Abstract

High-speed rail (HSR) makes a significant contribution to green innovation (GI), thereby supporting high-quality economic development. However, prior studies have mainly focused on the impact of HSR on regional innovation, ignored the influence on GI from the micro perspective, as well as the mechanism through which HSR affect GI. Using the data from manufacturing companies listed in Shanghai and Shenzhen stock exchanges during the period of 2004 to 2023, we treat HSR as a quasi-natural experiment and employ a multi-period difference-in-difference (DID) approach to explore the effect of HSR on GI. The regression results are presented as follows. (1) HSR significantly enhances GI in enterprises, and the results still hold after several robust checks. (2) HSR has a greater impact on the improvement of GI in lightly polluting SOEs of developed cities. (3) The mechanism by which HSR can improve GI is to promote the mobility of talent and alleviate financing constraints faced by enterprises. The policy recommendation is to focus on the heterogenous effect on GI in enterprises to promote the ability of sustainable development.

1. Introduction

With the acceleration of global climate governance and the sustainable development agenda, research on the green innovation (GI) of enterprise is receiving increasing attention. GI is an innovative activity that reduces the negative impact of human activities on the ecological environment while improving resource utilization efficiency. In China specifically, coal consumption reached 4.48 billion tons in 2022, accounting for 56% of total energy consumption(The data sources from National Bureau of Statistics website, https://data.stats.gov.cn/easyquery.htm?cn=C01 (accessed on 18th October 2025), which has brought severe environmental issues, and thereby forced enterprises to shift toward green and low-carbon development. In the era of Industry 4.0., GI is regarded as a critical catalyst for sustainable development [1], and thus enterprises are encouraged to improve their GI.

The determinants of innovation have been a hot topic among scholars given that innovation is of great significance to the competitiveness of enterprises and economic growth [2,3,4]. As asserted in the literature, environmental regulatory pressures [5,6], foreign trade activities [7,8], R&D activities [9], enterprise size [10], and the characteristics of executives [11] affect GI. In addition, a stream of studies have agreed that the mobility of innovative factors [12,13] and further induced agglomeration [14,15,16] contribute to innovation. Notably, these factors are restricted by distance, which is closely associated with transportation infrastructure, especially HSR. As defined, HSR has been widely recognized as an innovative mode of transportation, with its technology playing a significant role in resource allocation and operational performance [17,18]. In addition, the most obvious advantage of HSR is its high speed. The designed speed of China’s HSR ranges from 250 km/h to 350 km/h, which is approximately 5–7 times that of conventional railways. Thus, HSR generates a “spatio-temporal compression” effect and greatly improves accessibility [19,20,21,22], further improving the mobility of talent [21,23].

In light of this, there has been extensive study on the relationship between transportation infrastructure and innovation. For instance, Zeng et al. (2025) found that transportation infrastructure enhanced the quantity and quality of corporate innovation by affecting market integration [24]. Mao et al. (2024) provided evidence that transportation infrastructure facilitated innovation output through knowledge spillover [25]. Cui and Tang (2023) conducted an empirical study in various provinces in China and found that transportation infrastructure has a significant positive effect on innovation capability [26]. In addition, with the opening of China–Europe Railway Express, attention has turned to the effect of international railway corridors [27,28].

Overall, to the best of our knowledge, the studies regarding the impact of HSR on GI have been insufficient. On the one hand, a strain of studies examined the economic and environmental effect of HSR by using GI as a mechanism variable, focusing on elements such as carbon emissions, green productivity, enterprise’s inventory, and so on, while research on the relationship between HSR and GI has been rarely discussed, except for several studies investigating the impact of HSR on GI efficiency or GI output [29,30]. On the other hand, the existing studies mainly focus on regional GI [31,32,33], while the research from the perspective of micro-enterprises is limited.

The large-scale development of HSR in China provides a unique context for this study. In 2004, the “Medium- and Long-Term Railway Network Plan” (hereafter referred to as the “Plan”) was elaborated by the State Council. The main goal of this plan is to complete four vertical (north–south) and four horizontal (east–west) corridors—known as the “4 + 4” network—by the end of 2020, and expand the HSR network to 16,000 km. In 2008, the first HSR system was put into operation. Since then, the HSR program has been accelerated to stimulate the economy. In 2016, the Plan (2016–2030) further outlined a more ambitious blueprint for HSR, with eight vertical and eight horizontal corridors (referred to as the “8 + 8” network), realizing a 1–4 h transportation circle between adjacent cities, and a 0.5–2 h transportation circle within urban agglomerations. In 2020, the National Railway Corporation (NRC) released its latest plan, announcing that by 2035, the length of the HSR network will be expanded to 70,000 km.

Therefore, the purpose of our paper is to explore the effect of HSR on enterprise GI; that is, we aim to analyze whether HSR has a positive or negative impact on enterprise GI. Which types of enterprise gain most benefits from the opening of HSR? And which mechanism does HSR use to affect enterprise GI? To solve the above questions, this study treats HSR as a quasi-natural experiment and employs a multi-period DID approach to explore the heterogeneous effect of HSR on GI in manufacturing companies from 2004 to 2023. The main regression results are presented as follows. (1) HSR significantly improves the level of GI in enterprises, and the results still hold after several robust checks. (2) There exists a significant heterogeneity in different enterprises and cities with regard to ownership, pollution intensity, and economic development. (3) The mechanism by which HSR can improve GI is by promoting the mobility of talent and alleviating financing constraints faced by enterprises.

The contributions of this study are threefold. Firstly, the remarkable development of both HSR and innovation output experienced in recent years in China offers a unique context for this study. Thus, our study adds to the increasing body of literature on the impact of HSR on enterprise GI from the micro-perspective. Secondly, it advances the understanding of the channels through which HSR can affect GI. Prior studies have explored the mechanisms through agglomeration and factor mobility, while this study also finds that HSR alleviates the financing constraints of enterprise and further enhance GI. Thus, this study provides a reference for China’s policy-makers to enhance the level of GI in enterprises. Thirdly, GI is a crucial driving force for the sustainable development of enterprises. Considering the fact that several countries have opened HSR systems, our study sheds light on the innovative development of other countries.

2. Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypotheses

2.1. High-Speed Railway, the Mobility of Human Capital, and Green Innovation

The development of HSR has significantly reduced transportation costs [34] and further reshaped economic geography [35,36]. In particular, the agglomeration and mobility of human capital is one of the critical factors affecting GI, and HSR speeds up the process [37].

Firstly, human capital has innovation awareness [38], while the distribution of human capital is uneven across cities. HSR contributes to the redistribution of human capital and accelerates the capital factor flows from large cities to small cities through a synergy effect [39,40]. Accordingly, human capital quickly adapts to new environments, actively explores innovative methods, and thus increases the development of GI [41].

Secondly, HSR improves the mobility of human capital, leading to the sharing and exchange of knowledge, information, and technology, and further facilitating knowledge spillover and technology spillover [38]. This diffusion occurs mainly via three effects, namely the “learning effect”, “communication effect”, and “imitation effect” [29]. Moreover, the spillover effects are intensified and widened by the expansion of HSR. Thus, the improvement of GI may occur.

Thirdly, HSR contributes to the development of innovative networks. For example, HSR promotes research collaboration of scholars across cities [42], involving the cooperation among the original partners and the cooperation among original unfamiliar scholars [43]. Consequently, the interaction of researchers would produce the positive externalities [16], which have an impact on GI.

Thus, Hypothesis 1 is proposed:

Hypothesis 1.

HSR improves GI by promoting the mobility of human capital.

2.2. High-Speed Railway, Financing Constraints, and Green Innovation

GI usually occurs alongside increasing R&D activity, and thus has a high demand for capital [25], especially for venture capital, which is associated with geographical proximity. With the large-scale construction of an HSR network, HSR shortens traveling time and transportation costs, which may alleviate the financing problems faced by enterprises, such as high financing costs and information asymmetry issues.

In particular, spatial distance exerts certain information costs and transaction costs, which are generated by information asymmetry. For instance, information collection, communication, and supervision are more difficult as the distance increases. Brown et al. (2009) found that a lack of transparency regarding information makes it difficult for investors to evaluate the value of these projects in the innovation process [44], increasing the financial constraints of enterprises. Mao et al. (2024) argued that R&D outputs have inherent uncertainty, making it difficult to effectively monitor the level of effort of innovators [25]. In light of this, adverse selection and moral hazard emerge in the process of financing for GI, which force investors to pursue a high-risk premium, and have a negative impact on financing efficiency.

However, HSR greatly improves accessibility, thereby expanding the market radiation radius and broadening the financing channel. On the other hand, HSR facilitates face-to-face communication and further reduces information costs and regulatory costs. Furthermore, more capital and financial institutions are attracted to the local market due to the enhancement of infrastructure, improving the financing environment.

Thus, we propose Hypothesis 2, based on the analysis above:

Hypothesis 2.

HSR improves GI by alleviating financing constraints of enterprises.

3. Methodology and Data

3.1. DID Model

In this study, we adopt the DID approach to explore the impact of HSR on GI, which is used to evaluate the treatment effect of policy shock. Notably, the opening time for HSR is continuous; thus, a multi-period DID model is adopted. Specifically, dummy variables are generated for whether a city has HSR or not (treatment group and control group) [45].

According to the abovementioned analysis, Equation (1), with two-way fixed-effects, is presented as follows:

where is the level of green innovation for firm i in year t + 1. is a dummy variable. If this means that the city where the firm i is located has opened an HSR service during the sample period; otherwise, it is 0. The interaction term is our research object, which indicates the net effect of a policy on a firm’s GI. are a set of firm-level control variables that might affect GI. and represent the industry-fixed effect and time-fixed effect, respectively. is the random term.

3.2. Variables and Data

The data in this study come from two aspects, that is, HSR data of prefecture-level cities, and listed manufacturing enterprise data. Specifically, HSR data are mainly collected from the China Railway Passenger Train Timetable (2003–2020), and the firm-level data are from the China Stock Market and Accounting Research (CSMAR) database.

We further processed the sample as follows. (1) When matching HSR data with enterprise data, we use the operational location of the enterprise instead of its registered location. For enterprises with more than one operational location, we choose the first operational location. (2) The green patent is considered to be the number of patents for the next year if the application time for green patents is after 30 June, while the green patent is deemed to be the number of patents for that year if the application time for green patents is before 30 June. (3) The opening time of HSR in a city is defined as the next year if HSR is put into operation after 30 June of that year and the HSR deemed to be opened in that year if HSR is put in service before 30 June of that year. (4) We exclude data from enterprises that have been listed for less than a year, as well as data from enterprises with a book-to-market ratio less than zero, and data of critical independent variables with missing values.

Overall, the data covers a period of 20 years from 2004 to 2023. The definition and summary statistics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

The definition and summary statistics.

4. Empirical Analysis

4.1. Baseline Regression

The data are Winsorized for the full sample of 1% and 99% to eliminate the outliers, and baseline results are listed in Table 2. Column (1) to (3) present the different model specification without control variables, while column (4) to (6) are obtained by increasing the main control variables, respectively. The core independent variable is , and its coefficient is significantly positive in all models, indicating that the enterprise’s GI is improved by the opening of HSR. It should be highlighted that the opening of HSR could enhance corporate green innovation levels by 6.02%, as seen in column (6). Thus, Hypothesis 1 is verified.

Table 2.

Baseline results.

The influence of main control variables is summaries as follows. From column (6), the significantly negative coefficient of and indicates that enterprise with low ownership concentration and start-ups have more efficient GI output. The coefficient of and are significantly positive, indicating that the enterprise with a large-scale, high tangible asset ratio, high operating debt ratio, and high operating efficiency of assets has a higher level of GI.

4.2. Parallel Trend Test

The DID model assumes that the treatment group and control group have a parallel trend. Thus, referring to the method of Jacobson et al. (1993) [46], we carry out the parallel trend test using the event study method.

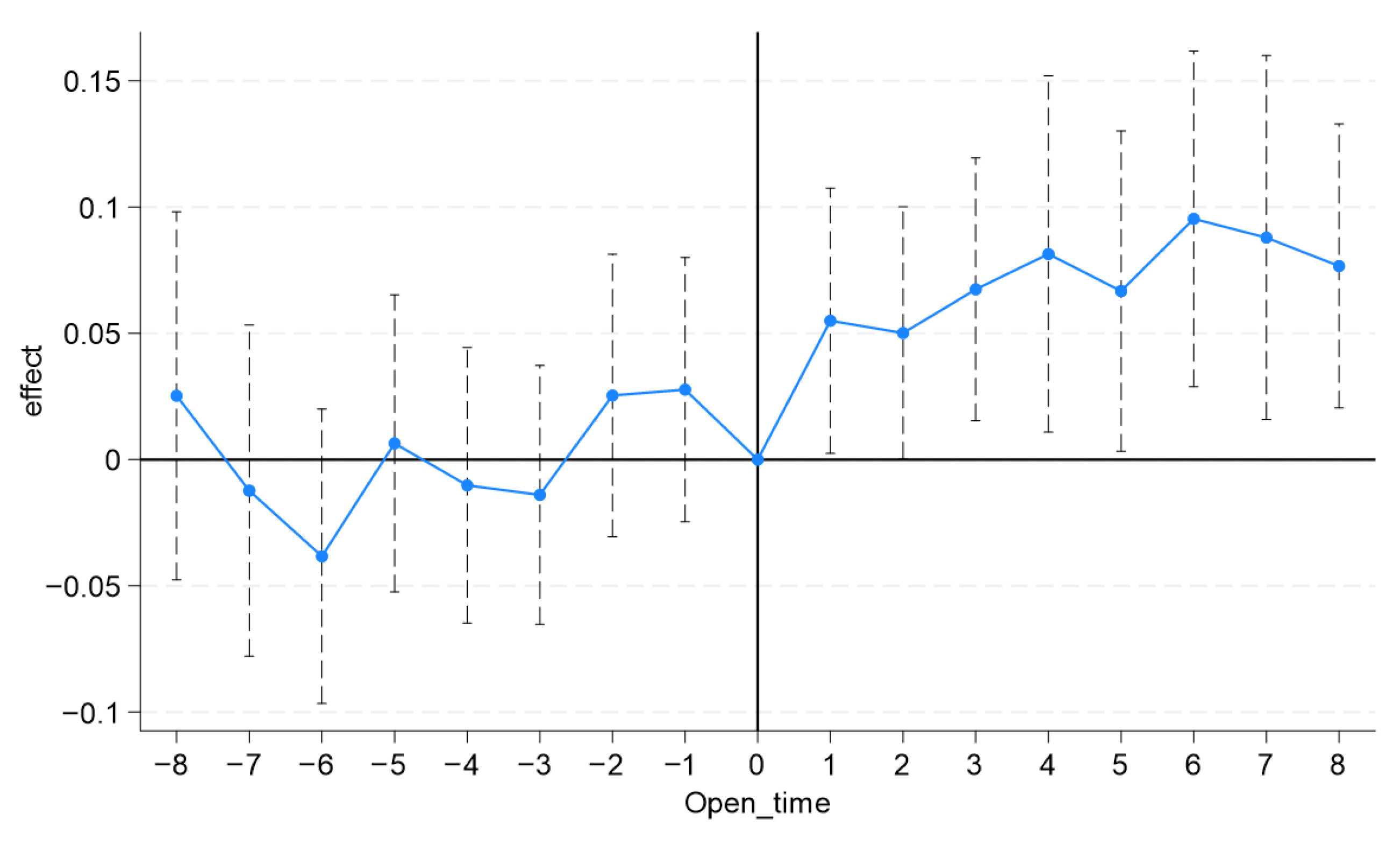

Figure 1 presents the results of the regression coefficient. It is obvious that the coefficient of HSR is not significant in the 8 years before the enterprise is connected to HSR, while the regression coefficient is larger and statistically significant after the opening of HSR. Thus, the parallel trend assumption holds.

Figure 1.

Parallel trend test. Note: The regression is performed with two-way fixed effects by containing main control variables. The y-axis is the regression coefficient of HSR, and the x-axis is the year before and after opening HSR. We use the high-speed rail opening date as the base period, constructing a relative time variable. −1 denotes the year prior to high-speed rail opening, 0 denotes the opening year, and 1 denotes the year following opening. The time window spans from 8 years prior to opening to 8 years thereafter, encompassing 17 observation periods. The pre-specified joint test yields a p-value of 0.116 (>0.1), satisfying the parallel trends assumption. Specific coefficient estimates indicate that the regression coefficients for the 8 periods preceding the policy (−8 to −1) are 0.0253, −0.0123, −0.0383, 0.0065, −0.0102, −0.0140, 0.0254, and 0.0277. The dashed line represents the confidence interval, reflecting whether an estimated coefficient is significant. If the interval includes zero, the coefficient is not significant; otherwise, it is significant.

4.3. Robustness Check

To assess the robustness of the findings presented in Table 2, we employ multiple robustness checks, with the detailed results reported in Table 3.

Table 3.

The results of robustness test.

Propensity Score Matching method (PSM): The selection of the location of a HSR is not a completely random event, and is usually affected by human factors, economic factors, and political factors [47,48]. Thus, the traditional DID model may cause biased results due to the self-selection issue [49]. The PSM method, matching the data first and then regressing the model using the DID approach, is usually adopted to solve this issue. The estimated regression results are shown in column (1). The coefficient of is 0.0621 and significant, indicating that HSR enhances the level of GI, thus verifying that the results are robust.

Change independent variables: We also add two control variables to verify the robustness of baseline results, namely, the operating debt ratio () and operating efficiency of assets (). The regressed results are listed in column (2), and the significantly positive coefficient of DID indicates that HSR enhances the level of GI.

Lag periods of dependent variable: There exists a lagged effect of HSR on the number of invention patents [50]; thus, we examine the long-term impact of HSR on GI by lagging the dependent variable by two periods. The corresponding results are listed in column (3). The coefficient is 0.0649 and statistically significant, supporting the suggestion that HSR can effectively contribute to GI improvement.

Replace GI variable.: To validate the robustness of results, we excluded the number of design patents from GI. The results are presented in column (4). The statistically significant and positive coefficient is 0.0411, implying that the conclusion that HSR enhances GI holds.

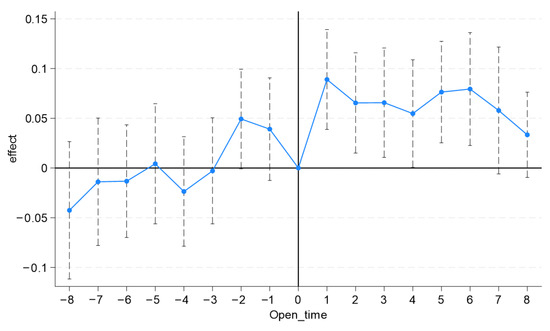

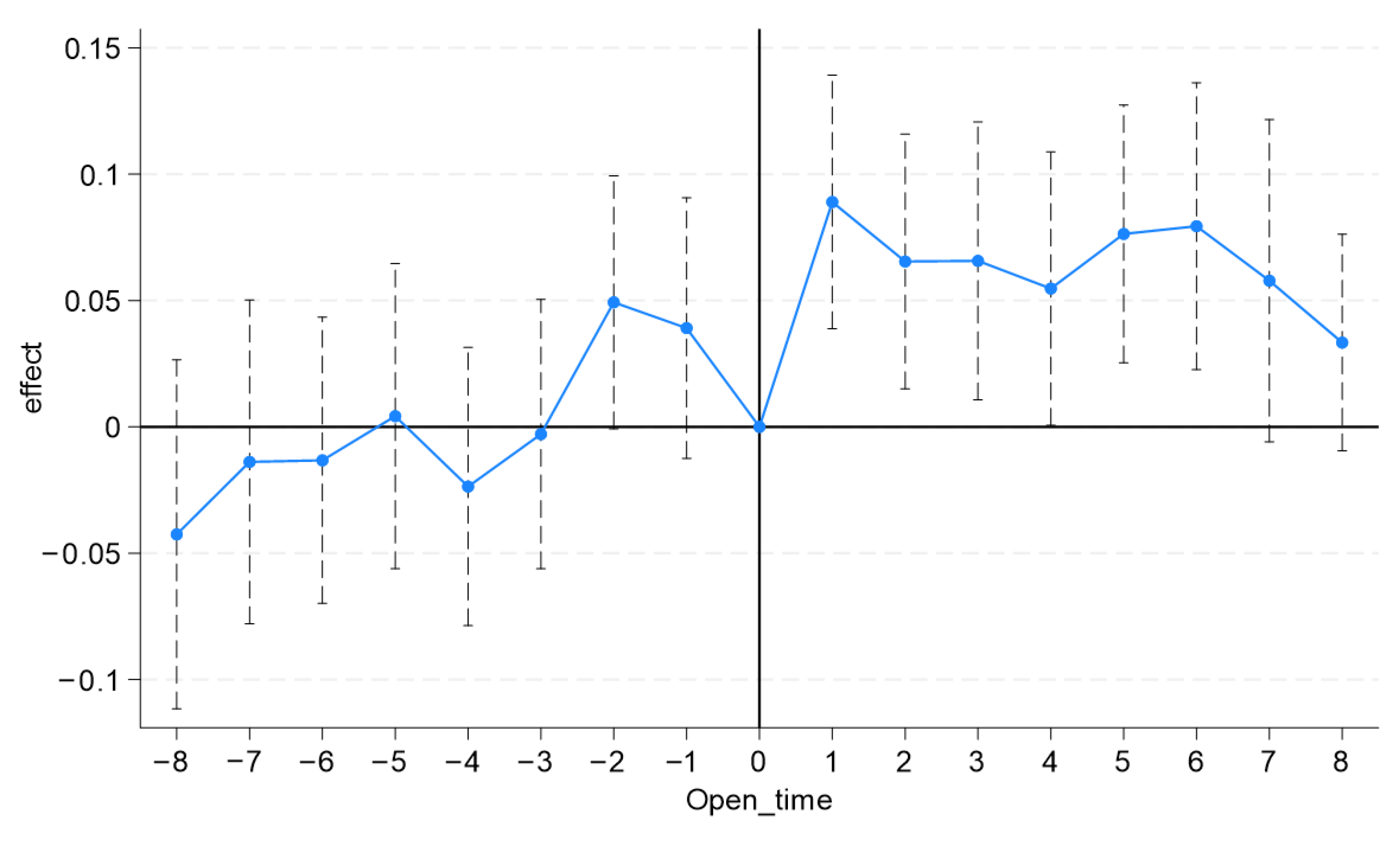

Change model specification: Two different models are used, and the first is the Poisson Pseudo-Maximum Likelihood with Fixed Effects (PPML-FE) specification, given that the dependent variable is discrete. The results are listed in column (5) of Table 3, and it can be seen that the coefficient of (0.1916) is significantly positive, larger than the baseline results of column (6) in Table 2. The second methodology considers the weight heterogeneity in multi-period DID methodology. Due to the standard DID with two-way fixed effects potentially producing estimation bias when policy shock exerts heterogeneous effects on different individuals, we perform dynamic effect testing referring to Sun and Abraham (2021) [51], and the corresponding results are shown in Appendix A. After applying the S-A statistic to estimate and address treatment effect heterogeneity, the dynamic effects are found to be consistent with the existing trends. Thus, the conclusion that HSR contributes to GI is not affected by the model specification.

Change the sample: We also excluded enterprises with multiple operating locations, and the results are shown in column (6). The coefficient of DID is 0.1916, which is significant at 1% level. Thus, the results of our baseline model are robust.

4.4. Test on the Mechanism

So far, the positive effect of HSR on GI has been verified. In this section, we will examine the mechanism of the impact of HSR on GI by two-step regression methodology, which is described as two steps.

In step 1, we first regress the DID with the mechanism variable, and further check whether the coefficient of DID is significant. If significant, we continue to the next steps; otherwise, we stop the analysis. In step 2, we then put the DID and the mechanism variable into the model where the dependent variable is GI. If the coefficient of the mechanism variable passes the significance test, it indicates that HSR affects GI through this mechanism.

As shown in Table 4, the core coefficients in column (1) and (2) are 0.0799 and 0.0765, respectively. Both of them are significantly positive, indicating that HSR improves GI by promoting the mobility of talent. Similarly, column (3) and (4) display the results of testing the role of financing constraints in the two-step regression. The significantly negative coefficients imply that HSR improves GI by alleviating the financing constraints of enterprises.

Table 4.

Two-step regression results.

Thus, the overall results verify Hypothesis 2.

4.5. Heterogeneity Analysis

4.5.1. Ownership Heterogeneity Analysis

To explore whether enterprise ownership has a heterogeneous effect on the promotion of GI by HSR, we divide the sample into two categories, namely, state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and non-state-owned enterprises (N-SOEs). The estimated results are listed in column (1) and (2) in Table 5. Both of the coefficients of are positive and pass the significance test at the level of 1%. In addition, the coefficient of in SOEs is larger than that in N-SOEs, which is consistent with [53].

Table 5.

Heterogenous results.

4.5.2. City Heterogeneity Analysis

In China, there is a large difference in economic development between regions; thus, we further explore the impact of HSR on GI in different cities. We use the annual per capita GDP as an indicator to measure the level of economic development and use the dynamic grouping adjustment method to divide cities into developed cities and undeveloped cities. Specifically, the per capita GDP data of each region are sorted and grouped every year; thus, cities with per capita GDP below the average are classified as undeveloped cities and cities with per capita GDP above the average are classified as developed cities. Columns (3) and (4) show the regression results. It can be seen that HSR improves GI in developed cities and undeveloped cities. In addition, the coefficient of in column (3) is greater than in column (4), which indicates that enterprises located in cities with a high level of economic development have seen a greater improvement in GI after the opening of HSR.

4.5.3. Pollution Intensity Heterogeneity Analysis

According to the secondary industry classification in the Guidelines for Industry Classification of Listed Companies, revised by the China Securities Regulatory Commission in 2012, we classify the manufacturing industries into heavily polluting industries and lightly polluting industries. The results are presented in column (5) and (6). Specially, the coefficient of in lightly polluting industries is positive and passes the significance threshold at the 1% level, while the corresponding coefficient in heavily polluting industries is insignificant. A possible reason for this is that highly polluting enterprises are often located in peripherical cities, and HSR may accelerate the flow of talent to tertiary industries in developed areas, exacerbating the loss of innovative resources for these enterprises.

5. Conclusions and Policy Implications

5.1. Conclusions

A substantial number of studies on the economic and environmental consequences of HSR have neglected the impact of HSR on GI, especially from the micro-perspective. Thus, we used a multi-period DID method to explore the effect of HSR on GI by using the data of manufacturing companies from 2004 to 2023.

The main empirical conclusions are as follows. Firstly, HSR significantly improves the level of GI in enterprises, and the results are still stable after several robust checks. Secondly, significant heterogenous effects exist in different enterprises and cities. Specially, HSR has a greater impact on the improvement of GI in lightly polluting SOEs of developed cities. Finally, the mechanism for HSR to improve GI is to promote the mobility of talent and alleviate financing constraints on enterprises.

5.2. Policy Implications

Our conclusions show positive evidence for the relationship between HSR and enterprise’s GI, which offers significant policy implications for constructing HSR and enhancing GI.

Firstly, the government should further expand the network of HSR to fully leverage its network effects, such as the mobility of capital, labors, and technology. It is widely recognized that undeveloped cities lag behind developed cities in terms of resource endowment, and the opening of HSRs have greater spillover effects on developed cities based on our empirical results. Therefore, the government should attract innovative factors to flow in these undeveloped cities to enlarge HSR’s positive effect on GI by conducting related policies.

Secondly, HSR has greater impact on the improvement of GI in lightly polluting industries, especially for tertiary industries, and thus, cross-industry innovation collaboration based on HSR network is suggested to improve the level of GI in highly polluting industries. Furthermore, HSR enhances the GI level of enterprises regardless of ownership, demonstrating that HSR provides equitable development opportunities for different enterprises.

Finally, HSR reduces financing costs and information asymmetry for GI in the financing process and further improves the level of GI of enterprises. Based on this, local government and enterprise should endeavor to enhance the environment of capital to alleviate the financing constraints.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.Y.; Software, X.Y.; Validation, L.Z.; Resources, H.L.; Data curation, X.Y.; Writing—original draft, K.Y.; Writing—review & editing, K.Y.; Visualization, X.Y.; Supervision, H.L.; Funding acquisition, L.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Social Science Foundation of China, grant number 22BJY258, Ludong University start-up funds, grant number 221/20230018.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Dynamic effects, excluding treatment effects.

Figure A1.

Dynamic effects, excluding treatment effects.

Table A1.

Heterogeneity results based on S-A statistic.

Table A1.

Heterogeneity results based on S-A statistic.

| ATT (Average Treatment Effect on the Treated) | p-Value |

|---|---|

| 0.058 | 0.001 |

References

- de Azevedo Rezende, L.; Bansi, A.C.; Alves, M.F.R.; Galina, S.V.R. Take Your Time: Examining When Green Innovation Affects Financial Performance in Multinationals. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 233, 993–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunday, G.; Ulusoy, G.; Kilic, K.; Alpkan, L. Effects of Innovation Types on Firm Performance. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2011, 133, 662–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, D.R.; Dingel, J.I. A Spatial Knowledge Economy. Am. Econ. Rev. 2019, 109, 153–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Attoma, I.; Ieva, M. Determinants of Technological Innovation Success and Failure: Does Marketing Innovation Matter? Ind. Mark. Manag. 2020, 91, 64–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khurshid, A.; Huang, Y.; Cifuentes-Faura, J.; Khan, K. Beyond Borders: Assessing the Transboundary Effects of Environmental Regulation on Technological Development in Europe. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 200, 123212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, X.; Li, Q.; Du, K. How Does Environmental Regulation Promote Technological Innovations in the Industrial Sector? Evidence from Chinese Provincial Panel Data. Energy Policy 2020, 139, 111310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnet, P.; Olper, A. Foreign Import Competition and Green Innovation: The Impact of Chinese Trade Exposure on Technical Change in Europe. World Econ. 2025, 48, 1418–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorodnichenko, Y.; Svejnar, J.; Terrell, K. Do Foreign Investment and Trade Spur Innovation? Eur. Econ. Rev. 2020, 121, 103343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Un, C.A.; Rodríguez, A. Local and Global Knowledge Complementarity: R&D Collaborations and Innovation of Foreign and Domestic Firms. J. Int. Manag. 2018, 24, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.-L.; Cheah, J.-H.; Azali, M.; Ho, J.A.; Yip, N. Does Firm Size Matter? Evidence on the Impact of the Green Innovation Strategy on Corporate Financial Performance in the Automotive Sector. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 229, 974–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.H.; Zhao, Z.; Semadeni, M. How and Why Top Executives Influence Innovation: A Review of Mechanisms and a Research Agenda. J. Manag. 2025, 51, 2320–2354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Zheng, J. The Impact of High-Speed Rail on Innovation: An Empirical Test of the Companion Innovation Hypothesis of Transportation Improvement with China’s Manufacturing Firms. World Dev. 2020, 127, 104838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Li, H.; Ghosal, V. Firm-Level Human Capital and Innovation: Evidence from China. China Econ. Rev. 2020, 59, 101388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunley, P. Relational Economic Geography: A Partial Understanding or a New Paradigm? Econ. Geogr. 2008, 84, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H. How Does Agglomeration Promote the Product Innovation of Chinese Firms? China Econ. Rev. 2015, 35, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Guan, M.; Dou, J. Understanding the Impact of High Speed Railway on Urban Innovation Performance from the Perspective of Agglomeration Externalities and Network Externalities. Technol. Soc. 2021, 67, 101760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Lai, S.; Ni, Y.; Chen, L. Dynamic Modelling and Analysis of a Physics-Driven Strategy for Vibration Control of Railway Vehicles. Veh. Syst. Dyn. 2024, 63, 1080–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Li, D.; Zeng, J.; Peng, X.; Wei, L.; Du, W. A Diagnostic Method of Freight Wagons Hunting Performance Based on Wayside Hunting Detection System. Measurement 2024, 227, 114274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, J. Location, Economic Potential and Daily Accessibility: An Analysis of the Accessibility Impact of the High-Speed Line Madrid–Barcelona–French Border. J. Transp. Geogr. 2001, 9, 229–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez Sánchez-Mateos, H.S.; Givoni, M. The Accessibility Impact of a New High-Speed Rail Line in the UK—A Preliminary Analysis of Winners and Losers. J. Transp. Geogr. 2012, 25, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, A.; Duflo, E.; Qian, N. On the Road: Access to Transportation Infrastructure and Economic Growth in China. J. Dev. Econ. 2020, 145, 102442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, H.; Lin, S.; Zhang, J.; Zeng, J. Does High-Speed Railway Promote Regional Innovation Growth or Innovation Convergence? Technol. Soc. 2021, 64, 101472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, L.; Sun, W.; Zheng, S. Transportation Network and Venture Capital Mobility: An Analysis of Air Travel and High-Speed Rail in China. J. Transp. Geogr. 2020, 88, 102852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Q.; Liao, M.; Wang, Y. Transportation Infrastructure, Market Integration and Corporate Innovation. Appl. Econ. 2025, 57, 5427–5443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, N.; Sun, W.; Zhang, L. The Innovation Effects of Transportation Infrastructure: Evidence from Highways in China. Econ. Transp. 2024, 38, 100352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, W.; Tang, J. Does the Construction of Transportation Infrastructure Enhance Regional Innovation Capabilities: Evidence from China. J. Knowl. Econ. 2023, 14, 3598–3615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Xie, Y.; Zhuo, C. How Does International Transport Corridor Affect Regional Green Development: Evidence From The China-Europe Railway Express. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2024, 67, 1602–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, J.; Shi, J.; Li, J.; Liu, J.; Sriboonchitta, S. Does China-Europe Railway Express Improve Green Total Factor Productivity in China? Sustainability 2023, 15, 8031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Wang, Y. How Does High-Speed Railway Affect Green Innovation Efficiency? A Perspective of Innovation Factor Mobility. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 265, 121623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Fan, Q.; Tao, C. The Impact of High-Speed Rail on Regional Green Innovation Performance-Based on the Dual Perspective of High-Speed Rail Opening and High-Speed Rail Network. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2023, 32, 1459–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Lin, X.; Yang, H. Booming with Speed: High-Speed Rail and Regional Green Innovation. J. Adv. Transp. 2021, 2021, 9705982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Wang, F.; Yao, S. Does Government-Driven Infrastructure Boost Green Innovation? Evidence of New Infrastructure Plan in China. J. Asian Econ. 2024, 95, 101828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Liu, Y.; Sheng, L.; Yu, Z. The Impacts of High-Speed Rail Networks on Urban Green Innovation. Transp. Policy 2025, 163, 168–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y. ‘No County Left Behind?’ The Distributional Impact of High-Speed Rail Upgrades in China. J. Econ. Geogr. 2017, 17, 489–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlfeldt, G.M.; Feddersen, A. From Periphery to Core: Measuring Agglomeration Effects Using High-Speed Rail. J. Econ. Geogr. 2018, 18, 355–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Guo, H. Spatial Spillovers of Pollution via High-Speed Rail Network in China. Transp. Policy 2021, 111, 138–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diebolt, C.; Hippe, R. The Long-Run Impact of Human Capital on Innovation and Economic Development in the Regions of Europe. Appl. Econ. 2019, 51, 542–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charnoz, P.; Lelarge, C.; Trevien, C. Communication Costs and the Internal Organisation of Multi-Plant Businesses: Evidence From the Impact of the French High-Speed Rail. Econ. J. 2018, 128, 949–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Li, W. High-Speed Railway Network, City Heterogeneity, and City Innovation. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Tu, M.; Chagas, A.; Tai, L. The Impact of High-Speed Railway on Labor Spatial Misallocation—Based on Spatial Difference-in-Differences Analysis. Transp. Res. Part A 2022, 164, 82–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Tan, K.; He, J. The Impact of Opening a High-Speed Railway on Urban Innovation: A Comparative Perspective of Traditional Innovation and Green Innovation. Land 2023, 12, 1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A.; Galasso, A.; Oettl, A. Roads and Innovation. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2017, 99, 417–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Zheng, S.; Kahn, M.E. The Role of Transportation Speed in Facilitating High Skilled Teamwork across Cities. J. Urban Econ. 2020, 115, 103212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.R.; Fazzari, S.M.; Petersen, B.C. Financing Innovation and Growth: Cash Flow, External Equity, and the 1990s R&D Boom. J. Financ. 2009, 64, 151–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, H.; Li, Y. High-Speed Railway, Factor Flow and Enterprise Innovation Efficiency: An Empirical Analysis on Micro Data. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2022, 82, 101305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, L.S.; LaLonde, R.J.; Sullivan, D.G. Earnings Losses of Displaced Workers. Am. Econ. Rev. 1993, 83, 685–709. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, S.; Tian, Z.; Yang, L. High Speed Rail and Urban Service Industry Agglomeration: Evidence from China’s Yangtze River Delta Region. J. Transp. Geogr. 2017, 64, 174–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X. High-Speed Railway and Urban Sectoral Employment in China. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2018, 116, 603–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Xu, Y. Does High-Speed Railway Promote Urban Innovation? Evidence from China. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2023, 86, 101464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, R.; Li, C.; Qiu, Y.; Huang, J.; Lin, X. Can High-Speed Rail Promote Regional Technological Innovation? An Explanation Based on City Network Centrality. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2024, 57, 101245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Abraham, S. Estimating Dynamic Treatment Effects in Event Studies with Heterogeneous Treatment Effects. J. Econom. 2021, 225, 175–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S.N.; Zingales, L. Do Investment-Cash Flow Sensitivities Provide Useful Measures of Financing Constraints? Q. J. Econ. 1997, 112, 169–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Wang, E. The Impact of Transportation Infrastructure on Manufacturing Energy Intensity: Micro Evidence from High-Speed Railway in China. Energy J. 2024, 45, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).