Abstract

The transition to a circular economy (CE) in plastic packaging faces persistent barriers, including regulatory fragmentation, technological limitations, and supply chain disconnection. This study examines how multinational companies address these challenges by leveraging enablers such as advanced policies, technological innovation, and cross-sectoral collaboration. Based on a PRISMA-guided systematic review and a descriptive–explanatory case study, semi-structured interviews with senior managers were analyzed through thematic coding and data triangulation. Findings reveal that regulatory measures like virgin plastic taxation and post-consumer recycled material (PCR) incentives are effective only when synchronized with technical capacities. Investments in recycling infrastructure and circular design, such as resin standardization, enhance the quality of secondary materials, while local supply contracts and digital traceability platforms reduce volatility. Nevertheless, negative consumer perceptions and inconsistent PCR quality remain major obstacles. Unlike prior studies that examine barriers and enablers separately, this research develops an integrative framework where their interaction is conceptualized as a systemic and non-linear process. The study contributes to CE theory by reframing barriers as potential drivers of innovation and provides practical strategies, combining policy instruments, Industry 4.0 technologies, and collaborative governance to guide multinational firms in accelerating circular transitions across diverse regulatory contexts.

1. Introduction

Over the last century, industrial development has been predominantly shaped by a linear take–make–dispose production model. This system, based on the extraction of virgin raw materials, mass manufacturing, and short consumption cycles, has led to unprecedented levels of waste and resource depletion [1,2,3]. Plastic production has surged since the 1950s, with global output expected to reach 450 million tons annually by 2025. This growth has led to rising pollution, especially in marine environments, where an estimated 11 million metric tons of plastic enter the ocean each year from land-based sources [4].

Packaging is one of the most widely used products in modern consumer economies. It consists of various materials that contain, protect, and facilitate the handling and distribution of goods, from raw materials to finished products [5]. Plastic packaging, due to its lightness, durability, and versatility, has become a cornerstone of modern economies, yet it represents one of the most pressing sustainability challenges. However, the proliferation of plastic waste, chiefly from packaging sources, threatens ecological systems and represents inefficient resource utilization, emphasizing the importance of transitioning toward sustainable circular economies that emphasize waste prevention and recycling practices [6].

Current estimates indicate that over 9.2 million metric tons of plastic packaging are produced annually, largely concentrated among multinational firms such as Coca-Cola, Nestlé, Unilever, and PepsiCo [7,8]. The majority of this packaging is designed for single use and does not re-enter economic cycles after consumption, contributing significantly to land and marine pollution [9,10], and going against the trends and preferences of some consumers [11]. Besides the non-biodegradable nature of plastic has generated an environmental crisis of global proportions, with documented ecological consequences in diverse ecosystems [12].

The urgency of this challenge is reflected in global policy responses. Some initiatives have introduced legislation to restrict or ban certain single-use plastics [13], while the European Commission has launched a comprehensive Strategy for Plastics in a Circular Economy aimed at reducing virgin plastic consumption, improving recyclability, and stimulating investment in sustainable packaging solutions [14]. Likewise, the recent European regulation on packaging and packaging waste aims to expand sorting and recycling facilities and strengthen reverse logistics systems [15]. International organizations, including the Ellen MacArthur Foundation (EMF) and the World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD), have further emphasized the need to reconfigure supply chains under circular principles that promote reuse, recycling, and regenerative design [16,17,18,19]. These initiatives highlight a paradigm shift in which plastics, a symbol of industrial innovation, must be reimagined as part of regenerative material cycles.

The CE offers a systemic framework to achieve this transformation by closing material loops, reducing waste, and prioritizing renewable inputs [20,21]. Moreover, CE aims to decouple economic growth from finite resource consumption and extend the life cycle of products to minimize environmental impacts while improving profitability through circular business models [22,23,24]. This is evidenced by the potential employment growth in CE sectors in Europe, where 4.3 million jobs were registered in 2023, with Germany leading the way as the largest employer [25]. Projections suggest that a comprehensive adoption of circular strategies in plastics could reduce waste leakage into the oceans by up to 80% by 2040, and generate significant material cost savings [26,27]. Beyond environmental benefits, CE also promises economic competitiveness, job creation, and new business models aligned with Industry 4.0 technologies [28,29,30]. Therefore, for multinational firms operating in global supply chains, the CE is no longer a peripheral sustainability agenda but a strategic imperative.

Despite the strong interest in the CE, especially in plastics packaging, academic research on the topic remains fragmented. Scholars have identified a wide range of barriers such as fragmented and sometimes contradictory regulatory frameworks [31,32], technological constraints related to recycling and material quality [33,34], and structural inefficiencies in supply chain coordination [35,36]. These studies provide valuable insights into individual obstacles but tend to treat them in isolation, offering only partial explanations of why circular transitions stall.

On the other hand, research on enablers has highlighted key drivers that can facilitate circular practices. These include regulatory instruments such as extended producer responsibility [37], fiscal incentives like eco-modulated tariffs [38], technological innovations including blockchain traceability and advanced recycling methods [39,40,41], and supply chain collaborations that align upstream producers and downstream recyclers through circular innovations [11,32,42]. However, much like the barriers literature, studies of enablers often analyze them as stand-alone interventions without examining how their effectiveness may vary across jurisdictions, industries, or organizational capacities.

This fragmented perspective leaves a critical gap in the literature. As Alshemari et al. [43] emphasize, the ability of enablers to overcome barriers depends on temporal synchronization, resource availability, and multi-stakeholder alignment. For example, tax incentives to encourage recycled plastic use may be ineffective if technological infrastructure for material recovery is lacking, or if consumers continue to distrust recycled packaging [31,44]. Without an understanding of these systemic interactions, policy measures and corporate strategies may become fragmented and counterproductive, thereby exacerbating the problems they aim to solve.

Therefore, the unresolved issue is the lack of integrative frameworks explaining how CE enablers neutralize or transform specific barriers within global plastic packaging value chains. While Maione et al. [34] offer pioneering insights into institutional enablers, most scholarship has yet to conceptualize the dynamic interplay between structural obstacles and strategic drivers. Current models tend to either emphasize the technological feasibility of recycling innovations [45,46,47] or the regulatory scaffolding needed to incentivize circularity [48,49], but rarely both. This isolated approach underestimates the complexity of multinational operations, where firms must face heterogeneous regulatory environments, volatile commodity markets, and diverse consumer perceptions simultaneously.

The stakes of this omission are not merely academic. Multinational firms deal with increasing investor scrutiny, regulatory compliance risks, and consumer pressure to demonstrate verifiable environmental commitments [50]. In such contexts, the failure to model barrier–enabler interactions leads to misaligned strategies. For instance, companies may invest heavily in recyclable packaging materials, only to discover that local waste management infrastructure cannot process them, or that regulatory fragmentation prevents cross-border material flows and synergies [51]. Conversely, regulatory bans on virgin plastics may accelerate circular innovation in some markets but create supply chain bottlenecks in others [42]. A systemic perspective is thus indispensable to avoid unintended trade-offs and to design scalable solutions.

Despite these advances, existing studies remain fragmented, which motivates this study to address the following research question: How can CE enablers overcome barriers to circularity in plastic packaging companies? To answer this, we integrate a PRISMA-based systematic review of academic and institutional sources with an in-depth case study of a leading multinational company in the plastic packaging sector. The case study methodology, grounded in semi-structured interviews with senior managers, allows us to examine how firms operationalize enablers in practice such as Industry 4.0 technologies, local supply contracts, and extended producer responsibility policies, and how these interact with persistent barriers. By triangulating interview data with documentary evidence, we capture the systemic interplay between regulatory frameworks, technological capacities, and supply chain governance.

The contribution of this study is twofold. First, it advances CE theory by reconceptualizing the transition to circularity as a process in which enablers and barriers interact dynamically. Rather than providing a static list of obstacles and drivers, this perspective frames their interaction as a potential source of competitive advantage in plastic-intensive industries. Second, it provides practical insights for multinational companies and policymakers. The study proposes integrated strategies that combine regulatory instruments, digital technologies, and collaborative governance mechanisms, offering actionable pathways to accelerate circular transitions in diverse regulatory contexts. By situating enablers and barriers within a systemic framework, this paper contributes to both scholarly debates and managerial practice, illuminating how the CE can be effectively scaled in one of the most resource-intensive and environmentally significant sectors of the global economy.

2. Methodology

This research adopts a case study combined with a descriptive–explanatory approach. A mixed-methods approach has been proven to be useful to identify the enablers and barriers associated with adopting CE practices [43]. Case studies are particularly suitable for examining contemporary phenomena within their real-life contexts, especially when boundaries between the phenomenon and its environment are blurred [52]. In this study, the CE transition in the plastic packaging sector represents a complex system of interdependent regulatory, technological, and supply chain dimensions that cannot be meaningfully isolated from their global and organizational contexts.

The descriptive dimension of the research enables the systematic characterization of enablers and barriers, building on an existing theoretical and empirical foundation. The explanatory dimension, in turn, seeks to uncover the causal mechanisms linking enablers to the mitigation of barriers, thus providing insight into how integrated strategies accelerate circularity. This dual orientation aligns with the logic of exploratory case studies, which emphasize depth of analysis and the identification of causal patterns over statistical generalization [53].

2.1. Case Study

This article is based on a case study whose selection criterion prioritizes relevance over statistical representativeness. The case selected is a leading multinational corporation in the plastic packaging sector which operates across diverse regulatory markets, from advanced jurisdictions with harmonized CE policies like the European Union (EU), to emerging economies with less developed infrastructures and fragmented regulations. This heterogeneity provides a unique opportunity to analyze how enablers interact with barriers under contrasting institutional and market conditions. The anonymity of the company has been preserved due to confidentiality agreements, but its multinational scope and leadership position make it an exemplary case for analyzing systemic CE transitions in plastics-intensive industries.

The firm was further selected for its leadership in circular strategies, including early adoption of recycled resins, collaboration with local supply chains, and investment in traceability technologies. Its visibility in international sustainability rankings, combined with its proactive involvement in policy dialogues, strengthens the external validity of the case by ensuring that lessons derived from it have broader relevance for the industry [34,42,51,54].

2.2. Systematic Literature Review (PRISMA)

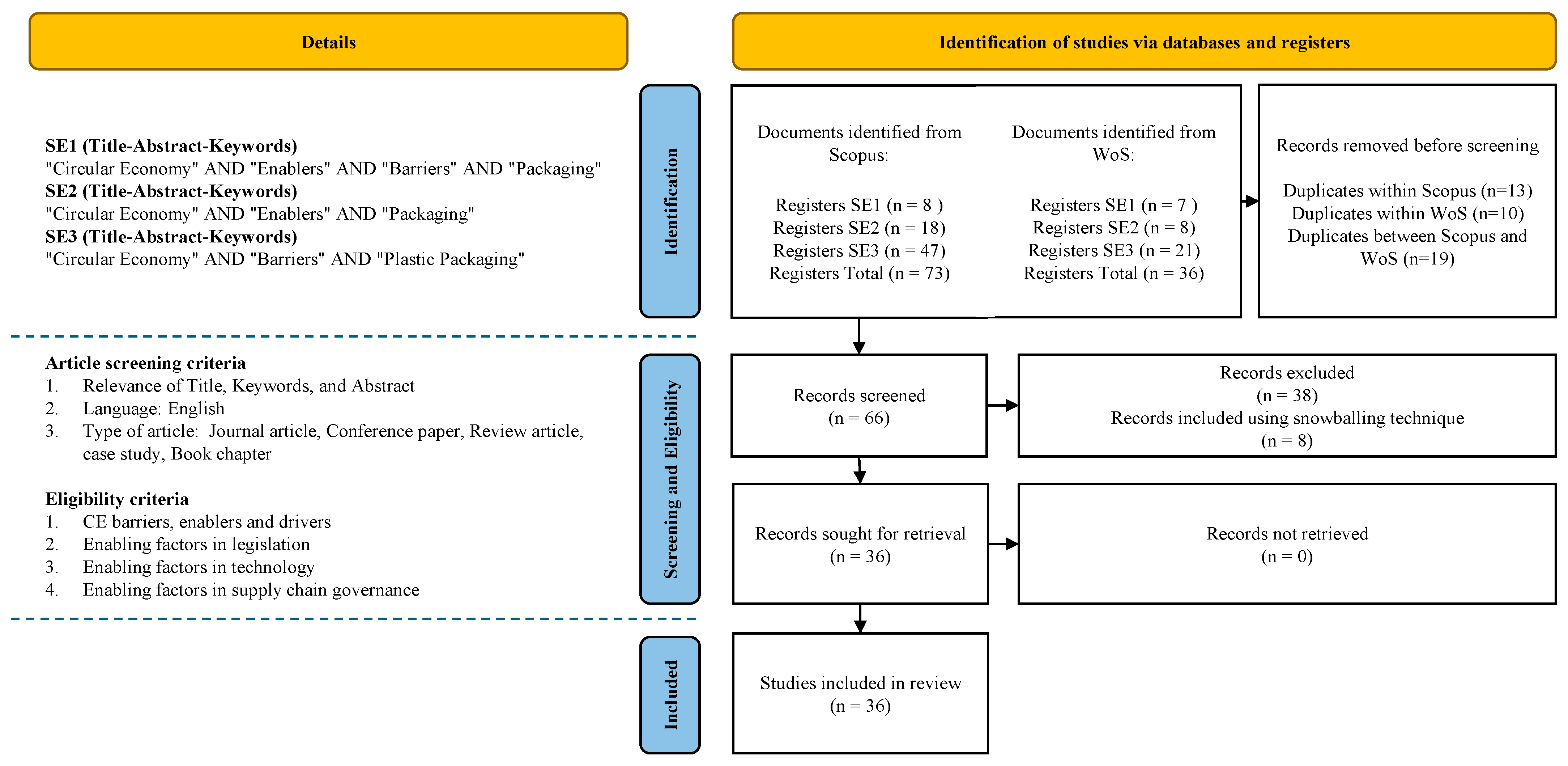

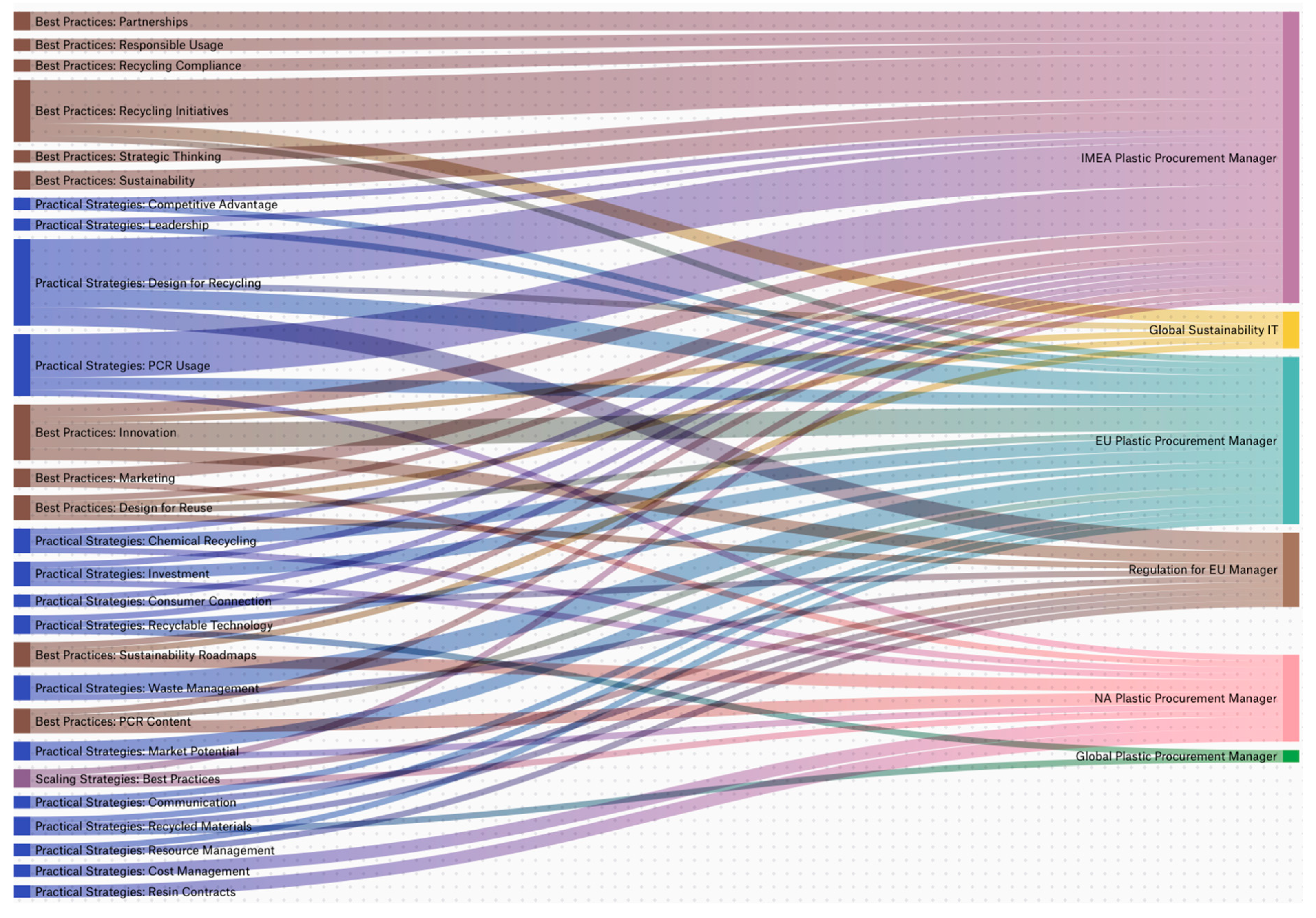

To build the theoretical framework and ensure methodological rigor, a systematic literature review was conducted following the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines [55]. This protocol was applied to two major academic databases (Scopus and Web of Science) to identify, evaluate, and synthesize relevant knowledge on enablers and barriers to CE in plastic packaging. No time restrictions were applied in the database search to capture the complete body of relevant knowledge on barriers and enablers of circular economy CE in plastic packaging. As shown in Figure 1, search equations combined key terms related to the CE, barriers, enablers, and plastic packaging. Likewise, the document identification and screening process followed the PRISMA flow structure.

Figure 1.

Document search and evaluation process.

The initial search yielded 109 documents (73 from Scopus and 36 from WoS). Removal of duplicates within the search equations provided a corpus of 86 scientific documents, comprising 60 sourced from Scopus and 26 from WoS. Then, prioritizing Scopus records when overlaps occurred and considering 20 documents in common between Scopus and WoS, we obtained 66 documents to conclude the identification phase.

During the screening phase, documents were evaluated according to their thematic alignment with the research objectives based on their title and abstract. Exclusion criteria applied to 38 documents that, although related to plastics or packaging, primarily addressed topics outside the scope of this study, such as biomaterials development, food preservation, construction applications, or generic sustainability models. These contributions did not directly examine the dynamics of barriers, enablers, or drivers in CE transitions of plastic packaging, nor did they focus on the regulatory, technological, or supply chain dimensions central to this research. Conversely, eligibility criteria prioritized studies explicitly analyzing CE barriers and enablers, as well as those addressing enabling factors in legislation, technology, and supply chain governance. Eligibility assessment through full-text review ensured that the final selection of sources provided a coherent and focused foundation to analyze how CE enablers can overcome barriers in plastic packaging transitions.

After applying these criteria, a final corpus of 28 articles was retained. Additional relevant publications from top publishers (Elsevier, Springer, Emerald, Taylor & Francis) that met the required quality standards and were relevant due to their thematic relevance were incorporated through backward snowballing, resulting in a set of 36 peer-reviewed scientific articles. The final set of included studies spans publications from 2020 to 2025, representing the period of most active academic and policy-related development on this topic.

Table 1 shows the documents included in the systematic review that were retrieved from the Scopus and WoS databases, as well as those obtained through the snowballing technique.

Table 1.

Documents included in the review.

To complement the academic literature, 14 institutional documents from key organizations were reviewed, including the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, World Business Council for Sustainable Development, World Economic Forum, and Eurostat. These reports presented in Table 2 provided statistical data, policy frameworks, and industry practices directly relevant to the case study. The final set of 49 documents (37 academic, 12 institutional) was qualitatively assessed to extract recurring themes, concepts, and frameworks. These insights informed the design of the case study and the development of the interview guide.

Table 2.

International organizations consulted for the investigation.

2.3. Semi-Structured Interviews and Data Coding

To complement the literature review, semi-structured interviews based on prepared questions (Appendix A) were conducted with strategic actors within the multinational company. This method is particularly suited for exploring complex organizational phenomena, as it balances a structured line of inquiry with the flexibility to capture emerging themes [86]. The interview sample comprised six senior managers occupying roles in sustainability, supply chain management, packaging design, and regulatory compliance. Participants were selected purposively to ensure coverage of the three main CE dimensions: regulatory, technological, and supply chain. Each participant had over 10 years of industry experience and direct involvement in CE initiatives, enhancing the internal validity of responses.

The interview protocol was structured around the following themes derived from the literature review: Perceptions of regulatory frameworks (barriers and opportunities), technological capacities and constraints in advancing circular packaging, and supply chain coordination and collaboration practices. Questions were designed to elicit both descriptive information and explanatory insights into causal dynamics. The interview guide (Appendix B) drew on prior CE research employing semi-structured interviews [45,87,88,89]. Interviews were conducted virtually, recorded with participant consent, and transcribed verbatim. Ethical protocols regarding confidentiality and anonymity were strictly observed. The average duration was 60 min.

Interview transcripts were analyzed using ATLAS.ti 23, a qualitative data analysis software that facilitates systematic coding and categorization of textual data. Following the principles of thematic analysis [90,91], the coding process unfolded in three stages: (i) Open coding, where key phrases and concepts were identified; (ii) axial coding, grouping codes into broader categories aligned with barriers and enablers; (iii) selective coding, integrating categories into themes that explained barrier–enabler interactions. Codes were derived deductively from the literature review (e.g., “regulatory fragmentation,” “technological innovation,” “supply chain collaboration”) and inductively from emerging interview data (e.g., “consumer perception,” “local contracts”). This hybrid strategy allowed for both theoretical grounding and empirical nuance.

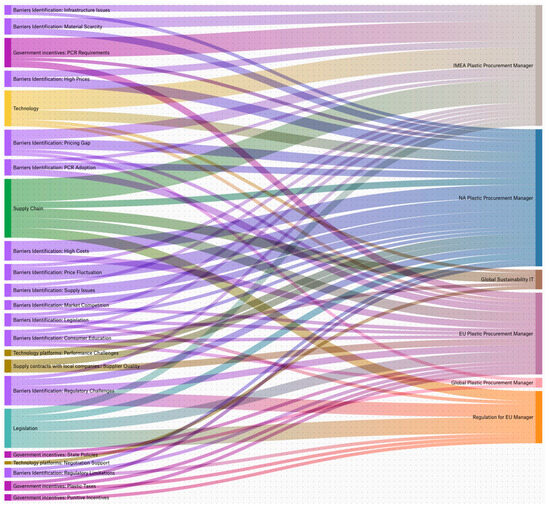

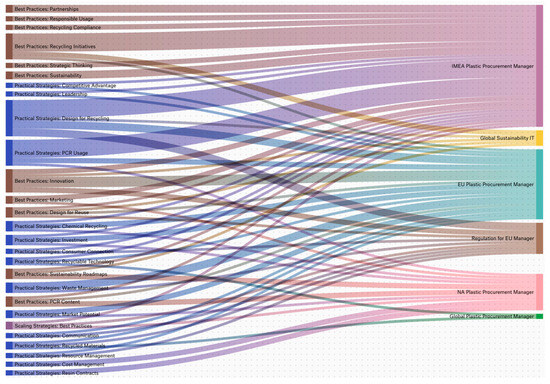

To visualize the relational patterns emerging from the coding process, Sankey network diagrams were generated using ATLAS.ti 23. These diagrams illustrate the relational density among managerial roles, enablers, barriers, and CE practices identified in the interviews. Although visually complex, they provide a transparent representation of how specific concepts overlap across roles and highlight the degree of convergence and divergence in managerial perceptions.

2.4. Data Triangulation

To strengthen the validity and reliability of the research, methodological triangulation was applied. This approach combined a systematic literature review (academic and institutional), case study evidence from semi-structured interviews, and a documentary analysis of corporate sustainability reports and policy documents. This framework comprises construct validity, contextual control, external validity, and reliability criteria, which guarantee the technical soundness and traceability of the research process and the verifiability of its conclusions.

Construct validity was ensured by aligning operational measures with theoretical concepts. Barriers were categorized as operational, regulatory, or cultural, and enablers were categorized by structural or functional components. Internal validity was reinforced by cross-checking interview responses with documentary sources. Contextual control was achieved through case selection for theoretical relevance. Temporality corresponded to the diachronic analysis of interactions, or how barriers and enablers evolve. Process theory was related to a clear mechanism linking enablers to the overcoming of barriers.

The multinational scope of the case supported external validity, allowing analytical generalization to other firms in similar contexts. The job positions, experience, and knowledge of those who answered the semi-structured interview served as external validators. Reliability was achieved by documenting the research protocol, coding procedures, and analytical decisions, which enables replication by other researchers. Additionally, the selection of a leading global company is substantiated by its international leadership in CE strategies for packaging, its presence in markets with diverse regulatory frameworks, and its proven ability to implement technological and collaborative solutions. Analyzing the case study allows us to extract pertinent lessons about overcoming systemic barriers in real, complex contexts. This strengthens the study’s analytical validity.

Based on the combined methodological approach, the following propositions guided data analysis:

- Regulatory enablers are effective only when temporally synchronized with technological and infrastructural capacities.

- Technological innovations require supportive supply chain collaboration to scale effectively.

- Integrated governance mechanisms that align enablers across domains generate more sustainable outcomes than isolated interventions.

These propositions structured the analysis of results and informed the interpretation of barrier–enabler dynamics in the case study. Based on these propositions, the study implicitly contrasts the following research hypothesis.

H1.

The successful implementation of circular economy strategies in the plastic packaging industry depends on the synergistic interaction among regulatory coherence, technological innovation, and supply chain collaboration.

H0.

The successful implementation of circular economy strategies in the plastic packaging industry does not depend on the interaction among regulatory coherence, technological innovation, and supply chain collaboration.

The analysis of empirical evidence aimed to explore whether the observed patterns in the case study support or refute this hypothesis by demonstrating the extent to which regulatory, technological, and supply chain enablers interact to overcome persistent barriers. In this way, by integrating a PRISMA-based literature review with a case study of a multinational leader, this research builds a robust methodological framework to examine the interaction between barriers and enablers of CE in plastic packaging. Semi-structured interviews, systematic coding, and triangulation ensured both depth and rigor, providing a solid empirical foundation for the subsequent results and discussion.

3. Barriers and Enablers for the CE in Plastic Packaging

The linear production and consumption model, characterized by resource extraction, short-use cycles, and disposal, has reached its ecological and economic limits [81,92]. In this context, the CE has emerged as a paradigm that aims to decouple economic growth from resource consumption through strategies of reducing, reusing, recycling, and recovering materials [38,93]. According to Mondello et al. [94], CE strategies must be intrinsically connected to specific practices that address various aspects of the production cycle. These strategies should focus not only on waste management but also on reconfiguring production and consumption systems to promote a more sustainable and equitable paradigm. Unlike incremental sustainability models, CE proposes a systemic transformation built on regenerative design, elimination of waste, and closed material loops [59,95,96].

Plastic packaging occupies a central place in this debate. It accounts for 40% of total global plastic demand and represents one of the most significant sources of waste, with recycling rates remaining barely over 40% in some countries in the European region [75,83]. The functional advantages of plastic packaging such as durability, versatility, low cost are paradoxically the same factors that hinder its reintegration into material cycles [82,97]. Consequently, the packaging sector has become a priority for policy frameworks such as the European Strategy for Plastics in a Circular Economy [14]. Theoretical and empirical research consistently identify this sector as both a challenge and an opportunity for advancing circularity [98,99].

3.1. Barriers to CE in Plastic Packaging

The transition to CE is constrained by a network of interdependent barriers spanning regulatory, technological, and supply chain domains. Fragmented regulatory frameworks are among the most persistent obstacles. Inconsistent policies across jurisdictions generate uncertainty, discourage investment, and create inefficiencies in cross-border supply chains [49,100]. For example, bans on certain recycled plastics in food-contact applications limit the scalability of material recovery [51]. Excessive bureaucracy and lack of coordination among administrative levels exacerbate these problems [32,35,101]. Furthermore, inadequate government support such as limited financing for circular innovation, digital platforms or insufficient capacity building affects small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), leaving them unable to adapt to new requirements [102,103,104].

Technological limitations constrain circular transitions at multiple levels [78]. Much of the polyethylene terephthalate (PET) packaging that reaches the end of its useful life still ends up in downward recycling cascades or landfills/incinerators. Recycled plastics often suffer from inferior mechanical performance, reducing their applicability in high-value products [27,31]. The absence of comprehensive standards for recycled plastics and industrial-scale demonstration projects and insufficient capital for technological modernization further limit adoption [33,58,105]. Processing heterogeneous waste streams such as multilayer films or composite resins remains a major challenge, as existing infrastructure lacks the capacity to separate and purify complex materials effectively [34,64]. Equally problematic is the scarcity of reliable data on environmental performance, which prevents firms from making informed investment decisions [42].

Besides the lack of knowledge about the potential benefits of Industry 4.0 technologies [106], the main barriers to circular supply chains are the absence of knowledge about data security in relationship management and circular flows and the deficiency of knowledge about data management among stakeholders [107]. Disconnection among upstream suppliers, brand owners, distributors, and downstream recyclers leads to fragmented initiatives and collective action dilemmas [36,108]. Volatile secondary markets for recycled materials result in unstable prices and discourage long-term commitments [3,109]. Lack of transparency regarding product composition, coupled with insufficient traceability systems, undermines trust between actors and limits efficiency [103,110].

Moreover, consumer awareness and perceptions remain a non-trivial barrier since skepticism regarding the quality and safety of recycled packaging contributes to demand-side inertia [111,112,113]. Likewise, consumers can be seen as a barrier to the implementation of a CE in terms of reduction, reuse, and recycling, which is why they need education on waste management [61,67]. Therefore, regulatory fragmentation, technological bottlenecks, and supply chain disconnection form a reinforcing system of barriers that explains why circular packaging solutions often remain at pilot or niche levels rather than scaling globally.

3.2. Enablers of CE in Plastic Packaging

Parallel to barriers, the literature identifies enablers that can drive circular transitions when strategically implemented. Advanced regulatory frameworks provide the institutional support necessary for circularity and they are necessary to enable and stimulate the transition towards a more circular plastic packaging chain [51]. Regulation is perhaps the most important enabler shaping the food packaging industry [70]. Companies operating in jurisdictions with stricter or earlier environmental regulatory frameworks compared to their international competitors can obtain significant competitive advantages, such as private investment and gross added value related to CE sectors [85].

Measures such as extended producer responsibility (EPR), eco-modulated tariffs, and sustainable public procurement are recognized as powerful drivers of change [43,77,114]. Public financing for innovation, preferential credit lines, and fiscal incentives further reduce the adoption costs of circular business models [115,116]. The European regulation on packaging and packaging waste exemplifies how supranational coordination can mitigate fragmentation, harmonize standards, and encourage investment in recycling infrastructure [117].

Lopes et al. [118] emphasize the need to complement economic measures with robust information systems and continuous monitoring mechanisms, particularly for the food packaging sector, where technical and safety requirements are critical. Therefore, technological innovation plays a critical role in overcoming operational barriers. Industry 4.0 tools such as Internet of Things (IoT), blockchain, and big data analytics enable real-time traceability, enhance transparency, and optimize reverse logistics flows [119,120]. Advances in bioplastics, chemical recycling, and thermochemical recovery expand the technical feasibility of reintegrating complex materials into production cycles [16,40]. Integrated platforms for data management improve coordination and allow continuous monitoring of material flows [74,118]. These technologies not only address inefficiencies but also generate new opportunities for collaborative business models and efficiency gains [121].

Collaboration within supply chains is widely regarded as a cornerstone of circular transitions [122]. Establishing standardized recycling and reuse protocols fosters consistency and trust among actors [31]. Achieving efficient circular food packaging requires collaborative and individual engagement from all key players, encompassing material providers, packaging producers, recycling facilities, food businesses, waste management operators, public institutions, and consumers [69]. In this regard, multi-stakeholder cooperation linking governments, businesses, and consumers creates synergies that transcend individual organizational capacities [54,123]. Local supply contracts reduce exposure to volatile global markets while promoting regional circular ecosystems [124].

Moreover, consumer engagement in plastic packaging waste prevention and recycling is primarily driven by environmental awareness and perceived utility gains [6]. Transparent communication about product design and material composition enhances consumer trust and increases acceptance of recycled packaging [60,120,125]. Consequently, enablers operate across multiple domains like legislation, technology, and supply chain governance, providing firms and governments with concrete levers to accelerate circular adoption, making it possible to meet a significant portion of the demand for plastics, helping to drive the plastics life cycle to net-zero [126].

3.3. Interaction Between Barriers and Enablers

The most critical insight from recent literature is that barriers and enablers cannot be studied in isolation since enablers are established to drive the transition from linear to CE [127,128]. Their interaction forms a dynamic system where the effectiveness of enablers depends on how well they neutralize specific barriers [34].

For example, regulatory incentives such as tax reductions for recycled content are only effective when technological capacity exists to supply high-quality post-consumer resins [40]. Similarly, blockchain-based traceability platforms can improve transparency, but without regulatory support mandating disclosure, their adoption remains limited [120]. Supply chain collaboration can reduce volatility in secondary material markets, but only when harmonized regulations ensure consistent standards across jurisdictions [37].

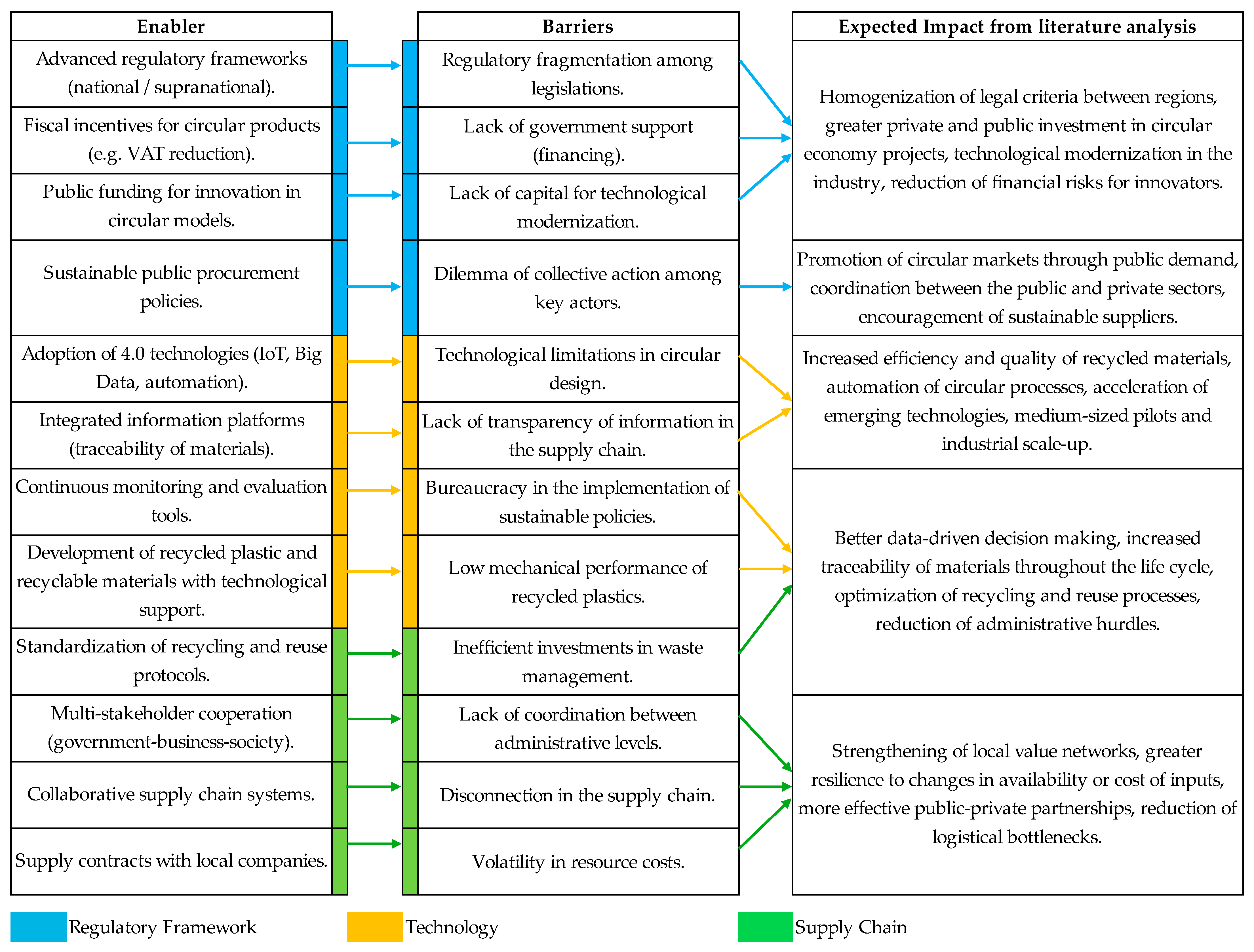

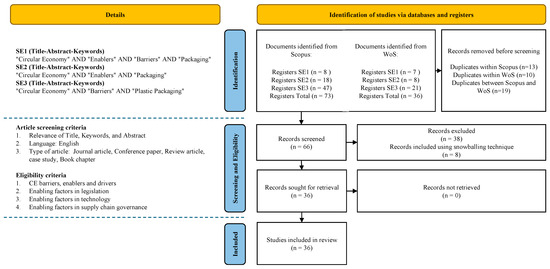

This interplay highlights two key dimensions. First, temporal synchronization is essential; policies must evolve in parallel with technological and infrastructural readiness, otherwise, interventions may backfire [43]. Second, multi-stakeholder alignment is critical. Incentives and responsibilities must be shared among governments, firms, and consumers to avoid collective action dilemmas [35]. From a conceptual standpoint, the barrier–enabler interaction represents more than a functional relationship since it constitutes the engine of circular transitions. Barriers expose structural inefficiencies, while enablers provide counterweights that can reconfigure those inefficiencies into opportunities for innovation and competitiveness [129,130,131]. Understanding this dynamic moves the literature beyond descriptive lists of obstacles and drivers, offering instead a systemic framework to explain why some firms succeed in scaling circularity while others remain trapped in pilot initiatives. Figure 2 illustrates the interaction between enablers, barriers, and the expected impacts of the CE in the plastic packaging industry, as outlined in the literature.

Figure 2.

Interaction matrix between Enablers, Barriers, and Expected Impacts.

Therefore, the literature consistently identifies the plastic packaging sector as both a hotspot of environmental impact and a frontier for circular innovation. Yet, research has traditionally segmented its analysis into barriers or enablers, failing to capture their interdependent dynamics. This omission constrains theoretical development and leads to fragmented practical strategies. The present study contributes by advancing an integrative framework that situates enablers and barriers within a systemic model of interaction by analyzing how regulatory, technological, and supply chain enablers interact with corresponding barriers, producing both synergies and tensions.

4. Case-Based Findings

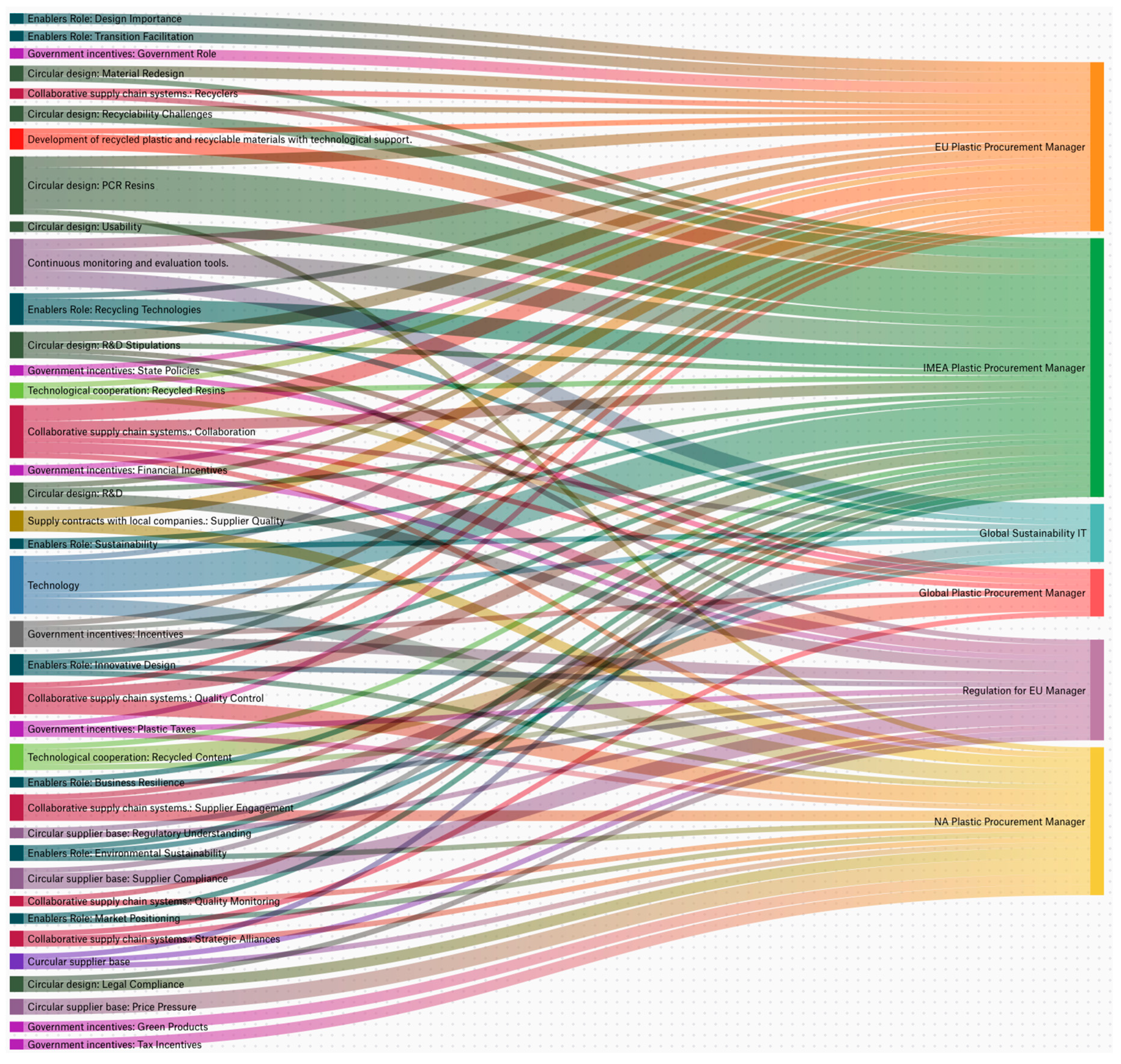

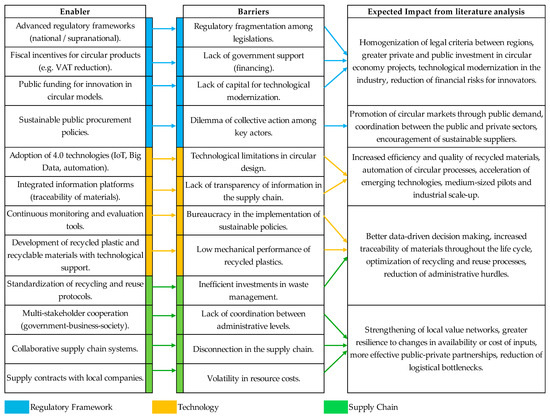

The results of the case study are organized into three major domains, which are regulatory, technological, and supply chain dynamics. They collectively capture the systemic interaction of enablers and barriers to circularity in plastic packaging. Each subsection presents empirical findings from the case study, supported by interview data, documentary analysis, and institutional sources. Figure 3 illustrates the key enablers identified through the analysis of interviews of the case study, showing how regulatory frameworks, technological innovations, and supply chain practices interact to accelerate circular packaging transitions.

Figure 3.

Key Enablers for CE in Plastic Packaging.

4.1. Regulatory Dynamics

In the EU, the introduction of taxes on virgin plastics and incentives for PCR use have created significant momentum toward substitution of virgin feedstock [79,80]. These instruments reduced the cost gap between virgin and recycled plastics, thereby strengthening the business case for circular packaging. However, results also revealed that incentives were effective only when accompanied by clear technical standards and reliable supply of recycled materials [65]. Without synchronized infrastructure, fiscal measures risk producing inflationary effects, as higher demand for limited PCR supplies drove up prices [84].

The case study confirmed the positive role of deposit-refund systems and EPR schemes. In countries such as Germany and the Netherlands, EPR not only mandated producer responsibility for end-of-life packaging but also fostered collaboration with municipalities and recyclers [34,57,69]. These schemes created closed-loop systems where packaging waste returned to the company through reverse logistics networks [56,63,75,132]. However, in emerging markets, weak enforcement and limited institutional capacity hindered the practical effectiveness of EPR, which often remained symbolic rather than transformative. This discrepancy underscores the regulatory fragmentation that multinationals face when operating across diverse jurisdictions [31].

Building on the analysis of taxation and incentives, the case also highlighted the role of regulatory harmonization. Within the EU, consistent standards provided stable conditions for investment and innovation. Conversely, in fragmented regulatory environments, varying definitions of recyclability and recycled content created compliance uncertainty and increased costs. The company frequently faced the need to redesign packaging to meet divergent requirements, reducing efficiency and slowing progress. Within the EU, aligned regulations created predictable environments for investment in circular technologies. In contrast, in markets where standards were inconsistent, such as differing definitions of “recyclable” packaging, the company faced duplicated compliance costs and uncertainty. This finding aligns with broader research stressing that regulatory coherence is indispensable for circular scaling [32,34].

4.2. Technological Dynamics

The analysis revealed that investment in recycling infrastructure is critical to realizing circular packaging. In advanced economies, interviewees reported growing access to mechanical and chemical recycling facilities capable of processing higher volumes of waste with improved efficiency. However, in many emerging economies, lack of infrastructure remains a severe barrier. This disparity produced regional inequalities, forcing the company to rely on virgin plastic imports in less developed markets, undermining its global CE commitments.

In addition to recycling infrastructure, another technological enabler was design for recyclability. The company implemented initiatives such as resin standardization, simplification of packaging layers, and elimination of non-recyclable additives significantly improved recyclability [74]. Company reports highlighted initiatives such as switching from multi-layer composites to mono-material films, which facilitated material recovery and reduced contamination rates [66]. Circular design was also linked to eco-labeling strategies that communicated recyclability to consumers. However, adoption faced internal challenges such as aligning design innovation with marketing requirements often created trade-offs, as brand differentiation sometimes depended on complex, less recyclable packaging formats [58,67].

Interviewees highlighted the issue of PCR quality as both a barrier and a technological frontier. While advances in chemical recycling improved resin purity, consistent quality remained difficult to guarantee across markets. Managers noted that food-contact applications in particular required stringent performance standards that many PCR suppliers could not meet. While chemical recycling technologies offered promising solutions, their scalability and cost competitiveness remained uncertain. This finding reflects prior scholarship on technological bottlenecks in recycled plastics [40,76].

4.3. Supply Chain Dynamics

A decisive element for the effective implementation of circular practices lies in the establishment of collaborative alliances between actors in the supply chain [73]. The data obtained from the interviews reveal that local supply contracts were a critical enabler of circularity. By sourcing PCR locally, the company reduced exposure to volatile international markets and minimized transport-related emissions. Localized contracts also strengthened relationships with regional recyclers, creating mutually beneficial ecosystems. However, these arrangements depended on reliable local partners. In markets with informal recycling sectors, establishing trust and ensuring quality standards were ongoing challenges.

Digital technologies emerged as a central enabler of supply chain circularity [68]. Blockchain-based traceability platforms enabled the company to track material flows from collection to reintegration, ensuring compliance with regulatory requirements and building consumer trust [60]. Nevertheless, their effectiveness depended on integration with broader regulatory and market systems, including standardized disclosure requirements and harmonized eco-labeling.

Despite technological advances and policy incentives, consumer perceptions remained a persistent barrier [81]. Interviewees stressed that skepticism regarding recycled plastics, particularly in food-contact packaging, limited consumer acceptance. Negative perceptions were linked to concerns about hygiene, safety, and product performance. Consumer behavior also displayed inertia since willingness to pay for sustainable packaging was inconsistent across markets, often constrained by socio-economic conditions. These findings confirm literature identifying consumer acceptance as a critical determinant of CE adoption [11,71].

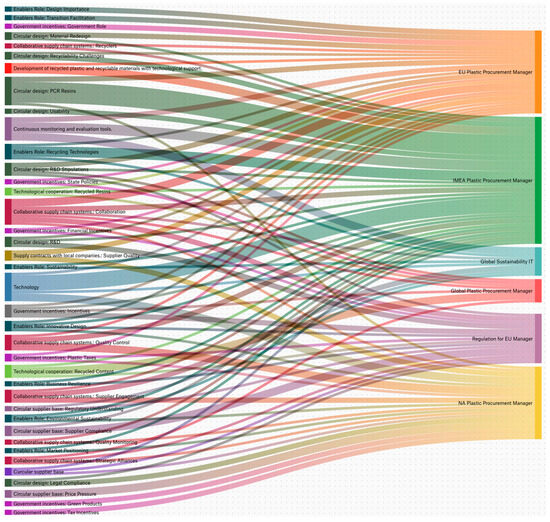

4.4. Persistent Barriers

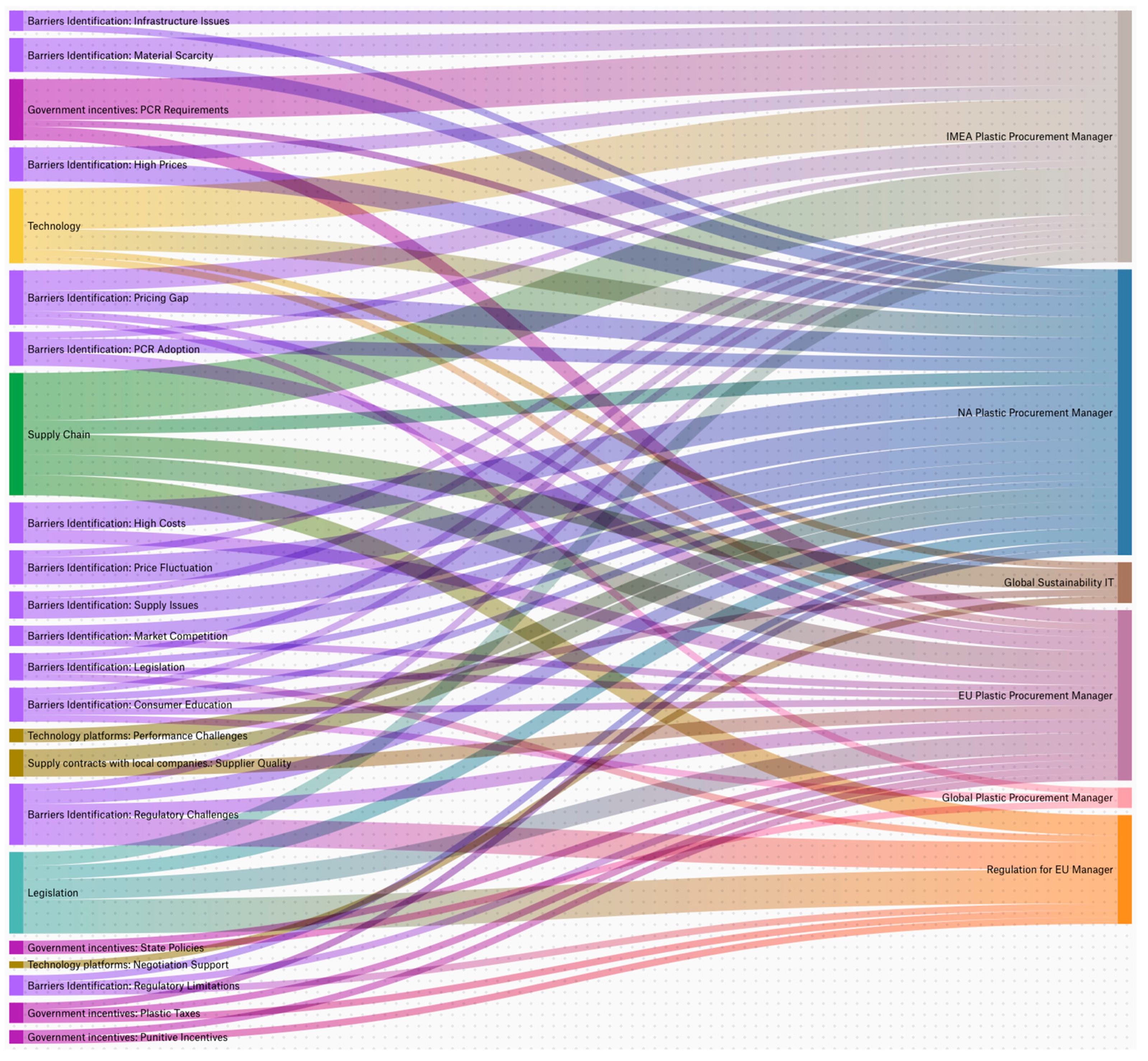

Figure 4 summarizes the key barriers identified in the analysis of interviews, emphasizing the persistence of consumer-related challenges and PCR quality issues alongside infrastructural and regulatory fragmentation. While regulatory, technological, and supply chain enablers created important pathways toward circularity, several barriers remained unresolved. Regulatory fragmentation continued to pose significant challenges. Although harmonization within the EU provided a predictable framework for investment and innovation, the coexistence of inconsistent definitions and standards across international markets generated uncertainty and duplicative compliance costs. At the technological level, bottlenecks also constrained progress.

Figure 4.

Key Barriers for CE in Plastic Packaging.

The absence of advanced recycling facilities in many regions limited the global scalability of PCR adoption, while variability in material quality, particularly in food-contact applications where strict safety standards apply, restricted substitution of virgin plastics. In addition, consumer perceptions emerged as a critical barrier that proved resistant to change. Negative views of recycled packaging, often associated with concerns about safety, hygiene, and performance [44,70], continued to weaken demand-side adoption despite advances in technology and regulation. Taken together, these barriers illustrate that enablers alone are insufficient; their effectiveness depends on systemic alignment across multiple dimensions.

Likewise, effective recycling of plastic packaging requires addressing both technological and behavioral dimensions. On the one hand, consumer motivation improves significantly when accurate information and financial incentives are provided, while confusion about packaging materials remains one of the most severe hindrances to correct sorting behavior [72]. On the other hand, advances in identification and sorting technologies are essential to improve recycling quality and achieve higher recovery rates [62]. Furthermore, cultural factors also shape recycling practices, as citizen behavior is strongly influenced by national contexts, underscoring the need for solutions tailored not only to legislation but also to cultural attitudes toward waste [75].

Findings also demonstrated variation in the prioritization of CE practices depending on managerial role and regional context. Figure 5 presents the distribution of CE practices by managerial role identified in the analysis of interviews, showing how responsibilities and regional contexts shape the emphasis on different enablers and strategies. It is shown that the Procurement Manager for India, Middle East, and Africa (IMEA) engages with the widest range of best practices, such as partnerships, responsible usage, and recyclable technology, reflecting the need for adaptive, multifaceted strategies in regions with less developed recycling infrastructure. In addition to the region’s advanced regulatory landscape, the EU Procurement Manager emphasizes the importance of design for recycling, the use of PCR, and chemical recycling.

Figure 5.

Distribution of CE Practices by Managerial Role.

The EU Manager Regulation, meantime, gives sustainability roadmaps and innovation top priority, implying a more strategic, compliance-oriented viewpoint. The Global Sustainability IT function plays a cross-cutting role by linking leadership, digital tools, and traceability, echoing the enabling role of technology emphasized by Hsu et al. [120]. This distribution of practices demonstrates that the implementation of CE practices is context-dependent and requires support from coherent, cross-functional coordination, particularly in multinational environments with diverse regulatory and operational challenges. The importance of localized strategies in implementing CE practices engages the audience in the process.

5. Discussion

The findings of this study extend the existing literature by demonstrating that enablers and barriers in the CE cannot be understood as isolated categories but rather as interdependent dynamics. Consequently, supply chain cooperation, technological innovation, and regulatory coherence must interact for CE strategies to be successfully implemented in the plastic packaging industry. The study reveals that circular transitions are complex, interconnected processes that require the concurrent involvement of multiple enablers to address systemic obstacles and challenges by integrating empirical data from semi-structured interviews with established theoretical frameworks.

A significant finding highlights the catalytic role of harmonized regulatory frameworks. Interview data corroborate that fiscal instruments, such as levies on virgin plastics and subsidies for PCR content, directly stimulate investments in recycling infrastructure and process modernization. The empirical results support the claims made by Del Vecchio et al. [37] and Mura et al. [32] that well-designed regulatory frameworks serve two purposes: they enhance market predictability and improve company competitiveness. However, by recognizing regulatory inconsistency, which is especially severe in developing markets as a crucial moderating element, this study builds on earlier studies. In addition to reducing the effectiveness of policies, this inconsistency makes inequities in the adoption of circular practices worse.

Concurrently, technological enablers emerged as indispensable, particularly in the context of Industry 4.0 applications, including AI-enhanced sorting, blockchain-enabled traceability, and advanced polymer modeling. These innovations demonstrably enhance material circularity while mitigating persistent challenges associated with PCR quality variance and contamination, resonating with observations by Cimpan et al. [40] and Maione et al. [34]. The research reveals a significant contingency: Technological deployment efficacy is intrinsically tied to regional infrastructural maturity and capital accessibility. This finding critically nuances earlier propositions [39] by highlighting the contextual limitations often overlooked in assumptions of universal applicability. The role of technology in enhancing circularity is a promising aspect of the future of the plastic packaging industry.

The research further confirms the centrality of supply chain integration, empirically validating theoretical emphasis on multi-actor collaboration and traceability systems [36,108]. A significant contribution lies in identifying localized contractual mechanisms as critical buffers against global volatility in recycled material pricing and quality. It represents a strategic resilience factor aligning with Alshemari et al. [43] advocacy for regionally anchored circular supply chains. This emphasis on supply chain integration gives hope for the robustness of CE initiatives in the face of global difficulties.

Notably, the study elevates the strategic primacy of circular design as a transversal enabler. While prior work has often focused on material aspects [40,58], these findings emphasize the importance of embedding operational design intelligences specifically, AI-driven predictive analytics for upfront assessment of recyclability, carbon impact, and functional compatibility. This facilitates iterative packaging optimization via real-time data feedback, effectively merging design and analytics into a proactive sustainability framework.

A principal theoretical contribution is the systemic exposition of enabler-barrier interdependencies, which aligns with the work of Qazi and Appolloni [128] and Munaro and Tabares [130]. These scholars describe how interconnected barriers will be eliminated or minimized successively through the enablers identified for circular procurement management and stakeholder perspectives, respectively. Contrasting models treating barriers and enablers in isolation [12,31,35,36], this work demonstrates that barriers and enablers are mutually constitutive through dynamic feedback mechanisms. Regulatory instruments, for instance, achieve practical impact only when synchronized with technological readiness and supply chain capabilities. Design interventions and supply chain transparency may significantly decrease consumer resistance, which is frequently perceived as external. Demand-side difficulties can be viewed as manageable problems using this method.

Beyond corporate and regulatory measures, consumer engagement remains a cornerstone of effective circular transitions, which may differ substantially across regions and industries [133,134]. Individuals can contribute by improving waste-sorting accuracy [66], purchasing products packaged in recyclable or reusable materials [98], and participating in local take-back or deposit–return systems [67]. Access to clear information and eco-labeling significantly enhances this participation, aligning consumer choices with corporate and policy-driven circular strategies [72]. Such everyday actions complement organizational efforts, strengthening the multilevel integration necessary for a fully circular plastics economy.

These insights hold significant implications for the central multinational corporation. Given its broad international operations, the company needs to implement regionally specific CE strategies. This entails building local capacity and forming local partnerships in emerging markets. On the other hand, design innovation and digitization should be the primary priorities in developed economies. According to the adaptive governance paradigm by WEF [2], which promotes flexible and context-specific governance structures that can adjust to the shifting demands of the CE, this data supports a modular strategy that supports the company’s approach to context-sensitive circularity transitions.

Taken together, the results and their contrast with prior research support the argument that CE in plastic packaging is not a matter of simply adding more enablers or removing more barriers, but of understanding and managing their systemic interplay. Regulatory enablers such as taxation and EPR succeed only when synchronized with infrastructural readiness and market incentives. Technological innovations, including chemical recycling and digital traceability, achieve meaningful impact only when supported by coherent policies and reinforced by consumer trust.

Likewise, supply chain collaboration plays a stabilizing role in material flows, but it requires regulatory harmonization and governance mechanisms that fairly distribute responsibilities among actors. This synthesis highlights the need for an integrated framework of circular transition, where progress depends not on the isolated strength of enablers but on their capacity to neutralize, transform, or align with barriers. By conceptualizing barriers not as obstacles to be eradicated but as conditions that can stimulate innovation when confronted with enablers, the study reframes CE as a process of dialectical transformation.

6. Conclusions

This study investigated how enablers can overcome barriers to the CE in plastic packaging within multinational companies. By integrating a systematic review with a case study of a leading global firm, the research demonstrated that circular transitions are not achieved by simply accumulating more enablers or eliminating barriers but rather by managing their interdependent dynamics. The results show that regulatory measures, technological advances, and supply chain collaborations can foster circularity, yet their effectiveness depends on temporal synchronization, infrastructural readiness, and stakeholder integration.

Theoretically, the study reframes CE transitions as dialectical and non-linear processes in which barriers are not merely obstacles but conditions that, when confronted with enablers, stimulate innovation. This conceptualization advances transition studies by introducing synchronization and sequencing as critical dimensions of analysis. The research highlights strategies such as strengthening EPR schemes, investing in design-for-recycling and digital traceability, and orchestrating supply chain collaborations as actionable pathways for multinationals navigating fragmented regulatory environments. From a policy perspective, the findings emphasize the need for harmonized frameworks that integrate fiscal instruments, infrastructure investment, and consumer awareness measures, particularly in emerging markets where gaps remain acute.

This study contributes to both scholarship and practice by providing a systemic framework for understanding how barriers and enablers interact in plastic packaging. By demonstrating that circularity emerges from the capacity to align, transform, and sometimes even repurpose barriers through enablers, it offers a roadmap for accelerating circular transitions in complex, multinational contexts.

Despite these contributions, several limitations should be acknowledged. The study relied on a single case, which constrains the generalizability of the findings. Moreover, the analysis reflects conditions at the time of data collection, while regulatory and technological landscapes continue to evolve rapidly. Building on these limitations, future research should expand comparative case studies across multiple industries, apply quantitative methods to measure the relative weight of specific enablers and barriers, and explore consumer behavior through cross-cultural analyses. Further work could also evaluate the scalability of emerging recycling technologies and assess the effectiveness of integrated policy packages, including harmonized eco-labeling and digital product passports.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.B., A.L.-P. and J.A.C.; methodology, D.B. and A.L.-P.; software, D.B. and A.L.-P.; validation, J.A.C. and S.W.; formal analysis, D.B., A.L.-P. and J.A.C.; investigation, D.B., A.L.-P., J.A.C. and S.W.; resources, S.W.; data curation, D.B., A.L.-P. and J.A.C.; writing—original draft preparation, D.B., A.L.-P. and J.A.C.; writing—review and editing, J.A.C. and S.W.; visualization, D.B.; supervision, A.L.-P. and J.A.C.; project administration, D.B., A.L.-P. and J.A.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to national and international data protection legislation in both Germany and Colombia, as the research did not involve the collection of sensitive personal data and all data were anonymized prior to analysis.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| CE | Circular Economy |

| EMF | Ellen MacArthur Foundation |

| EPR | Extended Producer Responsibility |

| EU | European Union |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| PCR | Post-consumer Recycled Material |

| PET | Polyethylene Terephthalate |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| WBCSD | World Business Council for Sustainable Development |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Questions for semi-structured interview.

Table A1.

Questions for semi-structured interview.

| Category | Variable | Enabler | Barrier | Expected Impact | Questions | Intention of the Question |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regulatory framework | Divergent regulatory frameworks | Advanced regulatory frameworks (national/supranational). | Regulatory fragmentation among legislations. | Homogenization of legal criteria between regions, greater private and public investment in CE projects, technological modernization in the industry, and reduction in financial risks for innovators. | In what concrete ways does executive leadership support implementing circular criteria manifest itself, and how does this impact on their ability to overcome local or global regulatory barriers? | Identify internal governance mechanisms and their alignment with external regulatory frameworks. |

| Government incentives | Fiscal incentives for circular products (e.g., VAT reduction). | Lack of government support (financing). | What public policies and public incentives (e.g., REPs, virgin plastic taxes) have been key to accelerating your circularity goals, and how could they be improved to be more effective, and which of these public policies are geared towards technological transformation? | Detect opportunities for regulatory advocacy and public–private collaboration. | ||

| Public funding for innovation in circular models. | Lack of capital for technological modernization. | |||||

| Procurement policies | Sustainable public procurement policies. | Dilemma of collective action among key actors. | Promotion of circular markets through public demand, coordination between the public and private sectors, encouragement of sustainable suppliers. | What tools or methodologies do you use to assess the circular performance of suppliers in environments with divergent regulations (e.g., EU vs. APAC), and how do you adapt your criteria? | Explore strategies to harmonize standards in global chains. | |

| Technology | Circular design | Adoption of 4.0 technologies (IoT, Big Data, automation). | Technological limitations in circular design. | Increased efficiency and quality of recycled materials, automation of circular processes, acceleration of emerging technologies, medium- sized pilots and industrial scale- up. | How are you integrating 4.0 technologies, such as IoT for material traceability, Big Data to optimize resource use and automation in key processes, into the circular design of your plastic packaging? What specific technical constraints (e.g., material compatibility, lack of standards for recyclability) have hindered the implementation of these systems to ensure 100% circular and scalable designs? | Map technology adoption and implementation gaps. |

| Technology platforms | Integrated information platforms (traceability of materials). | Lack of transparency of information in the supply chain. | What platforms with specific metrics (e.g., % recycled content, reuse rate) do you use to demonstrate the value of circular purchasing to customers and investors, and how do you communicate them? | Identify persuasive technologies and KPIs to gain internal/external support. | ||

| Continuous monitoring and evaluation tools. | Bureaucracy in the implementation of sustainable policies. | Better data-driven decision making, increased traceability of materials throughout the life cycle, optimization of recycling and reuse processes, reduction in administrative hurdles. | ||||

| Technological cooperation | Development of recycled plastic and recyclable materials with technological support. | Low mechanical performance of recycled plastics. | What incentives and technical support do you offer suppliers to adopt recyclable materials or circular processes to ensure more efficient waste management and how do you measure their impact on the value chain? | Identify models of technological cooperation with suppliers. | ||

| Supply Chain | Standardization of recycling and reuse protocols. | Inefficient investments in waste management. | ||||

| Collaboration models and systems | Multi-stakeholder cooperation (government- business-society). | Lack of coordination between administrative levels. | Strengthening of local value networks, greater resilience to changes in availability or cost of inputs, more effective public- private partnerships, and reduction in logistical bottlenecks. | What strategic alliances (e.g., consortia, long-term contracts) have you established with suppliers or recyclers to ensure stable flows of recycled materials, and what challenges remain? | Analyze successful collaboration models and residual obstacles. | |

| Collaborative supply chain systems. | Disconnection in the supply chain. | |||||

| Circular supplier base | Supply contracts with local companies. | Volatility in resource costs. | How do you address the limited supply of suppliers with circular criteria? Have you developed training or incentive programs to transform traditional suppliers? | Explore strategies to scale the circular supplier base. |

Appendix B

Semi-Structured Interview Guide

Introduction: The circular economy emerges as a strategic alternative to the linear production model, especially in sectors with high-impact sectors such as plastic packaging. This research focuses on analyzing how companies can overcome technological, regulatory, and logistical barriers by leveraging key enablers, such as technological innovation, public policies, and supply chain collaboration. The objective is to identify practical strategies that promote progress toward more sustainable, scalable, and circular packaging models. Understanding that the Circular Economy refers to:

“The circular economy is a system where materials never become waste and nature is regenerated. In a circular economy, products and materials are kept in circulation through processes like maintenance, reuse, refurbishment, remanufacture, recycling, and composting. The circular economy tackles climate change and other global challenges, like biodiversity loss, waste, and pollution, by decoupling economic activity from the consumption of finite resources.”–Ellen McArthur Foundation.

Interview Objective: Gather detailed information on how the selected multinational company implements circular strategies to overcome regulatory, technological, and supply chain barriers in the plastic packaging sector.

- Opening Questions

- Can you briefly describe your role at the multinational company and explain how it relates to the company’s circular economic initiatives?

- What does circularity mean for the company, and how is it integrated into its strategy?

- How would you describe the main internal and external drivers pushing the company toward circular packaging?

- Thematic Areas and Questions

Institutional and Regulatory Support

- In what ways do various global regulations hinder the organization from achieving its circular goals? What internal governance mechanisms does the organization have in place to align with different regulatory frameworks?

- Which public policies and incentives (e.g., extended producer responsibility (EPR) and virgin plastic taxes) have been key to accelerating your circularity goals, and how could they be improved for greater effectiveness? Which of these policies aim to transform technology?

- What tools or methodologies do you use to assess the circular performance of suppliers in regions with different regulations (e.g., the EU versus APAC), and how do you adapt your criteria?

Enabling Technologies and Technological Limitations

- How are you integrating Industry 4.0 technologies, such as the Internet of Things (IoT) for material traceability, big data to optimize resource use, and automation in key processes, into the circular design of your plastic packaging?

- What specific technical limitations (e.g., material compatibility, lack of recyclability standards) have hindered the implementation of these systems to ensure 100% circular and scalable designs?

- What platforms with concrete metrics (e.g., percentage of recycled content, reuse rate) do you use to demonstrate the value of circular purchases to clients and investors, and how do you communicate these metrics?

Circular Performance Assessment and Supplier Relations

- What incentives and technical support do you offer suppliers to encourage the adoption of recyclable materials and circular processes for more efficient waste management? How do you measure their impact on the value chain? How do you address the limited number of suppliers that meet circular criteria? Have you developed training programs or incentives to encourage traditional suppliers to adopt circular practices?

- What strategic partnerships have you established with suppliers or recyclers to ensure a stable flow of recycled materials? For example, have you formed consortia or long-term contracts? What challenges persist?

- End-of-Interview Questions

- In your opinion, what has been the most impactful enabler or initiative in advancing circular packaging at the multinational company?

- Is there anything else you think is important for understanding the company’s journey toward circular packaging that we haven’t discussed?

References

- WBCSD. Vision 2050: Time to Tansform; The World Business Council For Sustainable Development: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- WEF. The Global Risks Report 2023, 18th ed.; Insight Report; The World Economic Forum: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- MahmoumGonbadi, A.; Genovese, A.; Sgalambro, A. Closed-loop supply chain design for the transition towards a circular economy: A systematic literature review of methods, applications and current gaps. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 323, 129101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victoria, F.; Ananthanarayanan, A.; Brandon, A.; Baechler, B.; Cecchini, E.; Baziuk, J.; Hegdahl, R.; Mallos, N. An opportunity to end plastic pollution: A global international legally binding instrument. Perspectives 2023, 44, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Di Foggia, G.; Beccarello, M. An overview of packaging waste models in some european countries. Recycling 2022, 7, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogt Jacobsen, L.; Pedersen, S.; Thøgersen, J. Drivers of and barriers to consumers’ plastic packaging waste avoidance and recycling—A systematic literature review. Waste Manag. 2022, 141, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Statista FMCG Company Plastic Packaging Volumes. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1167204/volume-plastic-packaging-used-select-companies-globally/ (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Farooque, M.; Zhang, A.; Liu, Y.; Hartley, J.L. Circular supply chain management: Performance outcomes and the role of eco-industrial parks in China. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2022, 157, 102596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jambeck, J.R.; Geyer, R.; Wilcox, C.; Siegler, T.R.; Perryman, M.; Andrady, A.; Narayan, R.; Law, K.L. Plastic waste inputs from land into the ocean. Science 2015, 347, 768–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betts, K.; Gutierrez-Franco, E.; Ponce-Cueto, E. Key metrics to measure the performance and impact of reusable packaging in circular supply chains. Front. Sustain. 2022, 3, 910215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EMF. The Rise of Single-Use Plastic Packaging Avoiders. Available online: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/articles/the-rise-of-single-use-plastic-packaging-avoiders (accessed on 18 March 2025).

- Allison, A.L.; Lorencatto, F.; Michie, S.; Miodownik, M. Barriers and enablers to buying biodegradable and compostable plastic packaging. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthos, D.; Walker, T.R. International policies to reduce plastic marine pollution from single-use plastics (plastic bags and microbeads): A review. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2017, 118, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Comission European Comission—Plastics. Available online: https://environment.ec.europa.eu/topics/plastics_en (accessed on 23 May 2025).

- European Parliament Regulation (EU) 2025/40 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 19 December 2024 on Packaging and Packaging Waste. 2024. Volume 40. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2025/40/oj/eng (accessed on 18 March 2025).

- WBCSD. Circular Economy and Environmental Priorities for Business; The World Business Council For Sustainable Development: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- WBCSD. Circular Transition Indicators V4.0: Metrics for Business, by Business; The World Business Council For Sustainable Development: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- EMF. The Business Opportunity of a Circular Economy; Springer: Singapore, 2020; ISBN 978-981158510-4/978-981158509-8. [Google Scholar]

- EMF. Circulytics: Weighting and Scoring Approach; The World Economic Forum: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, M.; Yan, X.; Mustafee, N.; Charnley, F.; Böhm, S.; Pascucci, S. Going beyond waste reduction: Exploring tools and methods for circular economy adoption in small-medium enterprises. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 182, 106345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz-Mönninghoff, M.; Neidhardt, M.; Niero, M. What is the contribution of different business processes to material circularity at company-level? A case study for electric vehicle batteries. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 382, 135232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Primadasa, R.; Tauhida, D.; Christata, B.R.; Rozaq, I.A.; Alfarisi, S.; Masudin, I. An investigation of the interrelationship among circular supply chain management indicators in small and medium enterprises. Supply Chain Anal. 2024, 7, 100068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carissimi, M.C.; Creazza, A.; Pisa, M.F.; Urbinati, A. Circular economy practices enabling circular supply chains: An empirical analysis of 100 SMEs in Italy. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2023, 198, 107126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Costa Fernandes, S.; Rozenfeld, H. Business model innovation through the design of circular product-service system value propositions: A method proposal. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2024, 33, 5325–5345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat Persons Employed in Circular Economy Sectors. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/cei_cie011/default/table?lang=en (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- WWF. What is the Circular Economy of Plastic? Available online: https://www.wwf.org.co/?375812/En-que-consiste-la-economia-circular-del-plastico (accessed on 9 May 2025).

- EMF. Towards the Circular Economy Vol. 3: Accelerating the Scale-Up Across Global Supply Chains; The World Economic Forum: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Dev, N.K.; Shankar, R.; Qaiser, F.H. Industry 4.0 and circular economy: Operational excellence for sustainable reverse supply chain performance. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 153, 104583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taddei, E.; Sassanelli, C.; Rosa, P.; Terzi, S. Circular supply chains theoretical gaps and practical barriers: A model to support approaching firms in the era of industry 4.0. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2024, 190, 110049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taddei, E.; Sassanelli, C.; Rosa, P.; Terzi, S. Circular supply chains in the era of industry 4.0: A systematic literature review. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 170, 108268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paletta, A.; Leal Filho, W.; Balogun, A.L.; Foschi, E.; Bonoli, A. Barriers and challenges to plastics valorisation in the context of a circular economy: Case studies from Italy. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 241, 118149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mura, M.; Longo, M.; Zanni, S. Circular economy in Italian SMEs: A multi-method study. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 245, 118821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchherr, J.; Piscicelli, L.; Bour, R.; Kostense-Smit, E.; Muller, J.; Huibrechtse-Truijens, A.; Hekkert, M. Barriers to the circular economy: Evidence from the European Union (EU). Ecol. Econ. 2018, 150, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maione, C.; Lapko, Y.; Trucco, P. Towards a circular economy for the plastic packaging sector: Insights from the Italian case. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 34, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizos, V.; Behrens, A.; van der Gaast, W.; Hofman, E.; Ioannou, A.; Kafyeke, T.; Flamos, A.; Rinaldi, R.; Papadelis, S.; Hirschnitz-Garbers, M.; et al. Implementation of circular economy business models by small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs): Barriers and enablers. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jesus, A.; Mendonça, S. Lost in transition? Drivers and barriers in the eco-innovation road to the circular economy. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 145, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Vecchio, P.D.; Urbinati, A.; Kirchherr, J. Enablers of managerial practices for circular business model design: An empirical investigation of an agro-energy company in a rural area. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2024, 71, 873–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchherr, J.; Reike, D.; Hekkert, M. Conceptualizing the circular economy: An analysis of 114 definitions. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 127, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bressanelli, G.; Adrodegari, F.; Perona, M.; Saccani, N. The role of digital technologies to overcome Circular Economy challenges in PSS Business Models: An exploratory case study. Procedia CIRP 2018, 73, 216–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimpan, C.; Iacovidou, E.; Rigamonti, L.; Thoden van Velzen, E.U. Keep circularity meaningful, inclusive and practical: A view into the plastics value chain. Waste Manag. 2023, 166, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bułkowska, K.; Zielinska, M.; Bułkowski, M. Blockchain-Based Management of Recyclable Plastic Waste. Energies 2024, 17, 2937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogutu, M.O.; Akor, J.; Mulindwa, M.S.; Heshima, O.; Nsengimana, C. Implementing circular economy and sustainability policies in Rwanda: Experiences of Rwandan manufacturers with the plastic ban policy. Front. Sustain. 2023, 4, 1092107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshemari, A.; Breen, L.; Quinn, G.; Sivarajah, U. Towards a Sustainable solution: The barriers and enablers in adopting circular economy principles for medicines waste management in UK and Kuwaiti hospitals. Circ. Econ. Sustain. 2025, 5, 2495–2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinrich, R.; Mielinger, E.; Krauter, V.; Arranz, E.; Camara Hurtado, R.M.; Marcos, B.; Poças, F.; de Maya, S.R.; Herbes, C. Decision-making processes on sustainable packaging options in the European food sector. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 434, 139918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulindwa, M.S.; Akor, J.; Auta, M.; Nijman-Ross, E.; Ogutu, M.O. Assessing the circularity status of waste management among manufacturing, waste management, and recycling companies in Kigali, Rwanda. Front. Sustain. 2023, 4, 1215554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venugopal, E.; Patil, S.J.; Naidu, S.B.K. Textile waste: Management, sustainability and recycling technologies. In Solid Waste Management: A Roadmap for Sustainable Environmental Practices and Circular Economy; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany; Department of Biotechnology, Kongunadu Arts and Science College: Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu, India, 2025; pp. 237–261. ISBN 978-303178420-0/978-303178419-4. [Google Scholar]

- Beccarello, M.; Di Foggia, G. Economic analysis of EU strengthened packaging waste recycling targets. J. Adv. Res. Law Econ. 2016, 7, 1930–1941. [Google Scholar]

- Turunen, T.; Mateo, E.R.; Alaranta, J. Regulatory catalysts for the circular economy. In The Routledge Handbook of Catalysts for a Sustainable Circular Economy; Lehtimäki, H., Aarikka-Stenroos, L., Ari Jokinen, P.J., Eds.; Taylor and Francis: Abington, UK, 2023; pp. 169–186. ISBN 978-100097141-5/978-103221244-9. [Google Scholar]

- AlJaber, A.; Martinez-Vazquez, P.; Baniotopoulos, C. Barriers and enablers to the adoption of circular economy concept in the building sector: A systematic literature review. Buildings 2023, 13, 2778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WEF. Gen Z Cares About Sustainability More Than Anyone Else—And Is Starting to Make Others Feel the Same Way. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/stories/2022/03/generation-z-sustainability-lifestyle-buying-decisions/ (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- De Waal, I.M. The legal transition towards a more circular plastic packaging chain: A case study of the Netherlands. Eur. Energy Environ. Law Rev. 2023, 32, 226–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research, 5th ed.; SAGE Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]