Abstract

This article examines the role of urban design in integrating biodiversity preservation with the enhancement of environmental and human health and quality of life in urban and peri-urban areas. Building on three complementary perspectives—urban design, the Healthy Habits framework, and socio-ecological networks—the review seeks to bridge short- to medium-term actions for improving the quality of life with long-term strategies for biodiversity preservation. While partial connections between these domains exist, they remain fragmented, underscoring the need for a holistic and transdisciplinary approach to urban socio-ecological health. The study employs a two-stage methodology, combining a scoping review to map existing evidence with a qualitative thematic review across SCOPUS-indexed research, European and international policy frameworks, and practical applications. The One Health paradigm is used as the principal integrative tool to link urban design, the Healthy Habits framework, and the socio-ecological networks. The topics of European environmental policies, evolutionary pillars, and social cohesion are incorporated to strengthen the interrelations between environmental and societal health and well-being. The findings highlight the importance of a holistic approach, behavioural insights, urban nudges, and participation, which can become key elements in fostering social cohesion, ecological resilience, and overall health. The research concludes that health-oriented urban design must go beyond traditional planning paradigms and tools, adopting adaptive, relational, and transdisciplinary approaches to address the challenges posed by contemporary times.

1. Introduction

The Natura 2000 network, throughout Europe, focuses on safeguarding biodiversity by maintaining natural resources (natural and semi-natural habitats, as well as wild flora and fauna) in a state of “satisfactory conservation”. There is a growing belief that biodiversity contributes to sustainability [1,2,3] and must be promoted and maintained, considering economic, social, and cultural needs and regional and local particularities.

The advances in ecology and conservation biology have already shown that the conservationist approach focused on individual threatened species does not yield effective conservation outcomes [4,5]. Conservation instruments, which for most species rely on protected areas, are insufficient to halt biodiversity loss and thus call for conservation initiatives on the broader landscape surrounding protected areas [6]. Therefore, it is necessary to operate within a network vision, in which human activity itself, if well-designed, can help preserve biodiversity. However, the complex interconnections among living beings and their environments must be considered.

Natura 2000, as a network concept, enters a logic of sustainability by recognising that a series of human (traditional agricultural) activities are even indispensable for the protection of biodiversity [7] and that the depopulation and abandonment of areas are anything but beneficial to the conservation of natural and very often semi-natural habitats [8]. Also, the well-being and health of the inhabitants depend on the environmental conditions of the open green spaces and the city [9]. In this interrelation between the quality of biocenoses—groups of interacting organisms living in a particular habitat and forming a self-regulating ecological community—and the quality of life, the Natura 2000 Network takes on particular importance when nature meets inhabited spaces.

All this revolutionises the approach to the management of Natura 2000 Sites and the entire territory, opening the need for exploring new connections between the various disciplines involved in urban planning and design that improve the quality of life and well-being of ecological and social communities. Therefore, it is necessary to radically reconsider the interrelations between the living spaces of plants, animals, and humans, to reconcile the improvement of the biocenoses of a geographical area at the same time as the increase in the quality of life and health of the inhabitants of that same geographical area [10].

The current body of knowledge is examined to demonstrate interrelation intensities among urban planning, the Healthy Habits framework, and socio-ecological networks. The integration of urban design and socio-ecological networks is identified in community gardens and urban green spaces that function simultaneously as ecological nodes, supporting biodiversity and ecosystem services, and as social nodes, enhancing social cohesion and interaction [11,12]. Frameworks such as One Health [13] and the Virtuous Cycle [14] explicitly link urban planning with socio-ecological processes, highlighting participatory planning and justice-oriented processes as critical mechanisms for integration. Design elements of urban form, such as density, accessibility, and walkability, are operationalised in frameworks like the Eight Dimensions (8Ds) [15] and the Walkability Measurement [16], showing context-dependent relations between regional planning and urban design to functions of urban networks in creating healthy and sustainable cities. Research on interactions between urban design and socio-ecological networks reports trade-offs (e.g., compact design may reduce green infrastructure) [13] and highlights synergies (e.g., regenerative approaches align social and ecological objectives) [17].

Socio-ecological networks such as green spaces, parks, and walkable environments are associated with increased physical activity, reduced stress, enhanced mental health, and improved social cohesion [18,19,20] as indicators of human health and well-being. Subjective perceptions of urban green spaces, such as perceived safety and aesthetic quality, play a key role in whether residents adopt health-promoting behaviours [20]. Also, socioeconomic status and community engagement emerge as moderating factors that affect access to healthy environments and behaviours [21], thus underscoring the necessity for urban planning policies to adopt an inclusive approach [22]. Participatory approaches and community involvement in planning and management [14,19] effectively align socio-ecological structures with health needs.

The influence of urban design features such as walkability, mixed land use, and green infrastructure is linked to human health and Healthy Habits behaviours [18,19], as supported by frameworks such as the Park Network Index [23] and Salutogenic Urban Design [24]. However, some studies on urban form and green infrastructure [13,25] point to adverse or mixed effects in high-density environments, where benefits to human health through walkability and social ties may coexist with reduced access to green spaces and potential isolation.

Examining the interrelations between urban design, the Healthy Habits framework, and socio-ecological networks, the thematic literature review reveals integration of urban design and socio-ecological networks, the impact of socio-ecological networks on human health, and the influence of urban design on human health. Although some of the reviewed frameworks, such as One Health [13], the Eight Dimensions (8Ds) [15], and Salutogenic Urban Design [24], illustrate that the integration of socio-ecological networks and well-planned urban structures reinforces health-promoting behaviours, the holistic interrelation is missing. The current body of knowledge lacks an integrated and systemic understanding of how urban form, socio-ecological networks, and public health outcomes co-evolve and influence one another in shaping social well-being and ecosystem health. This absence of a holistic perspective represents a critical research gap, particularly given the increasing complexity of urban socio-ecological systems. This research gap is evidenced in the prevailing tendency in scholarly and policy discourse to address human health separately from the health of animals, plants, and ecosystems [26]. To address this fragmentation, this review brings together interdisciplinary expertise from urban planning, public health, and urban sociology—disciplines essential for the sustainable management of urban environments, integrating socio-ecological networks and the Healthy Habits principles of its inhabitants. Such integration and holistic understanding are crucial for shaping urban life, which equally supports both human well-being and ecosystem health.

The methodological approach combines a scoping review of scientific bases with a thematic review across urban planning, public health, and sociology disciplines, converging on three complementary perspectives to provide additional knowledge on human well-being, ecosystem health, and sustainability in urban and peri-urban areas. To advance a more holistic understanding of these interrelations, the thematic review is structured around three complementary topics:

- the evolution of European environmental policies influencing urban planning and the design of public green spaces for human and environmental health (urban planning perspective);

- designing healthy cities with the Healthy Habits framework: a One Health model grounded in four evolutionary pillars (public health perspective);

- urban systems and social interaction for healthy cities: the outdoors generating healthy social networks (sociological perspective).

In conclusion, the findings underscore that the effective management of urban green spaces, in conjunction with supportive human behaviours, can significantly enhance public health and increase biodiversity. These outcomes align with the objectives of the main European strategies aimed at fostering sustainable, resilient, and health-promoting urban environments.

2. Methods and Materials

The literature review adopts a two-step methodological approach: (i) an initial scoping review to set the state-of-the-art and identify research gaps in the interrelation of urban design, Healthy Habits, and socio-ecological networks, followed by (ii) a thematic review to deepen the interrelation analysis of these three perspectives within their disciplines of urban planning, public health, and sociology. This interdisciplinary approach, which combines quantitative and qualitative research, facilitates the identification of key patterns and conceptual overlaps that support an integrated understanding of urban socio-ecological health. By structuring the analysis through three complementary perspectives, the review synthesises insights that are often treated separately.

2.1. The Scoping Review

The scoping review was conducted with the aim of synthesising scientific evidence on how urban design, socio-ecological networks, and the Healthy Habits framework interact to influence human and environmental well-being in urban settings. The review applies a semantic-search approach using Elicit [27], which leverages large-scale language models to identify relevant publications through meaning-based retrieval, rather than keyword matching. Elicit, an AI-based scientific research assistant, indexes academic papers from Semantic Scholar, PubMed, and OpenAlex. The scoping review was conducted in three stages: (i) initial identification, (ii) screening and eligibility, and (iii) refinement, data synthesis, and thematic analysis (Table 1).

Table 1.

Methodological approach of the scoping review.

The initial identification was carried out using Elicit by applying the research question: “What are the interactions between urban design, socio-ecological networks, and the Healthy Habits framework in shaping the quality of life for humans and the environment across different urban contexts?” For the requested timeframe of the literature review, from 2010 to 2025, Elicit returned 499 results ranked by semantic proximity.

In the second step, abstracts and metadata of each paper were screened against inclusion and exclusion criteria to confirm the eligibility of 486 papers. Screening criteria of inclusion involve:

- urban setting—study conducted in an urban, suburban, or peri-urban context;

- quality-of-life outcomes—including analysis of both human and/or environmental well-being indicators;

- multi-dimensional scope—investigation of at least two of the three systems—urban design, socio-ecological networks, Healthy Habits related concepts;

- empirical or systemic research—peer-reviewed empirical research, systematic/scoping review, or validated conceptual framework;

- community or spatial scale—intervention or observation at neighbourhood, district, city, or metropolitan level;

Screening criteria of exclusion involve:

- studies conducted in non-urban and rural settings;

- missing evidence base—opinion pieces or editorials;

- missing systemic perspective—missing explicit link between urban design, socio-ecological networks, and health;

- no quality of life or well-being outcomes.

From the initially retrieved papers that met the screening criteria of inclusion and exclusion, 40 studies with the highest screening scores were processed for data extraction and synthesis. For each of the 40 included papers, the Elicit was instructed to extract and tabulate the following dimensions: urban design framework; socio-ecological networks; health-related frameworks; quality of life measures (both human and environmental indicators); urban context; interaction mechanisms; study design (methodology); and key findings. Data were automatically summarised by Elicit and manually verified for coherence and relevance. Further data synthesis and thematic analysis were conducted based on extracted evidence, following PRISMA-ScR guidelines. Patterns were identified across the following interaction types: urban design ↔ socio-ecological networks; socio-ecological networks ↔ healthy habits; and urban design ↔ healthy habits, to set the state-of-the-art and identify research gaps. Results were mapped according to human and environmental quality-of-life outcomes, summarised and discussed in conceptual matrices.

2.2. The Thematic Review

The initial insights provided by the Elicit scoping review were further refined through a qualitative thematic review of three complementary thematic perspectives of urban design, the healthy habits framework, and socio-ecological networks. The thematic review was conducted within urban planning, public health, and sociology disciplines, exploring the interactions between thematic perspectives through the connections between theoretical frameworks and practical applications. The theoretical framework of relevant academic studies was collected from the SCOPUS database, ensuring comprehensive coverage of peer-reviewed research. Additionally, policy documents from the European Commission, the Council of Europe, and the United Nations were reviewed to integrate policy frameworks and strategic directives with scientific evidence.

The theoretical framework is further strengthened through the integration of practical examples, which are explored within a timeframe aligned with the thematic review. The first thematic contribution associates European environmental policies with a holistic vision of urban planning and design, exploring the interactions between different sectoral contents of ecology, urban planning, health, and participation. The evolution of European environmental policies is examined, beginning with the first international and European conferences and policy documents on environmental protection in the 1970s. The second thematic contribution explores how the Healthy Habits (HH) framework, originally developed as a preventive and holistic approach, grounded in the One Health paradigm, with its four evolutionary pillars (physiology, psycho-relational well-being, nutrition, and environment), can inform urban planning and design strategies. The third thematic contribution was achieved by proposing a review of sociological approaches that have sought to understand cities as complex and interconnected systems, partly because of the development of information flows. The space of places has been flanked, or replaced, by the space of economic, cultural, political, and information flows, creating the conditions for the activation of new health connections linked to ecological and natural networks.

This combined research approach (Table 2) supports a more holistic understanding of how the three thematic domains intersect and enhance existing knowledge on urban socio-ecological networks. A comprehensive review highlights the points of contact between actions to improve environmental conditions and to raise the quality of life for healthy cities.

Table 2.

The structure of the thematic review on the interactions of urban design, socio-ecological networks, and the healthy habits framework.

3. The Evolution of European Environmental Policies Influencing Urban Planning and the Design of Public Green Spaces for Human and Environmental Health

Environmental protection is one of the significant global challenges of the twenty-first century and a political priority for the European Union, which considers it an integral part of its sustainable development. Since the 1970s, following the Stockholm Conference on the Human Environment [28], the European Union has progressively evolved its strategies to incorporate the environment into all sectoral policies, thereby influencing urban planning and design and addressing human health.

The Stockholm Declaration of the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment, which was the first world conference to make the environment a major issue, was initiated with a proclamation: ‘Man is both creature and moulder of his environment, which gives him physical sustenance and affords him the opportunity for intellectual, moral, social and spiritual growth’. This proclamation embodies two, often conflicting visions of anthropocentrism (human-centred) and ecocentrism (nature-centred), thus paving the way towards a holistic vision of the environment that is reflected in the means of planning and design of urban and peri-urban landscape. The anthropocentric vision considers the environment essential to the extent that it serves humanity, while ecocentrism values nature for its own sake [29]. These two opposed visions of the environment have led to a separatist vision of society and nature in the twentieth century. A more complex understanding, marked in the Stockholm Declaration, recognises the interconnection between humanity and nature as well as the holistic vision of the environment necessary for a fair and sustainable future, in which human well-being is achieved not at the expense of the planet, but in harmony with it.

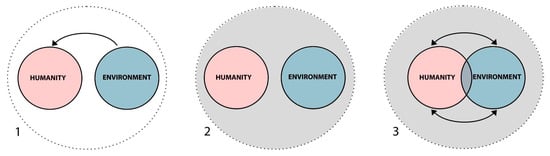

The fundamental steps in the evolution of European environmental policies are retraced with the aim of identifying opportunities for enhancing the integration of a holistic dimension into the planning and design of public green spaces, focusing on the interdependence of human and environmental health in urban and peri-urban areas. The three phases in the evolution of European environmental policies: (i) distinguishing man from nature: 1970–1987; (ii) integrated vision: 1987–2006; (iii) towards systematic and holistic vision: from 2007, are reviewed in relation to representative urban planning and design practices (Table 3) and the change in consideration of human and environmental health (Figure 1).

Table 3.

Overview of the European environmental policies related to urban planning and design practices of the public green spaces, influencing human and environmental health.

Figure 1.

The change in consideration of human and environmental health in the evolution of European environmental policies. First phase (1) distinguishes humanity and nature by seeing environmental protection as a defence of humanity. Second phase (2) considers both human and environmental health through sustainable development. Third phase (3) streams towards awareness of the interdependence of human and environmental health as a single system.

3.1. Distinguishing Man from Nature: 1970–1987 Humanity and Nature as Distinct Entities—Environmental Protection as a Defence of Humanity

The evolution of European environmental policies can be primarily followed through a series of Environmental Action Programmes (EAP) that were inaugurated after the Stockholm Conference [28]. The 1st EAP aimed to improve the setting and quality of life, as well as the surroundings and living conditions of the people. This rationale was sectoral, focusing on pollution reduction and nature protection, as planned actions aimed to limit the environmental damage caused by urban and industrial development. The Bern Convention further enhanced nature protection, an innovative biodiversity convention adopted in 1979, through the approach of protecting both species and habitats, as well as recognising the intrinsic values of wild flora and fauna [30]. The following EAP-s introduced the preventive approach that required economic and social developments to be undertaken in such a way as to avoid the creation of environmental problems. Even though the first EAP-s demonstrated integrating environmental requirements into many economic and social sectors, the environment was still considered an external entity to humanity.

The evolution of environmental policies in Europe was closely aligned with the establishment of the United Nations Environment Programme, as reflected in the Limits to Growth debate [31]. The international policy documents of the 1970s, such as the UNESCO Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage [32], which primarily focused on identifying and listing heritage sites of ‘outstanding universal value’, demonstrated the perception of humanity and nature as distinct entities. Yet, the UNESCO Man and Biosphere Programme (MAB), established in 1971, aims to provide a scientific basis for enhancing the relationship between people and their environments, thus opening a sustainable development perspective.

The topics opened by the evolution of European environmental policies were reflected in urban planning and design projects for public green spaces in the 1970s and 1980s—especially limiting the environmental damage caused by urban and industrial development, the need for landscape in the transformation of industrial areas, and the development of ecological criteria. This initiation phase coincided with the onset of the post-industrial shift in Europe, characterised by a decline in manufacturing and a corresponding rise in the service sector. From the 1970s, numerous landscape planning and urban development projects referred to the ecological, economic, and cultural renewal of the former industrial region as well as the transformation of former industrial sites into public green spaces, like IBA Emscher Park in the central Ruhr region and projects Parc de La Villette and Parc André-Citroën in Paris. The development of ecological criteria was also followed in urban planning, where the New Urbanism movement [33] promoted urban visions and theoretical models for reconstructing the “European” city, involving the conservation of natural resources and the preservation of environmental health.

The initial phase of European environmental policy evolution reflected a human-centric approach, where the environment was protected based on human needs, without effective integration between social and natural systems. This perception of humanity and nature as distinct entities was manifested in environmental protection as a defence of humanity, limiting the environmental damage caused by urban and industrial development, as well as improving the setting and living conditions as a base for the health and well-being of people. Landscape and urban planning projects and movements from the 1970s introduced social revitalisation and the integration of nature into the urban environment, thus opening a sustainable perspective on development that led to a higher awareness of the integrated vision of environmental and human health in the late 20th century.

3.2. Integrated Vision: 1987–2006 the Environment Becomes Part of Sustainable Development

The Brundtland Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development, entitled Our Common Future, marked a new phase in both international and European environmental policies by adopting the concept of sustainable development. The ability of humanity to make development sustainable means ‘to ensure that it meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs’ [34], thus paving the way for an integrated vision of economic, social, and environmental policies. The UN Conference on Environment and Development in Rio in 1992, known as the ‘Earth Summit’, established the concept of sustainable development as a global goal, resulting in the Agenda 21 action programme, the UN Convention on Climate Change, the Convention on Biological Diversity, and the Declaration on the Principles of Forest Management. Further evolution of the sustainability concept was marked by the Kyoto Protocol [35], an international treaty aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions, and the Millennium Development Goals, which aligned respect for nature with fundamental values such as freedom, equality, solidarity, tolerance, and shared responsibility, all essential in the twenty-first century.

The 4th EAP laid the foundation for the transition towards ‘sustainable development’ as a central principle, incorporating environmental protection into all relevant EU policies to integrate with economic growth and job creation in Europe. With the Maastricht Treaty [36], the European Union officially integrated the environment into all sectoral policies, with the objectives of preserving, protecting, and improving the quality of the environment; protecting human health; and ensuring prudent and rational use of natural resources. In this context and by strengthening the EU commitment to the Bern Convention on the Conservation of European Wildlife and Natural Habitats [37], a new approach to environmental protection emerged, based on the coexistence of biodiversity conservation and human activities within the Natura 2000 Network. Two key instruments: (i) the Birds Directive [38], which protects all wild bird species, and (ii) the Habitats Directive [39], together establish the Natura 2000 Network as a European ecological system of protected areas and promote active and participatory land management, reconciling conservation and local development. At the change of the millennia, the scope of policies contributing to environmental protection in Europe, further expanded by, the Council of Europe Landscape Convention [40] that addressed all landscape (outstanding, every-day, and degraded) and the whole of the environment as valuable, and culminated with the EU Strategy for Sustainable Development [41] that affirmed the environment, economy, and society as part of a single system that must ensure equity, quality of life, and ecological protection.

The integrated vision of environmental and human health in European environmental policies at the turn of the millennium was marked by the concept of sustainable development, which promoted economic, social, and environmental sustainability. This was in line with the accelerating post-industrial shift, marked by the growth of science-based industries and the advent of the information age. The landscape and urban planning projects of the time continued the transformation and renewal of former industrial sites through the integration of social revitalisation and nature into the urban environment, like Landschaftspark Duisburg-Nord, Duisburg, and Alter Flugplatz Kalbach, Frankfurt am Main/Bonames, in Germany, and Parc de Bercy, Paris, and Louvre Lens Museum Park, Lens in France. The step towards sustainability was also evident in urban planning and design theories and practices, as Landscape Urbanism emerged as a response to the perceived limitations of traditional urban planning and design approaches [42]. It is a(n) (inter)disciplinary theory that prioritises the landscape as the basic medium of constructing contemporary cities [43,44] and gives a response to urban planning and design challenges—ecological and economic value to sites of stalled development, collaboration across disciplines and communities, and an authentic landscape response of urban identity that arises from the metaphysical side of landscape. The approach of Biophilic cities promotes the integration of nature into urban design and planning [45].

The change of the millennium was characterised by the plurality of urban planning and design theories, approaches, and concepts that influenced the shaping of the urban environment to an extent greater than the individual landscape and urban planning projects. Re-Urbanism is oriented towards constant urbanity; Green Urbanism is focused on ecological sensitivity; New Urbanism is based on a neighbourhood concept and walkability; Post-Urbanism, as a generic hybridity, is concentrated in reinvention and restructuring; Everyday Urbanism promotes vernacular spatiality with a bottom-up approach [46]. These urban planning approaches, varying in intensity, integrate environmental and human needs and are rooted in sustainable development that balances economic prosperity, social equity, and environmental protection.

3.3. Towards Systematic and Holistic Vision: From 2007 Humans and the Environment Belong to a Single System

With the Treaty of Lisbon [47], the European Union has adopted a holistic and interconnected approach to the environment, thus identifying the inextricable link between nature, human well-being, the economy, and society. This represents the definitive overcoming of the sectoral approach of the past: the environment is no longer an isolated area, but a cornerstone of public policies, including in urban, agricultural, and industrial contexts. By adopting the EU Biodiversity Strategy [48], the Commission committed to developing a Green Infrastructure Strategy [49] to enhance Europe’s natural capital and give proper value to ecosystem services. The Strategy defines green infrastructure as a tool for providing ecological, economic, and social benefits through natural solutions, which drive towards innovative, sustainable, and inclusive growth.

The UN Conference on Sustainable Development in Rio, in 2012, was framed around the concept of ‘green growth’ and set in motion the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [50]. The holistic vision of people and environment finds full expression with the adoption of the United Nations 2030 Agenda, whose Sustainable Development Goals have been integrated into EU strategies. A decisive step forward in achieving Sustainable Development Goals, as well as strengthening the EU commitment to the Kyoto Protocol from 1997, is the European Green Deal [51], the EU’s strategy to achieve climate neutrality by 2050. The Green Deal extends beyond climate mitigation, encompassing public health, the circular economy, sustainable agriculture, green mobility, biodiversity protection, and social justice, to achieve systemic transformation. The recent EAP-s supports the EU’s long-term vision of living well and within the limits of our planet by building upon the European Green Deal. The emphasis on climate action of the European Green Deal and the EU Strategy on Adaptation to Climate Change [52] aligns with the shift in international environmental policies towards addressing climate change [34]. The most recent EU environmental policy is the Nature Restoration Law [53], which further strengthens the integrated approach by introducing the binding environmental restoration obligations for terrestrial and marine ecosystems, including agricultural and urban ones. With these actions, the European Union adopts a systemic vision in which humans are an integral part of ecosystems, and the environment is recognised as a fundamental condition for the future of European society.

The synergy of environmental protection and sustainable development, supported by frameworks such as the UNESCO Man and Biosphere Programme, the Ramsar List of internationally important wetlands, and the UNESCO Global Geoparks Network, is in the twenty-first century further focused on urban areas. The network approach of the UNESCO frameworks is utilised in urban contexts, through the European Commission’s Green City Awards, which include two titles: the European Green Capital (EGC) for cities with over 100,000 inhabitants and the European Green Leaf (EGL) for smaller cities with 20,000 inhabitants. These awards for best practices in sustainable urban development [54] recognise local actions towards a transition to a greener future and an improvement in the quality of life and environment. After London became the first National Park City in 2019, the National Park City Foundation [55] was established, aiming to provide a vision and a city-wide community that is acting together to make life better for people, wildlife, and nature. The initiatives focusing on making cities more sustainable and climate-resilient involve the European partnership Greening Cities under the EU’s Urban Agenda, as well as the international partnership Greener Cities, led by the UN Environment Programme (UNEP) and UN-Habitat.

These frameworks, awards, foundations, and partnerships in synergy with environmental protection and urban planning, represent the contemporary network approach to addressing urban environmental challenges and advancing climate-resilient, inclusive, and healthy urban communities. Impacts are achieved through increased citizen participation, enhanced urban biodiversity, and the application of blue and green infrastructure and nature-based solutions. The long-term vision of Europe, which is built upon the European Green Deal, promotes a model in which the environment, economy, and social cohesion are sustainable, equitable, and interdependent. Therefore, Europe aims to accelerate the transition to a climate-neutral and resource-efficient economy, recognising that human well-being and prosperity depend on healthy ecosystems.

3.4. Holistic Vision of the Relationship Between Society and Environmentinterdependence of Environmental and Human/Societal Health

The critical views on dominant growth paradigms, which also include sustainable development and green growth, originate from the Limits to Growth model [56,57]. Made fifty years ago, but still prominent today, Limits to Growth analyses the world economy’s environmental relations and the ability of technology to decouple economic growth from ecological collapse [31]. While the Limits to Growth reflected the rise to international prominence of environmental issues in the 1970s with the Stockholm Conference on the Human Environment and the United Nations Environmental Programme, contemporary urban planning opened the ideas of post-growth [31,58] and degrowth [59,60,61,62] to address eco-social transition and climate emergency. The alternatives to the growth paradigm are also asked by the planetary boundary framework, introduced in 2009, that aims to define the environmental limits within which humanity can safely operate [63,64,65]. In the current situation, where the Earth is already well outside the safe operating space for humanity [66], the achievement of global sustainability will largely be determined by cities as drivers of culture, economy, material use, and waste generation [67,68]. The planetary boundaries concept has profoundly changed the vocabulary and representation of global environmental issues by introducing societal boundaries [69], ecological democracy [70], and environmental justice [71]. Strategies to improve both socio-economic and biophysical systems equally, with a focus on sufficiency and equity, have the potential to advance global sustainability and achieve a good life for all within planetary boundaries [72]. Going beyond sustainable development and green growth towards post-growth and degrowth, acknowledge interdependence and mutual creation of healthy environments and healthy societies within planetary boundaries.

A pioneer of critical complexity theory, Edgar Morin [73], stated, ‘Humanity cannot be explained without culture, but culture cannot be explained without nature’, effectively summarising a holistic vision of the relationship between man and the environment. This perspective transcends classical dualisms, inviting us to view the world through a complex and interrelated lens, where nature and culture continually interact. From the 1972 Stockholm Conference on the Human Environment, which attempted to lay the foundations for a holistic vision in future European environmental policies, it was not until 2015, with the United Nations 2030 Agenda, that this vision materialised. The evolution of European environmental policies shifts from a separatist vision of humanity and nature to a sustainable and holistic perspective. Still, the historical separation between the environment and urban areas continues to influence the way policies are implemented, especially in medium-sized and small cities. Although the relationship between environmental policies and their implementation in urban planning and design practices has evolved in a non-linear manner, the shifting environmental paradigms have influenced the way urban and peri-urban spaces are shaped and developed. Contemporary approaches increasingly emphasise the integration of environmental protection and sustainable development, promoting a holistic vision that links ecological integrity with human health and well-being. In this context, the health synergy of ecological and societal networks, which continuously influence one another and co-evolve with urban environments, is conceptually reinforced and further examined through the One Health framework.

4. Designing Healthy Cities with Healthy Habits: A One Health Model Grounded in Four Evolutionary Pillars

The Healthy Habits (HH) approach represents an evidence-based preventive health framework grounded in the One Health paradigm and structured around four interdependent evolutionary pillars: physiology, psycho-relational well-being, nutrition, and environment. Conceived to monitor and enhance core daily practices as a means to enable effective primary prevention, these four pillars originate from the conceptual foundation of the Healthy Habits (HH) approach. This evidence-based framework has been empirically validated through real-world applications in schools, workplaces, and communities. Rooted in epigenetic and preventive health science [74], the HH model aligns fully with the One Health strategy by integrating biological, social, and ecological determinants of well-being.

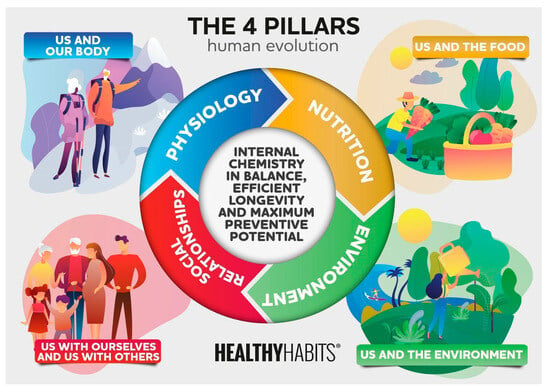

The Four Pillars of Human Evolution (Figure 2, Table 4) represent the systemic architecture of the HH framework, where physiology, psycho-relational well-being, nutrition, and environment function as interconnected feedback systems maintaining internal and external balance. The circular composition symbolises the co-evolution between biological, social, and ecological processes that sustain life and health as a dynamic equilibrium.

Figure 2.

The Four Pillars of Human Evolution representing the Healthy Habits framework.

Table 4.

Structural Matrix: “The Four Pillars of Human Evolution”.

Each of the evolutionary pillars (Figure 2) can be translated into an operational framework (Table 4), by linking each evolutionary pillar to specific urban-design levers, health mechanisms, and measurable indicators. Establishment of these connections reinforces the empirical foundation of the Healthy Habits approach and illustrates how the four pillars can be practically applied within One Health-oriented urban planning.

Rather than addressing individual behaviour change in isolation, HH promotes the ecological redesign of everyday environments—homes, schools, workplaces, and cities—to foster health across biological, psychological, and social domains [74]. Epigenetic research confirms that lifestyle and environmental factors can modulate gene expression, thereby influencing disease risk, systemic inflammation, and homeostatic balance throughout the life course [74].

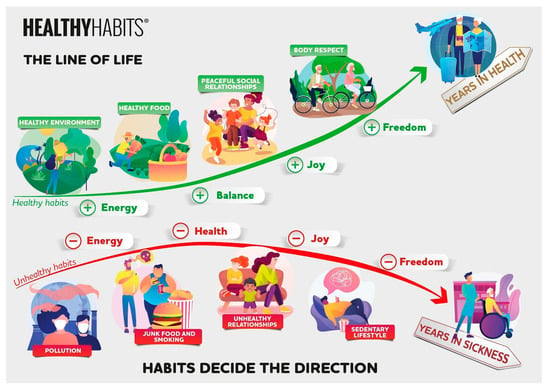

‘The Line of Life’ (Figure 3) as a longitudinal trajectory of human functionality and vitality, shows how everyday habits can progressively influence health outcomes across the life course. The concept visually captures the dynamic balance between positive and negative lifestyle patterns and their cumulative biological, psychological, and social effects. The main environmental and behavioural determinants that shape the upward or downward trajectories in the ‘Line of Life’ (Table 5) are linked to measurable outcomes in health and well-being, illustrating how positive and negative feedback loops influence human functionality over time. These provide a practical interpretation of how daily habits interact with environmental quality, nutrition, social relations, and physiology to determine long-term public health trends. Together, these relations establish the systemic basis of the HH framework, from which the ‘Line of Life’ (Figure 3) develops the dynamic dimension of human vitality and its evolution over time.

Figure 3.

‘The Line of Life’ illustrates that the upward curve corresponds to balanced routines that generate energy, joy, and longevity, whereas the downward curve depicts the cumulative effects of unhealthy behaviours such as a sedentary lifestyle, stress, and poor nutrition.

Table 5.

Interpretive Matrix: “The Line of Life” Infographic.

Collectively, these insights (Figure 3 and Table 5) provide a dynamic interpretation of how the four pillars interact within real contexts, linking daily behaviours to measurable health outcomes. The case study from the Republic of San Marino exemplifies how the HH framework can be effectively implemented at a systemic level through coordinated educational and environmental interventions. A real-world application of the HH model was implemented in all public primary schools in the Republic of San Marino during the 2022–2023 academic year. Coordinated by the national health and education authorities, the programme reached 13 school sites through a structured seven-month intervention. Key components included 40 h of teacher training, experiential activities for children, weekly multimedia content for families, environmental redesign (such as green spaces and movement zones), and co-created school routines.

Initial qualitative assessments—gathered through structured questionnaires and direct observation—revealed notable behavioural shifts: increased outdoor play, better breakfast quality, reduced intake of processed foods, and greater emotional awareness. As emphasised by Dr. Arianna Scarpellini, Principal Primary School, “the most important result was that children themselves became the drivers of change at home” [75].

Quantitative validation came from the 2023 national application of the OKkio alla Salute surveillance system, following WHO-COSI protocols. The results, based on 100% coverage of third-grade students, revealed a decrease in obesity prevalence from 7.7% to 5.3%, and in overall excess weight (including overweight and obesity) from 30.3% to 20.8% compared to the previous cycle [76]. Notably, the WHO Europe COSI Round 6 Report ([77], p. 42) identified San Marino as the only participating country to have registered a statistically significant reduction in childhood obesity among boys between Rounds 5 and 6.

Although causality cannot be formally established due to the lack of a control group, the convergence of programme coverage, absence of other interventions, and alignment with behaviour change theory support interpretation as a “natural experiment” [77,78]. The San Marino case illustrates how system-level health improvements can occur within a short timeframe when environments are designed to align with human biology, emotions, and habit formation.

This experience resonates with major policy frameworks, such as the European Green Deal and the EU Nature Restoration Law, which call for the integration of biodiversity, health promotion, and social equity into urban design. The HH approach—through light, low-cost interventions—provides a practical, evidence-based pathway to advance these goals in both cities and schools.

Further scientific validation of the HH pillars comes from a landmark study conducted by the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, which built upon two extensive studies spanning multiple decades: the Nurses’ Health Study (n = 78,865) and the Health Professionals Follow-up Study (n = 44,354). Researchers identified five key healthy behaviours—non-smoking, normal BMI, regular physical activity, moderate alcohol intake, and a healthy diet—as predictors of longevity. At age 50, women who followed all five behaviours lived 14 years longer, and men 12 years longer, than those who followed none [79,80,81]. Taken together, these findings reinforce the HH approach as a scientifically grounded, scalable, and policy-relevant framework for embedding health into the daily lives of children, families, and communities.

4.1. The First Pillar: Physiology

Physical activity can be either spontaneous or organised, and is generally categorised into three or four types, each producing distinct but equally beneficial outcomes. These benefits are particularly relevant for promoting the future health of both children and older adults, as they help to support healthy development and active ageing.

Some activities are indicated, for example, to improve muscle trophism, others for cardiovascular health, and still others for flexibility and balance. Facilitating the practice of these activities is possible. Behavioural economics shows us the way through the wise use of various ‘gentle nudges’. The Nudge theory [82], which won Richard Thaler the Nobel Prize, demonstrates how much more effective it is to stimulate healthy habits by preparing the context correctly than to try to convince through teachings or prohibitions. Finding equipped parks within walking distance from home, where we can do simple gymnastic exercises or having paths in the green where we can walk safely are two simple but effective interventions to increase the likelihood of practicing physical activity.

Another essential element for our physiology is to create the best conditions for a restful night’s sleep at home. A lack of sleep or its poor quality is, in fact, conducive to an increase in chronic silent inflammation [83,84,85], a significant enemy of human health. Resting in the dark, in silence, and without a substantial presence of disturbing elements (such as alarm clock radios or mobile phones kept charging on the bedside table) facilitates better rest with regenerative capacities and its decisive anti-inflammatory action.

4.2. The Second Pillar: Psycho-Relational Well-Being

The relevance of psycho-relational well-being has become a more recent focus within scientific research; nevertheless, the literature is continually expanding with new studies that underscore its critical role in supporting human health. After all, the importance of relationships and their role within society had already emerged as a common factor even in the famous ‘blue zones of the world’, the areas where the highest levels of longevity are reached. Feeling accepted, loved, and valued plays a crucial role in maintaining good health. The Harvard Grant Study, initiated in 1938 [86], also confirmed that stable emotional relationships are the primary determinant of human happiness and correlated with healthy longevity.

Designing urban spaces to foster social interaction among older adults can significantly support healthy ageing. Features like benches, tables, and shaded areas enable people to meet, converse, play cards, and engage in light physical activities. When coordinated by trained staff, these spaces encourage consistent participation and strengthen community ties. Structured social engagement has been shown to have numerous health benefits for seniors.

A case is the Frome Medical Practice in England, which adopted an integrated model of enhanced primary care and community support. By combining medical care with social prescribing and community-building initiatives, the programme achieved a 17% reduction in emergency hospital admissions within one year [87]. This highlights the preventive value of socially inclusive urban design, particularly when integrated with coordinated health and community strategies.

Strong social relationships also correlate with lower rates of depression and premature death. As social beings, isolation can be deadly—loneliness is a key predictor of early mortality [88,89]. Keeping older adults connected is a public health imperative. Equally essential to physiological well-being is creating optimal conditions for sleep at home. Poor or insufficient sleep is associated with increased chronic, low-grade inflammation, a driver of many non-communicable diseases and a significant public health concern [84]. Restorative sleep is promoted by limiting nighttime disturbances. Darkness, silence, and avoiding devices like phones or alarm clocks near the bed can all improve sleep quality. In turn, better sleep supports the body’s regenerative and anti-inflammatory functions, contributing to long-term health and disease prevention.

4.3. The Third Pillar: Nutrition

Nutrition is a key determinant of health across the life course, with both undernutrition and overnutrition contributing to disease burden. Since the mid-20th century, dietary quality has declined amid the rise of processed and ultra-processed foods, which are high in sugar, salt, and artificial additives. At the same time, access to fresh and diverse foods has become increasingly limited, especially in large metropolitan areas, contributing to reduced dietary biodiversity and weakened gut microbiota—factors closely linked to immune function.

Urban food environments—the physical, social, and economic settings in which people acquire and consume food—are powerful levers for dietary transformation. Municipalities can take a proactive role by: supporting farmers’ markets and km-0 outlets; developing community gardens and edible landscapes; planting fruit trees in public areas; facilitating solidarity-based purchasing groups (e.g., GAS (Solidarity-based Purchasing Groups—from the Italian “Gruppi di Acquisto Solidale”), coops, short supply chains). In addition, dedicated food education zones—such as the “Maestri di Bottega” programme in Italy’s Marche region—can combine retail access with nutritional education and biodiversity awareness. These approaches not only improve access to nutritious foods but also empower consumers to value imperfection, recognise the nutritional value of non-standard produce, and reduce food waste.

Finally, nutrition plays a fundamental role in modulating chronic low-grade inflammation, a biological mechanism shared across numerous non-communicable diseases [38]. Promoting food literacy and equitable access to healthy food is a public health priority with long-term impact.

4.4. The Fourth Pillar: The Environment

The physical environment—understood as the ensemble of buildings, their colours, their level of maintenance and care, the layout of streets, and the presence of greenery—can significantly influence our hormonal system and overall well-being. Scientific research shows, for example, that living in cities with abundant green spaces allows our telomeres—segments of DNA that serve as accurate biosensors of cellular ageing—to shorten at a slower rate, which corresponds to slower biological ageing [90].

However, there is growing evidence confirming the importance of greenery for human health. Trees absorb pollutants, filter the air, and provide cooling—three essential functions for public well-being [91]. They also serve as barriers against noise, purify the air by capturing various pollutants, including hazardous fine particulate matter (PM10 and PM2.5), and provide shade, which helps moderate temperatures. This is particularly beneficial for vulnerable populations who are more affected by urban heat islands, where paved surfaces can reach temperatures as high as 40–50 °C, compared to the 20 °C typical of vegetated areas.

The benefits of living in close contact with nature, however, extend far beyond these aspects. Coniferous trees such as pines and firs—as well as ferns, shrubs, and grasses—release volatile organic compounds known as terpenes. These substances have been shown to exert calming effects on the human nervous system by reducing levels of stress hormones such as cortisol. In fact, this mechanism has been formally recognised in some countries as a health intervention under national healthcare systems, through practices like forest therapy [90,92].

Furthermore, the presence of urban greenery has been consistently associated with increased happiness among citizens. A systematic review of over 57 studies conducted between 2013 and 2023 across 21 countries confirmed this association, although with some regional variations—particularly in South American contexts [93].

Living in close contact with nature—or within 300 to 500 metres of green parks—is associated with a reduction in all-cause mortality by approximately 4% to 7%, as demonstrated by a meta-analysis of cohort studies [94]. Notably, a study by James et al. [95] found a 41% lower mortality rate from kidney disease among women residing in areas with the highest levels of green vegetation.

The explanation for this seemingly remarkable phenomenon is multifactorial, involving all four pillars and their dynamic interactions. The presence of green spaces and natural environments encourages people to leave their homes, breathe higher-quality air—which is often difficult to achieve indoors—and spend time exposed to direct sunlight. This exposure is essential for activating some vital biological processes, including the evening production of melatonin (which supports restful sleep) and the synthesis of vitamin D, a nutrient essential not only for bone health but also as a potent modulator of immune function.

Moreover, green environments naturally promote spontaneous physical activity (physiological pillar). Individuals who engage in regular physical activity are more likely to adopt healthier eating habits (nutritional pillar) [96], cultivate stronger social relationships (psycho-relational pillar) [97], and exhibit a lower incidence of self-harming behaviours such as smoking, alcohol abuse, or drug use (psycho-social pillar) [98].

For these reasons, incorporating natural elements into the built environment—such as homes, schools, workplaces, and public buildings—represents a strategic approach to promoting physical and mental well-being. When thoughtfully implemented, biophilic design principles—including the use of natural materials, colours, and light—have been shown to replicate many of the health benefits associated with direct contact with nature [99]. Similarly, regular exposure to artistic expressions and aesthetically rich environments has been linked to improved emotional regulation, reduced stress, and enhanced overall health and well-being [100].

4.5. Implementation Challenges and Considerations

While the Healthy Habits (HH) approach offers a transdisciplinary framework applicable across scales—from schools to cities—its implementation is shaped by contextual variables such as urban density, cultural norms, socio-economic disparities, and infrastructural capacity. In dense metropolitan areas, opportunities for environmental redesign may be spatially constrained, requiring interventions within micro-environments such as rooftops, courtyards, and mobility corridors. Conversely, in smaller or low-density cities, where access to open space is greater, the primary challenge lies in sustaining social engagement and community participation over time.

Structural inequalities in access to green areas, healthy food, and safe mobility infrastructure persist, particularly in disadvantaged neighbourhoods. Furthermore, the effective integration of health, urban planning, and environmental policy is often hindered by institutional fragmentation and siloed governance. Cultural variability and limited financial resources may also affect the scalability and long-term adoption of HH-based interventions.

Recognising these constraints is essential to ensure both the equity and scientific robustness of the model. Integrating the HH framework into urban planning—through its four evolutionary pillars of physiology, psycho-relational well-being, nutrition, and environment—should therefore be seen not as an academic abstraction but as a strategic investment in preventive public health, capable of reducing the burden of chronic diseases and enhancing the overall quality of life in urban populations.

In this perspective, integrating the Healthy Habits approach into urban planning, grounded in the four evolutionary pillars of physiology, psycho-relational well-being, nutrition, and environment, should not be regarded as a merely academic exercise. Instead, it constitutes a forward-looking investment in public health prevention, with the potential to reduce the burden of chronic diseases and enhance the quality of life in urban populations.

5. Urban Systems and Social Interaction for Healthy Cities: The Outdoors Generating Healthy Social Networks

Over time, various paradigms in urban sociology have focused on the relationship between cities and the environment. In the social sciences, environmental issues have become increasingly important; however, questions related to the relationship between the environment and society are not yet fully incorporated into specific fields of research. The concept of networks is also key to studies of cities and territories and has formed the basis for efforts to model urban systems. This contribution aims to demonstrate that urban health is not an isolated policy objective, but a systemic property that emerges from the quality of interactions between people, environments, and institutions. In this perspective, the frameworks of Healthy Cities, social capital, and behavioural nudging converge toward a shared goal: the cultivation of preventive, self-regulating, and socially cohesive urban systems. The Healthy Habits (HH) approach provides a connective logic across these frameworks, translating them into operational levers for governance and design.

5.1. Complexity Theories and the Reticular Paradigm Between Social and Biophysical Ecosystems

Systems theory, especially in its sociological evolution proposed by Luhmann [101], together with theoretical and epistemological contributions from diverse fields (mathematics, physics, biology) and authors such as Edgar Morin [73], have shaped the so-called complexity sciences, which in the field of urban and territorial disciplines have inspired Complexity Theories of the City. The central idea of these new approaches is that urban systems are highly complex due to several factors: the multiplicity of actors involved in decision-making; the multidimensional nature of cities (system of economic exchanges, social behaviour, energy flows, etc.); their multi-level nature (from neighbourhood micro-spaces to metropolitan complexes and urban regions). According to this paradigm, cities are systems in constant imbalance due to the flows to which they are permanently subjected, and this approach seeks to identify the modes of self-organisation, the internal processes of the system, capable of generating order and cohesion from the chaos of behaviour. Recent systemic visions, in fact, distance themselves from the idea that it is possible to control the entire framework of variables that govern urban dynamics through external regulation (such as comprehensive planning), in favour of an adaptive-evolutionary vision. We must confidently identify the endogenous factors of self-organisation that urban planning can assist and catalyse through a synergistic interplay of top-down (proposed by institutions) and bottom–up (initiatives arising autonomously in sectors of society) processes, maintaining close contact with the physical and natural sciences [102].

Studies based more specifically on a network conception of urbanism focus on social networks, in which a complex set of actors or spatial units connect, establishing relationships of various kinds. These properties can be studied through specific mathematical formalisms. The reticular paradigm, in general, is an effective tool for understanding many aspects and processes of contemporary societies [103]. Even the concentration in large urban agglomerations must be interpreted as an expansion of networks that connect specific types of places in different regions: the main activities are networked according to their needs, and at the same time, many parts of cities, even “global” ones, live a local life in their own neighbourhoods. However, the use of a network-centred conception of the city leads us to address the broader issue of the relationship between networks themselves.

The contribution we wish to make in this regard is to introduce the importance of including ecological and natural networks in these reflections, both in the dynamics of the development of social relations themselves and in the mutual interaction between the quality of human life and the quality of the environment and biodiversity: social integration and participatory processes are essential for equitable access to green spaces and for maximising their health benefits. The integration of sociological theory—particularly the works of Giddens on structuration and Lefebvre on the production of space—provides interpretive depth to the HH framework. The idea of space as a social construct translates into the co-design of micro-infrastructures that sustain daily routines of movement, rest, and encounter. Similarly, reflexive modernity aligns with the HH emphasis on conscious habit formation, where urban design serves as a behavioural nudge toward self-regulation and collective care. Furthermore, we want to highlight the potential of this interaction between humans and natural outdoor spaces as a generator of social networks for health.

5.2. The City-Environment Co-Evolution to Increase Resilience and Quality of Life

In terms of urban design, the debate on aspects of relationship/interaction has always had two strands: on the one hand, there are virtual relationships, which are increasingly important, especially with the pervasive spread of social media, and on the other, there are physical and sensory relationships. Concerning the latter, our reflection adds an aspect that could prove decisive for a sustainable and desirable future of living: meaningful physical relationships in urban areas are those located not only in traditional places (streets and squares) or connections (airports, stations), but also in contiguous natural spaces that are particularly relevant for the protection of biodiversity. Regarding the integration of design and networks, several studies describe how community gardens and green spaces serve as ecological and social nodes, supporting biodiversity and social cohesion.

Urbanisation processes are interdependent and co-evolve with the environment: social and biophysical systems are both dynamic systems, whose modes of transformation depend not only on principles internal to each of them but also on mutual relationships [104], as already highlighted in the One Health approach. The concepts of ‘socio-ecological systems’ [105] and ‘resilience’ [106,107] also point in this direction. Suppose we look at the city as a socio-ecological system. In that case, its spatial dimension cannot be limited to the compact area of the settlement. Still, it must also include less dense spaces, connected by both social and environmental relationships. For this reason, it is necessary to consider certain biophysical indicators (e.g., related to hydrography, geology, or the configuration of ecosystems). The city-environment relationship is multiscale and requires increasing attention not only to the physical form of settlements, but also to how space is used, social practices, and the lifestyles of inhabitants [108]. In many social studies, great importance is attached to the analysis of urban practices, by which we mean all those complexes of human activities centred on the physical dimension of individuals, organised around shared fields of practical meanings [109] (examples of shared urban practices include sports activities in parks, gardening, walking the dog, and using bicycles as a means of transport). For sociologists dealing with theories of shared urban practices within the sphere of everyday life, a point of reference is De Certeau [110], who highlights how individuals can develop creative tactics for using products, which translated into terms of urban space means that ‘individuals are not simply consumers of an imposed ‘rational’ architectural or urban design; they are instead enunciators of their own spatial discourse’ ([108], p. 290).

However, it seems interesting to also emphasise the thinking of Georg Simmel, ‘the most contemporary of the classics’ ([111], p. 11), one of the leading figures of the Chicago School. Simmel’s central insight is the universal interaction and interpenetration of all phenomena, the effect of reciprocity or mutual action. Reality is a network of mutually influential relationships between a plurality of elements, and the object of sociology is the forms of mutually influential relationships between people. For Simmel [112], the metropolis is the quintessence of modernity, characterised by a permanent crisis, an age in which change becomes the norm, and where the spirit of the times is embodied, as well as the forms of contemporary life and experience are revealed. In his analysis of experience, the features of the objective world and everyday life correspond to a configuration of the individual personality that is both its product and its prerequisite. And in this cornerstone of Simmelian relativism/relationalism, according to which nothing in life exists without being related to the rest, it is possible to introduce new considerations on the potential and variations of the relationship between man and nature, and on the consequent possibility of experiencing and practising ‘healthy networks’. This is the theme on which this article focuses.

5.3. Nudges for Triggering New Urban Practices and Healthy Social Networks

It is necessary to rethink landscapes, green infrastructure frameworks, and connections with Natura 2000 networks, and to listen to communities to identify values and connections, as well as the intensity and types of relationships, to understand where interventions can be effective. It is necessary to define the conditions for coexistence, making the coexistence of anthropogenic and protected natural systems viable and fertile, and making it practicable by building networks and platforms that enable and empower social dynamics and healthy urban practices. Nudges, or gentle pushes, can be a form of urban and communicative action that promotes all of this. A nudge is a communicative act, since it exploits the exact mechanisms as rhetoric, i.e., ‘shifting an opinion and pushing towards a behaviour’ considering the cognitive, emotional and cultural characteristics of the interlocutor [113]. Moreover, nudging implies ‘medium-sized gains for microscopic investments’ ([114], p. 397): the former, translated into awareness of risks and/or environmental and health issues of general interest, translate into an impact on the level of collaboration between governments and communities, and on levels of territorial and social sustainability [115] (e.g., the Mexican Women Empowerment/Forest Protection, a poster dissemination via WhatsApp to encourage women’s participation in the management of forest protection funds and projects; or the case of Galeria EL in Elbląg, Poland, developed by director Adriana Kotynska, who implemented a natural and organic solution to promote social distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic, namely the creation of a checkerboard effect generated by mowing the lawn). It is in the way we experience cities, islands, and territories, and in the relationship between social and ecological systems, that the challenge of a possible, desirable, and balanced future is played out. Nudges appear to be robust and effective tools in triggering and consolidating sustainable awareness and practices (e.g., community gardens with signage that encourages interaction, apps that reward the use of green spaces, and bench design that encourages conversations). Comparative experiences also reinforce the transferability of Healthy Habits-oriented nudges and social design strategies. In Copenhagen, behavioural insights have informed the redesign of school canteens and active-mobility corridors to promote healthier routines. Barcelona’s Superblocks programme integrates environmental nudges by re-prioritising pedestrian space, reducing noise and air pollution while stimulating social exchange. Similarly, in Portland (Oregon), zoning reforms have coupled green infrastructure with social programming to strengthen neighbourhood identity and participation.

The integration of environmental, behavioural, and social cues can generate virtuous feedback across the health and ecological domains. By positioning nudges within a broader ecosystem of social and spatial design, connections can be highlighted between micro-level behavioural interventions and macro-level urban governance. The architects of choices, who develop the nudges, can legitimately influence individuals’ behaviour to make their lives safer, longer, healthier and better [82], and therefore institutions, both public and private, should consciously strive to improve the living conditions of citizens through their choices: by encouraging, or “pushing”, healthy behaviours; by stimulating urban practices connected to peri-urban ecological networks, and by designing natural and green spaces within cities. The Healthy Habits approach thus acts as a translator between disciplines, showing that material conditions and collective rituals and networks shape everyday behavioural patterns. A healthy city is not the sum of discrete actions, but the outcome of shared habits supported by spatial, institutional, and cultural infrastructures.

6. Discussion

The broader academic literature suggests that explicit connections between biodiversity, social networks, and urban design began gaining significant attention in the mid-2000s, with foundational work in urban ecology and environmental psychology [116]. The concept of “biophilic cities” [45], blue-green infrastructure, and ecosystem services in urban planning gained prominence around 2008–2012 [117]. This corresponds to the transition from an integrated to a systematic and holistic vision of human well-being and ecosystem health, identified in the evolution of European environmental policies. The integration of biodiversity considerations into urban health research has accelerated, particularly since 2015, coinciding with the UN Sustainable Development Goals [50] and increased recognition of nature-based solutions for urban challenges [118,119,120,121]. This rising interest in urban socio-ecological networks and health is further confirmed by data from the Elicit scoping review, which shows an increasing trend in research publications over time (years 2010–2014: 79 publications; 2015–2019: 161; 2020–2024: 209). The most recent period (2020–2024) has the highest number of studies, reflecting a growing academic interest in urban design, socio-ecological networks, and health interrelations.

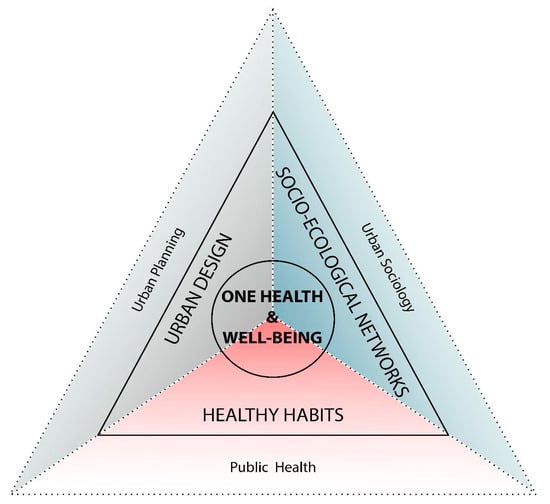

The scoping review demonstrated the increasing integration of various methods in urban design, including advanced measurement approaches [15,122] and sophisticated assessments of green space quality [20,23]. An increased attention to climate-related factors and environmental justice [12,21,123,124] is reflected in integrated planning for a healthy city. The comprehensive perspective on urban socio-ecological health suggests that synergistic strategies among different approaches can generate significant benefits for the quality of the environment and the quality of life of inhabitants. The evidence examined confirms that physical proximity to natural environments promotes physical activity, reduces the risk of chronic diseases, and improves psychological well-being, while simultaneously creating habitats that support biodiversity. Frameworks such as One Health [13], the Eight Dimensions framework [15], and Salutogenic urban design [24] illustrate that when socio-ecological networks are integrated with well-planned urban structures, healthy habits are reinforced. The One Health paradigm is identified as the principal integrative framework that introduces a holistic approach and reflects the interrelation of human and environmental health with urban design and socio-ecological networks (Figure 4). This holistic vision is outlined in the comprehensive European Green Deal strategy [51] and the United Nations’ 2030 Agenda [50]. These instruments promote an urban planning model in which human quality of life is inextricably linked to the health of ecosystems. Despite the progress made, a certain discontinuity persists between political vision and urban planning practice, indicating that the full implementation of the holistic vision still requires further efforts to integrate environmental policies with spatial planning. Therefore, the health-oriented urban design must go beyond traditional planning paradigms and tools, adopting flexible, relational, and transdisciplinary approaches to address the challenges posed by contemporary times.

Figure 4.

Integration of urban design, Healthy Habits, and socio-ecological networks in the One Health framework for resilient, sustainable, and inclusive cities.

The scoping review of health outcomes for urban planning and design extends beyond physical activity to include broader well-being measures [12,19,24], social involvement, and community engagement [11,20,117], introducing more nuanced health measures (self-rated health and dietary outcomes, sleep patterns, screen time, loneliness) and health-related quality of life measures [116,125]. The thematic review confirms the Healthy Habits approach as a cross-cutting determinant of public health within the One Health paradigm. It introduces the Healthy Habits approach as a conceptual and operational model for embedding One Health principles into urban design. The Healthy Habits approach introduces an original contribution to urban health theory by integrating behavioural science, evolutionary physiology, and environmental design into a single operational paradigm. It reframes health not as a static condition but as a dynamic equilibrium maintained through continuous interaction among the four evolutionary pillars—physiology, psycho-relational well-being, nutrition, and environment. While the potential of the HH approach lies in its integrative capacity, its application is not exempt from contradictions and trade-offs.

In the thematic review, the application of behavioural insights, particularly nudges, emerges as a cost-effective way to influence lifestyle choices and encourage sustainable practices without resorting to coercion. Urban and communication nudges [82,114] are proposed as the most effective tools for activating and strengthening socio-ecological health networks. Cities become the spaces of flows (economic, cultural, political, and informational) and society becomes a networked system, composed of nodes and relationships. In this sense, interrelationships play a fundamental role: social networks and the urban space of networks influence each other. The inclusion of ecological networks in this co-generation system, along with the use of nudges (urban, green, and digital) to foster healthy behaviours and achieve overall well-being, can contribute to the creation of healthy social networks. Nonetheless, translating these insights into urban planning requires overcoming institutional silos and strengthening collaboration among public health, environmental management, urban design, and public policy sectors. The findings highlight self-organisation, bottom–up initiatives, and the role of open spaces as relational spaces that can become decisive in fostering social cohesion and resilience. The importance of community participation in urban design development fosters healthy social relationships and networks, serving communities and promoting human health, especially when it is intertwined with natural and ecological networks.

In the scoping review, the need for inclusive and accessible urban design is emphasised by setting a greater attention on vulnerable populations, including children and older adults [12,24,126] and minority populations [11,116]. In general, the research evolved from basic walkability and access measures in the early period to sophisticated, multi-dimensional assessments of urban design impacts on comprehensive health and well-being outcomes, with increasing attention to justice, equity, and climate considerations [21,123,124] in the most recent period. The transformation of urban environments toward healthier and greener standards opens possibilities for inadvertently triggering processes of eco-gentrification, where an improved quality of life leads to rising property values and social displacement. Similarly, resource constraints and administrative inertia can slow the institutional adoption of preventive health paradigms. Recognising these tensions is crucial to avoid an idealised vision of the healthy city and to promote adaptive, context-sensitive policies that balance ambition with equity.