Abstract

Electrical and electronic installations (EEIs) are essential to modern building functionality, yet they remain insufficiently addressed in circular economy (CE) strategies and sustainability frameworks. This study examines how CE principles are understood and applied to EEI in the Flemish construction sector, utilising a national survey of 32 professionals and, among them, five expert interviews. Results confirm that energy-efficient technologies, such as LED lighting and the integration of renewable energy, are widely adopted. In contrast, circular practices, including reuse, modularity, and design for disassembly, remain relatively rare. Respondents acknowledged the importance of lifecycle thinking but reported limited access to practical tools, clear guidelines, and market or regulatory incentives to support its implementation. Circular business models, such as leasing and take-back schemes, are recognised in theory but not widely adopted in practice. At the same time, stakeholder engagement often occurs too late to influence circular outcomes. Overall, the findings suggest that strengthening interdisciplinary cooperation, improving knowledge exchange, and defining clearer project requirements could help translate circular principles into everyday professional practice. This study provides an initial evidence base for improving professional awareness and integrating circular principles into EEI design and procurement, contributing to more circular and sustainable EEI within the construction sector.

1. Introduction

The construction industry is undergoing a transformative shift toward sustainability and circularity, driven by escalating concerns over resource depletion, greenhouse gas emissions, and increasing waste generation [1]. In fact, the construction industry accounts for nearly half of all extracted materials and over a third of the European Union (EU) waste, representing a critical intervention point in the European Green Deal [2]. This transition is supported by key EU policy frameworks such as Fit for 55 [3] and the Circular Economy Action Plan (2020) [4], which identify construction as a priority value chain for achieving circular economy objectives [5].

While much attention is given to construction materials and structures, the construction sector’s environmental impact also extends to the operation of technical installations. In EU households, heating, ventilation, and air-conditioning (HVAC) systems dominate energy demand. In 2023, space heating alone represented 62.5% of final household energy use, with water heating contributing 15.1% and space cooling 0.6%, together accounting for nearly four-fifths of total household energy consumption [6]. At the same time, electricity has become the fastest-growing form of final energy use in buildings, driven by the uptake of electric heat pumps, the growing demand for air conditioning, and the broader electrification of energy systems in response to stricter energy efficiency regulations [7]. This electrification trend brings electrical and electronic installations (EEIs) to the forefront of sustainable building performance.

This rapid shift underscores the increasing importance of EEIs as essential components of building functionality and energy performance. Despite their critical role, EEIs often receive less attention than structural and material components in sustainability discussions. The literature studies indicate growing awareness of their relevance, yet lifecycle considerations such as reuse, disassembly, and material recovery remain largely neglected. For example, life cycle assessment (LCA) studies of luminaires show that operational energy use dominates environmental impacts (≈96%). At the same time, manufacturing and end-of-life phases, though smaller, still contribute substantially to embodied emissions and material use [8]. Furthermore, EEIs are highly resource-intensive due to their reliance on critical raw materials such as copper, aluminium, and rare-earth elements [9].

Despite their environmental relevance, the role of EEIs in sustainable construction remains underestimated. Most policies, standards, and assessment tools prioritise construction materials and operational energy while overlooking the broader lifecycle impacts of building services and electrical systems. This has resulted in a lack of dedicated instruments to support the sustainable and circular design of EEI.

Nevertheless, at the European level, several initiatives and regulatory frameworks have been introduced to bridge this gap. The RoHS (Restriction of Hazardous Substances) [10] and WEEE (Waste from Electrical and Electronic Equipment) [11] directives aim to reduce e-waste, one of the fastest-growing waste streams, by promoting safer materials and responsible end-of-life management. More recently, initiatives such as EECONE (European ECOsystem for Circular Electronics) [12] have promoted sustainable electronics through the “6R” approach: Reduce, Reliability, Repair, Reuse, Refurbish, Recycle [12].

The development of lifecycle standards for EEIs remains, however, at an early stage. While the European standard EN 15804 [13] has provided a foundation for harmonised environmental product declarations (EPDs), it does not explicitly address EEI. New complementary Product Category Rules (c-PCRs), issued under PCR 2019:14 [14], have expanded the scope to include product-specific rules for building services and energy components such as photovoltaic modules, electrical cables, ventilation systems, inverters, and energy storage [15]. Nevertheless, building services remain particularly underrepresented in most databases and tools [16], and detailed lifecycle data for many EEI components are still lacking.

A promising step forward is the Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation (ESPR) [17], which entered into force in July 2024. By establishing a harmonised framework for ecodesign requirements across nearly all product categories, ESPR introduces Digital Product Passports (DPPs) that can improve lifecycle data availability and traceability for EEIs. By focusing on durability, reparability, and recyclability, the ESPR is expected to influence the design and documentation of EEI in buildings, particularly in areas such as material selection, disassembly planning, and end-of-life traceability.

In parallel, sustainability and circular economy (CE) principles have driven the creation of assessment tools to help professionals assess and improve the lifecycle performance of buildings. In Belgium, for example, TOTEM (Tool to Optimise the Total Environmental Impact of Materials) [18]—an LCA-based calculation tool for buildings—and GRO (Gebouwen Referentie Ontwerp) [19], a voluntary sustainability framework for goal-setting and monitoring, support construction professionals in integrating sustainability and circularity into design and monitoring processes. Similarly, Green Building Rating Systems (GBRSs) [20] tend to emphasise construction materials and operational energy efficiency, even though a review of major systems such as BREEAM, LEED, DGNB, and HQE revealed that EEIs are only partially considered, mainly regarding lighting, home automation, control systems, and electric vehicle integration. However, most of these tools primarily focus on construction materials and operational energy efficiency, and overlook technical installations, including EEIs.

To conclude, while the European construction sector is advancing toward greater sustainability and circularity, the role of electrical and electronic installations remains insufficiently explored. First, existing policies and standards provide a strong foundation, but their translation into practical guidance for EEI design throughout the entire life cycle, encompassing both sustainability and circularity aspects, remains limited. Second, existing platforms and tools for assessing building sustainability and circularity rarely address EEIs, further hindering their integration into sustainable and circular construction practices.

Building on these identified gaps, the present study investigates how construction professionals apply sustainability and circularity principles in practice, and how these are integrated into the design and procurement of EEIs. The overall goal of this study is to examine knowledge gaps in EEI design and procurement, as well as the potential of practice-based approaches, and barriers encountered by the professionals. Adopting a bottom-up research approach, the study seeks to derive insights from practitioners’ experiences to inform the development of guidance documents and tools that support sustainable and circular EEIs. Ultimately, the study aims to bridge the gap between policies and standards on the one hand, and practical tools for EEI design on the other.

To guide this investigation, the following research questions were posed:

- RQ1: How are sustainability and circular economy principles applied by professionals across the lifecycle of EEIs?

- RQ2: How do digital tools, technical standards, and certification frameworks enable or constrain the implementation of circularity in EEI practices?

- RQ3: How do professional roles, collaboration dynamics, and emerging models influence decision-making on circular and futureproof EEIs?

This study was conducted within the framework of the E-construct project, funded by VLAIO (Flanders Innovation & Entrepreneurship), which explores how sustainability and circularity principles can be applied to the design of technical systems—and particularly EEIs—in buildings.

2. Literature Review

Sustainability assessment in construction has advanced considerably over the past two decades, supported by the development of environmental rating systems and lifecycle-based evaluation methods [21,22]. However, most regulations and studies concentrate on structural materials, energy performance, and embodied carbon, while technical systems, particularly lighting, automation, and electrical infrastructure—remain treated as secondary components [16,23]. As a result, EEIs remain peripheral in both policy and academic debates, despite their central role in supporting digitalisation, enabling the energy transition, and determining the long-term adaptability of buildings [24]. The design stage—when decisions about materials, sourcing, and future disassembly are made—offers a key opportunity to embed sustainability principles in these systems, yet it remains underexamined. In parallel, sustainability discussions have increasingly converged with circular-economy thinking, which translates broad environmental objectives into actionable strategies for resource efficiency, design for longevity, and waste prevention [25], which are highly relevant to the design, installation, and procurement of EEIs.

Extending these principles to the EEI highlights both the urgency and the complexity of achieving circularity: rapid innovation cycles and early obsolescence restrict repair and reuse, resulting in significant material losses at end-of-life [26,27]. Nevertheless, most circular initiatives remain focused on product-level solutions, such as appliances or consumer devices, offering limited insight into building-integrated systems. Their translation to EEIs embedded within buildings has received little attention, even though applying circular strategies at this scale could extend service life, facilitate reuse, and strengthen material circularity of buildings.

According to the Brand’s layer theory, EEIs belong to the “Service” layer of the building, which typically has a short service life; consequently, they can affect the durability of other building components with which they are integrated [28]. Despite their potential to enhance adaptability, energy efficiency, and long-term value retention, EEIs remain overlooked mainly in both policy and research discussions on building circularity. To clarify why this gap persists, it is helpful to examine how sustainability frameworks address technical systems.

International standards such as ISO 14025 [29], EN 15804 [13], ISO 20887 [30], and ISO 59020 [31] promote lifecycle disclosure, environmental declarations, and design for disassembly and adaptability. Green-building rating systems such as BREEAM, LEED, DGNB, HQE, and Level(s) [32] translate these principles into building assessments. However, within these instruments, EEIs are only marginally represented—typically under energy, controls, or automation categories—with limited emphasis on reuse, recyclability, or end-of-life management. The result is a fragmented assessment landscape: building-level rules target operational energy, while product-level policies focus on substances (e.g., hazardous substances), leaving EEI without dedicated circularity indicators. This is a major research gap: despite EEI’s central role in enabling sustainable and adaptable buildings, there is no integrated framework linking policy, certification, and lifecycle sustainability assessment for these systems.

This fragmentation is mirrored in academic research. Although lifecycle thinking is well established, few studies analyse EEIs as autonomous systems within circular-construction frameworks, and those that do broadly emphasise technical or economic performance rather than integrated sustainability. Recent works—for example, Pechlivanis et al. [33] and Hounkpatin et al. [34]—examine energy and cost performance, developing IoT-based fault detection or hybrid PV systems, but fail to link their findings to European policy frameworks or Green Building Rating System (GBRS) criteria. Similarly, Sevenster et al. [35] and Lamnatou et al. [36] highlight inconsistencies in certification and LCA methodologies, yet their analyses remain product-oriented and overlook installations within buildings. Other studies, including Dascalaki et al. [37], Ali et al. [38], and Horyński [39], examine energy, cost, or automation aspects without defining EEI-specific sustainability indicators or lifecycle metrics. Collectively, these contributions demonstrate a fragmented research landscape that lacks integration between policy, certification, and lifecycle sustainability. This fragmentation underscores the absence of a coherent conceptual and methodological framework for assessing EEI circularity, an analytical gap that the present study addresses through a combined investigation of professional practice, standards, and certification schemes.

Beyond these conceptual gaps, methodological trends also show certain limitations. Recent studies on sustainability and smart-building technologies conducted across diverse contexts have typically employed survey-based methods, often complemented by simulations or literature reviews, to evaluate professional perceptions of energy efficiency, comfort, and technology adoption. Most target architects, engineers, and construction professionals, with sample sizes ranging from small expert panels of around 30 respondents [40] to large-scale surveys of over 300 participants [41]. While these approaches effectively capture practitioner insights, they remain primarily focused on operational performance indicators, such as energy management and automation, without extending the analysis to lifecycle sustainability or circularity. For example, Adu Gyamfi et al. [42] surveyed 80 Ghanaian architects on green building technologies, finding high familiarity with energy-efficient windows, daylighting, HVAC systems, solar technology, and rainwater harvesting. Reported benefits included improved ventilation and reduced emissions, but lifecycle circularity aspects were not addressed. Rumondang et al. [43] combined passive lighting simulation of light pipes, mirror ducts, and light shelves with a survey of 209 respondents in Indonesia. While the study found widespread recognition of natural lighting benefits, adoption of passive lighting remained low due to limited awareness, and no attention was given to reuse or lifecycle integration [43]. Building on these methodological precedents, the present research applies survey and interview methods to explore how professionals in the Belgian construction sector integrate circular principles into EEI design and procurement.

Taken together, this body of literature confirms that EEIs remain largely absent from circular-construction research, despite their pivotal role in enabling sustainable and circular buildings. This underrepresentation reveals a persistent disconnect between lifecycle studies and practice, highlighting the need to explore how design-stage professionals perceive and implement circularity in EEI. Accordingly, this study adopts a bottom-up, mixed-methods approach—combining survey and interview data from the Belgian construction sector—to uncover how professionals interpret, implement, and challenge circularity in EEIs, thereby informing future frameworks and certification schemes.

3. Methodology

3.1. Scope of the Research

The scope of this study focuses on the design stage of EEIs. At this stage, various sustainability and circularity aspects can be considered in relation to different phases of the EEI lifecycle, from production to end-of-life and beyond. Certain aspects can be addressed directly during the design stage, such as selecting energy-efficient devices or using materials from recycling or reuse. Other aspects can be planned for future implementation, for example, through the application of design for disassembly (DfD) principles. Accordingly, this study considers sustainability and circularity strategies that professionals can design or plan before the practical installation of EEI components. The study specifically targets EEIs within buildings.

3.2. Research Design

This study adopts a mixed-methods research approach to explore how sustainability and circular economy (CE) are understood and applied in EEIs, with a particular focus on the Flemish construction sector in Belgium. The research combines quantitative data from a questionnaire with qualitative insights from semi-structured interviews.

A structured online survey gathered insights from construction professionals (see Supplementary Material S1), including architects, engineers, and consultants, and the findings were subsequently integrated and validated through five semi-structured interviews based on a predefined question set (see Supplementary Material S2).

The quantitative approach allows the researcher to examine the relationship between variables using systematic and replicable methods that enhance generalizability and reliability [44]. The qualitative approach has a degree of flexibility and openness that facilitates the understanding of different contexts and related uncertainties [44], enabling the collection of tacit knowledge provided by participants that cannot be represented through numerical data [45], and the inclusion of subjects not following objective rules, for example, decision-making processes by professionals [46]. Combining both methods strengthened the overall understanding and enhanced empirical robustness.

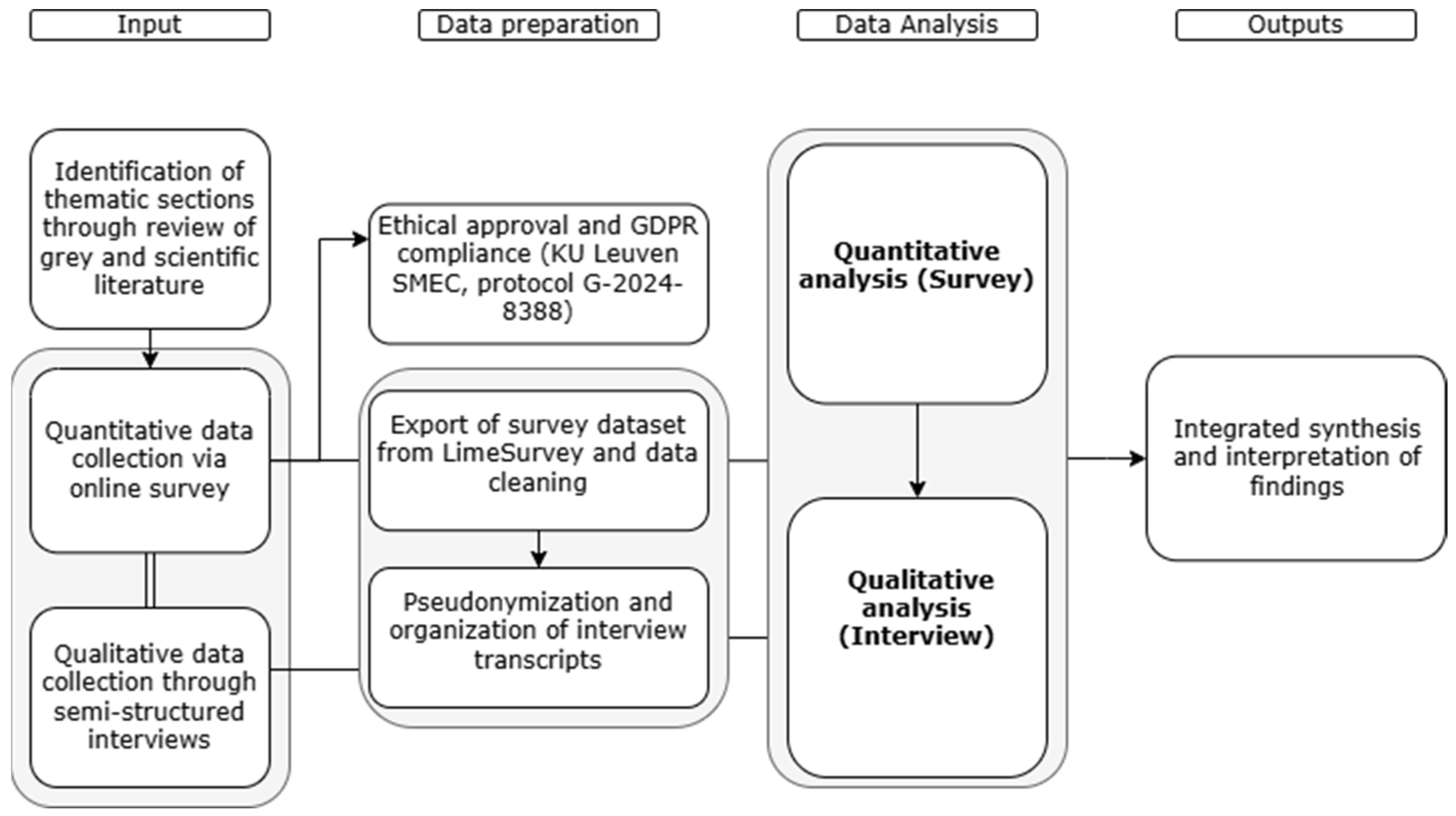

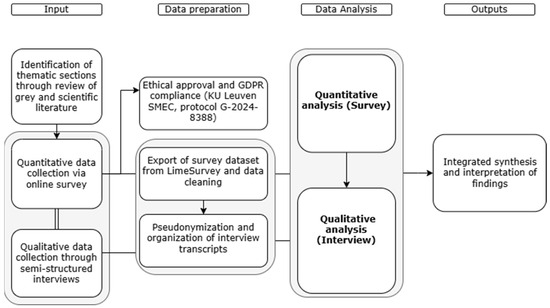

As illustrated in Figure 1, the research proceeded in three main stages:

Figure 1.

Overview of the study methodology. The study was conducted within the E-construct project (funded by VLAIO-Flanders Innovation & Entrepreneurship).

- Identification of thematic sections based on review of the grey literature and framework review.

- Empirical data collection via an online survey provides quantifiable insights into professional perceptions and practices.

- Semi-structured interviews with volunteers from the survey sample.

3.3. Stage 1—Identification of Thematic Sections

The first stage aimed to identify the main thematic sections through a review of the academic and grey literature related to sustainability and circular construction, including relevant policy documents, regulatory standards, and technical guidelines. This exploratory step established preliminary analytical categories that informed the subsequent survey and interview instruments.

A comparative conceptual analysis integrated the following:

- (i)

- Recurring EEI sustainability and circularity clusters identified in the scientific literature;

- (ii)

- International and European standards and directives (e.g., ISO 20887, EN 15804, RoHS, WEEE, ESPR);

- (iii)

- The criteria families of Green Building Rating Systems (GBRSs)—such as BREEAM, LEED, and DGNB.

Sources were included based on explicit reference to sustainability or circular-economy strategies applicable to the design, use, or end-of-life of EEI components. Recurring concepts across academic research, regulations, and GBRSs were consolidated into seven thematic clusters: (1) lifecycle awareness, (2) standards and certifications, (3) digital tools, (4) circular business models, (5) design adaptability, (6) collaboration dynamics and barriers, and (7) stakeholder involvement. These clusters formed the conceptual foundation for the empirical work.

3.4. Stage 2—Empirical Data Collection

3.4.1. Survey Design and Implementation

Building on the conceptual framework established in Stage 1, a 36-item online questionnaire combined multiple-choice and five-point Likert-scale questions. Conditional logic ensured respondents viewed only relevant follow-up items (e.g., digital tool use or GBRS experience). This design operationalised the conceptual framework and ensured consistency with the subsequent qualitative phase.

3.4.2. Survey Distribution

The survey was distributed via LimeSurvey between November 2024 and May 2025 through academic and professional networks, including LinkedIn and direct outreach to Flemish construction firms. It was available in English and Dutch (Flemish) with identical wording. The target population included architects, engineers, and consultants active in the Flemish construction sector, as early design and procurement decisions largely determine electrical system choices. Participation was voluntary and anonymised in accordance with GDPR and KU Leuven’s ethical guidelines.

3.4.3. Survey Data Analysis

Survey responses were collected via LimeSurvey, yielding 32 valid entries from professionals in architecture, engineering, consultancy, and sustainability roles. Data were pseudonymised in compliance with GDPR and KU Leuven’s ethical protocols. Descriptive analyses identified central tendencies, frequency distributions, and patterns across roles, education, and company sizes. The seven thematic clusters from Stage 1 guided both quantitative analysis and the formulation of interview questions, ensuring conceptual and methodological coherence across the mixed-methods design.

3.5. Stage 3—Semi-Structured Interviews

3.5.1. Interview Design

To complement the quantitative findings, a qualitative phase was conducted through semi-structured interviews to clarify underlying mechanisms and provide contextual depth. This flexible method allowed participants to elaborate on their perspectives, offering an in-depth understanding of the research topic and revealing issues not captured through quantitative analysis [47,48]. In this study, the interviews aimed to capture practitioners’ reasoning, decision-making dynamics, and lived experiences that quantitative metrics alone could not fully reveal.

3.5.2. Interview Administration

Of the 32 survey respondents, five volunteered for follow-up semi-structured interviews representing diverse professional backgrounds, including sustainable design, prefabrication, digitalisation, and circular procurement. These interviews provided conceptual saturation across stakeholder perspectives rather than statistical generalisation.

Interviews were conducted online (30–45 min each) in English, with informed consent and full GDPR compliance under KU Leuven’s ethical protocol. Discussions followed a flexible guide structured around three elements:

- The seven thematic sections derived from Stage 1 provide a common conceptual framework;

- Patterns observed in the survey results that required further clarification;

- The sub-research questions guiding the study.

This structure enabled in-depth exploration of professional experiences and EEI decision-making. Discussions addressed five topics: (1) professional background and project types; (2) sustainable practices, including energy efficiency and reuse; (3) digital tools such as BIM and material databases; (4) circular business models, including leasing and take-back systems; and (5) collaboration and decision-making within project teams.

Given the exploratory nature of the study, a manual thematic synthesis was applied. Notes and transcripts were organised by the predefined survey themes, capturing emerging issues such as client demand, financial constraints, and regulatory uncertainty. The qualitative insights contextualised the quantitative results, explaining why digital tools remain underused or reuse strategies face client resistance.

3.6. Data Protection and Availability

Ethical approval was obtained under KU Leuven protocol G-2024-8388. All participation complied with GDPR and institutional ethics requirements. Identifiable data were used solely for classification and then pseudonymised. A pseudonymised version of the dataset and interview summaries is available upon reasonable request via the KU Leuven repository, subject to privacy guidelines.

4. Results

This section presents the findings from both the questionnaire and semi-structured interviews. It begins with the demographics and background of the survey respondents (Section 4.1), followed by the main thematic results. For all Likert-scale items, responses are shown both as full distributions and as top-box percentages, indicating the proportion of respondents who selected the highest categories (e.g., “very/extremely important,” “very much/completely,” or “often/always”).

4.1. Respondent Demographics and Company Background

The sample consisted of 32 professionals representing a range of professional roles and education, as well as company size, field, and project type. As shown in Table 1, respondents were mainly employed in medium-sized firms, covering diverse fields and project types, with most having experience in residential and commercial projects. Educational backgrounds spanned architecture, civil engineering, and electrical engineering. Professional roles included architects, engineers, and consultants, reflecting a balanced mix of design and technical expertise across the construction sector.

Table 1.

Respondents’ demographics and professional characteristics, including roles, educational background, company size, company expertise, and project types.

4.2. Lifecycle Stage Consideration and Environmental Impact Awareness

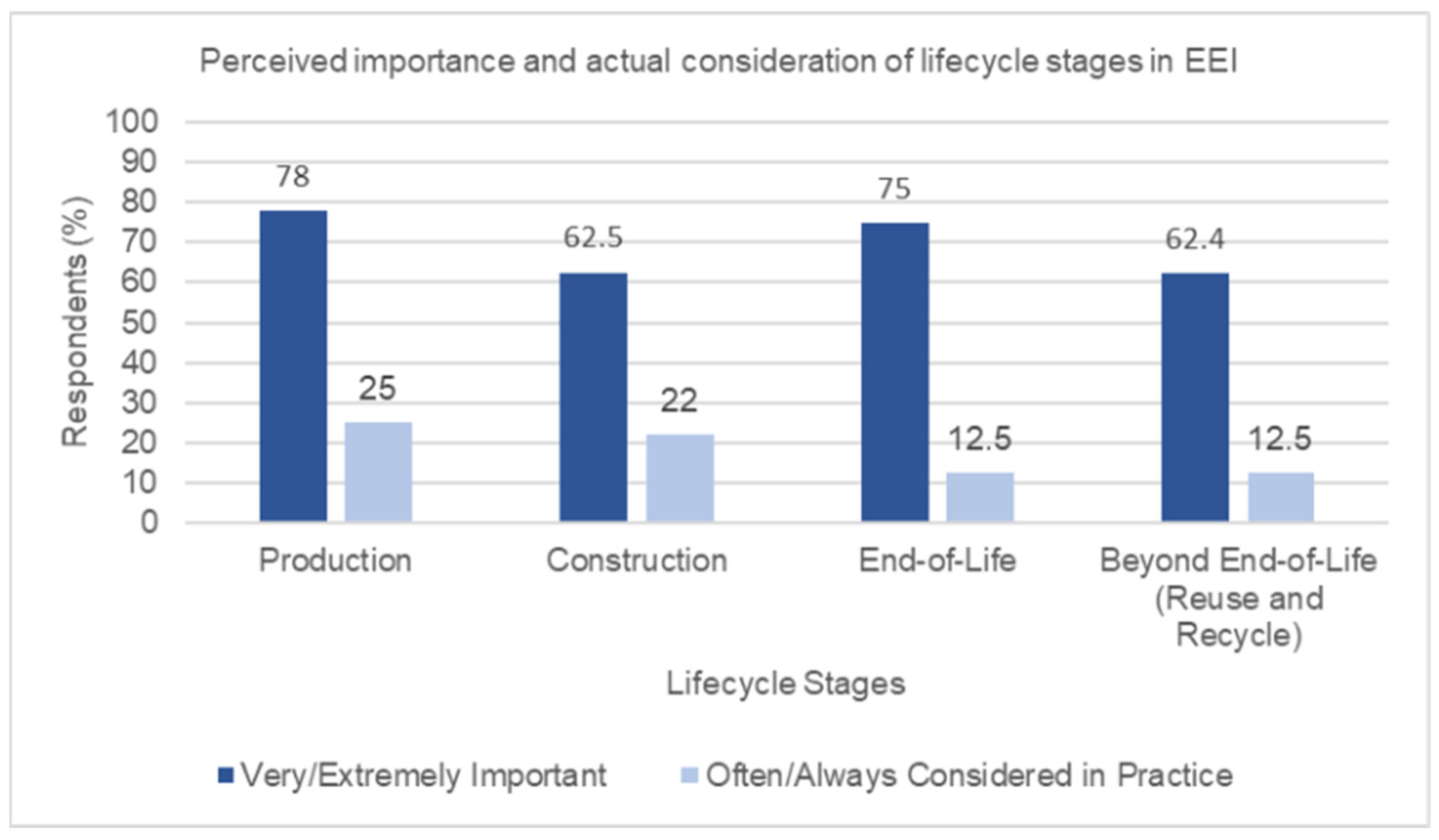

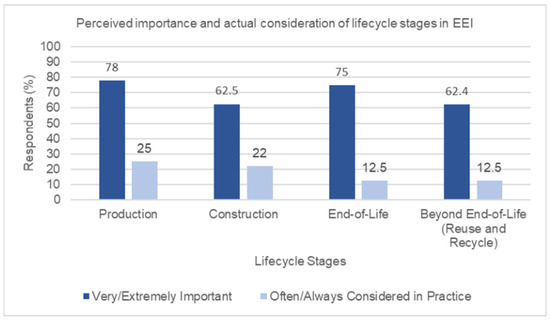

Survey results indicate a clear imbalance in how different lifecycle stages are valued and applied in EEI design (Figure 2). The analysis followed the EN 15804 framework, distinguishing production, construction, use, end-of-life (EOL), and beyond end-of-life stages. To map concrete practices, the survey linked lifecycle stages to specific EEI strategies: production (low-/zero-carbon wiring and selective reuse of components), construction (modular or prefabricated systems; use (LED lighting, PV panels, EV charging points), end-of-life (DfD; for beyond end-of-life, urban mining).

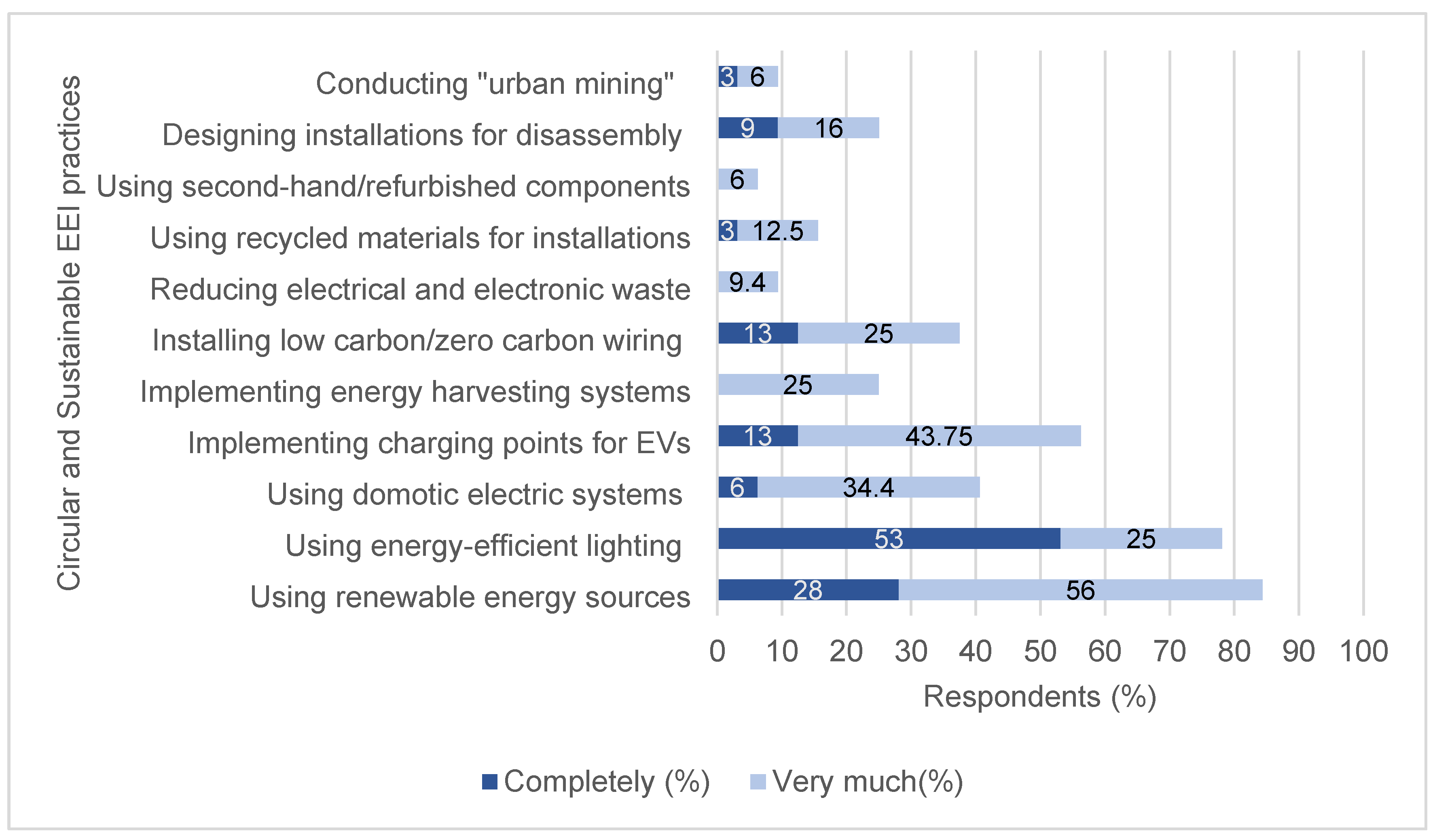

Figure 2.

Perceived importance versus practice of lifecycle stage considerations in electrical installations.

Use-stage aspects dominated: operational energy (96.9% very/extremely important) and maintenance (100%) were also most frequently acted upon (62.5% and 65.6% reporting often/always), reflecting the sector’s focus on operational performance and regulatory compliance. By contrast, production (78% importance vs. 25% practice) and construction (62.5% vs. 21.9%) aspects were less frequently applied. The most significant gaps occurred at end-of-life (75% vs. 12.5%) and beyond end-of-life (62.5% vs. 12.5%).

These results highlight a systematic implementation gap between awareness and practice. While professionals broadly recognise the importance of all lifecycle stages, practical integration remains limited. This aligns with regulatory emphasis on operational efficiency (e.g., EPBD) versus the voluntary nature of production/EoL instruments (e.g., EPDs, WEEE). The neglect of these stages suggests that critical circular strategies, such as design for disassembly, reuse of components, and urban mining, are still peripheral in everyday EEI practice.

To map concrete practices, the survey linked lifecycle stages to specific EEI strategies: for production, low-/zero-carbon wiring, selective reuse of components; for construction, modular or prefabricated systems; for use-stage, LED lighting, PV panels, EV charging points; for end-of-life, DfD; for beyond end-of-life, urban mining. The next section therefore turns to concrete practices, identifying where adoption is strongest and where emerging innovations (e.g., DfD, component reuse) may close the gaps.

4.3. Current and Emerging Circular Practices in EEI

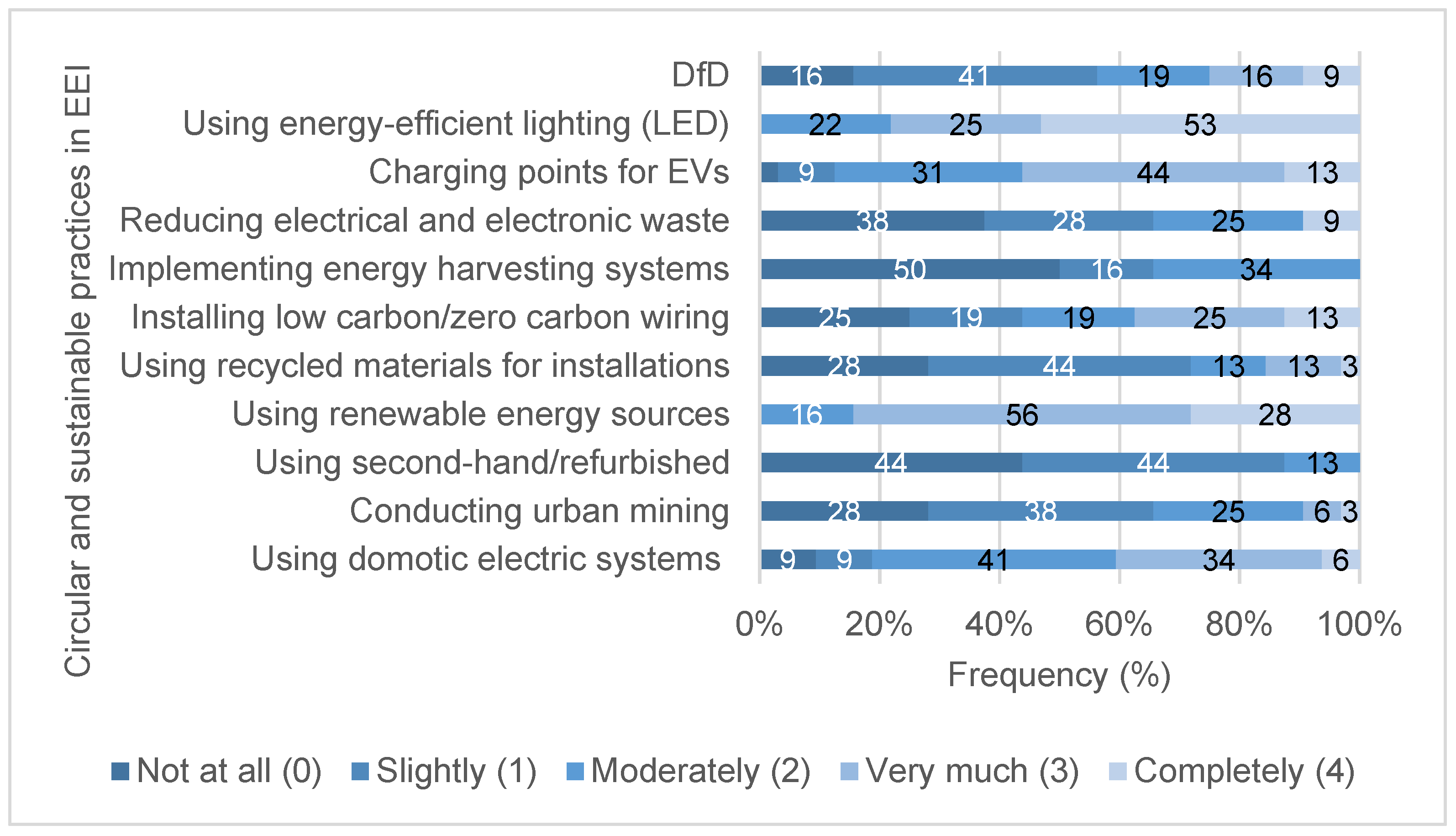

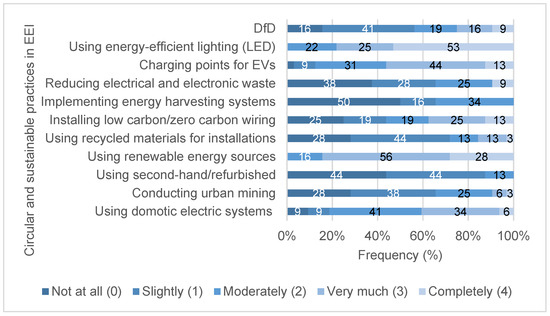

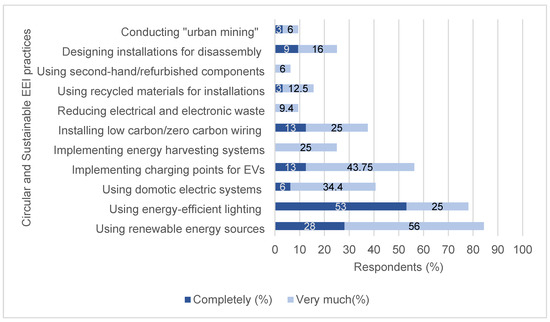

Compared to the previous section, this section turns to concrete practices, identifying where adoption is strongest and where emerging innovations (e.g., DfD, component reuse) may close the gaps. Survey results, as shown in Figure 3, show that LED lighting achieved the highest top-box result: 53% “completely” implemented in projects, while EV charging points in 56% (“very much” or “completely”), on-site renewables were reported as “completely” implemented in 28%, while low/zero-carbon wiring remained less common (12.5% “completely”).

Figure 3.

Frequency of implementation of selected circular and sustainable practices in EEI, based on survey responses.

Furthermore, 28% of respondents consistently integrated renewable energy sources such as solar energy and heat pumps into their projects. This relatively high rate likely reflects recent Flemish energy regulations requiring that at least 15 kWh/m2 of annual energy use in new buildings be supplied by photovoltaic panels, and at least 20 kWh/m2 in deeply renovated buildings by renewable energy sources, including the option of photovoltaic panels [49]. EV charging points also showed a strong level of implementation, with 12.5% of respondents indicating “completely” and almost 44% indicating “very much”.

By contrast, circular strategies lagged: DfD reached only 9.4% “completely” and 15.6% “very much,” while second-hand components and e-waste reduction had even lower top-box values (<10%). These results demonstrate that, while energy-efficiency measures are mainstream, advanced circular practices rarely reach the top categories of implementation.

During the interviews, additional insights emerged on the implementation of circular and sustainable EEI practices. Energy-efficient technologies were widely described as standard practice (e.g., “We always include LED and PV by default,” Interviewee 2). Circular strategies appeared only in isolated cases. For example, reuse, such as retaining lighting frames, was constrained by missing documentation, warranty concerns, and client reluctance. DfD was recognised as relevant but rarely applied due to time, cost, and limited familiarity. A few modular/demountable examples were cited (Interviewees 3, 5). Certification gaps and restrictive procurement procedures reinforced risk-averse preferences for new products.

Overall, interviews confirmed survey patterns: energy-efficient EEI is mainstream, while circular practices remain rarely applied.

4.4. Familiarity with Circularity-Related Standards and Certifications

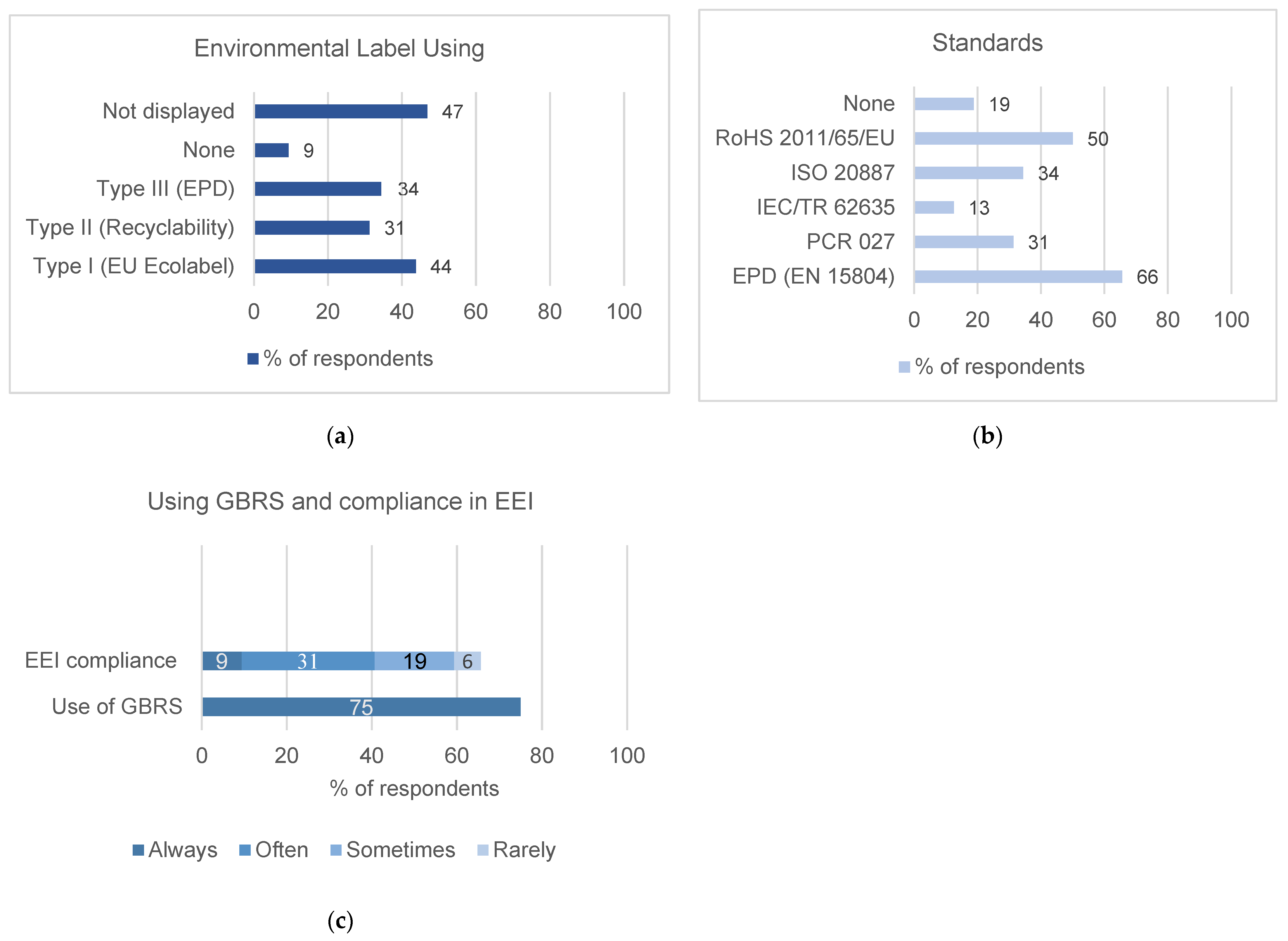

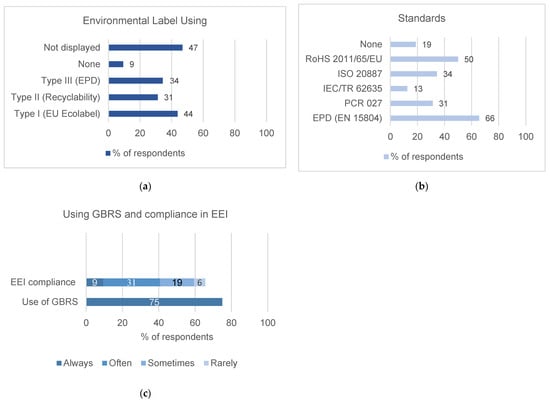

This section focuses on relevant standards, certifications, and environmental labels providing the reference framework for EEI sustainability. Technical standards (e.g., ISO 20887, EN 15804) provide a conceptual framework and an indication of how to measure performance, such as lifecycle assessment rules. Environmental labels, by contrast, are communication tools that indicate a product’s environmental performance, allowing designers and consumers to make informed choices. They are typically voluntary and issued under the ISO 14020 family [50,51]. According to ISO 14020 [50], three main types of environmental labels can be distinguished: Type I: third-party verified ecolabels (e.g., EU Ecolabel) based on multiple environmental criteria; Type II: self-declared environmental claims (e.g., recyclability symbols or “low-VOC” labels); and Type III: Environmental Product Declarations (EPDs), which provide quantified lifecycle data according to Product Category Rules (PCRs) Among the ecolabels, the EU Ecolabel, managed by the European Commission [51], and the official EU-wide Type I ecolabel. It recognises products and services that demonstrate environmental excellence throughout their lifecycle, including electronic equipment. On the other hand, EPDs provides verified information on a product’s environmental impact across its entire life cycle, in compliance with EN 15804. PCRs for developing EPD of EEI components have been recently published, e.g., for electric vehicle charging infrastructures, and electrical cables and wires, providing a harmonised framework for assessing the environmental performance of electrical products within the construction sector.

Certifications through GBRSs (e.g., BREEAM, LEED, DGNB) operate at the building level, verifying compliance with broader sustainability criteria across design, construction, and operation phases. They apply broader sustainability criteria, with limited consideration of EEI.

For environmental labels, as shown in Figure 4a, Type I and Type III (EPDs) were the most used (~40% “often/always”), while Type II was least used (≥40% “rarely/never”). In total, 59% reported using electrical products with some label, but awareness remained uneven. Respondents were most familiar with Type I (EU Ecolabel, Cradle to Cradle) and Type III (EPDs), while Type II (recyclability symbols) was least integrated.

Figure 4.

Reported experience with (a) environmental labels (Type I–III), (b) standards and directives relevant to EEI (EN 15804, PCR, IEC/TR 62635, ISO 20887, RoHS), and (c) reported experience with Green Building Rating Systems (GBRSs) and frequency of ensuring electrical installations comply with GBRS requirements.

For standards, as shown in Figure 4b, EN 15804 (EPDs) showed the strongest reported experience (66%), followed by RoHS (50%), ISO 20887 (DfD/adaptability, 34%), Product Category Rules (PCRs) for cables/wires (31%), and IEC/TR 62635 [52] (EoL, 12.5%). Survey results shown in Figure 4c indicated that three-quarters (75%) had worked on projects pursuing GBRSs (e.g., BREEAM, LEED), yet only 9% reported that they “always” ensured electrical systems complied with GBRS requirements, and 31% said “often.” This shows inconsistent translation into EEI design.

Interviews confirmed these survey findings. Frameworks such as EN 15804 or RoHS were relatively well known, but their translation into procurement decisions was limited. One participant noted that procurement rules could play a more decisive role, as sustainability criteria in tenders often remain too generic or complex (Interviewee 4). Consultants stressed that while EPDs are useful where available, many EEI components lack transparent data.

Only 34% reported using ISO 20887 consistently in practice when asked about regular application, highlighting its limited uptake. National tools such as TOTEM and GRO were also widely known and used for general sustainability assessments. Nevertheless, interviewees emphasised that these tools do not currently include EEI-specific modules, which makes systematic integration difficult. In summary, exposure to standards and certifications was relatively high, but systematic application in EEI practice was low.

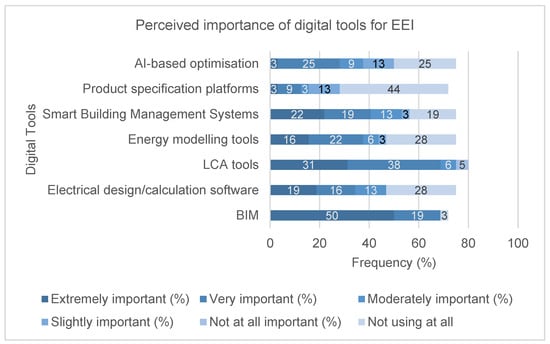

4.5. Use and Perceived Value of Digital Tools

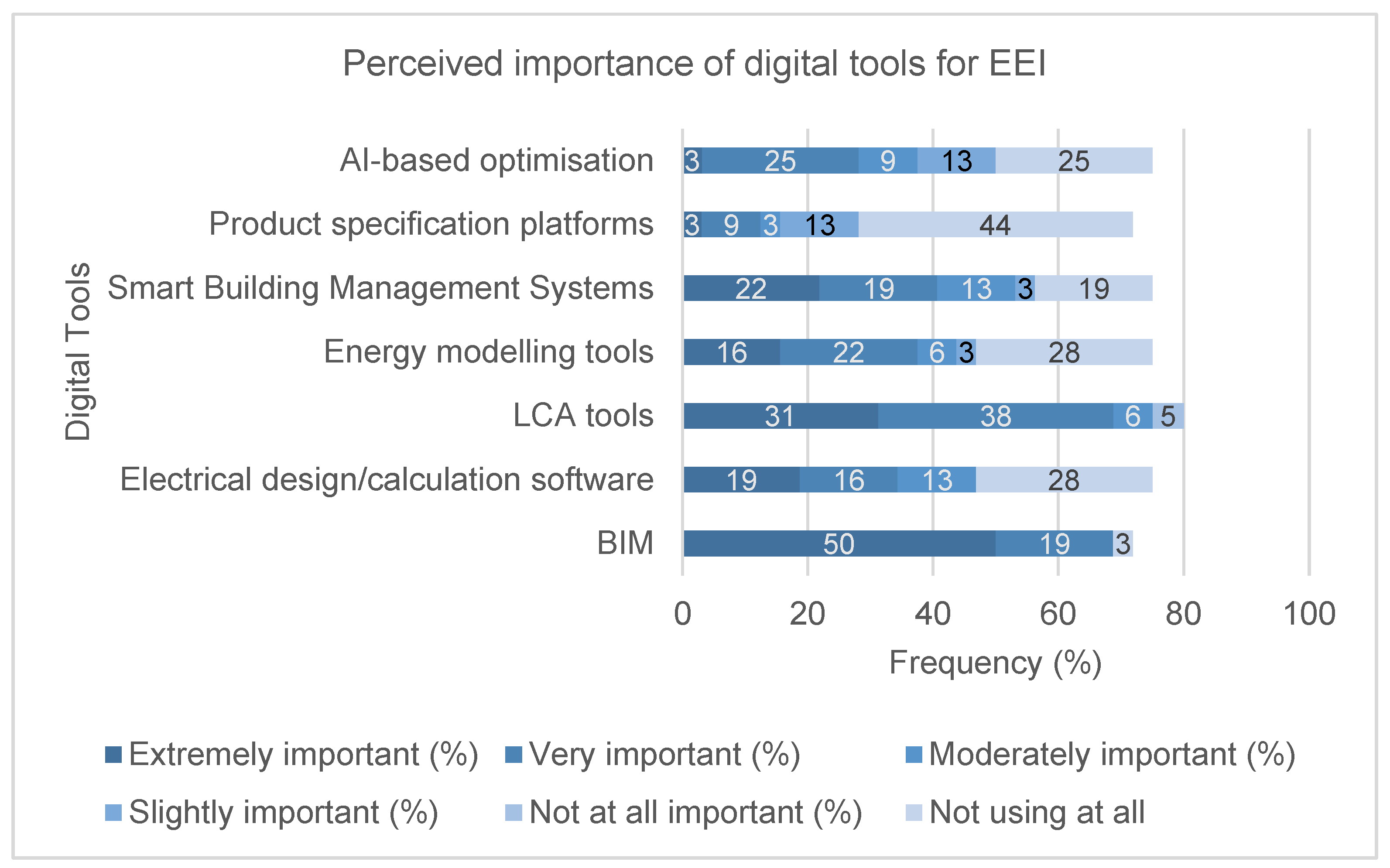

Survey results demonstrate that about 72% of respondents used digital tools for EEI. As shown in Figure 5, BIM stands out, with 69% rating it very/extremely important. Other tools were rated more modestly: LCA tools (31% extremely; 37.5% very important), energy modelling (16% extremely; 22% very), Building Management Systems (e.g., Honeywell BMS, Schneider EcoStruxure) (22% extremely; 19% very), AI-based optimisation (25% very), and product specification platforms (3% extremely; 9% very).

Figure 5.

Perceived importance of digital tools for circular EEI. (Note: Some items were not displayed to all respondents due to filtering; proportions are reported on the displayed base).

The survey reported barriers, including absence of obligations to use such tools (62.5%), time constraints (37.5%), lack of knowledge (31%), and licencing costs. This is further confirmed by interviewees, who noted that EEI is often under-prioritised compared with HVAC in whole-building tools, and that national LCA tools (e.g., TOTEM) do not yet adequately capture EEIs (Interviewees 1–2).

Interviewees corroborated these findings. BIM was highlighted for modular design and component tracking, though it was noted to be rarely applied to circular EEI in practice (Interviewee 1). In some cases, BIM was also used for material or building passports. Another participant described digitalisation as the “tool of the future.”

For other tools, LCA software (e.g., SimaPro, One Click LCA) received the highest recognition (31% extremely important; 37.5% very important). Interviews confirmed this but noted that many EEI components remain a “black box” due to missing EPDs and manufacturer data (Interviewee 5). Energy modelling, smart building management, AI-based optimisation, and product databases were acknowledged but less prioritised.

Furthermore, while BIM and LCA tools were perceived highly important, interviews indicate that they are not yet routine in EEI practice due to regulatory gaps, data limitations, and costs.

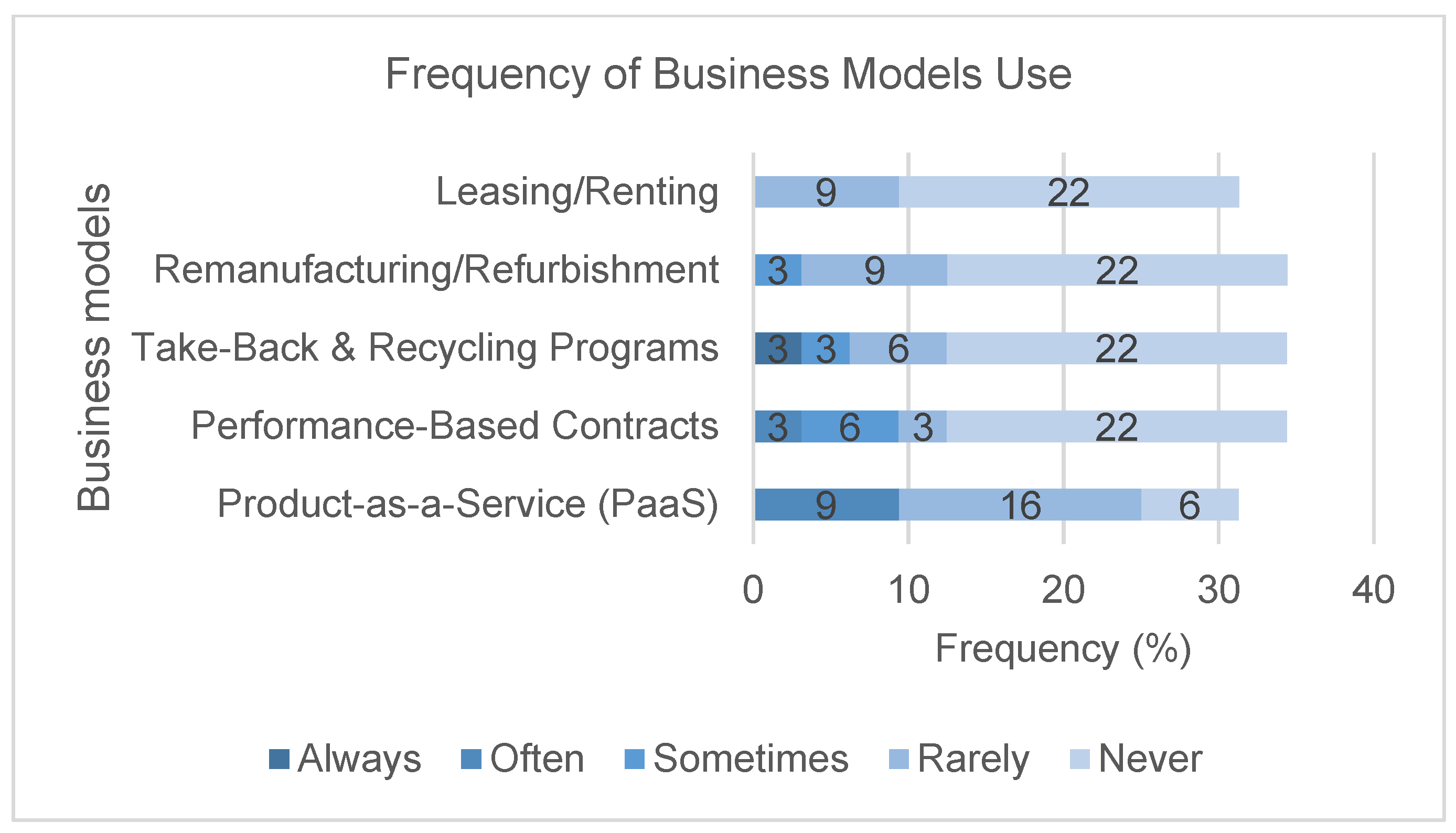

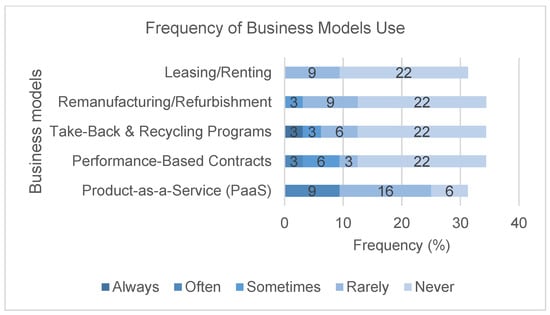

4.6. Knowledge and Adoption of Circular Business Models

Survey results showed limited adoption of circular business models in EEI projects. Product-as-a-Service (PaaS) was the most cited (53%), but top-box adoption (“often/always”) was far lower when follow-up frequencies were considered. This indicates that while awareness exists, consistent practice is still marginal.

Because the survey used conditional logic, only respondents who indicated adopting at least one model (n = 23) saw the frequency questions. Percentages in Figure 6 therefore use this displayed base (n = 23) for the “always/often/sometimes/rarely/never” categories.

Figure 6.

Adoption of circular business models in electrical installations. (Note: Data are not displayed as 100% stacked because base sizes differ across business models. Percentages reflect the share of total respondents who reported using each model (n = 23)).

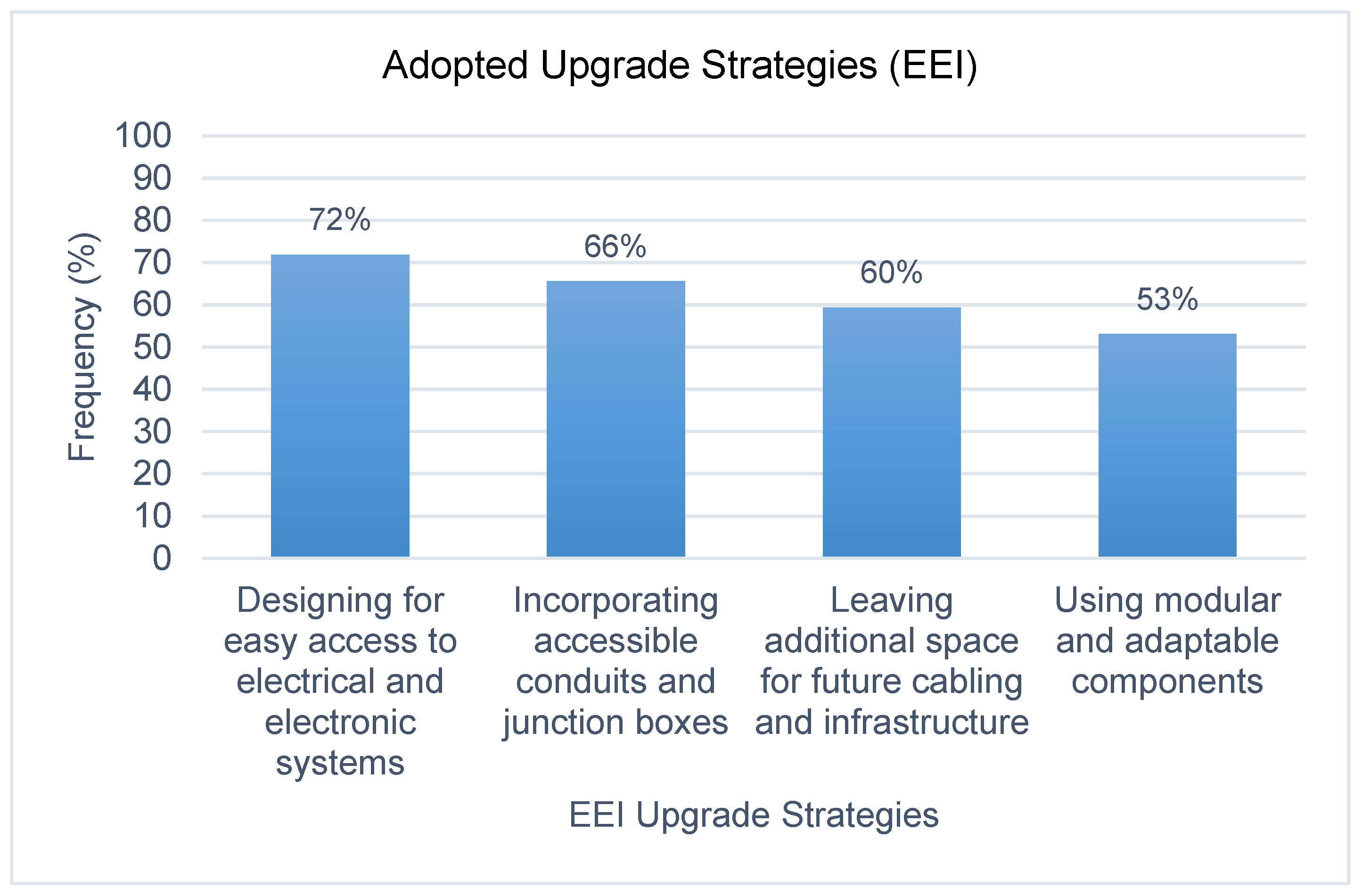

4.7. Futureproofing and Design Adaptability Strategies

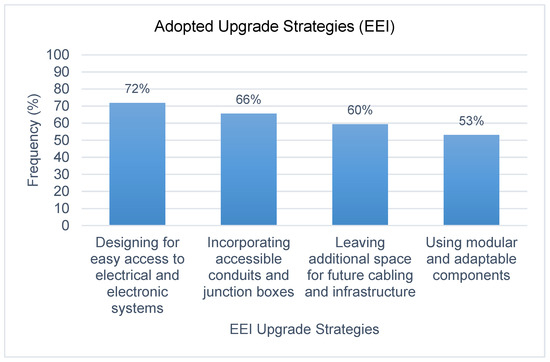

Survey respondents reported frequent use of strategies to accommodate upgrades in electrical installations (Figure 7). The most common strategies reached relatively high top-box adoption: easy access (72%), conduit/junction boxes (66%), and space for future cabling (59%). Modular/adaptable components reached just over half (53%). These figures suggest that while future-proofing is already integrated, more innovative strategies like energy harvesting remain uneven.

Figure 7.

Survey results on strategies adopted to facilitate upgrades in electrical installations.

Respondents also identified energy-harvesting systems (e.g., solar panels, thermal energy, and kinetic solutions —referring here to systems that generate small amounts of electricity from motion or vibrations) as part of future-proof EEI strategies. Their perceived benefits were strong: 84% highlighted contributions to sustainability and environmental impact reduction, 69% mentioned lower operational energy costs, and an equal share reported enhanced building performance. Around half also cited positive client demand (47%) and access to government incentives (47%).

At the same time, adoption remains uneven due to persistent challenges. The most frequently cited barriers were space and layout constraints (69%), high upfront costs (53%), and client preferences for traditional systems (37.5%).

Interviews aligned with these findings. Examples included prefabricated, demountable “energy boxes” (Interviewee 1, 3), conduits and modular trays used in a few projects (Interviewee 5), and PV systems linked to take-back schemes (PV-Cycle) and future building-level buffering (Interviewees 4, 5).

In sum, future-proofing strategies such as accessible design and modular components are relatively common, while energy-harvesting systems are recognised for their potential but face cost, space, and cultural barriers.

4.8. Collaboration Dynamics and Perceived Drivers and Barriers

This section examines stakeholder roles in decision-making, levels of involvement in circular EEI projects, and their perspectives on achieving greater circularity, with particular attention to the drivers and barriers they identified.

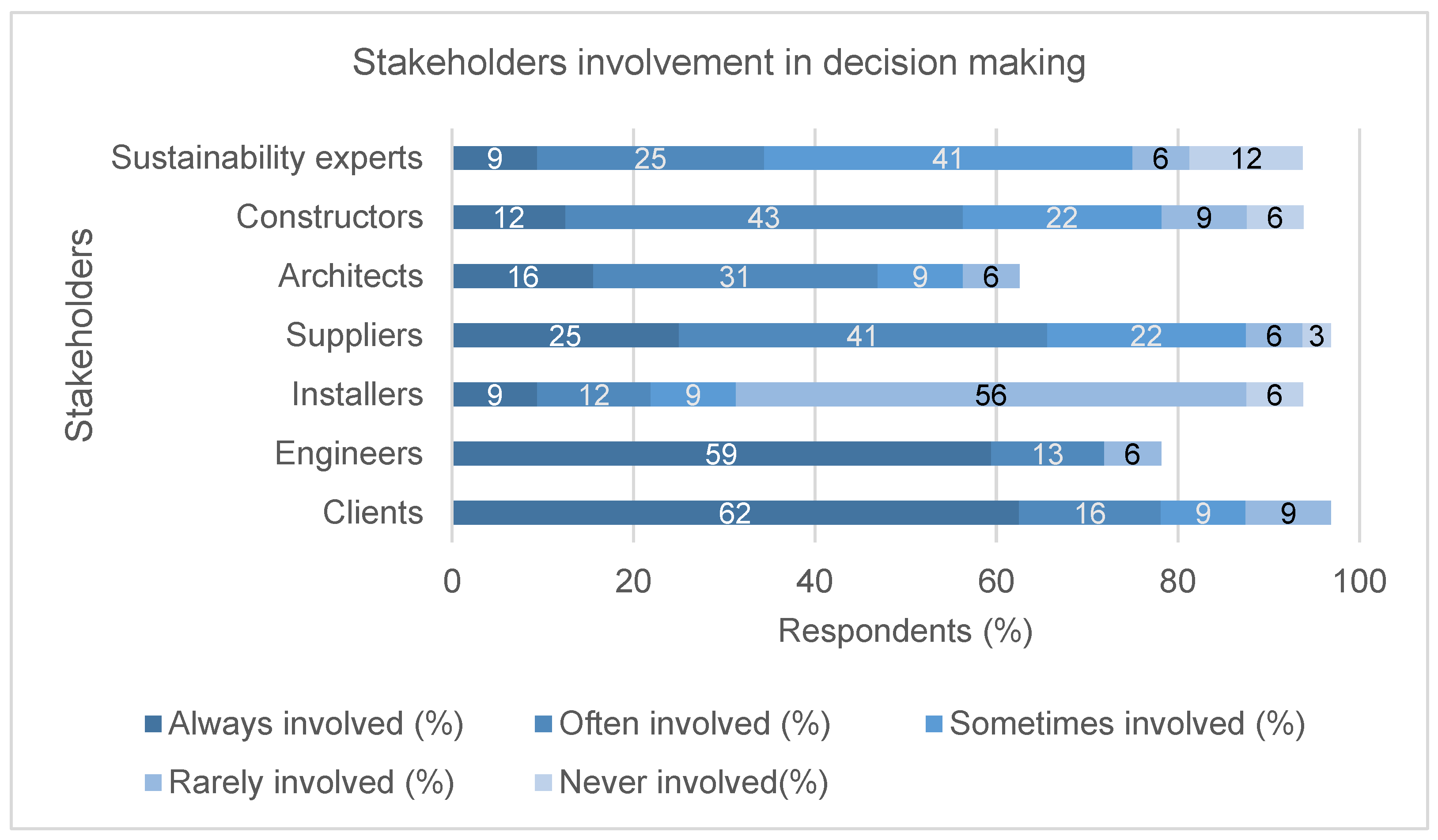

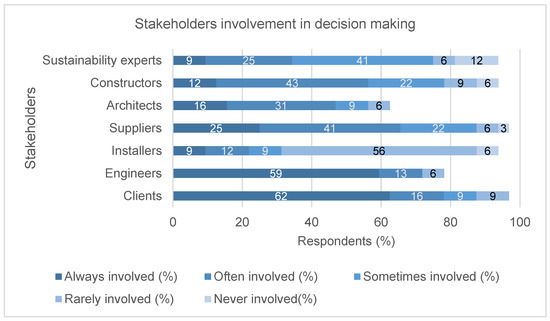

4.8.1. Stakeholders Involvement

The survey also examined how different stakeholders are involved in decision-making on circular EEI. Figure 8 shows that clients and engineers reached the highest top-box shares (“always/often” involved), while installers and sustainability experts had consistently low values, reflecting their late or peripheral involvement.

Figure 8.

Reported involvement of stakeholders in circular and sustainable EEI decision-making.

By contrast, installers were often absent from early project phases: 56% reported them as rarely involved, and only 9% as always involved. Other stakeholders showed mixed patterns. Suppliers: 25% always, 41% often; architects: 16% always, 31% often; constructors: 12.5% always, 44% often. Sustainability experts were least embedded (9% always, 25% often), indicating peripheral, project-dependent roles.

Interviews corroborated these patterns and emphasised that the timing of involvement strongly shapes outcomes. Installers were often consulted too late, limiting opportunities to integrate circular solutions at the design stage (Interviewee 5). In contrast, one example described early co-creation where installers and suppliers contributed to a prefabricated, demountable energy box (Interviewee 3). Sustainability experts were typically involved too late, often in an advisory rather than design role (Interviewees 1, 5). The other participant linked these dynamics to procurement structures, noting that earlier engagement (e.g., via design-and-build contracts) could improve circular outcomes (Interviewee 5). Beyond the roles of stakeholders, the survey also examined involvement in specific EEI practices (Figure 9). Respondents reported high engagement in decision-making for energy-efficient lighting and renewable energy systems (both 59%). In contrast, more advanced circular practices showed lower involvement in decision-making: DfD (31%), urban mining (31%), and component reuse (28%).

Figure 9.

Respondents’ involvement in decision-making regarding circular and sustainable EEI practices. (n = 32).

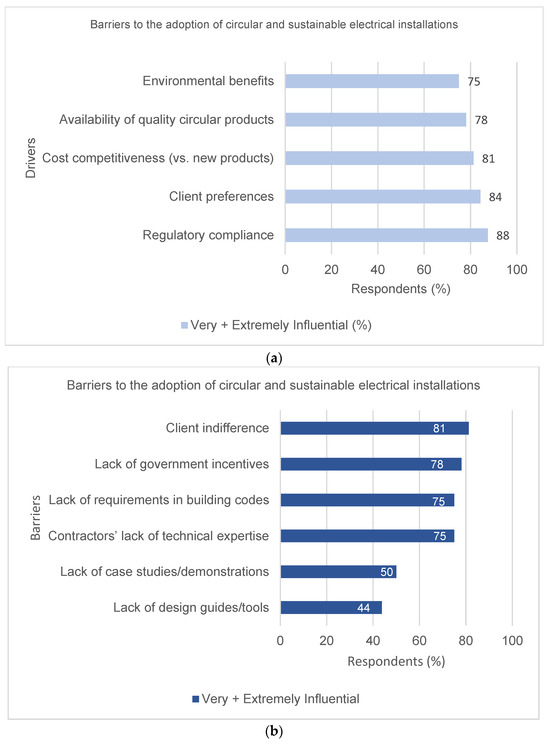

4.8.2. Perceived Drivers and Barriers to Circularity in EEI

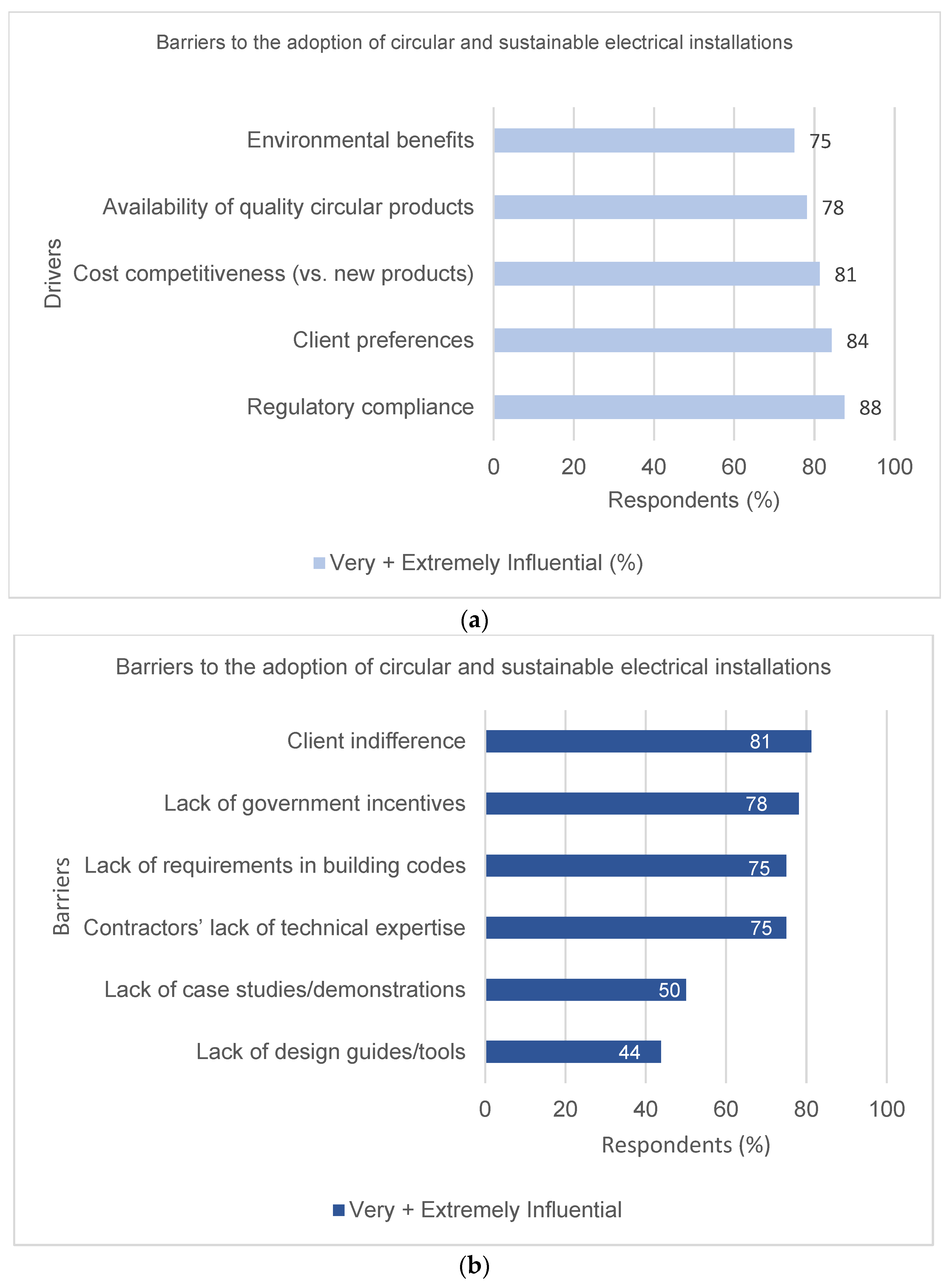

Among the drivers, regulatory compliance (87.5%) and client preferences (84%) were most frequently cited. Cost competitiveness of reused products compared to new alternatives was also influential (81%). Availability of quality circular products (78%) and environmental benefits (75%) were also perceived as important drivers. (Figure 10a). At the same time, survey respondents identified several barriers. As presented in Figure 10b, client indifference (81%) ranked highest, alongside the lack of government incentives (78%), insufficient requirements in building codes (75%), and limited contractor expertise (75%). Additional obstacles included lack of case studies (50%) and the lack of dedicated design guides or tools (44%).

Figure 10.

Perceived drivers (a) and barriers (b) influencing circular EEI.

Interview findings reinforced these patterns. Participants frequently cited client indifference, lack of incentives, and high upfront costs. Technical uncertainties (e.g., missing guarantees and certifications for reused components), and limited contractor/design knowledge were also noted, reinforcing risk-averse behaviour. As one participant stated, “There’s no system in place to test and re-certify reused electrical parts” (Interviewee 5). Another emphasised client influence: “Design for disassembly is easier than reuse, but it only happens if the client pushes for it” (Interviewee 1). Drivers are mainly regulatory, economic, and client-related, while barriers reflect financial, regulatory, and trust-related concerns.

4.9. Supplementary Statistical Analyses

By education, respondents with engineering and environmental science backgrounds reported higher involvement in sustainability-related decision-making, and those with engineering backgrounds more often identified a lack of time as a barrier to using digital tools.

By company size, medium-sized firms were more likely to report not using circular business models, while small firms placed greater emphasis on designing for easy access and maintenance. No significant variations appeared across professional roles, although engineers tended to rate low-emission materials and ease of disassembly slightly higher in importance.

Regression analyses reinforced these patterns: company size and education emerged as the most influential predictors. Smaller firms consistently showed greater engagement with circular and sustainable practices (p < 0.05), while respondents from engineering and environmental science fields were more active in sustainability-related decision-making (p ≈ 0.03–0.04). GBRS experience had a positive but limited effect, mainly increasing the implementation of energy-harvesting systems (p ≈ 0.01). The professional role did not significantly affect outcomes once other factors were controlled. All statistically significant and near-significant associations are summarised in Tables S1 and S2 (Supplementary Material S3).

5. Discussion

This section discusses the findings through guiding research questions (RQ1–RQ3), drawing on seven themes and situating them within the existing policies, standards, and literature.

5.1. Sustainability and Circularity in the EEI Lifecycle

Regarding RQ1 (“How are sustainability and circular economy principles applied by professionals across the lifecycle of EEI?”), two critical themes emerge: (i) the gap between lifecycle awareness and practice; and (ii) the lack of adoption of circular practices such as DfD and reuse.

The results indicate that lifecycle thinking is broadly recognised but applied unevenly across different stages. Professionals consistently emphasised the use stage (i.e., operational energy, maintenance), while production and end-of-life are rarely operationalized in project practice. This pattern reflects the tendency, widely noted in the CE literature, for operational stages to dominate due to regulatory incentives, while production and end-of-life remain underdeveloped.

Moreover, direct reuse of EEI components was perceived as a high-risk strategy, due to missing testing protocols, unclear liability, and limited certification pathways, consistent with the literature noting the difficulty of guaranteeing safety and compliance without certified performance and traceable product data [53]. This underscores governance gaps as structural barriers, even where technical feasibility exists.

Although practical adoption of circular EEI strategies remains uneven, the findings also reveal positive entry points. Lifecycle thinking is widely recognised as important, even if inconsistently applied. Furthermore, DfD is perceived as realistic when it is integrated early. Interviewees highlighted modular design and flexible cabling as already feasible steps. Client demand emerged as a decisive enabler, reinforcing that barriers are structural rather than conceptual, with practice lagging behind awareness.

Key barriers hindering the adoption of sustainable and circular practices include the lack of operational tools for reuse and testing; weak organisation and coordination within both the horizontal and vertical dimensions of the design and supply chain—limited early involvement of sustainability consultants (horizontally) and installers (vertically); and finally market-driven decision-making, characterised by weak client incentives.

5.2. Digital Tools, Standards, and Certification for Circularity in EEI

Regarding RQ2 (“How do digital tools, technical standards, and certification frameworks enable or constrain the implementation of circularity in EEI practices?”), two themes are central here: (i) a translation gap between high-level standards and day-to-day practice, and (ii) a divergence between the potential and the actual use of digital tools.

The survey highlighted uneven awareness of standards—some were well-known, others rarely used—illustrating a persistent translation gap between the ambition of sustainability/CE frameworks and their practical usability in EEI projects. In practice, many schemes mirror the priorities of the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (EPBD) and the Energy Efficiency Directive (EED), prioritising operational energy while giving little explicit attention to circularity-oriented standards such as ISO 20887 (DfD) or IEC/TR 62635 (end-of-life, recyclability). Comparative reviews confirm that although GBRSs address energy, automation, and waste management, aspects such as adaptability, reuse, or modular EEI remain underrepresented.

Certification systems show a similar misalignment. Although most professionals had experience with GBRS (e.g., BREEAM, LEED, DGNB), few reported regularly checking EEI compliance with certification requirements. Only a small subset systematically used them, and their application remained occasional rather than systematic. This low uptake reflects a broader tendency for GBRSs to prioritise operational energy, lighting efficiency, and occupant comfort [20,54].

Tools such as BIM, LCA software, material databases, and digital building logbooks are positioned as a potential bridge and promoted as enablers of traceability, disassembly planning, and lifecycle assessment [55]. Interviewees described digitalisation as the “tool of the future,” yet current platforms are not adapted to EEI-specific challenges. National tools such as TOTEM and GRO, while widely known, do not include EEI-specific modules. Likewise, ISO 20887 still needs to be practically applied to technical tools.

Digitalisation and certification frameworks are seen as promising enablers. However, inconsistencies in assessment methodologies, scarcity of EEI-specific sustainability data, including limited adoption of EPDs [37], and limited uptake of digital data structures (e.g., DPP fields for connectors, fixings, disassembly sequences) constrain the reliability and implementation of digitalised sustainable and circular practices. Their role, therefore, remains peripheral, highlighting the need for EEI-specific adaptation.

5.3. Professional Roles and Collaboration in EEI Circularity

Regarding RQ3 (“How do professional roles, collaboration dynamics, and emerging models influence decision-making on circular and futureproof EEI?”), three themes stand out: imbalanced stakeholder involvement, timing of participation, and lack of drivers for decision-making about sustainable and circular EEI.

The survey and interviews suggest that collaboration dynamics—particularly, who is involved, when, and under which conditions—can shape whether circular strategies for EEIs are considered in practice.

First, survey results confirmed that clients and engineers dominate decision-making across project phases, being consistently involved across project phases, while installers and sustainability experts often play only a marginal role. This imbalance is significant because circularity depends on distributed knowledge, yet those with practical expertise in disassembly and maintainability remain sidelined. Interviews highlighted both missed opportunities and the benefits of early collaboration, such as in one project where suppliers and installers co-developed a prefabricated, demountable energy box—a modular hub for electrical distribution that can be installed as a single unit and later removed or upgraded—supporting adaptability over time.

Such cases echo Durmisevic’s call to embed design for disassembly from the outset [56], and align with wider evidence from Ho et al. suggesting that organisational resistance, limited knowledge, and hesitant suppliers continue to slow down the transition to circular models [57].

Second, the timing of involvement emerged as decisive. Installers were frequently brought in only at execution, limiting opportunities to integrate circular solutions at the design stage. Sustainability experts were typically engaged late and mainly in advisory roles, restricting their ability to influence choices such as selecting reusable components or integrating EEI for disassembly and future upgrades. This late involvement also reinforces findings from RQ2, where certification frameworks and digital tools underrepresent EEI, contributing to the marginalisation of technical systems.

Finally, regulatory compliance and client preferences emerged as the most influential factors, alongside cost competitiveness of reused products and perceived environmental benefits. On the other hand, lack of policy and market incentives, insufficient code requirements, and limited contractor expertise were identified as the most decisive obstacles, demotivating clients who often drive the decision-making process. This suggests that not only the timing but also the risk perception, together with liability gaps, reinforce conventional rather than circular solutions.

Interviews further indicated that, in the absence of certification or clear liability frameworks, contractors and design teams adopted risk-averse positions, which discourages them from supporting reuse. This dynamic reflects broader findings that missing certification schemes and unclear liability remain key obstacles to reuse in construction [53].

5.4. Practical Recommendations

Building on the study’s findings, the following recommendations translate empirical insights into targeted actions for professionals, policymakers, and clients. Together, these results show that sustainable and circular EEI is not constrained by technology itself but by the availability of practical instruments for their design, and by how projects are organised and incentivised. Each recommendation directly addresses barriers identified in RQ1–RQ3 and translates them into actionable steps:

To encourage professionals to adopt sustainable and circular practices for EEI design, existing technical standards, EEI-specific data, and related knowledge should be disseminated more effectively. Wherever possible, these should be translated into practical design guidelines and tools. Strategies addressing all lifecycle stages of EEI should be considered; however, particular attention should be given to underutilised strategies related to the production and end-of-life stages of EEI, such as adaptability, modularity, and reuse.

To enable professionals to assess the sustainability and circularity performance of their EEI, existing evaluation methods should be tailored to EEI and simplified into practical tools suitable for professional use. For example, this could be achieved by integrating EEI-specific criteria into existing assessment frameworks, such as GBRS or local tools like TOTEM and GRO. This could ultimately promote the integration of EEI sustainability and circularity aspects in the early-stage design and procurement processes.

To strengthen the use of digital tools for EEI, BIM-based building logbooks should be expanded to systematically include EEI components, supported by reliable manufacturer data and product-level EPDs. Furthermore, the development of DPPs for the EEI component could also support and enhance the adoption of circular strategies, such as DfD and reuse, which are currently seldom implemented.

To enhance the circularity of EEI design, stakeholders such as installers and sustainability experts should be involved earlier in projects, ideally from their design stage, so that disassemblability and maintainability are embedded from the outset. Effective coordination among stakeholders, both horizontally and vertically within the supply chain, is essential to achieve this.

As clients play a crucial role in driving decision-making on EEI circularity, mainly due to the absence of stringent regulations in the field, they should be incentivized through targeted policies, subsidies, and public procurement criteria. In addition, adoption could be encouraged through showcasing pilot projects, introducing simple “circular readiness” labels, and promoting EEI as a future-proof investment.

Building on the above recommendations, procurement could move beyond traditional lowest-cost tendering by adopting design-and-build or integrated project delivery approaches that encourage collaboration. Public procurement could further drive circular EEI by embedding adaptability, modularity, and reuse directly into tender criteria. Collectively, these measures could operationalize circular principles in everyday EEI practice, bridging the current gap between awareness, policy intent, and implementation.

5.5. Limitations and Future Research

A few limitations of the study should be noted. First, the findings are based on a geographically limited sample, shaped by the specific objectives of the E-construct project, within which this study has been conducted, which focused on the Flemish construction sector in Belgium. Second, although the survey and interview participants represent a variety of stakeholders involved in EEI design, the sample size remains limited. Therefore, the results should be interpreted as exploratory in nature rather than fully representative. Nevertheless, this study provides valuable early insights that can inform future large-scale and cross-national investigations into circular practices in EEI.

Future research should expand both the breadth and depth of analysis, including developing additional surveys on a larger sample of professionals inside and outside the Flemish region of Belgium. Extending the geographical boundaries of the survey would allow cross-country validation of the current findings. Comparative EU studies could clarify how national frameworks enable or hinder EEI integration. Methodological work could address ways to incorporate EEI more systematically into certification schemes and digital infrastructures; for example, developing EEI-specific certification criteria and methods, testing protocols, and piloting procurement models with earlier installer involvement. This could finally support professionals through practical tools and regulatory guidance that facilitate the implementation of circularity in EEI. Ultimately, advancing this agenda requires moving from exploratory insights toward semi-quantitative approaches and modelling of adoption drivers and barriers. Such work would provide robust frameworks that translate EEI circularity and sustainability into practice.

6. Conclusions

This study aimed to identify and analyse knowledge gaps in EEI design and procurement, as well as the potential and barriers of practice-based approaches adopted by the professionals. By adopting a bottom-up research approach, the study has obtained insights from practitioners’ experiences to inform the development of future guidance documents and tools to support sustainable and circular EEI.

Academically, the research contributes to filling an underexplored gap in circular construction studies by positioning EEI as active, dynamic subsystems within buildings rather than passive technical components. It provides an initial empirical foundation for integrating lifecycle and circular-economy thinking into the design and procurement of EEI.

Theoretically, the study extends existing circular-economy and lifecycle thinking frameworks by demonstrating how systemic barriers—particularly regulatory, organisational, and market-related—constrain the translation of circular principles into technical design practice. It highlights the central role of collaboration dynamics and early stakeholder engagement in operationalising design-for-disassembly and reuse, thus connecting empirical findings to broader theories of socio-technical transition and design for adaptability. Building on these exploratory results, future work should formalise the identified relationships through semi-quantitative models that link professional, regulatory, and organisational factors influencing the adoption of circular practices in EEI.

The findings reveal that, despite recent EU efforts in establishing a policy and regulatory framework for sustainability and circularity of technical installations, including EEI in buildings, the practical implementation of these principles, especially circularity, in EEI design remains underdeveloped. Furthermore, existing regulatory and certification frameworks primarily focus on operational energy, while lifecycle aspects such as reuse, adaptability, and DfD are rarely operationalized. Advancing circularity in EEI, therefore, requires ensuring full lifecycle coverage by both regulatory and technical instruments and providing practitioners and clients with clear incentives and reliable tools for implementation.

Engaging professionals emerges as a valuable approach to gain practice-based insights and enhance the practical application of sustainable and circular EEI. In this way, this exploratory work not only offers practical recommendations to professionals but also a conceptual and empirical foundation for future academic studies.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su17219907/s1, S1: ‘Limesurvey questionnaire’, Supplementary, S2: ‘Interview questions’, S3: Statistical analyses and results (Tables S1 and S2).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S.S. and C.P.; methodology, A.S.S.; formal analysis, A.S.S.; investigation, A.S.S.; data curation, A.S.S.; writing—original draft preparation, A.S.S.; writing—review and editing, C.P.; visualization, A.S.S.; supervision, C.P.; funding acquisition, C.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Vlaams Agentschap Innoveren en Ondernemen (VLAIO), grant number HBC.2021.0911, under the E-construct project. The APC was funded by Vlaams Agentschap Innoveren en Ondernemen (VLAIO).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Social and Societal Ethics Committee (SMEC) of KU Leuven (protocol code G-2024-8388, 23 October 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the project partners for their input and the participating professionals for completing the survey and interviews.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BREEAM | Building Research Establishment Environmental Assessment Method |

| CE | Circular Economy |

| CRM | Critical Raw Materials |

| DfD | Design for Disassembly |

| DGNB | Deutsche Gesellschaft für Nachhaltiges Bauen (German Sustainable Building Council) |

| DPP | Digital Product Passport |

| EED | Energy Efficiency Directive |

| EEI | Electrical and Electronic Installations |

| EECONE | European ECOsystem for Circular Electronics |

| EPBD | Energy Performance of Buildings Directive |

| EPD | Environmental Product Declaration |

| ESPR | Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation |

| EU | European Union |

| GBRS | Green Building Rating Systems |

| GRO | Gebouwen Referentie Ontwerp (Flemish sustainable building framework) |

| HQE | Haute Qualité Environnementale (French sustainable building certification) |

| HVAC | Heating, Ventilation, and Air-Conditioning |

| IEC | International Electrotechnical Commission |

| ISO | International Organization for Standardization |

| LCA | Life Cycle Assessment |

| LCT | Life Cycle Thinking |

| LEED | Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design |

| PCR | Product Category Rules |

| PV | Photovoltaic |

| RoHS | Restriction of Hazardous Substances |

| TOTEM | Tool to Optimise the Total Environmental Impact of Materials |

| VLAIO | Vlaams Agentschap Innoveren en Ondernemen (Flemish Agency for Innovation and Entrepreneurship) |

| WEEE | Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment |

References

- Emissions Gap Report. 2019. Available online: https://www.unep.org/resources/emissions-gap-report-2019 (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- European Commission. The European Green Deal. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal_en (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- European Commission. Fit for 55: Delivering on the Proposals. 2021. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal/delivering-european-green-deal/fit-55-delivering-proposals_en (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- BUILD UP. Circular Construction and Materials for a Sustainable Building Sector. Available online: https://build-up.ec.europa.eu/en/resources-and-tools/articles/circular-construction-and-materials-sustainable-building-sector (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. In Towards a Circular Economy—A Zero Waste Programme for Europe; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2015; Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52015DC0614 (accessed on 6 October 2025).

- Energy Use in the Industry Sector Declines 5% in 2023—News Articles—Eurostat. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/en/web/products-eurostat-news/w/ddn-20250725-1 (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Ramon, D.; Allacker, K. Integrating long term temporal changes in the Belgian electricity mix in environmental attributional life cycle assessment of buildings. J. Clean Prod. 2021, 297, 126624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albu, H.; Beu, D.; Rus, T.; Moldovan, R.; Domniţa, F.; Vilčeková, S. Life cycle assessment of LED luminaire and impact on lighting installation—A case study. Alex. Eng. J. 2023, 80, 282–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazmi, R.; Chakraborty, M. Use of Coal Mining Wastes in the Construction Industry to Promote a Circular Economy: A systematic literature review. Circ. Econ. Sustain. 2025, 4, 3593–3622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. RoHS Directive—European Commission. 2021. Available online: https://environment.ec.europa.eu/topics/waste-and-recycling/rohs-directive_en (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- European Commission. Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment (WEEE) Directive 2012/19/EU; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2012; Available online: https://environment.ec.europa.eu/topics/waste-and-recycling/waste-electrical-and-electronic-equipment-weee_en (accessed on 27 February 2025).

- EECONE—Program. Available online: https://eecone.com/eecone/servlet/ocean12.IpList (accessed on 12 July 2025).

- EN 15804:2012+A1:2013; Sustainability of Construction Works—Environmental Product Declarations. iTeh, Inc.: Newark, DE, USA, 2013. Available online: https://standards.iteh.ai/catalog/standards/cen/a7de5991-2e9f-4e93-b34c-f1d794cbca02/en-15804-2012a1-2013 (accessed on 27 February 2025).

- EPD International. The PCR. Available online: https://www.environdec.com/pcr/the-pcr (accessed on 12 July 2025).

- EPD-Norge. Product Category Rules. 2022. Available online: https://www.epd-norge.no (accessed on 12 July 2025).

- Rochlitzer, D.; Lützkendorf, T. Management and communication of HVAC-specific life cycle-related information—Filling the gaps for sustainability assessment of buildings. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; Institute of Physics: Bristol, UK, 2022; Volume 1078, p. 012104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation. 2024. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/energy-climate-change-environment/standards-tools-and-labels/products-labelling-rules-and-requirements/ecodesign-sustainable-products-regulation_en (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- Public Waste Agency of Flanders (OVAM); Brussels Environment (Leefmilieu Brussel); Service Public de Wallonie (SPW). TOTEM—Tool to Optimise the Environmental Impact of Materials. Available online: https://www.totem-building.be/ (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- Public Waste Agency of Flanders (OVAM). GRO Tool. Available online: https://gro-tool.be/ (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- Marchi, L.; Antonini, E.; Politi, S. Green Building Rating Systems (GBRSs). Encyclopedia 2021, 1, 998–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berardi, U. Sustainability assessment in the construction sector: Rating systems and rated buildings. Sustain. Dev. 2012, 20, 411–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucon, O.; Ürge-Vorsatz, D.; Ahmed, A.Z.; Akbari, H.; Bertoldi, P.; Cabeza, L.F.; Eyre, N.; Gadgil, A.; Harvey, L.D.D.; Jiang, Y.; et al. Buildings. In Climate Change 2014: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Edenhofer, O., Pichs-Madruga, R., Sokona, Y., Farahani, E., Kadner, S., Seyboth, K., Adler, A., Baum, I., Brunner, S., Eickemeier, P., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 671–738. [Google Scholar]

- Ottosen, L.M.; Jensen, L.B.; Astrup, T.F.; McAloone, T.C.; Ryberg, M.; Thuesen, C.; Christiansen, S.; Pedersen, A.J.; Odgaard, M.H. Implementation stage for circular economy in the Danish building and construction sector. Detritus 2021, 16, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feijão, D.; Reis, C.; Marques, M.C. Comparative analysis of sustainable building certification processes. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 96, 108054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghisellini, P.; Cialani, C.; Ulgiati, S. A review on circular economy: The expected transition to a balanced interplay 1415 of environmental and economic systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 114, 11–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, T.; Jæger, B. Circularity for electric and electronic equipment (EEE): The Edge and Distributed Ledger (Edge&DL) model. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollard, J.; Osmani, M.; Grubnic, S.; Díaz, A.I.; Grobe, K.; Kaba, A.; Ünlüer, Ö.; Panchal, R. Implementing a circular economy business model canvas in the electrical and electronic manufacturing sector: A case study approach. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2023, 36, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durmisevic, E.; Brouwer, J. Design Aspects of Decomposable Building Structures; University of Twente: Enschede, NL, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 14025:2006; Environmental Labels and Declarations—Type III Environmental Declaration—Principles and Procedures. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/38131.html (accessed on 27 February 2025).

- ISO 20887:2020(en); Sustainability in Buildings and Civil Engineering Works—Design for Disassembly and Adaptability—Principles, Requirements and Guidance. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. Available online: https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/#iso:std:iso:20887:ed-1:v1:en (accessed on 27 February 2025).

- ISO 59020:2024; Circular Economy: Measuring and Assessing Circularity Performance. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/80650.html (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- European Commission. Level(s): A Common European Framework for Sustainable Buildings; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2025; Available online: https://environment.ec.europa.eu/topics/circular-economy/levels_en (accessed on 27 February 2025).

- Pechlivanis, C.; Rigogiannis, N.; Tichalas, A.; Kotarela, F.; Papanikolaou, N. Experimental study and techno-economic evaluation of an active fault detection kit in the prospect of future zero-energy building installations. Automatika 2024, 65, 1469–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hounkpatin, H.W.; Donnou, H.E.V.; Chegnimonhan, V.K.; Inoussa, L.; Kounouhewa, B.B. Techno-economic and environmental feasibility study of a hybrid photovoltaic electrification system in back-up mode: A case report. Int. J. Renew. Energy Dev. 2023, 12, 396–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevenster, A.; Stone, V.; Schratt, H. VinylPlus® and the VinylPlus product label: Could the industry label be integrated into independent sustainability certification schemes? IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 323, 012148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamnatou, C.; Chemisana, D.; Mateus, R.; Almeida, M.G.; Silva, S.M. Review and perspectives on life cycle analysis of solar technologies with emphasis on building-integrated solar thermal systems. Renew. Energy 2015, 75, 833–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dascalaki, E.G.; Argiropoulou, P.A.; Balaras, C.A.; Droutsa, K.G.; Kontoyiannidis, S. Benchmarks for embodied and operational energy assessment of Hellenic single-family houses. Energies 2020, 13, 4384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.S.; Azmi, N.F.; Baaki, T.K. Cost performance of building refurbishment works: The case of Malaysia. Int. J. Build. Pathol. Adapt. 2018, 36, 41–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horyński, M.B. ELMECO & AoS 2017: International Conference on Electromagnetic Devices and Processes in Environment Protection with Seminar Applications of Superconductors, Nałęczów (Lublin), Poland, 3–6 December 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; 166p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darko, A.; Chan, A.P.C.; Ameyaw, E.E.; He, B.J.; Olanipekun, A.O. Examining issues influencing green 1459 building technologies adoption: The United States green building experts’ perspectives. Energy Build. 2017, 144, 320–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejidike, C.C.; Mewomo, M.C.; Anugwo, I.C. Assessment of construction professionals’ awareness of the smart building concepts in the Nigerian construction industry. J. Eng. Des. Technol. 2024, 22, 1491–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adu Gyamfi, T.; Thwala, W.D.; Pim-Wusu, M.; Aigbavboa, C.O. Exploration of green building technologies and their benefit to the building industry: The perspective of architects. Afr. J. Appl. Res. 2025, 11, 689–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumondang, E.S.; Regina, Y.V.; Angela, Y.R.; Larasati, D. Analysis study of light shelves, light pipes, mirror ducts utilization and implementation in Indonesia. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing Ltd.: Bristol, UK, 2022; Volume 1007, p. 012011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods, 5th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lune, H.; Berg, B.L. Qualitative Research Methods for the Social Sciences; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gummesson, E. Qualitative Methods in Management Research, 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman, D. Qualitative Research: Issues of Theory, Method and Practice, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey, C.; Lee, B. The Real Life Guide to Accounting Research: A Behind-the-Scenes View of Using Qualitative Research Methods; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2004; 539p. [Google Scholar]

- Vlaams Energie- en Klimaatagentschap (VEKA). Ondernemingsplan Vlaams Energie- en Klimaatagentschap; VEKA: Brussels, Belgium, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 14020:2022; Environmental Statements and Programmes for Products: Principles and General Requirements. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/79479.html (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- European Commission. About the EU Ecolabel. Available online: https://environment.ec.europa.eu/topics/circular-economy/eu-ecolabel/about-eu-ecolabel_en (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- IEC/TR 62635:2012; Guidelines for End-of-Life Information Provided by Manufacturers and Recyclers, and for Recyclability Rate Calculation of Electrical and Electronic Equipment. International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC): Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. Available online: https://webstore.iec.ch/en/publication/7292 (accessed on 27 February 2025).

- Ghaffar, S.H.; Burman, M.; Braimah, N. Pathways to circular construction: An integrated management of construction and demolition waste for resource recovery. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 244, 118710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez Cordero, A.; Gómez Melgar, S.; Andújar Márquez, J.M. Green building rating systems and the new framework Level(s): A critical review of sustainability certification within Europe. Energies 2020, 13, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovačić, I.; Honić, M.; Srecković, M. Digital platform for circular economy in AEC industry. Eng. Proj. Organ. J. 2020, 9, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durmisevic, E. Transformable Building Structures: Design for Disassembly as a Way to Introduce Sustainable Engineering to Building Design & Construction. Ph.D. Thesis, Delft University of Technology, Delft, The Netherlands, 2006. Available online: https://repository.tudelft.nl/record/uuid:9d2406e5-0cce-4788-8ee0-c19cbf38ea9a (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- Ho, H.W.L.; Haaker, T.; Yishake, M. Barriers and opportunities when transitioning from linear to circular business models: Evidence from the construction and manufacturing sectors in the Netherlands. Circ. Econ. Sustain. 2025, 5, 1865–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]