Abstract

The rapid rise of fashion resale platforms has created new pathways for sustainable consumption, yet little research has compared how different governance models, company-controlled versus seller-controlled, shape consumer trust and purchasing behavior. This study addresses that gap by applying the Stimulus–Organism–Response (SOR) framework to examine how information precision, authenticity, and risk aversion influence consumer trust and purchase intention within circular fashion markets. Drawing on an experimental design with 524 U.S. consumers randomly assigned to each platform type, multi-group structural equation modeling reveals that the three stimuli significantly enhance trust, which in turn drives purchase intention. Risk aversion exerted stronger effects in company-controlled contexts, whereas trust translated more directly into purchase intention on seller-controlled platforms. Theoretically, the research extends SOR applications to sustainability by identifying trust as the psychological bridge linking platform design to circular consumption. Practically, it offers actionable guidance for brands and peer-to-peer platforms on authentication, information transparency, and risk-reduction strategies that strengthen consumer confidence and promote environmentally responsible resale participation. The findings advance understanding of how governance structures can accelerate sustainable fashion retailing and contribute to the circular economy.

1. Introduction

The global secondary apparel market has become a cornerstone of the circular economy, driven by consumers’ growing concern for sustainability, affordability, and authenticity. Once a niche segment, fashion resale is now a mainstream phenomenon as it is projected to reach USD 367 billion globally by 2029 and account for one-quarter of U.S. apparel sales by 2027 [1]. This rapid growth signifies a fundamental behavioral shift from linear “take–make–dispose” consumption toward reuse, repair, and resale practices that extend product lifecycles and reduce waste [2,3].

Despite this momentum, a persistent attitude–behavior gap remains: many consumers express environmental concern but hesitate to purchase secondhand goods [4,5]. A key barrier is trust as consumers question the authenticity, quality, and reliability of pre-owned fashion. Understanding how platform design and governance reduce perceived risk and foster trust is therefore central to advancing sustainable consumption.

Two distinct governance models dominate the resale landscape. Company-controlled platforms (e.g., Levi’s SecondHand, Patagonia Worn Wear, ThredUp) are managed by brands that authenticate, curate, and resell items, offering institutional assurances and consistent quality control. Seller-controlled platforms (e.g., Poshmark, Depop, Etsy) enable peer-to-peer transactions based on community interaction, reputation systems, and social validation. Both structures support circularity but differ fundamentally in how they build and communicate trust. Yet, empirical comparisons of these governance types remain scarce, leaving an important conceptual gap in understanding how consumers interpret and respond to distinct trust mechanisms in digital resale ecosystems.

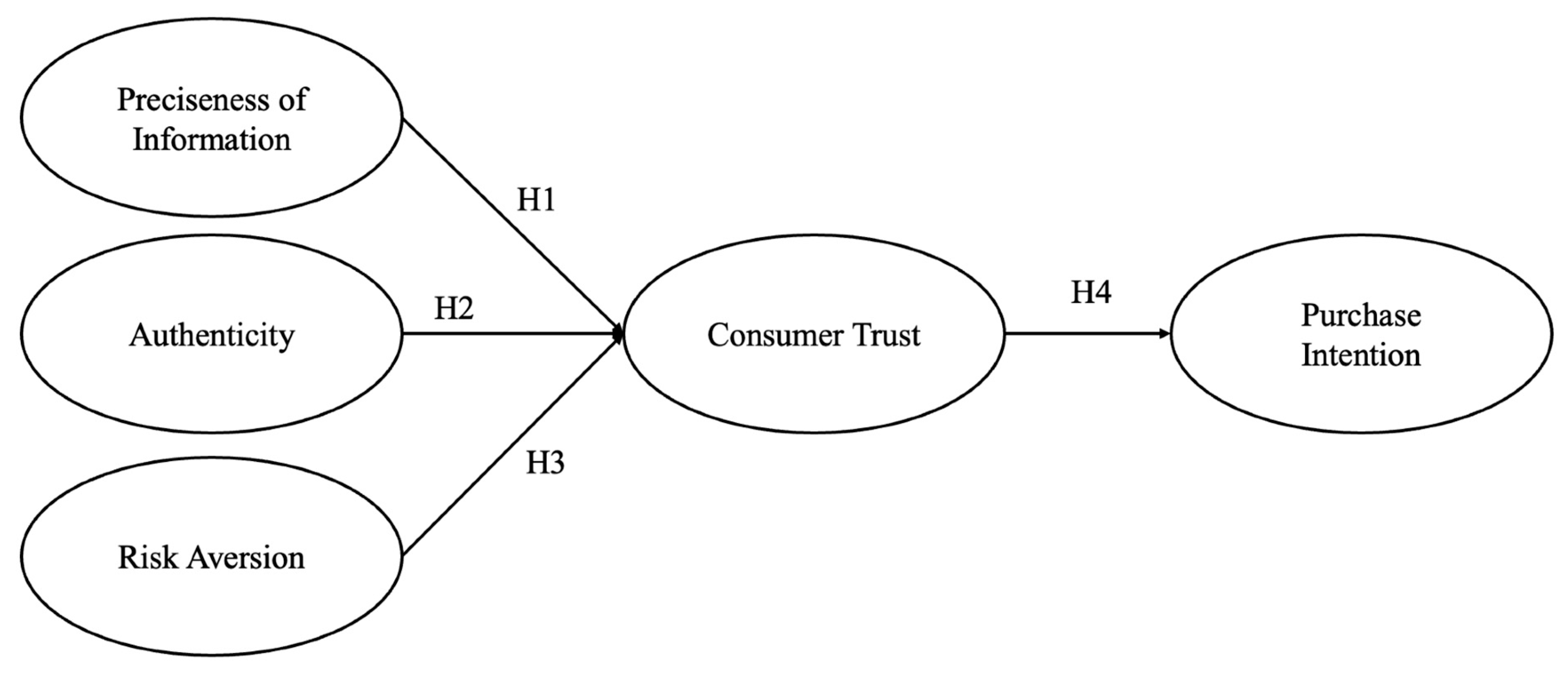

To address this gap, the present study applies the Stimulus–Organism–Response (SOR) framework [6] to examine how platform-specific stimuli influence psychological and behavioral responses in sustainable fashion contexts. The SOR model posits that environmental stimuli (S), such as information precision, authenticity, and risk aversion, shape internal organismic states (O), such as trust, which in turn drive behavioral responses (R), such as purchase intention. Integrating SOR into circular fashion research enables a structured analysis of how cognitive and affective mechanisms translate digital platform design into sustainable consumer behavior.

Accordingly, this study explores how company-controlled and seller-controlled resale platforms differ in activating trust and purchase intention. It contributes to sustainability scholarship by: (1) extending SOR theory to circular fashion markets, identifying how digital stimuli influence trust and sustainable action; (2) clarifying the psychological mechanisms, particularly authenticity, information quality, and risk perception, that explain consumer participation in resale; and (3) comparing platform governance structures to reveal how institutional and community-based trust mechanisms support circular economy goals.

To guide the empirical investigation, the following research questions were developed:

- RQ1: How do the stimuli of information precision, authenticity, and risk aversion influence consumer trust in secondary fashion marketplaces?

- RQ2: How does consumer trust shape purchase intention across company-controlled and seller-controlled resale platforms?

- RQ3: Do these relationships differ significantly between platform types, and how do these structural variations affect sustainable consumption behavior?

2. Review of Literature

2.1. Secondary Markets and Sustainability

The rise of fast fashion has accelerated consumer demand for affordable apparel, but it has also amplified sustainability concerns by driving overproduction and textile waste [7]. As consumers become increasingly aware of the environmental costs of fashion, the secondary apparel market has emerged as a critical alternative, providing both affordability and a pathway to circularity [8,9]. Recent surveys indicate that affordability remains the leading motivator for secondhand consumption, with 45% of U.S. consumers reporting price as a primary driver. However, sustainability is becoming increasingly salient as 17% of consumers now cite environmental reasons when purchasing secondhand goods [1].

Secondary marketplaces contribute to sustainability by reducing carbon emissions, lowering water consumption, and diverting garments from landfills [7]. Platforms such as Poshmark, eBay, and ThredUp often highlight their environmental impact, appealing to consumers who consciously align with “reduce, reuse, and recycle” principles [1]. Practices such as upcycling further enhance sustainability by transforming discarded items into higher-value artifacts, thereby extending product lifecycles and promoting creative reuse [7].

Secondary market consumers often identify as environmentally conscious, practicing mindful consumption by prioritizing sustainability and rejecting overconsumption [1,7]. The environmental implications of resale are substantial. By extending the average lifespan of garments, secondary markets can reduce carbon emissions, water consumption, and waste generation by as much as 30–40% compared to new apparel production [10,11]. However, this potential is only realized when consumers actively participate in resale rather than simply adding secondhand purchases to existing overconsumption patterns [12]. The “attitude–behavior gap” continues to hinder progress toward circularity, as consumers who claim sustainability consciousness often prioritize convenience, price, or fashion novelty over ecological impact [4,13]. Consequently, platform-level trust mechanisms, information transparency, and authentication assurances may serve as behavioral enablers that align sustainable attitudes with actual purchase intentions. This study therefore situates resale participation not only as a commercial choice but as a measurable form of circular behavior that contributes to environmental sustainability [14,15].

Research suggests that eco-conscious consumers perceive resale as both a personal obligation and a means of contributing to collective sustainability goals [15,16]. However, gaps remain between consumer awareness and actual purchasing behavior. While many consumers express pro-environmental attitudes, these do not always translate into consistent resale practices [17]. Furthermore, limited consumer awareness of the measurable environmental benefits of resale persists [4]. Bridging this awareness-action gap is critical for leveraging secondary markets as effective mechanisms within the circular economy.

2.2. Exclusivity and Hedonic Motivations for Secondhand Consumption

Beyond economic and environmental considerations, secondary markets also fulfill hedonic and symbolic consumer motivations. For many shoppers, resale provides the thrill of discovering rare, vintage, or one-of-a-kind pieces. These forms of exclusivity serve not only functional needs but also symbolic ones, enhancing personal identity and social image [18]. Upcycling plays a particularly important role in this domain, as it enables consumers to participate in the creative transformation of pre-owned goods, thereby reinforcing both individuality and sustainability [7].

Hedonic motivations resonate strongly with younger consumers, who often view resale platforms as cultural spaces as much as commercial ones [1]. The sense of community, novelty, and personalization associated with seller-controlled platforms such as Poshmark demonstrates how hedonic drivers intersect with sustainability by encouraging extended product use and reducing waste.

2.3. Secondary Marketplace Strategies

Secondary marketplaces can broadly be categorized into company-controlled and seller-controlled models, each with distinct advantages and challenges. Company-controlled platforms, such as ThredUp, The RealReal, and Vestiaire Collective, emphasize authentication, certification, and curated assortments. For example, The RealReal has partnered with luxury brands such as Gucci and Burberry and reports on significant environmental savings, including 3.9 billion liters of water conserved and over 73,000 metric tons of carbon emissions avoided [19]. Similarly, ThredUp operates a resale-as-a-service model, collaborating with brands like Athleta and GAP to integrate resale into mainstream retail [20]. These company-driven initiatives reinforce brand legitimacy and enhance consumer trust by aligning resale with sustainability commitments [11].

In contrast, seller-controlled platforms such as Etsy, Poshmark, and Mercari enable individuals to directly list and sell items. These peer-to-peer environments thrive on interpersonal trust, social proof, and electronic word-of-mouth [21]. Etsy’s strict focus on handmade and vintage products highlights its cultural positioning as a marketplace for creativity and authenticity [22]. Poshmark’s community-driven “Posh Parties” illustrate how digital interactions encourage collaborative consumption, while Mercari demonstrates how seller-controlled platforms can successfully scale across international contexts. Seller-controlled platforms tend to attract younger, price-sensitive consumers seeking both affordability and uniqueness, reinforcing the role of community engagement in sustainability outcomes [1].

2.4. Research Gap

While secondary markets clearly support circular economic objectives, empirical research comparing different platform strategies remains limited. Existing studies have not adequately examined how company-controlled resale models (e.g., Vestiaire Collective, TredUp, The RealReal) differ from seller-controlled platforms (e.g., Poshmark, Etsy, Mercari) in shaping consumer perceptions of authenticity, risk, and trust. Moreover, most existing work is U.S.-focused, leaving significant gaps in understanding cross-cultural differences in resale adoption [2,4,11,13,23].

Additionally, sustainability measurement within resale remains underdeveloped. While platforms often report metrics such as saved water or carbon avoided [19,24], systematic academic approaches to quantifying the environmental and social impacts of resale are scarce [4]. Research is also needed on how consumer awareness of these metrics influences purchase intentions, as evidence suggests a persistent gap between pro-environmental attitudes and actual resale behavior [17,25]. Finally, technological innovations such as blockchain, life-cycle assessment tools, and advanced supply chain analytics hold potential for improving transparency and measuring sustainability outcomes in secondary markets, yet scholarly research has only begun to address these opportunities.

Furthermore, the growing body of research on circular fashion suggests that second-hand consumption patterns differ markedly across generational cohorts, with younger consumers (Gen Z and Millennials) exhibiting stronger hedonic and community-driven motives, while older cohorts prioritize value retention and product longevity. However, few empirical studies compare these generational drivers within company-controlled versus seller-controlled contexts. In addition, the role of social media, particularly Instagram, TikTok, and platform-embedded communities such as Depop and Poshmark, remains under-explored despite its centrality in shaping peer influence, digital trust, and sustainability signaling. The emergence of authentication technologies (e.g., AI-enabled image recognition, blockchain certificates, and digital passports) also warrants systematic study, as these tools can reduce perceived risk and increase transparency in circular markets. Finally, limited research addresses cross-cultural differences in resale adoption or the use of standardized sustainability metrics to quantify environmental gains from secondary transactions. Incorporating these dimensions would create a more holistic understanding of how demographic, technological, and cultural variables interact to drive sustainable participation in the resale ecosystem.

Despite the growth of research on circular fashion, empirical understanding of how resale platforms foster sustainable behavior remains limited. Studies highlight that while consumers recognize the ecological benefits of buying secondhand, decision-making is still shaped by perceived social risk, trust, and product authenticity [26,27]. Addressing this behavioral gap requires integrating consumer psychology with sustainability metrics, linking perceived trustworthiness of resale platforms to measurable reductions in environmental impact [3,13]. By focusing on company- versus seller-controlled models, the present study contributes to circular economy literature by explaining how governance design mediates sustainable participation within digital secondary markets.

2.5. Theoretical Framework: Stimulus–Organism–Response (SOR)

The Stimulus–Organism–Response (SOR) model [6] provides a useful theoretical lens for examining consumer behavior in secondary markets. Beyond the foundational SOR paradigm [6], contemporary digital-commerce studies validate SOR pathways in real e-commerce settings, including personalized recommendations, livestreaming, and AR/VR [28,29,30]. The framework posits that external stimuli (S) influence internal psychological states (O), which in turn shape behavioral responses (R). Within retail and online commerce research, SOR has been widely applied to explain how platform attributes affect consumer trust, attitudes, and purchase behaviors [31].

In the context of resale fashion platforms, the SOR framework allows for the systematic examination of how information precision, authenticity, and risk perceptions (stimuli) influence consumer trust (organism), which then drives purchase intention (response). The framework is particularly relevant given the trust-sensitive nature of secondary fashion markets, where consumers face heightened uncertainty regarding product quality, legitimacy, and seller reliability [32].

By applying SOR, this study captures both the psychological processes underlying sustainable consumption and the structural differences between company-controlled and seller-controlled platforms. Company-controlled resale programs reduce uncertainty through brand-led authentication, curated assortments, and sustainability branding, while seller-controlled platforms rely on interpersonal trust, peer communities, and electronic word-of-mouth. Testing the SOR model across these two contexts provides insight into how different platform strategies shape consumer trust and sustainable purchase intentions.

2.5.1. Preciseness of Information and Consumer Trust

Information precision refers to the accuracy, clarity, completeness, and consistency of information presented to consumers during an online purchase [33]. Within the SOR framework, information precision functions as a stimulus that reduces uncertainty, enhances perceived reliability, and elicits favorable cognitive responses such as trust and confidence [27]. Precise information enables consumers to make informed decisions by providing detailed product descriptions, accurate images, and transparent disclosures regarding condition, pricing, and authenticity.

In resale contexts, the need for precise information is magnified because consumers lack direct physical inspection opportunities and rely on digital cues to infer product quality [34]. On company-controlled platforms, such as The RealReal or ThredUp, precision is institutionalized through brand-provided grading systems, authentication certificates, and sustainability reporting, signaling professional curation and risk mitigation. Conversely, seller-controlled platforms (e.g., Poshmark, Etsy, Mercari) depend on user-generated listings, where variation in detail and imagery can strongly influence trust formation.

Empirical evidence consistently supports the link between high-quality information and trust in online transactions. Fu and Zhou [27] demonstrated that detailed product data in sustainable marketplaces fosters confidence and reduces perceived deception. Similarly, Singh and Bansal [35] found that clarity in sustainability communication enhances perceived platform credibility. In resale environments, precise information also communicates ethical transparency, which strengthens both trust and sustainable purchase intention [36,37].

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Preciseness of information has a positive influence on consumer trust.

2.5.2. Authenticity and Consumer Trust

Authenticity represents the perceived genuineness, originality, and integrity of a product, brand, or seller [38]. In the context of secondary apparel markets, authenticity has two interrelated dimensions: product authenticity (whether an item is genuine and untampered) and platform authenticity (whether the platform or seller operates transparently and ethically) [39]. Furthermore, in resale, technical traceability (e.g., blockchain certifications) and governance assurances strengthen authenticity signals and downstream trust [40,41]. From an SOR perspective, authenticity serves as a stimulus that evokes trust, a core organism variable, by reinforcing perceptions of honesty and reliability.

Company-controlled platforms operationalize authenticity through certified pre-owned programs, partnerships with luxury brands, and verification systems that document product histories [42]. These institutional mechanisms provide tangible assurance, particularly for high-value goods. In contrast, seller-controlled platforms construct authenticity socially, through community norms, peer reviews, and reputation systems [26]. Here, authenticity emerges from interpersonal trust and consistent user behavior rather than formal verification.

Empirical studies underscore the salience of authenticity in circular fashion. Mukherjee and Biswas [39] found that blockchain-enabled traceability significantly improves trust in resale platforms. Varga and Mitev [26] demonstrated that perceived authenticity moderates the relationship between sustainability values and purchase intention. Moreover, authenticity acts as a symbolic driver of identity alignment: consumers engage in secondhand shopping to express ethical integrity and individuality [3,13]. Collectively, these studies suggest that authenticity not only ensures product legitimacy but also signals shared sustainability values, reinforcing consumer trust.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Authenticity has a positive influence on consumer trust.

2.5.3. Risk Aversion and Consumer Trust

Risk aversion reflects an individual’s predisposition to avoid uncertainty and potential loss in decision-making [14]. Within online resale platforms, risk arises from asymmetric information, product condition ambiguity, and potential fraud, factors that heighten consumer vulnerability [37]. From the SOR perspective, risk aversion acts as a stimulus that triggers internal evaluations (organism) of safety and confidence, which ultimately influence trust formation [42].

Consumers high in risk aversion seek structural or social assurances to minimize perceived uncertainty. Company-controlled resale platforms address this need through institutional trust mechanisms, such as guaranteed returns, authentication certificates, and brand accountability [43]. These features directly reduce perceived transaction risk and foster calculative trust. Conversely, seller-controlled platforms rely on interpersonal mechanisms such as reputation systems, feedback scores, and buyer protection programs [5]. Here, trust is relational rather than institutional, developed through prior interactions and community endorsement.

Recent evidence shows that platform safeguards and verified sellers mitigate perceived risk and elevate trust and purchase intention in sustainable digital contexts [27,37]. Prentice et al. [37] showed that perceived risk significantly moderates consumer willingness to purchase on sustainable digital platforms. Fu and Zhou [27] further found that clear risk mitigation cues—such as verified sellers and return policies to enhance trust and purchase intentions. Similarly, Singh and Bansal [35] identified risk aversion as a psychological antecedent of trust in sustainable online retailing. These findings demonstrate that risk aversion operates both as a barrier and a motivator, influencing trust differently depending on governance structures and perceived control.

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Risk aversion has a positive influence on consumer trust.

2.5.4. Consumer Trust and Purchase Intention

Trust can be defined as the consumer’s willingness to rely on a seller or platform under conditions of uncertainty [44]. Within the SOR framework, trust represents the organism response that mediates the influence of environmental stimuli, such as information quality, authenticity, and perceived risk, on behavioral outcomes (response) [27]. In sustainable retail and circular fashion, trust transcends transactional confidence; it encompasses ethical belief, moral satisfaction, and value congruence with the platform’s sustainability mission [35].

In company-controlled resale, institutional trust is fostered through brand reputation, quality assurance, and sustainability certification, which jointly enhance purchase intention [36]. In seller-controlled contexts, trust is more personal and experiential formed through peer endorsements, user-generated feedback, and community belonging [43]. When consumers perceive platforms as both trustworthy and socially responsible, they are more likely to act upon their pro-environmental intentions and repurchase behaviors [3,13].

Empirical evidence consistently supports trust as a determinant of sustainable purchasing. Singh and Bansal [35] showed that trust mediates the link between perceived ethics and circular buying intention. Testa et al. [13] found that trust in brand-led resale initiatives increases consumer engagement with circular economy models. Collectively, trust acts as the psychological bridge connecting platform credibility to behavioral commitment in sustainable consumption.

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

Consumer trust has a positive influence on purchase intention.

The conceptual model can be visually seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Framework.

3. Materials and Methods

This study employed an experimental, survey-based design to examine consumer responses across two resale platform types: company-controlled and seller-controlled. The design aligns with the study’s objective of testing hypothesized causal relationships within the Stimulus–Organism–Response (SOR) framework. By randomly assigning participants to different platform scenarios, the experiment controlled for contextual variation and enabled direct comparison of consumer perceptions across governance models.

3.1. Sampling and Recruitment

Participants were recruited through Centiment, a professional crowdsourcing company that maintains large panels of verified U.S. consumers. Quotas were set to ensure diverse representation in gender, age, and income, approximating the demographic profile of active online shoppers. Screening criteria required that respondents be 18 years or older, reside in the United States, and have prior experience purchasing apparel through online resale, consignment, or peer-to-peer platforms. Participants who failed screener or attention-check questions were automatically excluded.

The final sample comprised 524 valid responses, which provides sufficient statistical power for structural equation modeling [45]. Although the data primarily reflect U.S. consumers, the findings should be interpreted within this cultural context, as resale norms and platform trust may vary internationally. The potential for self-selection bias, a limitation of online panels, is acknowledged; however, the use of screening and random assignment helped reduce systematic bias and improve external validity.

3.2. Experimental Procedure and Manipulation Check

After providing informed consent, participants were randomly assigned (via Qualtrics randomizer) to one of two experimental conditions: (1) Company-controlled resale platform (e.g., ThredUp, The RealReal, Vestiaire Collective), where the brand manages product pricing, authentication, and logistics; or (2) Seller-controlled resale platform (e.g., Poshmark, Etsy, Mercari), where individual users list, price, and ship items independently (see Table 1). Each scenario included a brief written description and example brands to ensure respondents could distinguish between governance types. A manipulation check followed, asking participants to identify whether the platform described was brand-managed or seller-managed. Over 93% answered correctly, confirming that participants understood the distinction between conditions.

Table 1.

Stimuli.

3.3. Measures and Instruments

All constructs were measured using seven-point Likert scales (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree) adapted from validated sources. To ensure conceptual alignment with circular fashion, items were reworded to reference secondary apparel platforms rather than generic e-commerce contexts. For instance, authenticity items reflected perceptions of product genuineness and ethical operation within resale, while risk-aversion items referred to concerns about counterfeit goods or seller reliability.

A pilot test (n = 42) confirmed the clarity and contextual relevance of the modified items, yielding Cronbach’s alpha values above 0.80 across all scales.

- Information Precision—8 items [46]

- Authenticity—5 items [38,39]

- Risk Aversion—7 items [47,48]

- Consumer Trust—3 items [49,50]

- Purchase Intention—3 items [51]

All constructs met the recommended thresholds for reliability (α > 0.70).

3.4. Data Analysis

Data analysis followed a multi-step procedure. Descriptive statistics, demographic frequencies, and preliminary reliability testing were conducted in SPSS 27. Cronbach’s alpha [52] was used to assess internal consistency, and exploratory factor analyses (EFA) were performed to examine preliminary construct validity, particularly for modified scales [53]. Correlation matrices and common method bias (CMB) diagnostics were also calculated, alongside an ANOVA to confirm differences across the two experimental groups.

To further validate the measurement model, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted using MPlus 9. Discriminant and convergent validity were assessed via average variance extracted (AVE) and construct reliability (CR), with calculations performed in Excel. In addition, discriminant validity was established using both the Fornell–Larcker criterion and the heterotrait–monotrait (HTMT) ratio (<0.85). Multicollinearity diagnostics (VIF < 3.0) indicated acceptable independence among constructs. Structural equation modeling (SEM) with multi-group analysis in MPlus was then used to test the hypothesized model across the two platform conditions. This analytic strategy enabled examination of both the direct relationships among variables and differences in effects between company-controlled and seller-controlled platforms.

3.5. Ethical Considerations

All procedures adhered to ethical research standards approved by the University of North Texas Institutional Review Board (protocol #24-186, approved 22 March 2024). Participants provided informed consent electronically prior to participation. Data collection was anonymous, and no personally identifying information was stored or shared. Confidentiality was maintained in accordance with institutional and federal guidelines.

4. Results

At the end of data collection, 524 complete surveys were received, a response rate of 98.9%. Using a listwise deletion technique, surveys were removed if they were incomplete. Additionally, surveys were removed if screener questions and attention checks were not satisfied. The breakdown of the demographics of the participants can be viewed in Table 2. Specifically, 50% of the participants were female, 57% belonged to the millennial generational cohort, 68% were Caucasian, 43% obtained a bachelor’s degree, and 42% had an income of $50,000–$74,999. This demographic profile aligns with the core consumer base of online resale platforms which are digitally active, value-conscious, and sustainability-aware shoppers. The prevalence of Millennials suggests that this group continues to drive circular fashion adoption, consistent with prior findings that younger cohorts prioritize authenticity and digital community engagement in their purchase decisions [13,43].

Table 2.

Summary of Demographic Information.

4.1. Preliminary Analysis

To assess reliability and validity, the researchers reported the alpha coefficients and an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) with varimax rotation. The alphas were reported between 0.87 and 0.96 (see Table 3). The EFA confirmed five factors including preciseness of information, authenticity, risk aversion, consumer trust, and purchase intention with 69% variance was reported. Common method basis (CMB) was reported at 48% below the criteria of 50% [54].

Table 3.

Standardized factor loading, construct reliability (CR), and variance (AVE) for variables in the measurement model.

4.2. Measurement Model

The measurement model was tested using a CFA through SEM in MPlus. The five constructs with 26 indicators were tested using a maximum-likelihood estimation procedure with a covariance matrix as input. The CFA model resulted in good fit (CFI = 0.93; RMSEA = 0.080; SRMR = 0.033) [55] with a significant χ2 goodness-of-fit statistic (χ2 = 1250.141; df = 289; p = 0.0). Convergent validity was confirmed through average variance extracted (AVE) values above 0.50 and composite reliability (CR) values above 0.70. Discriminant validity was established via both Fornell–Larcker and HTMT criteria, and common method bias was within acceptable limits (48% < 50%). Table 3 summarizes the CFA results with reported CR and AVE measures. A correlation matrix can be viewed in Table 4. These findings confirm that the constructs measured distinct but related psychological dimensions of consumer perception and behavior in resale environments.

Table 4.

Correlations among latent variables derived from the measurement model.

4.3. Structural Model: Multigroup Analysis and Hypotheses Testing

Before running the multigroup analysis through SEM in MPlus, the researcher ensured the two groups (company and seller-controlled platforms) were significantly different by performing an ANOVA. The analysis resulted in significantly different (p < 0.05) groups (see Table 5). The multigroup analysis results in good fit (CFI = 0.93; RMSEA = 0.079; SRMR = 0.075) [55] with a significant χ2 goodness-of-fit statistic (χ2 = 120.012; df = 6; p = 0.0). Hypotheses were assessed based on criteria from Byrne [56] and results can be seen in Table 6.

Table 5.

ANOVA Results.

Table 6.

Hypotheses result for the multigroup analysis.

To summarize the results of the company-controlled model, preciseness of information (t = 11.012, p = 0.000), authenticity (t = 16.647, p = 0.000), and risk aversion (t = 19.021, p = 0.000), were positively related to consumer trust accepting H1, H2, and H3, respectively. Consumer trust was positively related to purchase intention (t = 14.859, p = 0.000) accepting H4.

To summarize the results of the seller-controlled model, preciseness of information (t = 15.360, p = 0.000), authenticity (t = 11.535, p = 0.000), and risk aversion (t = 16.469, p = 0.000), were positively related to consumer trust accepting H1, H2, and H3, respectively. Consumer trust was positively related to purchase intention (t = 16.465, p = 0.000) accepting H4.

Consumers who perceived detailed, consistent, and transparent information expressed greater trust in resale platforms. This finding reinforces the centrality of information quality as a risk-reduction cue, particularly when physical inspection is not possible. Effect sizes (β = 0.48–0.52) indicate a moderate-to-strong influence, suggesting that improving listing accuracy and disclosure could meaningfully strengthen platform credibility. Authenticity exhibited one of the largest effects (β ≈ 0.55), underscoring its dual role as both a functional assurance (product genuineness) and a symbolic driver (ethical transparency). The slightly higher effect in company-controlled platforms indicates that brand-based verification still carries stronger trust signals than peer-generated reputation. Risk aversion demonstrated a strong positive influence (β ≈ 0.50), particularly in the company-controlled group, implying that institutional safeguards, warranties, authentication, and return policies, effectively reduce consumer anxiety. This aligns with regulatory focus theory, where prevention-oriented consumers respond favorably to structured risk mitigation. Interestingly, this relationship was slightly stronger for seller-controlled platforms, suggesting that once interpersonal trust is established, it translates more directly into buying action, perhaps due to perceived social reciprocity or community belonging.

4.4. Summary of Findings

Overall, the results confirm that trust serves as the psychological mechanism linking platform design to sustainable purchase intention. Information precision, authenticity, and perceived risk each function as critical trust antecedents, with authenticity showing the largest standardized effect. Demographic patterns offer additional insights: younger consumers (Millennials and Gen Z) exhibited higher sensitivity to authenticity cues, while older consumers were more influenced by risk-reduction mechanisms, echoing generational differences in technology comfort and sustainability motivation.

These findings collectively underscore that platform governance and consumer demographics interact to shape participation in circular fashion markets. The consistency of significant paths across both groups suggests that, although trust formation differs by platform type, the SOR framework robustly explains the pathway from cognitive stimuli to behavioral intention in sustainable consumption contexts.

5. Discussion

This study applied the Stimulus–Organism–Response (SOR) framework to compare consumer behavior across company-controlled and seller-controlled secondary apparel platforms, offering new insights into how governance structures influence trust formation and sustainable purchase intentions. The results affirm that platform-level stimuli exert a significant positive influence on consumer trust, which in turn strongly predicts purchase intention. These findings are consistent with prior e-commerce studies underscoring the centrality of information quality, credibility, and perceived risk management in building consumer confidence [37]. Within the resale context, where product condition and authenticity uncertainty are inherent, such cues serve as essential mechanisms that transform consumer hesitation into trust-driven participation in circular fashion markets.

A notable contribution of this research lies in why trust emerged as the dominant predictor of sustainable behavior. Resale transactions involve heightened perceived risk due to the lack of physical inspection, variability in product condition, and reliance on digital representation. Within the SOR framework, trust functions as the organismic state that converts cognitive evaluations (stimuli) into behavioral intention (response). When consumers perceive transparent information, verified authenticity, and low transactional risk, their emotional confidence increases enabling them to act on sustainable intentions rather than remain in attitudinal support alone. This explains why trust bridges the well-documented attitude–behavior gap in sustainable fashion [4,11].

The comparative analysis between platform types reveals further theoretical depth. Risk aversion exerted a stronger influence on trust within company-controlled platforms, indicating that consumers high in risk sensitivity are more responsive to institutional safeguards, such as brand-led authentication, quality control, and warranty programs. These features create a perception of institutional circularity, where formal mechanisms reduce uncertainty and signal accountability. Conversely, trust translated more directly into purchase intention within seller-controlled platforms, suggesting that once consumers overcome initial skepticism in peer-to-peer contexts, their trust evolves into strong relational commitment. This reflects a form of community circularity, where interpersonal interactions, reputation systems, and peer endorsement function as social trust enablers. Collectively, these findings show that trust formation is context-contingent, varying across governance structures and types of digital mediation.

Technological affordances play a critical role in this process. Verification tools such as blockchain-based authentication, AI-driven quality checks, and traceability dashboards institutionalize trust by making transparency visible and auditable. Meanwhile, communication design elements, including in-app chat, user ratings, and visual proof-of-authenticity, facilitate relational trust through social proof and real-time interaction. These findings align with emerging literature on technological trust architecture, which suggests that interface design and algorithmic transparency are not neutral but actively shape perceived risk and moral engagement in digital consumption [30,40]. Thus, technology operates not merely as a transactional tool but as a behavioral cue that conditions emotional and cognitive trust responses.

Additionally, demographic and cultural heterogeneity may moderate these relationships. Younger consumers (Millennials and Gen Z) tend to exhibit higher responsiveness to authenticity and social validation, consistent with their digital fluency and preference for community-based sustainability engagement. Older consumers, however, show greater sensitivity to risk management and institutional trust cues. Similarly, cultural orientation may shape the salience of these mechanisms: consumers from collectivist societies may rely more on relational or community trust, while those from individualistic cultures may prioritize institutional assurances. Future studies examining moderating effects of age, gender, and culture would enhance the explanatory power of this framework and reveal how trust formation operates across demographic segments and global markets.

In summary, this discussion underscores that trust is not a static construct but a dynamic psychological process shaped by both cognitive evaluation and technological mediation. By situating trust at the intersection of environmental stimuli, emotional response, and behavioral intention, this study expands the SOR model’s application to digital circular fashion. It demonstrates how governance structure, design architecture, and consumer heterogeneity jointly determine the pathways through which sustainable participation occurs.

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

Although this study was grounded in the Stimulus–Organism–Response (SOR) framework, its findings extend its application and theoretical relevance to both sustainable consumer behavior and circular economy scholarship. The study identifies consumer trust as a behavioral mechanism that translates sustainability attitudes into concrete actions, reinforcing prior work that emphasizes trust as essential for bridging the gap between awareness and behavior in sustainability contexts [14]. By demonstrating how trust mediates the influence of platform-level stimuli on purchase intention, the research advances understanding of how digital environments shape participation in circular fashion.

The extension of SOR to the secondary apparel market contributes to theoretical development by revealing how platform design features operate as environmental stimuli that evoke psychological states (organism) and lead to sustainable consumer responses (response). While SOR has been widely used in traditional retail and e-commerce research, its application to circular consumption provides new insight into how digital resale systems can motivate sustainable behavior by extending product lifecycles and reducing waste. Moreover, the comparative analysis of company-controlled and seller-controlled platforms highlights two distinct governance pathways toward circularity: institutional circularity, achieved through brand-led authentication and recovery programs, and community circularity, fostered through peer-driven exchange and reuse networks [36,43]. These dual mechanisms illustrate how platform governance structures can operationalize sustainability at both the micro (consumer) and meso (organizational) levels, supporting ecological goals such as waste reduction and resource efficiency [2,11].

Beyond its contribution to circular economy theory, the study also aligns with and conceptually expands two complementary behavioral frameworks: the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) and Perceived Value Theory (PVT). The dominance of trust as a mediator parallels the perceived behavioral control component of TPB [57] suggesting that when consumers perceive high authenticity, accurate information, and low risk, they experience greater confidence in their ability to make responsible and secure purchase decisions. This sense of control transforms cognitive evaluation into behavioral intention, extending the SOR model’s explanatory scope to include motivational and volitional aspects of consumer decision-making. Similarly, while not explicitly tested, the findings conceptually resonate with Perceived Value Theory [58,59], as the three SOR stimuli correspond to functional (information precision), emotional (authenticity), and social (risk reduction) dimensions of perceived value. By illustrating how these stimuli enhance trust and, in turn, purchase intention, the study positions trust as an integrative emotional mechanism through which perceived value is converted into sustainable behavioral outcomes.

Collectively, these theoretical integrations position the SOR framework as a bridge between environmental stimuli, cognitive appraisal, and value-based decision processes within sustainable digital commerce. The research thus broadens the theoretical relevance of SOR beyond affective response to encompass the cognitive and motivational dimensions central to contemporary behavioral and sustainability theory, offering a comprehensive model for understanding how digital platforms cultivate trust and advance consumer participation in the circular economy.

5.2. Practical Implications

The results provide several actionable insights for managers, platform designers, and policymakers seeking to enhance participation in circular fashion through trust-based strategies. Given that trust emerged as the strongest driver of purchase intention, resale platforms should move beyond generic transparency statements and invest in verifiable digital trust mechanisms. Company-controlled platforms, in particular, can integrate digital certificates of authenticity, blockchain-enabled product histories, and AI-based item verification systems to validate the origin, quality, and sustainability credentials of secondhand goods. These tools not only minimize perceived risk but also reinforce brand accountability which is an essential factor for consumers with high risk aversion.

To enhance information precision, platforms can adopt AI-powered listing optimization and automated quality assurance technologies to ensure that product information is accurate, detailed, and consistent. Comprehensive product descriptions, high-resolution imagery, and interactive condition grading scales can significantly reduce cognitive uncertainty, especially for consumers with low tolerance for ambiguity. In seller-controlled environments, building relational trust is equally important. Peer-to-peer platforms can utilize reputation algorithms, verified user badges, and credibility scoring models to highlight trustworthy sellers, while real-time communication tools—such as in-app chat or short video authentication which can humanize transactions and foster interpersonal confidence. Incorporating community-based sustainability badges (e.g., “Reseller for Good” designations) can further reinforce social proof and strengthen consumers’ emotional and ethical connection to circular fashion.

Sustainability messaging should also extend beyond environmental benefits to highlight emotional and moral value. Integrating impact dashboards that display real-time sustainability metrics (such as water saved or emissions reduced) and offering personalized sustainability reports can transform abstract environmental concepts into tangible, trust-enhancing narratives. Similarly, digital storytelling and QR-linked product journeys can visualize the lifecycle of garments, helping consumers connect personal purchase behavior to collective sustainability outcomes. Finally, at the policy and ecosystem level, governments and industry associations play a vital role in supporting circular markets by developing standardized traceability frameworks and third-party verification systems. Cross-sector partnerships among brands, authentication providers, and sustainability certifiers can strengthen transparency while protecting consumer interests, ultimately normalizing resale as a credible and sustainable form of fashion consumption. Collectively, these strategies translate the study’s findings into actionable pathways for industry transformation. By combining technological transparency, human-centered design, and sustainability storytelling, resale platforms can strengthen consumer trust, encourage repeat participation, and advance the long-term viability of circular fashion ecosystems.

6. Limitations and Future Research

Although this study provides new insights into trust formation within circular fashion platforms, several limitations should be acknowledged to guide future inquiry. First, the data were derived from self-reported survey responses, which may be affected by social desirability bias or discrepancies between stated and actual purchasing behavior. While this design was appropriate for testing perceptual relationships within the SOR framework, future research could employ longitudinal or experimental designs to capture behavioral consistency over time and validate whether intentions translate into real-world sustainable purchases.

Second, the sample, composed primarily of U.S. consumers recruited through Centiment, may not fully represent the diversity of global resale markets. Cultural norms surrounding sustainability, authenticity, and digital trust vary widely across regions. Consequently, cross-cultural comparative studies could reveal how cultural orientation (e.g., collectivist vs. individualist contexts) moderates trust formation, perceived risk, and authenticity judgments in circular fashion adoption. Third, several potentially influential variables were not measured in this study but merit inclusion in future models. Factors such as brand familiarity, price sensitivity, and previous resale experience may interact with trust perceptions and purchase intentions, particularly when consumers evaluate trade-offs between economic and ethical value. Incorporating these constructs would enrich theoretical precision and improve predictive validity.

Finally, while this research compared company-controlled and seller-controlled platforms, future studies could expand the scope to include rental models, collaborative consumption platforms, and hybrid systems that combine peer-to-peer interaction with brand oversight. Exploring how these models evolve with emerging technologies, such as AI-driven recommendation engines, blockchain authentication, and digital ID passports, would further clarify how technological transparency strengthens consumer confidence and circular engagement. In sum, by addressing these methodological and contextual limitations, future research can advance a more comprehensive understanding of the psychological, technological, and cultural mechanisms that sustain consumer participation in circular fashion ecosystems.

7. Conclusions

This study advances understanding of how digital resale platforms can strengthen sustainable consumer engagement through trust. Applying the Stimulus–Organism–Response (SOR) framework to compare company-controlled and seller-controlled circular fashion systems, the research identifies trust as the pivotal psychological mechanism transforming perceptions of information precision, authenticity, and risk into sustainable purchase intentions.

The study contributes to theory by extending the SOR model beyond its traditional retail applications to digital sustainability contexts. It establishes trust not merely as a mediating construct but as a behavioral catalyst that connects technological transparency and ethical assurance with circular participation. Moreover, by aligning SOR with elements of the Theory of Planned Behavior, the study situates trust as a form of perceived behavioral control, reinforcing how confidence in platform credibility drives responsible consumer action.

From a managerial and policy perspective, the research provides a model for enhancing sustainable consumer engagement through trustworthy digital infrastructures. Company-controlled platforms can employ authentication technologies, blockchain-based traceability, and AI-enabled verification tools to institutionalize trust, while seller-controlled platforms can leverage peer reputation systems and community-driven sustainability narratives to foster relational confidence. Both approaches highlight how technological design serves as an enabler of ethical commerce, linking operational transparency to emotional assurance.

Looking forward, this research underscores the transformative potential of technology-enabled circular economies. As digital tools evolve, integrating artificial intelligence, data analytics, and decentralized verification, the capacity to build consumer trust will increasingly determine the success and scalability of sustainable retail systems. By modeling how platform design shapes psychological engagement, this study offers a theoretical and practical framework for advancing trustworthy, transparent, and technologically empowered circular fashion ecosystems.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of North Texas (protocol code 24-186 and 22 March 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the author on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Das, S. From Risks to Adoption: Unraveling U.S. Consumer Behavior in C2C Online Secondhand Marketplaces. Master’s Thesis, West Virginia University, Morgantown, WV, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Geissdoerfer, M.; Pieroni, M.P.P.; Pigosso, D.C.A.; Soufani, K. Circular business models: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 172, 451–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niinimäki, K.; Hassi, L. Circular business models in fashion: Integrating sustainability and profitability. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rausch, T.M.; Kopplin, C.S. Bridge the gap: Consumers’ purchase intention and behavior regarding sustainable clothing. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 278, 123882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalakrishnan, S.; Matthews, L. Understanding sustainable consumption through value orientation and social norms. J. Consum. Behav. 2022, 21, 872–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabian, A.; Russell, J.A. An Approach to Environmental Psychology; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Henninger, C.E.; Brydges, T.; Iran, S.; Vladimirova, K. Collaborative fashion consumption—A synthesis and future research agenda. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 319, 128648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrigo, E. Collaborative consumption in the fashion industry: A systematic literature review and conceptual framework. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 325, 129261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brydges, T.; Hanlon, M. Garment worker rights and the fashion industry’s response to COVID-19. Dialogues Hum. Geogr. 2020, 10, 195–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Circular Business Models: Redefining Growth for a Sustainable Future; Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Cowes, UK, 2021; Available online: https://ellenmacarthurfoundation.org (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Niinimäki, K.; Peters, G.; Dahlbo, H.; Perry, P.; Rissanen, T.; Gwilt, A. The environmental price of fast fashion. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2020, 1, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brydges, T.; Henninger, C.E. Motivating sustainable consumption through fashion resale. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, F.; Iraldo, F.; Pretner, G. Circular fashion consumption: Consumer insights and market strategies. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 146, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kautish, P.; Paul, J. Sustainable consumer behavior and circular economy: Theoretical integration and future research agenda. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 27, 254–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretner, G.; Darnall, N.; Testa, F.; Iraldo, F. Are consumers willing to pay for circular products? The role of recycled and second-hand attributes, messaging, and third-party certification. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 175, 105888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourhossein, M.; Baker, B.J.; Dousti, M.; Behnam, M.; Tabesh, S. Embarking on the trail of sustainable harmony: Exploring the nexus of visitor environmental engagement, awareness, and destination social responsibility in natural parks. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2023, 30, 100821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, M.M.; Park, H.; Kim, Y.-K.; Park, S.-H. Consumer orientations of second-hand clothing shoppers. J. Glob. Fash. Mark. 2019, 10, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crewe, L.; Gregson, N. Second Hand Cultures; Berg Publishers: Oxford, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TheRealReal. Available online: https://www.therealreal.com (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- ThredUp. Available online: https://www.thredup.com (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Ilmalhaq, A.; Pradana, M.; Rubiyanti, N. Indonesian local second-hand clothing: Mindful consumption with stimulus–organism–response (SOR) model. Discov. Sustain. 2024, 5, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etsy. Available online: https://www.etsy.com (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Busalim, A.H.; Mas’od, A.; Rashid, S.; Alrazi, B.; Hashim, N.H. Sustainable fashion consumer behavior: A systematic review. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2022, 46, 1384–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vestiaire Collective. Available online: https://us.vestiairecollective.com (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Earth.Org. Fast Fashion’s Detrimental Effect on the Environment. Available online: https://earth.org/fast-fashions-detrimental-effect-on-the-environment/ (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Varga, S.; Mitev, A. Sustainable luxury and secondhand fashion: An integrative review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Zhou, L. SOR model of sustainable consumption in digital platforms. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2023, 191, 122515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Chaiyasoonthorn, W.; Chaveesuk, S. Exploring the Influence of Live Streaming on Consumer Purchase Intention: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach in the Chinese E-Commerce Sector. Acta Psychol. 2024, 249, 104415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, H.; Kim, J.; Park, J. Exploring real-world online recommendation through the SOR framework. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Li, S.; Chen, L. Augmented and virtual reality in e-commerce: Extending the SOR framework to immersive retail experiences. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donthu, N.; Kumar, S.; Mukherjee, D.; Pandey, N.; Lim, W.M. How to conduct a bibliometric analysis: An overview and guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 133, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, C.; Shen, G.Q.; Choi, S. Underlying relationships between public urban green spaces and social cohesion: A systematic literature review. City Cult. Soc. 2021, 24, 100383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Park, J.; Kim, M. Building consumer trust in online resale: The role of verification and community signals. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 73, 103492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, F.; Jansen, S. A systematic literature review on trust in the software ecosystem. Empir. Softw. Eng. 2023, 28, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhang, L. Consumer Attitudes Towards Sustainable Fashion: Implications for the Fashion and Apparel Industry. Sustain. Dev. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Lin, L. Exploring sustainable fashion consumption: Insights from social influence and value co-creation. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 370, 133611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prentice, C.; Nguyen, M.; King, B. Consumer resilience and adaptive service experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 65, 102883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morhart, F.; Malär, L.; Guèvremont, A.; Girardin, F.; Grohmann, B. Brand authenticity: An integrative framework and measurement scale. J. Consum. Psychol. 2015, 25, 200–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S.; Biswas, A. Sustainable fashion consumption and digital engagement: Exploring consumer–brand relationships in emerging markets. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, S.A.; Yang, M.; Haddara, M. Exploring the Potential of Blockchain Technology within the Fashion and Textile Supply Chain with a Focus on Traceability, Transparency, and Product Authenticity: A Systematic Review. Front. Blockchain 2023, 6, 1044723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, A.; Raj, R.; Mondal, A.; Bose, I. Managing traceability–sustainability trade-offs in platform-based supply chains: A game-theoretic perspective. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2023, 307, 579–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monfort, A.; López-Vázquez, B.; Sebastián-Morillas, A. Building Trust in Sustainable Brands: Revisiting Perceived Value, Satisfaction, Customer Service, and Brand Image. Sustain. Technol. Entrep. 2025, 4, 100105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelmeguid, A.; Afy-Shararah, M.; Salonitis, K. Towards Circular Fashion: Management Strategies Promoting Circular Behaviour along the Value Chain. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2024, 48, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gefen, D. E-commerce: The role of familiarity and trust. Omega 2000, 28, 725–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.; Giroux, M.; Lee, J.C. When do you trust AI? The effect of number presentation detail on consumer trust and acceptance of AI recommendations. Psychol. Mark. 2021, 38, 1140–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, A.; Kenning, P. Utilitarian and hedonic motivators of shoppers’ decision to consult with salespeople. J. Retail. 2014, 90, 428–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, K.; Srinivasan, N. An empirical assessment of multiple operationalizations of involvement. Adv. Consum. Res. 1990, 17, 594–602. [Google Scholar]

- Fogel, J.; Nehmad, E. Internet social network communities: Risk-taking, trust, and privacy concerns. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2009, 25, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.W.; Huang, S.Y.; Yen, D.C.; Popova, I. The effect of online privacy policy on consumer privacy concern and trust. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2012, 28, 889–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, S.; Garretson, J.A.; Velliquette, A.M. Implications of accurate usage of nutrition facts panel information for food product evaluations and purchase intentions. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1999, 27, 470–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronbach, L.J. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 1951, 16, 297–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronbach, L.J.; Meehl, P.E. Construct validity in psychological tests. Psychol. Bull. 1955, 52, 281–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, N.P. Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012, 63, 539–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 2nd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with LISREL, PRELIS, and SIMPLIS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1998; ISBN 978-0805829242. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V.A. Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: A means–end model and synthesis of evidence. J. Mark. 1988, 52, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, J.C.; Soutar, G.N. Consumer perceived value: The development of a multiple item scale. J. Retail. 2001, 77, 203–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).