Abstract

This study examines the mechanisms through which ecological public art influences pro-environmental behavior, addressing the urgent challenges of the global ecological crisis and sustainable urban development. Using the 5th Shanghai Urban Space Art Season (SUSAS) as a case study, a serial multiple mediation model was established, with ecological public art perception as the independent variable, environmental psychological ownership and ecological awareness as mediators, and pro-environmental behavior as the dependent variable. Based on 326 valid responses, structural equation modeling (SEM), which integrates confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and path analysis, demonstrates that ecological public art perception significantly enhances pro-environmental behavior. Environmental psychological ownership and ecological awareness function not only as independent mediators but also jointly constitute a serial mediation pathway. The findings reveal a multidimensional process whereby ecological public art enhances pro-environmental behavior through “perceptual activation–emotional identification–cognitive enhancement–behavioral transformation”. Building on these insights, the study proposes intervention strategies focusing on multi-sensory integration, emotional narrative, digital technology application, and community-based practices to reinforce the role of ecological public art in urban environmental governance and sustainable development. Overall, this research advances the theoretical understanding of the social functions of public art and offers a valuable perspective for fostering ecological awareness and action.

1. Introduction

With the rapid advancement of industrialization and urbanization, the global ecological environment is facing severe challenges. Climate change, the sharp decline in biodiversity, and the depletion of natural resources are placing tremendous pressure on the Earth’s ecosystems. These ecological problems have not only caused extensive damage to the natural environment but also pose a direct threat to the sustainable development of human society. In response to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), countries around the world have taken proactive measures. Progress has been made in areas such as healthcare, education, energy infrastructure, and digital connectivity, leading to tangible improvements in the lives of millions. However, the current pace of transformation remains insufficient to achieve the 2030 targets. The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2025 indicates that while the SDGs are still within reach, achieving them requires immediate and coordinated global action []. Therefore, in addition to top-down governmental policies and regulatory frameworks, the promotion of proactive environmental behavior is increasingly regarded as a key strategy for addressing ecological crises. Ecology examines the interdependence among species and the complex systems that sustain life on Earth []. When integrated into public art, ecology enables artworks to bridge scientific knowledge and the public, playing a crucial role in communicating issues, raising awareness, and guiding behavior []. Historically, artists have actively participated in social movements and maintained close ties with those devoted to environmental protection []. Many have conveyed, through their works, the profound relationship between humans and the natural environment. Against this backdrop, ecological public art has emerged as an art form that integrates ecological concepts and responds to environmental concerns. Through its representation and advocacy of ecological themes in public spaces, it has gradually attracted widespread attention. Many environmental and art educators consider art to be a powerful tool for enhancing environmental education, as it can make the learning process more experiential and engaging [,,,]. By doing so, it helps to address issues such as emotional detachment and a lack of resonance often encountered in environmental education processes []. In the context of urban public spaces, Kay and Scherber (2019) argue that integrating urban ecological experiments into temporary public art projects can transform vacant urban land into hubs of community engagement, thereby encouraging broader public participation []. These perspectives have been substantiated in practice. Several examples of ecological public art illustrate this integration. For instance, Mel Chin’s phytoremediation project Revival Field in a brownfield site in Minnesota [], Weileder’s Stilt House in Singapore created using sustainable materials [], and Olafur Eliasson’s participatory artwork Earth Speaker, which invites children around the world to speak up for the planet [], all embody ecological concerns through public art practices. These projects exemplify how ecological principles, such as material recycling, ecosystem restoration, and participatory awareness, can be embodied through creative practice, transforming scientific ecology into a lived and social experience. They not only reflect attention to ecological challenges but also emphasize social justice. Therefore, this study proposes that examining the mechanisms through which ecological public art influences pro-environmental behavior can help identify key interactive factors between art and behavior. This perspective may offer diverse approaches to addressing ecological problems.

Over the past century, pro-environmental behavior has been extensively analyzed through various behavioral theories. Scholars have employed models such as the Norm Activation Model (NAM) [] and the Value-Belief-Norm (VBN) theory [] to emphasize the importance of environmental values and how these values are internalized into personal norms, thereby motivating individuals to engage in pro-environmental actions []. Pro-environmental behavior encompasses a range of actions undertaken by individuals to contribute to environmental sustainability [], including energy conservation, choosing low-impact transportation, recycling, and pollution reduction. However, the key factors that trigger such behaviors are believed to be influenced by psychological ownership, environmental commitment, and ecological awareness. For instance, Zhenglin Liang (2024) has explored the mediating role of psychological ownership of nature in the relationship between environmental education and residents’ ecological security behavior []. Similarly, Abbas (2022) highlighted the significance of psychological ownership in shaping citizens’ environmental behaviors []. In addition, ecological awareness has often been used by environmental scholars as a mediating variable in studies on green practices, environmental protection, and sustainable consumption, serving to reveal its specific role in promoting pro-environmental behavior [,,]. Nevertheless, when the public encounters ecological public art and engages with it interactively, the resulting sensory perception and emotional responses are often complex. Therefore, it may be limiting to examine either psychological ownership or ecological awareness as a single mediating factor. This study introduces both environmental psychological ownership and ecological awareness as mediating variables and constructs a multiple mediation model. The aim is to comprehensively reveal the complex psychological mechanisms and value transmission pathways through which ecological public art influences pro-environmental behavior.

This study adopts a case study approach as its primary research method, focusing on the thematic and practice-based exhibition zones of the 5th SUSAS. The analysis centers on ecological public artworks that are publicly accessible within these areas. The study aims to address the following key research questions: (a) How does ecological public art positively influence pro-environmental behavior among the public? (b) How do factors such as ecological warning, environmental education and interactive participation shape the public’s perception of ecological public art? (c) Do environmental psychological ownership and ecological awareness serve as serial multiple mediators in the relationship between ecological public art perception and pro-environmental behavior? To answer these questions, this research constructs a theoretical framework based on a serial multiple mediation model. In this model, perception of ecological public art is treated as the independent variable, environmental psychological ownership and ecological awareness are modeled as mediating variables, and pro-environmental behavior serves as the dependent variable.

A quantitative research methodology is employed, with the study structured into six main sections. The first section introduces the research background and key content. The second provides a literature review and identifies the factors through which ecological public art fosters pro-environmental behavior. The third section draws on literature, interviews, and online data to inform the development of the research model and hypotheses. The fourth offers a brief overview of the selected cases, research methods, and data collection procedures. The fifth section presents the results of SEM, which incorporates CFA and path analysis, based on 479 collected questionnaires, of which 326 were valid for analysis. The final section discusses the findings, reflects on the study’s limitations, and proposes strategic pathways through which ecological public art can enhance public engagement in pro-environmental behavior. Ultimately, this research seeks to explore how ecological public art may contribute to urban environmental governance and offer a novel artistic approach to advancing sustainable development.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Ecological Public Art

Ecological public art emerges from the intersection of “ecological art” and “public art”, and is also referred to as green art [,,]. Rather than representing a new artistic genre, it constitutes a form of creative practice that integrates environmental ethics and eco-friendly values, with the aim of addressing or raising awareness about environmental issues. Rachel Carson’s seminal book Silent Spring (1962) sounded the alarm on environmental degradation [], subsequently sparking widespread scholarly debates around ecology and environmentalism. This intellectual wave profoundly influenced artists’ ecological concerns and commitments. Ecological art typically advocates for reversing environmental deterioration, while environmental art represents a broader spectrum of practices focused on the appreciation and protection of natural resources []. Public art, by contrast, offers a communicative medium capable of reaching audiences far beyond those who visit galleries or museums []. The integration of ecological art and public art enables it to engage directly with public discourse within shared urban spaces, making it more accessible and acceptable to the public.

In recent years, ecological public artworks have increasingly embraced diverse forms of presentation and interactive engagement to deepen public understanding of and attention to climate change. Giannachi (2012) explored how artists engage with climate-related themes through a variety of artistic strategies—depicting, interpreting, and responding to climate change—emphasizing that data visualizations and immersive experiences in artworks can influence behavioral change among audiences []. Similarly, Mah et al. (2024) examined how virtual encounters with the public art installation Future SHORELINE affected participants’ perceptions, attitudes, behaviors, and emotional responses toward climate risk []. They concluded that immersive artistic experiences could significantly enhance public engagement with climate issues []. Research suggests that multidimensional perception is considered a key factor in triggering emotional responses to ecological concerns. By contrast, purely visual forms may be insufficient to stimulate the level of reflection necessary to drive behavioral change []. From a psychological perspective, perception can be divided into direct and indirect perception. Direct perception refers to the immediate response of an organism to external stimuli through the senses, while indirect perception involves an additional cognitive processing stage in which sensory information is further interpreted after the stimuli have been received []. Similarly, perception of ecological public art can be understood as the audience’s sensory experience of the artwork, which evokes direct reactions and may subsequently lead to cognitive engagement with the environmental messages it conveys. This process can generate more complex psychological transformations. This study therefore focuses on the perceptual elements that foster public awareness, emotional resonance, and a sense of personal responsibility toward ecological issues. It conceptualizes the perception of ecological public art as a critical step in the process through which such art contributes to the development of pro-environmental behavior.

2.2. Environmental Psychological Ownership

Psychological ownership refers to the sense of possession that individuals develop toward both tangible and intangible objects []. It reflects a psychological state in which something is perceived as “mine” or “ours”, a concept rooted in the literature of organizational psychology. According to Wilpert (1991), psychological ownership strengthens an individual’s perceived control or possession over an object—such as the outcome of one’s labor, a personal belonging, a home, or a piece of land. It is considered a cognitive–affective construct that satisfies three fundamental human motivational needs: the desire for efficacy, self-identity, and a sense of belonging []. In the fields of environmental management and environmental psychology, the concept has been extended to encompass the natural environment more broadly. This extension gives rise to an environmental stewardship mindset, whereby individuals perceive the environment as part of themselves, or in other words, develop a sense that “the environment is mine” [,,]. Scholars have emphasized that the emergence and persistence of psychological ownership are not dependent on legal or formal property rights. Rather, psychological ownership of nature may effectively motivate protective behavior, even among individuals who hold strongly anthropocentric worldviews []. Preston and Gelman (2020) further demonstrated that, compared with legal ownership, psychological ownership is more likely to encourage individuals to actively maintain and protect the ecological quality of their living environment []. Residents, as the most immediate stakeholders in their local environments, often develop environmental psychological ownership through prolonged interaction with and identification with the surrounding ecology. Their sense of connection to the place is shaped by their recognition of the ecological conditions and their desire for a high-quality environment []. Based on this understanding, the present study defines environmental psychological ownership as an extension of the theory of psychological ownership within the environmental domain. It refers to an individual’s internalized sense of possession and belonging toward a specific environment, whereby the environment is regarded as an integral part of the self. This psychological state is often accompanied by concern for, affection toward, and a proactive inclination to care for and protect the environment.

Departing from previous research, this study positions environmental psychological ownership as a mediating variable in the relationship between ecological public art and pro-environmental behavior. It aims to examine whether ecological public art can present environmental issues to the public in ways that, through multifaceted artistic experiences, enhance their perception and foster a sense of environmental psychological ownership. This process may, in turn, strengthen ecological awareness and promote the development of pro-environmental behavior.

2.3. Ecological Awareness

Ecological awareness enables individuals and social groups to recognize and understand ecological and environmental issues []. According to O’Sullivan and Taylor (2004), “awareness” represents the mental framework or psychological structure through which individuals interpret the world, construct self-understanding, and seek meaning []. Ecological awareness specifically refers to the understanding of the interrelationships among all living organisms and environmental systems, including humans themselves. It encompasses a range of cognitive and attitudinal components, such as individuals’ knowledge of ecosystems, their understanding of the causes and consequences of ecological problems, and their acceptance of the principles of sustainable development []. Furthermore, Qingpeng Zhang et al. (2016) argue that individuals’ responses to environmental issues reflect their underlying systems of knowledge, beliefs, and motivations []. These responses also demonstrate the extent to which ecological education fosters shared understandings and a collective sense of responsibility toward ecological concerns []. In this regard, public attitudes and behaviors toward the environment are significantly influenced by ecological awareness. As a communicative medium for conveying ecological information, ecological public art has the potential to stimulate psychological responses in viewers through environmental warnings and symbolic expression. This stimulation can lead to the development of more active forms of ecological awareness. This perspective was supported by Sommer and Klöckner (2021) in their study on climate change-related art presented during the ArtCOP21 event in Paris, where they found that such artworks effectively influenced public awareness of climate issues []. Existing studies have consistently shown that a high level of ecological awareness serves as a critical driving force for green behaviors and pro-environmental actions [,,,]. Building on this foundation, the present study incorporates ecological awareness alongside environmental psychological ownership to establish a dual mediation model, aiming to explore the complex mechanisms through which ecological public art influences pro-environmental behavior.

2.4. Pro-Environmental Behavior

Pro-environmental behavior is defined as a class of behaviors that include actions benefiting the natural environment. It represents a form of socially altruistic action that reflects individuals’ positive attitudes and behavioral tendencies toward the environment []. Hines (1987) was among the first to define pro-environmental behavior as a conscious individual action driven by personal responsibility and environmental values, undertaken to avoid or mitigate environmental problems []. This definition emphasizes the autonomy of the actor and the intention to reduce harm to the planet. Subsequently, Steg and Vlek (2009) expanded the definition from the perspective of behavioral impact on the environment, characterizing pro-environmental behavior as any action that minimizes environmental harm and contributes positively to ecological well-being []. Hong Tian et al. (2022) further analyzed the formation and outcomes of pro-environmental behavior by drawing on theories from psychology, sociology, and economics. Although scholars approach the concept from different disciplinary perspectives, the core consensus centers on behavior that benefits the environment. In this study, public pro-environmental behavior refers to individuals’ engagement in environmental actions within the public sphere, the practice of environmentalism in private life, and sustainable behaviors performed in workplace settings []. In relation to the influence of ecological public art on pro-environmental behavior, Curtis et al. (2014) conducted several studies on various artworks and art-based activities []. They concluded that environmental art can encourage pro-environmental behavior through three main strategies: (1) by communicating environmental information in engaging and accessible ways; (2) by fostering empathy toward natural spaces; (3) by incorporating artistic expression into sustainability initiatives to enhance public interest and participation []. Sommer et al. (2019) evaluated the behavioral impact of the environmental art installation Pollution Pods []. Their findings indicated that although participants showed strong behavioral intentions and a slight increase in pro-environmental attitudes after viewing the installation, the study did not detect significant follow-through in terms of real behavioral change, such as tracking personal carbon emissions [].

To more accurately measure pro-environmental behavior in this study, the General Ecological Behavior (GEB) scale is adopted. This scale identifies specific behaviors strongly related to the research context, selected from 50 ecological actions across six dimensions: energy conservation, transportation, waste avoidance, anti-consumerism, recycling, and alternative forms of protective social behavior []. These selected items are used to design a questionnaire structure suitable for the multiple mediation model, aiming to provide a more precise assessment of the actual manifestation of pro-environmental behavior.

2.5. Multiple Mediation Model

A multiple mediation model involves the inclusion of two or more mediating variables and is used to analyze indirect processes through which an independent variable affects a dependent variable. Compared with single mediation models, multiple mediation models are designed to capture the sequential or parallel functioning of multiple mediators []. MacKinnon (2000) proposed a method for comparing the relative contributions of mediating and direct effects within such models []. The introduction of mediators in the model helps to identify specific psychological mechanisms underlying the relationship between antecedent and outcome variables []. As Baron and Kenny (1986) emphasized, the core objective of mediation analysis is to explore the internal mechanisms and specific pathways through which an independent variable influences a dependent variable, with particular attention to indirect relationships between variables []. Given that such indirect pathways are often influenced by more than one factor, researchers frequently employ multiple mediation models to explain complex research questions [,,]. Depending on whether a sequential relationship exists among the mediating variables, multiple mediation models can be classified as either parallel or serial. In a parallel multiple mediation model, the mediators operate independently, each exerting a separate indirect effect on the dependent variable. In contrast, a serial multiple mediation model assumes that the mediators are interrelated and exert their effects in a specific sequence. In this study, the two mediating variables—environmental psychological ownership and ecological awareness—are theoretically and empirically correlated rather than independent. Therefore, a serial multiple mediation model is adopted to more accurately capture the sequential mechanism through which environmental psychological ownership may influence ecological awareness, ultimately affecting pro-environmental behavior. In the present study, the use of a serial multiple mediation model serves to elucidate how the perception of ecological public art exerts a positive influence on pro-environmental behavior through two mediators: environmental psychological ownership and ecological awareness. Compared with a single mediation framework, this approach allows for a more comprehensive examination of how the perception of ecological public art fosters a sense of psychological ownership over the environment—characterized by the belief that “the environment is mine”—which then strengthens ecological awareness through both emotional and cognitive pathways, ultimately encouraging pro-environmental behavior. Within this process, environmental psychological ownership and ecological awareness function not only as independent mediators but also as sequentially linked variables, forming a chain-like mediation pathway. Together, they illustrate the layered mechanism through which the perception of ecological public art facilitates pro-environmental behavioral outcomes.

3. Research Framework and Hypothesis

3.1. Theoretical Framework and Variables

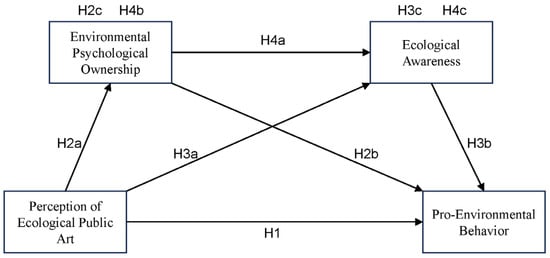

Building on the preceding literature review and analysis, this study constructs a multiple mediation model employing four key variables: perception of ecological public art, environmental psychological ownership, ecological awareness, and pro-environmental behavior (see Figure 1). To avoid confusion between the concepts of ecological and environmental, the terminology used in this study follows a clear distinction. The terms ecological public art and ecological awareness emphasize the relationships and interdependence among humans, society, and the natural environment, reflecting a broader ecological perspective that concerns human–nature coexistence. In contrast, the terms environmental psychological ownership and pro-environmental behavior highlight individuals’ sense of ownership and proactive behavioral tendencies toward their surrounding environment, including its biophysical, economic and social-cultural dimensions. This distinction aligns with usage in prior literature and ensures conceptual clarity in analyzing public cognition and behavioral mechanisms. Furthermore, this study draws on Epstein’s (1990) Cognitive-Experiential Self-Theory (CEST), which posits that human behavior is shaped through the joint operation of two systems: the experiential system, driven by emotion and characterized by rapid responses, and the rational system, driven by logical analysis and characterized by slower, deliberate processing []. In the context of this research, the influence of ecological public art on pro-environmental behavior is understood as a process that is unlikely to occur through a single pathway. Instead, it is hypothesized to involve the simultaneous and interactive functioning of both experiential and rational systems. Accordingly, the proposed research framework conceptualizes the pathway from ecological public art to pro-environmental behavior as progressing through four stages: perceptual stimulation, emotional intuition, cognitive elaboration, and behavioral transformation. Within this sequence, the transition from emotional intuition to cognitive elaboration corresponds to the dual mediation of environmental psychological ownership and ecological awareness. In the model, perception of ecological public art is specified as the independent variable, while pro-environmental behavior is the dependent variable.

Figure 1.

Proposed research model (Solid lines in the diagram represent hypothesized positive relationships. For example, H1a states that perception of ecological public art has a significant positive effect on pro-environmental behavior).

In this study, perception of ecological public art serves as the independent variable and the starting point of the entire model. It refers to the multi-dimensional perceptual experience that ecological public art offers to the public, encompassing aspects such as ecological themes, educational functions, esthetic form, and modes of interaction.

The model incorporates three primary transmission pathways:

- Following multi-dimensional perceptual stimulation, such as a strong visual impact generated by ecological warnings or an immersive environmental experience, it is hypothesized that the public will develop emotional intuition, experience a sense of resonance with environmental psychological ownership, and subsequently increase their engagement in pro-environmental behavior;

- Following multi-dimensional perceptual stimulation, for example, through the reception of environmental information and ecological education, it is hypothesized that the public will engage in cognitive elaboration, which strengthens ecological awareness and encourages the voluntary adoption of pro-environmental behavior;

- Following multi-dimensional perceptual stimulation, it is hypothesized that emotional intuition and cognitive elaboration will occur in sequence, with environmental psychological ownership and ecological awareness jointly influencing subsequent pro-environmental behavior.

Furthermore, based on preliminary investigations and a review of relevant literature, it is reasonably expected that the perception of ecological public art will exert a positive influence on pro-environmental behavior.

3.2. Hypotheses

The essence of artistic practice lies in the transmission of intersubjective relationships, which can continuously generate further relational extensions []. The core value of ecological public art resides in its public nature, which emphasizes the construction of a shared perceptual community. Through artistic intervention, it facilitates social interaction and reshapes the emotional connection between people and their environment. Public artworks in urban spaces that focus on environmental or ecological themes vividly present both the beauty of biodiversity and the fragility of the environment. By integrating ecological concepts into daily life, these artworks inspire public perception, reflection, and action on ecological issues. This process encompasses four interrelated dimensions—perception, psychology, awareness, and behavior—which correspond to the four variables in the multiple mediation model proposed earlier: perception of ecological public art, environmental psychological ownership, ecological awareness, and pro-environmental behavior.

3.2.1. Direct Relationship Between Perception of Ecological Public Art and Pro-Environmental Behavior

Based on the connotations, characteristics, and multifaceted functions of ecological public art in society, it is hypothesized that there is a direct and positive relationship between the perception of ecological public art and pro-environmental behavior:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Perception of ecological public art positively influences pro-environmental behavior.

3.2.2. Mediating Role of Environmental Psychological Ownership

Environmental psychological ownership reflects an individual’s sense of belonging and possession toward the environment. It is hypothesized that ecological public art, through multi-dimensional perceptual engagement, stimulates an emotional connection between the public and the environment, thereby strengthening environmental psychological ownership and ultimately promoting pro-environmental behavior.

Based on this reasoning, the following hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis 2a (H2a).

Perception of ecological public art positively influences environmental psychological ownership.

Hypothesis 2b (H2b).

Environmental psychological ownership positively influences pro-environmental behavior.

Hypothesis 2c (H2c).

Environmental psychological ownership mediates the relationship between perception of ecological public art and pro-environmental behavior.

3.2.3. Mediating Role of Ecological Awareness

Ecological awareness encompasses the depth of individuals’ understanding of ecological issues and their environmental values. It is hypothesized that the perception of ecological public art can directly enhance public understanding of ecological issues, which in turn influences pro-environmental behavior. Accordingly, the following hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis 3a (H3a).

Perception of ecological public art positively influences ecological awareness.

Hypothesis 3b (H3b).

Ecological awareness positively influences pro-environmental behavior.

Hypothesis 3c (H3c).

Ecological awareness mediates the relationship between perception of ecological public art and pro-environmental behavior.

3.2.4. Serial Mediation of Environmental Psychological Ownership and Ecological Awareness

Environmental psychological ownership and ecological awareness are proposed as key mediating variables that jointly form a chain mediation pathway between the perception of ecological public art and pro-environmental behavior. When individuals develop a strong perception of ecological public art, it may evoke an emotional response toward the environment and foster the belief that “the environment is mine”, thereby generating environmental psychological ownership. This ownership reflects an emotional connection and a sense of responsibility toward the environment. A strong sense of environmental psychological ownership is expected to enhance ecological cognition, thereby strengthening ecological awareness. Ultimately, this process encourages more active and voluntary engagement in pro-environmental behavior to protect the environment that is “owned” at a psychological level.

Based on this reasoning, the following hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis 4a (H4a).

Environmental psychological ownership positively influences ecological awareness.

Hypothesis 4b (H4b).

Environmental psychological ownership mediates the relationship between perception of ecological public art and ecological awareness.

Hypothesis 4c (H4c).

Ecological awareness mediates the relationship between environmental psychological ownership and pro-environmental behavior.

4. Research Case and Methods

4.1. Case Study

Since its inception, the SUSAS has maintained a focus on ecological themes, seeking to explore new pathways for the sustainable integration of art and urban space. The successful hosting of the 2010 Shanghai World Expo embedded the concept of “Better City, Better Life” into the city’s development trajectory and public consciousness, creating fertile ground for the emergence of SUSAS []. In 2015, Shanghai launched the inaugural edition of the Urban Space Art Season with the aim of revitalizing urban spaces through the power of art, thereby promoting organic urban renewal and sustainable development. Subsequent biennial editions have each adopted distinct thematic focuses, including “Connection: Public Space and Public Art”, “Encounter: Waterfront Public Space”, and “15-Min Community Life Circle”. In 2023, the event returned to an ecological theme under the title “Coexistence: A Community of Life”. This edition transformed urban spaces into exhibition sites, presenting a vision of urban renewal characterized by the harmonious coexistence of people and nature, while showcasing a diverse array of ecological public artworks [].

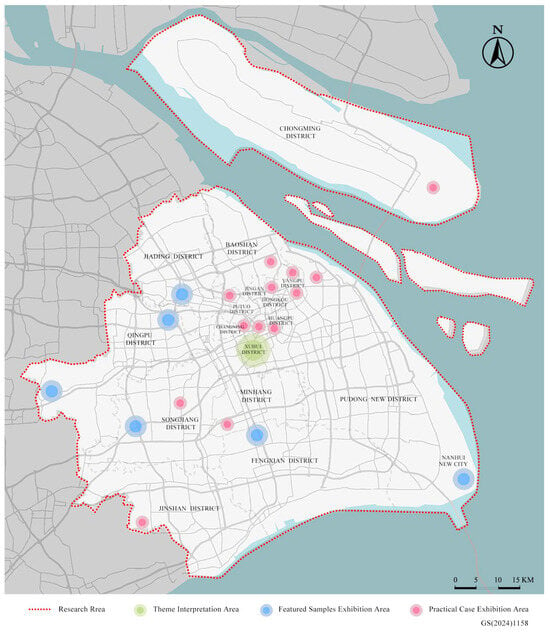

This study takes the 5th SUSAS as its case study, focusing on one thematic interpretation zone, six key sample exhibition zones, and thirteen practice-based exhibition zones as the primary research areas (see Figure 2). In consideration of the extended presence of art projects beyond the formal exhibition sites, the study scope was further expanded to encompass the entirety of Shanghai. This expansion is consistent with the core concept of the SUSAS, which positions the entire urban space as its exhibition venue.

Figure 2.

Case study area and locations of the main exhibition zones. (Source: Compiled by the researcher).

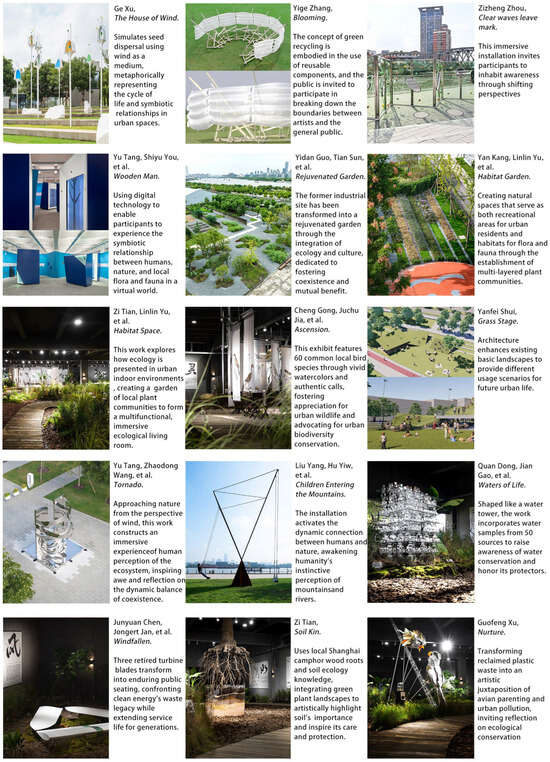

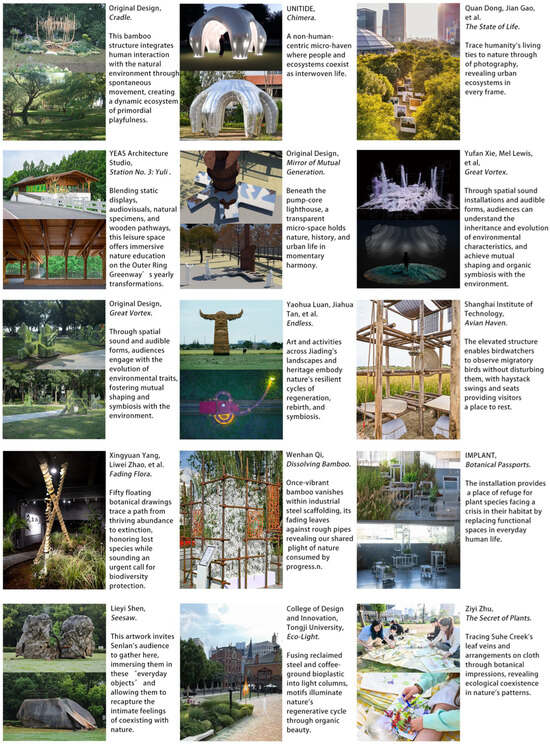

Within the defined research area, thirty representative ecological public art projects were selected as the primary research samples (see Figure 3). These works collectively encompass a wide range of forms, including ecological space exhibitions, ecosystem restoration initiatives, dissemination of ecological concepts, application of ecological materials, and ecological warnings. They engage the public through viewing, experiential interaction, and participatory activities, thereby fostering immersive involvement. For example, Feng Tu Shui Ling: Habitat Space, located in the thematic interpretation zone, visually presents the natural habitats and biodiversity stretching from the source of the Three Rivers to the banks of the Huangpu River. This installation enables the public to directly perceive the beauty of natural habitats. By incorporating tactile and olfactory elements, it creates a multisensory interactive experience that further enhances the perception of ecological public art, encouraging emotional connections with the environment and reflective thinking. Such perceptual experiences form the foundation for subsequent psychological and behavioral changes. Another example is The Secret of Plants, an ecological public art project that invited residents from surrounding communities to participate in co-creation. The artist introduced participants to knowledge about plant structures, including venation, phyllotaxis, and leaf margins. Using the hammer-printing technique, participants transferred the colors, contours, and textures of leaves and petals onto canvas bags. This process guided the public to perceive plant morphology and natural messages in a tangible way, deepening their understanding of natural esthetics and biodiversity through interactive participation, and thereby cultivating more profound ecological awareness. These ecological public art projects are considered representative within the scope of this study, as they effectively fulfill the key observational requirements for examining ecological public art perception.

Figure 3.

List and illustrations of ecological public art research samples (Source: SUSAS 2023 []).

4.2. Methods

Drawing on the literature on ecological public art and pro-environmental behavior, as well as findings from field investigations, this study theoretically proposes that ecological public art exerts a significant positive influence on pro-environmental behavior, with environmental psychological ownership and ecological awareness functioning as mediating variables. The proposed research framework is grounded in a multiple mediation model, designed to examine and compare three distinct pathways: the effect of environmental psychological ownership as a single mediator, the effect of ecological awareness as a single mediator, and the effect of environmental psychological ownership and ecological awareness operating together in a serial mediation. The aim is to systematically investigate whether there are significant and complex associations among perception of ecological public art, environmental psychological ownership, ecological awareness, and pro-environmental behavior. To test the proposed hypotheses, a questionnaire survey was conducted among residents of Shanghai and visitors to the city. Based on the survey data, a quantitative analysis was performed using SEM, supplemented by qualitative analysis of representative samples. This mixed-methods approach offers a new theoretical perspective for understanding the drivers of public pro-environmental behavior, while also providing an opportunity to further develop and refine the theoretical framework in this field.

4.3. Data Collection

Although the 5th SUSAS lasted only two months, from 26 September to 20 November 2023, a substantial portion of its outcomes remained in place after the exhibition ended. While some temporary public artworks were dismantled or relocated, a considerable number of permanent public artworks, renovated ecological landscapes, public facilities, and community micro-renewal projects were retained across various urban areas of Shanghai. As a result, the audience that encountered these works after the exhibition period was potentially much broader than the visitors during the official event. Based on this consideration, the present study defined the research sample to include both the visitors during the exhibition period and members of the public who may have engaged with the artworks after the exhibition. A total of 479 questionnaires were randomly distributed (including both paper-based surveys and online questionnaires), yielding 326 valid responses. The adequacy of the sample size was confirmed using Soper’s free online statistical calculator. Based on the research model, which includes 29 observed variables and 10 latent variables, the expected effect size was set at 0.3, the probability level at 0.05, and the desired statistical power at 0.8. The calculator determined that the minimum sample size required for detecting the hypothesized effects was 137, while the minimum sample size for model construction was 100; the recommended minimum sample size was therefore 137 []. The questionnaire consisted of two main sections. The first collected basic demographic information from respondents, while the second addressed four key constructs: perception of ecological public art, ecological awareness, environmental psychological ownership, and pro-environmental behavior. All items in the second (see Table A1) section were measured using a five-point Likert scale.

According to the statistical results from the basic information section of the questionnaire (see Table 1), the respondents were predominantly young and middle-aged individuals between 18 and 50 years old, accounting for 76.08% of the sample. Within this group, those aged 31–50 constituted 42.64%, and those aged 18–30 accounted for 33.44%. Respondents aged 51 and above represented 20.51%, while those under 18 comprised only 3.37%. This pattern indicates an age distribution that is concentrated within specific ranges yet diverse in composition. In terms of gender distribution, females accounted for 54.91%, slightly higher than males at 45.09%, reflecting an overall balanced ratio. Regarding occupational composition, company employees formed the largest group at 30.06%, followed by freelancers at 19.33%. Teachers and students together represented 26.38%, while the remaining respondents were distributed across multiple professional sectors, including finance, arts, media, and government, indicating a heterogeneous occupational structure. In terms of educational attainment, the majority of respondents (74.24%) held a bachelor’s degree or higher, suggesting a relatively high level of formal education within the sample. With respect to familiarity with ecological public art, 72.08% of respondents demonstrated varying degrees of understanding, whereas 27.91% reported limited familiarity, indicating potential for further public outreach and education initiatives. Regarding the 5th SUSAS, although 45.71% of respondents reported that they did not actively participate in the event, most resided within the activity area and were likely to have been exposed to, and benefited from, the ecological-themed urban renewal projects and public art installations created during the festival. This finding supports the methodological appropriateness of including this group in the study, while also highlighting the need to strengthen publicity coverage, public awareness, and participation motivation. Overall, the respondents demonstrated a reasonable distribution in terms of age, gender, occupation, educational background, and familiarity with ecological public art, suggesting that the survey sample possesses good representativeness.

Table 1.

Basic information of respondents.

5. Empirical Results

Structural equation modeling (SEM), which integrates confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and path analysis, was employed for data analysis using SPSS 26.0 and AMOS 24.0 software.

5.1. Variable Descriptive Analysis

The descriptive statistical analysis of the four constructs (see Table 2)—Perception of Ecological Public Art (PEPA), Environmental Psychological Ownership (EPO), Ecological Awareness (EA), and Pro-Environmental Behavior (PEB)—indicates that all measured values fall within the range of 1.000 to 5.000, suggesting a reasonable data distribution. In terms of mean values, environmental psychological ownership (4.077) and ecological awareness (4.101) are slightly higher than perceived ecological public art (3.875) and pro-environmental behavior (4.015), reflecting a relatively higher level of agreement among respondents regarding their sense of psychological ownership and ecological awareness. The standard deviation results show that perceived ecological public art has the largest standard deviation (0.776), indicating greater individual variation in this construct and suggesting diversity in respondents’ perceptions and experiences of ecological public art. In contrast, ecological awareness has the smallest standard deviation (0.714), which suggests more concentrated evaluations and a relatively consistent attitude among respondents toward ecological awareness.

Table 2.

Basic indicators.

5.2. Reliability and Validity Testing and Factor Analysis

This study conducted internal consistency tests on the four dimensions of Perception of Ecological Public Art, Environmental Psychological Ownership, Ecological Awareness, and Pro-Environmental Behavior. The results indicated that (see Table 3) the Cronbach’s α coefficients for all dimensions were at a high level, ranging from 0.871 to 0.911, demonstrating good reliability of the measurement scale []. Among these, Pro-Environmental Behavior exhibited the highest coefficient (0.911), reflecting excellent reliability in measuring the public’s willingness and frequency of actual participation in environmental protection activities. Environmental Psychological Ownership (0.890) and Perception of Ecological Public Art (0.878) also showed high internal consistency, while Ecological Awareness (0.871) likewise demonstrated stable measurement capability. In general, the internal consistency across all dimensions was strong, providing robust data support for the subsequent SEM analysis.

Table 3.

Cronbach’s alpha.

Building on the satisfactory reliability results, this study proceeded with validity testing (see Table 4). First, the suitability of the data for factor analysis was assessed using the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure and Bartlett’s test of sphericity. The KMO value was 0.912, which is substantially higher than the commonly accepted threshold of 0.6. Bartlett’s test result was significant (χ2 = 3955.138, df = 190, p < 0.001) [], indicating sufficient correlations among variables and confirming that the sample was appropriate for factor analysis.

Table 4.

KMO and Bartlett’s Test.

Subsequently, principal component analysis was conducted (see Table 5). The results extracted four factors with eigenvalues greater than 1, accounting for a cumulative variance explanation rate of 70.113%, indicating that the extracted factors effectively explained the majority of the data variance. The eigenvalues and corresponding variance contribution rates for the four factors were 7.346 (36.728%), 2.607 (13.036%), 2.193 (10.967%), and 1.876 (9.382%), respectively, together forming a comprehensive explanatory framework. After applying Varimax rotation, the variance explanation rates of the factors became more balanced at 18.329%, 17.669%, 17.337%, and 16.778%, respectively, resulting in a clearer and more interpretable factor structure.

Table 5.

Variance explained by factors.

To further verify the construct validity of the measurement model (see Table 6), this study analyzed the standardized factor loadings, average variance extracted (AVE), and composite reliability (CR) for the four dimensions: Perception of Ecological Public Art, Environmental Psychological Ownership, Ecological Awareness, and Pro-Environmental Behavior. These analyses were conducted to examine the convergent validity and internal consistency of each latent variable. The results indicated that the standardized factor loadings for all latent variables exceeded 0.50, with most values above 0.70, suggesting a strong association between the measurement items and their corresponding constructs. The AVE values ranged from 0.586 to 0.678, and the CR values ranged from 0.874 to 0.913. Both sets of values were above the commonly accepted thresholds (AVE > 0.50 and CR > 0.70) [], thereby confirming that the scale possessed satisfactory convergent validity and internal consistency. Although a few measurement items—such as item C1 in the Ecological Awareness dimension—exhibited slightly lower factor loadings compared with other items, the overall model structure was found to be reasonable.

Table 6.

Factor loadings, AVE, and CR.

The discriminant validity test was conducted based on the Fornell–Larcker criterion []. The results indicated that (see Table 7) the square root of the AVE for each latent variable was greater than its correlations with other latent variables. For example, the square root of the AVE for PEPA was 0.783, which exceeded its correlations with EPO (0.250), EA (0.331), and PEB (0.417). The same pattern was observed for the other latent variables. These results demonstrate that although the four latent variables were positively correlated to some extent, they possessed sufficient distinctiveness from one another, enabling them to measure their respective psychological or behavioral constructs independently and effectively. This finding confirms the good discriminant validity of the scale. In summary, the scale demonstrated satisfactory reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity, and the measurement model was fully validated, thereby providing robust data support for the subsequent structural equation modeling analysis.

Table 7.

Discriminant validity: Pearson correlation and AVE square root value.

5.3. Correlation Analysis

The results of the Pearson correlation analysis indicate that (see Table 8) there are significant positive correlations (p < 0.01) among the four dimensions—perception of ecological public art, environmental psychological ownership, ecological awareness, and pro-environmental behavior. Specifically, perception of ecological public art is positively correlated with environmental psychological ownership (r = 0.250), ecological awareness (r = 0.331), and pro-environmental behavior (r = 0.417), suggesting that the perception of ecological public art plays a role in enhancing ecological awareness and pro-environmental behavior, with a relatively stronger influence on the latter. Environmental psychological ownership exhibits stronger correlations with ecological awareness (r = 0.329) and pro-environmental behavior (r = 0.423), indicating its pivotal role in fostering pro-environmental behavior. The correlation coefficient between ecological awareness and pro-environmental behavior is 0.420, also reflecting a strong positive association. Overall, these findings confirm the positive impacts of ecological public art perception, environmental psychological ownership, and ecological awareness on pro-environmental behavior, with environmental psychological ownership playing a particularly critical role in this process.

Table 8.

Pearson correlation.

5.4. Path Analysis

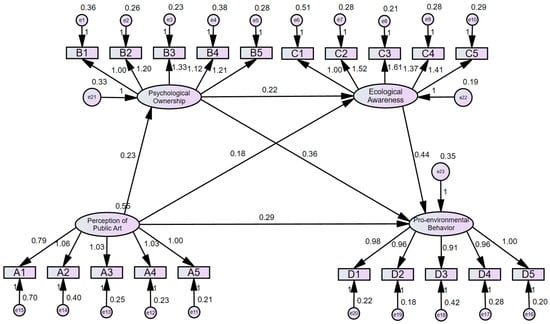

The fit indices of the structural equation model indicate that (see Figure 4 and Table 9) the overall model fit is satisfactory. The chi-square value (χ2) is 209.135, with 164 degrees of freedom (df) and a p-value of 0.010. The chi-square to degrees of freedom ratio (χ2/df) is 1.275, which is below the recommended threshold of 3, suggesting a good fit between the model and the data. All absolute fit indices meet the recommended criteria. The Goodness of Fit Index (GFI) is 0.941 and the Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index (AGFI) is 0.925, both exceeding the 0.90 benchmark, indicating strong overall model adequacy. The Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) is 0.029, with a 90% confidence interval between 0.015 and 0.040, well within the ideal range (<0.05), demonstrating minimal discrepancy between the model and the data. The Root Mean Square Residual (RMR) is 0.031 and the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) is 0.038, both lower than their respective thresholds (RMR < 0.05; SRMR < 0.08), further confirming low residuals and good model fit. Regarding incremental fit indices, the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) is 0.988, the Normed Fit Index (NFI) is 0.949, the Non-Normed Fit Index (NNFI) and the Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI) are both 0.986, and the Incremental Fit Index (IFI) is 0.988. All values exceed the recommended threshold of 0.90, indicating substantial improvement over the baseline model and an overall excellent fit.

Figure 4.

Path analysis diagram. (The arrows represent the direction of influence or causality between variables).

Table 9.

Model fit index.

In the structural equation model, the regression relationships among variables indicate the strength of the causal pathways between them (see Table 10). The results demonstrate significant causal relationships among ecological public art perception, environmental psychological ownership, ecological awareness, and pro-environmental behavior, with all path coefficients reaching statistical significance (p < 0.001). Specifically, ecological public art perception exerts a positive influence on environmental psychological ownership, ecological awareness, and pro-environmental behavior. The standardized regression coefficient from ecological public art perception to environmental psychological ownership is 0.281, indicating that a one standard deviation increase in ecological public art perception corresponds to a 0.281 standard deviation increase in environmental psychological ownership. Similarly, ecological public art perception has significant positive effects on ecological awareness (β = 0.281) and pro-environmental behavior (β = 0.281), with the direct impact on pro-environmental behavior being relatively stronger. Environmental psychological ownership shows significant positive effects on both ecological awareness (β = 0.280) and pro-environmental behavior (β = 0.285). Among all paths, its influence on pro-environmental behavior is the most pronounced, underscoring the pivotal role of environmental psychological ownership in promoting public environmental protection behaviors. Ecological awareness has a standardized regression coefficient of 0.281 for pro-environmental behavior, also indicating a stable positive effect.

Table 10.

Summary of model regression coefficients.

Ecological public art perception not only directly promotes pro-environmental behavior but also exerts indirect effects through environmental psychological ownership and ecological awareness (see Table 11). Environmental psychological ownership plays an important mediating role in the model, while ecological awareness further enhances the impact on pro-environmental behavior. These findings reveal the internal pathways through which ecological public art influences pro-environmental behavior via multidimensional psychological mechanisms, providing empirical support for theoretical development and practical applications in the relevant field.

Table 11.

Indirect effects analysis.

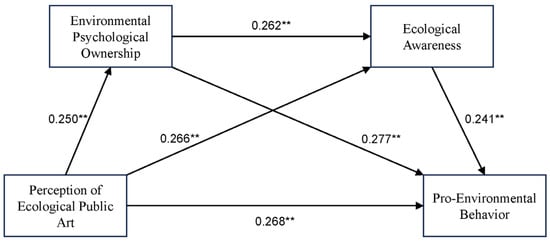

5.5. Mediation Effect Test

The mediation analysis results indicate that (see Figure 5 and Table 12) the influence of Ecological Public Art Perception on Pro-environmental Behavior is realized not only through a direct path but also through indirect paths mediated by Environmental Psychological Ownership and Ecological Awareness. Specifically, the indirect effect of Ecological Public Art Perception on Pro-environmental Behavior through Environmental Psychological Ownership is 0.068, with a bootstrap standard error of 0.024, a 95% confidence interval of [0.028, 0.121], a z-value of 2.885, and a p-value of 0.004, indicating a significant effect. The indirect effect through Ecological Awareness is 0.063, with a bootstrap standard error of 0.023, a 95% confidence interval of [0.026, 0.114], a z-value of 2.775, and a p-value of 0.006, also reaching statistical significance. In addition, the chain mediation effect, in which Ecological Public Art Perception influences Pro-environmental Behavior through Environmental Psychological Ownership followed by Ecological Awareness, shows an indirect effect of 0.016, with a bootstrap standard error of 0.006, a 95% confidence interval of [0.006, 0.030], a z-value of 2.542, and a p-value of 0.011, confirming its significance. Overall, Environmental Psychological Ownership and Ecological Awareness play critical mediating roles in the relationship between Ecological Public Art Perception and Pro-environmental Behavior, and the chain mediation effect further reveals the joint mechanism of these two variables, enhancing the explanatory power of the model.

Figure 5.

Mediation analysis of ecological public art perception, environmental psychological ownership, ecological awareness, and pro-environmental behavior (arrows indicate causal paths; ** denotes that the coefficient is statistically significant at the 0.01 level).

Table 12.

Mediation model test.

The mediation model test results (see Table 12) further confirmed the relationships among the variables and their paths of influence. In the environmental psychological ownership model, the regression coefficient of ecological public art perception on environmental psychological ownership was 0.241 (t = 4.647, p < 0.01), and the regression coefficient of environmental psychological ownership on pro-environmental behavior was 0.284 (t = 5.660, p < 0.01), indicating that environmental psychological ownership plays a significant mediating role in the relationship between ecological public art perception and pro-environmental behavior. In the ecological awareness model, the regression coefficient of ecological public art perception on ecological awareness was 0.245 (t = 5.092, p < 0.01), and the regression coefficient of ecological awareness on pro-environmental behavior was 0.258 (t = 4.791, p < 0.01), also confirming the mediating effect of ecological awareness. In addition, the model examined the serial mediation effect of environmental psychological ownership and ecological awareness. The results showed that this path further enhanced the explanatory power for pro-environmental behavior, highlighting the importance of the interaction between the two mediators. In terms of explanatory power, the R2 of the environmental psychological ownership model was 0.062, indicating that ecological public art perception explains 6.2% of the variance in environmental psychological ownership. The R2 of the ecological awareness model was 0.174, showing that ecological public art perception and environmental psychological ownership together explain 17.4% of the variance in ecological awareness. The R2 of the pro-environmental behavior model was 0.330, indicating that ecological public art perception, environmental psychological ownership, and ecological awareness together explain 33.0% of the variance in pro-environmental behavior. These findings demonstrate that environmental psychological ownership and ecological awareness serve as key mediators in the pathway through which ecological public art perception influences pro-environmental behavior, and that the serial mediation path effectively enhances the model’s explanatory power, further validating the robustness and theoretical soundness of the model structure.

6. Discussion and Prospects

6.1. Research Findings and Reflections

The study finds that the impact of ecological public art perception on public pro-environmental behavior occurs through multiple pathways. These include a direct pathway from ecological public art perception to pro-environmental behavior, a single mediation pathway from ecological public art perception through environmental psychological ownership to pro-environmental behavior, another single mediation pathway from ecological public art perception through ecological awareness to pro-environmental behavior, and a sequential mediation pathway from ecological public art perception through environmental psychological ownership and then ecological awareness to pro-environmental behavior. These findings are supported by literature review, model construction, and structural equation modeling, revealing that ecological public art influences public pro-environmental behavior through a multidimensional psychological transmission process involving perception activation, emotional identification, cognitive deepening, and behavioral transformation. Furthermore, during the questionnaire collection phase, real feedback from residents provided more detailed insights into the specific perception process and the subsequent psychological impact. For example, respondents reported that when viewing Urban Breathing, a public artwork transformed from a decommissioned dust removal tower (previously responsible for one-seventh of Shanghai’s dust emissions), the rebirth of this industrial relic evoked a strong visual impact and a sense of contradiction. Particularly striking was the installation of an air quality monitor at the original dust outlet, which used LED light art to display real-time PM2.5 readings. This enabled them to perceive the improvement in their environment and, conversely, to feel heightened anxiety when the readings increased. Such experiences deepened their awareness of ecological issues and the urgency of environmental protection, making them more inclined to choose pro-environmental behaviors in their daily lives to alleviate environmental anxiety. This finding aligns with Sommer’s argument that “engagement with immersive activist art enhances willingness to take action on pollution and climate change” [], Curtis’s view on “using art to raise awareness and communicate environmental messages” [], and other scholars’ perspectives on how art fosters ecological empathy and conveys ecological knowledge [,]. However, unlike previous studies, this research is the first to deconstruct the influence pathway of ecological public art on public pro-environmental behavior by identifying environmental psychological ownership and ecological awareness as key mediators to observe both direct and indirect effects. It further distinguishes between single and serial mediation effects, confirming their validity and offering a new perspective on understanding the positive impact of ecological public art perception on public pro-environmental behavior.

Reflecting on the research process, although the data confirmed that ecological public art can promote pro-environmental behavior and verified the mediating effects of environmental psychological ownership and ecological awareness, the analysis also revealed that the serial mediation pathway, from environmental psychological ownership to ecological awareness and subsequently to pro-environmental behavior, exhibited a relatively weaker effect compared with the two single mediation paths. This suggests that the transformation from emotional ownership to cognitive awareness may not occur immediately but rather requires continuous reinforcement through education or participatory engagement. Such a finding highlights the complexity of cognitive conversion in the process of ecological perception and underscores that affective and cognitive mechanisms may operate at different temporal or contextual levels. Therefore, the difficulty of monitoring actual behaviors over the long-term limited the study. The behavioral impacts discussed here mainly refer to the promotion of behavioral intention at the psychological level. In addition, participatory observation and field investigation revealed that some artworks addressing ecological themes suffered from poor visual-sensory coherence or unclear information delivery, which in turn reduced the effectiveness of public perception. Thus, future research should incorporate long-term behavioral monitoring and more targeted investigations into how ecological public art transmits perception in order to enrich and complement the present findings.

6.2. Prospects and Recommendations

Based on the case study of the 5th SUSAS and the analysis of the serial multiple mediation model, this study reveals the mechanism through which ecological public art promotes pro-environmental behavior by enhancing public perception and activating environmental psychological ownership and ecological awareness. The findings indicate that emotional resonance and cognitive deepening are the key transmission links in this process, while interactive and technology-enabled design strategies can effectively amplify these effects.

On this basis, the following prospects and recommendations are proposed:

- Sensory synergy: Strengthening ecological perception through visual and interactive experiences. Future ecological public art should move beyond the traditional visually dominated paradigm by integrating multi-sensory elements such as sound, touch, and dynamic imagery. The incorporation of real-time environmental data and digital technologies such as AR and VR can create immersive and responsive ecological information experiences (e.g., Urban Breathing). By transforming complex ecological issues into tangible scenarios, these approaches can help the public better understand the severity of environmental problems, stimulate active reflection on ecological issues, and deepen cognition, thereby fostering the transition to pro-environmental behavior.

- Emotional storytelling: From emotional resonance to cognitive deepening. The organic integration of ecological warning and ecological education, supported by emotional storytelling techniques such as interactive participation and visual metaphors, can effectively facilitate the transformation from affective experience to rational cognition. For example, The Secret of Plants uses the ecological characteristics of plants as its narrative thread. Through participatory activities such as botanical fabric printing, the public engages in an embodied interaction that fosters an appreciation of natural esthetics and cultivates emotional resonance with nature. During this process, the artist’s interpretation of ecological information about plants transforms this emotional resonance into a rational understanding of human–nature symbiosis. Future public art projects should emphasize the combination of narrative and participation in order to realize a sequential pathway that links emotion, cognition, and behavior.

- Practice extension: Cultivating long-term pro-environmental behavior. The short-term interactions of urban space art events should be linked with the long-term development of communities. From the perspective of fostering long-term pro-environmental behavior among community residents, the Urban Space Art Season has effectively expanded the practice venues of ecological public art within communities. Through a series of offline co-creation workshops, such as Waste Transformation Workshops and Community Garden Co-building, residents were encouraged to create installation artworks using discarded clothing, thereby conveying the ecological concept of material recycling. Initiatives such as composting kitchen waste to cultivate shared green spaces and small vegetable gardens turned artistic creation into a hands-on classroom for practicing environmental responsibility, deepening residents’ sense of environmental psychological ownership. By promoting a multidimensional mode of artistic participation that facilitates the transformation from emotional resonance to cognitive engagement, the program demonstrates the potential to convert short-term interactions during the Art Season into sustained, everyday pro-environmental behaviors within the community. From the perspective of policy guidance, governmental support, and stakeholder collaboration, the ecological theme of the Urban Space Art Season serves as a platform linking urban planning departments, universities, and enterprises. The outcomes have been integrated with existing municipal policies and plans, such as the Shanghai Urban Regeneration Action Plan and the 15-Minute Community Life Circle Action Plan, to develop urban ecological education bases and spatial design guidelines that provide concrete contexts for cultivating pro-environmental behavior. In alignment with Shanghai’s 15-Minute Community Life Circle framework, the collaboration between the Art Season, community organizations, and planning authorities incorporates interactive participation models into community ecological infrastructure standards. For example, by adding ecological public art installations in neighborhood parks. This approach transforms temporary artistic practices into long-term mechanisms for nurturing public environmental awareness and action. Moreover, by leveraging the brand influence of the Urban Space Art Season to promote an integrated model that combines ecological public art with cultural and tourism development, cities can not only enhance their ecological image but also encourage green mobility, low-carbon consumption, and other forms of pro-environmental behavior through experiential and participatory cultural engagement.

The findings demonstrate that ecological public art holds significant potential for promoting pro-environmental behavior. Future efforts should focus on multi-sensory technological innovation, emotional storytelling strategies, community-based practice extension, and multi-stakeholder collaborative governance, thereby achieving a deep transformation from artistic intervention to the cultivation of social behavior. Such an approach can contribute meaningfully to urban ecological civilization and sustainable development. This study not only offers urban planners a new pathway to integrate public art approaches into ecological design and community co-construction, but also provides educators with pedagogical insights into combining artistic experience with environmental education. At the same time, it offers policymakers a transferable model of social participation and cultural transformation for developing green city and community initiatives.

7. Conclusions

This study constructs a theoretical model in which ecological public art perception serves as the independent variable, environmental psychological ownership and ecological awareness function as mediating variables, and public pro-environmental behavior is the dependent variable. The model systematically reveals the internal mechanisms and pathways through which ecological public art perception positively influences public pro-environmental behavior. At the theoretical level, it explicates in detail the realization pathway of the positive influence of ecological public art perception on public pro-environmental behavior. Based on the theoretical attributes of ecological public art and the from affective intuition to cognitive deepening model of Cognitive–Experiential Self-Theory (CEST), it analyzes how a multidimensional perception system can synergistically promote the single mediation effects of environmental psychological ownership and ecological awareness, as well as their sequential mediation effect. Empirical results indicate that ecological public art has a positive impact on public pro-environmental behavior, and that environmental psychological ownership and ecological awareness exert positive mediating effects in this process. Specifically, enhancing ecological public art perception, stimulating environmental psychological ownership, and deepening ecological awareness can positively influence public pro-environmental behavior. Furthermore, by adopting a progressive logic encompassing sensory synergy, emotional–cognitive transformation, and practical extension, the study develops a strategic system that covers perception, psychology, and behavior. This framework aims to strengthen, through multidimensional interventions, the transmission pathway by which ecological public art positively affects public pro-environmental behavior.

Future research can be extended in several directions. First, building on this study, further differentiation of the dimensions of ecological public art perception is needed to analyze more precisely how ecological public art conveys information to the public and how the public interprets and internalizes these messages to generate perceptual feedback. Second, more emphasis should be placed on monitoring actual pro-environmental behaviors, particularly within a certain period after exposure to ecological public art, to track both short-term psychological shifts and long-term behavioral changes. Third, comparative studies across different sociocultural contexts would provide valuable insights into how cultural differences, community involvement, and policy frameworks influence public perception, emotional engagement, and behavioral responses to ecological public art, thereby testing the universality and contextual adaptability of the proposed model. Finally, with the rapid advancement of digital technologies such as digital twins, VR/AR, and AI, future research should explore how digital and immersive art methodologies, including interactive sensing, virtual participation, and real-time environmental feedback, can further mediate the relationship between perception, awareness, and ecological behavior in diverse urban and cultural settings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.Z.; methodology, S.Z. and R.T.; software, R.T.; validation, R.T., Y.S. and D.W.; formal analysis, R.T. and Y.S.; investigation, S.Z., R.T., Y.S. and D.W.; resources, S.Z.; data curation, S.Z. and R.T.; writing—original draft preparation, R.T. and Y.S.; writing—review and editing, S.Z. and R.T.; visualization, R.T. and D.W.; supervision, S.Z.; project administration, S.Z. and R.T.; funding acquisition, S.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the Art Project of the National Social Science Foundation [No. 18BG116].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the requirements of our institution’s ethics approval documents, only studies involving human life sciences, medical research, or animal experiments require ethical approval. As our research does not fall into these categories, we determined that ethics approval was not necessary.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SUSAS | Shanghai Urban Space Art Season |

| SEM | Structural Equation Modeling |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| NAM | Norm Activation Model |

| VBN | Value-Belief-Norm |

| GEB | General Ecological Behavior |

| CEST | Cognitive-Experiential Self-Theory |

| PEPA | Ecological Public Art |

| EPO | Environmental Psychological Ownership |

| EA | Ecological Awareness |

| PEB | Pro-Environmental Behavior |

| KMO | Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin |

| AVE | Average Variance Extracted |

| CR | Composite Reliability |

| GFI | Goodness of Fit Index |

| AGFI | Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index |

| RMSEA | Root Mean Square Error of Approximation |

| RMR | Root Mean Square Residual |

| SRMR | Standardized Root Mean Square Residual |

| CFI | Comparative Fit Index |

| NFI | Normed Fit Index |

| NNFI | Non-Normed Fit Index |

| TLI | Tucker–Lewis Index |

| IFI | Incremental Fit Index |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Measurement dimensions, codes, and statements corresponding to each variable.

Table A1.

Measurement dimensions, codes, and statements corresponding to each variable.

| Dimensions | Codes | Statements |

|---|---|---|

| Perception of Ecological Public Art | A1 | Ecological public artworks make me directly perceive the consequences of environmental damage (e.g., climate change, species extinction). |

| A2 | Through interactive ecological artworks (e.g., touchable installations, AR experiences), I gain a deeper understanding of the necessity of environmental actions. | |

| A3 | The visual design of ecological public art (e.g., use of recycled materials, natural elements) inspires me to reflect on environmental issues. | |

| A4 | Participating in ecological art activities (e.g., community co-creation, environmental-themed exhibitions) increases my willingness to practice environmental protection in daily life. | |

| A5 | Ecological artworks in public spaces make me aware of how personal behaviors affect the environment (e.g., waste disposal, energy consumption). | |

| Environmental Psychological Ownership | B1 | When I see natural environments being damaged, I feel as if “my own home” has been harmed. |

| B2 | I believe protecting the surrounding public environment (e.g., community parks, streets) is my personal responsibility. | |

| B3 | When others damage the environment, I feel a sense of responsibility to protect it because “this is my environment.” | |

| B4 | Even without supervision, I am willing to voluntarily maintain the cleanliness of public spaces (e.g., picking up litter, preventing pollution). | |

| B5 | I have a strong sense of belonging and desire to protect the environment where I have lived for a long time (e.g., my neighborhood, frequently visited parks). | |

| Ecological Awareness | C1 | I regularly follow news reports about environmental issues. |

| C2 | I believe climate change is a serious global problem. | |

| C3 | I believe humans should respect the laws of nature rather than trying to fully control it. | |

| C4 | I believe protecting biodiversity is very important. | |

| C5 | I believe personal environmental behaviors reflect the fulfillment of ecological ethical responsibilities. | |

| Pro-Environmental Behavior | D1 | I actively choose to use energy-saving appliances. |

| D2 | I try to minimize the use of disposable plastic products. | |

| D3 | I prefer walking, cycling, or using public transportation for travel. | |

| D4 | I participate in waste sorting and recycling activities. | |

| D5 | I purchase products with eco-friendly labels. |

References

- United Nations. The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2025. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2025/The-Sustainable-Development-Goals-Report-2025.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Chapin, F.S., III; Kofinas, G.P.; Folke, C.; Chapin, M.C. Principles of Ecosystem Stewardship: Resilience-Based Natural Resource Management in a Changing World; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Belfiore, E.; Bennett, O. Rethinking the Social Impact of the Arts: A Critical-Historical Review; Centre for Cultural Policy Studies, University of Warwick: Coventry, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bonyhady, T. The Colonial Earth; Melbourne University Publishing: Melbourne, Australia, 2003; Volume 34. [Google Scholar]

- Gablik, S. Connective aesthetics: Art after individualism. In Mapping the Terrain: New Genre Public Art; Bay Press: Seattle, WA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]