Abstract

This study examines the role of private investment in promoting multidimensional poverty reduction in a sustainable manner in Vietnam by analyzing both spatial and temporal spillover effects. Provincial panel data for 2010–2024 are employed. To assess the spatial spillover effects, three econometric models are applied: SAR, SEM, and SDM. Diagnostic tests suggest that the SDM model is the most appropriate for the research data. Results based on the contiguity and inverse distance weight matrices show that private investment not only reduces poverty in recipient provinces but also generates benefits for neighboring areas, highlighting the need for coordinated planning of industrial zones and regional economic hubs. To analyze this relationship over both the short-term and long-term horizons, the study employs PMG and CCEP estimators, while the DCCEP model verifies robustness in a dynamic framework. The findings consistently confirm that private investment contributes to multidimensional poverty reduction. An additional result from the DCCEP model indicates that literacy and urbanization rate have significant positive effects on poverty reduction, while these relationships are not detected in other models. This finding carries important implications for building an enabling investment environment to attract and effectively utilize private capital to implement multidimensional poverty reduction strategies towards sustainability and aligned with sustainable development objectives.

1. Introduction

Although poverty is a widely studied issue in economic research, most poverty measurement approaches still primarily rely on a monetary perspective, which only considers household or individual income levels. However, the concept of “poverty” as introduced in the studies of Kakwani & Son [1] and Alkire et al. [2] encompasses a range of non-income dimensions such as education, health, housing, and other basic services. Therefore, relying solely on one-dimensional poverty indices is unlikely to fully and comprehensively capture the complex nature of poverty. This limitation reduces the ability to provide comprehensive information for policymakers in formulating poverty reduction strategies [3]. In this context, many organizations have proposed adopting a more comprehensive methodology to measure poverty in order to address the limitations of the one-dimensional approach, with the aim of building a more holistic poverty assessment system [4].

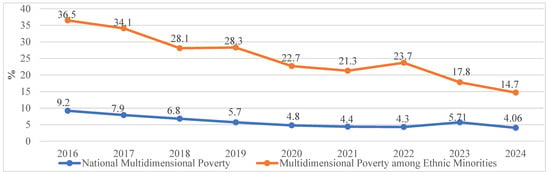

Since 2016, Vietnam has been among the first countries in the Asia-Pacific region to adopt a multidimensional poverty reduction approach. The multidimensional poverty indices not only include income but also consider non-monetary dimensions such as employment, health, education, housing, access to clean water and sanitation, and information, as stipulated in Decision No. 59/2015/QD-TTg and Decree No. 07/2021/ND-CP. Through a wide range of active measures from both the government and the people, the multidimensional poverty rate has shown a downward trend, from 9.20 percent in 2016 to 4.80 percent in 2020 and 4.06 percent in 2024 [5]. Despite these positive developments, economic and social development strategies, particularly those aimed at reducing multidimensional poverty, still face many challenges, as more than two-thirds of the population live in rural areas where monetary and multidimensional poverty rates remain high [6]. In the context of increasing rural-to-urban migration and widening inequality between urban and rural areas, it is crucial for policymakers to have a correct understanding of these factors in order to implement effective measures to support and improve poverty conditions [7]. Improving living conditions in rural areas not only reduces poverty but also creates economic development opportunities for the entire region.

In addition to government poverty reduction programs and policies, such as enhancing human capital, providing vocational training, offering microfinance support, and improving public healthcare, identifying and implementing economic processes that have a positive impact on poverty reduction is essential. This mechanism not only stimulates the economy but also facilitates the allocation of resources to the poor, enabling them to access essential social services more effectively and thereby improving their living conditions [4,6].

Previous studies have shown that private investment increasingly contributes to economic development. Such investment not only generates employment and improves living standards but also enhances social welfare by diversifying goods and services at lower costs and improving the quality of public goods and basic services [8,9]. While some recent studies have indicated that private investment significantly contributes to poverty reduction, particularly multidimensional poverty reduction in Vietnam, there has been limited research clarifying whether private investment fosters multidimensional poverty reduction towards sustainability and through which mechanisms. Understanding this role is crucial for both researchers and policymakers [10].

Most existing studies have examined only the direct effects of private investment on monetary poverty, whereas comprehensive assessments of its spatial and temporal spillover effects on multidimensional poverty remain absent. Addressing this gap is crucial for understanding the sustainability of the relationship. To ensure reliable and robust findings, the study employs provincial panel data for Vietnam covering the period 2010–2024.

Spatial spillover effects are examined using spatial econometric models, including the Spatial Autoregressive Model (SAR), the Spatial Error Model (SEM), and most importantly, the Spatial Durbin Model (SDM), which allows the identification of both direct and indirect spatial linkages between private investment and multidimensional poverty. The results indicate that private investment not only reduces multidimensional poverty in a sustainable manner in the recipient province but also generates spillover effects on other provinces. These findings provide important policy implications for planners in designing and allocating industrial zones and economic centers, aiming not only to maximize efficiency in the investment-receiving province but also to promote multidimensional poverty reduction in neighboring provinces.

Temporal spillover effects are analyzed through the Pooled Mean Group (PMG) and the Common Correlated Effects Pooled (CCEP) estimators to evaluate the short-term and long-term impacts of private investment on multidimensional poverty. In addition, the Dynamic Common Correlated Effects Pooled (DCCEP) model is applied to capture the dynamic interrelationships among variables and further strengthen robustness. The results show that private investment exerts a positive influence on multidimensional poverty reduction in a sustainable way in both the short and long run. These findings provide significant policy implications for creating a favorable investment environment, enabling private investment not only to improve investment efficiency but also to foster sustainable economic development and multidimensional poverty reduction in both the short and long run.

The article is structured into five sections. The first section reviews the relevant literature on private investment and multidimensional poverty. The second section describes the data, variables, and research methodology. The third section presents and interprets the empirical results. The fourth section discusses the key findings and their implications. Finally, the fifth section concludes with policy recommendations aimed at strengthening private investment’s role in sustainable multidimensional poverty reduction in Vietnam.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Framework on the Impact of Private Investment on Multidimensional Poverty

- Economic Development Theory

The economic development theory, developed by economist Sir Arthur Lewis [11], provides a foundational framework for understanding the role of private investment in promoting poverty reduction, and it also implies that private investment contributes not only to reducing monetary poverty but also to promoting sustainable poverty alleviation in multiple dimensions. Lewis proposed a dual-sector model in which economies transition from traditional agricultural sectors to modern industrial sectors. According to this theory, investment in industry and infrastructure leads to economic growth, thereby generating employment opportunities and increasing income levels for people in the region, particularly the poor [12]. Recent studies also emphasize that structural inefficiencies in GDP composition may lock economies into a middle-income trap, thereby constraining both growth and poverty reduction towards sustainability [13]. This theory emphasizes the importance of transforming traditional economies into more productive and diversified economies through effective investments. It also highlights the way private investment in industrial and infrastructure projects creates additional employment, improves labor productivity, stimulates economic growth, and enables people to access basic social services at increasingly affordable prices. By examining the growing role of private sector investment in the economy, economists can gain a deeper understanding of how such investments contribute to the broader goal of multidimensional poverty reduction in a sustainable way [14,15].

- Human Capital Theory

This theory, developed by Gary Becker [16], focuses on investment in individual skills, education, and health to enhance productivity and potential. The central theme of this theory is that investment in human capital leads to higher individual incomes, thereby contributing to broader economic growth. In the context of increasing private investment, this theory is particularly relevant to investments in education, training, and healthcare. Such investments directly improve the skills and health of the workforce, which can, in turn, lead to higher productivity and a reduction in multidimensional poverty in a sustainable way [17].

Private enterprises frequently undertake initiatives including employee training programs, educational scholarships, and social welfare, thereby improving the human capital of both employees and the communities in which they operate [14,18]. By applying human capital theory to research, scholars can explore how private sector investments in human capital contribute to poverty alleviation, as well as to enhancing access to basic social services for vulnerable groups. This also improves labor market outcomes and increases individual income potential, thereby fostering inclusive economic growth [19].

- Social Responsibility Theory

The social responsibility theory is developed from the perspective that businesses exist not only to maximize profits for shareholders but also to contribute to social development and environmental protection [20]. This theory posits that private investment should actively address social issues such as poverty, education, and the environment through business activities and community engagement. In this context, social responsibility initiatives such as community health development programs, charitable donations, educational support, healthcare services, or improvements to local infrastructure can directly contribute to sustainable poverty alleviation in multiple dimensions [10,12].

Private investment activities should be guided by the principle of social responsibility, which entails not only generating economic value but also creating spillover effects on poverty dimensions through the provision of stable employment, capacity building for workers, and the promotion of access to basic services [19,21]. The study by Van Le et al. [10] indicates that private investment plays an essential role in improving income and living conditions, thereby significantly contributing to multidimensional poverty reduction in a sustainable way. Furthermore, multidimensional poverty reduction can also originate within enterprises themselves, as businesses adopt appropriate welfare policies that improve the lives of workers and support their families.

However, an alternative perspective on social responsibility in private investment arises in certain developing countries where legal and oversight systems remain limited. In such cases, businesses use social responsibility as a marketing tool to build a positive image, while in reality making no long-term commitment to the community [22]. Moreover, in the process of expanding private sector investment, there may be unintended consequences such as rising land prices and living costs, which displace the poor from their traditional living areas and make it more difficult for them to access basic social services [23]. Another limitation of the social responsibility theory is its tendency to focus on individual enterprises, without clearly reflecting the systemic relationship between the private sector and the national policy framework in the development process. While social responsibility is proactive in nature, it cannot substitute for the leading role of the State in ensuring equitable distribution of development opportunities for the poor. Therefore, many scholars have proposed integrating social responsibility theory with inclusive development theory in order to build effective public-private partnerships that both encourage the private sector to fulfill its social role and ensure transparency, accountability, and alignment with the national poverty reduction goals [24,25].

2.2. Transmission Channels of Private Investment

At present, investment capital flows are increasingly diversified, and private enterprises are also responsive to market changes, resulting in shifts from one locality to another or from one country to another [14]. Governments in many countries have adopted policies related to taxation and preferential support to attract private capital from within and outside the region, particularly from multinational corporations seeking investment opportunities. These are enterprises with advanced technology, strong production capacity, and established markets [26]. Other enterprises in the region can benefit both directly and indirectly. The direct effect occurs when technologically advanced enterprises with expertise, optimized inputs, and large consumer markets transfer technology or allow access to other enterprises. Meanwhile, other enterprises can adopt superior technologies through imitation, replication, or adaptation of advanced products and processes. This is referred to as the demonstration effect, which is generated by the emulation and replication of other enterprises’ professional skills, organizational methods, and marketing strategies. Such imitation enables other enterprises to achieve higher production efficiency and increased profitability, thereby generating positive spillovers that contribute to multidimensional poverty reduction towards sustainability [12,27].

The second channel is labor mobility. According to the study by Orlic et al. [28], there is horizontal spillover, and the comparison of labor costs per worker is used as a measure of the input factors in the production process. Private enterprises often optimize production processes. Therefore, reducing labor costs is one of the common measures applied to increase profitability. However, labor costs have two sides: some enterprises are willing to pay high wages to workers, which helps attract highly skilled and productive labor. Through this, enterprises can generate higher profits with significant contributions from this high-quality workforce, leading to enhanced competitiveness [8]. Thus, enterprises seeking to retain highly skilled workers must consider the dual nature of this issue; otherwise, a brain drain phenomenon may occur. In addition, many countries are currently implementing active measures to narrow the geographical gap between regions through a series of investments in infrastructure such as transportation and communication networks [29]. Consequently, many workers are willing to relocate to other regions in search of better job opportunities with higher incomes, which contributes to multidimensional poverty reduction in a sustainable way. Although the absorptive capacity is difficult to measure precisely, previous studies have used labor costs per worker, assuming that higher labor costs reflect higher skill levels [18,27]. This assumption implies that large private enterprises often have higher labor costs, provide technical skill development, and offer better opportunities to work in professional environments. This requires smaller enterprises to adopt policies that improve the working environment to enhance employee retention [30].

The third channel is competition. Orlic et al. [28] used the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index to assess the spillover effects of foreign private investment. However, Mathers and Shank [31] argue that the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index does not accurately reflect spillover effects because it is a static measure that cannot capture the process of knowledge diffusion, technological competition, or innovation. Furthermore, a high HHI may result from monopolies, leading to an inaccurate reflection of market concentration. Therefore, Rowley [32] suggests that the interaction between market concentration and horizontal spillovers would be a better indicator. Moreover, markets are constantly expanding, and competition levels are increasing between domestic and foreign enterprises, as well as between enterprises within the same industry, forcing firms to utilize resources more efficiently. This enhanced efficiency not only helps protect market share and profit margins in production and business but also creates positive spillover effects that foster The development of the private sector not only generates immediate localized impacts but also fosters spillover effects across both spatial and temporal dimensions in relation to poverty alleviation across multiple dimensions in a sustainable direction [27,30].

2.3. Channels of the Spillover Effects of Private Investment on Multidimensional Poverty

- Job Creation

In the context of countries moving toward an inclusive and sustainable growth model, private investment is increasingly considered an important driver that not only promotes economic growth but also directly contributes to job creation and sustainable poverty alleviation in multiple dimensions [21,23]. When private enterprises expand their production and business activities, labor demand increases, thereby opening up new employment opportunities for people, particularly low-income groups in rural and less developed economic areas. The spillover effects of private investment are not limited to recruitment positions but are also evident in supply chains, supporting service ecosystems, and satellite enterprises [18,27]. The formation of production linkages and value chains not only within a single locality but also in surrounding areas has generated additional jobs. At the same time, the movement of labor from the informal sector, where workers often lack contracts, insurance, and formal vocational training, to the formal sector with a more stable working environment, regulated labor conditions, and legally guaranteed labor rights, has taken place [30]. This movement not only improves job quality in terms of income but also enables workers to better access social welfare policies such as health insurance, social insurance, and training opportunities to enhance skills, thereby contributing to multidimensional poverty reduction in a sustainable way, particularly across non-income dimensions [31,33].

On the other hand, some argue that private investment creates very few jobs because the number of private enterprises is relatively small and wages are lower compared to self-employment or work in other economic sectors. Furthermore, the expansion of private enterprises does not always translate into job creation. Intense competition among large corporations, especially international conglomerates, can generate numerous challenges and may even lead to the bankruptcy of many enterprises, particularly small and medium-sized ones, which account for a large proportion in developing countries [30]. This exacerbates unemployment, especially among workers from poor households who often possess limited knowledge and skills, making it difficult to meet the requirements of large enterprises. Moreover, global economic shocks such as the Covid-19 pandemic have negatively affected enterprises, with many going bankrupt or downsizing their workforce, which not only impacts the enterprises themselves but also affects other businesses within the production chain and households [7]. Therefore, strict state management is needed to ensure healthy competition among enterprises and readiness to provide assistance when businesses face difficulties, especially during periods of economic recession, to prevent adverse social impacts, particularly on vulnerable groups in society [25].

- Improving Access to Basic Services

Private investment is increasingly demonstrating its important role in improving social services and reducing significant pressure on the state budget [9,12]. In the field of education, many private enterprises invest in schools or vocational training centers or cooperate with public schools to expand the scale and scope of training. With these efforts, the private sector not only helps to ease the burden on the public education system but also expands opportunities for children and youth in poor areas. For remote areas with difficult transportation conditions, through the development of information technology, private enterprises have actively invested in distance training programs [33,34]. This provides a valuable opportunity for children to access modern education and for adults to acquire new and advanced production knowledge, thereby better meeting the demands in the context of a deeply integrated economy [35]. In addition, private enterprises increasingly demonstrate their social responsibility through activities such as granting scholarships, sponsoring poor children and children living in remote areas, or investing in educational platforms that contribute to innovating learning methods. This is a valuable opportunity for children and poor people to have better access to modern education [36].

In the field of healthcare, the participation of the private sector in medical facilities, pharmaceutical supply chains, medical equipment, and macro health models helps to improve the efficiency of healthcare service delivery, especially in rural and remote areas [37]. Many private hospitals have invested in modern equipment and, combined with technological development, have successfully implemented telemedicine programs. Patients receive the best healthcare services without having to travel to central facilities [38]. Moreover, the participation of the private sector has broken monopolies in certain areas that previously only had state investment. Many countries allow patients receiving treatment at private hospitals to be covered by health insurance. This has provided people, especially the poor, with more options for healthcare services. Not only has service quality improved, but competition between public and private healthcare centers has also helped reduce service prices, giving the poor better access to quality healthcare at lower costs [39].

Beyond education and healthcare, private investment also promotes access to essential basic services such as clean water, affordable housing, and information infrastructure [40,41,42]. Many enterprises have adopted inclusive business models targeting low-income customer groups by providing innovative solutions such as solar energy, low-cost telecommunications, or social housing. With effective management capabilities and cost savings in production and business, governments in many countries are willing to use the budget to support private enterprises investing in socially oriented sectors. This has greatly contributed to further encouraging private sector investment in these fields, showing a clear spillover role of the private sector in improving quality of life and promoting social welfare [40].

Countries aim to protect human rights, especially those of vulnerable groups. Therefore, many countries use budget resources to support “social investment” projects through incentives such as tax exemptions and land support to help these groups better access basic services [3]. However, one downside of this approach is that private enterprises may exploit such policies instead of genuinely investing for community purposes. Furthermore, some projects, after receiving state support, fail to fulfill their commitments, change their intended use, and consequently deprive citizens of corresponding benefits [9]. Additionally, corruption between private enterprises and policy implementers undermines the selection of investors, preferential treatment, and service quality. Many social investment projects, after being licensed, have experienced delays, cost overruns, abandonment, or severe degradation in construction quality, leading to a significant waste of public funds. In some cases, certain “socialized” projects have even become a burden on the state, resulting in both the loss of public assets and the need for the state to allocate additional resources to remedy the consequences. In the long term, this phenomenon not only reduces the efficiency of budget use but also fails to improve the access of the poor and vulnerable groups to basic social services, making the sustainability of such policies fragile and less effective [39].

- Promoting the Development of Disadvantaged Regions and Reducing Regional Inequality

Previous studies have indicated that private investment in economically disadvantaged regions faces significant barriers, particularly in accessing capital. Relaxing financial constraints is therefore a key lever for promoting development in these areas. Investors seek projects that are both economically viable and socially beneficial, and such activities play a vital role in addressing market failures and narrowing the wealth gap between regions [14,41].

Porter [28] notes that disadvantaged areas often suffer from a lack of businesses and jobs, fueling a downward spiral of poverty and social problems such as illiteracy, school dropout, unemployment, drug abuse, and crime. Under these unfavorable conditions, business projects face locational disadvantages. Haitt and Sine [42] further show that violence and instability negatively affect project success and employment growth by altering risk perceptions, disrupting capital flows, and undermining long-term planning.

Private enterprises in disadvantaged areas, especially remote regions with large ethnic minority populations, encounter severe financial constraints [7]. Loan applications are often rejected, leaving them with smaller, less favorable credit. This restricts their ability to expand, recruit skilled employees, or upgrade production capacity, resulting in weak competitiveness. Consequently, many are forced to choose smaller and less profitable projects [41]. Yet, despite these obstacles, investors can achieve notable performance. Such enterprises generate more jobs compared to those in other regions because they primarily hire local residents. These jobs significantly ease economic hardship while promoting technical employment, which also accelerates the integration of ethnic minorities [30,31,34].

Private investment also reduces social inequality by creating quality jobs in disadvantaged areas. Employment opportunities particularly benefit young people, women, and migrants who are often excluded from the labor market. By offering stable and skilled work, private investment raises real incomes, reduces dependence on welfare, and fosters long-term development motivation [43]. In addition, effective businesses in disadvantaged areas stimulate local ecosystems of suppliers, services, transportation, and household consumption. They also reshape perceptions of the locality. People no longer view the area as risky, but rather as a place of opportunity. Successful enterprises become models, breaking down prejudices and encouraging other investors [32]. Local authorities then have stronger grounds to promote the area as a potential development zone rather than one neglected in a dynamic society. This is reinforced by advantages such as lower competition, reduced investment costs, and, in some cases, preferential treatment compared to other regions [31].

- Technology Diffusion and Innovation Advancement

Private investment not only provides capital and employment opportunities but also plays a central role in the diffusion of technology and effective business management models, thereby enhancing productivity, product quality, and competitiveness [8,27]. These changes are not confined to the economic dimension but also generate profound impacts on various aspects of society. When private enterprises take the lead in adopting new technologies, innovating production processes, or implementing modern management solutions, other enterprises, particularly small and medium-sized enterprises, which tend to learn, adapt, and improve, gain access to this knowledge and seek ways to apply it within their own operations [31]. Furthermore, this diffusion process occurs through multiple mechanisms such as market competition, supply chain linkages, technical cooperation, and labor mobility. As a result, production technologies are shared, and management methods as well as technical measures are widely absorbed and implemented [15]. This spillover effect has also had a significant influence on multidimensional poverty reduction, which can be observed through three aspects. First, increased productivity enables enterprises to expand their scale, creating jobs for workers, especially in localities with high unemployment rates. Second, the working environment is improved in various aspects such as labor skills, wages, and welfare conditions, forming a solid foundation for poor workers to not only secure stable employment but also enhance their access to essential social services such as education, healthcare, and occupational safety. Third, with increased production capacity and management organization, local enterprises can participate more deeply in value chains both within and beyond the region, creating opportunities for these enterprises to achieve deeper integration. Thus, private investment, through innovation and technology, not only drives the enterprises that invest but also spreads across the entire local economic system. When this diffusion is guided in the right direction, it can become an important channel to help the poor not only escape income poverty but also gain fuller access to essential services and living conditions, thereby contributing to sustainable multidimensional poverty reduction [21,34,36].

- Strengthening Linkages, Markets, and Product Consumption

Private investment generates significant spillover effects through strengthening value chain linkages, expanding markets, and improving product consumption capacity, particularly in rural areas and regions facing considerable difficulties [30,34]. Private enterprises, when engaging in the production, processing, and distribution of local products, often serve as intermediaries connecting small-scale producers with larger market systems, thereby helping the poor escape hardship. One of the most evident diffusion mechanisms is the formation and development of value chain linkages between enterprises and farming households. Through product off-take contracts, technical support, input assistance, and guarantees of stable output, private enterprises enable local people, especially poor households, to enhance production capacity, reduce market risks, and improve incomes. This form of linkage not only contributes to reducing income poverty but also creates conditions for people to improve access to science and technology, finance, and new production knowledge [41].

When private enterprises expand production, they also help improve commercial, logistics, and goods distribution infrastructure [19]. This contributes to shortening market distances and enabling local products to reach consumers or target export markets. Such contributions are particularly meaningful for people living in rural and mountainous areas, where multidimensional poverty is caused not only by low income but also by limited access to markets and distribution networks [25]. As markets expand and product value chains are upgraded, local people can actively choose appropriate production models, credit programs, and customers, thereby reducing dependence on intermediaries and avoiding price suppression [26]. This forms a foundation for enhancing the endogenous capacity of poor communities, helping them not only escape poverty but also free themselves from dependence on other actors, which is a core dimension of sustainable multidimensional poverty reduction [15,32]. In addition, with the growth of e-commerce platforms and the development of logistics systems, people, especially those living in remote and hard-to-reach areas, have been supported in overcoming mobility constraints. Through these platforms, local producers can directly sell to customers, and more customers can find quality products that meet their consumption needs.

- Innovation in Production Models and Entrepreneurship

In the process of the spillover effects of private investment on multidimensional poverty reduction, small and medium-sized private enterprises, particularly those pioneering in entrepreneurship, have played a central role in innovating production models and generating breakthroughs for the economy [43]. With flexible scale, rapid adaptability, and a tendency to apply digital technologies, this group of enterprises is often the origin of new technological initiatives that help reduce production costs and create products that better meet customer needs, especially those suited to low-income populations [30,44]. Through the development of innovative products such as improved agricultural tools, energy-saving technologies, low-cost medical solutions, and digital service platforms, these enterprises not only improve access to basic services but also expand production and consumption capacities for disadvantaged groups in society [6,45]. In parallel, the robust development of information technology, modern logistics systems, and e-commerce platforms such as Shopee, Lazada, and Facebook has opened new opportunities for the poor to access production and business knowledge and directly participate in the market. In remote and isolated areas, people can reach customers, learn business models, shorten distribution chains, and reduce transportation costs, which were previously significant barriers to small-scale production [46].

Private investment also creates a favorable environment to promote entrepreneurial activities from within poor communities, who are often marginalized in the economic development process. By learning practical production and business models, accessing microfinance, supply chains, skills training programs, and market linkages, the poor gradually develop the capacity to start businesses proactively [47]. This process cannot be separated from the supportive role of the Government and social organizations through practical policies and programs such as capital support, technical consulting, vocational training, tax incentives, and digital capacity building [43]. As a result, the poor are no longer merely beneficiaries of support policies but progressively transform into independent economic partners capable of creating value, developing livelihoods, and achieving self-reliance in the process of escaping poverty. From this perspective, private investment, when combined with production model innovation and entrepreneurship promotion, has played a crucial role in enhancing knowledge access, the right to participate in economic activities, and the capacity for economic autonomy in production and business among disadvantaged groups [41].

2.4. Impact of Private Investment on the Dimensions of Multidimensional Poverty

- Employment and Income

Private investment has long been recognized as a key driver of economic growth and job creation, particularly in developing and transitional economies [8,34]. The contribution of private investment to poverty reduction is clearly reflected in the creation of employment opportunities, improvement of income, and promotion of a more favorable investment environment. Numerous studies have confirmed that private investment, especially through small and medium-sized enterprises, as well as foreign private investment, has generated substantial new jobs and improved household living standards, particularly in rural areas and disadvantaged regions. With the growing development of domestic and foreign private enterprises, an important contribution has been made to rural labor restructuring and the enhancement of poverty alleviation opportunities for many population groups [43,47].

However, the relationship between private investment and poverty reduction is not always linear or guaranteed. Economic growth is essential for every country, but it does not necessarily translate into benefits for the poor unless it is guided and accompanied by government intervention [23]. In some countries, especially where the number of private enterprises is small, their scale is limited, and their capacity is weak, job creation is low, wages are inadequate, protection is lacking, and sustainability is not ensured. Moreover, fierce competition from large corporations, particularly multinational enterprises, can put pressure on domestic small and medium-sized enterprises, leading to bankruptcy, job losses, and increased vulnerability of local workers [48].

In addition, in the context of rapid technological innovation and digital transformation, many private enterprises are actively applying scientific and technological advances to optimize production processes, increase productivity, and reduce costs [41]. While this enhances competitiveness, the downside of automation is the reduced demand for manual labor, particularly in labor-intensive sectors such as textiles, agriculture, and food processing. Many studies have pointed out that automation can replace a significant number of low-skilled workers, whose livelihoods are predominantly dependent on such jobs in developing countries [34].

Furthermore, the application of advanced technology requires the workforce to possess certain technical qualifications and skills. However, the majority of poor workers often have low educational attainment, lack skills, and have limited access to vocational training, making them more likely to be excluded from the labor market when enterprises change their production models. This situation not only increases the risk of prolonged unemployment but also pushes vulnerable labor groups into a vicious cycle of poverty, unemployment, and returning to poverty. The widening gap between workers who can adapt to new technologies and those excluded from the development process is a major cause of inequality and a factor that diminishes the spillover effects of economic growth [49].

When economic growth benefits the poor little or even excludes them, this becomes a major contradiction that must be carefully addressed in order to design policies that aim for sustainable and equitable development. Therefore, in some countries, although private investment has made a positive contribution to the process of economic transformation, there still exist structural gaps such as the lack of an effective vocational training system, weak protection of workers’ rights, and inadequate mechanisms for monitoring job quality. As a result, the regulatory role of the government is essential to ensure that private investment not only promotes economic growth but also genuinely contributes to poverty reduction [9,35].

- Access to Information

The development of the private sector, particularly in the field of information and communication technology, has been recognized as one of the key factors contributing to narrowing the information gap, which is an important dimension in promoting access to development opportunities, especially for poor and vulnerable groups [46]. Through investment in digital infrastructure, telecommunications services, digital finance, and e-commerce platforms, the private sector has significantly expanded the information space, reduced transaction costs, and created opportunities for people to access markets, acquire vocational training, understand policies, and utilize essential public services. Technologies such as mobile money, digital applications, and online learning platforms have partially helped people in remote and rural areas overcome traditional barriers to accessing modern knowledge [49].

However, this process does not generate uniform effects across all social groups. Although mobile technology and the internet are expected to democratize information access, practical experience shows that technology alone does not inherently bring equality without accompanying supportive conditions [50]. Ownership of devices or internet connections is only a necessary condition but not sufficient for the poor to be truly empowered with information. A considerable portion of poor individuals, women, persons with disabilities, or those living in remote areas face a double barrier: lacking an educational foundation and lacking the skills to process and effectively utilize information [36].

Access to technology, if not accompanied by training and guidance, cannot improve living conditions and may instead create a sense of helplessness, dependency, or surveillance. In rural India, many women express reluctance to use phones to search for information due to a lack of technical support or fear of being monitored by family members [51]. In the United Kingdom, although technology has been introduced into advisory systems to reduce the stigma of seeking help, long-term effectiveness still requires personalized guidance or accompanying psychological support [52].

Moreover, many private enterprises investing in technology tend to concentrate on high-profit areas such as urban centers, while remote areas where the poor reside continue to be left behind. This widens the information gap between regions and social classes. The development of information technology has unintentionally created “information herds,” where poor users access distorted content, depend on intermediaries, or are driven by consumer manipulation instead of having the capacity to control information [3,6,36].

Global initiatives such as Global Libraries (Gates Foundation, IFLA, University of Washington) and research by Cordes and Marinova [53] have also emphasized that access to information is not only a right but also a prerequisite for achieving sustainable development. However, these initiatives also acknowledge an important reality: without investment in the skills and capacity to use information, even with internet access, the poor may still remain in a state of “information poverty.” Therefore, in the context of a rapidly developing digital society, balancing market capacity with social responsibility and combining technological innovation with investment in human development will be a decisive factor in ensuring that information does not become a form of privilege but remains a universal right for all, especially for disadvantaged groups [50,54].

- Housing

In developing countries, governments place significant emphasis on the issue of providing housing for the poor. Private investors often possess substantial financial resources and efficient management capabilities, and by supplying affordable housing, they help low-income populations stabilize their lives. This not only reduces the burden on the state budget but also allows the private sector to fulfill its social responsibility toward disadvantaged groups who require assistance not only from the government but also from the broader community [23]. In addition, public–private partnerships in social housing projects encounter numerous difficulties during implementation, including administrative procedures, limitations in public funding, work allocation issues, or inequitable risk sharing, all of which weaken the durability of such collaborations [55]. Another reason explaining this challenge is the rising demand for housing, while government policies have not responded in a timely manner to practical needs such as reducing interest rates for social housing projects or ensuring equitable housing allocation, both of which remain pressing issues, especially in large urban areas [23]. These are places where many low-income workers from different regions come to live, where urbanization is accelerating, and where urban development plans fail to keep pace. This situation not only generates instability in the lives of low-income workers but also creates broader social instability, including potential social evils, the emergence of slums that may harbor disease, and living conditions for residents and children that fail to meet basic standards [56]. Therefore, urgent and sustainable solutions need to be implemented. Encouraging private investors to participate in this sector is among the effective measures, as it benefits both the population and society as a whole. However, to implement this policy effectively, there must be clear legal regulations, embedded within a proper legal framework, in order to prevent the exploitation of legal loopholes that could harm the state budget, undermine social improvement objectives, and, in particular, widen the gap between social classes and erode public trust in government [25,39,57].

- Clean Water and Sanitation

In recent years, the growing involvement of the private sector in the provision of clean water and sanitation services has brought about significant changes in many developing countries [57]. Through its financial capacity, technological resources, and operational efficiency, the private sector has contributed to improving service quality and expanding coverage to previously underserved areas such as rural regions and remote communities. Public service socialization models in Chile and the Philippines have demonstrated the positive potential of private investment by modernizing water supply and drainage systems and reducing the financial burden on public budgets [58,59].

However, alongside these benefits, this model has also revealed several shortcomings, particularly the imbalance between investment in clean water and sanitation, as well as the risk of natural monopoly [60]. Investors often focus on clean water supply, which is an attractive field due to high demand and strong profitability. In some developing countries, rural residents have had to pay substantial amounts for clean water. Conversely, investors are generally reluctant to invest in sanitation services such as wastewater collection and treatment because of high costs, low demand, and slow capital recovery, making it difficult for the poor to gain access [57].

A pressing concern arises in contexts lacking a legal framework to mitigate corruption. This leads to public–private partnership contracts being exploited to maximize profits rather than serve social welfare objectives [61]. In some countries, private companies granted control over water systems have no responsibility to invest in drainage and waste treatment infrastructure, resulting in imbalanced investment and inequality in service access. In certain cases, officials may abuse their authority to influence project planning in favor of familiar providers, distorting investment goals [62]. When corruption is widespread, investors tend to focus solely on clean water supply, a sector with quick returns, while avoiding sanitation, which requires large investments and offers low profits [60,61,63].

Moreover, water is a vital resource in life, and when a single company controls the entire water system in a locality, it can lead to unreasonable price increases, poor service quality, and a lack of alternative choices for residents. Evidence from several African cities has shown that after privatization, water prices surged while quality did not improve, forcing residents, especially the poor, to rely on unsafe water or cut essential expenditures [40]. To prevent negative impacts from the increasing dominance of private investment in the water and sanitation sector, many governments have had to establish independent monitoring systems to regulate prices, quality, and service coverage, thereby safeguarding the right to clean water for all citizens, particularly the poor and vulnerable groups. Clean water is not only a basic need but also a human right recognized by the United Nations [58]. Without appropriate regulatory policies and effective anti-corruption measures, private investment may unintentionally deepen inequality, exacerbate social exclusion, and worsen community health conditions rather than reduce disparities [39].

- Healthcare

There is increasing attention to the role of the private sector in providing healthcare services in low- and middle-income countries. It has become an important source of care for all groups in society, including the poorest and most vulnerable [38]. With deeper involvement, private actors are viewed as offering more accessible and affordable services that respond to diverse needs and preferences. In many cases, they remain crucial providers for disadvantaged communities [64].

Private healthcare is delivered through private hospitals, clinics operated by nongovernmental organizations, informal providers, and even traditional healers in remote areas [65]. The sector occupies a central position in many health systems, delivering a wide range of goods and services in developing countries. It is also seen as a strategic partner in introducing new medical products of good quality and suitable for different social groups. Innovations such as telemedicine and digital health further highlight its potential to extend coverage to populations that are otherwise difficult to reach [39].

Yet the spillover effects of private healthcare investment are context dependent, varying with development level, economic structure, and rural-urban setting. While private involvement improves access, concerns remain about quality and efficiency. Studies show that services offered by private facilities often fall short in technical standards. For example, treatment of sexually transmitted infections, tuberculosis, and malaria has revealed shortcomings in diagnosis and prescribing practices [37]. These risks underline the trade off between accessibility and patient safety. Moreover, the public sector also struggles with weak technical quality, showing that reforms must target systemic weaknesses in both sectors [25,38].

Governments and nongovernmental organizations increasingly collaborate with private providers through social marketing, franchising, training, and regulation. However, such cooperation must be carefully adapted to local contexts to avoid uneven quality or widening disparities between rural and urban areas. Profit-driven approaches may restrict access for vulnerable groups, underscoring the need for stronger oversight and clear institutional frameworks. Governments must ensure that all stakeholders, both public and private, respect the right to healthcare and align with national health goals. Achieving this requires stronger institutions, effective monitoring, and broad participation. Under these conditions, private investment can complement public provision and contribute sustainably to universal health coverage [17,61].

- Education

In recent decades, a strong wave of private investment in education has emerged in many developing countries, driven by the need to expand access and the limitations of public systems in meeting growing demand [35]. Several studies have shown that low-fee private schools can play an important complementary role in providing educational services to the poor, particularly where the state has yet to fully cover public provision [36]. With flexible management and low operating expenses, these schools can determine salary levels, hire young teachers, or pay on an hourly basis. Their streamlined structures, free from cumbersome bureaucracy, often receive support from governments, corporate sponsors, or nonprofit organizations. This enables them to charge low tuition fees, thereby improving access to basic education for low-income households [56]. Moreover, private investment in vocational training and skills development has been shown to increase employment opportunities and income for the poor, especially youth and women in disadvantaged regions. The flexibility in program design, stronger labor market linkages, and scholarship or subsidy schemes allow many to pursue education aligned with personal development needs [66]. However, the spillover effects of private investment on education are nuanced and depend on the level of development, type of economy, and rural–urban context. Alongside positive contributions, concerns persist. The quality of private education varies widely: due to cost-cutting pressures, schools often rely on makeshift facilities and lack adequate resources such as books, equipment, and laboratories. Teachers are frequently inexperienced and underpaid, leading to high turnover, weak motivation, and limited professional development [67]. In many countries, regulatory oversight remains lax, resulting in poor supervision and perpetuating low-quality instruction. This cycle undermines the potential of education to sustainably lift the poor out of poverty. Furthermore, the coexistence of elite private, low-cost private, and public schools can exacerbate social stratification, forcing disadvantaged households into lower-quality institutions [68]. Profit motives also encourage student selection, often favoring those with stronger academic performance and better economic conditions, thereby restricting access for marginalized groups. Consequently, private schools do not automatically enhance education quality unless integrated within a robust policy framework with clear monitoring and evaluation mechanisms [36]. A lack of coordination between public and private actors, unhealthy competition, and information asymmetries further limit effective resource allocation. Yet, when effectively regulated and supported, private investment can reduce social inequality by creating quality jobs in education and related sectors, raising incomes, reducing welfare dependence, and fostering long-term development [43]. In addition, successful educational enterprises can stimulate local ecosystems of suppliers, services, and household consumption, while shifting perceptions of disadvantaged areas from high-risk to areas of opportunity. This demonstration effect attracts new investors, encourages more favorable media portrayals, and provides local governments with stronger grounds to promote these areas as potential development zones [32]. Policymakers must therefore consider both opportunities and risks, recognizing that the broader impact of private investment in education is highly context-specific and depends on how effectively it is embedded within national development strategies [31,50].

3. Methodology and Data

3.1. Research Objective, Research Questions, Hypotheses

The main objective of this study is to assess whether private investment (PI) contributes to the reduction of multidimensional poverty (MP) in Vietnam in a sustainable way, while also accounting for spatial and temporal spillover effects. This means that private investment is expected to reduce poverty not only in the provinces where it occurs but also in neighboring regions, with effects observable in both the short and long term. The analysis focuses on private investment as the key explanatory variable, while the PAPI index, GRDP per capita (GRDPpc), literacy rate (LI), and urbanization rate (UR) are incorporated as control variables to ensure robust estimation.

This study is guided by the following research questions:

Does private investment (PI) contribute to multidimensional poverty (MP) reduction not only within the provinces where it takes place but also through spatial spillover effects in neighboring provinces?

Are the effects of private investment on multidimensional poverty reduction sustained over time, reflecting temporal spillover effects in both the short and long term?

Based on these research questions, the study proposes the following hypotheses:

H1.

Private investment (PI) has a significant impact on reducing multidimensional poverty (MP) not only within the provinces where it occurs but also through spatial spillover effects in neighboring provinces.

H2.

The effects of private investment on multidimensional poverty reduction are sustained over time, indicating the presence of temporal spillover effects in both the short and long term.

3.2. Data

Our study focuses on assessing the spillover effects of private investment on multidimensional poverty in Vietnam, using provincial-level data from 63 provinces and cities during the period 2010–2024. The authors compiled these data to develop a comprehensive dataset that serves the research objectives (Table 1).

Table 1.

Variables, expectations, and their sources.

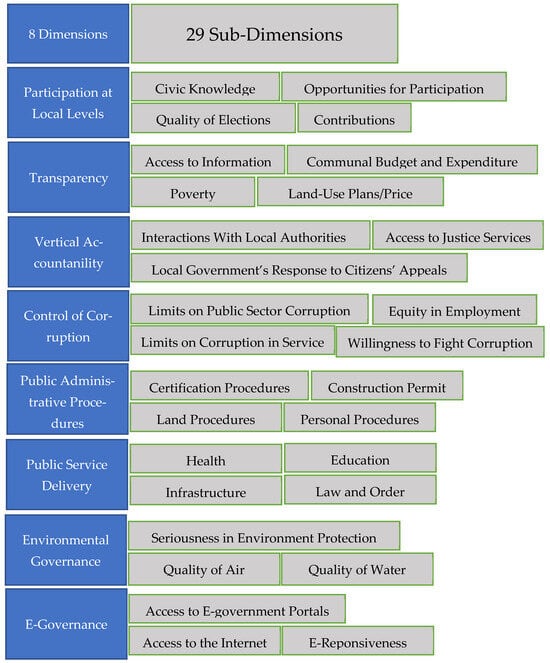

As official data on the provincial multidimensional poverty rate have only been published since 2016, the study calculates the multidimensional poverty index for 2010–2016 based on the methodology stipulated in Decision No. 59/2015/QĐ-TTg of the Prime Minister. In this calculation, the income poverty dimension is determined in accordance with the poverty line defined in Decision No. 09/2011/QĐ-TTg, while the non-income deprivation dimensions (such as access to healthcare, education, housing, and information) are compiled and processed from the Vietnam Household Living Standards Survey (VHLSS) conducted by the General Statistics Office. Second, to capture the quality of provincial governance, this study employs the Provincial Governance and Public Administration Performance Index (PAPI), developed by UNDP and the Centre for Community Support and Development Studies (CECODES). The index consists of eight main dimensions and twenty-nine sub-dimensions (Appendix A). The PAPI composite score is derived by aggregating standardized indicators, with weights assigned to each dimension based on regression estimates of their relative contribution to citizens’ satisfaction with local governance. All indicators are normalized on a 1–100 scale using observed national minimum and maximum thresholds, where higher scores reflect better governance quality.

3.3. Methodology

- Cross-Sectional Dependence (CSD) Test

In panel data research, particularly when analyzing socio-economic factors across multiple provinces or regions, cross-sectional dependence (CSD) often arises as a result of common shocks or spillover effects among observational units. If unaddressed, CSD may result in biased estimates. Therefore, prior to conducting subsequent analyses, this study employs the CD test proposed by Pesaran (2004) [70] and later extended in Pesaran (2015) [71] to assess the presence of CSD.

The CD test statistic is expressed as follows (Equation (1)):

where:

N: Number of cross-sectional units.

T: Number of time-series observations.

: Correlation coefficient of the residuals between units i and j.

The null hypothesis states that there is no cross-sectional dependence among the units, while the alternative hypothesis indicates the presence of cross-sectional dependence. Rejection of at the chosen level of statistical significance implies the existence of cross-sectional dependence, in which case second-generation estimators should be applied to ensure the consistency and unbiasedness of the results.

- Slope Heterogeneity Test

In panel data research, an important issue is the testing of slope heterogeneity (SH test). This test addresses the phenomenon in which the slope coefficients in the regression function differ across cross-sectional units, which may result from differences in economic scale and development levels among provinces or regions within a panel dataset. Pesaran and Yamagata [72] proposed the SH test to examine the homogeneity of slope coefficients, expressed as follows (Equations (2) and (3)):

where:

N: Number of cross-sectional units.

T: Number of time-series observations.

k: Number of explanatory variables.

: Swamy’s statistic measuring the degree of dispersion between individual slope estimates and the pooled slope coefficient.

However, according to Blomquist and Westerlund, the SH test is not applicable in cases involving heteroskedasticity and serial correlation in the error terms. Therefore, Blomquist and Westerlund [73] proposed the SH test statistic as follows (Equation (4)):

where:

where denotes the OLS estimates. In this study, to ensure the reliability of the results, the authors applied both slope homogeneity testing methods.

- Panel Unit Root Test

In the presence of cross-sectional dependency, to avoid estimation bias and accurately capture the stationarity properties of the variables, this study employs second-generation panel unit root tests, specifically the CADF and CIPS tests developed by Pesaran (2007) [74].

The CADF test statistic is calculated as follows (Equation (7)):

where:

: Observed variable of unit iii at time t.

: Cross-sectional mean of Z at time t.

p: Lag order.

: Estimated parameters.

: Random error term.

Based on the CADF statistics for each unit, the CIPS test is computed as follows Equation (8):

For both the CADF and CIPS tests, the null hypothesis states that the series contains a unit root (non-stationary).

- Panel Cointegration Test

In this study, to examine the existence of a cointegration relationship in the panel dataset, the authors first apply three first-generation tests, namely Pedroni (1999) [75], Pedroni (2004) [76], and Kao (1999) [77], which are expressed as follows Equation (9):

where: is residual term, and are parameters allowed to vary across cross-sectional units, is vector of long-run coefficients. From this model, Pedroni develops seven cointegration test statistics based on the unit root properties of the residuals, consisting of four panel (within-dimension) statistics and three group (between-dimension) statistics.

In contrast, the Kao (1999) [77] test assumes that the slope coefficients are homogeneous across units, with the model specified as follows Equation (10):

The residual term obtained from the model is then incorporated into the ADF equation in the following form Equation (11).

To test the null hypothesis : no cointegration.

However, a common limitation of both the Pedroni and Kao tests is the assumption that cross-sectional units are independent of one another. In the presence of cross-sectional dependence, which is frequently observed in the context of globalization and economic integration, these tests may produce biased and potentially misleading results. To address this issue, Westerlund [78] proposed a cointegration test based on the error-correction model, specifically designed to handle panel data more effectively Equation (12).

Westerlund provides four test statistics, namely Equations (13) to (16).

The statistics test for the presence of cointegration in one or a few units within the panel, while test for cointegration across the entire panel.

- The Spatial Econometrics Model

Moran’s I index: Moran’s I is a statistical measure used to assess spatial autocorrelation, indicating the extent to which nearby locations exhibit greater similarity compared to more distant ones. It is commonly employed in the social and environmental sciences to analyze the spatial distribution of natural resources and urban development. The Moran’s I statistic is computed as follows Equation (17).

where, I: Moran’s I statistic, n: the number of observations, the variable of interest, the elements of the spatial weights matrix.

There are three commonly used spatial econometric models, including the Spatial Autoregressive (SAR) model, the Spatial Error Model (SEM), and the Spatial Durbin Model (SDM). According to Elhorst [79], the SAR model is applied when the dependent variable (EF) exhibits spatial autocorrelation, whereas the SEM model is appropriate when spatial dependence is found in the error terms. The SDM is employed when spatial correlation is present in both the dependent and independent variables.

To determine the most appropriate spatial model, this study utilizes the null hypothesis : θ = 0 and the alternative hypothesis : θ ≠ 0 to compare the SDM and SAR models. If the result of the Lagrange Multiplier (LM) test yields a p-value less than 0.05, the null hypothesis is rejected, indicating that the SDM model provides a better fit than the SAR model.

Similarly, the null hypothesis : ρ = 0 and θ = 0 and the alternative hypothesis : ρ ≠ 0 and θ ≠ 0 are employed to compare the SDM and SEM models. If is rejected, it suggests that the Spatial Durbin Model offers the most appropriate specification for the data Equation (18).

In this context, represents the dependent variable, signifies the independent variables. β and W represent the coefficient vector for the independent variables and the spatial matrix, respectively. ε is an n × 1 vector of error terms, typically assumed to be i.i.d. with zero mean and constant variance.

The spatial weight matrix is denoted as W, where each element, wij, represents the spatial weight between location i and location j among n locations. In this study, we utilized the following matrices.

The contiguity matrix (): If is adjacent to , = 1; otherwise = 0 (Equation (19)).

The inverse distance matrix (): We employ to represent the distance between the capitals of provinces (Equation (20)).

In this context, and denotes the north latitude of and , respectively. A similar rule is applied for and . R is equal to 6378.137 km. The mathematical constant π(pi) is approximately equal to 3.14159. can take on one of the following two values (Equation (21)).

* Pooled Mean Group (PMG) Model

The PMG (Pooled Mean Group) model, proposed by Pesaran, Shin, and Smith [80], is an estimation method applied to dynamic panel data, allowing for the simultaneous analysis of both short-run and long-run effects among variables within the framework of the ARDL (Autoregressive Distributed Lag) model. Incorporating lags of both the dependent and independent variables into the model helps mitigate the impact of endogeneity, particularly that arising from bidirectional causality or time-invariant omitted variables.

The general form of the ARDL model is presented as follows Equation (22):

where:

: Dependent variable.

Set of explanatory variables.

I: Spatial unit (province/city).

T: Time period.

: Unobserved fixed effect.

: Random error term.

The ARDL model is re-parameterized into an error correction model (ECM) form to clearly distinguish between short-run and long-run effects Equation (23).

where:

: Speed of adjustment coefficient toward the long-run equilibrium, expected to be negative.

: Vector of long-run coefficients.

: Short-run coefficients.

The PMG model allows for heterogeneity across cross-sectional units in the short-run coefficients, including the intercepts, dynamic coefficients, and the speed of adjustment. However, it imposes homogeneity on the long-run coefficients across units. This assumption reflects the view that, in the long run, provinces or regions may converge to the same fundamental economic relationship, while in the short run they remain subject to specific influences such as local policies, economic shocks, or differences in initial conditions.

- Common Correlated Effects Pooled Estimator (CCEP)

To control for the influence of unobserved common factors in panel data models, Pesaran (2006) [81] proposed the Common Correlated Effects Pooled (CCEP) estimator. This approach addresses the issue of cross-sectional dependence among units in the panel by incorporating the cross-sectional averages of the variables as proxies for the unobserved common factors. The model assumes slope homogeneity across units.

The general specification of the CCEP model is as follows Equation (24):

where:

: Dependent variable.

: Independent variable.

: Cross-sectional mean of the dependent variable.

: Cross-sectional mean of the independent variable.

: Long-run slope coefficient, assumed to be homogeneous across units iii.

, : Coefficients of the cross-sectional mean components.

: Spatial (location-specific) fixed effect.

: Random error term.

- Dynamic Common Correlated Effects Pooled Estimator (DCCEP)

The DCCEP model, developed by Chudik and Pesaran [82], is an extension of Pesaran’s (2006) [81] original CCEP method. It is specifically designed for application to dynamic panel data and effectively addresses cross-sectional dependence among spatial units. This approach is particularly suitable for panel ARDL models that incorporate both dynamic components and unobserved common factors. The DCCEP assumes slope homogeneity, whereby provinces or regions can converge to a common long-run structural relationship, and it is often used as a robustness check.

The model structure is presented as follows Equation (25):

where:

: Dependent variable.

: Vector of independent variables.

: Individual (unit-specific) effect for each spatial unit.

: Cross-sectional mean of the variables in the model.

: Lag order of the cross-sectional mean included in the model.

The long-run coefficient for unit iii is calculated as follows Equation (26).

From this, the long-run estimate for the entire sample is calculated as the average, as follows (Equation (27)):

4. Empirical Results and Discussion

4.1. Private Investment in Vietnam

Private investment plays an important role in Vietnam’s economy as one of the main drivers of growth, job creation, and enhancement of the country’s competitiveness. Consequently, the Government of Vietnam has made significant efforts to implement effective measures to attract and efficiently utilize this source of capital [9]. Specifically, Vietnam has introduced a range of effective policies, most notably Resolution No. 14-NQ/TW (2002) and Resolution No. 10-NQ/TW (2017) of the Party Central Committee, as well as Resolution No. 68-NQ/TW of the Politburo. These resolutions focus on reforming mechanisms, policies, incentives, and conditions for the development of the private economy, with the aim of transforming this sector into a key driver of the national economy. In the current context, the government affirms that the private economy is a pioneering force in promoting science and technology, innovation, and digital transformation. This forms an important legal basis for Vietnam to implement programs that support and encourage private investment.

In addition, the Government of Vietnam has consistently paid attention to and implemented administrative procedure reforms and innovations in the investment mechanism to create the most favorable conditions for private investors. Notably, the Law on Enterprises has been continuously revised in 1990, 1999, 2004, 2014, and 2020. Likewise, the Law on Investment has undergone policy changes in 2004, 2014, and 2020 to align with current circumstances.

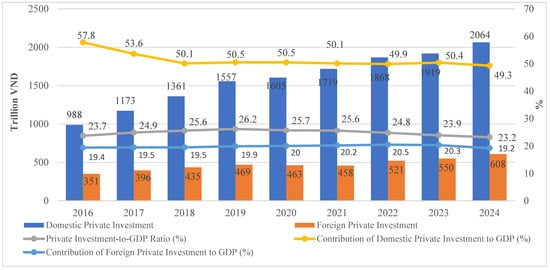

Both domestic and foreign private investment have shown steady growth, underscoring their vital role in Vietnam’s economy (Figure 1). At the same time, private enterprises have become key drivers of export expansion, particularly in high-value products such as electronics, computers, and machinery. In 2024, private sector exports in key categories, including electronics, telephones, textiles, and footwear, accounted for more than 94% of total export value [5]. These results reflect improvements in the investment climate and trade promotion while also underscoring the expanding role of the private sector in global supply chains [83,84].

Figure 1.

Private Investment in Vietnam.

Complementing this domestic dynamism, foreign private investment from multinational corporations has been essential in sustaining production and exports. Yet capital inflows have grown only modestly due to administrative bottlenecks, infrastructure gaps, and the limited effectiveness of investment incentives [10,83]. Most preferential policies continue to rely on income tax reductions rather than cost-based measures, while certain provisions such as Article 18 of the 2020 Investment Law remain inconsistent with state budget regulations, complicating implementation in practice. At the same time, many foreign enterprises are increasingly demanding support that directly reduces production costs, such as subsidies for energy, logistics, and infrastructure, instead of traditional tax or land-rent exemptions. This shift in investor expectations highlights the growing gap between Vietnam’s policy framework and the evolving needs of global investors, thereby constraining the country’s ability to attract higher-quality foreign private capital. In addition, Vietnam continues to confront the “low value-added” trap in foreign investment, reflected in weak linkages with the domestic economy and limited gains in efficiency, productivity, and workforce skills. Investment remains concentrated in labor-intensive sectors that compete primarily on cost, treating labor more as an expense than as a strategic resource. To overcome these constraints, Vietnam will need to adopt a more synchronized set of measures aimed at both attracting foreign private investment and improving the quality and efficiency of capital utilization.

Taken together, private investment has become an increasingly important driver of Vietnam’s economic growth and employment creation. Its role in multidimensional poverty reduction is visible, but the impacts are uneven across different welfare dimensions. While it helps raise incomes and generate jobs, its effects on improving education, healthcare, housing, and broader well-being remain less pronounced. Strengthening the orientation and quality of private investment will therefore be essential to maximize its contribution to multidimensional poverty reduction in a sustainable manner.

4.2. Multidimensional Poverty in Vietnam

Eradicating hunger and reducing poverty have always been top priorities of Vietnam. The poverty standard serves as the measurement criterion to determine eligibility for poverty reduction policies, ensuring fairness in implementation [7]. Prior to 2015, poverty was mainly assessed by household income relative to the official poverty line. While this approach helped many households escape poverty, their income often remained close to the threshold, leading to a high risk of falling back into poverty. To address this limitation, in November 2015, the Government of Vietnam promulgated Decision No. 59/2015/QĐ-TTg, which officially introduced a multidimensional poverty framework for the period 2016–2020. Under this framework, a rural household was considered multidimensionally poor if (i) its per capita income was 700,000 VND per month or less; or (ii) its income was between 700,000 and 1,000,000 VND per month and it was deprived in at least three out of ten basic service indicators. An urban household was classified as multidimensionally poor if (i) its per capita income was 900,000 VND per month or less; or (ii) its income was between 900,000 and 1,300,000 VND per month and it was deprived in at least three indicators. These ten indicators covered five basic dimensions: (i) access to health services, (ii) health insurance, (iii) adults’ educational attainment, (iv) school attendance of children, (v) housing quality, (vi) average housing area per capita, (vii) access to clean water, (viii) hygienic latrines and toilets, (ix) use of telecommunication services, and (x) ownership of information assets.

In the period 2021–2025, the Government of Vietnam promulgated Decree No. 07/2021/NĐ-CP, which stipulates the multidimensional poverty standard. Under this framework, the identification of multidimensionally poor households is based on two main criteria. First, the income criterion defines poverty lines at 1,500,000 VND per person per month in rural areas and 2,000,000 VND per person per month in urban areas. Second, households are evaluated by their deprivation in basic social services, measured across six dimensions with twelve indicators: (i) employment status, (ii) household dependency ratio, (iii) nutrition, (iv) health insurance, (v) adults’ educational attainment, (vi) school attendance of children, (vii) housing quality, (viii) average housing area per capita, (ix) access to domestic water, (x) hygienic toilets, (xi) use of telecommunication services, and (xii) means of accessing information. According to the Decree, a household is officially classified as multidimensionally poor if its income falls below the respective threshold and it is simultaneously deprived in at least three of these twelve indicators.

This shows that Vietnam is gradually transforming its approach to measuring poverty from single-dimensional to multidimensional [15]. The National Target Program on Sustainable Poverty Reduction for the period 2021–2025 has set the overall objective of reducing multidimensional poverty in an inclusive and sustainable manner, limiting poverty relapse and the emergence of new poverty cases, and supporting the poor and poor households to rise above the minimum living standard, to access basic social services according to the national multidimensional poverty standard, and to improve the quality of life [85].