Sustainable Banking Through Corporate Social Responsibility: Financial and Emotional Pathways of Customer Perceptions—Evidence from Ankara, the Capital of Turkey

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Sustainability and Sustainable Banking

2.2. Corporate Social Responsibility

- CSR is “the overall relationship of the corporation with all of its stakeholders. These include customers, employees, communities, owners/investors, government, suppliers, and competitors. Elements of social responsibility include investment in community outreach, employee relations, creation and maintenance of employment, environmental stewardship and financial performance” [32] (p. 7).

- CSR is “a concept whereby companies integrate social and environmental concerns in their business operations and in their interaction with their stakeholders on a voluntary basis” [68] (p. 8).

- CSR refers to “a set of management practices aimed at reducing the negative impacts of a company’s operations on society while enhancing their positive contributions” [69] (p. 117).

- CSR is “the commitment of business to contribute to sustainable economic development, working with employees, their families, the local community and society at large to improve their quality of life” [70] (p. 2).

- CSR entails “ethical and transparent business practices that prioritize respect for employees, communities, and the environment, ultimately fostering sustainable business success” [71] (p. 2).

- CSR is defined as “context-specific organizational actions and policies that take into account stakeholders’ expectations and the triple bottom line of economic, social, and environmental performance” [72] (p. 933).

- CSR has evolved “from simple philanthropy to a more theoretical concept with a new corporate philosophy that takes all the interests of all stakeholders into consideration” [73] (p. 2).

- Shareholders: This dimension highlights the firm’s commitment to protecting shareholders’ interests. To that end, it seeks to increase its profits and exercise cost control. Additionally, the firm aims to ensure organizational sustainability by maintaining long-term continuity in its operations.

- Employees: This dimension reflects how the firm treats its employees impartially, ensuring there is no discrimination or exploitation. It provides a pleasant and safe working environment, pays fair wages, and offers training and career development opportunities.

- A general dimension concerning legal and ethical issues: This dimension emphasizes that the firm consistently complies with legal rules and regulations. It strives to fulfill its obligations toward all stakeholders (e.g., customers, suppliers, and shareholders) and never compromises on ethical principles.

- Customers: In this dimension, customer satisfaction is an indicator for improving the firm’s product marketing. The firm seeks to understand customer needs, acts honestly, develops procedures to address complaints, and ensures that employees provide customers with complete and accurate product information.

- Society: This dimension demonstrates that the firm’s role extends beyond generating economic benefits. Accordingly, the firm aims to enhance societal welfare by addressing social issues. It allocates a portion of its budget to social projects targeting disadvantaged groups, makes charitable contributions, supports cultural and social events, and respects and protects the natural environment.

2.3. Customer Emotions

2.4. Corporate Social Responsibility and Customer Emotions

2.5. Financial Performance

2.6. Corporate Social Responsibility and Financial Performance

2.7. Financial Performance and Customer Emotions

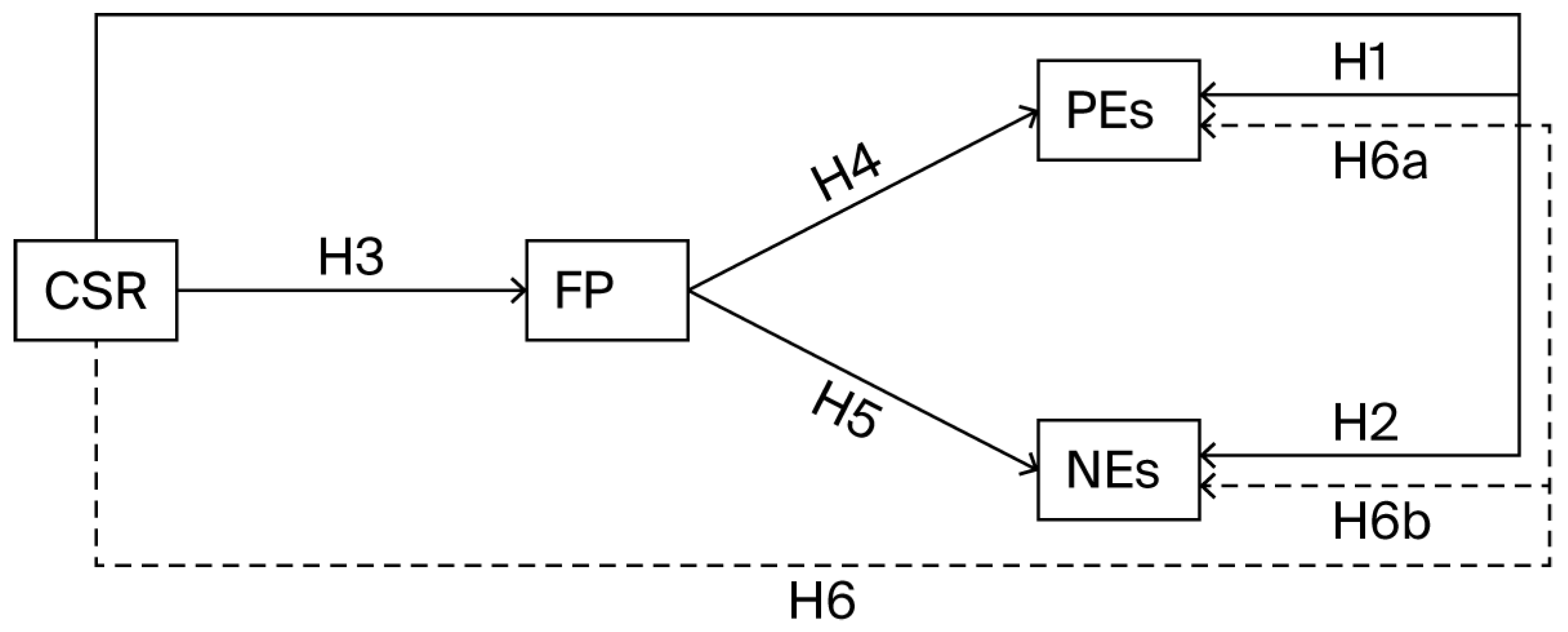

2.8. Research Model and Mediation Hypothesis

3. Methodology

3.1. Procedure and Analyses

3.2. Sample

3.3. Instruments

4. Results

4.1. Pilot Study

4.2. Preliminary Analyses

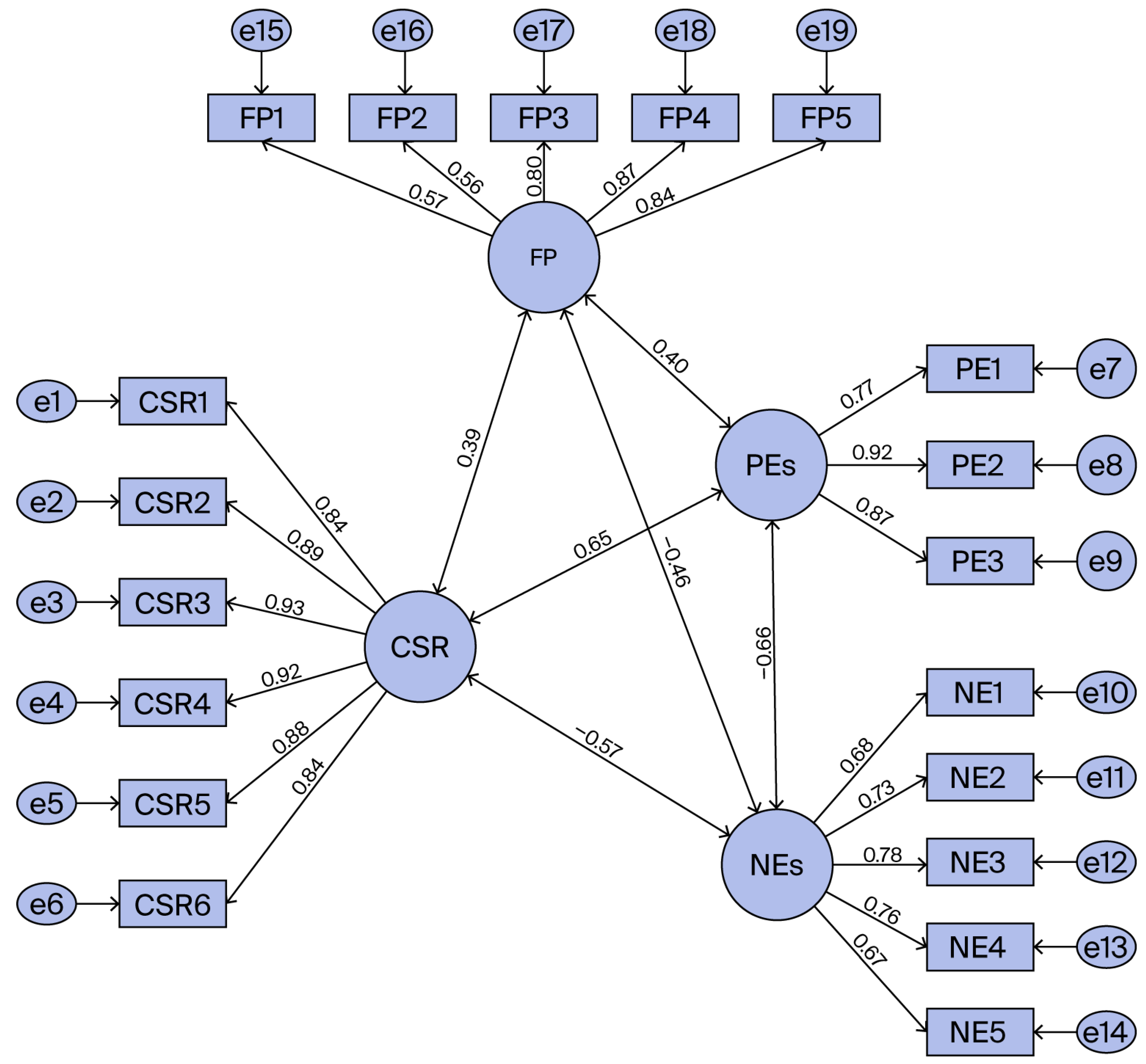

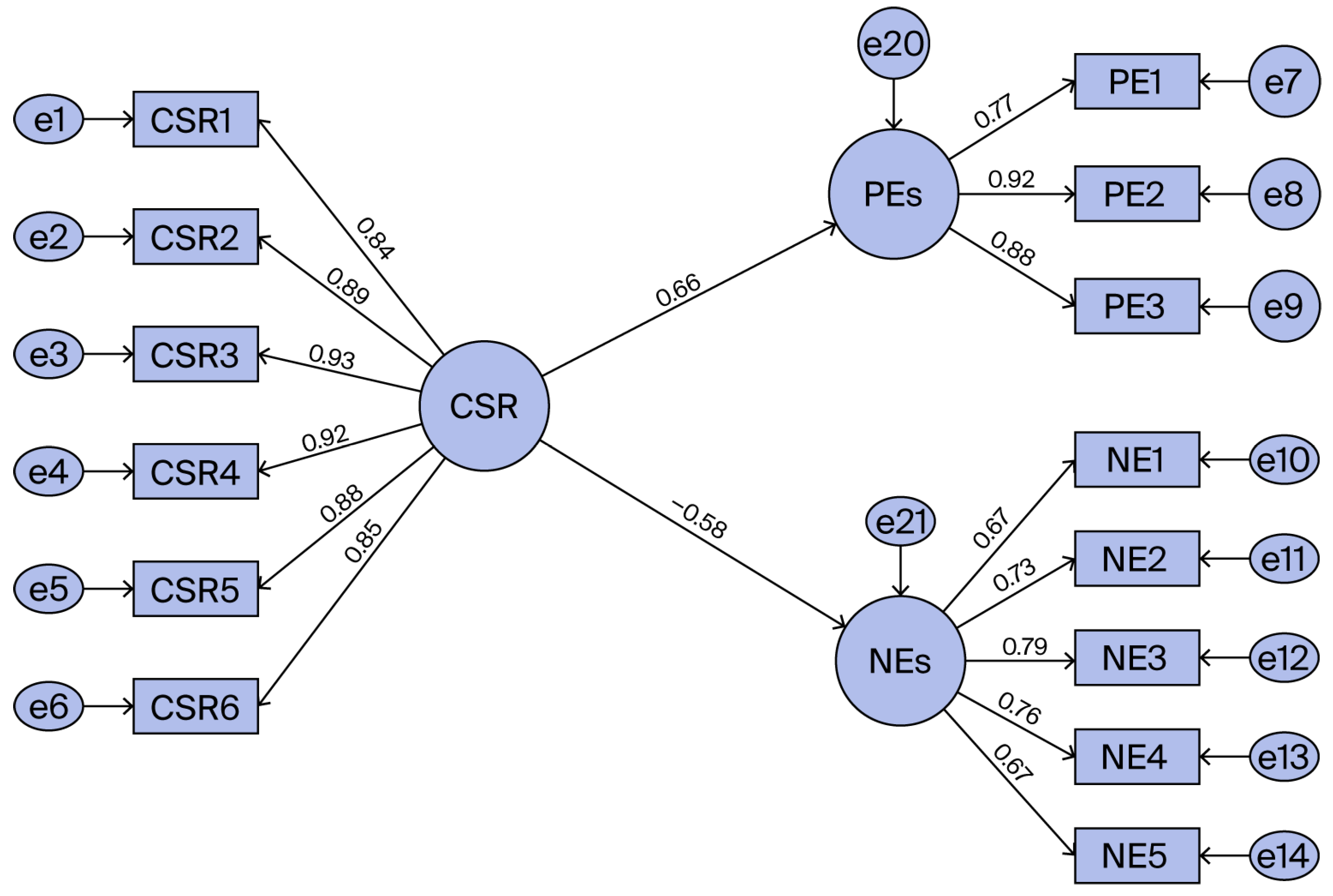

4.3. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

4.4. Common Method Bias Assessment

4.5. Validity, Reliability, and Correlation Analyses

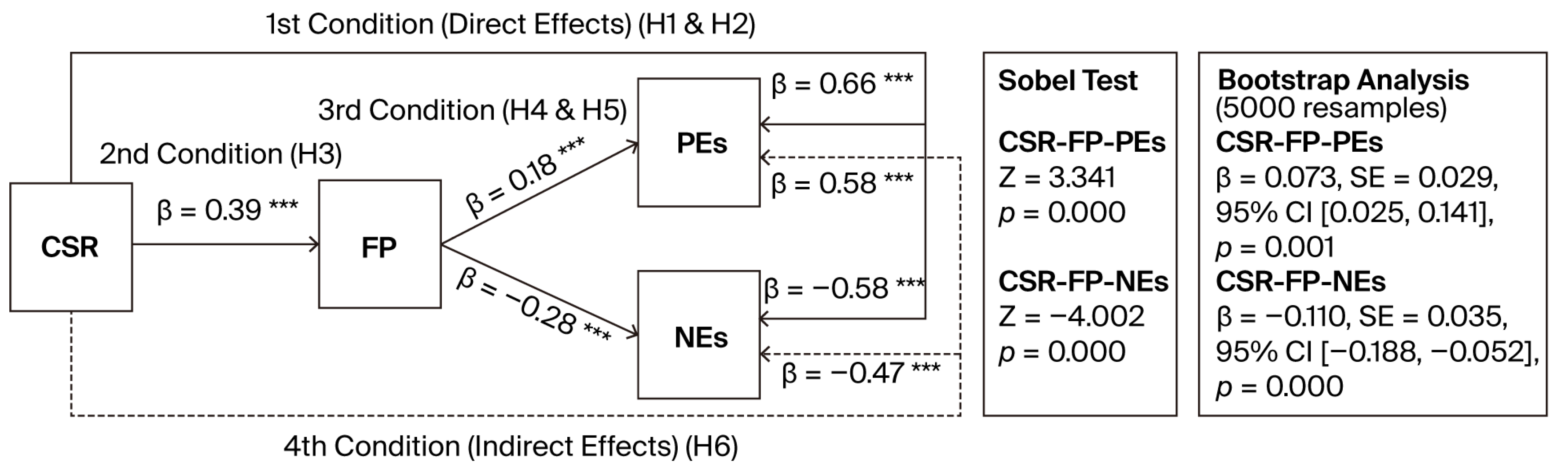

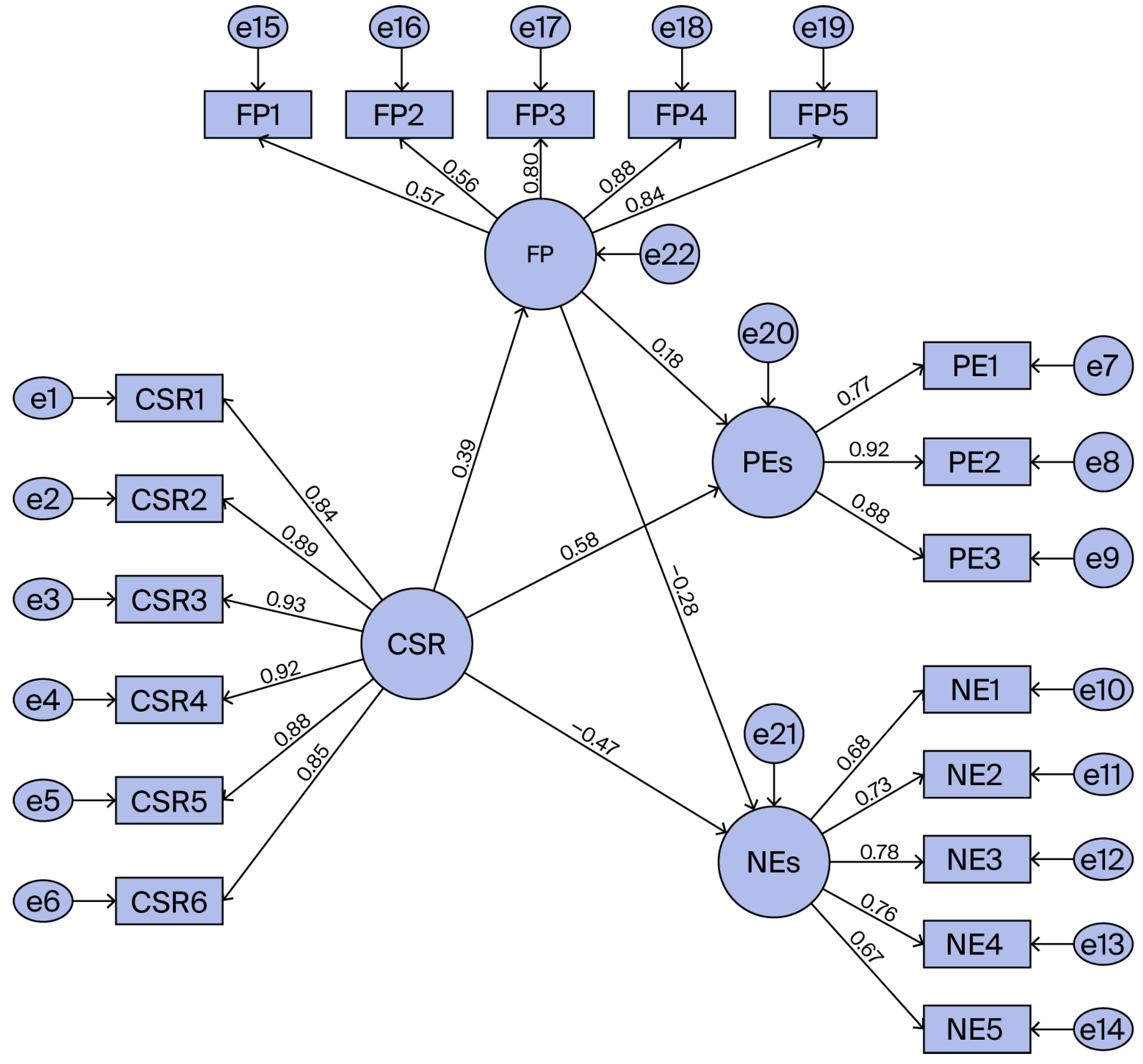

4.6. Testing the Research Hypotheses

5. Discussion

- As customers’ perceptions of their bank fulfilling its social responsibilities toward society become stronger, their perceptions of the bank’s performance (particularly with respect to profitability and continuity) also improve.

- As customers’ perceptions of their bank’s performance (particularly regarding profitability and continuity) improve, their positive emotional responses toward the bank become stronger, while their negative emotional responses diminish.

- Additionally, as customers’ perceptions of their bank fulfilling its social responsibilities toward society increase, their positive emotional responses toward the bank become stronger, while their negative emotional responses diminish. These relationships are further reinforced by the fact that bank customers’ stronger perceptions of their bank fulfilling its social responsibilities toward society enhance their perceptions of the bank’s performance (particularly with respect to profitability and continuity).

5.1. Theoretical and Managerial Implications

5.2. Limitations and Future Research Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Su, L.; Huang, S.; van der Veen, R.; Chen, X. Corporate social responsibility, corporate reputation, customer emotions and behavioral intentions: A structural equation modeling analysis. J. China Tour. Res. 2014, 10, 511–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Gonzalez, S.; Vilela, B.B. The influence of emotions on the relationship between corporate social responsibility and consumer loyalty. ESIC Market. Econ. Bus. J. 2016, 47, 373–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Perez, A.; Rodríguez del Bosque, I. An integrative framework to understand how CSR affects customer loyalty through identification, emotions and satisfaction. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 129, 571–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, A.; Farrukh, M.; Wang, G.; Iqbal, M.K.; Farhan, M. Effects of hotels’ corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives on green consumer behavior: Investigating the roles of consumer engagement, positive emotions, and altruistic values. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2023, 32, 870–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Swanson, S.R.; Hsu, M.; Chen, X. How does perceived corporate social responsibility contribute to green consumer behavior of Chinese tourists: A hotel context. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 3157–3176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taş, A.; Özkara, Z.U. Relationship between corporate social responsibility and customer loyalty: The mediating effect of positive affect. In Sustainability: A Phenomenon Intersecting Different Disciplines; Aydıntan, B., Özkara, Z.U., Eds.; Gazi Kitabevi: Ankara, Turkey, 2023; pp. 77–103. [Google Scholar]

- Arian, A.; Sands, J.; Tooley, S. Industry and stakeholder impacts on corporate social responsibility (CSR) and financial performance: Consumer vs. industrial sectors. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazacu, M.; Dumitriu, S.; Georgescu, I.; Berceanu, D.; Simion, D.; Varzaru, A.A.; Bocean, C.G. A perceptual approach to the impact of CSR on organizational financial performance. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagiorgos, T. Corporate social responsibility and financial performance: An empirical analysis on Greek companies. Eur. Res. Stud. J. 2010, 13, 85–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-S.; Deng, X.; Chang, C.-H. Examining the interactive effect of advertising investment and corporate social responsibility on financial performance. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2023, 16, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Esfahbodi, A.; Zhang, Y. The impact of corporate social responsibility implementation on enterprises’ financial performance—Evidence from Chinese listed companies. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Suar, D. Does corporate social responsibility influence firm performance of Indian companies? J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 95, 571–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siueia, T.T.; Wang, J.; Deladem, T.G. Corporate social responsibility and financial performance: A comparative study in the Sub-Saharan Africa banking sector. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 226, 658–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Başgöze, P.; Özkan Tektaş, Ö. The effects of negative emotions and corporate reputation on alternative voice complaint behavior of bank customers. J. Mark. Mark. Res. 2021, 14, 427–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Lennon, S.J. Effects of reputation and website quality on online consumers’ emotion, perceived risk and purchase intention: Based on the stimulus-organism-response model. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2013, 7, 33–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J. The impacts of perceived risk and negative emotions on the service recovery effect for online travel agencies: The moderating role of corporate reputation. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 685351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leclercq-Machado, L.; Alvarez-Risco, A.; Esquerre-Botton, S.; Almanza-Cruz, C.; de las Mercedes Anderson-Seminario, M.; Del-Aguila-Arcentales, S.; Yanez, J.A. Effect of corporate social responsibility on consumer satisfaction and consumer loyalty of private banking companies in Peru. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cintamür, İ.G.; Yüksel, C.A. Measuring customer based corporate reputation in banking industry: Developing and validating an alternative scale. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2018, 36, 1414–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razzaq, Z.; Razzaq, A.; Yousaf, S.; Akram, U.; Hong, Z. The impact of customer equity drivers on loyalty intentions among Chinese banking customers: The moderating role of emotions. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2019, 31, 980–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P.M. Exchange and Power in Social Life; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J.C. The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In Psychology of Intergroup Relations; Worchel, S., Austin, W.G., Eds.; Nelson-Hall Publishers: Chicago, IL, USA, 1986; pp. 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Pitman: Boston, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Gouldner, A.W. The norm of reciprocity: A preliminary statement. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1960, 25, 161–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiaei, K.; Bontis, N.; Barani, O.; Jusoh, R. Corporate social responsibility and sustainability performance measurement systems: Implications for organizational performance. J. Manag. Control 2021, 32, 85–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homayoun, S.; Mashayekhi, B.; Jahangard, A.; Samavat, M.; Rezaee, Z. The controversial link between CSR and financial performance: The mediating role of green innovation. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahi, A.B.M.F.; Johansson, J.; Blomkvist, M.; Hartwig, F. Corporate sustainability and financial performance: A hybrid literature review. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2024, 31, 801–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Shakir, M.I.; Azam, A.; Mahmood, S.; Zhang, Q.; Ahmad, Z. The impact of CSR and green consumption on consumer satisfaction and loyalty: Moderating role of ethical beliefs. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 113820–113834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, H.-K.; Phan, H.-T. Revealing the role of corporate social responsibility, service quality, and perceived value in determining customer loyalty: A meta-analysis study. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. Attitude–behavior relations: A theoretical analysis and review of empirical research. Psychol. Bull. 1977, 84, 888–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, T.M. The relationship between the affective, behavioral, and cognitive components of attitude. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1969, 5, 12–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapur, V. Women and corporate social responsibility in banking sector. JIMS8M J. Indian Manag. Strat. 2015, 20, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoury, G.; Rostami, J.; Turnbull, J.P. Corporate Social Responsibility: Turning Words into Action (Report 255-99); Conference Board of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Jamali, D.; Karam, C. Corporate social responsibility in developing countries as an emerging field of study. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2018, 20, 32–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hierden, Y.T.; Dietrich, T.; Rundle-Thiele, S. A citizen-centred approach to CSR in banking. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2021, 39, 638–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Huang, Y.; Chan, H.-Y.; Yang, C.-H. The impact of corporate social responsibility practices on customer value co-creation and perception in the digital context: A case study of Taiwan bank industry. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbaş Tuna, A.; Özkara, Z.U.; Taş, A. A study on adaptation of the stakeholder-based corporate social responsibility scale to Turkish. Ank. Haci Bayram Veli Univ. J. Fac. Econ. Adm. Sci. 2019, 21, 263–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlsrud, A. How corporate social responsibility is defined: An analysis of 37 definitions. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2008, 15, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puci, J.; Guxholli, S. Business internal auditing—An effective approach in developing sustainable management systems. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 7, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Chu, Y.C.; Lai, F. Mobile time banking on blockchain system development for community elderly care. J. Ambient Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 2023, 14, 13223–13235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salman, M.; Gupta, P. Corporate social responsibility and social development: New vistas of social work practice in India. J. Soc. Work Educ. Pract. 2021, 6, 10–19. [Google Scholar]

- Kwan, C.K. Socially responsible human resource practices to improve the employability of people with disabilities. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gürlek, M.; Düzgün, E.; Meydan Uygur, S. How does corporate social responsibility create customer loyalty? The role of corporate image. Soc. Responsib. J. 2017, 13, 409–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özkara, Z.U.; Taş, A.; Aydıntan, B. The effect of perceived corporate social responsibility on altruistic behavior: The mediating role of positive affect. Gazi J. Econ. Bus. 2022, 8, 364–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bebbington, J.; Unerman, J. Achieving the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals: An enabling role for accounting research. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2018, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazzola, P.; Pavione, E.; Amelio, S.; Mauri, M. Sustainable strategies and value creation in the food and beverage sector: The case of large listed European companies. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavic, P.; Lukman, R. Review of sustainability terms and their definitions. J. Clean. Prod. 2007, 15, 1875–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, R. A holistic perspective on corporate sustainability drivers. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2015, 22, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatma, M.; Khan, I.; Kumar, V.; Shrivastava, A.K. Corporate social responsibility and customer-citizenship behaviors: The role of customer-company identification. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2022, 34, 858–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aracil, E.; Najera-Sanchez, J.J.; Forcadell, F.J. Sustainable banking: A literature review and integrative framework. Financ. Res. Lett. 2021, 43, 101932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yip, A.W.H.; Bocken, N.M.P. Sustainable business model archetypes for the banking industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 174, 150–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birindelli, G.; Ferretti, P.; Intonti, M.; Iannuzzi, A.P. On the drivers of corporate social responsibility in banks: Evidence from an ethical rating model. J. Manag. Gov. 2015, 19, 303–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, O. Corporate sustainability and financial performance of Chinese banks. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2017, 8, 358–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddique, M.N.E.A.; Nor, S.M.; Senik, Z.C.; Omar, N.A.; Rashid, N. Corporate social responsibility as the pathway to sustainable banking: A systematic literature review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholtens, B. Corporate social responsibility in the international banking industry. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 86, 159–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torre Olmo, B.; Cantero Saiz, M.; Sanfilippo Azofra, S. Sustainable banking, market power, and efficiency: Effects on banks’ profitability and risk. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.-W.; Shen, C.-H. Corporate social responsibility in the banking industry: Motives and financial performance. J. Bank. Financ. 2013, 37, 3529–3547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menicucci, E. ESG Integration in the Banking Sector: Navigating Regulatory Frameworks and Strategic Challenges for Financial Institutions; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Regulation (EU) 2020/852 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 18 June 2020 on the Establishment of a Framework to Facilitate Sustainable Investment, and Amending Regulation (EU) 2019/2088 (EU Taxonomy Regulation); European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020; Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2020/852/oj/eng (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- European Commission. Regulation (EU) 2019/2088 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 November 2019 on Sustainability Related Disclosures in the Financial Services Sector (SFDR); European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2019; Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2019/2088/oj/eng (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- European Commission. Directive (EU) 2022/2464 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 December 2022 Amending Directive 2013/34/EU, Directive 2004/109/EC, Directive 2006/43/EC and Regulation (EU) No 537/2014, as Regards Corporate Sustainability Reporting (CSRD); European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2022; Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2022/2464/oj/eng (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- BRSA. Sustainable Banking in Turkey (Presentation); BRSA: Ankara, Turkey, 2022; Available online: https://www.bddk.org.tr/KurumHakkinda/EkGetir/19?ekId=145 (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- CMB. Guidelines on Green Debt Instruments, Sustainable Debt Instruments, Green Lease Certificates and Sustainable Lease Certificates; Capital Markets Board of Turkey (CMB): Ankara, Turkey, 2022. Available online: https://spk.gov.tr/data/6231ce881b41c612808a3a1c/b2d06c64099c9e7e8877743afc7d2484.pdf (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- D’Orazio, P.; Popoyan, L. Fostering green investments and tackling climate-related financial risks: Which role for macroprudential policies? Ecol. Econ. 2019, 160, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banking Law, No. 5411; Adopted on 19 October 2005, 1 November 2005/25983; Official Gazette: Ankara, Turkey, 2005. Available online: https://www.mevzuat.gov.tr/mevzuat?MevzuatNo=5411&MevzuatTur=1&MevzuatTertip=5 (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Turkish Commercial Code. Law No. 6102; Adopted on 13 January 2011, 14 February 2011/27846; Official Gazette: Ankara, Turkey, 2011. Available online: https://www.mevzuat.gov.tr/mevzuat?MevzuatNo=6102&MevzuatTur=1&MevzuatTertip=5 (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Capital Markets Law, No. 6362; Adopted on 6 December 2012, 30 December 2012/28513; Official Gazette: Ankara, Turkey, 2012. Available online: https://www.mevzuat.gov.tr/mevzuat?MevzuatNo=6362&MevzuatTur=1&MevzuatTertip=5 (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Güngöroğlu, C.; Özkara, Z.U.; Tutmaz, V. Forest fire management in Türkiye: Problems and solution suggestions. Memleket Siyaset Yönetim MSY J. 2024, 19, 517–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commission of the European Communities. Green Paper: Promoting a European Framework for Corporate Social Responsibility; COM (2001) 366 Final; Commission of the European Communities: Brussels, Belgium, 2001; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/DOC_01_9 (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Pinney, C. Imagine Speaks Out: How to Manage Corporate Social Responsibility and Reputation in a Global Marketplace: The Challenge for Canadian Business; Imagine: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- World Business Council for Sustainable Development. Corporate Social Responsibility: The WBCSD’s Journey; World Business Council for Sustainable Development: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002; Available online: https://www.globalhand.org/system/assets/f65fb8b06bddcf2f2e5fef11ea7171049f223d85/original/Corporate_Social_Responsability_WBCSD_2002.pdf (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Nelson, J.; Prescott, D. Business and the Millennium Development Goals: A Framework for Action; (Report No. 2); UNDP International Business Leaders Forum: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008; pp. 1–34. Available online: https://gbsn.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Business_and_MDGs2008.pdf (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Aguinis, H.; Glavas, A. What we know and don’t know about corporate social responsibility: A review and research agenda. J. Manag. 2012, 38, 932–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diez-Canamero, B.; Bishara, T.; Otegi-Olaso, J.R.; Minguez, R.; Fernandez, J.M. Measurement of corporate social responsibility: A review of corporate sustainability indexes, rankings and ratings. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, M. The social Responsibility of business is to increase its profits. The New York Times Magazine. 13 September 1970, pp. 32–33; 122–126. Available online: https://graphics8.nytimes.com/packages/pdf/business/miltonfriedman1970.pdf (accessed on 27 September 2025).

- Maignan, I.; Ferrell, O.C. Measuring corporate citizenship in two countries: The case of the United States and France. J. Bus. Ethics 2000, 23, 283–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, A.; Martinez, P.; Rodríguez del Bosque, I. The development of a stakeholder-based scale for measuring corporate social responsibility in the banking industry. Serv. Bus. 2013, 7, 459–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turker, D. Measuring corporate social responsibility: A scale development study. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 85, 411–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E.; Harrison, J.S.; Wicks, A.C.; Parmar, B.L.; De Colle, S. Stakeholder Theory: The State of the Art; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, J.W. Business Ethics: A Stakeholder and Issues Management Approach, 5th ed.; South-Western Cengage Learning: Mason, OH, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Q.; Hu, L. Does perceived corporate social responsibility motivate hotel employees to voice? The role of felt obligation and positive emotions. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 48, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatma, M.; Khan, I. Impact of CSR on customer citizenship behavior: Mediating the role of customer engagement. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatma, M.; Rahman, Z. The CSR’s influence on customer responses in Indian banking sector. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 29, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazzi, O.; Maldaon, I. Corporate social responsibility: A review with potential development. Manag. Sustain. Arab Rev. 2023, 2, 144–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adiwijaya, K.; Fauzan, R. Cause-related marketing: The influence of cause-brand fit, firm motives and attribute altruistic to consumer inferences and loyalty and moderation effect of consumer values. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Economics Marketing and Management, Singapore, 26–28 February 2012; Volume 28, pp. 49–54. [Google Scholar]

- Hur, W.M.; Kim, H.; Kim, H.K. Does customer engagement in corporate social responsibility initiatives lead to customer citizenship behaviour? The mediating roles of customer-company identification and affective commitment. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 1258–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Ren, X.; Sun, X.; Jin, C. The effect of corporate social responsibility characteristics on employee green behavior: A moral emotions perspective. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matute-Vallejo, J.; Bravo, R.; Pina, J.M. The influence of corporate social responsibility and price fairness on customer behaviour: Evidence from the financial sector. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2011, 18, 317–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, A.A.; Amsami, M.; Ibrahim, S.B. Relationship between ethical corporate social responsibility and customer loyalty: The mediating role of customers’ gratitude. Indep. J. Manag. Prod. 2021, 12, 2194–2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.M.; Park, S.Y.; Rapert, M.I.; Newman, C.L. Does perceived consumer fit matter in corporate social responsibility issues? J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 1558–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, L.; Ruiz, S.; Rubio, A. The role of identity salience in the effects of corporate social responsibility on consumer behavior. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 84, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrenko, O.V.; Aime, F.; Ridge, J.; Hill, A. Corporate social responsibility or CEO narcissism? CSR motivations and organizational performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2016, 37, 262–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.H. Proactive and reactive corporate social responsibility: Antecedent and consequence. Manag. Decis. 2015, 53, 451–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Gao, L. Corporate social responsibility of forestry companies in China: An analysis of contents, levels, strategies, and determinants. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Sang, B.; Liu, J.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, Y. Associations between emotional resilience and mental health among Chinese adolescents in the school context: The mediating role of positive emotions. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lankarani, M.M.; Assari, S. Positive and negative affect more concurrent among blacks than whites. Behav. Sci. 2017, 7, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Yperen, N.W. On the link between different combinations of negative affectivity (NA) and positive affectivity (PA) and job performance. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2003, 35, 1873–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panaccio, A.; Vandenberghe, C. Five-factor model of personality and organizational commitment: The mediating role of positive and negative affective states. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 80, 647–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, M.; Matsuzaki, N.; Kawahara, J. Measurement of mood states following light alcohol consumption: Evidence from the implicit association test. Behav. Sci. 2018, 8, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasper, K. A case for neutrality: Why neutral affect is critical for advancing affective science. Affect. Sci. 2023, 4, 458–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, D.; Clark, L.A.; Tellegen, A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laros, F.J.M.; Steenkamp, J.B.E.M. Emotions in consumer behavior: A hierarchical approach. J. Bus. Res. 2005, 58, 1437–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zevon, M.A.; Tellegen, A. The structure of mood change: An idiographic/nomothetic analysis. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1982, 43, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humpel, N.; Caputi, P.; Martin, C. The relationship between emotions and stress among mental health nurses. Aust. N. Z. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2001, 10, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.K.; Malhotra, N.K.; Guan, C. Positive and negative affectivity as mediators of volunteerism and service-oriented citizenship behavior and customer loyalty. Psychol. Mark. 2012, 29, 1004–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Zong, M.; Yang, Z.; Gu, W.; Dong, D.; Qiao, Z. When altruists cannot help: The influence of altruism on the mental health of university students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Glob. Health 2020, 16, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rychalski, A.; Hudson, S. Asymmetric effects of customer emotions on satisfaction and loyalty in a utilitarian service context. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 71, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gayathree, P.K.; Samarasinghe, D. Green stimuli characteristics and green self-identity towards ethically minded consumption behavior with special reference to mediating effect of positive and negative emotions. Asian Soc. Sci. 2019, 15, 77–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentini, S.; Orsingher, C.; Polyakova, A. Customers’ emotions in service failure and recovery: A meta-analysis. Mark. Lett. 2020, 31, 199–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subba, D.; Kumar, S. Employees’ responses to corporate social responsibility: A study among the employees of banking industry in India. Decision 2018, 45, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Xie, C.; Morrison, A.M. The effect of corporate social responsibility on hotel employee safety behavior during COVİD-19: The moderation of belief restoration and negative emotions. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 46, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vito, D. Corporate reputation: A literature review. In Corporate Reputation as Strategic Intangible Asset; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 11–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cintamür, İ.G. Developing an Alternative Scale for Measuring Customer Based Corporate Reputation in Banking Industry. Ph.D. Thesis, Istanbul University, Istanbul, Turkey, 2015. Available online: https://tez.yok.gov.tr/UlusalTezMerkezi (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Hillier, D.; Ross, S.; Westerfield, R.; Jaffe, J.; Jordan, B. Corporate Finance, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hamad, H.A.; Cek, K. The moderating effects of corporate social responsibility on corporate financial performance: Evidence from OECD countries. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thuy, D.T. Literature review on factors affecting financial performance of firms. Int. J. Bus. Manag. Invent. (IJBMI) 2023, 12, 181–188. Available online: https://www.ijbmi.org/papers/Vol(12)6/T1206181188.pdf (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Kharouf, H.; Lund, D.J.; Krallman, A.; Pullig, C. A signaling theory approach to relationship recovery. Eur. J. Mark. 2020, 54, 2139–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruszczynski, M. Corporate governance and financial performance of companies in Poland. Int. Adv. Econ. Res. 2006, 12, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Amba, S.M. Corporate governance and firms’ financial performance. J. Acad. Bus. Ethics 2014, 8, 1–11. Available online: https://www.aabri.com/manuscripts/131587.pdf (accessed on 30 July 2025).[Green Version]

- Kyere, M.; Ausloos, M. Corporate governance and firms financial performance in the United Kingdom. Int. J. Financ. Econ. 2021, 26, 1871–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, A.C.A. The impact of corporate governance practices on firms’ financial performance: Evidence from Malaysian companies. ASEAN Econ. Bull. 2004, 21, 308–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, M.; Nerino, M.; Capasso, A. Corporate governance and financial performance of Italian listed firms. The results of an empirical research. Corp. Ownersh. Control 2015, 12, 628–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochran, P.L.; Wood, R.A. Corporate social responsibility and financial performance. Acad. Manag. J. 1984, 27, 42–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, M. Job market signaling. Q. J. Econ. 1973, 87, 355–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moors, A. Appraisal theory of emotion. In Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences; Zeigler-Hill, V., Shackelford, T.K., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Richins, M.L. Measuring emotions in the consumption experience. J. Consum. Res. 1997, 24, 127–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics, 6th ed.; Pearson Prentice Hall: Boston, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, M.; Lewis, P.; Thornhill, A. Research Methods for Business Students, 5th ed.; Prentice Hall: Harlow, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Turkish Statistical Institute. Address Based Population Registration System Results; Turkish Statistical Institute: Ankara, Turkey, 2024. Available online: https://data.tuik.gov.tr/Bulten/Index?p=Adrese-Dayali-Nufus-Kayit-Sistemi-Sonuclari-2023-49684 (accessed on 6 February 2024).

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P.M.; Bonett, D.G. Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychol. Bull. 1980, 88, 588–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 2nd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, M.W.; Cudeck, R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In Testing Structural Equation Models; Bollen, K.A., Long, J.S., Eds.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1993; pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harman, H.H. Modern Factor Analysis; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Eichhorn, B.R. Common Method Variance Techniques; Cleveland State University, Department of Operations and Supply Chain Management: Cleveland, OH, USA; SAS Institute Inc.: Cary, NC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gefen, D.; Straub, D.; Boudreau, M.C. Structural equation modeling and regression: Guidelines for research practice. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2000, 4, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Evaluating model fit. In Structural Equation Modeling: Concepts, Issue, and Applications; Hoyle, R.H., Ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995; pp. 76–99. [Google Scholar]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Leonardelli, G.J. Calculation for the Sobel Test: An Interactive Calculation Tool for Mediation Tests. 2010. Available online: http://www.quantpsy.org/sobel/sobel.htm (accessed on 29 January 2025).

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Contemporary approaches to assessing mediation in communication research. In The Sage Sourcebook of Advanced Data Analysis Methods for Communication Research; Hayes, A.F., Slater, M.D., Snyder, L.B., Eds.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008; pp. 13–54. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon, D.P.; Fairchild, A.J.; Fritz, M.S. Mediation analysis. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2007, 58, 593–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Scale Items | Factor Loadings |

|---|---|

| Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR): I believe that my bank… | |

| CSR1: Helps solve social problems. | 0.840 |

| CSR2: Uses part of its budget for donations and social projects to advance the situation of the most unprivileged groups of society. | 0.888 |

| CSR3: Contributes money to cultural and social events (e.g., music, sports). | 0.931 |

| CSR4: Plays a role in society beyond economic benefit generation. | 0.916 |

| CSR5: Is concerned with improving the general well-being of society. | 0.876 |

| CSR6: Is concerned with respecting and protecting the natural environment. | 0.844 |

| Financial Performance (FP): It seems to me that my bank… | |

| FP1: Is powerful in terms of economic condition. | 0.568 |

| FP2: Is a highly profitable corporation. | 0.558 |

| FP3: Is not liable to go bankrupt. | 0.803 |

| FP4: Is a long-established corporation. | 0.875 |

| FP5: Is a corporation that will continue its existence in the future. | 0.841 |

| Positive Emotions (PEs): When receiving service from my bank, I feel… | |

| PE1: Enthusiastic. | 0.772 |

| PE2: Joyful. | 0.923 |

| PE3: Happy. | 0.870 |

| Negative Emotions (NEs): When receiving service from my bank, I feel… | |

| NE1: Angry. | 0.678 |

| NE2: Sad. | 0.733 |

| NE3: Regretful. | 0.776 |

| NE4: Irritated. | 0.758 |

| NE5: Disappointed. | 0.674 |

| Fit Indices | χ2/sd * | TLI ** | IFI ** | CFI *** | RMSEA **** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Threshold Values | <5.0 | ≥0.90 | ≥0.90 | ≥0.90 | ≤0.10 |

| Model Values | 4.193 | 0.910 | 0.923 | 0.923 | 0.087 |

| Post-CLF Model Values | 4.222 | 0.909 | 0.923 | 0.923 | 0.087 |

| Variables | (α) | CR | AVE | MSV | ASV | Gender | CSR | FP | PEs | NEs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||||

| CSR | 0.954 | 0.955 | 0.779 | 0.374 | 0.259 | −0.022 † | (0.882) | |||

| FP | 0.855 | 0.855 | 0.550 | 0.200 | 0.150 | −0.015 † | 0.353 ** | (0.741) | ||

| PEs | 0.889 | 0.892 | 0.734 | 0.374 | 0.280 | 0.009 † | 0.612 ** | 0.354 ** | (0.856) | |

| NEs | 0.845 | 0.846 | 0.525 | 0.342 | 0.273 | −0.051 † | −0.528 ** | −0.448 ** | −0.585 ** | (0.724) |

| (µ) | - | - | - | - | - | - | 3.445 | 3.978 | 3.739 | 2.214 |

| SD | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.848 | 0.719 | 0.983 | 0.804 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Özkara, Z.U.; Koçoğlu, Ş.; Taş-Kaya, A.; Akyol, A.; Aykut, S. Sustainable Banking Through Corporate Social Responsibility: Financial and Emotional Pathways of Customer Perceptions—Evidence from Ankara, the Capital of Turkey. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10139. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210139

Özkara ZU, Koçoğlu Ş, Taş-Kaya A, Akyol A, Aykut S. Sustainable Banking Through Corporate Social Responsibility: Financial and Emotional Pathways of Customer Perceptions—Evidence from Ankara, the Capital of Turkey. Sustainability. 2025; 17(22):10139. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210139

Chicago/Turabian StyleÖzkara, Zülfi Umut, Şahnaz Koçoğlu, Aynur Taş-Kaya, Aylin Akyol, and Serdar Aykut. 2025. "Sustainable Banking Through Corporate Social Responsibility: Financial and Emotional Pathways of Customer Perceptions—Evidence from Ankara, the Capital of Turkey" Sustainability 17, no. 22: 10139. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210139

APA StyleÖzkara, Z. U., Koçoğlu, Ş., Taş-Kaya, A., Akyol, A., & Aykut, S. (2025). Sustainable Banking Through Corporate Social Responsibility: Financial and Emotional Pathways of Customer Perceptions—Evidence from Ankara, the Capital of Turkey. Sustainability, 17(22), 10139. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210139