Abstract

Numerous studies in the field of leadership have shown an important role for leadership in sustaining organizations by building an organizational culture that is both collaborative and sustainable, with trust at its core. However, existing research has not integrated evidence on how leadership fosters well-being and innovation. This study conducted a systematic literature review following the PRISMA 2020 guidelines, based on the Scopus database for the period 2016–2025. A total of 35 peer-reviewed articles met the inclusion criteria. The data were analyzed through thematic coding and bibliometric visualization using VOSviewer 16.20. The findings reveal three dominant research areas: (1) sustainable leadership as a driver of organizational culture; (2) collaborative and participative leadership that promotes learning and trust; (3) integrating collaborative learning and innovation with employee well-being. The review also highlights important contextual differences across settings and leadership approaches to the leadership role and shared decision-making. It provides a synthesized analysis that illustrates how different forms of leadership shape collaborative learning and employee well-being. Given the importance and breadth of the concepts that this topic addresses, the study also offers several directions for future research.

1. Introduction

Nowadays, digitization and automation have introduced new obstacles, imposing a high burden on corporate executives to operate in a volatile, dynamic, and uncertain environment []. Pressure from governments and non-governmental groups has encouraged industries to incorporate environmental and social factors into their development goals, which is a key driver of the SDGs []. Organizations face environmental, social, and financial concerns, and executives must respond to and manage these competing agendas to improve and generate value within their firms []. These changes in the work environment, such as new needs from firm stakeholders, are changing how organizations should be managed [].

In this context, the UN 2030 agenda and the SDGs provide an even stronger incentive and opportunity to operationalize integration across traditional disciplinary and sectoral silos and domains of development []. However, overcoming the challenge of integration and cross-sectoral collaboration in development is especially difficult because the social-ecological systems within which integrated development actions are elaborated are constantly changing, necessitating adaptive development modalities and collaborations.

Within organizations, companies with a strong collaborative culture are more successful at encouraging sustainable innovations, reducing environmental harm, and increasing employee engagement [].

Leadership is a complicated and comprehensive concept that has been thoroughly researched in various fields, including management, psychology, and sociology. Scholars typically define leadership based on their viewpoints and the aspects of the phenomenon that most interest them []. At the same time, sustainable leadership is a shared responsibility that takes care of and refrains from causing harm to the local community and educational environment, while not excessively using up financial or human resources []. In addition to creating an educational environment of organizational diversity that encourages the cross-fertilization of effective practices and good ideas in communities of shared learning and development, sustainable leadership actively engages with the forces that impact it.

These leaders need to possess the ability to read and foresee complexity, solve complex problems, facilitate dynamic organizational change, and manage their own emotions throughout complicated problem-solving []. Sustainable leaders prioritize long-term outcomes, sustainable transformation, and capacity building, which forces them to look beyond short-term gains to consider a broader context when achieving the SDGs []. They can improve employee well-being by stressing an organization’s environmental, social, and economic elements. Furthermore, paying adequate attention to the social component in organizations (e.g., work–life balance, supporting employee health) reduces stress while increasing motivation, engagement, and well-being [].

The most frequently referenced crucial Success Factor in the literature and seen as crucial to sustainability, Total Quality Management (TQM), and value co-creation, is top management’s leadership style []. Sustainability leadership is defined as someone who stimulates and incorporates followers to overcome sustainability hurdles, confront issues, and meet the requirements of the present without jeopardizing future generations [].

Conversations about sustainable business and economics are increasingly focusing on “triple bottom line” results, where necessary company plans are created to be both financially feasible and socially and environmentally responsible []. Organizations and policymakers are reevaluating their strategic approaches to resilience and long-term value creation due to the growing urgency of global sustainability concerns []. Specifically, the shift to sustainability necessitates technological innovation and reorganizing leadership behaviors and organizational processes that promote cross-sector collaborative learning []. To specifically transform sustainable leadership practices into sustainable development outputs, businesses could rely on the knowledge production, sharing, dissemination, and integration aspects of organizational learning [].

Some types of collaboration emphasize scientific research, while others convert scientific discoveries into fresh approaches to address societal issues []. Still, others combine the knowledge of various disciplines and professions in a community-wide endeavor to create and execute policies that improve public health, the environment, and society.

It is well acknowledged that leadership drives this change, helping businesses navigate ambiguity, fostering creativity, and involving various stakeholders in creating sustainable futures []. In parallel, strong leadership is critical in advancing environmental projects. Organizational structures such as green committees, Green Offices, sustainability councils, and specialized sustainability offices have been formed to administer and advance sustainability projects at universities [].

On the other hand, collaborative and reflective learning supports the development of complex competencies and important employability skills to foster sustainable development []. As a result, reflection, as one of the primary tools, circumstances, and education/training techniques for acquiring and developing critical abilities for sustainability education, is particularly focused on in the context of leadership.

Moreover, a growing body of literature highlights the importance of organizations enhancing their adaptive capacity and integrating sustainability into their operations through collaborative and cross-sectoral learning. The goals of Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 17, which highlight the need for inclusive cooperation between public, private, and civil society actors, are closely aligned with this strategy []. Leadership, among other factors, is critical in fostering employee innovation to achieve an organization’s goals. Organizational issues also limit the inventiveness of persons working together []. Effective leadership development and dedication to organizational environmental sustainability necessitate a shift in mindset [].

Consistent patterns connecting collaborative learning, sustainable leadership, and well-being results have been found in several recent empirical investigations. By improving staff resilience, sustainable leadership influences workers’ well-being []. Sustainable leadership improves procedural knowledge in the healthcare industry, and also promotes compassion and, ultimately, well-being []. Sustainable employee performance is directly improved by work–life balance and organizational learning practices, and at the same time, green transformational leadership increases job satisfaction and improves performance []. To support the importance of distributed/peer leadership in sustainable work outcomes, certain roles and functions of peer leadership predict job satisfaction, team cohesiveness, team effectiveness, and organizational citizenship behavior []. Strong collaborative cultures are also associated with increased employee engagement, reduced environmental impact, and higher levels of sustainable innovation [].

Organizations’ efforts for environmental sustainability rely (at least in part) on an organization’s ability to look ahead and take a long-term perspective to solve problems. Socially, sustainability encompasses fair labor practices, inclusivity, community engagement, and employee well-being [].

Nevertheless, even with a more academic focus, a lack of clarity remains regarding how leadership facilitates cross-sectoral and organizational collaborative learning to achieve sustainable transitions [].

In management and organizational studies, collaborative leadership is a type of collective leadership that has received little attention. One of the reasons it is understudied is that it demands measuring leadership as a group practice, with the group serving as the unit of analysis rather than an individual leader, necessitating new methods of measuring what a group does to establish leadership [].

Few studies have comprehensively investigated the relationship between leadership, participatory innovation processes, and organizational learning in sustainability-oriented environments, despite previous reviews examining sustainability leadership in general [].

Earlier systematic literature reviews were conducted on sustainable leadership [], inclusive leadership [], leadership styles and sustainable performance [], collaborative innovation [], leadership and employee well-being, and work performance [], and creative industries to foster social innovation []. But none of them have combined sustainable leadership, collaborative learning, and well-being in a single systematic review.

This research gap is especially noteworthy because collaborative capacities are crucial for resilience in dynamic and complex situations []. Additionally, few assessments have specifically linked leadership-driven collaborative learning to quantifiable improvements in SDG alignment and organizational success. Furthermore, scholarly research in this area of study has generally remained limited and dispersed, lacking conceptual coherence and theoretical integration, despite the crucial role that sustainability leadership plays in tackling these global issues [,].

Leadership development in environmental sustainability is a relatively new issue that necessitates the capacity to do research and draw conclusions from a diverse range of publications []. As the corpus of research grows, a broader, systematic review technique will become more suitable.

Considering these issues, understanding how leadership practices can promote cooperation, learning, and well-being within businesses pursuing sustainability goals is becoming increasingly important. Few systematic reviews have at how these aspects interact to enhance organizational and human development outcomes, even though many have studied sustainable leadership or collaborative innovation separately. In order to close that gap, this study conducts a thorough literature analysis that unifies three important viewpoints—sustainable leadership, collaborative learning, and employee well-being—into a single analytical framework. The review advances a more comprehensive knowledge of how leadership supports sustainability-oriented transformation in businesses by combining insights from various contexts and techniques.

The primary objectives are:

- Synthesize the theoretical and empirical literature on the role of leadership in fostering collaborative innovation.

- Identify the methods by which cross-sector learning improves sustainability performance.

- Develop a conceptual framework that outlines the connections between leadership, learning, and SDG-aligned organizational transformation.

- Offer practical implications for business strategy and policy interventions in sustainability transitions.

The review explores ten years of peer-reviewed literature (2016–2025), utilizing the Scopus database and PRISMA methodology to ensure transparency and rigor in article selection. By doing so, the study aims to bridge a key gap in existing knowledge and provide actionable insights for scholars, practitioners, and policymakers working at the intersection of leadership and sustainability.

2. Literature Review

In today’s knowledge-based society, a sustainable firm is one that continuously learns, adapts to environmental changes, employs modern leadership, and prioritizes both the present and the future [].

Leadership is crucial for fostering collaborative creativity and ensuring long-term sustainability. Responsible leadership has become a rapidly growing theme in leadership discussions []. It can be defined as a relational and ethical phenomenon that occurs during social interactions with those who influence or are influenced by leadership and have a stake in the leadership relationship’s goal and vision. Essentially, it is founded on the normative notion that organizational leaders, as “citizens of the world,” have a co-responsibility to address the world’s most pressing challenges, such as hunger, poverty, or pandemic threats [].

These leadership styles differ from typical hierarchical structures by emphasizing shared vision, stakeholder participation, and global accountability []. Ethical leadership has been found to enhance company performance through values-based training and corporate social responsibility (CSR)-aligned branding []. Similarly, authentic and participative leadership styles are associated with more transparency, feedback-based learning, and strategic agility [,].

Van Der Voet and Steijn [] investigated the relationship between collaborative governance and visionary leadership by focusing on vision communication as a driver of interdisciplinary team creativity, and found out that visionary leadership is positively correlated with enhanced team cohesion and team boundary management over time.

Effective sustainability leadership requires focusing on sustainability values, leading from a living systems viewpoint, and fostering inclusive, collaborative processes []. Rotating leadership in collaborative innovation has been linked to improved performance, including alternating decision control, zig-zagging targets, and dynamic network cascades []. Public sector leaders can foster collaborative innovation by acting as meta-governors, coordinating processes, and overcoming impediments [].

Pedagogical approaches, including self-awareness, reflection, investigating multiple views, and experiential learning, are recommended to create leaders who are aware of sustainability concerns []. Research streams are frequently separated, underscoring the need for additional integration in human resource development. The relationship between leadership, innovation, and sustainability is complicated [].

According to recent research, leadership is more than just a hierarchical role; it is a relational and dynamic process that promotes the formation of knowledge networks, shared vision, and inventive problem-solving in complex contexts. Garavan et al. [] conducted a meta-analysis of the relationship between training and organizational performance, finding that leadership development interventions have a significant beneficial influence on outcomes when contextual and institutional variables are adequately taken into account. This highlights the importance of leadership techniques that consider internal culture, sectoral dynamics, and long-term sustainability goals.

However, cocreation may face challenges due to a lack of political support, inadequate reflexive leadership, poor institutional design, financial constraints, and unforeseen events such as natural disasters, wars, economic crises, and political disputes that impede collaboration []. One way to achieve results through co-creation is by utilizing platforms that typically require dynamic leadership and supportive champions among participating stakeholders.

Collaborative leadership involves working together to share power and responsibilities in the decision-making process. This strategy works exceptionally well for facilitating collaborative learning because it creates an environment in which people feel valued and empowered to contribute. Collaborative leaders usually function as facilitators, bringing together diverse perspectives and experiences to achieve common goals []. Inclusive leaders create environments where everyone feels valued and empowered to contribute. This is especially important in collaborative learning since it ensures that different viewpoints are brought to the table. Collaborative leaders usually function as facilitators, bringing together diverse perspectives and experiences to achieve common goals []. Inclusive leaders create environments where everyone feels valued and empowered to contribute. This is especially important in collaborative learning since it ensures that different viewpoints are brought to the table. Empowering individuals generates a sense of ownership and accountability, which can improve the success of joint initiatives []. Leaders who foster reflection and self-awareness help people recognize their strengths and shortcomings, as well as the dynamics of their groups. This can lead to improved teamwork and a better understanding of sustainability challenges and opportunities []. Effective leaders in collaborative learning environments usually act as facilitators rather than directors. They provide critical support and resources to help individuals and organizations achieve their goals while also establishing an environment conducive to learning and innovation.

Leaders who can define a clear vision and strategy can effectively steer collaborative learning activities, ensuring they align with broader sustainability goals. This visionary approach can aid in attention and direction, particularly in the face of complicated and changing circumstances []. Leaders who are devoted to sustainability can help drive organizational change and promote environmentally and socially responsible practices. Leaders may promote a sustainable culture by establishing sustainability values throughout the organization. Collaboration, employee participation, feedback, idea sharing, and employee voice and influence in decision-making processes are all encouraged by a green corporate culture []. Other research findings show that companies with a strong collaborative culture are more successful at promoting sustainable technologies, reducing their negative effects on the environment, and raising employee engagement []. This can be accomplished in various ways, such as developing sustainability-focused policies, promoting sustainable practices, and encouraging sustainability-related learning and innovation []. Leaders who foster an environment of innovation. Creativity can help create new ideas and practices that enhance sustainability efforts. This approach is especially effective in collaborative learning settings, where diverse perspectives and expertise can be combined to tackle complex problems []. One of the most difficult challenges in collaborative learning environments is achieving a balance between individual and group expectations and interests. Leaders must be able to effectively manage these dynamics for collaborative efforts to be both fruitful and equitable []. As we move forward in a rapidly changing and interconnected world, we need leaders who can inspire collaborative learning and growth. Table 1 provides a summary of the key leadership styles discussed, their characteristics, and their impact on collaborative learning, along with the relevant citations from the provided contexts.

Table 1.

Leadership Styles and Their Impact on Collaborative Learning.

Significant new findings have emerged in the literature in recent years. Employee well-being, a multifaceted notion that includes many facets but essentially relates to an individual’s sense of how they feel, is one example of such a finding []. A total of 88% of employees in companies with very good and good operational performance report having good mental health []. Furthermore, previous research indicates that the association between job engagement and compassionate leadership is significantly mediated by well-being [].

Numerous reviews and meta-analyses of the research have demonstrated the importance of leadership on worker well-being []. Ethical, participatory, and reflexive leadership traits are shared by sustainable leadership []. The essence of sustainable leadership is reflected in these qualities, which are very compatible with methods that promote the development and well-being of employees. When encouraging organizational innovation, motivating factors and employee well-being must be considered [].

The link between leadership and employee well-being is long established. Teetzen et al. [] suggest that health-oriented leadership is a critical factor in promoting a healthy corporate climate and influencing employee well-being, as leaders communicate company values and priorities to employees. While organizations must tailor their approach to their own specific needs and culture, those who commit totally to organizational well-being, create a strong capacity foundation, and engage all staff members in the process can enhance both staff resilience and mission achievement []. Organizations that prioritize the present and future performance of their workforce are deliberate in their recruitment, selection, training, development, retention, promotion, and other internal staffing strategies, even in the face of both anticipated and unforeseen losses []. To support the rising trend of incorporating leadership development programs into the curriculum, the sustainability of leadership development program outcomes in various contexts can be investigated.

According to studies, demonstrating excellent leadership conduct supports a variety of employee outcomes, including motivation, job engagement, identity, and extra-role performance []. Such leaders demonstrate emotional aptitude and hopefulness in managing people, empowering and helping employees communicate, be responsible, and achieve at their jobs.

According to Wang et al. [] information sharing practices within teams are connected not only with enhanced innovative behaviors but also with a sense of self-achievement and success at work, both of which contribute to psychological well-being. This is also consistent with Trivedi’s and Singh [] findings, which suggest that the act of sharing information and engaging in collaborative practices is itself a source of well-being, as employees feel a better sense of purpose and support. Acquiring and sharing knowledge is a constant activity, which suits the concept of well-being []. People can discover life satisfaction and a sense of success even while they are going through a difficult moment. Organizations that encourage knowledge sharing have higher flourishing levels among their personnel, which leads to the implementation of more social sustainability initiatives within their organizations []. Another reason for increased interest is that employees have unique behavioral qualities that firms cannot take for granted. Employees have distinct requirements, act voluntarily, and may leave if they believe they are undervalued in the workplace []. Employee participation in driving innovation is hampered by organizational silo architecture and restrictive conditions []. Organizational design also matters. Establishing a culture that promotes ongoing learning and information sharing requires establishing a clear causal relationship between learning organizations and creativity [].

Even while collaborative leadership places a strong emphasis on involvement, shared accountability, and mutual trust, unfavorable organizational circumstances can severely limit its efficacy. Employees in high-stress, performance-driven workplaces are frequently less receptive to cooperation and introspection, which results in competitive or defensive actions rather than group learning []. Similarly, bureaucratic organizational cultures can hinder the flexibility needed for inclusive decision-making and shared accountability by discouraging initiative and transparency []. Furthermore, the collaborative environment required for sustainable leadership practices can be undermined by the existence of narcissistic leadership traits, such as self-centeredness, a lack of empathy, and an overwhelming demand for recognition []. A more thorough grasp of the constraints and difficulties faced by collaborative leadership models in organizational settings can be obtained by acknowledging these contextual impediments. Recent evidence also suggests that the success of collaborative leadership is heavily reliant on contextual design factors such as organizational structure, communication systems, and trust-building mechanisms, all of which must be intentionally developed to sustain collaboration across hierarchical settings [].

3. Materials and Methods

This study used a systematic literature review guided by the PRISMA [] (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) paradigm to ensure rigor, transparency, and replicability in article identification, screening, and inclusion. The primary purpose was to summarize current academic information on the role of leadership in promoting collaborative learning and innovation for organizational sustainability.

Although systematic literature reviews were originally established for medical research, they are now commonly used in the social sciences and management []. Hierbl [] goes even further, describing a systematic review of management research as the “new normal” in reviews. Even though systematic reviews are still in their early stages, there is widespread agreement on the best methodological aspects [].

The Scopus database was chosen as the only data source for this review. Scopus is well-known in the academic community for its extensive coverage of high-quality peer-reviewed papers, notably in management, business, social sciences, and sustainability [,]. Scopus outperforms other databases in terms of journal inclusion and citation tracking, making it an ideal choice for systematic reviews that require bibliometric analysis and thematic mapping. Its advanced filtering capabilities and restricted vocabulary (such as keywords and indexed subject areas) enable more accurate and reproducible searches. Scopus was chosen as the primary bibliographic database for this review because it has extensive coverage of peer-reviewed journals in management, sustainability, and leadership, as well as advanced tools for bibliometric mapping and citation analysis [,]. Scopus is also a database that indexes more journals and considerably aids scholars in discovering existing literature, particularly papers from 1995 onwards []. Although Web of Science offers high-quality coverage, Scopus was chosen for its larger scope in the social sciences and direct interoperability with VOSviewer 16.20. However, future research may investigate incorporating more databases to enhance the review’s comprehensiveness and robustness.

However, future studies may integrate other databases to strengthen the comprehensiveness of the review. Furthermore, it is worth noting that the sole use of the Scopus database may have reduced the number and diversity of studies included in this study. Furthermore, the selected publications differ in their research design and methodological approach (quantitative and qualitative), which may influence the comparability and generalizability while also enriching the interpretive depth and multidimensional understanding of the topic.

The search strategy used the following Boolean string, as in Table 2 below.

Table 2.

Search Strings Used in Scopus Database.

Articles were screened using rigorous inclusion and exclusion criteria defined at the beginning of the process. The pre-defined selection criterion was to focus on journal articles, published in English between 2016 and 2025, focused on leadership, co-creation, and sustainability. In accordance with PRISMA guidelines, the exclusion criteria were methodological quality, theoretical contribution, and relevance to the study subject, rather than citation frequency.

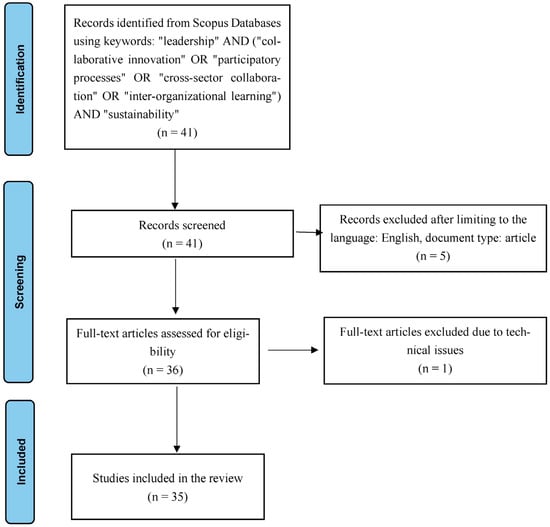

Data were thematically coded by the authors using Excel spreadsheets and cross-checked to ensure the reliability of the process. Two researchers independently screened the studies and evaluated their quality. The percentage of agreement amongst reviewers, or inter-rater reliability, was 92%. In accordance with best practices for reducing researcher bias in systematic reviews, any disagreements were discussed until a consensus was reached [,]. The initial search yielded 41 items. The PRISMA flow technique was used to screen articles for relevance and delete duplicates. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement was created in 2009 to help systematic reviews publicly disclose the purpose of the review, the actions taken by the authors, and the findings []. After screening, 35 papers met the final inclusion requirements, as shown in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Prisma flow map. Source: Authors’ elaboration based on Scopus data (2025), 5 May 2025.

To ensure scientific rigor and eliminate bias, the evaluation used a standardized quality and relevance assessment. Each article was evaluated in three dimensions: (1) conceptual and methodological relevance to the study’s objectives, (2) rigor in research design and analysis, and (3) contribution to the synthesis categories. These three dimensions were adopted from recognized quality appraisal frameworks, specifically the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) and the Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP) checklist, to ensure methodological consistency and comparability [,].

Using these criteria, the studies were classed as extremely relevant, relevant, or unrelated. This systematic process served as an adaptable quality evaluation, ensuring transparency and internal consistency in inclusion decisions and analytical interpretations.

Additionally, using Vosviewer software, Version 1.6.20 (Centre for Science and Technology Studies, Leiden University, Leiden, The Netherlands), a bibliometric analysis of 119 final publications was conducted initially in accordance with Zupic and Čater’s [] recommendations. Following the download of articles from Scopus to Microsoft Excel 2021 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA), the following order was used to gather the data: Citation by, DOI, Link, Affiliations, Authors with affiliations, Abstract, Author Keywords, Index Keywords, Authors, Author(s) ID, Title, Year, Source title, Volume, Issue, Art. No., Page start, Page end, Page count, Citation by, DOI, Link [].

For each article, a database was created in Excel, where after reading each article, country/region, sector/Industry, leadership style, learning mechanisms, connection with well-being, methodology, sustainability focus, outcomes, findings, and future research were noted in Excel. Detailed screening information is available in the Supplementary Materials (PRISMA 2020 Checklist).

4. Results

4.1. Bibliometric Analyses

Before proceeding with the analysis of the results, it is important to emphasize that the synthesis was based on coded evidence extracted from the 35 included studies and all thematic categories identified through VOSviewer were traced directly to these sources to ensure transparency and repeatability.

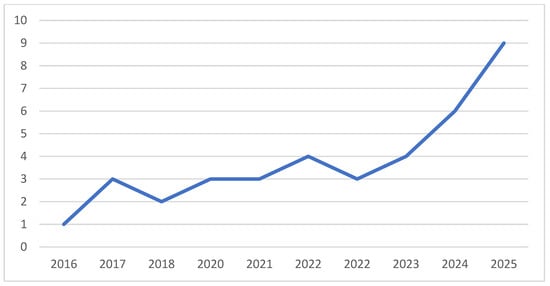

The number of publications on sustainability and associated business strategies has clearly been on the rise, especially since 2016. This rise is likely related to the worldwide movement for sustainable development that followed the adoption of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in 2015, which sparked interest in green transitions among academics and policymakers.

The steady and sharp increase from 2016 to 2022 suggests a spike in scholarly interest. This suggests a growing awareness of the importance of circular models in both policy circles and scholarly discourse. Interestingly, 2021 and 2022 exhibit peak values, possibly because of post-pandemic recovery plans that prioritized environmental sustainability and resilience. The data support the timeliness and relevance of your study by indicating that research in this area is growing quickly, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Number of publications by year. Source: Authors’ elaboration based on Scopus data (2025).

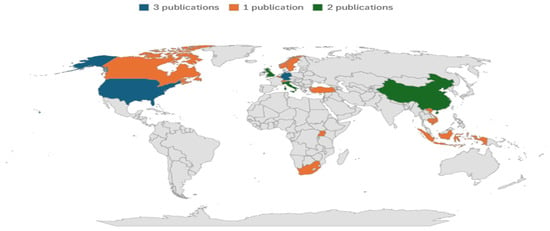

The geographical distribution of the reviewed literature is shown in Figure 3. For clarity, the colors in Figure 3 reflect only the number of publications per country and do not represent geopolitical or territorial boundaries. The map is used solely for visualization purposes. It reveals a concentrated focus of research findings in high-income countries, particularly the United States and the United Kingdom, which account for more articles. These are followed by China, Germany, Italy, Norway, and Sweden, indicating the academic dominance of the Global North in leadership and sustainability research. At the same time, research in developing countries, particularly those in East Africa and South Asia, is often minimal and appears primarily in multi-country collaborations or global studies. However, studies in Cambodia, Indonesia, Uganda, Vietnam, Tanzania, and Turkey can help us understand the specifics of the findings in these contexts. On the other hand, a significant part of the research follows a global or pan-European approach, suggesting an attempt to generalize the findings in different contexts. Future studies should prioritize empirical research in underrepresented regions to improve the inclusion and applicability of leadership and resilience frameworks in diverse socioeconomic contexts.

Figure 3.

Geographical distribution of the publication. Geographical distribution of the publications. Note: Colors represent only the number of reviewed publications per country (1, 2, or 3 publications). The map is used exclusively for illustrative and bibliometric purposes and does not imply any geopolitical, territorial, or administrative boundaries. Source: Authors’ elaboration based on Scopus data (2025).

The reviewed literature has employed a variety of methodological techniques, reflecting the interdisciplinary and dynamic nature of research on the relationship between leadership, collaborative learning, and organizational sustainability. Scholars have employed both qualitative and quantitative methodologies, as well as mixed-method designs, to investigate these complex employ qualitative methods, such as case studies, semi-structured interviews, and narrative inquiries, to offer in-depth often employ thematic content analysis and interpretive frameworks to examine how leadership fosters innovation, learning, and stakeholder engagement method content analysis and interpretive frameworks to investigate how leadership promotes innovation, learning, and stakeholder involvement within organizational contexts.

On the other hand, a substantial number of contributions employ quantitative methodologies, particularly survey-based designs paired with structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM), to evaluate hypotheses on leadership behaviors and sustainability outcomes. These studies often use validated assessment scales and large sample sizes to ensure statistical rigor and generalizability. A growing number of studies employ mixed-methods approaches to enhance the validity of findings by combining qualitative and quantitative data, such as interviewing with survey results or document analysis, alongside participant observations.

Furthermore, various theoretical and conceptual publications help to establish new frameworks that explain the mechanisms by which leadership promotes collaborative creativity and sustainability. Bibliometric and systematic literature reviews are also common in the discipline, and tools like VOSviewer and Bibliometrics can help map research trends and thematic clusters.

Literature’s methodological diversity emphasizes the topic’s complexity and the importance of both context-sensitive and evidence-based methods. However, longitudinal and comparative research, as well as standardized methodologies to analyze leadership’s long-term impact on sustainability transitions, are limited.

The steps followed in VOSViewer Excel, to create a map of keywords and clusters are as follows:

- Create;

- Create a map based on bibliographic data;

- Read data from bibliographic database files;

- Scopus;

- Type of analyses: co-occurrence, unit of analysis: all keywords;

- Counting method: full counting;

- Minimum number of occurrences of keywords: 2.

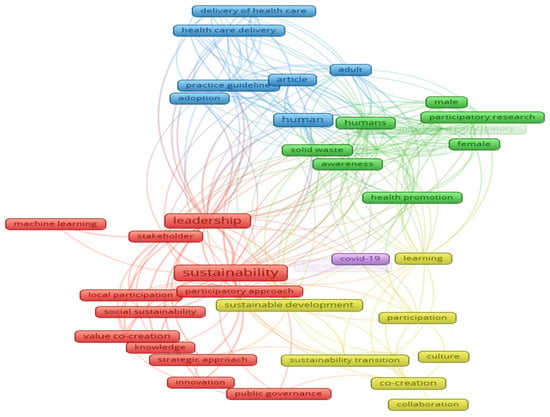

Based on this procedure, 5 clusters were obtained as shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Thematic Clusters Identified through VOSviewer Keyword Co-occurrence Analysis.

Cluster 1, in red, represents focusing on sustainability, leadership, and innovation and shows a focus on how leaders use knowledge-driven and participatory tactics to build institutions that support sustainability and innovation. It stands for the institutional and managerial aspects of long-term leadership.

The green cluster 2 highlights the social and communal aspect of sustainability by tying together health promotion, awareness-raising, community-based involvement, participatory research, and solid waste management.

Cluster 3 encompasses health care delivery, adoption, quality of care, and practice guidelines. It reflects research that connects sustainability and well-being via enhanced healthcare services, policy implementation, and human-centered methods.

The fourth cluster, which includes co-creation, collaboration, learning, a living lab, culture, and participation, highlights the learning and innovation processes that drive long-term transformation. Cluster 5 represents the contextual motivations for sustainability and leadership transformation.

A large number of research studies are focused on urban planning, climate governance, and city-level sustainability transitions [,,]. These studies often investigate how leadership fosters collaborative innovation in multi-actor urban systems, frequently employing living labs, co-creation platforms, or policy experimentation projects. Another vital domain is education, namely, higher education institutions and vocational training systems [,,]. These studies investigate sustainability leadership in teaching, curricular transformation, student co-creation, and campus operations, with some focus on transitions in primary and lower secondary education [].

Several studies focus on tertiary healthcare, palliative care, or public health systems, with an emphasis on interprofessional collaboration and leadership in complex care situations. These emphasize leadership in compassionate care, innovation adoption, and patient-centered service paradigms. Several studies have focused on leadership in service-oriented areas such as finance, IT, hotel, and retail [,,]. These often look at CSR, branding, digital transformation, or sustainability-focused innovation in competitive business environments.

Other studies have focused on the creative industry, including textile design, cultural entrepreneurship, and storytelling [,,]. These studies examine how creativity and value-based design can foster sustainable innovation and community engagement. A few studies study food systems, fisheries, or agriculture, frequently with an emphasis on supply chains, rural innovation, or micro-enterprises [,,]. These are relevant to understanding leadership in informal or small-scale sustainability transformations.

To provide complete traceability of the synthesis process, Appendix A (Table A1) includes an extraction matrix tying each study to its topic cluster (as determined by VOSviewer) and quality assessment.

4.2. Leadership Styles and Learning Mechanisms

In the face of unforeseen situations, leaders who possess a comprehensive awareness of the various scenarios that could occur in the future can effectively communicate their vision and aspirations to others, particularly their employees. This is an essential skill to guarantee efficient personnel management at any time, but particularly in times of uncertainty [].

The analysis of the literature reveals a diverse range of leadership styles employed in the context of collaborative learning and organizational sustainability. The most frequent leadership styles include ethical, genuine, participative, collaborative, transformational, distributed, enabling, and visionary, each of which contributes distinctively to how businesses structure learning and engage with internal and external stakeholders. For example, Abratt and Kleyn [] emphasize the importance of ethical leadership in fostering stakeholder co-creation through internal ethics training, corporate social responsibility (CSR) communication, and staff engagement. Altunay et al. [] examine how change leadership promotes learning through collaborative decision-making, teacher development groups, and participatory methods. Meanwhile, Hatlie et al. [] show the important role of engaged leaders.

Similarly, Amoako et al. [] emphasize the importance of authentic leadership, which is founded on self-awareness, transparency, and a solid moral foundation, as a catalyst for feedback-based learning in organizational contexts. The research also highlights the increasing importance of co-creation and distributed leadership paradigms. Herth et al. [], Hofstad et al. [], and Vedeld [] view leadership as a collaborative, multi-actor process that facilitates cross-sectoral learning via stakeholder mapping, boundary-spanning platforms, and collaborative design processes. These styles are especially well-suited to learning mechanisms, including design thinking, scenario planning, developmental evaluation, and stakeholder involvement, all of which help to co-develop long-term solutions in dynamic situations.

Innovative leadership styles, such as community-based and empowerment-oriented leadership [], collaborative systems leadership [], and network-based gender-equal leadership [], emerge as accelerators of inclusive learning ecosystems. These initiatives use reflective discourse, peer exchanges, games, and workshops, and co-created strategy training to promote mutual learning and organizational transformation. Overall, the research shows a clear shift from hierarchical and transactional leadership to more inclusive, situational, adaptive, and multilevel leadership styles. These leadership styles not only encourage organizational learning but also facilitate the development of collaborative capacities that align with SDG 17, which emphasizes partnerships for the Goals. By empowering different actors, such leadership approaches foster conditions conducive to innovation, shared learning, and sustainable transitions.

The literature demonstrates a comprehensive approach to sustainability, including environmental preservation, climate action, social inclusion, innovation ecosystems, and organizational transformation. Throughout literature, sustainability is viewed as an embedded strategy objective, frequently linked to the Triple Bottom Line, which encompasses social, environmental, and economic dimensions and is increasingly informed by the Sustainable Development Goals. Several contributions emphasize ecological sustainability, especially in healthcare, urban planning, and manufacturing. Barber et al. [] present a strategy framework for low-carbon learning health systems that combines leadership development, digital tools, and policy change to promote climate resilience.

Österblom et al. [] outline a governance innovation process in ocean stewardship, which includes shared sustainability targets and corporate environmental accountability. Other studies focus on social sustainability and equity. Changha et al. [] and Cheruiyot and Venter [] investigate how leadership and learning mechanisms improve employee well-being, participation of marginalized communities, and community-driven innovation. Echaubard et al. [] demonstrate that community-led participatory processes can yield socially innovative health solutions, such as localized dengue control systems and redesigned health curricula.

Organizational sustainability and transformation are also common topics, particularly in post-pandemic contexts and industries experiencing digital and systemic change. Amoako et al. [] and Rauniar and Cao [] demonstrate how authentic leadership improves strategic agility and operational sustainability by utilizing feedback-based learning mechanisms. Chatterjee and Chaudhuri [] highlight the significance of absorptive capacity and human–machine collaboration in developing robust and sustainable supply chains in the Industry 5.0 era.

Urban and Regional Development Studies by Menny et al. [], Trivellato [], and Vedeld [] show how smart cities and compact urban forms are being used to enhance sustainability through participatory planning, low-carbon mobility, and green growth. However, implementation remains unequal, with considerable differences in greenhouse gas reductions and citizen engagement levels between cities.

Importantly, several studies (e.g., Sica et al. []; Valentine et al. []) focus on sustainability innovation in creative and entrepreneurial ecosystems, identifying learning models that promote local development, inclusive entrepreneurship, and socially embedded design processes, such as e-textiles and circular fashion. Leaders need to build, and rely on, social capital, i.e., social structures and resources, internal and external to the organization, which allow them to facilitate responsible action []. All these contributions have both quantitative and qualitative effects, including enhanced organizational resilience, increased stakeholder involvement, policy changes, capacity-building, and, in some cases, measurable reductions in emissions or improvements in user participation. While conceptual frameworks and theoretical models remain important, several studies go beyond theory to demonstrate the practical implementation of leadership-enabled learning mechanisms that drive sustainable shifts.

The leadership styles discussed in this section —namely, participative, collaborative, and distributed —mirror the conceptual core of Clusters 1 and 4 in Figure 4. Cluster 1 focuses on the institutional and strategic underpinnings of sustainable leadership, whereas Cluster 4 emphasizes co-creation, collaboration, and learning as transformational methods. Together, these clusters demonstrate leadership’s dual character as a structural force and a learning process. The following Section 4.3 expands on this relationship by investigating how these leadership processes manifest across empirical studies and tracing their impact on innovation, trust, and sustainability outcomes.

Figure 4.

Keyword co-occurrence map processed in VOSviewer (https://tinyurl.com/25wbf7ju accessed on 2 June 2025). Source: Authors’ elaboration based on Scopus data (2025).

As shown in Figure 4, the different colors represent the VOSviewer-generated clusters: red for Cluster 1 (innovation and knowledge), green for Cluster 2 (awareness and participation), blue for Cluster 3 (health systems and adoption), yellow for Cluster 4 (co-creation and learning), and purple for Cluster 5 (health and crisis).

4.3. Synthesis of Empirical Findings on Leadership, Learning, and Sustainability

A recurring issue in the literature is leadership’s facilitating role in bridging institutional differences, promoting stakeholder co-creation, and driving systemic change. Abratt and Kleyn [] argue that ethical leadership, when linked with stakeholder co-creation, is critical in developing conscientious and sustainable business branding. Similarly, Altunay et al. [] found that change leadership has a positive impact on organizational processes, including teacher development, parental engagement, and the overall school atmosphere. Amoako et al. [] highlight the role of authentic leadership, demonstrating its mediating effect between sustainable strategies, thus confirming the value of leadership traits, such as transparency and moral integrity, in organizational responsiveness.

Several studies have emphasized the importance of leadership in enabling inclusive and sustainable innovation. Hofstad et al. [] and Vedeld [] describe co-creation leadership as inherently participatory and trust-building, with the potential to mobilize urban climate action when supported by effective governance mechanisms. Barber et al. [] criticize the fragmentation of present healthcare systems and the suggestion of leadership-integrated learning health system (LHS) frameworks as a means of aligning care quality, environmental goals, and economic efficiency. Similarly, Echaubard et al. [] found that decentralized leadership and community ownership promote behavior change and social innovation in public health efforts.

Other research, such as that by Drutchas et al. [], demonstrates that storytelling-based leadership improves empathy, engagement, and clinician well-being. Meanwhile, Snyder et al. [] argue that such reflective leadership practices help break down hierarchical boundaries and cultivate a leader’s identity. In the creative and cultural sectors, Sica et al. [] demonstrate that leadership is crucial in remarkably fostering social innovation, cross-sector collaboration, and sustainability resilience, when grounded in participatory learning ecosystems.

Furthermore, leadership is typically cited as a driver for overcoming complexity and ambiguity. According to Valentine et al. [] and Zhao et al. [], leadership promotes stakeholder involvement, strategy alignment, and adaptive cooperation, particularly in volatile or rural development environments. Notably, Ritchie-Dunham et al. [] and Voytenko et al. [] identify leadership’s ability to foster shared purpose and cross-sectoral learning as a strong enabler of sustainable transitions.

However, not all research shows uniformly beneficial results. According to Grüne et al. [] and Menny et al. [], contextual factors such as institutional preparedness, leadership capacity, and the stage of implementation can limit the impact of co-creation efforts. Some data also suggests a paradox: entities that require collaborative leadership often have the least competence to implement it effectively []. In conclusion, the data support the primary assumption of this review: leadership, when oriented toward collaboration, inclusivity, and co-creation, serves as a transformative driver of learning and sustainability [,,]. It empowers various actors, promotes innovation, and aligns organizational processes with long-term sustainability objectives.

To improve synthesis traceability, each theme interpretation in this section was clearly linked to the studies described in the extraction table as well as the bibliometric clusters constructed using VOSviewer (Figure 4). Clusters 1 and 4 revealed repeating linkages between leadership, cooperation, and sustainability, with a focus on participatory processes, innovation, and learning.

4.4. Integrating Collaborative Learning and Innovation with Employee Well-Being

A corporation that prioritizes social sustainability and employee purpose increases stakeholder trust and employee commitment, which are linked to individual and communal well-being []. Green leadership fosters staff morale, well-being, and engagement, and green consumer behaviour promotes community well-being and social sustainability []. It emphasizes participative decision-making, ethical leadership that fosters innovation, and strong labor relations for community sustainability []. In the same line, communities and individuals are encouraged to actively interpret their lives and play a crucial role in coming up with innovative solutions to the health issues they encounter through social innovation [,]. Furthermore, gender equality promotes resilience, democracy, inclusion, and collective well-being []. Leaders can inspire followers to achieve communal values and aspirations, sacrifice egocentric interests and goals, as well as elicit and manage emotions to encourage others []. The findings emphasize the importance of trust and providing opportunity for individuals with the necessary competences to lead in a participatory and distributive manner, while dealing with limited human and financial resources []. Matti et al. [] emphasize the need for a new social contract backed by democratic government and developing communities, supporting cross-actor interaction. Waste management initiatives, on the other hand, raise public awareness, increase income, and promote community well-being [].

Within schools, leadership practices are linked to long-term school improvement and resolving disparities, both of which indirectly boost student and teacher well-being []. The ‘third mission’ of universities contributes to the quality of life and social well-being of local communities []. Living labs promote a positive work environment, encourage co-creation and cooperation, and help identify enabling elements. providing specialized assistance for stakeholders while emphasizing flexibility to local situations [].

Although multiple studies have found positive correlations between leadership styles, collaborative learning, well-being, and organizational culture, new data suggest that these relationships are not always constant. Different leadership techniques may create different outcomes depending on the leader’s personal characteristics, follower dynamics, and organizational situations. For example, Riggio et al. [] define ethical leadership as virtue-based, with prudence, justice, temperance, and fortitude serving as drivers of trust and moral integrity. In contrast, Sy, Horton, and Riggio [] define charismatic leadership as an emotion-driven process that can have both positive and negative consequences depending on how leaders elicit and channel followers’ moral feelings.

More recently, Riggio et al. [] stated that leadership and followership are interconnected processes, implying that the efficacy of leadership behaviors is heavily reliant on follower involvement and accountability. These opposing findings are consistent with Peterson and Seligman [], who argue that each individual’s performance reflects a distinct set of character strengths and weaknesses influenced by contextual and cultural factors. This corpus of studies suggests that leadership effectiveness cannot be generalized and must be understood as a dynamic interplay of ethical character, emotional influence, and follower participation within distinct organizational and cultural contexts.

These results showed that collaborative and values-driven leadership has the potential to generate similar learning mechanisms in different institutional contexts, albeit in different sectors. In education, participatory leadership enhances continuous learning, in business organizations, it fosters innovation and further engagement of stakeholders, while in healthcare systems, sustainable leadership supports ethical decision-making and group well-being. These patterns correspond to Clusters 2 and 4 of the VOSviewer analysis, where the themes of social sustainability, participation, and learning are closely linked. These results also have a partial overlap with Cluster 3, where an interplay between leadership, policy implementation, and healthcare practices is shown.

4.5. Suggestions for Future Research

The necessity of validating and expanding current models across various contexts and geographical areas is one of the most often mentioned themes. Research should be expanded to Sub-Saharan Africa, Southeast Asia, the Balkans, coastal regions, and urban areas, according to several studies that point out the drawbacks of evaluating leadership and sustainability frameworks in a single nation or industry [,,]. The socioeconomic, institutional, and cultural contexts all depend on this extension.

Many authors stress the importance of using sophisticated methodological techniques, such as international comparative studies, mixed-methods research, and longitudinal designs [,,]. Unlike merely descriptive or single-case studies, these methods are essential for establishing causal relationships and evaluating the long-term effects of leadership interventions.

Many studies advocate for a better understanding and empirical comparison of leadership styles, including Adaptive Leadership Theory, transformational leadership, and co-creative governance models [,]. There is a distinct void in our understanding of what enables or constrains collaborative leadership in complex systems, as well as a scarcity of evidence on the specific activities leaders must undertake to promote sustainability across governance traditions.

Another common theme is the need for a more in-depth analysis of cross-sectoral collaboration, particularly among public, private, and civil society stakeholders. Several studies propose examining the long-term impact of co-creation, value-based innovation, storytelling, textile design, and community-led innovation on achieving sustainability goals [,,].

Several authors suggest exploring the role of digital technologies, such as AI, gamification, digital transformation, and collaborative platforms, in 86 performance indicators (KPIs) and frameworks to assess cultural shifts, transformational change, and institutional learning. Without such tools, it is difficult to scale or repeat effective initiatives.

The study of 33 evaluated publications demonstrates that the field of leadership for sustainability is steadily expanding. However, it still faces obstacles in geographic representation, methodological rigor, conceptual development, and digital integration. These prospective research initiatives provide critical avenues for improving the theoretical and practical foundations of sustainable leadership in an increasingly interconnected and complex world.

5. Discussion

Before we can draw any meaningful conclusions that may be of value to stakeholders regarding appropriate leadership practices and other collaborative mechanisms that lead to sustainability, it is essential to address cultural issues. A closer look at studies from different cultural and institutional contexts reveals that national cultural values have a significant impact on so-called leadership outcomes. Clear cultural differences that contribute to the explanation of differences in leadership effectiveness and behavior are revealed by the analysis of the evaluated studies. According to studies conducted in South Africa and Ghana, leaders often use community-focused and values-oriented strategies to maintain group harmony and motivation within organizations. This approach reflects collectivist tendencies and significant power distance. In these cultures, green leaders promote social responsibility principles such as community engagement and fair labor standards, which have a positive impact on society []. As seen in South Africa, leadership in community-based social enterprises is “often co-constructed through social interactions, enabling effective collaboration and community engagement” [], which is a participatory and value-driven model that fits with collectivist cultural norms.

Similarly to this, research from Turkey, especially in educational settings, highlights change-oriented and participative leadership methods that foster teamwork while upholding hierarchical respect. This hybrid approach is influenced by cultural norms surrounding authority and unity. Studies from North American and European contexts, such as the Netherlands and Canada, on the other hand, place a strong emphasis on autonomy, shared decision-making, and innovation values that are in line with high individualism and low power distance.

These results are consistent with Hofstede’s [] cultural dimensions, indicating that power dynamics, cultural norms, and how authority and participation are expressed across cultures have a significant impact on collaborative learning processes and leadership effectiveness.

Developing countries must become producers of “local” knowledge and incorporate contextually appropriate solutions into their organizational development efforts []. However, worldwide best practices for critical engagement and globally oriented programs, such as the Sustainable Development Goals, play a significant part in sustainability efforts.

A particular focus of studies in these countries has been on education and the role of leadership in the collaborative learning and innovation process. Findings indicate that promoting change leadership facilitates collaboration, equity, and inclusion, empowering stakeholders to engage with traditional practices and create a more equitable educational landscape [].

The results of a study by Changha et al. [] in the Ugandan hospitality industry, point to a connection between complex adaptive leadership, improved social sustainability practices, and stakeholder value co-creation. It is very important that within the formal control system, complex adaptive leadership is enabled, embedded in spaces of interaction between different employees and ideas, further enabling the generation of sustainable ideas from lower-level employees. Another study in a developing country reveals that most leaders emphasize the importance of involving community members in the design and implementation of projects, or through collaborative decision-making, and highlight the necessity of rapid adaptation to anticipated and unforeseen changes within their environment [].

Furthermore, a study conducted by Huang and Liu [] show a significant impact between empowering leadership and employee behavior in the context of developing innovation, value co-creation, participation in decision-making, competitive advantage, and sustainability knowledge.

Developing countries face numerous challenges that hinder universities’ vital role as centers for sustainability. Many higher education institutions have temporarily closed or reduced services; some have halted operations due to a lack of preparedness to offer distance education, while others have struggled to maintain a program offering that resembles traditional face-to-face instruction []. On the other hand, the study by Tsai et al., [] conducted in Vietnam, reveals that stakeholder participation, tourism activities, and the political and legal framework are causal attributes for achieving sustainable performance in waste management.

In contrast to the situation in developing countries, studies from developed economies reveal several different dynamics in the implementation of sustainability and leadership in circular practices. In most cases, the problem is helped by stronger institutional infrastructure, more stable financing mechanisms, and more advanced technologies.

Sustainability leadership is frequently more officially incorporated into governmental policies and corporate governance in industrialized nations. With an emphasis on innovation, sustainability, and stakeholder co-creation, studies from countries such as the US, Canada, Switzerland, and Germany suggest that sustainability-oriented leadership often aligns with broader strategic objectives. For example, sustainability in co-working spaces in Germany is promoted through community-oriented leadership, emphasizing knowledge sharing and collaborative design []. In Canada, in healthcare settings, participatory leadership models encourage inclusive decision-making and environmental scanning to adapt to societal needs [].

Furthermore, higher education institutions in developed countries demonstrate greater resilience to crises, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, by enabling a rapid transition to digital platforms and maintaining the continuity of sustainability-oriented programs. Universities in these countries also benefit from greater academic autonomy, ongoing funding, and institutionalized partnerships with industry, which support long-term sustainability goals.

Unlike in many developing countries, where leadership often must compensate for structural deficiencies, in developed economies, leadership typically acts as a catalyst for continuous improvement in well-established systems. These environments allow leaders to focus not only on immediate sustainability outcomes but also on shaping future-oriented circular innovation models through data-driven approaches, green procurement policies, and advanced monitoring tools. The literature gap highlights the need to adapt institutional design, employ innovative methods, and foster leadership development to address the distinct social and economic needs of each country. Although there are universal lessons to be learned, effective circular economy and sustainability strategies need to be context-specific.

It is multidimensional, comprising traditional knowledge (handed down through generations), empirical expertise (based on observation and practice), and revealed wisdom [].

Despite the growing trend of publications reviewed in this study, we must be cautious in interpreting and generalizing them to understand leadership, collaborative learning, and well-being. Many of the studies reviewed have a positivist approach and rely on survey-based methodologies and standardized constructs to simplify complex social interactions. But this approach often ignores the contextual, cultural, and interpretive elements that differentiate these phenomena. In contrast, qualitative contributions are limited and usually fragmented, limiting our ability to generate deeper insights into the processes of meaning-making, meaning-giving, and relationality through which leadership and collaboration occur. The literature still favors Western paradigms and managerial assumptions about rationality, effectiveness, and performance. As a result, future research should adopt more comprehensive and critical epistemologies, such as interpretive, constructivist, and critical realist approaches, to better reflect the complexity and situational character of sustainability leadership.

Unlike previous systematic studies of the literature, it brings together three concepts that, although studied separately, together provide a more complete understanding of organizational behavior. Although leadership, collaborative learning, and well-being have been studied separately by several authors, bringing all three elements together in different contexts and from different perspectives further deepens knowledge in this field. Furthermore, this study also opens other avenues of discussion for future research.

6. Theoretical and Practical Implications

The fields of leadership, organizational learning, and sustainability will all be significantly impacted by this work, both theoretically and practically. First, it advances knowledge of how various leadership philosophies, particularly transformational, collaborative, and ethical leadership, support organizational sustainability through cross-sector learning and participatory innovation. The proposed conceptual framework builds upon the existing literature by linking leadership attributes to collaborative processes and sustainable development goal (SDG) aligned organizational transformation. This contributes to theory by connecting previously disparate research streams on leadership, learning, and sustainability.

This research shows that leadership is not just a driver of sustainability and innovation, but also an important enabler of employee and community well-being. Effective leadership techniques that emphasize inclusivity, reflection, and co-creation foster environments where motivation, resilience, and shared learning coexist with sustainability goals.

From a practical standpoint, the results underscore the importance of companies having inclusive leadership capabilities to foster psychological safety, stakeholder engagement, and systems thinking. Organizations should invest in leadership development programs that promote contemplation, ethical decision-making, and adaptability. Human resource managers ought to allocate sufficient funds for training and education in sustainable leadership [].

Talent management procedures can be examined in relation to leadership capacity building to see whether screening procedures and instruments are current []. The best course of action would be to establish core talent pools and find applicants who can spearhead sustainable innovation.

Organizations should engage in leadership development programs that prioritize collaboration, co-creation, and trust. These programs can improve team communication, problem-solving skills, and foster experimentation. Managers may boost employee enthusiasm, organizational resilience, and adaptation to change by creating learning environments that are shared and supported.

Third, the research argues that CEOs play a critical role in linking sustainability goals to company strategies. Managers can put sustainability principles into action by incorporating collaborative learning sessions into project planning, forming cross-sector partnerships, and embedding SDG-related objectives (particularly SDG 17—Partnerships for the Goals) into organizational frameworks.

The research argues that public policy should support leadership models that go beyond hierarchical control in favor of collaborative governance approaches, especially in complex and cross-sectoral sustainability programs. Policymakers can also benefit from implementing leadership-enabled learning ecosystems into urban planning, education, and public health policy to boost resilience and innovation.

In education, particularly in sustainability issues. Additionally, the corporate sector can enhance its governance, social, and environmental performance, gain a competitive edge, and foster stakeholder trust by implementing co-creative leadership strategies. To support the rising trend of incorporating leadership development programs into the curriculum, the sustainability of leadership development program outcomes in various contexts can be investigated [].

7. Conclusions, Limitations, and Future Research

This literature review concludes that leadership plays a crucial role in collaborative learning, driving long-term change across sectors. Collaborative, ethical, and visionary leadership styles not only enhance stakeholder co-creation and organizational agility but also facilitate the link between business strategy and the Sustainable Development Goals, particularly SDG 17 (Partnership for the Goals).

In the studies reviewed, collaborative leadership has been highlighted as a key mechanism that promotes learning-oriented behaviors, such as shared reflection, open and transparent communication, and peer mentoring. These techniques not only encourage and enhance information transfer and creativity but they also promote psychological well-being by instilling a sense of belonging and purpose in employees.

Leadership that promotes innovation fosters learning environments while simultaneously stimulating reflection, thereby significantly contributing to the generation of long-term value and further social inclusion. However, realizing this potential would require a shift in traditional concepts of leadership away from command-and-control systems and toward collaborative, participatory ones. This is particularly important in today’s uncertain, complex environment, where this collaborative capacity can provide a competitive advantage.

Co-creation leadership is a natural participant in building trust, with the potential to mobilize multiple initiatives when supported by effective governance mechanisms.

Leadership is commonly cited as a catalyst for overcoming complexity and ambiguity that promotes stakeholder engagement, strategy alignment, and adaptive collaboration, especially in volatile environments.

In a company where leaders are collaborative, social sustainability and employee purpose are prioritized, increasing stakeholder trust and employee engagement. This emphasizes participatory decision-making that fosters innovation and strong working relationships for community sustainability. Findings highlight the importance of trust and providing opportunities for individuals with the necessary competencies to lead in a participatory and distributive way, while facing limited human and financial resources.

The conclusions of this analysis have various practical implications for managers and organizational leaders.

First, the findings indicate that collaborative and participative leadership styles are critical for promoting long-term organizational learning, creativity, and employee well-being. Managers should shift away from hierarchical “command-and-control” methods and toward inclusive ones that allow employees to participate in decision-making, share knowledge, and engage in reflective discourse.

Finally, given resource restrictions in many poor countries, managers should promote low-cost but high-impact collaborative activities, including peer mentorship, shared reflection meetings, and community-based innovation projects. These acts can enhance social sustainability and foster a culture of continual development that is consistent with organizational values.

Beyond the contributions, this study has several limitations that should be considered. First, it is a fact that there is no primary data, and it is entirely based on a review of publications in the field of study, only in the Scopus database, which may have excluded relevant studies indexed in other databases such as Web of Science or Google Scholar. Second, the apparent methodological diversity between studies in different countries and contexts is another limitation that limits the generalizability of the data. Third, it is challenging to assess the long-term impact of leadership on sustainability performance, as most existing research lacks standard measurements and longitudinal designs.

The relationship between leadership, collaborative learning, and resilience has been well-studied in the past; however, by examining underappreciated aspects and employing new analytical techniques, future studies could expand on what is already known. Examining the psychological and emotional aspects of leadership in resilience transitions is an interesting avenue. Although structural and behavioral frameworks are often used to describe leadership, little is known about the emotional resilience, ethical reasoning, and cognitive framework of leaders negotiating the uncertainty associated with resilience. Research could examine how moral courage and emotional intelligence influence leaders’ ability to inspire group effort and maintain commitment during prolonged organizational change. The function of informal leadership and networks of influence within organizations is another unexplored area. Informal actors, such as community champions, frontline workers, or peer influencers, can be crucial in promoting sustainable learning and innovation, despite the considerable attention given to formal leadership styles and top-down tactics. Social network analyses or ethnographies can reveal how informal leadership dynamics can support or challenge formal structures, particularly in grassroots movements or mission-driven organizations.

The power imbalances and moral conflicts that might occur in cooperative invention processes should also be thoroughly examined in future studies. While co-creation is frequently portrayed as inclusive and democratic, the actual realities of involvement might include gatekeeping, elite capture, or the silencing of underrepresented perspectives. Investigating how leadership might encourage or challenge such processes would help to advance both leadership theory and sustainability practice.

Furthermore, studies could examine the intergenerational aspect of leadership for sustainability. As younger generations demand more accountability from organizations and become increasingly involved in sustainability actions, new forms of intergenerational discourse, mentorship, and co-leadership may emerge. Studying how these factors impact leadership roles and organizational learning during periods of transition would be pertinent and beneficial.

Future studies can also look at how leadership may promote well-being in resource-constrained environments, namely through mechanisms like collaborative learning, storytelling, and network-based leadership.

Lastly, it is essential to examine how leaders utilize symbolic actions and cultural narratives to support sustainability initiatives. Rituals, symbolic communication, and storytelling are all effective means of connecting stakeholders with sustainability goals and igniting organizational values. Gaining insight into how these intangible elements function in diverse sociocultural contexts could offer a more comprehensive and nuanced view of leadership for sustainable development.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su172210345/s1, Figure S1: PRISMA Checklist [].

Author Contributions

A.O. conceptualized the study, conducted the systematic literature review, and performed the data analysis. E.N. contributed to refining the research methodology and provided critical insights into the theoretical framework. A.O. and E.N. jointly wrote the main manuscript text. E.N. prepared the figures and tables. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Extraction Matrix Linking Articles, Thematic Clusters, and Quality Assessment.

Table A1.

Extraction Matrix Linking Articles, Thematic Clusters, and Quality Assessment.

| Keyword | Cluster (VOSviewer) | Leadership/Learning Focus | Main Conceptual Area | Quality Rating | Total Link Strength 1 |