Abstract

While numerous researchers and practitioners view overtime as uniformly detrimental, growing evidence reveals complexity and overlooked benefits, particularly for social inclusion. This study focuses specifically on the impact of overtime work on social inclusion within the framework of Chinese culture and institutions, as well as the moderating effect of environmental factors. Drawing on extended-self theory, we propose that as overtime hours increase, the association between work hours and social inclusion becomes U-shaped. By contrast, this association may be moderated by environmental factors, such as work value. As expected, by conducting hierarchical regression analysis following Janssen’s three-step procedure, a sample (n = 529) of Chinese employees from the China Labor-Force Dynamics Survey (CLD) supported that the U-shaped relationship between overtime work and employees’ social inclusion. In addition, the curvilinear association between overtime work and social inclusion is significantly moderated by employees’ work values. The findings align with sustainability agendas that emphasize decent work, inclusion, and long-term employee well-being. Theoretical and practical implications are discussed.

1. Introduction

In recent years, global attention to sustainable development has continued to grow, and the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) focus on improving human well-being and achieving inclusive and balanced development. Among them, Goal 8 (“Decent Work and Economic Growth”) and Goal 10 (“Reduced Inequalities”) are particularly relevant to labor practices and social inclusion. In order to safeguard employees’ rights and well-being. Governments worldwide have instituted varying restrictions regarding standard working hours. For instance, the European Union’s Working Time Directive mandates a maximum of 48 h per week (including overtime) [1], France limits the standard workweek to 35 h [2], and Turkey set a legal cap of 45 h [3]. Notwithstanding these rules, global research indicates that overtime work remains widespread: Over one-third of employees globally consistently work in excess of 48 h per week [4]. The situation is particularly severe in Asia, where average weekly hours often exceed 60 in Japan [5], and working time in China has increased by 22% for both men and women over the past decade [6].

The pervasive culture of overtime work in China, driven by its rapid economic expansion, reflects a broader global tension between quantitative growth and qualitative well-being. While extended working hours have historically contributed to economic output in China and other industrialized nations like Japan and France, this model raises critical questions about its long-term sustainability and social equity. Inclusivity, by contrast, serves as a fundamental pillar for sustainable development by ensuring equitable opportunities, enhancing employee well-being and loyalty, and fostering a resilient workforce that drives innovation-benefiting individuals, enterprises, and national economies alike. As one of the world’s major economies, China has made significant progress in promoting employment opportunities and improving working conditions, but it still faces challenges in ensuring that economic growth is transformed into equitable and inclusive well-being.

In September 2016, the Chinese government released the National Plan on Implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (NPIASD) [7], which outlines China’s guiding principles, strategic approaches, and implementation pathways for achieving the SDGs. At the individual level, an inclusive work environment enhances employees’ psychological safety, wellbeing, and work engagement, while reducing burnout and turnover intentions, thereby promoting long-term career health and overall welfare. At the organizational level, inclusive management is positively associated with employee performance, organizational creativity, and ESG ratings. At the national level, an inclusive labor system helps reduce social inequality, strengthen labor rights protection, and improve the overall quality of human capital.

However, research on the effects of working long hours yields varied results. On the one hand, a large corpus of occupational health research has linked overtime to unfavorable individual outcomes such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, metabolic syndrome, psychological distress, depression, anxiety, and work–life conflict [8,9,10,11,12,13]. On the other hand, other research imply that extended work hours may improve employee productivity, innovation, or job performance [14,15]. These divergent outcomes underscore the intricate and contextual nature of overtime effects.

Although prior research has advanced understanding of the health and work-related consequences of overtime, considerably less is known about its broader social ramifications-particularly the ways in which long working hours shape employees’ sense of social inclusion. This gap warrants attention in light of the increasing prominence of overtime work in contemporary contexts [16]. Addressing this limitation, the present study investigates the social implications of overtime work, thereby extending the current literature beyond health- and performance-related outcomes. In addition, the common view on overtime work is that it is counterproductive [5,17]. Existing empirical evidence supports this view, as overtime work has been linked to negative outcomes such as lower work performance [18]. In focusing primarily on the negative consequences of overtime work, scholars have largely overlooked the possibility that overtime work may have advantages. In particular, social inclusion, defined as the extent to which employees have informal social ties with others and feel as if they belong and are socially included by others in their life is an aspect of social interactions that is crucial to the social life of the individuals [19]. According to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, once individuals have satisfied their basic needs, they begin to seek social belonging and self-actualization. This theoretical perspective provides a valuable framework for understanding how employees perceive social inclusion in the workplace. In this paper, we explore the possibility that high-level overtime work enhances employees’ social inclusion.

Over the past 30 years, per capita labor hours have risen [20], suggesting a reduction in time available for social interaction, hence potentially diminishing individual social inclusion. Nonetheless, some scholars have posited that overtime work may confer advantages for social inclusion. Empirical evidence has suggested that individuals whose working hours are longer also have higher social communication [20,21]. Kikuch and his colleagues found that workers with 61–80 h of monthly overtime were more likely to feel vigorous than workers with shorter work hours [22]. Putnam demonstrated that employed individuals belong to more civic groups than individuals not in the labor force [23]. Kaasa and Parts found that employment positively affects participation in formal and informal networks [24]. Putnam proposed that employees who work long hours are inclined to engage in civic engagement [23]. Anecdotally, Jack Ma, founder of Alibaba, is known to have been an inveterate workaholic. He said that employees who work overtime at Alibaba could not only earn good income for themselves but also contribute to social development, such as promoting public welfare undertakings and improving social participation [25]. An adage states that what you lose on the swings, you get back on the roundabouts. Individuals who work extended hours may allocate less time to social activities after work, yet they engage more frequently with leaders and coworkers, enhancing their social inclusion within the community. While these scholarly speculations and anecdotal clues suggest that there may be conditions under which overtime work is conducive to social inclusion, this idea has yet to be theoretically developed or empirically tested. Concretely, we consider when overtime hours are relatively long, a rise in expected outcome social inclusion could occur.

In this study, we highlight work values as a key factor that shapes how employees interpret and respond to overtime work. Work values refer to individuals’ beliefs about the meaning, purpose, and desired attributes of work [26,27], and they influence how employees evaluate work experiences, allocate effort, and cope with job demands, including overtime. Cross-cultural research shows that work values differ significantly across countries. According to the World Values Survey (WVS), Chinese employees place greater emphasis on effort, responsibility, and long-term commitment, viewing work as both a social obligation and a pathway to self-realization, whereas employees in Western countries tend to prioritize personal autonomy, career choice, and work–life boundaries. Within Hofstede’s cultural dimensions framework, China’s high collectivism and high power distance make overtime more likely to be interpreted positively as a signal of dedication and commitment; in contrast, in low-collectivism, high-individualism societies such as the United States, the Netherlands, or the United Kingdom, overtime is more often perceived as organizational pressure or an intrusion into personal life. Moreover, the “social capital” dimension in the Legatum Prosperity Index (LPI) shows that social capital in China is more strongly based on familiar ties and emotional connections, whereas in Western societies it is rooted in institutional trust and weak-tie networks. This means that overtime in the Chinese context is more likely to be viewed as a process that strengthens interpersonal connections, rather than merely a source of strain.

These cultural distinctions suggest that overtime work is not interpreted uniformly across societies, and that employees’ work values play a crucial role in determining whether overtime is perceived as a burden or as a meaningful investment. Therefore, incorporating work values as a moderating variable enables us to capture individual differences in the relationship between overtime and social inclusion and provides a culturally grounded explanation for how overtime functions in the Chinese context.

In this paper, we develop new insights into the effect of overtime work on social inclusion and the boundary conditions that moderate this effect. Whereas some researchers have hinted at a linear effect, we propose that overtime work has a curvilinear, a U-shaped effect on social inclusion, and moderated by work values based on extended-self theory. Our theoretical perspective and empirical findings make important contributions to the literature on overtime work, social inclusion, and work values. First, most recent studies on overtime work were concentrated in developed countries [28], such as some European nations [29] and Japan [30]. Although there are significant differences between developed and developing countries in economic, social, and national systems, studies have rarely been carried out in developing countries. In addition, some studies have demonstrated that the work hours in developing countries were longer and that employees experienced more serious individual and sociological implications [31]. As a typical sizeable developing country, China has undergone a rapid and profound socio-economic change and has been one of the countries with long working hours in the world [32,33]. However, little is known about overtime and its influence in the Chinese context. Therefore, we attempt to understand the nature of overtime work in the Chinese context. This research question is not only economically relevant but also closely aligned with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Compared with developed economies such as France and Japan, China faces unique institutional and cultural challenges in achieving “Decent Work and Economic Growth” (SDG 8) and “Reduced Inequalities” (SDG 10). Therefore, examining the relationship between overtime work and social inclusion from a sustainability perspective contributes to a deeper understanding of how China’s labor practices are positioned within the broader global sustainable development framework.

Second, few empirical studies have tried to assess the social-related outcomes of overtime work to our best knowledge. A majority of studies have analyzed the effect of working overtime on individual health [13], family [11], and work-related outcomes [14]. However, the impact of overtime work on social-related consequences, such as social inclusion, exclusion, social interaction, and social status, has received little attention. Importantly, as the core of people’s social life, work hours is not only a necessary prerequisite for individual income but also an important factor that described current social inclusion [34,35]. It is necessary to probe the social implications of overtime to have a more comprehensive understanding of the nature of working hours. Therefore, this paper investigates how overtime impacts the individual perception of social inclusion to expand overtime research.

Third, most studies provide a direct and straightforward simple and relationship between overtime and their outcomes [36,37,38]. We demonstrate the curvilinear relationship between overtime work and social inclusion, thereby challenging the widespread assumption that overtime work is always counterproductive. In addition, exploring the potential mediators is a better way to understand the complexities of overtime work, and thus, it is necessary to explore the boundary conditions of the relationship between overtime work and social inclusion. The research fills this gap in the literature on overtime work by exploring the impact of work values on the relationship between overtime work and social inclusion.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: Section 2 introduces the theoretical framework and hypotheses; Section 3 explains the materials and methods; Section 4 reports the results; Section 5 discusses implications; Section 6 concludes the study, and Section 7 summarizes its limitations and suggests avenues for future research.

2. Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Theoretical Framework: Extended-Self Theory

Building on the extended-self theory, we argue that different levels of overtime work may lead to both positive and negative social outcomes [39,40,41]. The extended-self theory posits that persons are fundamentally motivated to expand their sense of self [40,42]. The extended-self theory emphasizes the fundamental role of personal possessions in understanding and defining an individual’s self (e.g., [39,40,43]). According to the extended-self theory, a job plays an important role in people’s lives [39,40,41]. When people have possessive feelings for their job, they may extend themselves to the job and consider them as parts of themselves. As a result, they strive to maintain, protect, and consolidate their possessive feelings for their job [43,44].

In addition, the extended-self theory holds that people personalize objects as their own or as parts of their extended self in different ways [39,40]. The object becomes an extension of the self when individuals (a) control the objects, (b) come to intimately know the objects (c) invest the self into the objects. To be specific, a long association with an object (e.g., long tenure) is likely to cause perceptions of knowing the object better, and, as a result, to a sense of possession [45]. Employees who work overtime devote a lot of time, energy, and effort to their jobs and know more about various aspects of jobs, so they feel the self is extended into the job. The more they invest themselves in the job, the more they feel that they extend themselves into the job, which triggers more action to maintain this sense of possession. We illustrate how overtime work leads to social inclusion in the following sections.

2.2. Overtime Work and Social Inclusion

Given individuals’ fundamental need to build and maintain social connections to sustain physical and mental health [46], people tend to engage in social interactions and gain social inclusion [47,48,49]. Social interaction is an important manifestation of individual social inclusion [50], which is crucial to individuals’ daily lives. The social interaction of employees includes the interaction within and outside the organization [51]. And the interaction inside the organization has more influence on the employees’ social inclusion because work hours are always viewed as the core of people’s social life [52].

Nowadays, the “996” work schedule, which refers to work from 9 am to 9 pm, six days a week has recently become a corporate culture in Chinese high-tech enterprises in first-tier cities [53]. In addition, engaging in social activities is an essential part of Chinese life because it not only reflects the degree of social inclusion perception but also creates social capital [20]. Employees without overtime work have leisure time such as weekends and holidays for interpersonal communication, including spending time with family, socializing with friends, participating in community activities, and recreation programs. It is an important social function for Chinese people to social communicate, refusing to participate may lead to grave consequences [54]. The individual’s time and energy are limited, and thus, an intuitively plausible notion holds that overtime work results in less time for practical social activities.

As stated above, we argue that working overtime is likely to cause employees to extend their selves into their work through three means: investing the self into the objects, coming to know the objects, controlling the objects. First, when the length of overtime work is relatively long, employees spend a lot of time and energy on their jobs. A feeling of possession generates owing to the perspective that objects are personalized as one person’s own and become a part of the extended self once we invest so many energies in these objects [39,40,55]. Second, people working longer hours come to know more about their jobs because the association between them and work is long. Overtime work increase employees’ interaction with their jobs and work roles, by which they understand their jobs profoundly and thoroughly. In this process, the job is extended to a part of the self [43]. Third, people who work overtime longer may have greater control over their work due to accumulated investment in their jobs. They can largely mastery their job resources, work progresses, and outcomes, and thus they extend the self to their work [39]. Consequently, employees with long working overtime are motivated to have behavioral responses, such as working hard, communicating with leaders and colleagues, helping coworkers, and maintaining and consolidating such feelings. Meanwhile, they have a higher level of interpersonal communication with leaders and colleagues and perceive a high level of social inclusion. In addition, those behaviors above could help persons to be understood and supported by their colleagues, further increasing their high-quality interactions with others [56,57,58]. Thus, we argue that a high level of overtime work can lead to positive social inclusion.

In contrast, employees may perceive the least social inclusion at intermediate levels of overtime hours. Time is a scarce resource, and employees must decide how to use their time [59]. Regardless of the length of overtime, the primary purpose of overtime is to complete the work task [60]. When the length of overtime is at intermediate levels, due to time and energy constraints, employees tend to focus on work tasks first while ignoring interpersonal communication in the organization. On account of time limitation, physical exhaustion and the need to accompany family members, meaningful social activities, and interpersonal communication of employees whose overtime hours are intermediate level are seldom available after work. That is, no matter during overtime or after work, those employees do not have enough time and energy to devote to various social activities. According to the extended-self theory, these employees spend less time and energy on work than employees who work overtime longer hours, so that they perceive the degree that the self is extended into the job is less, and they are less motivated to engage in interpersonal communication actively [39,55]. Compared with employees with longer overtime hours, and those without working overtime, employees with intermediate levels overtime perceive lower social inclusion. Accordingly, we hypothesize as follows:

Hypothesis 1.

The relationship between overtime work and social inclusion is U-shaped, such that the relationship between overtime work and social inclusion will be negative at the short overtime hours and become positive at long overtime hours.

2.3. Moderating Impact of Work Values

Values are regarded as deeply rooted motivations which guide and explain attitudes, standards, as well as behaviors [61]. A person’s values may be part of that individual’s self-concept [62] and influence how people evaluate multifarious events and their significance, and how they are motivated to take actions in different circumstances. Work is a significant domain in a human being’s activities. Work values determine what is of great importance for people in their work and what they want from their jobs [63]. Work values is defined as the desirable outcomes persons feel they should obtain through work [64] and divided into intrinsic and extrinsic values [65,66]. Extrinsic work values focus on tangible outcomes such as material possessions or rewards of work, such as job security and prestige. Intrinsic values, in contrast, focus on psychological rewards, like recognition, an interesting job, self-expression and self-actualization [67].

The extended-self framework suggests that the differentiating effects of overtime work depend on certain individual characteristics that influence individuals’ systematical interpretation of overtime work [43,68]. We follow this line of thought and further argue that work values moderate the U-shaped relationship between overtime work and social inclusion. Work values are personal values or beliefs that shape employees’ behaviors and attitudes and often remain relatively constant even in challenging situations such as overtime [69]. Employees with high work values believe that work is more meaningful and important to them [26]. Employees with high work values regard work as a means of self-realization [70], and they use overtime work or problems encountered during overtime work as a way to improve themselves. Thus, they still actively communicate with leaders and colleagues to solve problems and enhance cooperation when they work long hours, and the positive impact of overtime on social inclusion is reflected in them earlier.

Prior research proved that high levels of work values could be useful for improving both work engagement and burnout, even when employees work long hours [71]. That is, employees with high work values are more willing to spend more time and energy on their work and are full of vitality and do not easily feel tired when they work overtime. Moreover, work values are positively correlated with employees’ extra-role behavior, such as altruism, active communication and civic virtue [72,73,74]. Thus, employees with high work values are more inclined to help others and communicate with colleagues, which further increases their high-quality interactions with colleagues. Therefore, it is reasonable to believe that employees with high work values experience the positive impact of overtime work on social inclusion earlier.

Hypothesis 2.

Work values positively moderates the relationship between work overtime and social inclusion. Specifically, social inclusion increases earlier for high work values compared to low work values. Overtime work has a greater positive impact on social inclusion when employees have a high level of work values.

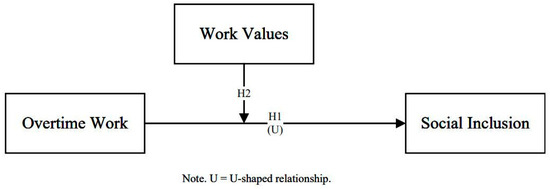

The research framework constructed in this paper is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Research framework. Source(s): Authors’ own work.

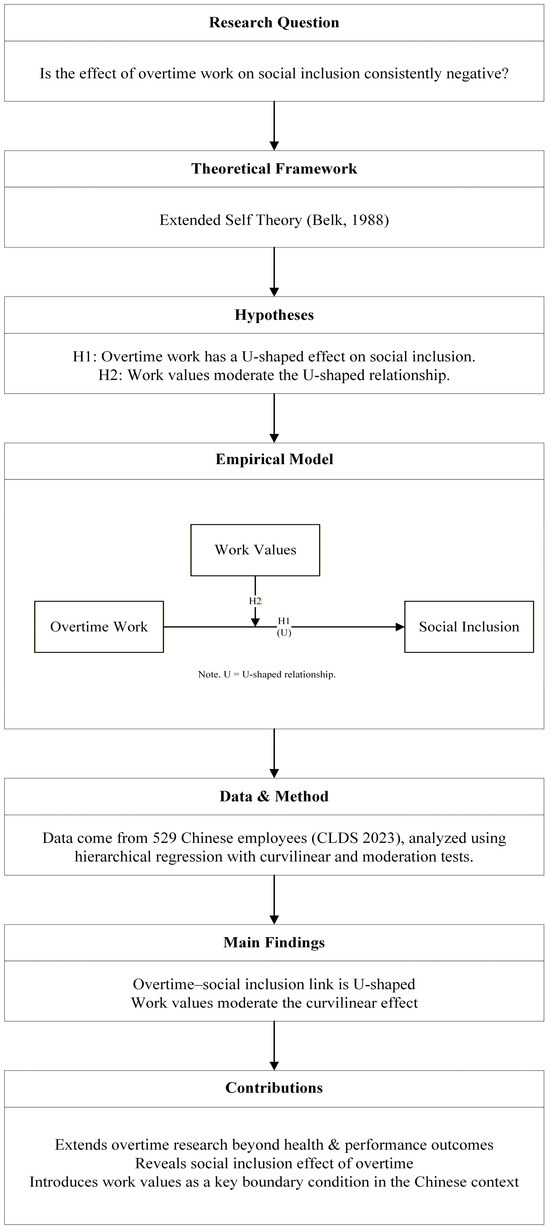

To provide readers with a clearer overview of the research logic, we present a flowchart summarizing the study design, key variables, hypotheses and core findings (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Flowchart of the Study [39,75]. Source(s): Authors’ own work.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Source and Description

The data from the China Labor-Force Dynamics Survey were used in this paper. By collecting and tracking the information of the individual, family and village in China, the China Labor-Force Dynamics Survey organized and implemented by the Center for Social Survey aims to systematically monitor the changes in the labor, family, and social structure. The project carries out a dynamic follow-up survey in 29 provinces and cities of China (except Hong Kong, Macau, Taiwan, Tibet, and Hainan) every two years, and the survey target is the entire labor force in the sample households (family members aged 15 to 64 years). The questionnaire is mainly divided into the individual labor force, family, and village residence, covering various topics such as education, health, work, immigration, social participation, and infrastructure. The data used in this paper is obtained from the 2016 individual labor survey. We accessed the anonymized 2016 wave of the China Labor-Force Dynamics Survey (CLDS) dataset for research purposes on 15 March 2023. The dataset is publicly available through the Center for Social Survey of Sun Yat-sen University [75]. All data were de-identified before being released to researchers, and the authors had no access to information that could identify individual participants during or after data collection.

The samples with missing values of these variables were deleted, according to the variables used in the study, and finally we got 529 valid samples. The mean age in our sample was 35.70 years old, and 57.8% were male. In terms of education, 56.9% had a high school degree or below, 23.6% had a college degree, 17.2% had a bachelor’s degree, and 2.3% had a graduate degree. Among the samples, 26.3% were unmarried. The average annual income was 56,023.15 CNY (≈8003 USD), converted using the 2023 official average exchange rate of 1 USD ≈ 7.0 CNY.

3.2. Measures

Overtime work. Overtime work was measured on the basis of overtime hours worked in the previous month.

Social inclusion. The questionnaire measures the social inclusion by the willingness to settle locally in the future. Adopting a five-point scale from 1 (very unlikely) to 5 (very likely), respondents rated the possibility of future settlement. The higher the score, the more likely people are to settle in the future.

Work value. Work value was assessed by the meaning or value of current work to people, which includes six items. Items are on a five-point scale, ranging from 1 (very inconsistent) to 5 (very consistent).

Control variables. Participants’ gender, age, marital status, residence type, and annual income were served as control variables in this paper. The description of those variables is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Definition and description of variables in the study.

3.3. Data Analysis Method and Model Estimation

To test our hypotheses, we need to specify and estimate the following general form regression models. First, we explain and test the possibility of non-linear (H1) in the relationship between overtime work (OWi) and social inclusion (Si) as follows:

where , in order to support non-linearity and the hypothesized U-shape relationship between OWi and Si (H1), the following conditions must hold: β1 < 0; β2 > 0.

Then, we test our second hypothesis for the role of work values (WVi) in moderating the relationship between overtime work and social inclusion. Taking the approach of Baron and Kenny as basis, we add the moderator variable (work values) to Equation (2) to test the moderating effect of work values, as follows:

where β are regression coefficients to be estimated, and the coefficients of the interaction terms are β4 and β5, respectively. H2 is supported if either β4 and/or β5 are statistically significant.

Equation (1) tests the linear and direct association between overtime work and social inclusion. Equation (2) tests the curvilinear relationship between overtime work and social inclusion (H1). Equation (3) tests the moderating effect of work values on overtime work and social inclusion (H2). When estimating the complete model represented by Equations (1)–(3), we adopted IBM SPSS Statistics (version 27) for hierarchical regression analysis and also included appropriate control variables. This method is widely used in management research to evaluate curvilinear relationships. Before being input into the regression model and calculating higher-order terms, the independent variables (overtime work) and work values variables were all standardised to avoid multicollinearity and to increase interpretability.

4. Results

Table 2 presents the means, standard deviations, correlations among variables. Based on the bivariate associations, overtime work is statistically significantly correlated to social inclusion.

Table 2.

Standard Deviations and Correlations Among Study Variables.

Hypothesis Testing

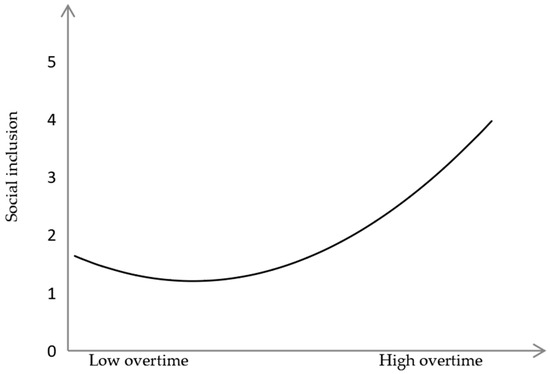

Hypothesis 1 signifies that the relationship between overtime work and social inclusion is U-shaped. Janssen’s 3-step procedure was used in this study [76]. First, we entered five control variables, namely, gender, age, marriage, living type, and annual income (Model 1). Second, overtime work was included (Model 2). Third, overtime-work squared was included (Model 3). The regression analysis results are shown in Table 3. The parameter estimates demonstrate that, as hypothesized, both β1 (β1 = −0.335, p < 0.01) and β2 (β2 = 0.248, p < 0.01) are statistically significant and satisfy the a priori U-shaped relationship condition, with β1 < 0 and β2 > 0 in the equations. The parameter estimate β1 and the quadratic term for overtime work β2 are both positive and statistically significant, which means that an increase in overtime work initially led to a decline in social inclusion then increased after reaching an inflexion point. Therefore, Hypothesis 1 is supported; namely, there is a U-shaped relationship between overtime work and social inclusion (see Figure 3). These results not only reveal a significant non-linear relationship between overtime work and social inclusion but also indicate that the impact of overtime work on employees’ social relationships varies at different stages. This finding aligns with the extended-self theory, which posits that individuals achieve self-extension and social connection through the investment of time and energy, providing new insights into the social significance of overtime behavior.

Table 3.

Hierarchical regression analysis for social inclusion.

Figure 3.

Curvilinear relationship between overtime work and social inclusion Source(s): Authors’ elaboration based on survey data.

To further illustrate the curvilinear relationship confirmed in Model 3, we plotted the predicted values of social inclusion at different levels of overtime work. As shown in Figure 3, the relationship follows a U-shaped pattern, in line with the coefficients reported in Table 3.

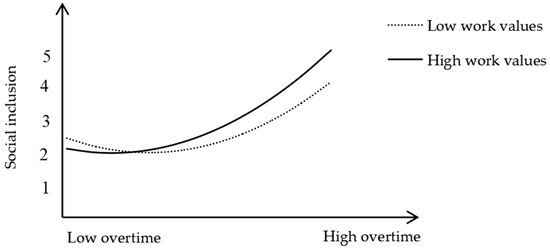

Hypothesis 2 predicts that work values moderates the curvilinear relationship between overtime work and social inclusion. In Model 5, work values, its interaction with overtime work and the product of work values and overtime work squared were all included. Table 3 summarises the parameter estimates related to the two interaction terms and (Equation (3)). The parameter estimate of β4 (β4 = 0.165, p < 0.05), the linear interaction term for overtime work and social inclusion, is statistically significant, while the parameter estimate of β5 (β5 = −0.074, ns), the squared interaction term, is not statistically significant, thus satisfying the condition for the moderation hypothesis. A further comparison of Equations (2) and (3) indicated that Equation (3) performed better with the change in R2 = 0.024. Therefore, Hypothesis 2 is supported. In order to clearly reveal the moderating role of work values on the U-shaped relationship between overtime work and social inclusion, we plotted the interaction in Figure 4, referring to the procedures outlined by Bauer and Curran [77].

Figure 4.

Moderating effects of work values on overtime work and social inclusion Source(s): Authors’ elaboration based on survey data.

As shown in Figure 4, we verified the moderating effect of work values, while overtime work and social inclusion have a non-monotonic relationship across work values; it can be seen that the inflexion point for high work values is reached at a lower level of overtime hours compared to the inflexion point for low work values. These results indicate that work values significantly moderate the relationship between overtime work and social inclusion. Employees with high work values tend to view overtime as an opportunity for self-realization and are therefore more likely to enhance themselves through communication and collaboration with colleagues during overtime work. Consequently, the positive effects of social inclusion manifest earlier among them. This finding highlights the crucial role of personal values in understanding the complexity of overtime behavior and aligns with the core assumptions of the extended-self theory.

5. Discussion

5.1. Key Findings and Contributions

Drawing on the extended-self theory, this study constructs and empirically validates a theoretical model that investigates the relationship between overtime work and social inclusion in the Chinese context, with a particular focus on the moderating effect of work values. Our results manifest that the impact of overtime work is not a simple linear relationship but is a U-shaped relationship between overtime work and employees’ social inclusion. This study changes the conventional and intuitively plausible notion holds that working overtime results in less social inclusion, developing the curvilinear association that the influence of overtime work on social inclusion declines initially but increases after reaching an inflexion point. In addition, we demonstrated that work values play a significant moderating role on the overtime work–social inclusion relationship. The findings provide strong empirical support for the extended-self theory and research on employee social inclusion, suggesting that overtime work is not merely a source of stress but a socio-psychological process with dual effects. Overall, this study reveals the interactive mechanism among overtime work, social inclusion, and work values, demonstrating that employees’ time investment, value identification, and relationship building are not independent processes, but rather mutually reinforcing components of a dynamic system. This offers a more context-specific explanation of overtime in the Chinese cultural setting and provides practical implications for organizations seeking to promote “decent work and employee well-being” (SDG 8).

Prior studies have presented conflicting findings regarding the effects of overtime work. On the one hand, a substantial body of research suggests that overtime work leads to negative outcomes, such as physical health problems, increased psychological strain, and higher levels of burnout [78]. On the other hand, another stream of research argues that overtime may generate positive outcomes, including enhanced job performance, career advancement, or higher income returns [79]. These divergent findings highlight the need for further investigation into the consequences of overtime work. Different from previous studies, the present research moves beyond the traditional “health–performance” dichotomy and shifts the focus to a social outcome of overtime work–employees’ sense of social inclusion. We argue that overtime is not only a physical or psychological burden but also a social process that shapes employees’ interactions and relationships within the organization [15]. By revealing how overtime work affects employees’ interpersonal relationships and their sense of inclusion, this study broadens the scope of overtime research. Instead of focusing only on outcomes related to performance or health, it highlights overtime as a social process that shapes employees’ relational and integration experiences. This perspective offers a new way of understanding overtime work and addresses the gap in existing studies that have largely overlooked its potential positive social outcomes.

The findings also confirm the moderating role of work values. Work values reflect individuals’ expectations, attitudes, and evaluative standards toward work, and serve as an important psychological foundation that shapes employee behavior, career choices, and perceptions of job satisfaction [80]. Employees with high work values tend to view work as meaningful [26] and are therefore more likely to invest effort during overtime, which in turn enhances their sense of social inclusion.

5.2. Cultural Context and Theoretical Extensions

Importantly, existing research on overtime work has been conducted predominantly in developed economies [28], such as several European countries [29] and Japan [30]. However, developed and developing countries differ markedly in terms of economic structures, institutional arrangements, and labor market conditions [81]. For this reason, the present study focuses on China. Compared with employees in Western countries and other advanced economies such as Japan, Chinese workers exhibit distinct work value orientations. First, under a collectivist cultural context, Chinese employees tend to view work as an expression of responsibility toward the family and society [82]. In contrast, employees in Western countries usually emphasize personal development and the importance of maintaining work–life boundaries [83]. Moreover, Chinese employees are more likely to endorse a long-term, effort-reward belief system, in which long working hours are interpreted as a sign of commitment, responsibility, and competitiveness [84]. In many European countries, however, excessive overtime is often regarded as a consequence of inefficient work systems or poor work–life balance [85]. Therefore, the differences in work values across countries lead to divergent attitudes toward overtime. In China, overtime is frequently viewed as a symbol of dedication and professional obligation, whereas in most Western societies, it is more commonly associated with work–life conflict and diminished well-being [86].

Moreover, employees’ understanding of overtime varies across countries, which can be attributed to differences in culture and social capital. Hofstede’s cultural dimensions provide an important framework for interpreting these variations [87]. In China, characterized by high collectivism, long-term orientation, and high power distance, overtime is often regarded as a sign of diligence and responsibility, as well as a way to gain organizational recognition and social respect [88]. In contrast, Western cultures emphasize individualism, low power distance, and a clear separation between work and personal life; therefore, overtime is more likely to be perceived as an intrusion into personal time rather than a sign of commitment [89]. From the perspective of social capital, China represents a relationship-oriented society in which trust and cooperation are largely built through strong interpersonal ties. Overtime work, by increasing interaction and collaboration among colleagues, tends to strengthen such relationships and enhance social capital. However, in Western societies, social capital is more institution-based and relies on weak-tie networks, meaning that overtime work does not substantially change interpersonal dynamics and thus has limited impact on employees’ sense of social inclusion.

Overall, by conceptualizing overtime work as a behavioral process with dual social and psychological effects, this study deepens both the theoretical and practical understanding of overtime phenomena. Theoretically, it extends the boundary of the extended-self theory within workplace contexts by revealing the relationship between employees’ time investment and social inclusion, while highlighting the critical moderating role of work values in this process. Practically, the findings remind organizational managers that overtime does not necessarily undermine employee well-being; rather, its effects depend on whether employees are provided with a sense of meaning and relational resources that allow them to perceive work as an extension of the self. In addition, this study offers actionable implications for promoting Decent Work and Employee Well-being (SDG 8) and Inclusive Social Relations (SDG 10), demonstrating that organizations can enhance employees’ social inclusion by optimizing overtime experiences through institutional design, cultural development, and value alignment.

5.3. Implications

5.3.1. Theoretical Implications

This study makes several theoretical contributions to the existing literature. First, we enrich previous studies on overtime work by exploring the curvilinear effect of overtime work on social inclusion. Most previous studies have focused either on the negative impact of overtime on health [12,13,90] or work-related results [15]. More recently, scholars have started to examine the consequences of working overtime on social-related outcomes [20,91]. However, our knowledge of the effects of working overtime on social-related outcomes is very limited, such as social interaction, relationship bonding, and sense of social belonging, and these areas are still under-researched. In this study, we establish a direct link between overtime work and social inclusion, breaking through the limitations of existing research which is confined to the perspectives of physical health or work performance, and introducing a new socio-psychological explanatory framework for overtime work research.

Second, our research challenges the dominant view of overtime work as an inherently counterproductive behavior. Although individuals may anticipate that overtime work can be costly [90], we find that a high level of overtime work can allow for frequent interpersonal interactions in the organization and promote individuals’ perception of social inclusion. In addition, based on the extended-self theory [39,55], we conceptualize overtime work as a form of self-investment in which individuals devote their time, emotions, and capabilities to their job. Our research adds to previous studies to form a more comprehensive extended self-based understanding of overtime work. Previous studies conducted within the extended-self framework have theoretically focused on the role of self-investment in influencing organizational outcomes while ignoring social implications [57,92,93]. By integrating overtime work into the process of perception of social inclusion, we contribute to the extended-self framework by extending the outcomes of self-extension to an important and specific concept: social inclusion. That is, the extended-self framework is not limited to exploring workplace outcomes but can also be used to investigate social-related psychological cognitive outcomes.

Third, previous overtime research rarely recognizes meaningful individual differences among employees. Our study explores the boundary conditions of overtime work on social inclusion, and our results find that work values positively moderates the curvilinear relationship between overtime work and social inclusion. Maslow arranged different human needs into a five-level hierarchy, starting from basic physiological needs followed by safety needs, belonging needs, esteem needs, and self-actualization needs [94]. And motivation links these needs with general behaviors. Employees with high work values believe that work can meet their more hierarchy needs [95]. These employees deem that work is not only a means of earning a living, but also meets their high-level hierarchy needs such as belonging needs, respect needs, and self-actualization needs [26]. As a result, they are more likely to engage in proactive behavior, including interpersonal communication when working overtime, feeling a high perception of social inclusion. When employees have a higher level of work values, the positive effect of overtime on social inclusion emerges earlier, as reflected in an earlier inflection point in the curve. In short, as a relatively stable personality trait [27], work values serve as a key moderator in the relationship between overtime work and social inclusion, functioning as an important psychological variable for predicting the effects of overtime. By identifying this moderating mechanism, the present study addresses a gap in prior research that has largely focused on the direct outcomes of overtime while neglecting individual differences, thereby offering a more nuanced understanding of the complexity of overtime behavior.

5.3.2. Practical Implications

Our findings indicate a curvilinear (U-shaped) relationship between overtime and employees’ social inclusion: very low or very high overtime can be counterproductive, whereas moderate, well-managed overtime can strengthen ties with colleagues and heighten embeddedness in the workplace community. For cities in China that are competing to attract and retain talent [96], this nuance suggests that standards should favor reasonable flexibility rather than blanket tightening or loosening [97]. Policymakers can set guardrails to prevent excessive overtime while acknowledging that moderate, time-bounded peaks-paired with recovery time-may promote healthy social connection [96]. At the organizational level, firms can concentrate unavoidable overtime into short, team-based sprints with deliberate social touchpoints (e.g., pre-briefs/retrospectives and peer recognition), explicitly recognize overtime with time-off in lieu or bonuses [97,98], and decouple recognition for results from sheer hours worked to avoid normalizing overwork. Employees, in turn, should be encouraged to view selective, time-limited overtime as an opportunity to broaden informal networks, provided that recovery practices (protected rest days, predictable scheduling) are clearly enforced.

Because the curvilinear effect is moderated by employees’ work values, managers should avoid one-size-fits-all approaches to scheduling, communication, and rewards. Employees with higher work values tend to experience the positive social effects of overtime earlier and remain engaged in interpersonal interaction even when hours are long [71]; brief diagnostics (surveys and check-ins) can inform differentiated overtime thresholds, rotation plans, and recovery windows across value profiles. Embedding the corporate mission in everyday routines (onboarding, town halls, team rituals) can elevate perceived work meaning, amplifying inclusion benefits of moderate overtime without pressuring others to overextend [99]. Recognition systems should highlight collaborative and relational contributions during peak periods (mentoring, knowledge sharing) rather than raw hours, while safeguards-such as red lines on maximum consecutive overtime days and guaranteed decompression periods—help keep overtime within the productive zone of the U-shape.

6. Conclusions

This study aims to examine whether and how overtime work affects employees’ sense of social inclusion and further investigates the moderating role of work values in this relationship. Unlike previous research, which has primarily focused on the effects of overtime on outcomes such as health and performance, this study shifts the lens toward social inclusion-an important yet long-neglected sociopsychological outcome. In doing so, it responds to the core theoretical debate over whether overtime work should be understood solely as a negative experience. Overtime is not only a problem faced by enterprises, but also a topic of the general concern in society. Our findings show that the relationship between overtime and social integration is not linear but rather exhibits a significant U-shaped effect. Longer overtime hours may help improve employees’ sense of social inclusion, while shorter overtime hours may reduce their sense of social inclusion. We challenge the conventional view that overtime always negatively influences employees and provides a new insight into overtime work through the U-shaped influence of overtime on social inclusion. In addition, we found that work values play a key moderating role in this process. Employees with higher work values are more likely to view overtime as an opportunity for self-investment and self-realization and therefore, experience the positive effects of overtime on social inclusion earlier. In contrast, employees with lower work values are less likely to gain positive social feedback from overtime work. We hope that these findings deepen the understanding of overtime beyond its traditional framing as merely a labor or scheduling issue and instead highlight its role as a social mechanism that shapes employees’ relational experiences and societal embeddedness.

At the theoretical level, this study incorporates overtime work into the analytical framework of the extended-self theory, revealing the psychological mechanism through which time investment influences employees’ social relationships. This provides a new theoretical perspective for understanding the complex link between working hours and social outcomes and lays a foundation for future research on the social-cognitive consequences of work behavior.

At the practical level, the findings offer useful implications for multiple stakeholders. For organizational managers, the results indicate that the effects of overtime are not uniformly negative; rather, its positive outcomes depend on the alignment between employees’ work values and organizational support. Thus, organizations may optimize employees’ overtime experience through value communication, team interaction design, and culture shaping. For policy makers, the study suggests that labor policies should move beyond simply controlling working hours and also focus on enhancing the quality of work experience and the availability of social connection resources, thereby promoting both fair employment and social integration. For employees, the results highlight the role of work values in shaping the subjective experience of overtime, offering insights for career choice, value orientation, and self-regulation in demanding work environments.

Overall, this study provides a new lens for organizational management, human resource practices, and labor policy design, helping to promote work systems that are more human-centered and socially integrative.

7. Research Limitations and Future Research Directions

Despite the theoretical and practical contributions of this study, several limitations remain, which also open up promising directions for future research. First, the cross-sectional design is adopted in the study to explore the relationship between overtime work and social inclusion. Although the empirical results have been consistent with the theoretical hypothesis, future research could adopt longitudinal research designs, such as time-series analysis or cross-lagged panel models, to further examine the dynamic evolution of the relationship between overtime work and social inclusion, thereby enhancing the explanatory power and robustness of the findings.

Nevertheless, this single item method has been used and tested in previous studies, and these studies have reported strong reliability and validity. Future studies may consider employing more fine-grained or multidimensional measurement tools, such as well-validated scales for social inclusion and work values, to improve the reliability and validity of variable measurement and further verify the robustness of the proposed model.

Third, this study only investigates the moderating role of work values in the relationship between overtime work and social inclusion. To achieve a more comprehensive understanding of how overtime work shapes employees’ social cognition, future research may incorporate boundary conditions at multiple levels, such as employees’ emotional states or motivational orientations, organizational contextual factors, and job characteristics. This would help reveal how the mechanisms through which overtime exerts its influence may vary across different conditions and enhance the applicability of the findings.

Overall, future research that further advances the study design, refines variable measurement, and incorporates broader contextual boundary conditions will help develop a more comprehensive understanding of how overtime work shapes employees’ social cognition and social connectedness.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.Y. and J.X.; methodology, C.Y. and J.X.; software, J.X.; validation, J.X.; formal analysis, J.X.; investigation, C.Y. and J.X.; resources, C.Y.; data curation, J.X.; writing—original draft preparation, J.X.; writing—review and editing, C.Y.; visualization, C.Y.; supervision, C.Y.; project administration, C.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. The data are accessible from the Science Data Bank (ScienceDB): China Labor-Force Dynamics Survey (CLDS), 2016 individual labor-force data at https://doi.org/10.57760/sciencedb.02333 (CSTR: 31253.11.sciencedb.02333). No new data were created or collected for this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Niedhammer, I.; Pineau, E.; Bertrais, S. Employment factors associated with long working hours in France. Saf. Health Work 2023, 14, 483–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estevão, M.M.; Sá, F. The 35-hour workweek in France: Straightjacket or welfare improvement? Econ. Policy 2008, 23, 418–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özcan, K.M.; Üçdoğruk Birecikli, Ş.; Ünlü, M.; Öktem Özgür, A. Economic and demographic determinants of overtime in the Turkish private sector. Int. J. Work. Cond. 2021, 22, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Labour Organization; Committee of Experts on the Application of Conventions and Recommendations. General Survey Concerning Working-Time Instruments: Ensuring Decent Working Time for the Future; Report III (Part B), 107th Session, International Labour Conference; International Labour Office: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; ISBN 978-92-2-128674-5. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/publications/general-survey-concerning-working-time-instruments-ensuring-decent-working (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- Kuwahara, K.; Minoura, A.; Shimada, Y.; Kawai, Y.; Fukushima, H.; Kondo, M.; Sugiyama, T. Work hours, appraisal at work, and intention to leave the medical research workforce in Japan. J. Occup. Health 2025, 67, uiaf044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. National Time Use Survey Bulletin; China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2019. (In Chinese)

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China. China’s National Plan on Implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. 2016. Available online: https://www.greenpolicyplatform.org/national-documents/chinas-national-plan-implementation-2030-agenda-sustainable-development (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- Bannai, A.; Tamakoshi, A. The association between long working hours and health: A systematic review of epidemiological evidence. Scand. J. Work. Environ. Health 2014, 40, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckers, D.G.; van der Linden, D.; Smulders, P.G.; Kompier, M.A.; Taris, T.W.; Geurts, S.A. Voluntary or involuntary? Control over overtime and rewards for overtime in relation to fatigue and work satisfaction. Work Stress 2008, 22, 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontinha, R.; Easton, S.; Van Laar, D. Overtime and quality of working life in academics and nonacademics: The role of perceived work-life balance. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2019, 26, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, Y.Y.; Bai, C.H.; Yang, C.M.; Huang, Y.C.; Lin, T.T.; Lin, C.H. Long hours’ effects on work-life balance and satisfaction. Biomed. Res. Int. 2019, 2019, 5046934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virtanen, M.; Kivimäki, M. Long working hours and risk of cardiovascular disease. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 2018, 20, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, K.; Chan, A.H.; Ngan, S.C. The effect of long working hours and overtime on occupational health: A meta-analysis of evidence from 1998 to 2018. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bei, L.; Hong, C.; Xin, G. How much is too much? The influence of work hours on social development: An empirical analysis for OECD countries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, Y.J.; Choi, J.N. Overtime work as the antecedent of employee satisfaction, firm productivity, and innovation. J. Organ. Behav. 2019, 40, 282–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hino, A.; Inoue, A.; Mafune, K.; Hiro, H. The effect of changes in overtime work hours on depressive symptoms among Japanese white-collar workers: A 2-year follow-up study. J. Occup. Health 2019, 61, 320–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, C.C. Negative impacts of shiftwork and long work hours. Rehabil. Nurs. 2014, 39, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, R.J. Working to live or living to work: Should individuals and organizations care? J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 84, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, J.L.; Randel, A.E. Expectations of organizational mobility, workplace social inclusion, and employee job performance. J. Organ. Behav. 2004, 25, 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saffer, H.; Lamiraud, K. The effect of hours of work on social interaction. Rev. Econ. Househ. 2012, 10, 237–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolin, K.; Lindgren, B.; Lindström, M.; Nystedt, P. Investments in social capital—Implications of social interactions for the production of health. Soc. Sci. Med. 2003, 56, 2379–2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikuchi, H.; Odagiri, Y.; Ohya, Y.; Nakanishi, Y.; Shimomitsu, T.; Theorell, T.; Inoue, S. Association of overtime work hours with various stress responses in 59,021 Japanese workers: Retrospective cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0229506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Putnam, R.D. Bowling alone: America’s declining social capital. J. Democr. 1995, 6, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaasa, A.; Parts, E. Individual-level determinants of social capital in Europe: Differences between country groups. Acta Sociol. 2008, 51, 145–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jack Ma: It’s a Blessing to Work 996. Available online: https://m.sohu.com/a/307487736_115565 (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- Elizur, D.; Borg, I.; Hunt, R.; Beck, I.M. The structure of work values: A cross-cultural comparison. J. Organ. Behav. 1991, 12, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ros, M.; Schwartz, S.H.; Surkiss, S. Basic individual values, work values, and the meaning of work. Appl. Psychol. Int. Rev. 1999, 48, 49–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bei, L.; Hong, C.; Xinru, H. Map changes and theme evolution in work hours: A co-word analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piasna, A. Scheduled to work hard: The relationship between non-standard working hours and work intensity among European workers (2005–2015). Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2018, 28, 167–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujiwara, T.; Shimazu, A.; Tokita, M.; Shimada, K.; Takahashi, M.; Watai, I.; Iwata, N.; Kawakami, N. Association between parental workaholism and body mass index of offspring: A prospective study among Japanese dual workers. Front. Public Health 2016, 4, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner-Hartl, V.; Kallus, K.W. Investigation of psychophysiological and subjective effects of long working hours: Do age and hearing impairment matter? Front. Psychol. 2018, 8, 2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jingyi, C. Research review on overtime issues. Mod. Manag. 2018, 8, 387–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mucci, N.; Traversini, V.; Giorgi, G.; Tommasi, E.; De Sio, S.; Arcangeli, G. Migrant workers and psychological health: A systematic review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, P.; Yang, C. Examining the effects of overtime work on subjective social status and social inclusion in the Chinese context. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngai, L.R.; Pissarides, C.A. Trends in hours and economic growth. Rev. Econ. Dyn. 2008, 11, 239–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collewet, M.; Sauermann, J. Working hours and productivity. Labour Econ. 2017, 47, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cygan-Rehm, K.; Wunder, C. Do working hours affect health? Evidence from statutory workweek regulations in Germany. Labour Econ. 2018, 53, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, N.C.; Chen, J.D.; Cheng, T.J. The associations between long working hours, physical inactivity, and burnout. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2016, 58, 514–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belk, R.W. Possessions and the extended self. J. Consum. Res. 1988, 15, 139–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belk, R.W. Are we what we have? In I Shop Therefore I Am: Compulsive Spending and the Search for Self; Benson, A., Ed.; Jason Aronson Press: Northvale, NJ, USA, 2000; pp. 76–104. [Google Scholar]

- Dittmar, H. The Social Psychology of Material Possessions: To Have Is to Be; Harvester Wheatsheaf: Hemel Hempstead, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Mattingly, B.A.; McIntyre, K.P.; Lewandowski, G.W., Jr. Approach motivation and the expansion of self in close relationships. Pers. Relatsh. 2012, 19, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, J.L.; Kostova, T.; Dirks, K.T. The state of psychological ownership: Integrating and extending a century of research. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2003, 7, 84–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richins, M.L. Valuing things: The public and private meanings of possessions. J. Consum. Res. 1994, 21, 504–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, J.L.; Kostova, T.; Dirks, K.T. Toward a theory of psychological ownership in organizations. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 298–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R.F.; Leary, M.R. The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychol. Bull. 1995, 117, 497–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, N.L.; Levine, J.M. The detection of social exclusion: Evolution and beyond. Group Dyn. Theory Res. Pract. 2008, 12, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesselmann, E.D.; Butler, F.A.; Williams, K.D.; Pickett, C.L. Adding injury to insult: Unexpected rejection leads to more aggressive responses. Aggress. Behav. 2010, 36, 232–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wesselmann, E.D.; Wirth, J.H.; Pryor, J.B.; Reeder, G.D.; Williams, K.D. When do we ostracize? Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2013, 4, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litwiller, F.; White, C.; Gallant, K.A.; Gilbert, R.; Hutchinson, S.; Hamilton-Hinch, B.; Lauckner, H.; Fenton, L. The benefits of recreation for the recovery and social inclusion of individuals with mental illness: An integrative review. Leis. Sci. 2017, 39, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, J.W.; Brass, D.J. Social interaction and the perception of job characteristics in an organization. Hum. Relat. 1985, 38, 571–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Chen, H.; Yang, X.; Hou, C. Why work overtime? A systematic review on the evolutionary trend and influencing factors of work hours in China. Front. Public Health 2019, 7, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, C.; Silva, E.A.; Zhang, C. Nine-nine-six work system and people’s movement patterns: Using big data sets to analyse overtime working in Shanghai. Land Use Policy 2020, 90, 104340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, A.V.; Duflo, E. The economic lives of the poor. J. Econ. Perspect. 2007, 21, 141–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belk, R.W. (Ed.) Possessions and the sense of past. In Highways and Buyways: Naturalistic Research from the Consumer Behavior Odyssey; Association for Consumer Research: Provo, UT, USA, 1991; pp. 114–130. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, A.M.; Berg, J.M.; Cable, D.M. Job titles as identity badges: How self-reflective titles can reduce emotional exhaustion. Acad. Manag. J. 2014, 57, 1201–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, W.A. Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Acad. Manag. J. 1990, 33, 692–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swann, W.B., Jr.; Polzer, J.T.; Seyle, D.C.; Ko, S.J. Finding value in diversity: Verification of personal and social self-views in diverse groups. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2004, 29, 9–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, A.M.; Dolis, C.M. Something’s got to give: The effects of dual-goal difficulty, goal progress, and expectancies on resource allocation. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 678–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proctor, S.P.; White, R.F.; Robins, T.G.; Echeverria, D.; Rocskay, A.Z. Effect of overtime work on cognitive function in automotive workers. Scand. J. Work. Environ. Health 1996, 22, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, S.H. A theory of cultural values and some implications for work. Appl. Psychol. Int. Rev. 1999, 48, 23–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verplanken, B. Value congruence and job satisfaction among nurses: A human relations perspective. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2004, 41, 599–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warr, P. Work values: Some demographic and cultural correlates. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2008, 81, 751–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagie, A.; Elizur, D.; Koslowsky, M. Work values: A theoretical overview and a model of their effects. J. Organ. Behav. 1996, 17, 503–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twenge, J.M.; Campbell, S.M.; Hoffman, B.J.; Lance, C.E. Generational differences in work values: Leisure and extrinsic values increasing, social and intrinsic values decreasing. J. Manag. 2010, 36, 1117–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreitzer, G.M.; Porath, C.L. Self-determination as nutriment for thriving: Building an integrative model of human growth at work. In The Oxford Handbook of Work Engagement, Motivation, and Self-Determination Theory; Gagné, M., Ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 245–254. [Google Scholar]

- Dirks, K.T.; Cummings, L.L.; Pierce, J.L. Psychological ownership in organizations: Conditions under which individuals promote and resist change. In Research in Organizational Change and Development; Woodman, R.W., Pasmore, W.A., Eds.; JAI Press: Greenwich, CT, USA, 1996; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, J.; Rounds, J. Stability and change in work values: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 80, 326–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martela, F.; Pessi, A.B. Significant work is about self-realization and broader purpose: Defining the key dimensions of meaningful work. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, Y.; Igarashi, A.; Noguchi-Watanabe, M.; Takai, Y.; Yamamoto-Mitani, N. Work values and their association with burnout/work engagement among nurses in long-term care hospitals. J. Nurs. Manag. 2018, 26, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.H.V.; Kao, R.H. Work values and service-oriented organizational citizenship behaviors: The mediation of psychological contract and professional commitment: A case of students in Taiwan Police College. Soc. Indic. Res. 2012, 107, 149–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaževič, N.; Seljak, J.; Aristovnik, A. Occupational values, work climate and demographic characteristics as determinants of job satisfaction in policing. Police Pract. Res. 2019, 20, 376–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vansteenkiste, M.; Neyrinck, B.; Niemiec, C.P.; Soenens, B.; De Witte, H.; Van den Broeck, A. On the relations among work value orientations, psychological need satisfaction and job outcomes: A self-determination theory approach. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2007, 80, 251–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Center for Social Survey of Sun Yat-sen University. China Labor-force Dynamic Survey. Sci. Data Bank 2023, CSTR: 31253.11.sciencedb.02333. [CrossRef]

- Janssen, O. Fairness perceptions as a moderator in the curvilinear relationships between job demands, and job performance and job satisfaction. Acad. Manag. J. 2001, 44, 1039–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, D.J.; Curran, P.J. Probing interactions in fixed and multilevel regression: Inferential and graphical techniques. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2005, 40, 373–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckers, D.G.J.; van der Linden, D.; Smulders, P.G.T.; Kompier, M.A.J.; van Veldhoven, M.J.P.; van Yperen, N.W. Working overtime hours: Relations with fatigue, work motivation, and the quality of work. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2004, 46, 1282–1289. [Google Scholar]

- Golden, L.; Wiens-Tuers, B. Overtime work and wellbeing at home. Rev. Soc. Econ. 2008, 66, 25–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalleberg, A.L. Work values and job rewards: A theory of job satisfaction. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1977, 42, 124–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.B. Labor Markets and Institutions in Economic Development. Am. Econ. Rev. 1993, 83, 403–408. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2117698 (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- Hofstede, G. Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions, and Organizations Across Nations, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Inglehart, R.; Baker, W.E. Modernization, cultural change, and the persistence of traditional values. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2000, 65, 19–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Iddekinge, C.H.; Arnold, J.D.; Aguinis, H.; Lang, J.W.B.; Lievens, F. Work effort: A conceptual and meta-analytic review. J. Manag. 2023, 49, 125–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anttila, T.; Oinas, T.; Tammelin, M.; Nätti, J. Working-time regimes and work-life balance in Europe. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 2015, 31, 713–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Chen, L.; Bi, X. Overtime work, job autonomy, and employees’ subjective well-being: Evidence from China. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1077177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, F. National cultural differences in theory and practice: Evaluating Hofstede’s national cultural framework. Inf. Technol. People 1997, 10, 132–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, R.S.; Haytko, D.L.; Hermans, C.M. Individualism and collectivism: Reconsidering old assumptions. J. Int. Bus. Res. 2009, 8, 127–136. [Google Scholar]

- Lomas, T.; Diego-Rosell, P.; Shiba, K.; Standridge, P.; Lee, M.T.; Case, B.; VanderWeele, T.J. Complexifying individualism versus collectivism and West versus East: Exploring global diversity in perspectives on self and other in the Gallup World Poll. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2023, 54, 61–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artazcoz, L.; Cortès, I.; Benavides, F.G.; Escribà-Agüir, V.; Bartoll, X.; Vargas, H.; Borrell, C. Long working hours and health in Europe: Gender and welfare state differences in a context of economic crisis. Health Place 2016, 40, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arlinghaus, A.; Bohle, P.; Iskra-Golec, I.; Jansen, N.; Jay, S.; Rotenberg, L. Working Time Society consensus statements: Ev-idence-based effects of shift work and non-standard working hours on workers, family and community. Ind. Health 2019, 57, 184–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, W.A. To be fully there: Psychological presence at work. Hum. Relat. 1992, 45, 321–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rich, B.L.; Lepine, J.A.; Crawford, E.R. Job engagement: Antecedents and effects on job performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2010, 53, 617–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahba, M.A.; Bridwell, L.G. Maslow reconsidered: A review of research on the need hierarchy theory. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1976, 15, 212–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basinska, B.A.; Dåderman, A.M. Work values of police officers and their relationship with job burnout and work engagement. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z. Economic migration and urban citizenship in China: The role of points systems. Popul. Dev. Rev. 2012, 38, 503–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trejo, S.J. The effects of overtime pay regulation on worker compensation. Am. Econ. Rev. 1991, 81, 719–740. [Google Scholar]

- Crampton, S.M.; Hodge, J.W.; Mishra, J.M. The FLSA and overtime pay. Public Pers. Manag. 2003, 32, 331–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinjerski, V.; Skrypnek, B.J. Creating organizational conditions that foster employee spirit at work. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2006, 27, 280–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).