2.3.2. Assigning Weights to Attributes

This is a subjective task and a crucial input for finding the most balanced solution(s) in MADM problems. Imprecise and/or unreliable information from the decision-maker, i.e., weight values without the required accuracy or put forward without the required confidence must be avoided. Thus, in the case study presented here, the attribute weights are established based on expert knowledge and three structurally different analytical methods: CRITIC, Best–Worst, and Entropy methods. Applications of these methods were reported by various authors; nevertheless, it is important to be aware that any subjective or objective method for determining weights to attributes has its advantages and flaws. The reader is referred to [

62] for details and an overview of various methods.

The Criteria Importance Through Inter-criteria Correlation (CRITIC) method does not require subjective information from experts or decision-makers. It calculates the weights for each attribute based on contrast intensity (variability or standard deviation) and conflict (correlation) among attributes. In practice, the greater the contrast intensity of an attribute and the lower its correlation with other attributes, the higher the priority or weight assigned to it. This indicates that the attribute has strong discriminative power and conveys information that is independent from that of the other attributes.

The CRITIC method is applied to a decision matrix as follows:

Step 1—Decision Matrix Normalization: Since the attribute’s values may have different units and magnitudes, it is necessary to normalize the decision matrix (3). For normalization purposes, each

is transformed into an

value depending on attribute type. For a larger-the-better-type attribute,

and for a smaller-the-better-type attribute,

where

is the minimum value of

across all alternatives, and

is the maximum value of

across all alternatives. The normalized decision matrix (N) is of size

m ×

n, and it represents the normalized performance of the

ith alternative on the

jth attribute. The normalized performances (

are dimensionless and range between zero and one (

.

Step 2—Standard deviation calculation: The standard deviation (

) for

across all alternatives is

where

is the mean value of

across all alternatives. A higher

means the attribute better differentiates between alternatives.

Step 3—Correlation matrix computation: Calculate the Pearson correlation coefficient (

) between each pair of attributes,

j and

, with

. This measures how similar the attributes are.

where

is the covariance between attribute

j and

.

Step 4—Calculate the information content: The information content of

is

The higher the information content value is, the more important the attribute will be.

Step 5—Attribute weight calculation: The weight of

is

and the sum of

equals 1.

The Best–Worst Method (BWM) determines the relative importance (weights) of a set of attributes through a structured pairwise comparison process between the most and the least important attribute, according to decision-maker preferences. Its implementation procedure is as follows:

Step 1—Determine the Best and Worst Attributes and their Preference Values

The most important (desirable and influential) attribute and the least relevant (uninfluential and worst) attribute from the set of attributes are selected by the decision-maker (expert). Then, they must assign a preference value to the best attribute compared to each of the other attributes using a predefined scale (e.g., a 1 to 9 scale, where 1 indicates equal importance, and 9 indicates the extreme importance of the best attribute compared to the other attributes). The resulting vector of pairwise comparisons is , where represents the preference of the best attribute () over all the other attributes.

Step 2—Determine the Preference of All Other Attributes over the Worst Attribute

A preference value is assigned to each one of the attributes compared to the worst attribute by the decision-maker (expert), using the same predefined scale, and represents the resulting vector of pairwise comparisons as (, where represents the preference value of each one of the attributes over the worst attribute ().

Step 3—Determine the Optimal Weights (, , …, ) for Attributes

To achieve this goal, the maximum absolute difference between

and

will be minimized for all attributes. For this purpose, the following optimization problem must be solved:

where ξ is the consistency ratio,

is the weight of the

jth attribute,

is the weight of the best attribute,

is the weight of the worst attribute,

is the preference of the best attribute over the other attributes, and

is the preference of the

jth attribute over the worst attribute [

47].

Step 4—Check the Consistency Ratio

A consistency ratio indicates how (in)consistent a decision-maker (expert) is. The consistency index (ξ) indicates the consistency level of the pairwise comparisons (set of judgments contained in vectors

and

). The preferences are consistent if

for all

j. To check for the consistency, the global input-based consistency ratio for all attributes (

is formulated as follows [

63]:

where

represents the local consistency level associated with attribute

.

If

is not greater than a specific threshold that depends on the size of the problem (

m) and on the magnitude of

, then the pairwise comparisons provided by the decision-maker are reliable enough. A

value closer to zero indicates higher consistency, otherwise, his/her preference information needs to be revised [

64,

65].

The Entropy method (EM) assesses the variability for each attribute and assigns weights to attributes considering the value of the diversity factor (. Thus, the higher the entropy value is, the higher the weight assigned to the jth attribute will be. The implementation procedure is as follows:

Step 1—Decision Matrix Normalization: Transform each

value into an

value. For a larger-the-better-type attribute,

and for a smaller-the-better-type attribute,

Step 2—Entropy calculation: The entropy of

is

where

is a normalization factor and

.

Step 3—Determine the optimal weights of the attributes: The weights are calculated as

with

.

2.3.3. Select the Best Compromise Solution

There are many MADM methods, and they do not necessarily produce the same ranking for the problem solutions. Therefore, using more than one method is common practice. Extensive studies on those methods and their variants (changes in the performance measure normalization, as an example) have been undertaken over the past decades and their usefulness has been proved. Nevertheless, despite the large number of proposals reported in the literature, reaching a consensus on the most suitable method or approach for a given scenario is difficult [

44,

45,

52].

Ten MADM methods, namely the popular TOPSIS (four different versions), PROMETHEE II, Utility, MOORA, Desirability, WSM, and WASPAS, were selected to analyze data obtained by Monte Carlo simulation for 10 hydrogels and 3 attributes. In this study, 10,000 values were generated for each attribute, so 10,000 decision matrices were built. Method choice was dictated by their popularity, adequacy, and proven effectiveness in many different domains. Notice that 4 sets of weights were tested in the case study presented here, which means that each method analyzed 4 sets of 10,000 decision matrices.

The Preference Ranking Organization Method for Enrichment Evaluation (PROMETHEE) has been modified (“adjusted” or improved) by some authors [

29]. In this paper, the PROMETHEE II was employed using a V-shape preference function with indifference and preference thresholds. Its implementation procedure is as follows:

Step 1—Calculate the Aggregate Preference Index (after building the decision matrix)

For every pair of alternatives

with

, and for each attribute, compute the aggregated preference index of

over

,

where

represents the preference of the

ith alternative with regard to the

kth alternative for attribute

j, with

. Notice that

used here is a V-shaped linear preference function, where

q represents the indifference threshold and

p represents the preference threshold for a larger-the-better-type attribute. For the smaller-the-better-type attribute,

p represents the indifference threshold and

q represents the preference threshold.

Step 2—Compute the leaving and entering outranking flows

For each alternative , compute the following:

the Leaving Flow (or positive outranking flow)

the Entering Flow (or negative outranking flow)

Step 3—Calculate the net outranking flow

For each alternative, the net outranking flow is

The higher the net flow is, the better the alternative will be.

The Weighted Aggregated Sum Product Assessment (WASPAS) method combines two classic methods: the Weighted Sum Model (WSM) and Weighted Product Model (WPM). Its implementation procedure is as follows:

Step 1—Normalize the decision matrix

For larger-the-better-type attributes,

For lower-the-better-type attributes,

Step 2—Calculate the weighted additive relative importance of the

ith alternative:

Step 3—Calculate the weighted multiplicative relative importance of the

ith alternative:

Step 4—Calculate the combined index (

)

where

. The value of α was set to 0.5, as is usually performed. Notice that WASPAS becomes a weighted product method when

and a weighted sum method when

.

Step 5—Sort the alternatives: The alternatives are sorted based on the index. The higher this value is, the better it will be.

The weighted sum method is very popular among researchers and practitioners. Thus, the classic version of this method is also employed here. The objective function used, the

index, is as follows:

where

for larger-the-better-type attributes, and

for smaller-the-better-type attributes. Note that

in

is different from that used in WASPAS, and the higher the

value is, the better it will be.

The Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS) method is one of the most popular methods among researchers and practitioners for multi-attribute optimization, and it has been applied in various scientific fields. It works by converting multiple attributes into a single attribute and then determining the best alternative based on its closeness to the ideal solution. Its implementation procedure is as follows:

Step 1—Normalize the Decision Matrix

Each value in the decision matrix is normalized as

Step 2—Determine the Weighted Normalized Matrix

Each value in the normalized matrix is multiplied by the respective weight as shown in (29).

Step 3—Identify the Ideal and Negative-Ideal Solutions

The best values for each attribute (ideal solution,

Is+) and the worst values for each attribute (negative-ideal solution,

Is−) are determined as

and

where

represents the larger-the-better-type attributes and

represents the smaller-the-better-type attributes.

Step 4—Calculate the Separation Measures

Compute the distance of each alternative from both the ideal and negative-ideal solutions using Euclidean distance as follows:

and

where

is the distance from the ideal solution and

is the distance from the negative-ideal solution.

Step 5—Determine the Relative Closeness to the Ideal Solution

The alternative ranking is determined using the closeness coefficient,

where

represents the relative closeness of the

ith alternative to the ideal alternative (that one whose attribute values are as close as possible to the ideal values).

Step 6—Rank the Alternatives

The best alternative is that with a higher value.

Three additional variants of the TOPSIS method were also tested in the case study presented in this paper. In the first variant of the TOPSIS method, called

, the decision matrix is normalized as follows:

and all the remaining steps of the TOPSIS implementation procedure are kept unchanged. The second variant of the TOPSIS method, called

, presents an infinite norm instead of a Euclidean distance to calculate the Separation Measures (see step 4 of the TOPSIS implementation procedure). Thus,

and

The third variant of the TOPSIS method () is a combination of and .

The so-called Utility method is another popular option to support the decision-making in multi-attribute optimization problems. In the Utility method, each

(performance measures of the

ith alternative on the

jth attribute) is transformed into a preference score

using a logarithmic scale:

where

is the minimum acceptable value for the

jth attribute and

is a scaling factor.

where

is the best possible performance measure for the

jth attribute and

is calculated such that the best possible performance value for the

jth attribute yields a maximum preference score of 9 (

. Thus, if weights are assigned to attributes, the overall utility for each alternative, with

, is calculated as

and the higher the weighted overall utility (

) value is, the better the alternative will be.

The global desirability function proposed by [

66], called the Desirability method, have been widely used for solving multi-objective problems developed under the Response Surface Methodology framework in various science fields. In this method, individual desirability functions normalize the performance measures and are aggregated into a geometric mean. The individual desirabilities and the global desirability function take values between 0 and 1, where 1 is the most favourable value.

For smaller-the-better-type attributes, whose performance measure is desired to be smaller than an upper bound

, the individual desirability is defined as

where

s is a user-specified parameter

.

For larger-the-better-type attributes, whose performance measure is desired to be larger than a lower bound

, the individual desirability function is defined as

The values assigned to

s allow changing the shape of

. A large value for

s implies that the

value is very small unless the response comes very close to its desired value. This means that the higher the

s values are, the greater the importance of the attribute values being closer to the respective target will be. A small value for

s means that the

value will be large even when the attribute is distant from its desired value. The global desirability function is defined as the geometric mean of the individual desirabilities,

where

are user-specified parameters that allow assigning priorities (weights) to the individual desirability functions. The objective is to maximize

. When

, all the attribute values are the best ones

. When

, at least the value of one attribute is equal to its worst value

. It is for this reason that the geometric mean prevails over the arithmetic mean, such as is shown in [

67,

68]. For a review on other desirability-based methods, the reader is referred to [

69].

Multi-objective optimization on the basis of the ratio analyses (MOORA) method has also been successfully applied to solve various types of multi-attribute problems in (non)manufacturing environments. Examples include selecting a road design, a facility location, an industrial robot, a flexible manufacturing system, a prototyping process, and welding process parameters [

70,

71].

In the MOORA method the first implementation step is to normalize the performance measures. According to [

72], it is recommended to use the square root of the sum of squares of performance measures, which is defined as

The

are then aggregated depending on the attribute type. In the case of larger-the-better-type attributes, the

are added; for smaller-the-better-type attributes, the

are subtracted. The aggregate function of the

is defined as

where

g is the number of larger-the-better-type attributes and n is the total number of attributes. The number of attributes to be minimized is

. If some attribute is more important than the others, which is usual in practice, preference parameters or weights must be assigned to them. In this case, the aggregate function is defined as

and the higher the

Mi value is, the better the alternative will be.

2.3.4. Ranking Similarity, Ranking Acceptability, and Pairwise Winning

Ten MADM methods were employed to analyze data generated by Monte Carlo simulation. Ten thousand decision matrices were built and 10,000 rankings were generated by each of the 10 methods employed in the case study presented here. Therefore, evaluating ranking similarity (correlation) is necessary to determine how similar obtained rankings are and obtain valuable insights into method efficacy and applicability in real-world contexts. Evaluating ranking similarity is a relevant practice and a helpful input for those who need to select a solution for multi-attribute problems. When rankings align, it makes the decision about the most favourable solution easier to explain and defend to stakeholders and obtain valuable insights into method efficacy and applicability in real-world contexts. However, some methods may favour certain alternatives due to their computational structure. Ranking similarity helps reveal such biases, but other tools must be used to aid in identifying the most promising solution(s) for multi-attribute decision-making problems. For this purpose, ranking acceptability and pairwise winning indexes are helpful and used to identify the most promising hydrogel(s).

Spearman’s rank and Kendall’s rank are two popular ranking similarity indexes widely applied in various domains beyond MADM when dealing with ranked data [

73,

74,

75,

76,

77]. They provide a comparative assessment of multi-attribute decision-making methods by indicating the relative closeness of a method with other methods in terms of ranking outcome similarity. However, criticisms are reported in the literature [

73,

77,

78]. A major criticism on Spearman’s rank and Kendal’s rank is related with the impact of exchanges at the top-ranking positions into the index values comparatively to exchanges at the bottom-ranking positions. The rankings are determined to help in choosing the best or more promising alternatives (solutions), which are in the top positions of the ranking. Thus, exchanges at the top positions should be more impactful on the similarity than at the bottom of the ranking. As an example, a shift from first to second position in the ranking is more undesirable and impactful on the similarity than a swap between third and fourth positions. According to [

77], the

ranking similarity index overtakes this drawback so it will be a useful tool for testing, comparing, and benchmarking multi-attribute decision-making methods in terms of ranking outcome similarity, thus contributing to better-informed and reliable decision-making on the solution selection for multi-attribute problems.

is an asymmetric measure whose value for ranking comparison is determined by the positions in a ranking assumed as the reference ranking in the calculations [

78]. The reference ranking is defined here as

where

represents the position in the ranking of the

ith alternative (hydrogel). The

index (48) was developed to be sensitive to the position where the exchanges occur in the ranking, easy to interpret, and its values are limited to a specific interval (takes values from zero to one) [

77].

where

represents the place of the

ith alternative in the reference ranking,

represents the place of the

ith alternative in another selected ranking, and

represents the length of the ranking.

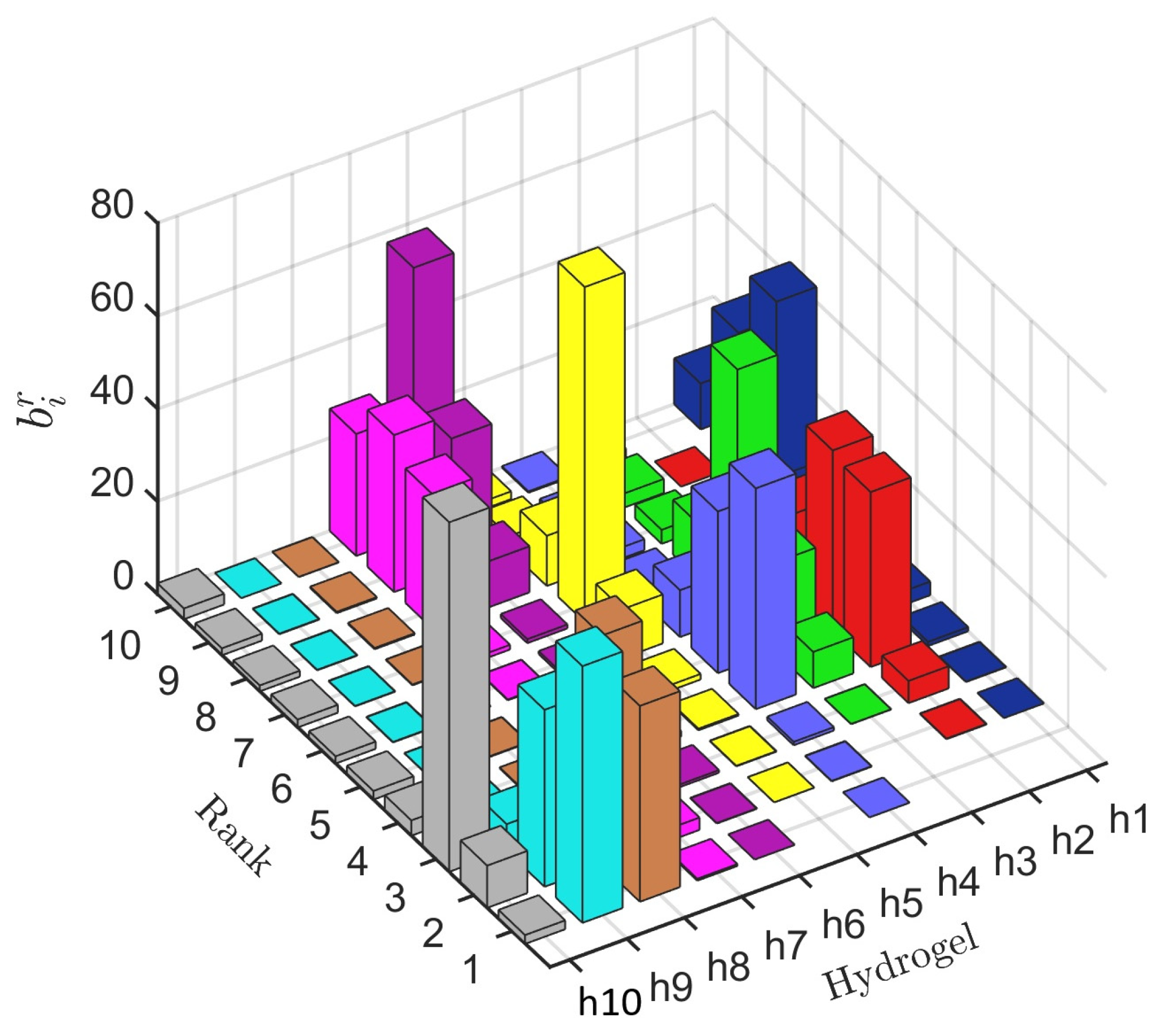

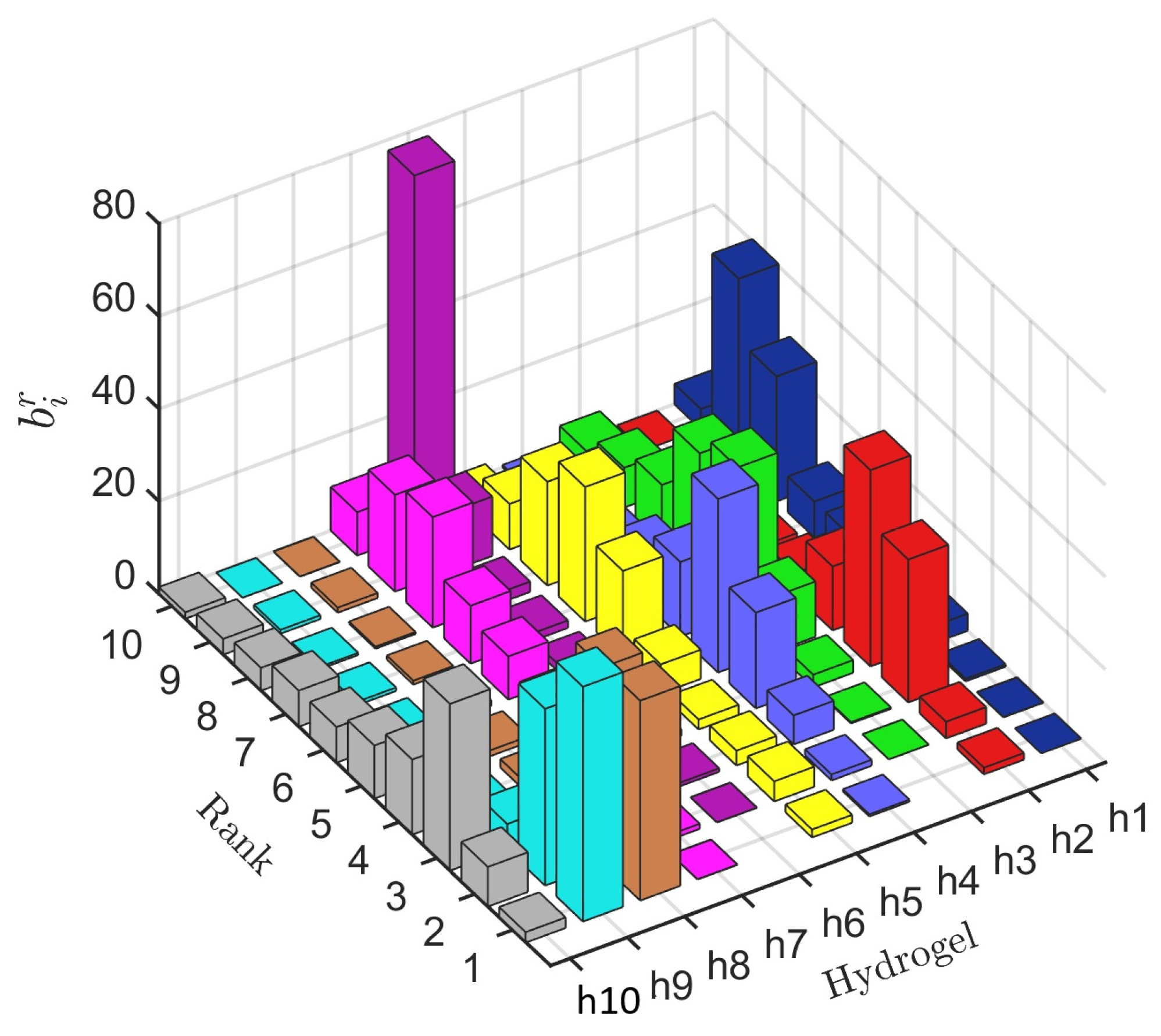

A rank acceptability index, the

index, which yields the probability that the

ith alternative will receive the

rth position in the ranking, was obtained based on the rankings yielded by the ten methods (100,000 rankings). High acceptability index values for the best ranks, the first, second, and third, as an example, suggest that alternatives in those rankings are the most promising candidates (are promising solutions) for solving the MADM problem. The first rank acceptability index (

determines the probability that the

ith alternative is the most preferred, and its value must be equal to or as close as possible to 100%, whereas for inefficient alternatives, the first rank acceptability index is close to or equal to zero. This index is estimated as follows [

67]:

where

K is the number of alternative rankings (Monte Carlo iterations) and

is the number of times the

ith alternative obtained the

rth position in the ranking. Notice that, for the

ith hydrogel,

. The

values are characterized by a certain precision and an assumed confidence interval, depending on the number of iterations [

60]. The expected precision of

values can be calculated as

where

denotes the standard score for a confidence level (1 −

) [

60,

79]. In Monte Carlo simulations, the required number of iterations is inversely proportional to the square of the desired accuracy but does not significantly depend on the dimensionality of the problem. The number of iterations is typically 10

4–10

6, which gives a precision of 0.01–0.001 for 95% confidence, respectively [

51,

60,

79,

80].

The

index is useful for screening the alternatives, i.e., eliminating the least promising alternatives. A pairwise winning index, the

index, is also calculated. The

yields the probability that the

ith alternative will achieve a higher ranking than the

kth alternative, and unlike the

, the pairwise winning index between one pair of alternatives is independent of the other alternatives. This means that

can be used to form a final ranking among the alternatives, eliminating alternatives that are dominated by other alternatives. Alternatives are ranked so that each alternative precedes all the remaining alternatives for which

or another bigger threshold value [

51]. The pairwise winning index is estimated as

where

represents the number of times that the

ith alternative precedes the

kth alternative in

K rankings.