Perceptions and Use of Urban Green Spaces, Leading Pathways to Urban Resilience

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

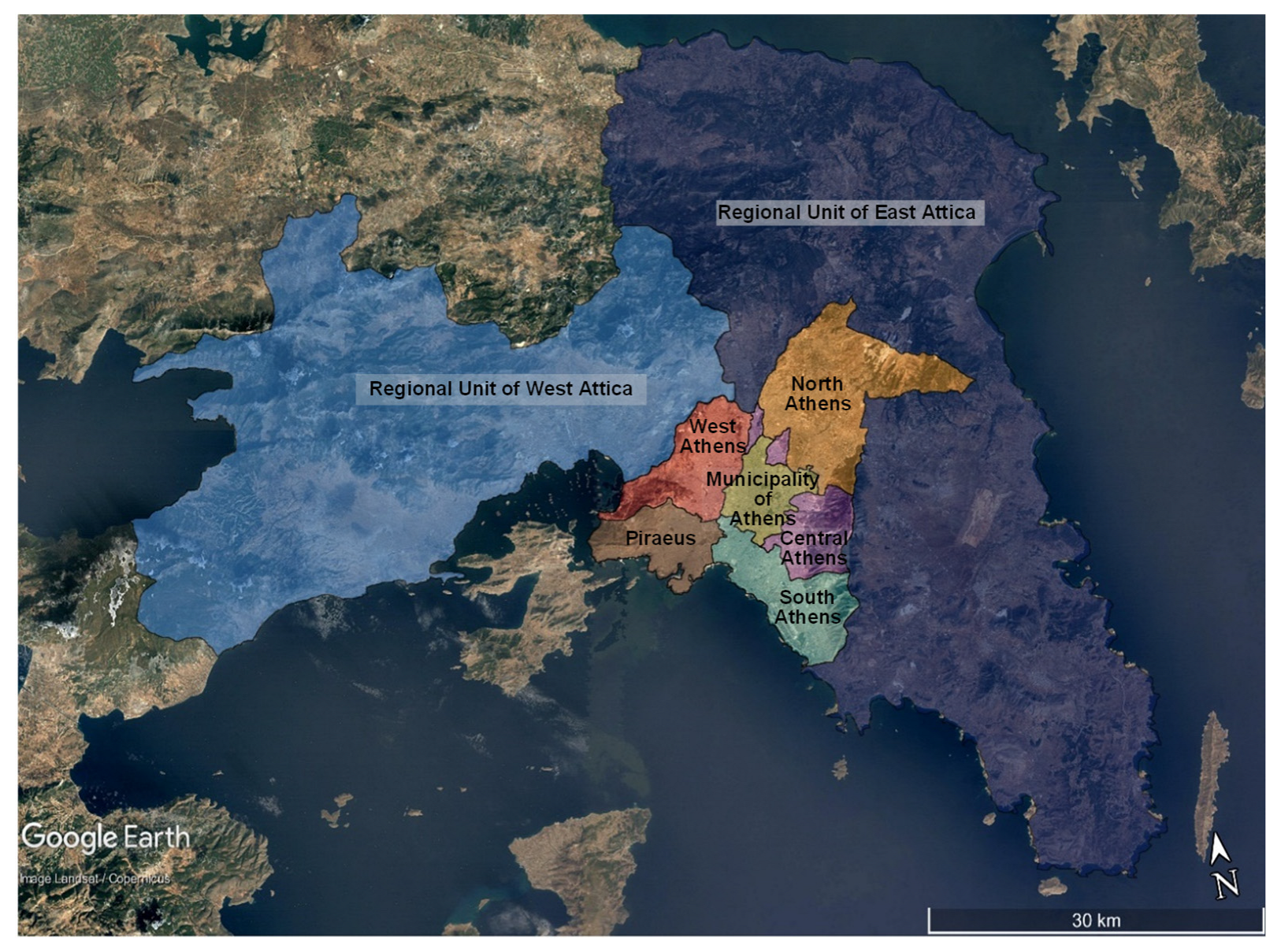

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Questionnaire Survey Content and Conduct

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Details

3.2. General Green Spaces

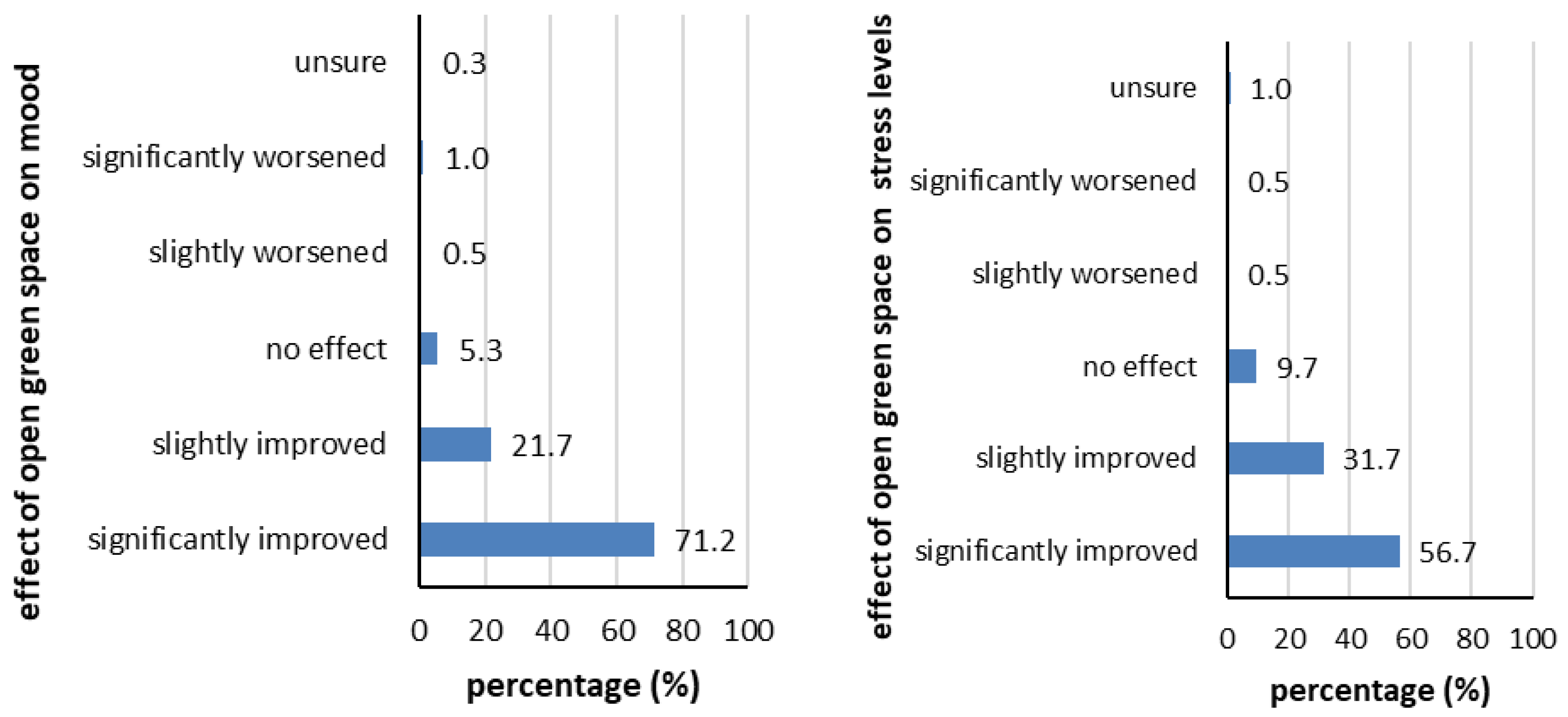

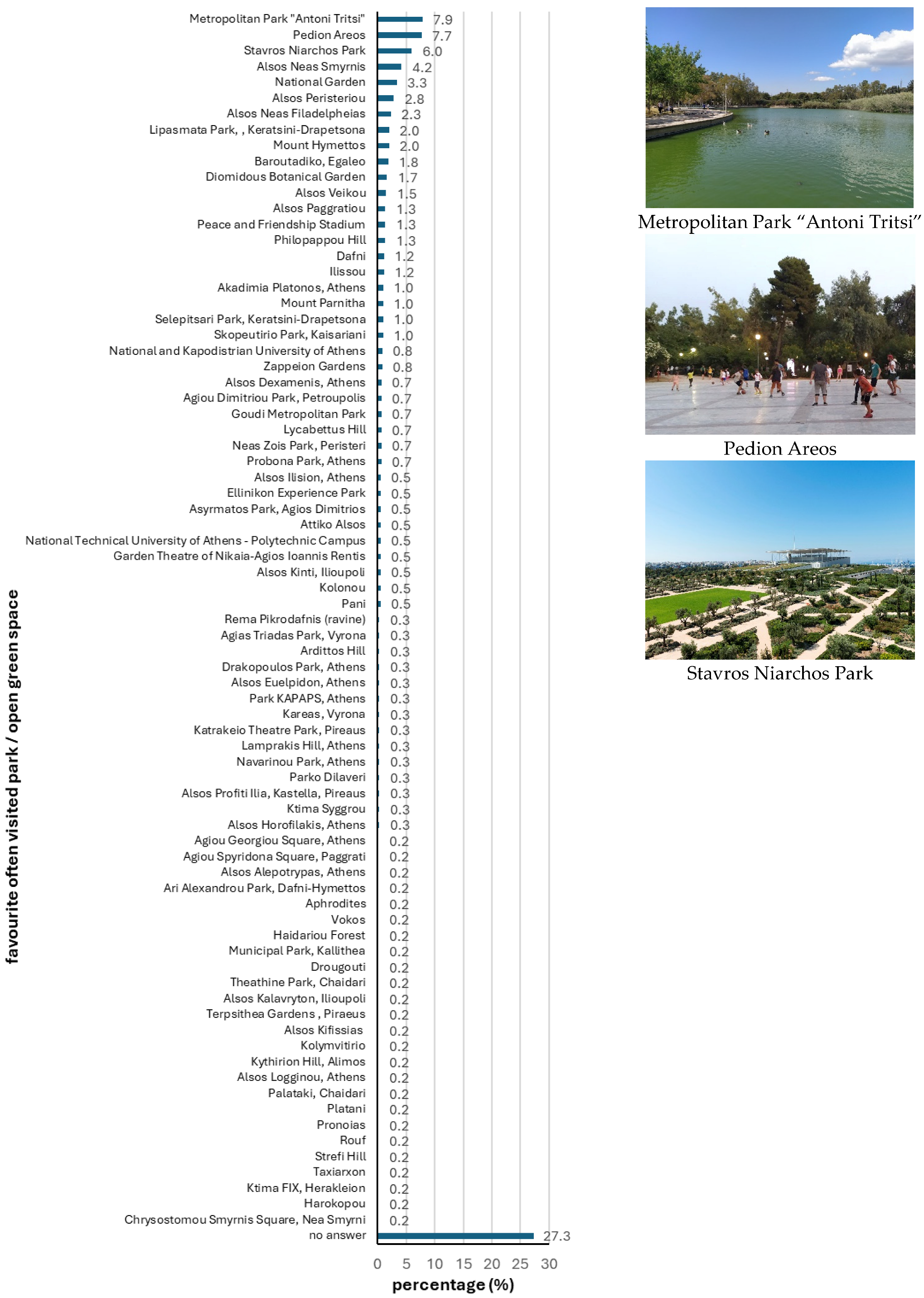

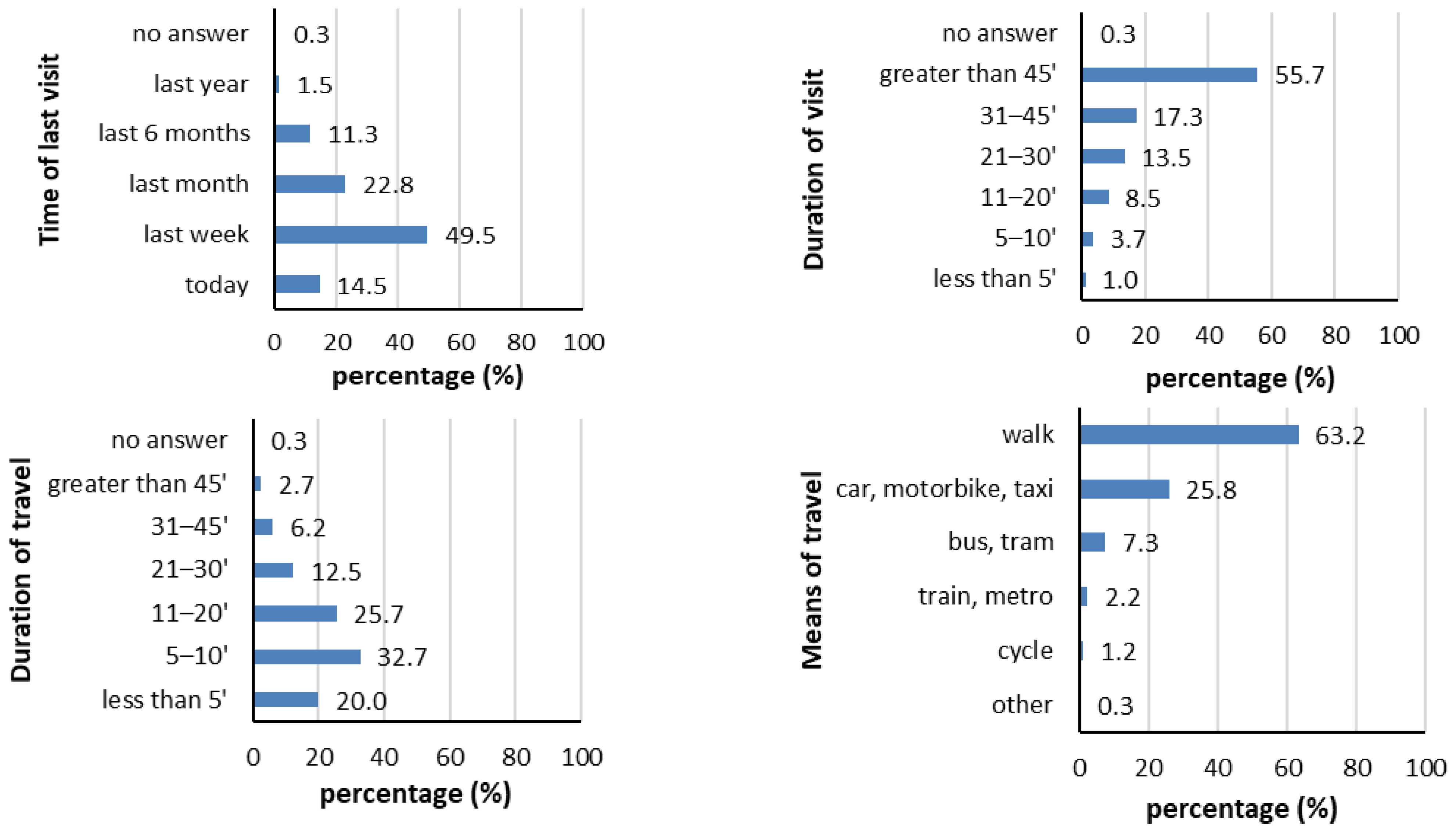

3.3. Particular Green Space

3.4. Effect of COVID-19 on the Use of Green Spaces

4. Discussion

4.1. Participant Details

4.2. General Green Spaces

4.3. Particular Green Space

4.4. Effect of COVID-19 on the Use of Green Spaces

5. Conclusions

- Consider Participant Demographics and Representation

- Address the Impact of Extreme Heat on Routine Activities in Public Spaces

- Consider Patterns of Green Space Use and User Preferences

- Address Barriers to Green Space Use

- Identify Spatial Inequalities and Protect Major Green Spaces

- Enhance Green Spaces to Address the Observed Impact of COVID-19

- Proposed Future Directions for Urban Green Space Design and Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations. Population, Development and the Environment 2013; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie, H. Urbanization. 2018. Available online: http://ourworldindata.org/urbanization (accessed on 17 July 2020).

- UN Habitat. World Cities Report 2020, The Value of Sustainable Urbanization; United Nations Human Settlements Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- UN. Sustainable Cities: Why They Matter. 2020. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/11_Why-It-Matters-2020.pdf (accessed on 3 September 2021).

- UN. United Nations General Assembly, Seventieth Session, Resolution Adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September 2015; A/RES/70/1; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- UN. United Nations General Assembly, Sixty-Ninth Session, Resolution Adopted by the General Assembly on 3 June 2015; A/RES/69/283; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- UN. United Nations General Assembly, Seventy-First Session, Resolution Adopted by the General Assembly on 23 December 2016; 71/256. New Urban Agenda. A/RES/71/256; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- UN. The Sustainable Development Report, 2021; United Nations Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- UN. United Nations Conference on Housing and Sustainable Urban Development, Habitat III Issue Papers; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lahoti, S.A.; Dhyani, S.; Saito, O. Exploring the Factors Shaping Urban Greenspace Interactions: A Case Study of Nagpur, India. Land 2024, 13, 1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dushkova, D.; Taherkhani, M.; Konstantinova, A.; Vasenev, V.I.; Dovletyarova, E.A. Understanding Factors Affecting the Use of Urban Parks Through the Lens of Ecosystem Services and Blue–Green Infrastructure: The Case of Gorky Park, Moscow, Russia. Land 2025, 14, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yu, Z.; Zhao, B.; Sun, R.; Vejre, H. Links between green space and public health: A bibliometric review of global research trends and future prospects from 1901 to 2019. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 63001–63037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN. Policy Brief: COVID-19 in an Urban World; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- UN Habitat. Cities and Pandemics: Towards a More Just, Green and Healthy Future; United Nations Human Settlements Programme; UN-Habitat: Nairobi, Kenya, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Konijnendijk, C.C. Promoting Health and Wellbeing Through Urban forests–Introducing the 3-30-300 Rule. IUCN, 2021. Available online: https://iucnurbanalliance.org/promoting-health-and-wellbeing-through-urban-forests-introducing-the-3-30-300-rule/ (accessed on 10 November 2024).

- Konijnendijk, C.C. Evidence-based guidelines for greener, healthier, more resilient neighbourhoods: Introducing the 3–30–300 rule. J. For. Res. 2023, 34, 821–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Zhang, F.; Li, X.; Wang, P.; Liang, J.; Mei, Y.; Cheng, W.; Qian, Y. Spatiotemporal Patterns of the Use of Urban Green Spaces and External Factors Contributing to Their Use in Central Beijing. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, T.; Xie, X.; Marušić, B.G. What Attracts People to Visit Community Open Spaces? A Case Study of the Overseas Chinese Town Community in Shenzhen, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Sun, F.; Che, Y. Public green spaces and human wellbeing: Mapping the spatial inequity and mismatching status of public green space in the Central City of Shanghai. Urban For. Urban Green. 2017, 27, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Z.; Bai, Y.; Geng, T. Examining Spatial Inequalities in Public Green Space Accessibility: A Focus on Disadvantaged Groups in England. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornaciari, M.; Muscas, D.; Rossi, F.; Filipponi, M.; Castellani, B.; Di Giuseppe, A.; Proietti, C.; Ruga, L.; Orlandi, F. CO2 Emission Compensation by Tree Species in Some Urban Green Areas. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.; Li, S.; Liu, Y.; Jin, C.; Zhou, L.; Gu, Y.; Gai, Z.; Liu, R.; Qiu, B. Using Social Media Text Data to Analyze the Characteristics and Influencing Factors of Daily Urban Green Space Usage—A Case Study of Xiamen, China. Forests 2023, 14, 1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paraskevopoulou, A.; Klados, A.; Malesios, C. Historical Public Parks: Investigating Contemporary Visitor Needs. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvia, G.; Pluchinotta, I.; Tsoulou, I.; Moore, G.; Zimmermann, N. Understanding Urban Green Space Usage through Systems Thinking: A Case Study in Thamesmead, London. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahoti, S.A.; Lahoti, A.; Dhyani, S.; Saito, O. Preferences and Perception Influencing Usage of Neighborhood Public Urban Green Spaces in Fast Urbanizing Indian City. Land 2023, 12, 1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudyal, N.C.; Hodges, D.G.; Merrett, C.D. A hedonic analysis of the demand for and benefits of urban recreation parks. Land Use Policy 2009, 26, 975–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, D.A.; Williamson, S.; Han, B. Gender Differences in Physical Activity Associated with Urban Neighborhood Parks: Findings from the National Study of Neighborhood Parks. Womens Health Issues 2021, 31, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fastl, C.; Arnberger, A.; Gallistl, V.; Steinm, V.K.; Dorner, T.E. Heat vulnerability: Health impacts of heat on older people in urban and rural areas in Europe. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 2024, 136, 507–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgakis, C.; Santamouris, M.; Kaisarlis, G. The Vertical Stratification of Air Temperature in the Center of Athens. J. Appl. Meteor. Climatol. 2010, 49, 1219–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ELSTAT. Urbanity—Mountainousness—Area/2021; Hellenic Statistical Authority: Athens, Greece, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ugolini, F.; Massetti, L.; Calaza-Martínez, P.; Cariñanos, P.; Dobbs, C.; Ostoic, S.K.; Marin, A.M.; Pearlmutter, D.; Saaroni, H.; Šaulienė, I.; et al. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the use and perceptions of urban green space: An international exploratory study. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 56, 126888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, B.; Kennedy, C.; Field, C.; McPhearson, T. Who benefits from urban green spaces during times of crisis? Perception and use of urban green spaces in New York City during the COVID-19 pandemic. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 65, 127354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biegańska, J.; Grzelak-Kostulska, E.; Kwiatkowski, M.A. A Typology of Attitudes towards the E-Bike against the Background of the Traditional Bicycle and the Car. Energies 2021, 14, 8430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burzyńska, J.; Rękas, M.; Januszewicz, P. Evaluating the Psychometric Properties of the eHealth Literacy Scale (eHEALS) among Polish Social Media Users. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppenheim, A.N. Questionnaire Design, Interviewing and Attitude Measurement, New ed; Pinter Publishers: London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Talal, M.L.; Santelmann, M.V. Visitor access, use, and desired improvements in urban parks. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 63, 127216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agathangelidis, I.; Cartalis, C.; Santamouris, M. Integrating Urban Form, Function, and Energy Fluxes in a Heat Exposure Indicator in View of Intra-Urban Heat Island Assessment and Climate Change Adaptation. Climate 2019, 7, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannopoulou, K.; Santamouris, M.; Livada, I.; Georgakis, C.; Caouris, Y. The Impact of Canyon Geometry on Intra Urban and Urban: Suburban Night Temperature Differences Under Warm Weather Conditions. Pure Appl. Geophys. 2010, 167, 1433–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; He, B.-J. Biophilic street design for urban heat resilience. Prog. Plan. 2025, 199, 100988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Xu, H.; He, H.; Wei, Q.; Yan, Y.; Chen, Z.; Li, X.; Zheng, J.; Li, T. A Spatial Analysis of Urban Streets under Deep Learning Based on Street View Imagery: Quantifying Perceptual and Elemental Perceptual Relationships. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannaros, C.; Agathangelidis, I.; Papavasileiou, G.; Galanaki, E.; Kotroni, V.; Lagouvardos, K.; Giannaros, T.M.; Cartalis, C.; Matzarakis, A. The extreme heat wave of July–August 2021 in the Athens urban area (Greece): Atmospheric and human-biometeorological analysis exploiting ultra-high resolution numerical modeling and the local climate zone framework. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 857, 159300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziliaskopoulos, K.; Petropoulos, C.; Laspidou, C. Enhancing Sustainability: Quantifying and Mapping Vulnerability to Extreme Heat Using Socioeconomic Factors at the National, Regional and Local Levels. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Powell, L.; Stamatakis, E.; McGreevy, P.; Podberscek, A.; Bauman, A.; Edwards, K. Is dog walking suitable for physical activity promotion? Investigating the exercise intensity of on-leash dog walking. Prev. Med. Rep. 2024, 41, 102716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramprabha, K. Consumer Shopping Behaviour and the Role of Women in Shopping—A Literature Review. RJSSM (Res. J. Soc. Sci. Manag.) 2017, 7, 50–63. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:148683683 (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- Li, L.; Lee, Y.; Lai, D.W.L. Mental Health of Employed Family Caregivers in Canada: A Gender-Based Analysis on the Role of Workplace Support. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 2022, 95, 470–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grigoryeva, A. Own Gender, Sibling’s Gender, Parent’s Gender: The Division of Elderly Parent Care among Adult Children. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2017, 82, 116–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, R.M.; Todisco, T.; Stacey, M.; Fujisawa, T.; Allerhand, M.; Woods, D.R.; Reynolds, R.M. Risk of heat illness in men and women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ. Res. 2019, 171, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannaros, C.; Agathangelidis, I.; Galanaki, E.; Cartalis, C.; Kotroni, V.; Lagouvardos, K.; Matzarakis, A. The HEAT-ALARMProject: Development of a Heat–HealthWarning Systemin Greece. Environ. Sci. Proc. 2023, 26, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, P.; Shi, D.; Helbich, M.; Sun, F.; Zhao, H.; Liu, Y.; Che, Y. Gender disparities in summer outdoor heat risk across China: Findings from a national county-level assessment during 1991–2020. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 921, 171120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Bell, S.; White, M.; Griffiths, A.; Darlow, A.; Taylor, T.; Wheeler, B.; Lovell, R. Spending time in the garden is positively associated with health and wellbeing: Results from a national survey in England. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2020, 200, 103836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalilnezhad, M.R.; Ugolini, F.; Massetti, L. Attitudes and Behaviors toward the Use of Public and Private Green Space during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Iran. Land 2021, 10, 1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, T.; Halleran, A. How our homes impact our health: Using a COVID-19 informed approach to examine urban apartment housing. Archnet-IJAR Int. J. Archit. Res. 2021, 15, 10–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotulla, T.; Denstadli, J.M.; Oust, A.; Beusker, E. What Does It Take to Make the Compact City Liveable for Wider Groups? Identifying Key Neighbourhood and Dwelling Features. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzymińska, A.; Bocianowski, J.; Mądrachowska, K. The use of plants on balconies in the city. Hort. Sci. 2020, 47, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aye, E.; Hackett, D.; Pozzuoli, C. The intersection of biophilia and engineering in creating sustainable, healthy and structurally sound built environments. WIT Trans. Ecol. Environ. 2019, 217, 663–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azimi, A.; Shafaat, A. Proposing design strategies for contemporary courtyards based on thermal comfort in cold and semi-arid climate zones. Build. Environ. 2024, 266, 112150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormick, G.R.; Rock, M.; Toohey, A.M.; Hignell, D. Characteristics of urban parks associated with park use and physical activity: A review of qualitative research. Health Place 2010, 16, 712–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Home, R.; Hunziker, M.; Bauer, N. Psychosocial Outcomes as Motivations for Visiting Nearby Urban Green Spaces. Leis. Sci. Interdiscip. J. 2012, 34, 350–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.-C.; Song, L.-Y. A case for inclusive design: Analyzing the needs of those who frequent Taiwan’s urban parks. Appl. Ergon. 2017, 58, 254–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, C.; Maruthaveeran, S.; Shahidan, M.F.; Chu, Y. Usage of and Barriers to Green Spaces in Disadvantaged Neighborhoods: A Case Study in Shi Jiazhuang, Hebei Province, China. Forests 2023, 14, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romelli, C.; Anderson, C.C.; Fagerholm, N.; Hansen, R.; Albert, C. Why do people visit or avoid public green spaces? Insights from an online map-based survey in Bochum, Germany. Ecosyst. People 2025, 21, 2454252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charreire, H.; Weber, C.; Chaix, B.; Salze, P.; Casey, R.; Banos, A.; Badariotti, D.; Kesse-Guyot, E.; Hercberg, S.; Simon, C.; et al. Identifying built environmental patterns using cluster analysis and GIS: Relationships with walking, cycling and body mass index in French adults. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2012, 9, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapousizis, G.; Sarker, R.; Baran Ulak, M.; Geurs, K. User acceptance of smart e-bikes: What are the influential factors? A cross-country comparison of five European countries. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2024, 185, 104106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakogiannis, E.; Siti, M.; Christodoulopoulou, G.; Karolemeas, C.; Kyriakidis, C. Cycling as a Key Component of the Athenian Sustainable Urban Mobility Plan. In Data Analytics: Paving the Way to Sustainable Urban Mobility, Proceedings of 4th Conference on Sustainable Urban Mobility (CSUM2018), Skiathos Island, Greece, 24–25 May 2018; Nathanail, E.G., Karakides, I.D., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 330–337. [Google Scholar]

- Kondo, M.C.; Fluehr, J.M.; Mckeon, T.; Branas, C.C. Urban Green Space and its impact on human health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grazuleviciene, R.; Vencloviene, J.; Kubilius, R.; Grizas, V.; Danileviciute, A.; Dedele, A.; Andrusaityte, S.; Vitkauskiene, A.; Steponaviciute, R.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J. Tracking Restoration of Park and Urban Street Settings in Coronary Artery Disease Patients. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Younis, A.; Qasim, M.; Riaz, A.; Ishaq, M.; Zulfiqar, F.; Farooq, A.; Hameed, M.; Abbas, H.; Aziz, S.; Hassan, F. Attitudes of citizens towards community involvement for development and maintenance of urban green spaces: A Faisalabad case study. Pak. J. Agri. Sci. 2018, 55, 73–82. [Google Scholar]

- Zong, M.; Xu, G.; Yanai, S. Building local partnership through community parks in Central Tokyo: Perspectives from different participants. Front. Sustain. Cities 2024, 6, 1445754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Z.; Lau, K.K.-L.; Roberts, A.C.; Chao, S.T.-Y.; Ng, E. Designing Urban Green Spaces for Older Adults in Asian Cities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinasson, K.G.S.; Shackleton, C.M.; Ruwanza, S.; Thondhlana, G. Contextual and socio-economic factors affected urban dwellers experiences of and vulnerability to ecosystem disservices. Sci. Afr. 2024, 26, e02404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talal, M.L.; Santelmann, M.V. Vegetation management for urban park visitors: A mixed methods approach in Portland, Oregon. Ecol. Appl. 2020, 30, e02079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, R.; Colbert, A.; Browning, M.; Jakub, K. Urban greenspace use among adolescents and young adults: An integrative review. Public Health Nurs. 2022, 39, 700–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, A.M. Pesticide exposure and women’s health. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2003, 44, 584–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bretveld, R.W.; Thomas, C.M.; Scheepers, P.T.; Zielhuis, G.A.; Roeleveld, N. Pesticide exposure: The hormonal function of the female reproductive system disrupted? Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2006, 31, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, A.M.; Camp, O.G.; Biernat, M.M.; Bai, D.; Awonuga, A.O.; Abu-Soud, H.M. Re-Evaluating the Use of Glyphosate-based Herbicides: Implications on Fertility. Reprod. Sci. 2025, 32, 950–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Sun, Z.; Du, M. Differences and Drivers of Urban Resilience in Eight Major Urban Agglomerations: Evidence from China. Land 2022, 11, 1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seaman, P.J.; Jones, R.; Ellaway, A. It’s not just about the park, it’s about integration too: Why people choose to use or not use urban greenspaces. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2010, 7, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, D.; Bo, M.; Zhou, Y. How Do the Young Perceive Urban Parks? A Study on Young Adults’ Landscape Preferences and Health Benefits in Urban Parks Based on the Landscape Perception Model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, I.; Weitkamp, G.; Yamu, C. Public Spaces as Knowledgescapes: Understanding the Relationship between the Built Environment and Creative Encounters at Dutch University Campuses and Science Parks. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibson, J.J. The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception; Houghton Miin: Boston, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Veitch, J.; Rivera, E.; Loh, V.; Paudel, C.; Biggs, N.; Deforche, B.; Timperio, A. Examining park features that encourage physical activity and social interaction among adults. Health Promot. Int. 2025, 40, daaf063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.P.; Alcock, I.; Grellier, J.; Wheeler, B.W.; Hartig, T.; Warber, S.L.; Bone, A.; Depledge, M.H.; Fleming, L.E. Spending at least 120 minutes a week in nature is associated with good health and wellbeing. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 7730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turunen, A.W.; Halonen, J.; Korpela, K.; Ojala, A.; Pasanen, T.; Siponen, T.; Tiittanen, P.; Tyrväinen, L.; Yli-Tuomi, T.; Lanki, T. Cross-sectional associations of different types of nature exposure with psychotropic, antihypertensive and asthma medication. Occup. Environ. Med. 2023, 80, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunter, M.C.R.; Gillespie, B.W.; Chen, S.Y.-P. Urban Nature Experiences Reduce Stress in the Context of Daily Life Based on Salivary Biomarkers. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Meo, I.; Becagli, C.; Cantiani, M.G.; Casagli, A.; Paletto, A. Citizens’ use of public urban green spaces at the time of the COVID-19 pandemic in Italy. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 77, 127739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patwary, M.M.; Bardhan, M.; İnan, H.E.; Browning, M.H.E.M.; Disha, A.S.; Haque, M.Z.; Helmy, M.; Ashraf, S.; Dzhambov, A.M.; Shuvo, F.K.; et al. Exposure to urban green spaces and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from two low and lower-middle-income countries. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1334425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, D.; Innes, J.; Wu, W.; Wang, G. Impacts of COVID-19 pandemic on urban park visitation: A global analysis. J. For. Res. 2021, 32, 553–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mouratidis, K.; Yiannakou, A. COVID-19 and urban planning: Built environment, health, and well-being in Greek cities before and during the pandemic. Cities 2022, 121, 103491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maury-Mora, M.; Gómez-Villarino, M.T.; Varela-Martínez, C. Urban green spaces and stress during COVID-19 lockdown: A case study for the city of Madrid. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 69, 127492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, A.I.; Triguero-Mas, M.; Santos, C.J.; Gómez-Nieto, A.; Cole, H.; Anguelovski, I.; Martins Silva, F.; Baró, F. Exposure to nature and mental health outcomes during COVID-19 lockdown. A comparison between Portugal and Spain. Environ. Int. 2021, 154, 106664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Questions | Response Options | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participant Details | |||||||

| 1. Participant’s residential neighbourhood located within the urban area of Attica’s basin; 2. Location of participant’s residence; 3. Complete your address or a nearby location (e.g., junction); 4. Age; 5. Gender; 6. Nationality; 7. Educational level; 8. Occupation; 9. Access to garden or yard; 10. Ownership of means of transport; 11. Number of children; 12. Number of pets | 1. yes—continue survey, no—exit survey; 2. West Athens (Agia Varvara, Agioi Anargyroi-Kamatero, Egaleo, Ilion, Peristeri, Petroupoli, Chaidari), Central Athens (Athens, Vyronas, Galatsi, Dafni-Hymettus, Zografou, Ilioupoli, Kaisariani, Filadelphia-Chalkidona), South Athens (Agios Dimitrios, Alimos, Glyfada, Elliniko-Argyroupoli, Kallithea, Moschato-Tavros, Nea Smyrni, Palaio Faliro), Piraeus (Piraeus, Keratsini-Drapetsona, Korydallos, Nikaia-Agios Ioannis Rentis, Perama); 3. open-ended; 4. years; 5. male, female, other, no answer; 6. Hellenic, other EC country, non-EC European country, non-European country, no answer; 7. primary, secondary, tertiary, other __________, no answer; 8. civil worker, employee, freelancer, pensioner, pupil, student, other __________, no answer; 9. yes, no, no answer; 10. yes, no, no answer; 11. none, one, two, three, four, five or more, no answer; 12. none, one, two, three or more, no answer. | ||||||

| General green spaces | |||||||

| 13. Have you stayed in an urban area of Attica’s basin during a period of extreme heat? | yes, no, no answer. | ||||||

| 14. Have you stayed in an urban area of Attica’s basin during a curfew period due to measures against the spread of COVID-19? | yes, no, no answer. | ||||||

| 15. Select up to three activities that the extreme heat makes it difficult for you to do in public spaces. | 1. walk; 2. exercise; 3. cycle; 4. walk the dog; 5. family play (children’s playground); 6. socialize—coffee-walk with friends; 7. cultural events; 8. work—going to work; 9. shopping; 10. other __________; 11. no answer. | ||||||

| 16. Which outdoor spaces do you currently feel you have easy and safe access to? (Select all that apply.) | 1. parks or small woodlands; 2. municipal or communal garden; 3. urban squares; 4. private yard or garden belonging to my household; 5. courtyard, veranda, balcony belonging to my household; 6. communal courtyard, garden or terrace; 7. sidewalk, 8. roads appropriately designed for 2-m social distancing measures; 9. cycle path; 10. natural area, e.g., forest area; 11. beach; 12. other __________; 13. nowhere; 14. no answer. | ||||||

| 17. The last time you were in an open green space, how was your mood affected? | 1. significantly improved; 2. slightly improved; 3. no effect; 4. slightly worsened; 5. significantly worsened; 6. unsure; 7. no answer | ||||||

| 18. The last time you visited an open green space, how did it affect your stress levels? | 1. significantly improved; 2. slightly improved; 3. no effect; 4. slightly worsened; 5. significantly worsened; 6. unsure; 7. no answer. | ||||||

| 19. What concerns you lately, or not, when visiting parks and open green spaces? (Select all that apply.) | 1. I don’t have easy access; 2. I feel uncomfortable from the heat; 3. it’s crowded; 4. it doesn’t meet my needs; 5. it’s not maintained; 6. visitors don’t follow hygiene and safety measures; 7. it’s not child-friendly; 8. it’s not open at the times I want and can go; 9. it doesn’t have sufficient lighting; 10. the use of chemicals for weed control; 11. it is under-staffed; 12. there is excessive police presence; 13. there is lack of security; 14. I don’t feel safe; 15.other __________; 16. none; 17. no answer. | ||||||

| 20. Do you have any additional safety concerns beyond those you selected in the previous question? | open-ended. | ||||||

| 21. What factors limit your visit to parks and open green spaces? | open-ended. | ||||||

| Particular green space | |||||||

| By the term “green spaces” we mean public or free and open to the public outdoor green spaces. For example, parks, urban and suburban forests, sports areas, playgrounds, green schoolyards or smaller spaces such as a vacant plot of land in the neighbourhood, a planted road island, a stream, a lake, a ravine, a seaside location, or anything else. | |||||||

| 22. Please now bring to mind your favourite green space that you visit often. Then note down some information about it so that we can understand exactly which place you are referring to. | 1. Name of the location ___________ [required]. 2. Street and number or nearest known point to the place ___________ [required]. 3. Municipality ___________. 4. Neighbourhood/district ____________. 5. Other useful information/description _____________ | ||||||

| 23. Select the value/function with the greatest importance for the place you mentioned. | 1. aesthetic value (e.g., view); 2. cultural value; 3. activities (e.g., sports); 4. health and well-being; 5. significant flora and fauna; 6. social value; 7. contact with nature; 8. refuge of coolness during extreme heat; 9. no answer. | ||||||

| 24. Do you visit this particular place on days with intense and prolonged extreme heat? Answer using the following scale where 1 means not at all and 5 means very much. | Scale (1 = not at all, 5 = very much); no answer. | ||||||

| 25. Select the most meaningful-to-you activity. | 1. walking; 2. running; 3. cycling; 4. sport without equipment; 5. sport requiring equipment; 6. walking the dog; 7. supervising children; 8. nature observation; 9. water activities; 10. relaxing; 11. social activities; 12. reading a book; 13. drinking coffee; 14. other ___________; 15. no answer. | ||||||

| 26. What are the greatest benefits of this activity? Select up to 3 answers. | 1. I enjoy nature; 2. I study nature; 3. I exercise; 4. I do something creative; 5. I decrease in stress; 6. I avoid crowds; 7. I communicate with my family; 8. I spend time with friends; 9. I think; 10. I rest and calm down; 11. I concentrate better; 12. I spend time outside the house; 13. other ___________; 14. no answer. | ||||||

| 27. How often do you usually engage in this activity in the particular place? Select only 1 answer. | 1. daily; 2. weekly; 3. monthly; 4. every six months; 5. annually; 6. never, proceed to question 30; 7. no answer, proceed to question 30. | ||||||

| 28. What is the usual duration of this activity in the particular place? Select only 1 answer. | 1. approximately 15 min; 2. approximately 30 min; 3. approximately 1 h; 4. from 1 to 3 h; 5. from 3 to 6 h; 6. more than 6 h; 7. no answer. | ||||||

| 29. What season do you mainly do this activity in the particular place? Select only 1 answer. | 1. all; 2. summer; 3. winter; 4. autumn; 5. spring; 6. no answer. | ||||||

| 30. When was the last time you visited the particular place? Select only one answer. | 1. today; 2. last week; 3. last month; 4. last 6 months; 5. last year; 6. no answer. | ||||||

| 31. How much time does it take to reach the particular place? | 1. < 5′; 2. 5–10′; 3. 11–20′; 4. 21–30′; 5. 31–45′; 6. >45′; 7. no answer. | ||||||

| 32. How long did you stay at this particular place the last time you visited it? | 1. < 5′; 2. 5–10′; 3. 11–20′; 4. 21–30′; 5. 31–45′; 6. >45′; 7. no answer. | ||||||

| 33. How do you usually reach this particular place? | 1. car, motorbike or taxi; 2. train or metro; 3. bus or tram; 4. cycle; 5. walk; 6. other ___________; 7. no answer. | ||||||

| Effect of COVID-19 on the use of green spaces | |||||||

| 34. Since the start of the COVID-19 crisis, how have your habits regarding the following activities changed, compared with what you did before? (select one answer per activity.) | |||||||

| I do not participate in this activity. | Started during the COVID-19 crisis. | Increased during the COVID-19 crisis. | No change. | Decreased during the COVID-19 crisis. | Stopped during the COVID-19 crisis. | No answer. | |

| visit parks or woodlands; | |||||||

| use shared open space (e.g., urban square, playground); | |||||||

| walking; | |||||||

| outdoor recreation (hiking, swimming, boating, cycling, etc.); | |||||||

| outdoor exercise (e.g., running, etc.); | |||||||

| walking the dog; | |||||||

| gardening; | |||||||

| bird and wildlife watching; | |||||||

| looking after indoor plants; | |||||||

| observing nature from the window. | |||||||

| Location of Residence (Q1–2) | Percentage | Participants’ Educational Level (Q7) | Number | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary | 4 | 0.7 | ||

| Secondary | 132 | 22.0 | |||

| Tertiary | 436 | 72.7 | |||

| Other | 19 | 3.2 | |||

| No answer | 9 | 1.5 | |||

| Participants’ Occupation (Q8) | Number | Percentage | |||

| Civil worker | 95 | 15.8 | |||

| Employee | 227 | 37.8 | |||

| Freelancer | 86 | 14.3 | |||

| Pensioner | 120 | 20.0 | |||

| Pupil | 6 | 1.0 | |||

| Student | 4 | 0.7 | |||

| Other (unemployed) | 11 | 1.8 | |||

| Other (household maintenance) | 4 | 0.7 | |||

| Other (not specified) | 17 | 2.8 | |||

| No answer | 32 | 5.3 | |||

| Participants’ Access to Garden or Yard (Q9) | Number | Percentage | |||

| Yes | 276 | 46.0 | |||

| No | 324 | 54.0 | |||

| Participants’ Owned Means of Transport (Q10) | Number | Percentage | |||

| Yes | 438 | 73.0 | |||

| No | 162 | 27.0 | |||

| Participants’ Age (Q4) | Percentage | Participants’ Number of Children (Q11) | Number | Percentage | |

| 0 | 274 | 45.7 | ||

| 1 | 134 | 22.3 | |||

| 2 | 152 | 25.3 | |||

| 3 | 28 | 4.7 | |||

| 4 | 5 | 0.8 | |||

| No answer | 7 | 1.2 | |||

| Participants’ Gender (Q5) | Number | Percentage | Participants’Number of Owned Pets (Q12) | Number | Percentage |

| Male | 315 | 52.5 | 0 | 423 | 70.5 |

| Female | 285 | 47.5 | 1 | 147 | 24.5 |

| Participants’ Nationality (Q6) | Number | Percentage | 2 | 22 | 3.7 |

| Hellenic | 595 | 99.2 | >3 | 3 | 0.5 |

| Other EC country | 3 | 0.5 | No answer | 5 | 0.8 |

| Non-EC European country | 0 | 0.0 | |||

| Non-European country | 2 | 0.3 | |||

| Age Groups | Activities | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Walk | Exercise | Cycle | Walk the Dog | Family Play (Children’s Playground) | |

| 15–24 yrs | 0.55 ± 0.094 | 0.41 ± 0.093 a | 0.14 ± 0.065 | 0.19 ± 0.090 | 0.07 ± 0.048 ab |

| 25–44 yrs | 0.72 ± 0.033 | 0.32 ± 0.034 ab | 0.05 ± 0.016 | 0.24 ± 0.027 | 0.19 ± 0.029 a |

| 45–64 yrs | 0.71 ± 0.027 | 0.21 ± 0.024 b | 0.04 ± 0.012 | 0.16 ± 0.025 | 0.13 ± 0.020 ab |

| >65 yrs | 0.78 ± 0.041 | 0.16 ± 0.037 b | 0.02 ± 0.014 | 0.34 ± 0.039 | 0.04 ± 0.020 b |

| F/p value | 2.045/0.106 ns | 5.553/0.001 *** | 2.492/0.059 ns | 2.570/0.053 ns | 4.693/0.003 ** |

| Socialize—Coffee, Walk with Friends | Cultural Events | Work— Going to Work | Shopping | ||

| 15–24 yrs | 0.38 ± 0.092 ab | 0.07 ± 0.048 | 0.48 ± 0.094 a | 0.28 ± 0.084 b | |

| 25–44 yrs | 0.33 ± 0.035 b | 0.11 ± 0.023 | 0.55 ± 0.037 a | 0.31 ± 0.034 b | |

| 45–64 yrs | 0.37 ± 0.029 ab | 0.14 ± 0.020 | 0.58 ± 0.029 a | 0.42 ± 0.029 ab | |

| >65 yrs | 0.54 ± 0.050 a | 0.15 ± 0.036 | 0.27 ± 0.044 b | 0.56 ± 0.050 a | |

| F/p value | 4.591/0.003 ** | 0.607/0.610 ns | 10.356/<0.001 *** | 6.672/<0.001 *** | |

| Gender | Activities | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Walk | Exercise | Cycle | Walk the Dog | Family Play (Children’s Playground) | |

| Male | 0.72 ± 0.025 | 0.31 ± 0.026 a | 0.05 ± 0.012 | 0.16 ± 0.020 b | 0.13 ± 0.019 |

| Female | 0.72 ± 0.027 | 0.17 ± 0.022 b | 0.04 ± 0.012 | 0.28 ± 0.027 a | 0.14 ± 0.020 |

| F/p value | 0.008/0.964 ns | 65.430/<0.001 *** | 0.423/0.745 ns | 55.009/<0.001 *** | 0.507/0.722 ns |

| Socialize—Coffee, Walk with Friends | Cultural Events | Work— Going to Work | Shopping | ||

| Male | 0.38 ± 0.027 | 0.12 ± 0.018 | 0.53 ± 0.028 | 0.35 ± 0.027 b | |

| Female | 0.39 ± 0.029 | 0.14 ± 0.021 | 0.49 ± 0.030 | 0.47 ± 0.030 a | |

| F/p value | 0.361/0.763 ns | 2.799/0.403 ns | 0.606/0.382 ns | 25.261/0.003 ** | |

| Age Groups | Outdoor Spaces | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parks/ Small Woodlands | Municipal or Communal Gardens | Urban Squares | Household Private Yard or Garden | Household Courtyard, Veranda, Balcony | Communal Courtyard, Garden or Terrace | |

| 15–24 yrs | 0.45 ± 0.094 ab | 0.31 ± 0.087 | 0.79 ± 0.077 a | 0.21 ± 0.077 | 0.76 ± 0.081 | 0.24 ± 0.081 a |

| 25–44 yrs | 0.65 ± 0.035 a | 0.18 ± 0.029 | 0.56 ± 0.037 b | 0.18 ± 0.029 | 0.58 ± 0.036 | 0.21 ± 0.030 ab |

| 45–64 yrs | 0.53 ± 0.030 ab | 0.14 ± 0.029 | 0.54 ± 0.030 b | 0.22 ± 0.024 | 0.58 ± 0.029 | 0.13 ± 0.020 ab |

| >65 yrs | 0.47 ± 0.050 b | 0.15 ± 0.036 | 0.50 ± 0.050 b | 0.19 ± 0.039 | 0.64 ± 0.048 | 0.07 ± 0.025 b |

| F/p value | 4.013/0.008 ** | 2.285/0.078 ns | 2.706/0.045 * | 0.310/0.818 ns | 1.573/0.195 ns | 4.383/0.005 ** |

| Sidewalk | Roads Appropriately Designed for 2 m Social Distancing Measures | Cycle Path | Natural Area, e.g., Forest Area | Beach | ||

| 15–24 yrs | 0.45 ± 0.094 a | 0.14 ± 0.065 a | 0.10 ± 0.058 | 0.41 ± 0.093 a | 0.21 ± 0.077 | |

| 25–44 yrs | 0.24 ± 0.032 b | 0.06 ± 0.018 ab | 0.06 ± 0.017 | 0.21 ± 0.030 b | 0.25 ± 0.032 | |

| 45–64 yrs | 0.23 ± 0.025 b | 0.03 ± 0.010 b | 0.05 ± 0.013 | 0.15 ± 0.021 b | 0.29 ± 0.027 | |

| >65 yrs | 0.20 ± 0.040 b | 0.04 ± 0.020 b | 0.03 ± 0.017 | 0.13 ± 0.033 b | 0.31 ± 0.046 | |

| F/p value | 2.731/0.043 ** | 2.707/0.044 ** | 0.948/0.417 ns | 5.433/0.001 ** | 0.603/0.614 ns | |

| Gender | Outdoor Spaces | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parks/ Small Woodlands | Municipal or Communal Gardens | Urban Squares | Household Private Yard or Garden | Household Courtyard, Veranda, Balcony | Communal Courtyard, Garden or Terrace | |

| Male | 0.57 ± 0.028 | 0.16 ± 0.021 | 0.59 ± 0.028 a | 0.21 ± 0.023 | 0.58 ± 0.028 | 0.14 ± 0.019 |

| Female | 0.53 ± 0.030 | 0.16 ± 0.022 | 0.51 ± 0.030 b | 0.19 ± 0.023 | 0.61 ± 0.029 | 0.16 ± 0.022 |

| F/p value | 2.566/0.391 ns | 0.168/0.838 ns | 10.232/0.03 * | 2.012/0.480 ns | 2.213/0.456 ns | 2.181/0.460 ns |

| Sidewalk | Roads Appropriately Designed for 2 m Social Distancing Measures | Cycle Path | Natural Area, e.g., Forest Area | Beach | ||

| Male | 0.26 ± 0.025 | 0.05 ± 0.013 | 0.07 ± 0.14 a | 0.17 ± 0.021 | 0.29 ± 0.026 | |

| Female | 0.22 ± 0.024 | 0.04 ± 0.012 | 0.03 ± 0.10 b | 0.18 ± 0.023 | 0.26 ± 0.026 | |

| F/p value | 5.219/0.256 ns | 1.834/0.499 ns | 1.987/0.483 ns | 0.077/0.889 ns | 0.603/0.614 ns | |

| Age Groups | Concerns | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I do not have easy access | I feel uncomfortable from the heat | It is crowded | It does not meet my needs | It is not maintained | Visitors do not follow hygiene and safety measures | It is not child-friendly | |

| 15–24 yrs | 0.14 ± 0.065 | 0.17 ± 0.071 | 0.21 ± 0.077 | 0.31 ± 0.087 a | 0.59 ± 0.093 | 0.48 ± 0.094 | 0.10 ± 0.058 |

| 25–44 yrs | 0.14 ± 0.025 | 0.18 ± 0.029 | 0.25 ± 0.032 | 0.10 ± 0.022 b | 0.50 ± 0.037 | 0.30 ± 0.034 | 0.09 ± 0.021 |

| 45–64 yrs | 0.20 ± 0.024 | 0.20 ± 0.024 | 0.21 ± 0.024 | 0.13 ± 0.020 b | 0.52 ± 0.030 | 0.33 ± 0.028 | 0.06 ± 0.014 |

| >65 yrs | 0.15 ± 0.036 | 0.16 ± 0.037 | 0.18 ± 0.038 | 0.12 ± 0.032 b | 0.47 ± 0.050 | 0.33 ± 0.047 | 0.04 ± 0.020 |

| F/p value | 1.186/0.314 ns | 0.363/0.780 ns | 0.786/0.502 ns | 3.479/0.016 * | 0.556/0.645 ns | 1.230/0.298 ns | 1.165/0.322 ns |

| It is not open at the times I want and can go | It does not have sufficient lighting | The use of chemicals for weed control | It is under-staffed | There is excessive police presence | There is lack of security | I do not feel safe | |

| 15–24 yrs | 0.10 ± 0.058 | 0.34 ± 0.090 | 0.07 ± 0.048 | 0.34 ± 0.090 a | 0.07 ± 0.048 | 0.41 ± 0.093 | 0.24 ± 0.081 |

| 25–44 yrs | 0.05 ± 0.017 | 0.36 ± 0.035 | 0.01 ± 0.008 | 0.18 ± 0.029 b | 0.05 ± 0.016 | 0.30 ± 0.034 | 0.17 ± 0.028 |

| 45–64 yrs | 0.07 ± 0.015 | 0.29 ± 0.027 | 0.03 ± 0.010 | 0.13 ± 0.020 b | 0.04 ± 0.012 | 0.41 ± 0.029 | 0.25 ± 0.026 |

| >65 yrs | 0.05 ± 0.022 | 0.21 ± 0.041 | 0.01 ± 0.010 | 0.10 ± 0.030 b | 0.06 ± 0.024 | 0.35 ± 0.048 | 0.17 ± 0.037 |

| F/p value | 0.478/0.697 ns | 2.588/0.052 ns | 1.771/0.152 ns | 4.443/0.004 ** | 0.258/0.856 ns | 2.359/0.071 ns | 1.817/0.143 ns |

| Gender | Concerns | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I do not have easy access | I feel uncomfortable from the heat | It is crowded | It does not meet my needs | It is not maintained | Visitors do not follow hygiene and safety measures | It is not child-friendly | |

| Male | 0.15 ± 0.020 | 0.15 ± 0.020 b | 0.21 ± 0.023 | 0.15 ± 0.020 | 0.51 ± 0.028 | 0.31 ± 0.026 | 0.08 ± 0.015 |

| Female | 0.19 ± 0.023 | 0.23 ± 0.025 a | 0.23 ± 0.025 | 0.11 ± 0.018 | 0.50 ± 0.030 | 0.35 ± 0.028 | 0.06 ± 0.014 |

| F/p value | 5.824/0.228 ns | 27.148/0.010 * | 0.820/0.651 ns | 7.538/0.174 ns | 0.130/0.819 ns | 3.505/0.346 ns | 1.563/0.533 ns |

| It is not open at the times I want and can go | It does not have sufficient lighting | The use of chemicals for weed control | It is under-staffed | There is excessive police presence | There is lack of security | I do not feel safe | |

| Male | 0.06 ± 0.014 | 0.28 ± 0.025 | 0.01 ± 0.005 b | 0.16 ± 0.020 | 0.04 ± 0.011 | 0.37 ± 0.027 | 0.19 ± 0.022 |

| Female | 0.06 ± 0.014 | 0.33 ± 0.028 | 0.04 ± 0011. a | 0.15 ± 0.021 | 0.06 ± 0.014 | 0.37 ± 0.029 | 0.23 ± 0.025 |

| F/p value | 0.152/0.845 ns | 9.066/0.129 ns | 0.311/0.032 * | 2.879/0.781 ns | 0.029/0.397 ns | 7.101/0.933 ns | 2.138/0.183 ns |

| Age Groups | Greatest Benefits | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I enjoy nature | I study nature | I can exercise | I do something creative | I decrease in stress | I avoid crowds | |

| 15–24 yrs | 0.31 ± 0.087 | 0.03 ± 0.034 | 0.31 ± 0.087 | 0.17 ± 0.071 a | 0.52 ± 0.094 | 0.00 ± 0.000 |

| 25–44 yrs | 0.38 ± 0.036 | 0.03 ± 0.012 | 0.28 ± 0.033 | 0.05 ± 0.017 b | 0.55 ± 0.037 | 0.05 ± 0.016 |

| 45–64 yrs | 0.46 ± 0.030 | 0.04 ± 0.011 | 0.31 ± 0.027 | 0.06 ± 0.014 b | 0.56 ± 0.029 | 0.09 ± 0.017 |

| >65 yrs | 0.42 ± 0.049 | 0.02 ± 0.014 | 0.30 ± 0.046 | 0.01 ± 0.010 b | 0.46 ± 0.050 | 0.11 ± 0.031 |

| F/p value | 1.427/0.234 ns | 0.347/0.791 ns | 0.143/0.934 ns | 3.933/0.009 ** | 1.258/0.288 ns | 2.276/0.079 ns |

| I communicate with my family | I spend time with friends | I think | I rest and calm down | I concentrate better | I spend time outside the house | |

| 15–24 yrs | 0.07 ± 0.048 a | 0.38 ± 0.092 a | 0.03 ± 0.034 | 0.41 ± 0.093 | 0.07 ± 0.048 | 0.38 ± 0.092 |

| 25–44 yrs | 0.15 ± 0.026 ab | 0.24 ± 0.032 ab | 0.11 ± 0.023 | 0.39 ± 0.036 | 0.05 ± 0.016 | 0.25 ± 0.032 |

| 45–64 yrs | 0.08 ± 0.016 ab | 0.12 ± 0.019 b | 0.18 ± 0.023 | 0.44 ± 0.029 | 0.10 ± 0.018 | 0.21 ± 0.024 |

| >65 yrs | 0.01 ± 0.010 b | 0.12 ± 0.032 b | 0.16 ± 0.037 | 0.43 ± 0.049 | 0.08 ± 0.027 | 0.28 ± 0.045 |

| F/p value | 5.748/0.001 ** | 7.643/<0.001 *** | 2.401/0.067 ns | 0.348/0.790 ns | 1.452/0.227 ns | 1.911/0.127 ns |

| Gender | Greatest Benefits | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I enjoy nature | I study nature | I can exercise | I do something creative | I decrease in stress | I avoid crowds | |

| Male | 0.41 ± 0.028 | 0.03 ± 0.009 | 0.33 ± 0.027 | 0.06 ± 0.013 | 0.56 ± 0.028 | 0.07 ± 0.014 |

| Female | 0.43 ± 0.029 | 0.04 ± 0.011 | 0.26 ± 0.026 | 0.05 ± 0.013 | 0.52 ± 0.030 | 0.09 ± 0.017 |

| F/p value | 0.825/0.646 ns | 3.408/0.357 ns | 13.002/0.073 ns | 0.661/0.685 ns | 2.877/0.334 ns | 3.752/0.334 ns |

| I communicate with my family | I spend time with friends | I think | I rest and calm down | I concentrate better | I spend time outside the house | |

| Male | 0.09 ± 0.016 | 0.16 ± 0.021 | 0.15 ± 0.020 | 0.40 ± 0.028 | 0.06 ± 0.014 | 0.24 ± 0.024 |

| Female | 0.09 ± 0.017 | 0.18 ± 0.023 | 0.14 ± 0.021 | 0.45 ± 0.030 | 0.10 ± 0.018 | 0.24 ± 0.025 |

| F/p value | 0.040/0.921 ns | 1.771/0.506 ns | 0.023/0.940 ns | 6.571/0.168 ns | 9.934/0.118 ns | 0.002/0.981 ns |

| Age Groups | Frequency 1 | Gender | Frequency 1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 15–24 yrs | 2.10 ± 0.194 a | Male | 2.15 ± 0.054 |

| 25–44 yrs | 2.49 ± 0.081 ab | Female | 2.30 ± 0.066 |

| 45–64 yrs | 2.16 ± 0.056 ab | ||

| >65 yrs | 1.94 ± 0.104 b | ||

| F/p value | 7.233/<0.001 *** | F/p value | 11.922/0.078 ns |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Paraskevopoulou, A.T.; Mougiakou, E.; Malesios, C. Perceptions and Use of Urban Green Spaces, Leading Pathways to Urban Resilience. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10093. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210093

Paraskevopoulou AT, Mougiakou E, Malesios C. Perceptions and Use of Urban Green Spaces, Leading Pathways to Urban Resilience. Sustainability. 2025; 17(22):10093. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210093

Chicago/Turabian StyleParaskevopoulou, Angeliki T., Eleni Mougiakou, and Chrysovalantis Malesios. 2025. "Perceptions and Use of Urban Green Spaces, Leading Pathways to Urban Resilience" Sustainability 17, no. 22: 10093. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210093

APA StyleParaskevopoulou, A. T., Mougiakou, E., & Malesios, C. (2025). Perceptions and Use of Urban Green Spaces, Leading Pathways to Urban Resilience. Sustainability, 17(22), 10093. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210093