Abstract

Deforestation and forest degradation in the Brazilian Amazon remain critical threats to ecosystem integrity and local livelihoods. Existing approaches often overlook the nuanced perspectives of different regional actors, limiting our understanding of deforestation drivers and conservation policy effectiveness. This study compared perceptions of deforestation drivers and policy instruments between two major development hubs, Porto Velho and Manaus, using Likert-scale questionnaires administered to 49 villagers and 27 experts. Villagers across both areas identified Natural Disasters (RII = 0.79) and Forest Fires (RII = 0.63) as the most influential drivers, with these ranking particularly high in Porto Velho. Contrastingly, Cattle Ranching Expansion (RII = 0.89) and Political Intervention (RII = 0.86) were prominent in Porto Velho, while Forest Fires (RII = 0.84) and Illegal Logging (RII = 0.73) dominated in Manaus, highlighting distinct governance and economic priorities. Experts and locals both highlighted strong connections between agricultural expansion, land tenure insecurity, and policy deficiency. Conservation units (RII = 0.95) were considered the most important policy instrument according to experts in both areas and governance levels. These results highlight the need for context-specific, participatory solutions tailored to regional realities in Amazonian forest management.

1. Introduction

The ongoing deforestation and forest degradation (D&D) in the Amazon Rainforest threaten its ecological integrity and the livelihoods of millions who depend on it. Although attempts to stop deforestation have had varying degrees of effectiveness, the overall trajectory remains one of forest loss, driven by complex socioeconomic and political factors [1]. Addressing this challenge requires a deep insight into local contexts and the integration of diverse perspectives, particularly those of indigenous and local communities who have sustainably managed forests for generations and depend on them for their livelihood and survival.

Factors driving D&D in the Amazon are diverse and vary across subregions. While agricultural expansion, particularly cattle ranching and crop plantations, remains the primary cause of forest loss in many areas of the Amazon [2,3], other factors such as infrastructure development and land speculation also play significant roles [4,5,6].

Forest conservation policies in the Amazon have evolved over time, with varying degrees of success. Protected areas and indigenous territories have proven effective in reducing deforestation rates in various parts of the Amazon [7,8,9]. Market-based mechanisms like REDD+ (reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation in developing countries and the role of conservation, sustainable management of forests, and enhancement of forest carbon stocks) and forest certification schemes have shown promise but face implementation challenges in the region. More recently, there has been growing recognition of the need to develop a sustainable bioeconomy that values standing forests and supports local livelihoods [10]. However, the success of these policies often depends on their alignment with local realities and the active participation of forest communities.

Therefore, the comparison between different areas within the Brazilian Amazon, such as the targeted areas in this study, is crucial for understanding the complex relationship between deforestation drivers and conservation policies. This approach recognizes that the Amazon is a diverse landscape with varying ecological, social, and economic conditions [11], and by examining distinct regions, we can identify how drivers of D&D vary spatially and temporally, leading to more complete and effective conservation strategies. Moreover, comparing different areas allows for the evaluation of policy effectiveness across diverse contexts, as a policy that works in one region may not be as effective in another.

This study utilizes the Likert scale, a psychometric rating instrument that requires respondents to rate how much they agree or disagree with a set of statements in order to objectively measure their opinions, attitudes, or behaviors [12]. It is widely used in survey research across many fields to transform qualitative perceptions into quantitative data. In environmental research, this instrument is used to evaluate public attitudes, perceptions, and concerns about environmental issues, policies, and management [13,14,15]. By offering a methodical and measurable approach to gathering points of view, Likert scales make them suitable for cross-level comparisons and context-specific studies.

While previous studies have assessed local perceptions of deforestation in the Amazon, these have typically focused on deforestation related to single drivers [16,17], contributions of specific conservation policies [18,19,20] or climate change impacts on livelihoods [21,22]. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, no prior research has been conducted in the Brazilian Amazon to identify what is driving deforestation and the policy instruments designed to combat it by providing a comparative, multi-level analysis integrating both local and expert perspectives across multiple jurisdictions and distinct local contexts. This approach enables a broader and more nuanced understanding of forest governance, capturing how perceptions and priorities differ across space and stakeholder type.

The inclusion of local perspectives in forest management is not just ethically important but also practically beneficial, as these communities possess a deep ecological knowledge developed over centuries. According to Chaves et al. [23], public policies in the Amazon often conflict with the interests and demands of large segments of the Amazonian population, given that they have always been justified on the grounds of needing to ‘develop’ and ‘integrate’ the region into the country’s dynamic centers and the international economy. Moreover, as the stewards of the forest, these communities are often best positioned to implement and monitor sustainable practices [24]. Therefore, their involvement can enhance the effectiveness and legitimacy of conservation efforts. Although this study directly assesses the influence of drivers and policy instruments in forest areas through local perceptions, integrating local perspectives into broader management frameworks remains challenging.

The originality of this study lies in its cross-regional and multi-level analysis of local and expert perceptions regarding both deforestation drivers and effectiveness of conservation policies. By comparing two important development hubs in the Brazilian Amazon—Manaus and Porto Velho—and incorporating different governance levels, this research offers insights into how local realities influence both pressures on forests and effectiveness of conservation efforts. The two areas were chosen for this study because they represent different stages of development and deforestation pressures in the region. This approach makes an important contribution to the literature and provides practical guidance for designing policies that are focused on local needs and adaptable to varied conditions across the Amazon.

To provide a comprehensive analysis of the influence of drivers of D&D and the policy instruments designed to combat it, this study seeks to: (1) identify the most significant drivers of deforestation and policy instruments of conservation collected by Likert-scale questionnaire; (2) compare perceptions of drivers and policy influence between Manaus and Porto Velho; (3) examine potential differences in perceptions across national, regional, and local governance (spatial) levels; and (4) investigate relationships between various drivers and policies.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows: Section 2 describes the study areas, participant sampling, and analytical methods. Section 3 reports principal findings on driver and policy perceptions. Section 4 presents the discussion, including limitations and implications for Amazonian conservation policy. Section 5 concludes the paper with recommendations for future research and practice.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Areas

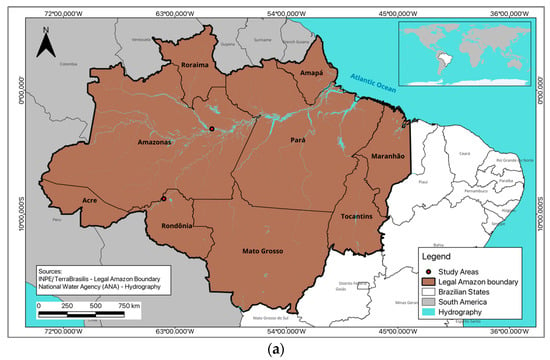

The Brazilian Amazon rainforest is located in the northern region of Brazil and covers the territory of 9 states (Figure 1a). It experiences a tropical climate (A-Zone in the Köppen classification) with average temperature in the coldest month exceeding 20 °C in the center of the Amazon Basin. Rainfall can reach over 3000 mm annually, and in some areas, it may even exceed 8000 mm. It covers approximately 5 million km2, or 59% of Brazil’s territory [25], and it is home to over 28 million people, including indigenous communities, traditional riverside populations, and urban residents [26]. This study was conducted in the cities of Manaus, capital of the Amazonas state, and Porto Velho District, located in the capital of the Rondônia state, Porto Velho.

Figure 1.

Location of study areas inside the (a) Brazilian Amazon region: (b) Manaus and (c) Porto Velho true color maps.

Manaus is the capital city of Amazonas state (Figure 1b), and its area encompasses the urban area and its surrounding forest, covering approximately 1,142,000 ha [26]. Manaus is situated in the heart of the Brazilian Amazon. It is a major urban center with a population exceeding two million people. The area’s location at the confluence of the Negro and Solimões rivers makes it a critical hub for transportation and commerce. Manaus has experienced rapid urban expansion, leading to increased pressure on surrounding forested areas.

The district of Porto Velho (Figure 1c), within the municipality of Porto Velho, capital of Rondônia state, is located on the east bank of the Madeira River in the southwestern part of the Brazilian Amazon. The area encompasses the urban area and its environs, spanning approximately 923,000 ha [26]. Unlike Manaus, Porto Velho has a strong reliance on agriculture and livestock farming. The construction of major infrastructure projects, such as highways and hydroelectric dams, has contributed to deforestation in the region. The district area of Porto Velho was chosen for this study, rather than the entire municipality, due to logistical and computational constraints. The district represents an important region of the Madeira River basin (Médio Madeira). Additionally, it houses the urban administrative hub of the municipality and is comparable in size to Manaus, allowing for a more balanced comparison.

These cities were selected for this study because they illustrate contrasting stages of economic development, urbanization, and deforestation pressures, offering valuable insights into the spectrum of challenges faced across the region. Manaus represents a longstanding urban and industrial center, characterized by a complex interplay of conservation priorities, urban expansion, and regional commerce. In contrast, Porto Velho lies in a frontier zone typified by more recent and rapid agricultural expansion, infrastructure development and sustained high deforestation rates.

According to PRODES data accessed via TerraBrasilis platform [25,27], Manaus is among the cities with low accumulated deforestation increments, totaling 68.84 km2 of new deforested areas from 2008 to 2024, ranking 238th in the region. In contrast, Porto Velho ranks third among municipalities with the highest accumulated deforestation increments in the region, with 5219 km2 of newly deforested areas over the same period. Notably, in 2021 alone, Porto Velho lost approximately 619.3 km2 of forest cover, equivalent to 3% of its total forest area, highlighting the intense deforestation pressure in this area. These contrasting deforestation dynamics underline the selection of these two cities as case studies, representing distinct deforestation stages and socio-environmental contexts within the Brazilian Amazon.

For this study, a selection of individuals with information about the history and rate of deforestation and forest degradation, as well as which policy instruments are used in combating them in each of the study areas, were questioned, and their responses were used.

2.2. Key Informants and Stakeholders

Between March and July 2024, a total of 27 representatives (11 in Manaus and 16 in Porto Velho) from various forest-related institutions were interviewed using a questionnaire. The participants included individuals from various levels of government, public organizations, private companies, indigenous groups, and academic institutions. These individuals are considered key informants because they typically possess specialized knowledge about disturbance processes, policies, and broader contextual factors. A comprehensive list detailing the characteristics of these respondents and their respective organizations is available in Table 1.

Table 1.

Institutional representatives and their respective organizations.

Each representative was also categorized into one of three spatial levels based on the primary focus or nature of their institution’s work. These spatial levels corresponded to various jurisdictions or administrative units that work across the different study areas: (i) national (e.g., research institutes/universities or national forestry/environmental departments), (ii) regional (e.g., regional government offices or NGOs), and (iii) local (e.g., municipal government offices or traditional leaders).

In addition to experts and representatives, villagers from traditional communities and indigenous groups also participated in this study. These individuals are those directly affected by or involved in the deforestation process. Villagers are primary stakeholders as their livelihoods and environments are directly impacted by this process. A Focus group approach was used for these groups to reach as many people in the areas as possible and to overcome resource and time constraints. NGOs in Manaus and Porto Velho, Sustainable Amazon Foundation (FAS) and Guapore Ecological Action (ECOPORE), respectively, assisted this study in contact and visit these villages. Villages and the number of villagers that partook in this study are stated in Table 2.

Table 2.

Number of residents per village contacted by this study.

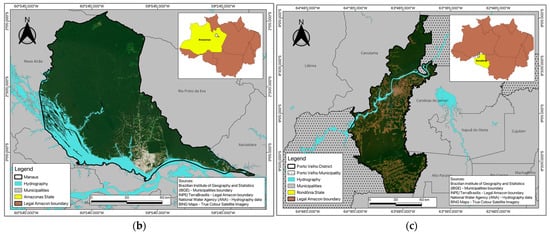

Focus groups comprised 3 to 10 people, organized to conduct discussions and questionnaires in each village. Three villages were visited in the Porto Velho area: “Nova Teotônio”, “Cujubim Grande/Cujubimzinho”, and “Cassupá/Salamãi Indigenous Reserve”. Meanwhile, four villages were visited in Manaus: “Terra Preta Indigenous Reserve”, “São Francisco do Igarapé do Chita”, “São Sebastião do Rio Cueiras”, and “Bela Vista do Jaraqui”. Locations of the villages can be observed in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Villages visited in this study located inside (a) Manaus and (b) Porto Velho. Basemap: Bing/ESRI.

In total, 76 individuals participated in the study, consisting of 49 villagers from seven communities and 27 experts spanning various institutional levels (Table 1 and Table 2). Due to logistical and partnership constraints, all surveyed villages were situated within officially designated protected areas previously supported by collaborating NGOs. As a result, the study does not include representation from unprotected localities that may experience different forest management pressures or conflict dynamics. The relatively small number of participants—especially within certain subgroups, such as local-level experts—reflects the feasibility and focus of the field campaign and may constrain the statistical power for some comparative analyses.

2.3. Questionnaires

The primary source of data for this study was questionnaires, which were conducted by employing semi-structured interviews, focus groups and self-filled forms. The methods for applying the questionnaires in the study sites were conducted in accordance with guidelines for good scientific practice and relevant regulations. Informed consent was secured from all participants, all of whom were over eighteen years old at the time of the interviews. All the questionnaires were completely anonymized. Interviews were conducted in Portuguese, which is the official language of the study areas.

The questionnaire conducted with representatives comprised four sections: (1) socioeconomic information of the study area, (2) one that inquired about the impact of various drivers on D&D over the study area, (3) a second that focused on the effects of policy measures aimed at halting D&D while increasing forest areas, and (4) additional information. In the first section, the respondents were questioned about the types of subsistence and economic activities carried out in the study areas. In the second section, respondents were asked for their perception of drivers by grading their influence in the area, as well as for the policy instruments for conservation in the third section. In the last section, the respondents were free to add any information that they deemed important for the context of this study. A list of local relevant drivers and policy instruments (variables) was provided for Section 2 and Section 3, but respondents were also allowed to contribute with additional responses. A copy of the questionnaire in English used in this study can be found in Table S1, and the official Portuguese version in Table S2.

The respondents were asked to evaluate each driver or policy instrument using a Likert scale. This scale ranged from 1 (representing “no influence”) to 5 (representing “very strong influence”). This method allowed participants to quantify their perceptions of the impact or effectiveness of various drivers and policy instruments in a standardized manner. While both expert stakeholders and villagers were surveyed on perceptions of deforestation drivers, policy instruments were only assessed through expert respondents. This approach reflects the specialized and technical nature of many policy measures, which require expert knowledge to evaluate effectively, whereas villagers contributed insights primarily on observable deforestation drivers impacting their livelihoods.

In the focus groups, a list of questions was first discussed with the villagers, and, when common ground was reached, answers were recorded. Topics discussed in the focus groups comprised: (i) subsistence and economic activities; (ii) historical context and changes observed over time; (iii) perceived drivers of deforestation in the area; (iv) relationship with forest conservation; (v) effectiveness of current policies and interventions; (vi) challenges and opportunities for sustainable forest management; and (vii) visions for the village’s future development. The list of questions discussed in the focus groups is available in English and Portuguese in Tables S3 and S4, respectively. Afterwards, the Likert-scale questionnaire for the list of drivers of deforestation was performed among the villagers to record their perceptions of what factors are mostly influencing forest loss in the region, according to their experiences and observations. The summary of the focus group discussion can be found in Table S5.

2.4. Variables

An initial contact and a pilot interview were conducted between November 2022 and August 2023 with some experts and key informants in both study sites to understand their general context and to ensure the capacity for comparison of various variables between the sites. In this initial contact, many of the variables and some of the questions used in the final questionnaire were determined. Variables were also defined based on existing scientific literature and from studies exploring forest loss in tropical forests and the Amazon, which were broad enough to be comparable across cities and spatial levels (Table 3 and Table 4).

Table 3.

Drivers of D&D variables included in the Likert-scale survey and their definition.

Table 4.

Policy instruments for conservation variables included in the Likert-scale survey and their definition.

While other studies focus on a single driver issue or a single policy instrument impact [17,18,20], this study uses various variables to identify the most influential regarding both deforestation and conservation. The variables used are diverse and cover a wide range of human activities, natural processes, and institutional conditions that affect forest cover, differing from other approaches. For drivers of D&D, the focus was on proximate/direct factors (that have a direct impact on forest loss, e.g., forest fires), but underlying or indirect factors (that influence these changes, e.g., failures of policy) were also included due to their importance in both areas. For policy instruments, the variables chosen included regulatory measures (e.g., spatial planning, land regulations), economic tools (e.g., land tenure, incentives), and other strategies (e.g., funds, projects). Finally, thirty variables were derived for this study: sixteen drivers of deforestation and degradation and fourteen policy instruments were used.

The sixteen variables belonging to drivers of D&D were as follows: (D1) Intensive Agriculture; (D2) Family Farming; (D3) Livestock Expansion; (D4) Illegal Logging; (D5) Forest Concession Licenses; (D6) Charcoal Production; (D7) Mining; (D8) Urbanization; (D9) Infrastructure; (D10) Forest Fires; (D11) Natural Disasters; (D12) Lack of Land Regularization; (D13) Political Intervention; (D14) Lack of Oversight/Funding for Oversight Bodies; (D15) Misinformation/Lack of Information; and (D16) Other factors. A list of the driver variables and their respective definitions can be viewed in Table 3.

Additionally, fourteen variables belonging to policy instruments for conservation were as follows: (P1) Reforestation; (P2) Restoration of Degraded Areas; (P3) Conservation Units; (P4) Indigenous Lands; (P5) Agroforestry (SAF); (P6) Forest Certification (FSC); (P7) REDD+ carbon projects; (P8) Financing of public supervisory bodies; (P9) Improving Land regularization; (P10) Community Forest Management; (P11) Environmental education; (P12) Financial incentives for small-scale agriculture; (P13) International Support (funds); and (P14) Other policies. A list of the policy instruments and their respective definitions can be viewed in Table 4.

2.5. Analytical Approaches

2.5.1. Relative Importance Index (RII)

This study employed the Relative Importance Index (RII), which is a non-parametric method [72], to identify the most important drivers and policies related to deforestation and degradation. The RII approach is particularly useful for analyzing and prioritizing factors in research involving Likert-scale responses or ordinal data. It involves collecting data using a Likert-scale questionnaire, typically ranging from 1 to 5, where respondents rate the importance or agreement level for different factors. Then the RII was calculated using the following formula:

where W is the weight given to each factor by respondents, A is the highest weight, and N is the total number of respondents. The RII value ranges from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating greater importance or agreement. In the context of this study, the RII was used to assess the relative importance of various drivers of deforestation and the perceived effectiveness of different conservation policies. By calculating the RII for each driver and policy across different spatial levels (national, regional, and local) and between different study areas (Manaus and Porto Velho), this study was able to identify which factors were considered most significant by the respondents and how these perceptions varied across different contexts.

2.5.2. Non-Parametric Statistical Tests

To analyze statistically significant differences between cities and spatial levels, this study utilized non-parametric tests, specifically the Mann–Whitney U test for comparing two groups (areas) and the Kruskal–Wallis one-way ANOVA, accompanied by Dunn test with Bonferroni correction, for comparing multiple groups (spatial levels). These tests were chosen due to their suitability for ordinal data and their robustness against non-normal distributions [73,74,75,76].

The Mann–Whitney U test examines whether two independent samples come from the same distribution, while the Kruskal–Wallis test extends this concept to three or more groups. These tests help identify statistically significant differences in the distribution of scores across different groups, providing insights into how perceptions of drivers and policies vary by location and scale. Dunn test with Bonferroni correction is a post hoc test used after a significant Kruskal–Wallis test to determine which specific groups differ from each other. It performs pairwise comparisons between groups while controlling for family-wise error rate. Limitations due to small subgroup sizes (spatial levels), especially among local experts, are acknowledged, and results for these groups are interpreted as exploratory.

2.5.3. Cronbach’s Alpha

To assess the internal consistency reliability of the Likert-scale items, this study calculated Cronbach’s alpha [77]. This measure evaluates how closely related a set of items is as a group, providing an indication of the scale’s reliability. Alpha values range from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating greater internal consistency. Generally, an alpha of 0.7 or higher is considered acceptable, though interpretation may vary depending on the specific context of the study. It is calculated as:

where k is the number of items, is the variance of item i, and is the total variance.

For this study, Cronbach’s Alpha resulted in a strong internal consistency for both villagers’ (α = 0.90) and experts’ (α = 0.83) perceptions of deforestation drivers. Additionally, the expert survey’s section on conservation policies also demonstrated acceptable reliability (α = 0.75), indicating that the measurement instruments were robust across different respondent groups and survey components.

2.5.4. Spearman’s Correlation Coefficient

This study utilized Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient [78] to assess the strength and direction of monotonic relationships (whether linear or not) between different drivers and policies. This non-parametric measure is appropriate for ordinal data, such as Likert-scale responses, and does not assume a linear relationship or normal distribution. It evaluates how well the relationship between two variables can be described using a monotonic function, making it suitable for analyzing associations between drivers and policies related to deforestation and conservation. The coefficient ranges from −1 to +1, with values closer to these extremes indicating stronger negative or positive correlations, respectively, helping identify potential interconnections between different factors influencing deforestation and policies related to conservation across study areas. Finally, data analysis for this study was performed using Microsoft Excel and R (version 4.4.1) statistical packages like rstatix [79] and factoextra [80], as well as other helper functions.

3. Results

3.1. General Socioeconomic Information

The study included 76 participants from Manaus and Porto Velho, consisting of villagers and experts. Among the villagers, 26 were female and 23 were male, while in the expert group, 11 were female and 16 were male. In Manaus, the sample included 18 female villagers, 10 male villagers, 3 female experts, and 8 male experts. In Porto Velho, there were 8 female villagers, 13 male villagers, 8 female experts, and 8 male experts.

Participants engaged in a diverse range of economic activities, reflecting both rural subsistence and broader economic engagement in urban and rural contexts. In Manaus, subsistence activities included family farming (livestock, cassava, vegetables, manioc, corn, banana, guaraná, cupuaçu, pineapple), fishing, and extractivism (açaí, Brazil nuts, palm oil, copaíba oil, babaçu oil, andiroba oil, spices, medicinal herbs), and hunting. Economic activities in both urban and rural areas of Manaus encompassed family farming, fishing, extractivism, traditional handicraft, commerce, industry, private and public services, and tourism. In Porto Velho, subsistence activities were similar, including family farming, fishing, and extractivism. The economic activities in Porto Velho included family farming, fishing, extractivism, agribusiness (soy crop and beef production), commerce, private and public services, tourism, mining, and timber. In both study areas, most villagers engaged in small-scale farming, fishing, or both, for subsistence or as an economic activity.

3.2. Perceptions of Main Drivers of Deforestation and Forest Degradation (D&D)

Villagers’ perceptions identified what is driving D&D in Manaus and Porto Velho. The result of the RII analysis (Table 5) shows that Natural Disasters (D11) emerged as the most important driver overall (RII = 0.79) in both study areas, consistent with community reports during focus group discussions (Table S5). Participants recalled the severe flooding in Porto Velho in 2014 and the widespread drought across the Amazon in 2023, emphasizing how these events have disrupted livelihoods, compromised agricultural productivity, and intensified forest vulnerabilities.

Table 5.

Relative Importance Index values of driver variables in relation to villagers’ perceptions, ranked by most important according to overall perception.

Forest Fires (D10) was one of the most important drivers according to villagers (RII = 0.63), ranking high in Porto Velho (RII = 0.81) in contrast to Manaus (RII = 0.50), a pattern also reflected in focus group discussions where recurrent fire incidents during intense dry seasons were emphasized (Table S5). This higher perceived influence in Porto Velho can be linked to the increased fire frequency, especially in southern Amazonas and Rondônia, to human activities such as slash-and-burn agriculture, land clearing for cattle ranching, and insufficient enforcement of fire prevention laws. The urgency conveyed by these narratives underscores the acute vulnerability of Porto Velho communities to fire hazards, underscoring the need for enhanced fire management and rapid response mechanisms.

Supporting these perceptions, non-parametric statistical tests (Table 6) revealed forest fires (D10) as the most statistically significant driver (p < 0.01) with a moderate effect size of r = 0.43, indicating a practical difference in perception between the study areas. Cattle Ranching Expansion (D03) also demonstrated high significance (p < 0.01, r = 0.38), similar to forest fires, with Porto Velho villagers rating it higher (RII = 0.51) than Manaus villagers (RII = 0.29). This higher perception in Porto Velho corresponds with the fact that cattle ranching is a major driver of deforestation in the Amazon, especially in areas where the agricultural frontier is advancing, such as the “Arc of Deforestation”, where this city is located [1].

Table 6.

Results of non-parametric ANOVAs for the sixteen driver variables, with overall significances across informant groups, areas and governance levels (****: <0.0001, ***: <0.001, **: <0.01, *: <0.05, ns not significant [>0.05]) and results for group comparison (Nat: National, Reg: Regional, Loc: Local).

Additionally, Political Intervention (D13) and Charcoal Production (D06) displayed a significant difference (p < 0.05, moderate effect size r = 0.34 and r = 0.37, respectively), with Porto Velho villagers perceiving them as more important (RII = 0.70 and RII = 0.66, respectively) compared to Manaus. Urbanization (D08) and Infrastructure (D09) also both exhibited significant differences (p < 0.05, both moderate effect size r = 0.33), with higher ratings placed by Porto Velho villagers (RII = 0.62 and RII = 0.51, respectively), which could reflect the impact of the Rio Madeira Dams and the various highways in Porto Velho.

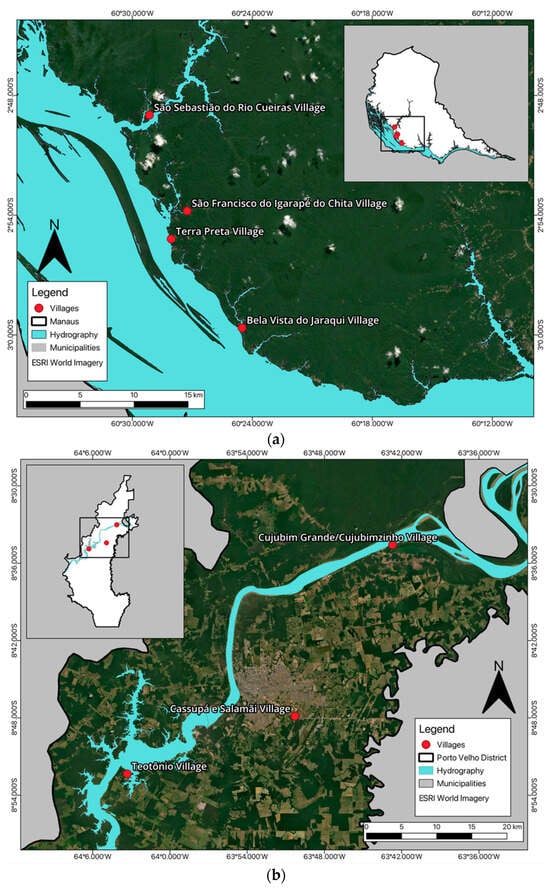

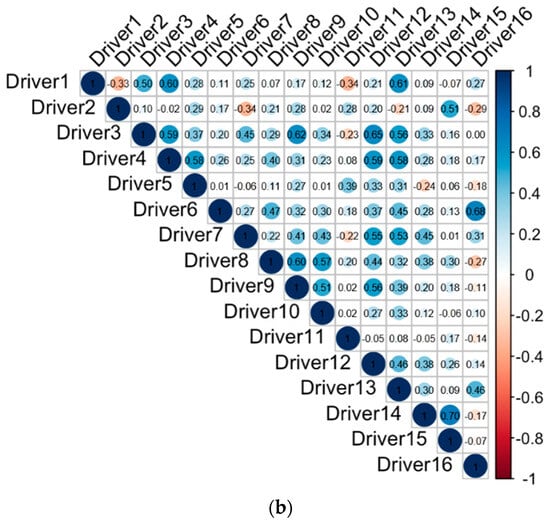

Spearman’s correlation of drivers among villagers (Figure 3a) showed several notable patterns between them. Cattle Ranching Expansion (D03) exhibited strong positive correlations with Mining (D07) and Lack of Land Regularization (D12), suggesting a perceived association between this activity, unclear land ownership and other intrusive economic activities. Other drivers related to economic activities and development, such as Charcoal Production (D06), Mining (D07), and Urbanization (D08), showed strong correlations with each other (ρ > 0.60), which could indicate that these activities are being perceived as interconnected in their impact on forest areas.

Figure 3.

Correlation matrix of perceived drivers based on Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients for (a) villagers’ group and (b) expert group. Coefficients range from −1 (perfect negative correlation) to 1 (perfect positive correlation).

Governance-related drivers, such as Lack of Land Regularization (D12) and Political Intervention (D13), are correlated strongly (ρ > 0.70) with various land use and extractive activity drivers, such as Cattle Ranching Expansion (D03) and Mining (D07). This could suggest a connection between governance issues and the occurrence of deforestation-related activities (Figure 3a). Additionally, Forest Fires (D10) correlate moderately to strongly with many other drivers, which could indicate that villagers see forest fires as connected to various human activities contributing to forest loss and degradation.

Regarding the experts’ perceptions, the most important drivers overall (Table 7), Forest Fires (D10) have the highest importance (RII = 0.81), indicating that experts consider this a critical driver in both regions, which also aligns with villagers’ perceptions overall (RII = 0.63). Cattle ranching expansion (D03), illegal logging (D04), and lack of land regularization (D12) share the second-highest overall importance (RII = 0.79), with Cattle Ranching Expansion rating higher in Porto Velho (RII = 0.89), suggesting this is a major contributor to forest disturbance in this specific area. Experts perceive this driver as more critical compared to villagers overall (RII = 0.38), which was also found to be highly significant between the two groups in Table 6 (p < 0.0001, large effect size r = 0.52). Lack of oversight/funding for oversight bodies (D14) and political intervention (D13) follow closely with RII values of 0.77 and 0.76, respectively, highlighting the importance of governance issues in deforestation. This result aligns closely with villager perceptions of political intervention (D13) (RII = 0.57), with both groups rating it higher in Porto Velho.

Table 7.

Relative Importance Index values of driver variables in relation to expert perceptions.

When observing the statistical differences between Manaus and Porto Velho (Table 6), Intensive Agriculture (D01) showed a significant difference (p < 0.01) with a large effect size (r = 0.53), indicating a substantial practical difference in perception between the study areas. Porto Velho observed the highest importance among them (RII = 0.75), indicating that agricultural expansion is more perceived in this area. Political Intervention (D13) also showed a significant difference (p < 0.05, r = 0.38) between Manaus (RII = 0.62) and Porto Velho (RII = 0.86), suggesting that experts in Porto Velho perceive a stronger influence of political factors on deforestation. Another important observation is that Cattle Ranching Expansion (D03) has a notably higher importance in Porto Velho (RII = 0.89) compared to Manaus (RII = 0.65); although not statistically significant between areas, this could suggest that agricultural activities are less significant in Manaus than other drivers.

Regarding statistical differences across spatial levels (Table 6), Intensive Agriculture (D01) shows a significant difference (p < 0.05, r = 0.17) between Regional and Local levels, where regional experts perceive it as a more important (RII = 0.64) driver of D&D than local experts (RII = 0.46). For Family Farming (D02), there is a significant difference (p < 0.05, r = 0.18) between National and Regional levels, and both levels perceive this driver as much more important (RII = 0.91 and RII = 0.80, respectively) than the Local level (RII = 0.57).

Natural Disasters (D11) show a significant difference (p < 0.05) between Regional (RII = 0.82) and Local (RII = 0.74) levels, with the National level (RII = 0.85) perceiving it as more important. Some interesting patterns observed in spatial-level analysis include Forest Fires (D10), where, although not statistically significant, a large difference was observed between Regional (RII = 0.80) and Local (RII = 0.46) levels, which could indicate different potential prioritization of certain drivers to be addressed in the areas. In addition, Political Intervention (D13) showed a consistently low perception across levels, with the regional level (RII = 0.33) seeing it as least important.

Spearman’s correlation of drivers among experts (Figure 3b) showed several significant patterns. A strong correlation (ρ = 0.65) is observed between Cattle Ranching Expansion (D03) and Lack of Land Regularization (D12), mirroring the pattern seen in the villagers’ driver correlation. This suggests that both experts and villagers perceive a connection between unclear land ownership and the expansion of cattle ranching. Family Farming (D02) stands out by showing weak or negative correlations with many other drivers, which could indicate that experts view family farming as relatively independent from other deforestation drivers.

Drivers related to agriculture and illegal activities, such as Intensive Agriculture (D01), Cattle Ranching Expansion (D03), and Illegal Logging (D04), demonstrate moderate to strong correlations with each other, which could indicate that experts perceive these activities as interconnected in their contribution to deforestation. Governance-related drivers, such as Lack of Land Regularization (D12) and Political Intervention (D13), correlate with various land use drivers (such as Intensive Agriculture (D01), Cattle Ranching Expansion (D03), and Illegal Logging (D04)), mirroring villagers’ perceptions, but also with infrastructure drivers (Urbanization (D08) and Infrastructure (D09)), suggesting a relationship between governance issues and the occurrence of deforestation-related activities across different sectors.

3.3. Perceptions on Policy Instruments for Forest Conservation

The results reveal the perceived effectiveness of various policies to combat deforestation in Manaus and Porto Velho from experts’ perspectives. Experts perceived Conservation Units (P03) as the most effective policy overall (RII = 0.95), with a significant difference between areas (p < 0.05) and a moderate effect size (r = 0.39), indicating a meaningful practical difference in perception of their effectiveness across regions. This is further supported by the higher importance assigned in Manaus (RII = 1.00) compared to Porto Velho (RII = 0.91) (Table 8 and Table 9). Additionally, Indigenous Lands (P04) and International Support (funds) (P13) were both highly rated (RII = 0.87 and 0.88, respectively), with no significant differences between the two areas. This highlights the importance of different types of protected areas, as well as the support of the international community in curbing D&D in this region, with their effectiveness being particularly clear to experts in Manaus.

Table 8.

Relative Importance Index values of variables in relation to expert perceptions.

Table 9.

Results of non-parametric ANOVAs for the fourteen variables, with overall significances across areas and governance levels (*: <0.05, ns not significant [>0.05]) and results for group comparison (Nat: National, Reg: Regional, Loc: Local).

Additionally, Restoration of Degraded Areas (P02) and Land Regularization (P09) were also highly rated (RII = 0.84), indicating that experts in both areas recognize the importance of rehabilitating damaged forests and clarifying land ownership to combat deforestation. Environmental Education (P11) was consistently perceived as important in both areas (RII = 0.80), reflecting the need for increased public awareness about the value of the rainforest. Financing of public supervisory bodies (P08) was also rated highly (RII = 0.81), as environmental agencies like IBAMA are essential to monitor for environmental violations such as illegal fires and impose sanctions and other enforcement measures to hold violators accountable. Another important observation is that Reforestation (D01) has a notably higher importance in Manaus (RII = 0.73) compared to Porto Velho (RII = 0.51), which could entail that the implementation of this measure is given greater priority in Manaus than in Porto Velho.

Regarding the governance-level analysis of expert responses (Table 8), it provided insights into how different governance levels perceive the effectiveness of various policies to combat deforestation. Conservation Units (CUs) received the highest overall ratings across all levels (National: 0.96, Regional: 1.00, Local: 0.86). This suggests strong agreement on the importance of protected areas, with regional experts placing the highest value on this policy. Restoration of Degraded Areas (P02) is rated highest by the Regional level (RII = 0.96), compared to National (RII = 0.76) and Local (RII = 0.69) levels. Although not statistically significant, this suggests regional experts place more emphasis on restoration efforts.

Indigenous Lands (P04) received consistently high ratings across levels (National: 0.91, Regional: 0.89, Local: 0.77), and the absence of significant differences indicates broad agreement on the importance of protected areas in forest conservation. Land regularization (P09) also received consistently high ratings (National: 0.82, Regional: 0.82, Local: 0.89), with slightly higher importance at the Local level, possibly reflecting the on-the-ground importance of clear land ownership. International Support (funds) (P13) showed high and consistent ratings across levels (National: 0.89, Regional: 0.87, Local: 0.89), indicating an agreement on the importance of international funding for conservation efforts.

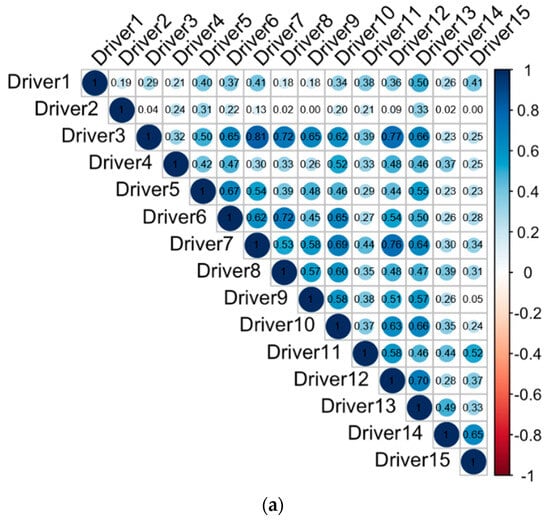

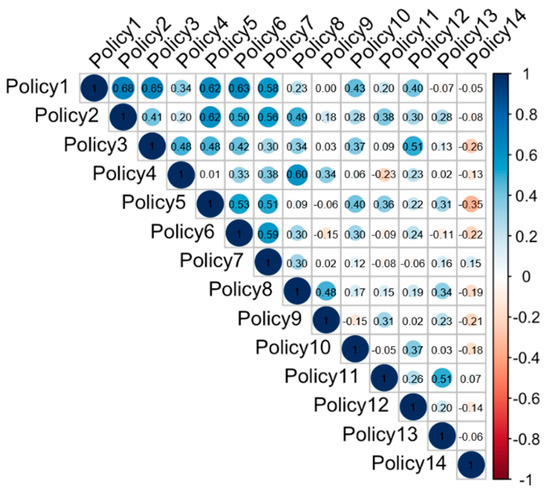

Spearman’s correlation analysis of policy preferences among experts (Figure 4) revealed key patterns. A strong positive correlation (ρ = 0.68) was observed between Reforestation (P01) and Conservation Units (P03), aligning with their high scores in prior analyses. This suggests experts perceive reforestation and protected areas as complementary strategies for forest conservation. Additionally, policies focused on land conservation and restoration (P01, P02, P03, P04) exhibited moderate to strong intercorrelations, indicating that experts likely view these instruments as interconnected components of a cohesive conservation framework.

Figure 4.

Correlation matrix of perceived policy instruments (P01–P14) based on Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients for the expert group. Coefficients range from −1 (perfect negative correlation) to 1 (perfect positive correlation).

Sustainable practice tools and policies (Agroforestry (P05), Forest Certification (P06), REDD+ carbon projects (P07)) correlate moderately with each other and with land restoration policies (Reforestation (P01) and Restoration of Degraded Areas (P02)), showing a relationship between sustainable practices and efforts to restore and conserve forested areas. Interestingly, Environmental Education (P11) shows weak correlations with most policies, except for International Support (P13), which could indicate that this instrument is a somewhat distinct approach to forest conservation, potentially complementing other policies rather than being directly linked to them.

4. Discussion

4.1. Local Perceptions on D&D Drivers

The comparative analysis of Manaus and Porto Velho revealed significant regional differences in the drivers of deforestation and forest degradation. Respondents identified forest fires as the most critical driver in both regions, underscoring the persistent challenge of fire-related forest loss across the Amazon [81]. Villagers in both areas also emphasized the impact of natural disasters, indicating that local communities are particularly vulnerable to extreme weather events, which have become increasingly frequent in recent years [21].

Informants reported that flooding accelerates erosion and leads to the loss of riverbanks, often causing forested or agricultural land to collapse into rivers. In contrast, droughts significantly heighten the risk of fires, threatening local landscapes. These findings are supported by focus group discussions, which recalled the devastating 2014 flooding in Porto Velho and the severe drought across the Amazon in 2023 (Table S5). Such events have profound impacts on community livelihoods and forest conditions, underscoring the urgent need for more effective fire response strategies, especially near the Arc of Deforestation. Implementing alternatives to slash-and-burn agriculture, strengthening enforcement against land grabbing, and improving preparedness for extreme droughts are essential measures to protect communities in these vulnerable Amazonian regions.

Furthermore, recent studies documented the severe drought that affected the Amazon Basin in 2023, characterized by record-low river water levels and unprecedented warm conditions [82,83,84]. Climate modeling indicates that climate change has substantially increased the likelihood of such extreme drought events, with warming contributing to reduced precipitation and intensifying dry season severity in the region. These changes are projected to persist and potentially exacerbate fire risk, forest degradation, and ecosystem vulnerability in the region [83,85]. Recognizing these dynamics is critical for contextualizing our findings on fire and natural disaster drivers linked to deforestation and degradation.

Similar to the experiences reported in Manaus and Porto Velho, a study by Bauer et al. [22] found that indigenous communities in the Bolivian Amazon highlight the role of extreme weather events, such as droughts and floods, not only in driving environmental changes but also in affecting forest-based livelihoods and food security. The same was observed in a study by Almudi & Sinclair [21], who emphasize how rural communities in the Brazilian Amazon perceive and respond to extreme hydroclimatic events like floods and droughts. Their study, conducted in 19 communities in the Amazonas state, highlights that frequent floods and severe droughts are recognized locally as major threats to community livelihoods, including forest-based products. By comparing these perspectives, it becomes clear that all the study areas share vulnerabilities to natural hazards and fire; however, indigenous communities’ knowledge helps understand how such drivers impact daily life and livelihoods in different parts of the Amazon.

The statistically significant difference and large effect size in the Intensive Agriculture variable between responses in Porto Velho and Manaus likely reflect the distinct agricultural landscapes and expansion patterns in these regions, with Porto Velho perceiving it as more important. In Porto Velho, soy production has increasingly grown in recent years. According to the Municipal Agricultural Survey (PAM), released by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) in 2023, Porto Velho observed the highest soya production in Rondônia, overtaking the municipalities in the south of the state, which are traditionally the state’s biggest producers. In 2023, 181,000 tonnes of soy were produced in Porto Velho, representing an increase of 62.3% in relation to production in 2022 (around 112,000 tonnes) [86].

Cattle Ranching Expansion and Political Intervention were also perceived more substantially in Porto Velho, suggesting different governance dynamics and political–economic contexts that influence forest conservation among the areas of study. In recent years, Porto Velho has emerged as an agribusiness hub, prioritizing policies that favor the emerging agricultural sector and weaken environmental conservation and sustainability-based policies in the area [87]. Furthermore, the high rate of D&D observed in Porto Velho in recent years could have resulted from these factors [88].

Concerning the governance-level analysis across national, regional, and local levels, it has further added nuance to our understanding of D&D drivers. Various drivers were perceived dramatically differently across governance levels. National-level experts, for instance, attributed much higher importance to family farming compared to local-level informants, who ranked Cattle Ranching Expansion as the most important driver. This discrepancy within governance levels highlights potential misalignments between policy perspectives and local realities [11].

Additionally, local-level experts attributed higher importance to very few drivers when compared to the national and regional levels (see Table 7). This may be because stakeholders at national and regional levels are typically more involved in policy planning overall; therefore, they tend to have a broader view on a wider range of threats and potential interventions in the region. As a result, they are likely to identify more drivers and policies as relevant. In contrast, local stakeholders focus on a narrower set of key drivers that they encounter directly and are more familiar with, as well as the limitations of policies as implemented on the ground. These gaps are understandable, as information and policy rules regarding forest management can often take time to reach local-level government in these areas.

Such observations regarding governance levels parallel findings by Velasco et al. [50] in their cross-scale analysis of stakeholder perceptions about future threats to tropical forests and preferred policy instruments, conducted in three different tropical countries (Zambia, Ecuador and the Philippines). Their study shows that local-level public institutions in these countries perceived lower alertness concerning the influence of drivers on deforestation when compared with international and national levels. This shows that similar challenges are faced by different levels of governance in various tropical countries.

Finally, correlation analyses revealed complex interconnections between drivers. However, local village perceptions and expert perspectives aligned in emphasizing connections between agricultural expansion and political decision-making, particularly through the strong correlation between cattle ranching expansion and lack of land regularization. This finding underscores the socio-political dimensions of D&D in these areas where well-reported land regularization issues, such as the widespread practice of Grileiros (illegal land grabbing through fraudulent documentation), directly enable destructive land use patterns [89]. These practices create overlapping claims and legal ambiguities, weakening enforcement of environmental protections while incentivizing rapid deforestation for short-term economic gains.

4.2. Influences of Forest Conservation Policies

Conservation policies in the study areas demonstrated varied influence across different spatial and institutional contexts. Conservation Units emerged as the most impactful policy instrument, receiving exceptionally high ratings based on expert perception across study areas and governance levels. This finding reinforces existing research highlighting the critical role of these protected areas in maintaining forest integrity throughout the study areas [88] and the Brazilian Amazon [9].

In contrast, Velasco et al. [50], in their study about the perceptions of preferred future policy instruments to combat deforestation in tropical countries, found that, overall, representatives from forest-related institutions showed a strong favoritism for reforestation and forest restoration, rather than protected areas (which included forest reserves, indigenous reserves and other programs) for future forest protection measures. This could represent a shift from protection to focus on more integrative approaches or could also reflect negative experiences regarding regulatory policies in these areas [90]. Their study, however, focuses on a larger scale, while my study refers to a more local context and specific policies and drivers.

Another strategy consistently recognized as crucial was the variable International Support, reflecting growing acknowledgment of the importance of other forms of institutional funding to support conservation efforts. Although not a policy instrument itself, the observed high ratings for this support mechanism suggest that the international recognition and support of environmental issues in the Amazon represent a powerful approach to forest conservation. One example is the Amazon Fund, which supports efforts to prevent deforestation, restore forests, and promote sustainable development and social inclusion in the region. The fund operates under the UN’s REDD+ framework and is central to large-scale initiatives. Additionally, land regularization policies similarly received strong support, indicating the importance of clear land tenure in mitigating deforestation and forest degradation, as was also clearly stated in the perceptions of drivers of deforestation.

Informants in both study areas indicated that Forest Certification (FSC)was the least impactful conservation instrument. This perception is likely due to structural barriers such as certification costs and complexity, which would disproportionately affect smaller operations, as the certification often favors large producers with concentrated supply chains, while local communities in the study areas would struggle to meet requirements without technical and financial support [91]. These challenges, combined with limited market incentives for certified timber in domestic supply chains, reduce the perceived influence of this instrument in addressing regional deforestation pressures.

Regarding correlation analyses of policies, it revealed interesting synergies and potential complementarities between instruments. The correlation analysis revealed strong positive connections between reforestation efforts, conservation units, and indigenous land management, suggesting these approaches might be most effective when implemented collaboratively rather than in isolation. The inclusion of REDD+ initiatives could further reinforce this complementary approach: REDD+ projects not only aim to reduce emissions from deforestation and forest degradation but also promote reforestation, sustainable forest management, and the enhancement of forest carbon stocks. By integrating REDD+ mechanisms with other conservation and restoration strategies, it is possible to maximize climate mitigation and socioeconomic gains for people living both inside and outside these protected areas.

While correlation analysis revealed significant associations among some policy measures, weak correlations involving environmental education were observed. This could highlight the complex and indirect role that this instrument has in influencing deforestation dynamics, where its effects are measured through long-term behavioral changes rather than immediate impacts. Additionally, an imbalance in education quality and community engagement could contribute to different perceptions and limit strong correlations in our dataset. Therefore, our findings suggest that environmental education serves as a fundamental element within broader conservation strategies, but it should be complemented by additional measures to ensure effectiveness.

4.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

While providing valuable insights, this study acknowledges several methodological limitations. The focus on two development centers, while informative, cannot fully capture Amazon’s vast ecological and social diversity. In this sense, the findings of this study may not fully generalize to other Amazonian contexts, particularly more remote or heterogeneous areas such as remote indigenous territories, frontier agricultural zones, or smaller rural communities with unique governance structures. To improve generalizability, future research should include a broader spatial sample encompassing diverse Amazon subregions and stakeholder groups to capture regional heterogeneity. Longitudinal mixed-method studies incorporating both satellite-based deforestation monitoring and participatory qualitative data over time would also strengthen understanding of temporal and causal relationships behind deforestation and policy outcomes. In addition to that, incorporating climatic perspectives within this context could also support adaptation measures against climate change regional issues, as local communities experience these changes firsthand and are the most affected by them [21].

Another key limitation was that, in this study, the total sample size is relatively small, especially within the expert subgroups at each governance level. This limited statistical power may have reduced the ability to detect significant differences in perceptions across spatial or institutional contexts and increased the risk of type II errors. Furthermore, all villages surveyed were located within protected areas accessible through NGO partners, potentially introducing selection bias. Communities in unprotected or more conflict-prone zones (where drivers, policy effectiveness, and attitudes may differ) are underrepresented. Consequently, findings should be interpreted as most relevant to contexts where conservation policies are established and may not fully capture the diversity of perspectives across the wider Amazon. Future research should aim to include a broader and more balanced sampling framework, including both protected and unprotected areas, to improve generalizability and insight into the spectrum of governance challenges across the region. In addition to a continuous observation of perception changes and policy influences over time, engaging with policymakers at other administrative scales (such as the international level) could enhance the knowledge needed to design effective conservation strategies across the biome. Comparative research with other Amazonian countries could also offer broader insights into different national-level conservation approaches. The complex nature of deforestation demands continuous, adaptive research strategies that can capture evolving environmental and social dynamics. By maintaining an integrative research approach, effective strategies for sustainable Amazonian forest management can be developed.

5. Conclusions

This study aimed to examine what is driving deforestation and forest degradation and the importance of conservation policies in the Brazilian Amazon by integrating local perspectives and perceptions from different areas and levels of governance in the region. This study revealed significant variations in the perception of deforestation drivers and policy effectiveness, underscoring the complex nature of forest conservation challenges in the Amazon.

Key findings from this study reveal the following: (1) Villagers in both study areas emphasized the significant impact of natural disasters, ranking them among their highest concerns and demonstrating strong local awareness of extreme weather events. In Porto Velho, forest fires were also identified as a major issue, with a notable difference compared to Manaus, and cattle ranching expansion was similarly ranked highly. (2) From the perspective of experts, the main drivers identified in Manaus included forest fires, lack of land regularization, and insufficient oversight or funding for regulatory bodies. In Porto Velho, cattle ranching expansion and political intervention were among the top-ranked drivers, while intensive agriculture showed a statistically significant difference between the two areas (p < 0.01). (3) Through correlation analysis, both local and expert perspectives revealed strong links between agricultural expansion and unresolved land tenure issues, particularly through the strong correlation between cattle ranching and the lack of land regularization. (4) Conservation Units, Indigenous Lands, Restoration of Degraded Areas and Land Regularization emerged as the most impactful policies, emphasizing the importance of protected areas coupled with land restoration and regularization for forest conservation efforts across study areas.

These findings have significant implications for policy and practice in the Amazon, advocating for regionally adapted conservation approaches, enhanced multi-level governance structures, and integrated strategies that address the connected nature of deforestation drivers. This study emphasizes that unresolved land tenure remains a critical issue driving D&D, strongly linked to activities such as cattle ranching and illegal logging. Accelerating land regularization could reduce land grabbing and speculative deforestation, especially along the Arc of Deforestation. Addressing this issue alongside enhancing fire prevention, promoting alternatives to slash-and-burn, and preparing communities for drought events is vital for sustainable forest stewardship.

Our results also emphasize the importance of strengthening multi-level governance mechanisms, as divergent perceptions between national, regional, and local stakeholders reveal potential misalignments in policy implementation and understanding. Improved communication pathways across governance levels could enhance the efforts to sustainably manage the vast areas of forest under their respective governance.

The strong performance of policies supporting Conservation Units and Indigenous Lands, as seen in the perception results, reinforces the importance of protected areas in curbing deforestation in the region. Effective enforcement and governance mechanisms are critical to ensuring that these protected areas fulfill their conservation objectives. Initiatives such as the Amazon Region Protected Areas Program (ARPA) have been instrumental in supporting and expanding protected areas across the region. Strengthening resources for monitoring, law enforcement, and community participation through such programs is essential to enhancing the resilience of conservation units against emerging threats.

In conclusion, this research contributes to a more nuanced understanding of deforestation dynamics in the Brazilian Amazon and emphasizes the importance of incorporating diverse perspectives in conservation efforts. By adopting integrative approaches that respect local contexts and traditional knowledge, we can develop more effective strategies for the sustainable management of this crucial ecosystem and balance conservation needs with the well-being of local communities.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su172210094/s1, Table S1: Questionnaire used in key informants’ interviews (representatives and villagers); Table S2: Questionnaire used in key informants’ interviews (representatives and villagers), in Portuguese; Table S3: Questions used in the focus group discussion; Table S4: Questions used in the focus group discussion, in Portuguese; Table S5: Summary of focus group discussions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology, D.N.L., T.H. and S.T.; formal analysis, investigation, data curation, and writing—original draft preparation, D.N.L.; writing—review and editing, supervision, and project administration, T.H. and S.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of The University of Tokyo (protocol code H-250313001 and date of approval 9 April 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the first author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Fundação Amazônia Sustentável (FAS) in Manaus and the Ação Ecológica Guaporé (ECOPORÉ) in Porto Velho for providing this study with the technical and logistical support to reach the villages visited in the study areas. The authors would also like to express their gratitude to the reviewers for their comments and suggestions to improve the quality of this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Fearnside, P.M. Deforestation of the Brazilian Amazon. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Environmental Science; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Barona, E.; Ramankutty, N.; Hyman, G.; Coomes, O.T. The Role of Pasture and Soybean in Deforestation of the Brazilian Amazon. Environ. Res. Lett. 2010, 5, 024002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauer, S. Soy Expansion into the Agricultural Frontiers of the Brazilian Amazon: The Agribusiness Economy and Its Social and Environmental Conflicts. Land Use Policy 2018, 79, 326–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertão, A.; De, C.; Freitas, O. Amazônia: Dinâmicas Agrárias e Territoriais Contemporâneas; Pedro & João Editores: Porto, Portugal, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- dos Santos, C.A.C.; Lima, J.R.A. Análise Dos Efeitos Da Expansão Urbana de Manaus-AM Sobre Parâmetros Ambientais Através de Imagens de Satélite (Analysis of the Urban Expansion Effects of Manaus-AM on Environmental Parameters through Satellite Images). Rev. Bras. Geogr. Física 2013, 6, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fearnside, P.M.; de Alencastro Graça, P.M.L. BR-319: Brazil’s Manaus-Porto Velho Highway and the Potential Impact of Linking the Arc of Deforestation to Central Amazonia. Environ. Manag. 2006, 38, 705–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FUNBIO Programa Áreas Protegidas Da Amazônia–ARPA. Available online: https://www.funbio.org.br/programas_e_projetos/programa-arpa-funbio/ (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Pfaff, A.; Robalino, J.; Herrera, D.; Sandoval, C. Protected Areas’ Impacts on Brazilian Amazon Deforestation: Examining Conservation–Development Interactions to Inform Planning. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0129460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares-Filho, B.S.; Ferreira, M.N.; Marques, F.F.C.; de Oliveira, A.R.; Silva, F.R.; Börner, J. Contribution of the Amazon Protected Areas Program to Forest Conservation. Biol. Conserv. 2023, 279, 109928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.J.B.; Sevalho, E.S.; Miranda, I.P.A. Potencial Das Palmeiras Nativas Da Amazônia Brasileira Para a Bioeconomia: Análise Em Rede Da Produção Científica e Tecnológica. Ciência Florest. 2021, 31, 1020–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hecht, S.; Schmink, M.; Abers, R.; Assad, E.; Humphreys Bebbington, D.; Eduaro, B.; Costa, F.; Durán Calisto, A.M.; Fearnside, P.M.; Garrett, R.; et al. The Amazon in Motion: Changing Politics, Development Strategies, Peoples, Landscapes, and Livelihoods; SciELO Brasil: São Paulo, Brazil, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Joshi, A.; Kale, S.; Chandel, S.; Pal, D. Likert Scale: Explored and Explained. Br. J. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2015, 7, 396–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feliciano, D.; Bouriaud, L.; Brahic, E.; Deuffic, P.; Dobsinska, Z.; Jarsky, V.; Lawrence, A.; Nybakk, E.; Quiroga, S.; Suarez, C.; et al. Understanding Private Forest Owners’ Conceptualisation of Forest Management: Evidence from a Survey in Seven European Countries. J. Rural. Stud. 2017, 54, 162–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, S.; Panda, R.K. Scale Transformation of Analytical Hierarchy Process to Likert Weighted Measurement Method: An Analysis on Environmental Consciousness and Brand Equity. Int. J. Soc. Syst. Sci. 2017, 9, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wusqo, I.U.; Setiawati, F.A.; Istiyono, E.; Mukhson, A. Exploratory Factor Analysis of Environmental Awareness Assessment Based on Local Wisdom by Using Summated Rating and Likert Scale. J. Penelit. Dan. Pembelajaran IPA 2022, 8, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Córdoba, D.; Juen, L.; Selfa, T.; Peredo, A.M.; Montag, L.F.d.A.; Sombra, D.; Santos, M.P.D. Understanding Local Perceptions of the Impacts of Large-Scale Oil Palm Plantations on Ecosystem Services in the Brazilian Amazon. Policy Econ. 2019, 109, 102007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, M.; Skutsch, M.; Costa, G.M. Deforestation and the Social Impacts of Soy for Biodiesel: Perspectives of Farmers in the South Brazilian Amazon. Ecol. Soc. 2011, 16, art4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assis, D.M.S.d.; Tavares-Martins, A.C.C.; Beltrão, N.E.S.; Sarmento, P.S.d.M. Environmental Perception in Traditional Communities: A Study in Soure Marine Extractive Reserve, Pará, Brazil. Ambiente Soc. 2020, 23, e01481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, H.F.A.; Souza, A.F.d.; Cardoso da Silva, J.M. Public Support for Protected Areas in New Forest Frontiers in the Brazilian Amazon. Environ. Conserv. 2019, 46, 278–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tristão, V.T.V.; Tristão, J.A.M. The Contribution of NGOs in Environmental Education: An Evaluation of Stakeholders’ Perception. Ambiente Soc. 2016, 19, 47–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almudi, T.; Sinclair, A.J. Extreme Hydroclimatic Events in Rural Communities of the Brazilian Amazon: Local Perceptions of Change, Impacts, and Adaptation. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2022, 22, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, T.N.; de Jong, W.; Ingram, V. Perception Matters: An Indigenous Perspective on Climate Change and Its Effects on Forest-Based Livelihoods in the Amazon. Ecol. Soc. 2022, 27, art17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, M.d.P.S.R.; Barroso, S.C.; Lira, T. de M. Populações Tradicionais: Manejo Dos Recursos Naturais Na Amazônia. Praia Vermelha 2010, 19. [Google Scholar]

- Fraxe, T.; Silva, S.; Miguez, S.; Witkoski, A.; Castro, A. Os Povos Amazônicos: Identidades e Práticas Culturais. In Pesquisa Interdisciplinar em Ciências do Meio Ambiente; EDUA: Manaus, Brazil, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- INPE Metodologia utilizada nos projetos PRODES e DETER–2a Edição. Available online: http://mtc-m21d.sid.inpe.br/col/sid.inpe.br/mtc-m21d/2022/08.25.11.46/doc/thisInformationItemHomePage.html (accessed on 29 August 2024).

- IBGE Cidades. Available online: https://cidades.ibge.gov.br/ (accessed on 27 September 2024).

- Assis, L.F.; Ferreira, K.R.; Vinhas, L.; Maurano, L.; Almeida, C.; Carvalho, A.; Rodrigues, J.; Maciel, A.; Camargo, C. TerraBrasilis: A Spatial Data Analytics Infrastructure for Large-Scale Thematic Mapping. ISPRS Int. J. Geoinf. 2019, 8, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayathilake, H.M.; Prescott, G.W.; Carrasco, L.R.; Rao, M.; Symes, W.S. Drivers of Deforestation and Degradation for 28 Tropical Conservation Landscapes. Ambio 2021, 50, 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, P.G.; Slay, C.M.; Harris, N.L.; Tyukavina, A.; Hansen, M.C. Classifying Drivers of Global Forest Loss. Science (1979) 2018, 361, 1108–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fritz, S.; Laso Bayas, J.C.; See, L.; Schepaschenko, D.; Hofhansl, F.; Jung, M.; Dürauer, M.; Georgieva, I.; Danylo, O.; Lesiv, M.; et al. A Continental Assessment of the Drivers of Tropical Deforestation with a Focus on Protected Areas. Front. Conserv. Sci. 2022, 3, 830248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verburg, R.; Filho, S.R.; Lindoso, D.; Debortoli, N.; Litre, G.; Bursztyn, M. The Impact of Commodity Price and Conservation Policy Scenarios on Deforestation and Agricultural Land Use in a Frontier Area within the Amazon. Land Use Policy 2014, 37, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, C.; García Márquez, J.R.; Krueger, T. A Local Perspective on Drivers and Measures to Slow Deforestation in the Andean-Amazonian Foothills of Colombia. Land Use Policy 2018, 77, 379–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vale, P.; Gibbs, H.; Vale, R.; Christie, M.; Florence, E.; Munger, J.; Sabaini, D. The Expansion of Intensive Beef Farming to the Brazilian Amazon. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2019, 57, 101922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asner, G.P.; Knapp, D.E.; Broadbent, E.N.; Oliveira, P.J.C.; Keller, M.; Silva, J.N. Selective Logging in the Brazilian Amazon. Science 2005, 310, 480–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matricardi, E.A.T.; Skole, D.L.; Pedlowski, M.A.; Chomentowski, W. Assessment of Forest Disturbances by Selective Logging and Forest Fires in the Brazilian Amazon Using Landsat Data. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2013, 34, 1057–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condé, T.M.; Higuchi, N.; Lima, A.J.N. Illegal Selective Logging and Forest Fires in the Northern Brazilian Amazon. Forests 2019, 10, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, T.A.; Beuchle, R.; Griess, V.C.; Verhegghen, A.; Vogt, P. Spatial Patterns of Logging-Related Disturbance Events: A Multi-Scale Analysis on Forest Management Units Located in the Brazilian Amazon. Landsc. Ecol. 2020, 35, 2083–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fearnside, P.M. Deforestation Control in Mato Grosso: A New Model for Slowing the Loss of Brazil’s Amazon Forest. AMBIO A J. Hum. Environ. 2003, 32, 343–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferretti-Gallon, K.; Busch, J. What Drives Deforestation and What Stops It? A Meta-Analysis of Spatially Explicit Econometric Studies; Center for Global Development: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sonter, L.J.; Barrett, D.J.; Moran, C.J.; Soares-Filho, B.S. Carbon Emissions Due to Deforestation for the Production of Charcoal Used in Brazil’s Steel Industry. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2015, 5, 359–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piketty, M.-G.; Wichert, M.; Fallot, A.; Aimola, L. Assessing Land Availability to Produce Biomass for Energy: The Case of Brazilian Charcoal for Steel Making. Biomass Bioenergy 2009, 33, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonter, L.J.; Herrera, D.; Barrett, D.J.; Galford, G.L.; Moran, C.J.; Soares-Filho, B.S. Mining Drives Extensive Deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza-Filho, P.; Nascimento, W.; Santos, D.; Weber, E.; Silva, R.; Siqueira, J. A GEOBIA Approach for Multitemporal Land-Cover and Land-Use Change Analysis in a Tropical Watershed in the Southeastern Amazon. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, P.; VanWey, L. Where Deforestation Leads to Urbanization: How Resource Extraction Is Leading to Urban Growth in the Brazilian Amazon. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 2015, 105, 806–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, Y.L.F.; Yanai, A.M.; Ramos, C.J.P.; Graça, P.M.L.A.; Veiga, J.A.P.; Correia, F.W.S.; Fearnside, P.M. Amazon Deforestation and Urban Expansion: Simulating Future Growth in the Manaus Metropolitan Region, Brazil. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 304, 114279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrade, M.B.; Ferrante, L.; Fearnside, P.M. Brazil’s Highway BR-319 Demonstrates a Crucial Lack of Environmental Governance in Amazonia. Environ. Conserv. 2021, 48, 161–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brando, P.; Macedo, M.; Silvério, D.; Rattis, L.; Paolucci, L.; Alencar, A.; Coe, M.; Amorim, C. Amazon Wildfires: Scenes from a Foreseeable Disaster. Flora 2020, 268, 151609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staal, A.; Flores, B.M.; Aguiar, A.P.D.; Bosmans, J.H.C.; Fetzer, I.; Tuinenburg, O.A. Feedback between Drought and Deforestation in the Amazon. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 044024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maqsood, M.H.; Mumtaz, R.; Khan, M.A. Deforestation Detection and Reforestation Potential Due to Natural Disasters—A Case Study of Floods. Remote Sens. Appl. 2024, 34, 101188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco, R.F.; Lippe, M.; Fischer, R.; Torres, B.; Tamayo, F.; Kalaba, F.K.; Kaoma, H.; Bugayong, L.; Günter, S. Reconciling Policy Instruments with Drivers of Deforestation and Forest Degradation: Cross-Scale Analysis of Stakeholder Perceptions in Tropical Countries. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fearnside, P.M.; Leal, N.; Fernandes, F.M. Rainforest Burning and the Global Carbon Budget: Biomass, Combustion Efficiency, and Charcoal Formation in the Brazilian Amazon. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 1993, 98, 16733–16743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, B.; Barreto, P.; Brandão, A.; Baima, S.; Gomes, P.H. Stimulus for Land Grabbing and Deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon. Environ. Res. Lett. 2019, 14, 064018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, W.D.; Mustin, K.; Hilário, R.R.; Vasconcelos, I.M.; Eilers, V.; Fearnside, P.M. Deforestation Control in the Brazilian Amazon: A Conservation Struggle Being Lost as Agreements and Regulations Are Subverted and Bypassed. Perspect. Ecol. Conserv. 2019, 17, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochedo, P.R.R.; Soares-Filho, B.; Schaeffer, R.; Viola, E.; Szklo, A.; Lucena, A.F.P.; Koberle, A.; Davis, J.L.; Rajão, R.; Rathmann, R. The Threat of Political Bargaining to Climate Mitigation in Brazil. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2018, 8, 695–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bizzo, E.; Michener, G. Forest Governance without Transparency? Evaluating State Efforts to Reduce Deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon. Environ. Policy Gov. 2017, 27, 560–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, S.; Gastauer, M.; Cavalcante, R.B.L.; Ramos, S.J.; Caldeira, C.F.; Silva, D.; Rodrigues, R.R.; Salomão, R.; Oliveira, M.; Souza-Filho, P.W.M.; et al. Challenges and Opportunities for Large-Scale Reforestation in the Eastern Amazon Using Native Species. Ecol. Manag. 2020, 466, 118120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Cruz, D.C.; Benayas, J.M.R.; Ferreira, G.C.; Santos, S.R.; Schwartz, G. An Overview of Forest Loss and Restoration in the Brazilian Amazon. New For. 2021, 52, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanches, R.A.; Futemma, C.R.T.; Alves, H.Q. Indigenous Territories and Governance of Forest Restoration in the Xingu River (Brazil). Land Use Policy 2021, 104, 104755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seymour, F.; Harris, N.L. Reducing Tropical Deforestation. Science 2019, 365, 756–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, K.; Amaral Neto, M.; Sousa, R.; Coelho, R. Manejo Florestal Sustentável Em Unidades de Conservação de Uso Comunitário Na Amazônia. Soc. Nat. 2020, 32, 778–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokorny, B.; Pacheco, P.; de Jong, W.; Entenmann, S.K. Forest Frontiers out of Control: The Long-Term Effects of Discourses, Policies, and Markets on Conservation and Development of the Brazilian Amazon. Ambio 2021, 50, 2199–2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]