Abstract

Sustainable development in rural communities faces significant challenges, such as inadequate infrastructure, poor resource management, and weak governance, especially in developing countries like Peru. This study aimed to develop a management model tailored to the local needs of smallholder communities in the Junín region, Peru, addressing social, economic, and environmental dimensions to improve quality of life. Using a descriptive mixed-method design with non-experimental and cross-sectional methods, 60 smallholder communities were evaluated based on criteria of access to information and relevance to sustainable development. Data collected through structured surveys and semi-structured interviews revealed a lack of inclusive participation, insufficient economic income, lack of financial transparency, and inadequate environmental practices. The proposed management model integrates strategies to improve community governance, foster inclusive participation, promote sustainable economic practices, and conserve the environment. It concludes that a comprehensive, flexible, and locally adapted approach, emphasizing transparency and community participation, is essential to achieving long-term sustainability in smallholder communities.

1. Introduction

Sustainable development in rural communities represents one of the most pressing challenges in balancing economic viability, social equity, and environmental stewardship. These communities face complex and interrelated obstacles, including inadequate infrastructure, inefficient resource management, and fragile governance structures. In countries such as Peru, many rural territories continue to rely on traditional agricultural systems which, although culturally significant, do not always guarantee economic stability or environmental protection [1]. Furthermore, limited access to essential services such as potable water, sanitation, and healthcare restricts economic opportunities and deepens the rural–urban divide, undermining the quality of life and reinforcing socio-economic disparities [2,3].

In the Peruvian Andes, persistent infrastructure deficits remain a central barrier to sustainability. Restricted access to basic services not only affects public health but also constrains agricultural productivity and local economic development [4]. This situation is particularly critical in regions such as Junín, where community-based natural resource management is widespread but often weakened by insufficient technical training and scarce access to sustainable technologies [5].

Governance and land management also pose fundamental challenges for sustainable rural development. The concentration of land ownership, combined with weak regulatory frameworks, reinforces inequality and limits institutional effectiveness [6,7]. Likewise, restricted participation in decision-making processes weakens collective governance and slows the adoption of resilient agricultural and environmental practices [8,9]. Economic diversification is also essential, as dependence on traditional agriculture increases vulnerability to climate variability and market fluctuations [10]. Although alternative livelihoods—such as rural tourism and sustainable agriculture—are increasingly promoted, many initiatives fail due to limited planning and unequal benefit-sharing [5,11,12]. Integrated and participatory management models are therefore vital to strengthening local capacities. By empowering community actors and incorporating indigenous knowledge into planning, these approaches enhance ownership and long-term sustainability of development processes [13,14,15].

Given this context, the present study aims to develop a management model to promote sustainable development in rural communities in the central highlands of Peru, addressing social, economic, and environmental dimensions to improve quality of life. Specifically, it seeks to (1) conduct a comprehensive diagnosis of community organisation, participation, and resource use; (2) identify and analyse the main social, economic, and environmental factors affecting sustainability; and (3) propose a governance-centred management model adapted to local needs that fosters sustainable, equitable, and participatory development.

1.1. Sustainable Development and Community Resilience in Rural Andean Peru

Sustainable development and community resilience in rural Andean Peru are deeply shaped by the intersection of cultural heritage, environmental dynamics, and socio-economic structures. Religious values and cooperative principles exemplified by the Comunidad Evangélica Andina de Granja Porcón demonstrate how spiritual frameworks can strengthen social cohesion while simultaneously supporting sustainable livelihoods. This integration of spiritual and economic needs provides a replicable model for other rural communities facing similar challenges [16]. Traditional Andean concepts such as verticality, complementarity, and reciprocity have historically underpinned agricultural resilience, enabling communities to adapt to ecological and economic vulnerabilities [17].

Ancestral practices, as a form of social capital, play a decisive role in disaster preparedness and recovery. In the Colca Valley, for instance, traditional systems have bridged the gap between governmental disaster management and local adaptation strategies, ensuring community-led responses that are contextually relevant [18]. Similarly, the Parque de la Papa in Cusco illustrates the potential of integrating indigenous knowledge with scientific collaboration to address climate change, preserve biocultural heritage, and strengthen food systems [19]. Community-led sustainable care models proposed for regions such as Amazonas, La Libertad, and Moquegua highlight the value of harnessing local capacities for self-managed development, with emphasis on the social and cultural determinants of well-being [20]. Despite these promising models, rural Andean communities continue to face the persistent challenges of climatic variability, marginalisation, and restricted access to resources, further exacerbated by neoliberal policy frameworks and global economic pressures [21].

1.2. Community Management Models and Participatory Governance in Rural Peru

The 1969 Agrarian Reform marked a turning point by granting collective land titles to legally recognised communities, fundamentally reshaping social organisation and the governance of communal lands. The case of Llanchu in Cusco exemplifies how this legal recognition has enhanced community empowerment and autonomy, enabling effective resource management and the preservation of rural livelihoods [22]. Building upon these legal foundations, initiatives such as Sierra Productiva have demonstrated how territorial autonomy, organisational capacity, and control over resources and technologies can foster local development and reinforce food sovereignty [23].

Women’s participation in governance, although still constrained, is vital to community development, as they play key roles in agricultural and livestock activities, contributing not only to the local economy but also to cultural continuity [20]. Large-scale infrastructure projects, such as Peru’s Programa de Caminos Rurales, have successfully incorporated community participation into planning and execution, improving local governance, enhancing transparency, and strengthening civic engagement [24]. Participatory governance mechanisms like presupuesto participativo have gained prominence across Latin America, including Peru, as tools to ensure citizens’ direct involvement in public decision-making, signalling a shift toward more inclusive and democratic governance [25].

Social movements advocating for rural development models rooted in food sovereignty—often in opposition to neoliberal economic policies—have further reinforced participatory governance at the grassroots level [26]. Communal land management practices in communities such as San Roque de Huarmitá illustrate the effectiveness of self-governance, where usufruct rights are prioritised for their direct benefits to families [27].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

The study was conducted in the Junín region, located in the central highlands of Peru, which comprises a total of 403 officially registered rural smallholder communities according to the Sistema de Información sobre Comunidades Campesinas del Perú [28]. These are distributed across eight provinces: Chupaca (28 communities), Concepción (66), Huancayo (133), Jauja (89), Junín (15), Satipo (1), Tarma (53), and Yauli (18).

The region presents diverse ecological and socio-economic conditions, ranging from high Andean plateaus to inter-Andean valleys, and is characterised by mixed subsistence and market-oriented agricultural systems. The research area was selected due to its strategic importance for regional food security, socio-economic development, and environmental sustainability, as well as the presence of significant governance and organisational challenges.

2.2. Research Design

A mixed-methods descriptive design was employed, combining quantitative and qualitative approaches under a non-experimental, cross-sectional framework. This design allowed for an integrated analysis of social, economic, environmental, organisational, and governance dimensions in the selected communities, and for capturing both numerical trends and in-depth perceptions of stakeholders.

2.3. Sampling Strategy

From the total population of 403 officially registered smallholder communities in the Junín region—a territory with approximately 1.25 million inhabitants [29]—a stratified purposive sampling design was applied to ensure representativeness while maintaining operational feasibility. The communities were first grouped by province, ecological zone (high Andean plateau, inter-Andean valley, and jungle foothill), and dominant economic activity (agriculture, livestock, or mixed). Within these strata, specific communities were purposively selected in consultation with specialists from the Dirección Regional de Agricultura de Junín (DRAJ), considering their knowledge of local governance and development dynamics. Selection criteria included the following:

- Accessibility of information and logistical feasibility, accounting for geographic constraints and infrastructure conditions.

- Active participation of community members in decision-making processes, to incorporate cases with functioning and emergent governance systems.

- Relevance to sustainable development initiatives, ensuring alignment with ongoing or potential community-based projects.

This procedure resulted in a final sample of 60 communities, which collectively represent the main socio-ecological, cultural, and economic diversity across the eight provinces of Junín. Within each selected community, three respondents were surveyed: one local authority and two residents (communal members). This configuration ensured both institutional and citizen-level representation, capturing governance and social perspectives at the community scale.

Although the total population of Junín exceeds 1.2 million inhabitants, the analytical universe of this study comprised the 403 organised smallholder communities that constitute the formal rural structure of the region. According to Cochran’s formula adjusted for a finite population, the selected 60 communities correspond to a 95% confidence level with a margin of error of approximately ±11.7%. At the individual level, the 180 respondents yield an estimated margin of error of ±7.3%, ensuring adequate precision for regional-scale social research. This stratified purposive approach provided both conceptual representation of the regional context and practical feasibility for fieldwork, minimising potential selection bias while ensuring statistical robustness and external validity.

2.4. Data Collection and Instrument

Two complementary instruments were applied. The first was a structured survey administered to one authority and two residents per community, covering five analytical dimensions: (1) Social participation and equity, (2) Economic development and transparency, (3) Environmental management and sustainability, (4) Community organisation and governance, and (5) Organic life and rights awareness. Each dimension was operationalised through multiple indicators, measured on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = very low to 5 = very high perception/agreement).

The second instrument consisted of semi-structured interviews conducted with local authorities from each of the 60 sampled communities. The interviews aimed to explore community perceptions regarding governance mechanisms, decision-making processes, resource allocation, and strategic priorities related to sustainable development. Each interview lasted approximately 30–45 min and was recorded and transcribed verbatim with the participants’ consent.

The structured survey was subjected to a two-stage validation process. First, content validity was assessed by a panel of five experts in rural development, governance, and Andean socio-cultural systems, who evaluated the clarity, relevance, and cultural adequacy of each item. The Content Validity Index (CVI) exceeded 0.85 for all items. Second, a pilot study was conducted with two comunidades campesinas outside the sample frame (n = 20 respondents), allowing refinement of wording and response options. Reliability analysis using Cronbach’s alpha yielded coefficients between 0.82 and 0.91 across dimensions, indicating high internal consistency.

2.5. Dimensional Analysis

For each of the five analytical dimensions—Social (S), Economic (E), Environmental (A), Organisational (O), and Values & Rights Awareness (VO)—the item-level responses on the Likert scale were standardised to a 0–100 range, where higher values represented more favourable perceptions. The index for each dimension was calculated as the arithmetic mean of the standardised items belonging to that dimension:

where Dj is the score for dimension j, nj is the number of items in that dimension, and xij is the normalised score of item i. The global Community Sustainability and Resilience Index (C-SRI) was then obtained as the mean of the five dimension-specific indices:

2.6. Data Analysis

Quantitative data from structured surveys were coded and processed using descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, and frequency distributions) to summarise responses per indicator and dimension. Inferential analysis was conducted using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (ρ) to examine the strength and direction of associations among the five sustainability dimensions and the overall Community Sustainability and Resilience Index (C-SRI). This non-parametric method was selected because the data originated from Likert-type scales, which may not meet the assumptions of normality required for parametric tests. Correlation matrices and significance values were computed using the packages Hmisc (for rcorr function) and corrplot (for visualisation), while data handling and transformations were performed with dplyr and tidyverse. The qualitative material was subsequently examined through a systematic thematic content analysis, identifying recurrent concepts and their relationships across the five sustainability dimensions. The coding process was carried out inductively, and emerging terms were grouped into conceptual categories representing the Social, Economic, Environmental, Organisational, and Values domains. To visualise these relationships, a thematic co-occurrence network was constructed in R (version 4.3.2) using the packages tidytext, igraph, and ggraph. All analyses were carried out in R version 4.3.2 [30].

3. Results

3.1. Assessment of Social, Economic, Environmental, and Organisational Challenges in Rural Communities

The results for the social dimension (Figure 1) reveal significant challenges in terms of inclusive participation, gender equity, and social well-being. A total of 93.8% of respondents disagreed or strongly disagreed with the existence of effective participatory mechanisms in decision-making (S1), suggesting that such mechanisms are either absent or ineffective. Similarly, 93.3% indicated that gender equality and equitable participation between men and women were not promoted (S2), evidencing persistent barriers to achieving fair representation. These results are consistent with cultural and social dynamics that often restrict women and young people from assuming leadership roles. As one community leader remarked, “Women are increasingly involved in the management of projects and community activities, which is a positive change in our participation” (Presidenta, Cucho–Huancayo).

Figure 1.

Perceptions of Social Participation and Equity in Rural Communities.

In relation to training and access to services, 82% of respondents reported the absence of training programmes for community organisation (S4), while 74.5% disagreed with the existence of accessible healthcare services (S5). Social cohesion also appears limited: 80.4% did not perceive adequate promotion of community relations and solidarity (S7), while 72.9% disagreed with the promotion of overall well-being (S6). This lack of inclusion particularly affects young members. As noted by a community leader, “We have faced endless difficulties to involve young people in community assemblies, but we are implementing strategies to encourage their active participation, because most of them are professionals with a different vision” (President, San Pedro de Cajas–Tarma).

Furthermore, food security and economic resilience are also constrained: 78.8% disagreed that sufficient access to safe and nutritious food exists (S8), and 72.0% disagreed with the promotion of income diversification (S9). External collaboration and governance were also poorly evaluated, as 84.1% perceived no effective relationships with external actors (S10) and 90.3% disagreed that projects were promoted with active community involvement (S11). Finally, 88.3% indicated that property and land-use rights were not adequately established (S12).

Despite these limitations, some positive practices were highlighted. As expressed in one testimony: “Our community holds regular assemblies where all members can express their opinions and vote on important issues” (Community member). Such mechanisms demonstrate a democratic tradition, but their effectiveness is undermined by weak institutional support, low inclusivity, and structural barriers. Overall, the results underline the fragility of the social dimension, characterised by limited participation, insufficient equity, weak social cohesion, and a lack of effective collaboration, all of which constrain the communities’ ability to achieve sustainable development.

The economic dimension (Figure 2) reveals predominantly negative perceptions regarding income sufficiency, transparency, and the capacity to promote sustainable economic practices. A total of 76.5% of respondents disagreed or strongly disagreed that their community had sufficient income to ensure development (E1), reflecting widespread economic precariousness and limited sustainability. This perception is illustrated by the testimony of a treasurer: “Chongos Alto depends largely on potato farming for subsistence, but we are also affected by the rising costs of seeds and fertilisers. When we raise our prices, there are no buyers, so we are harmed” (Treasurer, Chongos Alto–Huancayo).

Figure 2.

Perceptions of Economic Development and Transparency in Rural Communities.

Financial governance was another area of concern. Approximately 89.7% of respondents disagreed with the existence of transparency and accountability mechanisms in financial management (E2), suggesting structural weaknesses that undermine trust in community leaders and institutions. Similarly, 87.7% rejected the existence of clear financial procedures or regulations (E11), reinforcing the perception of mismanagement and low institutional credibility. Knowledge of sustainable development also appeared limited, with 76.0% expressing disagreement or uncertainty regarding whether community members understood its meaning (E3). Furthermore, 85.3% perceived inequities in the distribution of resources and opportunities (E6), reflecting unequal access to benefits and persistent internal divisions.

Institutional and cooperative development remains weak. A total of 79.6% disagreed with the promotion of cooperatives or communal enterprises (E7). Nevertheless, some communities have begun to explore alternatives. For instance, one farmer explained: “We have a cooperative here in Colpar for guinea pig farming and milk production. Institutions like Continental have supported us with training. With new techniques and processes, we are adapting to change; it is not the same as before” (Community member, Colpar–Huancayo).

Economic diversification and integration into broader markets are also limited. Around 82.5% of respondents did not perceive sufficient diversity in economic activities (E8), and 83.8% disagreed that local products were promoted for export (E9). In this context, testimonies emphasise both challenges and emerging opportunities: “The expansion of our agricultural territory has changed our way of life. We had to adapt traditional practices to compete with large producers and to export our vegetables, but now in groups and under our own brand” (President, Palcamayo–Tarma). Likewise, another community member remarked: “In Ingenio, the community discussed eco-tourism projects, but nothing concrete has materialised. It would be beneficial as a long-term alternative given population growth” (Community member, Ingenio–Huancayo).

While mining activity has generated employment opportunities, it has also produced economic dependency. As one participant highlighted, “Mining has generated jobs, but it has also changed our way of life and made us more dependent on the mining company for income and basic services” (Community member, Manuel Montero–Yauli). Such dependency underscores the fragility of local economies and their vulnerability to external actors.

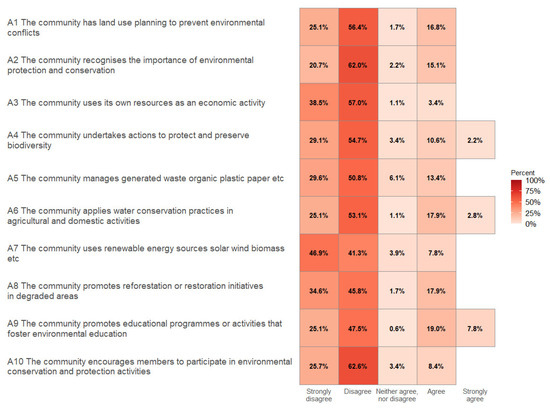

The results reveal a predominantly negative perception of environmental practices and policies, with most respondents disagreeing with the implementation of sustainability measures (Figure 3). A total of 81.5% disagreed or strongly disagreed that land-use planning existed to prevent environmental conflicts (A1), reflecting the absence of effective planning mechanisms to mitigate disputes over natural resources. This finding aligns with testimonies from local leaders who highlight the environmental and social pressures derived from extractive activities: “For our community, mining has influenced us greatly. It has brought employment, but also concerns about environmental pollution, conditioning how we organise ourselves” (President, San Francisco de Asís–Pucará, La Oroya). Similarly, 82.7% of respondents did not believe that their community recognised the importance of environmental protection and conservation (A2), revealing a lack of environmental awareness that could hinder the adoption of sustainable practices. In addition, 95.8% disagreed that natural resources were being used in a sustainable way (A3), pointing to either underutilisation or mismanagement due to insufficient training and incentives.

Figure 3.

Perceptions of Environmental Management in Rural Communities.

Negative perceptions also extended to conservation and biodiversity protection, as 84.6% of respondents reported no effective actions to preserve local biodiversity (A4). Waste management was also perceived as inadequate, with 80.7% disagreeing that the community managed solid waste effectively (A5). Water management appeared especially critical: 94.4% indicated insufficient conservation practices in agricultural and domestic activities (A6). This finding is reinforced by a testimony emphasising water conflicts: “Water disputes between neighbouring communities always require mediation. Without intervention, conflicts prolong, crops are damaged, and livestock lack feed” (President, Usibamba–Chupaca). Furthermore, 88.5% of respondents perceived dependency on traditional energy sources as a limitation to sustainability (A7), while 80.4% reported the absence of reforestation or ecological restoration initiatives in degraded areas (A8). Finally, perceptions of environmental education and participation were particularly negative: 72.5% and 88.3% of respondents, respectively, disagreed that programmes promoting environmental awareness (A9) or community engagement in conservation (A10) were in place.

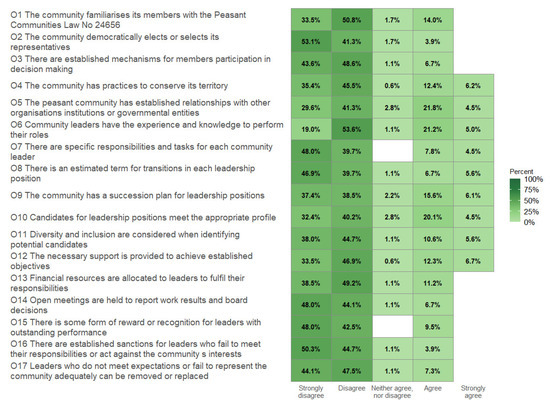

The results presented in Figure 4 reveal significant organisational challenges, with a predominant trend of disagreement across key aspects of governance and internal management. A total of 91.6% of respondents disagreed or strongly disagreed with the possibility of removing or replacing leaders who fail to meet expectations or adequately represent the community (O17), highlighting the absence of effective accountability and transparency mechanisms. Similarly, 95.4% reported that no established sanctions exist for leaders who fail in their duties or act against community interests (O16), reinforcing the perception of impunity and weak control over governance processes.

Figure 4.

Perceptions of Community Organization and Governance in Rural Communities.

In terms of incentives, 92.8% disagreed that any system of recognition for outstanding leaders was in place (O15), which may reduce motivation to improve leadership performance and foster community development. Likewise, 90.5% indicated that open meetings to report board decisions and activities were not held (O14), reflecting deficiencies in communication and transparency that limit trust and participation in decision-making.

Concerns were also evident regarding leadership resources and support. A total of 88.6% disagreed that adequate financial resources were allocated to fulfil leaders’ responsibilities (O13), while 80.4% believed that necessary support for achieving community objectives was lacking (O12). In addition, 83.1% perceived insufficient diversity and inclusion in the selection of leadership candidates (O11), raising questions about equitable representation.

Regarding organisational practices, 88.6% of respondents disagreed that a succession plan existed (O9), and 85.8% disagreed with the existence of planned transitions in leadership (O8). Furthermore, 87.5% indicated that leaders had no clearly defined responsibilities (O7), and 85.1% perceived a lack of experience and knowledge among current leaders (O6). This perception was echoed by community members, such as one participant who noted: “To elect the president, he must have experience and knowledge, above all our land. The assembly first considers who the person is, whether they are known, and whether they show commitment and experience” (Community member, Racracalla–Concepción).

Similarly, 87.6% disagreed that their communities maintained relationships with other organisations, institutions, or government bodies (O5), limiting opportunities for collaboration and external support. Finally, 85.0% disagreed with practices to strengthen local governance, such as disseminating the Smallholder Communities Law No. 24656 (O1), although a majority (94%) expressed support for the principle of democratic elections (O2). This apparent contradiction is also reflected in testimonies: “Our president is elected democratically; we all vote. However, external institutions such as the municipality, companies, and committees sometimes interfere with decisions to represent us effectively, and personal interests become evident” (Community member, Aco–Concepción).

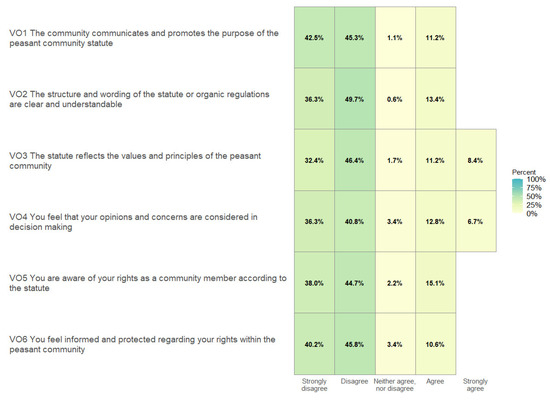

The results in Figure 5 reveal predominantly negative perceptions regarding the normative and rights-based dimension of community life. A total of 87.8% of respondents disagreed or strongly disagreed that the community adequately communicates and promotes the purpose of the communal statute (VO1), suggesting a lack of effective dissemination of its content and relevance. This gap may contribute to misinformation and confusion about rights and obligations among members. Similarly, 84.2% reported that the structure and wording of the statute were neither clear nor understandable (VO2), reflecting its inaccessibility to large segments of the population. Concerns also extend to the cultural dimension of the statute: 78.9% of respondents felt that it did not reflect the values and principles of the smallholder community (VO3), indicating a disconnection between formal regulations and cultural expectations. Furthermore, 77.1% of participants disagreed that their opinions and concerns were considered in decision-making processes (VO4), which reinforces perceptions of exclusion and weakens social cohesion and trust in organisational structures. The lack of rights awareness is particularly evident. A total of 82.7% of respondents declared being unaware of their rights as community members under the statute (VO5), while 86.0% did not feel informed or protected regarding their rights (VO6). These findings underscore deficiencies in the dissemination and enforcement of rights, leading to a sense of insecurity and vulnerability among community members. This discontent was also reflected in the testimonies. As one community leader expressed, “The State does not support our communities to stand out; we remain the same, forgotten. We need more support and recognition to strengthen our autonomy, but it has not existed so far.” (Presidenta, Cucho–Chongos Alto, Huancayo).

Figure 5.

Perceptions of Values & Rights Awareness in Rural Communities.

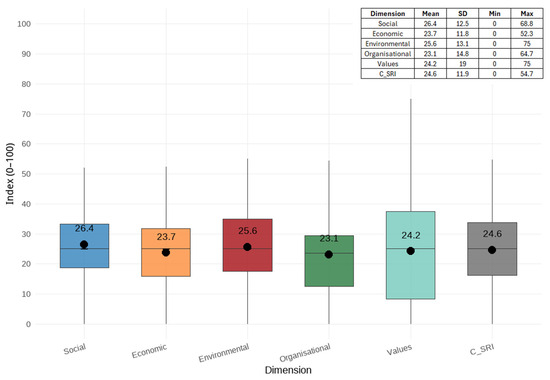

The comparative distribution of indices across dimensions (Figure 6) highlights a consistent pattern of low averages, with no domain surpassing 27 points on a 0–100 scale, underscoring the systemic and interdependent nature of the challenges faced by rural communities in Junín. While minor variations can be observed, the social dimension slightly outperforming others and the economic and organisational dimensions exhibiting the lowest means the overall homogeneity of low scores suggests that weaknesses in governance, economic diversification, environmental stewardship, and normative frameworks are mutually reinforcing rather than isolated. This concentration of low performance across dimensions not only reflects structural deficiencies already noted in the literature, such as limited infrastructure, fragile governance, and dependence on traditional livelihoods, but also exposes gaps in institutional support and external collaboration that prevent communities from leveraging their cultural and social capital into more resilient and sustainable practices.

Figure 6.

Distribution of community sustainability indices by dimension and overall index (C-SRI).

The correlation analysis between the five sustainability dimensions and the global Community Sustainability and Resilience Index (C-SRI) revealed a consistent pattern of positive interdependence. All correlations were statistically significant (p < 0.001), indicating a strong internal coherence among dimensions. The Values and C-SRI indices exhibited the highest correlation (ρ = 0.903), followed by the Organisational–C-SRI (ρ = 0.858) and Environmental–C-SRI (ρ = 0.820) pairs, highlighting the central role of ethical–cultural values, governance, and environmental management in determining overall sustainability performance.

The Economic dimension showed strong positive correlations with both Social (ρ = 0.702) and Environmental (ρ = 0.638) dimensions, underscoring the interdependence between economic viability, social equity, and ecological resilience. Likewise, significant associations between the Organisational and Values dimensions (ρ = 0.741) suggest that participatory governance and shared normative frameworks reinforce community resilience.

Overall, these findings demonstrate that sustainable community performance in Junín emerges from the mutual reinforcement of social, economic, organisational, and cultural factors, rather than from isolated sectoral strengths (Table 1).

Table 1.

Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients (ρ) among sustainability dimensions and the global Community Sustainability and Resilience Index (C-SRI).

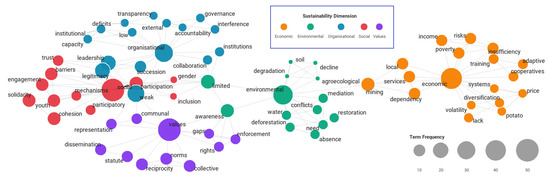

Based on the analysis of 60 semi-structured interviews with community leaders or representatives, a qualitative thematic synthesis was conducted to identify the most recurrent concepts associated with community sustainability. The resulting thematic co-occurrence network is presented in Figure 7, where node size represents the frequency of occurrence of each term and node colour corresponds to the predominant sustainability dimension (Social, Economic, Environmental, Organisational, or Values).

Figure 7.

Thematic co-occurrence network derived from 60 semi-structured interviews with rural community representatives.

The network reveals the coexistence of five main clusters reflecting the structural dimensions of sustainability in rural contexts. The economic cluster (orange) emphasises issues such as dependency, price volatility, and diversification, highlighting economic fragility and limited resilience to market fluctuations. The organisational cluster (blue) concentrates on transparency, accountability, and leadership legitimacy, evidencing institutional weaknesses and governance deficits. The environmental cluster (green) connects terms such as awareness, water conflicts, degradation, and restoration, reflecting environmental stress derived from extractive activities and insufficient ecological management. The social cluster (red) integrates themes such as participation, inclusion, youth engagement, and cohesion, pointing to persistent barriers to collective action and inclusive governance. Lastly, the values cluster (purple) encompasses concepts such as rights, reciprocity, collective, and norms, which represent the ethical and cultural foundations that sustain social and organisational practices.

Overall, the configuration of the network demonstrates that values and social participation act as linking dimensions, connecting the economic, environmental, and organisational domains. This qualitative evidence underscores the centrality of governance, ethical norms, and collective organisation as essential conditions for strengthening resilience and sustainable development in rural communities.

3.2. Proposal for a Governance-Centred Management Model for Sustainable Development in Rural Andean Communities

The proposed management model is conceived as a governance-centred and context-responsive framework that translates the empirical diagnosis into actionable strategies for the rural communities of Junín. Instead of adopting generic sustainability prescriptions, the model directly targets the structural limitations identified in the results—namely the lack of transparency, accountability, economic diversification, environmental stewardship, and organisational legitimacy.

The model operates under the principle of economía mixta comunal, where agro-pastoral livelihoods, ecosystem stewardship, and community-based economic diversification co-evolve with transparent and participatory decision-making. By recognising the cultural foundations of Andean communities—including reciprocity (ayni), communal work (faena), and territorial identity (llaqta)—the model aims to strengthen local governance as the enabling condition for sustainable territorial development.

Table 2 details the resulting set of strategies derived from both the quantitative patterns and the qualitative thematic analysis. Each strategy responds to a specific diagnosed problem and proposes a practical, locally viable mechanism for change, moving beyond broad SDG statements. These strategies prioritise community autonomy, value aggregation, ecological restoration, and inter-communal cooperation, while acknowledging the realities of potato-based agriculture, mining pressure, and recurrent water conflicts in the region.

Table 2.

Targeted strategies for sustainable development in rural Andean communities of Junín.

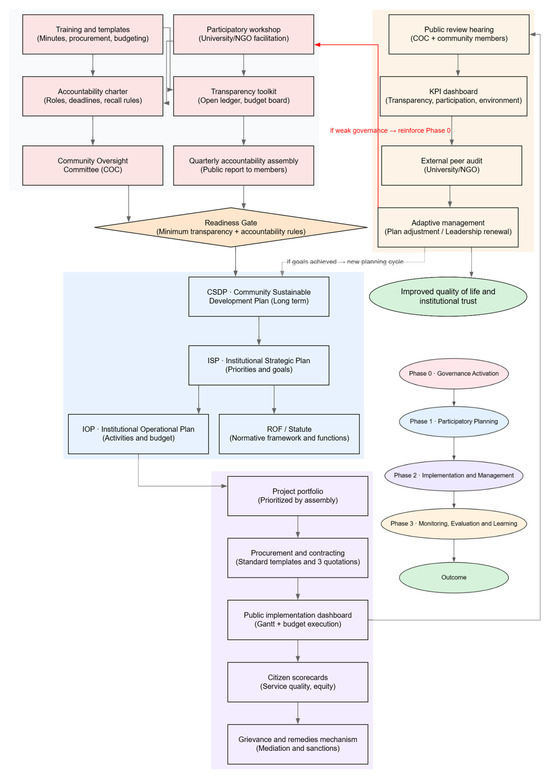

The empirical diagnosis demonstrated that the core limitation to sustainability in rural communities of Junín does not stem from the absence of planning instruments, but from systemic governance failures. Quantitative evidence revealed extremely low levels of transparency (89.7% disagreement), accountability (91.6% disagreement), inclusive participation (93.8% disagreement), gender equity (93.3% disagreement), and institutional communication (90.5% disagreement). These weaknesses are further reinforced by the strong correlations observed between organisational, values-based and global C-SRI indices (ρ = 0.858 and ρ = 0.903), confirming that governance and normative frameworks are structural determinants of community sustainability. Qualitative analysis supports this diagnosis: the thematic co-occurrence network shows that “participation”, “rights”, “transparency” and “accountability” act as bridging concepts linking environmental, economic and organisational challenges, while interview testimony reveals mistrust, institutional fragility and weak citizen oversight. In response to these findings—and to avoid reproducing top-down planning approaches—the proposed model adopts a governance-first structure, recognising that long-, medium- and short-term planning instruments (CSDP, ISP, IOP and Statute/ROF) can only succeed if minimum conditions of institutional credibility and collective action are secured beforehand. The model therefore incorporates a preliminary enabling phase that activates procedural transparency, community oversight, and participatory decision-making before formal planning begins.

The model is organised into four sequential phases and one enabling stage, integrating organisational strengthening with participatory local development. Phase 0: Governance Activation. This enabling stage addresses the root governance problems identified in the diagnosis by establishing minimum conditions of trust, transparency and accountability. Its core mechanisms include a participatory governance workshop facilitated by external actors (universities or NGOs), a transparency toolkit (open ledger and public budget board), an accountability charter with explicit recall rules for leaders, the creation of a Community Oversight Committee, and quarterly public accountability assemblies.

Completion of this stage functions as a readiness gate, ensuring that basic transparency standards, participatory norms and institutional legitimacy are in place before moving to formal planning. Phase 1: Participatory Planning. Once governance preconditions are secured, formal planning instruments are developed through inclusive assemblies, enabling collective definition of priorities, strategies and resource allocation. Phase 2: Implementation and Management. Community decisions are translated into action through a project portfolio prioritised by the assembly, supported by standardised procurement procedures (three-quotation rule), a public implementation dashboard (Gantt plus budget execution), and citizen scorecards to monitor service quality, equity and performance. Phase 3: Monitoring, Evaluation and Learning. Oversight is conducted through public review hearings, KPI dashboards (transparency, participation, environment), external peer audits, and an adaptive management mechanism that allows for plan adjustments or leadership renewal when necessary. If governance deteriorates, the model explicitly returns to Phase 0, reinforcing accountability measures until readiness is restored. Outcome. The expected result is improved quality of life, institutional trust and sustainable territorial governance, supported by a continuous learning cycle that integrates quantitative monitoring with participatory deliberation (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Management Scheme for Sustainable Development in Peruvian Rural Communities.

Community planning is developed through a coordinated process, from a long-term sustainable development plan, through a medium-term institutional strategic plan, to a short-term operational plan, adapting to local conditions and emerging needs. Community organisation includes the creation and implementation of regulatory management instruments, such as internal regulations and administrative procedure manuals, together with financial management tools that promote transparency and accountability in resource use. Community leadership focuses on the effective execution of planned strategies, facilitating integration and communication among community actors, thereby encouraging participation in decision-making aligned with sustainable development objectives. Community control involves evaluation and monitoring activities to measure the impact of actions and ensure alignment with strategic objectives, promoting continuous improvement and the adaptation of strategies based on results. This interconnected management framework contributes to improving the quality of life of community members and ensuring a sustainable future for rural communities.

The implementation of the sustainable development model for rural communities depends on the collaboration of strategic actors with varying levels of involvement and power hierarchy. Among them, the institution responsible for the agricultural sector (Ministry of Agriculture) and the property formalisation agency (COFOPRI) stand out for their high level of involvement and power, playing fundamental roles in promoting sustainable agricultural practices and in the regularisation of land tenure. The regional or local government (Regional Government of Junín) and its regional agricultural development office (Regional Directorate of Agriculture of Junín) also play a key role in ensuring the effective coordination of initiatives at the regional level (Table 3).

Table 3.

Strategic Actors for the Implementation of the Sustainable Development Model.

In addition, the land titling and property office (Directorate of Land Titling—DRAJ) facilitates the management and formalisation of land use, an essential component for economic and social sustainability. Entities such as the environmental protection agency (Ministry of the Environment) and the water resources authority (ANA) play a crucial role in the management and conservation of natural resources. The economic and financial planning agency (Ministry of Economy and Finance) and the judicial system (Judiciary) provide administrative and legal support. Finally, the Rural Communities Information System (SICCAM), together with local universities and faculties, strengthen research, data collection, and capacity building, promoting an integrated and participatory approach to model implementation.

The implementation of the sustainable development model for rural communities is based on an organisational structure aligned with community statutes and the Peruvian Law on Rural Communities (Law No. 24656). This legislation guarantees the autonomy of communities in managing their internal affairs, requiring that the model’s strategies and actions respect the collective will of the community. The creation and modification of these documents are carried out democratically through community assemblies that legitimise decisions and ensure member participation. This process provides a strong legal and community foundation, preventing legal disputes by aligning actions with the internal provisions of each rural community.

The planning phase introduces key tools such as the Community Development Plan (PDC), the Institutional Strategic Plan (PEI), and the Institutional Operational Plan (POI), which serve as strategic guides. The PDC, with a long-term vision, establishes goals and priorities aligned with the National Centre for Strategic Planning (CEPLAN) and the SDGs. The PEI provides a clear direction, while the POI details specific actions and deadlines, ensuring participatory and coherent implementation. Together, these plans establish a solid foundation for effective and sustainable management.

The organisation phase strengthens the internal structure through the implementation of regulatory instruments such as the Community Organisation and Functions Regulation (ROF-CL) and a Conflict Management Manual, which define functions and responsibilities. These documents promote governance and external coordination, creating a collaborative environment that fosters internal resilience. The conflict management manual is key to addressing disputes constructively, aligning with the principles of peace, justice, and strong institutions of the 2030 Agenda. In the leadership phase, a Standardised Administrative Procedures Manual is implemented, aligning actions with internal regulations and CEPLAN guidelines. This approach ensures the harmonisation of local and national efforts, improving administrative efficiency and community participation in development. The control phase incorporates Community Financial Management, ensuring efficient administration, transparency, and accountability in the use of funds. This approach reinforces coherence with national guidelines, promoting equitable and sustainable growth for rural communities in the Junín Region.

4. Discussion

The lack of inclusive participation and equity in smallholder communities is a multidimensional issue rooted in social, economic, and cultural dynamics. One of the principal barriers is the historical marginalisation of women and landless farmers, which limits their capacity to influence decision-making and constrains democratic community governance. As documented in other Latin American contexts, gendered power structures reproduce exclusion through norms that prioritise male authority, thereby restricting women’s participation and leadership [31,32]. These structural asymmetries explain why participatory mechanisms fail to materialise in practice, despite being formally recognised, a pattern also reflected in the Andean experience [33].

Weak participation not only reduces empowerment but also diminishes collective action, which is essential for managing common resources and resolving territorial conflicts. When community members perceive that their participation has no influence, social cohesion erodes and incentives to cooperate are weakened, thereby limiting the effectiveness of bottom-up development strategies [15]. Economic vulnerability further amplifies these governance limitations. Overdependence on traditional agriculture reduces adaptive capacity because households lack buffers against market volatility and climate shocks [34,35]. While diversification can stabilise livelihoods and enhance food security, its success depends on enabling conditions—such as infrastructure, connectivity, and market integration—which remain largely absent. Without these conditions, diversification becomes symbolic rather than transformative, as seen in multiple rural cases across Latin America [36,37].

Environmental management weaknesses share the same institutional roots. The absence of land-use planning and ecological governance contributes to soil degradation, biodiversity loss, and persistent water conflicts. These problems are not merely technical, but institutional: when communities lack environmental awareness and regulatory capacity, territorial disputes intensify and conservation efforts collapse [38,39]. Infrastructure and technological deficits accentuate this cycle by limiting access to sustainable practices and environmental monitoring systems, reinforcing the need for integrated territorial planning [40].

Transparency emerges as the critical missing link that connects these failures. Opaque financial management undermines trust, reduces accountability, and weakens incentives for collective oversight—conditions that, according to international evidence, directly reduce community willingness to engage in long-term sustainability initiatives [41,42]. This demonstrates that the core issue is not sectoral weakness, but systemic governance fragility, where institutional opacity perpetuates social exclusion and environmental degradation. Strengthening transparency and accountability therefore becomes a causal precondition for sustainability. ICT-based tools can reduce information asymmetries, enhance monitoring, and enable community oversight, promoting a participatory culture grounded in shared responsibility [43]. Values, norms, and reciprocity operate as bridging dimensions that align governance, environmental stewardship, and economic resilience, confirming that sustainable development depends on ethical cohesion as much as on technical capacity.

These findings are consistent with Ostrom’s governance principles, which emphasise collective action, cooperation, and community-led stewardship of common resources. Ostrom’s framework has been successfully applied to global challenges such as overfishing, where local participation and cooperation between actors and regulators are essential for sustainable management [44]. In the context of climate change, polycentric governance fosters experimentation, learning, and coordination across multiple scales, reinforcing Ostrom’s emphasis on reciprocity and collective responsibility [45]. These principles support the idea that sustainable governance emerges when local institutions are empowered to self-organise, monitor resource use, and enforce rules through legitimate and transparent mechanisms.

In response to these structural findings, the proposed governance-centred model links institutional reforms (transparency, accountability, and participatory planning) to economic diversification and environmental stewardship. Unlike generic SDG-based approaches, it treats governance not as an accessory, but as an enabling condition, ensuring that sectoral strategies are viable in real community settings [46,47]. The inclusion of ICTs and community monitoring strengthens accountability while aligning Andean reciprocity with contemporary digital governance practices, a dual approach rarely operationalised in previous models [48,49]. The strong correlations between organisational, values-based, and C-SRI indices reinforce this causality, empirically validating a governance-first pathway.

Implementing this model requires a multisectoral, adaptive strategy that integrates agriculture, health, and education, while remaining flexible to the heterogeneity of Andean territories [50,51]. By fostering strategic collaboration among government institutions, NGOs, and community organisations, the model provides a realistic foundation for long-term territorial sustainability. To ensure practical applicability, strategies for governance and sustainability must be tailored to Peru’s policy environment and institutional constraints. In this context, actionable measures should prioritise the coordinated use of existing national mechanisms over broad, generic recommendations. River basin councils led by the National Water Authority (ANA), participatory budgeting processes managed by local governments and CEPLAN’s planning frameworks could offer concrete instruments for cross-sectoral coordination. Similarly, low-cost ICT solutions can be integrated into existing public programmes, such as PRONATEL for connectivity and the MEF transparency platforms, to enhance community oversight and improve access to information in rural areas.

5. Conclusions

This study reveals that rural smallholder communities in Peru face intertwined social, economic, and environmental challenges, such as inadequate infrastructure, weak governance, and limited economic diversification. To address these issues, a comprehensive management model tailored to the local realities of Junín is proposed, integrating transparency and accountability, inclusive participation, and sustainable economic practices. This collaborative framework engages community leaders, local governments, external organizations, and residents, fostering social cohesion, equitable benefit distribution, and the sustainable use of natural resources. The strategic incorporation of information and communication technologies (ICTs) can further enhance governance transparency, strengthen evidence-based decision-making, and stimulate active community engagement. The model’s adaptability ensures relevance to the unique contexts of each community, making development strategies more effective and sustainable.

By combining participatory governance, economic diversification, and environmental stewardship, this approach not only meets immediate community needs but also builds long-term resilience and inclusivity. Importantly, the model generates concrete policy implications by emphasising participatory planning, transparent resource allocation, and community-led monitoring, which are critical for strengthening local governance and reducing rural inequalities. It offers a viable pathway for rural development aligned with the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development Goals, contributing to poverty reduction, social equity, and environmental protection. Future research should deepen the systematic analysis of ICTs as drivers of participatory governance, economic diversification, and adaptive capacity in Andean smallholder communities, while also assessing their potential to bridge rural–urban gaps and enhance policy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.S.-L. and G.P.-C.; methodology, F.S.-L. and D.V.-Q.; software, D.V.-Q.; validation, D.V.-Q. and R.S.-d.M.; formal analysis, G.P.-C. and D.V.-Q.; investigation, F.S.-L.; resources, G.P.-C.; data curation, D.V.-Q.; writing—original draft preparation, F.S.-L.; writing—review and editing, R.S.-d.M.; visualization, G.P.-C.; supervision, F.S.-L. and R.S.-d.M.; project administration, G.P.-C.; funding acquisition, G.P.-C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Universidad Nacional del Centro del Perú through the complementary call for the contest “Proyectos de investigación para elevar el número de publicaciones en revistas científicas indizadas” UNCP-2023, according to Resolution No. 1917-R-2023.

Institutional Review Board Statement

IRB approval obtained (approved by the Ethics Committee of Research Ethics Committee of the Department of Sociology, Central National University of Peru (Constancia CEI_FAC SOC UNCP FHM N°001) on 20 May 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset supporting the reported results is openly available online in figshare at: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29923343.v1, under the title Management Model and Strategies for Sustainable Development in Peruvian Smallholder Communities.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Universidad Nacional del Centro del Perú for its institutional and logistical support in carrying out this study. We also extend our gratitude to the smallholder communities visited for their hospitality, collaboration, and willingness to share their knowledge and experiences.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| UNCP | Universidad Nacional del Centro del Perú |

| PRA | Participatory Rural Appraisal |

| ICTs | Information and Communication Technologies |

| COFOPRI | Organismo de Formalización de la Propiedad Informal |

| ANA | Autoridad Nacional del Agua |

| SICCAM | Sistema de Información sobre Comunidades Campesinas del Perú |

| PDC | Plan de Desarrollo Comunal |

| PEI | Plan Estratégico Institucional |

| POI | Plan Operativo Institucional |

| ROF-CL | Reglamento de Organización y Funciones de la Comunidad Local |

| CEPLAN | Centro Nacional de Planeamiento Estratégico |

References

- Guo, Q.; He, Z.; Li, D.; Spyra, M. Analysis of Spatial Patterns and Socioeconomic Activities of Urbanized Rural Areas in Fujian Province, China. Land 2022, 11, 969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M.; Ouyang, B.; Quayson, M. Navigating the Nexus Between Rural Revitalization and Sustainable Development: A Bibliometric Analyses of Current Status, Progress, and Prospects. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Chai, Q.; Liu, X.; He, B.-J. Sustainability Assessment of Rural Toilet Technology Based on the Unascertained Measure Theory. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1112689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, A.V.M.; Oliveira, P.A.D.; Matos, P.G. Review of Community-Managed Water Supply—Factors Affecting Its Long-Term Sustainability. Water 2022, 14, 2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaranta, G.; Citro, E.; Salvia, R. Economic and Social Sustainable Synergies to Promote Innovations in Rural Tourism and Local Development. Sustainability 2016, 8, 668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulygina, T.; Tufanov, E.; Yanush, S.V.; Kravchenko, I.; Ivashova, V. Modeling the Regional Agro-Elite’s Social Position in Rural Areas’ Sustainable Development System. E3s Web Conf. 2021, 258, 5029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voronkova, O.; Iakimova, L.; Frolova, I.I.; Shafranskaya, C.I.; Kamolov, S.; Prodanova, N.A. Sustainable Development of Territories Based on the Integrated Use of Industry, Resource and Environmental Potential. Int. J. Econ. Bus. Adm. 2019, VII, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belikova, I.; Kurennaya, V.; Ivashova, V.; Chernobay, N.; Narozhnaya, G.; Kapustina, E. Rural Areas’ Factors of Sustainable Socio- Economic Development: Estimates of Agricultural Producers. E3s Web Conf. 2023, 462, 01019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanelli, M. Towards Sustainable Rural Communities. Eur. Conf. Knowl. Manag. 2023, 24, 1123–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Zhu, H.; Hu, S. Human-Environment Sustainable Development of Rural Areas in China. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2017, 64, 012054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamov, T.; Ciolac, R.; Iancu, T.; Brad, I.; Peț, E.; Popescu, G.; Șmuleac, L. Sustainability of Agritourism Activity. Initiatives and Challenges in Romanian Mountain Rural Regions. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orellana, A.F.A.; Vaez, M.A.F. Las comunidades campesinas y el desarrollo sostenible empresarial. Ius Inkarri 2017, 6, 451–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez Aliaga, R.; De los Ríos-Carmenado, I.; San Martín Howard, F.; Calle Espinoza, S.; Huamán Cristóbal, A. Integration of the Principles of Responsible Investment in Agriculture and Food Systems CFS-RAI from the Local Action Groups: Towards a Model of Sustainable Rural Development in Jauja, Peru. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabogal-Dunin-Borkowski, A. Desarrollo sostenible del páramo peruano: Estudio de caso de los páramos de Pacaipampa, Frías y Huancabamba, departamento de Piura, Perú. Rev. Kawsaypacha Soc. Medio Ambiente 2023, 12, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia-Sandoval, C.; Flanders, D.; Kozak, R. Participatory Landscape Planning and Sustainable Community Development: Methodological Observations From a Case Study in Rural Mexico. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2010, 94, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castañeda, S.A.; Pomiano, E.F.N.; Guzmán, M.L.B. Identidad comunitaria y desarrollo sostenible: Estudio etnográfico de una comunidad rural evangélica en Perú. Cult. Relig. 2024, 18, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stadel, C. Resiliencia y adaptación de las comunidades rurales y de los usos agrarios en los Andes tropicales: Conexión con los cambios ambientales y socioeconómicos. Pirineos 2008, 163, 15–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeballos-Velarde, C.; Butron-Revilla, C.; Manchego-Huaquipaco, G.; Yory, C. The Role of Ancestral Practices as Social Capital to Enhance Community Disaster Resilience. The Case of the Colca Valley, Peru. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2023, 92, 103737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayre, M.; Stenner, T.; Argumedo, A. You Can’t Grow Potatoes in the Sky: Building Resilience in the Face of Climate Change in the Potato Park of Cuzco, Peru. Cult. Agric. Food Environ. 2017, 39, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, M. Modelo de cuidado para el desarrollo sostenible en comunidades rurales del Perú. Rev. ECIPerú 2018, 10, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sietz, D.; Feola, G. Resilience in the Rural Andes: Critical Dynamics, Constraints and Emerging Opportunities. Reg. Environ. Change 2016, 16, 2163–2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, I. Propriété collective, gestion des communs et structuration sociale. Rev. Int. Études Dév. 2018, 234, 31–53. [Google Scholar]

- Arias, J.A.A.; Trigoso, F.B.M. Soberanía Alimentaria y Tecnologías Sociales: Una Experiencia de Desarrollo Autónomo Desde Los Andes Del Perú. Cienc. Ergo-Sum Rev. Cient. Multidiscip. Prospect. 2019, 26, 31–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McSweeney, C.; Remy, M. Building Roads to Democracy? The Contribution of the Peru Rural Roads Program to Participation and Civic Engagement in Rural Peru; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgos, D. La circulation d’un modèle de démocratie locale en Amérique latine: L’exemple du budget participatif. Am. Cah. CRICCAL 2005, 33, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergara-Camus, L. Rural Social Movements in Latin America: In the Eye of the Storm. J. Agrar. Change 2013, 13, 590–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, E.; Ferrer, J. Management Community of Communal Lands in the Andean Rural Community of San Roque de Huarmitá, Concepción, Junín, Peru. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 943, 012021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SICCAM. Directorio 2016 Comunidades Campesinas del Perú; Instituto del Bien Común (IBC): Lima, Peru, 2016; ISBN 978-612-47041-5-4. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática (INEI). Compendio Estadístico, Junín 2024. Available online: https://www.gob.pe/institucion/inei/informes-publicaciones/6497768-compendio-estadistico-junin-2024 (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Core Team: Vienna, Austria, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Castro Zamora, I.N.; Pachón Ariza, A.F. Social and Solidarity Economy, Women and Empowerment: The Case of Inzá Tierradentro Peasant Association. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Advanced Research in Social Sciences; Acavent, Paris, France, 22 November 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gusti, R.; Putra, A.; Dlofiroh, J.M. Women’s Empowerment for Peasant Women’s Groups. Int. J. Res. Rev. 2022, 9, 529–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumasari, D.; Dharmawan, B.; Santosa, I.; Darmawan, W.; Aisyah, D.D.; Budiningsih, S. Function of Social Cohesion Element in Participatory Empowerment towards Landless Peasants. SHS Web Conf. 2020, 86, 01038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, N.; Ariyawardana, A.; Aziz, A.A. The Influence and Impact of Livelihood Capitals on Livelihood Diversification Strategies in Developing Countries: A Systematic Literature Review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 69882–69898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saliman, L.; Swee-Kiong, W. Enhancing Rural Wellbeing: Unravelling the Impact of Economic Diversification in Sarawak. J. Prod. Oper. Manag. Econ. 2023, 3, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assan, J. Livelihood Diversification and Sustainability of Rural Non-Farm Enterprises in Ghana. J. Manag. Sustain. 2014, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asfaw, A.; Simane, B.; Hassen, A.; Bantider, A. Determinants of Non-Farm Livelihood Diversification: Evidence from Rainfed-Dependent Smallholder Farmers in Northcentral Ethiopia (Woleka Sub-Basin). Dev. Stud. Res. 2017, 4, 22–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, C.; Cai, M.; Guy, C. Rural Sustainable Environmental Management. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matunhu, J.; Mago, S.; Matunhu, V. Initiatives to Boost Resilience towards El Niño in Zimbabwe’s Rural Communities. Jàmbá J. Disaster Risk Stud. 2022, 14, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maloney, J.; Markey, S.; Gibson, R.; Weeden, S.A. Advancing Green Infrastructure Solutions in Rural Regions: Economic Impacts and Capacity Challenges in Southwest Ontario, Canada. Rural. Reg. Dev. 2024, 2, 10010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaren, J.; Appleyard, T. Improving Accountability for Farm Animal Welfare: The Performative Role of a Benchmark Device. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2019, 33, 32–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puramongkon, P.; Puramongkon, T. Problems and Needs of Local Leaders towards Sustainable Agriculture in Organic Laying Hens Learning. J. Educ. Issues 2022, 8, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mapiye, O.; Makombe, G.; Molotsi, A.; Dzama, K.; Mapiye, C. Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs): The Potential for Enhancing the Dissemination of Agricultural Information and Services to Smallholder Farmers in Sub-Saharan Africa. Inf. Dev. 2023, 39, 638–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murtazashvili, I. Elinor Ostrom on the High Seas; Mercatus Center: Arlington, VA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Contipelli, E. Da governança dos comuns ao policentrismo: Consideracoes sobre elinor ostrom e mudança climática. Rev. Juríd. (FURB) 2020, 24, e8142. [Google Scholar]

- Kurniawan, D.A.; Witono, B. Village Government Accountability and Transparency in Village Financial Management. JASa J. Akunt. Audit Sist. Inf. Akunt. 2023, 7, 331–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halabi, A.K.; Carroll, B. Increasing the Usefulness of Farm Financial Information and Management: A Qualitative Study from the Accountant’s Perspective. Qual. Res. Organ. Manag. Int. J. 2015, 10, 227–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahayu, S.; Yudi, Y.; Rahayu, R. School Financial Governance Practice. In Proceedings of the First Lekantara Annual Conference on Public Administration, Literature, Social Sciences, Humanities, and Education, LePALISSHE, Malag, Indonesia, 3 August 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Rizal, Y.; Siskawati, E. The Role of Social Media in Improving the Transparency of Village Fund Management. Entrep. Small Bus. Res. 2022, 1, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Didi, L. Ecological Conservation through COREMAP Program Governance Perspectives in Empowering Coastal Communities in Bahari Village. Int. J. Public Leadersh. 2021, 17, 160–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moallemi, E.A.; Malekpour, S.; Hadjikakou, M.; Raven, R.; Szetey, K.; Ningrum, D.; Dhiaulhaq, A.; Bryan, B.A. Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals Requires Transdisciplinary Innovation at the Local Scale. One Earth 2020, 3, 300–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).