Abstract

Drawing on a comprehensive sample of China’s A-share listed companies spanning 2007–2022, this paper provides empirical evidence on how institutional investment horizons shape corporate green innovation, with special attention to the operative mechanisms. After implementing standard data screening protocols, the resulting dataset comprising 24,362 firm-year observations is examined through panel regression techniques. The results demonstrate that longer investment horizons of institutional investors significantly promote corporate green innovation. Our mechanism analysis indicates that environmental regulations and subsidy policies significantly moderate the relationship between institutional investors’ investment horizons and green innovation. These findings provide both a novel theoretical perspective and robust empirical evidence on the determinants of corporate green innovation, and yield valuable policy insights for leveraging capital markets to facilitate the corporate transition to sustainability. It also provides specific references for policymakers to facilitate corporate green transformation and support the dual-carbon goals by guiding and incentivizing greater influence exerted by long-term institutional investors through corporate governance mechanisms.

1. Introduction

Since the 21st century, human development has been constrained by greenhouse gas emissions and environmental pollution, making the reconciliation of economic and environmental objectives a universal concern for nations worldwide. Against this backdrop, China has proposed the strategic goals of “achieving carbon peaking before 2030 and carbon neutrality before 2060”, elevating green transition to a national strategic height in the overall national development agenda. Aiming to fulfill the dual-carbon goal proposed in September 2020, the Chinese government launched the “14th Five-Year Plan for Energy Conservation and Emission Reduction” in December 2021, with targets for 2025 that include a 13.5 percent reduction was achieved in energy intensity against the 2020 baseline, rational control of total energy consumption, and substantial emission reductions of no less than 8%, 8%, 10%, and 10% for COD, ammonia nitrogen, NOx, and VOCs, respectively. Green innovation is considered key to promoting corporate green transformation and alleviating environmental issues, and its importance in achieving the dual-carbon target has been widely recognized in both industry and academia. Enterprises, as the primary entities responsible for pollutant emissions and energy consumption, possess green innovation capabilities that directly determine the achievement of the “dual carbon” goals. Green innovation is widely recognized as the key pathway to resolving the conflict between economic growth and environmental protection. Given the high investment, high risk, and dual externalities inherent to green innovation [1,2], companies find it challenging to reach the optimal investment level through their own efforts. Investigating the determinants of corporate green innovation is instrumental for informing policies aimed at realizing the “dual-carbon” vision and guiding corporate green transformation.

Institutional investors, including various securities intermediaries, securities investment funds (investment companies), pension funds, insurance companies, etc., are professional investment entities, fulfilling a monitoring function in corporate governance by applying their professional competence and informational edge [3,4]. As professional external governance entities in capital markets, institutional investors have been proven to significantly influence corporate social responsibility fulfillment and ESG performance enhancement by virtue of their information advantages and monitoring capabilities. Academic literature consistently acknowledges how institutional investors shape firms’ ecological governance, demonstrating pronounced sensitivity to sustainability reporting, ESG outcomes, and environmental compliance incidents [5,6]. As key participants in the financial ecosystem, institutional investors are pivotal in advancing corporate green investment and innovation [7,8]. Research has identified institutional investors as significant drivers of corporate green innovation, with studies examining dimensions including ownership stake [9], portfolio characteristics [10], co-institutional investors [11,12], green institutional investors [13], geographical location of institutional investors [14], and foreign institutional investors [15]. Although the positive contributions of institutional investors are supported by an extensive literature, there is substantial heterogeneity in the impact across different types of institutions [16]. A key criterion to differentiate among institutional investor types is their investment horizon. The temporal orientation of institutional investors serves as a governance tool that fosters managerial alignment with enduring corporate objectives, thereby mitigating short-termism [17,18]. However, existing literature has yet to systematically elucidate how institutional investors’ investment horizons affect corporate green innovation, nor has it clarified the moderating mechanisms of government environmental policies (regulations and subsidies) in this process. The key factor of institutional investors’ governance role is their investment horizon rather than others. Therefore, studying the role of institutional investors’ investment horizon in green innovation is particularly significant, and this paper’s research fills this research gap. Meanwhile, as crucial tools for addressing market failures in green innovation, the effectiveness of government environmental policies is closely tied to the characteristics of market governance entities. Existing research presents divergent perspectives on the relationship between environmental regulation and green innovation. Early viewpoints held that environmental regulation increases corporate compliance costs, thereby “crowding out” green innovation investments [19]. Recent studies, however, propose an “innovation offset effect,” suggesting that stringent regulations can compel enterprises to enhance efficiency through green innovation [20]. Similarly, while environmental subsidies can alleviate financial constraints on corporate green innovation [21], some research indicates that subsidized funds might be misappropriated, diminishing policy effectiveness [22]. The root of these controversies lies in the fact that most existing studies examine policy effects in isolation, without analyzing the interaction mechanisms between policies and market governance in conjunction with the heterogeneity of institutional investors (particularly investment horizons). This directly impacts the synergistic optimization of environmental policies and capital market governance, yet remains insufficiently explored.

Based on this foundation, the current study centers on answering the following research questions: (1) This study pioneers the incorporation of “investment horizon” as a core dimension into the research framework examining institutional investors and green innovation, thereby addressing the literature gap concerning the insufficient attention to the “temporal attribute” of institutional investors and enriching the application of corporate governance theory in the field of green development. (2) By comparing the differential moderating effects of environmental regulation and environmental subsidies, it clarifies the interactive logic of “government intervention—capital governance—corporate innovation,” thus providing new perspectives for understanding the synergistic mechanisms between policy instruments and market forces. (3) What role do government policies play in this? Using 2007–2022 Chinese A-share listed company data, this paper analyzes the connection linking institutional investment horizons to corporate environmental innovation, while exploring the channels through which these effects operate. Based on our analysis, our results demonstrate that extended investment horizons among institutional investors substantially enhance corporate green innovation, with long-term holders driving the most substantial improvements. Our analysis of the underlying mechanism reveals that local government environmental policies and long-term institutional investors act as substitutes for each other in fostering corporate green innovation. More precisely, regions characterized by stricter environmental oversight demonstrate that the enhancing role of long-term institutional ownership exhibits high contextual dependence, demonstrating weaker outcomes in jurisdictions with lenient environmental policies and stronger outcomes where regulatory pressure is greater. Environmental subsidy policies and long-term institutional investors mutually reinforce each other in driving green innovation; environmental subsidies increase the resources available to enterprises, which may be directed towards green innovation under the proactive intervention mechanism of long-term institutional investors.

The contributions of this research can be categorized into three key aspects: (1) For the first time, this paper introduces the investment horizon of institutional investors in the study of corporate green innovation, expanding the literature on institutional investors. Previous research has largely underexplored the temporal dimensions of institutional ownership, a gap that the present study addresses to extend corporate governance theory. (2) This study explores how two different environmental policies—government environmental regulation and environmental subsidies—affect the relationship between the investment horizon of institutional investors and corporate green innovation. (3) Our research enhances the conceptual comprehension of the drivers behind corporate environmental innovation. Existing literature has overlooked the impact of the investment horizon of institutional investors on corporate green innovation. The investment horizon of institutional investors is an important governance mechanism. The investment horizon of institutional investors serves as the core driver of their governance engagement; long-term holders are inclined toward active governance, while their short-term counterparts are largely disinclined. This paper pioneers the exploration of the mechanism by which the investment horizon of institutional investors affects corporate green innovation. By elucidating how government environmental policies affect corporate green innovation, this study introduces a novel analytical lens through which to examine how institutional investors’ temporal orientations shape corporate outcomes and delivers practical implications for promoting green innovation. This study is structured as follows: Section 2 conducts a thorough literature review and formulates testable hypotheses; Section 3 outlines the research design and data sources; Section 4 reports empirical findings and mechanism tests; and Section 5 provides concluding remarks.

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Literature Review

With the increasing severity of environmental issues, green innovation has attracted significant interest within the fields of environmental economics and innovation research. Existing research primarily draws on institutional theory, stakeholder theory, and the resource-based view to conduct a systematic analysis of the internal and external drivers of corporate green innovation [23,24,25].

Research based on institutional theory mainly focuses on the impact of national environmental policies, such as the effects of implementing environmental tax and other environmental regulation policies, and the impact of providing environmental subsidies. Scholars have not reached a consensus. Early literature suggested that environmental regulation increases corporate environmental costs, thereby crowding out productive investments and suppressing corporate green innovation [19]. However, the Porter Hypothesis posits that environmental regulations can compel firms to increase their investment in green innovation [22], compensating for corporate environmental costs through “innovation compensation” [20,26,27], and green innovation can also build competitive advantages for companies, achieving sustainable growth [28,29]. While low-carbon transition bonds in China have been shown to reduce firms’ financing costs and foster green transformation [30].

Within the framework of stakeholder theory, scholarly work often investigates the role of key corporate stakeholders, including investors, consumers, suppliers, and the public [31,32,33]. Driven by the growing green demands from consumers, suppliers, and other partners, firms are inclined to adopt green innovation initiatives to enhance their environmental performance [34]. Serving as core drivers in capital markets, institutional investors substantially advance corporate green investment and innovation [7,8], promoting corporate green transformation. Independent directors facilitate green innovation by mitigating corporate agency problems [35].

Research grounded in resource-based theory investigates the role of organizational resource bases, management expertise, and knowledge assimilation capabilities in fostering corporate green innovation [23,36]. The resources that a company possesses, such as technology, knowledge, infrastructure, and information resources, are the foundation of green innovation [37,38], and the company’s management capabilities, environmental awareness, CEO gender, and other factors also affect corporate green innovation [39,40].

As core participants in capital markets, institutional investors’ shareholding behaviors and governance functions have become a research focus in the field of corporate finance. With their capital scale advantages and professional analytical capabilities, institutional investors occupy an important position in corporate external governance. Compared to retail investors, institutional investors are more inclined to participate in corporate decision-making through active shareholding rather than “voting with their feet.” This governance characteristic enables them to impose constraints on corporate inefficiencies such as non-efficient investment and agency problems [7,8]. In the context of green development, some studies have begun to focus on the environmental preferences of institutional investors, confirming that differences in their shareholding ratios, portfolio characteristics [10], institutional investor coalitions [11,12], green institutional investors [13], geographical distribution of institutional investors [14], and foreign institutional investors [15] can significantly promote corporate green investment, green innovation activities, and facilitate corporate green transformation. This provides direct literature support for the core hypothesis of this paper that “institutional investors influence corporate green innovation.” This provides direct literature support for this study’s core hypothesis that “institutional investors influence corporate green innovation.” However, existing research predominantly focuses on characteristics such as institutional investors’ shareholding ratios, ownership nature, and industry background, while generally overlooking the critical dimension of “investment horizon” that affects governance effectiveness. From a governance logic perspective, institutional investors’ monitoring functions and value orientations significantly differ with investment horizons: short-term institutional investors tend to focus on short-term performance metrics like quarterly earnings and may adopt a conservative stance toward green innovation due to its long payback periods and high uncertainty; whereas long-term institutional investors place greater emphasis on corporate sustainable development capabilities and are willing to promote green innovation through long-term supervision and resource support [23]. This governance divergence arising from investment horizons constitutes the core logical foundation for this study’s hypothesis that “long-term institutional investors positively influence corporate green innovation.”

Previous studies have been fruitful in the field of factors influencing corporate green innovation but have neglected the factor of institutional investors’ investment horizon. Institutional investors are the most important external governance factors in the capital market. The extant literature has extensively examined factors like the equity stake and categories of institutional investors, yet has largely neglected the pivotal role of investment horizon in their governance function. The supervisory function is most effectively exercised by those maintaining enduring ownership positions. By investigating how institutional investors’ time horizons shape green innovation, this study elucidates the underlying mechanisms through which they influence corporate green practices, thereby filling a critical research gap.

2.2. Hypothesis Development

Institutional investors represent an important and effective governance mechanism within companies, mitigating information asymmetry and agency problems [4]. While the positive role of institutional investors is well-documented in the literature, their functions vary significantly across different types [16]. One perspective for categorizing institutional investors is the duration of their investment horizon, which influences their approach to corporate governance. By virtue of their buy-and-hold strategy, which facilitates the spreading of monitoring costs and benefits over the long run, long-term investors are particularly adept at managerial oversight [18]. The investment horizon of institutional investors is an external governance mechanism that encourages management to focus on long-term corporate goals rather than short-term objectives [18]. Institutional investors fulfill these objectives through active monitoring and direct engagement with corporate leadership, among other proactive intervention mechanisms, which are the preferred mechanisms of long-term institutional investors [16,41]. Long-term investors do not choose to vote with their feet but instead opt to establish long-term relationships with the management of their investee companies, acquire a thorough grasp of the enterprise’s operations, execute well-informed interventions, and capture enduring value derived from systematic monitoring.

Green innovation encompasses a firm’s development of new products, processes, and managerial systems designed to achieve sustainable development objectives while generating positive economic and environmental outcomes [42]. This form of innovation generally falls into two primary classifications: green technological innovation and green organizational innovation. Green technological innovation pertains mainly to the creation of novel environmentally friendly products, green production processes, etc., reducing pollution at the source and improving the efficiency of resource and energy use [43]. In addition, end-of-pipe treatment technologies can reduce adverse environmental impacts, meet government environmental requirements, obtain a good green image, and avoid non-compliance costs [44]. Based on the cost–benefit theory and resource-based theory, green innovation can reduce costs, improve efficiency, form the core competitive advantage of enterprises, and thus contribute to sustainable corporate development [45]. Green management innovation generally improves the efficiency of resource acquisition and use through green management techniques and methods, enhances corporate green learning capabilities, and improves corporate sustainable development performance [46]. Green management innovation can also enable enterprises to comply with national environmental policies, thereby obtaining scarce resources such as tax incentives and environmental subsidies, while establishing good relationships with stakeholders, thus promoting the growth of corporate sustainable development performance [47].

Based on the preceding analysis, we postulate that a longer investment horizon of institutional investors correlates positively with higher levels of corporate green innovation, formulated as hypotheses H1a and H1b:

H1a.

The turnover rate of institutional investors demonstrates an adverse association with enterprises’ green innovation.

H1b.

Long-term institutional investors promote corporate green innovation.

Next, we propose hypotheses about the possible channels through which the investment horizon of institutional investors affects corporate green innovation. Government environmental policies, as external environmental governance mechanisms for companies, may interact with the external constraints imposed by long-term institutional investors. Government environmental policies consist of two different types of policies: environmental regulation and environmental subsidies. Environmental regulation is the government’s use of laws, regulations, and policies to restrict corporate production and business activities, encouraging enterprises to fulfill environmental protection responsibilities. Prior research demonstrates that regulatory pressures lead corporations to develop environmentally sustainable technologies and practices [26,27,29]. The inter-provincial disparities in environmental enforcement within China lead us to speculate on the existence of a substitutive dynamic between long-term institutional investors and local regulatory stringency. In areas with high environmental regulation intensity, long-term institutional investors lack the motivation to supervise and intervene, while in areas with weaker environmental regulation intensity, long-term institutional investors have a stronger incentive to supervise and intervene. In addition, environmental subsidies are also a type of government environmental policy. Contrary to environmental regulation, environmental subsidies are financial supports provided by the government for corporate environmental protection or management activities, in the form of cash payments or tax incentives, for environmental protection. The resource-based theory posits that corporate decision-making is influenced by the resources it possesses, and environmental subsidies alleviate corporate financial constraints. We speculate that under the same level of supervision and intervention by long-term institutional investors, the greater the subsidies a firm receives, the greater its investment in green innovation, thereby resulting in a higher level of green innovation. Put differently, environmental subsidies reinforce the function of long-term institutional investors through their engagement in green innovation. In summary, we propose H2 and H3:

H2.

Environmental regulatory stringency attenuates the connection linking long-term institutional investors with corporate green innovation.

H3.

Government environmental subsidies strengthen the relationship between long-term institutional investors and corporate green innovation.

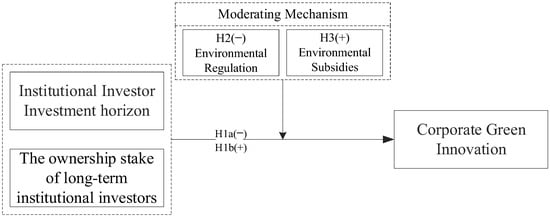

Figure 1 graphically represents the conceptual framework employed in this paper.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Framework Diagram.

3. Research Design

3.1. Sampling and Data

The core sample includes all A-share listed firms during the 2007–2022 timeframe. Following established research practices, we applied the following data cleaning procedures to ensure dataset reliability and validity: (1) excluding ST and *ST companies; (2) excluding companies in the financial industry; (3) removing observations with missing data for the dependent, independent, or other control variables; (4) winsorizing all continuous variables at the 1st and 99th percentiles. After this screening process, a final sample of 24,362 valid firm-year observations was obtained. Data for the core variables and control variables were sourced from the CSMAR database. All data processing was performed using Stata 17 software.

3.2. Variable

3.2.1. Dependent Variable: Green Innovation

There are two main indicators for measuring corporate green innovation. One approach adopts green R&D expenditure from the input dimension, whereas the alternative adopts an output-oriented perspective using green patent application counts as the indicator. The measurement of corporate green innovation in this research builds on green patent applications, which capture innovation outputs most directly and completely reflect firms’ green innovation initiatives through quantitative application records [1,48].

3.2.2. Independent Variables: Institutional Investor Turnover Rate and the Ownership Stake of Long-Term Institutional Investors

We first calculate the turnover rate in each investment institution’s portfolio [49]:

In the formula, CRi,t represents the turnover rate of institutional investor i in period t, Nj,i,t and Pj,t represent the number of shares and the price of the stock held by institutional investor i in company j during period t, and Q indicates the total number of companies in which institutional investor i has holdings.

Secondly, the weighted average turnover rate of institutional investor holdings is constructed using the turnover rate of each institutional investor:

In the formula, Wacri,t represents the weighted average turnover rate of all institutional investors in company k over the past four quarters, S denotes the set of all institutional investors in company k, and Wk,i,t indicates the holding weight of institutional investor i among all institutional investors in company k in the t-th quarter.

Lastly, we define the institutional investors with the lowest one-third annual turnover rates as long-term institutional investors, and the proportion of shares held by long-term institutional investors is denoted as Ltio. Conversely, the institutional investors with the highest one-third turnover rates are defined as short-term institutional investors, with the proportion of shares held by short-term institutional investors represented as Stio.

3.2.3. Control Variables

Consistent with prior research [4], our analysis accounts for these control variables. Company financial characteristic variables, including return on total assets, actual tax burden, operating cash flow, capital expenditure, and company size; corporate governance variables, such as the proportion of shares held by short-term institutional investors, the proportion of independent directors on the board, the proportion of shares held by the top three shareholders, and the combination of chairman and CEO roles: Table 1 provides the definitions for all variables.

Table 1.

Variable Definitions.

3.3. Model

This paper employs Model (3) to test the proposition of whether the investment horizon of institutional investors contributes to corporate green innovation. To examine the proposition of whether long-term institutional investors help to enhance corporate green innovation, we use Model (4) for the test. We measure the investment horizon of institutional investors by the turnover rate of institutional investors. Based on the analysis in the previous text, it is expected that the coefficient of Wacr will be significantly negative.

In the equation, β represents the coefficient, and CV stands for control variables, the specifics of which are shown in Table 1.

4. Data Analysis and Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

The descriptive statistical results of the variables are shown in Table 2. The mean of corporate green innovation (GI) is 0.700, with a standard deviation of 1.060, a minimum value of 0, and a maximum value of 4.300. The results reveal a low average level of corporate GI performance, accompanied by significant cross-firm heterogeneity. The institutional investor turnover rate (Wacr) averages 1.350, ranging from 0 to 5.630. This dispersion collectively indicates that institutional investors in China’s capital market maintain a short-term orientation, with an average investment horizon falling below one year. In China’s capital market, the average combined holding ratio of the one-third longest-term institutional investors is 35%, reaching a maximum of 86%, but there is also a significant variation, with a standard deviation of 24%. In contrast, with an average of 5%, the collective ownership of short-term institutional investors reaches up to 62% at its maximum.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics.

The return on assets (Roa) has a mean of 5%, with a minimum of −26% and a maximum of 25%, suggesting a relatively low level of overall profitability among listed companies. The maximum value of the top three shareholders’ holding ratio is 0.850, with a minimum of 0.141 and a mean of 0.353. For the proportion of independent directors (Inde_boart), the mean is 0.370, with observed values ranging from 0.300 to 0.570. The average of the chairman and general manager holding dual positions (Dual) is 0.260.

4.2. Benchmark Regression

The regression analysis in this paper is estimated with clustering by firm, and the corresponding results are presented in Table 3. The results in columns (1) and (2) of Table 3 correspond to the tests of Model (3). Column (1) does not control for other variables except the institutional investor turnover rate, while Column (2) controls for all variables as well as industry and year dummy variables. Analysis reveals a significant inverse relationship between institutional investor turnover and corporate green innovation. This finding, supported by a coefficient significant at the 1% level, provides confirmation for Hypothesis H1a. Columns (3), (4), (5), and (6) of Table 3 are the test results for Model (4). Column (3) demonstrates a strong positive relationship (coefficient = 0.577) between long-term institutional ownership and corporate green innovation, statistically significant at the 99% confidence level. After controlling for control variables, year, and industry fixed effects, Column (4) shows that this correlation coefficient β becomes 0.154, and Column (5) shows a coefficient of β = 0.129, both significant at the 1% level. This result clarifies that the shareholding ratio of long-term institutional investors has a promoting effect on corporate green innovation output. Furthermore, we set a dummy variable D_ltio_stio to indicate whether the shareholding ratio of long-term institutional investors is greater than that of short-term institutional investors, with a regression coefficient of β = 0.05 (p < 1%), consistent with Hypothesis H1b. The robustness of the model’s overall significance is demonstrated through F-test results (p < 0.001) maintained across all empirical specifications. Long-term institutional investors possess stronger incentives to oversee corporate management, focusing on long-term risks and sustainable development rather than short-term stock price fluctuations. Consequently, they encourage firms to pursue green transformation to mitigate future environmental regulatory risks. Moreover, green innovation projects—characterized by extended timelines and high risks—require precisely the kind of long-term, stable financial support that long-term investors provide as “patient capital.” Our findings align with existing literature [7], which has documented the positive role of institutional investors in corporate green governance. Our research refines this understanding by demonstrating that not all institutional investors contribute equally—only those with a long-term investment horizon exert such influence. This study advances existing scholarship through the novel integration of an investment horizon framework into corporate green innovation research. As consolidated in Table 3, the hypothesis testing results demonstrate that the core regression outputs validate the proposed hypotheses H1a and H1b.

Table 3.

Regression of wacr and ltio on GI: baseline regression.

4.3. Moderating Mechanism Regression

Within the theoretical framework of this study, we investigates how environmental regulation and subsidies moderate the association between long-term institutional investors and corporate green innovation. Next, this paper will test this in the empirical part.

4.3.1. Test of Environmental Regulation Moderating Effect

As a government-led governance tool, the core function of environmental regulation lies in establishing corporate environmental constraints through rigid regulatory measures, which creates critical interactions with the market supervision conducted by long-term institutional investors. Within the context of market-oriented transformation, governments in regions with high regulatory intensity directly assume some of the supervisory responsibilities that would otherwise be performed by institutional investors by strengthening environmental investments and regulatory systems. This essentially forms a “government regulation–market governance” substitution mechanism—when administrative supervision is sufficiently robust, the monitoring role of institutional investors becomes less critical for ensuring corporate environmental compliance. This study follows the approach of prior research by measuring environmental regulation using the ratio of provincial pollution control investment to industrial value-added [50,51].

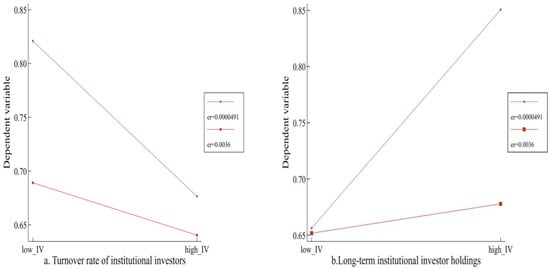

By incorporating an interaction term between environmental regulation and long-term institutional ownership into the model, Table 4 reports the estimation results. The significantly positive coefficient (at the 1% level) of the interaction term between environmental regulation and institutional investor turnover (ER*Wacr) indicates that environmental regulation directly mitigates the inhibitory effect of high investor turnover on green innovation by complementing supervisory functions. The flattened slope of the line in Figure 2a visually demonstrates this counterbalancing effect. The results in column (2) show a significantly negative coefficient (at the 1% level) for the interaction term between environmental regulation and long-term institutional investors (ER*Ltio), further confirming that the negative correlation between institutional investor turnover and green innovation is weakened in strong regulatory environments. In column (3), even after controlling for short-term institutional ownership, the core findings remain robust, indicating that the substitution mechanism is not influenced by other market governance factors. This verifies the robustness of the H3 conclusion.

Table 4.

Regulatory effects of environmental regulations.

Figure 2.

The environmental regulation weakens the relationship between institutional investor turnover rate and green innovation is shown in (a). The weakening effect of environmental regulation on the role of the proportion of shares held by long-term institutional investors is shown in (b). Source: own processing. Source: Own processing (2025).

These results demonstrate that the moderating value of environmental regulation is not merely an additive effect but operates through “complementary checks and balances between administrative regulation and market governance.” This mechanism reduces corporate reliance on the stability of long-term institutional ownership and provides dual governance safeguards for green innovation.

4.3.2. Test of Environmental Subsidies Moderating Effect

The dual externality characteristics of green innovation lead to insufficient market-driven investment. The core value of government environmental subsidies lies in addressing this dilemma through fiscal empowerment, thereby forming a complementary mechanism with long-term institutional investors characterized by “funding support–governance empowerment.” While subsidies inject tangible resources by directly alleviating financing constraints, institutional investors provide intangible governance by optimizing resource allocation and reducing agency costs through their long-term orientation [21]. Therefore, government environmental subsidies may form a complementary effect with long-term institutional investors, thereby strengthening the positive relationship between their shareholding and corporate green innovation.

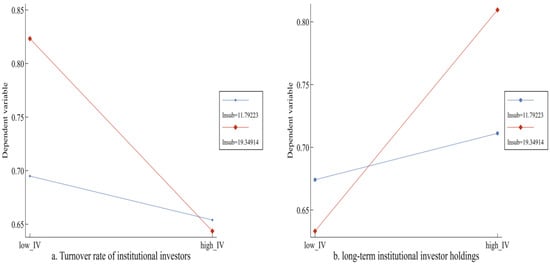

To empirically test this effect, we constructed an interaction term between government environmental subsidies (Lnsub) and long-term institutional ownership (Ltio). In Table 5, the interaction term between government environmental subsidies and institutional investor turnover (Lnsub*Wacr) is significantly negative (p < 0.01), indicating that subsidies weaken the negative impact of high turnover on green innovation. Meanwhile, the interaction term between subsidies and long-term institutional ownership (Lnsub*Ltio) is significantly positive (p < 0.01), and the conclusion remains robust after incorporating short-term institutional ownership as a control variable. This visually demonstrates that subsidies, by providing additional funding, make the long-term governance effects of institutional investors more readily achievable. The visualization results in Figure 3a,b further corroborate this synergistic amplification effect of “resources + governance.”

Table 5.

Regulatory effects of environmental subsidies.

Figure 3.

The environmental subsidies strengthen the relationship between institutional investor turnover rate and green innovation is shown in (a). The weakening effect of environmental subsidies on the role of the proportion of shares held by long-term institutional investors is shown in (b). Source: Own processing (2025).

Environmental subsidies do not merely represent simple capital injections; rather, through their complementary adaptation with market governance mechanisms, they address the dual bottlenecks of resource constraints and agency problems in green innovation. This provides policymakers with insights for coordinated implementation of fiscal support and capital guidance. These findings are consistent with the theoretical proposition of Hypothesis 3.

4.4. Robustness Test

4.4.1. Change in the Measurement of the Dependent Variable

Green patents include green invention patents and green utility model patents. Among these, green invention patents represent new technical proposals for green products, green process methods, or their improvements, better reflecting the investment intensity and technical level of corporate green innovation activities. In the robustness check, we replaced the dependent variable with the logarithm of “number of authorized green invention patents + 1” and re-estimated the main regression. The results are presented in Table 6. The findings show that in column (1) of Table 6, the coefficient for institutional investor turnover rate (Wacr) is −0.014 (p < 0.01). Columns (2) and (3) show coefficients for long-term institutional investors (Ltio) of 0.115 and 0.094, respectively (both significant at the 1% level). Column (4) shows a coefficient of 0.038 (p < 0.01) for the dummy variable D_ltio_stio, consistent with the core patterns in Table 3. The robustness check results for moderating effects are shown in Table 7, where the signs of the interaction term coefficients align with conclusions from existing literature, supporting hypotheses H2 and H3, and verifying the robustness of conclusions under different measures of the dependent variable.

Table 6.

Baseline regression robustness test: Change the way explained variables are measured.

Table 7.

Robustness test of the adjustment effect: change the measure of the explained variable.

4.4.2. Change in Sample Time Frame

To mitigate potential confounding effects of the 2008 financial crisis and the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic on corporate green innovation, we excluded data from these respective years and retained the 2009–2019 sample for renewed regression analysis to assess the robustness of our findings. The estimation results are presented in Table 8 and Table 9, where Table 8 reports the baseline regression results and Table 9 presents the moderating effect regression results. As shown in the regression results, the negative effect of institutional investor turnover rate and the positive effect of long-term institutional ownership remain statistically significant. The signs of the coefficients for the interaction terms involving environmental regulation, environmental subsidies, and institutional investor-related variables remain unchanged, providing further verification of our research hypotheses.

Table 8.

Baseline regression robustness test: Change sample time.

Table 9.

Robustness test for moderating effects: change sample time.

4.4.3. First-Order Lagged Explanatory Variable

Engaging in green innovation typically suggests that a company possesses strong R&D capabilities, a forward-looking management team, and sound corporate governance standards. Such inherent high-quality attributes tend to attract the attention and investment of institutional investors. To mitigate potential reverse causality concerns, we lagged the core explanatory variables by one period to reassess the robustness of our conclusions. Table 10 presents the baseline regression results, while Table 11 shows the regression results incorporating moderating effects. The results indicate that institutional investor turnover continues to exert a significantly negative impact on green innovation, long-term institutional ownership remains significantly positively correlated, and short-term institutional ownership also shows a significant positive relationship. The significance levels and signs of the interaction terms involving environmental regulation, environmental subsidies, and institutional investor-related variables remain unchanged, providing further validation of our research hypotheses.

Table 10.

Baseline regression robustness test: First-order lagged explanatory variable.

Table 11.

Robustness test for moderating effects: First-order lagged explanatory variable.

4.5. Endogenous Processing

4.5.1. Instrumental Variable Regression

There may be an endogeneity issue where corporate green innovation and the investment horizon of institutional investors influence each other. A firm’s green innovation performance could be a factor in institutional investors’ decision-making, organizations exhibiting strong fiscal health show a marked tendency to prioritize sustainable development projects in their strategic planning. To overcome the interference of endogeneity, this study follows the research methods of [4,52] and uses the CSI 300 Index as an instrumental variable for institutional turnover and long-term institutional ownership. The CSI 300 Index functions as a primary gauge of aggregate performance in China’s A-share market. As key market participants, both long-term and general institutional investors are likely to be influenced by broader market trends, as reflected in their turnover rates. However, the CSI 300 Index itself does not affect corporate green innovation activities; its changes reflect the overall market performance rather than the green innovation behavior of specific companies, thus meeting the conditions for an instrumental variable. Table 12 columns (1) and (3), report the first-stage estimation results of the CSI 300 Index, with the instrumental variable coefficients being 0.264 and −0.015, both significant at the 1% level, demonstrating the statistical significance of their correlation with the CSI 300 Index. Table 12 columns (2) and (4) contain the estimation results from the second-stage regressions, where we replaced the values of Wacr and Ltio with the fitted values from the first stage. The results show that the instrumented Wacr_pre coefficient is −0.520, and the Ltio_pre coefficient is 9.173, both significant at the 1% level, align with the respective regression outputs in Table 3. Table 13 presents the instrumental variable regression for the moderating effects. As the first-stage results match precisely with columns (1) and (3) of Table 12, they are not reported again, only the second-stage results are listed. Columns (1) and (2) of Table 11 show the main explanatory variable as the institutional investor turnover rate (wacr), with coefficients significantly negative (p < 1%). The coefficients of the interaction terms between the institutional investor turnover rate and environmental regulation, and between the institutional investor turnover rate and government environmental subsidies, remain unchanged and significant at the 1% level. Columns (3) and (4) of Table 13 show the main explanatory variable as the proportion of shares held by long-term institutional investors (Ltio), with coefficients of 2.46 (p < 1%) and 1.249 (p < 1%), respectively. The interaction term coefficient between Ltio and environmental regulation (ER*Ltio_pre) is −1.513 (p < 1%). The interaction of Ltio and government environmental subsidy (Lnsub*Ltio_pre) reports a coefficient of 0.069, which is statistically significant at the 1% level. The instrumental variable regression results are consistent with the previous text.

Table 12.

Baseline regression endogeneity test: instrumental variable method.

Table 13.

Endogeneity Tests for Moderating Effects: instrumental variable method.

4.5.2. PSM

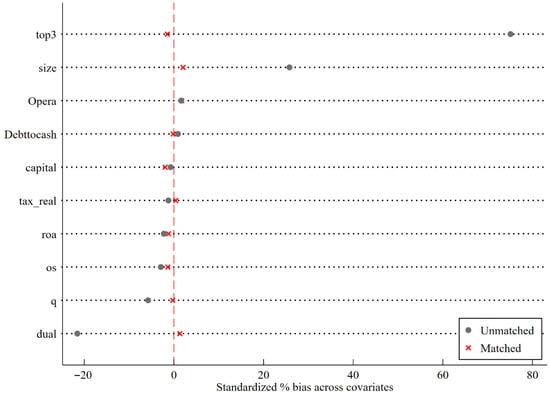

To further address endogeneity, we employ a Propensity Score Matching (PSM) approach. Initially, a dummy variable is created to identify firms characterized by high long-term ownership (Ltio above median) and low short-term ownership (Stio below median), assigning these cases a value of 1 and all others 0. The matching variables include all control variables from columns (2) and (4) of the baseline regression. Subsequently, we employ a probit model where this binary indicator serves as the dependent variable to derive propensity scores for the matching procedure. As shown in Figure 4, the matching procedure achieved balanced covariates between groups, with all control variables showing statistical equivalence after matching. Finally, we rerun the baseline regression and the moderating effect regression using the matched samples. As shown in Table 14, Table 15 and Table 16, the results are in line with previous research, thereby reinforcing the robustness of our conclusions.

Figure 4.

Test for matching results. Source: Own processing (2025).

Table 14.

Baseline regression endogeneity test: PSM method.

Table 15.

Endogeneity test of regulatory effects of environmental regulations: PSM method.

Table 16.

Endogeneity test of the regulatory effect of environmental subsidies: PSM method.

4.6. Heterogeneity Analysis

Given the significant differences between state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and non-state-owned enterprises (non-SOEs) in terms of resource acquisition capabilities and policy response motivations, this study empirically examines the heterogeneous impact of investor horizons on green innovation from the perspective of ownership nature. A t-test for cross-group coefficient differences was employed to assess whether the influence of ownership nature demonstrates statistically significant differences. Table 17 presents the results of the heterogeneity test based on firm ownership. Columns (1) and (2) show the regression results between institutional investor turnover and corporate green innovation. The results indicate that the regression coefficients for institutional investor turnover are significantly negative at the 1% level in both SOE and non-SOE samples, suggesting that high institutional investor turnover inhibits green innovation regardless of ownership nature. The p-value for the inter-group difference test is significant at the 1% level. Columns (3) and (4) present the regression results between long-term institutional investors and corporate green innovation. Long-term institutional investors show a significantly positive effect in non-SOEs, indicating that they promote green innovation more effectively in non-SOEs compared to SOEs. The underlying reason is that long-term institutional investors, as professional and patient market participants, can fully utilize their expertise and resource advantages in green innovation within the less administratively interfered and more market-oriented environment of non-SOEs, thereby forming a more effective innovation-driven cycle. The green innovation they advocate aligns perfectly with non-SOEs’ inherent needs for pursuing long-term profits and core competitiveness, resulting in more pronounced promotional effects. In contrast, the role of institutional investors in SOEs may be diluted by their complex institutional background and multiple objectives, consequently yielding relatively weaker promotional effects. The original hypotheses remain validated.

Table 17.

Results of Heterogeneity Analysis: Based on Nature of Firm Ownership.

5. Discussion

This study, through empirical research, reveals how institutional investors’ investment horizons affect corporate green innovation and delves into its underlying mechanisms. These findings provide novel theoretical perspectives and reliable empirical evidence on the drivers of corporate green innovation, while also offering valuable policy insights for leveraging capital markets to facilitate corporate sustainable transformation. The conclusions of this study provide specific references for policymakers to guide and incentivize long-term institutional investors in improving corporate governance mechanisms, promoting corporate green transformation, and supporting the achievement of the “dual carbon” goals. This section summarizes our research, compares it with previous studies, and evaluates the potential academic contributions and theoretical significance of our work.

First, as environmental issues become increasingly severe, green innovation has garnered significant attention in the fields of environmental economics and innovation research. Based on cost–benefit theory and resource-based theory, green innovation can reduce costs, enhance efficiency, form core corporate competitiveness, and thereby promote sustainable corporate development [45]. As key participants in the financial ecosystem, institutional investors play a central role in promoting corporate green investment and innovation [7,8]. Existing research has confirmed that institutional investors are important drivers of corporate green innovation, with related findings covering multiple dimensions such as shareholding ratios [9], portfolio characteristics [10], institutional investor alliances [11,12], green institutional investors [13], geographical distribution of institutional investors [14], and foreign institutional investors [15]. Unfortunately, existing studies have not systematically examined how institutional investors’ investment horizons affect green innovation. In fact, investment horizon is a core element of institutional investors’ governance role. Therefore, investigating the role of institutional investors’ investment horizons in green innovation holds particular significance. This study integrates theories from environmental economics and corporate finance, provides evidence on the impact of long-term institutional investors on green innovation, expands the literature on institutional investor horizons, enriches research on corporate green innovation, and fills this gap.

Second, environmental regulation directly constrains corporate production and operational behaviors through laws, policies, and other means, compelling enterprises to fulfill environmental responsibilities [26]. In regions with high environmental regulation intensity, companies face stringent environmental compliance pressures. Even in the absence of institutional investor supervision, they must allocate resources to green innovation to avoid non-compliance costs. In such contexts, the governance role of long-term institutional investors is “substituted” by government regulation, and their promotional effect is naturally weakened. In regions with weaker environmental regulation, market-based constraints are insufficient; therefore, the supervisory intervention of long-term institutional investors becomes a critical force to bridge the external governance gap, with their promotional effect on green innovation becoming more prominent. This finding addresses the debate in existing literature regarding the relationship between environmental regulation and corporate innovation. While some earlier studies argued that environmental regulation increases corporate costs and suppresses innovation [19], this study further reveals that the impact of environmental regulation must be considered in conjunction with the characteristics of external governance entities, such as institutional investors. The substitution relationship between the two provides a new perspective for understanding the implementation effects of environmental policies.

Third, resource-based theory indicates that corporate decision-making depends on their resource endowments. The high externality and substantial funding requirements of green innovation lead to severe financing constraints for enterprises [21]. Environmental subsidies provide direct resources to companies through cash support, tax incentives, and other forms, alleviating the financial pressure of green innovation. Meanwhile, the supervisory intervention of long-term institutional investors ensures that subsidy funds are not misappropriated but are directed toward green innovation activities. The two form a synergistic mechanism of “resource supply + governance assurance,” jointly driving the improvement of corporate green innovation levels. Existing research often examines the direct impact of environmental subsidies on green innovation [22] or the independent role of institutional investors in green innovation [11] in isolation. This study identifies the mutually reinforcing relationship between the two, indicating that the effective allocation of policy resources requires the coordination of external governance mechanisms, providing important insights for optimizing the effectiveness of environmental subsidy policies.

In summary, this study is the first to introduce institutional investors’ investment horizons into the research framework of corporate green innovation, expanding the boundaries of research on institutional investor perspectives. At the same time, by distinguishing the different moderating effects of environmental regulation and environmental subsidies, it reveals the interactive logic between government policies and market governance, enriching the literature on policy intervention mechanisms for green innovation. These results provide dual insights for promoting corporate green transformation: On the one hand, capital market regulators should guide institutional investors toward long-term shareholding, strengthen the governance role of long-term institutional investors by improving dividend mechanisms, restricting short-term trading, and other policies. On the other hand, the government should optimize the mix of environmental policies, appropriately reducing subsidy intensity in high-regulation regions while enhancing the synergy between subsidies and the guidance of institutional investors in low-regulation regions to improve policy implementation efficiency.

6. Conclusions, Policy Implications and Limitations

6.1. Conclusions

Green innovation is a fundamental mechanism for firms to achieve green transformation, thereby contributing significantly to reconciling economic growth with environmental protection and alleviating ecological pressures. As key agents in capital markets, institutional investors contribute to corporate governance and play a critical role in advancing firms’ green transformation. Using a sample of Shanghai and Shenzhen A-share enterprises during the 2007–2022 period, this paper explores the connections between institutional investment horizons and corporate green innovation, together with the roles of governmental environmental oversight and fiscal incentives. Pioneering in its approach, this research integrates the investment horizon of institutional investors into the study of corporate green innovation drivers, analyzing the role of government environmental policy through the theoretical lenses of the Resource-Based View, Stakeholder Theory, and Corporate Governance Theory. This study enriches the literature on the determinants of green innovation and offers novel insights into the role of institutional investors in fostering corporate green innovation, with both scholarly and practical implications. The main findings are as follows:

First, the investment horizon of institutional investors constitutes a significant force in corporate governance, positively influencing corporate green innovation. Long-term institutional investors, in particular, leverage their influence through active monitoring, shareholder proposals, and direct engagement with management to foster such innovation. Secondly, a substitution effect operates between local environmental regulatory policies and long-term institutional investors in their roles for fostering green innovation. In areas with higher environmental regulation intensity, the promoting effect of long-term institutional investors on corporate green innovation is weaker, regions characterized by stricter environmental oversight exhibit more pronounced enhancement effects. Thirdly, environmental subsidy policies and the governance functions performed by long-term institutional investors in green innovation show a mutually enhancing effect; environmental subsidies increase the resources available to enterprises, which may be directed towards green innovation under the proactive intervention mechanism of long-term institutional investors.

6.2. Policy Implications

Drawing on the empirical results presented above, the following policy recommendations are advanced: Firstly, long-term institutional investors can alleviate the environmental agency problems between enterprises and society. Long-term institutional investors promote corporate green innovation and achieve environmental goals through proactive intervention mechanisms such as supervision, shareholder proposals, and discussions with management. The capital market, as an important platform for optimizing resource allocation, should play an important role in the sustainable development process of enterprises. The persistent growth in institutional investors’ scale necessitates orientation toward extended investment horizons, creating essential conditions for advancing capital market governance and institutional supervisory capacity. Therefore, capital market regulatory authorities should establish corresponding mechanisms to restrict short-term investments by institutional investors, while guiding and encouraging listed companies to increase dividend payout ratios to promote long-term shareholding by institutional investors. Secondly, government environmental regulation and external governance mechanisms such as government environmental subsidies to enterprises will also affect the role of long-term institutional investors. We recommend that regulatory authorities and industry associations promote the issuance of a voluntary, China-specific Stewardship Code for institutional investors. This code should explicitly encourage institutional investors to actively exercise voting rights, engage in communication with listed companies, and disclose in their stewardship reports how they engage with and shape the environmental, social, and governance practices within their portfolio companies, including green innovation strategies. The regulatory authorities should refine voting and communication mechanisms to better facilitate institutional investors’ engagement in corporate governance, and encourage listed companies to engage in regular, in-depth communication with their major institutional investors regarding long-term strategy. Specifically, environmental regulation and long-term institutional investors can substitute for each other in fostering green innovation, governmental ecological subsidies and long-term institutional investors’ sustainability efforts operate in a mutually reinforcing manner. As the core governance entity in the green innovation system, the government’s fundamental role is to balance market governance and administrative intervention through dual drivers of “rigid regulation + targeted empowerment,” rather than relying on single policy supply. Building on previous analysis, environmental regulation and long-term institutional investors exhibit a substitution relationship in promoting green innovation. Therefore, the government should act as a regulator, establishing market-based constraints through rigid regulation, leveraging the “substitution effect” of government oversight to compensate for insufficient supervision by institutional investors and compelling companies to fulfill their environmental responsibilities. Meanwhile, government ecological subsidies and the sustainability efforts of long-term institutional investors create a complementary effect. Under this complementary mechanism, the government should function as an enabler, activating synergistic effects through targeted subsidies. Specifically, the government should establish an environmental investment-financial pressure linkage screening mechanism, focusing on high-investment, long-cycle key areas of green innovation to implement targeted subsidies. This allows government funds and the governance resources of institutional investors to form a “complementary synergy,” breaking resource constraints for enterprises. Additionally, implementing targeted subsidies can enhance the promotional effect of environmental subsidies and improve regulatory policies for long-term funds such as pensions. At the same time, establish mechanisms to identify enterprises that are financially vulnerable due to the fulfillment of environmental and other social responsibilities, and provide targeted subsidies, which may enhance the promoting effect of environmental subsidies. Improve the regulatory policies for pensions. We suggest that regulatory authorities, when evaluating the performance of long-term funds such as the National Social Security Fund and enterprise annuities, gradually shift away from short-term return metrics and introduce longer assessment cycles. This can serve as a fundamental incentive for fund managers to adopt a long-term investment philosophy, one that is oriented towards the long-term value creation of firms, thereby transforming them into the “long-term institutional investors” described in our study. Encourage the development of private equity funds and industrial funds targeting long-term value investment, and provide appropriate policy facilitation for their investments in companies within the green technology innovation sector.

6.3. Limitations

Unfortunately, this study also bears certain limitations. Firstly, due to the limitations of data and materials, we cannot accurately measure the turnover rate of institutional investors, as the data on institutional investors’ shareholding is updated only once every quarter, resulting in a certain measurement error in the data on the turnover rate of institutional investors. This study employs shareholding duration as the primary criterion for identifying long-term investment behavior. There is inevitably some subjectivity in the judgment of long-term institutional investors. We identify the investors with the longest investment horizon in the market as long-term investors. There are some institutional investors who invest for short-term purposes but are forced to hold for the long term. Future research can examine the role played by some long-term institutional investors, such as pension funds, on corporate governance.

In addition, the governance role that long-term institutional investors play in monitoring a company must arise through some channel, such as the possible channels of electing independent directors, supervisors, and participation in company board meetings. Subsequent investigations could examine the specific mechanisms employed by long-term institutional investors when engaging with corporate governance systems. Such inquiry would substantially advance comprehension of how institutional ownership shapes governance outcomes.

Finally, current research singularly examines how a specific factor affects firms’ green innovation. It is recommended that future research construct a theoretical framework for influencing firms’ green innovation that incorporates all factors that affect firms’ green innovation to facilitate a comparative weighing of which factors are more important, and which are more critical for the development of policies to promote firms’ green innovation.

Author Contributions

Q.Q.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, and Writing—review & editing. Y.C.: Data curation, Formal analysis, and Writing—original draft. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Social Science Fund of China (22BGL077).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data will be made available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Liu, L.; Zhao, Z.; Su, B.; Ng, T.S.; Zhang, M.; Qi, L. Structural breakpoints in the relationship between outward foreign direct investment and green innovation: An empirical study in China. Energy Econ. 2021, 103, 105578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, G.; Jia, Y.; Zou, H. Is institutional pressure the mother of green innovation? Examining the moderating effect of absorptive capacity. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 278, 123957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, F.; Peng, S.; Ye, K. Multiple large shareholders and corporate social responsibility reporting. Emerg. Mark. Rev. 2019, 38, 287–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driss, H.; Drobetz, W.; El Ghoul, S.; Guedhami, O. Institutional investment horizons, corporate governance, and credit ratings: International evidence. J. Corp. Finance 2021, 67, 101874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azar, J.; Duro, M.; Kadach, I.; Ormazabal, G. The Big Three and corporate carbon emissions around the world. J. Financial Econ. 2021, 142, 674–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zeng, S.; Qi, S.; Cui, J. Do institutional investors facilitate corporate environmental innovation? Energy Econ. 2023, 117, 106472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Sánchez, I.-M.; Aibar-Guzmán, C.; Aibar-Guzmán, B. The effect of institutional ownership and ownership dispersion on eco-innovation. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2020, 158, 120173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Yuan, Q. Institutional investors’ corporate site visits and corporate innovation. J. Corp. Finance 2018, 48, 148–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, L.; Yang, J. Institutional Investors and Green Innovation of Stateowned Enterprises—Based on the Intermediary Role of Green Agency Costs. In Proceedings of the 2022 6th International Conference on Business and Information Management (ICBIM), Guangzhou, China (Virtual), 26–28 August 2022; pp. 112–118. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.; Qu, J.; Wei, J.; Yin, H.; Xi, X. The effects of institutional investors on firms’ green innovation. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2023, 40, 195–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Wang, H.; Wang, X. Common institutional ownership and corporate social responsibility. J. Bank. Finance 2022, 136, 106218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Zhu, T.; Xia, X.; Zhao, Z.; Zhao, Y. Common institutional ownership and corporate green investment: Evidence from China. Int. Rev. Econ. Finance 2024, 91, 1123–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Liu, L. Green institutional investors and corporate green innovation: Evidence from Chinese listed companies. Int. Rev. Econ. Finance 2025, 103, 104476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Q.; Li, X.; Sun, Y.; Han, Y. Institutional investors’ green activism and corporate green innovation: Based on the behind-scene communications. Emerg. Mark. Finance Trade 2024, 60, 3284–3307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Tang, X.; Liu, L.; Lai, H. Foreign institutional investors and corporate green innovation: Evidence from an emerging economy. Emerg. Mark. Finance Trade 2024, 60, 2096–2109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Döring, S.; Drobetz, W.; El Ghoul, S.; Guedhami, O.; Schröder, H. Cross-country determinants of institutional investors’ investment horizons. Finance Res. Lett. 2021, 39, 101641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, S. Over-investment of free cash flow. Rev. Account. Stud. 2006, 11, 159–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harford, J.; Kecskés, A.; Mansi, S. Do long-term investors improve corporate decision making? J. Corp. Finance 2018, 50, 424–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frondel, M.; Horbach, J.; Rennings, K. What triggers environmental management and innovation? Empirical evidence for Germany. Ecol. Econ. 2008, 66, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, U.; Wen, J.; Tabash, M.I.; Fadoul, M. Environmental regulations and capital investment: Does green innovation allow to grow? Int. Rev. Econ. Finance 2024, 89, 878–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, L.; Gao, S.; Wei, J.; Ding, Q. Government subsidy and corporate green innovation—Does board governance play a role? Energy Policy 2022, 161, 112720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Farooq, U.; Tabash, M.I.; El Refae, G.A.; Ahmed, J.; Subhani, B.H. Government green environmental concerns and corporate real investment decisions: Does financial sector development matter? Energy Policy 2021, 158, 112585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amore, M.D.; Bennedsen, M. Corporate governance and green innovation. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2016, 75, 54–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirel, P.; Kesidou, E. Sustainability-oriented capabilities for eco-innovation: Meeting the regulatory, technology, and market demands. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2019, 28, 847–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Yang&Ast, M.; Zhang, X. The effect of the carbon emission trading scheme on a firm’s total factor productivity: An analysis of corporate green innovation and resource allocation efficiency. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 1036482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hojnik, J.; Ruzzier, M. What drives eco-innovation? A review of an emerging literature. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transitions 2016, 19, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunila, M.; Ukko, J.; Rantala, T. Sustainability as a driver of green innovation investment and exploitation. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 179, 631–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, U.; Ahmed, J.; Tabash, M.I.; Anagreh, S.; Subhani, B.H. Nexus between government green environmental concerns and corporate real investment: Empirical evidence from selected Asian economies. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 314, 128089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanra, S.; Kaur, P.; Joseph, R.P.; Malik, A.; Dhir, A. A resource-based view of green innovation as a strategic firm resource: Present status and future directions. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2022, 31, 1395–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Kong, Y.; Du, P. The issuance spread of China’s low-carbon transition bonds. Mod. Finance 2024, 2, 80–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilg, P. How to foster green product innovation in an inert sector. J. Innov. Knowl. 2019, 4, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.K.; Del Giudice, M.; Jabbour, C.J.C.; Latan, H.; Sohal, A.S. Stakeholder pressure, green innovation, and performance in small and medium-sized enterprises: The role of green dynamic capabilities. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2022, 31, 500–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, X.; Wang, Y.; Qiu, L.; Zhang, K.; Zuo, J. Executive green investment vision, stakeholders’ green innovation concerns and enterprise green innovation performance. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 997865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Wang, Z.; Lai, K.-H. Mediating effect of managers’ environmental concern: Bridge between external pressures and firms’ practices of energy conservation in China. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 43, 203–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Q.; Yu, J. Impact of independent director network on corporate green innovation: Evidence from Chinese listed companies. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2023, 30, 3271–3293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, P.; Sautner, Z.; Starks, L.T. The importance of climate risks for institutional investors. Rev. Financial Stud. 2020, 33, 1067–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-H.; Chen, Y.-S. Determinants of green competitive advantage: The roles of green knowledge sharing, green dynamic capabilities, and green service innovation. Qual. Quant. 2017, 51, 1663–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muscio, A.; Nardone, G.; Stasi, A. How does the search for knowledge drive firms’ eco-innovation? Evidence from the wine industry. Ind. Innov. 2017, 24, 298–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangelico, R.M. Green product innovation: Where we are and where we are going. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2016, 25, 560–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketata, I.; Sofka, W.; Grimpe, C. The role of internal capabilities and firms’ environment for sustainable innovation: Evidence for Germany. Rd Manag. 2015, 45, 60–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimmock, S.G.; Gerken, W.C.; Ivković, Z.; Weisbenner, S.J. Capital gains lock-in and governance choices. J. Financial Econ. 2018, 127, 113–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-S. The Driver of green innovation and green image–green core competence. J. Bus. Ethic. 2008, 81, 531–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.C.; Yang, C.-L.; Sheu, C. The link between eco-innovation and business performance: A Taiwanese industry context. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 64, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.M.; Huo, J.G.; Zou, H.L. Green process innovation, green product innovation, and corporate financial performance: A content analysis method. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 101, 697–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Seman, N.A.; Govindan, K.; Mardani, A.; Ozkul, S.; Zakuan, N.; Saman, M.Z.M.; Hooker, R.E. The mediating effect of green innovation on the relationship between green supply chain management and environmental performance. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 229, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.-W.; Li, Y.-H. Green innovation and performance: The view of organizational capability and social reciprocity. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 145, 309–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pane Haden, S.S.; Oyler, J.D.; Humphreys, J.H. Historical, practical, and theoretical perspectives on green management: An exploratory analysis. Manag. Decis. 2009, 47, 1041–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhao, G. Impact of green innovation on firm value: Evidence from listed companies in China’s heavy pollution industries. Front. Energy Res. 2022, 9, 806926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspar, J.-M.; Massa, M.; Matos, P. Shareholder investment horizons and the market for corporate control. J. Financial Econ. 2005, 76, 135–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, G.; Wang, S.; Zhang, B. Watering down environmental regulation in China. Q. J. Econ. 2020, 135, 2135–2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Kong, S. The effect of environmental regulation on green total-factor productivity in China’s industry. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2022, 94, 106757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appel, I.R.; Gormley, T.A.; Keim, D.B. Passive investors, not passive owners. J. Financial Econ. 2016, 121, 111–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).