Abstract

Digital transformation represents a strategic imperative for enterprises pursuing high-performance growth. This study selects A-share listed enterprises from 2014 to 2023 as the research sample and empirically examines the impact of digital transformation on enterprise risk-taking, as well as its internal transmission mechanisms, using a fixed effects model. The findings indicate that digital transformation has a significant positive effect on promoting enterprise risk-taking, particularly in state-owned enterprises and those with lower media attention. The director network and economic policy uncertainty positively moderate this relationship. Results from the mechanism analysis show that digital transformation enhances enterprise risk-taking through independent mediating channels that alleviate enterprises’ financing constraints and increase innovation investment, as well as through the chain mediation channel of “alleviating financing constraints → increasing innovation investment”. This research clarifies the specific mechanism underlying the impact of digital transformation on enterprise risk-taking and provides new evidence for understanding how digitalization enhances enterprise risk-taking by easing financing constraints and stimulating innovation. It holds important significance for helping enterprises improve their risk-taking capacity and promote sustainable development.

1. Introduction

Against the backdrop of the ongoing technological revolution, the global economic landscape is undergoing substantial changes. For enterprises, digital transformation has become a necessary choice to keep pace with the trends of the times. It can improve internal cooperation, external communication and management efficiency of enterprises [1], thereby helping them effectively mitigate the negative impacts of low investment return expectations caused by uncertainty. Digital transformation plays a critical role in reshaping enterprises’ investment preferences and, in turn, improving their risk-taking level. Therefore, studying the mechanism through which digital transformation influences enterprise risk-taking holds significant practical value.

Many scholars have delved deeply into the driving factors of enterprise risk-taking, with research perspectives focusing mainly on the macro external environment and the micro-level internal characteristics of corporations. Regarding internal factors, most studies have found that equity structure [2], management incentive and supervision mechanisms [3], and managerial characteristics [4] are significantly correlated with enterprise risk-taking. External factors primarily include various macro level elements such as economic policies [5,6], informal institutions [7], and the policy environment [8].

With the continuous deepening of digital transformation in corporations, scholars have conducted copious empirical tests and theoretical discussions on its economic consequences. From the perspective of enterprise performance, most scholars agree that digital transformation has an active effect on enterprise performance, that is, digital transformation can enhance enterprise performance through low-cost empowerment and innovation empowerment [9,10], alleviating financing constraints for enterprises [11], and improving internal management of enterprises [12], etc. Regarding enterprise innovation, digital transformation promotes innovation through various channels such as knowledge spillover effect [13], optimizing resource allocation and improving information quality [14], enhancing the flow of factors [15], and reducing cost stickiness [16]. In addition, its influence on investment efficiency [17], enterprise value [18], social responsibility [19] and stock liquidity [20] has also drawn attention.

However, the role of digitalization in enterprise risk management has not been fully clarified. When exploring the relationship between the two, studies have indicated that digital transformation supports enterprises in enhancing their risk tolerance [21], especially improving their financial stability and strategic risk-taking [22]. Some research has even identified a “U-shaped” relationship between them [23]. From the above research, it is evident that no consensus has yet been reached on whether enterprises can enhance their risk-taking through digital transformation. In light of this, this study selects Chinese A-share enterprises from 2014 to 2023 as the research sample, based on the following considerations: As a key participant and leader in global digital transformation, China is actively promoting the “Digital China” national strategy, providing both policy support and practical contexts for enterprise digital transformation. Against this backdrop, an in-depth study should be conducted on the relationship between the digital transformation of Chinese enterprises and their risk-taking levels. It aims to clarify the actual influence pathways and key mechanisms linking the two, while providing empirical evidence on the implementation effect of national strategies.

The marginal contributions of this paper lie in the following: (1) It explores the intrinsic mechanism of the relationship between digital transformation and the level of risk- taking. Existing studies mostly examine the independent mediating roles of financing constraints and innovation investment, while neglecting the potential chain mediation path of “financing constraints → innovation investment”. This paper incorporates digital transformation, financing constraints, innovation investment, and enterprise risk-taking into a single research framework. By constructing a chain-based multiple mediation model, it identifies the specific influence pathways through which digital transformation exerts its impact. (2) By applying social network theory to the study of enterprise risk-taking, this paper analyzes the moderating role of director networks in the relationship between digital transformation and enterprise risk-taking, thereby expanding the research boundaries of both fields and deepening the understanding of digital transformation empowering the real economy. It also provides new insights for enterprises seeking to operate steadily and achieve sustainable development in the digital wave.

2. Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Digital Transformation and Enterprise Risk-Taking

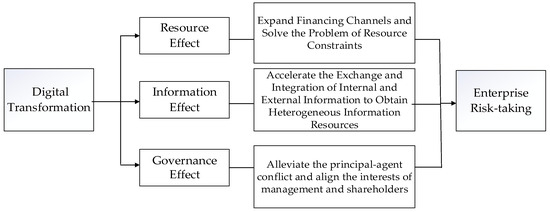

Digital transformation refers to a process in which digital technology, as the core driver, facilitates profound changes in an enterprise’s organizational structure, business boundaries, and value creation methods, ultimately achieving the evolution of the enterprise’s physical entity [24]. This systemic transformation involves not only the adoption of advanced digital tools, but also the reshaping of organizational structures and the in-depth reengineering of business processes [25]. Obviously, enterprises that implement digital transformation can optimize internal management processes [26], dismantle interdepartmental information silos, and effectively mitigate information asymmetry. Additionally, digital transformation helps enterprises expand their financing channels and address resource constraints. By leveraging its resource, information and governance effects, digital transformation profoundly alters managerial decision-making preferences, thereby influencing enterprise risk-taking behavior. Figure 1 presents the specific ways in which digital transformation affects enterprise risk-taking.

Figure 1.

Theoretical analysis framework.

Based on the resource effect dimension, enterprises typically disclose relevant information about their digital transformation strategies, progress and achievements through formal channels such as annual reports. This kind of information disclosure sends positive signals to external stakeholders, attracting investors and strengthening their willingness to increase stock holdings. Meanwhile, the resource effect is also reflected in the diversification of financing channels. Traditional financing methods—such as internal financing, equity financing, and debt financing—are now complemented by emerging forms like invoice financing and supply chain financing in the wave of the digital economy era. This diversification not only expands enterprises’ financing channels, but also improves the feasibility of securing funds for venture capital projects, avoiding enterprises from abandoning valuable projects due to falling into the predicament of “shortage of funds”.

Based on the information effect dimension, the inherent uncertainty of enterprise risk-related activities requires decision-makers to acquire relevant information to mitigate risks [27]. Through digital transformation, enterprises can effectively enhance their information sharing level. This not only breaks down information barriers between internal departments and external partners but also facilitates the rapid circulation, interaction, and integration of information related to the business environment and enterprise resources. By providing abundant heterogeneous information resources, this process reduces the conservative decision-making tendencies of managers caused by information deficits and strengthens enterprises’ risk-bearing capacity.

Based on the governance effect dimension, due to principal–agent conflicts, enterprise managers usually possess more internal information. When choosing investment projects, managers may tend to select short-term projects with low risks for capital investment to avoid personal wealth loss caused by investment failure. The application of digital technology can break down information barriers among various levels and departments within an enterprise, enhance information transparency [21], and reduce information asymmetry, enabling shareholders to supervise management behavior more effectively. Such supervision can exert pressure on managers, prompting them to pay more attention to compliant operations. Meanwhile, competitive advantages derived from digital technology will prompt managers to be more inclined to obtain reasonable personal benefits through hard work, that is, by improving the performance of the enterprise. The motivation to seek personal gain through opportunistic behavior will weaken, which is conducive to achieving the synchronization of the interests and action directions of both the management and shareholders. Enterprise managers, considering the long-term performance of the enterprise, will choose investment projects with higher risks but positive net present values, which helps improve enterprise risk-taking capacity. Hypothesis 1 is proposed:

H1:

Digital transformation promotes the risk-taking of enterprises.

2.2. The Mediating Role of Financing Constraints

When the capital market has not yet achieved full efficiency and information asymmetry exists between enterprises and potential investors, external financing costs rise significantly, making it difficult to obtain the required funds smoothly and thereby creating financing constraints. Higher financing constraints force enterprises to make intertemporal trade-offs between current and future investments. In such cases, internal cash holdings are more vulnerable to cash flow fluctuations, leading to reduced external investments, or even the abandonment of high-risk projects with potential value. Managers thus tend to adopt conservative investment strategies to ensure that all activities in the enterprise’s production and operation processes proceed smoothly and orderly. Digital transformation carried out by enterprises can provide new ideas for reducing the financing constraints of enterprises [28]. According to the signal transmission theory, enterprises that implement digital transformation can send positive signals to the market, serving as credibility endorsements, and earning favorable assessments and positive expectations from the capital market regarding their development prospects. This attracts greater attention from external investors, thereby effectively expanding the financing channels of enterprises and enhancing the flexibility and effectiveness of their fund raising [29]. The improvement of the financing environment enables managers to focus more on projects that are beneficial to the development of enterprises when making investment decisions, as well as effectively identify and seize investment opportunities with dual characteristics of high risk and high return. This strengthens enterprises’ risk-bearing capacity. Hypothesis 2 is proposed:

H2:

Digital transformation promotes enterprises risk-taking by alleviating their financing constraints.

2.3. The Mediating Role of Innovation Investment

Enterprise innovation activities are characterized by long cycles and high risks, resulting in low efficiency in achievement transformation and a relatively low final success rate. Consequently, it is difficult to bring about a substantial improvement in the business performance of enterprises in a relatively short period of time. Moreover, during the innovation process, enterprises must ensure a continuous capital supply to avoid the risk of funding shortages during investment. These features make innovation prone to principal–agent problems. However, digital transformation drives the organizational structure of enterprises towards a flatter direction, effectively breaking down the information barriers across different levels and departments within an enterprise. This enables shareholders to obtain real-time decision-making information related to R&D innovation and production operations. Improved information transparency not only reduces the regulatory costs for shareholders over managers, but also restricts the opportunistic tendencies and self-interested behaviors of the management, thereby reducing agency costs [30], allowing managers to accept short-term performance declines and proactively invest in high-risk innovation projects, thus achieving synchronization of the interests and action directions of both the management and shareholders. As the innovation level of enterprises continues to rise, the comparative advantages they have formed in the fierce market competition, driving managers to focus on enterprises’ long-term development goals and to increase their likelihood of selecting high-risk, high-return decision-making options. This will break their traditional risk aversion and cautious investment risk preferences, enhance managers’ motivation to take risks, and strengthen enterprise risk-bearing capacity. By leveraging digital technologies, enterprises can validly diminish the risk of R&D failure and increase their ability to bear the risk of innovation failure [31], thereby motivating greater investment in risky activities such as innovation [32], and further raising risk-taking levels. Hypothesis 3 is proposed:

H3:

Digital transformation promotes enterprises risk-taking by increasing their innovation investment.

2.4. The Chain Mediating Role of Financing Constraints and Innovation Investment

Digital transformation can effectively alleviate enterprises’ financing constraint pressure and, to some extent, increase their innovation investment. Financing constraints are a main factor influencing enterprises’ innovation investment. Enterprises need continuous and stable financial support to implement innovation activities. Under high financing constraints, enterprises are often in a situation of high financial risks. Relying solely on internal funds of the enterprise cannot support the entire innovation process. Therefore, enterprises need to obtain funds from external financing channels for supplementation. However, the inherent high risks and long cycles of innovation activities further exacerbate information asymmetry. Meanwhile, as external investors (such as financial institutions) tend to avoid risks, enterprises bear higher financing costs, which weaken their financing capacity and restrains their innovative investment. Digital technology reverses this situation by improving the efficiency of information matching, reducing asymmetry [33], accurately assesses financing risks, minimizes economic losses from failed investment and financing. It also enhances investors’ understanding of enterprises’ innovation-related financing decisions, and boosts confidence in enterprises’ future development [34]. This further increases the capital investment of enterprises to facilitate the orderly development of innovation activities.

With sufficient funding, enterprises can better mitigate innovation risks, thereby enhancing their enthusiasm for innovation [35], and the investment in funds for innovation will also increase accordingly. Digital transformation, based on the theory of signal transmission, attracts more high-quality external investment, making projects that were previously shelved by enterprises due to high R&D investment feasible. This provides a guarantee for enterprises to carry out innovation activities, promotes technological progress and enhances innovation capabilities. Enhanced enterprise innovation improves external investors’ expectations for enterprise value growth, creating a positive development of expectations. To some extent, this prompts enterprises to attach importance to their own risk assumption level. Hypothesis 4 is proposed:

H4:

The role of digital transformation in enhancing the risk-taking level of enterprises is achieved through a chain intermediary path of “alleviating financing constraints → increasing innovation investment”.

2.5. The Moderating Role of the Director Network

The director network refers to the social network formed by enterprise directors who hold positions in two or more companies simultaneously. It serves as an important channel for enterprises to obtain essential external information resources and social capital. When depicting the positional characteristics of the director network, two key dimensions are emphasized: network centrality and structural holes. Network centrality measures the degree to which each director in the network occupies a central position within the overall director network of listed companies. Directors with high centrality are often at the hub of information flow: they can quickly obtain information and control key resources [36], thereby directly influencing decision-making. Structural holes measure the potential of individuals in advantageous positions to secure resources and information. Directors with structural hole advantages, by connecting originally isolated information sources, can obtain heterogeneous information and open new channels for the information needed by enterprises for venture capital investment. As the highest decision-making body for the company’s major production and operation activities, the board of directors plays a decisive role in determining whether an enterprise undergoes digital transformation. Specifically, the impact of the director network on the relationship between digital transformation and enterprise risk-taking is mainly reflected in the following aspects:

First, from the perspective of the information effect exerted by the director network, the director network is a critical social network for enterprises, through which enterprises exchange and transmit information via directors’ mobility across different companies. This broadens both the channels and sources of enterprise information [37]. The resulting information advantage helps enterprises promptly obtain technical application experience and information associated with digital transformation, thereby promoting the exchange, sharing and radiation dissemination of digital-related information among network members. This creates a knowledge spillover effect and breaks down the information barriers, accelerating the transformation process.

Second, from the perspective of the governance effect exerted by the director network, the agency problem is a major factor affecting the level of risk assumption of enterprises. To reduce investment failures, managers may abandon certain high-risk projects with positive net present values, resulting in inconsistent goals between enterprise managers and shareholders. Eventually, this is manifested as differences in the willingness of shareholders and management to take risks in the enterprise. It is the responsibility of the board of directors to coordinate risk-taking tendencies between management and shareholders. Directors form a director network by holding positions in different enterprises. Directors embedded in the network can not only accumulate key resources and valuable information from the network, but also have heterogeneous knowledge structures, experiences, etc. They often gain recognition among network members and thus possess certain reputation capital. To consolidate the existing social reputation and avoid reputational damage that could harm future career prospects, directors at the network’s center have stronger governance motivation and a greater willingness to supervise and restrain management [38]. This enhances their ability to identify rent-seeking behavior, reduces managerial opportunism, and alleviates the situation of principal-agent. Such governance encourages managers to choose risky investment projects that contribute to the sustainable enterprise development and enhance their risk tolerance. Meanwhile, digital transformation can also decrease the principal-agent problem. By applying digital technologies, enterprises enhance the operational transparency and real-time performance among various branches within the company. More internal information about business decision-making is held by managers, effectively curbing the opportunistic behavior of managers and achieving consistent goals between enterprise managers and shareholders, further reducing risk aversion. In conclusion, both digital transformation and the director network mitigate principal-agent issues. When combined, the director network strengthens the positive impact of digital transformation on enterprise risk-taking.

Finally, the director network provides an extremely important information channel and resource sharing platform for enterprise members. Enterprises with higher degrees of director network centrality and more structural hole positions can establish more direct or indirect connections with other enterprises. This enables them to quickly grasp heterogeneous cutting-edge information conducive to promoting digital transformation and reducing the risks and uncertainties in the transformation process. Moreover, directors with advantageous network positions have relatively greater control over resources and decision-making influence [39], which provides enterprise managers with more information to assess project risks, feasibility, and risk-reward ratios. In addition, by relying on the director network, enterprise members can establish implicit contractual guarantees by forming alliance relationships and enhance the enterprise’s risk-taking level through risk sharing. In conclusion, the director network not only improves the efficiency of digital transformation but also supports high-risk and high-return investment projects, contributing to stronger enterprise risk-bearing capacity. Hypothesis 5 is proposed:

H5:

The director network positively moderates the relationship between digital transformation and enterprise risk-taking.

2.6. The Moderating Effect of Economic Policy Uncertainty

As micro-entities of the real economy, enterprises’ production, operation, and investment decisions are inevitably influenced by the external policy environment. The stability of the external policy environment directly affects the risk behavior choices of enterprises. Among the various dimensions of the policy environment, economic policy uncertainty holds particular significance. Economic policy uncertainty refers to situations in which economic entities lack accurate expectations about whether, when, and how the government will change current economic policies, and cannot precisely grasp the impact of macroeconomic policies on business operations and strategic choices [40]. In a complex and volatile external environment, compared with specific industrial support policies, economic policy uncertainty better reflects macro-level fluctuations and significantly affects enterprises’ risk-bearing capacity during digital transformation. On one hand, the rise in economic policy uncertainty accelerates enterprises’ digital transformation process. Economic policy uncertainty intensifies the financial constraints on enterprises, making it difficult for them to achieve a high return on assets. Enterprises also bear higher external financing costs [41]. The application of digital technology is an effective means of addressing such uncertainty. By leveraging digital tools, enterprises can standardize massive amounts of data into processable information. They provide multi-dimensional information, including non-financial information, to both the supply and demand sides of funds through digital platforms and other channels, reducing the cost for investors to identify enterprise information and enhancing the transparency of information. This positive information effect not only helps external investors objectively understand the financial status, operating conditions and development strategies of enterprises, but also helps alleviate the decision-making risks of external stakeholders caused by information asymmetry, It can more accurately assess the potential of enterprises and improve their financing conditions [42], thereby reducing the excessive risk premiums that enterprises pay to external investors due to uncertainty in the financing process and lowering financing costs. Consequently, under high economic policy uncertainty, enterprises are more motivated to implement digital transformation, effectively enhancing their risk-taking. On the other hand, higher uncertainty deepens the complexity of the investment environment for enterprises, and the uncertainty of the expected rate of return on projects increases. Enterprise managers delay investment due to a negative attitude towards expected returns, resulting in a decrease in the enterprise’s risk-bearing capacity [5]. By applying digital technologies, enterprises enhance their information acquisition and analytical capabilities. Enterprises grasp the dynamics of market demand in real time, effectively analyze market trends, explore investment opportunities and predict the future returns of investment projects, enhancing the willingness of managers to proactively choose high-risk projects in investment decisions. Therefore, the promoting effect of digital transformation on enterprises’ risk-taking will also be more obvious. Hypothesis 6 is proposed:

H6:

Higher economic policy uncertainty enhances the promoting effect of digital transformation on enterprises risk-taking.

3. Methodology

3.1. Sample Selection and Data Sources

This paper selects the A-share listed companies on the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock exchanges in China from 2014 to 2023 as the research samples. Among these sample enterprises, financial listed companies, those with trading statures of ST, *ST and PT, as well as samples with missing relevant financial data are excluded. Finally, 30,417 annual—enterprise observations are acquired. All the data from the CSMAR database. All continuous variables are subjected to a 1% quantile Winsorize tailing process.

3.2. Variable Description

3.2.1. The Explained Variable

Enterprise risk-taking (Risk1, Risk2). Following previous studies [2,43], this paper adopts earnings volatility, that is, the degree of fluctuation of earnings before interest and taxes divided by total assets (Roa), to measure risk-taking. The calculation methods of the enterprise risk assumption level indicators Risk1 and Risk2 are as follows: (1) Calculate the annual industry adjusted Roa; (2) Taking every three years (from t-2 years to t years) as an observation window period, calculate the standard deviation and range of the industry-adjusted Roa on a rolling basis, respectively, and finally multiply the results by 100.

3.2.2. Explanatory Variable

Enterprise digital transformation (DT). Referring to existing research [44,45], digital transformation (DT) is measured by the logarithm of the word frequency of relevant keywords in the annual report plus one.

3.2.3. Mediating Variable

Financing Constraints (FC). This indicator is measured by the FC index [46].

Innovation Investment (RD). This paper characterizes an enterprise’s innovation investment by the ratio of R&D input to operating income [47].

3.2.4. Adjusting Variable

Economic Policy Uncertainty (EPU). Referring to existing research [48], the annual index is obtained by taking the arithmetic average of the monthly EPU indices for the year and dividing by 100.

Existing research mainly characterizes the positional features of the director network using network centrality and structural holes. In terms of network centrality, referring to existing research [49,50,51], Degree centrality and closeness centrality are selected to measure the director network. Drawing on the research of Zaheer and Bell [52], the director network structure hole is measured by the difference between 1 and the constraint index.

3.2.5. Control Variable

The control variables selected in this paper are shown in Table 1, with industry and time effects also controlled.

Table 1.

Variable explanation.

3.3. Model Design

The benchmark regression model for digital transformation and enterprise risk-taking is as follows:

represents the risk-taking level of enterprise i in year t. represents the degree of digital transformation of enterprise i in year t. The others are control variables. , and respectively represent the annual fixed effect, industry fixed effect, and random disturbance term. If is significantly positive, it indicates that digital transformation promotes enterprises’ risk-taking.

Models (8)–(10) examine the moderating role of the director network in the relationship between digital transformation and enterprise risk-taking:

The moderating variables are network centrality (Degree, Closeness) and structural holes (SH). When the coefficient signs of (, ) and (, )are the same and both are significant, it indicates that network centrality positively moderates the impact of digital transformation on enterprise risk-taking. When the signs are reversed, the relationship between the two will be adjusted in reverse.

Model (11) examines whether EPU plays a moderating role.

4. Result Analysis

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

The descriptive statistical results of the variables are shown in Table 2. The average values of the explained variables, enterprise risk-taking Risk1 and Risk2, are 2.541 and 5.197, respectively, with standard deviations of 3.594 and 6.855. This indicates substantial differences in risk-bearing capacity among different enterprises. The maximum value of DT after logarithmic processing is 5.198. DT has a minimum of 0, with a mean of 1.699, indicating that some listed companies have not yet recognized the importance of digital transformation for their own development.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics.

4.2. Benchmark Analysis

Columns (1) and (2) in Table 3 only control the fixed effects of time and industry. The enterprise digital transformation (DT) is statistically significant with a significance level of 1%, and the regression coefficients are positive, at 0.091 and 0.110, respectively. The last two columns of Table 3 include additional control variables for regression on the original basis. The results show that the coefficients of DT remain significantly positive at the 1% level, suggesting that digital transformation enhances enterprises’ risk-bearing capacity. The explanation for the low R-squares: The R-square measures the extent to which the explanatory variable explains the variation in the explained variable. Its magnitude has no direct correlation with the unbiasedness and significance of the regression coefficient. The core research objective of this paper is to examine the causal relationship between digital transformation and enterprise risk-taking, rather than predicting the specific value of the explained variable through explanatory variables. Moreover, the T-value of the core explanatory variable passes the corresponding significance test. Therefore, Formula 7 is applicable to this study.

Table 3.

Benchmark regression results.

4.3. Test of Moderating Effect

4.3.1. Director Network

The test results for the moderating effect of network centrality (Degree, Closeness) are shown in columns (1) to (4) of Table 4. The regression coefficients of the interaction terms between network centrality and DT have the same sign as the coefficient of DT, both being positive. They are statistically significant at the 1% or 5% level. This indicates that the director network plays a positive moderating role; the more central an enterprise is within the director network, the stronger the promoting effect of DT on enterprise risk-taking.

Table 4.

The moderating role of the director network.

The results for the moderating effect of SH are shown in columns (5) and (6) of Table 4. The regression coefficients of the interaction terms between SH in the director network and DT on enterprise risk-taking are 0.627 and 1.160, respectively. Both are positive and statistically significant, indicating that the richer the director network structure hole, the stronger the promoting effect of digital transformation in enhancing enterprise risk-taking.

4.3.2. Economic Policy Uncertainty

As shown in Table 5, the regression coefficients of the interaction term between economic policy uncertainty and DT (DT × EPU) on enterprise risk-taking are 0.103 and 0.202, respectively. Both are positive and statistically significant, indicating that higher EPU enhances the effect of DT on enterprise risk-taking.

Table 5.

The moderating role of the economic policy uncertainty.

4.4. Robustness Test

4.4.1. Instrumental Variable Method

This paper helps to verify that the in-depth promotion of enterprise digital transformation can enhance their risk-taking, but this conclusion may have endogeneity issues brought by reverse causality. To address this issue, this paper uses the average level of DT of other enterprises in the same industry, year, and province as an instrumental variable (IV), and employs a two-stage least squares (2SLS) test. The results in Table 6 show that the coefficients of both the instrumental variable IV and the explanatory variable DT in the first stage are significantly positive, and there is no insufficient identification of instrumental variables problem. The relevant statistics of the instrumental variable are greater than the critical value of 16.38, and there is no weak instrumental variable problem, which proves that the instrumental variable is reasonable. The second-stage results show that, after controlling for endogeneity, the conclusion that DT promotes enterprise risk-taking remains robust and reliable.

Table 6.

Instrumental variable method test.

4.4.2. Lagging Explanatory Variable

In columns (1) and (2) of Table 7, the DT variable is lagged by one period to ensure that the research conclusion is not affected by endogeneity brought by reverse causality. The digital transformation of enterprises lagging by one period remains significantly positive, suggesting that the conclusion of this paper remains robust.

Table 7.

Lag explanatory variable, control high-dimensional fixed effects method test.

4.4.3. Control High-Dimensional Fixed Effects

To avoid the endogeneity problem caused by the possible systematic changes in DT and enterprise risk-taking over time within industries, an interaction term between industry and year is introduced in Model (7). The last two columns of Table 7 present the regression results with higher-order fixed effects, and DT passes the significance test, indicating that the conclusion is robust after controlling for industry–time trends.

4.5. Analysis of the Action Path

To further explore the influence mechanism of digital transformation on enhancing enterprise risk-taking, referring to existing research [35,57], this paper adopts a chain multiple mediating effect model to examine the mediating channels. Based on Model (7), the following models are further added:

Table 8 reports the regression results for the chain multiple mediating effect involving financing constraints and innovation investment. Model (12) takes enterprise financing constraints as the explained variable. At the 1% significance level, the regression coefficient of DT is significantly negative. This result indicates that digital transformation has a positive effect on alleviating the financing constraints of enterprises. The in-depth advancement of digital transformation can convey a favorable signal of their future development to the outside world, which contributes to establishing a good corporate image, enhancing investors’ attention, and alleviating the financing constraints faced by enterprise. Regression tests based on Model (13) show that the coefficients of DT and financing constraints on innovation investment are 0.006 and −0.051, respectively, both significant at the 1% level. This indicates that DT can facilitate enterprise innovation investment, while financing constraints inhibit it. Model (14) uses enterprise risk-taking as the explained variable. Both DT and financing constraints pass the significance test, with the former positive and the latter negative. However, the coefficient of innovation investment on enterprise risk-taking is significantly positive, indicating that DT and innovation investment promote enterprise risk-taking, while financing constraints play an inhibitory role in enterprise risk-taking.

Table 8.

The regression results of multiple chain mediating effects.

Specifically, in the chain multiple mediating effect model constructed above, the independent mediating effect 1 is composed of digital transformation → financing constraints → enterprise risk-taking, with an effect size of 0.0111 (0.0237). The independent mediating effect 2 is composed of digital transformation → innovation investment → enterprise risk-taking, with an effect size of 0.0305 (0.0679). The chain mediating effect follows the path digital transformation → financing constraints → innovation investment → enterprise risk-taking, with an effect size of 0.001 (0.0021). By comparing the effect values of the three intermediary chains, the independent intermediary effect 2 of innovation investment is greater than the independent intermediary effect 1 of financing constraints and the chain intermediary effect generated by the linkage of financing constraints and innovation investment, highlighting the key role of innovation investment in enhancing enterprises’ risk-taking capacity.

This paper utilizes the Bootstrap method with 5000 samples to test the complex mediating path. All mediating effects in Table 9 are within the 95% confidence interval without zero, indicating that digital transformation can enhance enterprises’ risk-taking through two independent mediating channels: alleviating the financing constraints faced by enterprise and promoting their innovation investment. The risk-bearing level of enterprises can also be enhanced through the chain intermediary transmission path of financing constraints → innovation investment. Among the three paths, the mediating effect of innovation investment is the strongest, accounting for 71.36% (72.25%).

Table 9.

Bootstrap analysis results.

4.6. Heterogeneity Analysis

4.6.1. Nature of Property Rights

Enterprises with different ownership structures face varying resource conditions, policy environments, and social responsibilities. State-owned enterprises have stronger financial and technological capabilities and, due to their political connections, are more likely to obtain resource advantages and policy support, creating favorable conditions for DT. Meanwhile, as extensions of government functions, state-owned enterprises play a significant role as important carriers for the implementation of national policies and social responsibilities. Under the current circumstances of vigorously developing digital technologies, state-owned enterprises are expected to take the lead in digital transformation and serve as examples in achieving the national goal of building a “Digital China.” Consequently, they demonstrate greater initiative in digital transformation. In contrast, owing to the constraints of resources, technology and market competition, non-state-owned enterprises face greater pressure when investing in digital technologies, which may limit their ability to enhance risk-bearing capacity. Theoretically, state-owned enterprises achieve more remarkable results in enhancing their risk-bearing capacity through digital transformation.

To test this hypothesis, a grouped regression analysis is conducted for state-owned and non-state-owned enterprises. The regression coefficient of DT is larger for state-owned enterprises. The coefficient difference between the two groups, tested using the Seemingly Unrelated Regression (SUR) method, is significant at the 1% level (p = 0.0004), confirming the hypothesis. Similarly, the inter-group coefficient difference test (p = 0.0027) also passes, indicating that the promoting effect of DT on risk-taking is stronger in state-owned enterprises. Considering ownership differences, state-owned enterprises should leverage their resource and policy advantages to lead DT, while the government should focus on supporting DT in non-state-owned enterprises. Targeted subsidies and policy measures can help narrow the digital gap between ownership types.

This paper further examines the mediating effect of innovation investment by grouping enterprises according to ownership nature. The results are shown in Table 10 (Risk1). The digital transformation coefficient of non-state-owned enterprises is more significant, and the path coefficient of non-state-owned enterprises from innovation investment to enterprise risk-taking is larger, indicating that the promoting effect of innovation investment on risk-taking is stronger. This difference arises because non-state-owned enterprises face more intense market competition, and innovation is the key means for them to obtain competitive advantages. Therefore, they tend to increase innovation investment. Innovation is essentially a risky activity, so the mediating effect of innovation investment is greater in non-state-owned enterprises. In contrast, state-owned enterprises face milder competitive pressure and are more likely to choose projects with mature technologies and controllable risks rather than high-risk R&D projects. Therefore, the promoting effect of innovation investment by state-owned enterprises on risk-taking in digital transformation is relatively weak. The results in Table 10 (Risk2) show that innovation investment does not play a mediating role in non-state-owned enterprises. This difference may stem from the measurement of enterprise risk-taking. The calculation method of enterprise risk assumption (Risk1), based on the standard deviation of industry-adjusted Roa, reflects the degree of dispersion of earnings fluctuations and focuses on the persistence of fluctuations. In contrast, enterprise risk-taking (Risk2), based on the range of industry-adjusted Roa, reflects only the extreme difference between maximum and minimum earnings. Innovation activities are long-term and high-risk, with slow technology transfer and profitability effects. Therefore, when enterprises invest in innovation to develop new technologies and products, they influence profit fluctuations in the long term, captured by Risk1. Hence, in non-state-owned enterprises, innovation investment mediates the relationship between digital transformation and risk-taking measured by Risk1.

Table 10.

Heterogeneity of property rights.

4.6.2. Media Attention

The impact of digital transformation on enhancing an enterprise’s risk-taking is not static; it may vary depending on the media focus environment in which the enterprise operates. Enterprises with high media attention, due to their high level of external attention, are compelled to enhance the quality of information disclosure, making their production, operations, and investment decisions more transparent. This strengthens investor confidence, helps reduce information asymmetry between enterprises and external investors, and indirectly facilitates smoother financing. Moreover, higher media attention increases the supervisory pressure on enterprise managers. To avoid reputational damage or the perception of pursuing personal gain by rejecting high-risk but positive-return projects, managers are more inclined to invest in projects with higher risks that can achieve long-term value appreciation for the enterprise. This behavior enhances the enterprise’s overall risk-taking capacity. In contrast, enterprises receiving less media attention often face reduced access to financing and higher financing costs due to greater information asymmetry with external investors and stakeholders. This situation affects managers’ perceptions and their willingness to undertake high-risk but value-generating projects. Limited information or fear of salary reductions following project failure may also lead managers to adopt more conservative decision-making. Therefore, compared with enterprises receiving greater media attention, those with lower media exposure can use digital technologies more effectively to break down information barriers, promote information flow, and reduce information asymmetry. This enables managers to acquire more key information relevant to decision-making and helps enterprises seize investment opportunities conducive to development while curbing managers’ risk-averse tendencies. These effects are particularly evident in mitigating principal–agent problems and issues of information asymmetry. Thus, in enterprises with low media exposure, the implementation of DT can more effectively enhance their risk-bearing capacity.

This paper uses the logarithm of the number of media reports (ln (number of reports +1)) as a proxy for media attention. Samples are divided into high and low groups according to the median of this variable for regression analysis. The regression coefficient of DT is larger and more significant in enterprises with lower media attention. The significance test of the inter-group coefficient difference is conducted using the SUR method. The p-value of 0.0005 indicates significance at the 1% level. The results show that the promoting effect of DT on enterprise risk-taking exists mainly in enterprises with lower media attention, while such an effect does not exist in those with higher media attention. Further-more, the coefficient is larger and significant in the low-media group. Overall, among enterprises with lower media attention, DT exerts a stronger promoting effect on risk-taking. In view of these differences, DT can serve as a supplementary internal governance mechanism that improves corporate governance under weak external supervision.

This paper further examines the mediating effect of innovation investment by grouping enterprises according to media attention. The results in Table 11 show that, in enterprises with low media attention, digital transformation plays a stronger role in promoting enterprise risk-taking through innovation investment. The reason for this variation lies in differences in resource allocation. Enterprises with high media attention attract greater investor scrutiny and often divert resources from innovation toward maintaining investor relations. When enterprise resources are directed toward managing investor relations, fewer re-sources are available for long-term value creation activities such as research and development, thereby weakening the promoting effect of innovation investment on enterprise risk-taking. Conversely, enterprises with low media attention face less public and market scrutiny, meaning that the risks associated with innovation—such as R&D failure—are less likely to have negative repercussions. Consequently, these enterprises tend to exhibit higher risk tolerance and are more willing to engage in high-risk projects. As a result, the mediating effect of innovation investment is more pronounced in enterprises with lower media attention.

Table 11.

Heterogeneity of media attention.

5. Conclusions and Implications

5.1. Research Conclusions

Against the backdrop of digital economy development, this paper explores how digital transformation affects enterprise risk-taking and analyzes its underlying transmission mechanisms. The findings show that enterprises actively promoting digital transformation can enhance their risk-taking levels. After conducting robustness tests, including the use of instrumental variables and the substitution of explained variables, this conclusion remains valid. Both the director network and EPU positively moderate the relationship between digital transformation and risk-taking. From the perspective of the mechanism of action, financing constraints and innovation investment exert multiple chain mediating effects between digital transformation and enterprise risk-taking. Further analysis reveals that the positive impact of digital transformation on enterprise risk-taking is more significant in state-owned enterprises and those with lower media attention.

The research helps to clarify the specific mechanism by which digital transformation affects enterprises’ risk-taking, while supporting and enriching the signal transmission theory and the principal-agent theory. Specifically, for enterprises embarking on digital transformation, they can not only enhance their risk-risking capacity through two paths: alleviating financing constraints and increasing innovation investment, but also promote their risk-risking capacity through a progressive path, that is, through a chain-mediation channel involving financing constraints and innovation investment. Firstly, enterprises implementing digital transformation can send positive signals about their sound development to the outside world, attract the attention of external investors, alleviate financing constraints, and enable managers to have sufficient funds to seize favorable investment opportunities. Secondly, digital transformation can effectively break down the information barriers among various levels and departments within an enterprise. Shareholders can obtain more internal information related to the enterprise’s management and decision-making in real time, alleviate principal-agent conflicts, restrain the opportunistic behavior of managers, and encourage managers to invest more funds in high-risk and high-return innovative activities. Finally, by implementing digital transformation, enterprises can improve their financial situation. Consequently, their investment in innovation and research and development (RD) will also increase. Innovation is essentially a critical venture capital initiative. Enterprises’ commitment to advancing innovation means an enhancement in their risk tolerance. Therefore, to a certain extent, this paper enriches the research on enterprise risk-taking, expands the literature on how digital transformation affects micro-entities, and provides empirical evidence for the economic consequences and micro-transmission mechanism of digital transformation.

5.2. Management Suggestions

The research findings hold several practical implications. First, the development of the digital economy presents numerous opportunities for enterprises. In an environment of high uncertainty, digital transformation serves as a strong driving force. Enterprises should actively seize digital dividends and increase their motivation to implement digital transformation. Based on this study’s core conclusion, digital transformation significantly enhances enterprise risk-taking. Therefore, enterprises should elevate digital transformation to a strategic level, establish organizational structures that support it, dismantle traditional departmental silos, and apply advanced technologies such as artificial intelligence and big data analytics. These measures can accelerate data exchange and transmission while ensuring the smooth flow of digital information. Furthermore, it is difficult for enterprises to achieve comprehensive digital transformation independently. Strengthening collaboration with external digital networks and sharing resources through partnerships can expedite the transformation process. Government departments should continue introducing and refining policies that encourage, support, and guide enterprises in digital transformation and include such initiatives as priorities in government work plans.

Second, efforts should focus on breaking through the transmission mechanism of digital transformation by integrating digital technologies into the toolbox for enhancing enterprise innovation investment and alleviating financing constraints. Due to the high-risk and long-cycle nature of innovation activities, continuous and stable financial support is essential. Governments should actively assist enterprises in establishing effective communication channels with external investors, fully leveraging digital technologies to reduce information asymmetry, broaden financing channels, and optimize capital allocation. These measures will provide a solid foundation for enterprises to engage in innovation activities. As enterprises advance innovation, their capacity for risk-taking will also improve.

Finally, in enhancing enterprise risk-taking through digital transformation, enterprises should pay attention to the establishment of director networks and fully utilize their positive facilitating role. When forming boards of directors, listed companies should consider the social capital and network connections of directors. By appointing directors who serve on multiple boards, enterprises can convert key resources and heterogeneous information at the individual level into resources accessible at the organizational level. This approach maximizes the director network’s positive role in integrating internal and external information re-sources, reducing financing risks arising from information asymmetry, and laying a foundation for effective digital transformation.

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

This paper examines the impact of DT on enterprise risk-taking, its underlying mechanisms, and the influence of heterogeneous factors. However, due to research limitations and objective constraints, certain areas require further refinement and depth. First, although China is actively promoting the “Digital China” national strategy—providing policy support and practical scenarios for enterprise digital transformation—this research focuses only on A-share listed enterprises, resulting in incomplete sample coverage. Consequently, the universality of the findings is limited. Future research could explore the effects of DT on enterprise risk-taking in other countries, particularly those with different institutional environments, cultural contexts, or levels of economic development.

Second, this study measures the degree of enterprise DT by analyzing keyword frequencies in annual reports. Although the instrumental variable method is used to alleviate endogeneity, this approach relies on the validity assumption of the instruments, and potential omitted variables or reverse causality may not have been completely addressed. Therefore, future research should explore additional proxy variables for DT to further mitigate endogeneity arising from reverse causality.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.Y. and H.L.; Software, W.Y.; investigation, R.L. and W.Y.; formal analysis and supervision, Q.S. and H.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Graduate Student Scientific and Technological Innovation Project of University of Science and Technology Liaoning (LKDYC202436), 2023 Research Outcomes of Basic Scientific Research Projects of Liaoning Provincial Department of Education (JYTZD2023090) and 2025 Liaoning Province Decision-Making Consultation and New-Type Think Tanks Commissioned Research Projects (Countermeasure Study for Accelerating the Development of Liaoning Coastal Economic Belt).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kusiak, A. Smart manufacturing must embrace big data. Nature 2017, 544, 23–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faccio, M.; Marchica, M.-T.; Mura, R. Large shareholder diversification and corporate risk-taking. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2011, 24, 3601–3641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, H.; Su, Z.; Wang, J. The impact of management equity incentive on firms’ risk-taking under different monitoring conditions. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2025, 97, 103790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Anderson, H.; Chi, J. Managerial foreign experience and corporate risk-taking: Evidence from China. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2023, 86, 102525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, M.F.; Zhang, X.D.; Shen, Y.J. Economic policy uncertainty, internal control and enterprise risk assumption. Stat. Decis. 2021, 37, 169–173. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhang, X.; Tian, X.; Sun, F. Economic policy uncertainty nexus with corporate risk-taking: The role of state ownership and corruption expenditure. Pac. Basin Financ. J. 2021, 65, 101496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Ma, M.; Wang, X. Clan culture and risk-taking of Chinese enterprises. China Econ. Rev. 2022, 72, 101763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Qin, M.; Zhan, F. Industrial policy, enterprise investment risk taking and innovative activities. Financ. Res. Lett. 2025, 86, 108526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.T.; Cao, W.C.; Wang, F. Digital Transformation and Manufacturing Firm Performance: Evidence from China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Tao, C. Can digital transformation promote enterprise performance?—From the perspective of public policy and innovation. J. Innov. Knowl. 2022, 7, 100198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, T.; Marimuthu, A.; Mei, S. Digital marketing, financing constraints, and enhancements in corporate performance. Financ. Res. Lett. 2025, 85, 108221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.; Tong, Y.J. The Influence of Digital Transformation of Foreign Trade Enterprises on Their Business Performance. Discret. Dyn. Nat. Soc. 2022, 2022, 2177689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Gu, G.; Zhu, H.; Guo, L. Has the digital transformation promoted enterprise innovation? Evidence from China. Transnatl. Corp. Rev. 2025, 17, 200109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, N.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Fu, C. Does digital finance foster corporate innovation? Evidence from China. Econ. Anal. Policy 2025, 88, 1502–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, F.; Liu, W. Digital transformation, factor flow, and innovation output. Financ. Res. Lett. 2025, 86, 108836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, J.X.; Teruki, N.; Ong, S.Y.Y.; Wang, Y. Does the Digital Transformation of Manufacturing Improve the Technological Innovation Capabilities of Enterprises? Empirical Evidence from China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, P.; Bi, J.; Zhu, M. Enterprise digital transformation and investment efficiency: Empirical evidence from listed enterprises in China. J. Asian Econ. 2025, 97, 101892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Meng, Z.; Song, Y. Digital transformation and metal enterprise value: Evidence from China. Resour. Policy 2023, 87, 104326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, D.; Tan, Z.; Wang, W.; Zhai, R.-X. Digital transformation and corporate social responsibility engagement: Evidence from China. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2025, 97, 103805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Liu, B. How digital technology improves the high-quality development of enterprises and capital markets: A liquidity perspective. Financ. Res. Lett. 2023, 53, 103683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z. Digital Transformation and Enterprise Risk-Taking. Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 62, 105139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, D.B.; Han, S.N.; Zhao, M.; Xie, J.P. The Impact Mechanism of Digital Transformation on the Risk-Taking Level of Chinese Listed Companies. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.Z.; Xu, L.H. The Influence Mechanism of Digital Transformation Degree on Enterprise Risk-taking Level: An Empir-ical Analysis Based on the Mediating Effect of Enterprise Internal Control Quality. J. Cent. Univ. Financ. Econ. 2024, 101–114. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vial, G. Understanding digital transformation: A review and a research agenda. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2019, 28, 118–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, P.; Alharbi, S.S.; Hunjra, A.I.; Zhao, S. How do ESG ratings promote digital technology innovation? Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2025, 97, 103886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Yu, Y.; Deng, M. The impact of enterprise digital transformation on risk-taking: Evidence from China. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2024, 69, 102285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Li, C.; Wang, S.; Li, Q. Digital transformation, risk-taking, and innovation: Evidence from data on listed enterprises in China. J. Innov. Knowl. 2023, 8, 100332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Yin, J. Digital transformation and ESG performance: The chain mediating role of technological innovation and financing constraints. Financ. Res. Lett. 2025, 71, 106387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.K.; Wu, J.C.; Mei, Y.; Hong, X.Y. Exploring the relationship between digital transformation and green innovation: The mediating role of financing modes. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 356, 120558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Xue, B.S.; Ren, X.F.; Shen, L. A study on the impact of digital transformation on innovation in textile and apparel companies: Evidence from the Chinese market. Ind. Textila 2025, 76, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, D.; Lv, K.Y.; Fan, X.Y.; Zhang, B.C. Foreign executives, digital transformation, and innovation performance: Evidence from Chinese-listed firms. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0305144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Xu, Y.; Zhou, J.; Chen, W. Digital transformation, total factor productivity, and firm innovation investment. J. Innov. Knowl. 2024, 9, 100487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wei, L. The path of digital transformation driving enterprise growth: The moderating role of financing constraints. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2024, 96, 103536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.Q.; Liu, C.Y.; Feng, S. Impact of Digital Transformation on Accelerating Enterprise Innovation-Evidence from the Data of Chinese Listed Companies. Discret. Dyn. Nat. Soc. 2023, 2023, 2727652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, H.Y.; Ma, C.A.; Tang, T.; Hao, F.Y. Research on the Impact Path of Government Innovation Subsidy on Carbon Intensity of Industrial Enterprises—Test of a Chain Multiple Mediation Model. Account. Res. 2024, 150–164. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Feng, H.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Q.; Yang, L. Does a Company’s Position within the Interlocking Director Network Influence Its ESG Performance?—Empirical Evidence from Chinese Listed Companies. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siudak, D. The Influence of Interlocking Directorates on the Propensity of Dividend Payout to the Parent Company. Complexity 2020, 2020, 6262519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Wang, F.J. The associated network embedded decision-making authority allocation and risk-taking of enterprise groups. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0318983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Wang, P.; Cao, Q. Managerial Power and Stickiness of Executive Compensation from the Perspective of Social Network: Based on the Regulation Effect of Board Interlocks. Commer. Res. 2019, 6, 98–108. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulen, H.; Ion, M. Policy uncertainty and corporate investment. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2016, 29, 523–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brogaard, J.; Detzel, A. The asset-pricing implications of government economic policy uncertainty. Manag. Sci. 2015, 61, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manita, R.; Elommal, N.; Baudier, P.; Hikkerova, L. The digital transformation of external audit and its impact on corporate governance. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2020, 150, 119751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, K.; Litov, L.; Yeung, B. Corporate governance and risk-taking. J. Financ. 2008, 63, 1679–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H. ESG rating disagreement and corporate digital transformation. Financ. Res. Lett. 2025, 75, 106903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C. How does enterprise digital transformation affect the cost of debt financing? Based on the perspective of customer concentration risk. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2025, 103, 104426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Zhang, W.; Zhu, X.Y. Does Digital Transformation Promote Enterprise Development?: Evidence From Chinese A-Share Listed Enterprises. J. Organ. End User Comput. 2022, 34, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, H.-J.; Jung, S. Generalist vs. Specialist CEOs: R&D Investment Sensitivity to Stock Price. Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 62, 105081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, S.R.; Bloom, N.; Davis, S.J. Measuring economic policy uncertainty. Q. J. Econ. 2016, 131, 1593–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.; Borjigin, S. Network centrality and market information efficiency: Evidence from corporate site visits in China. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2025, 103, 104585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Shan, Y.G.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y. The greening power of networks: Spillover effect of environmental penalties in director networks. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 375, 124367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Chen, R.; He, F. Seeing the big picture: Board Chair’s network in corporate performance explaining. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2025, 97, 103781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaheer, A.; Bell, G.G. Benefiting from network position: Firm capabilities, structural holes, and performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2005, 26, 809–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, X.D.; Fu, W.B. Does cutting overcapacity increase corporate risk-taking? Evidence from supply-side structural reform in China. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2025, 27, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.Y.; Liu, Y.H.; Xia, B.R. Industrial technology progress, digital finance development and corporate risk-taking: Evidence from China’s listed firms. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0298734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, T.; Chen, Z.; Zhou, C.; Lu, H. The impact of fintech on corporate risk-taking. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2025, 103, 104599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Yang, S.L. The Internet-Based Business Model and Corporate Risk-Taking: An Empirical Study from the Information Empowerment Perspective. Discret. Dyn. Nat. Soc. 2022, 2022, 9755719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.L.; Zhang, F.S. Does the D&O Liability Insurance Affect the Persistence of Corporate Innovation? Sci. Technol. Prog. Policy 2023, 40, 107–118. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).