From Fossil to Function: Designing Next Generation Materials for a Low Carbon Economy

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Quantification: We evaluate the lifecycle carbon burdens of conventional material systems and introduce metrics such as functional carbon intensity (kg CO2 per unit service delivered) to enable performance adjusted comparisons.

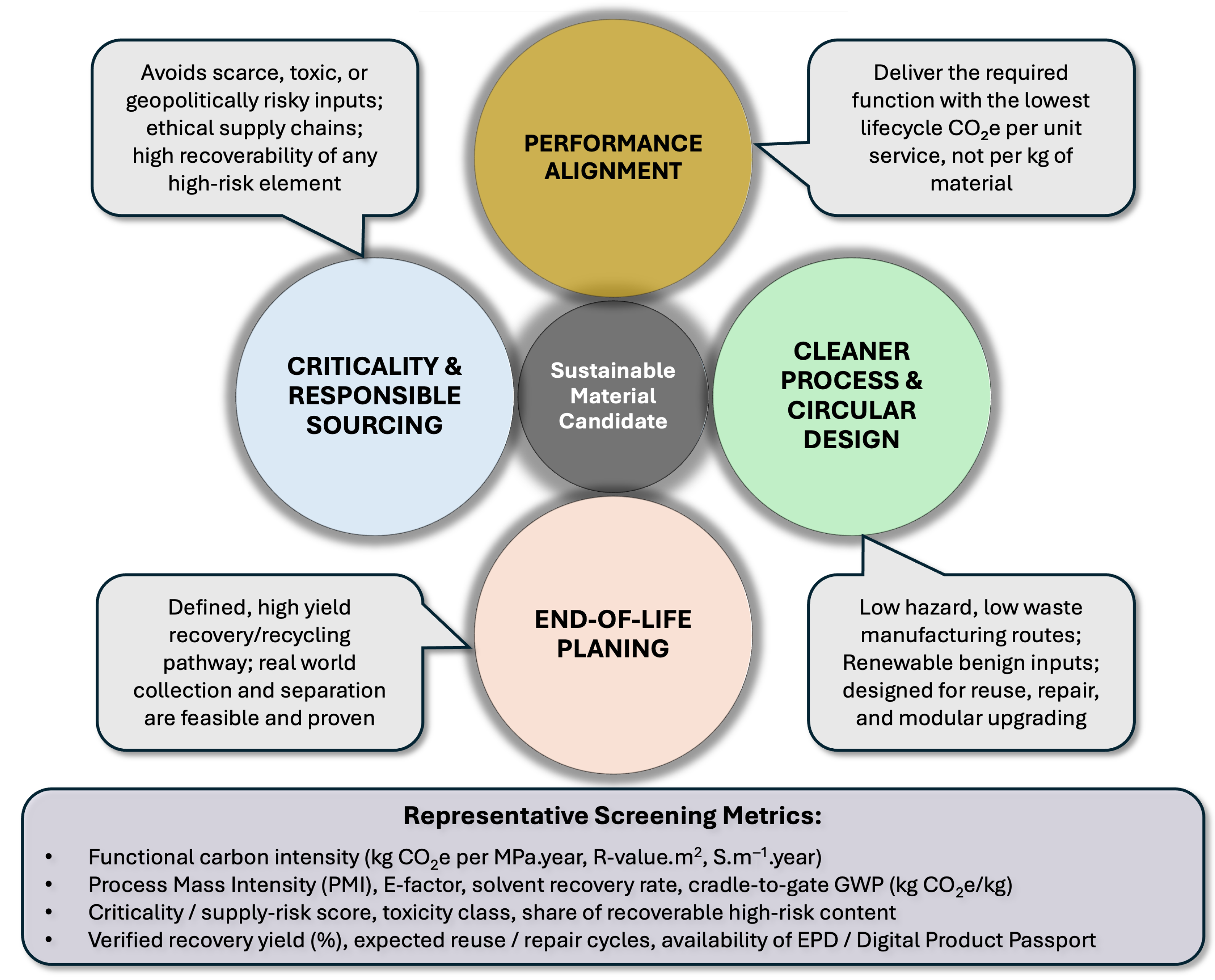

- Design Principles: We present four foundational principles for sustainable material design performance alignment, green chemistry and circularity, criticality and responsible sourcing, and end-of-life recovery, as a cohesive evaluation rubric.

- Implementation Levers: We assess tools and institutional levers that facilitate discovery and deployment, including AI/ML models, autonomous labs, lifecycle modeling, digital product passports, green procurement programs, and circular economy policies.

- Section 2 contextualizes the material sector within the global carbon budget and reviews lifecycle data for major material classes.

- Section 3 introduces our four principle framework and associated evaluation metrics.

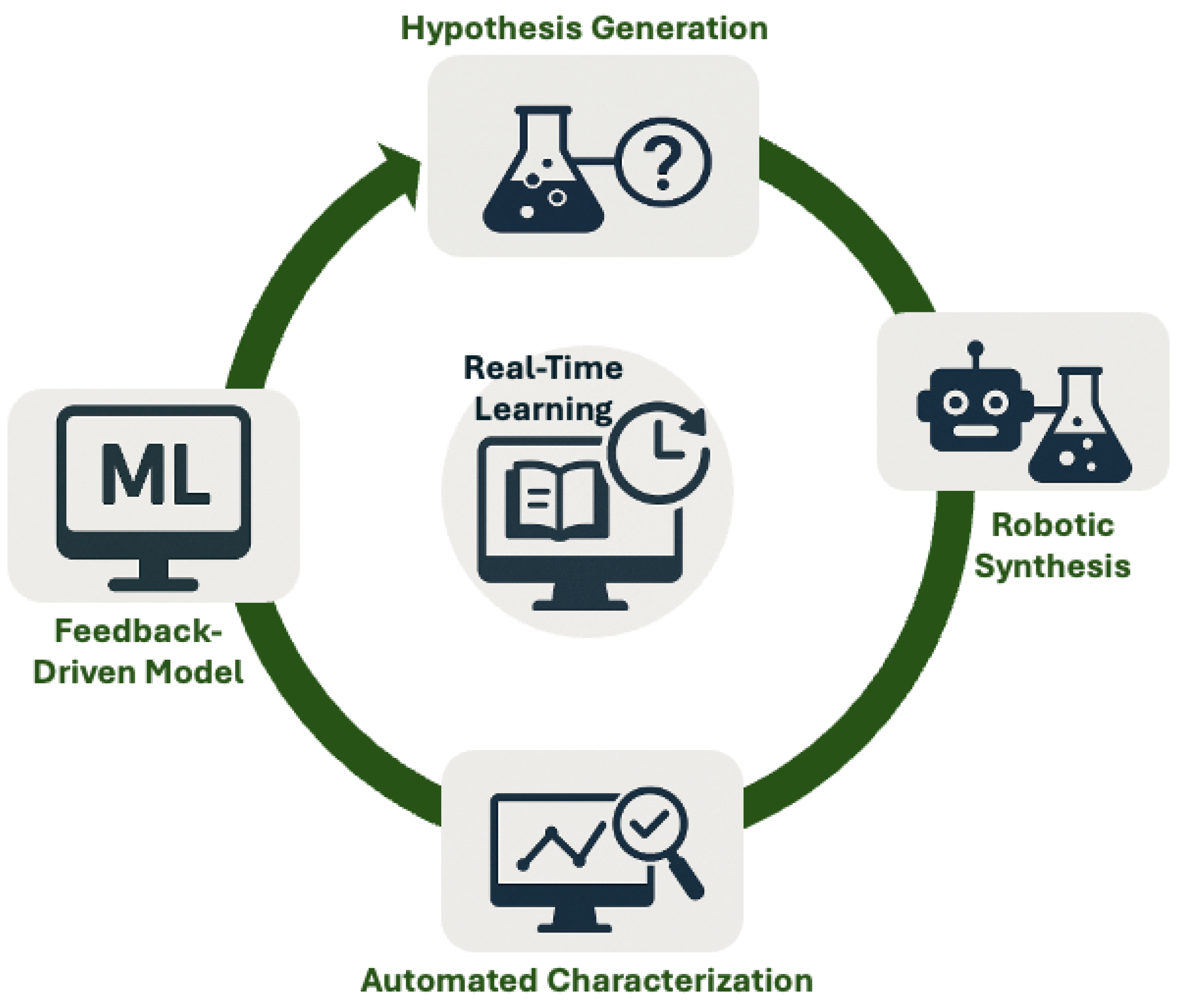

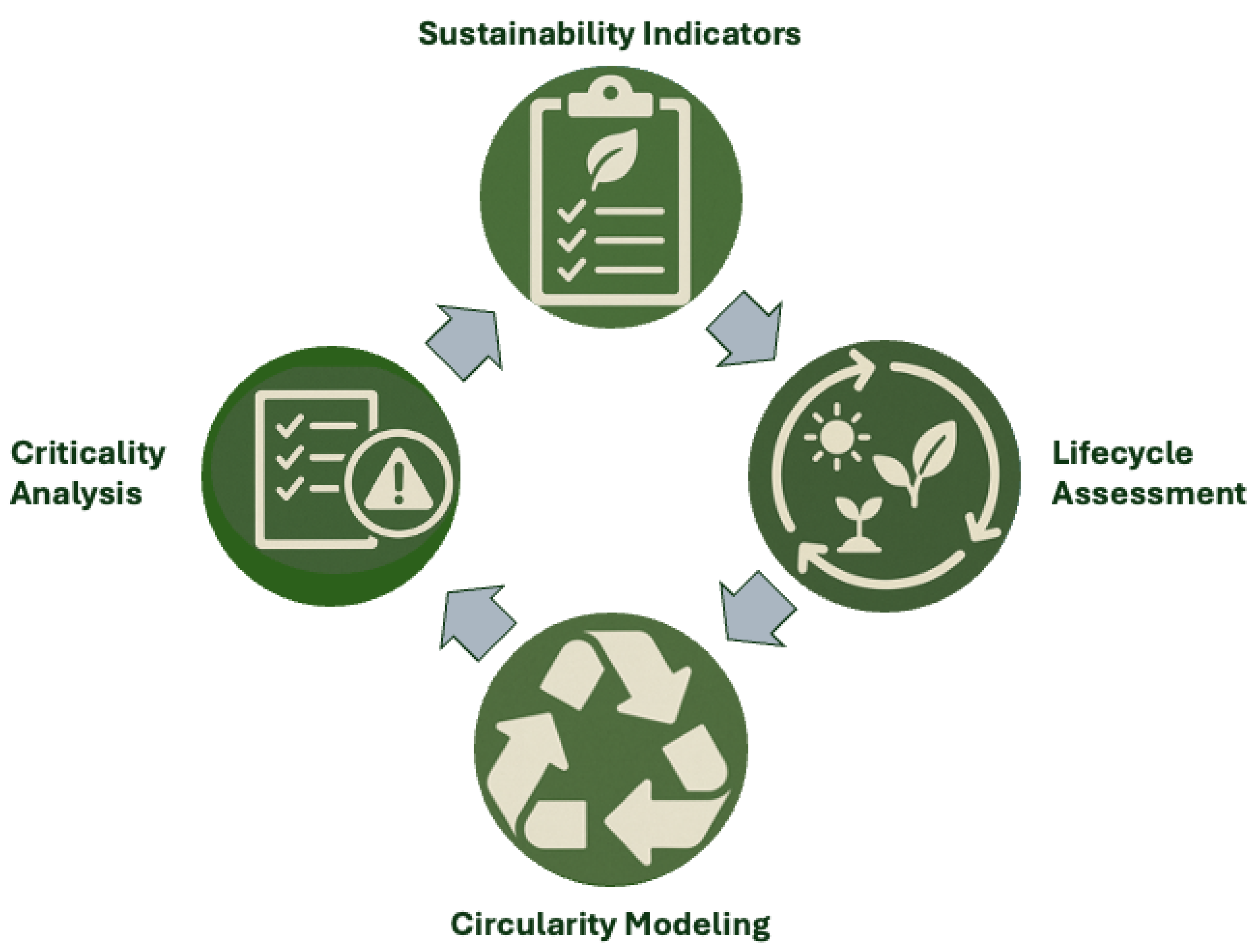

- Section 4 details computational and experimental tools accelerating sustainable materials discovery.

- Section 5 presents case studies across five key domains: construction, polymers, functional materials, textiles, and electronics.

- Section 6 explores enabling infrastructure, policy, and procurement mechanisms.

- Section 7 offers a forward looking roadmap and actionable recommendations for aligning material innovation with climate and sustainability goals.

2. The Role of Materials in the Global Carbon Budget

2.1. Embodied vs. Operational Carbon: A Shifting Balance

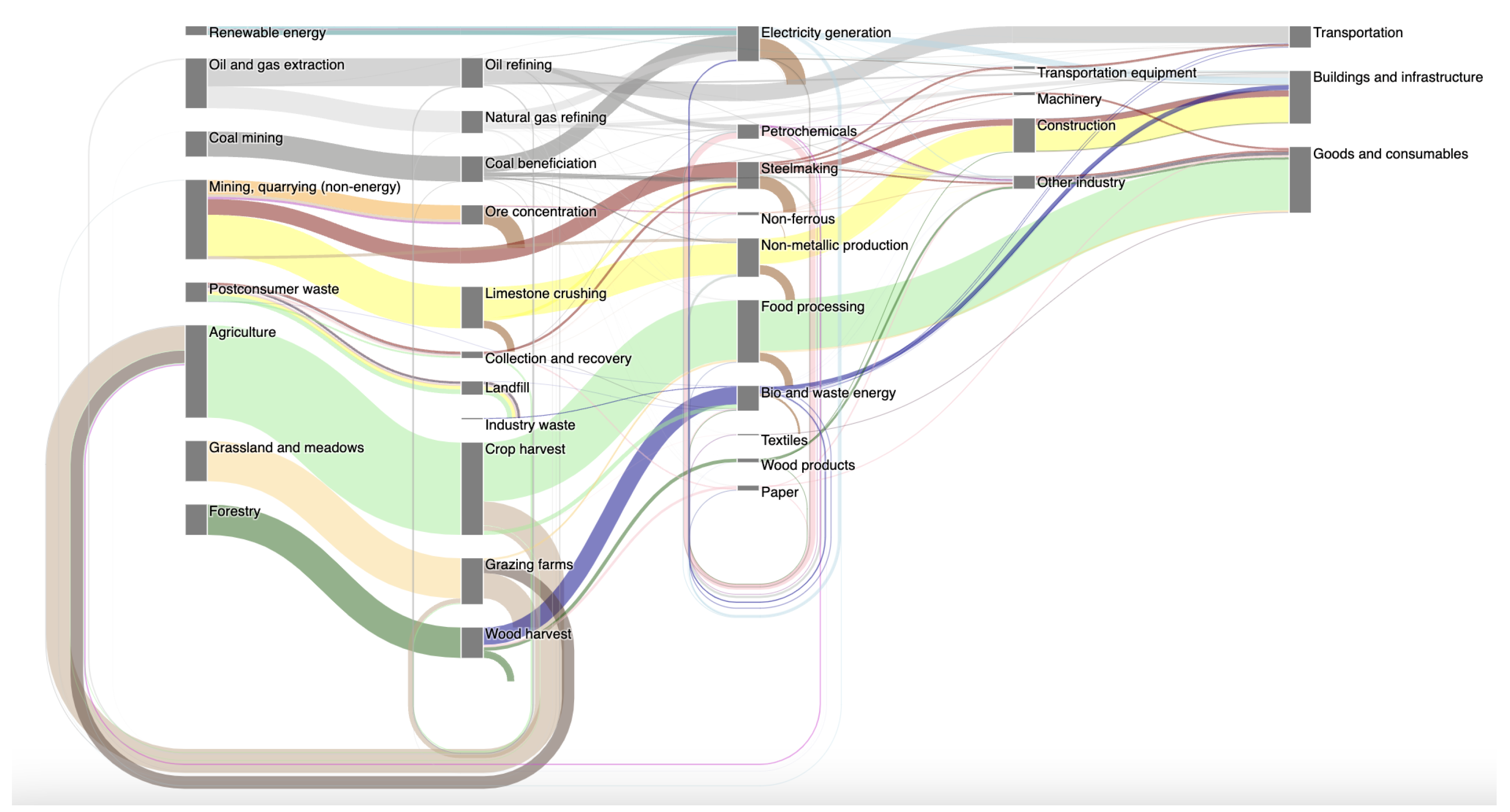

2.2. Sectoral Contributions of Materials

2.3. Lifecycle Metrics, Data Transparency, and Limitations

| Material | Embodied Carbon (kg CO2e/kg) | Recyclability (%) | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Portland cement | 0.5–0.6 | Low | IEA Cement KPI (2024) [29] |

| Steel (BF–BOF) | 2.1–2.4 | High | JRC (2025) [31] |

| Steel (EAF) | 0.6–0.8 | High | JRC (2025) [31] |

| Primary aluminium | 14.5–15.0 | Very High | IAI (2024) [32] |

| Recycled aluminium | 0.5–0.6 | Very High | IAI (2024) [32] |

| PET (plastic) | 2.2–2.7 | High | Kim et al. (2023) [33] |

| PLA (biopolymer) | 1.3–2.0 | Moderate | CE Delft (2023) [34] |

| Hempcrete | −0.04–0.0 | Moderate | Muhit et al. (2024) [47] |

3. Principles for Designing Sustainable Materials

3.1. Performance Alignment

3.2. Cleaner Process and Circular Design

3.3. Criticality and Responsible Sourcing

3.4. End-of-Life Planning and Recovery

4. Enabling Tools: Accelerating Discovery and Deployment

4.1. Machine Learning and Data Driven Screening

- Multi objective property prediction: Modern ML models including graph neural networks, attention based transformers, and message passing architectures simultaneously predict properties such as global warming potential, toxicity, mechanical strength, electrochemical stability, and synthetic complexity [108,109]. These models enable efficient navigation of sustainability performance trade offs.

- Inverse design and generative modeling: Generative techniques like diffusion models, VAEs, and language based design tools (e.g., MatGPT, ChemCrow) now propose novel molecules, polymers, or crystals optimized for degradability, abundance, or low embodied carbon [110,111]. These methods unlock vast chemical spaces with sustainability constraints pre imposed in the latent space.

- Active learning and uncertainty quantification: ML pipelines increasingly use Bayesian optimization, active learning, and ensemble modeling to maximize knowledge gain while minimizing resource use. These tools help prioritize data acquisition (via simulation or experiment) where uncertainty is high or sustainability impact is uncertain [112,113].

- Green optimization and sustainability aware ranking: Recent platforms integrate environmental and supply chain metrics directly into the screening process. For instance, GreenGNN and modified ALIGNN architectures have been extended to score candidates based on criticality indices, recyclability, and lifecycle carbon emissions [109,114].

4.2. High Throughput Experimentation and Autonomous Laboratories

4.3. Lifecycle Informed Materials Design (LIMD)

- Embodied carbon and cumulative energy demand,

- Water and land use intensity,

- Recyclability and biodegradability,

- Supply chain risk and ethical sourcing, and

- Human health and social equity indicators.

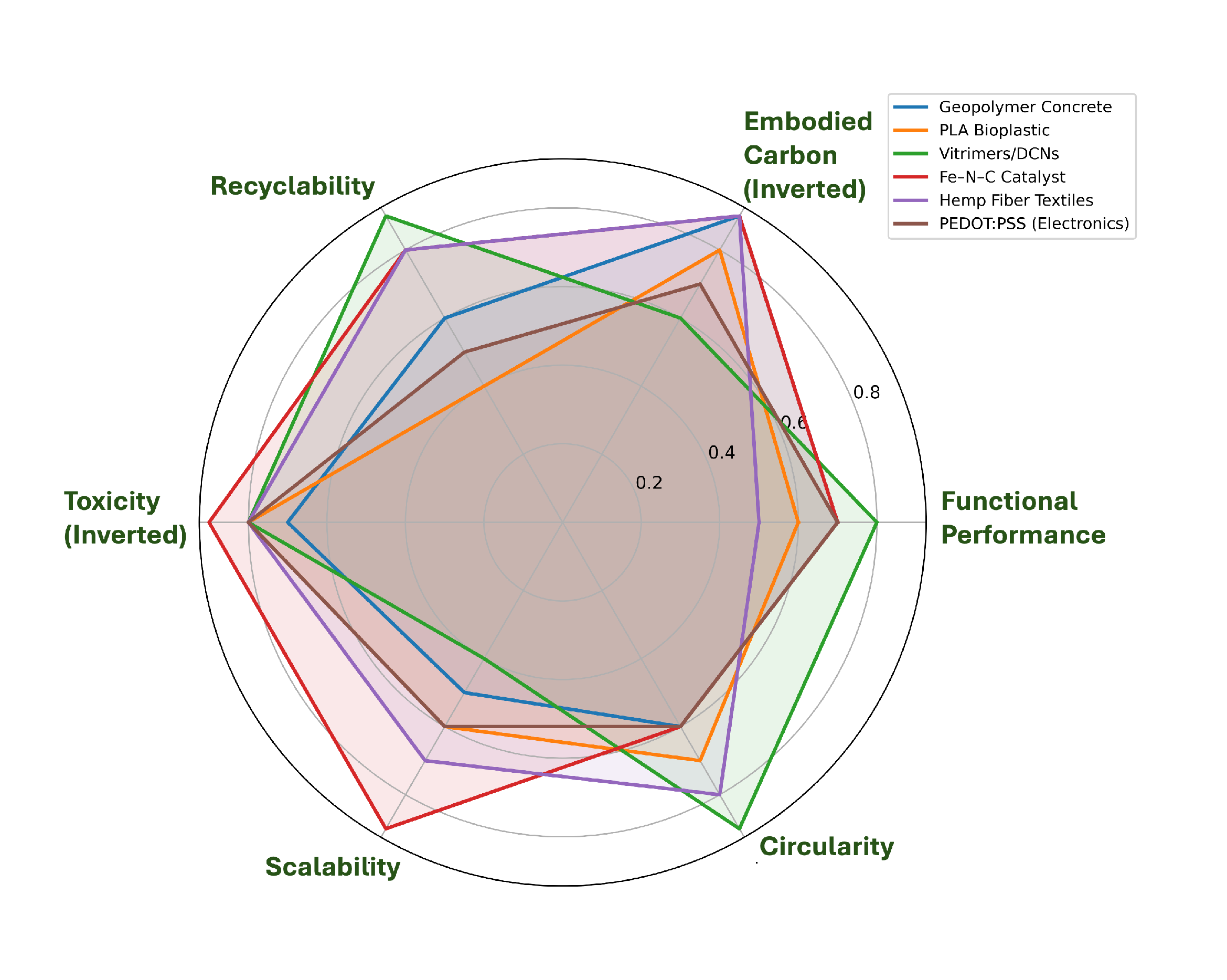

5. Examples of Next Generation Material Platforms

5.1. Low Carbon Construction Materials

5.2. Bio Derived and Circular Polymers

5.3. Functional Materials for Industrial Applications

5.4. Sustainable Textiles and Fibers

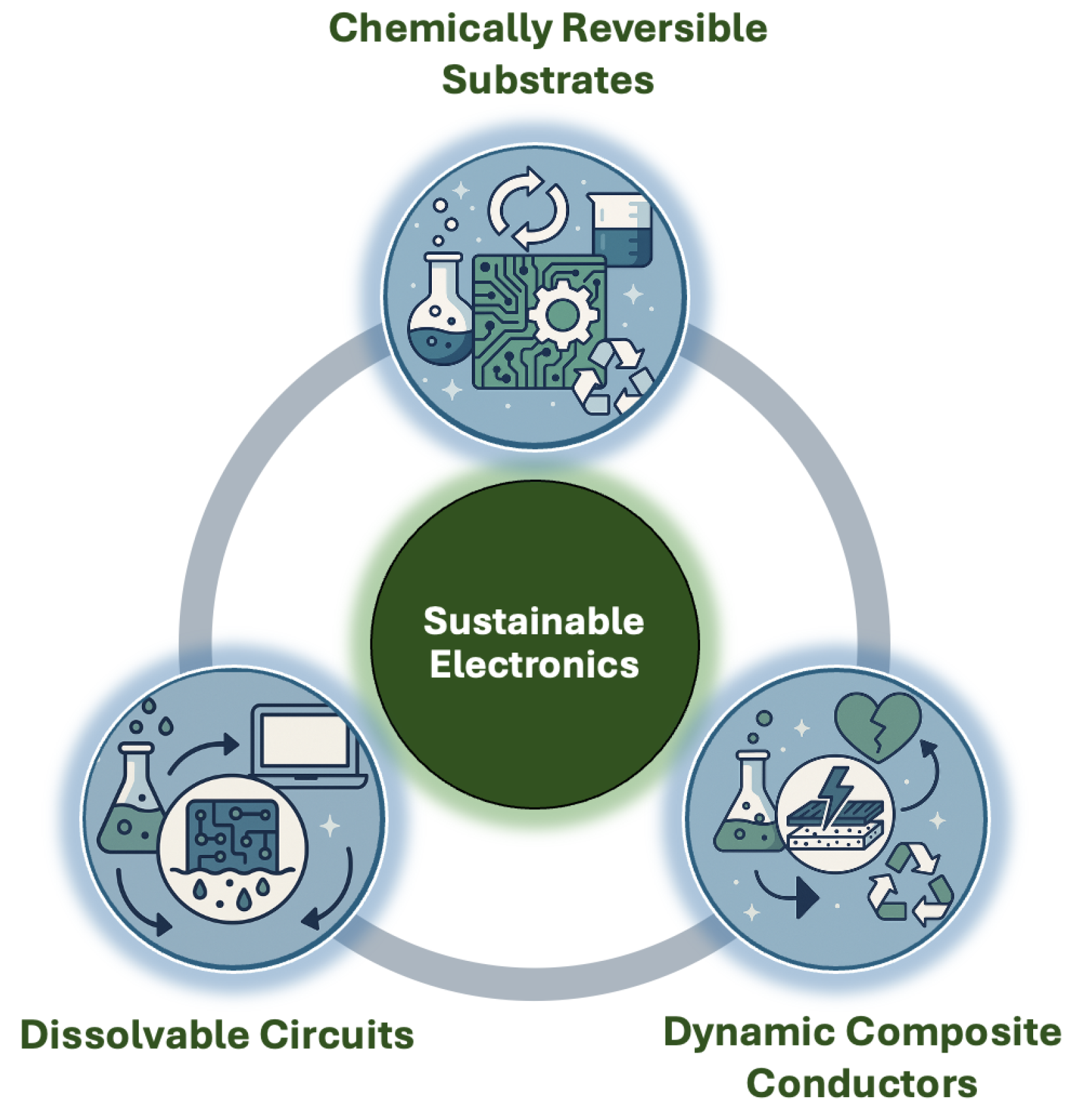

5.5. Electronics and Semiconductor Materials

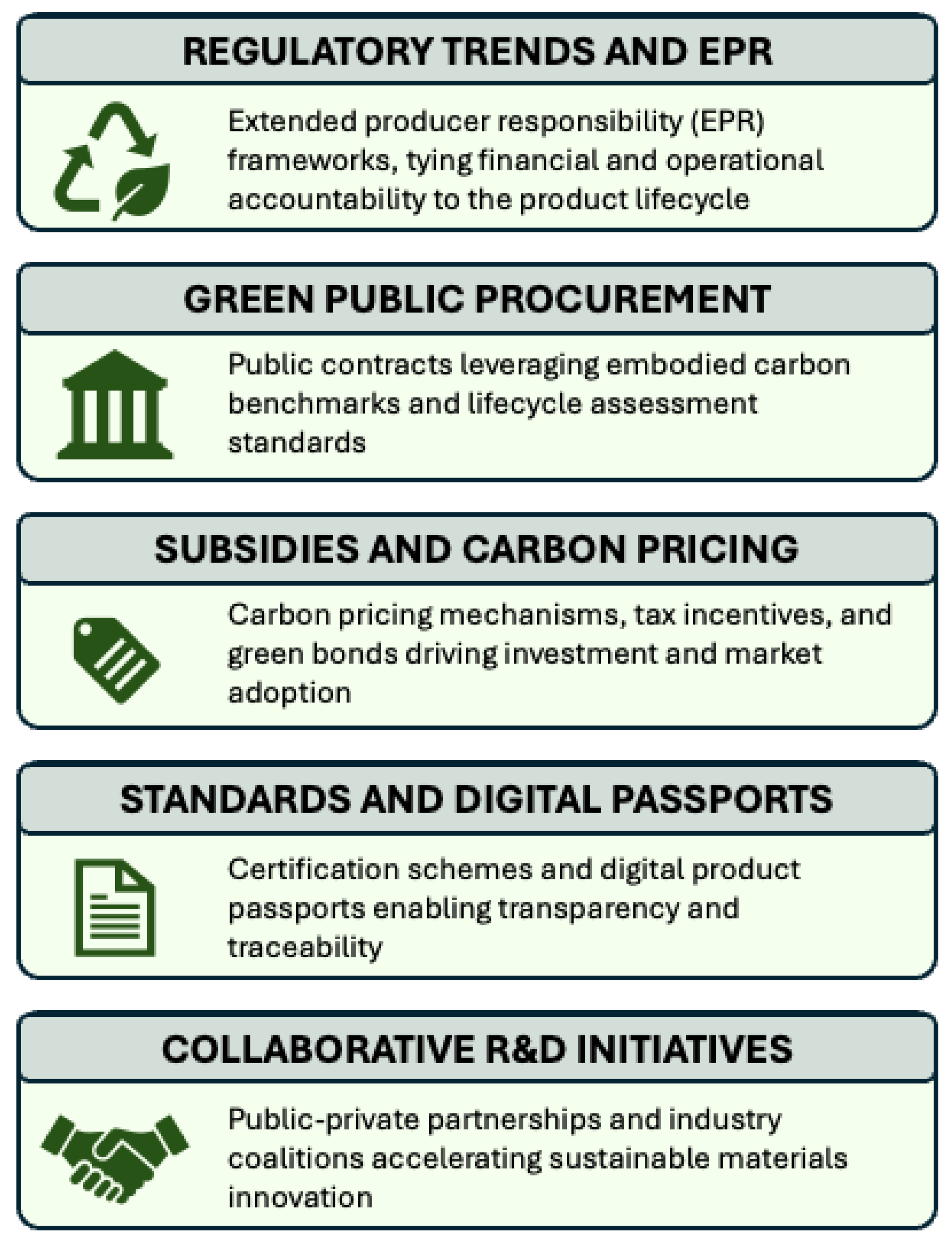

6. Infrastructure, Policy, and Industry Catalysts

6.1. Regulatory Trends and Extended Producer Responsibility

6.2. Green Public Procurement and Carbon Accounting Standards

6.3. Subsidies, Carbon Pricing, and Market Incentives

6.4. Standards, Certification, and Digital Transparency Tools

6.5. Collaborative R&D and Industry Coalitions

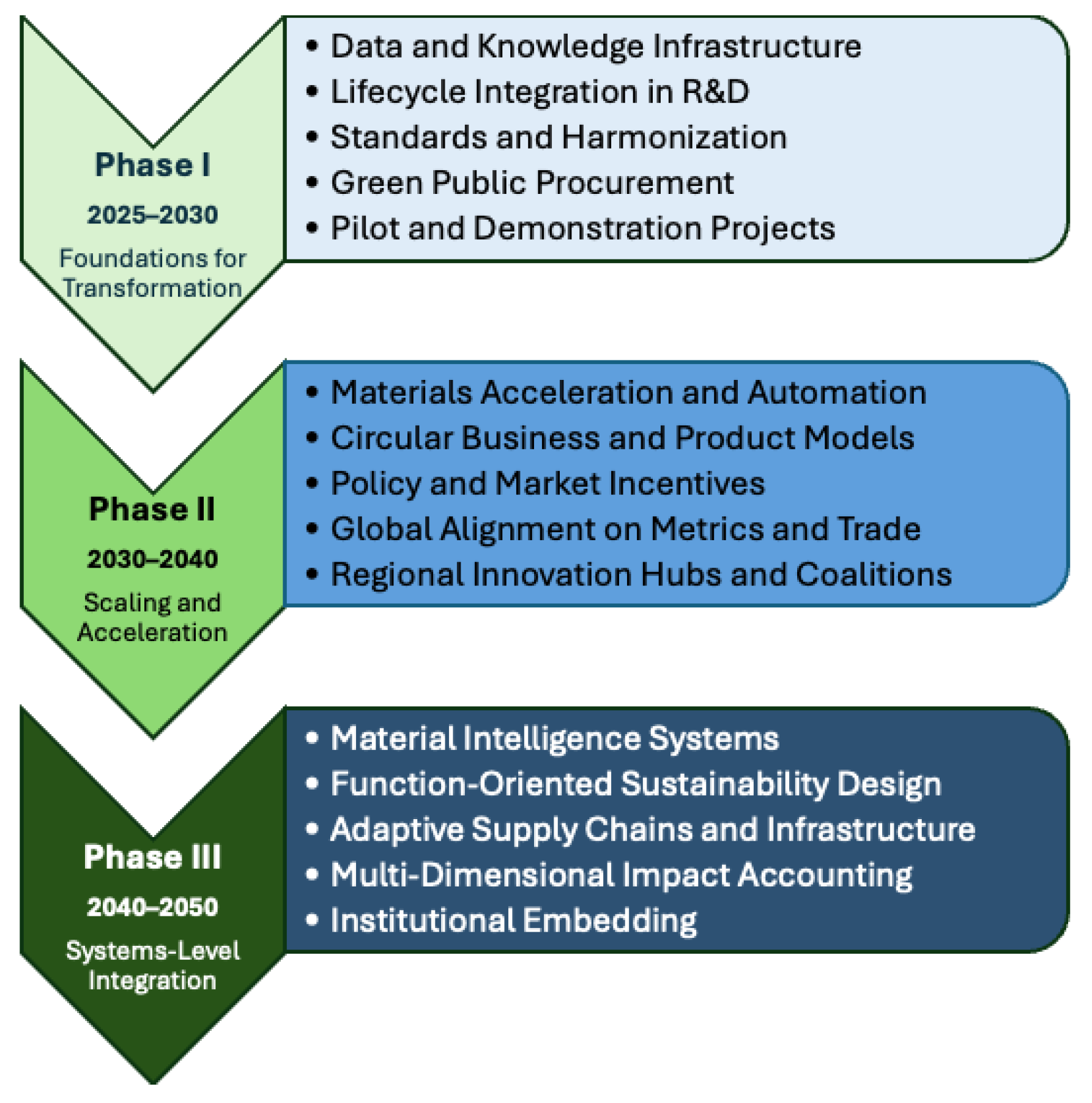

7. Roadmap and Outlook

7.1. Phase I (2025–2030): Foundations; Data, Verification, and Early Market Pull

7.1.1. Trustworthy Data Infrastructure

- shared databases with FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) principles

- explicit cradle-to-gate or cradle-to-grave boundaries

- declared electricity mix, allocation method, and recycled content

- versioned updates rather than static one number per material claims

7.1.2. Embedding LCA and Durability Screening into Early R&D

7.1.3. Harmonized Disclosure and Procurement Standards

- requiring product level EPDs that follow ISO 14040/44, ISO 21930, and EN 15804

- setting maximum global warming potential per unit material (e.g., kg CO2e per kg steel, per MPa·year concrete)

- awarding bids not only on cost but also on verified embodied carbon performance

7.1.4. Independent Pilot and Demonstration Projects

7.2. Phase II (2030–2040): Scaling; Manufacturing, Finance, and Trade Alignment

7.2.1. Regional Materials Acceleration Platforms and Shared Pilot Infrastructure

- derisk process intensification (e.g., electrified kilns, low clinker binders, solvent recovery loop chemistries);

- generate reproducible datasets for regulatory approval and procurement pre qualification;

- provide testing capacity for small and medium sized enterprises that cannot afford in house advanced analytics.

7.2.2. Circular Business Models and Reverse Logistics

7.2.3. Finance and Carbon Pricing

7.2.4. Alignment of Trade and Standards

7.3. Phase III (2040–2050): Integration; From Lower Impact Materials to Accountable Material Systems

7.3.1. Universal Traceability for Priority Material Classes

- composition (including hazardous substances and critical raw materials),

- recycled and biobased content,

- repairability and disassembly guidance,

- embodied carbon disclosure aligned to agreed system boundaries.

7.3.2. Function Based Performance Metrics Embedded into Design Tools

7.3.3. Retrofitting and Repurposing Legacy Assets

7.3.4. Composite Impact Accounting

7.4. Path Forward

8. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kim, J.; Sovacool, B.K.; Bazilian, M.; Griffiths, S.; Yang, M. Energy, material, and resource efficiency for industrial decarbonization: A systematic review of sociotechnical systems, technological innovations, and policy options. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2024, 112, 103521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunford, M.; Han, M. Energy dilemmas: Climate change, creative destruction and inclusive carbon-neutral modernization path transitions. Int. Crit. Thought 2025, 15, 76–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, C.; Dissanayake, H.; Mansi, E.; Stancu, A. Eco Breakthroughs: Sustainable Materials Transforming the Future of Our Planet. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.; Teng, Y. Decoupling of economic and carbon emission linkages: Evidence from manufacturing industry chains. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 322, 116081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertwich, E.G. Increased carbon footprint of materials production driven by rise in investments. Nat. Geosci. 2021, 14, 151–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, E.; AbouZeid, M. A global assessment tool for cement plants improvement measures for the reduction of CO2 emissions. Results Eng. 2025, 26, 104767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Zhao, S.; Tremblay, L.A.; Wang, W.; LeBlanc, G.A.; AN, L. Implications of plastic pollution on global carbon cycle. Carbon Res. 2025, 4, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raihan, A.; Ridwan, M.; Zimon, G.; Rahman, J.; Tanchangya, T.; Bari, A.M.; Atasoy, F.G.; Chowdhury, A.I.; Akter, R. Dynamic effects of foreign direct investment, globalization, economic growth, and energy consumption on carbon emissions in Mexico: An ARDL approach. Innov. Green Dev. 2025, 4, 100207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windisch, M.G.; Humpenöder, F.; Merfort, L.; Bauer, N.; Luderer, G.; Dietrich, J.P.; Heinke, J.; Müller, C.; Abrahao, G.; Lotze-Campen, H.; et al. Hedging our bet on forest permanence for the economic viability of climate targets. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 2460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, B.; Xiao, J.; Guan, X. Target low-carbon conditional probability for low-carbon structural design. Struct. Saf. 2025, 117, 102636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M. Embodied Carbon: Carbon Justice in the Built Environment; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B. Prospects on sustainable construction materials: Research gaps, challenges, and innovative approaches. In Wastes to Low-Carbon Construction Materials; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025; pp. 651–672. [Google Scholar]

- Marra, E.; Capuzzimati, C.; Menato, S.; Canetta, L. Overview of Gaps in LCA Data Quality and Future Perspectives. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE International Conference on Engineering, Technology, and Innovation (ICE/ITMC), Valencia, Spain, 16–19 June 2025; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2025; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Browne, G.R.; Hürlimann, A.C.; March, A.; Bush, J.; Warren-Myers, G.; Moosavi, S. Better policy to support climate change action in the built environment: A framework to analyse and design a policy portfolio. Land Use Policy 2024, 145, 107268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Economic Forum. Cement Production: How Sustainable Concrete Can Reduce CO2 Emissions. World Economic Forum Stories, September 2024. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/stories/2024/09/cement-production-sustainable-concrete-co2-emissions/ (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- International Energy Agency. CO2 Emissions—Global Energy Review 2025. 24 March 2025. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/global-energy-review-2025/co2-emissions (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- MIT Climate Portal. Exploring the Current Global Economy’s Major Material and Energy Flows. 2024. Available online: https://impactclimate.mit.edu/2024/08/23/exploring-the-current-global-economys-major-material-energy-flows/ (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Friedlingstein, P.; O’Sullivan, M.; Jones, M.W.; Andrew, R.M.; Hauck, J.; Landschützer, P.; Le Quéré, C.; Li, H.; Luijkx, I.T.; Olsen, A.; et al. Global Carbon Budget 2024. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2025, 17, 965–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agency. Global Energy Review 2025. Total Global CO2 Emissions in 2022 = 36.8 Gt. 2025. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/global-energy-review-2025 (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Gong, Q.; Wu, J.; Jiang, Z.; Hu, M.; Chen, J.; Cao, Z. An integrated design method for remanufacturing scheme considering carbon emission and customer demands. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 476, 143681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azari, R.; Kamel, E.; Memari, A.M. Current developments and future directions in energy-efficient buildings from the perspective of building construction materials and enclosure systems. Buildings 2024, 14, 1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.; Luo, Z.; Cang, Y.; Zhang, N.; Yang, L. Methods for calculating building-embodied carbon emissions for the whole design process. Fundam. Res. 2025, 5, 2187–2198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukah, A.S.K.; Jin, X.; Osei-Kyei, R.; Perera, S. Scientometric review of strategies to mitigate embodied carbon emissions in the construction industry. J. Eng. Des. Technol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myint, N.N.; Shafique, M.; Zhou, X.; Zheng, Z. Net zero carbon buildings: A review on recent advances, knowledge gaps and research directions. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 22, e04200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lützkendorf, T.; Balouktsi, M. Embodied carbon emissions in buildings: Explanations, interpretations, recommendations. Build. Cities 2022, 3, 964–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wernet, G.; Bauer, C.; Steubing, B.; Reinhard, J.; Moreno-Ruiz, E.; Weidema, B.P. The ecoinvent database version 3 (part I): Overview and methodology. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2016, 21, 1218–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Energy Efficiency & Renewable Energy. GREET. Available online: https://www.energy.gov/eere/greet (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Sphera. Life Cycle Assessment Software and Data | Sphera (GaBi). Available online: https://sphera.com/solutions/product-stewardship/life-cycle-assessment-software-and-data/ (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- International Energy Agency. Key Progress Indicator: Emissions and Emissions Intensity of Cement Production. 2024. Available online: https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/charts/key-progress-indicator-emissions-and-emissions-intensity-of-cement-production (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Cheng, D.; Reiner, D.M.; Yang, F.; Cui, C.; Meng, J.; Shan, Y.; Liu, Y.; Tao, S.; Guan, D. Projecting future carbon emissions from cement production in developing countries. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 8213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanco, P.S.; Arcipowska, A.; Fiorese, G.; Maury, T.; Napolano, L. Defining Low-Carbon Emissions Steel: A Comparative Analysis of Production Routes; Technical Report, European Commission, Joint Research Centre. 2025. Available online: https://denuo.be/sites/default/files/250428%20JRC%20comparative%20methods%20study_low%20carbon%20emissions%20steel.pdf (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- International Aluminium Institute. Global Aluminium Industry Greenhouse Gas Emissions Intensity Reduction Continues with Total Emissions Below 2020 Peak. 2024. Available online: https://international-aluminium.org/global-aluminium-industry-greenhouse-gas-emissions-intensity-reduction-continues-with-total-emissions-below-2020-peak/ (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Kim, T.; Benavides, P.T.; Kneifel, J.; Beers, K.; Lu, Z.; Hawkins, T.R. Life-Cycle Analysis Datasets for Regionalized Plastic Pathways; Technical Report; Argonne National Laboratory (ANL): Argonne, IL, USA, 2024.

- Bergsma, G.; Broeren, M.; van de Pol, J. Sustainability of Biobased Plastics: Analysis Focusing on CO2 for Policies; Technical Report 23.220217.017; CE Delft: Delft, The Netherlands, 2023; Available online: https://cedelft.eu/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2023/04/CE_Delft_22021_Sustainability_of_Biobased_Plastics_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Keyes, A.; Saffron, C.M.; Manjure, S.; Narayan, R. Biobased Compostable Plastics End-of-Life: Environmental Assessment Including Carbon Footprint and Microplastic Impacts. Polymers 2024, 16, 3073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agency. CO2 Emissions in 2023. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/co2-emissions-in-2023 (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Volaity, S.S.; Aylas-Paredes, B.K.; Han, T.; Huang, J.; Sridhar, S.; Sant, G.; Kumar, A.; Neithalath, N. Towards decarbonization of cement industry: A critical review of electrification technologies for sustainable cement production. NPJ Mater. Sustain. 2025, 3, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royle, M.; Chachuat, B.; Xu, B.; Gibson, E.A. The pathway to net zero: A chemicals perspective. RSC Sustain. 2024, 2, 1337–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- One Click LCA. Global Emissions from Construction and Manufacturing. Available online: https://oneclicklca.com/en/resources/articles/global-emissions-from-construction-and-manufacturing/ (accessed on 21 July 2021).

- Sonke, J.E.; Koenig, A.; Segur, T.; Yakovenko, N. Global environmental plastic dispersal under OECD policy scenarios toward 2060. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eadu2396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benita, F.; Gaytán-Alfaro, D. A linkage analysis of the mining sector in the top five carbon emitter economies. Reg. Sci. Policy Pract. 2024, 16, 12678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recasting the Future: Policy Approaches to Drive Cement Decarbonization. Available online: https://www.catf.us/resource/recasting-future-policy-approaches-drive-cement-decarbonization/ (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Working Group III. Chapter 11: Industry. In Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg3/chapter/chapter-11/ (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- Perossa, D.; Rosa, P.; Terzi, S. A Systematic Literature Review of Existing Methods and Tools for the Criticality Assessment of Raw Materials: A Focus on the Relations between the Concepts of Criticality and Environmental Sustainability. Resources 2024, 13, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona Aparicio, G.; Carrasco, A.; Whiting, K.; Cullen, J. The ecocircularity performance index: Measuring quantity and quality in resource circularity assessments. Miner. Econ. 2025, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.h.; Yang, X.d.; Hou, Y.b.; He, Y.; Pak, J.J.; El-Mahallawi, I. CO2 emission reduction in a new BF–IF–BOF steelmaking process. J. Iron Steel Res. Int. 2025, 32, 2334–2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhit, I.B.; Omairey, E.L.; Pashakolaie, V.G. A holistic sustainability overview of hemp as building and highway construction materials. Build. Environ. 2024, 256, 111470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanbhag, S.S.; Dixit, M.K. Understanding Carbon-Negative Potential of Hempcrete Using a Life Cycle Assessment Approach. In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Net-Zero Built Environment (NTZR 2024), Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering, Oslo, Norway, 19–21 June 2024; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; Volume 237, pp. 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, K. Life Cycle Assessment of a Hemp-Based Thermal Insulation Panel; WWU Graduate School Collection. 2024, 1295. Available online: https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet/1295 (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Wang, K.; Tong, R.; Zhai, Q.; Lyu, G.; Li, Y. A Critical Review of Life Cycle Assessments on Bioenergy Technologies: Methodological Choices, Limitations, and Suggestions for Future Studies. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jyothsna, G.; Bahurudeen, A.; Sahu, P.K. Sustainable utilisation of rice husk for cleaner energy: A circular economy between agricultural, energy and construction sectors. Mater. Today Sustain. 2024, 25, 100667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gailani, A.; Cooper, S.; Allen, S.; Pimm, A.; Taylor, P.; Gross, R. Assessing the potential of decarbonization options for industrial sectors. Joule 2024, 8, 576–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladapo, B.I.; Olawumi, M.A.; Olugbade, T.O.; Tin, T.T. Advancing sustainable materials in a circular economy for decarbonisation. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 360, 121116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamandi, M. Sustainable Innovation Management: Balancing Economic Growth and Environmental Responsibility. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramaniyan, Y.; Soundararajan, E.K. Environment-Friendly Manufacturing. In Green Manufacturing: Challenges and Applications; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Hemmati, M.; Messadi, T.; Gu, H.; Seddelmeyer, J.; Hemmati, M. Comparison of embodied carbon footprint of a mass timber building structure with a steel equivalent. Buildings 2024, 14, 1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunaratne, K. Recasting the Future Policy Approaches to Drive Cement Decarbonization. LUT University Repository. Available online: https://lutpub.lut.fi/handle/10024/169964 (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- Tariq, Z.; Bahadori-Jahromi, A. Incorporating ground granulated blast furnace slag & fly ash in concrete production for sustainable construction: A review. Eng. Future Sustain. 2025, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Shi, B.; Dai, X.; Chen, C.; Lai, C. A State-of-the-Art Review on the Freeze–Thaw Resistance of Sustainable Geopolymer Gel Composites: Mechanisms, Determinants, and Models. Gels 2025, 11, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusnak, C.R. Sustainable Strategies for Concrete Infrastructure Preservation: A Comprehensive Review and Perspective. Infrastructures 2025, 10, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, R.A. Biocatalysis, solvents, and green metrics in sustainable chemistry. In Biocatalysis in Green Solvents; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Slootweg, J.C. Sustainable chemistry: Green, circular, and safe-by-design. ONE Earth 2024, 7, 754–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurul, F.; Doruk, B.; Topkaya, S.N. Principles of green chemistry: Building a sustainable future. Discov. Chem. 2025, 2, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancaster, M. Green Chemistry: An Introductory Text; Royal Society of Chemistry: London, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Alder, C.M.; Hayler, J.D.; Henderson, R.K.; Redman, A.M.; Shukla, L.; Shuster, L.E.; Sneddon, H.F. Updating and further expanding GSK’s solvent sustainability guide. Green Chem. 2016, 18, 3879–3890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prat, D.; Wells, A.; Hayler, J.; Sneddon, H.; McElroy, C.R.; Abou-Shehada, S.; Dunn, P.J. CHEM21 selection guide of classical-and less classical-solvents. Green Chem. 2016, 18, 288–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colberg, J.; Arat, S.; Gonzalez Esguevillas, M.; France, S.; Huot, K.; Kumar, R.; Laity, D.; Lall, M.; Lee, J.; Magano, J.; et al. Pfizer’s Green Chemistry Program. ACS Chemistry for Life, American Chemical Society. 2021. Available online: https://communities.acs.org/t5/GCI-Nexus-Blog/Pfizer-s-Green-Chemistry-Program/ba-p/86557 (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- Sheldon, R.A. The E factor at 30: A passion for pollution prevention. Green Chem. 2023, 25, 1704–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaghemandi, M. Sustainable solutions through innovative plastic waste recycling technologies. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Maldonado, Y.; Correa-Quintana, E.; Ospino-Castro, A. Electrification of industrial processes as an alternative to replace conventional thermal power sources. Energies 2023, 16, 6894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraldo, F.; Byrne, P. A review of energy-efficient technologies and decarbonating solutions for process heat in the food industry. Energies 2024, 17, 3051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woidasky, J.; Araujo, J.B.; Hinderer, H.; Viere, T. Circular Economy Engineering: Technologies and Business Solutions to Implement Circularity; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Baltrocchi, A.P.D.; Carnevale Miino, M.; Maggi, L.; Rada, E.C.; Torretta, V. A comprehensive critical review of Life Cycle Assessment applied to thermoplastic polymers for mechanical and electronic engineering. Environ. Technol. Rev. 2025, 14, 458–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 15804; Life Cycle Data Network. European Commission, Joint Research Centre: Brussels, Belgium, 2016. Available online: https://eplca.jrc.ec.europa.eu/LCDN/EN15804.html (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- ISO 21930; Sustainability in Buildings and Civil Engineering Works—Core Rules for Environmental Product Declarations of Construction Products and Services. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/61694.html (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- European Commission. Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation (ESPR); European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter, R.; Fang, H. Geopolitics of Rare Earths: Global Power Shifts Through Critical Raw Materials; BoD–Books on Demand: Hamburg, Germany, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Concordel, A. Securing the Future: Critical Materials Policies for the US Energy Transition. Ph.D. Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, J.; Liu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Liang, H.; Wang, H.; Song, P. Rethinking the pathway to sustainable fire retardants. In Proceedings of the Exploration; Wiley Online Library: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2023; Volume 3, p. 20220088. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Q.; Jin, H.; Zhu, J.; Li, Z.; Xu, H.; Liu, B.; Zhang, Z.; Ma, J.; Mu, S. Stabilizing Fe–N–C catalysts as model for oxygen reduction reaction. Adv. Sci. 2021, 8, 2102209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, G.; Kim, M.M.; Han, M.H.; Cho, J.; Kim, D.H.; Sougrati, M.T.; Kim, J.; Lee, K.S.; Joo, S.H.; Goddard III, W.A.; et al. Unravelling the complex causality behind Fe–N–C degradation in fuel cells. Nat. Catal. 2023, 6, 1140–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, P.; Bai, J.; Guan, X.; Wang, S.; Lan, C.; Wu, H.; Shi, Z.; Zhu, S.; et al. Unraveling the potential-dependent degradation mechanism in Fe-NC catalysts for oxygen reduction reaction. Sci. China Chem. 2025, 68, 1541–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Guo, Q.; Yuan, Y.; Li, A.; Lin, B.; Xiao, Y.; Xu, L.; Wang, W. Recent advancements of bio-derived flame retardants for polymeric materials. Polymers 2025, 17, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malkappa, K.; Prasad, C.; Kang, C.S.; Jeong, S.G.; Sangaraju, S.; Shin, E.J.; Choi, H.Y. Recent developments of phosphorous–nitrogen-based effective intumescent flame-retardant for polymers and textiles. Polym. Bull. 2025, 82, 5139–5199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiti, S.; Islam, M.R.; Uddin, M.A.; Afroj, S.; Eichhorn, S.J.; Karim, N. Sustainable fiber-reinforced composites: A review. Adv. Sustain. Syst. 2022, 6, 2200258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajendran, S.; Al-Samydai, A.; Palani, G.; Trilaksana, H.; Sathish, T.; Giri, J.; Saravanan, R.; Lalvani, J.I.J.; Nasri, F. Replacement of Petroleum Based Products With Plant-Based Materials, Green and Sustainable Energy—A Review. Eng. Rep. 2025, 7, e70108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallick, P.K.; Salling, K.B.; Pigosso, D.C.A.; McAloone, T.C. Designing and operationalising extended producer responsibility under the EU Green Deal: A life cycle-based conceptual framework. Environ. Chall. 2024, 9, 100841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.Y.A.; Herat, S.; Kaparaju, P. Current status and compliance management of EPR regulations for packaging waste in Vietnam: A stakeholder-based evaluation. Circ. Econ. Sustain. 2025, 5, 2921–2958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geist, H.; Balle, F. Recyclability: Redefining the concept for the circular economy. J. Ind. Ecol. 2025, 29, 1505–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, M.; Liu, X.; Feng, Y.; Huang, M.; Liu, C.; Shen, C. Reprocessable and repairable carbon fiber reinforced vitrimer composites based on thermoreversible dynamic covalent bonding. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2024, 255, 110731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, A.; Parasuram, S.; Salvi, A.S.; Kumar, S.; Bose, S. Triple Dynamic Network-Enabled Vitrimer for Repairable and Recyclable Carbon Fiber-Reinforced Composites. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2025, 7, 4931–4943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Zheng, J.; Yeo, J.C.C.; Wang, S.; Li, K.; Muiruri, J.K.; Hadjichristidis, N.; Li, Z. Dynamic covalent bonds enabled carbon fiber reinforced polymers recyclability and material circularity. Angew. Chem. 2024, 136, e202408969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Yan, L.; Zheng, Y.; Dai, L.; Si, C. Lignin-Based Vitrimer for High-Resolution and Full-Component Rapidly Recycled Liquid Metal Printed Circuit. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2425780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloyi, R.B.; Gbadeyan, O.J.; Sithole, B.; Chunilall, V. Recent advances in recycling technologies for waste textile fabrics: A review. Text. Res. J. 2024, 94, 508–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifali Abbas-Abadi, M.; Tomme, B.; Goshayeshi, B.; Mynko, O.; Wang, Y.; Roy, S.; Kumar, R.; Baruah, B.; De Clerck, K.; De Meester, S.; et al. Advancing textile waste recycling: Challenges and opportunities across polymer and non-polymer fiber types. Polymers 2025, 17, 628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oke, E.A.; Potgieter, H. Recent chemical methods for metals recovery from printed circuit boards: A review. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2024, 26, 1349–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebringshausen, A.; Eversmann, P.; Göbert, A. Circular, zero waste formwork-Sustainable and reusable systems for complex concrete elements. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 80, 107696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 14025; Environmental Labels and Declarations—Type III Environmental Declarations—Principles and Procedures. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/38131.html (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- van Vuuren, D.P.; Zimm, C.; Busch, S.; Kriegler, E.; Leininger, J.; Messner, D.; Nakicenovic, N.; Rockstrom, J.; Riahi, K.; Sperling, F.; et al. Defining a sustainable development target space for 2030 and 2050. ONE Earth 2022, 5, 142–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Zhou, P. How does artificial intelligence change carbon emission intensity? A firm lifecycle perspective. Appl. Econ. 2025, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, L.; Yager, J.A.; Monteverde, D.; Baiocchi, D.; Kwon, H.K.; Sun, S.; Suram, S. Autonomous laboratories for accelerated materials discovery: A community survey and practical insights. Digit. Discov. 2024, 3, 1273–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madika, B.; Saha, A.; Kang, C.; Buyantogtokh, B.; Agar, J.; Wolverton, C.M.; Voorhees, P.; Littlewood, P.; Kalinin, S.; Hong, S. Artificial intelligence for materials discovery, development, and optimization. ACS Nano 2025, 19, 27116–27158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goga, A.S. Integrating Artificial Intelligence in Nanomaterials Science: Pathways to Revolutionary Materials Discovery and Design. Ethics and Risks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Innovative Research; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Lodhi, S.K.; Gill, A.Y.; Hussain, H.K. Green innovations: Artificial intelligence and sustainable materials in production. Bull. J. Multidisiplin Ilmu 2024, 3, 492–507. [Google Scholar]

- Maqsood, A.; Chen, C.; Jacobsson, T.J. The future of material scientists in an age of artificial intelligence. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, 2401401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaddick, G.; Topping, D.; Hales, T.C.; Kadri, U.; Patterson, J.; Pickett, J.; Petri, I.; Taylor, S.; Li, P.; Sharma, A.; et al. Data science and AI for sustainable futures: Opportunities and challenges. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, S.; Schmeink, A. Data-centric green artificial intelligence: A survey. IEEE Trans. Artif. Intell. 2023, 5, 1973–1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Ong, S.P. Graph deep learning for materials science and chemistry. Nat. Rev. Phys. 2023, 5, 255–273. [Google Scholar]

- Reiser, P.; Neubert, M.; Eberhard, A.; Torresi, L.; Zhou, C.; Shao, C.; Metni, H.; van Hoesel, C.; Schopmans, H.; Sommer, T.; et al. Graph-neural-networks for materials science and chemistry. Commun. Mater. 2022, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, T.; Mayo Yanes, E.; Chakraborty, S.; Cosmo, L.; Bronstein, A.M.; Gershoni-Poranne, R. Guided diffusion for inverse molecular design. Nat. Comput. Sci. 2023, 3, 873–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bran, A.M.; Cox, S.; Schilter, O.; Baldassari, C.; White, A.D.; Schwaller, P. ChemCrow: A large language model-chemist interface for chemical design. Nat. Chem. 2024, 16, 273–284. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, K.; Ulissi, Z.W. Active learning across intermetallics to guide discovery of electrocatalysts for CO2 reduction and H2 evolution. Nat. Catal. 2020, 3, 532–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghafarollahi, A.; Buehler, M.J. ProtAgents: Protein Discovery via Large Language Model Multi-Agent Collaborations Combining Physics and Machine Learning. Digit. Discov. 2024, 3, 1389–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, K.; DeCost, B. Atomistic line graph neural network for improved materials property predictions. NPJ Comput. Mater. 2021, 7, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reer, A.; Wiebe, A.; Wang, X.; Rieger, J.W. FAIR human neuroscientific data sharing to advance AI driven research and applications: Legal frameworks and missing metadata standards. Front. Genet. 2023, 14, 1086802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aboutalebi, S.H. Ensuring Data Integrity in AI-Driven Materials Science: Why F-Sum Rules and Kramers-Kronig Relations Matter. Nanoscale Adv. Mater. 2025, 2, 10–15. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, A.; Ong, S.P.; Hautier, G.; Chen, W.; Richards, W.D.; Dacek, S.; Cholia, S.; Gunter, D.; Skinner, D.; Ceder, G.; et al. Commentary: The Materials Project: A materials genome approach to accelerating materials innovation. APL Mater. 2013, 1, 011002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, R.; Lan, J.; Shuaibi, M.; Wood, B.M.; Goyal, S.; Das, A.; Heras-Domingo, J.; Kolluru, A.; Rizvi, A.; Shoghi, N.; et al. The Open Catalyst 2022 (OC22) dataset and challenges for oxide electrocatalysts. ACS Catal. 2023, 13, 3066–3084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Pilania, G.; Batra, R.; Huan, T.D.; Kim, C.; Kuenneth, C.; Ramprasad, R. Polymer informatics: Current status and critical next steps. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 2020, 144, 100595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, A.S.; Iyer, S.M.; Ray, D.; Yao, Z.; Aspuru-Guzik, A.; Gagliardi, L.; Snurr, R.Q. Machine learning the quantum-chemical properties of metal–organic frameworks for accelerated materials discovery. Matter 2021, 4, 1578–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borysov, S.S.; Geilhufe, R.M.; Balatsky, A.V. Organic Materials Database: An Open-Access Online Database for Data Mining. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0171501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, M.L.; Bergsma, J.; Merkys, A.; Andersen, C.W.; Andersson, O.B.; Beltrán, D.; Blokhin, E.; Boland, T.M.; Balderas, R.C.; Choudhary, K.; et al. Developments and Applications of the OPTIMADE API for Materials Discovery, Design, and Data Exchange. Digital Discovery 2024, 3, 1509–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, C.; Meng, C.; Wang, S.; Driscoll, A.; Rozi, E.; Liu, P.; Ermon, S. SustainBench: Benchmarks for monitoring the sustainable development goals with machine learning. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2111.04724. [Google Scholar]

- Abolhasani, M.; Kumacheva, E. The rise of self-driving labs in chemical and materials sciences. Nat. Synth. 2023, 2, 483–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, S.; Canty, R.B.; Mukhin, N.; Xu, J.; Delgado-Licona, F.; Abolhasani, M. Engineering a sustainable future: Harnessing automation, robotics, and artificial intelligence with self-driving laboratories. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 12695–12707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dembski, S.; Schwarz, T.; Oppmann, M.; Bandesha, S.T.; Schmid, J.; Wenderoth, S.; Mandel, K.; Hansmann, J. Establishing and testing a robot-based platform to enable the automated production of nanoparticles in a flexible and modular way. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 11440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymanski, N.J.; Rendy, B.; Fei, Y.; Kumar, R.E.; He, T.; Milsted, D.; McDermott, M.J.; Gallant, M.; Cubuk, E.D.; Merchant, A.; et al. An autonomous laboratory for the accelerated synthesis of novel materials. Nature 2023, 624, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, P.; He, T.; Zhu, H.; Wang, Y.; Li, Q.; Wang, Z.; Fu, X.; Wang, F.; Wang, P.; Shan, C.; et al. Next-generation machine vision systems incorporating two-dimensional materials: Progress and perspectives. InfoMat 2022, 4, e12275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stach, E.A.; DeCost, B.; Kusne, A.G.; Hattrick-Simpers, J.; Brown, K.A.; Reyes, K.G.; Schrier, J.; Billinge, S.; Buonassisi, T.; Foster, I.; et al. Autonomous experimentation systems for materials development: A community perspective. Matter 2021, 4, 2702–2726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Leonar, M.M.; Mejía-Mendoza, L.M.; Aguilar-Granda, A.; Sanchez-Lengeling, B.; Amador-Bedolla, A.; Aspuru-Guzik, A.; Tribukait, H. Materials acceleration platforms: On the way to autonomous experimentation. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2023, 8, 227–244. [Google Scholar]

- Coley, C.W.; Eyke, N.S.; Jensen, K.F. Autonomous discovery in the chemical sciences part I: Progress. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 22858–22893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X. AI and Robotic Technology in Materials and Chemistry Research; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, J.A.; Orouji, N.; Khan, M.; Sadeghi, S.; Rodgers, J.; Abolhasani, M. Autonomous Reaction Pareto-Front Mapping with a Self-Driving Catalysis Laboratory. Nat. Chem. Eng. 2024, 1, 240–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorayev, P.; Soritz, S.; Sung, S.; Jeraal, M.I.; Russo, D.; Barthelme, A.; Toussaint, F.C.; Gaunt, M.J.; Lapkin, A.A. Machine Learning-Driven Optimization of Continuous-Flow Photoredox Amine Synthesis. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2025, 29, 1411–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, H.; Ma, L.; Liu, D.; Zhang, D. AI-driven discovery of high-performance corrosion inhibitors using a BERT-GPT framework for molecular generation. Corros. Sci. 2025, 257, 113327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, J.P.; Han, T.; Sant, G.; Neithalath, N.; Huang, J.; Kumar, A. Toward smart and sustainable cement manufacturing process: Analysis and optimization of cement clinker quality using thermodynamic and data-informed approaches. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2024, 147, 105436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvizu-Montes, A.; Guerrero-Bustamante, O.; Polo-Mendoza, R.; Martinez-Echevarria, M. Integrating Life-Cycle Assessment (LCA) and Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) for Optimizing the Inclusion of Supplementary Cementitious Materials (SCMs) in Eco-Friendly Cementitious Composites: A Literature Review. Materials 2025, 18, 4307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Mosbach, S.; Taylor, C.J.; Karan, D.; Lee, K.F.; Rihm, S.D.; Akroyd, J.; Lapkin, A.A.; Kraft, M. A dynamic knowledge graph approach to distributed self-driving laboratories. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, H.B.; Kosjek, B.; Armstrong, B.M.; Robaire, S.A. Green and sustainable metrics: Charting the course for green-by-design small molecule API synthesis. Curr. Res. Green Sustain. Chem. 2022, 5, 100324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karuppusamy, M.; Thirumalaisamy, R.; Palanisamy, S.; Nagamalai, S.; Massoud, E.E.S.; Ayrilmis, N. A review of machine learning applications in polymer composites: Advancements, challenges, and future prospects. J. Mater. Chem. A 2025, 13, 16290–16308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dass, A.; Moridi, A. State of the art in directed energy deposition: From additive manufacturing to materials design. Coatings 2019, 9, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutel, C. Brightway: An open source framework for life cycle assessment. J. Open Source Softw. 2017, 2, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pamu, Y.; Kumar, V.; Shakir, M.A.; Ubbana, H. Life Cycle Assessment of a building using Open-LCA software. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 52, 1968–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Cai, H.; Ou, L.; Elgowainy, A.; Benavides, T.; Masum, F.; Benvenutti, L.; Kwon, H.; Liu, X.; Lu, Z.; et al. Summary of Expansions and Updates in R&D GREET® 2024 Rev. 1; Technical Report; Argonne National Laboratory (ANL): Lemont, IL, USA, 2024.

- Ecoinvent Association. Ecoinvent Database, Version 3.11; Ecoinvent Association: Zurich Switzerland, 2024; Database Release and Online Documentation. Available online: https://ecoinvent.org/ecoinvent-v3-11/ (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL). U.S. Life Cycle Inventory (USLCI) Database. 2025. Available online: https://www.nrel.gov/analysis/lci (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- Rasul, K.; Schmidt, S.; Hertwich, E.G.; Wood, R. EXIOBASE energy accounts: Improving precision in an open-sourced procedure applicable to any MRIO database. J. Ind. Ecol. 2024, 28, 1771–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, E.; Antognoli, E.; Arbuckle, P. The LCA commons—how an open-source repository for US federal life cycle assessment (LCA) data products advances inter-agency coordination. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatnagar, A.; Härri, A.; Levänen, J.; Niinimäki, K. Exploring the role of social life cycle assessment in transition to circular economy: A systematic review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2024, 207, 107702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostapanou, A.; Chatzipanagiotou, K.R.; Damilos, S.; Petrakli, F.; Koumoulos, E.P. Safe-and-Sustainable-by-Design Framework:(Re-) Designing the Advanced Materials Lifecycle. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuhoff, R.; Simeone, L.; Holst Laursen, L. The potential of design-driven futuring to support strategising for sustainable futures. Des. J. 2022, 25, 955–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, C.; Pauliks, N.; Donati, F.; Engberg, N.; Weber, J. Machine learning to support prospective life cycle assessment of emerging chemical technologies. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2024, 50, 100979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, H.; Gurnani, R.; Kim, C.; Pilania, G.; Kwon, H.K.; Lively, R.P.; Ramprasad, R. Design of functional and sustainable polymers assisted by artificial intelligence. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2024, 9, 866–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Advanced Materials Initiative 2030 (AMI2030). Materials 2030 Roadmap. Available online: https://www.ami2030.eu/roadmap/ (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- U.S. Department of Energy. Critical Materials Assessment 2023; U.S. Department of Energy: Washington, DC, USA, 2023.

- European Commission. Materials 2030 Roadmap: A Strategic Vision for Advanced Materials in Europe; European Commission: Brussel, Belgium, 2023.

- Scrivener, K.L.; Provis, J.L.; John, V.M. Eco-efficient cements: Potential economically viable solutions for a low-CO2 world. Cem. Concr. Res. 2018, 114, 2–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shufrin, I.; Pasternak, E.; Dyskin, A. Environmentally friendly smart construction—Review of recent developments and opportunities. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 12891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provis, J.L.; Van Deventer, J.S.J. Geopolymers: Structures, Processing, Properties and Industrial Applications; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kriven, W.M.; Leonelli, C.; Provis, J.L.; Boccaccini, A.R.; Attwell, C.; Ducman, V.S.; Ferone, C.; Rossignol, S.; Luukkonen, T.; Van Deventer, J.S.; et al. Why geopolymers and alkali-activated materials are key components of a sustainable world: A perspective contribution. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2024, 107, 5159–5177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamburini, E.; Costa, S.; Ronchetti, F.; Bonomi, A. Plastic (PET) vs bioplastic (PLA) or refillable aluminium bottles—What is the most sustainable choice for drinking water? Environ. Res. 2021, 196, 110974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurya, A.K.; de Souza, F.M.; Dawsey, T.; Gupta, R.K. Biodegradable polymers and composites: Recent development and challenges. Polym. Compos. 2024, 45, 2896–2918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samir, A.; Ashour, F.H.; Hakim, A.A.; Bassyouni, M. Recent advances in biodegradable polymers for sustainable applications. NPJ Mater. Degrad. 2022, 6, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortman, D.J.; De Hoe, G.X.; Snyder, R.L.; Dichtel, W.R.; Hillmyer, M.A. Vitrimers: Can they deliver on the promise of closed-loop recycling of thermoset plastics? ACS Cent. Sci. 2018, 4, 1268–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, T.; Balzer, A.H.; Herbert, K.M.; Epps, T.H.; Korley, L.T. Circularity in polymers: Addressing performance and sustainability challenges using dynamic covalent chemistries. Chem. Sci. 2023, 14, 5243–5265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivas-Aybar, D.; John, M.; Biswas, W. Environmental life cycle assessment of a novel hemp-based building material. Materials 2023, 16, 7208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiciński, W.; Dyjak, S.; Gratzke, M.; Tokarz, W.; Błachowski, A. Platinum Group Metal-Free Fe–N–C Catalysts for PEM Fuel Cells Derived from Nitrogen and Sulfur Doped Synthetic Polymers. Fuel 2022, 328, 125323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, B.R.; Khan, N.I.; Gosvami, N.N.; Das, S. Recent Advancements in Self-Healing Materials and Their Application in Coating Industry. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part L J. Mater. Des. Appl. 2025, 239, 411–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosmose, A.; Li, M.; Sharma, B.K. Industrial hemp fiber: A sustainable and economical alternative to cotton for textiles. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 256, 120503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strömberg, A.e.a. Recycling Cotton Waste to Recover Cellulose Material. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 256, 121347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Jia, S.; Zhang, Z. PEDOT and PEDOT:PSS Thin-Film Electrodes: Patterning, Modification and Application in Stretchable Organic Optoelectronic Devices. J. Mater. Chem. C 2023, 11, 10435–10454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Song, T.; Shi, L.; Wen, N.; Wu, Z.; Sun, C.; Jiang, D.; Guo, Z. Recent Progress for Silver Nanowires Conducting Film for Flexible Electronics. J. Nanostructure Chem. 2021, 11, 323–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver-Ortega, H.; Julian, F.; Espinach, F.X.; Tarrés, Q.; Delgado-Aguilar, M.; Mutjé, P. Biobased polyamide reinforced with natural fiber composites. Fiber Reinf. Compos. 2021, 141–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Biswal, A.K.; Nandi, A.; Frost, K.; Smith, J.A.; Nguyen, B.H.; Patel, S.; Vashisth, A.; Iyer, V. Recyclable vitrimer-based printed circuit boards for sustainable electronics. Nat. Sustain. 2024, 7, 616–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, D.; Jiang, M.; Tutika, R.; Worch, J.; Bartlett, M. Liquid metal–vitrimer conductive composite for recyclable and resilient electronics. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, 2501341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Hong, S.H.; Hester, J.; Cheng, T.; Peng, H. DissolvPCB: Fully Recyclable 3D-Printed Electronics Using Liquid Metal Conductors and PVA Substrates. In Proceedings of the 38th Annual ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology (UIST ’25), Busan, Republic of Korea, 28 September–1 October 2025; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2025. 17p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, S.D.C.; Nguyen, Q.D.; Li, W.; Castel, A. Shrinkage and carbonation of alkali-activated calcined clay-ground granulated blast furnace slag (GGBFS) concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 2025, 194, 107899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Z.; Zhu, X. Microstructural insights and technical challenges of effectively adopting high-volume GGBS in blended cements for low-carbon construction. NPJ Mater. Sustain. 2025, 3, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Liu, Y.; Benn, T.; Luo, L.; Xie, T.; Zhuge, Y. A comprehensive framework for the design and optimisation of limestone-calcined clay cement: Integrating mechanical, environmental, and financial performance. J. Compos. Sci. 2024, 8, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golafshani, E.M.; Behnood, A.; Kim, T.; Ngo, T.; Kashani, A. A framework for low-carbon mix design of recycled aggregate concrete with supplementary cementitious materials using machine learning and optimization algorithms. In Proceedings of the Structures; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; Volume 61, p. 106143. [Google Scholar]

- Ekinci, E.; Kantarcı, F.; Maraş, M.M.; Ekinci, E.; Türkmen, İ.; Demirboğa, R. Historiography, Current Practice and Future Perspectives: A Critical Review of Geopolymer Binders. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muttil, N.; Sadath, S.; Coughlan, D.; Paresi, P.; Singh, S.K. Hemp as a sustainable carbon negative plant: A review of its properties, applications, challenges and future directions. Int. J. Integr. Eng. 2024, 16, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franz, A.W.; Buchholz, S.; Albach, R.W.; Schmid, R. Towards greener polymers: Trends in the German chemical industry. Green Carbon 2024, 2, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Righetti, G.I.C.; Faedi, F.; Famulari, A. Embracing sustainability: The World of bio-based polymers in a mini review. Polymers 2024, 16, 950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Du, S.; Zhu, J.; Ma, S. Closed-loop recyclable polymers: From monomer and polymer design to the polymerization–depolymerization cycle. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2024, 53, 9609–9651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moujoud, Y.; Bouloiz, H.; Gallab, M. Closing the Loop: Achieving a Sustainable Future for Plastics Through Eco-Design and Recycling. Eng. Proc. 2025, 97, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Verma, S.K.; Prasad, A.; Katiyar, V. State of Art Review on Sustainable Biodegradable Polymers with a Market Overview for Sustainability Packaging. Mater. Today Sustain. 2024, 26, 100776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naser, A.Z.; Deiab, I.; Darras, B.M. Poly (lactic acid)(PLA) and polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs), green alternatives to petroleum-based plastics: A review. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 17151–17196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ncube, L.K.; Ude, A.U.; Ogunmuyiwa, E.N.; Zulkifli, R.; Beas, I.N. Environmental impact of food packaging materials: A review of contemporary development from conventional plastics to polylactic acid based materials. Materials 2020, 13, 4994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bos, P.; Ritzen, L.; van Dam, S.; Balkenende, R.; Bakker, C. Bio-based plastics in product design: The state of the art and challenges to overcome. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; He, E.; Liang, H.; Yang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Z.; Gao, C.; Wang, G.; Wei, Y.; Ji, Y. Chemical recycling of epoxy thermosets: From sources to wastes. Actuators 2024, 13, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, X.; Liu, J.; Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X. Click dechlorination of halogen-containing hazardous plastics towards recyclable vitrimers. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 9759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delliere, P.; Bakkali-Hassani, C.; Caillol, S. Eugenol’s journey to high-performance and fire-retardant bio-based thermosets. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2025, 51, 100988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Huo, S.; Ye, G.; Zhang, Q.; Cao, C.F.; Lynch, M.; Wang, H.; Song, P.; Liu, Z. Strong self-healing close-loop recyclable vitrimers via complementary dynamic covalent/non-covalent bonding. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 500, 157418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madduluri, V.R.; Bendi, A.; Chinmay; Maniam, G.P.; Roslan, R.; Ab Rahim, M.H. Recent advances in vitrimers: A detailed study on the synthesis, properties and applications of bio-vitrimers. J. Polym. Environ. 2025, 33, 301–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, M.V.; Tancredi, G.P.C.; Vignali, G. The Recycling Technologies of Mono-material and Multilayer Plastic Film: A Descriptive Literature Review. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2024, 58, 469–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Zhan, S.; Zhou, M.; Xu, X.; You, F.; Zheng, H. A Powerful Strategy for Carbon Reduction: Recyclable Mono-Material Polyethylene Functional Film. Polymers 2024, 16, 2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajanayagam, H.; Beatini, V.; Poologanathan, K.; Nagaratnam, B. Comprehensive evaluation of flat pack modular building systems: Design, structural performance, and operational efficiency. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 95, 110099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Ye, G.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, H.; Huo, S.; Liu, Z. Closed-loop recyclable, self-catalytic transesterification vitrimer coatings with superior adhesive strength, fire retardancy, and environmental stability. ACS Mater. Lett. 2024, 7, 210–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.S.G.; Restivo, J.; Orge, C.A.; Pereira, M.F.R.; Soares, O.S.G. Green synthesis of carbon coated macrostructured catalysts: Optimized methodology and enhanced catalytic performance. Appl. Mater. Today 2024, 38, 102158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jouyandeh, M.; Seidi, F.; Habibzadeh, S.; Hasanin, M.S.; Wiśniewska, P.; Rabiee, N.; Vahabi, H.; Ramakrishna, S.; Saeb, M.R. An overview of green and sustainable polymeric coatings. Surf. Innov. 2024, 12, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, U.; Ahmad, F.; Awais, M.; Naz, N.; Aslam, M.; Urooj, M.; Moqeem, A.; Tahseen, H.; Waqar, A.; Sajid, M.; et al. Sustainable catalysis: Navigating challenges and embracing opportunities for a greener future. J. Chem. Environ. 2023, 2, 14–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayanan, N.; Ravichandran, B.; Emayavaramban, I.; Liu, H.; Su, H. Advancements in Non-Precious Metal Catalysts for High-Temperature Proton-Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells: A Comprehensive Review. Catalysts 2025, 15, 775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Zhu, F.; Ren, E.; Zhu, G.; Lu, G.P.; Lin, Y. Recent advances in carbon-based iron catalysts for organic synthesis. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 3462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, S.D.; Blum, A.; Weber, R.; Kannan, K.; Rich, D.; Lucas, D.; Koshland, C.P.; Dobraca, D.; Hanson1, S.; Birnbaum , L.S. Halogenated flame retardants: Do the fire safety benefits justify the risks? Rev. Environ. Health 2010, 25, 261–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabet, M. Advancements in halogen-free polymers: Exploring flame retardancy, mechanical properties, sustainability, and applications. Polym.-Plast. Technol. Mater. 2024, 63, 1794–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.N.; Zhao, H.B.; Chen, M.J.; He, L.; Fang, D.X.; Guo, S.Q.; Zeng, F.R.; Wang, Y.Z. Eco-Friendly Self-Adaptive Catalytic Strategy for Plastics Lifecycles: Achieving Green Preparation, Superior Flame Retardancy, and Self-Driven Sustainability. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2419263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeboye, S.; Adebowale, A.; Siyanbola, T.; Ajanaku, K. Coatings and the environment: A review of problems, progress and prospects. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2023; Volume 1197, p. 012012. [Google Scholar]

- Nartita, R.; Ionita, D.; Demetrescu, I. Sustainable coatings on metallic alloys as a nowadays challenge. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konwar, M.; Boruah, R.R. Textile industry and its environmental impacts: A review. Indian J. Pure Appl. Biosci. 2020, 8, 134–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovett, A.P.; Browning-Samoni, L.; Freeman, C. Fashion to Dysfunction: The Role of Plastic Pollution in Interconnected Systems of the Environment and Human Health. Textiles 2025, 5, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, N. The Environmental Impact of Fashion. In Threaded Harmony: A Sustainable Approach to Fashion; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2024; pp. 5–16. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Q.; Chen, S.; Sun, L.; Qiao, C.; Li, X.; Wang, L. Calculation and evaluation of cotton lint carbon footprint based on different cotton straw treatment methods: A case study of Northwest China. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 484, 144374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, H.Y.; Wang, B.X.; Li, J.; Cheng, D.H.; Lu, Y.H. Highly breathable and abrasion-resistant membranes with micro-/nano-channels for eco-friendly moisture-wicking medical textiles. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 3071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, K.; Yu, S.; Radu, A.; Xu, Y.; Saad, J.M.; Mohamed, B.A.; Li, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, Z.; Zhou, H. Renewable production of nylon precursors from lignin. Cell Rep. Sustain. 2025, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanović, T.; Hischier, R.; Som, C. Bio-based polyester fiber substitutes: From GWP to a more comprehensive environmental analysis. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 2993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorreta, G.; Maesani, C.; Alini, S.; Blangetti, M.; Prandi, C. Towards fiber-to-fiber recycling of synthetic textile wastes: The problem of decolorization. Waste Manag. 2025, 205, 114979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Yang, Y. Sustainable Transition of the Global Semiconductor Industry: Challenges, Strategies, and Future Directions. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Dong, D.; Li, Q.; Zhang, R.; Udrea, F.; Wang, H. Wide-bandgap semiconductors and power electronics as pathways to carbon neutrality. Nat. Rev. Electr. Eng. 2025, 2, 155–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevels, A. The challenge of introducing design for the circular economy in the electronics industry: A proposal for metrics. Circ. Econ. 2023, 2, 100051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Wong, C.W.; Li, C. Circular economy practices in the waste electrical and electronic equipment (WEEE) industry: A systematic review and future research agendas. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 365, 132671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, H.; Aggarwal, R.; Garg, P. Circular economy implementation in the electronics sector: A systematic literature review and future research directions. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2025, 12, 2509794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, K.; Carniello, S.; Beni, V.; Sudheshwar, A.; Malinverno, N.; Alesanco, Y.; Torrellas, M.; Harkema, S.; De Kok, M.; Rentrop, C.; et al. Defining and Achieving Next-Generation Green Electronics: A Perspective on Best Practices Through the Lens of Hybrid Printed Electronics. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 117135–117161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjana, E.; Aiswariya, K.; Prathish, K.; Sahoo, S.K.; Jayasankar, K. Recovery and recycling of silica fabric from waste printed circuit boards to develop epoxy composite for electrical and thermal insulation applications. Waste Manag. 2025, 198, 174–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dušek, K.; Koc, D.; Veselý, P.; Froš, D.; Géczy, A. Biodegradable Substrates for Rigid and Flexible Circuit Boards: A Review. Adv. Sustain. Syst. 2025, 9, 2400518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Wagih, M. Circular Wireless RF Systems With Recyclable and Degradable Components Based on Additively-Manufactured Liquid Metal Interconnects. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Regul. Pap. 2025, 72, 6924–6935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, M.; Kettle, J.; Dahiya, R. Electronic Waste Reduction Through Devices and Printed Circuit Boards Designed for Circularity. IEEE J. Flex. Electron. 2022, 1, 4–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedema, M.; Rosenbaum, H. Socio-technical issues in the platform-mediated gig economy: A systematic literature review: An Annual Review of Information Science and Technology (ARIST) paper. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2024, 75, 344–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gembali, V.; Kumar, A.; Sarma, P. Analysis and influence mapping of socio-technical challenges for developing decarbonization and circular economy practices in the construction and building industry. Ann. Oper. Res. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Otaibi, A. Barriers and enablers for green concrete adoption: A scientometric aided literature review approach. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larrue, P. Challenges and opportunities of mission-oriented innovation policies for realising transformative agendas: General principles and application to the case of the fight against climate change. In Transformative Mission-Oriented Innovation Policies; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2025; pp. 119–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kattel, R.; Mazzucato, M. Mission-oriented innovation policies in Europe: From the normative to the epistemic turn? In Transformative Mission-Oriented Innovation Policies; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2025; pp. 78–97. [Google Scholar]

- Russo, C.; Sansone, M.; Colamatteo, A.; Pagnanelli, M.A. Sustainability Standards: Voluntary Versus Mandatory Regulation; Technical Report JRC130619; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Climate Action. 2040 Climate Target: Reducing the EU’s Net Greenhouse Gas Emissions by 90% by 2040; European Commission: Brussel, Belgium, 2025; Available online: https://climate.ec.europa.eu/eu-action/climate-strategies-targets/2040-climate-target_en (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- U.S. Green Building Council. How to Select the Right LEED Rating System; U.S. Green Building Council: Washington, DC, USA, 2022; Available online: https://www.usgbc.org/articles/how-select-right-leed-rating-system (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- ISO 22057:2022; Sustainability in Buildings and Civil Engineering Works—Data Templates for the Use of Environmental Product Declarations (EPDs) for Construction Products in Building Information Modelling (BIM). International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; Technical Committee: ISO/TC 59/SC 17. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/72463.html (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Driving Climate Action. The Climate Group Inc. Nonprofit Organisation Website, 2025. New York, US. Available online: https://www.theclimategroup.org/ (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- International Energy Agency (IEA); UN Climate Change High-Level Champions. Breakthrough Agenda Report 2024: Accelerating Sector Transitions Through Stronger International Collaboration. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/breakthrough-agenda-report-2024 (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- Practical Guide for Policymakers on Protecting and Promoting Civic Space; Technical Report; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Hobé, T.R.; Vermeulen, W.J.V. Analysing Quality Assurance Levels in Extended Producer Responsibility-Regulated Recycling Sectors. Circ. Econ. Sustain. 2024, 4, 3025–3057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, A.N.; Kaaret, K.; Torres Morales, E.; Piirsalu, E.; Axelsson, K. Green Public Procurement: A Key to Decarbonizing Construction and Road Transport in the EU; Burton, L., Ed.; Sei Report; Stockholm Environment Institute: Stockholm, Sweden, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L. Green public procurement is a pivotal policy instrument for advancing urban low-carbon transitions: Evidence from 285 Chinese cities. Land 2025, 14, 1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabon-Dhersin, M.L.; Raffin, N. Cooperation in green R &D and environmental policies: Tax or standard. J. Regul. Econ. 2024, 66, 205–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Office of the Federal Chief Sustainability Officer. Federal Buy Clean Initiative; Council on Environmental Quality: Washington, DC, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.sustainability.gov/archive/biden46/buyclean/index.html (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Green Public Procurement. Procuring Goods, Services and Works with a Reduced Environmental Impact Throughout Their Life Cycle; European Commission, Directorate-General for Environment: Brussels, Belgium, 2025; Available online: https://green-forum.ec.europa.eu/green-business/green-public-procurement_en (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Sharmila, E.; Ronja, B.; Liesbeth, C. Monitoring Progress in Green Public Procurement: Methods, Challenges, and Case Studies; International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD): Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2024; Available online: https://www.iisd.org/system/files/2024-03/monitoring-green-public-procurement.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- European Platform on LCA ∥ EPLCA. European Commission, Joint Research Centre: Ispra, Italy, 2024. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/funding-tenders/opportunities/portal/screen/opportunities/tender-details/docs/6b3e4886-43d4-46fe-a94d-67f7ee913ca8-CN/.01%20Invitation_to_tender_EC-JRCIPR2024OP1781_Apollo%20thermal%20control%20300924_V2.pdf (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- Circular Built Environment. World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD): Geneva, Switzerland, 2025. Available online: https://www.wbcsd.org/actions/circular-built-environment/ (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- OECD. Mission-Oriented Innovation Policies for Net Zero: How Can Countries Implement Missions to Achieve Climate Targets? Technical Report; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union. Regulation (EU) 2024/1781 of the European Parliament and of the Council; EUR-Lex: Brussels, Belgium, 2024; Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2024/1781/oj/eng (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Khurshid, A.; Rauf, A.; Qayyum, S.; Calin, A.C.; Duan, W. Green innovation and carbon emissions: The role of carbon pricing and environmental policies in attaining sustainable development targets of carbon mitigation—Evidence from Central-Eastern Europe. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 25, 8777–8798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, M.; Jijian, Z.; Sharif, A.; Magazzino, C. Evolving waste management: The impact of environmental technology, taxes, and carbon emissions on incineration in EU countries. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 364, 121440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengesha, I.; Roy, D. Carbon pricing tipping points can induce rapid emissions reductions while maintaining growth and equity. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demski, J.; Dong, Y.; McGuire, P.; Mojon, B. Growth of the Green Bond Market and Greenhouse Gas Emissions; BIS Quarterly Review; BIS: Basel, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 53–71. Available online: https://www.bis.org/publ/qtrpdf/r_qt2503d.pdf (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- van Riet, R.; Hills, A. First Movers Coalition: Status Report; World Economic Forum: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024; Available online: https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_First_Movers_Coalition_Status_Report_2024.pdf (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- Climate Group. ConcreteZero: Specifications Report; Climate Group: London, UK, 2025; Available online: https://www.theclimategroup.org/sites/default/files/2025-05/Climate%20Group%2025476%20-%20ConcreteZero%20-%20Specifications%20Report.pdf (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- Püchel, L.; Wang, C.; Buhmann, K.; Brandt, T.; von Schweinitz, F.; Edinger-Schons, L.M.; vom Brocke, J.; Legner, C.; Teracino, E.; Mardahl, T.D. On the pivotal role of data in sustainability transformations. Bus. Inf. Syst. Eng. 2024, 66, 831–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solaimani, S. From compliance to capability: On the role of data and technology in environment, social, and governance. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Open EPD Forum: Brussels, Belgium. 2025. Available online: https://www.open-epd-forum.org/ (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- Aragón, A.; Alberti, M. Limitations of machine-interpretability of digital EPDs used for a BIM-based sustainability assessment of construction assets. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 80, 104364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulea, M.; Miron, R.; Muresan, V. Digital product passport implementation based on multi-blockchain approach with decentralized identifier provider. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 4874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panza, L.; Bruno, G.; Lombardi, F. Integrating absolute sustainability and social sustainability in the digital product passport to promote industry 5.0. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Wang, L.; He, S.; Liu, J. Zero-carbon-driven multi-energy coordinated sharing model for building cluster. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 430, 139658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, M. Revolutionizing supply chain and circular economy with edge computing: Systematic review, research themes and future directions. Manag. Decis. 2024, 62, 2875–2899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugoni, E.; Shumbanhete, B.; Nyagadza, B. The Nexus Between Circular Economy (CE) and Sustainable Supply Chain Management (SSCM): A Systematic Literature Review and Mapping of Future Research Agenda. Circ. Econ. Sustain. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heeß, P.; Rockstuhl, J.; Körner, M.-F.; Strüker, J. Enhancing trust in global supply chains: Conceptualizing data sharing mechanisms for Digital Product Passports. Electron. Mark. 2024, 34, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psarommatis, F.; May, G. Digital product passport: A pathway to circularity and sustainability in modern manufacturing. Sustainability 2024, 16, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fares, N.; Islam, M.S.; Jauhar, S.K.; Kucukaltan, B. Towards an International Digital Product Passport: The New Paradigm of a Worldwide Circular Economy. Circ. Econ. Sustain. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shee Weng, L. Digital Product Passports: Transforming Industries Through Transparency, Circularity, and Compliance; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mission Innovation. The Materials for Energy (M4E); Mission Innovation: Paris, France, 2025; Available online: https://mission-innovation.net/platform/materials-for-energy-m4e/ (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- Stier, S.P.; Kreisbeck, C.; Ihssen, H.; Popp, M.A.; Hauch, J.; Malek, K.; Reynaud, M.; Goumans, T.; Carlsson, J.; Todorov, I.; et al. Materials acceleration platforms (MAPs): Accelerating materials research and development to meet urgent societal challenges. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2407791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Economic Forum. First Movers Coalition: 120 Commitments for Breakthrough Industrial Decarbonization Technologies; World Economic Forum: Davos-Klosters, Switzerland, 2024; Available online: https://www.weforum.org/press/2024/01/wef24-first-movers-coalition-commitments/ (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- Brankley, L.; Camci, L.; Tugrul, A.; Karadayi, B.; Knight, D. Embodied carbon over the life cycle of reinforcing steels: Carbon emissions associated with modules A1–A3 product stage and A4–A5 construction stage. In Proceedings of the International Symposium of the International Federation for Structural Concrete; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 1075–1083. [Google Scholar]

- Global Cement and Concrete Association (GCCA). GCCA Launches Low-Carbon Cement and Concrete Definitions; Global Cement and Concrete Association (GCCA): London, UK, 2025; Available online: https://gccaepd.org/blog/gcca-launches-low-carbon-cement-and-concrete-definitions (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- Kirchherr, J.; Hartley, K.; Tukker, A. Missions and Mission-Oriented Innovation Policy for Sustainability: A Review and Critical Reflection. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2023, 47, 100721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Principle | Design Question | Representative Metrics/Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Performance alignment | Does the material deliver the required function with lower impact per unit service? | Functional carbon intensity (kg CO2e per MPa·year, R-value·m2, S·m−1 ); demonstrated service life and durability |

| Cleaner process and circular design | Is the material produced with minimal hazard, waste, and energy, and designed for reuse/repair/separation? | PMI, E-factor, solvent intensity and recovery rate; cradle-to-gate GWP (kg CO2e/kg); documented disassembly and reuse strategy; EN 15804/ISO 21930 disclosures |

| Criticality and responsible sourcing | Does performance depend on scarce, high risk, or toxic inputs, or can abundant, lower toxicity alternatives be used and recovered? | Criticality/supply risk score; toxicological classification; % of high risk element recoverable at end of life; compliance with critical raw material guidance |

| End-of-life planning | Is there a technically validated recovery pathway that preserves value instead of creating unmanaged waste? | Actual recovery yield (%); recycled or bio based content (%); number of realistic reuse/repair cycles; presence of a Digital Product Passport or EPD documenting composition and handling |

| Dataset | Domain | Description | Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Materials Project [117] | Inorganic Crystals | DFT calculated properties for over 150,000 crystalline inorganic materials, including formation energies, bandgaps, and elastic tensors. | Solid state materials design, phase stability, battery and thermoelectric material screening |

| Open Catalyst [118] | Catalysis | Over 20 million DFT and ML simulated adsorption trajectories across catalyst surfaces relevant to energy and decarbonization. | Catalyst discovery for CO2 reduction, ammonia synthesis, and hydrogen production |

| Polymer Genome [119] | Polymers | Structure–property relationships for thousands of polymers, including mechanical, thermal, and electronic properties, with support for bio based and degradable polymers. | High throughput screening of sustainable and biodegradable polymer candidates |

| QMOF [120] & OMDB [121,122] | MOFs & Organic Crystals | Quantum properties and electronic structure data for metal–organic frameworks (QMOF) and over 26,000 organic crystals (OMDB). | Gas separation, storage, optoelectronic applications, quantum materials |

| SustainBench [123] | Sustainability Benchmarks | A diverse benchmark suite for machine learning tasks in sustainability, including emissions prediction, infrastructure quality, and satellite image classification. | Socio-environmental forecasting, sustainability analytics, global development monitoring |

| Material | Embodied Carbon (kg CO2e kg−1 ) | Lifecycle Sustainability Advantage |

|---|---|---|

| Fly ash/GGBFS blended cement | 30-50% lower vs. OPC [158] | Utilizes industrial by products; readily scalable |

| Geopolymer concrete | Up to 80–90% lower [159,160] | Eliminates clinker; high durability; alkali activation |

| PLA (bioplastic) | 20–70% lower [162,163] | Renewable feedstock; industrially compostable |

| Vitrimers/DCNs | Closed loop reuse enabled [164,165] | Reprocessable thermosets; high mechanical stability |

| Fe–N–C catalysts | ≈90% cost/emission savings [81] | Replaces scarce PGMs in fuel cells and electrolysers |

| Hemp fiber textiles | 60–80% lower vs. cotton [166] | Low water use; carbon sequestering crop |

| Bio nylon (e.g., nylon-11) | ≈50% lower vs. nylon-6,6 [173] | Fossil free feedstock; comparable durability |

| Recycled cellulose (fiber-to-fiber) | 60–90% lower vs. virgin cotton [95] | Fiber recovery without downcycling |

| Vitrimer PCBs (vPCBs) | 95% polymer and fiber recovery [174] | Dynamic covalent recycling; low energy depolymerization |

| LMV conductive composites | Moderate high [175] | Recyclable, self healing circuits; printed electronics |

| Dissolvable circuit substrates | 100% material reclaim via aqueous recovery [176] | Eliminates incineration; facilitates e-waste disassembly |

| Program or Policy | Region | Key Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Buy Clean (e.g., California; U.S. federal low embodied carbon initiatives) | USA | Sets global warming potential (GWP) limits for cement, concrete, steel, and asphalt in public projects; requires Environmental Product Declarations (EPDs) |

| EU Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation (ESPR) | EU | Creates legally binding design for circularity requirements and mandates Digital Product Passports with product level data on composition, durability, reparability, recycled content, and carbon footprint [233]. |

| Horizon Europe (Cluster 4: Digital, Industry and Space) | EU | Funds low carbon industrial processes, materials circularity, and resource security to support EU industrial resilience and climate targets [234]. |

| LEED v4.1/comparable building rating schemes | Global | Awards credits for product transparency, recycled content, low carbon concrete, and material reuse; channels private sector demand toward verified low impact materials [235]. |

| ISO 14040/44; ISO 21930; EN 15804; EN ISO 22057 | Global/EU | Define harmonized rules for lifecycle assessment (LCA), building product category rules, embodied carbon reporting, and machine readable digital EPD data structures [236]. |

| Mission Innovation, First Movers Coalition, ConcreteZero/SteelZero | Global | Align public R&D funding with corporate offtake commitments for near zero steel, cement/concrete, shipping fuels, and other hard to abate sectors [237,238]. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alamandi, M. From Fossil to Function: Designing Next Generation Materials for a Low Carbon Economy. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10254. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210254

Alamandi M. From Fossil to Function: Designing Next Generation Materials for a Low Carbon Economy. Sustainability. 2025; 17(22):10254. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210254

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlamandi, Morgan. 2025. "From Fossil to Function: Designing Next Generation Materials for a Low Carbon Economy" Sustainability 17, no. 22: 10254. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210254

APA StyleAlamandi, M. (2025). From Fossil to Function: Designing Next Generation Materials for a Low Carbon Economy. Sustainability, 17(22), 10254. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210254