Abstract

As tourism increasingly drives the revitalization of traditional villages, rural spaces are undergoing a transformation from functional living areas to spaces for cultural display and leisure. This shift has amplified the spatial usage discrepancies between multiple stakeholders, such as tourists and villagers, highlighting conflicts in spatial resource allocation and behavior path organization. Using Wulin Village, a typical example of a Minnan overseas Chinese village, as a case study, this paper introduces social network analysis to construct a “spatial–behavioral” dual network model. The model integrates both architectural and public spaces, alongside behavior path data from villagers and tourists, to analyze the spatial structure at three scales: village-level network completeness, district-level structural balance, and point-level node vulnerability. The study integrates two dimensions—architectural space and public space—along with behavioral path data from both villagers and tourists. It reveals the characteristics of spatial structure under the intervention of multiple behavioral agents from three scales: village-level network completeness, district-level structural balance, and point-level node vulnerability. The core research focus of the spatial network includes the network structure of architectural and public spaces, while the behavioral network concerns the activity paths and behavior patterns of tourists and villagers. The study finds that, at the village scale, Wulin Village’s spatial network demonstrates good connectivity and structural integrity, but the behavior paths of both tourists and villagers are highly concentrated in core areas, leading to underutilization of peripheral spaces. This creates an asymmetry characterized by “structural integrity—concentrated behavioral usage.” At the district scale, the spatial node distribution appears balanced, but tourist behavior paths are concentrated around cultural nodes, such as the ancestral hall, visitor center, and theater, while other areas remain inactive. At the point scale, both tourist and villager activities are highly dependent on a few high-degree, high-cluster nodes, improving local efficiency but exacerbating systemic vulnerability. Comparison with domestic and international studies on cultural settlements shows that tourism often leads to over-concentration of spatial paths and node overload, revealing significant discrepancies between spatial integration and behavioral usage. In response, this study proposes multi-scale spatial optimization strategies: enhancing accessibility and path redundancy in non-core areas at the village scale; guiding behavior distribution towards multifunctional nodes at the district scale; and strengthening the capacity and resilience of core nodes at the point scale. The results not only extend the application of behavioral network methods in spatial structure research but also provide theoretical insights and practical strategies for spatial governance and cultural continuity in tourism-driven cultural villages.

1. Introduction

As global tourism consumption demands become increasingly diverse and space-oriented experiences continue to gain importance, rural tourism is emerging as a key path for promoting regional economic vitality, cultural heritage preservation, and urban–rural integration. An increasing number of countries and regions are incorporating historical cultural settlements into tourism development frameworks, leveraging tourism resources to drive rural revitalization and cultural dissemination. In particular, spatial restructuring has been used to enhance tourism reception capacity and improve cultural communication efficiency. As a result, traditional villages with distinctive cultural features have become a critical focus of research in tourism space governance [1,2,3]. Compared to urbanized tourist destinations, tourism-based traditional villages typically face challenges such as loosely organized spaces, heterogeneous functional nodes, and dispersed cultural information. In the process of rapid tourism development, tourists’ movement patterns, duration of stay, and cultural perceptions often misalign with the existing spatial structure, resulting in issues such as unclear spatial identification, fragmented experiences, and inefficient behavior organization [4]. This systemic mismatch between spatial structure and tourist behavior has become a fundamental barrier to the high-quality development of tourism-based traditional villages [5]. Therefore, conducting systematic research on the spatial and behavioral adaptability optimization of traditional rural tourism villages is of significant theoretical and practical importance for resolving the contradictions between spatial resource allocation and behavior path organization, as well as for enhancing spatial vitality.

In response to the conflicts between spatial structure and behavior organization in tourism-based traditional villages, existing research has proposed various methods, such as space syntax analysis, accessibility modeling, and tourist trajectory mining. Some scholars have attempted to optimize tourism routes and node layouts through GIS analysis [6], network centrality evaluation, and point-of-interest (POI) distribution analysis [7]. Other studies have focused on the coupling relationship between cultural sites and behavior hotspots, exploring the balance between spatial governance and cultural preservation [8]. However, existing research often focuses on a singular dimension, such as structural optimization or behavioral visualization. This one-dimensional approach tends to overlook the complex interaction between spatial structure and tourist behavior, resulting in an incomplete reflection of their dynamic relationship. Therefore, the introduction of a dual-network model enables the simultaneous consideration of multi-dimensional factors related to spatial structure and tourist behavior. Through the analysis of the coupling mechanism, it better reveals the mutual influence and coordination between the two, providing more comprehensive theoretical support for optimizing tourism path design and spatial governance. Located in southeastern coastal China, Wulin Village in Jinjiang, Fujian Province, is a nationally recognized historical and cultural village. The spatial layout of Wulin Village presents a complex feature of both Eastern and Western architectural styles, retaining the closed layout of traditional clan settlements while integrating Nanyang overseas Chinese architecture and Western spatial elements, resulting in a highly rich cultural layer [9]. However, this spatial complexity also introduces significant adaptive pressures. In recent years, with the increase in tourism numbers and the intensification of development, the behavior paths within Wulin Village have become increasingly nonlinear, with severe imbalances in the frequency of spatial node usage. Cultural experiences have shifted from continuity to fragmentation, and the structural coordination and behavioral carrying capacity of cultural spaces are facing severe challenges. To address these challenges, this study introduces social network analysis and selects Wulin Village as a case study for typical rural tourism villages. The research constructs a structural–behavioral collaborative analysis framework based on tourist behavior paths, public space networks, and architectural networks. By identifying key nodes and weak links in the network, the study proposes spatial optimization strategies oriented toward the logic of tourist use, aiming to achieve multiple goals: rationalizing spatial configuration, efficiently guiding behavior paths, and enhancing the continuity of cultural experiences. This research provides new technical pathways for tourism space governance in traditional villages from both methodological and practical perspectives. On the one hand, it expands the application of behavioral network methods in spatial research; on the other hand, it provides a transferable theoretical reference and strategy for the spatial reconstruction and cultural transmission of cultural villages in tourism contexts.

2. Literature Review

Behavioral network theory, derived from Social Network Analysis (SNA) and Actor-Network Theory (ANT), has been widely expanded in the field of rural studies in recent years, gradually forming an interdisciplinary research trend that intersects governance, tourism, and social capital [10,11]. The application of behavioral network theory in rural studies has primarily focused on three areas. 1. Network-enabled rural governance: This research focuses on information dissemination pathways [12], digital transformation of governance structures [13], and multi-stakeholder interaction mechanisms [14]. For instance, some studies have explored how digital platforms in ethnic regions are moderated by cultural differences, leading to differentiated network structures [15]. 2. Tourist behavior networks and spatial optimization: This area of research emphasizes the modeling of tourist path networks [16], the relationship structure between tourists and residents [17], and behavior-driven spatial optimization strategies [18]. For example, research on the Baila Yuan Cultural Village used trajectory data to construct tourist behavior networks and proposed suggestions for optimizing the layout of public nodes [19]. Other studies have integrated stakeholder network analysis to examine changes in resident participation in tourism development and its feedback on spatial structures [20]. 3. Social capital and collective action networks: This strand of research focuses on social structures and collaborative capacity [21], the roles of returning migrants in network formation [22], and farmer mutual aid networks. For example, a study on ancient villages in southern Jiangsu revealed the embedded patterns of clan relationships in collective action [23]. Other scholars have compared the evolution of networks in poverty alleviation enterprises before and after the pandemic, demonstrating the impact of external shocks on behavioral network structures [24].

Recent studies on tourism village spaces have primarily focused on three main areas. 1. The identification and classification of tourism village spatial forms, with an emphasis on recognizing and categorizing the spatial morphology of tourism villages: This research typically starts with geographic patterns, functional layouts, and development stages, performing both qualitative and quantitative identification of spatial forms in tourism villages [25]. Some scholars have classified tourism villages into typical types, such as point-based agglomeration, emphasizing differences in spatial organizational patterns influenced by natural conditions and policy initiatives [26]. For example, studies have used spatial clustering methods to identify the evolutionary paths of several typical tourism villages and highlighted the influencing factors [27]. 2. The optimization of the spatial functional layout and service configuration in tourism villages: This research often focuses on land use efficiency, infrastructure provision, and tourism reception capacity, emphasizing the rationality of functional zoning and spatial utilization [28,29]. For example, some studies have combined GIS and multi-factor evaluation models to assess the suitability of tourism function areas in traditional villages and provide recommendations for adjustment [30]. 3. The multi-dimensional evaluation system and technical methods for the optimization of tourism village spaces: With the advancement of digital technologies, an increasing number of studies have incorporated GIS, remote sensing, and space syntax modeling to conduct spatial optimization assessments, from macro-level planning to micro-level nodes [31]. Additionally, multi-dimensional indicators have been integrated into the optimization evaluation system, reflecting a shift from “physical space regulation” to “human–environment relationship coordination” [32].

Moreover, the spatial form of localized villages is deeply shaped by long-standing clan structures, ritual cultures, and natural landscapes, exhibiting significant non-standard characteristics and cultural embeddedness [33]. Traditional planning methods often fail to accommodate the complex path systems and cultural nodes of such villages [34]. For example, the circular alleys of the Fujian Yongding Tulou and the traditional street lanes of Wuzhen in Zhejiang face the conflict between “optimal tourist flow” and “continuous residential life” in tourism development [35,36]. In summary, although current research on tourism village space optimization has made continuous progress in spatial form identification, functional layout, and evaluation methods, the collaborative analysis of spatial networks and tourist behavior networks remains relatively underdeveloped. Existing behavioral network studies mainly focus on individual tourist path modeling, with limited integration with physical spatial structures. Given the complex and ambiguous spatial patterns of traditional villages, there is an urgent need to construct network optimization paths that combine behavioral characteristics with spatial structures to improve space utilization efficiency and tourism experience. Therefore, this study aims to explore the coupling relationship between spatial networks and tourist behavior networks in tourism villages, revealing the interaction between tourist behavior characteristics and spatial structures, and analyzing the impact of behavior networks on spatial node functions, path organization, and flow efficiency. Through these analyses, the study seeks to provide theoretical support and practical pathways for the structural optimization and behavioral response of tourism space in traditional villages, promoting the optimization of tourism village spatial layouts, the activation of non-core areas, and the sustainable development of spaces.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Area

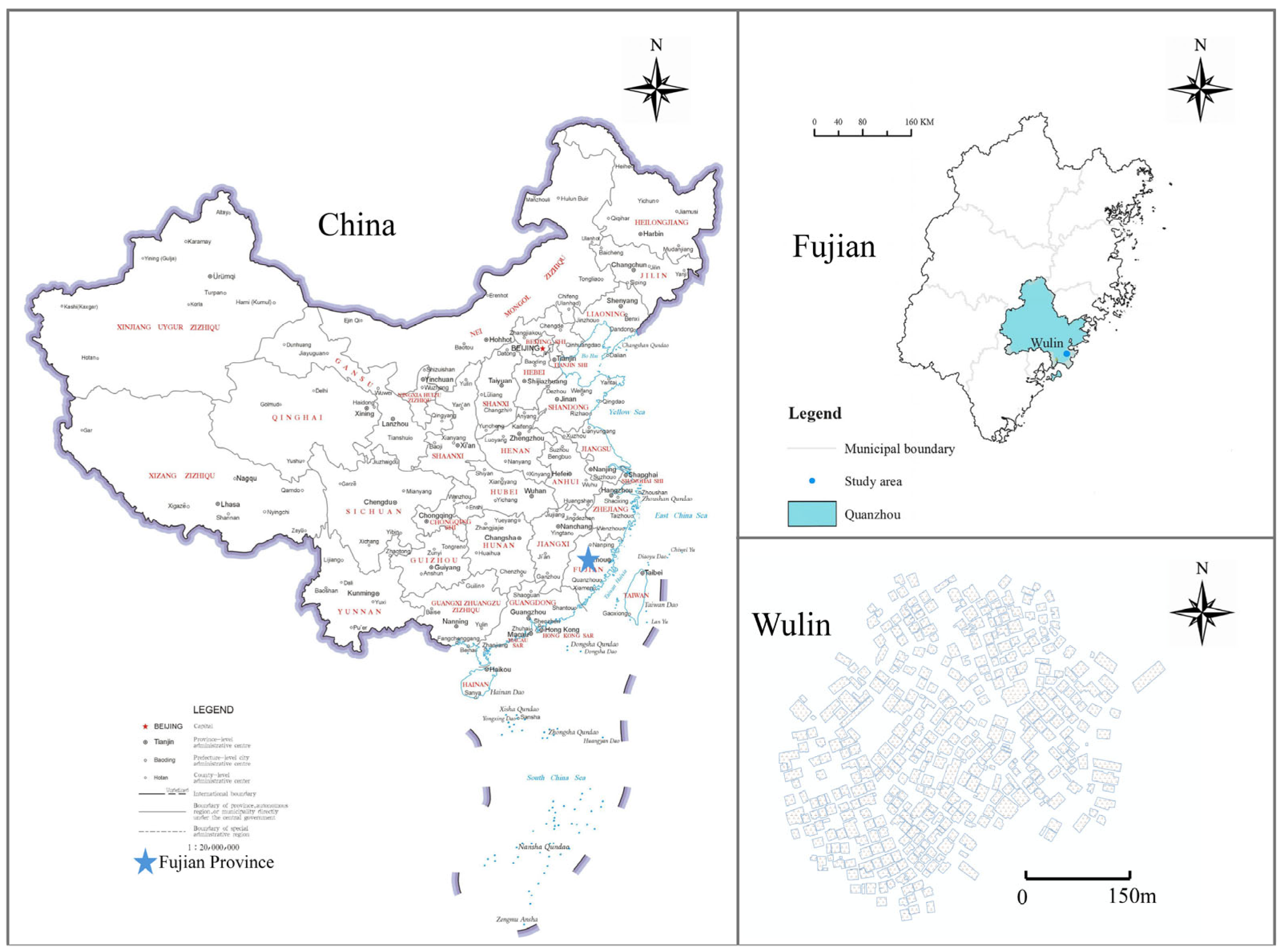

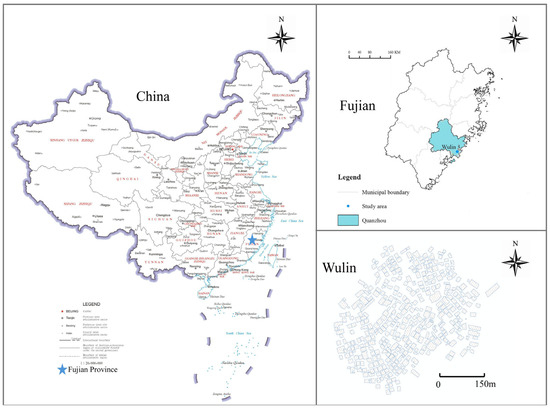

This study selects Wulin Village as a typical case to explore spatial optimization strategies for rural tourism from the perspective of behavioral networks. Wulin Village is located in the southwestern part of Xintang Street, Jinjiang City, Fujian Province, adjacent to the national key project Jinhua Integrated Circuit Industrial Park and the central axis of the Jinjiang–Shishi twin cities, offering convenient transportation with extensive connectivity (see Figure 1). The village is only 2 km from the Jinjiang South High-Speed Rail Station and 6 km from Quanzhou Jinjiang Airport, with a clear advantage of a 10 min living circle. This strategic location provides a solid foundation for absorbing urban spillover and attracting short-term tourists. Currently, Wulin Village faces dual pressures from urban spatial reconstruction and an increase in tourist numbers. Wulin Village covers an area of approximately 1 square kilometer, with a resident population of 2050 and over 12,000 overseas Chinese, making it a typical Minnan overseas Chinese village. The village is situated in a hilly, gentle slope area, with its development adapted to the natural terrain. It benefits from abundant ecological resources, a rich water system, and favorable climate conditions. The natural rural landscape formed along the Wudianxi Stream provides ideal conditions for developing eco-tourism, agricultural experiences, and waterfront leisure spaces.

Figure 1.

Study Area Location Map.

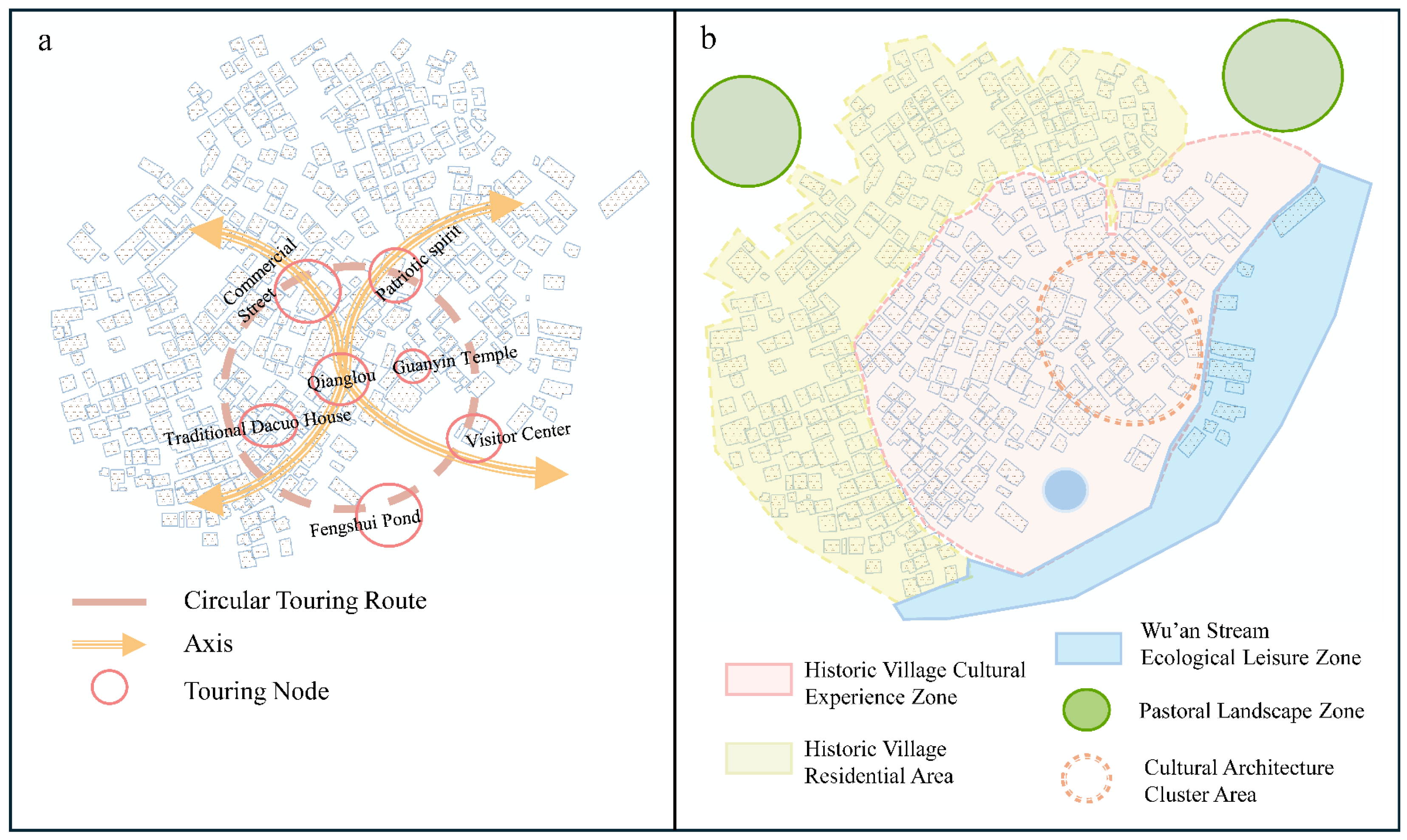

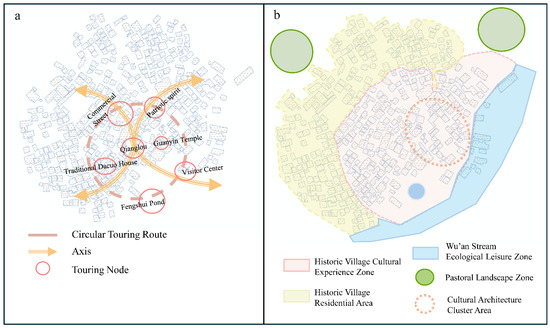

In addition, as a cultural village, Wulin Village’s heritage resources and spatial structure are deeply intertwined. The village is home to 99 well-preserved overseas Chinese residential buildings dating from the late Qing Dynasty to the early Republic of China period, featuring a mix of architectural styles including Minnan-style “Dazhu,” Gothic, and Romanesque, forming a highly aesthetic and historically valuable overseas Chinese architectural complex. Among these buildings are many religious and cultural structures, such as the ancestral hall, Gongma Hall, Qianggong Building, and Guanyin Temple. At the same time, the intangible cultural heritage represented by “Nanyin” (Southern Music) has been actively passed down for generations, serving as a cultural link and injecting a unique artistic atmosphere and behavioral domain into the village space. With the dual push of tourism development and the revival of overseas Chinese culture in recent years, Wulin Village has gradually become an important destination for educational travel, cultural heritage exploration, and short leisure trips by urban residents. Wulin Village adheres to a sustainable development philosophy and actively preserves its traditional village layout, planning its structure as “one ring, one cross, multiple nodes” (see Figure 2a). Currently, Wulin Village is divided into four functional zones: the Ancient Village Cultural Experience Zone, Ancient Village Residential Area, Wudianxi Ecological Leisure Zone, and Pastoral Style Zone, with a large concentration of culturally significant traditional buildings in the Ancient Village Cultural Experience Zone (see Figure 2b). However, the pressure of urban spatial reconstruction is increasing, especially during the process of urban–rural integration and spatial structure optimization. Wulin Village faces dual challenges from both urbanization and increasing tourist traffic. The current layout of tourism spaces still exhibits issues such as fragmented functional zones, a lack of guidance for behavioral paths, and insufficient interaction between core attractions and supporting spaces. Moreover, the blend of Chinese and Western architectural styles in Wulin Village may, to some extent, exacerbate the behavioral network differences between tourists and villagers, which could significantly affect the results of the dual-network model. Therefore, this study uses Wulin Village as a case study, focusing on the spatial relationship networks of multiple stakeholders, including tourists, villagers, and overseas Chinese, to explore feasible pathways for integrating rural spatial functions, optimizing cultural pathways, and enhancing the tourism experience. This case study is representative and typical of addressing these challenges.

Figure 2.

Overview of the Study Area. (a) Wulin Village Planning Structure, (b) Wulin Village Functional Zoning.

3.2. Methods

3.2.1. Construction of Spatial and Behavioral Networks

This study utilizes complex network analysis to construct the public space and architectural networks of Wulin Village. Complex network analysis, primarily based on Social Network Analysis (SNA), aims to study the relationships between individuals within a complex network. The fundamental principle is to treat each individual as a “node” and the connections between individuals as “edges,” thereby constructing a network model to quantitatively analyze the relationships within the network [37,38,39]:

First, the identification of nodes and connections in Wulin Village is conducted. In this study, the “nodes” and “edges” of the spatial and behavioral networks are defined as shown in Table 1. If there is a geographical connection between a building/space and another element (i.e., if a road geographically touches or is in proximity to a building or public space), it is considered an “edge,” marked as 1; otherwise, it is marked as 0. The road system is treated as “edges,” with a connection between nodes recorded as 1, and no connection as 0.

Table 1.

The Definition of “Node-Edge” in the Spatial and Behavioral Networks of Wulin Village.

Second, basic data for each node is collected. A two-dimensional map captured by drones is imported into ArcMap 10.6, where the spatial boundaries of roads and built-up areas are quantified. Using the software’s spatial connectivity tools, the relationships between nodes and edges are obtained. The data is then converted into a relationship matrix using Matlab2019 software.

Third, through a questionnaire survey, the movement trajectories of tourists and villagers are collected. The public spaces and buildings visited by both villagers and tourists are marked on a two-dimensional map. The marked buildings and public spaces are treated as “points,” while the movement paths are treated as “lines.” If there is a geographical connection between the marked buildings/public spaces (i.e., if a road geographically touches or is in close proximity to a building or public space), it is considered a “line” relationship, recorded as 1; otherwise, it is recorded as 0. Behavioral paths are treated as “lines,” with a connection between nodes recorded as “1,” and no connection as “0.”

Fourth, the architectural and public space network model, as well as the behavioral network model, are constructed for this study (see Table 1). After organizing the data as described above, it is input into Ucinet 6.0 to build the overall spatial network and behavioral network. Subsequently, visual representations of these two types of networks are generated, and relevant metrics are calculated.

3.2.2. Selection of Indicators for Spatial and Behavioral Network Models

The characteristics of Wulin Village’s spatial network, villagers’ behavioral network, and tourists’ behavioral network are analyzed from three perspectives: network completeness (K-core, network density), balance (degree centrality, betweenness centrality), and vulnerability (articulation points, network efficiency). The specific definitions of the indicators are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Network Feature Indicators.

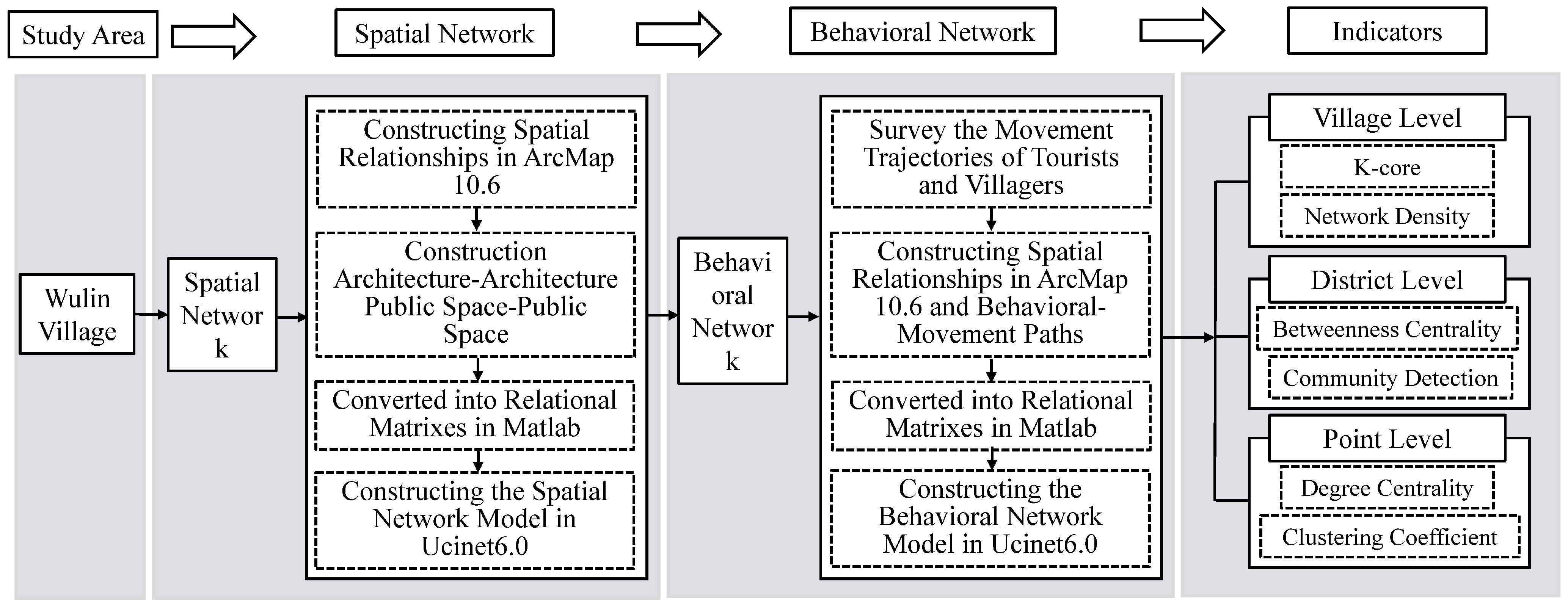

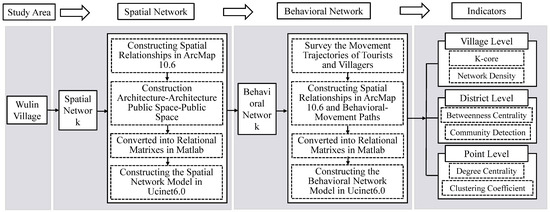

3.3. Data Processing

The data processing process (Figure 3) is as follows: 1. The two-dimensional map of the current state of Wulin Village, captured by a drone, is imported into ArcMap 10.6, where the edges of the objective spatial elements (roads, buildings, public spaces) are quantified. Additionally, based on the survey data, the edges of the villagers’ and tourists’ behavior network elements (such as buildings/public spaces where villagers and tourists stay or gather, and behavioral paths) are also quantified. 2. The spatial connectivity function in ArcMap is used to obtain the “node-edge” relationships for the objective spatial and behavioral networks. 3. The data obtained from ArcMap is imported into Matlab 2019, where the relationships between the objective spatial network elements and behavioral network elements are converted into a matrix. 4. The obtained matrix is imported into Ucinet 6.0 to construct the network topology diagrams for both the objective spatial and behavioral networks. The software’s calculation functions are then used to compute the selected indicators. 5. Compare the data of various indicators for different types of networks and conduct a comparative analysis of the spatial network and behavioral network characteristics of Wulin Village.

Figure 3.

Data processing.

4. Results and Analysis

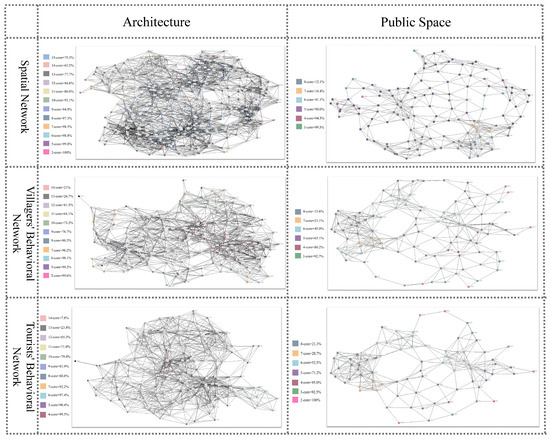

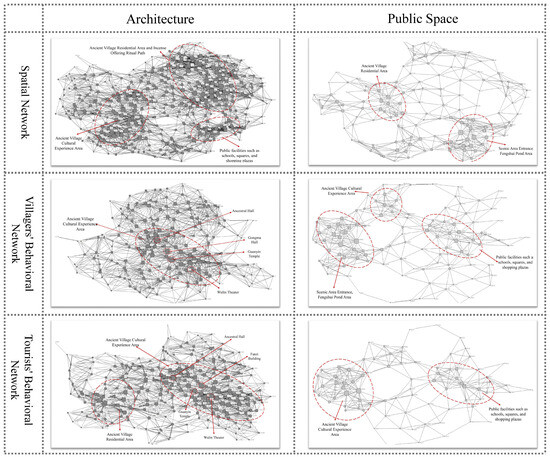

4.1. Spatial and Behavioral Topological Network Analysis of Wulin Village

Table 3 shows that Wulin Village’s architectural and public space networks contain no isolated nodes, indicating a well-organized road system and good connectivity between spatial units. The architectural space network, with 403 nodes, reflects the village’s diverse buildings and complex spatial structure, which support both daily life and tourism. However, the large number of nodes does not necessarily imply tight connectivity, which needs to be confirmed through behavior path analysis. The villagers’ network has 109 nodes, showing a decentralized structure that covers various daily activities like residential, religious, and social spaces. In contrast, the tourists’ network has 80 nodes, concentrated around cultural nodes such as the ancestral hall, Guanyin Temple, and the visitor center. The tourist paths are highly concentrated, goal-oriented, and constrained by tourism guidance and site layout. In the public space network, both villagers’ and tourists’ paths intersect at key nodes, which are central to shared spaces. These nodes have high connectivity, serving as daily-use areas for villagers and gathering points for tourists, making them the most active spaces in terms of interaction. A comparison of the architectural and public space networks reveals that the villagers’ behavior network emphasizes breadth and flexibility, while the tourists’ behavior network focuses on intensity and path concentration, creating a contrast between “distributed—concentrated” spatial use.

Table 3.

Wulin Village Spatial and Behavioral Network Topology and Node Count.

Overall, Wulin Village’s spatial network shows clear hierarchical and behavior-driven features. Villagers’ network is decentralized around daily needs, while tourists’ network is concentrated around cultural displays. The overlap of these networks at shared nodes is key to spatial integration and tourism management. To optimize these spaces, accessibility and functional configuration should be improved to increase efficiency, reduce node pressure, and promote interaction between tourists and villagers, supporting spatial coordination and sustainable development in rural tourism.

4.2. Spatial and Behavioral Network Completeness Analysis of Wulin Village at the Village Scale

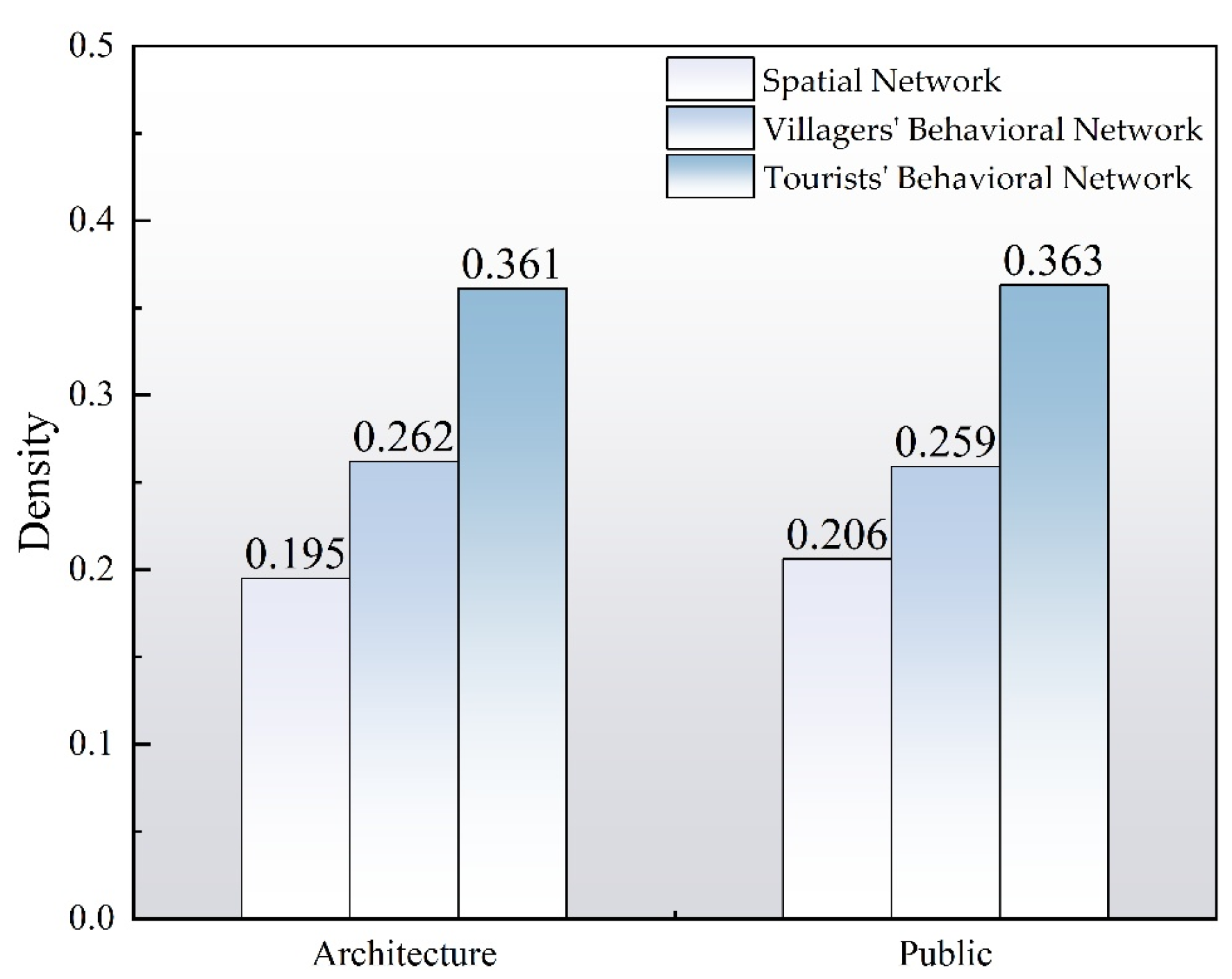

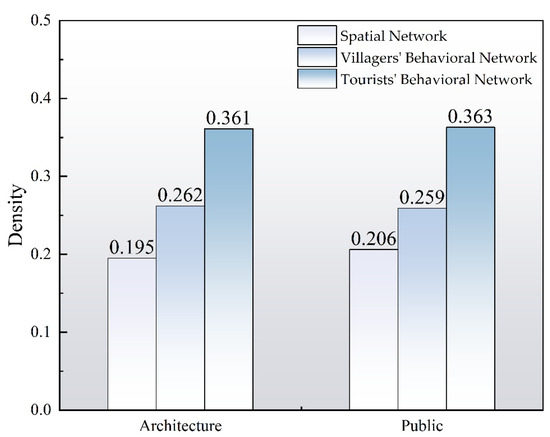

4.2.1. Wulin Village Spatial and Behavioral Network Density Analysis

Figure 4 shows that the tourist behavioral network has the highest density (architecture: 0.361, public space: 0.363), followed by the villagers’ behavioral network (architecture: 0.262, public space: 0.259), while the objective spatial network has the lowest density (architecture: 0.195, public space: 0.206). Specifically, the high density of the tourist behavioral network indicates that tourists’ activity paths are relatively concentrated, primarily in the core areas of the Ancient Village Cultural Experience Zone (e.g., the ancestral hall, visitor center, and other cultural spaces). A high-density tourist behavioral network means that tourists spend more time and interact frequently in these areas, thus improving the spatial utilization efficiency of these locations. The high concentration of tourist behavior paths may suggest that the overall tourist experience is relatively efficient, especially in the core areas, where tourists can quickly access multiple cultural nodes, enhancing the continuity of their visit experience.

Figure 4.

Network Density Values of Spatial and Behavioral Networks in Wulin Village.

However, over-concentration in certain nodes could have negative effects. For example, the concentration of tourists in core areas might lead to overcrowding and long queues, thus lowering the quality of the visitor experience, especially during peak periods. The high density of the tourist behavioral network suggests that the core areas’ spaces are being well utilized. The frequent use of these nodes may encourage the development of related facilities and services (e.g., guided tours, rest areas, core cultural displays), thereby increasing spatial efficiency. However, this also highlights the underutilization of other non-core areas, resulting in a contradiction between “complete structure—concentrated use.” To improve spatial utilization across the entire village, efforts should be made to guide tourists into non-core areas to disperse the tourist flow. For instance, circular routes and multiple entrance nodes can be designed to connect the peripheral areas with the core zones, taking advantage of the natural terrain and ecological resources surrounding the Wudianxi Stream. This would break the current concentration of paths and enhance the overall vitality of the space.

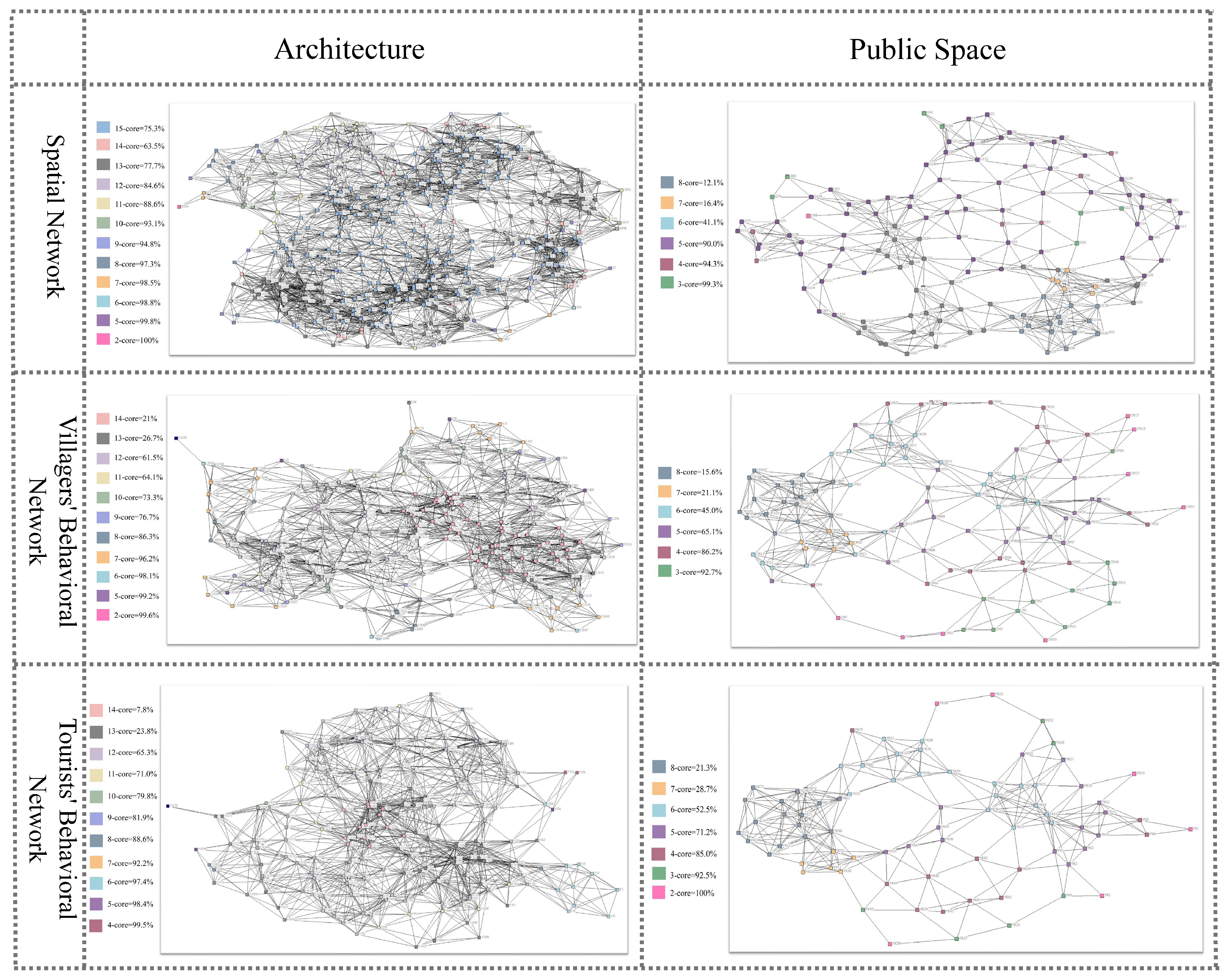

4.2.2. K-Core Analysis of Spatial and Behavioral Networks in Wulin Village

Figure 5 shows that in the architectural space network, the K-core reaches up to 15, with a high proportion of high-core-level nodes (e.g., 10-core accounts for 91.1%, 11-core accounts for 88.6%), indicating a compact core structure and strong spatial connectivity. In contrast, the highest K-core in the public space network is only 8, with proportions below 30%, which shows significantly weaker core characteristics compared to the architectural network. This reflects a more dispersed structure in the public space network, with fragmentation and redundancy present. In the behavioral network, tourists’ behavior paths are concentrated in architectural spaces, with high K-core nodes distributed widely (e.g., more than 70% of nodes are 10-core or above). This indicates that tourist behavior paths are highly dependent on a few core nodes, such as the ancestral hall, visitor center, and other key areas. These nodes serve as critical hubs for tourist activity, central to their behavior paths. However, this concentration means that these nodes play a crucial role in the network, also bringing potential vulnerability. Any obstruction at these core nodes (e.g., congestion, facility damage) would significantly disrupt tourist flow and experience, potentially leading to a breakdown of the entire network.

Figure 5.

K-Core Proportion in the Spatial and Behavioral Networks of Wulin Village.

Although the K-core value of the villagers’ behavior network can also reach 14, the proportion of high-core-level nodes is relatively low, indicating that villagers’ activities are more dispersed, and spatial usage follows a more diffuse pattern. In the public space dimension, the core characteristics of both the tourist and villager behavior networks further decline. Specifically, fewer than half of the villager network nodes exceed five cores, indicating a loose activity path and poor network connectivity. The tourist behavior network slightly outperforms the villager network but still faces marginalization issues, with public space utilization efficiency needing improvement. In conclusion, to reduce reliance on high-K-core nodes and enhance network resilience, measures should be taken to increase the appeal of secondary nodes. For example, more functional and cultural diversion points can be set up along tourist behavior paths, encouraging tourists to visit other nodes and alleviating the burden on core nodes. Additionally, optimizing the infrastructure in core areas (e.g., adding entrances, providing more rest areas, and setting up better guidance systems) can improve node capacity and adaptability, thereby enhancing the stability of the tourist experience.

4.3. Spatial and Behavioral Network Balance Analysis of Wulin Village at the District Scale

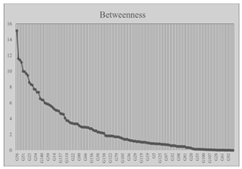

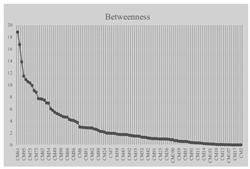

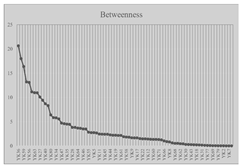

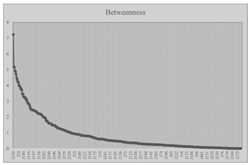

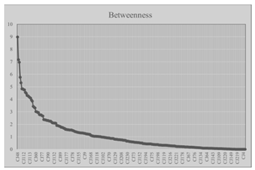

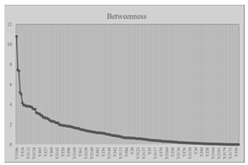

4.3.1. Betweenness Centrality Analysis of Wulin Village’s Spatial and Behavioral Networks

Table 4 shows that in both the architectural and public space networks, the tourist behavioral network has the highest concentration (9.62%, 17.41%), followed by the villagers’ behavioral network (7.91%, 16.03%), and the spatial network has the lowest (6.43%, 12.59%). This indicates that the behavioral networks, especially the tourist network, are more dependent on a few core nodes, making the network structure relatively fragile. In contrast, the spatial network has a more balanced path distribution, offering higher accessibility and resilience. All three networks exhibit a “core–middle–periphery” three-tier structure. The first tier consists of core nodes with high betweenness centrality, which are fewer in number but have strong control. The second tier consists of medium nodes, which occupy the largest proportion and form the main accessibility system. The third tier consists of peripheral nodes with near-zero centrality, which have weak path connectivity and low participation. The three-tier distribution in the spatial network is relatively balanced, while the behavioral networks, particularly the tourist network, show a stronger structural concentration, with a significant reliance on the first-tier nodes and insufficient redundancy.

Table 4.

Betweenness Centrality of Spatial and Behavioral Networks in Wulin Village.

Specifically, the core areas of the behavioral network are primarily concentrated around nodes with a strong religious and cultural atmosphere and multifunctional spatial attributes. These areas, due to their cultural appeal and capacity to support activities, become key nodes for behavior paths, reflecting the purposeful and spatially biased organization of behavior. In contrast, high centrality nodes in the spatial network are more distributed around modern public facilities such as elementary schools, plazas, and commercial streets, demonstrating stronger functional diversity and path balance, and highlighting the physical network’s accessibility and coverage. In summary, there are clear differences in the structural logic and path dependencies between the spatial and behavioral networks. The spatial network’s accessibility structure is more balanced and should serve as the backbone for the integration of behavioral networks. The tourist behavioral network has a high concentration, so it is essential to strengthen its connection to peripheral nodes to enhance network resilience. The villagers’ behavioral network is more distributed, but there is still path concentration in public spaces. This should be guided to expand rationally into more functional spaces, improving the comprehensiveness and sustainability of space utilization.

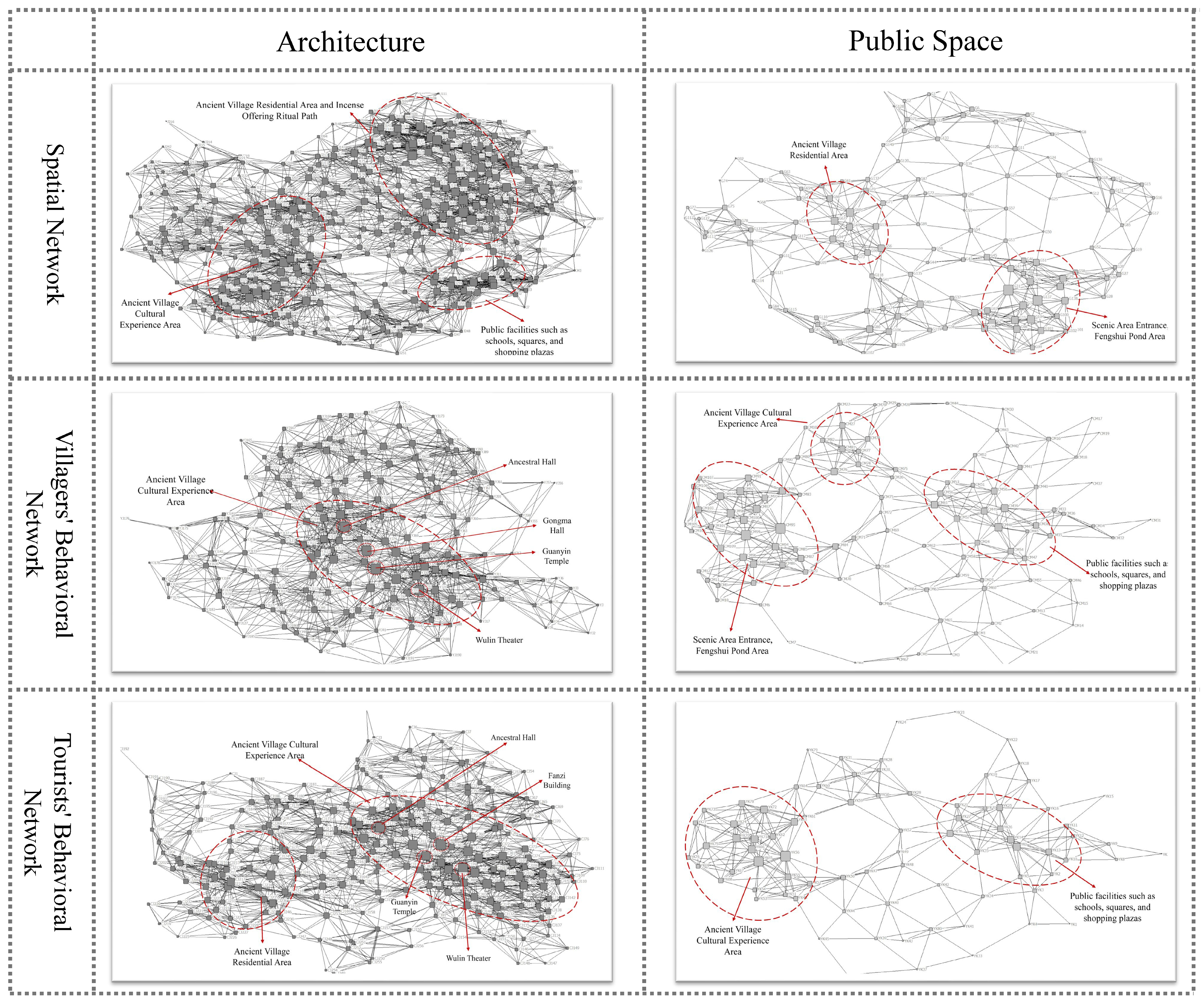

4.3.2. Faction Analysis of Spatial and Behavioral Networks in Wulin Village

Table 5 shows that, overall, the objective spatial network has the most factions (architecture: 31, public spaces: 16), followed by the villager behavior network (architecture: 16, public spaces: 8), and the tourist behavior network has the fewest factions (architecture: 8, public spaces: 4), with a nearly 1:1 decrease across all categories. The reduction in faction numbers suggests that as the network transitions from physical connections to actual behaviors, the relationships between nodes become more concentrated. The tourist behavioral network, with the fewest factions and a more compact structure, indicates that tourist activities are highly concentrated in a few core spaces, with high path overlap and a strong goal-oriented use of space. The villagers’ behavioral network exhibits a middle-ground state, with a moderate number of factions, reflecting that daily activities include both concentrated and somewhat dispersed patterns. Although the architectural space network has more factions, partly due to the larger number of architectural nodes, it still shows a relatively dispersed connection structure and lower spatial aggregation. In contrast, the behavioral networks, particularly the tourist network, show clearer faction structures, with tight internal connections and strong interactions between nodes. This indicates that behavior paths are not simply attached to physical connections but are more influenced by factors such as functional appeal, cultural perception, and behavioral habits.

Table 5.

Faction Distribution of Spatial and Behavioral Networks in Wulin Village.

Overall, the spatial network exhibits a more balanced but dispersed connection structure with loosely organized factions, reflecting the broad geographic coverage of physical space. In contrast, the behavioral network shows stronger aggregation and structural concentration, especially the tourist network, where space use is significantly concentrated in limited areas. Therefore, spatial optimization strategies should be behavior-network-driven, identifying potential behavioral node clusters and activating underutilized nodes in the spatial network through facility additions and path guidance. At the same time, to address the excessive concentration of tourist behavior, a more dynamic and diverse path system should be designed to alleviate pressure on core nodes and improve spatial efficiency.

4.4. Vulnerability Analysis of Spatial and Behavioral Networks in Wulin Village at the Point Scale

4.4.1. Degree Centrality Analysis of Wulin Village’s Spatial and Behavioral Networks

Figure 6 shows that, in the architectural network, the spatial network’s node connections are relatively balanced, with the ancestral hall area, central passageway, and school square forming the main connecting blocks. The overall structure has strong resilience. However, as we move into the behavioral network, structural concentration significantly increases. Villager paths are mainly concentrated around buildings that combine cultural and daily living functions, such as the ancestral hall, Fanzi Building, Guanyin Temple, and Wulin Theater. Path dependency increases, and if these key nodes encounter functional disruptions, the network’s ability to resist disturbances will decline sharply. The tourist behavioral network is even more concentrated, with key nodes such as the ancestral hall, Guanyin Temple, and Gongma Hall becoming the main points for movement and stay. Structural redundancy decreases, and path overlap increases, leading to a “core overload and peripheral vacancy” usage bias. This indicates a high dependence of tourist activities on spatial nodes, resulting in increased overall network vulnerability. There is an urgent need to alleviate this through flow diversion and node activation.

Figure 6.

Degree Centrality of Spatial and Behavioral Networks in Wulin Village.

In the public space network, the spatial network forms a dual-core structure, with the ancestral hall square as the core and the entrance area and Chaodong Building as secondary hubs. Connectivity is good, and the layout is relatively balanced. However, the evolution of the behavioral network has led to more concentrated node use. Villager behavior paths focus on the entrance, religious square, and central activity spaces, leading to increased dependence on core nodes and fewer alternative paths, making the network more vulnerable to disturbances. The tourist behavioral network is highly concentrated around entrance nodes, Chaodong Building, and the ancestral hall. Notably, nodes like Chaodong Building and the Windbreak Pond, which were originally secondary in the spatial network, are excessively used in the tourist path, creating a misalignment between function and structure. This exposes problems such as overload on local space service capacity and insufficient network adaptability. At the same time, some nodes with good connectivity in the spatial network (e.g., the school square, peripheral platforms) are almost absent in the behavioral network, and their spatial potential has not been fully realized. Overall, the high concentration of node usage in the behavioral network reduces redundancy and increases vulnerability in the public space network. Measures such as strengthening node functionality and guiding paths are needed to enhance the spatial network’s capacity balance and behavioral adaptability.

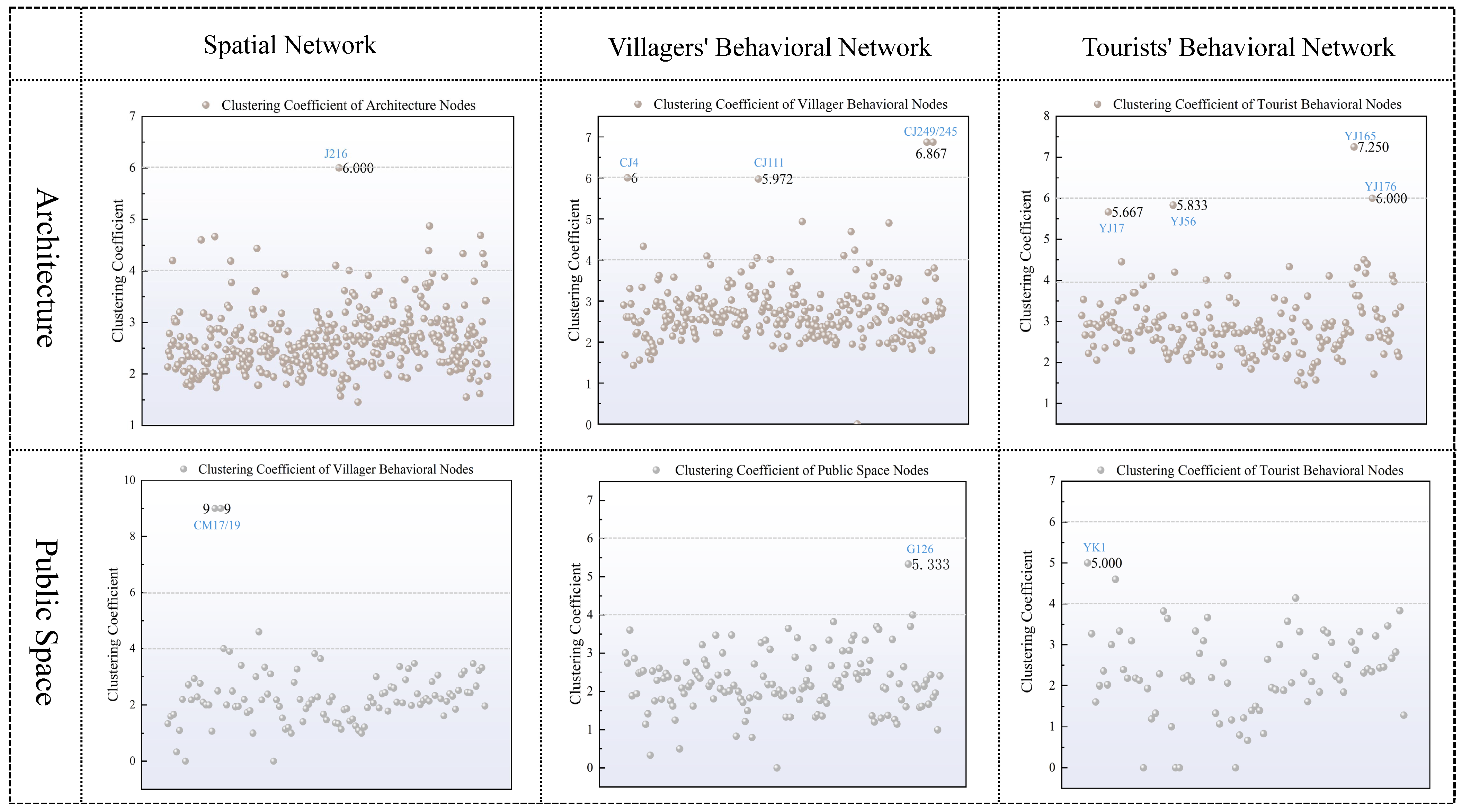

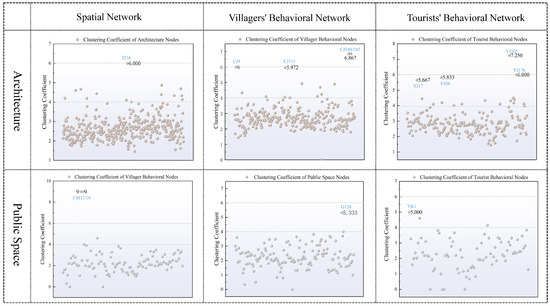

4.4.2. Clustering Coefficient Analysis of Spatial and Behavioral Networks in Wulin Village

Figure 7 shows that the overall clustering coefficient of the spatial network is relatively low, with an open structure and high redundancy. Only a few nodes, such as J216 (Visitor Center) and G126 (near Fanzi Building and Dazhu), exhibit higher clustering, indicating a risk of localized path closure. If obstructed, this could affect the connectivity between the main entrance and the traditional settlement area. However, after the introduction of the behavioral network, the original structural balance is significantly disrupted. In the villagers’ behavioral network, nodes such as CJ249, CJ245, and CJ111, which represent residential buildings, become high-cluster nodes, reflecting the concentration of villagers’ movement paths in the core living area. This indicates high path redundancy in spatial usage. CJ4 (around the visitor center), as an intersection point, has a closed structure that reinforces local path dependency. If the function of these nodes is restricted, it will directly lead to localized network fragmentation.

Figure 7.

Clustering Coefficient of Nodes in the Spatial and Behavioral Networks of Wulin Village.

The tourist behavioral network shows stronger structural concentration and vulnerability. Nodes such as YJ165 (commercial residential building) and YJ176 (visitor center) exhibit significantly higher clustering, indicating that tourist paths are heavily dependent on a few sightseeing entrances and iconic spaces. YK1 (Old School, Fanzi Building area) also has high clustering, and its closed path characteristics make it less flexible, resulting in weak accessibility. If these core nodes become congested or closed, it will be difficult to maintain normal tourist flow. In summary, the spatial network has relative resilience, while the behavioral network, especially the tourist network, exhibits a high concentration of paths around multifunctional, iconic nodes. The clustering structure is closed and lacks flexibility, leading to a significant increase in overall network vulnerability. Spatial optimization should focus on identifying high-cluster nodes, using path diversification, node specialization, and functional substitution to enhance the adaptability and robustness of the behavioral network.

5. Discussion

5.1. Multi-Scale Coupling Analysis of Spatial Structure from the Behavioral Network Perspective

This study compares the spatial and behavioral networks of Wulin Village to reveal how spatial structure responds to the involvement of multiple behavioral agents. The results show that at the village scale, the spatial network is highly connected and redundant, with strong overall completeness. However, in the behavioral network, both tourists and villagers concentrate their paths in core areas, leaving peripheral spaces underutilized, creating a “structural integrity—concentrated usage” contradiction. This indicates that while the spatial network is well-structured, the uneven distribution of behavior limits full space utilization. At the district scale, the spatial network is balanced, linking various functional zones. However, tourist behavior is mainly concentrated around cultural nodes (such as the ancestral hall and visitor center), while villagers prefer daily living and implicit public spaces. This creates a pattern of “dense hot spots—sparse cold zones,” showing an imbalance in spatial vitality between areas. It suggests the need for further optimization of space layout to foster coordinated development across zones. At the point scale, both tourist and villager activities are heavily concentrated on a few core nodes, forming high-degree, high-cluster hubs. This reliance on key nodes increases network vulnerability. If these nodes are disrupted, the entire network’s stability could be compromised. This highlights the need to reduce dependency on specific nodes by dispersing traffic and adding redundant connections to strengthen network resilience.

As a cultural village, Wulin Village’s spatial layout and behavior path choices are influenced not only by geographical factors but also by its cultural background. Compared with spatial studies of other traditional villages, such as those in Huizhou [43], Jiangxi [44], and Southern Jiangxi [45], which typically consider high spatial integration nodes as the core areas for villagers’ daily activities, with highly coupled spatial forms and behavior paths, Wulin Village shows notable differences. While traditional cultural nodes such as the ancestral hall, theater, and Gongma Hall play important roles in the behavior network, the paths taken by tourists and villagers differ significantly. Tourists’ paths concentrate on cultural display spaces with limited activity range and few alternative paths, while villagers prefer spaces for daily interactions, resulting in more dispersed paths. This difference indicates that the activation of spatial structure in Wulin Village varies between different user groups. For example, the concentration of tourists in cultural display spaces reflects the strong cultural identity and historical experience attraction in Wulin Village, whereas villagers focus more on practical living needs, leading to less overlap between the two behavior paths. This difference highlights the importance of cultural background in spatial optimization. Cultural sites are not only central to tourist behavior paths but also play a significant role in the daily activities of villagers. The over-concentration of tourist behavior networks in cultural nodes, while enhancing the visitor experience, also brings the risk of “node overload” and “path monotony,” which prevents the full activation of spatial potential. Especially in tourism-driven villages, the excessive concentration of cultural display spaces leads to underutilization of other areas, reducing overall spatial efficiency [46,47]. This phenomenon is consistent with studies on cultural settlements abroad, such as those in Italy [48,49] and Japan [50]. In these cases, the core areas of the spatial network typically show higher centrality and clustering values, with core nodes having a stronger dependency on the overall network. However, compared to these cases, Wulin Village’s tourist behavior network exhibits a more significant dependency on core nodes and a higher concentration of paths, with a more prominent clustering effect, especially in the core tourist flow areas. This indicates that the spatial imbalance in Wulin Village is more pronounced than in some international cases, with greater pressure on core areas and underdeveloped potential in peripheral zones.

Unlike other traditional settlements, Wulin Village possesses distinct cultural complexity and tourism display characteristics, with clan rituals, overseas Chinese culture, and a blend of Eastern and Western architecture forming the village’s cultural landscape. These cultural factors profoundly influence spatial usage patterns and tourist behavior paths. In particular, spatial renovations and public facility updates are often concentrated in core display areas, further reinforcing the trend of concentrated tourist paths. Meanwhile, villagers continue to use space primarily for living functions, forming a relatively closed network of daily activities. This cultural difference leads to spatial bias and structural displacement, necessitating consideration of cultural heritage in spatial optimization to balance the spatial needs of both tourists and villagers. Specifically, the cultural identity of overseas Chinese has a profound impact on tourist behavior paths. For example, tourists’ preference for the “blended Chinese and Western architectural style” may be closely linked to overseas Chinese culture and its traditional practices, especially at cultural nodes such as the ancestral hall and visitor center, which tend to attract large numbers of tourists. Furthermore, as tourism develops, villagers’ spatial usage patterns have also changed. Areas originally used for daily living by villagers are increasingly occupied by tourism activities, which not only compresses the living space for villagers but may also lead them to concentrate their behavior paths in more private and hidden spaces. This exacerbates the spatial division between core and peripheral areas. Therefore, given these cultural and usage differences, spatial optimization strategies should pay greater attention to balancing cultural preservation and the needs of villagers, avoiding the overdevelopment of single-function spaces to ensure sustainability and diversity. In summary, Wulin Village exhibits a “balanced structure—concentrated behavior—vulnerable nodes” pattern in its multi-scale spatial network. While the spatial structure is relatively stable, the actual distribution of behavior paths alters the logic of spatial usage, leading to low spatial efficiency and concentrated node risks. This tension represents a core issue that tourism-based rural areas must address in spatial governance and public resource allocation. Therefore, future spatial optimization should focus on guiding behavior paths, increasing the usage frequency of non-core areas, and reducing excessive reliance on core nodes, thereby enhancing the resilience and sustainability of the network. Additionally, cultural factors should be incorporated into spatial optimization strategies to promote positive interaction between culture and space, ensuring cultural heritage preservation while enhancing the tourist experience and spatial efficiency.

5.2. Spatial Optimization Strategies for Tourism Villages Based on Social Network Analysis

Based on the analysis of Wulin Village’s spatial network and behavioral network completeness, balance, and vulnerability, spatial optimization strategies are proposed from the multi-scale features of social network analysis, aiming to enhance network connectivity, behavior guidance, and structural resilience, thereby improving the spatial adaptability and usage efficiency of tourism-based rural areas.

- (1)

- Village Scale: Enhancing Overall Connectivity and Reducing Spatial Usage Bias

To address the “concentrated use—structural shift” characteristic in the behavioral network, behavior paths should be guided to cover more peripheral spaces, improve external connectivity, and strengthen multi-path connections between nodes to enhance the overall completeness of the network. First, optimize behavior paths: Circular routes and multiple entrance nodes can be established to link the peripheral and core areas, promoting more balanced spatial use. By guiding both tourists and villagers to visit core and non-core areas, tourist flow can be dispersed, improving overall spatial utilization. Secondly, cultural activation and functional enhancement of non-core spaces: Promoting the functional enhancement and cultural activation of non-core space nodes (such as residential displays, daily scene creation, etc.) can expand the activity trajectories of both tourists and villagers, breaking the current path overlap and network imbalance, and creating a more flexible and behavior-dispersed spatial system. In particular, multifunctional cultural experience zones can be set up to activate peripheral spaces, promoting cultural continuity and development. Finally, space diversion design: Using Wulin Village’s existing alley system, “slow tourist corridors” and “living passageways” can be created to separate the spaces used by tourists and villagers. This spatial diversion not only helps alleviate pressure from concentrated tourist flow but also improves the mobility of villagers’ daily activities [51]. Encouraging the use of vacant buildings or peripheral landscape nodes at village entrances to create “stable—perceptible—redirectable” guide spaces can shift these areas from “ignored” to “engaged,” meeting the needs of tourists while also providing more space for villagers.

- (2)

- District Scale: Optimizing Node Configuration and Balancing Behavior Path Distribution

To address the “dense hot zones—sparse cold zones” pattern in the behavioral network at the district scale, the layout and functional attributes of nodes should be adjusted to activate underperforming spatial areas. It is recommended to set up buffer zones around high-frequency nodes to guide tourist behavior into spreading locally and avoid node overload. Tourist flow can be diverted by setting up guide buffer zones around high-frequency nodes such as the ancestral hall square and visitor center, effectively guiding tourists to different functional areas and alleviating the pressure on core nodes. At the same time, the functional activation of hidden public spaces (such as residential alleys) should be promoted by adding functions such as socializing, signage, and resting areas to increase their participation in the behavioral network [52]. Next, spatial preferences of different user groups should be managed through zoning, and the reorganization of transportation microcirculation and visual lines can coordinate the shared space paths. This will help ease the concentrated tourist flow while maintaining the coherence of traditional village spaces. In the organization of scenic areas, an “axis extension + node reconstruction” approach can be adopted to strengthen accessibility and functional complementarity within districts, promoting the flow interaction between cold and hot zones. Particularly in the transformation of traditional courtyards and alley spaces, small-scale cultural displays, drinking points, and interactive walls can be set up to activate micro-nodes along paths, improving accessibility and behavioral attraction [53].

- (3)

- Point Scale: Enhancing Key Node Resilience and Building a Multi-Center Support Structure

To address the vulnerability of nodes with high degree centrality and clustering coefficients, the structural resilience and service redundancy of these nodes should be strengthened. For key nodes like the ancestral hall, theater, and visitor center, measures such as expanding stay space, setting multiple entrances, and increasing signage can enhance their spatial capacity, allowing them to handle peak tourist flows. At the same time, multiple secondary function centers should be built to share the load of main nodes, forming a “primary-secondary combination, layered support” spatial structure to improve the overall stability of the spatial system. Moreover, for cultural settlements like Wulin Village, where display and daily life intertwine, the multi-scenario adaptability of node functions must be strengthened. For example, flexible usage interfaces (such as open/closeable sheltered spaces, interactive guide systems, etc.) can be set up in core nodes to handle peak loads or sudden restrictions, enhancing the adaptability and stability of these nodes across different times and user groups [54,55]. Behavioral monitoring and node status assessments should be introduced to periodically identify the load status of high-frequency nodes and dynamically optimize spatial management strategies to improve the network’s resilience and ensure long-term stability.

In conclusion, spatial optimization for tourism-based villages should not only focus on the physical organization of space but also consider the distribution features and node attributes of behavioral networks from a social network perspective, employing multi-scale and differentiated strategies. Through systematic spatial network governance, rural spaces can transition from “passive adaptation” to “active guidance,” improving overall spatial efficiency and cultural functionality while promoting sustainable spatial evolution in the context of cultural tourism integration.

5.3. Limitations and Prospects

This study proposes an analytical approach combining multi-scale spatial and behavioral networks. While it has achieved certain results, there are also some limitations. First, the study relies on Wulin Village as a case study, and the limitations of this sample may affect the generalizability of the conclusions. Future research should expand the sample scope to include different types of tourism villages and cultural contexts to validate the universality and applicability of the method. Second, although efforts were made to ensure the completeness of data collection, some nodes and behavior paths were missing, which may affect the comprehensiveness of the results. Therefore, future research could improve data accuracy through more refined data collection methods and advanced data analysis techniques. From a theoretical contribution perspective, this study fills a gap in spatial behavior analysis by combining multi-scale spatial and behavioral networks, particularly in the context of complex tourism village spaces. The method reveals the interaction between tourist and villager behavior patterns and spatial structures at different scales, expanding the application boundaries of spatial network and behavioral network theories. The study also integrates cultural context into behavioral path analysis, promoting the application of cultural factors in spatial behavior research. The proposed spatial optimization strategies provide a theoretical basis and practical guidance for improving space usage efficiency and enhancing the tourist experience.

However, there are certain limitations. First, the sample limitation means that the conclusions of the study may not be universally applicable. Future research could conduct cross-regional comparisons in different cultural and geographical contexts to test the adaptability of the method. Second, the study did not fully consider seasonal factors, particularly the impact of peak and off-peak tourist seasons on behavior and space usage, which may affect the accuracy of the spatial optimization strategies. Future studies should incorporate seasonal variations to further improve the precision of spatial optimization. Moreover, with advances in technology, future research could combine big data analysis, IoT technologies, and real-time monitoring to enhance the real-time capabilities and accuracy of spatial and behavioral network analysis. These technologies would enable more precise tracking of tourist and villager behavior paths, providing more accurate support for spatial optimization. Future research should also explore the influence of cultural factors on spatial behavior patterns in greater depth, especially in culturally rich villages, and consider how to balance spatial optimization with cultural preservation. Overall, this study provides a new theoretical framework and methodology for tourism village spatial optimization, but it still has certain limitations. Future research could deepen the understanding in areas such as cross-regional comparisons, the incorporation of seasonal factors, and the enhancement of technological tools, to further promote the sustainable development of tourism village spatial optimization.

6. Conclusions

At the village scale, the spatial network of Wulin Village shows high connectivity and path redundancy, with strong overall network completeness. However, in the behavioral network, both tourists’ and villagers’ paths are highly concentrated in core areas, with peripheral spaces seeing lower participation, resulting in untapped spatial potential and creating a contradiction of “structural integrity—concentrated usage.” At the district scale, the spatial network node distribution is relatively balanced, connecting multiple functional zones. However, tourist behavior paths are mainly focused on cultural function nodes in the ancient village cultural experience area (such as the ancestral hall, visitor center, and theater), while villagers prefer daily living spaces and implicit public spaces. This results in a “dense hot spots—sparse cold zones” path distribution, reflecting an imbalance in spatial vitality across districts, indicating the need for further optimization of spatial layout to promote coordinated development across functional areas. At the point scale, both tourist and villager activities are highly concentrated at a few core nodes, forming multiple high-degree, high-cluster hubs. Over-reliance on these nodes increases the network’s vulnerability, highlighting the need to disperse traffic and strengthen redundant nodes to enhance network stability.

Based on this, the study proposes targeted spatial optimization strategies: enhancing spatial connectivity at the village scale, optimizing node function distribution at the district scale, and strengthening the resilience of core nodes at the point scale. Specific suggestions include enhancing the functions of peripheral areas, increasing the attractiveness of non-core nodes, and guiding the dispersion of tourist and villager behavior paths to reduce excessive reliance on single nodes. At the same time, the capacity and accessibility of high-frequency core nodes should be enhanced to avoid the risk of network overload. Especially in the context of cultural villages, optimizing based on behavioral networks not only better guides tourist behavior but also effectively conveys the continuity and diversity of culture, promoting a deeper cultural experience for visitors. Through multi-scale analysis of spatial and behavioral networks, we can enhance cultural activation and improve the functionality of non-core areas, resulting in a more balanced spatial layout. This will help improve the spatial vitality of peripheral areas, break the “core overload” situation, and drive the sustainable development of the entire village. This study provides a new technical pathway for tourism space governance in traditional villages, particularly in the optimization and behavioral guidance of cultural villages. Through the analysis of spatial reconstruction and cultural transmission in Wulin Village and other similar villages in a tourism context, this research offers transferable theoretical references and strategies. Through systematic multi-scale network analysis and optimization strategies, this study provides more precise decision-making support for rural space governance, contributing to the sustainable development of rural tourism and promoting the organic integration of cultural tourism and local cultural heritage preservation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.X., Z.L., M.X., H.L. and Y.T.; Data curation, J.X., Z.L., M.X. and Y.T.; Formal analysis, J.X., Z.L. and M.X.; Funding acquisition, M.X.; Investigation, J.X., Z.L., M.X., H.L. and Y.T.; Methodology, J.X., Z.L., M.X. and H.L.; Project administration, J.X., Z.L. and M.X.; Resources, J.X., Z.L., M.X., H.L. and Y.T.; Software, J.X., Z.L. and H.L.; Supervision, J.X., Z.L., M.X. and Y.T.; Validation, J.X., Z.L., H.L. and Y.T.; Visualization, J.X., Z.L. and M.X.; Writing—original draft, J.X. and Z.L.; Writing—review and editing, J.X., Z.L. and M.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is supported by the Ministry of Education Foundation on Humanities and Social Sciences, grant number: 23YJA760042.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not Applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not Applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to the participation in projects that have not yet been completed, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper. Yigao Tan is employed by China Construction Fifth Engineering Bureau, his employer’s company was not involved in this study, and there is no relevance between this research and their company.

References

- Daimou, W.; Zhexiao, W.; Bin, Z. Traditional Village Landscape Integration Based on Social Network Analysis: A Case Study of the Yuan River Basin in South-Western China. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.Y.; Yan, R.; Wang, M. Development and Spatial Reconstruction of Rural Homestays from the Perspective of Actor-Network Theory and Sharing Economy: A Case Study of Guanhucun, Shenzhen. Progress. Geogr. 2018, 5, 1956–1973. [Google Scholar]

- Teo, P.; Li, L.H. Global and local interactions in tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2003, 30, 287–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisvoll, S. Power in the production of spaces transformed by rural tourism. J. Rural. Stud. 2012, 28, 447–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, L.; Kerstetter, D.; Hunt, C. Tourism development and changing rural identity in China. Ann. Tour. Res. 2017, 66, 170–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimura, T. The impact of world heritage site designation on local communities–A case study of Ogimachi, Shirakawa-mura, Japan. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 288–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palang, H.; Helmfrid, S.; Antrop, M.; Alumäe, H. Rural Landscapes: Past processes and future strategies. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2003, 70, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Inbakaran, R.J.; Jackson, M.S. Understanding Community Attitudes Towards Tourism and Host-Guest Interaction in the Urban-Rural Border Region. Tour. Geogr. 2006, 8, 182–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.Z.X.D. Spatial Characteristics of Traditional Villages Based on the Human-Land Relationship: A Case Study of Clan Settlements in the Minnan Basin. Mod. Urban Res. 2020, 12, 29–35. [Google Scholar]

- Karin, I.; Philip, L. Structural and Institutional Determinants of Influence Reputation: A Comparison of Collaborative and Adversarial Policy Networks in Decision Making and Implementation. J. Publ. Adm. Res. Theor. 2016, 26, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Latour, B. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory; Oxford University Press: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Jie, X.; Xiaodong, F.; Zhiwei, T. Understanding user-to-User interaction on government microblogs: An exponential random graph model with the homophily and emotional effect. Inform. Process Manag. 2020, 57, 102229. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.; Yanhui, J. Construction of Cooperative Networks for the Digital Transformation of Rural Governance under Actor-Network Theory: A Field Study of Guoyuan Town, Changsha County. J. Hunan Agric. Univ. (Soc. Sci.) 2024, 2, 59–68. [Google Scholar]

- Lusher, D.; Koskinen, J.; Robins, G. Exponential Random Graph Models for Social Networks: Theory, Methods, and Applications; Cambridge University Press: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Q.; Cheng, T.; Zhang, C. The Process and Mechanism of Digital Empowerment in Deep Integration of Rural Culture and Tourism: A Case Study of Wusi Village, Zhejiang Province. Progress. Geogr. 2024, 10, 1956–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chengcheng, W.; Dawei, C. Tourist versus resident movement patterns in open scenic areas: Case study of Confucius Temple Scenic area, Nanjing, China. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2021, 23, 1163–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michela, A.; Nicola, S. Actor-network theory and stakeholder collaboration: The case of Cultural Districts. Tour. Manag. 2010, 32, 641–654. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Ma, H.; Luo, J.; Huo, X.; Yao, X.; Yang, S. Spatial optimization mode of China’s rural settlements based on quality-of-life theory. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2018, 26, 13854–13866. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.Q.J.C. The Cluster Evolution Mechanism of Red Tourism Villages Based on Actor-Network Theory. Human Geography. Human. Geogr. 2023, 38, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedeke, A.N. Creating sustainable tourism ventures in protected areas: An actor-network theory analysis. Tour. Manag. 2017, 61, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretty, J.; Ward, H. Social Capital and the Environment. World Dev. 2001, 29, 209–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, M. Researching rural conflicts: Hunting, local politics and actor-networks. J. Rural Stud. 1998, 14, 321–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Xiaolin, Z.; Wu, J.; Zhu, B. Spatial Pattern and Driving Mechanism of Rural Settlements in Southern Jiangsu. Sci. Geogr. Sin. 2014, 34, 438–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodin, R.; Crona, B.I. The role of social networks in natural resource governance: What relational patterns make a difference? Glob. Environ. Change 2009, 19, 366–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Xiyue, W.; Yi, Q.; Qing, L. Spatial-Temporal evolution and land use transition of rural settlements in mountainous counties. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2024, 36, 38. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Q. Study on Spatial Agglomeration of Rural Tourism Based on “Point-Axis System” Theory: A Case Study of Jiangshan, Zhejiang. Econ. Geogr. 2013, 33, 174–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiaonan, Q.; Du, X.; Yue, W.; Lina, L. Spatial Evolution Analysis and Spatial Optimization Strategy of Rural Tourism Based on Spatial Syntax Model Case Study of Matao Village in Shandong Province, China. Land 2023, 12, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, Y.; Ye, W.; Li, B. Tourism Adaptability of Traditional Villages Based on the “Production–Living–Ecology” Spatial Framework: A Case Study of Zhangguying Village. Econ. Geogr. 2024, 42, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chengcai, T.; Yuanyuan, Y.; Yaru, L.; Xiaoyue, X. Comprehensive evaluation of the cultural inheritance level of tourism-oriented traditional villages: The example of Beijing. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2023, 48, 101166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnes, D.; Nandatama, A.; Isdyantoko, B.A.; Nugraha, F.A.; Ghivarry, G.; Aghni, P.P.; ChandraWijaya, R.; Widayani, P. Remote sensing and GIS-based site suitability analysis for tourism development in Gili Indah, East Lombok. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2016, 47, 12013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jingbo, Y.; Dongyan, W.; Hong, L. Spatial optimization of rural settlements in ecologically fragile regions: Insights from a social-ecological system. Habitat Int. 2023, 138, 102854. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, X.; Li, H.; Zhang, X.; Chen, X.; Yuan, Y. Multi-dimensionality and the totality of rural spatial restructuring from the perspective of the rural space system: A case study of traditional villages in the ancient Huizhou region, China. Habitat Int. 2019, 94, 102062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guolei, C.; Jing, L.; Juxin, Z.; Ye, T.; Ying, D. Spatial Structure Identification and Influence Mechanism of Ethnic Villages in China. Sci. Geogr. Sin. 2018, 38, 1422–1429. [Google Scholar]

- Xi, Y.; Fuan, P. Clustered and dispersed: Exploring the morphological evolution of traditional villages based on cellular automaton. Herit. Sci. 2022, 10, 133. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, Q.H.Y.D. Living Evaluation and Adaptive Conservation of Traditional Villages: A Case Study of Three Typical Villages in the Loess Hilly and Gully Region of Longzhong. South. Archit. 2024, 4, 54–63. [Google Scholar]

- Placido, G.M. The reservation by relocation of Huizhou vernacular architecture: Shifting notions on the authenticity of rural heritage in China. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2022, 28, 200–215. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, H.; Xie, M.; Huang, Z.; Bao, Y. Study on spatial distribution and connectivity of Tusi sites based on quantitative analysis. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2023, 14, 101833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Gong, M.; Zhang, Z. Optimization Strategies for Rural Public Spaces Based on the Matching of Spatial and Behavioral Networks. Archit. J. 2022, S1, 86–90. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Xiao, L.; Hu, Y. Research on Urban Infrastructure Health Evaluation Based on Social Network Analysis: A Case Study of Power In-frastructure in Wanzhou District, Chongqing. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 2015, 45, 68–80. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Z.; Huang, Z.; Xiang, H.; Lu, S.; Chen, Y.; Yang, J. Exploring Connectivity Dynamics in Historical Districts of Mountain City: A Case Study of Construction and Road Networks in Guiyang, Southwest China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, M.E.J. The structure and function of complex networks. Siam Rev. 2003, 45, 167–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.W. Network Approach: A Practical Guide to UCINET Software, 3rd ed.; Gezhi Publishing House: Shanghai, China, 2009; pp. 48–138. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Chu, J.; Ye, J. Spatial Evolution Characteristics and Driving Mechanism of Traditional Villages in Ancient Huizhou. Econ. Geogr. 2018, 38, 152–162. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Dong, H. Spatial and temporal evolution patterns and driving mechanisms of rural settlements: A case study of Xunwu County, Jiangxi Province, China. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 24342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wu, S.; Li, X. Identification Classification Differentiated Guidance of Multifunctional Development of Traditional Villages: A Case Study of 44 Traditional Villages in Yixian County Anhui, Province. J. Nat. Resour. 2024, 39, 1887–1905. [Google Scholar]

- Yizhen, W.; Anxin, X.; Chao, W.; Yuting, S. Spatial and temporal evolution and influencing factors of tourism eco-efficiency in Fujian province under the target of carbon peak. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 23074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.; Wu, M.; Shi, J.; Yang, H.; Wang, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, X. The Evolution of the Spatial-Temporal Pattern of Tourism Development and Its Influencing Factors: Evidence from China (2010–2022). Sustainability 2024, 16, 10758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, J.K.S.; Iversen, N.M.; Hem, L.E. Hotspot crowding and over-tourism: Antecedents of destination attractiveness. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 76, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanini, S. Tourism pressures and depopulation in Cannaregio. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 7, 164–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiwasaki, L. Community-Based Tourism: A Pathway to Sustainability for Japan’s Protected Areas. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2007, 19, 675–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.Z.Q.G. Construction of a Livelihood Evaluation Model for Traditional Villages in Guanzhong. Dev. Small Towns 2022, 40, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.Z.X.L. Micro-Renewal and Community Revival of Traditional Villages: Practice of Rural Revitalization in Shitang, Northern Guangdong. Urban Dev. Stud. 2018, 25, 41–45. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, R.; Jiang, P.; Kong, X. Reconstructing Rural Settlements Based on Investigation of Consolidation Potential: Mechanisms and Paths. Land 2024, 13, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gocer, O.; Boyacioglu, D.; Karahan, E.E.; Shrestha, P. Cultural tourism and rural community resilience: A framework and its application. J. Rural Stud. 2024, 107, 103238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, N.; Chen, J.; Ban, L.; Li, P.; Wang, H. Pre-Planning and Post-Evaluation Approaches to Sustainable Vernacular Architectural Practice: A Research-by-Design Study to Building Renovation in Shangri-La’s Shanpian House, China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).