Abstract

Electrical outfitting is sometimes overlooked despite its significant impact on build efficiency and vessel performance. It typically occurs towards the end of a ship’s construction. An organized and traceable method for organizing, carrying out, and verifying electrical installation operations is presented in this paper as the Generalized Electrical Outfitting Traceability Management (GEOTM) model. Data on labor utilization, cable routing methods, and cold insulation records were meticulously analyzed when the model was applied to a real-world setting—a 10,000 DWT chemical tanker project. Using organized from-to routing sheets, thoroughly documenting all connections and tests, and integrating electrical components early on during block assembly were all given special attention. This led to a 7.9% reduction in cable waste, less rework, and better timeline compliance, all of which were supported by GEOTM. The early and planned integration of electrical work, which made up a smaller fraction of the total labor, greatly improved build quality and schedule consistency. Beyond the scope of this particular case study, the results indicate that shipyards could benefit from adopting more sustainable, lean, and predictable building techniques by utilizing a digitally backed, traceable model such as GEOTM.

1. Introduction

As ships become smarter, electrical systems become more and more important. These systems include not only power supply but also automation, digital control, and onboard intelligence. One of the most important but frequently overlooked parts of contemporary shipbuilding is outfitting, which includes running cables and putting electrical systems together.

In shipbuilding, terms like Shipyard 4.0 and digital twins are often at the center of innovation discussions. These technologies have certainly pushed mechanical outfitting and production monitoring forward—improving automation, reducing human error, and tightening schedules [1,2,3]. However, their influence has been significantly less noticeable in the realm of electrical outfitting. A lot of important details are overlooked, such as maintaining cable versioning, updating terminal records, or reflecting on-the-fly installation changes [4,5,6,7,8].

Even though some researchers have proposed ways to digitally model electrical systems, most of these solutions remain in the design phase. Garcia and Rabadi [9] ad-dressed planning through scheduling models, while Im et al. [10] and Moulianitis et al. [11] explored CAD-based wiring and rule-based cable routing, respectively. Others, such as Chen et al. [12], tried to improve the link between design and implementation using BIM tools. However, they tend to overlook day-to-day yard realities—like un-documented workarounds or shifting cable paths during construction. Concurrently, safety and risk management have also garnered attention. Research conducted by Chang et al. [13] and Huang et al. [14] concentrated on failures and electrical system instabilities, whereas Alanhdi and Toka [15] employed artificial intelligence to optimize resource allocation and forecast delays. Other studies have focused on predicting potential risks [16,17] or uncovering weaknesses in cybersecurity [18]. However, most of these approaches overlook a pressing need within electrical outfitting: the ability to maintain full traceability through version control, audit documentation, and coordination between different stages of work.

This study introduces the GEOTM model as a practical approach developed through real shipyard experience. It does not rely on theory alone but builds on methods that have already proven useful in daily practice, such as routine on-site checks, detailed from-to cable records, and progressive documentation at each stage of work. With this structure, GEOTM connects the design phase with field activities, allowing the entire electrical outfitting process to be tracked clearly and managed in a consistent way.

This paper is organized to correspond with the progression from conceptual development to applied results. The GEOTM model is introduced in Section 2, along with its main features, which are intended to enhance the transparency and coordination of electrical outfitting activities in shipbuilding. Section 3 illustrates the practical application of this model, specifically within a 10,000 DWT chemical tanker project, by employing planning matrices, cable routing records, and cold insulation tracking as essential implementation tools. The results of this deployment are detailed in Section 4, which includes measurable reductions in cable waste, fewer instances of revision, and improved adherence to project timelines. Lastly, Section 5 contemplates the broader implications of these discoveries and delineates how the GEOTM approach could facilitate the implementation of more sustainable, traceable, and efficient practices throughout the shipbuilding sector.

2. Generalized Electrical Outfitting Traceability Management Model

The planning and installation of a ship’s electrical systems prior to its departure from the dock have a considerable influence on its future performance. Power, automation, communication, and control networks all need to work together in real time, almost like parts of a living organism. But when outfitting is carried out step by step using old-style manual coordination, confusion tends to build up, schedules slip, and costs quietly climb.

The progress in shipbuilding technology has made it essential to embrace more structured, digitally supported methodologies. In contrast to traditional sequential production, electrical outfitting necessitates a workflow that integrates each phase and ensures traceability from design to commissioning. GEOTM established in this study offers a cohesive, data-centric framework that integrates planning, installation, testing, and delivery. Originating from hands-on experience in a chemical tanker project, the GEOTM framework demonstrates how theory may be successfully applied to day-to-day shipyard operations by bridging the gap between design and on-site execution.

2.1. GEOTM Process Flow

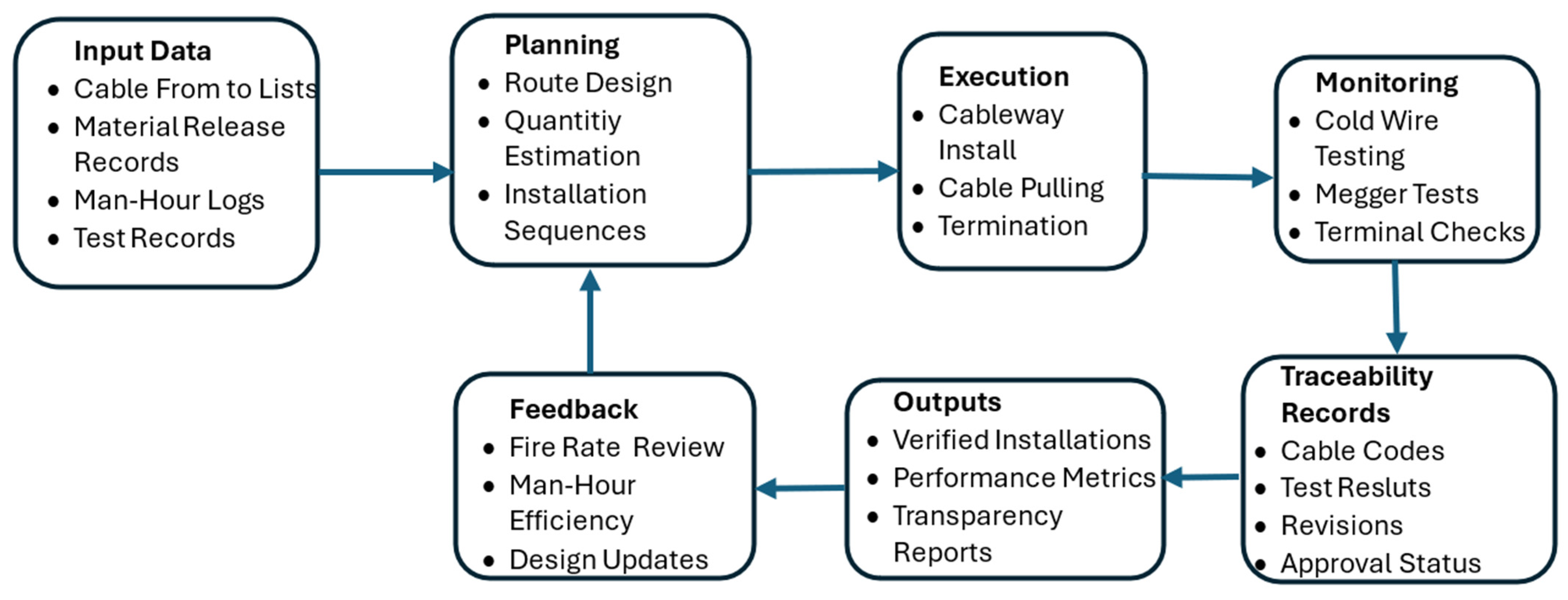

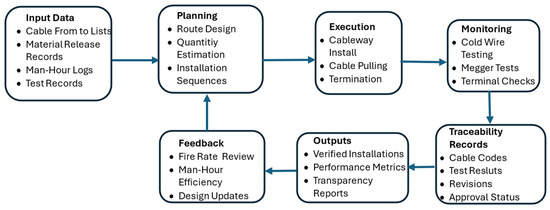

A practical and traceability-focused electrical outfitting management process was formulated using complete lifecycle data from the 10,000 DWT chemical tanker project (see Figure 1). The revised GEOTM process flow connects the design, procurement, production, and testing phases through seven coordinated stages. These include: (1) Input Data, which brings together design information, material release records, man-hour logs, and test documentation; (2) Planning, where route design, quantity estimation, and installation sequencing are carried out; (3) Execution, covering the installation of cableways, cable pulling, and termination tasks; (4) Monitoring, involving cold-wire testing, megger measurements, and terminal inspections; (5) Traceability Records, in which cable codes, test outcomes, revisions, and approval statuses are digitally confirmed; (6) Outputs, summarizing verified installations, performance indicators, and transparency reports; and (7) Feedback, where fire-rate assessments, efficiency reviews, and design improvements are incorporated into future planning. Decision checkpoints—covering design approval, material validation, installation quality, and testing results—are embedded throughout the process to ensure full coordination between design, procurement, and production teams. This closed-loop structure enhances traceability, encourages continuous improvement, and enables data-driven management across the entire electrical outfitting cycle.

Figure 1.

GEOTM process flow diagram.

2.2. Electrical Outfitting in Ships

The organization and shape of a ship’s interior greatly influences how its electrical systems are arranged. Differences in the deck levels, hull design or room layout can change how cables are routed, how easy it is to reach certain areas, and how much material is needed. Wiring routes aboard ships with multiple decks or small compartments are longer and more difficult to reach, necessitating meticulous planning and coordination to ensure a safe and effective installation.

When a ship is under construction, many overlapping factors shape how the electrical outfitting takes place. The most important ones are the ship’s purpose, how complex its systems are, the rules and standards that must be followed, and how well different teams—structural, mechanical, and electrical—work together on site. These aspects set the rhythm of the work, the level of coordination needed, and the overall plan for installation. Other important criteria are the crew’s proficiency, the reliability of suppliers, the timeliness of material delivery, and the clarity of communication across teams during daily operations. All these factors converge to determine the efficiency, safety, and consistency of the electrical installation at the vessel’s completion.

The proportion of electrical systems in the total construction scope varies by vessel type—approximately 30% for passenger ships, 35% for military vessels, 6% for dry cargo ships, and 5–20% for oil and chemical tankers, depending on size. While electrical outfitting appears to require less effort than piping—20,000 compared to 80,000 man-hours for a 10,000 DWT chemical tanker—the use of costly materials, specialized equipment, and skilled labor often raises its share to as much as 60% of the total construction cost.

Unlike most other construction activities, electrical installation takes place in several stages, progressing alongside the mechanical, piping, and structural works. Because these tasks are performed close to the final stages of building, even a brief interruption can easily disrupt the project schedule and delay completion. Electrical systems are also critical to a ship’s safety, navigation, and environmental performance; so, all work must comply with international rules and the requirements of classification societies [19].

The GEOTM model was developed to handle this complexity through organized planning, balanced use of labor, and continuous documentation—from the earliest cableway layout to the final system checks. By maintaining traceability and coordination among disciplines at every stage, the model provides a practical framework that supports safe, high-quality, and regulation-compliant electrical outfitting.

2.2.1. Cableways

Electrical outfitting often starts with setting up the main support components—such as brackets, trays, and mounting frames—that will carry the cables later on. In the GEOTM model, this stage is not handled as a simple installation task but as part of a connected digital traceability system. Material choices, for example galvanized or stainless steel in exposed areas, are made with both durability and compliance in mind, following traceable decision records linked to design rules and class standards.

During the block construction stage, details like bracket locations, welding records, and material certificates are entered into the digital database. This allows for real-time coordination between teams and ensures that supports are installed early, before block assembly begins. Doing so improves access, reduces temporary work, and helps avoid rework later in the project.

The model also follows a Just-in-Time approach for material and labor supply, aligning deliveries and skilled personnel with project milestones. This prevents the typical delays and extra costs seen when support installation is postponed until after block joining. By combining digital planning with field verification, GEOTM turns what was once a routine early step into a controlled, traceable, and transparent process.

2.2.2. Cable Pull Process

Cable pulling is one of the toughest and most detail-oriented stages in electrical outfitting. In the GEOTM model, each cable is planned, installed, tested, and logged through a practical workflow that ties the design plan directly to the work carried out on site and keeps every step traceable over the ship’s lifetime.

On board a vessel, cables serve crucial purposes: they carry electrical power, transmit control signals, and support both communication and emergency systems. Because marine cables must withstand vibration, salt exposure, and electromagnetic interference, their installation requires precise handling and constant supervision. GEOTM meets these needs by combining 3D routing information with a fully traceable “From-To Cable Matrix,” verified through digital checklists and live progress updates.

There are generally three ways to prepare cables: cutting directly from reels using drawings, assembling semi-pre-routed bundles, or applying pre-approved “From-To” lists that specify exact routes and lengths. GEOTM adopts the third option as standard practice and embeds it in the digital workflow. This method cuts down on waste, keeps cable length and weight balance under constant control, and helps maintain accurate inventory records during the work.

Each cable is assigned a unique identification number that allows it to be tracked throughout its entire service life, making future maintenance and refit work easier. The example in Table 1 follows this approach and includes key checkpoints such as technical details, start and end points, and functional test results. Weight is recorded to assist naval architects assess ship stability. MGCH, FRLS, and EPR are industry-standard maritime cable types, not specific to the GEOTM model. MGCH refers to a marine cable built to handle heat, FRLS is a Flame Retardant Low Smoke type used for safety in enclosed areas, and EPR means the cable is insulated with Ethylene Propylene Rubber for flexibility and durability. “Cable Code” (W11, W12, W13) marks each cable with its own ID for tracking during the project, while “Cable Spec” (2 × 1.5, 4 × 2.5, 3 × 6) shows how many wires it contains and the size of each core in square millimeters. In the GEOTM setup, these cables are followed digitally so every step of the installation can be traced and verified according to class standards.

Table 1.

Structured cable pull list under GEOTM model.

Cable pulling is one of the toughest and most detail-oriented stages in electrical outfitting. In the GEOTM model, each cable is planned, installed, tested, and logged through a practical workflow that ties the design plan directly to the work carried out on site and keeps every step traceable over the ship’s lifetime.

2.2.3. Cable Connection Process

Connecting cables might look like a simple job, but in practice it is one of the most critical and high-risk stages of electrical outfitting. In the GEOTM model, this work is carried out through a coordinated and traceable process that keeps every termination accurate, verifies function at each step, and maintains full safety compliance across the ship.

The sequence is always the same: it starts with shore power, continues with generators and emergency systems, and ends with the main distribution panels. Each step must pass strict testing before moving on. One of the biggest mistakes is powering a system too early, before checks are finished. GEOTM prevents this through digital connection sheets, test logs, and terminal tracking. If anything changes on site—like a terminal being reassigned or a piece of equipment moved—it is recorded instantly and reflected in the main design file.

The list shown in Table 2 includes technical details and test data, acting as a long-term digital record for maintenance and system upgrades. “Cable Selection” (3 × 75, 10 × 0.75) indicates the number and size of conductors, “Cable Type” (Mgsco, ffrxcgo) describes insulation and protection features, and “Target Terminal No” (Fp.X2, TI.P X5) identifies the exact points where the cables are installed and tested on board.

Table 2.

Cable connection traceability list.

This connection table is used throughout the commissioning and service phases as an active reference, allowing teams to trace earlier terminations, spot any unauthorized modifications, and verify consistency with the original design. Through this approach, the GEOTM model turns cable connection from a single installation activity into a transparent and collaborative process that directly supports vessel safety, regulatory compliance, and long-term operational reliability.

3. Case Implementation on a 10,000 DWT Chemical Tanker

The electrical outfitting of a 10,000 DWT IMO II chemical tanker was carried out using the GEOTM model, a system developed to manage all electrical work through an integrated, traceable, and digitally coordinated process. Similar to other ship types, the electrical outfitting process of chemical tankers encompasses the same primary phases: establishing cableways, cable pulling, and conducting testing to confirm system integrity. What makes chemical tankers’ process different is the need for explosion-proof systems, tighter safety regulations, and thorough documentation due to the flammable nature of their cargo. These extra precautions make the electrical outfitting process more controlled and strongly focused on safety compared with most other vessels.

To ensure a practical and well-organized electrical outfitting process during the initial design stage of a chemical tanker, it is important to align the electrical layout with the structural model from the very beginning. Setting cable corridors early and applying 3D route planning helps eliminate space clashes and reduces the risk of expensive rework during construction. In this project, the method was put into practice from the start of the block construction phase, beginning with cableway installation in the sections that were easiest to access. This early action reduced congestion in later stages and allowed cable-pulling to begin sooner. Project data indicate that cableway installation took approximately 8430 man-hours, accounting for about 35% of the total electrical workload.

The engineering team created a “from-to” cable list to improve accuracy and make a reduction in material waste. This list included planned routes, starting and ending terminals, and estimated quantities, with the full layout shown in Appendix A. Using this plan, cables like W11, W12, and W13 were installed in a systematic and controlled way. A total of 110 km of cable was pulled, with a wastage rate of 7.9% (8.7 km), which is significantly lower than industry averages due to effective early-stage planning and traceable list control. The cable pulling process necessitated 9655 man-hours, accounting for 40% of the overall electrical labor.

Before the system was energized, all cable ends were checked for insulation and connection accuracy as detailed in the structured cable connection traceability list (Table 2). For instance, cable W11 measured an insulation resistance of 1.5 GΩ (109 ohms), and cable W21 needed a terminal reassignment, which was immediately recorded and updated in the digital design database. The cable connection stage took about 6110 man-hours, making up roughly 25% of the overall electrical work.

Keeping a digital record of every cable’s type, length, route, and test result was a key part of the project. The system allowed the team to track progress as the work happened, manage resources more efficiently, and keep the project on schedule. In total, 24,195 man-hours were recorded and reviewed through the GEOTM platform, enabling ongoing communication and feedback between the design office and the crews on site. Keeping all cable-related work in one traceable system helped reduce errors, improved communication with suppliers, and made it easier to make quick decisions. This structured, digital approach ensured that all electrical outfitting work—from installing supports to final cable connections and commissioning—was completed safely, on time, and within budget.

Safety in the electrical outfitting of chemical tankers is ensured by following international and class standards such as IEC 60092 [20], IEC 60079 [21] for explosion protection, and IMO/IEC/ISO guidelines for hazardous area installations. All cables and equipment are required to be Ex-proof certified and installed in accordance with Bureau Veritas standards. Before the system is powered, insulation resistance, grounding, and terminal checks are carried out under IEC 60364 [22] procedures. In this project, the same main steps as in conventional methods were applied, but the GEOTM model introduced digital integration and full traceability. From material approval to final testing, it provided structured records, real-time tracking, and stage-by-stage verification. Instead of using paper-based control, the GEOTM approach relies on data-driven management, making the process clearer, faster, and more efficient while reducing rework and improving safety oversight.

All phases of the electrical outfitting, from material approval to final testing, were managed and verified through the GEOTM system in compliance with IEC 60092 and Bureau Veritas safety standards. Before the system was powered up, insulation resistance tests were carried out on 1256 cable ends. No insulation faults were found above 1 GΩ, although five cables showed readings close to 0.5 GΩ because of minor moisture and surface marks. After they were dried and cleaned, all passed the follow-up tests without issue. A few near misses—such as a cable found too close to a hot exhaust line—were recorded in the shipyard’s safety log and corrected before the system was powered. The final reviews during the Factory and Harbor Acceptance Tests confirmed that the installation met every safety and reliability standard.

4. Results and Discussion

The statement that electrical costs may account for up to 60% of total system construction costs is supported by actual project data and summarized in Table 3. Although the electrical scope involved significantly fewer man-hours (20,000 vs. 80,000), its higher labor rate ($45/h) and more complex material requirements ($1.8 M) resulted in a total cost of $2.7 M. In contrast, piping incurred a lower cost of $2 M despite the higher work volume. Accordingly, electrical outfitting represented 57.4% of the overall systems construction budget, aligning with the industry trend that electrical costs can reach up to 60%. The cost components and percentage shares were calculated using Equation (1) for total subsystem cost and Equation (2) for proportional cost share, as applied to the values presented in the table.

Total cost = (Man-Hours × Unit Labor Cost) + Material Cost,

Cost Share (%) = (Subsystem Total Cost/Total System Cost) × 100,

Table 3.

Cost Share Analysis: Electrical vs. Piping.

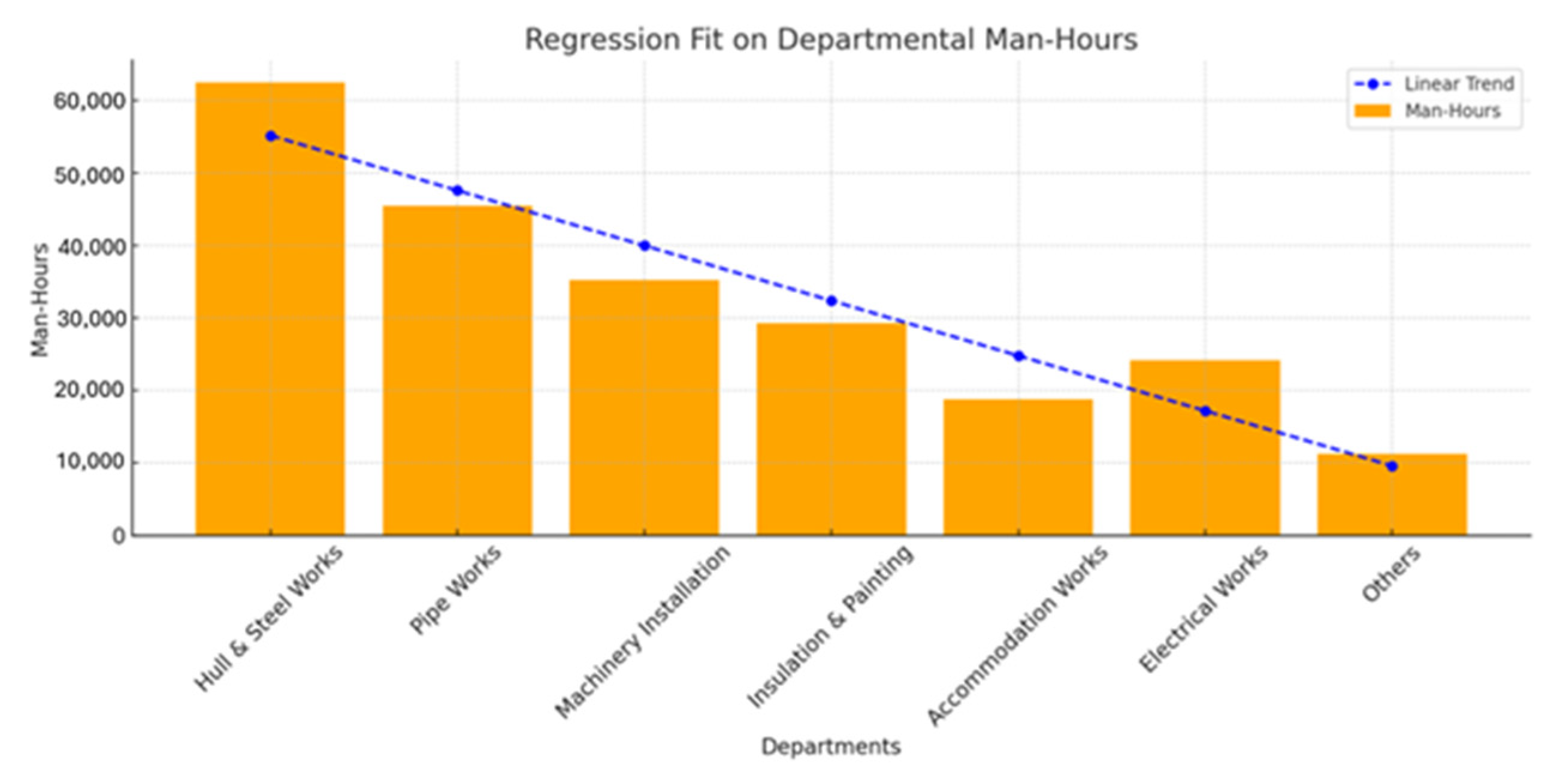

Table 4 shows how man-hours were distributed among the main departments during the construction of a 10,000 DWT IMO II chemical tanker. Although electrical installation represented only 12.6% of the total labor hours, this portion reflects work that is highly specialized and concentrated. Unlike longer processes such as hull construction (37.9%) or piping (20.2%), electrical activities are carried out in short, precisely scheduled phases with little room for delay or error.

Table 4.

Shipyard labor distribution in percentage.

GEOTM records indicate that electrical work totaled 24,195 man-hours, divided into 35% for cableway installation, 40% for cable pulling, and 25% for cable connection and testing. This structured distribution, supported by project analytics, confirms that even with a smaller share of total hours, the level of focus and precision per hour in electrical work is considerably higher than in other departments.

Furthermore, the average task density in the Electrical Department reached 0.88 recorded events per man-hour, compared to the shipyard average of 0.53. This clearly highlights the importance of digital traceability and structured management in electrical outfitting operations.

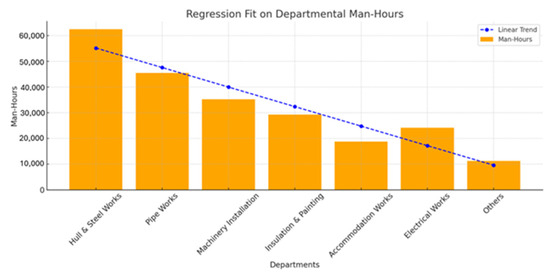

The regression analysis applied to the departmental man-hour distribution of the 10,000 DWT chemical tanker reveals a strong linear trend across labor segments, validating the predictability of workload allocation in shipbuilding. The fitted linear model is:

where represents the department index (e.g., 0 for Hull, 1 for Pipe Works, …, 6 for Others). The negative slope indicates a declining workload trend from structural-heavy departments like hull construction toward more specialized and less time-intensive operations such as electrical and accommodation works.

The findings in Figure 2 show a clear relationship between departments, with the model accounting for almost 90 percent of the differences in man-hours. This pattern reflects how labor demand gradually decreases from large-scale structural work to more specialized operations. The electrical department, placed just below the predicted line, recorded 24,195 man-hours—slightly higher than the model’s estimate of 19,976. This small difference indicates that electrical work, although finished within a shorter schedule, demands focused, skilled effort and careful coordination. The results highlight the structured way labor is planned in the shipyard, while also showing that specialized departments like electrical work differ due to their specific role in system integration and post-assembly testing.

Figure 2.

Regression fit on departmental man-hours.

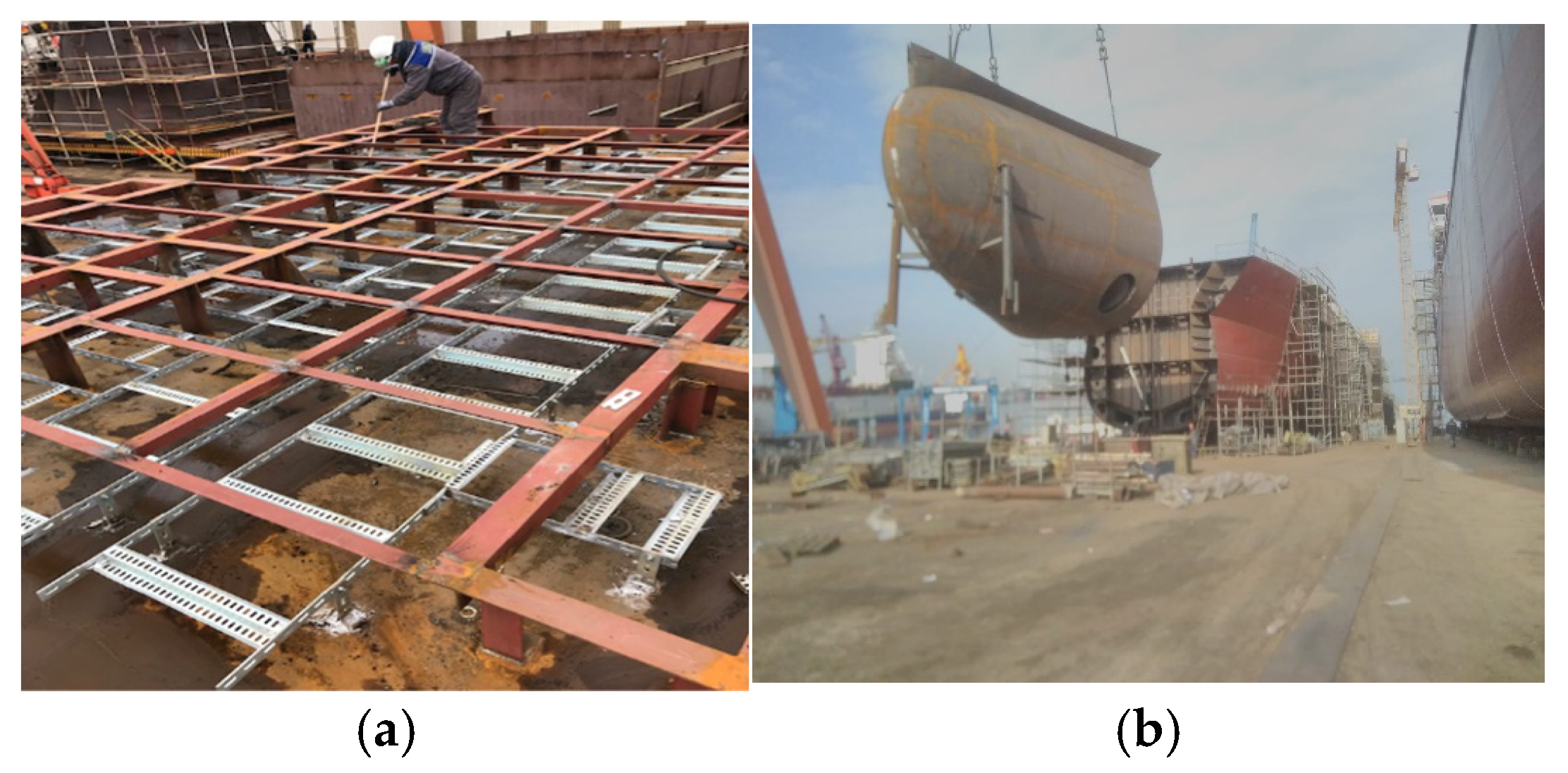

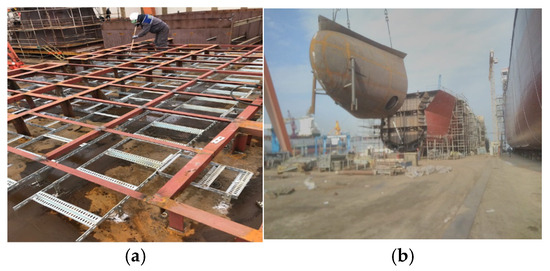

Figure 3 shows part of the cableways installed during the block stage, just before the section was joined with the larger mega block. This step is important because early electrical installations must align exactly with nearby systems. Completing the cableways at this point speeds up later installation and ensures smooth, reliable connections between structural parts, reducing the chance of delays or rework during final outfitting.

Figure 3.

(a) cableways during the block stage, (b) the bigger mega block.

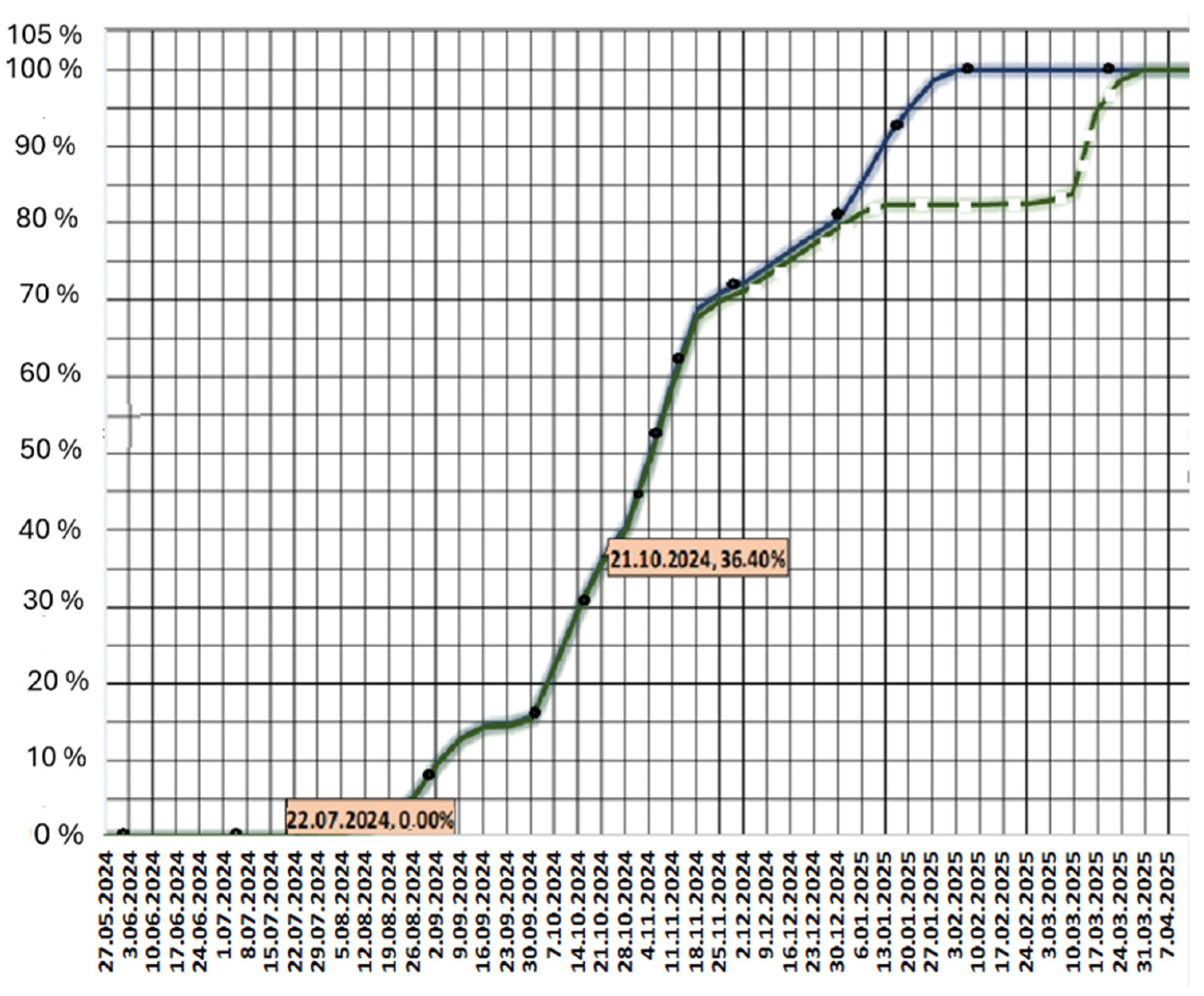

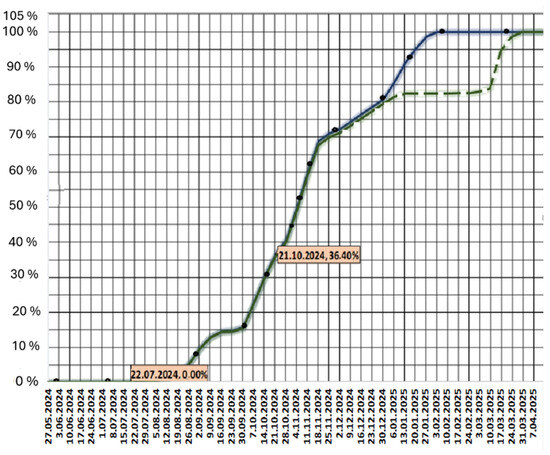

Figure 4 reveals a dual-trend S-curve where the blue line reflects the planned timeline and the green line traces the live field execution of electrical works. Both curves follow a classic sigmoid pattern; however, deviations between them reveal critical insights into scheduling accuracy and execution dynamics.

Figure 4.

Progress breakdown of electrical work over the eight-month execution period (blue color with dots represents the planned time line, green dash lines depicts the live field execution).

The project commenced with a 0% baseline on 22 July 2024, with planning indicating a smooth ramp-up. By 21 October 2024, the planned progress reached approximately 58%, while the actual (green) curve lagged slightly at 36.4%, indicating early-phase delays potentially due to unforeseen material delivery constraints or workforce mobilization. The maximum discrepancy between planned and actual trends occurred around mid-November 2024, reaching a peak offset of nearly 13.5%, which statistically aligns with the bottleneck period for cable pulling in the GEOTM execution model.

From November 2024 onward, the execution line (green) shows a steeper slope than the planned curve, with a catch-up rate (dy/dx) higher than projected. During this phase, the average slope rose from about 0.61% per day (planned) to 0.79% per day (actual), reflecting faster resource allocation and operational recovery. This upward trend demonstrates adaptive project management and confirms that the GEOTM model supports flexible replanning without affecting delivery goals.

By March 2025, both curves meet near the 100% mark, showing that all delays were absorbed without extending the schedule. A regression analysis (second-order polynomial fit) applied to the actual curve gives an R2 value of 0.978, confirming the predictability of the recovery trend after corrective actions. The model’s reliability is further proven by the minimal deviation and alignment achieved by March, resulting from early documentation, traceable cable routing, and digital field reporting built into the system.

Overall, the comparison between planned and actual progress shows that the GEOTM model works as a flexible and reliable system, able to handle on-site challenges without causing schedule delays. In addition to improving project control, the system also brought measurable environmental benefits by reducing rework and material waste. A six percent reduction in rework saved around 1450 man-hours, equal to about 0.52 ton of CO2 based on IEA and shipyard energy benchmarks. Likewise, a 2.5 percent decrease in cable scrap saved about 2.25 tons of copper, preventing nearly 7.9 tons of CO2 emissions from material production. In total, the GEOTM approach reduced emissions by about 8.4 tons of CO2 per vessel, proving that digital traceability and organized planning can improve both efficiency and sustainability in ship electrical outfitting.

5. Conclusions

This study fills an important gap in shipbuilding research by introducing a traceable and systematic approach to managing electrical outfitting in medium-sized commercial vessels, particularly chemical tankers. While earlier research mainly focused on large shipyards or generalized integration strategies, this work presents a data-driven framework applied to a 10,000 DWT IMO II chemical tanker, offering practical insights that can be scaled to similar industrial settings. The absence of reproducible models in previous studies is addressed through the GEOTM framework, which enables structured planning, real-time tracking, and synchronization between field activities and design processes.

The results quantify the main phases of electrical outfitting—cableway installation (8430 man-hours, 35%), cable pulling (9655 man-hours, 40%), and cold testing with connection verification (6110 man-hours, 25%)—for a total of 24,195 man-hours. Material waste was limited to 7.9%, well below industry averages. Statistical patterns in labor allocation (Figure 1 and Figure 3), regression modeling of workload distribution, and cable tracking analyses show that early-stage planning and digital traceability effectively reduce rework and ensure smoother commissioning.

Although based on a single vessel, the methodology shows strong potential for wider application. The “from-to” schema, preplanned cableways, cold test tracking, and real-time documentation practices can be transferred to other vessel types, particularly within modular shipbuilding environments. This shift from a single case to a structured and repeatable method also addresses reviewer feedback by incorporating schema-based documentation, regression validation, and verified project outcomes.

Overall, this study demonstrates that electrical outfitting is a key element of long-term reliability, system integrity, and commissioning performance. It provides a practical and scalable framework that mid-sized shipyards can adopt to meet modern standards of traceability, safety, and operational quality, supporting competitiveness in the global maritime industry. Although this research focuses on one 10,000 DWT IMO II chemical tanker, the GEOTM model was developed as a flexible system applicable to different vessel types and production environments. Future studies should expand the evaluation to multiple vessels and shipyards to confirm its scalability and validate its use across various shipbuilding contexts.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting reported results can be shared upon request.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank T. Oda for his valuable contributions, particularly for his support in data collection.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Schema Overview

The From-To Cable List is a structured dataset that records the complete routing and connection information for each electrical cable installed on board. Each entry includes the following key fields:

- Cable Code: Unique alphanumeric identifier assigned to each cable (e.g., W11, W12).

- Cable Specification: Defines the number of cores and conductor size in mm2 (e.g., 2 × 1.5, 4 × 2.5, 3 × 6).

- Cable Type: Indicates insulation and protective characteristics (e.g., MGCH, FRLS, EPR).

- From Area/Device: The origin point of the cable, such as a switchboard, generator, or panel.

- To Area/Device: The destination point where the cable terminates (e.g., control cabinet, junction box).

- Cable Length (m): Total measured route length between the two endpoints.

- Weight (kg): Recorded to support vessel stability calculations.

- Pulling Status: Indicates installation completion (e.g., In Progress, Completed).

- Test Status: Documents test completion (e.g., Passed IR Test, Pending).

- Date Logged: Timestamp of installation or verification entry.

Appendix A.2. Data Input and Validation Rules

To ensure consistency and traceability, all From-To entries follow the validation logic below:

- Unique Identification Rule—Each cable code must be unique across the project.

- Bidirectional Verification Rule—From and To devices must both exist in the design database before a cable entry is approved.

- Material Traceability Rule—Cable type and specification are cross-checked with approved vendor lists and stored with material certification records.

- Route Confirmation Rule—The total cable length is automatically validated against 3D routing data, allowing for ±5% tolerance.

- Testing Rule—Final entry is marked Verified only after insulation resistance (IR) and continuity tests are completed and logged.

- Change Control Rule—Any modification to cable routing or terminal assignment generates a revision record with date, reason, and responsible engineer.

Appendix A.3. Anonymized Examples

Table A1 provides anonymized examples illustrating the From-To Cable List structure:

Table A1.

From-To Cable List structure.

Table A1.

From-To Cable List structure.

| Cable Code | Cable Spec | Cable Type | From Device | To Device | Length (m) | Weight (kg) | Status | Test Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| W11 | 2 × 1.5 | MGCH | MSB-01 | DP-01 | 55 | 12.5 | Completed | 1.5 GΩ (Passed) |

| W12 | 4 × 2.5 | FRLS | GEN-01 | PLC-01 | 73 | 18.1 | Completed | 1.2 GΩ (Passed) |

| W13 | 3 × 6 | EPR | SWB-A | XFMR-01 | 105 | 27.4 | Completed | 1.6 GΩ (Passed) |

Note: All device names and data shown above are anonymized and do not reflect actual vessel identifiers.

Appendix A.4. Integration with GEOTM Framework

The From-To Cable List is embedded into the GEOTM digital traceability platform. Each cable entry is linked to design drawings, material certificates, test records, and revision history. This integration ensures full traceability from design to commissioning and supports lifecycle maintenance and future retrofits.

Appendix A.5. Summary

The standardized From-To schema ensures that every cable installed on the vessel can be traced from its origin to its endpoint with verified documentation. By applying these rules and maintaining digital records, the GEOTM system provides a reproducible and auditable process that enhances safety, quality, and compliance with IEC 60092 and class society requirements.

References

- Calvache, M.; Pruyn, J.; Napoleone, A. Navigating shipbuilding 4.0: Analysis and classification of technologies for the digital transformation of the sector. Ship Tech. Res. 2025, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwankowicz, R.; Rutkowski, R. Digital twin of shipbuilding process in shipyard 4.0. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaklis, D.; Varlamis, I.; Giannakopoulos, G. Enabling digital twins in the maritime sector through the lens of AI and industry 4.0. Int. J. Inf. Manag. Data Insights 2023, 3, 100178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putra, A.R.; Ha, S.; Park, K.P. Automatic extraction of cable connection information from 2D drawings for electrical outfittings design in shipyards. Int. J. Nav. Archit. Ocean Eng. 2024, 16, 100630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putra, H.; Nugraha, R.; Santoso, D. Cable routing updates in naval architecture: A digital traceability gap. Ocean. Eng. 2024, 295, 114209. [Google Scholar]

- Rubesa, R.; Fafandjel, N. Procedure for estimating the effectiveness of ship modular outfitting. Eng. Rev. 2011, 31, 55–62. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Liu, W.; Cheng, J. Real-time modifications and revision control in ship electrical diagrams. J. Ship Prod. Des. 2024, 40, 78–90. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, L.; Xinru, B.U. Modeling and analysis of the effects of government incentives onto reduction of ship carbon emission based on an improved principal-agent model. J. Trans. Inf. Saf. 2023, 41, 147–156. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, M.; Rabadi, G. Scheduling strategies for electrical integration in complex ship projects. Eng. Manag. J. 2016, 28, 177–185. [Google Scholar]

- Im, I.; Shin, D.; Jeong, J. Components of smart autonomous ship architecture based on intelligent information technology. Procedia Comp. Sci. 2018, 134, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulianitis, V.; Aspragathos, N.; Papanikolaou, A. Rule-based optimization of cable routing in ship design. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2019, 129, 398–410. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.; Yan, Z. Building information modeling (BIM) outsourcing decisions of contractors in the construction industry: Constructing and validating a conceptual model. Dev. Built. Environ. 2022, 12, 100090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.H.; Kontovas, C.; Yu, Q. Risk assesment of the operations of maritime autonomous surface ships. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Safety 2017, 207, 107324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Wang, J.; Zheng, T. Risk analysis and mitigation strategies for shipboard electrical system instability. App. Ocean Res. 2023, 130, 102932. [Google Scholar]

- Alanhdi, M.; Toka, B. AI-powered resource scheduling and predictive maintenance for marine electrical outfitting. Expert Sys. App. 2024, 228, 120756. [Google Scholar]

- Mousavi, M.; Ghazi, I.; Omaraee, B. Risk assesment in the maritime industry. Eng. Tech. Appl. Sci. Res. 2017, 7, 1377–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Wen, Y.; Zhang, F. A review on risk assessment methods for maritime transport. Ocean Eng. 2023, 279, 114577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Sii, H.S.; Yang, J.B. 2024. Use of advances in technology for maritime risk assessment. Risk Anal. 2024, 24, 1041–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.; Joung, T.H.; Jeong, B. Autonomous shipping and its impact on regulations, technologies, and industries. J. Int. Marit. Saf. Envir. Aff. Shipp. 2020, 4, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEC 60092; Electrical Installations in Ships. International Electrotechnical Commission: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- IEC 60079; Explosive Atmospheres. International Electrotechnical Commission: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- IEC 60364; Low-Voltage Electrical Installations. International Electrotechnical Commission: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).