Forecasting Electronic Waste Using a Jaya-Optimized Discrete Trigonometric Grey Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

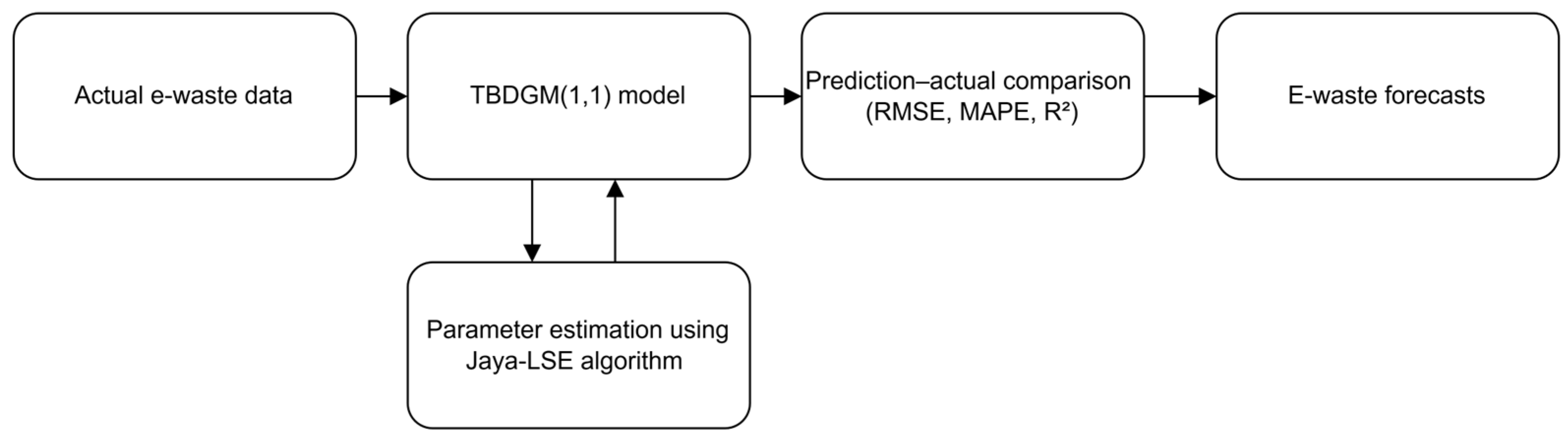

3. Materials and Methods

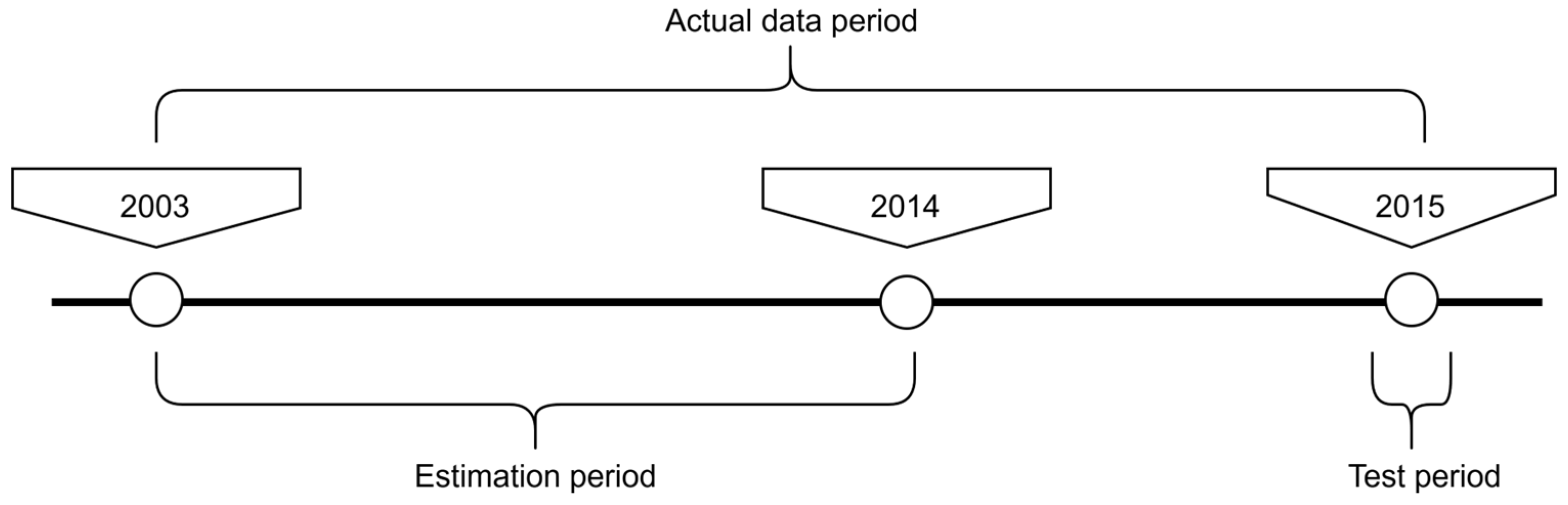

3.1. System Boundary

3.2. The Proposed TBDGM(1,1) Model

3.3. Parameter Estimation

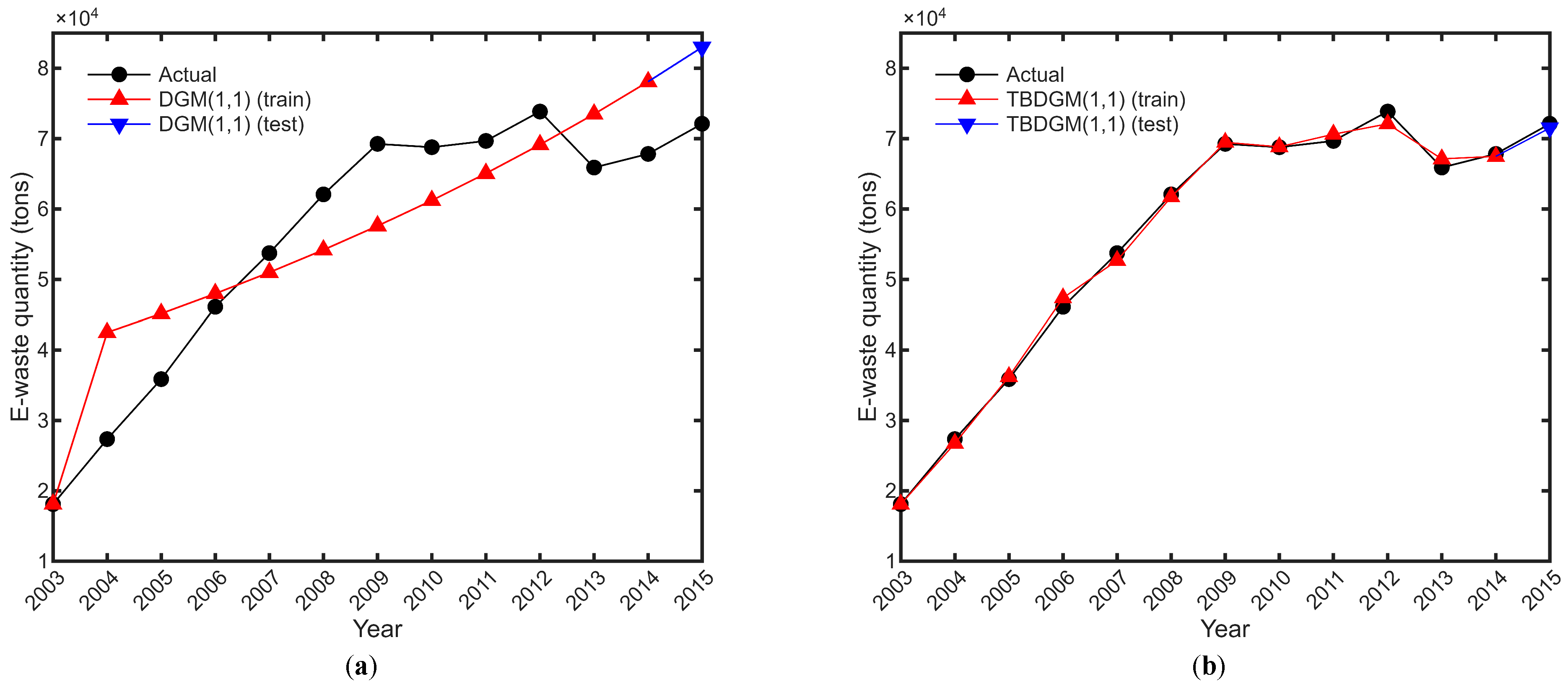

4. The Performance Validation of TBDGM(1,1)

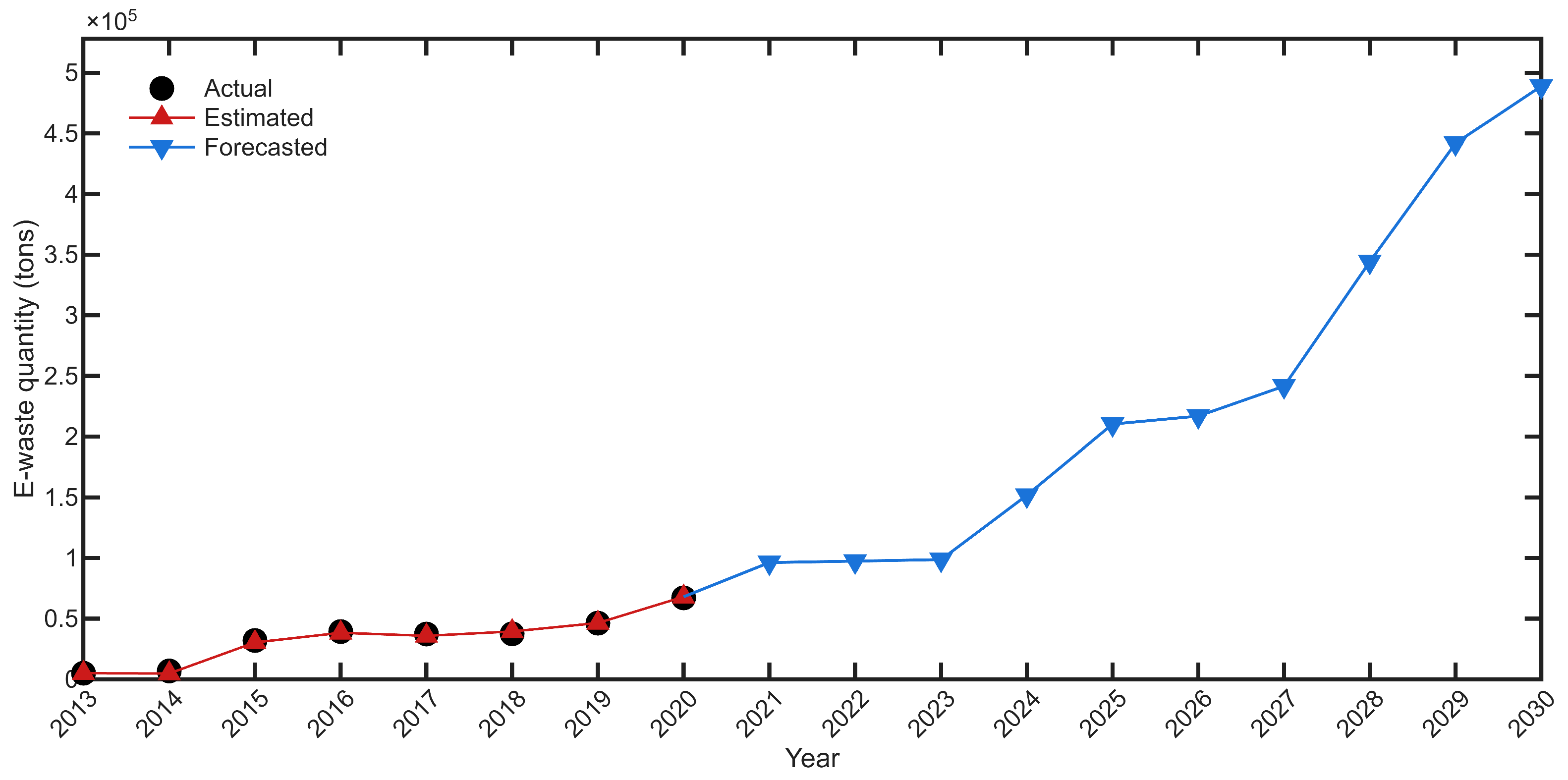

5. E-Waste Estimation and Forecasting for the Türkiye Case with TBDGM(1,1)

6. Conclusions and Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Grey Model | Equation |

|---|---|

| DGM(1,1) | x(1)(k + 1) = β1 x(1)(k) + β2 |

| NDGM(1,1) | x(1)(k + 1) = β1 x(1)(k) + β2 k + β3 |

| TDGM(1,1) | x(1)(k + 1) = (β1 + β2 k) x(1)(k) + β3 k + β4 |

| QDGM(1,1) | x(1)(k + 1) = (β1 + β2 k + β3 k2) x(1)(k) + β4 k2 + β5 k + β6 |

| CDGM(1,1) | x(1)(k + 1) = (β1 + β2 k + β3 k2 + β4 k3) x(1)(k) + β5 k3 + β6 k2 + β7 k + β8 |

References

- UNITAR. The Global E-Waste Monitor 2024-Electronic Waste Rising Five Times Faster Than Documented E-Waste Recycling; UNITAR: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, W.J.; Williams, P.T. Separation and recovery of materials from scrap printed circuit boards. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2007, 51, 691–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buekens, A.; Yang, J. Recycling of WEEE plastics: A review. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2014, 16, 415–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamawaki, T. The gasification recycling technology of plastics WEEE containing brominated flame retardants. Fire Mater. 2003, 27, 315–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forti, V.; Balde, C.P.; Kuehr, R.; Bel, G. The Global E-Waste Monitor 2020: Quantities, Flows and the Circular Economy Potential; 9280891146; United Nations University (UNU)/United Nations Institute for Training and Research (UNITAR): Bonn, Germany; International Telecommunication Union (ITU): Geneva, Switzerland; International Solid Waste Association (ISWA): Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- ÇŞBTC, Ministry of Environment and Urbanization. Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment Control Regulation; Ministry of Environment and Urbanization: Ankara, Turkey, 2012. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar]

- T.C. Sanayi ve Teknoloji Bakanlığı, Ministry of Industry and Technology. Ankara Province Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment Recycling Facility Pre-Feasibility Report; Ministry of Industry and Technology: Ankara, Turkey, 2021. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar]

- Baldé, C.P.; Iattoni, G.; Xu, C.; Yamamoto, T. Update of WEEE Collection Rates, Targets, Flows, and Hoarding–2021 in the EU-27, United Kingdom, Norway, Switzerland, and Iceland; SCYCLE Programme, United Nations Institute for Training and Research (UNITAR): Bonn, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan-Fogarty, Y.; Coughlan, D.; Fitzpatrick, C. Quantifying WEEE arising in scrap metal collections: Method development and application in Ireland. J. Ind. Ecol. 2021, 25, 1021–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akpulat, O. Atığın Ötesinde; Vodafone: Düsseldorf, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Abbondanza, M.; Souza, R. Estimating the generation of household e-waste in municipalities using primary data from surveys: A case study of Sao Jose dos Campos, Brazil. Waste Manag. 2019, 85, 374–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovea, M.D.; Ibanez-Fores, V.; Perez-Belis, V.; Juan, P. A survey on consumers’ attitude towards storing and end of life strategies of small information and communication technology devices in Spain. Waste Manag. 2018, 71, 589–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petridis, K.; Petridis, N.; Stiakakis, E.; Dey, P. Investigating the factors that affect the time of maximum rejection rate of e-waste using survival analysis. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2017, 108, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petridis, N.E.; Petridis, K.; Stiakakis, E. Global e-waste trade network analysis. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 158, 104742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duman, G.M.; Kongar, E. ESG Modeling and Prediction Uncertainty of Electronic Waste. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duman, G.M.; Kongar, E.; Gupta, S.M. Estimation of electronic waste using optimized multivariate grey models. Waste Manag. 2019, 95, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.; Yu, L.; Wu, A. Forecasting the electronic waste quantity with a decomposition-ensemble approach. Waste Manag. 2021, 120, 828–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikhlayel, M. Differences of methods to estimate generation of waste electrical and electronic equipment for developing countries: Jordan as a case study. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2016, 108, 134–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.; Sareen, R. E-waste assessment methodology and validation in India. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2006, 8, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Shrihari, S. Estimation and material flow analysis of waste electrical and electronic equipment (WEEE)—A case study of Mangalore City, Karnataka, India. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Sustainable Solid Waste Management, Chennai, India, 5–7 September 2007; pp. 5–7. [Google Scholar]

- Streicher-Porte, M.; Widmer, R.; Jain, A.; Bader, H.-P.; Scheidegger, R.; Kytzia, S. Key drivers of the e-waste recycling system: Assessing and modelling e-waste processing in the informal sector in Delhi. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2005, 25, 472–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Huisman, J.; Stevels, A.; Balde, C.P. Enhancing e-waste estimates: Improving data quality by multivariate Input-Output Analysis. Waste Manag. 2013, 33, 2397–2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oguchi, M.; Kameya, T.; Yagi, S.; Urano, K. Product flow analysis of various consumer durables in Japan. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2008, 52, 463–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakthivel, U.; Swaminathan, G.; Anis, J. Strategies for Quantifying Metal Recovery from Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment (WEEE/E-waste) Using Mathematical Approach. Process Integr. Optim. Sustain. 2022, 6, 781–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasaki, T.; Takasuga, T.; Osako, M.; Sakai, S. Substance flow analysis of brominated flame retardants and related compounds in waste TV sets in Japan. Waste Manag. 2004, 24, 571–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazici, B.; Can, Z.S.; Calli, B. Prediction of future disposal of end-of-life refrigerators containing CFC-11. Waste Manag. 2014, 34, 162–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Gu, Y.; Tang, A.; Li, B.; Li, B.; Pan, D.; Wu, Y. Forecast of future yield for printed circuit board resin waste generated from major household electrical and electronic equipment in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 283, 124575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peralta, G.L.; Fontanos, P.M. E-waste issues and measures in the Philippines. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2006, 8, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, M.G.; Magrini, A.; Mahler, C.F.; Bilitewski, B. A model for estimation of potential generation of waste electrical and electronic equipment in Brazil. Waste Manag. 2012, 32, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Yang, J.; Lu, B.; Song, X. Estimation of retired mobile phones generation in China: A comparative study on methodology. Waste Manag. 2015, 35, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonda, L.; D’Ans, P.; Degrez, M. A comparative assessment of WEEE collection in an urban and rural context: Case study on desktop computers in Belgium. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 142, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztürk, T. Generation and management of electrical–electronic waste (e-waste) in Turkey. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2014, 17, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Liu, Y.; Feng, K.; Chen, W.-Q. Spatiotemporal dynamics of city-level WEEE generation from different sources in China. Front. Eng. Manag. 2024, 11, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanegas, P.; Peeters, J.R.; Cattrysse, D.; Dewulf, W.; Duflou, J.R. Improvement potential of today’s WEEE recycling performance: The case of LCD TVs in Belgium. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 2017, 11, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.T.; Huda, N. E-waste in Australia: Generation estimation and untapped material recovery and revenue potential. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 237, 117787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosai, S.; Kishita, Y.; Yamasue, E. Estimation of the metal flow of WEEE in Vietnam considering lifespan transition. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 154, 104621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Ali, S.H.; Li, J. Estimation of waste outflows for multiple product types in China from 2010–2050. Sci. Data 2021, 8, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastanaki, E.; Giannis, A. Forecasting quantities of critical raw materials in obsolete feature and smart phones in Greece: A path to circular economy. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 307, 114566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedy, M.; Mittal, R.K. Estimation of future outflows of e-waste in India. Waste Manag. 2010, 30, 483–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, H.P.; Schaubroeck, T.; Nguyen, D.Q.; Ha, V.H.; Huynh, T.H.; Dewulf, J. Material flow analysis for management of waste TVs from households in urban areas of Vietnam. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 139, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; You, X.; Li, X.; Liu, G. Watch more, waste more? A stock-driven dynamic material flow analysis of metals and plastics in TV sets in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 187, 730–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozsut Bogar, Z.; Gungor, A. Forecasting Waste Mobile Phone (WMP) Quantity and Evaluating the Potential Contribution to the Circular Economy: A Case Study of Turkey. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju-Long, D. Control problems of grey systems. Syst. Control Lett. 1982, 1, 288–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayacan, E.; Ulutas, B.; Kaynak, O. Grey system theory-based models in time series prediction. Expert Syst. Appl. 2010, 37, 1784–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydemir, E.; Bedir, F.; Özdemir, G. Gri Sistem Teorisi Ve Uygulamalari: Bilimsel Yazin Taramasi. Süleyman Demirel Üniversitesi İktisadi Ve İdari Bilim. Fakültesi Derg. 2013, 18, 187–200. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Y.; Liu, Y.; Chen, J.; Dong, Y.; Qu, B. Forecasting industrial emissions: A monetary approach vs. a physical approach. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 2012, 6, 734–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, N.-m.; Liu, S.-f. Discrete grey forecasting model and its optimization. Appl. Math. Model. 2009, 33, 1173–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, N.; Liu, S. Discrete GM (1, 1) and mechanism of grey forecasting model. Syst. Eng.-Theory Pract. 2005, 25, 93–99. [Google Scholar]

- He, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, X.; Wu, W.; Zhang, L. A novel structure adaptive new information priority discrete grey prediction model and its application in renewable energy generation forecasting. Appl. Energy 2022, 325, 119854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Liu, S. Linear time-varying parameters discrete grey forecasting model. Syst. Eng.-Theory Pract. 2010, 30, 1650–1657. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, N.-M.; Liu, S.-F.; Yang, Y.-J.; Yuan, C.-Q. On novel grey forecasting model based on non-homogeneous index sequence. Appl. Math. Model. 2013, 37, 5059–5068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Wu, Z.; Li, Y.; Yu, J. Grey discrete parameters model and its application. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics (SMC), Taiyuan, China, 4–6 June 2014; pp. 2050–2054. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, S.; Liu, S.; Liu, Z.; Fang, Z. Cubic time-varying parameters discrete grey forecasting model and its properties. Control Decis. 2016, 31, 279–286. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, P.; Ang, B.; Poh, K.L. A trigonometric grey prediction approach to forecasting electricity demand. Energy 2006, 31, 2839–2847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuzemen, A. Trigonometric Grey Prediction Method for Turkey’s Electricity Consumption Prediction. In Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Operations Management and Service Evaluation; IGI Global Scientific Publishing: Hershey, PA, USA, 2021; pp. 136–154. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Liu, S.; Yan, H. The application of trigonometric grey prediction model to average per capita natural gas consumption of households in China. Grey Syst. Theory Appl. 2019, 9, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajesh, R. Predicting environmental sustainability performances of firms using trigonometric grey prediction model. Environ. Dev. 2023, 45, 100830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comert, G.; Begashaw, N.; Huynh, N. Improved grey system models for predicting traffic parameters. Expert Syst. Appl. 2021, 177, 114972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, H.; Luo, X. A novel multivariable grey prediction model and its application in forecasting coal consumption. ISA Trans. 2022, 120, 110–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Liu, S.; Yang, Y.; Fang, Z.; Xu, S. A recursive polynomial grey prediction model with adaptive structure and its application. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 249, 123629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kothari, P.L.; Ahluwalia, P.; Nema, A.K. A grey system approach for forecasting disposable computer waste quantities: A case study of Delhi. Int. J. Bus. Contin. Risk Manag. 2011, 2, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Zhao, C.; Yu, L.; Li, G.; Huang, J.; Zhu, H.; He, W. Prediction and Analysis of WEEE in China Based on the Gray Model. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2016, 31, 925–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Duman, G.M.; Kongar, E.; Gupta, S.M. Predictive analysis of electronic waste for reverse logistics operations: A comparison of improved univariate grey models. Soft Comput. 2020, 24, 15747–15762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, S.; Kang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xiao, X.; Zhu, H. Fractional grey model based on non-singular exponential kernel and its application in the prediction of electronic waste precious metal content. ISA Trans. 2020, 107, 12–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiran, M.; Shanmugam, P.V.; Mishra, A.; Mehendale, A.; Sherin, H.N. A multivariate discrete grey model for estimating the waste from mobile phones, televisions, and personal computers in India. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 293, 126185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Zhong, Z. Assessing WEEE sustainability potential with a hybrid customer-centric forecasting framework. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 27, 1918–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazancoglu, Y.; Ozbiltekin, M.; Ozen, Y.D.O.; Sagnak, M. A proposed sustainable and digital collection and classification center model to manage e-waste in emerging economies. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2020, 34, 267–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; He, Y.-q.; Feng, Y. Analysis and prediction on carbon emissions from electrical and electronic equipment industry in China. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2024, 106, 107539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Liao, Q.; Xu, H. Anticipating future photovoltaic waste generation in China: Navigating challenges and exploring prospective recycling solutions. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2024, 106, 107516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, H.; Kumar, H. Precising E-Waste Generation for Economic Recycling. Indian Econ. J. 2024, 73, 717–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, B.; Song, X.; Zhuang, X.; Wu, W.; Li, A. Generation and resource potential of waste PV modules considering technological iteration: A case study in China. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2025, 112, 107790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, X.; Cao, J.; Ba, J.; Zhang, M. Transition and Trajectory of Spatiotemporal Characterization of Waste Photovoltaics in China: 2013–2060. Renew. Energy 2025, 249, 123214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duman, G.M.; Kongar, E. A novel Hausdorff fractional grey Bernoulli model and its Application in forecasting electronic waste. Waste Manag. Bull. 2025, 3, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloomfield, P. Fourier Analysis of Time Series: An Introduction; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Shumway, R.H.; Stoffer, D.S. Time Series Analysis and Its Applications: With R Examples; Springer: New York, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Gan, M.; Chen, C.P.; Chen, G.-Y.; Chen, L. On some separated algorithms for separable nonlinear least squares problems. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2017, 48, 2866–2874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLoone, S.; Brown, M.D.; Irwin, G.; Lightbody, A. A hybrid linear/nonlinear training algorithm for feedforward neural networks. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. 1998, 9, 669–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, M.; Malik, T.N.; Ahmed, A.; Nadeem, M.F.; Khan, I.A.; Bo, R. A novel hybrid GWO-LS estimator for harmonic estimation problem in time varying noisy environment. Energies 2021, 14, 2587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettayeb, M.; Qidwai, U. A hybrid least squares-GA-based algorithm for harmonic estimation. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2003, 18, 377–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogar, E. Chaos game optimization-least squares algorithm for photovoltaic parameter estimation. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2023, 48, 6321–6340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Thieu, N.; Nguyen, N.H.; Sherif, M.; El-Shafie, A.; Ahmed, A.N. Integrated metaheuristic algorithms with extreme learning machine models for river streamflow prediction. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 13597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, R. Jaya: A simple and new optimization algorithm for solving constrained and unconstrained optimization problems. Int. J. Ind. Eng. Comput. 2016, 7, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diab, A.A.Z.; Tolba, M.A.; El-Magd, A.G.A.; Zaky, M.M.; El-Rifaie, A.M. Fuel cell parameters estimation via marine predators and political optimizers. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 166998–167018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duman, G.M.; Kongar, E.; Upadhyaya, K. Forecasting foreign direct investment using optimized Hausdorff fractional multivariate grey Bernoulli model. J. Financ. Econ. Policy 2025, 17, 836–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javidsharifi, M.; Pourroshanfekr Arabani, H.; Kerekes, T.; Sera, D.; Guerrero, J.M. Stochastic optimal strategy for power management in interconnected multi-microgrid systems. Electronics 2022, 11, 1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chicco, D.; Warrens, M.J.; Jurman, G. The coefficient of determination R-squared is more informative than SMAPE, MAE, MAPE, MSE and RMSE in regression analysis evaluation. Peerj Comput. Sci. 2021, 7, e623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.-N.; Wang, C.-N. The integrated approach for sustainable performance evaluation in value chain of Vietnam textile and apparel industry. Sustainability 2017, 9, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, C.D. International and Business Forecasting Methods; Butterworths: London, UK, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, W.-Z.; Jiang, J.; Li, Q. A novel discrete grey model and its application. Math. Probl. Eng. 2019, 2019, 9623878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, X.; Cui, W. Estimation of the Student Employment in the Aviation Industry Based on Novel Fractional Error Accumulation Grey Model. J. Math. 2022, 2022, 7738447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ÇŞBTC. Ministry of Environment and Urbanization. Waste Statistics Bulletin (In Turkish). 2020. Available online: https://webdosya.csb.gov.tr/db/ced/icerikler/2020-yili-atik-istat-st-kler--bulten--rev-ze12012023-20230112135036.pdf (accessed on 25 January 2023).

| Study | Method | Region | Product | GM Type | Rolling | Train Period | Test Period | Projection Period | Main Focuses and Highlights |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kothari et al. [61] | GM and Grey Relational Analysis | India/ Delhi | PC | GM(1,1) | N/A | 2000–2004 | N/A | 2005–2020 | The study identifies personal computer penetration rate, population, GDP, and gross national income per capita using grey relational analysis, with a generalized regression neural network employed for forecasting. |

| Zhao et al. [62] | GM and Grey Relational Analysis | China | Refrigerator, washing machine, air conditioner, PC | GM(1,1) | N/A | 2001–2013 | N/A | 2014–2031 | Grey models are used to predict the quantity of household appliances in China. The real estate market is shown to have a high correlation with household appliance ownership through grey relational analysis. |

| Duman et al. [16] | Multi-variate GM | USA/WA | General | NBGMC(1,N) | N/A | 2003–2014 | 2015 | 2016–2017 2018–2030 | Inputs include population density and median household income. Nonlinear grey Bernoulli model enhanced with PSO. |

| Duman et al. [63] | Improved Univariate GM | USA/WA | General | PSO-NNGBMFO(1,1) PSO—SAIGMFO(1,1) | Yes | 2003–2014 | 2015 | 2016–2023 | Takes into account e-waste recycling and disposal rates. The model is optimized using PSO. |

| Mao et al. [64] | Fractional Derivative Model with Exponential Kernel Function | China | The weight of printed circuit boards (PCBs) from mobile phone, laptop, desktop and television waste | EFGM(q,1) | N/A | 2006–2015 | 2016 | 2017–2025 | Predicts precious metal content in electronic waste. |

| Kiran et al. [65] | Multi-variate Discrete GM | India | Mobile phone, TV, PC | EFDGM(1,N) | N/A | 1998- 2007 PC 2007–2016 TV 2009–2017 Mobile phone | - | 2018–2030 | Inputs include GDP and urban/rural population. GM is used to estimate the amount of products in use. Fourier transform and exponential smoothing are combined to reduce periodic and stochastic errors. |

| Wang et al. [17] | Decomposition-based GM | USA/WA and United Kingdom | General for WA large household appliances (LHA) and cooling appliances containing refrigerants (CAR) | GVM, GWFM | N/A | 2003–2014 | 2015 | 2016–2025 | Integrated variable mode decomposition, exponential smoothing model, and grey modelling methods are used. |

| Guo and Zhong [66] | Grey Relational Analysis (GRA), Principal Component Analysis (PCA), and Kernel GM | Taiwan and Vietnam | TV, washing machine, air conditioner, refrigerator | KGM(1,N) | N/A | 1998–2015 | 2016–2020 | 2021–2030 | Explores the influence of customer behaviour on collection and generation of e-waste. |

| Kazancoglu et al. [67] | GM | Türkiye | General | GM(1,1) | N/A | 2013–2018 | N/A | 2019–2021 | Forecasting of collected e-waste. |

| Duman and Kongar [15] | GM Enhanced by PSO | Türkiye | Mobile phone | NBGMFO(1,1) | N/A | 2001–2020 | N/A | 2021–2035 | Introduces a novel forecasting method, integrating Fourier residual modification. |

| Wang et al. [68] | Carbon Emissions Prediction from WEEE | China | General | GM(1,1) | N/A | 2012–2020 | N/A | 2021–2030 | Forecasts the carbon footprint for developing a comprehensive life cycle management system to minimize the environmental impact of the EEE industry. |

| Wang et al. [69] | Neural Network Model, GM, Regression Analysis, And Time Series Method | China | PV modules | GM(1,1) | N/A | 2008–2022 | N/A | 2023–2050 | Compares four methods for forecasting PV installations PV waste estimation based on installation forecasts |

| Sharma and Kumar [70] | GM | India | General | GM(1,1) | N/A | 2017–2021 | N/A | 2022–2026 | To assess future quantities of e-waste in India |

| Wang et al. [71] | Grey Verhulst model | China | PV modules | GVM(1,1) | N/A | 2000–2022 | N/A | 2023–2050 | To project the future growth of PV module installations over an extended period |

| An et al. [72] | GM, Weibull Distribution Market Supply A | 31 provinces in China | PV modules | GM(1,1) | N/A | 2013–2022 | N/A | 2023–2030 | GM employed to project photovoltaic installed capacity |

| Duman and Kongar [73] | Hausdorff Fractional Grey Bernoulli Model | USA/Connecticut State and United Kingdom | Covered Electronic Devices and Consumer Equipments | HNBGM(r,1) | N/A | 2011–2023 2008–2023 | 2024–2030 | Optimized Hausdorff fractional grey Bernoulli model is utilized to predict waste of covered electronic devices in Connecticut and United Kingdom | |

| This study | Trigonometry-Based Discrete GM | USA/WA and Türkiye | General | TBDGM(1,1) | N/A | 2013–2017 2013–2018 | 2018–2020 2019–2020 | 2021–2030 | Trigonometric GM with Jaya algorithm, validated in USA and Türkiye, showing cross-context adaptability and dual-layer benchmarking. |

| Year | E-Waste (tons) | Year | E-Waste (tons) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2003 | 18,108.186 | 2010 | 68,777.911 |

| 2004 | 27,341.564 | 2011 | 69,673.018 |

| 2005 | 35,877.901 | 2012 | 73,851.238 |

| 2006 | 46,126.412 | 2013 | 65,894.784 |

| 2007 | 53,737.509 | 2014 | 67,822.933 |

| 2008 | 62,071.464 | 2015 | 72,103.408 |

| 2009 | 69,246.269 |

| State-of-the-Art Discrete Grey Models | E-Waste Estimation Literature | This Study | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training/Test | Metric | DGM(1,1) | NDGM(1,1) | TDGM(1,1) | QDGM(1,1) | CDGM(1,1) | GMC(1,3) * | NBGMC(1,3)-PSO * | VMD-DESM-GWFM ** | VMD-GVM-DESM-GWFM ** | TBDGM(1,1) |

| Training (2003–2014) | MAPE | 14.2109 | 5.0193 | 2.4817 | 2.0314 | 1.9571 | 2.9900 | 1.8000 | 3.0700 | 1.6000 | 1.1577 |

| R2 | 0.7964 | 0.9715 | 0.9905 | 0.9914 | 0.9912 | 0.9800 | 0.9922 | 0.9906 | 0.9963 | 0.9976 | |

| RMSE | 8101.49 | 3032.91 | 1748.63 | 1668.30 | 1688.25 | 2539.91 | 1586.52 | 1837.57 | 1114.79 | 873.49 | |

| Test (2015) | MAPE | 15.0923 | 0.3736 | 13.7875 | 14.1280 | 16.1070 | 7.8424 | 0.3273 | N/A | 4.2554 | 0.2851 |

| RMSE | 10,882.06 | 269.38 | 9941.25 | 10,786.80 | 11,613.67 | 5654.61 | 236.02 | N/A | 3068.28 | 205.56 | |

| Training/Test | Metric | DGM(1,1) | NDGM(1,1) | TDGM(1,1) | QDGM(1,1) | CDGM(1,1) | TBDGM(1,1) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Analysis I | Training (2013–2018) | MAPE | 47.1729 | 2.4811 | 1.6016 | 332.0687 | 4467.6458 | 0.0003 |

| R2 | 0.7102 | 0.9951 | 0.9979 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 1.0000 | ||

| RMSE | 7889.3499 | 1029.4661 | 678.1759 | 143,523.5215 | 3,231,864.8089 | 0.1122 | ||

| Test (2019–2020) | MAPE | 10.1427 | 30.4128 | 37.1860 | 2047.9055 | 378,147.0455 | 14.8868 | |

| RMSE | 6579.9276 | 21,295.7370 | 25,126.6669 | 1317,180.7013 | 310,201,362.7180 | 11,515.2912 | ||

| Training/Test | Metric | DGM(1,1) | NDGM(1,1) | TDGM(1,1) | QDGM(1,1) | CDGM(1,1) | TBDGM(1,1) | |

| Analysis II | Training (2013–2019) | MAPE | 41.494 | 4.577 | 5.008 | 0.000 | 2149.421 | 0.025 |

| R2 | 0.767 | 0.969 | 0.979 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 | ||

| RMSE | 7375.010 | 2695.405 | 2209.412 | 0.000 | 1,105,557.057 | 7.746 | ||

| Test (2020) | MAPE | 16.900 | 39.633 | 31.323 | 3.927 | 1285.466 | 4.607 | |

| RMSE | 11,348.524 | 4.577 | 21,034.587 | 2637.377 | 863,229.064 | 3093.488 |

| Parameter | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | 1.225 | 19,430.395 | −5928.096 | 22,322.761 | 1.777 | 1.507 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ozsut Bogar, Z.; Duman, G.M.; Gungor, A.; Kongar, E. Forecasting Electronic Waste Using a Jaya-Optimized Discrete Trigonometric Grey Model. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10073. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210073

Ozsut Bogar Z, Duman GM, Gungor A, Kongar E. Forecasting Electronic Waste Using a Jaya-Optimized Discrete Trigonometric Grey Model. Sustainability. 2025; 17(22):10073. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210073

Chicago/Turabian StyleOzsut Bogar, Zeynep, Gazi Murat Duman, Askiner Gungor, and Elif Kongar. 2025. "Forecasting Electronic Waste Using a Jaya-Optimized Discrete Trigonometric Grey Model" Sustainability 17, no. 22: 10073. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210073

APA StyleOzsut Bogar, Z., Duman, G. M., Gungor, A., & Kongar, E. (2025). Forecasting Electronic Waste Using a Jaya-Optimized Discrete Trigonometric Grey Model. Sustainability, 17(22), 10073. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210073