Abstract

Saltwater Intrusion (SWI) is threatening coastal archaeological sites, particularly in Crotone, southern Italy. The study area has been experiencing notable SWI due to over-pumping of groundwater, rising land subsidence, and climate change. Consequently, this study examines the applicability of polycaprolactone (PCL), a common biodegradable polymer, as a protective barrier for archaeological conservation. PCL films were synthesized via solvent casting and dried under controlled conditions. Physicochemical properties of the films were evaluated using six analytical techniques: (1) contact angle measurements for surface hydrophobicity, (2) Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) for chemical stability, (3) Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) for morphological characterization, (4) permeability testing for evaluating saltwater diffusion, (5) mechanical testing for tensile properties, and (6) biodegradability assays for degradation rates. All samples were evaluated at 0, 30, 60, and 90 days in natural seawater. Results from these tests indicate that unmodified PCL films exhibited moderate hydrophobicity, partial hydrolytic degradation, resistance to permeability, declining mechanical strength, and limited biodegradability over the testing period.

1. Introduction

Coastal archaeological sites are consistently experiencing the impact of many imminent threats: erosion, rising sea level, groundwater pollution, salinization, and climate change. The actions caused by increased human pressures related to urbanization, agriculture, and development contribute to the existing impacts on coastal archaeological heritage.

The expected number of at-risk coastal archaeological sites is likely to increase substantially by the years 2050 and 2100 if greenhouse gas emissions remain high [1,2,3]. As a result of natural or human-induced erosion, archaeological features have already been lost in areas such as Libya, New Zealand, and the Mediterranean [4,5]. The implications of saltwater intrusion and agricultural or urban contamination are also contributing to the damage of subsurface remains in places such as Florida and Italy [6,7]. Moreover, the growth of urban centers, poor land management and unsustainable agricultural practices are compounding the previously noted risk factors, along with increased extraction of potable groundwater, land subsidence, and the destruction of heritage sites [3,7,8,9]. Submerged and buried archaeological sites (as in the current study area of Crotone) can be especially vulnerable because the preservation of deposits largely depends on the stability of their depositional environment [10,11]. For example, the ancient Greek temple of Hera Lacinia at Capo Colonna (near Crotone) may ultimately be affected by its proximity to the coast and the current threat of SWI, which could endanger the integrity of the site.

The traditional protective materials used at archaeological sites, commonly geomembranes and concrete, are non-biodegradable materials and frequently conflict with ethical conservation considerations due to the environmental damage incurred and the need for manual extraction in a non-destructive manner. To address these issues, researchers have begun investigating biodegradable, eco-compatible polymers that can perform protective functions and promote environmental responsibility [12,13].

Polycaprolactone (PCL) is emerging as a promising semi-crystalline, hydrophobic, and processable material that forms thin films with relatively low water sorption [14]. On the other hand, PCL exhibits greater durability than other biodegradable polymers, such as Polylactic Acid (PLA) and Polybutylene Succinate (PBS) [15,16].

The protective efficiency of biodegradable polymers is highly sensitive to environmental conditions. Among these materials, PCL has been extensively examined for its hydrolytic degradation in various aqueous media, including buffer solutions, artificial saliva, and seawater. Factors like salinity, temperature, and pH strongly influence its rates of hydrolysis and degradation. For instance, extreme salinity accelerates hydrolysis and mass loss, thereby affecting barrier performance [17]. In phosphate-buffered saline, polymers with larger surface areas tend to degrade faster because bulk hydrolysis promotes random chain scission and gradual weight reduction [17,18,19]. Conversely, in artificial saliva, a mucin coating limits water access to the polymer’s surface, resulting in a much slower degradation rate, while pH and temperature have only minor effects [20]. In marine environments, PCL degrades slowly, but it can be accelerated by copolymerization with hydrophilic monomers or microbial enzyme-mediated surface erosion [21,22,23].

The hydrolytic properties of PCL can be tailored through surface modification or polymer blending. For instance, introducing hydrophilic functional groups leads to increased water absorption and hydrolysis while enhancing biocompatibility [19,24,25,26].

Despite these improvements, biodegradable polymers such as PCL can degrade under microbial and environmental conditions. Uncontrolled microbial growth leads to the deterioration of the artifacts. Microorganisms may release acids, pigments, and enzymes, which cause staining and the degradation of heritage materials, while biofilm formation can alter surface chemistry and accelerate degradation [27,28,29].

The objective of this study is, therefore, to evaluate the long-term behavior of PCL films under natural seawater exposure at 15 °C, considering their hydrolytic stability, mechanical resistance, and biodegradability for potential use as sustainable barrier materials for the conservation of coastal archaeological sites.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Polycaprolactone (PCL) with an average molecular weight of (Mn ≈ 80,000 g/mol) was acquired from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) without further purification. Tri-ethyl phosphate (TEP) was selected as a green solvent which supports our sustainable goals. Seawater samples of the Ionian Sea from the study location (Crotone city) were collected in March 2024.

2.2. Film Preparation

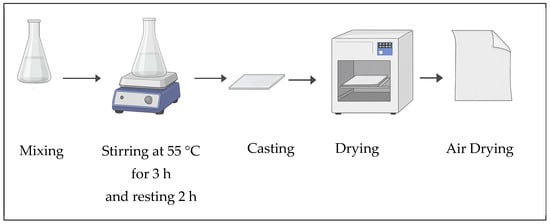

PCL films were made with TEP as the green solvent, as shown in (Figure 1). A total of 7 g of TEP was added to a glass flask, followed by 1 g of PCL, which was added in three equal portions of 0.33 g each. Each portion was dissolved completely before the next portion was added. Once mixed, the TEP/PCL was stirred at 55 °C for 3 h to produce a uniform solution. The solution was left to rest for 2 h before pouring the solution onto a flat glass plate. The films were placed in an oven at 55 °C to evaporate the solvent. Once the solvent evaporated, films were detached from the glass by immersing them in deionized water until the films were released from the glass and were then air-dried overnight at room temperature for testing.

Figure 1.

Conceptual illustration of PCL film preparation.

The films were cold-cut into strips of 3 cm × 3 cm for the weight loss experiment and strips of 10 cm × 2 cm for mechanical strength tests. The average thickness of the films was measured as between 0.10 mm and 0.22 mm using a digital micrometer. All tests were performed in triplicate.

2.3. Ionian Seawater Immersion

To simulate the conditions of buried coastal artifacts, PCL films were placed in glass containers with natural seawater. Ionian seawater was used because of the similar saline conditions in the other coastal archaeological site of Crotone and the similar effects of the seawater intrusion there. The containers were placed in an environmental chamber at 15 °C, which was selected to simulate coastal artifacts that would typically be buried beneath the earth, especially in cooler, stable environmental conditions. The measured temperature provided stabilized laboratory observations but also kept in mind the real-world conditions with static immersion and wat-ant dynamic water-moving effects similar to the conditions in real environments in the field.

2.4. Surface Hydrophobicity: Contact Angle Measurements

To determine the wettability of the surface, a goniometer was used, and the sessile drop method was performed. Each film surface had a droplet of two microliters of deionized water deposited on it, and the contact angle was measured after waiting 20 s. Each sample was measured three times, and the average value was calculated. Any changes in contact angle allow an outcome to be interpreted as posing an increased risk of deterioration of artifacts. A hydrophilic surface contributes to less-desirable interactions between water and cultural heritage materials.

2.5. Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

The chemical structural changes were followed by attenuated total reflectance Fourier-transform infrared (ATR-FTIR) spectroscopy (500–4000 cm−1, 4 cm−1). All spectra are the means of thirty-two scans. The observation of a diminishment in the absorption peaks related to ester carbonyl (approximately 1720 cm−1) and new peaks related to hydroxyl (approximately 3300 cm−1) or the arousal of new peaks for carboxylate groups (approximately 1600 cm−1) can be attributed to hydrolytic degradation. FTIR data assists in demonstrating the chemical instability risk and impacts on the stability of the artifact.

2.6. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

The morphologies of the films were assessed at 0, 30, 60, and 90 days using a ZEISS Scanning Electron Microscope (ZEISS, Oberkochen, Germany). All the samples were sputter coated in gold to improve the conductivity of the samples. Micrographs taken at 500× to 2000× magnification were documented to record surface roughness, pitting, and cracking during the degradation of the surface films. The PM was analyzed via SEM to determine how the microstructure impacted any physical vulnerabilities that might jeopardize archaeological artifacts.

2.7. Seawater Permeability Testing

Seawater permeability tests are significant methods of evaluating the performance of films to inhibit saline infiltration, which ultimately affects the amount of protection offered to the artifacts. Water permeation tests on the films used in the study were conducted using a dead-end filtration cell (UHP-25, Strelitech, Osaka, Japan) with a feed pressure of 0.5 bar and a magnetic stirrer at a medium speed (190 m) at room temperature. As time went on, mass loss was recorded over continuous periods as the system was stirred. Conductivity was also measured in the receiving chamber over a 6 h period. The higher the permeability, the greater the likelihood of salt damage occurring in the artifacts.

where J: Permeate flux (L/m2·h); Q: Volume of permeate collected (L); A: Membrane area (m2); t: Time (hr).

where P: Permeability (L/m2·h·bar); J: Permeate flux (L/m2·h); ΔP: Applied pressure difference (bar).

2.8. Mechanical Strength Testing

The mechanical integrity of the samples was tested using a Zwick/Roell Z2.5 testing unit (BTC-FR2.5TN-D09, Zwick Roell Group, Ulm, Germany). Film strips were allowed to stretch, and at a constant rate of elongation (5 mm/min), were evaluated at rupture. The values of tensile strength (MPa), Young’s modulus (MPa), and elongation at break (%) were produced, which could indicate the long-term structural integrity of the polymer. An increase in the loss of those mechanical properties could increase the susceptibility of the archaeological object to physical stress.

2.9. Biodegradability Assessment

A biodegradability evaluation was completed by tracking the loss of mass of the samples (using the sample’s dry mass) after submersion in Crotone seawater. There was no soil or sediment. The experiment was focused on polymer–seawater interaction under controlled laboratory conditions. After weighing the samples, they were submerged in the seawater for an assigned time, rinsed with freshwater, dried at an ambient temperature, and weighed again. The mass loss was finally estimated as a percentage to approximate the percent of hydrolytic biodegradation during the treatment. Changes to the sample color also provide observable qualitative data. The property of biodegradability was conceptualized as a guarantee that the selected protective materials would not produce excessive long-term detriment to the environment, while preserving archaeological integrity over time.

where: W0: the initial weight of the sample before biodegradation (g); Wt: the weight of the sample after biodegradation (g).

3. Results and Discussion

The degradation behavior of unmodified polycaprolactone (PCL) films submerged in actual seawater for 90 days was described, utilizing different analytical techniques to determine changes in its physical, chemical, and mechanical properties and its permeability. The following section describes the changes observed in the films’ surface hydrophobicity, chemical structure, micro-morphology, saltwater permeability, mechanical strength, and total mass loss.

3.1. Seawater Characteristics

The composition of Ionian seawater collected from Crotone was determined by an Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometer (Analytik Jena Contra AA 700, Jena, Germany) for cations and Ion Chromatography (Metrohm 930 Compact IC Flex, Herisau, Switzerland) for anions. The pH of this seawater was measured directly at 15 °C using a calibrated pH meter (Hanna Instruments HI2211, Limena, Italy) with a combined glass electrode. The results are representative of typical Mediterranean marine conditions. The measured pH and major ionic concentrations are summarized in (Table 1).

Table 1.

Ionic composition of seawater from Crotone (Ionian coast, Crotone, Italy).

3.2. Surface Hydrophobicity

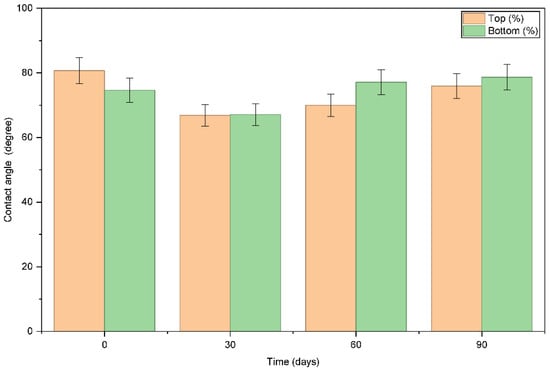

Contact angle analysis was achieved for both upper and lower surfaces of PCL films over the 90-day simulated exposure period to the salinity of seawater, demonstrating in (Figure 2). Day 0 had average contact angles of 80.69° (top) and 74.64° (bottom), denoting moderate hydrophobicity. On day 30, contact angles decreased to 66.86° (top) and 67.10° (bottom), indicating increased surface wettability due to the interaction with saline. On day 60, the upper surface partially recovered to 69.99°, while the lower surface increased to 87.11°, indicating partial surface reorganization and uneven salt deposition between the two surfaces. An increase in surface polarity will elevate the affinity for water in the material and could catalyze degradation behavior. Day 90 was stable at 75.96° (top) and 78.67° (bottom), as outlined in the table below, indicating partial retention of hydrophobicity, while some altered surface dynamics persisted.

Figure 2.

The water contact angle of pure PCL films measured on their top and bottom surfaces after immersion in natural seawater (15 °C) for 0, 30, 60, and 90 days.

3.3. FTIR Spectroscopy

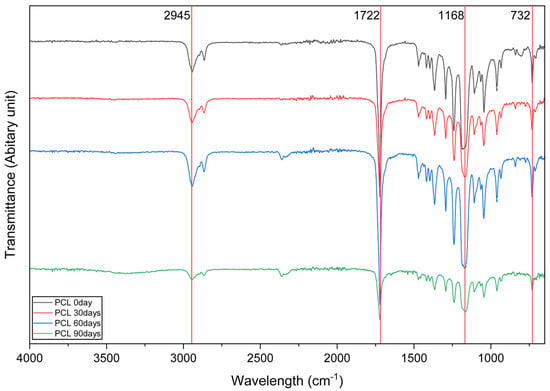

Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy was performed to confirm the chemical structure and functional groups of the synthesized polycaprolactone (PCL) through the evaluation of the PCL films at 0, 30, 60, and 90 days in natural saline, as shown in (Figure 3). FTIR spectroscopy was able to demonstrate PCL-specific absorption bands including CH2 asymmetric stretching (2946 cm−1), a strong ester carbonyl (C=O) absorption band (1718 cm−1), C–O–C stretching (1169 cm−1), and CH2 rocking (730 cm−1) over time. Although the absorption bands displayed in the FTIR spectra were relatively consistent over time, significantly lower absorbance intensity was noted over the same four time points, especially at 1718 cm−1 and 1169 cm−1. The change in intensity indicated decreasing chemical stability due to hydrolytic degradation of ester groups over time. No new absorption bands were produced beyond indicating the loss of chemical stability and change in structural integrity of the polymer backbone over time. The spectral analysis of PCL highlights the degradation in intensity following immersion at 30 days for carbonyl (1722 cm−1) and C–O–C (1168 cm−1) as time progressed to 60 and 90 days, respectively, confirming that the entire polymer suffered, to some extent, from hydrolytic degradation, which has previously been reported to be necessary for the biodegradability of PCL. The absorption bands that would normally have confirmed the establishment of secondary functional groups were not demonstrated in the FTIR measurements following the application of the saline exposure.

Figure 3.

FTIR spectra of PCL films undergoing immersion in natural seawater (15 °C) at 0, 30, 60, and 90 days, indicating variations in peak heights and symmetry, which indicated continuous hydrolytic degradation of the polymer structure.

The C=O absorption peak at around 1725 cm−1 is often discussed as being the main indicator for the presence of PCL [30]. Additionally, the aliphatic C-H stretching vibrations identified in the range of 2945 cm−1 and 2865 cm−1 have also been shown to be indicative of PCL’s presence in degraded composite materials [31]. Moreover, the peaks associated with C–O–C and C–C stretching vibrations at 1240 cm−1 and 1295 cm−1 have been similarly documented, verifying additional impacts concerning the crystalline nature of the polymer [32].

Overall, the FTIR values indicated a gradual reduction in the chemical stability of PCL over 90 days, while the absence of new absorption peaks confirmed that the main polymer structure remained intact.

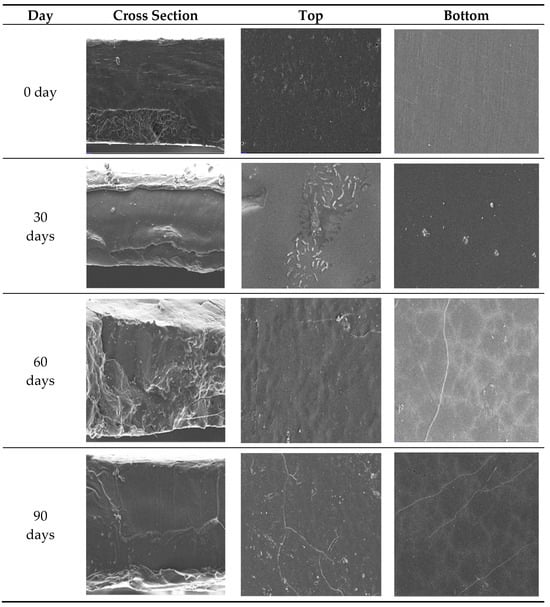

3.4. SEM Morphology

SEM images of the top, bottom, and cross-sections of PCL films (degradation time points of 0, 30, 60 days, and 90 days) are presented in (Figure 4). In the beginning, the surfaces of the films were smooth, homogenously formed, and free of cracks or pores, both films are trimmed, and in cross-section, appear compact and uniform. After 30 days, the cross-section began to show some roughness and slight delamination, while the top surface showed a few zealous aggregates and irregularities. The bottom surface exhibited small appearances of scattered deposits, which were likely due to salt crystallization. By 60 days, these features would become more pronounced. By 90 days the cross-section exhibited large cracks and layered structures, indicating that the internal structural integrity was breaking down. These changes in morphology occurred simultaneously to the changes in hydrophobicity and chemical stability, demonstrating how length of time in saline environments negatively impacts the barrier properties of unmodified PCL film.

Figure 4.

Representative SEM micrographs of PCL films with magnification and scale bars (2 µm and 10 µm) tested in natural seawater at 0, 30, 60, and 90 days with a temperature of 15 degrees.

3.5. Seawater Permeability

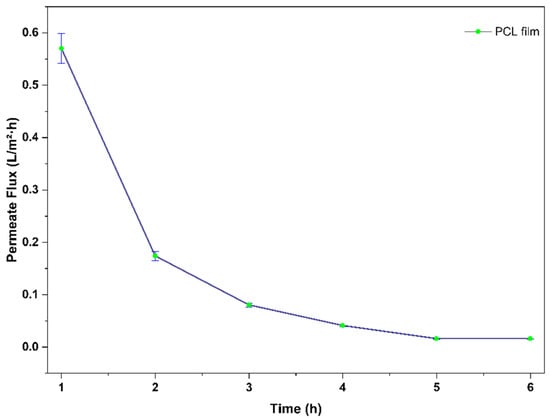

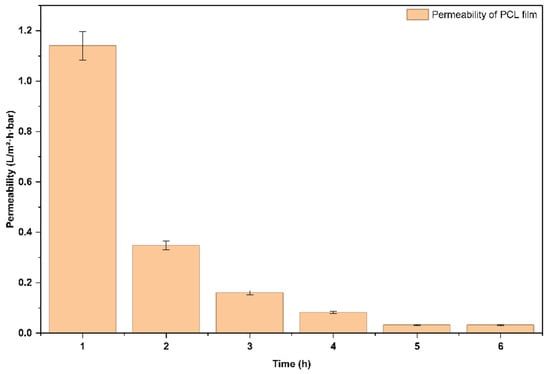

The water permeation performance of the PCL films was assessed with a dead-end filtration cell at a constant feeding pressure of 0.5 bar and at room temperature. The permeate flux (J) was determined by measuring mass change over time, and the average data can be seen in (Figure 5), with a dramatic loss in flux over the 6 h test. The initial flux was clocked at 0.57026 L/m2·h at 1 h, then dropped dramatically to 0.17379 L/m2·h at 2 h and continued to tail down to 0.01584 L/m2·h by 5 h, stabilizing there after at 6 h.

Figure 5.

Permeate flux of pure PCL film as a function of filtration time.

This pattern is consistent with the typical behavior of hydrophobic membranes in dead-end filtration systems, where fouling due to the accumulation of material on the membrane’s surface is a common challenge. For example, Bergamasco et al. (2024) studied PCL membranes produced through electrospinning, in which hydrophobic membranes accrete and eventually block pores under dead-end pressure quickly, similar to the rapid loss of flux described in our work, as demonstrated in [33]. Similarly, Nivedita and Joseph (2024) observed similar initial fluxes to the ones observed in our study, as well as films that produced with PCL deteriorated after time [34]. It was found that stable flux was attained beyond the 5 h time point, demonstrating that there is a steady state whereby either incremental fouling or structural changes are negligible or not recognizable.

Moreover, natural Seawater Permeability (P) started at 1.14052 L/m2·h·bar at 1 h and declined to 0.03168 L/m2·h·bar by 5 h, remaining constant at 6 h, as shown in (Figure 6). This decline in both flux and permeability advocates for a reduction in the film’s water transport efficiency over time due to fouling or the compaction of the PCL film under the applied pressure. This support is also confirmed by Zhang et al. (2024), where the authors conclude that a stable plateau region in permeability through ultrafiltration means that the cake layer is saturated [35].

Figure 6.

Seawater permeability of PCL films measured at different filtration times, indicating pore blocking and fouling effects during prolonged exposure.

The initial elevated permeate flux and permeability demonstrate that the PCL film had reasonable water permeability for the beginning of the filtration period due to its hydrophobicity and porous structure. The consistent permeate flux and permeability beyond 5 h (0.01584 L/m2·h and 0.03168 L/m2·h·bar, respectively) indicate that a stable condition had occurred, and thus further fouling or structure change was limited. These results capture the potential of the PCL film but also highlight the limitation of PCL for extended filtration without antifouling procedures, which could include surface modification or periodic cleaning during filtration. Future work will also include studying using higher pressures or using crossflow filtration to improve PCL performance.

3.6. Mechanical Properties

The mechanical outcomes indicate an ongoing deterioration of both the stiffness and tensile strength of PCL films over time in natural seawater. The tensile properties of PCL films were determined after 0, 30, 60, and 90 days of immersion in natural seawater and summarized in (Table 2). Initially, PCL films had a Young’s modulus of 240 ± 15 MPa, a tensile strength of 15 ± 1.2 MPa, and an elongation at break of 11.7 ± 1.1%, which demonstrates satisfactory mechanical integrity. After 30 days of immersion in saline (30 days), the Young’s modulus dropped to 181 ± 12 MPa, tensile strength dropped to 9.3 ± 0.8 MPa, and elongation at break slightly decreased to 10.3 ± 0.9%, all indices of mechanical integrity. At 60 days, Young’s modulus dropped to 173 ± 11MPa, tensile strength dropped to 4.5 ± 0.5MPa and elongation at break dropped to 7.8 ± 0.7%. At 90 days, Young’s modulus lowered again to 145 ± 10 MPa, tensile strength partially recovered to 9.9 ± 0.8 MPa and elongation at break increased to 11.0 ± 1.0%.

Table 2.

Mechanical properties of pure PCL films in natural seawater at different immersion times with constant temperature of 15 °C. Values are mean ± Standard Deviation (n = 5).

The decline in tensile strength from 15.3 MPa (0 d) to 4.5 MPa over the 60 d indicates the breaking down of the polymer chains in saline conditions. The slight recovery in tensile strength to 9.9 MPa on day 90 may be attributed to structural reorganization or a change in crystallinity due to some of the degraded polymer chains being realigned. The indicator of the elongation at break dropped to (7.8%) at 60 days, suggesting increased brittleness. Nonetheless, the high increase in tensile strength (11.0%) at 90 days may indicate plasticization effects due to water uptake that can improve ductility even if a degree of chemical degradation is occurring. Similar studies conducted by H. Tsuji (2002) indicated that when PCL was exposed to hydrolytic (aqueous) conditions, the hydrolysis of the amorphous portion of the polymer dominated how the overall properties changed [36]. Further, for seawater-degradable PCL films, G.X. Wang et al. (2021) provided evidence of a decline in mechanical strength due to time under immersion conditions and followed a parallel decline with both magnitudes and trends of mechanical strength observed [37]. Similarly, the research conducted by Lyu et al. (2019) demonstrated a comparable decline in mechanical properties, which, after days post-immersion, resulted in notable declines in the tensile strength of the PCL films tested [38].

The overall trend of this study lines up with previous studies indicating that PCL immersed in water and saline environments undergoes hydrolytic degradation and weakened mechanical properties after a certain period. The decline in average properties after 60 days and potential slight recoveries on day 90 would suggest a more complex relationship between hydrolytic degradation, crystallinity levels, and water uptake. Therefore, the mechanical properties of these films will still be limited for long-term viability unless further designed.

3.7. Biodegradability of PCL Films

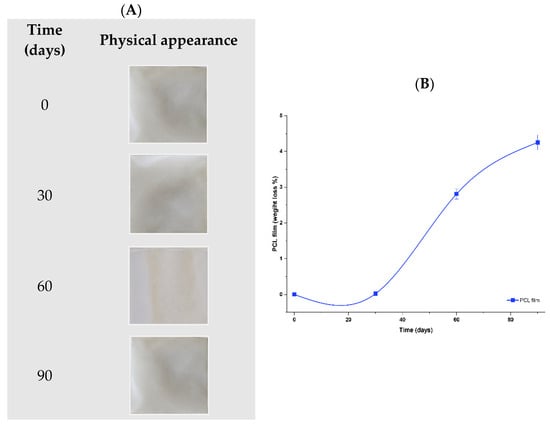

Gravimetric examination confirmed the active biodegradation of the PCL films over the 90-day period of exposure to natural seawater at 15 °C, illustrated in (Figure 7A). As a starting point, on day 0 of the experiment, there was no weight loss, indicative of the polymer having had good initial stability in the marine environment.

Figure 7.

Biodegradability of pure PCL films in natural seawater at 15 °C. (A) Physical appearance of the films after 0, 30, 60, and 90 days of immersion. (B) Weight loss (%) of PCL films as a function of incubation time, showing gradual degradation with increasing exposure duration.

Following 30 days of immersion, the films revealed a very minimal loss of 0.02%, again, indicating limited degradation at this early stage under cold seawater conditions. A reduction in temperature (15 °C) led to reduced hydrolytic cleavage of the ester bonds within the PCL polymer and slowed microbiological activity, which can both be highly influential on the rate of biodegradation of aliphatic polyesters.

Following 60 days, mass loss had increased significantly to 2.81%, suggesting that hydrolytic processes had progressed beyond the surface of the films and started to influence the bulk polymer structure.

Finally, on day 90, the weight loss of the films indicated 4.25%, indicating that there had been some continuing breakdown of the films over the time of the test period with relatively low overall breakdown. See (Figure 7B).

In examining the studies from other researchers, the amount of mass loss reported in the current study (~4.25% after 90 days at 15 °C) was lower than that reported for PCL films exposed to higher temperatures (25–30 °C) or to seawater with high biological activity [39]. Heimowska et al. (2017) [40] recorded the complete degradation of some PCL films after 6 weeks of testing in Baltic Sea water. However, the degradation of the PCL films was slow when the films were tested in less aggressive waterbodies [40]. Therefore, the results support that biodegradation of PCL takes place relatively slowly depending on temperature, microbial content, thickness of the films, and whether the films are crystalline or amorphous.

Overall, the findings of our study illustrate that PCL films degrade slowly under the influence of natural seawater at 15 °C and under the action of film-colonizing microbes. A mass loss of less than 5% after 90 days is consistent with previous observations for PCL films in seawater [40]. This condition indicates sufficient short-term stability while remaining capable of gradual biodegradation in marine conditions.

4. Conclusions

This study assessed the performance of unmodified polycaprolactone (PCL) films as biodegradable barriers for protecting archaeological sites from saltwater intrusion. In total, the 90-day exposure period evaluated how PCL performed against saline conditions for hydrophobicity, mechanical properties, and long-term stability. The reduction in contact angle, FTIR showing partial hydrolytic degradation of the PCL, increases in saltwater permeability, and loss in tensile strength all showed that unmodified PCL films can decline both structurally and functionally when exposed to saline conditions for a long duration. These results demonstrate the necessity of material changes, including the addition of nanofillers for improving hydrophobicity, chemical stability, resistance to permeability, and durability over time.

The 90-day exposure condition may not be a long enough duration to assess the long-term performance of PCL films in situ, nor did we consider chemical interactions with specific soil types or artifacts. Future research should employ field validation to further support laboratory performance under authentic environmental conditions, including varying temperature, soil conditions, and water movement, which may also include ongoing biological activity in the archaeological site. It will be important to set benchmarks for future performance, such as establishing acceptable levels of loss—such as less than 5% mass loss of the polymerized PCL over 12 months to protect archaeological assets. This will help future optimization studies on archaeological site protection, while meeting regulatory standards.

Despite these limitations, this study provides initial knowledge of PCL film’s performance in saline conditions and could be a foundation for the development of next-generation biodegradable materials that allow for environmental sustainability and preservation of cultural heritage.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.S. (Sergio Santoro), E.C. and S.S. (Salvatore Straface); Methodology, E.C., P.A., F.C., S.S. (Salvatore Straface) and M.F.L.R.; Validation, A.P.J.; Formal analysis, S.S. (Sergio Santoro); Investigation, A.P.J.; Writing—original draft, A.P.J.; Writing—review & editing, S.S. (Salvatore Straface); Visualization, M.F.L.R.; Supervision, S.S. (Sergio Santoro), E.C., P.A., F.C. and S.S. (Salvatore Straface); Project administration, M.F.L.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the Next Generation EU—Italian NRRP, Mission 4, Component 2, Investment 1.5, call for the creation and strengthening of ‘Innovation Ecosystems’, building ‘Territorial R&D Leaders’ (Directorial Decree n. 2021/3277)—project Tech4You—Technologies for climate change adaptation and quality of life improvement, n. ECS0000009. This work reflects only the authors’ views and opinions, neither the Ministry for University and Research nor the European Commission can be considered responsible for them.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hu, H.; Hewitt, R. Future climate risks to world cultural heritage sites in Spain: A systematic analysis based on Shared Socioeconomic Pathways. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2024, 113, 104855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howland, M.; Thompson, V. Modeling the potential impact of storm surge and sea level rise on coastal archaeological heritage: A case study from Georgia. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0297178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawson, T.; Hambly, J.; Kelley, A.; Lees, W.; Miller, S. Coastal heritage, global climate change, public engagement, and citizen science. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 8280–8286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, B.; Collings, B.; Dickson, M.; Ford, M.; Hikuroa, D.; Bickler, S.; Ryan, E. Regional implementation of coastal erosion hazard zones for archaeological applications. J. Cult. Herit. 2024, 67, 430–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfadaly, A.; Abutaleb, K.; Naguib, D.; Mostafa, W.; Abouarab, M.; Ashmawy, A.; Wilson, P.; Lasaponara, R. Tracking the effects of the long-term changes on the coastal archaeological sites of the Mediterranean using remote sensing data: The case study from the northern shoreline of Nile Delta of Egypt. Archaeol. Prospect. 2023, 30, 369–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stellato, L.; Coda, S.; Arienzo, M.; De Vita, P.; Di Rienzo, B.; D’Onofrio, A.; Ferrara, L.; Marzaioli, F.; Trifuoggi, M.; Allocca, V. Natural and Anthropogenic Groundwater Contamination in a Coastal Volcanic-Sedimentary Aquifer: The Case of the Archaeological Site of Cumae (Phlegraean Fields, Southern Italy). Water 2020, 12, 3463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecher, A.; Watson, A. Danger from beneath: Groundwater–sea-level interactions and implications for coastal archaeological sites in the southeast US. Southeast. Archaeol. 2021, 40, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, J.; Chamberlain, E.; Helmer, M.; Haire, E.; McCoy, M.; Van Beek, R.; Wang, H.; Yu, S. Preserving coastal environments requires an integrated natural and cultural resources management approach. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2025, 4, pgaf090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattei, G.; Rizzo, A.; Anfuso, G.; Aucelli, P.; Gracia, F. A tool for evaluating the archaeological heritage vulnerability to coastal processes: The case study of Naples Gulf (southern Italy). Ocean Coast. Manag. 2019, 179, 104876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, B.; Dickson, M.; Ford, M.; Hikuroa, D.; Ryan, E. Aotearoa New Zealand’s coastal archaeological heritage: A geostatistical overview of threatened sites. J. Isl. Coast. Archaeol. 2023, 19, 657–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westley, K.; Nikolaus, J.; Emrage, A.; Flemming, N.; Cooper, A. The impact of coastal erosion on the archaeology of the Cyrenaican coast of Eastern Libya. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0283703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Gandarillas, L.; Manteca, C.; Yedra, Á.; Casas, A. Conservation and Protection Treatments for Cultural Heritage: Insights and Trends from a Bibliometric Analysis. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2079-6412/14/8/1027?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Bher, A.; Mayekar, P.C.; Auras, R.A.; Schvezov, C.E. Biodegradation of Biodegradable Polymers in Mesophilic Aerobic Environments. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 12165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntrivala, M.A.; Pitsavas, A.C.; Lazaridou, K.; Baziakou, Z.; Karavasili, D.; Papadimitriou, M.; Ntagkopoulou, C.; Balla, E.; Bikiaris, D.N. Polycaprolactone (PCL): The biodegradable polyester shaping the future of materials—a review on synthesis, properties, biodegradation, applications and future perspectives. Eur. Polym. J. 2025, 234, 114033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samir, A.; Ashour, F.; Hakim, A.; Bassyouni, M. Recent advances in biodegradable polymers for sustainable applications. npj Mater. Degrad. 2022, 6, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrison, T.; Murawski, A.; Quirino, R. Bio-Based Polymers with Potential for Biodegradability. Polymers 2016, 8, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, F.; Misra, M.; Mohanty, A. Challenges and new opportunities on barrier performance of biodegradable polymers for sustainable packaging. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2021, 117, 101395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosworth, L.; Downes, S. Physicochemical characterisation of degrading polycaprolactone scaffolds. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2010, 95, 2269–2276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leroux, A.; Nguyen, T.N.; Rangel, A.; Cacciapuoti, I.; Duprez, D.; Castner, D.; Migonney, V. Long-term hydrolytic degradation study of polycaprolactone films and fibers grafted with poly(sodium styrene sulfonate): Mechanism study and cell response. Biointerphases 2020, 15, 61006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łysik, D.; Mystkowska, J.; Markiewicz, G.; Deptuła, P.; Bucki, R. The Influence of Mucin-Based Artificial Saliva on Properties of Polycaprolactone and Polylactide. Polymers 2019, 11, 1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Liu, T.; Huang, D.; Zhen, Z.; Lu, B.; Li, X.; Zheng, W.-Z.; Wang, G.-X.; Ji, J. Degradation performances of CL-modified PBSCL copolyesters in different environments. Eur. Polym. J. 2022, 174, 111322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Depraect, O.; Lebrero, R.; Rodríguez-Vega, S.; Bordel, S.; Santos-Beneit, F.; Martínez-Mendoza, L.; Börner, R.A.; Börner, T.; Muñoz, R. Biodegradation of bioplastics under aerobic and anaerobic aqueous conditions: Kinetics, carbon fate and particle size effect. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 344, 126265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, F.S.M.; Vélez, A.Q.; Urrutia, E.C.; Ramírez-Malule, H.; Hernández, J.H.M. Study of the Degradation of a TPS/PCL/Fique Biocomposite Material in Soil, Compost, and Water. Polymers 2023, 15, 3952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaseri, R.; Fadaie, M.; Mirzaei, E.; Samadian, H.; Ebrahiminezhad, A. Surface modification of polycaprolactone nanofibers through hydrolysis and aminolysis: A comparative study on structural characteristics, mechanical properties, and cellular performance. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 9434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellen, F.; Carbone, E.; Baatsen, P.; Jones, E.; Kabirian, F.; Heying, R. Improvement of Endothelial Cell-Polycaprolactone Interaction through Surface Modification via Aminolysis, Hydrolysis, and a Combined Approach. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2023, 2023, 5590725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nashchekina, Y.; Chabina, A.; Nashchekin, A.; Mikhailova, N. Different Conditions for the Modification of Polycaprolactone Films with L-Arginine. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timoncini, A.; Costantini, F.; Bernardi, E.; Martini, C.; Mugnai, F.; Mancuso, F.P.; Sassoni, E.; Ospitali, F.; Chiavari, C. Insight on bacteria communities in outdoor bronze and marble artefacts in a changing environment. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 850, 157804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappitelli, F.; Villa, F.; Sanmartín, P. Interactions of microorganisms and synthetic polymers in cultural heritage conservation. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2021, 163, 105282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branysova, T.; Demnerova, K.; Durovic, M.; Stiborova, H. Microbial biodeterioration of cultural heritage and identification of the active agents over the last two decades. J. Cult. Herit. 2022, 55, 245–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosallanezhad, P.; Nazockdast, H.; Ahmadi, Z.; Rostami, A. Fabrication and characterization of polycaprolactone/chitosan nanofibers containing antibacterial agents of curcumin and ZnO nanoparticles for use as wound dressing. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 1027351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossyvaki, D.; Barbetta, A.; Contardi, M.; Bustreo, M.; Dziza, K.; Lauciello, S.; Athanassiou, A.; Fragouli, D. Highly Porous Curcumin-Loaded Polymer Mats for Rapid Detection of Volatile Amines. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2022, 4, 4464–4475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Khatri, Z.; Oh, K.W.; Kim, I.-S.; Kim, S.H. Preparation and characterization of hybrid polycaprolactone/cellulose ultrafine fibers via electrospinning. Macromol. Res. 2014, 22, 562–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergamasco, S.; Fiaschini, N.; Hein, L.A.; Brecciaroli, M.; Vitali, R.; Romagnoli, M.; Rinaldi, A. Electrospun PCL Filtration Membranes Enhanced with an Electrosprayed Lignin Coating to Control Wettability and Anti-Bacterial Properties. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4360/16/5/674 (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Nivedita, S.; Joseph, S. Performance of polycaprolactone/TiO2 composite membrane for the effective treatment of dairy effluents. Water Sci. Technol. 2021, 83, 2477–2485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, G.; Yuan, X.; Li, P.; Yu, Y.; Yang, W.; Zhao, S. Reduction of Ultrafiltration Membrane Fouling by the Pretreatment Removal of Emerging Pollutants: A Review. Membranes 2023, 13, 77. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2077-0375/13/1/77 (accessed on 18 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Tsuji, H.; Suzuyoshi, K. Environmental degradation of biodegradable polyesters 1. Poly(ε-caprolactone), poly[(R)-3-hydroxybutyrate], and poly(L-lactide) films in controlled static seawater. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2002, 75, 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.X.; Huang, D.; Ji, J.H.; Völker, C.; Wurm, F.R. Seawater-Degradable Polymers—Fighting the Marine Plastic Pollution. Adv. Sci. 2021, 8, 2001121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyu, J.S.; Lee, J.-S.; Han, J. Development of a biodegradable polycaprolactone film incorporated with an antimicrobial agent via an extrusion process. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 20236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engler, L.G.; Farias, N.C.; Crespo, J.S.; Gately, N.M.; Major, I.; Pezzoli, R.; Devine, D.M. Designing Sustainable Polymer Blends: Tailoring Mechanical Properties and Degradation Behaviour in PHB/PLA/PCL Blends in a Seawater Environment. Polymers 2023, 15, 2874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heimowska, A.; Morawska, M.; Bocho-Janiszewska, A. Biodegradation of poly(ε-caprolactone) in natural water environments. Green Sci. 2017, 19, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).