Abstract

This study presents a detailed evaluation of the energy performance and design optimization of a novel four-stage indirect evaporative cooler (IEC) enhanced with a supplementary humidifier, examined under the summer design conditions of Riyadh. Although previous research has demonstrated the system’s high thermal effectiveness, its energy efficiency—expressed through the coefficient of performance (COP)—and the influence of key design parameters have not been thoroughly explored. To address this gap, we integrate a validated thermal model with a comprehensive energy consumption model to assess the COP of the system under varying operational and geometric conditions. Results show that the baseline design achieves a maximum COP of 14.3. Through parametric optimization of heat exchanger depth and air velocity, the maximum COP increases to 20.4—a 43% improvement, associated with a supply temperature of 13.2 °C and specific water consumption of 2.5 kg/kWh at a return ratio of 0.3. The optimal parameters—a heat exchanger depth of 1.5 m and a humid-path air velocity of 1 m/s—ensure both high efficiency and practical feasibility. Overall, the findings highlight the considerable potential of the optimized multistage IEC system as a highly energy-efficient and sustainable alternative to conventional vapor-compression cooling technologies, contributing to reduced energy consumption and enhanced environmental sustainability in hot and dry climates.

1. Introduction

Air conditioning (AC) has become a vital technology for maintaining thermal comfort in residential and commercial buildings, particularly in hot climates [1]. This is especially true in regions like the Middle East, where AC systems are essential for supplying fresh air and maintaining comfortable indoor conditions despite the extreme outdoor conditions [2]. The global demand for cooling, driven by rising temperatures due to climate change, urbanization, and demographic shifts, is surging as a modern necessity. Projections indicate a potential 300% rise in cooling demand by 2050 [3]. This rising demand has led to significant increases in energy consumption and environmental impact. Heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) systems now account for up to 60% of global electricity use [4] and 39% in commercial buildings in the U.S. [5]. For developing nations, AC-related energy use is expected to increase 4.3 times by 2050 [6]. This surge is further accelerated by rising incomes and temperatures, with near-universal AC adoption predicted in warm regions within the coming decades [7]. In the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), electricity consumption has grown at an annual rate of around 7% due to economic and population growth [8]. AC alone is responsible for 70–75% of residential electricity use in KSA during the summer months [8,9]. The Eastern Province, in particular, faces additional strain, with cooling accounting for 45–60% of household electricity consumption from May to October [10,11]. These trends highlight the urgent need for sustainable and energy-efficient cooling technologies integrated with advanced heat exchangers to reduce environmental impact and meet the escalating energy demands in hot-climate regions [12,13].

Conventional vapor compression refrigeration (VCR) systems, which currently dominate the global market, face significant challenges due to their substantial environmental impact and high energy consumption [14,15]. These systems are widely utilized, accounting for nearly 80% of the refrigeration industry worldwide [14] and are responsible for approximately 99% of the final energy consumption for cooling in the European market [15]. However, their widespread use contributes significantly to environmental degradation, including global warming, and increased greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions [14,16]. This environmental burden is further worsened by their high total equivalent warming impact (TEWI), a metric that accounts for both the indirect emissions from energy consumption and the direct emissions from refrigerant leakage [17]. Furthermore, the technology of the conventional chillers has advanced to its optimum level, with typical coefficient of performance (COP) values ranging from 2.60 to 7.07, depending on the refrigerant and operational conditions [18]. This limited efficiency, coupled with their reliance on chemical-based refrigerants, represents a significant limitation, especially considering VCR systems cover approximately 90% of the world’s air-conditioning market [19]. Such systems significantly impact peak electricity demand, often accounting for up to 80% of total electrical power consumption in commercial buildings, thereby contributing to critical peak load challenges [18]. Moreover, conventional cooling systems may require modification, such as the integration of a cascade system [20] or coupling with a solar energy source [21] to enhance their sustainability when operating in high ambient temperatures, such as those in Riyadh. These heightened electricity demands and environmental concerns necessitate the exploration and adoption of alternative, energy-efficient, and sustainable cooling solutions to supersede conventional vapor compression systems.

Evaporative cooling systems have emerged as a promising and energy-efficient alternative to conventional vapor compression cooling, offering significant environmental benefits [22,23,24]. This technology harnesses the latent heat of water evaporation for cooling, thereby reducing reliance on harmful refrigerants such as CFCs and HFCs [23]. Particularly in hot and arid climates, evaporative cooling demonstrates substantial energy savings and increased efficiency compared to traditional methods [24,25], leading to notable reductions in carbon emissions and energy costs [26]. Studies show that evaporative cooling achieves annual energy consumption of 190 MWh compared to 440 MWh for air cooling systems, representing a 56.8% reduction in energy use and a parallel 56.8% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions [27]. Various configurations exist, including direct, indirect, and combined systems, each tailored for different applications [24]. These systems are highly energy-efficient, with energy consumption ranging from 0.3 to 1.2 kW/ton of refrigeration. Direct and indirect evaporative cooling systems exhibit wet bulb effectiveness from 60% to 85% [28].

Evaporative coolers with multistage designs showcase superior cooling performance in some studies, while the COP varies with design complexity. It was reported that advanced hybrid and multistage designs can theoretically achieve COP values as high as 35 under ideal conditions, signifying a substantial cooling output relative to the minimal energy input [28]. Furthermore, integrated evaporative and passive cooling systems have demonstrated COP improvements of up to 68.66% at challenging outdoor conditions [29]. In another multistage arrangement study, Ahmad et al. [30] simulated the performance of a solar-driven desiccant-based cooling system integrated with a dew-point evaporative cooler (M-cycle) of 50 kW capacity using TRNSYS software. The system was applied to three subtropical zones with average ambient temperatures ranging from 30 °C to 33 °C. Their results showed that a maximum COP of 2.28 could be achieved. Kousar et al. [31] experimentally evaluated the performance of an M-cycle of 5.26 kW capacity integrated with a solar-assisted solid desiccant system. The cooler’s setup consisted of 25 dry and wet channels and was tested under subtropical climatic conditions, with outdoor temperatures ranging from 27 °C to 41 °C and absolute humidity between 10 and 19 g/kg. The results showed that a maximum thermal COP of 1.46 and an EER (energy efficiency ratio) of 13.3 (corresponding to an electrical COP of 3.9) were achieved when the M-cycle was applied to both the process air and regeneration air streams.

At the core of many advanced thermal management systems, including indirect evaporative coolers, are plate-fin heat exchangers. These components are critical for achieving high thermal performance due to their inherent advantages, including a high heat transfer coefficient, compact size, and versatility in accommodating various flow arrangements, such as cross-flow and counter-current flow [32]. Specifically, air-to-air fixed plate heat exchangers are instrumental in recovering sensible energy by transferring heat between different air streams, such as exhaust and incoming fresh air [33]. Their thermal effectiveness often evaluates their performance. Experimental studies have demonstrated that even specific cross-flow designs, such as those with trapezoidal fins, can achieve a calculated effectiveness of up to 0.98 under experimental conditions with mass flow rates ranging from 4.975 to 9.751 kg/s at hot inlet temperatures of 369 K, showcasing their high potential for heat recovery [34]. The design and optimization of these exchangers are therefore pivotal to enhancing the overall performance of the cooling systems in which they are integrated.

Despite their considerable advantages, evaporative cooling systems face specific operational considerations. Direct evaporative coolers (DECs), for instance, can introduce excessive humidity into the conditioned space, compromising thermal comfort and potentially damaging sensitive electronics, especially in humid climates [35]. Indirect evaporative coolers (IEC), while addressing the humidity addition issue by separating the supply air from the wetted surfaces, can present their own challenges, including complex manufacturing processes [35]. In a recent study, Elsheniti et al. [36] investigated the effect of increasing the number of stages in an innovative multistage IEC that separates the sensible and evaporative processes along the wet channel to simplify the heat exchanger design. Their findings indicated that the four-stage IEC provided the highest thermal performance under arid climatic conditions. The system achieved a maximum COP of 12.5 and a corresponding supply air temperature of approximately 20 °C, even though the operating and geometric parameters of the heat exchangers were not optimized.

In response to these identified limitations in the literature, the multistage IEC system adopted in this study is specifically designed to enhance cooling efficiency while mitigating concerns related to humidity control, thereby offering a robust and sustainable cooling solution. While most of the previous studies focused on the development of the IEC-type M-cycle, this study focused on a new arrangement of IEC that separates the sensible and evaporative processes along the wet channel to simplify the system design, as discussed in reference [36]. However, the current study further develops the newly proposed four-stage IEC system by adding a supplementary wetted pad to achieve a lower supply air temperature. Additionally, the operating and geometric parameters of the sensible heat exchangers are optimized through a detailed new model developed using EES software V11.986 in the current study, which predicts pressure drops and heat transfer coefficients based on the specifications of the plate-fin_s1200T heat exchanger—commonly applied in HVAC systems—using well-established empirical correlations.

Although the thermal performance of the four-stage system has been well-characterized [36], there is a critical knowledge gap regarding the system’s actual energy performance, i.e., its COP. This coefficient is governed by the trade-off between maximizing thermal transfer and minimizing the fan power required to overcome fluid dynamic losses (pressure drop). This trade-off is particularly sensitive to geometric and operational variables, an aspect that has not yet been systematically explored for this specific configuration. The absence of a systematic optimization study of the geometric and operational variables to maximize energy efficiency represents the primary research gap that this paper aims to fill. Therefore, this paper aims to bridge this gap by first developing and applying a comprehensive energy model that links the system’s thermal output to its electrical energy consumption. The study will be conducted under the summer design conditions of Riyadh, a hot and dry city in Saudi Arabia. Subsequently, it will analyze the profound impact of the return ratio (RR) on the system’s pressure drop, energy consumption, and overall COP. The study will then conduct a parametric study to identify the optimal geometric (heat exchanger depth) and operational (air velocity) variables that maximize the system’s COP. Finally, a single–objective optimization study will be performed to find out the optimized parameters and provide actionable, practical guidelines for designers and engineers on the multistage IEC system.

2. Methodology

2.1. System Description

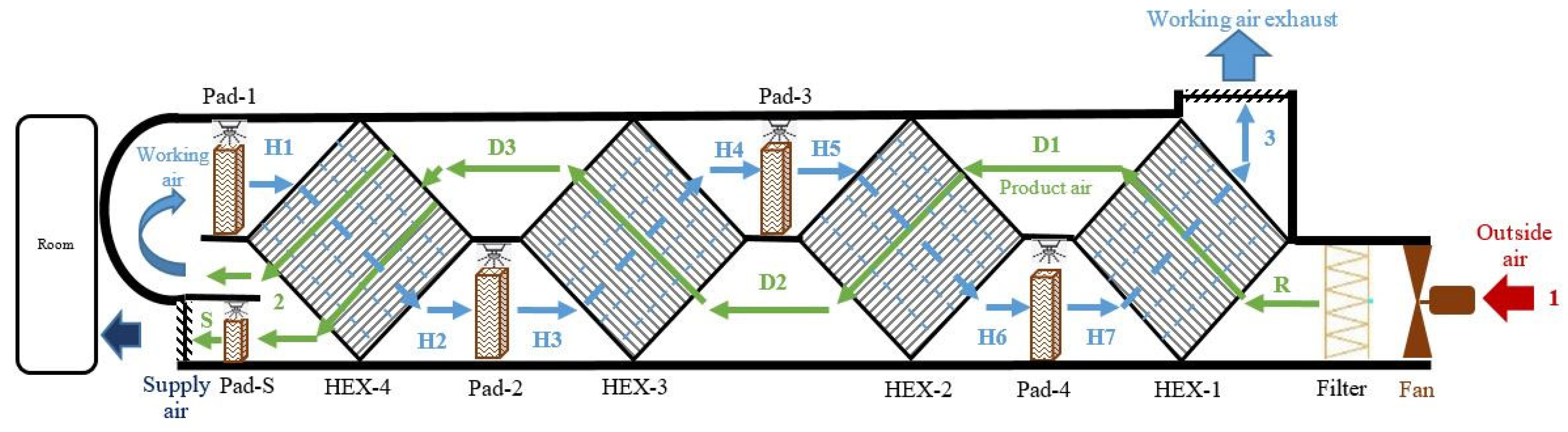

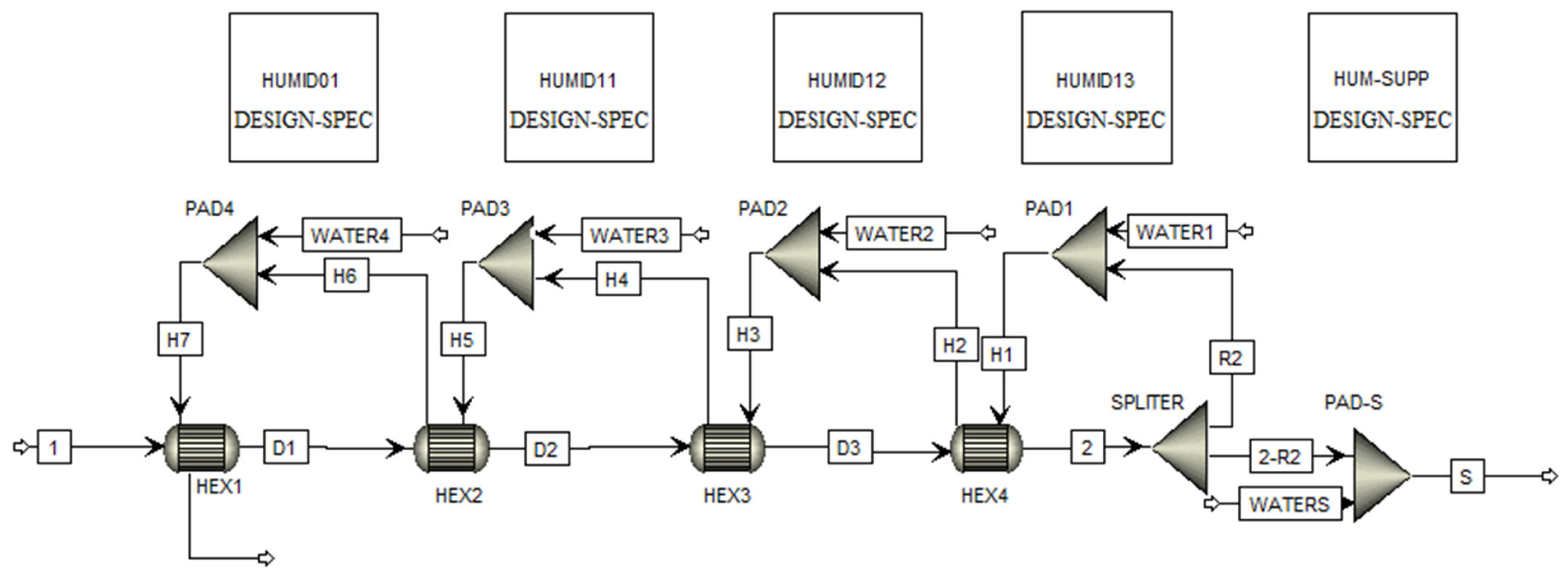

The IEC system configuration used in this study builds on the work of Elsheniti et al. [36], who reported that the four-stage indirect evaporative cooler with separate sensible heat exchangers and wet pads is the most effective design for achieving high thermal performance in arid climates. In the present study, this four-stage system is further modified by adding a supplementary wetted pad (Pad-S), as shown schematically in Figure 1, to further cool the supply air.

Figure 1.

Layout of the four-stage indirect evaporative cooling system with additional wet pad (Pad-S).

The system operates on a dual-path airflow mechanism, comprising both dry (D) and wet (H) paths, followed by a final direct humidification stage applied to the supply air before it is discharged. In the dry path, the incoming outside air () at point (R) first undergoes sensible cooling as it passes sequentially through four air-to-air heat exchangers (HX1 to HX4), exiting them at points (D1), (D2), (D3), and (2), respectively. Simultaneously, a portion of this dry air is diverted at point (2) to the wet path (the amount will be based on the return ratio (RR), where it serves as the secondary (working) air (). In the wet path, the working air passes through a series of inter-stage hydrophilic wetting pads (Pad-1 to Pad-4) and is considerably cooled via direct evaporation, exiting them at points (H1), (H3), (H5), and (H7), respectively. This cooled-humidified air then acts as the cooling medium on the secondary side of the heat exchangers before being exhausted at point (3). Finally, just before entering the conditioned space, the sensibly cooled supply air () at point (2) passes through a supplementary direct evaporative humidification stage (Pad-S). This new step further reduces its dry-bulb temperature while slightly increasing its humidity, thereby enhancing the overall cooling effectiveness.

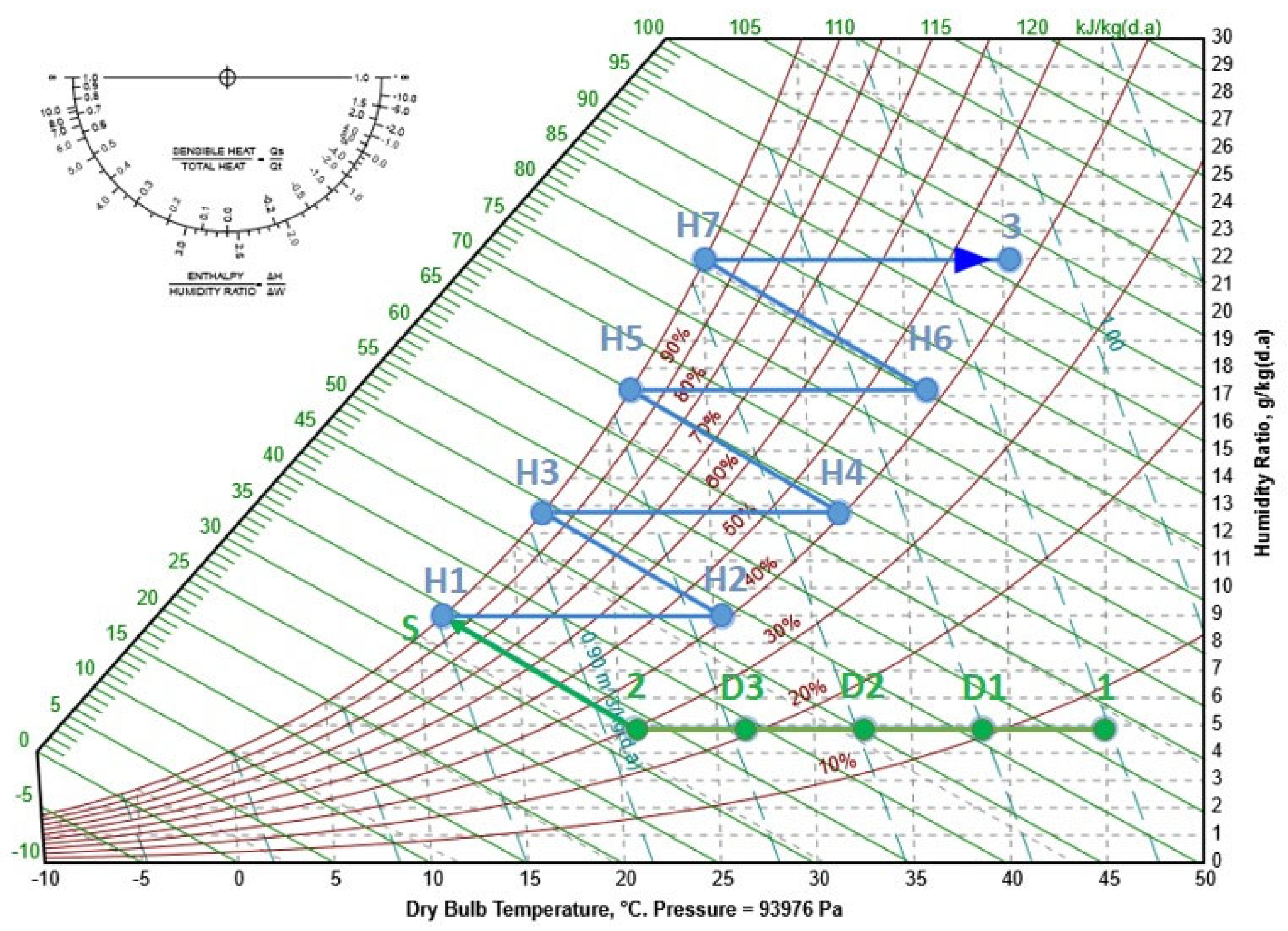

Figure 2 depicts the psychrometric processes of the modified four-stage IEC system. The chart shows the sensible cooling of the primary air through the heat exchangers (processes 1 to 2), followed by direct evaporative cooling in the supplementary pad (process 2 to S), achieving a lower supply temperature. The adiabatic evaporative cooling of the return secondary air (exemplified at RR = 0.4) in the wet path is also shown. The system’s successive stages in the wet path start with adiabatic evaporative cooling of the secondary air, which is then used to sensibly absorb the heat from the primary air in each stage.

Figure 2.

Psychrometric chart illustration of the IEC processes for the base case with a RR of 0.4.

2.2. Thermal Model

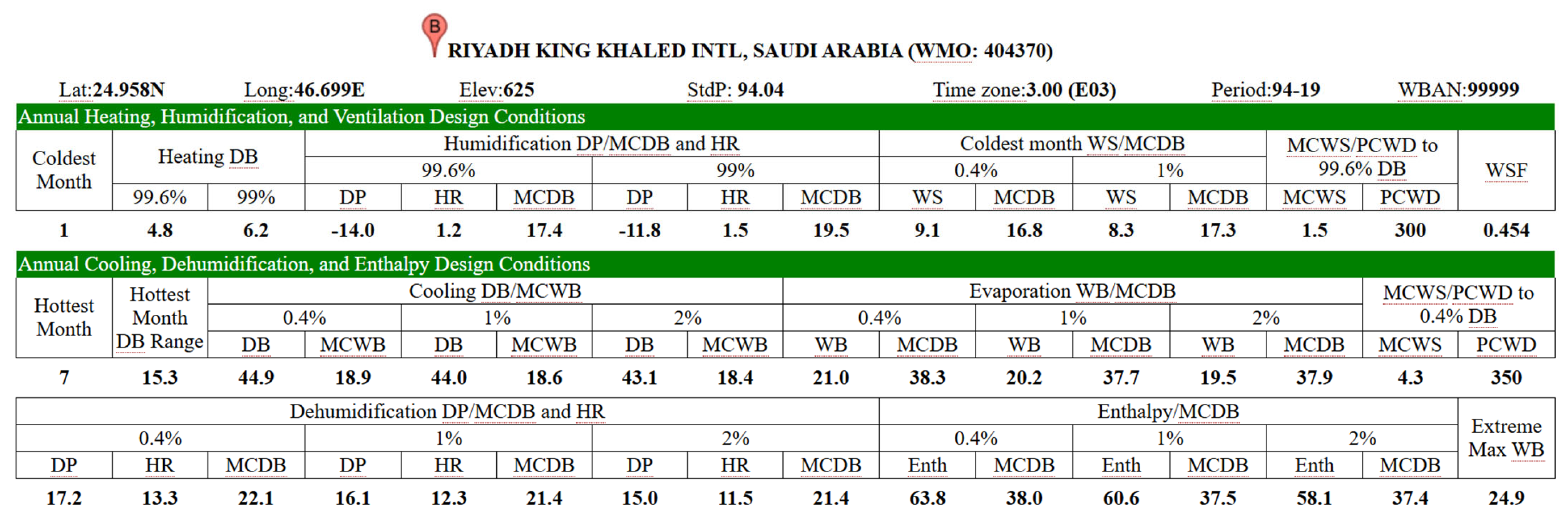

The comprehensive thermodynamic model for the four-stage IEC, developed and validated using ASPEN Plus software V11, is based on mass and energy balances and coupled with the properties of moist air. In this study, the layout of the ASPEN Plus flowsheet of the IEC system solved in the current study is shown in Figure A1. The thermal simulations were conducted under the outdoor design conditions for Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, shown in Figure A2 [37], which are summarized in Table 1. The model operates under steady-state conditions, with key assumptions including adiabatic heat exchangers with no surrounding heat loss and a constant dry air mass flow rate at the system inlet. The RR is the primary varying operational parameter.

Table 1.

Parameters and values used in the ASPEN Plus model based on the summer design condition of Riyadh.

Water consumption: The water consumed during the adiabatic humidification process, a critical parameter for sustainability in water-scarce regions, is calculated based on the change in humidity ratio of the working air in the wet path:

where is the mass flow rate of air in the working path, and and are the humidity ratios at the inlet and outlet of the humidifier, respectively.

Mass balances: Under steady-state conditions, mass conservation is maintained across all components. The air mass balance for any component is as follows:

The overall mass balance for the entire system, considering the dry air entering the dry channel () and the humid air in the wet channel (), is expressed as follows:

Return ratio (RR): The RR is a crucial operational parameter defined as the proportion of the humid air mass flow rate in the wet channel to the dry air mass flow rate in the dry channel:

The heat transfer capacity of each heat exchanger () represents the amount of thermal energy exchanged between the dry air and humid air streams. According to the energy balance, this value should be identical whether it is calculated from the dry air side or the humid air side:

On the other side, should be provided through the associated overall heat transfer coefficient (U) and the heat transfer area (A), considering the log mean temperature difference (ΔTLMTD) and the correction factor (F) as follows:

In this study, the (UA)i value for each heat exchanger is determined in detail to match its heat transfer duty under different conditions.

System effective cooling capacity (): This represents the actual cooling delivered to the conditioned space and is calculated based on the enthalpy change of the supply air stream from its inlet to the system’s supply outlet as follows:

Specific water consumption (SWC): This quantifies the water consumption efficiency of the system, relating the total water consumed to the effective cooling capacity provided:

Heat exchanger utilization factors (UFoverall): This factor assesses the proportion of useful effective cooling relative to the sum of the heat duties across all heat exchangers:

2.3. Heat Transfer and Power Consumption Model

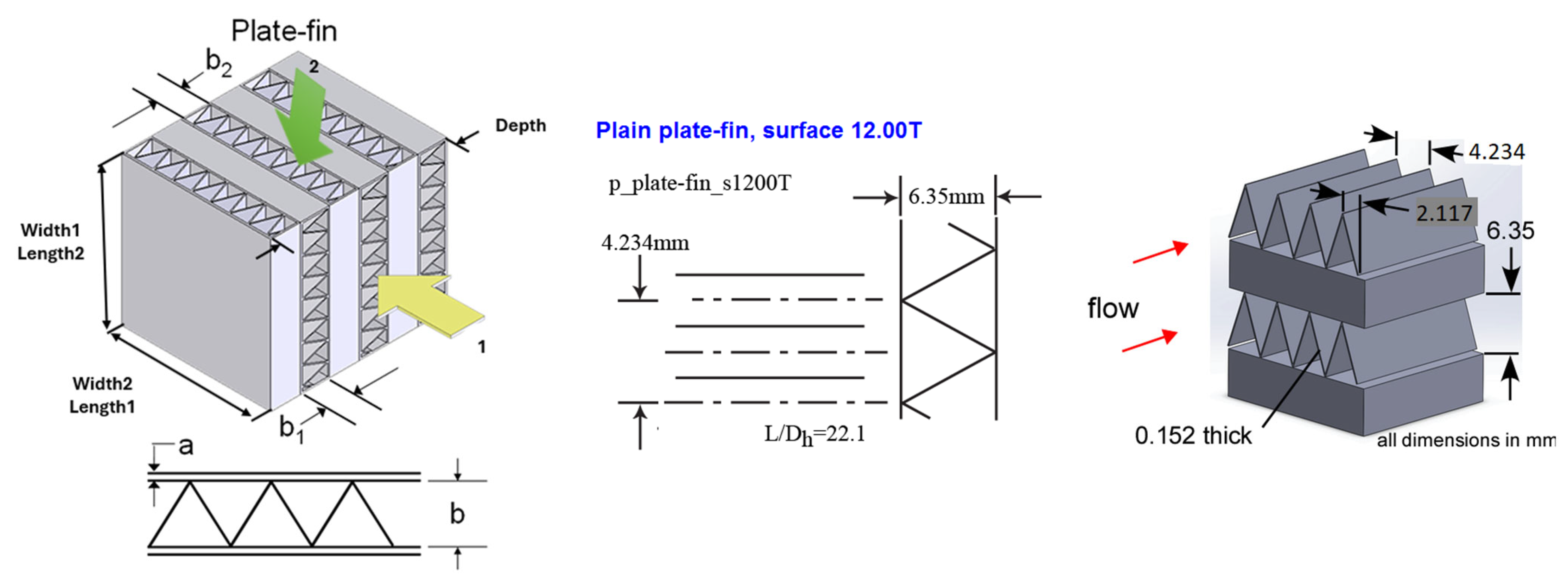

ASPEN Plus was used to simulate the system’s thermal performance, while the overall COP was evaluated using a model developed in Engineering Equation Solver (EES). EES was chosen because it offers practical built-in heat exchanger models and more accurate experimentally based fan power correlations. The actual system configuration, consisting of four separate heat exchangers, was preserved in this analysis, and the calculations were performed under the same design conditions used in the ASPEN simulation. To estimate pressure drops, the plate-fin_s1200T heat exchanger—commonly used in HVAC systems—was selected from the EES built-in database. The Type 12.00 T heat exchanger model in EES is based on correlations introduced in Kays and London [38]. The model’s parameters within EES specify the fin metal as nickel. The design specifications are presented in Figure 3, and the assumptions used in the EES base-case model are summarized in Table 2.

Figure 3.

Layout and geometric parameters of the plain plate-fin heat-exchanger type 12.00 T.

Table 2.

Parameters adapted for the base case in the power consumption model.

2.3.1. Governing Equations

The EES model for the plate-fin_s1200T surface is not based on first-principle differential equations but on well-established empirical correlations derived from the experimental data of Kays and London [38]. The governing equations consist of two primary empirical relationships and a set of standard supporting definitions.

Core empirical correlations:

The core of the model lies in two non-dimensional functions that correlate heat transfer and fluid friction performance to the flow conditions, represented by the Reynolds number (Re). These relationships are specific to the plate-fin_s1200T geometry and are stored as curve-fit data within the EES software.

Heat transfer correlation (Colburn j-factor):

where is the Colburn j-factor for heat transfer, and represents the unique empirical function of the Reynolds number for this surface.

Pressure drop correlation (fanning friction factor):

where f is the fanning friction factor, and represents the unique empirical function of the Reynolds number for this surface.

The internal EES procedure, namely Compact_HX_ND, is responsible for evaluating these functions to retrieve the values of and f for a given Reynolds number.

Supporting definitional equations:

The following standard equations are used to calculate the intermediate variables and the final desired outputs (heat transfer coefficients (h) and pressure drops (ΔP)) using the empirically determined factors from the above model.

- a-

- For heat transfer calculation:

Reynolds number (Re): This defines the flow regime and is calculated for fluid passing through the minimum cross-sectional area as follows:

where Dh is the hydraulic diameter ( for plate-fin_s1200T = 0.00287 m as provided by the EES built-in database), is the dynamic viscosity, and G is the product of the maximum mass velocity and the density of the fluid. G can be expressed as follows:

where is the mass flow rate, and is the ratio of the free-flow area to the frontal area (Afr).

Prandtl number (Pr): A fluid property relating momentum and thermal diffusivities.

where is specific heat at constant pressure, and k is the thermal conductivity of the fluid.

Stanton number (St): It is calculated from the Colburn j-factor.

Convective heat transfer coefficient (h):

- b-

- For pressure drop calculation:

Core pressure drop (ΔP): This is calculated using the fanning friction factor. This equation represents the frictional losses within the heat exchanger core only.

where L is the length of the heat exchanger in the flow direction, and is the mean fluid density.

2.3.2. Power Consumption Estimation

The system’s power consumption includes two main components:

a. Fan: Responsible for delivering air through the dry and humid channels of the heat exchangers and the filter.

b. Pump: Responsible for providing water to the saturation pads.

The power required to move air through all components of the IEC system was calculated as follows:

where represents the pressure drop across each separate component.

Pump selection:

Due to the relatively low water flow rate required in each saturation stage (less than 0.5 L/min), a compact submersible pump was selected to circulate the water during each saturation process. The chosen model (Hailea-HX8815, Hydro Bros, Croydon, UK) operates at 220–240 V and consumes approximately 20 W of power. It is capable of delivering a maximum head of 1.8 m and a maximum flow rate of 1400 L/h, making it well-suited for the low-demand application of this system.

COP calculation:

The total power consumption of the system was computed as follows:

The effective cooling capacity Qeff was obtained from ASPEN Plus simulations for each RR value based on the maximum heat duty.

The COP was then calculated using the following:

2.4. Model Verification

In this study, the thermodynamic model of the four-stage IEC developed in Aspen Plus was verified by checking the energy and mass balances across all model components. Detailed mass and energy balance calculations for similar flowsheets can be found in reference [36]. The model constructed in EES is based on the well-established correlations provided by Kays and London [38]. Furthermore, the processes represented on the psychrometric charts, as shown in Figure 2, demonstrate acceptable heat transfer effectiveness in the heat exchangers at all stages, confirming consistency between the dry and humid air paths.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Impact of Return Ratio on Thermal Performance and Water Consumption

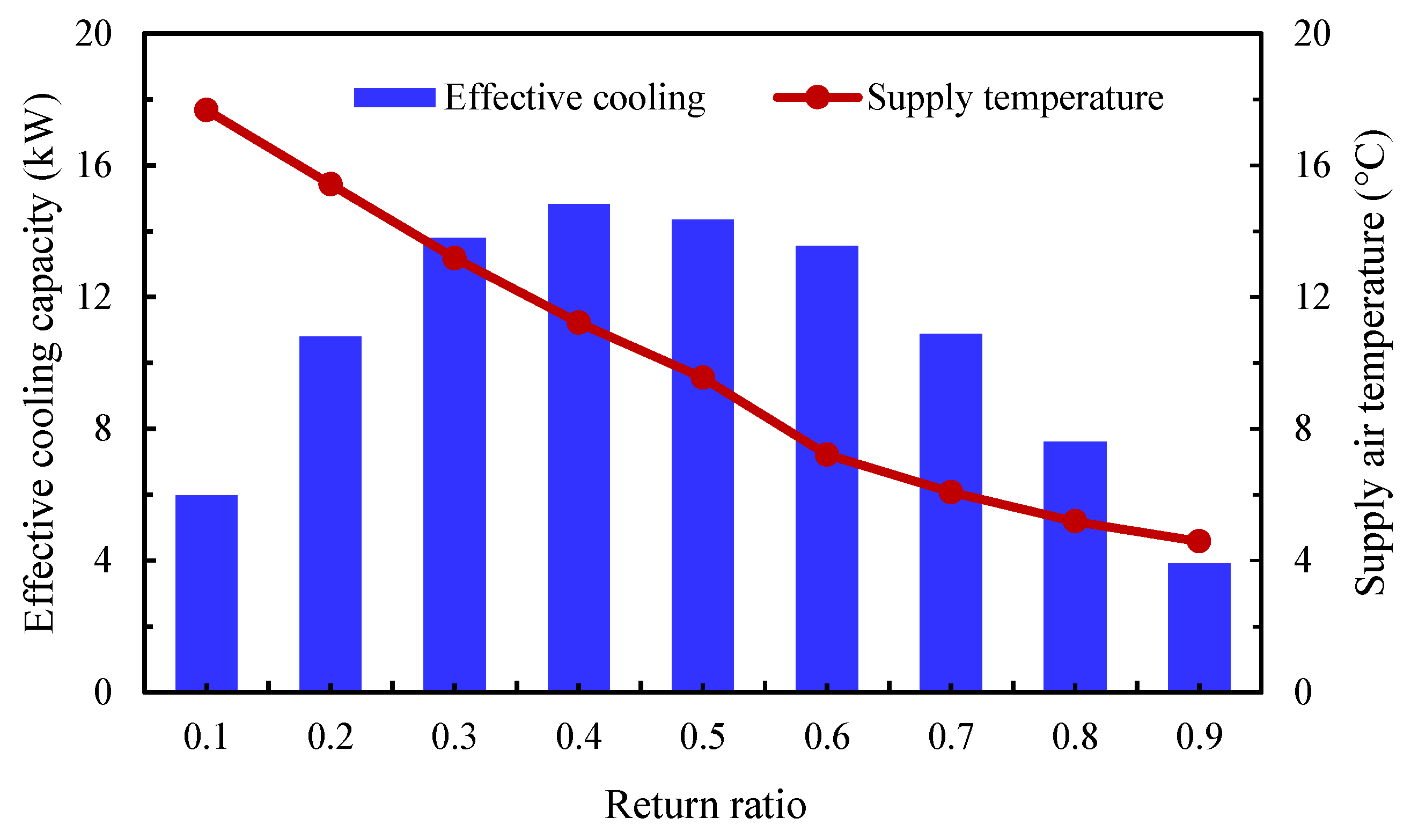

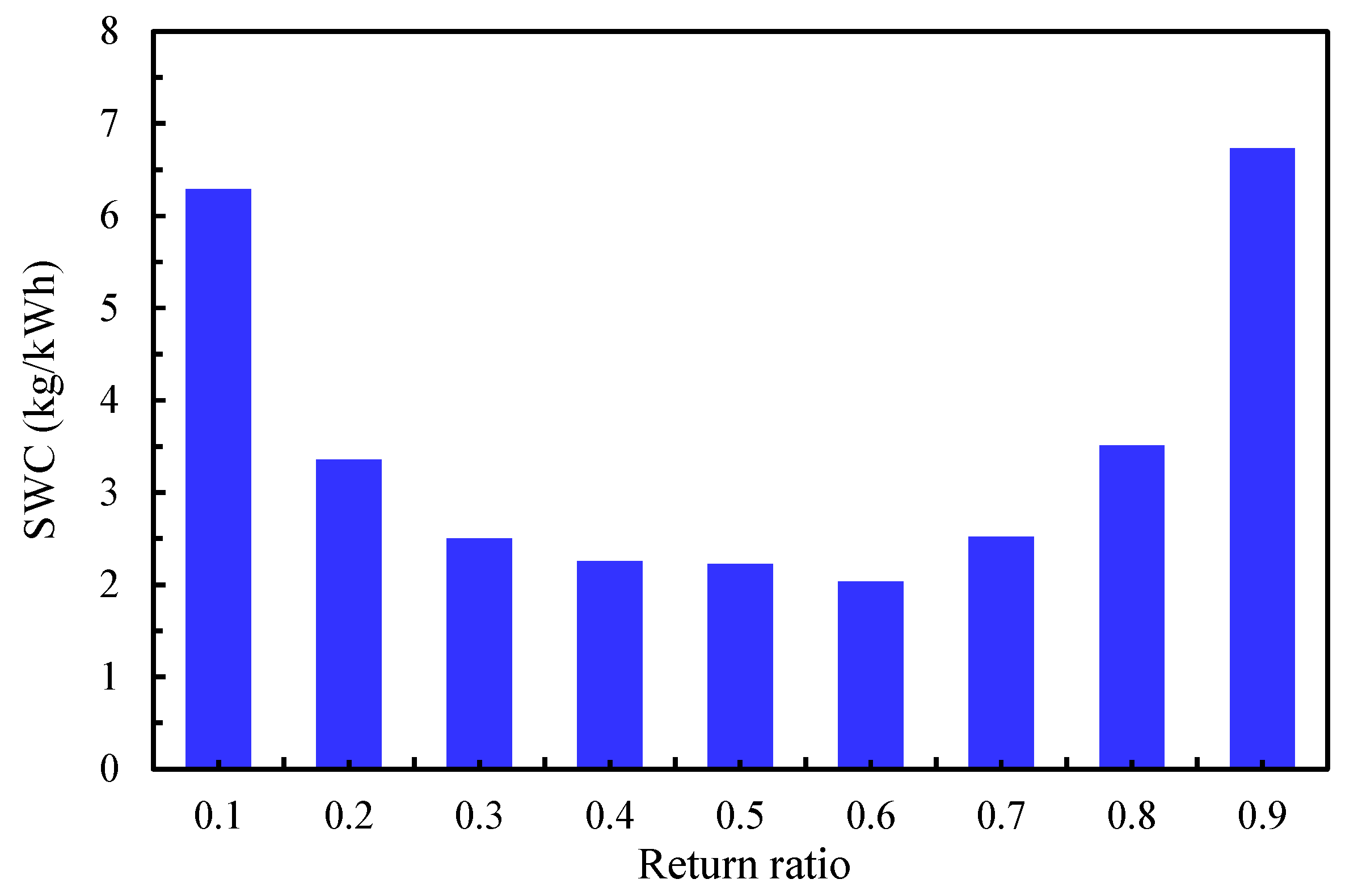

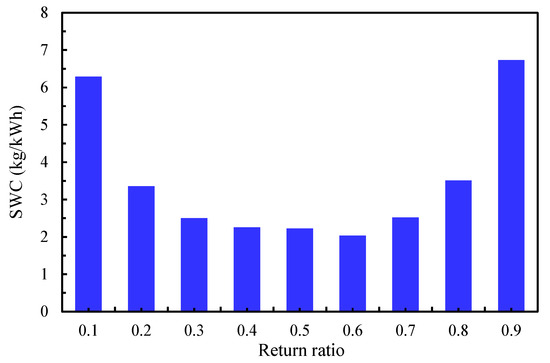

The present study evaluates the performance of the four-stage IEC configuration under the outdoor design conditions of Riyadh, providing a detailed assessment of the system’s behavior in a hot, arid climate. As illustrated in Figure 4, increasing the return ratio (RR) consistently lowers the supply air temperature; meanwhile, the effective cooling capacity (Qeff) delivered to the space reaches a distinct maximum before declining. For example, raising RR from 0.1 to 0.9 decreases the supply air temperature from 17.7 °C to 4.6 °C. Despite this, Qeff reaches its peak of 14.82 kW at RR = 0.4, then drops to 3.92 kW at RR = 0.9. This trend occurs because Qeff depends on the product of two competing effects: the supply air mass flow rate, which decreases as RR increases, and the temperature drop, which increases with RR. Their interaction produces a maximum effective cooling capacity at RR = 0.4. At the same time, the specific water consumption (SWC) follows a U-shaped profile as shown in Figure 5, with low water demand between RR = 0.4 and 0.6. return ratios.

Figure 4.

Variation of effective cooling capacity and supply air temperature across different return ratios.

Figure 5.

Influence of the return ratio on specific water consumption.

The most significant finding is the identification of an optimal operating window, where RR ranges from 0.3 to 0.7. Within this range, the system not only achieves its peak effective cooling capacity (as discussed earlier) but also its highest water efficiency, reflected by the minimum SWC. Outside this range, both cooling performance and water consumption suffer, underscoring the importance of operating within this “sweet spot” to balance cooling output and water conservation.

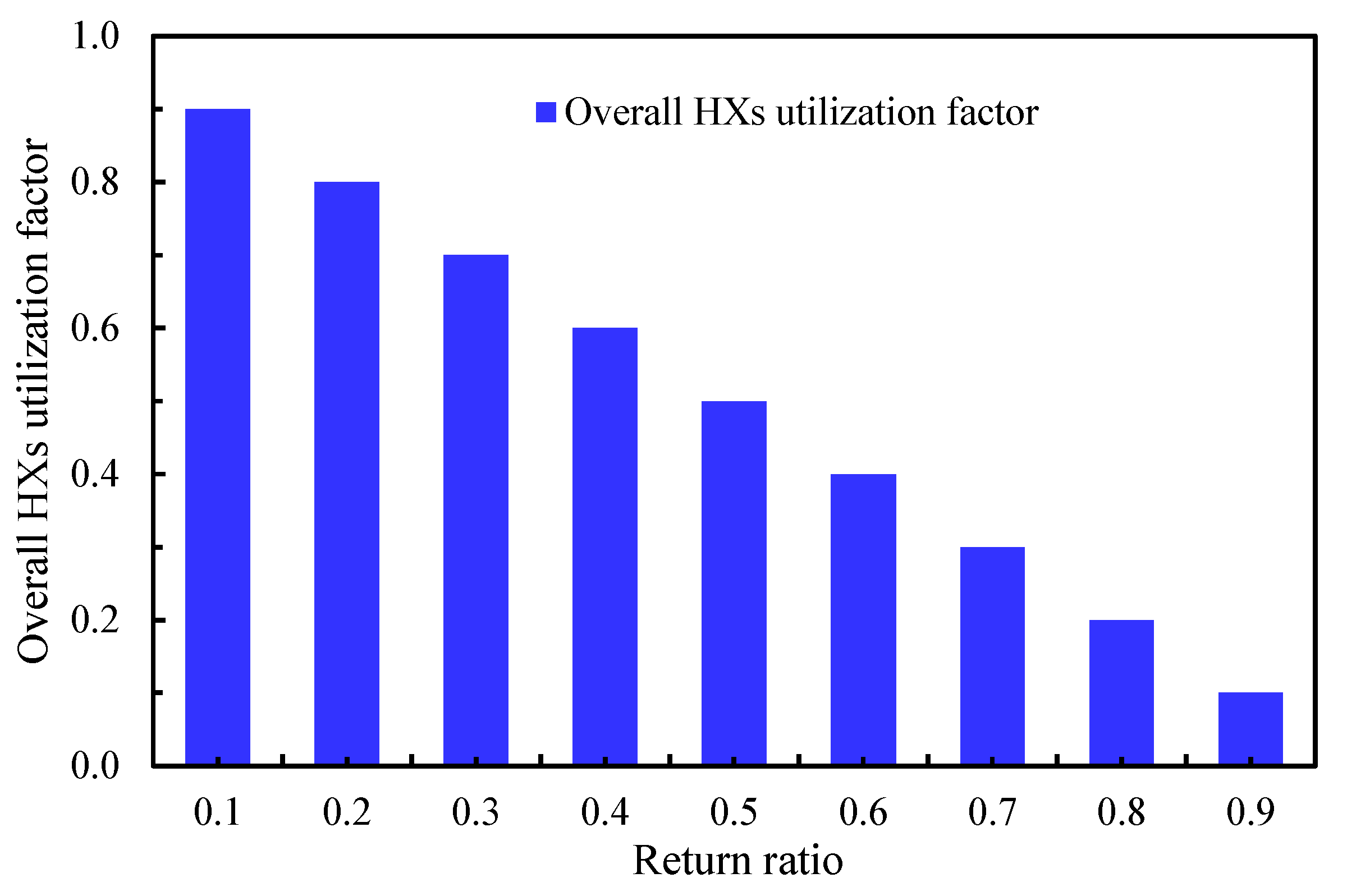

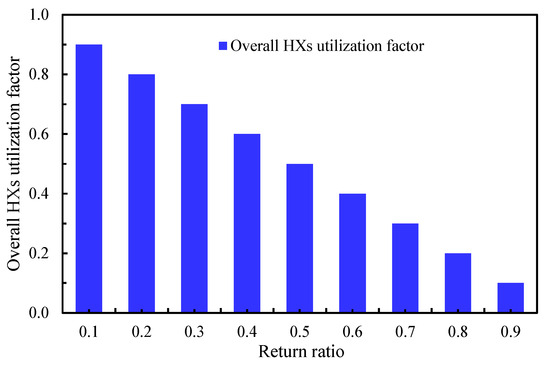

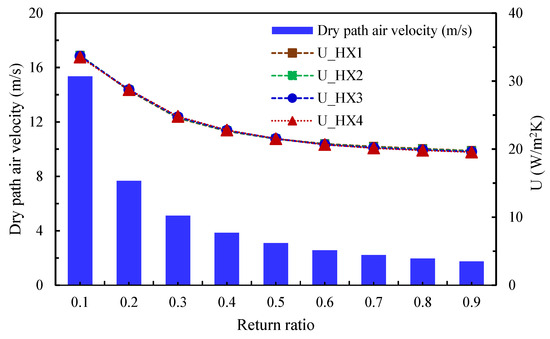

3.2. Impact of the Return Ratio on the Size of the Heat Exchangers

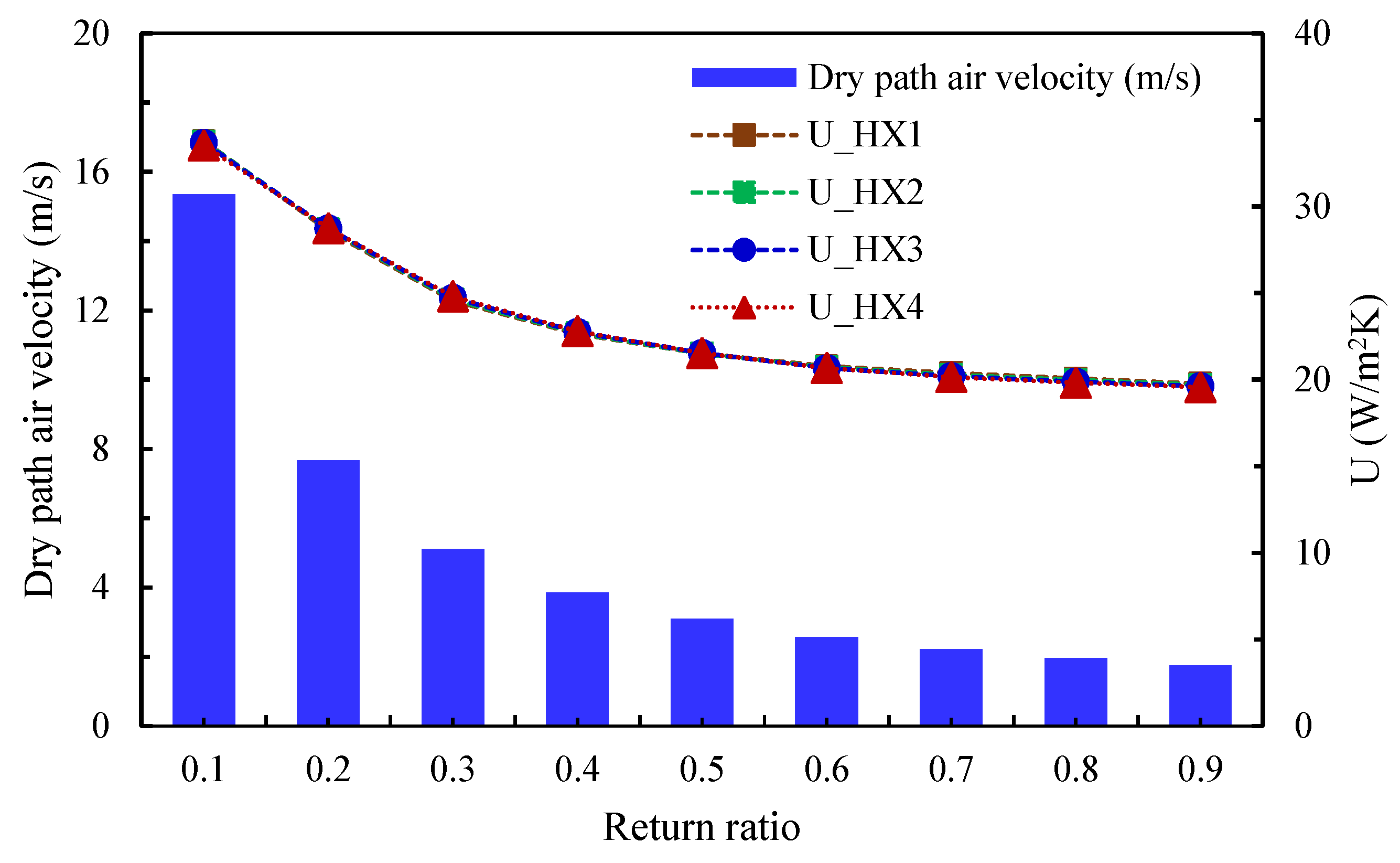

Figure 6 highlights the trend of the overall HX utilization factor, which decreases as the RR increases, driven by the reduction in supply air flow. Increasing the RR raises the proportion of secondary air, which serves as the cooling medium. It enables the use of heat exchangers (HXs) with higher heat transfer duties, as reported by Elsheniti et al. [36]. In the base case model of the current study, the air velocity in the humid path is fixed at 3 m/s, while the dry path velocity varies with RR to meet the required overall heat transfer coefficient, as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 6.

Influence of the return ratio on the HX utilization factor.

Figure 7.

The variation in the dry path air velocity and overall heat transfer coefficient with different RRs.

At a low RR of 0.1, the dry air velocity reaches a very high value of 15.36 m/s, corresponding to the highest overall heat transfer coefficient of about 33.53 W/m2·K across all HXs. By contrast, for RRs between 0.3 and 0.7, the dry air velocity ranges from 5.12 to 2.23 m/s—values that are practical and acceptable for air heat exchanger applications.

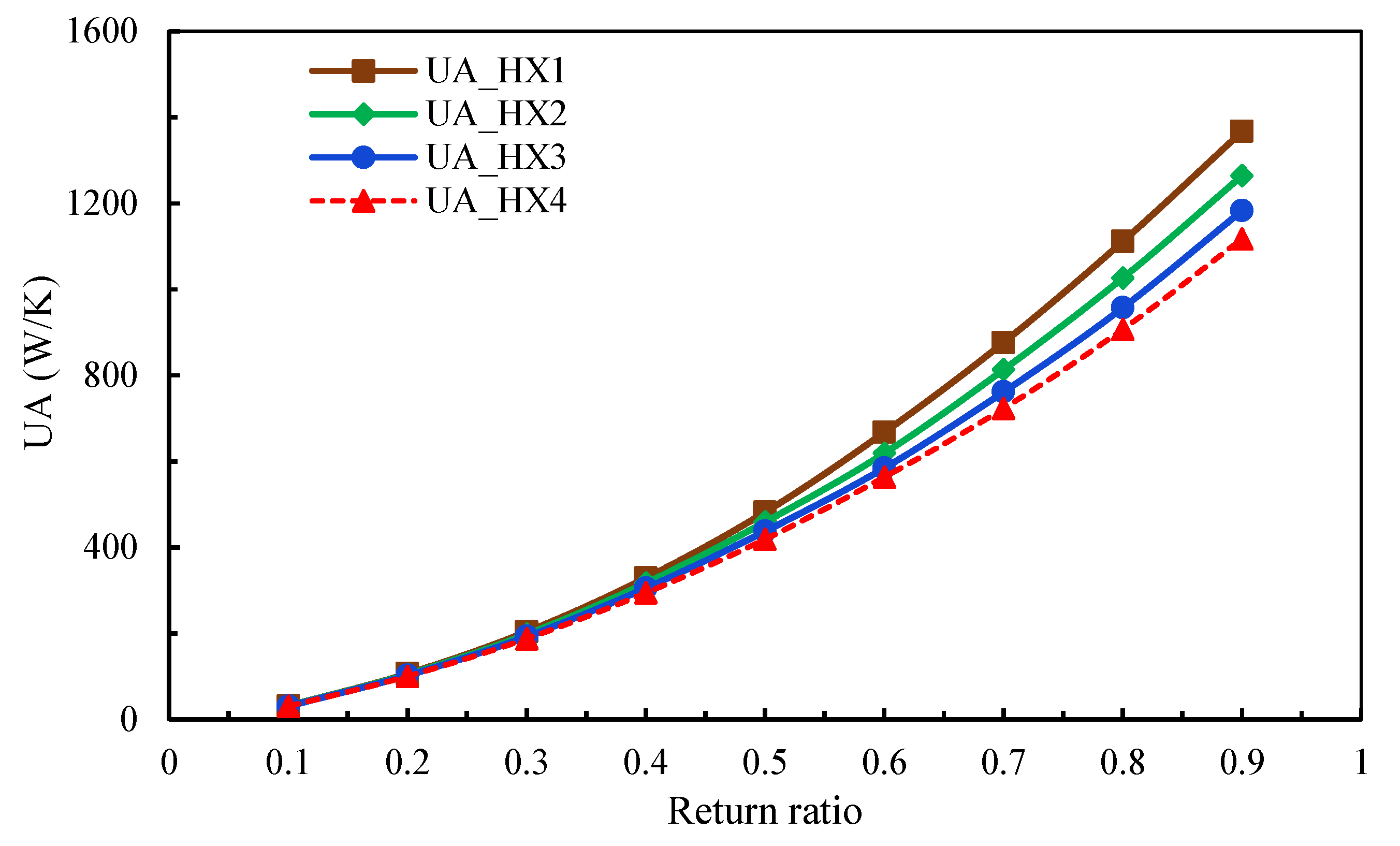

Figure 8 shows that the UA values of all heat exchangers (HXs) rise noticeably with increasing RR, with HX1 reaching the highest value of 1367 W/K at an RR of 0.9. At low return ratios, the UA values of all HEs are nearly identical, but they gradually diverge as RR increases, with HX1 consistently exhibiting the highest heat transfer conductance. This trend occurs because a higher RR increases the flow of the cooling wet medium, which substantially expands the effective heat transfer area (A). In particular, more air is directed through the wet path channels, which allows for a larger surface area for thermal exchange. As a result, higher return ratios significantly lower the dry air temperature and improve both the wet-bulb and dry-bulb effectiveness of the IEC.

Figure 8.

The effect of the return ratio on the overall heat transfer conductance (UA).

The relation between the operational parameter, which is the RR, and the physical size of the system is shown in Table 3. The required HX volume increases dramatically with higher RRs. For instance, the volume of the first heat exchanger (HX1) rises from 0.0017 m3 at RR = 0.1 to 0.1243 m3 at RR = 0.9—an increase of more than 70-fold.

Table 3.

The volume of each heat exchanger at different return ratios.

The geometric sizing analysis reveals that RR is not simply an operational parameter, but a vital design decision with significant implications for capital cost, system size, and weight. Operating at high RRs to minimize supply temperatures results in a dual penalty: higher operational costs (due to reduced COP, as will be discussed) and significantly higher capital costs (from the much larger HX volumes required). These findings reinforce that designing and operating the system near the peak COP point will be the most balanced approach, offering optimal energy efficiency while also minimizing equipment volume, cost, and installation challenges.

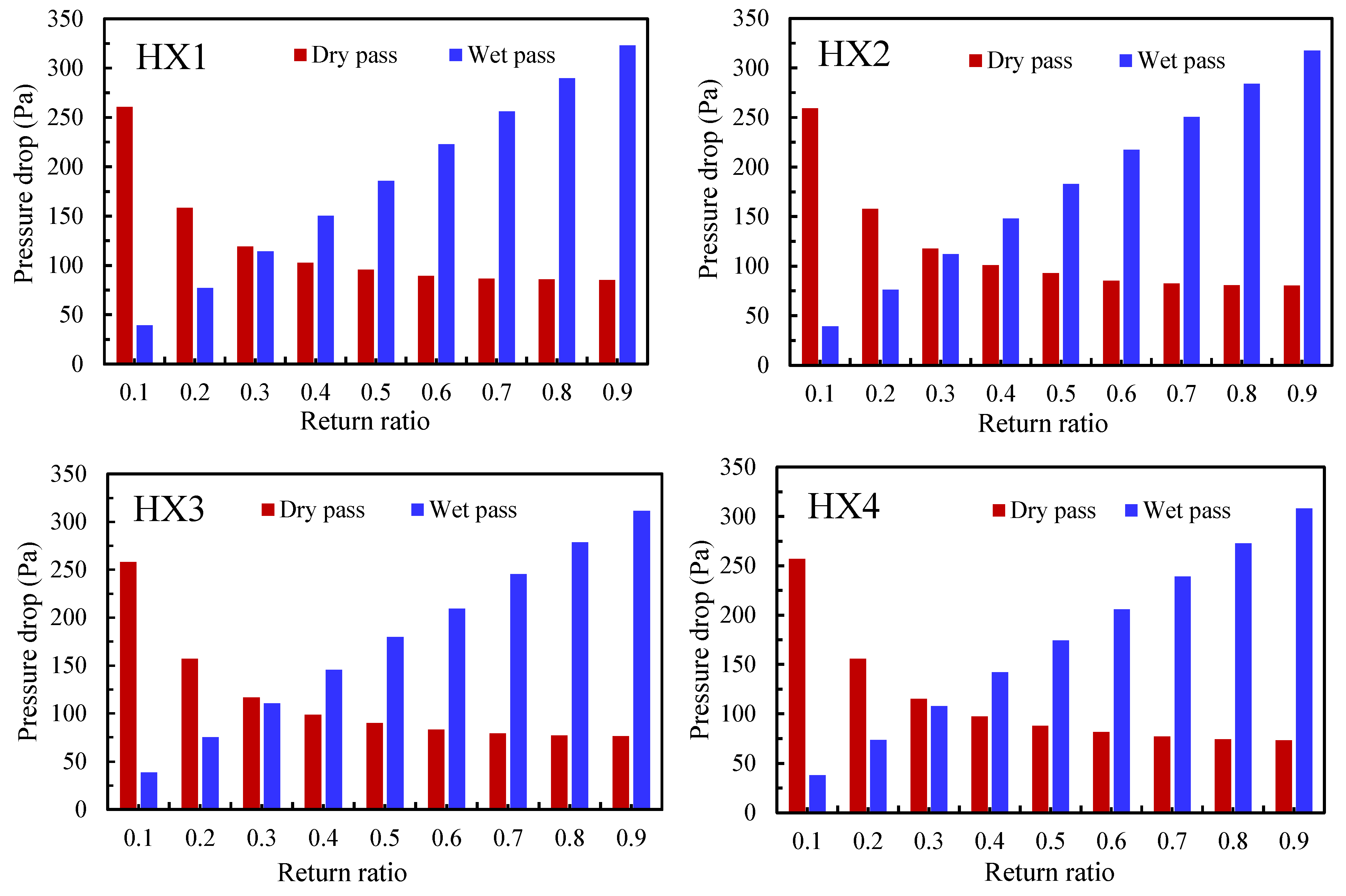

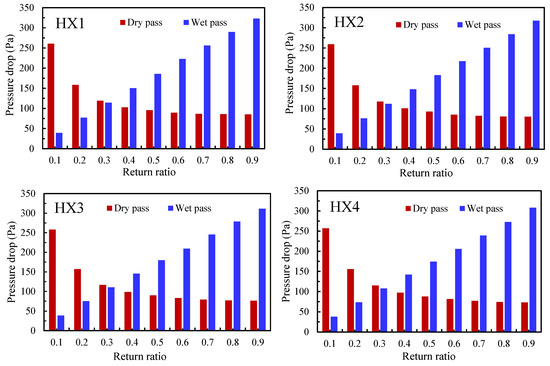

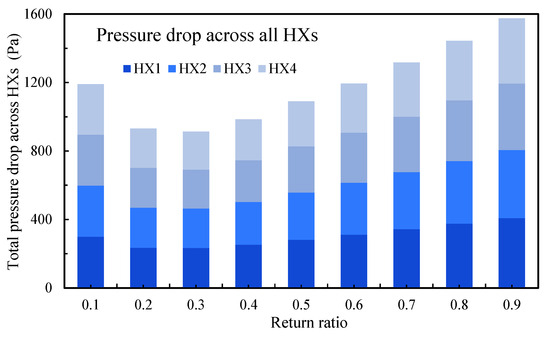

3.3. Impact of the Return Ratio on the Power Consumption

Figure 9 presents the air pressure drops across both sides of the heat exchangers (HXs): the dry and wet paths. All HXs exhibit a similar trend in pressure drop variation. In the dry path, where the mass flow rate remains constant, changes in dry air velocity drive the decreases in pressure drop with higher RRs. As shown in Table 3, the size of the heat exchanger is smaller at low RR, leading to higher velocity as shown in Figure 7. In contrast, in the wet path, the humid air velocity is fixed in the base case model, but the increased surface area at higher RRs leads to greater pressure drops. The maximum pressure drop of 323 Pa occurs in HX1 at an RR of 0.9 in the wet path, while the minimum is also observed in the wet path at an RR of 0.1.

Figure 9.

Pressure drop across individual heat exchangers at different return ratios for dry and wet paths.

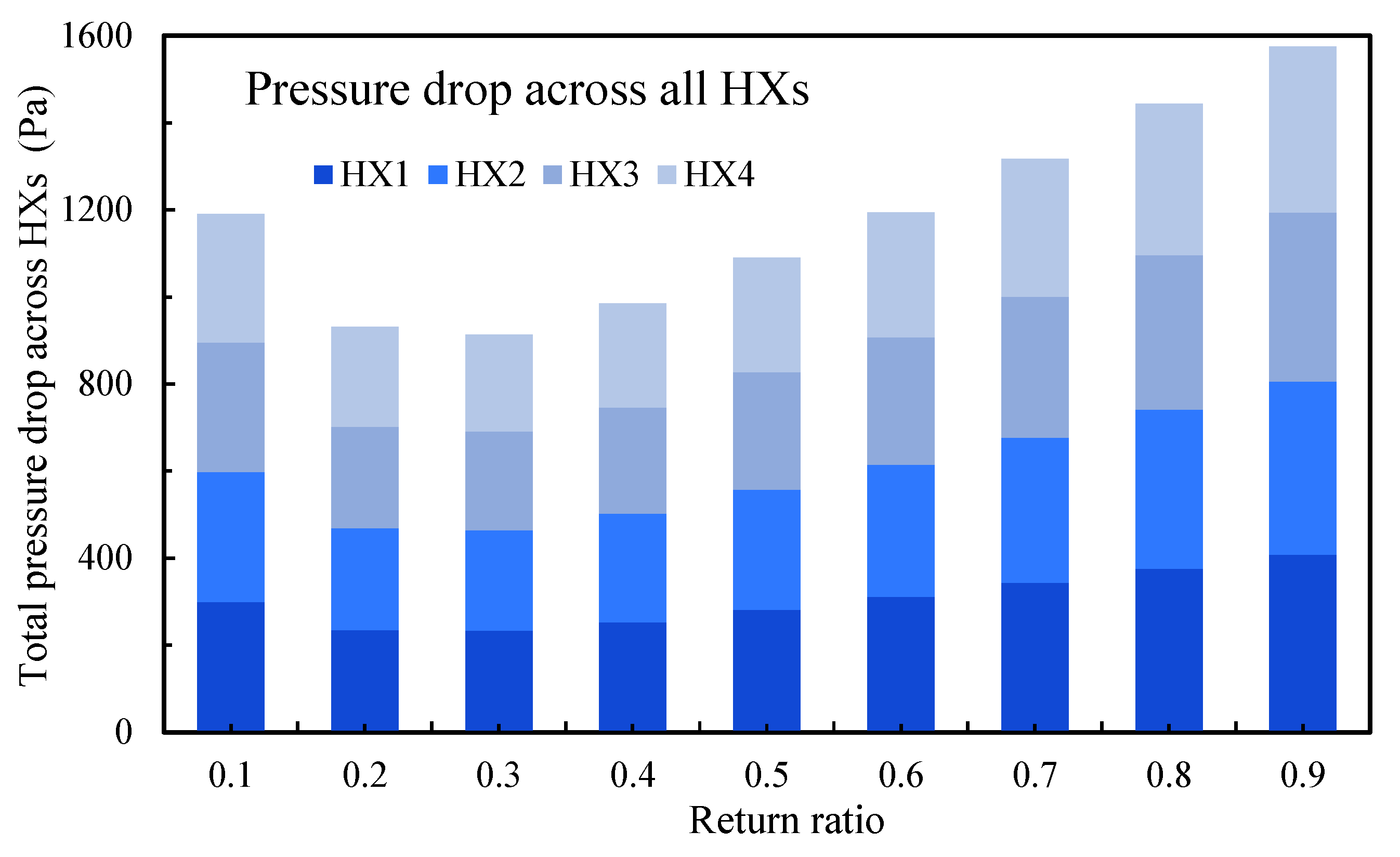

Figure 10 shows the combined pressure drops of all HXs for the dry and wet paths at each RR, representing the total resistance that should be encountered by the system fan in addition to the other components. The profile exhibits a minimum total pressure drop at RR = 0.3, which can be considered the optimum one. At low RRs, the high dry-path velocity dominates the pressure drop, while at high RRs, friction resistance in the long wet path becomes predominant. The lowest overall HXs’ pressure drop occurs at the intermediate RR of 0.3. Pressure drops remain near the minimum between RRs of 0.2 and 0.5, with a maximum increase of 19.3% over the minimum at an RR of 0.5.

Figure 10.

Contribution of each heat exchanger to the total pressure drop of the HXs at various return ratios.

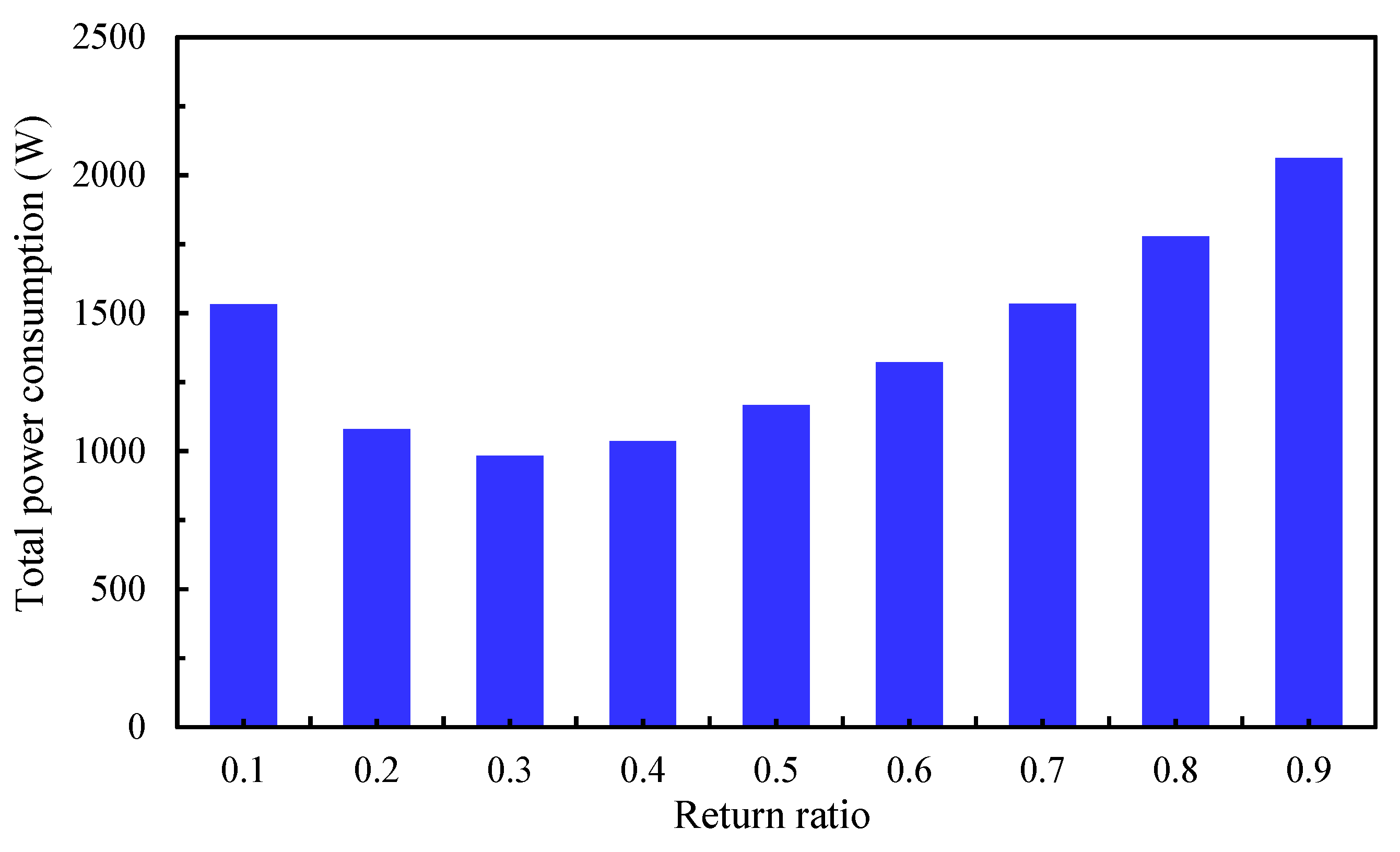

Figure 11 illustrates the total electrical power required to overcome the overall pressure drop in the system, including all components and heat exchangers (HXs), at different RRs. The results show that changes in the pressure drop across the HXs primarily drive variations in power consumption. The minimum power consumption occurs at an RR of 0.3, with a value of just 984 W. At RRs of 0.2, 0.5, and 0.7, the power demand is higher than this minimum by approximately 9.8%, 18.5%, and 57%, respectively. The significantly higher power consumption at larger RRs is due to the combination of larger HXs and the increased mass flow rate in the humid path. This suggests that while higher RRs may be beneficial for attaining lower supply temperatures, they incur the cost of substantially higher power consumption.

Figure 11.

The variation in total power consumption at different RRs.

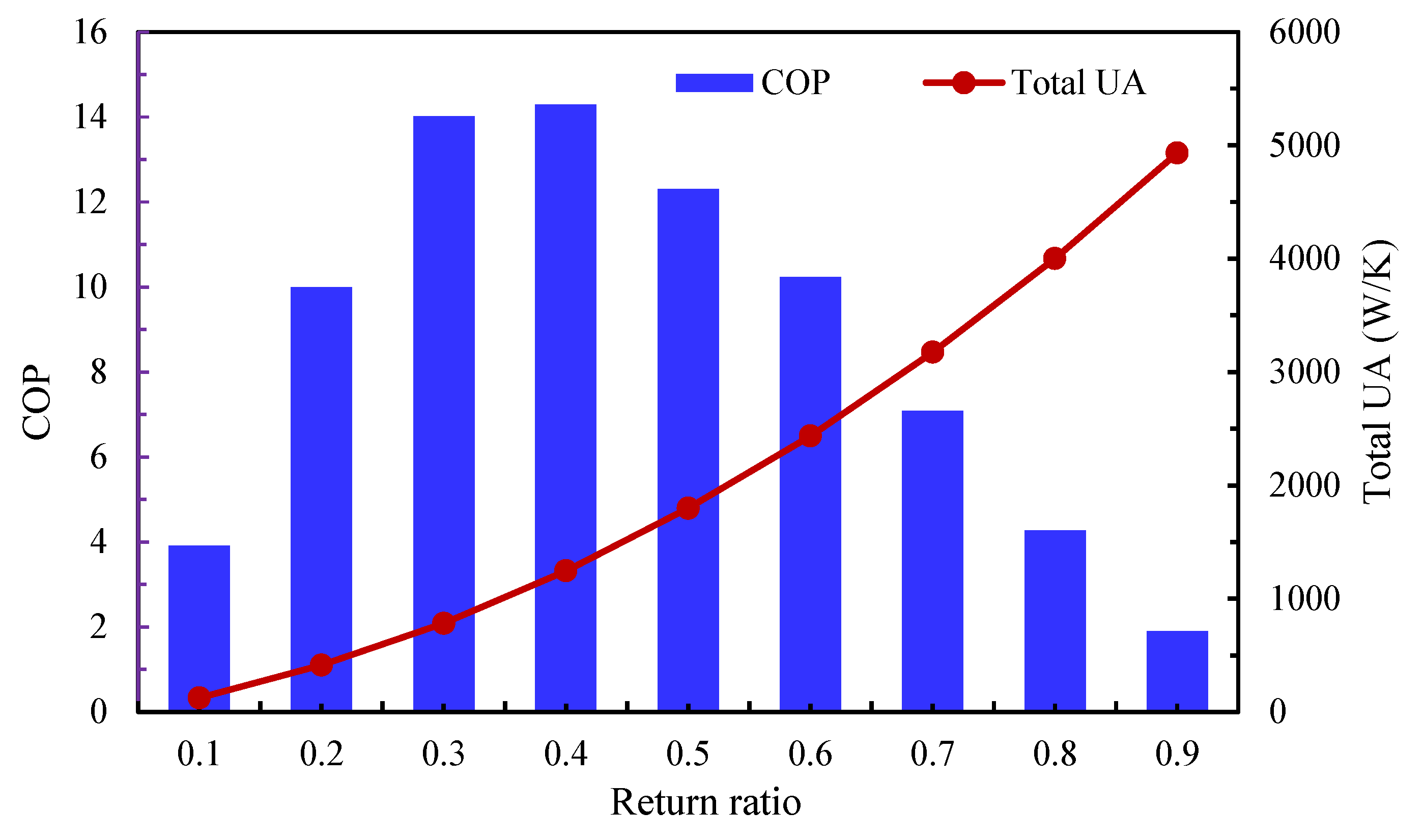

3.4. Impact of the Return Ratio on the Coefficient of Performance

Figure 12 illustrates the effect of RR on the coefficient of performance of the four-stage IEC, based on the base model input, along with the corresponding total UA values of the heat exchangers. The COP increases sharply from 3.92 at an RR of 0.1 to a peak of 14.29 at an RR of 0.4. Beyond this point, the COP declines steadily, dropping to below 2 at an RR of 0.9.

Figure 12.

The coefficient of performance and total heat transfer conductance across different RRs.

The peak COP at RR = 0.4 represents the system’s “sweet spot,” where maximum effective cooling capacity is achieved while fan power consumption remains near its minimum. At the same RR, the total UA value is 1245 W/K—only about one-third of the maximum UA value observed at RR = 0.9, making it more practical from a design perspective.

At RRs greater than 0.4, the sharp rise in fan power needed to overcome the increasing pressure drop, coupled with a reduction in effective cooling output, significantly reduces system energy efficiency. Consequently, despite higher UA values, the COP falls dramatically. This figure clearly demonstrates that an RR of around 0.4 provides the optimal balance, delivering the highest overall energy efficiency by maximizing cooling performance while minimizing electrical power consumption.

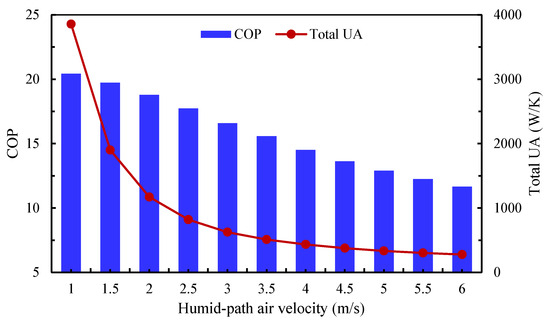

3.5. Optimization Study

As discussed earlier, the pressure drop along the heat exchangers (HXs) has a significant influence on the system’s coefficient of performance (COP). To mitigate this pressure drop, two parameters that were fixed in the base model (Table 2) vary in this section: (i) the HX depth, defined as the dimension normal to both the dry and humid streams, and (ii) the air velocity in the humid path. A parametric study was conducted in which the HX depth varied between 0.5 m and 1.5 m, and the humid-path air velocity between 1 m/s and 6 m/s. These ranges are consistent with common practice for air-to-air HXs.

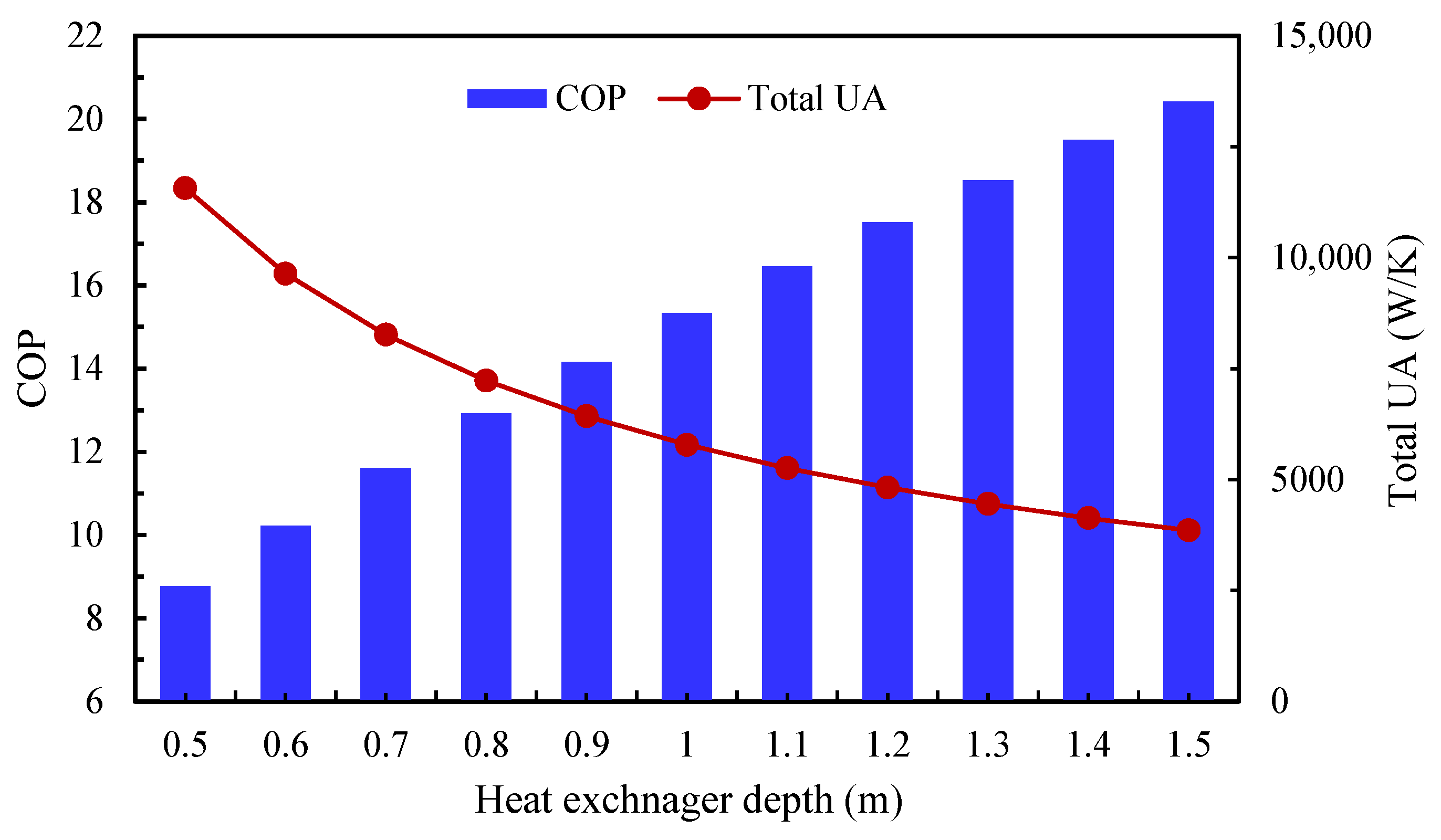

Figure 13 illustrates the effect of HX depth on the COP and total UA of the four-stage IEC system. In this case, the humid-path velocity was set to the minimum value of 1 m/s, and the RR was fixed at 0.3, conditions that yielded the lowest pressure drop in the previous analysis. The results show a strong positive correlation between HX depth and both COP and total UA. Increasing the depth from 0.5 m to 1.5 m enlarges the cross-sectional area, allowing the required airflow to be achieved with shorter HX length along the flow direction of both streams. This reduction in length lowers the pressure drop and consequently decreases fan power consumption. Since the effective cooling capacity is held constant, this reduction in power demand increases the COP from 8.77 at 0.5 m depth to a maximum of 20.42 at 1.5 m depth.

Figure 13.

The influence of heat exchanger depth on the system’s COP and total heat transfer conductance.

Meanwhile, the total UA value decreases significantly as HX depth increases. These findings demonstrate that increasing HX depth (normal to both flow directions in the cross-flow HX) is an effective strategy to enhance system energy efficiency. However, it remains constrained by practical considerations such as available space and manufacturability.

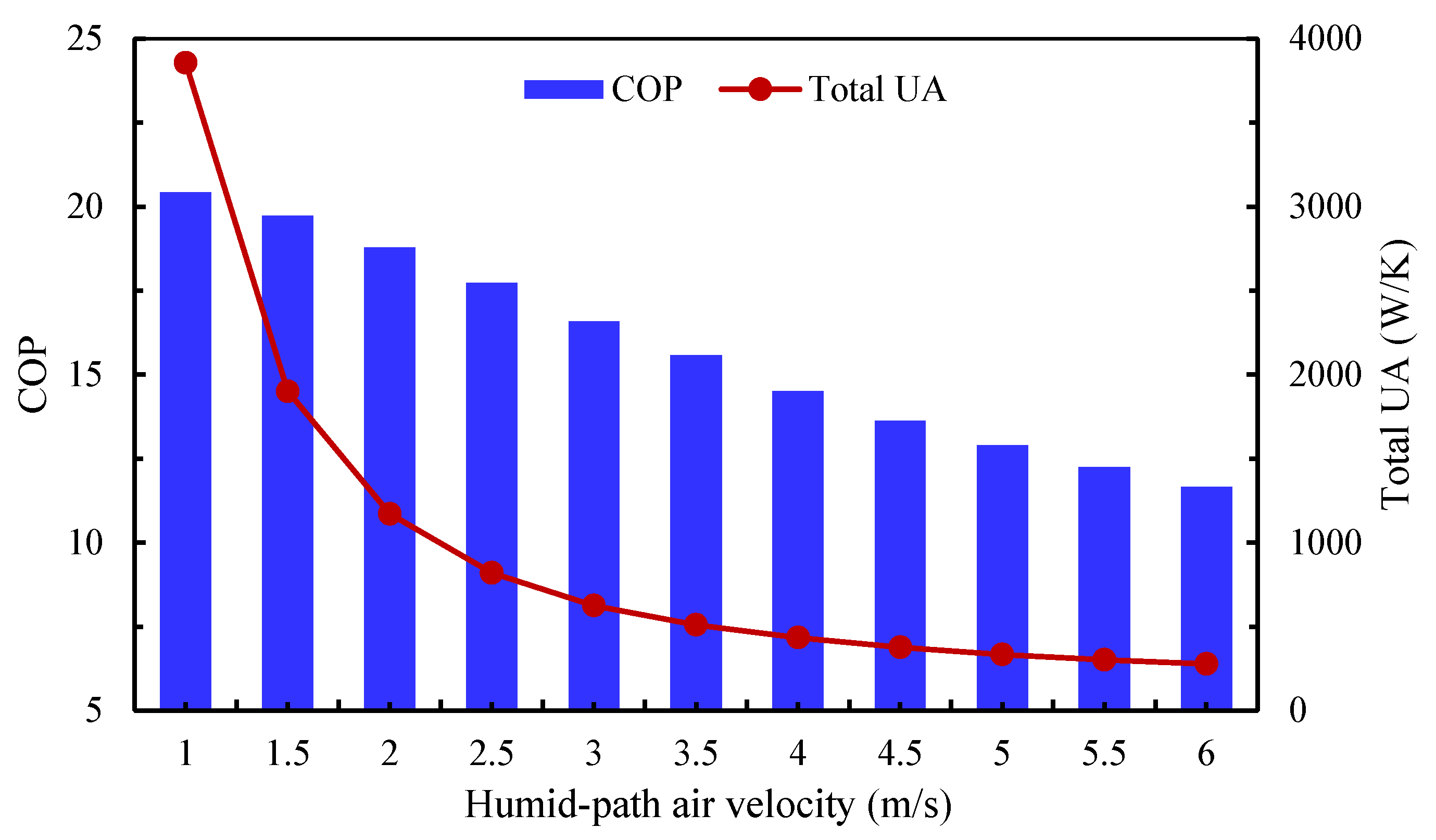

Figure 14 illustrates the effect of humid-path air velocity on the COP and total UA of the four-stage IEC system. The heat exchanger depth is fixed at its optimal value of 1.5 m, as shown in Figure 13, while all other parameters remain identical to those of the base model. Reducing the humid-path velocity to 1 m/s significantly improves the COP, reaching a maximum value of 20.42—an increase of 23% compared to the case with 3 m/s at the same HX depth. This improvement is primarily attributed to the reduction in pressure drop, which outweighs the concurrent increase in total UA at lower velocities. In this case, the pressure drop is more sensitive to velocity reduction than to the effect of the extended surface area.

Figure 14.

The influence of humid-path air velocity on the system’s COP and total heat transfer conductance.

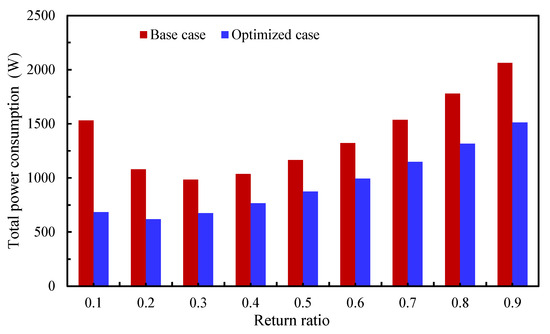

A single-objective optimization study was conducted to maximize the COP across different return ratios (RRs), considering the simultaneous variation of two parameters: HX depth and humid-path air velocity. The optimization was performed using the EES software, which enables the optimization of various parameters within specified upper and lower bounds. In this study, the HX depth was varied between 0.5 m and 1.5 m, while the humid-path velocity ranged from 1 m/s to 6 m/s.

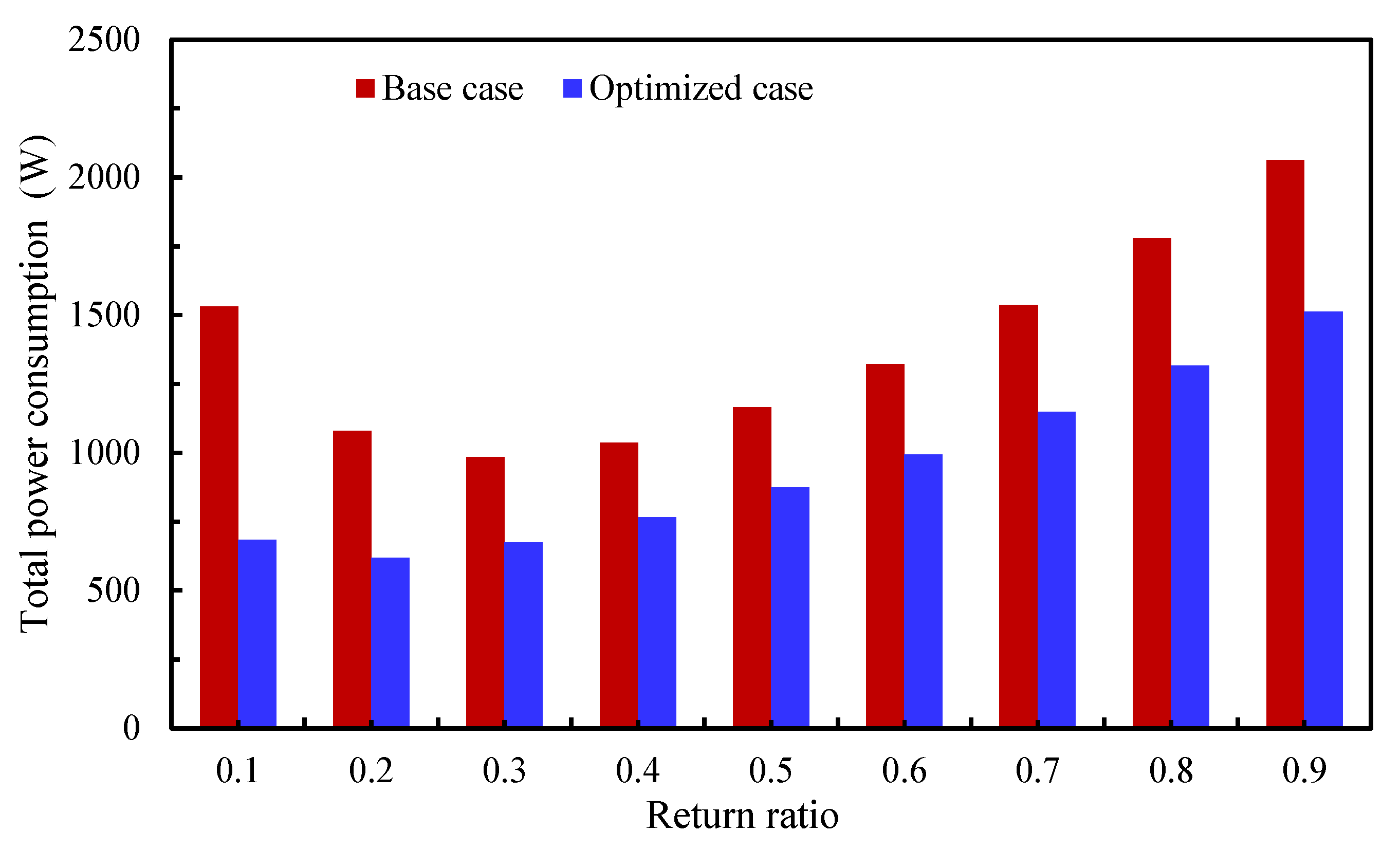

The results are consistent with the individual parametric studies at a fixed RR of 0.3 presented in Figure 13 and Figure 14, showing that the maximum COP at each RR is achieved with the HX depth (1.5 m) combined with the humid-path velocity (1 m/s). Figure 15 compares the total power consumption between the base case and the optimized case, demonstrating a substantial reduction in power usage with the optimized parameters for all RRs. Specifically, total power consumption decreased by 31.4% and 26.1% at RRs of 0.3 and 0.4, respectively, while the maximum reduction of 55.3% occurred at RR = 0.1. These reductions directly support higher system performance, as reflected in the COP improvements shown in Figure 16 compared with the reference case in Figure 12.

Figure 15.

Comparison of total power consumption between the base case and the optimized case at various RRs.

Figure 16.

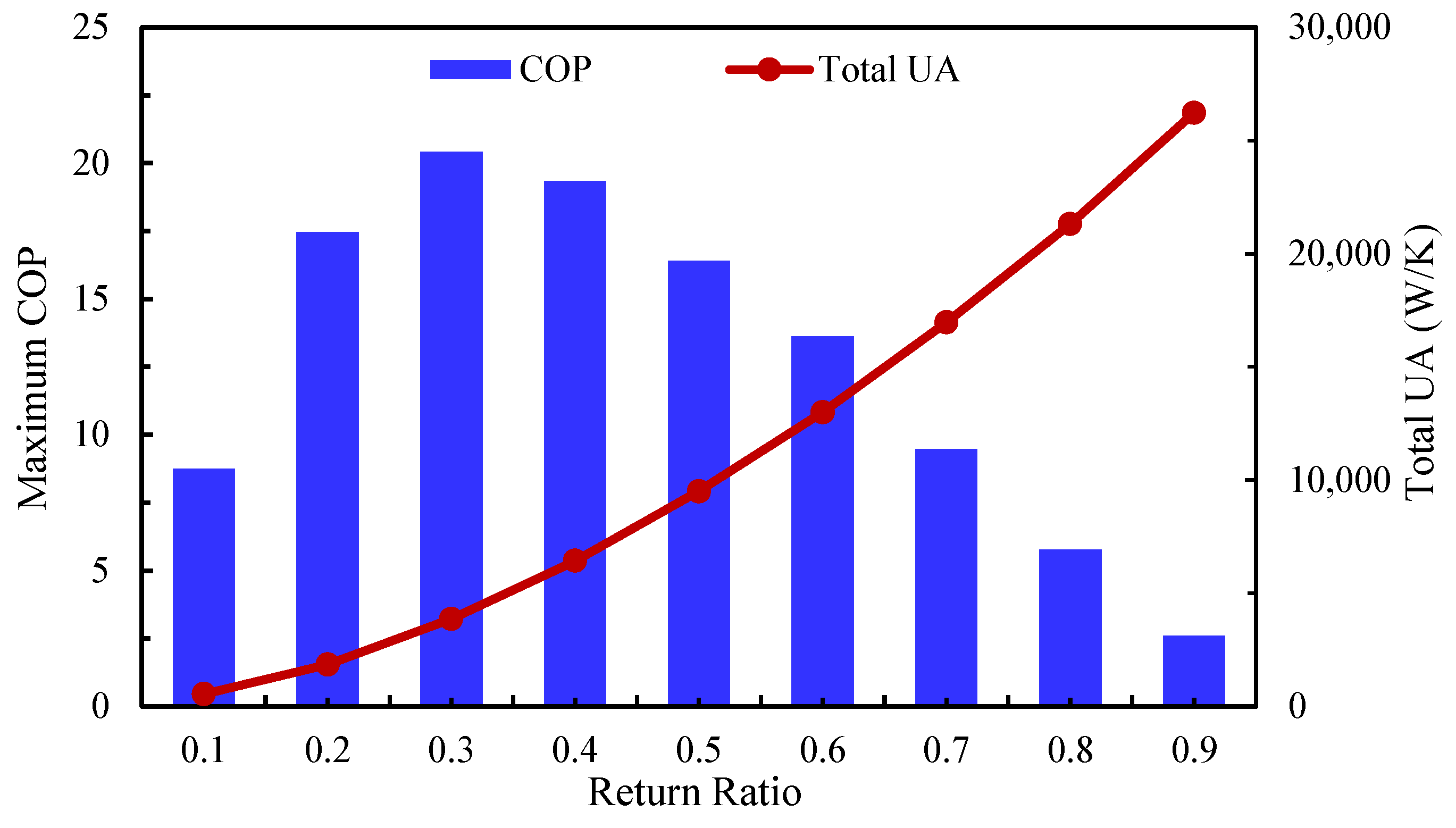

The maximum COP and corresponding total UA at the optimized parameters (1.5 m depth, 1 m/s humid-air velocity).

Figure 16 illustrates the system performance under optimized parameters, with a peak COP of 20.4 at RR = 0.3, compared to 14.3 at RR = 0.4 in the non-optimized case. This corresponds to a 42.7% improvement. At RR = 0.4, the optimized case yields a COP that is 35% higher than the base case. Such gains in COP can be translated into significant reductions in operating costs, enhancing the feasibility of adopting the four-stage IEC system across a wider range of applications.

However, these performance improvements are accompanied by a notable increase in the total heat transfer conductance of all HXs (total UA). For example, at the peak COP conditions of both the base and optimized cases, the total UA increases from 1245.4 W/K (RR = 0.4) to 3856.8 W/K (RR = 0.3)—a threefold increase—corresponding to effective cooling capacities of 14.8 kW and 13.8 kW, respectively. This indicates that minimizing operating costs comes at the expense of a larger system size, since higher UA values require larger heat exchangers. This trade-off suggests that more advanced HX designs with extended surface areas could mitigate size requirements while minimizing the impact on pressure drop.

As shown in the performance comparison in Table 4, the optimized design delivers a substantial improvement in energy efficiency compared to the base case. These results provide a practical framework for designing and operating multistage IEC systems, enabling them to achieve maximum efficiency and serve as a viable alternative to conventional vapor-compression systems in arid climates, thereby contributing to the global demand for sustainable cooling solutions.

Table 4.

Summary of the comparison between the base case and optimized case at peak COP.

4. Conclusions

This study combined comprehensive thermodynamic and energy consumption models to optimize the performance of a four-stage indirect evaporative cooling system operating under the outdoor summer design conditions of Riyadh city. The following are the main findings:

- The optimization study demonstrated that simultaneously reducing the humid-path air velocity and increasing the HX depth can substantially improve the system performance.

- The maximum COP increased from 14.3 in the base case (RR = 0.4) to 20.4 in the optimized case (RR = 0.3), corresponding to a 42.7% improvement, while total power consumption decreased by up to 55.3% at RR = 0.1. However, these gains were accompanied by a threefold increase in total UA, rising from 1245.4 W/K in the base case to 3856.8 W/K in the optimized case, highlighting the trade-off between energy efficiency and system size.

- These findings suggest that more advanced heat exchanger designs, particularly those incorporating extended surface areas, are required to achieve the performance benefits of optimization while minimizing increases in size and pressure drop.

- The optimized multistage IEC system with a high COP of 20.4 not only improves energy efficiency compared to the base case but also demonstrates significant potential as a sustainable alternative to conventional vapor-compression cooling. It offers a viable pathway for meeting the growing demand for environmentally responsible cooling solutions, particularly in arid regions where water–energy challenges are most critical.

- Future research should focus on experimentally validating the optimized four-stage IEC design, conducting a comprehensive techno-economic analysis comparing its cost-effectiveness with conventional systems, and developing dynamic control strategies to sustain peak COP performance under varying operating conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.B.E. and O.Z.; Methodology, N.S.A.A.F., M.B.E. and O.Z.; Software, N.S.A.A.F., M.B.E. and O.Z.; Validation, N.S.A.A.F., M.B.E. and O.Z.; Formal analysis, N.S.A.A.F., M.B.E. and O.Z.; Investigation, N.S.A.A.F. and M.B.E.; Data curation, N.S.A.A.F. and M.B.E.; Writing—original draft, N.S.A.A.F. and M.B.E.; Writing—review and editing, M.B.E. and O.Z.; Visualization, N.S.A.A.F., M.B.E. and O.Z.; Supervision, M.B.E. and O.Z.; Funding acquisition, M.B.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors would like to thank the Ongoing Research Funding program (ORFFT-2025 035-5), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, for financial support.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| AC | Air conditioning |

| COP | Coefficient of performance |

| D | Points in the dry path |

| DEC | Direct evaporative cooler |

| EES | Engineering Equation Solver |

| GHG | Greenhouse gas |

| H | Points in the humid path |

| HVAC | Heating, ventilation, and air conditioning |

| HX | Heat exchanger |

| IEC | Indirect evaporative cooler |

| TEWI | Total equivalent warming impact |

| VCR | Vapor compression cooling |

Nomenclature

| a | Divider width (m) |

| A | Heat transfer area (m2) |

| Afr | Frontal area (m2) |

| b | Width of the passage (m) |

| Specific heat capacity (kJ/kg K) | |

| Dh | Hydraulic diameter (m) |

| f | Friction factor (--) |

| F | Correction factor (--) |

| G | Maximum mass velocity (kg/m2 s) |

| h | Convective heat transfer coefficient (W/m2 K) |

| h | Enthalpy (kJ/kg) |

| jH | Colburn j-factor for heat transfer (--) |

| k | Thermal conductivity (W/m K) |

| L | Length of heat exchanger in flow direction (m) |

| Mass flow rate (kg/s) | |

| P | Pressure (Pa) |

| Q | Heat transfer rate (kW) |

| RR | Return ratio (--) |

| Re | Reynolds number (--) |

| SWC | Specific water consumption (kg/kWh) |

| St | Stanton number (--) |

| T | Temperature (°C or K) |

| U | Overall heat transfer coefficient (kW/m2 K) |

| Utilization factor (--) | |

| V | Air velocity (m/s) |

| Humidity ratio (gwv/kga) | |

| Greek Letters | |

| P | Pressure drop (Pa) |

| Log-mean temperature difference (K) | |

| μ | Dynamic viscosity (Pa s) |

| ρ | Density (kg/m3) |

| σ | Ratio of freeflow area to frontal area (--) |

| Empirical function (--) | |

| Subscript | |

| a | Air |

| D | Dry path |

| eff | Effective |

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Aspen Plus flowsheet for the four-stage IEC modified with Pad-S.

Figure A1.

Aspen Plus flowsheet for the four-stage IEC modified with Pad-S.

Figure A2.

Design conditions for Riyadh from ASHRAE [37].

Figure A2.

Design conditions for Riyadh from ASHRAE [37].

References

- Kian Jon, C.; Islam, M.R.; Kim Choon, N.; Shahzad, M.W. Future of Air Conditioning. In Advances in Air Conditioning Technologies: Improving Energy Efficiency; Kian Jon, C., Islam, M.R., Kim Choon, N., Shahzad, M.W., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 17–52. [Google Scholar]

- Günel, G. Air Conditioning the Arabian Peninsula. Int. J. Middle East Stud. 2018, 50, 573–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, T.; Sayin, L. Future-Proofing Sustainable Cooling Demand; Asian Development Bank Institute: Tokyo, Japan, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Viswambharan, A.; Patidar, S.K.; Saxena, K. Sustainable HVAC Systems in Commercial and Residential Buildings. Int. J. Sci. Res. Publ. 2014, 4, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Kant, K.; Shukla, A.; Sharma, A. Heating Ventilation and Air-Conditioning Systems for Energy-Efficient Buildings. In Sustainability Through Energy-Efficient Buildings; Taylor and Francis: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018; pp. 165–180. [Google Scholar]

- Baxter, V.D.; Radermacher, R. IEA/HPT Annex 53 Advanced Cooling/Refrigeration Technologies Development—Task 1 Report; Oak Ridge National Laboratory: Oak Ridge, TN, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, L.W.; Gertler, P.J. Contribution of air conditioning adoption to future energy use under global warming. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 5962–5967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshahrani, J.; Boait, P. Reducing High Energy Demand Associated with Air-Conditioning Needs in Saudi Arabia. Energies 2019, 12, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sulaiman, F.A.; Zubair, S.M. A survey of energy consumption and failure patterns of residential air-conditioning units in Eastern Saudi Arabia. Energy 1996, 21, 967–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Nakla, S. Estimating Household’s Energy Consumption of Summer Cooling in Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia. In Proceedings of the 2024 6th International Symposium on Advanced Electrical and Communication Technologies (ISAECT), Al Khobar, Saudi Arabia, 3–5 December 2024; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Elsheniti, M.B.; Dawood, M.M.; Abdelaziz, A.H.; Elhelw, M. Thermo-economic study on the use of desiccant-packed aluminum-foam heat exchangers in a new air-handling unit for high moisture-removal. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2022, 33, 101967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badawy Elsheniti, M.; Shehata, A.; El-Hamid Attia, A.; El-Maghlany, W. Performance evaluation of an innovative liquid desiccant air-conditioning system directly integrating a heat pump with two membrane energy exchangers. Energy Convers. Manag. 2023, 293, 117508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, S.A.; Almehmadi, F.A.; Aljabr, A.; Kaood, A. Performance analysis of twisted tape inserts and nanofluids in double-pipe helical coil heat exchangers. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2025, 150, 11197–11211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatkar, V.W.; Kriplani, V.M.; Awari, G.K. Alternative refrigerants in vapour compression refrigeration cycle for sustainable environment: A review of recent research. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 10, 871–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezzutto, S.; Quaglini, G.; Riviere, P.; Kranzl, L.; Novelli, A.; Zambito, A.; Wilczynski, E. Screening of Cooling Technologies in Europe: Alternatives to Vapour Compression and Possible Market Developments. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhabhor, K.K.; Jani, D.B. Progressive development in solid desiccant cooling: A review. Int. J. Ambient. Energy 2022, 43, 992–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.A.; Saha, B.B. TEWI Assessment of Conventional and Solar Powered Cooling Systems. In Solar Energy: Systems, Challenges, and Opportunities; Tyagi, H., Chakraborty, P.R., Powar, S., Agarwal, A.K., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 147–177. [Google Scholar]

- Novais, W.R.I.; Cerqueira, E.P.; Narváez-Romo, B.; Simões-Moreira, J.R. Thermodynamic and Heat Transfer Analysis of Cooling Technologies: A Comparative Study. Rev. Eng. Térmica 2022, 21, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kian Jon, C.; Islam, M.R.; Kim Choon, N.; Shahzad, M.W. Present State of Cooling, Energy Consumption and Sustainability. In Advances in Air Conditioning Technologies: Improving Energy Efficiency; Kian Jon, C., Islam, M.R., Kim Choon, N., Shahzad, M.W., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Elsheniti, M.B.; Al-Ansary, H.; Orfi, J.; El-Leathy, A. Performance Evaluation and Cycle Time Optimization of Vapor-Compression/Adsorption Cascade Refrigeration Systems. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsheniti, M.B.; AlRabiah, A.; Al-Ansary, H.; Almutairi, Z.; Orfi, J.; El-Leathy, A. Performance Assessment of an Ice-Production Hybrid Solar CPV/T System Combining Both Adsorption and Vapor-Compression Refrigeration Systems. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, S.; Zubir, M.N.B.M.; Muhamad, M.R.B.; Newaz, K.M.S.; Öztop, H.F.; Alam, M.S.; Shaikh, K. Technological development of evaporative cooling systems and its integration with air dehumidification processes: A review. Energy Build. 2023, 283, 112805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishugah, T.F.; Kiplagat, J.; Madete, J.; Musango, J.; Ahmed, M. Current Status, Challenges, and Opportunities of Evaporative Cooling for Building Indoor Thermal Comfort Using Water as a Refrigerant: A Review. Int. J. Energy Res. 2024, 2024, 1026136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalsia, M.; Sharma, A.; Kaushik, R.; Raja Sekhar, D. Evaporative Cooling Technologies: Conceptual Review Study. Evergreen 2023, 10, 421–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, R.A.; Abdulqader, M.A.; Alias, A.B.; Hussein, N.A.; Ahmed, O.K.; Keighobadi, J.; Saleh, A.M.; Hamad, Z.K.; Saleh, N.M.; Mahmood, M.K. Advancements and Performance of Evaporative Cooling Technologies: Applications, Benefits, and Future Prospects. Khwarizmia 2025, 2025, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuce, P.M.; Riffat, S. A state of the art review of evaporative cooling systems for building applications. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 54, 1240–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ken Mortensen. A Review of Evaporative Cooling’s Efficiency and Environmental Value. ASHRAE J. 2022, 56–65. Available online: https://spxcooling.com/wp-content/uploads/Review_Evaporative_Cooling_Efficiency.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Haile, M.G.; Garay-Martinez, R.; Macarulla, A.M. Review of Evaporative Cooling Systems for Buildings in Hot and Dry Climates. Buildings 2024, 14, 3504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.K.; Arora, B.B.; Arora, A. Thermodynamic Performance Assessment of Air Conditioner Combining Evaporative and Passive Cooling. J. Therm. Sci. Eng. Appl. 2024, 16, 051003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, W.; Ali, M.; Sheikh, N.A.; Akhtar, J. Effect of efficient multi-stage indirect evaporative cooling on performance of solar assisted desiccant air conditioning in different climatic zones. Heat Mass Transf. 2020, 56, 2725–2741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kousar, R.; Ali, M.; Sheikh, N.A.; Gilani, S.I.u.H.; Khushnood, S. Holistic integration of multi-stage dew point counter flow indirect evaporative cooler with the solar-assisted desiccant cooling system: A techno-economic evaluation. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2021, 62, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Wang, C.; Chang, Z.; Li, W.; Zhang, C. Heat Transfer Modelling of Plate Heat Exchanger in Solar Heating System. Open J. Fluid Dyn. 2017, 7, 426–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasif, M.S. Air-to-Air Fixed Plate Energy Recovery Heat Exchangers for Building’s HVAC Systems. In Sustainable Thermal Power Resources Through Future Engineering; Sulaiman, S.A., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 63–71. [Google Scholar]

- Onaha, T.O.; Nwankwo, A.M.; Tor, F.L. Design and development of a trapezoidal plate fin heat exchanger for the prediction of heat exchanger effectiveness. Eur. J. Mater. Sci. 2020, 7, 29–45. [Google Scholar]

- Jamil, M.A.; Imtiaz, N.; Ng, K.C.; Xu, B.B.; Yaqoob, H.; Sultan, M.; Shahzad, M.W. Experimental and parametric sensitivity analysis of a novel indirect evaporative cooler for greener cooling. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2023, 42, 101887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsheniti, M.B.; Al Fardi, N.; Zeitoun, O. Thermal performance assessment of an innovative multistage indirect evaporative cooler designed to supply fresh and hygienic air. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2025, 74, 107037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASHRAE. Riyadh, Saudi Arabia (WMO 404370)—ASHRAE Design Conditions; ASHRAE: Peachtree Corners, GA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kays, W.M.; London, A.L. Compact Heat Exchangers, 3rd ed.; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).