1. Introduction

As globalization accelerates, environmental crises such as climate change, resource depletion, and biodiversity loss are becoming increasingly severe, posing urgent global challenges that demand immediate solutions (Heinzel, S. & Bechtoldt, M., 2023) [

1]. Recognizing these pressing issues, the United Nations introduced the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in 2015, a framework that outlines 17 global targets to be achieved by 2030. These goals emphasize a balanced approach to economic, social, and environmental development, calling for coordinated global action across multiple sectors (Serafini, P.G., de Moura, J.M., de Almeida, M.R. & de Rezende, J.F.D., 2022) [

2]. Achieving these goals requires the active engagement of individuals in pro-environmental behavior, as individual actions play a critical role in mitigating the negative impacts of human activity on the planet (Shafiei, A. & Maleksaeidi, H., 2020) [

3]. However, while regulatory policies and external pressures are necessary to guide behavior, they alone are insufficient for ensuring sustained pro-environmental actions. Effective solutions require fostering intrinsic motivation and environmental awareness, which are fundamental to embedding sustainable practices in daily life (Zhang, Y., Du, J. & Boamah, K.B., 2023) [

4].

Education has thus emerged as a critical tool for enhancing the public awareness of sustainability and for instilling the values and knowledge necessary for pro-environmental behavior (Chwialkowska, A., Bhatti, W. A. & Glowik, M., 2020) [

5]. As a special group with a high level of education and innovation ability, college students are not only the decision-makers and executors of future society, but also the active participants of the current campus and social environmental protection activities. Although many colleges and universities have tried to improve students’ environmental literacy by offering general education courses, organizing environmental club activities, and promoting green campus construction, the actual effect of these measures and their mechanism have not been fully verified. Prior research highlights several factors—such as social norms, personal responsibility, and economic incentives—as significant influences on pro-environmental behavior (Ertz, M., Karakas, F. & Sarigöllü, E., 2016; Zhang, L. et al., 2019) [

6,

7]. Yet, how educational interventions interact with these factors to foster the environmental responsibility is less well-understood. Addressing this gap, the present study proposes a comprehensive model examining the roles of sustainable awareness education, subjective norms, psychological contracts, and external support as they collectively shape individual pro-environmental behavior.

This study introduces several innovative perspectives to the discussion of environmental behavior. As an important field for youth socialization, university campuses are not only a place for knowledge transfer, but also a key space for shaping individual environmental values and behavioral habits. The uniqueness of campus life lies in its highly intensive social network, institutionalized educational practice, and relatively controllable environmental scenarios, which provide an ideal observation field for the study of pro-environmental behavior. First, sustainable awareness education is considered an essential pathway for enhancing environmental responsibility. While existing research often emphasizes the short-term impacts of educational interventions, this study hypothesizes that sustainable awareness education has a lasting effect on environmental intentions by fostering a deeper understanding of and commitment to sustainability. Second, the concept of psychological contracts, originating in organizational behavior research, is adapted here as a framework for understanding perceived responsibilities and obligations between individuals and society (Chang, C. et al., 2019) [

8]. This study extends the framework of traditional Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) by introducing Psychological Contract as a mediating variable. Building upon this strong theoretical foundation and its proven explanatory power, the TPB has also been effectively extended to the fields of education and sustainability to investigate pro-environmental behaviors. In this study, researchers utilized the TPB to understand the students’ and educators’ intentions to engage in sustainable practices. The University conveys the concept of environmental protection through the construction of sustainable campuses, and incorporates environmental responsibility into the identity of students. When students see “environmental practitioners” as part of their self-concept, they develop a values-based psychological contract. Third, subjective norms, reflecting social expectations, are considered a powerful social influence that shapes individuals’ environmental intentions and motivates behavior in alignment with societal expectations.

Finally, this study proposes that external support functions as a moderating factor, amplifying the positive effects of education and psychological contracts on pro-environmental behavior. External support—such as incentives, resources, or policy measures—provides individuals with the practical means and reinforcement needed to translate intentions into sustained actions (Jackson, J., Pinckney, J. & Rivers, M., 2022) [

9]. The interaction between external support and psychological mechanisms is of particular interest, as it may reveal pathways through which external incentives enhance intrinsic motivation, thereby creating conditions for enduring behavioral change.

With the intensification of environmental issues, promoting environmentally friendly behavior among college students is crucial for achieving sustainable development goals. By empirically testing these theoretical assumptions, this study aimed to construct an integrated model that provides a more nuanced understanding of the psychological and social mechanisms underlying pro-environmental behavior. Therefore, unlike the traditional TPB framework, we transform sustainable education into internalized moral obligations through psychological contracts. This indicates that pro-environmental behavior is not only derived from rational calculation, but also from identity driven commitment. The findings not only contribute to academic discourse by clarifying how education, social expectations, and external incentives interact, but also offer practical implications for educators and policymakers. Specifically, the results mainly explore the promotion of pro-environmental behaviors of college students through psychological contract and sustainable education, and effectively integrates educational interventions, psychological mechanisms, and social support to promote individual and social support for environmental behaviors.

In summary, this study advances the understanding of sustainable awareness education’s impact on pro-environmental behavior by integrating psychological contracts, subjective norms, and external support into a unified model. Through this approach, the study contributes to both theoretical and practical knowledge, offering insights that can inform the development of effective educational strategies and policy interventions that foster environmental responsibility.

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Model

This study takes the theory of planned behavior (TPB) as its core theoretical foundation and believes that individual behavior is mainly driven by behavioral intention, which is influenced by subjective norms, attitudes, and perceived control (Ajzen, I., 1991) [

10]. The robustness and parsimony of the TPB have led to its extensive application across diverse disciplines, most notably within the Information Systems (IS) field to explain technology adoption and usage behaviors. In IS research, the TPB has been successfully used to model users’ intentions to use various technologies, from enterprise systems to mobile applications. For instance, studies have consistently shown that users’ attitudes toward a system, the influence of peers and superiors, namely subjective norms, as well as their perception of system usage ability, namely individual behavioral control, are key factors influencing adoption intention and actual use (Venkatesh, V. et al. & Davis, F.D., 2003) [

11]. Taylor, S. & Todd, P.A. (1995) point out that the decomposed Theory of Planned Behavior provides a fuller understanding of behavioral intention by focusing on the factors that are likely to influence systems use through the application of both design and implementation strategies (Taylor, S. & Todd, P.A., 1995) [

12]. Building upon this strong theoretical foundation and its proven explanatory power, the TPB has also been effectively extended to the fields of education and sustainability to investigate pro-environmental behaviors. This vast body of literature underscores the TPB’s utility in explaining volitional behaviors in technologically driven contexts.

In order to further expand the applicable boundaries of this theory in the context of sustainable education, this paper introduces the psychological contract perspective to explain the responsibility internalization mechanism in the educational process and combines it with the resource activation perspective to analyze how external support regulates the generation path of behavioral intention through situational factors. To explore the key mechanisms that influence individual environmental behavior, this study developed a theoretical model based on four core variables: sustainable awareness education, subjective norms, psychological contract, and external support. Through a review of the relevant literature, we examined the influence pathways and interrelationships among these variables, aiming to reveal their roles in shaping environmental behavior. This study selected “sustainability awareness education”, “psychological contract”, and “external support” as core independent variables, aiming to reveal the multidimensional paths that affect the environmental behavior of college students, based on the following considerations: First, as a cognitive input variable, sustainable awareness education helps to enhance the individuals’ understanding and value recognition of environmental issues, and is the basic link in the formation of behavioral attitudes; Second, psychological contract, as an internalized psychological mechanism, can stimulate the individuals’ continuous behavioral performance based on a sense of responsibility in the absence of external coercion, which is consistent with the connotation of “perceived behavioral control” in the theory of planned behavior. Finally, external support is reflected in environmental factors such as policies, technology, and social recognition, which provide necessary resources and incentives for the implementation of behavior. The three jointly construct a three-dimensional behavior-driven framework of “cognition–psychology–situation”, which not only responds to the basic logic of TPB theory, but also expands its applicable boundaries in the study of green behavior in colleges and universities.

2.1. The Role of Sustainable Awareness Education

Sustainable awareness education has been widely recognized as a crucial method for addressing environmental issues. Recent studies show that this form of education significantly enhances individual environmental knowledge and stimulates environmental intentions through emotional resonance and value identification. For example, Salazar, C. & González, N. (2024) [

13] point out that environmental education provides people with the information they need to understand the causes and consequences of environmental issues, helping to promote positive attitudes toward nature. Similarly, Cogut et al. (2019) [

14] found a positive correlation between campus sustainability awareness and waste-prevention behavior, indicating that increased awareness can facilitate behavioral changes.

Additionally, Uralovich, K.S. et al. (2023) [

15] argued that environmental education is not only about knowledge transfer but also about action-oriented learning that fosters students’ ability to address environmental issues. Research by Van De Wetering, J. et al.& Thomaes, S. (2022) [

16] showed that eco-friendly practices in schools significantly enhanced students’ environmental awareness and behavior, highlighting the importance of integrating environmental awareness education into curricula. Lopes et al. (2018) [

17] also emphasized the value of integrating social, economic, and environmental content in higher education to cultivate sustainability awareness among students. Therefore, this study hypothesizes:

H1: Sustainable awareness education has a significant positive effect on environmental intentions.

2.2. The Role of Subjective Norms on Environmental Intentions

Subjective norms, a key variable in the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), refer to the social and moral pressure individuals feel when making behavioral choices (La Barbera, F. & Ajzen, I., 2020) [

18]. In the context of environmental behavior, subjective norms reflect the social expectations and sense of responsibility perceived by individuals. Research shows that individuals who feel environmental expectations from society, family, or friends are more likely to form environmental intentions (Gkargkavouzi et al., 2019) [

19], further suggesting that subjective norms are not only external social pressures. but also an internal moral responsibility that stimulates spontaneous environmental intentions. Thus, we propose:

H2: Subjective norms positively influence environmental intentions.

2.3. The Role of Psychological Contract on Environmental Intentions

The psychological contract originally described individuals’ subjective perceptions of responsibilities and obligations within organizational relationships. Recently, the concept has expanded to areas of social responsibility and environmental protection, providing an important perspective for understanding individual environmental behavior (Farrukh, M. & Wang, H., 2022) [

20]. Specifically, individuals who receive sustainable development education may develop a sense of responsibility toward nature, known as a psychological contract (Soares, M.E. & Mosquera, P., 2019) [

21]. Hong, Z. & Guo, X. (2019) [

22] suggested that establishing a psychological contract can lead individuals to view environmental responsibility as a voluntary commitment, thereby enhancing their environmental intentions. Thus, we propose:

H3: Psychological contract positively influences environmental intentions.

2.4. The Relationship Between Environmental Intention and Environmental Behavior

Environmental intention is widely recognized as a core driver of actual environmental behavior. According to La Barbera, F. & Ajzen, I. (2020) [

18], in the Theory of Planned Behavior, an individual’s behavioral intention directly influences the likelihood and intensity of that behavior, which also applies to environmental behavior. Environmental intention largely reflects an individual’s behavioral tendency in specific contexts and represents the internalization of environmental responsibility. Studies indicate that stronger environmental intentions correlate with a higher likelihood of actual environmental behavior in daily life, with the intensity of intention significantly affecting behavior frequency and quality (Peng, H., Li, B., Zhou, C. & Sadowski, B.M., 2021) [

23]. For instance, Zhang, Y., Du, J. & Boamah, K.B. (2023) [

4] found that individuals with strong environmental intentions were more likely to make eco-friendly decisions, such as adopting low-carbon lifestyles and reducing single-use items.

Therefore, this study considered environmental intention as the core driving factor in forming individual environmental behavior and proposes:

H4: Environmental intention positively influences environmental behavior.

2.5. Mediation Effects: Indirect Pathways of Subjective Norms and Psychological Contract

Subjective norms and psychological contracts may influence environmental behavior indirectly through environmental intentions. According to the Theory of Planned Behavior, subjective norms drive individuals to align with social expectations, which is particularly relevant in environmental behavior. When individuals perceive strong environmental expectations from society, their environmental intentions strengthen. Likewise, psychological contracts can influence behavior by enhancing environmental intentions, motivating individuals to view environmental responsibility as a self-imposed obligation (Paillé, P. & Raineri, N., 2016) [

24]. Thus, we hypothesize:

H5: Subjective norms indirectly influence environmental behavior through environmental intentions.

H6: Psychological contract indirectly influences environmental behavior through environmental intentions.

2.6. Moderating Role of External Support

External support plays a significant moderating role in shaping individual environmental behavior by reducing the actual costs associated with environmentally friendly actions and enhancing behavioral efficacy. External support typically includes policy incentives, social resources, and economic incentives that reduce the financial burden of environmental behavior, encouraging eco-motivated decision-making. Social support resources, such as community environmental projects, also boost individual confidence, promoting more proactive environmental engagement (Shen, M., & Wang, J., 2022) [

25]. In the relationship between psychological contract and environmental intention, external support serves as a significant moderator. When individuals perceive strong external support, their environmental responsibility is further activated, amplifying the effect of psychological contract on environmental intention. Therefore, we hypothesize:

H7: External support moderates the relationship between psychological contract and environmental intentions.

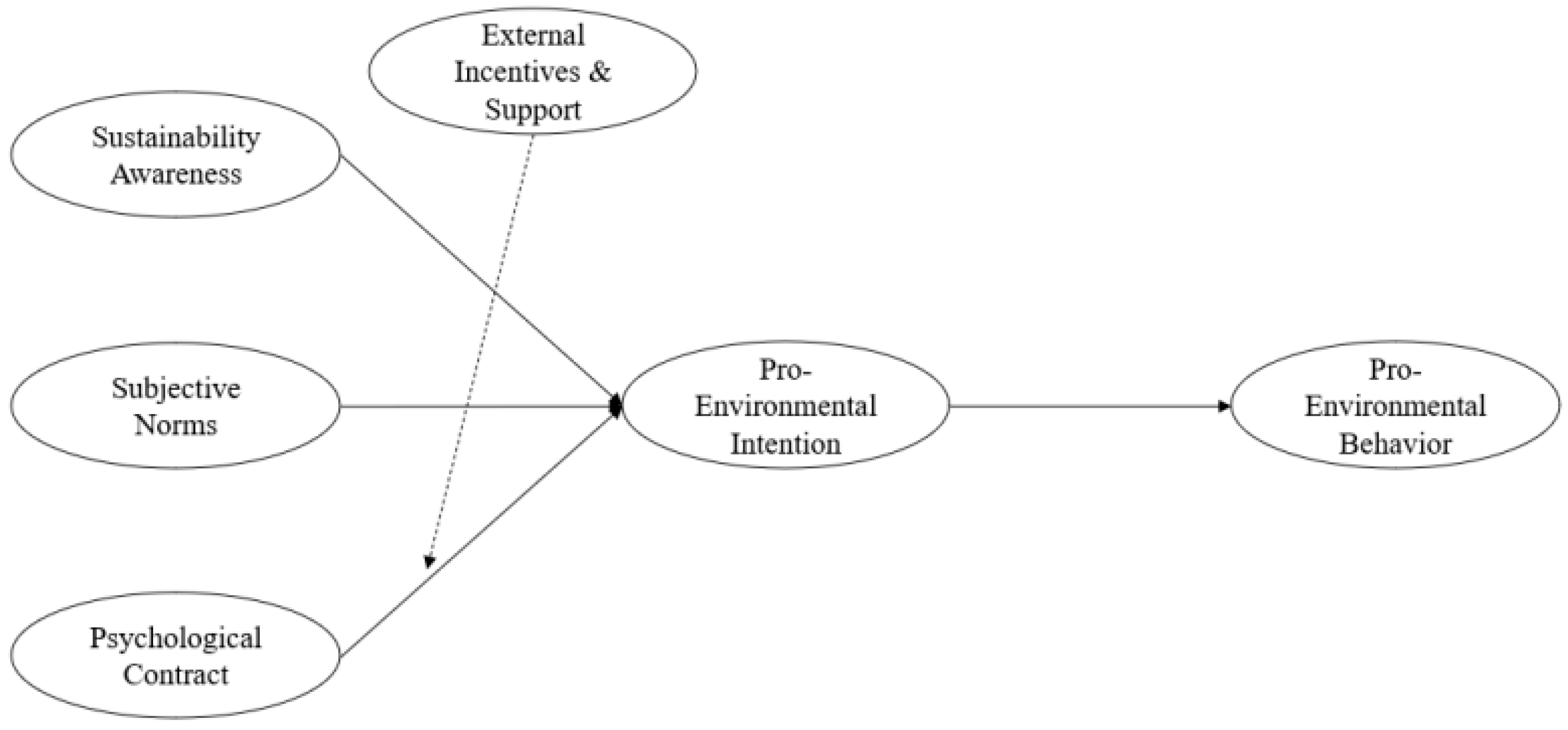

2.7. Proposed Theoretical Model

Based on the literature review and research hypotheses, this study constructed an integrated theoretical model to explain the role of sustainable awareness education, subjective norms, psychological contract, and external support in shaping individual environmental behavior. The model includes the following key pathways. First, sustainable awareness education indirectly affects behavior through psychological contract, enhancing individuals’ sense of environmental responsibility, which strengthens environmental intention and promotes behavior. Second, subjective norms and psychological contract act as important mediating variables, indirectly encouraging environmental behavior through enhanced environmental intention. Finally, external support serves as a moderating variable that not only moderates the relationship between psychological contract and environmental intention, but also strengthens the effect of sustainable awareness education on psychological contract.

Due to the theory of planned behavior, this study assumed that the impact of sustainable awareness education, psychological contract, and subjective norms on individual environmental behavior is indirectly achieved by affecting their behavioral intentions, rather than directly acting on behavioral performance. Behavioral intention plays the role of a mediating bridge, reflecting the cognitive regulation mechanism of individuals in the transformation from cognitive formation to psychological contract establishment to actual behavior. Therefore, in the model construction and path setting, this paper treated intention as a mediating variable, and conducted corresponding mediation effect tests in the result analysis.

This theoretical model aims to reveal the complex relationships involved in forming individual environmental behavior, providing a basis for policy formulation and practical intervention (Hair, J.F., 2009) [

26]. By constructing this model, the study seeks to clarify how multiple factors collectively influence the formation of environmental behavior, offering theoretical support for future educational strategies and incentive mechanisms.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Research Design

This study utilized a structured questionnaire to examine the relationships between sustainable awareness education, subjective norms, psychological contracts, external support, and pro-environmental intention and behavior. The research design included three key stages: data collection, variable measurement, and data analysis. The questionnaire was adapted from established scales in prior research and refined based on pilot testing feedback to enhance validity and reliability. Structural equation modeling (SEM) was employed to analyze the relationships and interaction effects among variables, ensuring a rigorous examination of the proposed hypotheses.

The theoretical model of variable relationships is shown in

Figure 1. To ensure the adequacy of the sample size for SEM analysis, the minimum required sample was estimated using the Free Statistics Calculator (Soper, version 2025). Given six latent variables and thirty-four observed indicators, with α = 0.05, power = 0.80, and an anticipated medium effect size (0.30), the required sample size was approximately 220. The actual sample of 413 respondents therefore exceeds this threshold, ensuring sufficient statistical power and model stability.

3.2. Sample and Data Collection

The study employed random sampling, distributing a total of 500 questionnaires, of which 413 valid responses were retained, resulting in an effective response rate of 82.6%. The sample included university students from Beijing in diverse academic disciplines, including engineering, management, education, and social sciences, aiming to ensure broad representation of the student population. Data collection was conducted through both online and offline channels between May and July 2024. The survey was administered in Chinese, using items translated and adapted from established English instruments following a translation–back translation process to ensure content equivalence. All items were rated on seven-point Likert scales (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). Example items include “I actively participate in environmental protection activities on campus”, “People around me expect me to act in an environmentally responsible way”, and “My university provides sufficient facilities or resources for environmental protection”. The questionnaire was structured into six sections covering demographic information, sustainable awareness, subjective norms, psychological contracts, external support, pro-environmental intention, and pro-environmental behavior.

This paper conducted a statistical analysis of the key demographic characteristics of the sample. Among the 413 valid questionnaires collected in this study, 56.4% (n = 233) were female and 43.6% (n = 180) were male, and the gender ratio of the sample was relatively balanced. The average age of the respondents was 20.8 years old (standard deviation was 1.64), mainly concentrated between 18 and 25 years old, which is in line with the age structure characteristics of current college students. In terms of educational structure, undergraduates accounted for 61.7% and postgraduates accounted for 38.3%, covering different grades and educational stages. In general, the sample of this study had the characteristics of concentrated age, reasonable gender distribution, and wide coverage of educational levels, which provided a good basis for the analysis and interpretation of the research results.

3.3. Variable Measurement

Variables were measured using validated scales, with confirmed reliability and validity to ensure data accuracy. Each variable was measured as follows:

Sustainable Awareness: Measured using a scale adapted from Rickinson, M (2013) [

27], focusing on individuals’ environmental knowledge and attitudes toward environmental protection, with items rated on a seven-point Likert scale.

Subjective Norms: The Theory of Planned Behavior from La Barbera, F and Ajzen, I. (2020) [

18], capturing perceived social expectations and moral responsibilities related to pro-environmental behavior.

Psychological Contract: Measured using a scale adapted from Lee and Chen (2018) [

28], reflecting individuals’ internalized sense of responsibility toward environmental protection in a societal context.

External Support: Assessed using a scale based on Zhang, Y., Du, J. & Boamah, K.B. (2023) [

4], evaluating perceived policy incentives and social support mechanisms for pro-environmental behavior. In this study, “external support” refers to the positive factors from the environmental context that individuals perceive when participating in environmental protection behaviors, including the following five dimensions: (1) Policy support: such as the garbage classification system and green consumption incentive policies launched by the government or universities; (2) Tool support: such as the provision of public bicycles, intelligent garbage classification systems, energy-saving equipment and other facilities and resources; (3) Social support: such as the encouragement and participation of family members, friends, and classmates; (4) Information support: obtaining environmental protection knowledge and behavior guidelines through campus publicity, online platforms, and community channels; (5) Economic support: such as monetary rewards for environmental protection behaviors, green consumption discounts, and carbon credit systems.

The above five dimensions were all measured using the Likert five-point scale, and sample items included: “My school/community often provides facilities or services related to environmental protection”, “People around me support me in participating in environmental protection behaviors”, “I can easily obtain guidance information on environmental protection behaviors”, etc.

Pro-Environmental Intention: This variable captures the degree of commitment to pro-environmental actions, emphasizing normative influences and self-identity as significant predictors (Wu, J.S., Font, X. & Liu, J., 2021) [

29]. It also considers factors addressing the intention–behavior gap (Wang, H. & Mangmeechai, A., 2021) [

30].

Pro-Environmental Behavior: Measured using a scale developed by Jackson, J., Pinckney, J. & Rivers, M. (2022) [

9], evaluating routine environmental actions such as waste sorting and energy conservation.

Reliability refers to the stability and consistency of the questionnaire measurement results. One commonly used measure of reliability is internal consistency reliability, which assesses the consistency among multiple items and is represented by the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. A Cronbach’s alpha above 0.7 indicates acceptable reliability, while a value above 0.8 suggests excellent reliability.

As shown in

Table 1, the Cronbach’s alpha values for sustainable awareness, subjective norms, psychological contract, pro-environmental intention, and pro-environmental behavior were all above 0.8, indicating high reliability for these scales. The Cronbach’s alpha for external incentives and support was 0.770, suggesting that the reliability of this scale is acceptable.

3.4. Data Analysis Methods

Data analysis was conducted using SPSS 26 and Mplus 8.3, following four sequential steps. First, descriptive statistics were performed in SPSS 26 to calculate the means, standard deviations, skewness, and kurtosis for each variable, confirming an appropriate data distribution. Second, Harman’ s single-factor test was used to examine common method bias, with a single-factor variance of 37.631%, below the 40% threshold, indicating no significant common method bias.

Third, exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) were conducted in Mplus 8.3 to validate the reliability and validity of the measurement scales. The EFA showed a KMO value of 0.912 and a significant Bartlett’ s test, supporting the factorability of the data. CFA results indicated that the composite reliability (CR) and average variance extracted (AVE) met acceptable standards, supporting convergent and discriminant validity for each variable.

Finally, SEM was conducted in Mplus 8.3 using latent moderated structural equations (LMS) to test the moderating effect of external support on the relationship between psychological contracts and pro-environmental behavior. To assess the significance of moderated mediation effects, a bootstrap procedure with 1000 samples was used to analyze pathway differences across varying levels of external support. Model fit indices indicated strong model adequacy (χ2/df = 2.968, RMSEA = 0.069, CFI = 0.928, TLI = 0.919, SRMR = 0.041), validating the robustness of the theoretical model.

This study used structural equation modeling to empirically test the theoretical model. Both the path analysis and mediation effect analysis were centered around the H1–H7 hypotheses proposed above, which are typical hypothesis-driven analyses. To further enhance the understanding and graphical support of the mediation mechanism, the study also conducted marginal effect visualization and inter-group comparative analysis. This part is an exploratory analysis, which aims to graphically verify and robustly supplement the key mechanisms, and does not affect the theoretical explanation logic of the main path test.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were conducted using SPSS 26.0, and the results are shown in

Table 2. The mean and standard deviation for each variable are as follows: sustainable awareness (M = 6.309, SD = 1.009), subjective norms (M = 5.541, SD = 1.625), psychological contract (M = 5.588, SD = 1.302), pro-environmental intention (M = 6.095, SD = 1.189), pro-environmental behavior (M = 6.309, SD = 0.793), and external incentives and support (M = 4.100, SD = 1.101).

4.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was conducted using Mplus 8.3 to evaluate the fit of the measurement model and to confirm the underlying factor structure of the constructs. The six-factor model yielded satisfactory fit indices: χ

2 = 994.196, df = 335, χ

2/df = 2.968, RMSEA [90% CI] = 0.069 [0.064, 0.074], CFI = 0.928, TLI = 0.919, and SRMR = 0.041. These indices indicate a good fit between the model and the observed data, meeting the recommended thresholds for model fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999) [

31].

4.2.1. Convergent Validity

To assess convergent validity, both Average Variance Extracted (AVE) and Composite Reliability (CR) were examined. AVE evaluates the extent to which a latent variable explains its indicators, with values above 0.5 indicating acceptable convergent validity (Hair et al., 2010) [

32]. CR assesses internal consistency, with a value above 0.7 generally indicating satisfactory reliability.

As shown in

Table 3, the AVE and CR values for each construct met or exceeded the recommended thresholds. The AVE values for sustainable awareness (0.700), subjective norms (0.759), psychological contract (0.682), pro-environmental intention (0.724), pro-environmental behavior (0.702), and external incentives and support (0.536) confirm that the constructs explained a sufficient portion of variance in their indicators. Likewise, CR values, ranging from 0.774 (external incentives and support) to 0.950 (psychological contract), demonstrated adequate internal consistency across constructs, supporting the convergent validity of the measurement model.

4.2.2. Discriminant Validity

Discriminant validity was evaluated by comparing the square root of AVE values for each construct with the correlations between constructs. For discriminant validity to be established, each construct’s square root of AVE should be greater than its correlations with other constructs (Fornell & Larcker, 1981) [

33]. As shown in

Table 4, each construct’s AVE square root (diagonal values) was higher than its inter-construct correlations, indicating that each construct was distinct from the others.

The CFA results affirm both convergent and discriminant validity, supporting the adequacy of the measurement model and confirming that each construct uniquely contributes to the theoretical framework. This robust validation process ensures that the constructs reliably measured their intended latent variables, providing a sound basis for subsequent structural analyses.

4.3. Structural Model Testing Analysis

The hypothesized model was tested using Mplus 8.3 with the Latent Moderated Structural Equations (LMSs) approach. First, we examined the baseline model without the latent interaction term. Model fit indices for the baseline model were as follows: χ2 = 1110.635, df = 339, χ2/df = 3.276, RMSEA [90% CI] = 0.074 [0.069, 0.079], CFI = 0.916, TLI = 0.906, SRMR = 0.080. Next, we tested the model with the latent interaction term. Results indicated improved model fit, with the baseline model AIC = 31,401.257 compared to AIC = 31,391.542 for the interaction model, yielding ΔAIC = 9.715, suggesting that the moderated mediation model offered a better fit. Additionally, the log-likelihood for the baseline model was −15,605.628, improving to −15,599.771 with the interaction term, yielding a −2LL difference of 11.714 with Δdf = 1. The chi-square test for the −2LL value was significant (p < 0.001), further supporting the superiority of the moderated mediation model.

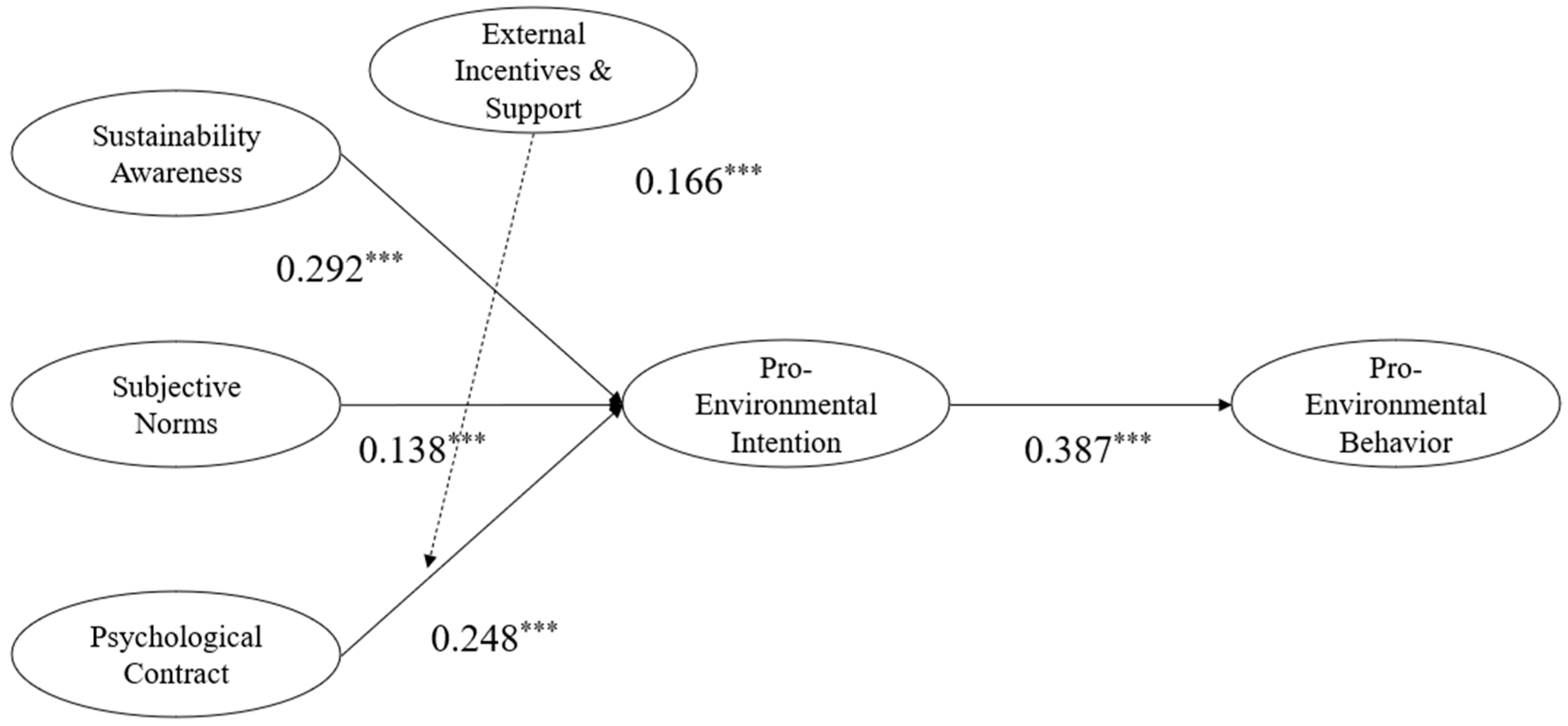

As shown in

Table 5 and

Figure 2, sustainability awareness (β = 0.292,

p < 0.001), subjective norms (β = 0.138,

p < 0.001), and psychological contract (β = 0.248,

p < 0.001) positively predicted environmental intention. The interaction term between psychological contract and external incentives/support positively predicted environmental intention (β = 0.166,

p < 0.001), indicating that external incentives/support moderated the relationship between psychological contract and environmental intention. Environmental intention was a significant predictor of environmental behavior (β = 0.387,

p < 0.001).

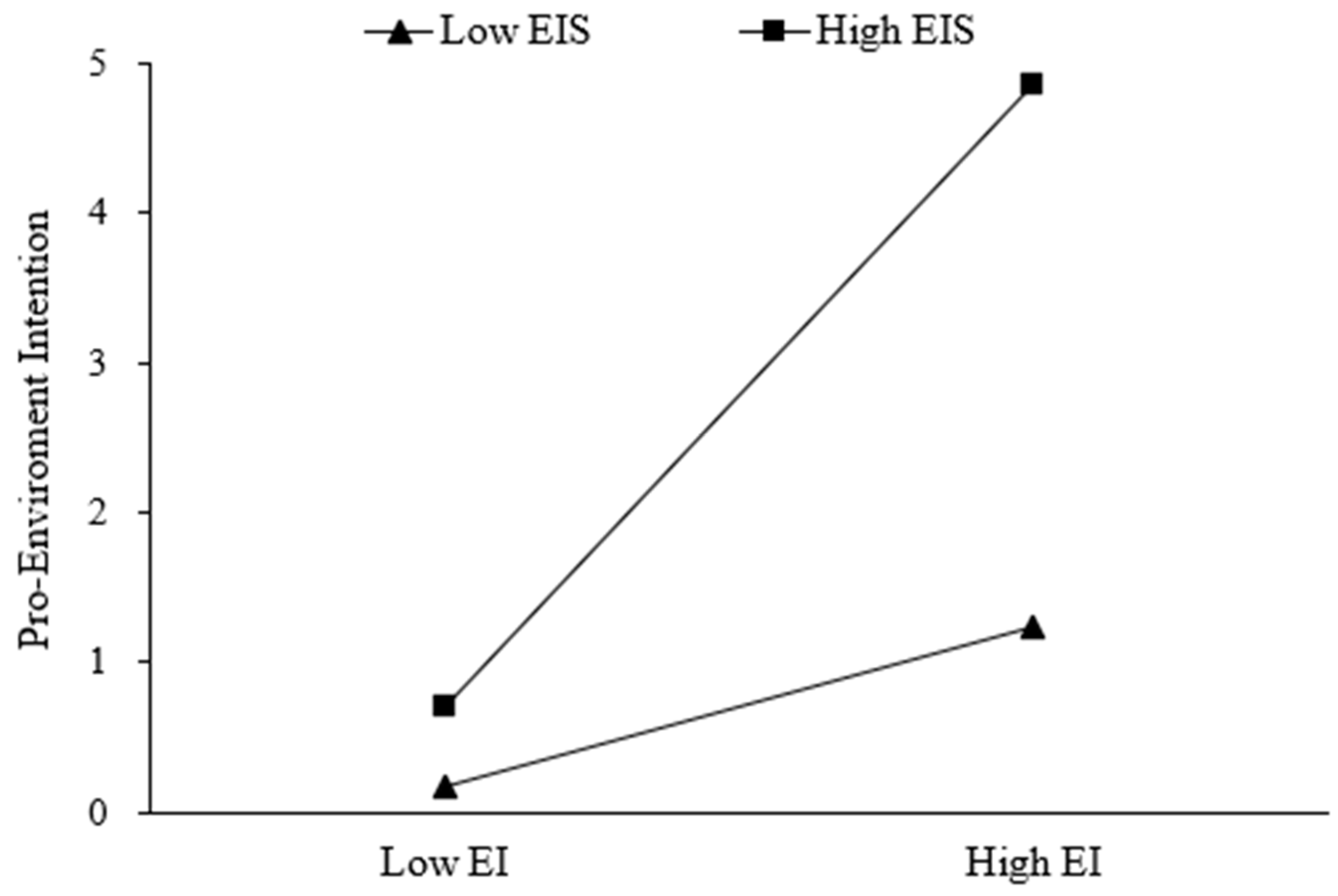

A simple slope analysis further examined the moderating effect of external incentives/support. Simple slope analysis is an auxiliary technique based on regression models, used to evaluate whether the independent variable has a significant impact on the dependent variable at different levels of the moderating variable. Specifically, it tests the conditional changes in the relationship between the independent variable and the dependent variable by calculating the simple slope of the variable at a specific value (Toothaker, L. E., 1994) [

34]. The main purpose of simple slope analysis is to reveal the specific form of the moderating effect, in order to help determine whether the independent variable has a significant impact on the dependent variable at different levels of the moderating variable. Simultaneously supporting the testing of research hypotheses, such as H7 (the relationship between external support regulating psychological contract and environmental intention) in this study, empirical evidence was provided through simple slope analysis. As illustrated in

Figure 3, when external incentives/support were low (M − 1SD), the positive predictive effect of psychological contract on environmental intention was not significant (β = 0.082, SE = 0.062, t = 1.318,

p = 0.188). In contrast, when external incentives/support were high (M + 1SD), psychological contract significantly and positively predicted environmental intention (β = 0.414, SE = 0.063, t = 6.587,

p < 0.001).

The analysis showed that under conditions of low external incentives and support, the influence of psychological contract on environmental intention was relatively weak. However, with high external incentives and support, psychological contract had a stronger, significant positive effect on environmental intention. This finding highlights the amplifying role of external incentives and support in strengthening the positive association between psychological contract and environmental intention.

To examine the mediation effects, a Bootstrap method with 1000 resamples was employed. A mediation effect is considered significant if the 95% confidence interval (CI) does not include zero. As presented in

Table 6, the analysis revealed that environmental intention significantly mediated the relationship between sustainability awareness and environmental behavior, with an effect size of 0.113. Similarly, the mediating role of environmental intention between subjective norms and environmental behavior was significant, yielding an effect size of 0.054.

Further analysis indicates that when external incentives and support are low (M − 1SD), the mediating effect of environmental intention on the relationship between psychological contract and environmental behavior is not significant. In contrast, under high external incentives and support (M + 1SD), environmental intention significantly mediates this relationship, with an effect size of 0.160.

5. Discussion and Implications

5.1. Research Findings and Discussion

This study empirically validated the multifaceted mechanisms by which sustainability awareness, subjective norms, psychological contracts, environmental intentions, and external incentives and support influence pro-environmental behavior. It should be noted that in the theoretical model, this paper assumed that each antecedent variable (sustainability awareness education, subjective norms, and psychological contracts) had an indirect impact on behavior through behavioral intention, and did not set a direct path for its environmental protection behavior. This processing logic was derived from the core assumption of the theory of planned behavior, that is, behavioral intention is the most direct predictor of behavior, and antecedent variables mainly achieve behavioral transformation through intention (Lee, S. & Vincent, C., 2021) [

35]. Therefore, in the data analysis, this paper only examined the mediating effect of behavioral intention, and did not set or test the direct impact path of antecedent variables on behavior. The specific research findings are as follows:

Increasing sustainability awareness significantly enhances environmental intention. The path coefficient test results of the structural model provide direct evidence for the research hypothesis. Responding to H1 proposes that sustainable awareness education will have a positive impact on environmental intentions. The analysis results support this hypothesis (β = 0.292,

p < 0.001), indicating that the more sustainable education students receive, the stronger their intention to adopt environmental behaviors. This study found that individuals with higher sustainability awareness were more likely to develop positive environmental intentions. This result suggests that enhancing environmental awareness can strengthen individuals’ sense of responsibility for environmental protection, thereby fostering a more proactive environmental attitude. Sustainability awareness provides individuals with a cognitive foundation of environmental responsibility, helping them make more environmentally conscious choices when faced with decisions (Ekamilasari, E. & Pursitasari, I.D., 2021) [

36]. Education and public awareness campaigns that promote sustainability awareness can thus increase public environmental intentions and lay the groundwork for achieving broader environmental goals.

Subjective norms and social expectations significantly enhance environmental intention, responding that H2’s prediction of the positive impact of subjective norms on environmental intentions is also supported by the results (β = 0.138,

p < 0.001). This indicates that the expectations of important others from society and campus, such as classmates and teachers, can effectively enhance students’ environmental intentions. This study supports the role of subjective norms in the Theory of Planned Behavior, demonstrating that social environment and expectations significantly influence the formation of environmental intentions. The guidance of social norms and moral responsibility can lead individuals to internalize pro-environmental behaviors as conscious actions aligned with social expectations, thereby increasing their environmental intentions. In practice, establishing environmental role models and promoting socially endorsed environmental behaviors can further strengthen individuals’ sense of social responsibility and moral obligation, encouraging them to spontaneously adhere to environmental norms and ultimately form positive environmental intentions (Helferich, M., Thøgersen, J. & Bergquist, M., 2023) [

37].

Psychological contracts play a critical role in forming environmental intention. A psychological contract represents an individual’s internal commitment to environmental protection. Assuming that H3 predicts a positive impact of psychological contract on environmental intention, the data analysis results significantly support this pathway (β = 0.248, p < 0.001). When a psychological contract exists between individuals and the environment, they are more likely to view pro-environmental behavior as their responsibility, thereby strengthening their environmental intention. This study confirms the significant influence of psychological contracts on environmental intentions, suggesting that the perception of environmental responsibility is not merely a passive response to social pressure but an active, internalized commitment. This finding provides a theoretical basis for understanding individuals’ voluntary involvement in environmental protection, highlighting the importance of cultivating a sense of environmental responsibility in promoting pro-environmental behavior.

Environmental intention serves as a significant mediator in the formation of pro-environmental behavior. The corresponding hypothesis H4, that environmental intention directly predicts environmental behavior positively, received very strong support (β = 0.387, p < 0.001). Environmental intention is not only a direct driver of pro-environmental behavior but also serves as a mediator in the paths from sustainability awareness, subjective norms, and psychological contracts to pro-environmental behavior. This study found that individuals’ environmental intentions can translate their environmental knowledge, social expectations, and psychological commitments into actual pro-environmental behaviors. This finding validates the mediating effect of environmental intentions, demonstrating that the generation of intention is a crucial step in forming pro-environmental behavior. Enhancing individuals’ environmental intentions can significantly increase the likelihood of pro-environmental behavior.

Responding to H5 and H6, in order to test the indirect effects of subjective norms and psychological contracts on environmental behavior through environmental intentions, through mediation analysis, the overall indirect effects were significant (effect value = 0.160, 95% CI [0.108, 0.218]). More importantly, we further examined the mediating effect under different levels of external support. The data results show that this mediating effect is only significant when the level of external support is high. This indicates that a psychological contract drives behavior as a conditional indirect effect, further enriching the connotations of H5 and H6, and supporting our theoretical model.

External incentives and support moderate the relationship between psychological contracts and environmental intention. According to empirical results, this finding strongly supports H7, indicating that sufficient external support is a key contextual factor in activating psychological contracts and transforming them into behavioral intentions. The study indicates that psychological contracts have a stronger positive impact on environmental intentions in contexts with high external support. Specifically, when the external environment provides individuals with resources, economic support, or social recognition, their psychological contracts are more likely to translate into actual environmental intentions. This finding further supports the critical role of external incentives in fostering environmental responsibility. External support not only reduces the barriers to pro-environmental behavior but also amplifies intrinsic motivation, helping to transform psychological contracts into actual pro-environmental behavior (Silvi, M. & Padilla, E., 2021) [

38].

In summary, the results of this study support a multilayered mechanism by which sustainability awareness, subjective norms, psychological contracts, environmental intentions, and external incentives promote pro-environmental behavior. By enhancing individuals’ sustainability awareness, subjective norms, and psychological contracts, along with providing sufficient external incentives and support, environmental intentions can be effectively strengthened, ultimately fostering actual pro-environmental behavior.

5.2. Theoretical and Practical Implications

Based on the theory of planned behavior, this study constructed a chain mechanism of “sustainable awareness education–psychological contract–environmental intention–environmental behavior”, and expanded the scope of application of the TPB model in the study of green behavior in colleges and universities. The study introduced the psychological contract as a variable in the emotional cognitive dimension into the TPB framework and strengthened the explanation of the role of “intrinsic responsibility” in the process of generating behavioral intention. It is worth noting that the results of this study are consistent with the classic research findings based on TPB in the field of information systems, but there are also interesting differences. In previous studies, perceived behavioral control was often the strongest factor in predicting behavioral intention, especially in contexts involving new technology learning. However, in this study, although external support is crucial as an operational manifestation of perceived behavioral control through its moderating effect, its direct influence was relatively lower than subjective norms and psychological contracts. This difference may stem from fundamental differences in behavioral backgrounds, such as technology adoption often involving individual decisions to solve clear instrumental problems, while pro environmental behavior is more of a sustained social behavior driven by social norms and moral responsibility. There were also differences in the research subjects and data measurement, for example, IS research subjects are mostly enterprise employees, whose behavior is significantly influenced by organizational authority and performance requirements. This study focused on a group of college students, whose behavior is more susceptible to the influence of peer atmosphere (campus culture) and values education. At the same time, the traditional TPB framework focuses on rational decision-making, while this study introduced emotional and moral dimensions through the variable of psychological contract, explaining that environmental protection is an individual’s inherent responsibility rather than a social conformity behavior. Previous studies often regarded external support as a direct predictor variable, while this study redefined it as a moderating variable to enhance intrinsic motivation. In addition, the study also verified the moderating effect of external support on the relationship between psychological contract and environmental intention and revealed the influence mechanism of situational support factors in environmental education intervention. These findings enrich the theoretical extension of TPB to the “cognition–motivation–behavior” path in the education field, and also provide a theoretical basis for the subsequent “psychological contract” and “external motivation” dual-drive model.

At the practical level, the results of this study have certain guiding significance for the green education practice in colleges and universities. First, the study found that sustainable awareness education can significantly improve college students’ environmental protection intentions, indicating that in the curriculum setting and educational activities of colleges and universities, it is necessary to continuously strengthen the embedding of values such as ecological civilization and sustainable development goals. Second, the mediating role of psychological contract suggests that schools should attach importance to the construction of students’ “inner identity”, and can inspire students to regard environmental protection behavior as an active responsibility through green volunteer activities and an environmental protection project system. Third, the moderating effect of external support shows that only concept education is not enough to drive behavioral transformation, and it is also necessary to improve the physical support environment, such as green points incentives, energy-saving facilities, and green community building, so as to enhance the accessibility of behavior and motivation maintenance. The research results provide empirical references for the construction of green campuses at colleges and universities and the intervention path of college students’ environmental protection behavior.

6. Conclusions

This study investigated the multifaceted roles of sustainable awareness education, subjective norms, psychological contracts, and external support in shaping university students’ pro-environmental behaviors. By integrating these elements within a moderated mediation model, this research highlights how educational interventions and psychological constructs interact to foster sustainable behaviors.

6.1. Research Conclusions

The study identified that sustainable awareness education significantly strengthens environmental intentions, helping students internalize sustainability concepts and develop environmental responsibility. Subjective norms also play a crucial role, with social expectations reinforcing students’ commitment to eco-friendly actions. Psychological contracts emerged as a powerful influence, encouraging students to perceive environmental stewardship as a personal and societal obligation. Additionally, external support enhances these relationships by providing the resources and incentives necessary to translate intentions into action. Collectively, these findings contribute to both theoretical and practical knowledge on promoting sustainable behaviors through a combination of educational, psychological, and external factors.

6.2. Recommendations

This study provides important insights into the construction of environmental behavior theory and the practice of sustainable development education in universities. Specific recommendations can be summarized as the following five points:

6.2.1. Incorporate Sustainability into University Curricula and Experiential Learning Programs

Raising sustainability awareness is essential to developing environmental intentions among students (Romero-Colmenares, L. M. & Reyes-Rodríguez, J. F., 2022) [

39]. Universities should integrate sustainability topics into diverse course offerings and campus-based learning programs, using case studies and hands-on projects that allow students to experience environmental challenges firsthand. For example, outdoor ecology courses, environmental impact assessments, and field research projects could help students grasp the delicate balance within ecosystems and the consequences of human actions (Barba-Sánchez, V. & del Brío-González, J., 2022) [

40]. This type of experiential learning reinforces environmental responsibility and strengthens students’ commitment to sustainability (Fang, J. & O’Toole, J., 2023) [

41]. Integrating sustainability across curricula and encouraging interdisciplinary collaboration help students build a holistic understanding of environmental protection, laying the foundation for sustainable practices in various career paths.

6.2.2. Cultivate a Green Campus Culture Through Social Norms and Environmental Role Models

Since subjective norms significantly influence students’ environmental intentions, universities should establish a campus culture that supports sustainability. This can be achieved by promoting environmental norms and social expectations, creating dedicated environmental clubs, and organizing green initiatives that set a positive tone across campus. Research shows that presenting environmental role models, such as student environmental ambassadors or standout eco-friendly organizations, strengthens students’ alignment with pro-environmental behaviors and encourages wider participation (Stern, M. J., et al., 2018) [

42]. Additionally, implementing recognition programs like “Green Campus Champion” awards or “Eco-Leader” badges can reward students who excel in sustainability efforts, motivating others to adopt similar behaviors.

6.2.3. Establish Psychological Contracts for Environmental Responsibility

Responsibility education can foster psychological contracts that drive students’ environmental intentions. Universities should integrate environmental responsibility themes into courses and campus activities, encouraging students to view environmental stewardship as a personal and social obligation (Nguyen, H. A. T. et al., & Intaratat, K., 2025) [

43]. For example, launching a “Student Sustainability Pledge” at the beginning of the academic year, where students commit to environmental goals, reinforces their dedication to campus sustainability (Leal Filho et al., 2020) [

44]. By embedding environmental responsibility into the academic curriculum—such as through assignments that explore the impacts of environmental issues—students can internalize their role in sustainability, potentially carrying this commitment into future careers.

6.2.4. Implement Incentive-Based Programs for Pro-Environmental Actions

External incentives significantly boost students’ environmental intentions, so universities should create programs that reward sustainable actions on campus. A “Green Points Program” could allow students to earn points for energy conservation, recycling, and participation in environmental activities, which can then be redeemed for campus benefits like dining vouchers or discounts. Moreover, setting up accessible recycling stations across campus and providing incentives for using these resources could reinforce sustainable behaviors. Such incentive-based systems not only lower economic barriers to sustainability but also promote good habits aligned with environmental goals (He, S., Luo, Y., Qu, Y. & Hu, X., 2024) [

45].

6.2.5. Build Campus-Based Community Support Networks for Environmental Initiatives

Social support networks are essential in fostering environmental intentions and behaviors. Universities should cultivate a strong community culture around sustainability by organizing group-based environmental projects and activities. Regular events like “Campus Clean-Up Days”, “Sustainability Fairs”, and “Recycling Drives” engage students actively, promoting environmental awareness and community involvement. Studies show that collective activities strengthen students’ sense of belonging, increasing their likelihood of sustaining pro-environmental behaviors within a group setting. Developing these campus-based community networks not only supports students’ ongoing environmental engagement but also helps establish a broader sustainability culture throughout the university.

6.3. Research Limitations

Despite its contributions, this study has several limitations. First, regarding the sample characteristics, two potential limitations should be noted. Although the sample appropriately consisted of university students, it may not have fully represented the diversity within this population. The findings could be influenced by an overrepresentation of students from specific academic disciplines or from a particular university culture. Consequently, the generalizability of the model to the broader, more heterogeneous university student population across different institutions and cultural contexts should be interpreted with caution and remains a subject for future research. Second, the study relied on self-reported data, which can introduce biases in capturing genuine pro-environmental behaviors. Third, while this study used a cross-sectional design to capture relationships between variables, longitudinal studies would provide more robust insights into the effects of sustainable awareness education and psychological contracts on behavior. It should also be pointed out that this paper did not include the interaction path between variables in the model design. For example, whether external support will moderate the impact of sustainable education cognition on the formation of psychological contract has not yet been empirically tested. Although this design helps to maintain the simplicity and explanatory power of the model structure, it also limits the revelation of the complexity of the variable relationship. Subsequent research can try to introduce moderation effects or conditional process analysis based on a larger sample size and more sophisticated theoretical settings to further expand the extrapolation power and theoretical depth of the model.

6.4. Future Research Directions

Future studies could extend these findings by exploring additional environmental factors, such as cultural or policy differences across regions, to examine the universality of the model. Researchers might also apply this model in different educational and social contexts to assess its applicability outside university settings. Additionally, employing longitudinal designs could reveal how sustainable awareness education and psychological contracts influence behavior over time, providing deeper insights into the lasting impact of these interventions on pro-environmental actions. At the same time, while expanding the sample to university students from diverse academic disciplines enhanced the study’s generalizability, this modification introduced new limitations. Students from different disciplines may have different curriculum settings, opportunities to engage in environmental education, or interests in sustainable behavior. Future studies could adopt a stratified sampling approach to capture disciplinary characteristics while incorporating institutional-level variables (e.g., sustainability curriculum coverage, green campus policies) as control factors. Cross-cultural comparisons involving universities with varying sustainability indices would further validate the model’s universality. In summary, this study offers a comprehensive framework for understanding and promoting pro-environmental behavior among students, underscoring the importance of integrating educational initiatives, psychological commitments, and external support to foster a culture of sustainability in higher education.