Abstract

Buckwheat (Fagopyrum esculentum) and lupins (Lupinus spp.) are traditional crops gaining renewed attention due to their nutritional value, ecological adaptability, and potential role in sustainable agriculture. Both are rich in high-quality proteins, essential amino acids, and bioactive compounds that support human health and meet the growing demand for plant-based foods. In addition to their nutritional importance, these crops can be cultivated on marginal soils with low fertilizer requirements, making them valuable components of climate-resilient cropping systems. Beyond nutrition, both crops generate processing by-products such as husks and ashes, which are increasingly important in the context of fertilizers, bioenergy, and biomaterials, illustrating the dual value of these crops in sustainable and circular systems. This review summarizes data on cultivation, yield, and chemical composition and highlights the multiple pathways for by-product valorisation across food, energy, and environmental applications, contributing to the development of bio-based and circular economy strategies.

1. Introduction

Global population growth, urbanization, and changing dietary habits are putting increasing pressure on the agricultural sector. By 2050, the world population is expected to reach almost 10 billion, requiring an increase in food production of about 70% to meet the growing demand [1,2]. These changes are inseparable from the expansion of cropland, projected to increase by 70–110% compared to current levels. Mineral fertilizers remain one of the most important factors ensuring agricultural productivity, but their excessive use is associated with soil degradation, the eutrophication of water bodies, greenhouse gas emissions, and the accumulation of heavy metals [3]. These challenges increasingly highlight the need for sustainable solutions such as organic fertilizers, biofertilizers, bio stimulants, biochar, and other alternatives that can improve soil health, reduce dependence on mineral fertilizers, and comply with the principles of the circular economy [4].

Alongside soil and fertilizer management, the selection of crops that combine agronomic efficiency, ecological resilience, and nutritional value has become a crucial direction in sustainable agriculture. Lupins (Lupinus spp.) and buckwheat (Fagopyrum esculentum) stand out as species with high potential to contribute to sustainable food systems, soil health, and circular resource use. Lupins are distinguished by their high protein content and the diversity of bioactive compounds, making them promising plant-based protein sources [5]. Buckwheat, a nutritionally dense pseudo cereal, is valued for its antioxidants, flavonoids, minerals, dietary fibber, and gluten-free nature, supporting both healthy diets and the development of functional foods [6,7]. Its bioactive compounds (particularly rutin and quercetin) provide antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anticancer properties, enhancing its contribution to human health.

Beyond their nutritional value, both crops contribute to recycling and circular economy practices. Lupins can be used as food, feed, and sources of protein isolates, as well as industrial raw materials. Buckwheat has a similarly wide range of applications—from traditional grain products and beverages to pharmaceutical and industrial uses, including the valorisation of by-products such as husks and stems for bioenergy, fillers, and biomaterials [8]. Such applications enhance the economic value of these plants, reduce waste streams, and align with the principles of a circular economy.

While many crops, such as buckwheat, are valued for their ecological adaptability, certain lupin species pose environmental risks when introduced beyond their native ranges. The large-leaved lupin (Lupinus polyphyllus) is one of the most widespread invasive plants in Europe, including Lithuania. It forms dense stands that suppress native vegetation, alter soil chemistry by increasing nitrogen levels, and affect soil microbial communities and invertebrate habitats [9]. Although this species is drought- and frost-tolerant, with seeds that remain viable for many years, its spread can cause biodiversity loss and ecosystem imbalance [10,11].

Despite these ecological risks, lupins also provide clear agronomic benefits. In Lithuania, bitter cultivars with high alkaloid content and fodder lupins are cultivated as “green” fertilizers (side rates) that fix atmospheric nitrogen, accumulate it in roots and biomass, and improve soil fertility [12,13]. The most common cultivated species in Europe (Lupinus albus, L. angustifolius, and L. luteus) are valued for their high-protein seeds and adaptability to various climates [14]. This dual nature (high agronomic potential but ecological risk in certain regions) illustrates the complexity of integrating lupins into sustainable farming systems.

In contrast, buckwheat demonstrates an environmentally safe and highly adaptable profile. Its rapid growth, short vegetation period, and low nutrient requirements allow its cultivation on marginal lands and under low-input conditions. Buckwheat supports biodiversity by providing nectar for pollinators, suppressing weeds, and reducing soil erosion. It improves soil structure and acts as an effective catch crop in organic rotations [15,16]. Moreover, its role in the circular bioeconomy is expanding through the use of by-products for compost, bioenergy, and biochar, contributing to resource efficiency and climate change mitigation.

In Lithuania, buckwheat cultivation is mainly concentrated in the southern and south-eastern regions, especially in Dzūkija, where the light, well-drained sandy loam soils characterised by low fertility provide suitable conditions for its growth, although the crop remains sensitive to soil compaction and moisture deficits. In recent decades, the buckwheat area has expanded nearly five-fold, although yield improvements have remained modest due to suboptimal agrotechnical practices and weed competition, which may reduce yields by up to 50%. Typical sowing rates are about 80 kg ha−1, with an average yield ranging from 0.8 to 1.5 t ha−1, depending on climatic conditions [17]. The crop’s role is important as a resilient and regionally significant species in Lithuania’s sustainable farming systems, especially for low-productivity soils [18,19].

The comparison between Lupinus polyphyllus and Fagopyrum esculentum highlights two contrasting yet complementary examples within sustainable agriculture. Lupins represent the challenges of balancing ecological risk with agronomic potential, while buckwheat exemplifies resilience, multifunctionality, and environmental compatibility. This article-review analyses both species in terms of cultivation, chemical composition, processing, and utilization, with particular attention to their roles in soil fertility improvement, healthy diets, and the circular economy. The discussion aims to identify how these crops can contribute to the development of low-input, biodiversity-friendly, and resource-efficient agroecosystems.

Unlike previous reviews that focused on the nutritional and feed value of lupins [5,20,21] or buckwheat [22,23,24], this article presents a comparative and integrated synthesis that links both crops in a unified framework of sustainability and circular economy. The novelty of this review is in combining agronomic, chemical, and value-adding perspectives to show how these species can together contribute to low-cost, bio-based, and resource-recycling agricultural systems in Europe. Lupins enrich the soil by fixing nitrogen and provide protein-rich biomass, while buckwheat mobilizes phosphorus and supports biodiversity on poor soils—together providing a complementary model for sustainable crop diversification. In addition to their primary use as food and feed, the cultivation of these legumes generates by-products suitable for the production of fertilizers, bioenergy, and biomaterials, demonstrating the potential to close nutrient and material cycles. Although waste value enhancement is often only addressed in experimental studies, comprehensive reviews integrating food, energy, and fertilizer pathways are still lacking. Therefore, this work fills an important gap by offering a holistic view of the management and use efficiency of the biomass resources of lupins and buckwheat, which are important for agriculture in central and northern Europe for the development of a circular bioeconomy in European agroecosystems.

The literature for this review was collected through a structured search of major scientific databases such as Scopus, Web of Science, ScienceDirect, MDPI, and Google Scholar. The search covered the period from 2000 to 2025 to find both review and research studies related to lupins (Lupinus) and buckwheat (Fagopyrum esculentum). The main keywords and their combinations comprised lupins, straw, buckwheat, hulls (husks), invasion, chemical composition, nutrients, production, processing, circular economy, biomass reuse, bioenergy, biofuels, fertilizers, and sustainability. Scientific articles in peer-reviewed journals written in English were preferred, addressing agronomic, chemical, nutritional, or value-adding aspects of lupins and buckwheat. FAO data were very important in order to assess the dynamics of the areas and the yields of cereals and buckwheat in different countries of the world. However, it is regrettable that, since 2021, not all countries feel obliged to submit data to the FAO. For this reason, it was necessary to use national sources, review articles, and online articles intended for the general public to fill the gaps in statistical data. In total, 382 records were found during the search, but after selecting by year, removing duplicates, and reviewing titles and abstracts, the relevance of 152 articles was assessed. Of these, 103 were included in the final synthesis.

2. Lupinus Recycling for Sustainable Development

2.1. Distribution of Lupins in the World and in Lithuania

Lupins (Lupinus spp.) are members of the legume family Fabaceae, comprising more than 199 species distributed across diverse ecological zones. The centres of diversity are located in North and South America, with smaller centres in the Mediterranean region and north Africa. These species are widely cultivated both as food and ornamental plants, but several of them (particularly Lupinus polyphyllus) have become invasive in parts of Europe, North America, and Oceania [25]. Lupins grow in habitats ranging from relatively dry to humid environments and tolerate soils of moderate to high acidity, which facilitates their naturalization in areas far beyond their native ranges.

In Europe, Lupinus angustifolius has become increasingly popular due to its better disease resistance and reliable harvest timing, especially in central and northern regions. L. albus, L. luteus, and L. angustifolius are grown across the continent, with breeding programmes in Poland, Germany, Ukraine, Belarus, and Russia making L. angustifolius the dominant species. Europe also leads in terms of incorporating lupins into food, with a growing variety of products made from lupin flour, flakes, and protein concentrates or isolates [26].

Globally, lupins are cultivated for multiple purposes: as a source of high-protein feed and food, as green manure due to their nitrogen-fixing ability, and as ornamental plants. In 2010, major producers included Germany, Poland, Russia, and Mediterranean countries, as well as Australia, South Africa, and South American nations. Australia remains the dominant producer, accounting for nearly 85% of global lupin production in the past decade. In Europe, cultivation is concentrated in Poland, Germany, and Russia, with smaller but regionally significant areas in Belarus and Lithuania. Yield levels vary considerably (from about 1.5 t ha−1 in Poland and Germany to around 0.5 t ha−1 in Lithuania) reflecting differences in climate, soil fertility, and agronomic management [27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34].

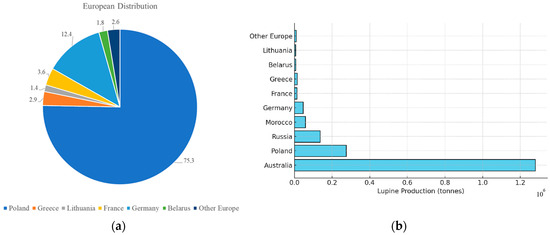

These trends are illustrated in Figure 1, which presents the distribution of lupin cultivation areas and yields across Europe and the world in 2023 [30,31,32,33,34]. As shown, Poland dominates lupin production, followed by Australia and Germany, while Lithuania and Belarus maintain smaller but regionally significant cultivation areas.

Figure 1.

Statistical data (2023): (a)—Lupins harvested in Europe, (b)—Top lupin-producing countries [30,31,32,33,34].

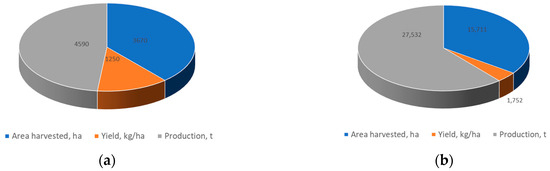

The second figure presents data on the harvested area, yield, production of cultivated lupins in Lithuania and Poland (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Statistical data (2023) for the area harvested for lupin cultivation, yield, and production: (a)—In Lithuania; and (b)—In Poland [34].

As we can see in Figure 2, each chart shows the proportional relationship between three indicators, highlighting significant differences in the scale of lupin cultivation between the two countries.

In Lithuania, the total harvested area was 3670 hectares, with an average yield of 1250 kg per hectare, resulting in a total production of 4590 tonnes. The proportions in the chart indicate that, while the harvested area and yield are moderate, the overall production remains relatively small compared to larger European producers.

In Poland, the harvested area was 157,110 hectares, with an average yield of 1752 kg per hectare, producing approximately 275,320 tonnes of lupins. This demonstrates that Poland is a major European producer, with a harvested area more than forty times larger than that of Lithuania with a higher yield per hectare. Consequently, Poland’s total production is substantially greater, reflecting its leading role in European lupin cultivation [34].

A summary of global and regional production indicators is provided in Table 1, highlighting the contrast between large-scale producers with high yields (such as Australia and Poland) and smaller-scale regions with lower productivity (such as Lithuania and Belarus).

Table 1.

Lupin cultivation and production: Europe and global context (2023) [27,33,34].

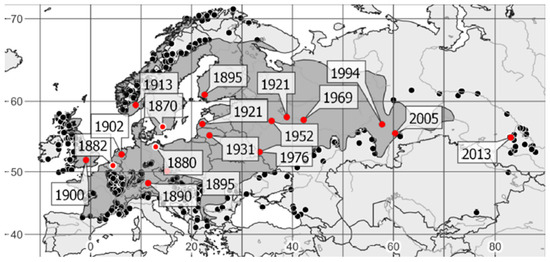

Invasive lupins are a major problem, and their spread and growth are difficult to predict (Figure 3). Therefore, in order to review the seriousness of this problem and respond to the need for sustainability, this article also reviews invasive lupins—Lupinus polyphyllus [35].

Figure 3.

Distribution of Lupinus polyphyllus in Europe: ●; numbers give the first records for the species in different countries/regions: ● [35].

Among cultivated and naturalized species, the large-leaved lupin (Lupinus polyphyllus) is particularly notable due to its ecological duality. Native to western North America, it was introduced to Europe, Australia, and New Zealand as an ornamental and soil-improving plant but has since become invasive in many regions [36,37,38]. The species forms dense stands that suppress native vegetation, alter soil chemistry by increasing nitrogen levels, and disrupt plant–microbe interactions. Its seeds remain viable in the soil for decades, and its deep roots allow regrowth even after repeated mowing, making eradication difficult [13,39]. Studies from Finland, Sweden, and Germany confirm that L. polyphyllus invades semi-natural grasslands, mountain meadows, and roadside habitats, where it reduces biodiversity and changes nutrient cycling dynamics [40,41,42].

In Lithuania, L. polyphyllus has spread widely since its introduction more than half a century ago. Initially planted in forests and meadows for ornamental and soil-improvement purposes, it now grows abundantly along roadsides and in natural habitats. Although lupins enrich the soil with nitrogen through symbiosis with Bradyrhizobium bacteria, their excessive nitrogen accumulation promotes nitrophilous species and suppresses native flora, leading to ecosystem imbalance [13]. The species is therefore listed as invasive, and its sowing, propagation, and trade are prohibited.

From a sustainability perspective, lupins present a clear paradox. On the one hand, they offer high agronomic and nutritional value: they improve soil fertility, reduce the need for mineral fertilizers, and serve as a valuable plant protein source suitable for feed and food production. On the other hand, their invasive potential (especially that of L. polyphyllus) demonstrates how the poorly managed introductions of useful species can lead to biodiversity loss and long-term soil ecosystem alteration. Therefore, balancing the ecological risks of invasive behaviour with the agronomic and environmental benefits of cultivated lupin species is essential for sustainable agriculture. Integrating safe, controlled lupin cultivation into circular bioeconomy frameworks, for example, using biomass for green manure, feed, or bioproducts, can help reconcile these conflicting aspects and contribute to low-input, resource-efficient agroecosystems [14,21,33,34,35,36,37,38,43].

2.2. Chemical Composition and Functional Potential of Lupins

The chemical composition of lupin seeds largely determine their agronomic and nutritional value, influencing their use as feed, food, fertilizer components, and bioenergy raw materials. Differences among species and varieties reflect both genetic and environmental factors, particularly soil fertility and growing conditions.

Table 2 summarizes the main macronutrients and secondary compounds in the seeds of three commonly cultivated lupin species. The data show that the concentration of nitrogen and other nutrients varies not only between species but also between cultivars [44].

Table 2.

Macronutrients and secondary substances in lupin seeds (mg/g dry weight) [35,44].

The high nitrogen and phosphorus contents in blue, yellow and white lupins highlight their dual potential: as a nutrient source in crop rotation and as protein-rich raw material for food or feed. Their mineral composition also suggests potential applications in organic fertilizer production and bio-based product development, reinforcing the importance of chemical profiling in sustainable resource utilization [44].

2.3. Sustainable Utilization of Lupins in the World and in Lithuania

All types of lupins accumulate substances harmful to humans and animals—alkaloids. As a result, lupins were initially unsuitable for either feed or food. However, varieties with fewer alkaloids have been bred. Small amounts of alkaloids are not harmful to animals, but they are not suitable for human consumption because they give dishes a bitter taste. Alkaloids must not be present in edible lupins. According to biological and nutritional value, bitter cultivars with high alkaloid content lupins belong to plants with high protein content. The protein content of bitter cultivars with high alkaloid content fodder lupins is slightly lower than that of yellow-flowered fodder lupins.

Lupin proteins are well-digestible and are considered similar to casein or soy proteins by international standards.

The relative amino acid composition of all lupin species is the same. Proteins contain 18 essential amino acids—of which 1.45 percent is lysine and 0.74 percent is methionine. Due to these properties, lupin seeds can be an excellent feed for cattle, poultry, or pigs, replacing soy and partly corn, barley, wheat, or oats. Lupin seeds contain from 4.6 to 6 percent fat, as well as vitamins, carotene and minerals. The green mass of bitter cultivars with high-alkaloid-content fodder lupins is also valuable, and can be fed fresh, ensiled, or dried. In terms of total protein content and amino acid composition, it is a complete feed, with approximately half of the proteins in it consisting of essential amino acids necessary for the animal body [45]. Lupins (according to some farmers) are like “green” fertilizer. These are plants, also called side rates, are especially prepared and buried in the soil to fertilize it. Green fertilizer includes fodder and narrow-leaved sideral lupins. Lupins themselves provide nitrogen and phosphorus, unconsciously accumulate them in their roots and in the mass, and take nutrients from deeper soil layers and accumulate them, loosen them, and facilitate their absorption. Lupins enrich the soil mainly through the root system of side plants; therefore, they prevent soil erosion and deeply loosen and destroy weeds [12].

Due to the environmental risks caused by Lupinus polyphyllus, different management approaches have been developed to control its spread and to utilize the harvested biomass sustainably. Regular mowing, cutting before seed maturity, and mechanical removal are among the most effective measures [46]. However, the use of the resulting biomass as animal feed is limited by the presence of toxic alkaloids, prompting researchers to explore energy-recovery pathways.

Recent studies have shown that processing lupin biomass into solid biofuels and biogas can contribute to renewable energy generation and invasive species control [35]. When traditional management regimes involve one or two mowings per year and the removal of biomass without fertilizer addition, biodiversity can be maintained while limiting further spread. Hydrothermal conditioning combined with mechanical dewatering significantly improves the fuel quality of lupin biomass, reducing chlorine, potassium, and sulphur concentrations, and enabling safe combustion with modern low-emission technologies [47].

The Integrated Generation of Solid Fuel and Biogas (IFBB) system has been identified as an efficient pathway compared with anaerobic digestion (AD). Life-cycle analyses in Germany demonstrated that IFBB achieves higher greenhouse-gas savings, greater energy-conversion efficiency, and lower overall environmental impact [39]. Importantly, combustion completely destroys viable seeds, preventing the re-invasion and offering a sustainable method for bioenergy production and biodiversity conservation.

Another promising utilization pathway for lupin biomass involves fertilizer production. Lupins are nitrogen-rich plants containing about 6.4% N and 45.5% organic C, making them suitable for both solid and liquid organic fertilizers [14,48,49,50,51]. Experimental studies in Lithuania demonstrated that incorporating lupin leaf extracts into liquid fertilizer formulations increases nitrogen content and provides additional micronutrients [52,53]. The production of liquid complex fertilizers (LCFs) enriched with lupin extract follows several stages: the production of potassium dihydrogen phosphate by the conversion method; the preparation of lupin leaves; the production of granular fertilizers; and the production of liquid complex fertilizers [54].

Ammonium dihydrogen phosphate and potassium chloride are dissolved in a reactor, where a conversion reaction occurs. The resulting phosphate crystals are used for solid fertilizers, while the remaining solution is mixed with ammonium nitrate and lupin extract to produce a microelement-enriched liquid fertilizer. This approach not only provides a practical outlet for invasive biomass but also contributes to the development of environmentally friendly fertilizers, reducing chemical inputs and supporting circular-economy principles [52,53,54].

Beyond its environmental applications, lupin remains a highly valuable food and feed crop. Its seeds contain more protein and dietary fiber than peas, beans, or lentils and have a mild flavour, making them suitable for both sweet and savoury products [55]. Their gluten-free and non-GMO properties further increase demand in functional and health-oriented foods.

Lupin flours and protein isolates are used in bakery goods, meat substitutes, and plant-based beverages due to their emulsifying and foaming capacities. Nutritionally, lupins contribute to lowering LDL cholesterol, stabilizing blood pressure, and promoting satiety. Given global population growth, resource scarcity, and rising food demand, enhancing the added value of lupin-based ingredients represents a crucial strategy for achieving sustainable nutrition and food security [49,55].

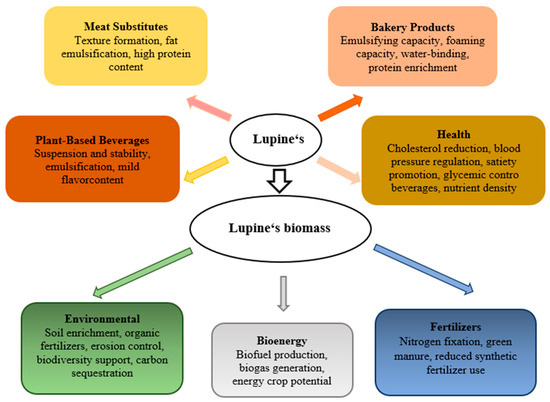

Overall, the conversion of invasive lupin biomass into bioenergy, fertilizers, and protein-rich products exemplifies a holistic circular-economy model (Figure 4). These approaches simultaneously achieve the following:

Figure 4.

Main directions of lupin’s by-product utilization in meat substitutes, bakery products, plant-based beverages, health, bioenergy, environmental applications, and fertilizers (based on reviewed studies) [46,47,48,49,50,51].

- Control invasive species;

- Generate renewable energy;

- Recycle nutrients back into agriculture;

- Enhance plant-based food security.

Such integrated utilization of Lupinus polyphyllus aligns with the EU Green Deal and Sustainable Development Goals by linking biodiversity conservation, low-input farming, and renewable-resource valorisation into a single sustainable framework [39,41,47,52,53,56,57].

3. Buckwheat Waste Recycling for Sustainable Development

3.1. Buckwheat Cultivation and Yield in Europe and the World

Buckwheat (Fagopyrum esculentum) belongs to the family Polygonaceae, which also includes sorrel and rhubarb. Unlike common cereal crops such as wheat, rice, rye, or barley from the grass family, buckwheat is a pseudocereal that thrives in regions with short growing seasons and moderate climatic conditions [58]. Although buckwheat is cultivated under a wide range of climatic conditions, its production remains geographically concentrated in the temperate regions of Eurasia, where it has long-standing agronomic and cultural importance.

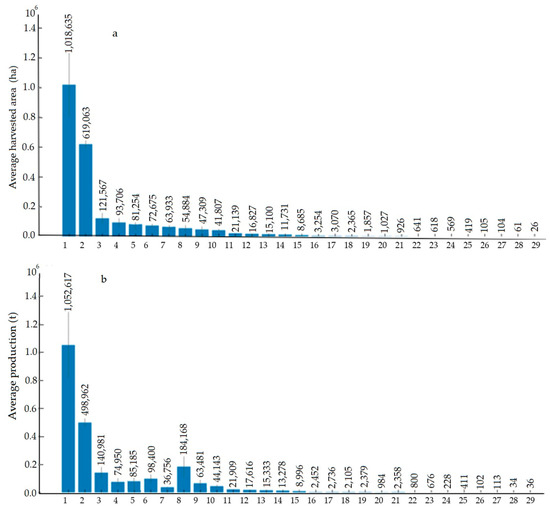

According to ten years of official FAOSTAT data (Figure 5), buckwheat was grown in various climatic regions during the period 2015–2025 and is widely distributed in Europe, America, and Asia.

Figure 5.

FAOSTAT official presented statistical data (2015–2025) from different countries: (a)—average buckwheat harvested area (±SD) worldwide; (b)—average buckwheat production (±SD) worldwide. Markers: 1—Russia, 2—China (includes mainland China, Taiwan, Hong Kong SAR, and Macao SAR), 3—Ukraine, 4—Kazakhstan, 5—United States of America; 6—Poland, 7—Japan, 8—France, 9—Brazil, 10—Lithuania, 11—Tanzania, 12—Belarus, 13—Latvia, 14—Nepal, 15—Canada, 16—Estonia, 17—Slovenia, 18—Korea, 19—Bhutan, 20—Bosnia and Herzegovina. 21—Czechia Republic, 22—Croatia, 23—Hungary, 24—South Africa, 25—Slovakia, 26—Uzbekistan, 27—Georgia, 28—Republic of Moldova, and 29—Kyrgyzstan [34].

However, the largest areas of its cultivation and production are concentrated in Eastern Europe and East Asia, where the Russian Federation and China occupy leading positions globally. As shown in Figure 5a, which presents the average cultivation areas with standard deviations (±SD), other significant buckwheat-producing countries include Ukraine, Kazakhstan, Poland, Japan, and the United States of America. Smaller yet notable cultivation areas are also recorded in France, Lithuania, and Brazil. This distribution reflects both the traditional importance of buckwheat in temperate climate zones and the ongoing expansion of its cultivation into non-traditional regions such as South Africa and Korea. The average buckwheat production data (Figure 5b) reveal a highly uneven global distribution, with the Russian Federation and China clearly dominating the world market. Russia leads by a wide margin, producing on average about 1.03 million tonnes annually, followed by China with approximately 0.49 million tonnes. These two countries together account for more than two-thirds of global buckwheat production. Ukraine and Kazakhstan form a second group of medium-scale producers, averaging around 150–200 thousand tonnes per year. Poland, Japan, France, and Brazil contribute smaller yet notable amounts (between 35 and 80 thousand tonnes). Other countries, including Lithuania, Belarus, Latvia, and Georgia, maintain only marginal production levels, below 20 thousand tonnes annually. The high outputs recorded in France and Japan despite relatively smaller harvested areas suggest more intensive production and higher yields. It should be noted that FAOSTAT data for France are available only until 2017; therefore, the calculated mean production value may be slightly overestimated compared with countries for which longer and more complete time series (2015–2025) are available. Overall, this distribution highlights the strong geographical concentration of buckwheat production in Eastern Europe and East Asia, reflecting favourable agroclimatic conditions and long-standing cultivation traditions in these regions [34]. After evaluating the data presented in Figure 5, more attention was paid to the analysis of the largest buckwheat-growing or Eurasian countries.

Unfortunately, the latest data uploaded to the FAOSTAT (UNdata) database do not reflect the situation in recent years for all EU countries where buckwheat is grown. According to FAOSTAT, the coverage of buckwheat cultivation data in Europe changed noticeably during the period 2015–2025. Data for the period 2015–2017 were available from as many as 17 European countries; therefore, this period can be considered the most comprehensive and representative of the scale of buckwheat cultivation on the continent. Since 2018, however, a significant decline in data availability has been observed—several countries (particularly EU members such as Poland, France, and Lithuania) have no longer provided updated indicators to the FAOSTAT system.

Table 3 summarizes the 2017 FAOSTAT data [59] (when most European growers were still reporting) on buckwheat harvest, yield, and production in the global and European contexts. The total global harvest area was 2.94 million ha, producing 3.04 million tonnes of buckwheat, with an average yield of 1.03 t/ha. Europe accounts for the largest share, with 1.93 million ha harvested and 2.18 million tonnes produced, corresponding to an average yield of 1.13 t/ha. These figures show that Europe alone accounted for more than 70% of the total global production, underlining its dominant role in buckwheat production.

Table 3.

Buckwheat production: Europe and global context (2017) [59].

In Europe, the Russian Federation clearly led the way in production, with 1.50 million ha harvested and 1.52 million tonnes produced, representing a yield of 1.02 t/ha. This accounted for more than half of the total European production and almost half of the world production. Ukraine followed with 185,300 ha and 180,440 t, while Poland showed significantly higher productivity (1.45 t/ha) despite a smaller cultivated area (78,027 ha). Similarly, France achieved the highest recorded yield (3.52 t/ha) in Europe, underlining a clear trend towards intensive and more technologically efficient production systems in Western Europe. Smaller producers such as Lithuania, Belarus, and Georgia contributed in limited but significant quantities, thus contributing to the preservation of buckwheat cultivation traditions in Eurasia.

In Asia, the total harvested area was 852,994 ha and the average yield was 0.80 t/ha, corresponding to a production of 681,030 t. The People’s Republic of China dominated the Asian region, accounting for 74% of the Asian harvested area (632,746 ha) and producing 508,844 t, which is about 17% of the global buckwheat production. Meanwhile, Japan only cultivated 62,900 ha with a yield of a modest 0.55 t/ha, confirming that buckwheat remains largely a niche crop in Japan, grown for traditional and culinary purposes.

Elsewhere, North America produced 88,215 t with an average yield of 1.04 t/ha, mainly from the United States, which accounted for almost all of North American production. South America, although covering a smaller area (47,252 ha), showed a relatively high yield (1.33 t/ha), indicating favourable agroclimatic conditions for buckwheat production in the selected areas.

Overall, the 2017 data confirm that buckwheat cultivation remains predominantly Eurasian, concentrated in temperate zones from eastern Europe to east Asia. Differences in yield between regions reflect a complex interplay of agroecological conditions, varietal characteristics, and management intensity. Western European countries (e.g., France, Poland) have clearly shifted towards higher productivity per hectare, while Eastern Europe and Asia maintain larger areas of cultivation with average yields, supporting global supply through extensive production systems.

To illustrate the recent tendencies, the 2020–2023 FAO data were additionally examined. For the period 2020–2023, data were available only from seven European countries (the Russian Federation, Ukraine, Kazakhstan, Belarus, Moldova, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Georgia), making them rather fragmentary. This trend indicates disparities in data reporting and updating between regions, which makes comprehensive comparisons and analyses difficult [34].

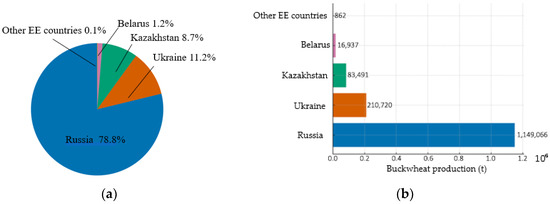

Within Europe, the distribution of buckwheat cultivation areas is highly uneven (Figure 6a). According to FAO data for 2023, Russia accounts for approximately 78.8% of the total harvested area, reflecting both its historical importance and agroclimatic suitability for this crop. It is followed by Ukraine (11.2%), Kazakhstan (8.7%), and Belarus (1.2%), while other eastern European countries together contribute only 0.1%. The distribution of buckwheat production in Eastern Europe is also highly uneven (Figure 6b). According to FAO data for 2023, Russia is by far the leading producer, accounting for more than 1.1 million tonnes of buckwheat, followed by Ukraine (approximately 210 thousand tonnes) and Kazakhstan (about 83 thousand tonnes). Production in Belarus remains modest (nearly 17 thousand tonnes), while other eastern European countries together produce less than 1 thousand tonnes. This clearly indicates that the regional buckwheat output is overwhelmingly concentrated in Russia, consistent with the pattern observed for the harvested area.

Figure 6.

FAOSTAT data (2023): (a)—buckwheat harvested area in Europe; (b)—buckwheat-production [59]. Other eastern European (EE) countries: Moldova, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Georgia.

Beyond its importance as a food crop, buckwheat also serves ecological and agronomic functions. Compared to spring wheat, buckwheat has a high ability to take up calcium-bound phosphorus. Therefore, buckwheat can be included in catch crops or crop rotation systems to activate phosphorus sources in calcareous soils. These properties support its role in sustainable farming systems and crop rotations, particularly in regions with poor or degraded soils [60,61].

Due to the increasing fragmentation of FAOSTAT data in recent years, information on buckwheat cultivation trends in some countries can only be obtained from national statistics. At the regional level, cultivation trends in Central and Eastern Europe demonstrate both continuity and change. Although buckwheat cultivation and seed selection have a long tradition in Poland, recent years show a moderate decline in the cultivation area. In 2024, the area under buckwheat cultivation decreased to about 101,000 ha, compared with approximately 109,000 ha in 2023 (−8%). Nevertheless, Polish buckwheat production in 2023 remained significant at about 152,000 tons, confirming Poland’s position as one of the key European producers, although not a global leader. Yields in Poland range between 0.878 and 1.216 t/ha, depending on the year and growing conditions, which directly affects both production costs and market prices [58,62,63].

In Ukraine, a similar but more pronounced decline has been observed. The buckwheat cultivation area fell from 147,600 ha in 2023 to about 100,000 ha in 2024 (a 32% decrease). Total production in 2024 reached approximately 131.7 thousand tons, corresponding to an average yield of ~1.5 t/ha [64]. This recent decline in Ukraine is likely related not only to the military conflict, but also to a combination of economic and environmental factors—falling buckwheat prices, increased import pressure, and regional climate and harvest risks. If such trends continue, the global production structure will become even more concentrated in the larger producers such as Russia and Kazakhstan.

These data emphasize the asymmetric but stable structure of global buckwheat production: concentrated in a few major producers yet supported by a network of smaller regions that preserve crop diversity. From a sustainability perspective, this pattern underscores buckwheat’s dual role as both a culturally traditional and ecologically resilient crop, capable of contributing to regional food security and low-input agriculture in a changing climate [33,58,59,60,61,62,63].

3.2. Nutritional and Chemical Composition of Buckwheat and Valorisation of Its by Products

Buckwheat is widely recognized as a functional food rich in proteins, dietary fibre, minerals, and bioactive compounds—particularly flavonoids such as rutin and quercetin. These constituents contribute to antioxidant, antidiabetic, antihypertensive, and anti-inflammatory effects, which are increasingly associated with the prevention of lifestyle-related diseases. Beyond its nutritional properties, buckwheat extracts have shown promise as natural antioxidants and components in biodegradable, active food packaging, reinforcing its role as a versatile and sustainable crop. Thus, buckwheat can be considered a “superfood” with broad potential applications in both health promotion and food technology.

From the perspective of food functionality, the key biochemical groups of buckwheat include proteins, bioactive peptides, flavonoids, and phenolic compounds, as well as essential minerals and vitamins (Table 4). These compounds define both its nutritional value and potential industrial applications.

Table 4.

Buckwheat composition, health effects, and applications [65].

Beyond its nutritional role, the processing of buckwheat generates significant by-products such as husks and husk ash. These materials, often underutilized, are now increasingly recognized as valuable sources of minerals, carbon, and bioactive compounds. Their valorisation aligns with circular-economy principles, aiming to convert agricultural residues into high-value materials for fertilizers, bioenergy, or sorbents in environmental applications. The chemical composition (Table 5) of buckwheat by-products varies considerably depending on the geographical origin, soil characteristics, and processing conditions, underscoring the importance of characterizing local raw materials to optimize their utilization in fertilizer production, bioenergy, and environmental technologies.

Table 5.

Chemical composition of buckwheat by-products in different studies [65].

Data presented in Table 5 show that buckwheat husks are characterized by a predominantly organic composition, rich in structural carbohydrates and containing moderate amounts of nitrogen and minerals. Cellulose and lignin together represent about 60–70% of the husk dry mass, while crude protein levels remain below 5%. This reflects the plant’s need for mechanical stability rather than nutrient storage in the husk tissue. Lithuanian and Russian data confirm relatively high carbon contents (around 50–54%) and low ash fractions (approximately 6–7%), indicating a strong potential for energy recovery through combustion or biochar production. In addition, minor but consistent amounts of potassium (around 7–8% K2O equivalent) and calcium oxides suggest that a portion of mineral nutrients is already incorporated in the husk matrix, potentially influencing ash quality after thermal treatment.

In contrast, the chemical profile of buckwheat husk ash demonstrates a marked transformation from organic to mineral dominance. Following combustion, the carbon content decreases sharply (to around 30%), while mineral oxides become highly concentrated. Studies from Lithuania and Belarus show that potassium oxide (K2O) may reach 35–40%, and calcium oxide (CaO) up to 12–15%, accompanied by smaller fractions of MgO, Fe, and Zn. This compositional shift produces an alkaline and nutrient-rich residue, suggesting high agronomic value as a liming or potassium fertilizer material. The elevated Fe and Zn concentrations (often exceeding 1000 mg/kg and 500 mg/kg, respectively) indicate that micronutrients, originally present in trace amounts within husks, become strongly enriched in the ash phase.

In addition, the composition of individual parts of buckwheat plants can be analyzed from another perspective, as was performed by scientists from the Czech Republic [84], who found that the chemical composition of buckwheat varies considerably among plant organs. The roots and stalks contained low amounts of crude protein (5.6 ± 0.16% and 6.5 ± 0.03%, respectively) and almost no starch (0.0 ± 0.01% and 1.1 ± 0.01%), while their fat content remained moderate (4.3 ± 0.01% and 2.6 ± 0.01%). In contrast, the leaves and blossoms were characterized by much higher protein concentrations (22.7 ± 0.26% and 19.1 ± 0.10%) and by the accumulation of bioactive flavonoids, particularly rutin. The rutin content increased sharply from 3.6 ± 0.12 mg g−1 in roots and 0.5 ± 0.09 mg g−1 in stalks to 69.9 ± 2.7 mg g−1 in leaves and 83.6 ± 3.1 mg g−1 in blossoms. These findings indicate an intensive biosynthesis of rutin and proteins in photosynthetically active and reproductive tissues, whereas structural parts such as roots and stalks serve mainly for mechanical support and resource transport. This compositional differentiation reflects the distinct metabolic roles of individual organs within the buckwheat plant. This pattern of tissue-specific compound distribution has also been observed in other studies, e.g., by Suzuki et al. [85], which demonstrated that rutin accumulates differentially across seeds, leaves, stems, and flowers of buckwheat, reflecting its diverse physiological roles within the plant.

Overall, these findings demonstrate that the valorisation of buckwheat residues (particularly husks and husk ash) represents a key component of sustainable agri-food systems, enabling waste minimization, nutrient recycling, and renewable energy generation. Such approaches exemplify the transition towards a circular bioeconomy and align with the objectives of the EU Green Deal and the Sustainable Development Goals, ensuring that each stage of crop processing contributes to environmental, economic, and resource sustainability [86].

3.3. Valorisation Pathways and Secondary Uses of Buckwheat Processing Residues

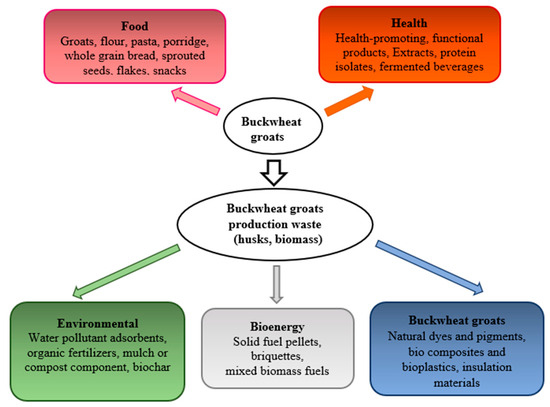

Considering the nutritional and chemical composition results presented in Section 3.2, further analysis of the valorisation pathways reveals how specific buckwheat processing residues can be utilized across various technological and environmental applications. Buckwheat (Fagopyrum esculentum) and its by-products represent a versatile resource with significant nutritional, technological, and environmental potential. The wide range of studies demonstrates that the valorisation of buckwheat residues (mainly husks, and husk ash) can contribute to sustainable food systems, renewable energy production, and circular bioeconomy development.

One of the most promising directions in the sustainable use of buckwheat lies in its potential for functional food production. Buckwheat contains phenolic compounds, flavonoids (especially rutin), antioxidants, and dietary fibre, which collectively exhibit anti-inflammatory, anticarcinogenic, and antioxidant properties beneficial to human health [87]. As a gluten-free pseudocereal, it is particularly valuable for specialized and preventive diets. Similar conclusions were reported by Lițoiu [88], who emphasized its richness in proteins, minerals, B-group vitamins, and phenolic compounds. These features enable the development of low-calorie, high-protein, and health-promoting foods. Beyond traditional groats, innovative processing methods expand buckwheat’s value chain. Studies highlight the potential for producing beverages, extracts, protein isolates, and fermentation products with enhanced bioactivity. Wang, N. [89] showed that germination significantly increases flavonoid, phenolic, and antioxidant contents in Fagopyrum tataricum sprouts, suggesting that both grains and sprouts represent valuable raw materials for high-value food ingredients. Collectively, these studies demonstrate that buckwheat valorisation in the food sector links nutrition enhancement with the reduction in processing waste, offering a model for sustainable and health-oriented product development.

The transformation of buckwheat husks into renewable energy sources represents another key valorisation pathway. Yildiz et al. [81] investigated the co-granulation of buckwheat husks with peanut husks and senna leaves, revealing that the additive proportions and granulation parameters strongly affect pellet quality and energy output. In their study, the authors referred to the findings of Kulokas et al. [77], who reported that buckwheat husks contain approximately 41.8% carbon and exhibit a calorific value of about 15.7 MJ kg−1, comparable to wood biomass. Based on their own experiments, Yildiz et al. [81] determined the physicochemical and combustion characteristics of the produced pellets according to international ISO standards: ISO 18122:2015 (ash content), ISO 18123:2015 (volatile matter), and ISO 1928:2020 (gross calorific value) [90,91,92]. The results showed that the co-granulation of buckwheat hulls with peanut shells or sena leaves significantly improved the physical and energetic properties of the pellets, increasing their durability (up to ~92%) and bulk density (~470 kg m−3), while reducing the energy requirement for production. This means that the average amount of additives improved the quality of the pellets without compromising the fuel properties. However, the increased CO and NO emissions during combustion indicate that the further optimization of the blend composition and combustion parameters is needed to achieve cleaner and more efficient biofuel utilization. Other researchers have reported that co-palletisation of husks with straw or wood fibbers reduces chlorine content and corrosion risk, improving fuel safety and extending boiler lifespan [77]. These findings demonstrate that buckwheat residues can contribute to energy diversification and carbon neutrality in agricultural regions where other biomass resources are underutilized.

Another important valorisation direction involves the use of buckwheat husks and husk ash as raw materials for organic–mineral fertilizers. Chemical analyses revealed high concentrations of elements essential for plant growth: P2O5 (0.28–5.84%), K2O (4.56–38.63%), CaO (0.09–12.18%), MgO (0.47–3.56%), and carbon (29.5–54.35%) [65]. Such nutrient-rich composition enhances soil fertility and supports nutrient cycling while reducing dependence on synthetic fertilizers. The integration of these materials into fertilizer formulations could help maintain soil carbon balance and improve agroecosystem resilience. Compared with conventional fertilizers, buckwheat-based fertilizers provide slow nutrient release, reducing leaching and environmental load—an important contribution to sustainable agriculture and circular nutrient management. Environmental applications of buckwheat residues are also expanding. Adamović, M. [24] demonstrated that modified buckwheat husks can act as efficient bio sorbents for removing heavy metals (Hg2+, Cd2+, Cr6+, Zn2+, Au3+), dyes, and pesticides, with adsorption capacities up to 100 mg/g. Their low cost, abundance, and biodegradability make them promising substitutes for activated carbon in water treatment technologies. Somin, Komarova, and Kutalova [93] further showed that husk-based adsorbents can reduce water hardness by up to 62%, offering a low cost, eco-friendly method for water purification. These studies reveal that buckwheat residues contribute not only to waste reduction but also to environmental remediation, closing material cycles in a way consistent with circular economy principles.

In addition to food and environmental applications, buckwheat husks show potential in the development of innovative materials. Nawirska-Olszańska’s [94] clinical studies reported that husk-filled pillows, mattresses, and seats exhibit high air permeability, elasticity, and comfort, supporting their use in therapeutic products. Siauciunas et al. [95] found that adding husks to easily fusible clay ceramics improves porosity and thermal insulation, reducing weight and energy consumption during firing, though with some loss of mechanical strength. Furthermore, Vázquez-Fletes and Cherkashina [96] explored buckwheat husks as fillers for polymer composites. Chemical and plasma surface modification enhanced interfacial bonding in high-density polyethylene (HDPE) and polylactide (PLA) matrices, producing biodegradable composites with improved mechanical and moisture resistance properties. Mostovoy [97] developed oil spill sorbents based on carbonized buckwheat hulls, achieving adsorption capacities of up to 6.1 g/g for crude oil, with prolonged buoyancy. These examples illustrate how agricultural residues can serve as sustainable feedstocks for bio-based and eco-friendly materials.

Figure 7 summarizes the main directions of buckwheat by-product valorisation identified in the reviewed literature.

Figure 7.

Main directions of buckwheat by-product utilization in food, energy, environmental, and material applications (based on reviewed studies) [66,98,99,100,101,102,103].

As illustrated in Figure 7, the valorisation of buckwheat and its processing residues forms an interconnected system linking the food, energy, environmental, and materials sectors. Each pathway supports a different aspect of sustainability—from improving human nutrition and soil fertility to generating renewable energy and reducing waste streams.

This versatility highlights buckwheat as an exemplary circular crop capable of closing multiple bioeconomic loops. Its low agronomic input requirements, adaptability to marginal soils, and nutrient-rich by-products make it not only a functional food resource but also a cornerstone for sustainable rural development and circular bioeconomy strategies in temperate regions.

4. Limitations of the Review

It should be noted that this review has certain limitations related to data coverage, methodological diversity, and regional focus. This review is primarily based on publications indexed in international databases such as Scopus, ScienceDirect, and Web of Science, supplemented by regional sources from eastern and central Europe. As a result, the geographical coverage of data is somewhat uneven, with limited representation of studies from other regions. Part of the reviewed articles were published in English, Polish, Lithuanian, or Russian, which may introduce a minor language bias. The reported analytical data also show methodological heterogeneity, including differences in moisture basis, combustion and elemental analysis methods, and the expression of results (e.g., dry vs. wet weight, oxide vs. elemental form). Consequently, while the presented findings provide a robust comparative overview of lupin and buckwheat biomass properties and valorisation pathways, the direct quantitative comparability of some parameters across studies remains limited. Future reviews should aim to integrate standardized methodologies and broader geographic datasets to strengthen the regional transferability and global applicability of conclusions.

5. Conclusions and Perspectives

Lupins (Lupinus spp.) and buckwheat (Fagopyrum esculentum) represent two contrasting yet complementary models of sustainable crops within the European bioeconomy. Both plants species demonstrate the capacity to enhance soil fertility, diversify agricultural systems, and supply valuable plant-based proteins and bioactive compounds. However, their ecological and agronomic characteristics lead to different challenges and opportunities that shape their role in sustainable agriculture.

The analysis of published studies indicates that Lupinus spp. biomass contains approximately 6–7% nitrogen and about 45% organic carbon, with lower heating values (LHVs) ranging between 16 and 17 MJ·kg−1. Such a chemical and energetic profile supports the dual valorisation of lupin residues as nutrient-rich feedstock for organic fertilizer production and as a renewable bioenergy source. Lupinus species can occur both as cultivated and invasive plants, which makes their comprehensive and sustainable utilization particularly important to minimize ecological risks while maximizing resource efficiency. Moreover, the literature evidence shows that the conversion of invasive Lupinus polyphyllus biomass through IFBB or hydrothermal pretreatment systems not only improves fuel quality by reducing chlorine and alkali contents but also provides a sustainable means of controlling its spread while generating renewable energy. Among the potential pathways, the production of liquid and solid fertilizers from lupin biomass and extracts appear particularly promising due to its high nitrogen content and capacity to enhance soil fertility, whereas bioenergy conversion offers additional ecological benefits through the safe utilization of invasive biomass. These directions highlight Lupinus spp. as a multifunctional crop group capable of linking soil restoration, renewable energy generation, and biodiversity management within a circular bioeconomy framework.

Buckwheat, in contrast, is a non-invasive, low-input crop that thrives on marginal soils and supports pollinator diversity. It contributes to sustainable food systems through its exceptional nutritional composition (rich in proteins, flavonoids, minerals, and antioxidants) and through the versatile reuse of its processing residues. Literature data indicate that Fagopyrum esculentum residues, i.e., particularly husks and husk ash, possess complementary valorisation potential. Buckwheat husks, with moderate ash content (3–7%), carbon levels around 50%, and a lower heating value near 15.7 MJ·kg−1, are suitable for solid biofuel production and co-pelletization with other biomass sources. In contrast, the husk ash, rich in K2O (35–40%), CaO (10–15%), and micronutrients such as Fe and Zn, represents a valuable alkaline and potassium fertilizer feedstock that can support soil fertility restoration and nutrient recycling. These findings underline that energy recovery from the husks and the agronomic reuse of ash together exemplify a closed-loop approach consistent with circular bioeconomy principles. Among the valorisation pathways discussed in the literature, nutrient recycling through husk ash fertilization and bioenergy recovery from husks currently offer the highest technological maturity and environmental relevance. Meanwhile, emerging applications (such as the use of modified buckwheat residues as biosorbents for water purification and as fillers in bio composites or biodegradable packaging materials) represent promising long-term directions for sustainable innovation within the agri-food and bio-based materials sectors.

Together, these two crops illustrate how sustainable agriculture can align productivity with ecological integrity. Both support the transition from linear to circular agricultural systems, where waste is minimized and resources are continually reused. By addressing these research gaps, lupins, and buckwheat can evolve from niche or regionally constrained crops into key components of a resilient, circular, and climate-smart agroecosystem. Their combined valorisation potential demonstrates how plant diversity can contribute not only to food and energy security but also to ecosystem health and rural sustainability in the long term.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.J. and R.Š.; software, K.J.; resources, K.J., R.Š. and O.P.; data curation K.J., R.Š. and O.P.; writing—original draft preparation K.J. and R.Š.; writing—review and editing, K.J. and R.Š.; visualization, K.J. and R.Š.; supervision, K.J. and R.Š. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- FAO. The State of Food and Agriculture; Electronic Publishing Policy and Support Branch, Communication Division, FAO: Rome, Italy, 2009; pp. 9–19. [Google Scholar]

- Tilman, D.; Balzer, C.; Hill, J.; Befort, B.L. Global food demand and the sustainable intensification of agriculture. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 20260–20264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouwman, L.; Goldewijk, K.K.; Van Der Hoek, K.W.; Beusen, A.H.W.; van Vuuren, D.P.; Willems, J.; Rufino, M.C.; Stehfest, E. Exploring global changes in nitrogen and phosphorus cycles in agriculture induced by livestock production over the 1900–2050 period. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 20882–20887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirchherr, J.; Reike, D.; Hekkert, M. Conceptualizing the circular economy: An analysis of 114 definitions. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 127, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, L.; Rangan, A.; Grafenauer, S. Lupins and Health Outcomes: A Systematic Literature Review. Nutrients 2022, 14, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pseudocereals for Global Food Production. 2020. Available online: https://www.cerealsgrains.org/publications/cfw/2020/March-April/Pages/CFW-65-2-0014.aspx?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- Çevik, A.; Ertas, N. Effect of quinoa, buckwheat and lupine on nutritional properties and consumer preferences of tarhana. Qual. Assur. Saf. Crops Foods 2019, 11, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega Irizo, F.J.; Gavilan Ruiz, J.M.; Jaen Figueroa, I. The Effect of Economic and Cultural Factors on Entrepreneurial Activity: An Approach through Frontier Production Models. Rev. De Econ. Mund. 2020, 55, 25–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, N.; Herrera, I.; Fajardo, L.; Bustamante, R.O. Meta-analysis of the impact of plant invasions on soil microbial communities. BMC Ecol. Evol. 2021, 21, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jauni, M.; Ramula, S. Demographic mechanisms of disturbance and plant diversity promoting the establishment of invasive Lupinus polyphyllus. J. Plant Ecol. 2016, 10, 510–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacher, S. Global Impacts Dataset of Invasive Alien Species (GIDIAS). Sci. Data. 2025, 12, 832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sideral Plant Mixtures. Available online: https://www.linasagro.lt/prekes/sideraliniu-augalu-misinys-nitrofix (accessed on 28 February 2023).

- List of Invasive Species in Lithuania. 2023. Available online: https://am.lrv.lt/lt/veiklos-sritys-1/gamtos-apsauga/invazines-rusys/invaziniu-lietuvoje-rusiu-sarasas (accessed on 3 March 2023).

- Lupines—An Invasive Species. 2024. Available online: https://vstt.lrv.lt/lt/naujienos/lubinai-invazine-rusis/ (accessed on 7 October 2025).

- Luo, H.; Zhang, Z.; Fang, X.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Z.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, K.; Yi, Z.; Ding, M. Rhizosphere abundant bacteria enhance buckwheat yield, while rare taxa regulate soil chemistry under diversified crop rotations. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2025, 393, 109781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lejinš, A.; Lejina, B. The buckwheat role in crop rotation and weed control in this sowing in long term trial. In Environment. Technology. Resources, Proceedings of the 7th International Scientific and Practical Conference, Rezekne, Latvia, 25–27 June 2009; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Lithuanian Buckwheat Is Appreciated by Both Buyers and Consumers. Available online: https://ukininkopatarejas.lt/naujienos/lietuviskus-grikius-vertina-ir-supirkejai-ir-vartotojai/ (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- Buckwheat Is Making Its Way to Farmers’ Fields. Available online: https://www.agroakademija.lt/s/augalininkyste/grikiai-skinasi-kelia-i-augintoju-laukus-13879/ (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Buckwheat Cultivation. Available online: https://www.viskas.lt/straipsniai/45533-grikiu-auginimas (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- Bebeli, P.J.; Lazaridi, E.; Chatzigeorgiou, T.; Suso, M.-J.; Hein, W.; Alexopoulos, A.A.; Canha, G.; van Haren, R.J.; Jóhannsson, M.H.; Mateos, C.; et al. State and Progress of Andean Lupin Cultivation in Europe: A Review. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, M.M.; Stoddard, F.L.; Annicchiarico, P.; Frías, J.; Martínez-Villaluenga, C.; Sussmann, D.; Duranti, M.; Seger, A.; Zander, P.M.; Pueyo, J.J. The future of lupin as a protein crop in Europe. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atambayeva, Z.; Nurgazezova, A.; Amirkhanov, K.; Assirzhanova, Z.; Khaimuldinova, A.; Charchoghlyan, H.; Kaygusuz, M. Unlocking the Potential of Buckwheat Hulls, Sprouts, and Extracts: Innovative Food Product Development, Bioactive Compounds, and Health Benefits—A Review. Pol. J. Food Nutr. Sci. 2024, 74, 293–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamaratskaia, G.; Gerhardt, K.; Knicky, M.; Wendin, K. Buckwheat: An underutilized crop with attractive sensory qualities and health benefits. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 64, 12303–12318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamović, M.; Stjepanović, M.; Velić, N. Exploring the potential of buckwheat hull-based biosorbents for efficient water pollutant removal. Croat. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 16, 273–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolko, B.; Clements, J.C.; Naganowska, B.; Nelson, M.N.; Yang, H. Lupinus. In Wild Crop Relatives: Genomic and Breeding Resources; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 153–163. [Google Scholar]

- Lupins—Botany and Global Use in Agriculture. Available online: https://aussielupins.org.au/about/ (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Pollination Aware Case Study: Lupins. Available online: https://agrifutures.com.au/product/pollination-aware-case-study-lupins/ (accessed on 19 February 2023).

- Carvajal-Larenas, E.F.; Linnemann, R.A.; Nout, J.R.M.; Koziol, M.; Boekel, A.J.S.M. Lupinus mutabilis: Composition, Uses, Toxicology, and Debittering. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2016, 56, 1454–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger, J.D.; AdhikariB, K.N.; Wilkinson, D.; Buirchell, B.J.; Sweetingham, M.W. Ecogeography of the Old-World lupins. 1. Ecotypic variation in yellow lupin (Lupinus luteus L.). Aust. J. Agric. Res. 2008, 59, 691–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupin Production in Poland. Available online: https://www.helgilibrary.com/indicators/lupin-production/poland/ (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- Which Country Produces the Most Lupins? Available online: https://www.helgilibrary.com/charts/which-country-produces-the-most-lupins/ (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Lupin. Available online: https://www.tridge.com/intelligences/lupin-bean/DE/production (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Environment, Agriculture and Energy in Lithuania (Edition 2022). Available online: https://osp.stat.gov.lt/en/lietuvos-aplinka-zemes-ukis-ir-energetika-2022/zemes-ukis/augalininkyste (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- Crops and Livestock Products. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QCL (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Volz, H. Ursachen und Auswirkungen der Ausbreitung von Lupinus Polyphyllus Lindl. Im Bergwiesenökosystem der Rhön und Maßnahmen zu seiner Regulierung. 2003. Available online: https://www.db-thueringen.de/servlets/MCRFileNodeServlet/dbt_derivate_00009704/VolzHarald-2003-10-14.pdf (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Galkina, M.A.; Ivanovskii, A.A.; Vasilyeva, N.V.; Stogova, A.V.; Zueva, M.A.; Mamontov, A.K.; Bochkov, D.A.; Prokhorov, A.A.; Tkacheva, E.V. Invasive plant Lupinus polyphyllus demonstrates high level of molecular genetic variation within and between populations at East European Plain. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 14960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, D. The rise to dominance over two decades of Lupinus polyphyllus among pasture mixtures in tussock grassland trials. Proc. N. Z. Grassl. Assoc. 2014, 76, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Invasive Lupines Are Finally Driving Daisies Out of Meadows. Available online: https://www.valstietis.lt/sodyba/lauku-ramunes-is-pievu-baigia-isvyti-invaziniai-lubinai/120194 (accessed on 22 February 2022).

- Joseph, B.; Hensgen, F.; Wachendorf, M. Life Cycle Assessment of bioenergy production from mountainous grasslands invaded by lupine (Lupinus polyphyllus Lindl.). J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 275, 111182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prass, M.; Ramula, S.; Jauni, M.; Setala, H.; Kotze, D.J. The invasive herb Lupinus polyphyllus can reduce plant species richness independently of local invasion age. Biol. Invasions 2022, 24, 425–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hensgen, F.; Wachendorf, M. The Effect of the Invasive Plant Species Lupinus polyphyllus Lindl. on Energy Recovery Parameters of Semi-Natural Grassland Biomass. Sustainability 2016, 8, 998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckstein, R.L.; Welk, E.; Klinger, Y.P.; Lennartsson, T.; Wissman, J.; Ludewig, K.; Hansen, W.; Ramula, S. Biological flora of Central Europe—Lupinus polyphyllus Lindley. Perspect. Plant Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2023, 58, 125715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EPPO Global Database. Available online: https://gd.eppo.int/taxon/LUPPO (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Green Manure. Available online: http://www.agrozinios.lt/portal/categories/133/1/0/1/article/10769/zalioji-trasa (accessed on 23 February 2023).

- The Future for Narrow-Leaved Lupins. Available online: https://manoukis.lt/mano-ukis-zurnalas/2005/10/ateitis-siauralapiams-lubinams/ (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Meiera, C.I.; Reid, B.L.; Sandovala, O. Effects oftheinvasiveplant Lupinus polyphyllus on verticalaccretion of finesedimentandnutrientavailabilityinbarsofthegravel-bed Paloma River. Limnologica 2013, 43, 381–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hensgen, F.; Wachendorf, M. Producing solid biofuels from semi-natural grasslands invaded by Lupinus polyphyllus. Sustain. Meat Milk Prod. Grassl. 2018, 23, 854. [Google Scholar]

- Ground Lupins, Fertilizer for Citrus Fruits. Available online: https://www.geosism.com/en/fertilizers/121-lupine-1-3-mm-25-kg-ground-lupins-fertilizer-for-citrus-fruits-8010870861016.html (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- Knecht, K.T.; Sanchez, P.; Kinder, D.H. Lupine Seeds (Lupinus spp.): History of Use, Use as An Antihyperglycemic Medicinal, and Use as a Food Plant. In Nuts and Seeds in Health and Disease Prevention, 2nd ed.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2020; pp. 393–402. [Google Scholar]

- Ačko, D.K.; Flajšman, M. Production and Utilization of Lupinus spp. In Production and Utilization of Legumes—Progress and Prospects; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2023; pp. 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Hassani, M.; Elisa Vallius, E.; Rasi, S.; Sormunen, K. Risk of Invasive Lupinus polyphyllus Seed Survival in Biomass Treatment Processes. Diversity 2021, 13, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masiulytė, D. Synthesis of Potassium Dihydrogen Phosphate and Production of Bioactive Compound Fertilizers. 2024, p. 58. Available online: https://epubl.ktu.edu/object/elaba:199304530/index.html (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Sidaraitė, R. Obtaining Liquid Complex Fertilizers with Trace Elements. 2023, p. 70. Available online: https://epubl.ktu.edu/object/elaba:169601015/ (accessed on 4 September 2025).

- Jančaitienė, K.; Sidaraitė, R. Liquid Complex Fertilizers with Bio-Additives. Proceedings 2023, 92, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Noort, M. Lupin: An Important Protein and Nutrient Source. Sustain. Protein Sources 2017, 165–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Invasive Alien Species. Available online: https://environment.ec.europa.eu/topics/nature-and-biodiversity/invasive-alien-species_en (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Biodiversity Strategy for 2030. Available online: https://environment.ec.europa.eu/strategy/biodiversity-strategy-2030_en (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Buckwheat: The Game-Changer in The Food Industry. Available online: https://seedea.pl/buckwheat-the-game-changer-in-the-food-industry/ (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- United Nations Data Retrieval System. Available online: https://data.un.org/Data.aspx?d=FAO&f=itemCode:89 (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Zhu, Y.G.; He, Y.Q.; Smith, S.E.; Smith, F.A. Buckwheat (Fagopyrum esculentum Moench) has high capacity to take up phosphorus (P) from a calcium (Ca)-bound Source. Plant Soil. 2002, 239, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, R. Growing Buckwheat for Grain or Cover Crop Use. Publication No. G4163. 2018. Available online: https://extension.missouri.edu/publications/g4163 (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Kwiatkowski, J. Buckwheat Breeding and Seed Production in Poland. Fagopyrum 2023, 40, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Góral, P. Buckwheat: 2022 Planting Increases by 21% in Poland but Prices Likely to Stay High. Available online: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/buckwheat-2022-planting-increases-21-poland-prices-likely-piotr-g%C3%B3ral/ (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Slight Reduction in Buckwheat Acreage in Ukraine is Predicted. Available online: https://ukragroconsult.com/en/news/slight-reduction-in-buckwheat-acreage-in-ukraine-is-predicted/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 16 August 2025).

- Pocienė, O.; Šlinkšienė, R. Studies on the Possibilities of Processing Buckwheat Husks and Ash in the Production of Environmentally Friendly Fertilizers. Agriculture 2022, 12, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matseychik, I.V.; Korpacheva, S.M.; Lomovsky, I.; Serasutdinova, K.R. Influence of buckwheat by-products on the antioxidant activity of functional desserts. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 640, 022038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkachenko, A.O.; Sahdieieva, O.A.; Krusir, G.V.; Malovanyy, M.S.; Vitiuk, A.V. Buckwheat husk biochar: Preparation and study of acid-base and ion-exchange properties. J. Chem. Technol. 2024, 32, 694–705. Available online: http://chemistry.dnu.dp.ua/article/view/306261 (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Jara, P.; Schoeninger, V.; Dias, L.; Siqueira, V.; Lourente, E. Physicochemical quality characteristics of buckwheat flour. Eng. Agric. 2022, 42, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Du, C.; Chen, J.; Shi, L.; Li, H. A New Method for Determination of Pectin Content Using Spectropho-tometry. Polymers 2021, 13, 2847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krusir, G.; Sagdeeva, O.; Malovanyy, M.; Shunko, H.; Gnizdovskyi, O. Investigation of Enzymatic Degradation of Solid Winemaking Wastes. J. Ecol. Eng. 2020, 21, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillsbury, D.M.; Kulchar, G.V. The use of the Hagedorn-Jensen method in the determination of skin glucose. J. Biol. Chem. 1934, 106, 351–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, B.A. Methods for the determination of total organic carbon (TOC) in soils and sediments. Ecol. Risk. Assess. Support Cent. 2002, 1–23. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/291996839_Methods_for_the_determination_of_total_organic_carbon_TOC_in_soils_and_sediments_ecological_risk_assessment_support_center (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- ISO 11261:1995; Soil Quality—Determination of Total Nitrogen—Modified Kjeldahl Method. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1995. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/19239.html (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- EN 15959:2011; Fertilizers—Determination of Total Phosphorus—Spectrometric Method. European committee for standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2011. Available online: https://standards.iteh.ai/catalog/standards/cen/331263f2-ad7a-4d20-bccb-6bfafb797e62/en-15959-2011?srsltid=AfmBOoocuXRn25xA214THvX7fQWa3OCTJZLU8SQyGl1ZtOYpcDb2aOVA (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Ullah, R.; Abbas, Z.; Bilal, M.; Habib, F.; Iqbal, J.; Bashir, F.; Noor, S.; Qazi, M.A.; Niaz, A.; Baig, K.S.; et al. Method development and validation for the determination of potassium (K2O) in fertilizer samples by flame photometry technique. J. King. Saud. Univ Sci. 2022, 34, 102070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 11047:1998; Soil Quality—Determination of Cadmium, Chromium, Cobalt, Copper, Lead, Manganese, Nickel and Potassium by Atomic Absorption Spectrometry. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1998. Available online: https://cdn.standards.iteh.ai/samples/24010/7d67c069009f4c999844d77b20e00e38/ISO-11047-1998.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Kulokas, M.; Praspaliauskas, M.; Pedišius, N. Investigation of Buckwheat Hulls as Additives in the Production of Solid Biomass Fuel from Straw. Energies 2021, 14, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 16948:2015; Solid Biofuels—Determination of Total Content of Carbon, Hydrogen and Nitrogen. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. Available online: https://cdn.standards.iteh.ai/samples/58004/c961056749c340a48a61976079c7aa9f/ISO-16948-2015.pdf (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- ISO 16994:2016; Solid Biofuels—Determination of Total Content of Sulphur and Chlorine. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/70097.html (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Praspaliauskas, M.; Pedišius, N.; Striūgas, N. Elemental Migration and Transformation from Sewage Sludge to Residual Products during the Pyrolysis Process. Energy Fuels 2018, 32, 5199–5208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz, J.M.; Cwalina, P.; Obidziński, S. A comprehensive study of buckwheat husk co-pelletization for utilization via combustion. Biomass Conv. Bioref. 2024, 14, 27925–27942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klintsavich, V.N.; Flyurik, E.A. Methods of use of buckwheat husband sowing (review). Trudi BGTU 2020, 1, 68–81. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/344905964_METHODS_OF_USE_OF_BUCKWHEAT_HUSBAND_SOWING_REVIEW (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Holodilina, T.N.; Antimonov, C.V.; Hanin, V.P. Research into the possibilities of increasing the nutritional value of buckwheat husks (Issledovanie vozmozhnostei povishenia pitatelnoi cennosti grechnevoi luzgi). Vestnik OGY 2004, 10, 153–156. Available online: http://vestnik.osu.ru/035/pdf/31.pdf (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Vojtíšková, P.; Švec, P.; Kubáň, V.; Krejzová, E.; Bittová, M.; Kráčmar, S.; Svobodová, B. Chemical composition of buckwheat plant parts and selected buckwheat products. Potravin. Sci. J. Food Ind. 2014, 8, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, T.; Morishita, T.; Kim, S.-J.; Park, S.-U.; Woo, S.-H.; Noda, T.; Takigawa, S. Physiological of Ruthin in the Buckwheat Plant. JARQ 2015, 49, 37–43. Available online: https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/jarq/49/1/49_37/_pdf (accessed on 6 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- Aligning the Circular Economy and the Bioeconomy at EU and National Level. Available online: https://www.eesc.europa.eu/en/our-work/opinions-information-reports/opinions/aligning-circular-economy-and-bioeconomy-eu-and-national-level (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Sofi, S.A.; Ahmed, N.; Farooq, A.; Rafiq, S.; Zargar, S.M.; Kamran, F.; Dar, T.A.; Mir, S.A.; Dar, B.N.; Khaneghah, A.M. Nutritional and bioactive characteristics of buckwheat, and its potential for developing gluten-free products: An updated overview. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 11, 2256–2276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lițoiu, A.A.; Păucean, A.; Lung, C.; Zmuncilă, A.; Chiș, M.S. An Overview of Buckwheat—A Superfood with Applicability in Human Health and Food Packaging. Plants 2025, 14, 2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Dong, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, J.; Wu, N. Changes in nutritional and antioxidant properties, structure, and flavour compounds of Tartary buckwheat (Fagopyrum tataricum) sprouts during domestic cooking. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2024, 36, 100914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 18122:2015; Solid Biofuels—Determination of Ash Content. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. Available online: https://cdn.standards.iteh.ai/samples/61515/605c1b011d6144d49b08566ec7a63521/ISO-18122-2015.pdf (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- ISO 18123:2015; Solid Biofuels—Determination of the Content of Volatile Matter. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. Available online: https://cdn.standards.iteh.ai/samples/61516/adf43f52f1fa4d15be9eb8f05e833d69/ISO-18123-2015.pdf (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- ISO 18125:2017; Solid Biofuels—Determination of Calorific Value. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. Available online: https://cdn.standards.iteh.ai/samples/61517/4fccd4123eb64aa4a3934a379744609c/ISO-18125-2017.pdf (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Somin, V.A.; Komarova, L.F.; Kutalova, A.V. Study of buckwheat husk application for water demineralisation. Izvestiya Vuzov. Prikladnaya Khimiya i Biotekhnologiya = Proceedings of Universities. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2020, 10, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olszańska, N.A.; Figiel, A.; Pląskowska, E.; Twardowski, J.; Gębarowska, E.; Kucharska, A.Z.; Łętowska, S.A.; Spychaj, R.; Lech, K.; Liszewski, M. Qualitative and quantitative assessment of buckwheat husks as a material for use in therapeutic mattresses. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siauciunas, R.; Valanciene, V. Influence of buckwheat hulls on the mineral composition and strength development of easily fusible clay body. Appl. Clay Sci. 2020, 197, 105794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Fletes, R.C.; Sadeghi, V.; González-Núñez, R.; Rodrigue, D. Effect of Surface Modification on the Properties of Buckwheat Husk—High-Density Polyethylene Biocomposites. J. Compos. Sci. 2023, 7, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostovoy, A.; Eremeeva, N.; Shcherbakov, A.; Lopukhova, M.; Ussenkulova, S.; Zhunussova, E.; Bekeshev, A. Sorption Activity of Oil Sorbents Based on the Secondary Cellulose-Containing Raw Materials of Buckwheat Cereal Production. Molecules 2025, 30, 2285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Chu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Ye, Y.; Zhao, B. Effect of Biochar Application on the Improvement of Soil Properties and Buckwheat Yield on Two Contrasting Soil Types in a Semi-Arid Region of Inner Mongolia. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumtaz, W.; Czarnowska-Kujawska, M.; Klepacka, J. Effect of Buckwheat Husk Addition on Antioxidant Activity, Phenolic Profile, Color, and Sensory Characteristics of Bread. Molecules 2025, 30, 3625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mumtaz, W.; Klepacka, J.; Czarnowska-Kujawska, M. Modification of Mineral Content in Bread with the Addition of Buckwheat Husk. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 4455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]