However, they present a lower content of volatile matter. Nonconventional biomasses present a considerable quantity of ashes that can lead to ash-related problems.

Biomass ashes were also analyzed by means of a Siemens SRS3000 X-ray fluorescence (XRF) spectrometer (Siemens, Madrid, Spain) located in CACTI, and the data are shown in Table 2. The proportion of Si in the case of kaolinite and that of Ca in the case of CaCO3 increased for the additive samples. Animal biomass has an important proportion of problematic species, such as P, Cl, and K. During biomass combustion, due to the high volatility of some phosphorus compounds, P may be released as different P-oxides to the gas phase [55].

Table 2.

Ash ultimate analysis.

2.2. Thermogravimetric Study of the Samples

A SETARAM Labsys TGA/DTA-DSC thermobalance was used to carry out all the experiments with the nine biomasses. The mass of each sample was 10 ± 0.5 mg to minimize heat and mass transport limitations by establishing an intrinsic reaction regime. The samples were introduced in a 100-μL platinum crucible and then into the thermobalance, previously calibrated according to the instructions given by the supplier. The solid fuels were tested under an oxidizing atmosphere formed by 21% O2 and 79% N2 at a constant flow rate of 50 mL/min following the same procedure as in previous studies [56,57]. For each species three experiments were conducted, applying a constant heat rate of 10, 20 and 30 °C/min [58] from 20 °C to 900 °C.

A blank test was performed every few experiments by subjecting an empty crucible to the same heating cycle. This way a baseline can be established to be subtracted from the experiments eliminating the thermal buoyancy phenomenon and correcting any baseline issues that may affect the results [59].

Once all the tests were performed, the obtained data were postprocessed. A 0-degree Savitzky—Golay filter was used to smooth the data and reduce the noise of the experiments performed with minimal interference to the results [60].

2.3. Determination of the Combustion Characteristic Parameters

As mentioned before, the goal of this study is to provide a database of different biomasses to determine their combustion behavior and the effects of additives on this behavior; this can be accomplished by knowing their combustion parameters, which include Ti, Tb, Di, Db, S, Hf and Fi.

- Ignition and burnout temperatures

Ti provides information about when a sample of solid fuel starts to burn. It can be considered that the biomass starts to burn when its mass begins to decrease after losing its moisture [35]. If a fuel burns at a lower temperature than other fuels do, it means that the first one burns more easily [61]. A lower Ti results in energy savings in the facility since there is no need to apport high amounts of energy in the form of heat to start the combustion reaction.

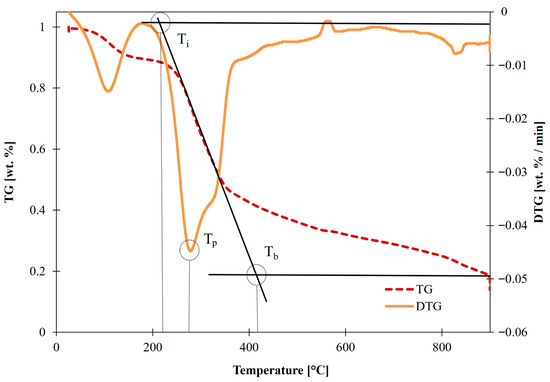

Tb corresponds to the point where the oxidation of the fuel is completed. To consider this, the mass loss rate of the sample must be near 0 wt. %/min [62]. There are many values at which Tb can be considered, but the general consensus in research is to use the tangent method, shown in Figure 1, to calculate both Ti and Tb [31,35,61,63].

Figure 1.

Tangent method.

- Ignition index

This parameter is related to the volatile matter content and provides information about how quickly and easily a solid fuel begins to burn [32]. Higher values of this parameter indicate an earlier start of volatile matter combustion and higher rates [26]; this is why fuels with higher values are considered to have better ignition characteristics [36,64]. To calculate Di of the different biomasses, Equation (2) was used [57,61,63,64,65]:

Di = DTGmax/(ti · tp) [(wt.%)/(min)3]

DTGmax represents the mass loss rate of the sample in . ti [min] corresponds to the time at which the fuel reaches Ti and starts to react. tp [min] is the time at which the sample has its maximum loss rate. Higher values of Di suggest lower Ti and faster conversion of matter. Lighter volatile matter reacts with higher mass loss rates, which decreases the temperature at which a fuel reaches its DTGmax and, thus, its tp.

- Burnout index

This parameter provides information about the final stage of the combustion process. It is inversely proportional to the speed at which the fixed carbon reacts. A lower value of the index means that fixed carbon reacts at lower temperatures and that the combustion process ends earlier [32]. This parameter is influenced by Di since it depends on the temperature range at which the volatile matter reacts.

Equation (3) was used to calculate Db [26,61,63,65]:

Db = DTGmax/(∆t1⁄2 · tp · tb) [(wt.%)/min4]

Δt1/2 corresponds to the time lapse where DTG/DTGmax = ½ from the descending part to the ascending part of the DTGmax peak [32].

- Comprehensive combustibility index.

This index reflects the ignition, combustion and burnout properties of a fuel [26], as well as the reactivity and intensity of the combustion reaction [58]. The values for this parameter were calculated via Equation (4) [26,36,56,58,64,65]:

S = (DTGmax ∙ DTGmean)/(Ti2 ∙ Tb) [(wt.%)/(min2·°C3)]

Solid fuels with higher S values have better combustion properties [35,66]. A high mass loss rate suggests that there is a high quantity of light compounds. A low Ti and Tb indicate that the fuel is more reactive, that the reaction ends earlier, and that it is easier to ignite. These are the reasons why higher values for this index suggest better combustion properties.

- Combustion index

This parameter reveals whether combustion starts earlier and with higher mass loss rates. A low value for this index indicates better combustion characteristics since the DTGmean indicates that most of the combustion has a high mass loss rate and that a lower value of ∆T1/2 indicates that volatile matter reacts with a low temperature variation. Equation (5) was used to calculate the values of Hf [26,29]:

Hf = Tp∙ln (∆T1/2/DTGmean) [°C2·min]

The intensity of combustion is intimately related to a high mass loss rate and a low temperature to its maximum value. ∆T1/2 is the range of temperatures that correspond to Δt1/2, which indicates that the reaction is fast if its value is low.

- Flame stability index

This index is used to determine how stable the combustion reaction of the solid fuel is. Stable combustion is characterized by a high value of this index, which is described as a high mass loss rate and low Ti and Tb [56]. This parameter was calculated with Equation (6) [32,65]:

Fi = DTGmax/(Ti ∙(Tb − Ti)) [(wt.%)/(min·°C2)]

All these parameters provide enough information to theoretically characterize different fuels. These parameters are important since they give us the Ti, how fast the biomass reacts, the reactivity or if the combustion process will take longer as a function of the Db. All these data help to design and model facilities efficiently or, depending on whether the facility is already built or not, how suitable the fuel is for it.

Other parameters exist, including the volatile matter index, which reflects the release performance of volatile matter in a fuel [32], or burnout efficiency, which indicates the burnout efficiency by means of ash content [67].

However, it was concluded that these parameters were close enough to the chosen ones for this study to consider that they bring any new or more relevant information. Ti and Tb, Di and Db, Hf, S, and Fi are the combustion parameters that provide more valuable information about the studied biomass fuels.

3. Results and Discussion

The results for the fuels considered are represented and explained through TGA and differential thermogravimetric curves. The information extracted from these experiments was used to calculate the results of the combustion parameters.

3.1. TGA

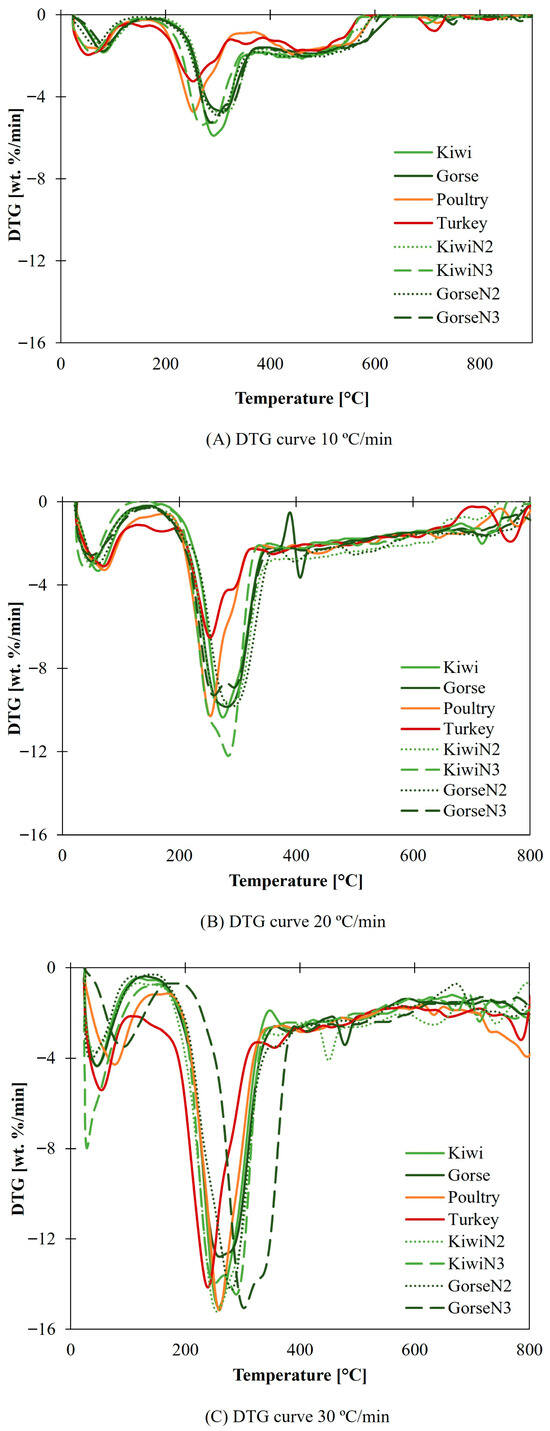

In Figure 2, a comparison between animal-derived biomass and nonanimal-derived biomass at each heating rate is shown. The first DTG peak corresponds to moisture loss, which is more noticeable in animal-derived biomass in most cases; this is due to the higher moisture content in this type of biomass according to the proximate analysis.

Figure 2.

(A) DTG curve for 10 °C/min. (B) DTG curve for 20 °C/min. (C) DTG curve for 30 °C/min.

DTGmax is reached faster in animal biomass. Even though they do not have more volatile matter content, some alkali species present in the ash can produce catalytic effects in the reaction [68].

There is also an increase in the DTGmax value at higher heating rates. The volatile matter reaction present in animal biomass seems to be favored by these materials, because at 10 °C/min (Figure 2A) they do present lower values of DTGmax than nonanimal biomass does. At 20 °C/min (Figure 2B) poultry grows above kiwi and gorse. At 30 °C/min (Figure 2C) both poultry and turkey have higher values than nonanimal biomass.

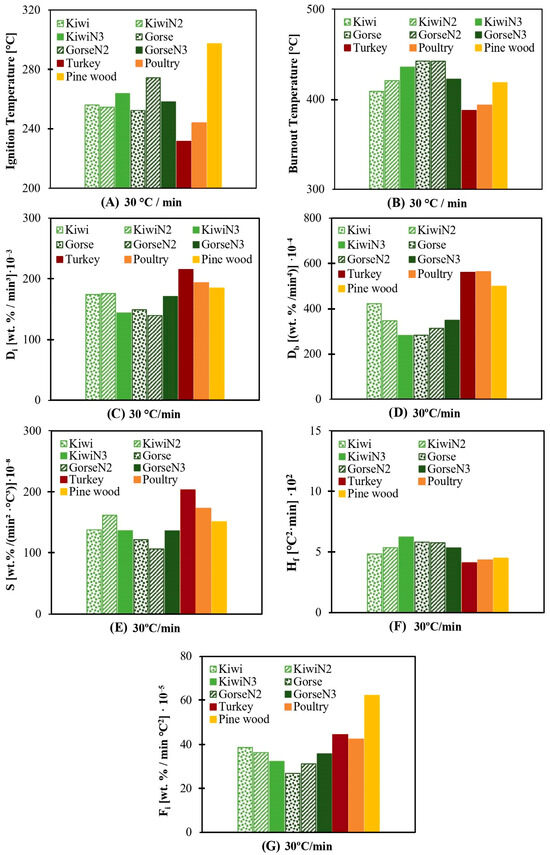

The results for 30 °C/min are shown only (Figure 3) since this heating rate is the closest to real heating rate facilities and since no relevant differences between each heating rate tested are apparent. The complete results and information are included in the Supplementary Material in the online version of the paper. This decision is made for simplicity and to facilitate explanations.

Figure 3.

(A) Ti for 30 °C/min. (B) Tb for 30 °C/min. (C) Di for 30 °C/min. (D) Db for 30 °C/min. (E) S for 30 °C/min. (F) Hf for 30 °C/min. (G) Fi for 30 °C/min.

3.2. Ignition and Burnout Temperatures

At all heating rates, nonanimal biomasses start burning later than animal biomasses (Figure 3A). The difference between their mean temperatures is approximately 16–17 °C at every heating rate. Even though kiwi and gorse have more volatile matter content, which would mean that they should have a lower Ti. This is not observed in the results; this could be explained, as mentioned in Section 3.1, through the nature of the ash composition.

The Tb values are shown in Figure 3B, in which there is no pattern followed by neither nonanimal biomasses nor animal biomasses, so conclusions cannot be drawn.

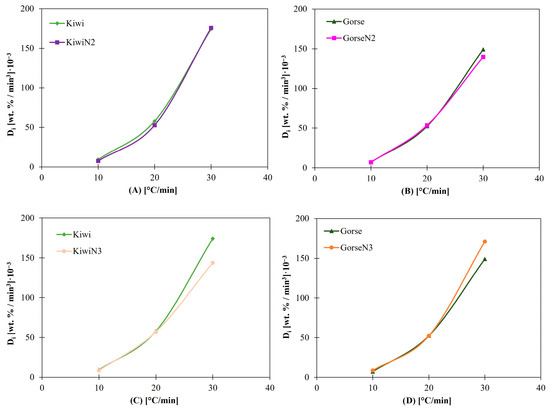

3.3. Ignition and Burnout Indices

Kaolinite, at a 2 wt.% concentration, had no effect on the index results for kiwi and gorse (Figure 4A,B). The Di results for each heating rate show almost no difference compared with the results of kiwi and gorse without additives. The same phenomenon occurs with Db. Considering that the reason for using additives relies on reducing ash-related problems by changing the composition of the ashes [21], having no impact on the Di values demonstrates that 2 wt.% kaolinite does not take part in the biomass reaction at those temperatures.

Figure 4.

(A) Di for Kiwi and Kiwi N2. (B) Di for Gorse and Gorse N2. (C) Di for kiwi and Kiwi N3. (D) Di for Gorse and Gorse N3.

With CaCO3, the same phenomenon was observed at heating rates of 10 and 20 °C/min (Figure 4C,D). However, the results start to differ more at 30 °C/min; this suggests that 2 wt.% CaCO3 starts to influence Di at 30 °C/min, and the difference between values might increase at higher heating rates, which could be due to secondary reactions that affect the temperature at which the biomass fuel starts to burn, depending on its composition.

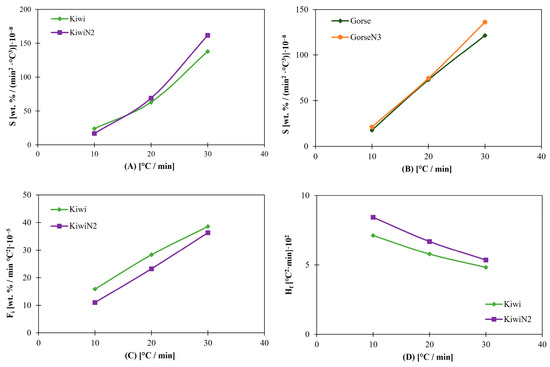

3.4. Comprehensive Combustibility Index, Flame Stability Index and Combustion Index

In the case of Figure 5A,B for S, both the N2 and N3 additivated biomasses followed the same pattern as the previous indices. Additives have a low impact on ignition, combustion, and burnout properties, such as on the reactivity and intensity of combustion. In other words, combustion properties seem to remain almost the same at the same time that ash-related problems are reduced.

Figure 5.

(A) S for Kiwi and Kiwi N2. (B) S for Gorse and Gorse N3. (C) Fi for Kiwi and Kiwi N2. (D) Hf for Kiwi and Kiwi N2.

Nonetheless, they start to differ at 30 °C/min due to the small impact of additives on Ti and Tb. With increasing heating rates, this behavior intensifies.

For the Fi and the Hf, kiwi without kaolinite has better parameters than the additivated sample, as can be observed in Figure 5C,D; this is due to its higher volatile content, which results in the loss of mass at higher rates and at lower temperatures, as reflected in the DTGmax, DTGmean, and Tp values. The same pattern is observed between kiwi and kiwi N3 for the same reason as kiwi N2.

For gorse, the results are similar with and without additives, which is due to the similar composition of them in the proximate analysis (Table 1).

3.5. Influence of Additives

The 2 wt.% additive concentration had no relevant effect on the combustion parameters of gorse and kiwi at relatively low heating rates. Additives have the goal of reacting with ash components to reduce ash-related problems mentioned in Section 2.1. Even though they modify the composition of the fuel, they do not affect the general behavior of combustion, at least at low heating rates. However, the results start to differ in some cases at higher heating rates, such as Di, where the value for kiwi is 174.32 (wt. %/min3) × 10−3 and that for kiwiN3 is 143.78 (wt. %/min3) × 10−3, which can be aggravated in facilities that might use higher rates. The difference can also be observed for gorse with a Di value of 149.09 (wt. %/min3) × 10−3 and for gorse N3 with a Di value of 171.11 (wt. %/min3) × 10−3.

A comparison of the results of each sample of kiwi revealed that kiwi without additives presented better combustion behavior than did the other samples since it started burning earlier and at a faster rate, as indicated by its Ti and Di values; in addition, its Db value demonstrates that the oxidation of fixed carbon finishes at lower temperatures. The combustion and flame stability indices also present better values for kiwi since there is a reduction of 10–25% between the values of non-additivated and additivated kiwi for the combustion index and an increase of 6–30% for the Fi.

In the case of gorse, the results are nonconclusive. These values are so similar that it is impossible to determine which sample has the best behavior during the combustion process.

Even though small differences can be observed between additivated and non-additivated fuels, their variations are not relevant enough to take them into account when choosing a fuel for industrial use, for example.

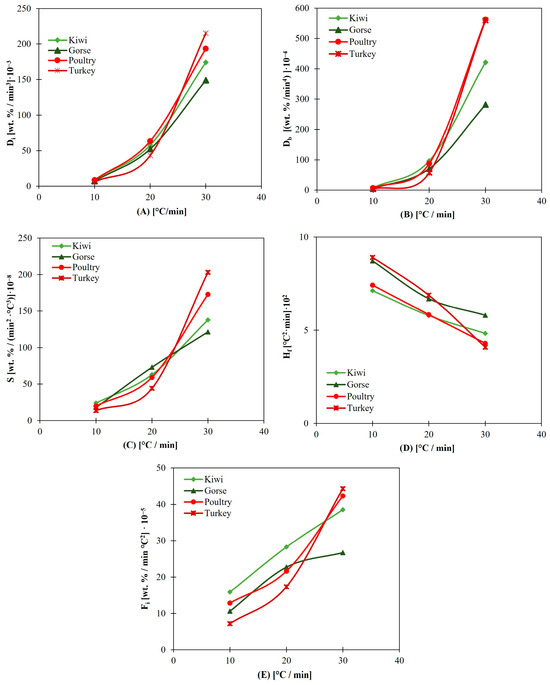

3.6. Combustion Parameters for Animal Biomasses Compared with Those for Nonanimal Samples

In every case, turkey and poultry have better parameters at a heating rate of 30 °C/min, as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

(A) Di for animal and nonanimal biomass without additives. (B) Db for animal and nonanimal biomass without additives. (C) S for animal and nonanimal biomass without additives. (D) Hf for animal and nonanimal biomass without additives. (E) Fi for animal and nonanimal biomass without additives.

The mass loss rate for these fuels seems to increase with higher heating rates. These findings suggest that these animal biomasses, especially those with relatively high heating rates, would have improved behavior in real facilities. Low heating rates are used in this study because at high heating rates, Ti and the combustion process generally start at higher temperatures, and the mass loss rate also increases [69]. This delay in Ti is due to the reduced residence time at higher heating rates, and it has been studied by different researchers finding that it is due to the combined effects of changes in decomposition temperature at different heating rates and the kinetics of decomposition [69]. This effect has been observed in different biomasses [70].

However, as can be observed in Table 1 and Table 2, poultry and turkey samples have more ashes, and their composition includes many species that cause ash-related problems [21]. Turkey and poultry present high contents of P, Cl and K in their ash, which are some of the most problematic species related to ash problems. They also present between 17 and 28% P in their ashes, whereas 1–8% P is present in the rest of the fuels tested. The same is true for the Cl and K contents. The contents of problematic species in biofuels likely lead to slagging, ash fusion, agglomeration, and corrosion. Therefore, it would be interesting to study the scope of ash-related problems with these animal-derived fuels and which additives would palliate them. Additionally, the high moisture content of animal biomass must be considered since it is more difficult to burn in real facilities, and that impact is not well reflected in TGA.

According to the previous analysis, animal biomasses present more favorable values of combustion parameters at higher heating rates. Even though these parameters strongly depend on volatile matter and these fuels do not have a higher content than nonanimal biomasses do, the nature of volatile matter seems to have an important impact on the values of the studied indices since they are highly dependent on when the sample starts to burn, the mass loss rate and at which temperature and how quickly it reaches its DTGmax. All these data are directly related to the volatile content and how it interacts with the temperatures and species found in the biomass composition.

Finally, this work has successfully determined the combustion parameters of the fuels, thereby providing a valuable tool for exploring the initial viability of local waste-derived biomasses, in this case those sourced from the Galicia–North Portugal region. This achievement can be applied to any potential solid biofuel which enhances the waste valorization.

4. Conclusions

The study of combustion parameters by means of TGA provides valuable preliminary insights into how different biomasses behave during combustion. This approach allows the identification of key thermal events that define their suitability for energy conversion processes.

Furthermore, the investigation of nonconventional biomasses represents an effective strategy to valorize materials that would otherwise remain as unused residues. A deeper understanding of their combustion behavior, potential reaction-related challenges, and mitigation strategies not only expand scientific knowledge on these heterogeneous feedstocks but also supports the development of pre-treatment methods aimed at cleaner and more efficient energy generation. Specifically, the study revealed that animal-derived fuels exhibit theoretically better combustion behavior, with a mean Ti approximately 16–17 °C lower than tested nonanimal biomass. However, these fuels present challenges due to their high problematic ash content rich in P, Cl, and K. The investigation into mitigation strategies showed that while necessary, additives had little impact on parameters at lower heating rates. They only began to modify the combustion parameters behavior at 30 °C/min, as is the case for Di for kiwi, which varied from 174.32 × 10−3 (wt.%/ min3) to 143.78 × 10−3 (wt.%/min3) with CaCO3.

Such developments are a crucial step for decarbonization efforts and for advancing towards sustainable development by promoting decentralized energy production, providing alternatives for waste disposal and management, favoring local circular economy projects and reducing dependence on nonrenewable energy sources.

Finally, the data generated in this study can contribute to establishing a comprehensive database of nonconventional fuels that facilitates informed decision-making in regional energy planning and environmental policy design.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su172210426/s1, Table S1: Samples tested by TGA; Table S2: Oxides contained in ash fraction calculated form XRF analysis; Table S3: Ignition and burnout temperatures; Table S4: Ignition index; Table S5: Burnout index; Table S6: Comprehensive combustibility index; Table S7: Combustion index; Table S8: Flame stability index; Table S9: Standard deviations; Figure S1: (A) Ignition temperature for 10 °C /min. (B) Ignition temperature for 20 °C /min; Figure S2: (A) Burnout temperature for 10 °C /min. (B) Burnout temperature for 20 °C /min; Figure S3: (A) Ignition index for 10 °C /min. (B) Ignition for 20 °C /min; Figure S4: (A) Burnout index for 10 °C /min. (B) Burnout for 20 °C /min; Figure S5: (A) Comprehensive combustibility index for 10 °C /min. (B) Comprehensive combustibility index for 20 °C /min; Figure S6: (A) Combustion index for 10 °C /min. (B) Combustion index for 20 °C /min; Figure S7: (A) Flame stability index for 10 °C /min. (B) Flame stability for 20 °C /min.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.J.R. and R.P.-O.; methodology, A.F.-S.; software, A.F.-S. and J.J.R.; validation, J.J.R.; formal analysis, A.F.-S.; investigation, A.F.-S.; resources, D.P.; data curation, A.F.-S. and J.J.R.; writing—original draft preparation, A.F.-S.; writing—review and editing, J.J.R., R.P.-O. and D.P.; visualization, J.J.R., R.P.-O. and D.P.; supervision, D.P.; project administration, D.P.; funding acquisition, D.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was financially supported by the project PID2021-126569OB-I00 of the Ministry of Science and Innovation (Spain) and the AVIENERGY project, jointly financed by the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development (EAFRD) at 80% and by the Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca y Alimentación at 20%.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available in Mendeley Data at Franco, Amanda; Rico, Juan Jesús; Pérez-Orozco, Raquel; Patiño Vilas, David (2025), “Biomass combustion parameters dataset”, Mendeley Data, V2, https://doi.org/10.17632/7xhs9h3xs5.2 [71].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Db | Burnout index |

| Di | Ignition index |

| DSC | Differential scanning calorimetry |

| DTA | Differential thermal analysis |

| DTG | Mass loss rate |

| DTGmax | Maximum mass loss rate |

| DTGmean | Average mass loss rate |

| Fi | Flame stability index |

| Gorse N2 | Gorse pellet blended with 2 wt. % kaolinite |

| Gorse N3 | Gorse pellet blended with 2 wt. % CaCO3 |

| Hf | Combustion index |

| Kiwi N2 | Kiwi pellet blended with 2 wt. % kaolinite |

| Kiwi N3 | Kiwi pellet blended with 2 wt. % CaCO3 |

| S | Comprehensive combustibility index |

| Ti | Ignition temperature |

| ti | Ignition time |

| Tb | Burnout temperature |

| TGA | Thermogravimetric analysis |

| tp | Peak time |

References

- García, R.; Pizarro, C.; Lavín, A.G.; Bueno, J.L. Characterization of Spanish biomass wastes for energy use. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 103, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vertès, A.; Qureshi, N.; Blaschek, H.; Yukawa, H. Green Energy to Sustainability; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Primary Energy Consumption by Source. Our World in Data. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/global-energy-substitution (accessed on 20 March 2023).

- Hosseini, S.E.; Wahid, M.A. Hydrogen production from renewable and sustainable energy resources: Promising green energy carrier for clean development. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 57, 850–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose, B.K. Global Warming: Energy, Environmental Pollution, and the Impact of Power Electronics. IEEE Ind. Electron. Mag. 2010, 4, 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosillo Callé, F. (Ed.) The Biomass Assessment Handbook: Bioenergy for a Sustainable Environment; Earthscan: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, D.; Sun, J.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, Z.; Wang, X.; Zi, J.; Stojiljković, D.; Manić, N.; Tan, H.; Rahman, Z.U.; et al. Evaluation of ash/slag heavy metal characteristics and potassium recovery of four biomass boilers. Biomass Bioenergy 2023, 173, 106770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fit for 55. Consejo Europeo. 10 October 2023. Available online: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/es/policies/green-deal/fit-for-55-the-eu-plan-for-a-green-transition/ (accessed on 13 November 2023).

- Directive (EU) 2023/2413 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 18 October 2023 Amending Directive (EU) 2018/2001, Regulation (EU) 2018/1999 and Directive 98/70/EC as Regards the Promotion of Energy from Renewable Sources, and Repealing Council Directive (EU) 2015/652. 2023. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/2023/2413/oj (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Hatamleh, R.I.; Jamhawi, M.M.; Al-Kofahi, S.D.; Hijazi, H. The Use of a GIS System as a Decision Support Tool for Municipal Solid Waste Management Planning: The Case Study of Al Nuzha District, Irbid, Jordan. Procedia Manuf. 2020, 44, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madden, B.; Florin, N.; Mohr, S.; Giurco, D. Estimating emissions from household organic waste collection and transportation: The case of Sydney and surrounding areas, Australia. Clean. Waste Syst. 2022, 2, 100013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Holanda Pasolini, V.; Lima, R.M.; Costa, A.B.S.; de Sousa, R.C. Drying of poultry manure for biomass applications in the combustion. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2024, 14, 17543–17553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wzorek, M.; Junga, R.; Yilmaz, E.; Niemiec, P. Combustion behavior and mechanical properties of pellets derived from blends of animal manure and lignocellulosic biomass. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 290, 112487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, R.K.; Mohanty, K. Pyrolysis kinetics and thermal behavior of waste sawdust biomass using thermogravimetric analysis. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 251, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Royo, J.; Canalís, P.; Quintana, D. Ash partitioning in combustion of pelletized residual agricultural biomass. Biomass Bioenergy 2025, 193, 107563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dula, M.; Kraszkiewicz, A. A review: Problems related to ash deposition and deposit formation in low-power biomass-burning heating devices. Front. Energy Res. 2025, 13, 1652415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaniowski, W.; Taler, J.; Wang, X.; Kalemba-Rec, I.; Gajek, M.; Mlonka-Mędrala, A.; Nowak-Woźny, D.; Magdziarz, A. Investigation of biomass, RDF and coal ash-related problems: Impact on metallic heat exchanger surfaces of boilers. Fuel 2022, 326, 125122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hariana; Putra, H.P.; Prabowo; Hilmawan, E.; Darmawan, A.; Mochida, K.; Aziz, M. Theoretical and experimental investigation of ash-related problems during coal co-firing with different types of biomass in a pulverized coal-fired boiler. Energy 2023, 269, 126784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abioye, K.J.; Harun, N.Y.; Sufian, S.; Yusuf, M.; Jagaba, A.H.; Ekeoma, B.C.; Kamyab, H.; Sikiru, S.; Waqas, S.; Ibrahim, H. A review of biomass ash related problems: Mechanism, solution, and outlook. J. Energy Inst. 2024, 112, 101490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Niu, Y.; Tan, H.; Wang, D.; Du, W.; Hui, S. A New Agro/Forestry Residues Co-Firing Model in a Large Pulverized Coal Furnace: Technical and Economic Assessments. Energies 2013, 6, 4377–4393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y.; Tan, H.; Hui, S. Ash-related issues during biomass combustion: Alkali-induced slagging, silicate melt-induced slagging (ash fusion), agglomeration, corrosion, ash utilization, and related countermeasures. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2016, 52, 1–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandberg, J.; Karlsson, C.; Fdhila, R.B. A 7year long measurement period investigating the correlation of corrosion, deposit and fuel in a biomass fired circulated fluidized bed boiler. Appl. Energy 2011, 88, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; McIlveen-Wright, D.; Rezvani, S.; Wang, Y.D.; Hewitt, N.; Williams, B.C. Biomass co-firing in a pressurized fluidized bed combustion (PFBC) combined cycle power plant: A techno-environmental assessment based on computational simulations. Fuel Process. Technol. 2006, 87, 927–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hariana, H.; Ghazidin, H.; Darmawan, A.; Hilmawan, E.; Prabowo; Aziz, M. Effect of additives in increasing ash fusion temperature during co-firing of coal and palm oil waste biomass. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2023, 23, 101531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Hustad, J.E.; Skreiberg, Ø.; Skjevrak, G.; Grønli, M. A Critical Review on Additives to Reduce Ash Related Operation Problems in Biomass Combustion Applications. Energy Procedia 2012, 20, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mureddu, M.; Dessì, F.; Orsini, A.; Ferrara, F.; Pettinau, A. Air- and oxygen-blown characterization of coal and biomass by thermogravimetric analysis. Fuel 2018, 212, 626–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Yan, R.; Chen, H.; Lee, D.H.; Zheng, C. Characteristics of hemicellulose, cellulose and lignin pyrolysis. Fuel 2007, 86, 1781–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irfan Khan, M.; Khan, H.U.; Azizli, K.; Sufian, S.; Man, Z.; Siyal, A.A.; Muhammad, N.; Faiz ur Rehman, M. The pyrolysis kinetics of the conversion of Malaysian kaolin to metakaolin. Appl. Clay Sci. 2017, 146, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, S.L.; Lu, C.M.; Han, K.H.; Zhao, J.L. Thermogravimetric analysis of combustion characteristics and kinetic parameters of pulverized coals in oxy-fuel atmosphere. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2009, 98, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rico, J.J.; Pérez-Orozco, R.; Patiño Vilas, D.; Porteiro, J. TG/DSC and kinetic parametrization of the combustion of agricultural and forestry residues. Biomass Bioenergy 2022, 162, 106485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, S.; Choi, G.; Kim, D. The effect of wood biomass blending with pulverized coal on combustion characteristics under oxy-fuel condition. Biomass Bioenergy 2014, 71, 144–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Chen, M.; Wei, Y.; Niu, S.; Xue, F. An assessment on co-combustion characteristics of Chinese lignite and eucalyptus bark with TG–MS technique. Powder Technol. 2016, 294, 463–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, S.; Han, K.; Lu, C. Characteristic of coal combustion in oxygen/carbon dioxide atmosphere and nitric oxide release during this process. Energy Convers. Manag. 2011, 52, 532–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Zhang, K.; Cao, Y.; Pan, W. Co-combustion characteristics and blending optimization of tobacco stem and high-sulfur bituminous coal based on thermogravimetric and mass spectrometry analyses. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 131, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Xie, C.; Guo, X.; Qin, Z.; Lin, J.-Y.; Li, Z. Combustion Characteristics of Coal Gangue under an Atmosphere of Coal Mine Methane. Energy Fuels 2014, 28, 3688–3695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Hu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Cheng, X. Experimental investigation on ignition and burnout characteristics of semi-coke and bituminous coal blends. J. Energy Inst. 2020, 93, 1373–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Li, J.; Lin, L.; Zhang, X. Release of potassium in association with structural evolution during biomass combustion. Fuel 2021, 287, 119524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuptz, D.; Kuchler, C.; Rist, E.; Eickenscheidt, T.; Mack, R.; Schön, C.; Drösler, M.; Hartmann, H. Combustion behaviour and slagging tendencies of pure, blended and kaolin additivated biomass pellets from fen paludicultures in two small-scale boilers < 30 kW. Biomass Bioenergy 2022, 164, 106532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragutinovic, N.; Höfer, I.; Kaltschmitt, M. Effect of additives on thermochemical conversion of solid biofuel blends from wheat straw, corn stover, and corn cob. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2019, 9, 35–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, V.E.M.; Kaltschmitt, M. Effect of straw proportion and Ca- and Al-containing additives on ash composition and sintering of wood–straw pellets. Fuel 2013, 109, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemi, H.; Wang, G.; Jensen, P.A.; Wu, H.; Frandsen, F.J.; Sander, B.; Glarborg, P. Modeling Potassium Capture by Aluminosilicate, Part 1: Kaolin. Energy Fuels 2021, 35, 13984–13998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öhman, M.; Boström, D.; Nordin, A.; Hedman, H. Effect of Kaolin and Limestone Addition on Slag Formation during Combustion of Wood Fuels. Energy Fuels 2004, 18, 1370–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacharczuk, W.; Andruszkiewicz, A.; Tatarek, A.; Alahmer, A.; Alsaqoor, S. Effect of Ca-based additives on the capture of SO2 during combustion of pulverized lignite. Energy 2021, 231, 120988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenari, B.-M.; Lundberg, A.; Pettersson, H.; Wilewska-Bien, M.; Andersson, D. Investigation of Ash Sintering during Combustion of Agricultural Residues and the Effect of Additives. Energy Fuels 2009, 23, 5655–5662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patiño Vilas, D. Análisis Experimental de Combustión de Biomasa en un Quemador de Lecho fijo. Universidade de Vigo. 2009. Available online: https://portalcientifico.uvigo.gal/documentos/5c13b1b9c8914b6ed37773e4?lang=es (accessed on 27 February 2025).

- ISO 16948; Solid Biofuels—Determination of Total Content of Carbon, Hydrogen and Nitrogen. AENOR: Madrid, Spain, 2015.

- ISO 16994; Solid Biofuels—Determination of Total Content of Sulfur and Chlorine. AENOR: Madrid, Spain, 2016.

- Vermeulen, I.; Block, C.; Vandecasteele, C. Estimation of fuel-nitrogen oxide emissions from the element composition of the solid or waste fuel. Fuel 2012, 94, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKendry, P. Energy production from biomass (part 1): Overview of biomass. Bioresour. Technol. 2002, 83, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zhai, M.; Jin, S.; Zou, X.; Liu, S.; Dong, P. Numerical simulation of high-temperature fusion combustion characteristics for a single biomass particle. Fuel Process. Technol. 2019, 183, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alekseenko, S.V.; Butakov, E.B.; Chikishev, L.M.; Sharaborin, D.K. Experimental study of diffusion combustion of a fine pulverized coal in a CH4–N2 gas jet. J. Appl. Mech. Tech. Phys. 2020, 61, 757–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 18134-1:2015; Solid Biofuels—Determination of Moiture Content—Oven dry Method—Part 1: Total Moisture—Reference Method. AENOR: Madrid, Spain, 2015.

- ISO 18123:2015; Solid Biofuels—Determination of the Content of Volatile Matter. AENOR: Madrid, Spain, 2015.

- ISO 18122:2015; Solid Biofuels—Determination of Ash Content. AENOR: Madrid, Spain, 2015.

- Boström, D.; Skoglund, N.; Grimm, A.; Boman, C.; Öhman, M.; Broström, M.; Backman, R. Ash transformation chemistry during combustion of biomass. Energy Fuels 2012, 26, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, Z.; Song, Z.; Bi, H.; Jiang, C.; Sun, H.; Qiu, Z.; He, L.; Lin, Q. The effect of cellulose on the combustion characteristics of coal slime: TG-FTIR, principal component analysis, and 2D-COS. Fuel 2023, 333, 126310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayaraman, K.; Kok, M.V.; Gokalp, I. Thermogravimetric and mass spectrometric (TG-MS) analysis and kinetics of coal-biomass blends. Renew. Energy 2017, 101, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Cao, X.; Duan, X.; Wang, Y.; Che, D. Thermal analysis on combustion characteristics of predried dyeing sludge. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2018, 140, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadatkhah, N.; Carillo Garcia, A.; Ackermann, S.; Leclerc, P.; Latifi, M.; Samih, S.; Patience, G.S.; Chaouki, J. Experimental methods in chemical engineering: Thermogravimetric analysis—TGA. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 2020, 98, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savitky, A.; Golay, M. Smoothing and Differentiation of Data by Simplified Least Squares Procedures. 2002. Available online: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/epdf/10.1021/ac60214a047 (accessed on 19 September 2023).

- Yang, Z.; Zhang, S.; Liu, L.; Li, X.; Chen, H.; Yang, H.; Wang, X. Combustion behaviours of tobacco stem in a thermogravimetric analyser and a pilot-scale fluidized bed reactor. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 110, 595–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Zhong, Z. Experimental studies on combustion of composite biomass pellets in fluidized bed. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 599, 926–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.G.; Lv, Y.; Ma, B.G.; Jian, S.W.; Tan, H.B. Thermogravimetric investigation on co-combustion characteristics of tobacco residue and high-ash anthracite coal. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 9783–9787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayaraman, K.; Kök, M.V.; Gökalp, I. Combustion mechanism and model free kinetics of different origin coal samples: Thermal analysis approach. Energy 2020, 204, 117905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wang, Y.; Lang, X.; Ren, X.; Fan, S. Comparative evaluation of thermal oxidative decomposition for oil-plant residues via thermogravimetric analysis: Thermal conversion characteristics, kinetics, and thermodynamics. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 243, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Chen, M.; Yu, D. Oxygen enriched co-combustion characteristics of herbaceous biomass and bituminous coal. Thermochim. Acta 2013, 569, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, S.; Choudhury, N.; Sarkar, P.; Mukherjee, A.; Sahu, S.G.; Boral, P.; Choudhury, A. Studies on the combustion behaviour of blends of Indian coals by TGA and Drop Tube Furnace. Fuel Process. Technol. 2006, 87, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nzihou, A.; Stanmore, B. The fate of heavy metals during combustion and gasification of contaminated biomass—A brief review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2013, 256, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vamvuka, D.; Sfakiotakis, S. Combustion behaviour of biomass fuels and their blends with lignite. Thermochim. Acta 2011, 526, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, T.; Murugan, P.; Abedi, J.; Mahinpey, N. Pyrolysis of wheat straw in a thermogravimetric analyzer: Effect of particle size and heating rate on devolatilization and estimation of global kinetics. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2010, 88, 952–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, A.; Rico, J.J.; Pérez-Orozco, R.; Patiño Vilas, D. Biomass combustion parameters dataset. Mendeley Data 2025, V2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).