Abstract

As a key indicator for measuring urban green visibility, the Green View Index (GVI) reflects actual visible greenery from a human perspective, playing a vital role in assessing urban greening levels and optimizing green space layouts. Existing studies predominantly rely on single-source remote sensing image analysis or traditional statistical regression methods such as Ordinary Least Squares and Geographically Weighted Regression. These approaches struggle to capture spatial variations in human-perceived greenery at the street level and fail to identify the non-stationary effects of different drivers within localized areas. This study focuses on the Luolong District in the central urban area of Luoyang City, China. Utilizing Baidu Street View imagery and semantic segmentation technology, an automated GVI extraction model was developed to reveal its spatial differentiation characteristics. Spearman correlation analysis and Multiscale Geographically Weighted Regression were employed to identify the dominant drivers of GVI across four dimensions: landscape pattern, vegetation cover, built environment, and accessibility. Field surveys were conducted to validate the findings. The Multiscale Geographically Weighted Regression method allows different variables to have distinct spatial scales of influence in parameter estimation. This approach overcomes the limitations of traditional models in revealing spatial non-stationarity, thereby more accurately characterizing the spatial response mechanism of the Global Vulnerability Index (GVI). Results indicate the following: (1) The study area’s average GVI is 15.24%, reflecting a low overall level with significant spatial variation, exhibiting a “polar core” distribution pattern. (2) Fractal dimension, normalized vegetation index (NDVI), enclosure index, road density, population density, and green space accessibility positively influence GVI, while connectivity index, Euclidean nearest neighbor distance, building density, residential density, and water body accessibility negatively affect it. Among these, NDVI and enclosure index are the most critical factors. (3) Spatial influence scales vary significantly across factors. Euclidean nearest neighbor distance, building density, population density, green space accessibility, and water body accessibility exert global effects on GVI, while fractal dimension, connectivity index, normalized vegetation index, enclosure index, road density, and residential density demonstrate regional dependence. Field survey results confirm that the analytical conclusions align closely with actual greening conditions and socioeconomic characteristics. This study provides data support and decision-making references for green space planning and human habitat optimization in Luoyang City while also offering methodological insights for evaluating urban street green view index and researching ecological spatial equity.

1. Introduction

Against the backdrop of rapid urban expansion, residents’ demand for high-quality green spaces has grown. Urban street greening constitutes a vital component of the cityscape, playing a significant role in mitigating urban flooding, reducing noise pollution [1], alleviating the urban heat island effect [2], and improving residents’ psychological well-being [3]. As urbanization accelerates, scientifically evaluating and enhancing the quality of urban street greening has become a pressing core issue. However, most existing studies rely on remote sensing images or statistical data to assess the level of urban greening, often being limited to macro-scale indicators such as green coverage or greening rate, making it difficult to reveal the true perception differences in urban green Spaces from the perspective of residents’ daily experiences. This deficiency mainly stems from the limitations of macro-scale remote sensing data. Although it can provide overall information on the distribution of green Spaces, it ignores the human-oriented perception at the street scale, such as the green plant shading under the pedestrian’s line of sight, the diversity of tree species along the street, or the continuity of greenery along the walking path. These factors directly affect residents’ psychological comfort, choices of leisure activities, and travel experience. Therefore, relying solely on remote sensing data may lead to a discrepancy between urban planning decisions and the actual perception of residents, thereby limiting the effectiveness of optimizing green Spaces and enhancing ecological welfare. Furthermore, apart from the overall greening level, the imbalance in greening exposure among different regions and its potential socio-economic driving mechanisms still lack systematic research, further highlighting the necessity of conducting refined analysis from the perspective of residents.

Against this backdrop, the Green View Index (GVI) has garnered significant attention in recent years as a crucial metric for quantifying urban greening and human habitat research. First proposed by Japanese scholars in 1987, this concept represents the proportion of green vegetation within human visual fields [4]. Unlike traditional urban greening rates, GVI transcends the two-dimensional perspective of remote sensing, extending to human-scale three-dimensional perception [5], making it a crucial metric for measuring urban green perception. Early GVI calculations often relied on manual photo extraction methods [6], which were inefficient and susceptible to subjective bias. Currently, deep learning-based semantic segmentation techniques have become the mainstream method for GVI calculation [7,8], laying a solid foundation for large-scale GVI computation. Simultaneously, numerous scholars have integrated GVI with landscape and socioeconomic indicators to explore the distribution patterns of green spaces and their mechanisms of action on ecological environments and resident well-being [9,10], establishing a basis for green space planning and ecological environment optimization. In recent years, the continuous advancement of street view imaging technology has further propelled the deepening of GVI research. Related studies have demonstrated the multifunctionality of street view imagery in capturing variations in urban greening, providing a methodological framework for analyzing Luoyang’s urban greening index [11,12,13]. However, street view imagery still has certain limitations in terms of capture timing, perspective variations, and spatial coverage, which may lead to calculation deviations in the Green Vegetation Index (GVI). This study effectively mitigates the impact of these factors through high-density street view sampling and automated semantic segmentation processing, thereby enhancing the representativeness and accuracy of GVI measurements.

As such, street-level imagery serves not only as a crucial data source for precise GVI calculations but also offers a novel research pathway for exploring urban green spaces from a human-centered perspective, providing a more authentic reflection of residents’ visual perceptions of urban environments. Currently, street view imagery covers half of the global population [14], featuring higher update frequencies and richer information dimensions. Consequently, it plays a vital role in building data [15,16,17,18], green space [19,20,21,22], public health [23,24,25], urban morphology [26,27,28], transportation and accessibility [29,30,31], socioeconomic research [32,33], and urban perception [34,35,36]. In recent years, scholars have further integrated multi-source urban imagery with spatial big data to explore the spatial matching relationship between urban green spaces and population distribution [37], offering new insights for optimizing ecological spaces and conducting equity analyses based on street-level imagery. Leveraging street-level imagery and deep learning technologies enables automated recognition and quantification of diverse objects, including roads, buildings, vegetation, and sky, significantly enhancing the scalability and precision of GVI measurement [38].

Existing research indicates that GVI exhibits not only significant spatial variation but also results from the combined influence of multiple factors. High GVI levels contribute to enhanced urban ecosystem services [39,40], optimized urban patterns, and improved resident mental health [41]; while low GVI may pose ecological risks, health hazards, and social inequities. Therefore, elevating GVI levels is crucial for urban development. Furthermore, GVI levels are closely linked to various factors, such as population and economic status [42,43], building density and layout, road density, elevation environment [44], and vegetation types and quantities [12,45,46], and landscape patterns [5,47]. However, existing studies predominantly focus on single factors, with relatively insufficient exploration of multidimensional, systemic factor systems. Regarding research methodologies for spatial analysis of the GVI, in recent years, some scholars have attempted to incorporate spatial statistics and geographically weighted models into GVI studies to investigate spatial heterogeneity within its driving mechanisms. For instance, some scholars have utilized street-level imagery and multi-source data to apply Geographic Weighted Regression (GWR) models or machine learning-enhanced variants, examining how diverse factors influence GVI’s spatial heterogeneity [48]. Other studies employed Multiscale Geographically Weighted Regression (MGWR) models to further identify the operational scales of different variables, revealing significant variations in GVI’s driving mechanisms across urban districts [13]. Still other studies have analyzed the spatiotemporal variation in GVI using Geographically and Temporally Weighted Regression (GTWR) models at temporal scales [49]. While these investigations have enriched our understanding of the spatial distribution of GVI and its environmental coupling, most practical applications remain focused on macro-scales. Systematic exploration of GVI spatial variation at the street level and the multiscale driving mechanisms of different factors remains limited.

Therefore, this study selected the Luolong District in the central urban area of Luoyang City as the research site. Based on Baidu Street View imagery and semantic segmentation technology, an automated GVI extraction model was constructed to calculate the GVI level of the study area. Combined with spatial autocorrelation analysis and hotspot analysis, this approach further reveals the spatial clustering patterns and hotspot/coldspot distribution characteristics of GVI. An influence factor system was constructed across four dimensions: landscape pattern, vegetation coverage, built environment, and accessibility. Spearman correlation analysis and MGWR were employed to identify dominant drivers and their interactions affecting GVI. Field surveys were conducted to validate the findings. This study aims to systematically reveal the distribution characteristics and dominant driving mechanisms of GVI in Luoyang’s urban space. It provides data support and reference for Luoyang’s green space planning and human habitat optimization, while offering methodological insights for street-level GVI assessment and ecological spatial equity research.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

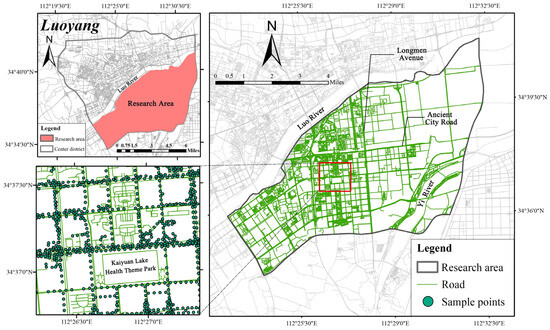

The study area selected for this research is the Luolong District in the central urban area of Luoyang City. Located south of the Luo River, this district serves as the core development zone for Luoyang’s current urban expansion. Compared to the traditional old city area, Luolong District has developed distinct built environment characteristics during rapid urbanization, featuring high-density residential zones, extensive road networks, and diversified functional zoning. Simultaneously, the area boasts a relatively abundant supply of parks and open green spaces. However, green spaces are unevenly distributed across different streets and sub-districts, revealing a pronounced pattern of green space differentiation (Figure 1). This coexistence of built environment and ecological foundations provides an excellent research foundation for exploring GVI spatial differentiation and its influencing factors.

Figure 1.

Study Area Map.

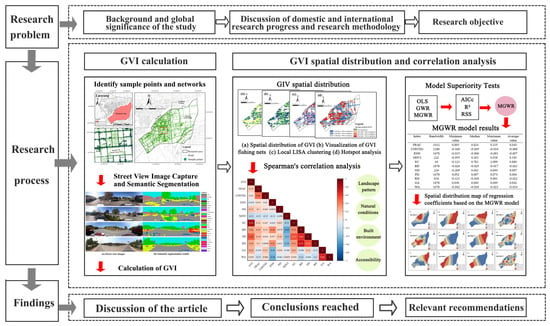

2.2. Research Methodology

This study employs the Green Vegetation Index (GVI) as the core metric to quantify urban greening levels in Luoyang’s Luolong District from a vertical perception perspective. First, Baidu Street View imagery combined with deep learning semantic segmentation methods was used to calculate GVI at both sample point and grid scales, with hotspot analysis revealing spatial distribution patterns of GVI within the study area. Subsequently, multiple influencing factors—including landscape pattern, vegetation cover, built environment, and accessibility—were introduced. Spearman correlation analysis identified global relationships among these factors and detected multicollinearity issues. Finally, the MGWR model was employed to examine the intensity and spatial distribution patterns of each factor’s influence on GVI across different spatial scales, enabling a research progression from quantitative measurement to spatial mechanism analysis (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Research Framework Diagram.

2.2.1. Selection of GVI Influencing Factors

Existing research indicates that the intensity and distribution of GVI are influenced by multiple factors [44]. Based on this, this study selected potential influencing factors for GVI by referencing relevant literature and applying criteria of data availability, quantifiability, and multidimensional coverage. After thoroughly considering multidimensional factors such as landscape patterns, vegetation cover, and built environments, eleven indicators across four categories were ultimately selected (Table 1). This selection balances both direct influences on street green view ratio and potential spatial structural and socio-environmental effects, providing a systematic and comprehensive quantitative foundation for subsequent spatial analysis and modeling.

Table 1.

Selection Criteria for Impact Factors.

2.2.2. GVI Calculation

Identification of Sample Points and Network

First, topological corrections were performed based on OpenStreetMap (OSM) road network data. Using a point generation tool, sampling points were placed along roads at 50 m intervals, yielding a total of 12,162 sample points. Their coordinates were extracted as parameters for street view data collection. To ensure comparability between GVI and landscape pattern indices, a grid-based matching method was further applied. Specifically, the study area was divided into regular 300 m × 300 m grids [42], with the average value of all sample point indicators within each grid serving as its representative value.

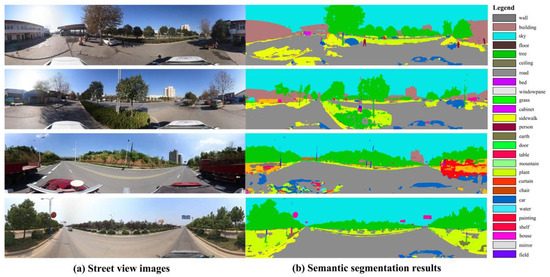

Street View Image Capture and Semantic Segmentation

Using Python programming (PyCharm 2025.1), this study captured 43,648 street view images across the study area at 12,162 sampling points. The raw resolution of each street view tile was 512 × 512 pixels, which were stitched together to form complete panoramic views. With the vertical angle set to 0 degrees, images were captured in four directions (heading = 0, 90, 180, 270) for each sample point—front, rear, left, and right—to create a multi-view street scene dataset.

During semantic analysis, a deep convolutional neural network-based semantic segmentation method was employed to interpret the street scene images. Specifically, this study constructs a semantic segmentation model based on the Pyramid Scene Parsing Network (PSPNet) framework. It adopts a structure comprising a ResNet50-Dilated encoder and a Pyramid Pooling Module (PPM) decoder, pre-trained on the ADE20K dataset (150 classes). This model achieves pixel-level classification for typical urban landscape elements such as buildings, roads, vegetation, and sky. The model comprises three main components: (1) a ResNet50-Dilated backbone network for deep feature extraction; (2) a Pyramid Pooling Module (PPM) to aggregate global and local contextual information across multiple scales; (3) a summarization classification layer to generate pixel-level predictions for final semantic segmentation. Additionally, to ensure segmentation reliability, 100 images were randomly selected for manual annotation. Model outputs were compared against human annotations, and pixel accuracy for the green vegetation category was calculated. Results demonstrate the model’s capability to achieve high-precision segmentation in street-view imagery, providing reliable data support for subsequent GVI quantification. This approach accurately identifies and extracts green elements from complex street scenes, providing data support for subsequent quantitative analysis [60]. The segmentation results are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Schematic Diagram of Semantic Segmentation.

Calculation of GVI

Following the above processing, we calculate the GVI for each sample point using the following formula [61]:

denotes the total number of green vegetation pixels in the “i” direction within a street view image. represents the total number of pixels in the “i” direction within that image. The grid GVI is expressed as the average of the GVI values across all points within the grid.

2.2.3. Urban Green Space Landscape Pattern

Based on land cover data, this study extracted green spaces within the Luolong District of Luoyang’s central urban area to analyze the urban green space landscape pattern. To comprehensively characterize the spatial features of green spaces, the fractal dimension (FRAC), contiguity index (CONTIG), and Euclidean nearest neighbor distance (ENN) were selected across shape, connectivity, and distance dimensions. The Fragstats 4.2.1 software was used to calculate landscape pattern indices for green spaces in the study area.

2.2.4. Spearman Correlation Coefficient

The Spearman correlation coefficient is a nonparametric statistical method measuring the strength and direction of monotonic relationships between two variables. This study used SPSS 26 to calculate the overall correlation between GVI and various influencing factors, identifying potential correlations and detecting possible multicollinearity issues. This provides a reference basis for subsequent multiscale geographically weighted regression (MGWR) modeling.

2.2.5. MGWR Multiscale Geographically Weighted Regression

Multiscale Geographically Weighted Regression (MGWR) extends the traditional Geographically Weighted Regression (GWR) by accommodating both spatially varying regression coefficients and differing spatial scales of influence for various explanatory variable [62]. This method adaptively selects optimal bandwidths based on variable characteristics, enhancing local coefficient estimation accuracy and mitigating multicollinearity. For example, studies indicate that MGWR more effectively captures spatial heterogeneity, improving model fit and predictive performance, and demonstrates distinct advantages in handling variations in the spatial scale of explanatory variables [63,64]. In this study, the MGWR model employs an adaptive kernel function, where the bandwidth value represents the number of nearest samples included in the local regression at each sampling point, rather than a unit of geographic distance. A larger bandwidth indicates a broader spatial influence range of the variable and weaker spatial heterogeneity; a smaller bandwidth suggests the variable primarily exhibits local influence characteristics. This study employs the MGWR model to explore the relationship between GVI and multiple influencing factors, thereby comprehensively revealing the action mechanisms of different factors at various spatial scales. The model formula is as follows:

In the equation, represents the coordinates of the sample point, denotes the regression coefficient for the explanatory variable k, and m is the number of sample points. bwk refers to the bandwidth, and is the error term of the model.

2.3. Data Sources

This study employs a comprehensive approach utilizing multi-source data to provide robust data support for the quantification and impact mechanism research of GVI. The primary data and their sources are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Research Data and Sources.

3. Results

3.1. Spatial Distribution Characteristics of GVI

3.1.1. Spatial Pattern of GVI

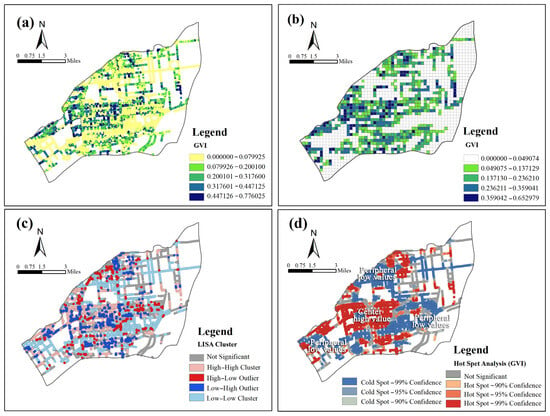

The spatial pattern of GVI provides an intuitive reflection of perceived differences in green landscapes at the urban street level [65], serving as a crucial method for evaluating urban greening levels and distribution equilibrium. Therefore, analyzing the spatial patterns of the Greening Value Index (GVI) in the study area helps identify the distribution characteristics and variations in green resources within the city. Based on the results of semantic segmentation from street-level imagery, the mean GVI value for the study area was calculated to be 15.24%, indicating a relatively low overall level. This suggests that residents have limited access to perceptible green resources in their daily street environments. As shown in Figure 4a,b, GVI exhibits significant local spatial variations. Areas near the northern Luo River and central parks such as the Sui-Tang City Ruins Botanical Garden and Congzhengfang Park exhibit abundant vegetation resources along both sides of the streets, with GVI values generally concentrated at medium-to-high levels (above 0.23). In contrast, peripheral areas of the study zone, predominantly located in suburban villages and regions with sparse road networks, show markedly lower GVI levels, with most grid cells below 0.13. This finding highlights a stark contrast between the central area’s green advantage and the peripheral regions’ green deficiency, revealing an imbalance in the distribution of green resources within the urban landscape.

Figure 4.

Spatial Distribution Patterns of GVI. (a) Spatial Distribution of GVI (b) GVI Fishnet Visualization (c) Local LISA Clustering (d) Hotspot Analysis.

3.1.2. Spatial Heterogeneity of GVI

Spatial heterogeneity refers to the uneven distribution and significant variation in an indicator across different spatial units, reflecting the non-homogeneous characteristics of geographical phenomena in space [66]. To further reveal the significance of the aforementioned spatial pattern characteristics, this study employed spatial autocorrelation analysis to validate the spatial distribution of GVI. The global Moran’s I index was 0.413 (p < 0.01), indicating a significant positive spatial correlation in GVI within the study area. This suggests that areas with similar green view index levels tend to spatially cluster. The local LISA clustering map (Figure 4c) further reveals the aggregation patterns: High-High clusters predominantly occur in the northern and central park green areas, reflecting the significant role of urban centers and river corridors in enhancing surrounding green view index. Low-Low clusters concentrate in the southern and peripheral areas, indicating inadequate green space allocation in these zones and room for improvement in the landscape quality of street spaces. Meanwhile, High-Low and Low-High outliers are scattered, indicating that local “heterogeneous patches” still exist, with significant differences in greening levels compared to surrounding areas.

Hotspot analysis can explore more detailed spatial clusters of GVI (Figure 4d), supplementing the identification of local clusters. The research finds that the spatial distribution characteristics of cold and hot spot aggregation areas are roughly similar to those of GVI, presenting an overall “extreme core” distribution pattern, that is, high GVI areas are concentrated in the urban core area, showing a spatial gradient feature that decreases from the center to the outside. This model reflects that the street scene greening in Luolong District has a significant spatial gradient and central agglomeration effect, which is mainly influenced by the joint effect of urban functional zoning and the distribution of green space resources. The cold spots are mainly concentrated in the commercial areas on both sides of Longmen Avenue and the surrounding village areas, reflecting the problems of dense commercial land and insufficient greening in the urban-rural fringe. The hotspots are mainly concentrated in the residential area and park green space on the south side of the ancient city Road in the middle, which has a good foundation for greening. Overall, the central urban area has formed a high-value core due to its dense park green Spaces, well-developed road greening, and the connection of river corridors (such as the Yi River and the Luo River). However, the peripheral areas are constrained by high land use intensity and insufficient green space, resulting in a generally low green view rate. The results of spatial autocorrelation and hotspot analysis mutually confirm each other, not only revealing the overall aggregation trend of GVI, but also highlighting the differences in greening levels among different functional areas.

3.2. Analysis of Influencing Factors

3.2.1. Multiple Regression Model

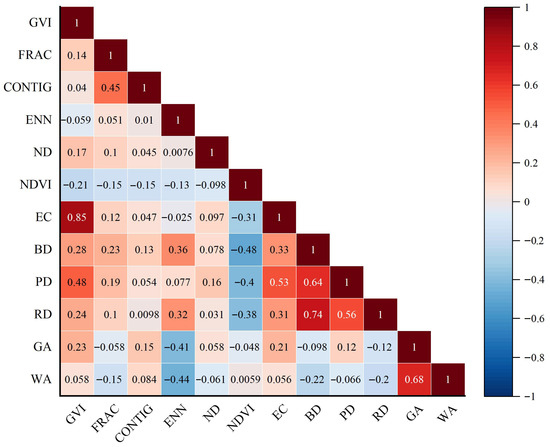

To explore the relationship between various influencing factors and GVI, this study first employed Spearman’s correlation coefficient for exploratory analysis of the global linear relationships among variables (Figure 5). This identified potential multicollinearity issues and provided a reference for subsequent modeling. Results showed that most correlation coefficients had absolute values below 0.5, indicating no severe multicollinearity among variables.

Figure 5.

Correlation Matrix of Influencing Factors.

In empirical studies, commonly used models include OLS and GWR. OLS assumes spatially stable relationships among variables but ignores spatial non-stationarity. GWR incorporates spatial location factors to reveal local variations across geographic locations, yet still assumes all explanatory variables operate at the same spatial scale, failing to fully capture the differentiated influence ranges of multiple factors within complex urban systems. To address these limitations, this study introduces MGWR, which not only accounts for spatial correlation and non-stationarity but also allows different explanatory variables to operate at their optimal spatial scales. Based on this, we compare the fitting performance of OLS, GWR, and MGWR models (Table 3). The results show that the residual sum of squares (RSS) of the MGWR model is 654.734, which is significantly lower than 1141.959 of the OLS model and 984.650 of GWR. This indicates that the MGWR model has a better fitting effect. Meanwhile, its AICc value is the lowest, R2 is the highest, and the overall goodness of fit is the best. Furthermore, since the GVI values are mainly concentrated between 0.2 and 0.8 and have a stable distribution, the Gaussian form of MGWR can effectively meet the model assumptions. This model can more accurately depict the mechanism of action of various influencing factors on GVI in different regions and reveal the complex driving process behind the spatial differentiation of urban green visibility.

Table 3.

Comparison of Regression Model Fit and Results.

3.2.2. Overall Regression Effects

The MGWR model results are presented in Table 4. Based on the average values of overall regression coefficients, significant differences exist in the effects of various influencing factors on GVI. FRAC, NDVI, EC, ND, PD, and GA collectively exhibit positive effects, with EC and NDVI demonstrating higher average coefficients as key factors enhancing green view index. This indicates that the sense of enclosure in street spaces and vegetation coverage levels are crucial for shaping residents’ visual perception of greenery. Conversely, CONTIG, ENN, BD, RD, and WA exhibit overall negative effects, suggesting that areas with high building density, overly connected green space patterns, and high road density often diminish the perception of greening in street scenes. Meanwhile, water body landscapes fail to directly translate into higher GVI at the street scale, potentially due to limited visibility of water bodies within street spaces. Notably, NDVI, EC, ND, and RD exhibit significant spatial heterogeneity. In some areas, they correlate positively with GVI, while in others they show negative effects. This finding reveals the complexity and nonlinearity of urban green visibility formation mechanisms, where the same factor may produce opposite effects across different spatial contexts. For instance, high vegetation coverage significantly enhances perceived street greening in some areas, but in zones with uneven vegetation distribution or spatial crowding, it may negatively impact the street landscape experience.

Table 4.

MGWR Model Results.

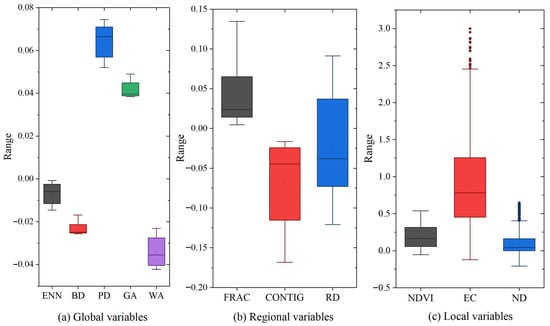

3.2.3. Spatial Scale Differences

Different landscape and socioeconomic indicators exhibit significant spatial scale differences in their effects on GVI. This study employs adaptive kernel bandwidth, where the bandwidth value represents the number of nearest neighbor samples included in local regression. This approach characterizes the spatial influence range and relative scale of explanatory variables, thereby identifying their global or local influence characteristics. Based on bandwidth size, variables can be categorized into three types: global, regional, and local (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

MGWR Coefficient Box Plots. (a) Global Variables; (b) Regional Variables; (c) Local Variables.

Global variables include ENN, BD, PD, GA, and WA, all with bandwidths exceeding 1300. This indicates that these indicators exert a relatively stable influence on GVI within the study area, with minimal spatial heterogeneity. These factors primarily reflect structural characteristics at the overall pattern level, exerting relatively balanced regulatory effects on street-level green view ratio.

Regional variables include FRAC, CONTIG, and RD, all classified as medium-scale variables exhibiting notable regional variability. For instance, RD’s impact on GVI differs between urban areas and surrounding green spaces, while FRAC and CONTIG also demonstrate regionalized effects on block-level green view ratio.

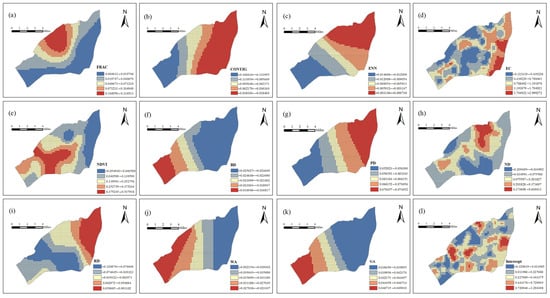

Local variables include NDVI, ND, and EC, whose bandwidths are 222, 224, and 44 pixels, respectively, and they reveal pronounced spatial heterogeneity. This indicates that micro-scale spatial structures exert strong localized regulation on street GVI. Notably, NDVI significantly enhances GVI in the mid-western high-greenery residential areas but has a limited effect in eastern village zones, even exhibiting negative impacts in some locations (Figure 7e). NDVI’s influence is equally pronounced (Figure 7h). For instance, high-density road areas often exhibit low GVI due to spatial constraints and insufficient greening, whereas low-density road areas benefit from more advantageous greenery configurations, yielding higher GVI values. EC exhibits the strongest spatial specificity (Figure 7d). This may stem from the fact that in some streets, a high degree of enclosure significantly reduces GVI, while on open, well-landscaped roads, the negative effect is markedly weakened. This highlights the differential impact of street spatial enclosure characteristics on residents’ visual experience.

Figure 7.

Spatial Distribution Map of Regression Coefficients Based on the MGWR Model. (a) FRAC; (b) CONTIG; (c) ENN; (d) EC; (e) NDVI; (f) BD; (g) PD; (h) ND; (i) RD; (j) WA; (k) GA; (l) Intercept.

4. Discussion

This study employs street-level big data and the MGWR model to examine the spatial distribution characteristics and driving mechanisms of the GVI in Luolong District, Luoyang City from multiple dimensions. Compared to previous studies relying on remote sensing imagery, this research introduces methodological and analytical innovations: MGWR identifies the spatial heterogeneity effects of landscape patterns, built environment, vegetation coverage, and accessibility on GVI, revealing more detailed influence differences across scales. Theoretically, it validates the scale mismatch between “macro-level green connectivity” and “micro-level street-level visible green quantity.” Practically, it exposes the imbalance in green perception between central and peripheral areas, proposing countermeasures including landscape optimization, environmental coordination, and accessibility enhancement. This research offers a new analytical perspective for understanding the multiscale response mechanisms and optimization pathways of urban green perception.

4.1. Analysis of Spatial Pattern Characteristics of GVI

Existing research indicates that GVI exhibits significant spatial differentiation across regions [44,51]. Generally, central urban districts or well-planned areas tend to have higher GVI values, primarily due to the concentrated distribution of public green spaces, parks, and roadside green belts, coupled with enhanced greening levels in residential areas. In contrast, older residential neighborhoods and industrial zones generally exhibit lower GVI values, largely attributable to insufficient roadside greening, poor connectivity of green spaces, and ecological space compression caused by expanding construction land. This pattern is observable across different cities and regions, though its specific manifestation varies due to differences in urban functional layouts and spatial structures.

The findings of this study corroborate this conclusion, revealing significant spatial variations in GVI within Luolong District, the central urban area of Luoyang. Overall, GVI exhibits a “polar core” spatial distribution pattern: the urban core demonstrates pronounced green advantages supported by large parks and residential zones, while urban-rural fringe areas, commercial development zones, and village clusters generally exhibit lower green view index. Field investigations reveal that in central areas like the Sui-Tang City Ruins Botanical Garden, roadside green belts surrounding large parks are wide with high vegetation coverage, making green landscapes a prominent feature in street views. In contrast, many villages and suburban roads in peripheral areas suffer from inadequate greening. Street sides often feature exposed ground, hard surfaces, or low shrubs, lacking clusters of trees or landscape vegetation, resulting in low green view index.

Compared with the research results of other cities, the average GVI of Luolong District, Luoyang City is 15.24%, significantly lower than some developed countries, such as 21% in Singapore [21] and 22.8% in Hartford, Connecticut, USA (2018) [67]. Compared with major cities in China, Luolong District of Luoyang City is slightly higher than the average level of major cities in the north, such as 17.2% ± 12.8% within the Sixth Ring Road of Beijing [53], but significantly lower than the average level of major cities in the south, such as 27% to 29% in Futian District of Shenzhen [51]. This indicates that although Luoyang has a certain foundation in terms of street greening and visual green volume, there is still room for improvement in the richness of green layers in high-density urban areas, the continuity of road greening, and the proportion of visible vegetation in street scenes. Especially in the urban-rural fringe areas and newly developed regions, the green view index is generally low, indicating that the greening system has not yet formed a stable visual network structure. This pattern not only highlights the significant contribution of central urban public green spaces to residents’ visual green volume but also reveals the shortage of green resources in peripheral areas. This “uneven distribution of green space” may exacerbate disparities in residents’ daily environmental experiences to some extent [68] and could have profound implications for social equity and quality of life [69]. Therefore, the key to optimizing the urban green view index in the future lies in enhancing greening levels in peripheral areas while maintaining the green advantages of central urban districts.

4.2. Analysis of GVI Mechanisms

Different categories of influencing factors exert varying intensities and directions on GVI. Their effects manifest not only in overall significant differences but also in distinct spatial scale variations. Existing research indicates that GVI is influenced by multiple factors. Objective factors include socioeconomic conditions [42,43], natural conditions [44], street affiliation [62,70], and functional zoning. Subjective factors include human behavior and photographic parameters [71]. Among these variables, some exhibit stable global effects across the entire study area, while others demonstrate regional or highly localized spatial heterogeneity. This indicates that urban green perception is not driven by a single factor but results from the combined effects of multidimensional, multiscale factors.

4.2.1. Landscape Pattern Factors

Regarding landscape pattern factors, FRAC exerts a significant positive influence on GVI, indicating that more complex green patch patterns enhance the perceived green view index in street scenes, creating visual exposure. This aligns with Zhang’s findings [51]. However, CONTIG and ENN exerted negative effects on GVI, suggesting that overly connected or fragmented green space patterns do not necessarily translate into street-level green perception. Instead, they may diminish the visual coverage of greenery, revealing a scale mismatch between macro-level urban green space planning and micro-level perception. Compared with existing research, this study reveals a distinct scale mismatch between “macro-level rationality” and “micro-level visibility” in green space patterns, suggesting that planning should simultaneously consider overall connectivity and visual exposure at the street level.

4.2.2. Vegetation Coverage Factors

Among natural conditions, NDVI serves as the key variable determining spatial variations in GVI. It exhibits a positive effect in most areas, consistent with findings by Li [53]. Higher NDVI values indicate greater ground vegetation coverage and healthier plant conditions. However, in certain areas—such as villages or zones shaded by high-rise buildings—high NDVI fails to translate into visible street greenery, sometimes even yielding negative effects [72]. This demonstrates that while vegetation coverage is a crucial foundation for enhancing GVI, its impact is modulated by spatial structure and surrounding environments. This finding complements existing research on the spatial differentiation of NDVI’s influence on GVI, demonstrating that high vegetation coverage does not necessarily translate to heightened street-level perception. Spatial obstruction and structural misalignment serve as critical mediating mechanisms affecting this perceptual conversion. This also suggests that in suburban redevelopment and high-rise community design, emphasis should be placed on the visibility of greenery arrangements rather than solely pursuing coverage rates.

4.2.3. Built Environment Factors

Among built environment factors, EC, ND, and PD showed overall positive correlations with GVI, with EC exerting the most significant influence on GVI. This indicates that moderate spatial enclosure can concentrate visual focus and enhance the perceived greening effect. However, BD and RD exert negative effects on GVI, consistent with Zhang’s findings [51] that high-intensity built environments often compress green spaces, obstruct vegetation views, and diminish perceptions of street greenery [45,73]. It is important to note that EC, ND, and RD exhibit differential effects across different areas.

The direction of EC’s effect on GVI primarily depends on whether the enclosing entity is vegetation or buildings; the positive or negative impact of ND is closely related to road grade and greening levels; while RD’s influence on GVI is constrained by residential form and community greening configuration patterns [58]. Therefore, the formation mechanism of GVI is not a simple linear relationship but is jointly regulated by urban spatial patterns and greening levels, further highlighting the MGWR model’s advantage in revealing spatial heterogeneity.

4.2.4. Accessibility Factors

Regarding accessibility factors, existing research confirms that greenery is a key determinant of walking activity [52], though studies examining the impact of water bodies and green space accessibility on GVI remain limited. In this study, GA overall exerts a positive effect on GVI, indicating that residents gain enhanced green visual experiences when green space are within visual reach. However, water bodies exhibit a negative effect on GVI, suggesting that water landscapes do not directly translate into perceived greening advantages at the street scale. This may stem from isolation, obstruction, or spatial misalignment between streets and water bodies, thereby diminishing water visibility. It should be noted that existing research on GVI and walking activity has largely focused on resident behavior and travel time, with relatively insufficient attention to spatial accessibility factors such as green space and water bodies. Therefore, by incorporating GA and WA into the analysis, this study not only expands the research dimensions of GVI influencing factors but also reveals the differential roles of green space and water body accessibility in translating street-level green perception. This provides a new perspective for understanding the connection between green perception and urban public spaces.

4.3. Recommendations for Urban Planning and Management

The findings reveal that the overall green view index in the study area is relatively low, with significant spatial disparities. This indicates that enhancing the perception of urban greenness requires not only increasing overall green coverage but also comprehensive measures addressing spatial layout, structural optimization, and equity improvements. Future planning and management should focus on the following optimizations:

- (1)

- Narrow the gap between central and peripheral areas by enhancing greening in fringe zones. Uneven green space distribution can lead to disparities in residents’ environmental experiences. Therefore, efforts should focus on enhancing street greening in peripheral areas, moderately increasing the number of street trees, pocket parks, and community green spaces. Encourage the use of idle or fragmented spaces for greening to promote a “balanced” supply of green spaces. This will help narrow the environmental gap between central and peripheral areas and mitigate potential environmental equity issues.

- (2)

- Optimize the coordination between the built environment and green space layout. Factors like EC, ND, and BD significantly influence GVI. Planning should control high-density development while ensuring harmony between building enclosures and greenery placement, preventing tall structures from excessively blocking green views. Street design can enhance green visibility within the street’s visual range through “layered” greening (combining trees, shrubs, and grasses), rooftop greening, and vertical greening, thereby strengthening visual continuity at the street scale.

- (3)

- Enhance spatial connectivity and accessibility of green spaces. Cities should leverage the radiating effects of core green areas like the “Sui-Tang Botanical Garden” and “Congzhengfang Park,” improve pedestrian and cycling systems, and design visual corridors along streets to integrate green spaces with daily travel routes. Simultaneously, strengthen greening along the Luo River waterfront and visual connectivity with street spaces to bridge the disconnect between waterfront landscapes and everyday street scenes, making waterfront green spaces an integral part of residents’ daily green experience.

4.4. Limitations and Outlook

This study analyzed the spatial characteristics and influencing mechanisms of street green view index in Luoyang’s central urban area using the MGWR model, revealing the differential effects of multi-scale factors on urban green perception. However, the study has certain limitations. First, the GVI calculations were influenced by the timing, perspective, and coverage of the street view data, potentially failing to fully reflect dynamic changes in greening. The temporal evolution characteristics remain underexplored. Second, the study primarily focused on the Luolong District of Luoyang’s central urban area, limiting its regional representativeness. The applicability of its conclusions to other cities and different socioeconomic contexts requires further validation. Finally, certain socioeconomic and behavioral factors were excluded from the analysis, leaving room for improvement in explanatory power.

Therefore, future research may expand in the following directions: On one hand, integrating multi-temporal street view imagery with remote sensing data to add a time-series dimension could systematically characterize seasonal variations and long-term trends in GVI. Simultaneously, expanding the study area and incorporating resident perceptions and activity patterns would further reveal the spatiotemporal evolution of urban green visibility and its underlying mechanisms, providing more comprehensive evidence for urban green space planning and ecological equity. Second, integrating resident perception surveys, health monitoring data (e.g., psychological stress levels, heart rate variability, walking behavior), and travel activity records could systematically evaluate the potential impacts of street-level greenery on residents’ physical and mental health, participation in recreational activities, and disparities in green experiences across different social groups from environmental psychology, public health, and social equity perspectives.

In summary, despite certain limitations, this study offers a novel methodological framework through MGWR analysis. It expands and complements existing research on the spatial differentiation of GVI correlations with landscape patterns, natural conditions, built environments, and accessibility factors. By revealing the distribution characteristics and dominant driving mechanisms of GVI within Luoyang’s urban space, it provides data support and reference for optimizing Luoyang’s green space planning and human settlements. It also offers methodological insights for street-level GVI assessment and ecological equity research. Future work could further incorporate dynamic time-series data, conduct cross-city comparative studies, and integrate comprehensive analyses of resident perceptions and health impacts. Such approaches would foster a more holistic understanding of the spatiotemporal evolution patterns of urban street-level greenery and its societal benefits.

5. Conclusions

This study systematically calculated the Green Vegetation Index (GVI) for the central urban area of Luolong District, Luoyang City, based on street-level imagery and semantic segmentation technology. By integrating the MGWR model, it thoroughly revealed the spatial differentiation characteristics and driving mechanisms of GVI. Field investigations confirmed that the model’s conclusions align closely with the actual greening levels and socioeconomic features within the study area, providing data support and decision-making references for Luoyang’s green space planning and human settlement optimization. Key findings are as follows:

- (1)

- The mean GVI value in the study area was 15.24%, indicating a generally low level with significant spatial variation. Green exposure differed markedly across streets and districts, exhibiting a spatial distribution pattern characterized by “extreme-core” features.

- (2)

- The intensity and distribution pattern of GVI were influenced by multiple factors, including landscape structure, vegetation cover, built environment, and accessibility. Among these, NDVI and enclosure exerted the most significant effects on GVI.

- (3)

- The MGWR model reveals significant spatial differences in the influence scales of various factors. Among them, ENN, BD, PD, GA, and WA exert global effects on GVI, while factors such as FRAC, CONTIG, RD, NDVI, ND, and EC demonstrate regional dependence.

Author Contributions

J.H.: Conceptualization, Data Curation, Writing—Review and Editing. Y.D.: Methodology, Software, Investigation, Writing—Original Draft. Y.M.:, Visualization, Supervision. D.L.: Conceptualization, Supervision. L.C.: Investigation, Supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Key R&D and Promotion Program of Henan Province (Soft Science), grant number 232400410199, and the Humanities and Social Sciences Research Project of the Henan Provincial Department of Education, grant number 2024ZZJH249.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Nourmohammadi, Z.; Lilasathapornkit, T.; Ashfaq, M.; Gu, Z.; Saberi, M. Mapping urban environmental performance with emerging data sources: A case of urban greenery and traffic noise in Sydney, Australia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muluneh, M.G.; Worku, B.B. Contributions of urban green spaces for climate change mitigation and biodiversity conservation in Dessie city, Northeastern Ethiopia. Urban Clim. 2022, 46, 101294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Zhou, F.; Cai, Y.; Li, C.; Xu, Y. Research on public health and well-being associated to the vegetation configuration of urban green space, a case study of Shanghai, China. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 59, 126990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoki, Y. Relationship between perceived greenery and width of visual fields. J. Jpn. Inst. Landsc. Arch. 1987, 51, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, O.Y.; Russo, A. Assessing the contribution of urban green spaces in green infrastructure strategy planning for urban ecosystem conditions and services. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 68, 102772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falfán, I.; Muñoz-Robles, C.A.; Bonilla-Moheno, M.; MacGregor-Fors, I. Can you really see ‘green’? Assessing physical and self-reported measurements of urban greenery. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 36, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aikoh, T.; Homma, R.; Abe, Y. Comparing conventional manual measurement of the green view index with modern automatic methods using google street view and semantic segmentation. Urban For. Urban Green. 2023, 80, 127845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Yabuki, N.; Fukuda, T. Development of a system for assessing the quality of urban street-level greenery using street view images and deep learning. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 59, 126995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaping, C.; Bohong, Z.; Xiangping, Z. Multidimensional quantization of urban green space based on street view and remote sensing image: A case study of Chenzhou. Econ. Geogr. 2019, 39, 80–87. [Google Scholar]

- Helbich, M.; Poppe, R.; Oberski, D.; van Emmichoven, M.Z.; Schram, R. Can’t see the wood for the trees? An assessment of street view-and satellite-derived greenness measures in relation to mental health. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 214, 104181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rui, J. Measuring streetscape perceptions from driveways and sidewalks to inform pedestrian-oriented street renewal in Düsseldorf. Cities 2023, 141, 104472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, W.; Gou, A. Numerical characteristics and spatial distribution of panoramic Street Green View index based on SegNet semantic segmentation in Savannah. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 69, 127488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, B.; Geng, J.; Ke, S.; Pan, H. Analysis of spatial variation of street landscape greening and influencing factors: An example from Fuzhou city, China. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 21767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, R.; Garcia, L.M.; Goodman, A.; Johnson, R.; Aldred, R.; Murugesan, M.; Brage, S.; Bhalla, K.; Woodcock, J. Estimating city-level travel patterns using street imagery: A case study of using Google Street View in Britain. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0196521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Körner, M.; Wang, Y.; Taubenböck, H.; Zhu, X.X. Building instance classification using street view images. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2018, 145, 44–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, D.; Rueda-Plata, D.; Acevedo, A.B.; Duque, J.C.; Ramos-Pollán, R.; Betancourt, A.; García, S. Automatic detection of building typology using deep learning methods on street level images. Build. Environ. 2020, 177, 106805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Wang, C.; McKenna, F.; Yu, S.X.; Taciroglu, E.; Cetiner, B.; Law, K.H. Rapid visual screening of soft-story buildings from street view images using deep learning classification. Earthq. Eng. Eng. Vib. 2020, 19, 827–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, S.; Li, Y.; Stein, A.; Yang, S.; Jia, P. Street view imagery-based built environment auditing tools: A systematic review. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2024, 38, 1136–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Ye, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Fu, C.; Huang, R.; Yao, D. A data-informed analytical approach to human-scale greenway planning: Integrating multi-sourced urban data with machine learning algorithms. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 56, 126871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Cheng, L.; Chu, S.; Xia, N.; Li, M. A green view index for urban transportation: How much greenery do we view while moving around in cities? Int. J. Sustain. Transp. 2020, 14, 972–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Richards, D.; Lu, Y.; Song, X.; Zhuang, Y.; Zeng, W.; Zhong, T. Measuring daily accessed street greenery: A human-scale approach for informing better urban planning practices. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 191, 103434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Hu, Y.; Tang, L.; Zhuo, Q. Distribution of urban blue and green space in beijing and its influence factors. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Lin, X.; Yang, Y.; Lu, Y. Association of street greenery and physical activity in older adults: A novel study using pedestrian-centered photographs. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 55, 126789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plascak, J.J.; Rundle, A.G.; Babel, R.A.; Llanos, A.A.; LaBelle, C.M.; Stroup, A.M.; Mooney, S.J. Drop-and-spin virtual neighborhood auditing: Assessing built environment for linkage to health studies. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2020, 58, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Helbich, M.; Yao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liu, P.; Yuan, Y.; Liu, Y. Urban greenery and mental wellbeing in adults: Cross-sectional mediation analyses on multiple pathways across different greenery measures. Environ. Res. 2019, 176, 108535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, C.-B.; Zhang, F.; Gong, F.-Y.; Ratti, C.; Li, X. Classification and mapping of urban canyon geometry using Google Street View images and deep multitask learning. Build. Environ. 2020, 167, 106424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middel, A.; Lukasczyk, J.; Zakrzewski, S.; Arnold, M.; Maciejewski, R. Urban form and composition of street canyons: A human-centric big data and deep learning approach. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 183, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Zeng, T.; Zhang, M.; Zeng, P.; Lin, B.; Lu, S. Street microclimate prediction based on Transformer model and street view image in high-density urban areas. Build. Environ. Res. 2025, 269, 112490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, K.; Xu, Y.; Kang, C.; Kwan, M.P. A graph convolutional network model for evaluating potential congestion spots based on local urban built environments. Trans. GIS 2020, 24, 1382–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, P.; Liu, X.; Zhao, Y.; Guo, H.; Lu, Y.; Xue, C.Q. Eye-level street greenery and walking behaviors of older adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinmetz-Wood, M.; El-Geneidy, A.; Ross, N.A. Moving to policy-amenable options for built environment research: The role of micro-scale neighborhood environment in promoting walking. Health Place 2020, 66, 102462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Liu, P.; Chen, M.; Wu, C. Exploring the effects of local environment on population distribution: Using imagery segmentation technology and street view. In Proceedings of the 2020 Asia-Pacific Conference on Image Processing, Electronics and Computers (IPEC), Dalian, China, 14–16 April 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 310–315. [Google Scholar]

- Sytsma, V.A.; Connealy, N.; Piza, E.L. Environmental predictors of a drug offender crime script: A systematic social observation of Google Street View images and CCTV footage. Crime Delinq. 2021, 67, 27–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, W.; Mei, S.; Liu, L.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, S. Multi-task deep relative attribute learning for visual urban perception. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2019, 29, 657–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Peng, N.; Ma, X.; Li, S.; Rao, J. Assessing multiscale visual appearance characteristics of neighbourhoods using geographically weighted principal component analysis in Shenzhen, China. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2020, 84, 101547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Ito, K.; Biljecki, F. Assessing the equity and evolution of urban visual perceptual quality with time series street view imagery. Cities 2024, 145, 104704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, J.; Shao, L.; Sun, S. Evaluation of spatial matching between urban green space and population: Dynamics analysis of winter population data in Xi’an. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2021, 147, 05021012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, I.A.V.; Labib, S. Accessing eye-level greenness visibility from open-source street view images: A methodological development and implementation in multi-city and multi-country contexts. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 103, 105262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Tao, G.; Yan, X.; Sun, J. Influences of greening and structures on urban thermal environments: A case study in Xuzhou City, China. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 66, 127386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Xu, C.; Pu, H.; Nie, Y.; Sun, J. Influence of urban surface compositions on outdoor thermal environmental parameters on an urban road: A combined two-aspect analysis. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 90, 104376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Jiang, B.; Yuan, L. Analyzing the effects of nature exposure on perceived satisfaction with running routes: An activity path-based measure approach. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 68, 127480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhou, C.; Li, F. Quantifying the green view indicator for assessing urban greening quality: An analysis based on Internet-crawling street view data. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 113, 106192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apparicio, P.; Landry, S.; Lewnard, J. Disentangling the effects of urban form and socio-demographic context on street tree cover: A multi-level analysis from Montréal. Sustainability 2017, 157, 422–433. [Google Scholar]

- Gou, A.; Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, C.; Tan, G. Spatial pattern and heterogeneity of green view index in mountainous cities: A case study of Yuzhong district, Chongqing, China. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 12576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miaoyi, L.; Zhonghao, Y.; Feng, X. Urban street greenery quality measurement, planning and design promotion strategies based on multi-source data: A case study of Fuzhou’s main urban area. Landsc. Archit. 2021, 28, 62–68. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Zhao, L.; Mcbride, J.; Gong, P. Can you see green? Assessing the visibility of urban forests in cities. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2009, 91, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, G.; Wu, Z.; Cao, Z.; Chen, Y.; Zheng, Z. Location of greenspace matters: A new approach to investigating the effect of the greenspace spatial pattern on urban heat environment. Landsc. Ecol. 2021, 36, 1533–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Wang, J.; Li, D.; Sun, X.; Zhang, J.; Yang, C.; Zhang, B. Unraveling nonlinear effects of environment features on green view index using multiple data sources and explainable machine learning. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 30189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y. Exploring the spatial and temporal driving mechanisms of landscape patterns on habitat quality in a city undergoing rapid urbanization based on GTWR and MGWR: The case of Nanjing, China. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 143, 109333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, R.V.; Krummel, J.R.; Gardner, R.H.; Sugihara, G.; Jackson, B.; DeAngelis, D.; Milne, B.; Turner, M.G.; Zygmunt, B.; Christensen, S. Indices of landscape pattern. Landsc. Ecol. 1988, 1, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zeng, H. Spatial differentiation characteristics and influencing factors of the green view index in urban areas based on street view images: A case study of Futian District, Shenzhen, China. Urban For. Urban Green. 2024, 93, 128219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ki, D.; Lee, S. Analyzing the effects of Green View Index of neighborhood streets on walking time using Google Street View and deep learning. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 205, 103920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Zheng, X.; Wu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Fu, X.; Deng, H. Spatial relationship between green view index and normalized differential vegetation index within the Sixth Ring Road of Beijing. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 62, 127153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Wang, Z. Measuring visual enclosure for street walkability: Using machine learning algorithms and Google Street View imagery. Appl. Geogr. 2016, 76, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Guan, C. Assessing green space exposure in high density urban areas: A deficiency-sufficiency framework for Shanghai. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 175, 113494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, T.-C.; Lee, P.-H.; Lee, Y.-T.; Tang, J.-H. Exploring the spatial association between the distribution of temperature and urban morphology with green view index. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0301921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, C. Urban population densities. J. R. Stat. Society. Ser. A 1951, 114, 490–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, D.; Chen, S.S. Sustainability, Spatial Mismatching of Residents’ Visible Greening with Green Coverage under the Influence of Urban Morphology. Ecosyst. Health Sustain. 2025, 11, 0359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Luo, S.; Cai, Y.; Lu, Z. Integrating Accessibility and Green View Index for Human-scale Street Greening Initiatives: A Case Study of Chengdu’s Third Ring Road. J. Resour. Ecol. 2024, 16, 356–367. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, B.; Zhao, H.; Puig, X.; Xiao, T.; Fidler, S.; Barriuso, A.; Torralba, A. Semantic understanding of scenes through the ade20k dataset. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2019, 127, 302–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, R.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, J. How green are the streets within the sixth ring road of Beijing? An analysis based on tencent street view pictures and the green view index. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Zhao, J.; Han, L. Exploring the spatial heterogeneity of urban heat island effect and its relationship to block morphology with the geographically weighted regression model. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 76, 103431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouhana, F.; Zhu, J.; Bagtzoglou, A.C.; Burton, C.G. Analyzing structural inequalities in natural hazard-induced power outages: A spatial-statistical approach. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2025, 117, 105184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, Y.; Li, K.; Guo, J.; Zheng, L.; Luo, Y.; Yan, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhao, C.; Shang, X.; Wang, Z. Multi-scale spatio-temporal analysis of soil conservation service based on MGWR model: A case of Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei, China. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 139, 108946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stancato, G. The Visual Greenery Field: Representing the Urban Green Visual Continuum with Street View Image Analysis. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickett, S.T.; Cadenasso, M.L. Landscape ecology: Spatial heterogeneity in ecological systems. Science 1995, 269, 331–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Zhang, C.; Li, W.; Kuzovkina, Y.A.; Weiner, D. Who lives in greener neighborhoods? The distribution of street greenery and its association with residents’ socioeconomic conditions in Hartford, Connecticut, USA. Urban For. Urban Green. 2015, 14, 751–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Lin, T.; Xue, X.; Zhang, G.; Liu, Y.; Zeng, Z.; Zhang, J.; Sui, J. Spatial patterns and inequity of urban green space supply in China. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 132, 108275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, A.; Canters, F.; Khan, A.Z. Analyzing spatial inequalities in use and experience of urban green spaces. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 74, 127674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.; Long, Y. Street greenery: A new indicator for evaluating walkability. Shanghai Urban Plan. Rev. 2017, 1, 32–36. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.; Niu, L. Analysis of Influencing Factors of Green View Index Based on Street View Segmentation. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2024, 48, 517–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Duan, L.; Xu, Y.; Yang, S.; Lin, Z.; Yue, H.; Yang, J. Exploring the influence of urban green space and urban morphology on urban heat Islands using street view and satellite imagery. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 23759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.; Qiu, L.; Su, Y.; Guo, Q.; Hu, T.; Bao, H.; Luo, J.; Wu, S.; Xu, Q.; Wang, Z. Disentangling the effects of the surrounding environment on street-side greenery: Evidence from Hangzhou. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 143, 109153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).