Abstract

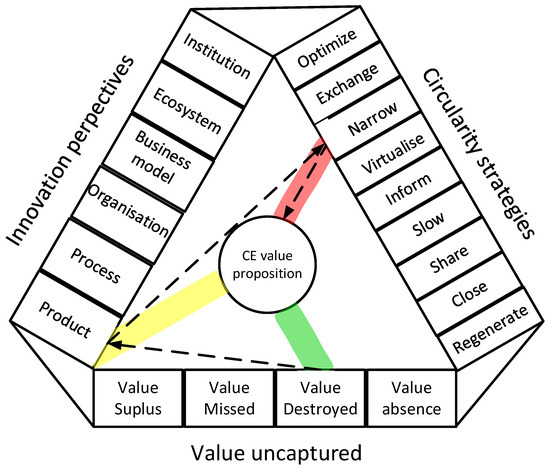

The transition to a circular economy (CE) presents a significant challenge for firms, especially in the initial stages, where cognitive barriers can hinder the identification of linear practices and the development of circular solutions. One key approach to supporting business model innovation has been the use of visualization tools. While several tools facilitate circular innovation, most remain primarily descriptive or evaluative and do not bridge the gap between diagnosing linear practices and designing circular value propositions. This paper addresses this gap by introducing a conceptual tool—the ‘Circular Value Navigator’—designed to support managers in the early stages of CE transformation. The tool aims to facilitate a systemic process for identifying problems rooted in the dominant linear economy and converting them into actionable CE opportunities. Therefore, it supports the development of circular value propositions. The proposed tool integrates three core dimensions: Value Uncaptured, Innovation Perspectives, and Circularity Strategies. By systematically exploring the interplay among these dimensions, the tool helps users identify and map circularity hotspots and pathways for improvement. This research contributes to the literature on cognitive tools in the circular economy field by offering a framework that enhances managers’ abilities in systemic thinking, problem reframing, and the strategic design of circular business models—ultimately aiming to accelerate the adoption of sustainable practices.

1. Introduction

The circular economy (CE) represents a transformative approach to sustainable development, aiming to decouple economic growth from resource consumption by promoting resource efficiency, waste minimization, and product life cycle extension. Unlike the traditional linear economy, which follows a “take-make-dispose” model, the circular economy emphasizes closed-loop systems in which materials are reused, remanufactured, and recycled [1]. This model not only mitigates environmental degradation but also fosters innovation, competitiveness, and strengthens long-term economic resilience [2]. As global environmental challenges intensify, integrating CE principles has become increasingly essential for achieving sustainable production and consumption patterns [3].

However, it is generally difficult for firms to fundamentally modify their business models (BMs) to reflect changes brought about by new technologies, evolving customer needs, and competitive dynamics [4]. This situation presents new challenges in designing BMs for scholars and practitioners. The circular economy becomes an issue of “now”, not the future, and is changing the ‘rules of the game’ in many industrial sectors in terms of what and how to adapt, and which BM to choose. The challenge of encompassing these new ways of operating is particularly vital for established firms that were built around a very different set of norms and structures. Research on adopting new market conditions indicates that cognitive barriers significantly influence this process. Managers may not fully comprehend the structural obstacles to change, and dominant logics within the firm can hinder stakeholders from embracing new ways of thinking [4,5]. Indeed, since adopting the circular economy concept involves experimentation, trial-and-error learning, and discovery [6,7], the pace at which new circular BMs are envisioned and the direction taken depend critically on decision-makers’ cognitive make-up, which shapes their awareness, understanding of key issues, and perception of the possibilities for refashioning the BM [4,8].

Scholars have found that organizations often struggle to adapt to new environments because of entrenched ways of thinking and acting. Concepts like dominant logic, cognitive lock-in, path dependency, and mental model rigidity explain why firms persist with outdated strategies, even when change is necessary for survival or growth [9,10,11,12]. Within this context, cognitive framing and problem-framing bias are central to understanding why human decisions often diverge from rational models—a phenomenon captured by the concept of bounded rationality. Empirical research demonstrates that the way information is presented and framed can systematically influence choices, leading to predictable biases even among experts and in high-stakes contexts [13,14,15,16].

Furthermore, cognitive inertia, functional fixedness, and exploitative learning bias are interrelated cognitive phenomena that can limit flexibility in problem-solving, creativity, and decision-making. These biases often lead individuals and organizations to rely on established patterns, prior knowledge, or habitual responses, sometimes at the expense of optimal or innovative solutions [17,18,19,20]. Modern challenges—such as sustainability and the circular economy—are increasingly recognized as “wicked problems” that cannot be solved through reductionist or myopic approaches. Research across disciplines highlights the limitations of focusing narrowly on isolated variables or short-term outcomes and advocates for systems thinking as a more effective paradigm for addressing complex, interconnected issues [21,22,23].

Significant efforts have been made to identify and categorize barriers that constrain the transition toward a CE across various levels, linking them to eight underlying mechanisms, such as cognitive lock-in and organizational inertia. These identified barriers form a system that reinforces itself, creating obstacles to necessary change [24].

These cognitive and organizational barriers pose significant challenges to CE transformation. This paper addresses this gap by focusing on how firms can identify linear problems and transform them into circular solutions. It seeks to connect CE strategies with problem identification from the perspective of sustainable BMs. Therefore, this paper scrutinizes the firm’s initial stage of this transformation, during which managers concentrate on identifying linear problems and generating potential solutions [25].

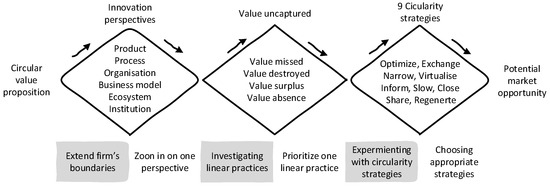

This communication introduces the Circular Value Navigator (CVN), a tool designed primarily to identify problems rooted in the dominant linear economy and transform them into CE opportunities. The authors present the early development of the CVN, which aims to provide a conceptual tool for guiding a systemic process of identifying circular value propositions. To achieve this goal, the research draws on CE business strategies as well as sources of market opportunities derived from the sustainable BM field. Furthermore, the tool seeks to develop a comprehensive understanding of the ways in which the CE strategies can enhance environmental impact across different Innovation Perspectives. Once the conceptual framework was completed, the CVN was tested under real conditions within the ORHI PLUS project (2024–2026), funded by the EU POCTEFA.

Hence, this study is guided by the following research question: During the early stages of transition toward a circular economy, how can a design-oriented and supportive tool assist managers in overcoming cognitive barriers, identifying linear practices, and transforming them into circular market opportunities?

Based on this goal, the paper and its introduced tool have multiple key objectives. First, the tool should be designed to challenge dominant linear logic and reframe thinking through the diagnosis of linear practices. Second, it seeks to address problem-framing deficiencies by revealing hidden or ill-defined linear issues and facilitating their systemic identification across multiple innovative perspectives. Third, the tool aims to overcome cognitive fixation and reduce reliance on habitual solutions by guiding users through the exploration of nine diverse circularity strategies. Fourth, it supports a shift from fragmented and reductionist thinking—where the focus is on isolated interventions—toward systemic visualization, linking multiple Innovation Perspectives and providing reference language for diverse stakeholders. Finally, the tool offers scaled-down, simplified representations that enhance cognitive accessibility, allowing users to experiment virtually with alternative configurations and pathways toward circularity.

This study particularly focuses on small- and medium-sized manufacturing and agri-food enterprises (SMEs), as these firms face significant material and energy dependencies [26] and must anticipate future legal requirements [27]. Nevertheless, many of the identified challenges—such as cognitive barriers and limited systemic thinking—are common across sectors. Both manufacturing and service-oriented firms encounter difficulties related to material provision, resource reutilization, and financial advantage [28]. The case study of the food production sector exemplifies these issues, thereby justifying our focus.

This paper seeks to advance the literature on cognitive tools in the circular economy by proposing a framework for circularity thinking, knowledge acquisition, and systemic evaluation during the early stages of business transition. The remainder of the paper is structured as follows: Section 2 covers the theoretical background of this study by presenting the concepts of circular BMs and field-developed tools. Section 3 details the development of the Circular Value Navigator tool. In Section 4, an illustrative case study is provided. Section 5 offers a discussion, and Section 6 concludes the paper.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Sustainable Business Model

Business models generally refer to the logic by which a firm conducts its business and describe how value is created, proposed, delivered, and captured [29,30]. The primary advantage of BMs is that they provide a holistic view of the firm [31]. Several perspectives on business models have been discussed in the research literature. The most examined definition of a BM refers to a framework that comprises key elements constituting the business, such as the well-known Business Model Canvas [32]. Alternative perspectives pertain to detecting typologies and taxonomies [33], the activity system perspective [34], and the cognitive view [35,36].

In a sustainable business model (SBM), sustainability concepts drive and shape decision-making by prioritizing the needs of key stakeholders—including society and the environment—thus transforming the dominant neoclassical model [37]. Environmental transformation refers to fundamental changes in the interactions between society and the environment, aiming for sustainability through systemic, structural, and often deliberate shifts in social, economic, and socio-ecological systems [38]. This can include shifts in values, institutions, production and consumption patterns, and governance structures [39]. The literature outlines different subcategories and archetypes of SBMs, such as product–service systems, base-of-the-pyramid, and circular business models [40].

The concept of Value Uncaptured emerged from research on sustainable business model innovation (SBMI) and refers to potential value that could be captured but has not yet been realized. It encompasses the following four categories: Value Destroyed, Value Missed, Value Surplus, and Value Absence [41,42]. The underlying idea is that SBMI can be driven by identifying untapped value within existing business models, which can then be transformed into opportunities for developing new models that deliver greater sustainable value [42]. In this context, Value Uncaptured represents the economic, environmental, and social losses inherent in the linear system.

Value Surplus (VS) refers to value that is created but not fully utilized, recognized, or monetized by the company or its stakeholders. It may represent excess capacity or a co-benefit that is not strategically leveraged. From the CE point of view, VS can be seen in products with remaining lifespans that are discarded. Their residual utility constitutes surplus value that is not captured. Over-specification of materials or designs—such as using higher-grade materials or excessive energy consumption—represents an unutilized surplus of resource investment. Value Absence (VA) denotes the lack of necessary value that is essential but currently unavailable. This concept encompasses elements or activities that are crucial for CE but have not yet been provided. It can be understood as unmet needs that could be addressed but remain unfulfilled. Introducing CE concepts highlights the absence of essential circular activities or enablers, such as repairing, recycling, remanufacturing, or reusing. One of the key circularity enablers is the reverse logistics system. Firms highlight its absence in their BMs and emphasize its importance in returning end-of-life products back into the economic cycle. Another absent enabler is the lack of performance tracking systems. Firms also emphasize the need for these systems to evaluate the actual condition of a product, and therefore oversee circularity activities (e.g., repair and remanufacturing).

Value Missed (VM) is value that exists and is needed but remains unexploited, resulting in its dissipation. This represents potential value that a company fails to capture due to its current business model, processes, or lack of foresight. It is an opportunity that goes unseized. VM does not have a negative impact but is regarded as waste with high potential; however, it diminishes the value that could otherwise be created. Major missed values can be identified in terms of their missed benefits or contribution to CE. For example, firms may overlook end-of-life potential by failing to consider products as future resources, thereby missing out on revenue from secondary materials, remanufacturing, or parts harvesting. Additionally, companies may neglect service-based offerings by focusing solely on product sales, missing opportunities for ongoing customer relationships, optimization of product use, and efficient recovery. Finally, firms may disregard by-products or “waste” streams as valuable inputs. Treating by-products as waste rather than as co-products for other processes is another missed value opportunity.

Finally, Value Destroyed (VD) refers to the value that is actively diminished or eliminated by a company’s activities or products. This can include environmental degradation, negative social impacts, or the premature obsolescence of products. Value Destroyed associated with CE can include the disposal of products in landfills, unsustainable resource extraction (e.g., impacts such as deforestation), planned obsolescence, and pollution and waste generation. Damage is not limited to technical aspects (material-related) but can also take systemic forms (for instance, difficulties in separating materials at the end-of life) and interactional forms (e.g., people distrusting second-hand products) [43].

Eco-innovation is recognized as the operational and technological engine of sustainability. Firms can innovate toward a circular economy through the following six interconnected Innovation Perspectives: product, process, organization, business model, ecosystem, and institution [22,44,45].

Product innovation is initially dominant and prioritized, while process innovation gains significance over time [46]. Product innovation encompasses changes in the product–service deliverable and embraces eco-design and design for sustainability [23]. Eco-design practices primarily focus on reducing environmental impact throughout the entire product life cycle, from raw material extraction to final disposal. These practices involve design strategies based on recyclability, reduction in raw material and energy consumption, improved life cycle impact, and sustainable packaging [47]. Process innovation involves the development and successful implementation of novel production techniques within the manufacturing sector. Changing a production process requires modifications to the value chain and value network [48]. Eco-efficiency has been a major focus for firms, such as identifying new ways to improve the efficiency of their production processes. This contrasts with product innovation, where value is realized and perceived through the firm’s commercial output [49].

Organization innovation involves new forms of management [50] or novel organizational methods in a firm’s business practices, workplace organization, and external relations. These changes reshape responsibilities and decision-making among employees, affecting the division of labor within and between firm activities [51]. Organizational eco-innovation management activities should lead to a reduction in environmental impact. Innovative organizational arrangements are practices within an organization that facilitate eco-innovation, such as enabling structures, communication, training and development, leadership, and recognition [46]. Business model innovation refers to the reconfiguration of business elements through which firms create greater value or reduce costs, thereby either increasing revenue from existing markets or attracting new customers [52]. SBMI can refer to changes in the BM that innovatively reduce environmental and social impacts while creating a competitive advantage for stakeholders [36]. Such SBMI includes product–service systems (PSSs) [53].

Ecosystem innovation extends beyond the business model level by giving equal importance to the BMs of other relevant actors. It examines how multiple business models can be integrated to achieve a collective outcome [54]. This approach involves new solutions at a more systemic level, aiming to build an eco-efficient society characterized by novel ways of organizing production and consumption, as well as new functional interactions between organizations [55]. Institutional innovation encompasses the activities of both public and private organizations in driving and managing the entire process of invention, innovation, and diffusion [56]. New regulations and strategies at the institutional level can gradually advance the implementation of circularity. Public institutions may introduce new standards for environmental practices, provide waivers and subsidies, set targets, and resolve conflicts [57]. Private institutions may undergo changes related to business strategy, reconfiguration of the BM, investment in network building, and collaboration with government agencies [58].

Building on the sustainable business model perspective, the next subsection narrows the focus to circular business models, which operationalize sustainability principles through resource loops and regenerative strategies.

2.2. Circular Business Model

Circular BM incorporates the business model concept into the circular economy, which can be understood as a systemic approach to managing physical flows. It prioritizes reverse flows and seeks to address the challenges posed by the unsustainable global linear economy by promoting cyclical material use, renewable energy sources, and cascading processes [3]. Current businesses and practitioners articulate CE with maximization of material circularity, prioritizing more efficient inner cycles in terms of both material and energy. This includes practices such as product reuse, repair, remanufacturing, and refurbishment, rather than conventional recycling, which often results in low-grade raw materials. The duration for which the value of resources is retained within the inner cycles should be optimized. Initial steps should focus on recovering materials for reuse, refurbishment, and repair. Subsequently, attention should shift to remanufacturing, with recycling considered as a final option for material utilization [59]. According to this approach, energy recovery through combustion should be the second-to-last option, with landfill disposal being the least favorable choice. Through this, CE ensures that the value chain and life cycle of products maintain their maximum value and quality for an extended period while also optimizing energy efficiency [60].

Although the CE has great potential to reduce the environmental footprint, it also has its limitations. Six challenges related to environmental sustainability have been identified for the CE concept [60]. These include, for example, constraints associated with the rebound effect, as well as issues arising from path dependency and lock-in [61]. Furthermore, CE’s contribution to addressing critical global issues—such as the tensions between biophysical limits and economic progress and growth—has been criticized [62]. There is no consensus among scholars regarding the definition of circular business models, and there is a range of interpretations surrounding the concept [63]. However, circular business models generally aim to conserve and enhance natural capital [26], integrating CE principles [64], and translating them into actionable strategies [65].

The classification of CE strategies for business transformation is diverse and can be categorized into various approaches [26]. The concepts of “slowing,” “narrowing,” and “closing” are based on mechanisms that regulate the flow of resources within a system [65]. The “closing” strategy involves creating closed-loop systems in which goods and materials are recycled. The “slowing” strategy aims to reduce the speed of resource flow from production to recycling, achieved through practices such as repair, reuse, reconditioning, repurposing, designing products for long lifespans, and upgrading. The “narrowing” strategy focuses on increasing material efficiency by reducing the amount of resources used per product.

The literature on circularity strategies shows that the ReSOLVE framework serves as a guide for companies pursuing circular business practices, enabling them to rethink and redesign their operations to be more sustainable and resource-efficient [66,67]. This framework outlines six key business actions for companies to implement CE principles. The components of the ReSOLVE framework are Regenerate, Share, Optimise, Loop, Virtualize, and Exchange. The Regenerate strategy refers to shifting towards renewable energy and materials, reclaiming, retaining, and restoring the health of ecosystems, and returning used biological resources to the biosphere [56]. Share includes asset sharing, maximizing resource utilization, reusing products, extending their lifespan, and designing for durability, reparability, and upgradability. The product–service system can leverage resource efficiency through CE [68]. Optimize ensures the efficient use of products and processes, avoids waste in production and supply chains, and leverages big data, automation, remote sensing, and steering. Loop involves creating closed material loops where products, components, and materials are continuously reused, repaired, or recycled rather than disposed of.

Virtualize is about substituting physical materials with digital tools and technologies to reduce material consumption and waste. Exchange refers to replacing old materials with advanced non-renewable materials, applying new technologies (e.g., deep learning, big data, and digitalization), and choosing new products and services (e.g., multi-modal transport) [69]. Ref. [54] introduced a CE ideation tool based on the following five broad strategies: slow, close, regenerate, narrow, and inform. The latter is identified as a supportive strategy with an indirect effect, emphasizing the role of information technologies in enabling CE implementation. The existing literature identifies the following four generic Circular Strategies: cycling, extending, intensifying, and dematerializing [63]. Cycling entails implementing various end-of-use strategies. The objective of extending is to keep the product in use for as long as possible, primarily facilitated by effective design and operational practices. Intensifying involves implementing new value propositions around sharing models, enabled by capacity management, digital capabilities, and customer relationship management. Dematerializing decreases the use of physical resources by enhancing the value created through intangible solutions, such as services and software. Common CE strategies include the 9R list, a set of well-defined CE strategies that rank different approaches based on their effectiveness in achieving circularity. The R-list consists of recover, recycle, repurpose, remanufacture, refurbish, repair, reuse, reduce, rethink, and refuse [59].

While circular business models provide the conceptual foundation for closing resource loops, their practical realization relies on dedicated tools and frameworks that help firms design, assess, and implement Circular Strategies—these are discussed in the following subsection.

2.3. Circular Economy Tools

The academic literature reveals a wide variety of approaches to the use of CE tools. These tools, often informed by specific CE strategies, are designed to address both external and internal barriers that firms encounter when implementing circular practices [70].

Assessment tools constitute a significant portion of the literature. Key Performance Indicators (KPIs), Life Cycle Assessment (LCA), Material Flow Analysis (MFA), and Circularity Indicators are widely used to measure and monitor circularity at a product, firm, city, and sector levels. These tools help organizations track progress, identify opportunities, and guide decision-making for circularity improvement [70,71,72].

Several diagnostic and self-assessment tools have been developed for industrial firms. One example is a comprehensive questionnaire designed to support compliance with European legislative requirements by providing 165 analytical questions that facilitate the integration of CE strategies and solutions. Focusing on end-of-life scenarios, Ref. [73] proposed a decision-making method that helps firms reconsider post-use product phases by exploring alternative circular pathways at strategic levels. This tool emphasizes that CE implementation requires coordinated changes across multiple dimensions. Similarly, MATChE—a self-assessment tool for manufacturing firms—was developed to evaluate CE readiness across eight organizational dimensions, including product innovation, support, and maintenance. It enables both internal and external benchmarking and assists firms in identifying their strengths and gaps in CE implementation [74].

Business model innovation and implementation tools include visualization tools, process frameworks, and conceptual models that assist firms in designing, assessing, and implementing CE strategies. Examples include a visualization tool structured as a matrix to analyze business model elements across different life cycle stages [75]. Ref. [76] developed a design toolkit for circular designers to explore ideas that make circular solutions more desirable and user-preferred. The CE Strategies Database, supported by the CE Implementation Database, consolidates diverse methods of CE implementation described in the literature [70]. However, while it provides valuable definitions of CE strategies, it offers limited insight into their practical application and lacks diversity in perspectives and tool design. In the construction sector, Ref. [77] developed a collaboration tool that enhances supply chain integration through a structured five-phase framework. This tool emphasizes establishing a shared vision, clearly defined collaborative roles, and relationships based on trust and mutual benefit.

A circular business model (CBM) visualization tool that bridges the gap between conceptual CE strategies and their practical implementation was developed by [78]. This tool quantifies resource flows and adopts a systemic perspective that extends beyond product-level considerations to include processes, firms, and supply chains. A four-phase guide to assist stakeholders in identifying new market opportunities through systems thinking was introduced by [44]. This guide includes understanding the current situation, aligning values with CE principles, mapping captured and uncaptured values to support innovation, and analyzing opportunities in terms of resource flows. Similarly, the Circularity Deck is designed to help firms analyze, ideate, and develop circular innovation ecosystems. It comprises five major Circular Strategies, each implemented through a set of actionable principles applicable at the product, business model, or ecosystem-level [79].

Research on industrial symbiosis tools demonstrates heterogeneous approaches, with a shared emphasis on documenting successful cases and identifying potential synergies among firms [80]. Other branches of research focus on digital technologies such as IoT, AI, big data, and digital platforms that enable data-driven decision-making [81,82]; sector-specific tools that adapt general methods to industry-specific needs, such as construction, packaging, and urban systems; and governance tools that support systemic change, including adaptive governance models, financial incentives, and regulatory frameworks [83,84].

Despite the diversity of circular economy tools available, many remain descriptive or evaluative and fail to address the cognitive and systemic challenges of transformation. The next subsection therefore examines their limitations and outlines the need for a cognitive approach to support early-stage circular innovation.

2.4. Limitations of Existing Circular Economy Tools: Toward a Cognitive Approach

The transition to a CE is frequently hindered by cognitive barriers, necessitating tools that offer structural and conceptual support for identifying linear practices and developing new circular value propositions. The existing literature presents several specialized tools that, while valuable, exhibit nuanced limitations regarding scope, systemic approach, or structured validation. The Value Mapping Tool introduced a systemic, stakeholder-centric approach by integrating four representations of value (captured, destroyed, missed, and opportunity) [41]. However, although the tool effectively supports the diagnosis of Value Missed and Value Destroyed, empirical use suggests a conceptual limitation, as it lacks a dedicated cognitive framework or structured methodology to guide users in identifying new value propositions. More recent approaches, such as the Circularity Deck [79], address systemic needs by integrating ecosystem innovation alongside product and business model principles, employing a haptic card-deck format for cognitive support. Nonetheless, this tool remains qualitative, carries the risk of information overload, and explicitly excludes social and institutional dimensions, thereby restricting its holistic capacity to support CE transformation.

Other frameworks target specific contexts or stages. For example, the Circular Strategies Scanner [85] provides a highly systematic, process-aligned framework for manufacturing companies, excelling as a boundary object for vision alignment. However, the extensive range of its strategies and the requirement for explicit descriptors to indicate specific application types (e.g., pre-user vs. post-user recycling) introduce a degree of visual and conceptual complexity that may present a barrier to rapid cognitive adoption. The Circular Product Design Maturity Matrix (CPDM2) focuses on assessing the maturity of the new product development process, offering structured diagnosis and gradual guidance [86]. Its utility, however, is derived from a complex scoring calculation and subjective self-assessment, positioning it as an evaluative rather than an ideation-focused tool. For implementation guidance, the methodology proposed by [87] offers a highly systematic, multi-tool screening approach for resource-constrained SMEs, though the initial exploration of the vast solution space presents a significant cognitive challenge. Conversely, the visualization tool by [78] prioritizes the quantification of resource flows using Sankey-like diagrams, providing robust decision support but requiring significant initial data investment—a notable barrier for many resource-limited firms. Finally, the CBM Mapping Tool systematically visualizes the necessary adjustments in business model elements across multiple product cycles [75] but is primarily designed for conceptual architecture rather than diagnosing operational linear practices.

In light of these specialized approaches, which are often oriented toward (1) qualitative exploration [41,79], (2) readiness assessment [74,86], or (3) quantitative flow analysis [78], the proposed Circular Value Navigator aims to provide a focused, actionable transformation tool. This Navigator is developed to address the recognized need for tools that seamlessly bridge the gap between identifying specific linear operational practices (the “problem”) and developing circular value propositions (the “solution”) within a single, integrated framework. While the MATChE tool [74] effectively assesses readiness across organizational dimensions, the CVN is positioned to support the essential cognitive transition from diagnosing linear practices to generating circular value. Therefore, it constructively complements the existing body of work by offering a targeted, early-stage intervention for operational transformation.

Recognizing these gaps motivates the development of a new integrative and cognitively oriented tool. The following section introduces the Circular Value Navigator, which directly addresses these shortcomings by linking the diagnosis of linear practices with the generation of circular value propositions.

4. Tool Use in a Workshop

The usability and utility of the circularity tool were evaluated through a workshop. Two participants from the Commercial Chamber of Bayonne, representing the studied firm—a food production company referred to as Alfa in this study—took part in the test. This version of the tool was deployed in a simple printed paper format.

4.1. The Context

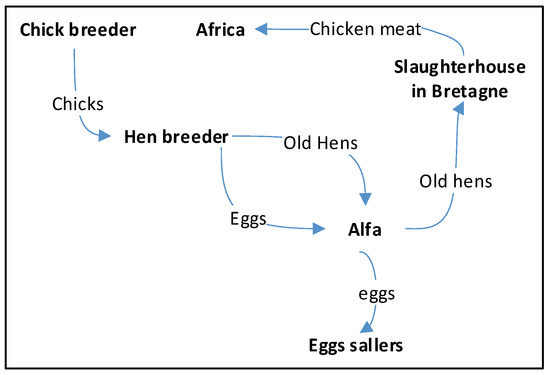

The study focuses on a specific issue within the egg production value chain in the Basque region of France, where a linear business model generates economic and environmental inefficiencies. Alfa, our focal company, purchases eggs, packages them, and distributes them. To visualize the tool’s dynamic use, triangles and circles are used to represent Value Uncaptured and Circular Strategies, respectively. Different colors are also employed to illustrate the relationships between Circular Strategies and Values Uncaptured.

4.1.1. Value Uncaptured Identification

The primary challenge identified in this case is the unsustainable management of hens at the end of their most productive egg-laying period (6 to 18 months). In the current linear model, hens older than 18 months are considered by-products and are eliminated from farms. They are transported approximately 800 km from the Basque region to a slaughterhouse in the Bretagne region before being shipped as chicken meat to Africa by boat. All the involved stakeholders, their relationships, and their activities are illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Case study’s main stakeholders and their relations.

The economic viability of this process has become unsustainable due to a significant decrease in the market price of these hens (from 18 cents to 2 cents per hen) and rising transportation costs. This economic challenge is further compounded by the considerable environmental impact of long-distance transport, which generates high CO2 emissions.

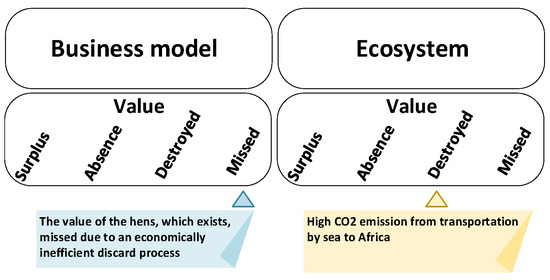

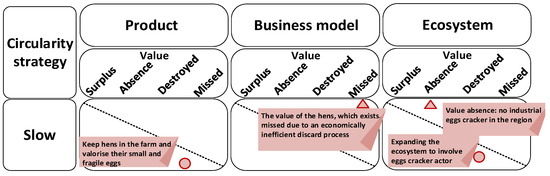

Within the Circular Value Navigator framework, participants identified two linear problems. At the ecosystem level, the transportation to Africa emits a significant amount of CO2 (value destroyed). At the business model level, the value of the hens is being lost due to an economically inefficient discard process (value missed). This issue highlights a substantial Value Uncaptured that can be transformed, as seen in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Visualization of the identified Values Uncaptured (triangles) in the business model and ecosystem perspectives.

4.1.2. Circular Economy Strategies and Solutions

To address these values uncaptured, participants applied the framework to identify appropriate CE strategies. The initial focus was on the “Narrowing” and “Closing the Loop” strategies. The goal was to reduce the environmental impact of transportation by closing the loop locally, thereby avoiding thousands of kilometers of travel to Africa. The framework was used to develop three distinct value propositions, each demonstrating how a single Value Uncaptured can be transformed through diverse, multi-level solutions.

- I.

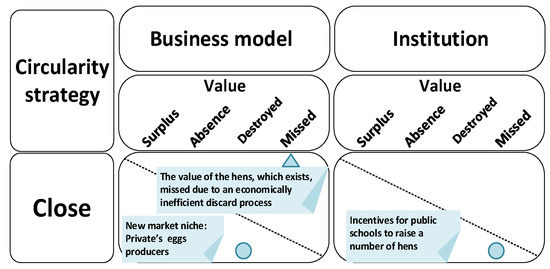

- Value Proposition 1: Direct-to-consumer niche market

This value proposition is based on the “Narrowing” and “Closing the Loop” strategies by selling hen by-products directly to new clients, Figure 6. These clients include customers who wish to produce their own eggs at home or within their organizations (e.g., public institutions). This creates a short local loop, significantly reducing the carbon footprint associated with long-distance transportation, Figure 7. Implementing this solution requires modifications in two Innovation Perspectives. Firstly, in the business model, a new niche market is targeted. While economically it is the most advantageous option per hen (EUR 4), this market is limited, comprising only 5% to 10% of the hen population. Secondly, regarding institutional targets, the solution’s full potential depends on incentives at the institutional level. For example, local authorities could encourage schools to raise a certain number of hens, thereby reducing biological waste and promoting self-consumption of eggs.

Figure 6.

Example of mapping the “Close” strategy across the business model and institution perspectives, highlighting the transformation of a missed value (inefficient discard of hens) into circular opportunities through local market development and institutional incentives.

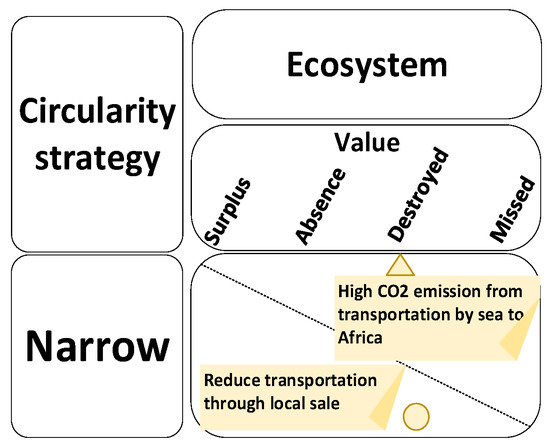

Figure 7.

Illustration of the CVN mapping for the “Narrow” circularity strategy and a value destroyed within the ecosystem innovation perspective.

- II.

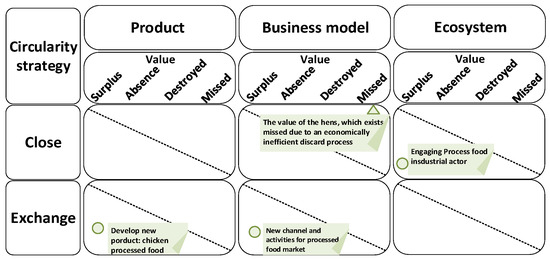

- Value Proposition 2: Local food transformation

The participants examined the “Exchange” strategy and considered alternative technologies to be deployed. A new value proposition is suggested, involving new additional activity in the business model. This activity consists of transforming hens into processed food products for local consumption. This can be achieved by expanding the ecosystem to include the processed food industry. Since the hens are smaller than standard market chickens, the focus is on creating customized food products for public organizations and industries rather than the mass market. Therefore, the final consumers are public schools, restaurants, caterers, hospitals, and similar institutions. To maintain a low environmental impact, the “Closing” strategy is also considered. These two strategies require modifications across three perspectives, as illustrated in Figure 8. Firstly, in the product, the hens are re-envisioned as a new product for the processed food industry. Secondly, in the business model, this requires developing new channels and activities for the processed food market. Finally, in the ecosystem, the network of actors must expand to include processed food industries in the region, with discussions centered on product traceability and environmental benefits.

Figure 8.

Example of mapping “Close” and “Exchange” strategies across product, business model, and ecosystem perspectives, demonstrating how a missed value from discarded hens can be converted into circular opportunities through local processing and new business activities.

- III.

- Value Proposition 3: Extending the life cycle

This value proposition is built upon the “Slowing” strategy, which involves keeping hens for a longer period despite their lower productivity and the production of smaller, more fragile eggs. These “low-standard” eggs are then sold to a specific niche market of environmentally conscious customers or agri-food processors who produce egg products, such as egg crackers. This strategy requires adjustments from two perspectives, as illustrated in Figure 9. On the one hand, adjustment in the product, involving the sale of small and fragile eggs. On the other hand, an adjustment to the ecosystem, which requires expanding its boundaries to include the egg cracker industry. However, to implement this new value proposition, a new Value Uncaptured—a Value Absence—exists at the ecosystem level. Currently, there is no industrial egg cracker facility in the region. Establishing an industrial egg cracker facility in the region to utilize low-standard eggs as raw material could close the loop and generate both environmental and economic benefits. This example highlights how the framework can identify gaps in the ecosystem that, if addressed, could unlock significant circular value at the product level.

Figure 9.

Example of the identification of Missed and Absence Values, and the use of “slow” strategy to generate a new value proposition.

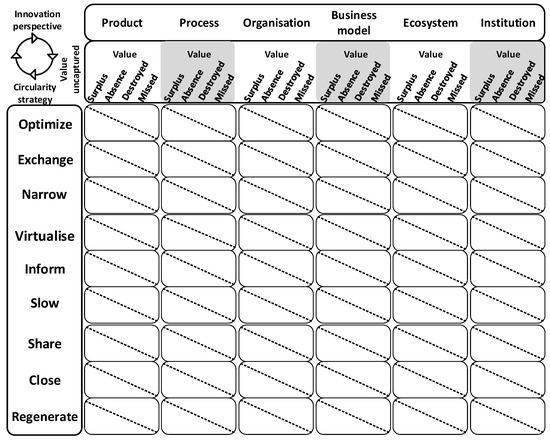

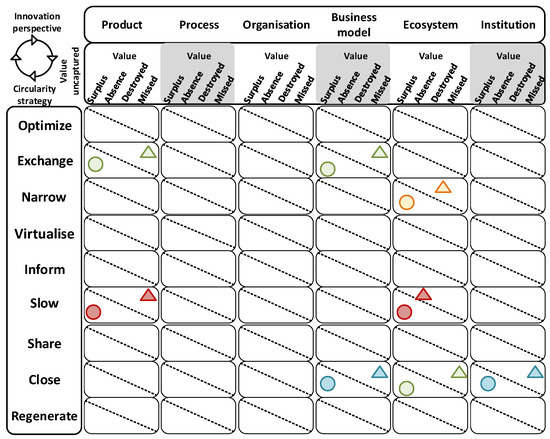

The results of this workshop are shown in Figure 10. Two initial and one subsequent Value Uncaptured have been identified. Four Circularity Strategies were explored and employed to formulate new circular value propositions. Their implementation requires modifications in the product, business model, ecosystem, and institution perspectives. The mapping of the final results provides an overall view, highlighting both addressed and neglected areas. For example, the ecosystem perspective is significantly impacted, while the process and organization perspectives are totally intact. Similarly, this global mapping indicates that no Value Surplus has been identified and that four strategies have been clearly overlooked.

Figure 10.

The global results of the case study presented on the grid. Triangles represent Values Uncaptured, circles represent Circular Strategies, and the colors show the link between Circular Strategies and Values Uncaptured.

5. Discussion

The principle of circular BMs is acknowledged as a key enabler for organizations transitioning to circular practices. However, developing business models that align with circular principles and leveraging the associated environmental and economic benefits presents new cognitive challenges for decision-makers.

The CVN tool proposed in this article aids in critically evaluating and innovatively designing circular value propositions that pave the development of more CE business models. The tool is composed of three phases intended to help firms understand and assess the current non-circular aspects of their value propositions, as well as to establish new ones grounded in Circular Strategies. Its ultimate goal is to guide the exploration of new market opportunities. The tool introduces users to the concept of Value Uncaptured and CE strategies. It supports managers in overcoming complex circular challenges, encourages thinking beyond the dominant linear logic, and enables the effective mental representation and communication of circular economy knowledge.

The pilot case study of the food production company demonstrated the framework’s ability to systematically diagnose a specific linear problem and generate a diverse portfolio of multi-level circular solutions. For example, Figure 8 and Figure 9 illustrate two distinct transformation pathways. While Figure 8 emphasizes technological innovation and ecosystem expansion (“exchange” and “close” strategies), Figure 9 focuses on life cycle management and product longevity (“slowing” strategy). This comparison demonstrates the flexibility of the CVN in exploring and contrasting diverse circular pathways. By identifying Values Uncaptured, “missed, destroy, and absence” and applying the “narrowing”, “closing”, “exchanging”, and “slowing” strategies, the analysis moved beyond a simple cost–benefit exercise. It revealed opportunities for new BMs and the need for institutional support and local partnerships. A clear roadmap for a company’s transition from a linear to circular business model is demonstrated through the examination of the case study.

The overall mapping and presentation of the case results on the value navigator grid visually illustrate how many strategies have been examined, the relationships between the Circular Strategies and Values Uncaptured, and the Innovation Perspectives outlined. The map offers several benefits. First, it provides a global overview by presenting a single, comprehensive view of the entire analysis, including its key focus areas. Second, the empty cells on the grid represent areas that have not yet been analyzed or addressed. These “white spaces” raise questions about their potential as opportunities for future CE initiatives. Third, the map reveals connections and dependencies, showing how solutions at one level might address problems at another. This visual connection underscores the systemic nature of CE solutions and the need for multi-level interventions, as solving a problem in one area may require action in a completely different area. Finally, the mapping facilitates communication and collaboration among stakeholders, as the visual representation is more intuitive than a text-based report. CVN tends to act as a powerful strategic tool for planning, prioritization, and communicating the company’s circular economy journey.

The development and the primary experimentation of the CVN tool provide several managerial insights. First, managers should recognize that fostering CE innovation requires moving beyond incremental improvements and adopting a systemic, interconnected approach that expands beyond the value chain and embraces the Innovation Perspectives, including ecosystem and institutional changes [101]. Traditional linear frameworks (e.g., Porter’s value chain) are insufficient; managers must adopt circular, networked models that emphasize closed-loop processes and value recapture. Second, the CVN tool can play the role of a transformational roadmap, thus supporting top management commitment [102,103]. Third, as managers pilot, evaluate, and scale CE initiatives that recapture ongoing environmental and economic value losses [104], the CVN tool can be used as a testing laboratory and a space for trial-and-error experimentation. Finally, effective CE transformation depends on collaboration with suppliers, customers, and other stakeholders to co-create value and manage reverse logistics. The CVN can create a reference language among different actors to ensure mutual understanding and serve as a virtualization platform to capture and share the global image of transformation [8].

Our framework aligns with international research emphasizing the need for integrative CE tools that combine cognitive and systemic dimensions [25]. For example, Ref. [79] highlights the importance of visual ideation in circular ecosystem design, while [66] stresses the significance of extending the framework of the BM Canvas to stimulate and foster the implementation of the circular economy. Similarly, Ref. [105] address the need for a broader perspective by considering circular “building blocks” alongside BM elements. Additionally, Ref. [74] draws attention to self-assessment tools for evaluating organizational readiness for CE transition. The CVN contributes to this discourse by explicitly linking these perspectives within a single, structured process.

This work highlights several research contributions. First, it aligns with and advances circular BM theory by reconceptualizing its value proposition [66]. While the traditional view of the value proposition encompasses customer value, firm value, and environmental benefits, this article emphasizes the importance of negative value impacts—the Value Uncaptured—as an integral part of the value proposition and as a catalyst for circular value creation. The tool’s structured approach, which includes key elements—Innovation Perspectives, VU components, and Circular Strategies and their relationships—provides a new methodological perspective for circular BM design. This research advances innovation within the circular economy by synthesizing six Innovation Perspectives and nine Circular Strategies. This integration offers a new analytical framework for examining the interactions between various levels of innovation in circular transitions. Additionally, the proposed tool serves both as a structural framework and as an experimental platform for assessing the implementation of specific strategies (e.g., regenerating) across multiple Innovation Perspectives (e.g., process and ecosystem) or the combination of multiple strategies (e.g., exchange and closing) to leverage particular Value Uncaptured.

The tool has several strategic implications for businesses seeking to transit towards CE models. First, it provides actionable and systematic guidance that enables the analysis of the status quo and the exploration of new opportunities. By integrating previously values captured into a circularity mindset, the tool helps businesses identify areas where value is being lost and demonstrates how CE strategies can recover them. This focus can lead to cost savings and improved resource efficiency. Through a set of nine distinct strategies, the tool allows companies to tailor their approach based on their business model and sustainability goals. Additionally, the tool bridges different departments within a company by involving product design, business modeling, and ecosystem management, thereby promoting cross-functional collaboration for circular innovation. Its visual structure facilitates collaborative workshops, cross-departmental dialog, and the rapid identification of CE opportunities. For policymakers, the tool supports training and capacity-building initiatives by making CE principles more accessible.

On the cognitive level, the CVN functions as a cognitive scaffolding mechanism that helps managers overcome several well-documented barriers to circular innovation. Specifically, it mitigates dominant logic and cognitive lock-in by reframing linear assumptions through the analysis of Value Uncaptured. It also addresses problem-framing biases and bounded rationality by providing a structured diagnostic grid that makes linear inefficiencies explicit across multiple Innovation Perspectives. Furthermore, by fostering the exploration of diverse Circularity Strategies, the tool reduces cognitive inertia and stimulates divergent, system-oriented thinking. Finally, the shared visual framework counteracts cognitive fragmentation among organizational actors, enhancing cross-functional sensemaking and collective reflection.

The proposed tool contributes to several United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), notably SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure), SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production), and SDG 13 (Climate Action). By facilitating the identification of circular opportunities, it helps firms reduce material waste, promote sustainable industrial practices, and support low-carbon innovation.

6. Conclusions

In summary, organizational inertia, cognitive lock-in, fragmented thinking, and poor problem-framing constrain the integration of circular principles within firms. Although the development of systemic tools is widely acknowledged as essential for advancing CE practices, many organizations still struggle to acquire the foundational knowledge and familiarity necessary for their effective application. Current CE tools primarily focus on assessment and measurement, often overlooking the cognitive and organizational aspects of problem framing and solution development.

Addressing these shortcomings requires more than technical improvements; it calls for a cultural and managerial transformation that enables organizations to think in systems, embrace long-term perspectives, and cultivate collaborative learning environments where experimentation and adaptive change are actively encouraged.

This communication introduces the CVN, a tool designed to identify challenges within the linear economy and transform them into sustainable market opportunities. Our guiding tool assists managers in overcoming cognitive barriers by identifying linear practices and converting them into market opportunities, as it stimulates the practitioners to think within the entire system before proposing any solution towards CE implementation. Its visualization feature enables the mapping of linear practices and their relationships to a firm’s various functions. It encourages thinking beyond the boundaries of the firm’s BM to incorporate new stakeholders into the decision-making process. Furthermore, the tool and its structured framework facilitate the use of a reference language among diverse stakeholders.

Advancing business transformation involves multi-day workshops during which the company critically examines the entire value proposition. This process is co-created with key stakeholders, including suppliers, clients, and representatives from various functions. The diversity of user profiles fosters mutual learning and facilitates the identification of untapped collective and collaborative value propositions.

The actionable guidance for deploying the tool involves the following stages. First, create a cross-functional project team that includes members from design, operations, marketing, sales, and sustainability. Second, conduct a diagnostic session to identify values uncaptured using the tool’s framework. Third, extend the analysis to explore Circular Strategies. Fourth, model the different Values Uncaptured and employed strategies on the tool’s grid. Fifth, evaluate the final grid map by comparing occupied areas with untouched areas. Sixth, prioritize feasible solutions and integrate them into business processes. Finally, monitor progress and adjust based on performance indicators.

Although the concept is potentially applicable to all types of organizations, it has only been tested on small- and medium-sized businesses. Our case study demonstrates the tool’s effectiveness in facilitating critical thinking, questioning, and detecting non-circular practices, as well as experimenting with nine Circular Strategies to identify new and sustainable market opportunities. The systemic Innovation Perspective enables practitioners to explore new areas for applying CE principles.

Further studies are needed to enrich the findings presented in this paper and address its limitations. This study has limited empirical validation, relying on a single case study and qualitative data. Future research should expand testing across various sectors and regions, quantify the tool’s impact on resource consumption, and develop a digital version that automates mapping and data collection. For example, surveys could be conducted among managers to measure comprehension levels of Circular Strategies, the utility of the Values Uncaptured, and the quantity and quality of identified opportunities before and after using the tool. Additionally, firm-level performance metrics—such as material circulation speed, the percentage of recyclable materials, and the quantity of product parts reused—could be used to quantify the impact of tool adoption. Additionally, comparative studies could investigate how cultural factors, company size, and regulatory contexts influence tool adoption. Engaging more experts could help assess the relationships and relative importance between CE strategies and Innovation Perspectives—for example, whether specific strategies are more applicable to particular perspective, e.g., ecosystem. The revision and validation of CE strategies and Innovation Perspectives from a firm’s point of view should be addressed in future research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.H., I.L. and R.A.; Methodology, M.H., I.L. and R.A.; Validation, I.L. and R.A.; Investigation, M.H.; Writing—original draft, M.H.; Writing—review & editing, M.H. and R.A.; Visualization, M.H.; Supervision, I.L.; Project administration, I.L.; Funding acquisition, I.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF), Interreg POCTEFA 2021–2027 grant number (EFA009/01) And The APC was funded by European Regional Development Fund (ERDF), Interreg POCTEFA 2021–2027.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

This research was carried out within the framework of the ORHI+ project (EFA009/01), co-financed by the European Union through the Interreg VI-A Spain-France-Andorra Program (POCTEFA 2021–2027). ORHI+ promotes the deployment of circular economy technologies and business models to enhance the sustainability and circularity of economic activities in the cross-border POCTEFA region. The project involves collaboration among companies, research centers, and public authorities, with ESTIA contributing to the development of eco-innovation tools and bio-based composite product demonstrators.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Romain Allais was employed by the company Association Pour l’Environnement et la Sécurité en Aquitaine (APESA). The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CE | Circular economy |

| BM | Business model |

| CBM | Circular business model |

| VS | Value surplus |

| VD | Value destroyed |

| VM | Value missed |

| VB | Value absence |

| VU | Value uncaptured |

| SBM | Sustainable business model |

| SBMI | Sustainable business model innovation |

| CVN | Circular Value Navigator |

References

- Geissdoerfer, M.; Savaget, P.; Bocken, N.M.P.; Hultink, E.J. The Circular Economy—A New Sustainability Paradigm? J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 143, 757–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacArthur, E. Towards the Circular Economy. J. Ind. Ecol. 2013, 2, 23–44. [Google Scholar]

- Kirchherr, J.; Reike, D.; Hekkert, M. Conceptualizing the Circular Economy: An Analysis of 114 Definitions. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 127, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesbrough, H. Business Model Innovation: Opportunities and Barriers. Long Range Plan. 2010, 43, 354–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesbrough, H.; Rosenbloom, R.S. The Role of the Business Model in Capturing Value from Innovation: Evidence from Xerox Corporation’s Technology Spin-off Companies. Ind. Corp. Change 2002, 11, 529–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankenberger, K.; Weiblen, T.; Csik, M.; Gassmann, O. The 4I-Framework of Business Model Innovation: A Structured View on Process Phases and Challenges. Int. J. Prod. Dev. 2013, 18, 249–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, R.G. Business Models: A Discovery Driven Approach. Long Range Plan. 2010, 43, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosna, M.; Trevinyo-Rodríguez, R.N.; Velamuri, S.R. Business Model Innovation through Trial-and-Error Learning: The Naturhouse Case. Long Range Plan. 2010, 43, 383–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohnsack, R.; Kurtz, H.; Hanelt, A. Re-Examining Path Dependence in the Digital Age: The Evolution of Connected Car Business Models. Res. Policy 2021, 50, 104328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obloj, T.; Obloj, K.; Pratt, M.G. Dominant Logic and Entrepreneurial Firms‘ Performance in a Transition Economy. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2010, 34, 151–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreyögg, G.; Sydow, J. Organizational Path Dependence: A Process View. Organ. Stud. 2011, 32, 321–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acciarini, C.; Brunetta, F.; Boccardelli, P. Cognitive Biases and Decision-Making Strategies in Times of Change: A Systematic Literature Review. Manag. Decis. 2021, 59, 638–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusnaini, Y.; Hakiki, A.; Wahyudi, T. Cognitive Mapping and Framing Bias on Decision Making. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. Res. 2023, 8, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Martino, B.; Kumaran, D.; Seymour, B.; Dolan, R.J. Frames, Biases, and Rational Decision-Making in the Human Brain. Science 2006, 313, 684–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunegan, K.J. Framing, Cognitive Modes, and Image Theory: Toward an Understanding of a Glass Half Full. J. Appl. Psychol. 1993, 78, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffaelli, R.; Glynn, M.A.; Tushman, M. Frame Flexibility: The Role of Cognitive and Emotional Framing in Innovation Adoption by Incumbent Firms. Strateg. Manag. J. 2019, 40, 1013–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alós-Ferrer, C.; Hügelschäfer, S.; Li, J. Inertia and Decision Making. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.A. Opportunity Recognition as Pattern Recognition: How Entrepreneurs “Connect the Dots” to Identify New Business Opportunities. AMP 2006, 20, 104–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripsas, M.; Gavetti, G. Capabilities, Cognition, and Inertia: Evidence from Digital Imaging. In The SMS Blackwell Handbook of Organizational Capabilities; Helfat, C.E., Ed.; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2017; pp. 393–412. ISBN 978-1-4051-0304-6. [Google Scholar]

- Gavetti, G. PERSPECTIVE—Toward a Behavioral Theory of Strategy. Organ. Sci. 2012, 23, 267–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewatsch, S.; Kennedy, S.; Bansal, P. Tackling Wicked Problems in Strategic Management with Systems Thinking. Strateg. Organ. 2023, 21, 721–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boons, F.; Lüdeke-Freund, F. Business Models for Sustainable Innovation: State-of-the-Art and Steps towards a Research Agenda. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 45, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceschin, F.; Gaziulusoy, I. Evolution of Design for Sustainability: From Product Design to Design for System Innovations and Transitions. Des. Stud. 2016, 47, 118–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takacs, F.; Braun, M.; Wehinger, M.; Frankenberger, K. Breaking Barriers: Accelerating the Transition to a Circular Economy. Swiss J. Bus. 2025, 79, 205–240. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.-H.; Hung, P.; Ma, H. Integrating Circular Business Models and Development Tools in the Circular Economy Transition Process: A Firm-Level Framework. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 1887–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manninen, K.; Koskela, S.; Antikainen, R.; Bocken, N.; Dahlbo, H.; Aminoff, A. Do Circular Economy Business Models Capture Intended Environmental Value Propositions? J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 171, 413–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, P.; Kim, A.; Wood, M.O. Hidden in Plain Sight: The Importance of Scale in Organizations’ Attention to Issues. AMR 2018, 43, 217–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ormazabal, M.; Prieto-Sandoval, V.; Puga-Leal, R.; Jaca, C. Circular Economy in Spanish SMEs: Challenges and Opportunities. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 185, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magretta, J. Why Business Models Matter. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2002, 80, 86–92. [Google Scholar]

- Teece, D.J. Business Models, Business Strategy and Innovation. Long Range Plan. 2010, 43, 172–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zott, C.; Amit, R.; Massa, L. The Business Model: Recent Developments and Future Research. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 1019–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterwalder, A. The Business Model Ontology: A Proposition in a Design Science Approach. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Gassmann, O.; Frankenberger, K.; Csik, M. The St. Gallen Business Model Navigator; University of St. Gallen: St. Gallen, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Zott, C.; Amit, R. Business Model Design: An Activity System Perspective. Long Range Plan. 2010, 43, 216–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aversa, P.; Haefliger, S.; Rossi, A.; Baden-Fuller, C. From Business Model to Business Modelling: Modularity and Manipulation. In Advances in Strategic Management; Baden-Fuller, C., Mangematin, V., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2015; Volume 33, pp. 151–185. ISBN 978-1-78560-463-8. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, L.L.; Rindova, V.P.; Greenbaum, B.E. Unlocking the Hidden Value of Concepts: A Cognitive Approach to Business Model Innovation: A Cognitive Approach to Business Model Innovation. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2015, 9, 99–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stubbs, W.; Cocklin, C. Conceptualizing a “Sustainability Business Model”. Organ. Environ. 2008, 21, 103–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomaa, A.; Juhola, S. How to Assess Sustainability Transformations: A Review. Glob. Sustain. 2020, 3, e24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, N.J.; Blythe, J.; Cisneros-Montemayor, A.M.; Singh, G.G.; Sumaila, U.R. Just Transformations to Sustainability. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocken, N.M.P.; Short, S.W.; Rana, P.; Evans, S. A Literature and Practice Review to Develop Sustainable Business Model Archetypes. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 65, 42–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocken, N.; Short, S.; Rana, P.; Evans, S. A Value Mapping Tool for Sustainable Business Modelling. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2013, 13, 482–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Evans, S.; Vladimirova, D.; Rana, P. Value Uncaptured Perspective for Sustainable Business Model Innovation. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 140, 1794–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, W.; Aurisicchio, M.; Childs, P. Contaminated Interaction: Another Barrier to Circular Material Flows. J. Ind. Ecol. 2017, 21, 507–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertassini, A.C.; Zanon, L.G.; Azarias, J.G.; Gerolamo, M.C.; Ometto, A.R. Circular Business Ecosystem Innovation: A Guide for Mapping Stakeholders, Capturing Values, and Finding New Opportunities. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 27, 436–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tidd, J. Integrating Technological Market and Organizational Change. In Managing Innovation; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, R.; Jeanrenaud, S.; Bessant, J.; Denyer, D.; Overy, P. Sustainability-Oriented Innovation: A Systematic Review: Sustainability-Oriented Innovation. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2016, 18, 180–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, T.-C.; Smith, S. A Systematic Review of Technologies Involving Eco-Innovation for Enterprises Moving towards Sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 192, 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo-Hermosilla, J.; Del Río, P.; Könnölä, T. Diversity of Eco-Innovations: Reflections from Selected Case Studies. J. Clean. Prod. 2010, 18, 1073–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellström, T. Dimensions of Environmentally Sustainable Innovation: The Structure of Eco-Innovation Concepts. Sustain. Dev. 2007, 15, 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rennings, K. Redefining Innovation—Eco-Innovation Research and the Contribution from Ecological Economics. Ecol. Econ. 2000, 32, 319–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triguero, A.; Moreno-Mondéjar, L.; Davia, M.A. Drivers of Different Types of Eco-Innovation in European SMEs. Ecol. Econ. 2013, 92, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markides, C. Disruptive Innovation: In Need of Better TheoryÃ. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2006, 23, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tukker, A. Eight Types of Product–Service System: Eight Ways to Sustainability? Experiences from SusProNet. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2004, 13, 246–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konietzko, J.; Bocken, N.; Hultink, E.J. Circular Ecosystem Innovation: An Initial Set of Principles. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 253, 119942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jesus Pacheco, D.A.; ten Caten, C.S.; Jung, C.F.; Ribeiro, J.L.D.; Navas, H.V.G.; Cruz-Machado, V.A. Eco-Innovation Determinants in Manufacturing SMEs: Systematic Review and Research Directions. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 2277–2287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazarika, N.; Zhang, X. Evolving Theories of Eco-Innovation: A Systematic Review. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2019, 19, 64–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paavola, J. Institutions and Environmental Governance: A Reconceptualization. Ecol. Econ. 2007, 63, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foxon, T.J. A Coevolutionary Framework for Analysing a Transition to a Sustainable Low Carbon Economy. Ecol. Econ. 2011, 70, 2258–2267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potting, J.; Hekkert, M.P.; Worrell, E.; Hanemaaijer, A. Circular Economy: Measuring Innovation in the Product Chain. In Planbureau Voor de Leefomgeving; PBL Publishers: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Korhonen, J.; Honkasalo, A.; Seppälä, J. Circular Economy: The Concept and Its Limitations. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 143, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, C.G.; Trevisan, A.H.; Pigosso, D.C.A.; Mascarenhas, J. The Rebound Effect of Circular Economy: Definitions, Mechanisms and a Research Agenda. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 345, 131136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corvellec, H.; Stowell, A.F.; Johansson, N. Critiques of the Circular Economy. J. Ind. Ecol. 2022, 26, 421–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissdoerfer, M.; Pieroni, M.P.P.; Pigosso, D.C.A.; Soufani, K. Circular Business Models: A Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 277, 123741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüdeke-Freund, F.; Gold, S.; Bocken, N.M. A Review and Typology of Circular Economy Business Model Patterns. J. Ind. Ecol. 2019, 23, 36–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocken, N.M.; De Pauw, I.; Bakker, C.; Van Der Grinten, B. Product Design and Business Model Strategies for a Circular Economy. J. Ind. Prod. Eng. 2016, 33, 308–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowski, M. Designing the Business Models for Circular Economy—Towards the Conceptual Framework. Sustainability 2016, 8, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhatre, P.; Panchal, R.; Singh, A.; Bibyan, S. A Systematic Literature Review on the Circular Economy Initiatives in the European Union. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 26, 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morseletto, P. Restorative and Regenerative: Exploring the Concepts in the Circular Economy. J. Ind. Ecol. 2020, 24, 763–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-García, E.; Martínez-Falcó, J.; Marco-Lajara, B.; Manresa-Marhuenda, E. Revolutionizing the Circular Economy through New Technologies: A New Era of Sustainable Progress. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2024, 33, 103509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalmykova, Y.; Sadagopan, M.; Rosado, L. Circular Economy—From Review of Theories and Practices to Development of Implementation Tools. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 135, 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saidani, M.; Yannou, B.; Leroy, Y.; Cluzel, F.; Kendall, A. A Taxonomy of Circular Economy Indicators. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 207, 542–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin-Johnson, E.; Figge, F.; Canning, L. Resource Duration as a Managerial Indicator for Circular Economy Performance. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 133, 589–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamerew, Y.A.; Brissaud, D. Circular Economy Assessment Tool for End of Life Product Recovery Strategies. J. Remanufacturing 2019, 9, 169–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pigosso, D.C.A.; McAloone, T.C. Making the Transition to a Circular Economy within Manufacturing Companies: The Development and Implementation of a Self-Assessment Readiness Tool. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 28, 346–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nußholz, J.L.K. A Circular Business Model Mapping Tool for Creating Value from Prolonged Product Lifetime and Closed Material Loops. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 197, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rexfelt, O.; Selvefors, A. The Use2Use Design Toolkit—Tools for User-Centred Circular Design. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leising, E.; Quist, J.; Bocken, N. Circular Economy in the Building Sector: Three Cases and a Collaboration Tool. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 176, 976–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchini, A.; Rossi, J.; Pellegrini, M. Overcoming the Main Barriers of Circular Economy Implementation through a New Visualization Tool for Circular Business Models. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konietzko, J.; Bocken, N.; Hultink, E.J. A Tool to Analyze, Ideate and Develop Circular Innovation Ecosystems. Sustainability 2020, 12, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, Z.; Masi, D.; Low, J.S.C.; Ng, Y.T.; Tan, P.S.; Barnes, S. Tools for Promoting Industrial Symbiosis: A Systematic Review. J. Ind. Ecol. 2019, 23, 1087–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristoffersen, E.; Blomsma, F.; Mikalef, P.; Li, J. The Smart Circular Economy: A Digital-Enabled Circular Strategies Framework for Manufacturing Companies. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 120, 241–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, C.; Parida, V.; Dhir, A. Linking Circular Economy and Digitalisation Technologies: A Systematic Literature Review of Past Achievements and Future Promises. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 177, 121508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Yazan, D.M.; Junjan, V.; Iacob, M.-E. Circular Economy in the Construction Industry: A Review of Decision Support Tools Based on Information & Communication Technologies. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 349, 131335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levoso, A.S.; Gasol, C.M.; Martínez-Blanco, J.; Durany, X.G.; Lehmann, M.; Gaya, R.F. Methodological Framework for the Implementation of Circular Economy in Urban Systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 248, 119227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blomsma, F.; Pieroni, M.; Kravchenko, M.; Pigosso, D.C.; Hildenbrand, J.; Kristinsdottir, A.R.; Kristoffersen, E.; Shahbazi, S.; Nielsen, K.D.; Jönbrink, A.-K. Developing a Circular Strategies Framework for Manufacturing Companies to Support Circular Economy-Oriented Innovation. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 241, 118271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguiar, M.F.; Jugend, D. Circular Product Design Maturity Matrix: A Guideline to Evaluate New Product Development in Light of the Circular Economy Transition. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 365, 132732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rittershaus, P.; Renner, M.; Aryan, V. A Conceptual Methodology to Screen and Adopt Circular Business Models in Small and Medium Scale Enterprises (SMEs): A Case Study on Child Safety Seats as a Product Service System. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 390, 136083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissdoerfer, M.; Vladimirova, D.; Evans, S. Sustainable Business Model Innovation: A Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 198, 401–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, B.; Winn, M.I. Market Imperfections, Opportunity and Sustainable Entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Ventur. 2007, 22, 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez-León, E.; Reyes-Carrillo, T.; Díaz-Pichardo, R. Towards a Holistic Framework for Sustainable Value Analysis in Business Models: A Tool for Sustainable Development. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 31, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Sustainable Manufacturing and Eco-Innovation; OECD: Paris, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Arranz, C.F.; Arroyabe, M.F.; de Arroyabe, J.C.F. Organisational Transformation toward Circular Economy in SMEs. The Effect of Internal Barriers. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 456, 142307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascucci, F.; Pizzichini, L.; Sabatini, A.; Temperini, V.; Mueller, J. Knowledge-Based Dynamic Capabilities for Managing Paradoxical Tensions in Circular Business Model Innovation: An Empirical Exploration of an Incumbent Firm. J. Knowl. Manag. 2024, 28, 255–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.; Nguyen-Thi-Phuong, A. The Influence of Financial and Non--financial Factors on the Adopting Intentions of Businesses towards Circular Business Models: Evidence from Vietnam. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. 2024, 31, 5894–5910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awan, U.; Sroufe, R. Sustainability in the Circular Economy: Insights and Dynamics of Designing Circular Business Models. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Kolpinski, C.; Yazan, D.M.; Fraccascia, L. The Impact of Internal Company Dynamics on Sustainable Circular Business Development: Insights from Circular Startups. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2023, 32, 1931–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Täuscher, K.; Abdelkafi, N. Visual Tools for Business Model Innovation: Recommendations from a Cognitive Perspective. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2017, 26, 160–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tura, N.; Hanski, J.; Ahola, T.; Ståhle, M.; Piiparinen, S.; Valkokari, P. Unlocking Circular Business: A Framework of Barriers and Drivers. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 212, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truant, E.; Giordino, D.; Borlatto, E.; Bhatia, M. Drivers and Barriers of Smart Technologies for Circular Economy: Leveraging Smart Circular Economy Implementation to Nurture Companies’ Performance. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 198, 122954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scipioni, S.; Niccolini, F. How to Close the Loop? Organizational Learning Processes and Contextual Factors for Small and Medium Enterprises’ Circular Business Models Introduction. Sinergie Ital. J. Manag. 2021, 39, 141–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbinati, A.; Rosa, P.; Sassanelli, C.; Chiaroni, D.; Terzi, S. Circular Business Models in the European Manufacturing Industry: A Multiple Case Study Analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 274, 122964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ünal, E.; Urbinati, A.; Chiaroni, D. Managerial Practices for Designing Circular Economy Business Models: The Case of an Italian SME in the Office Supply Industry. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2019, 30, 561–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, A.; Sharma, P.; Vinu, A.; Karakoti, A.; Kaur, K.; Gujral, H.S.; Munjal, S.; Laker, B. Circular Economy Adoption by SMEs in Emerging Markets: Towards a Multilevel Conceptual Framework. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 142, 605–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zils, M.; Howard, M.; Hopkinson, P. Circular Economy Implementation in Operations & Supply Chain Management: Building a Pathway to Business Transformation. Prod. Plan. Control. 2025, 36, 501–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkinson, P.; De Angelis, R.; Zils, M. Systemic Building Blocks for Creating and Capturing Value from Circular Economy. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 155, 104672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |